Pattern for the side plate of a six- or ten-plate stove, Batsto Furnace, Burlington County, New Jersey, 1780–1790. Mahogany with oak (battens). 26" x 33". (Courtesy, Burlington County Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Firescreen attributed to Thomas Affleck with carving attributed to Bernard and Jugiez, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1770–1775. Mahogany. H. 60 3/4". (Courtesy, Chipstone Foundation.)

Andirons, possibly Daniel King, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1780–1790. Brass; wrought iron. H. 19 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Details of a foot on the firescreen illustrated in fig. 2 and one of the andirons illustrated in fig. 3.

Chimney back, Marlboro Furnace, Frederick County, Virginia, ca. 1770. Cast iron. 34 1/2" x 31". (Courtesy, United States Army Engineer Museum, Fort Belvoir, Virginia; photo, Robert Hinds.)

Detail of A Survey of the Northern Neck of Virginia (London, 1745). (Courtesy Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

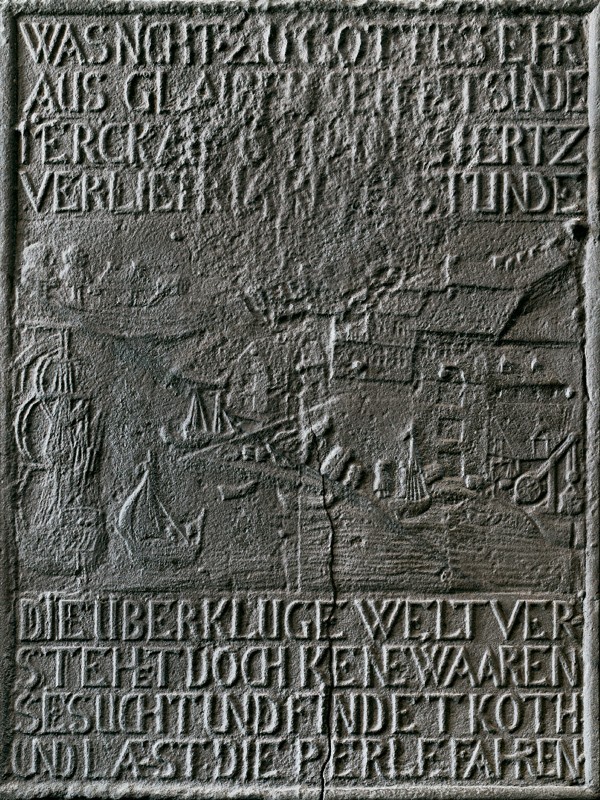

Side plate from a jamb stove, possibly Colebrookdale Furnace, Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1735–1755. Cast iron. 29" x 25". (Courtesy, Mercer Museum of the Bucks County Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The stove represented by this side plate may have had an end plate like the example illustrated in fig. 8.

End plate from a jamb stove, possibly Colebrookdale Furnace, Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1735–1755. Cast iron. 22" x 19". (Courtesy, Mercer Museum of the Bucks County Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This shield design was the seal of Philadelphia after 1701.

Francis Vivares after Thomas Smith of Derby, A View of the Lower Works at Coalbrookdale Furnace, 1758. Etching. 15" x 20 3/4". (Courtesy, © Trustees of the British Museum.)

Philip Loutherbourg, Coalbrookdale by Night, Shropshire, England, 1801. Oil on canvas. 26 3/4" x 42". (Courtesy, Science Museum/Science Society and Picture Library.)

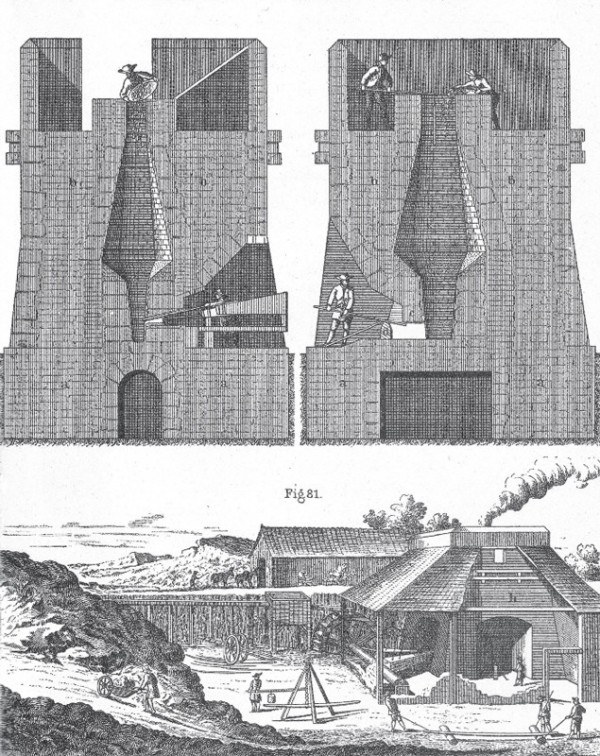

“DE LA CONSTRUCTION DES HAUTS-FOURNEAUX .” (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blast_furnace.)

Wilson Lowry after George Robertson, Inside of a Smelting House, Coalbrookdale Furnace, Shropshire, England, 1788. Engraving. 22" x 18". (Reproduced by permission of the Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust.)

Back of the pattern illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a batten on the pattern illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Pattern for the end plate of a stove, carving attributed to the shop of John Pollard, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1775–1785. Mahogany. 26" x 15". (Courtesy, Mercer Museum of the Bucks County Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Back of the pattern illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the carving on the pattern illustrated in fig. 15, showing the almost perfectly flat ground. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Pier table, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1765. Mahogany with white oak; marble. H. 32 1/2", W. 62 3/4", D. 31 5/8". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The pieces of figured marble veneer forming the top are bonded to a gray stone core with a roughly worked rear edge. The solid molded edges are attached to the core in a manner similar to cross-banded moldings on wooden tops. The top has a complex history of breakage and repair. Most of the veneer pieces at the ends and all of the side moldings are replaced; iron and steel splints have been added to the undersurface; and losses on the top have been filled.

Detail of the lion’s head on the pier table illustrated in fig. 18. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

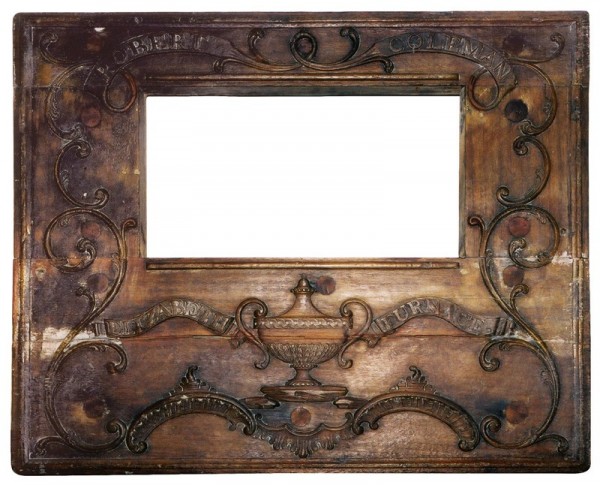

Chimney back, probably Durham Furnace, Bucks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1728. Cast iron. 27" x 18 1/2". (Courtesy, Stenton, National Society of the Colonial Dames of America in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania; photo, Philadelphia Museum of Art.) The initials “I” and “L” were pressed into the casting sand after the pattern was removed. An identical chimney back with the same date, but without initials, has a history of use in Graeme Park.

Chimney back, probably Durham Furnace, Bucks County, Pennsylvania, dated 1746 and 1756. Cast iron. 36" x 36". (Private collection.) A related chimney back with crossed swords has panels with the same dates.

Side plate from a jamb stove, probably Durham Furnace, Bucks County, Pennsylvania, dated 1756. Cast iron. 26" x 28". (Courtesy, Mercer Museum of the Bucks County Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The front plate of the stove represented by this side plate is also dated 1756.

Chimney back, Oxford Furnace, Warren County, New Jersey, 1746. Cast iron. 34 1/4" x 34". (Private collection; photo, Vince Cassaro.)

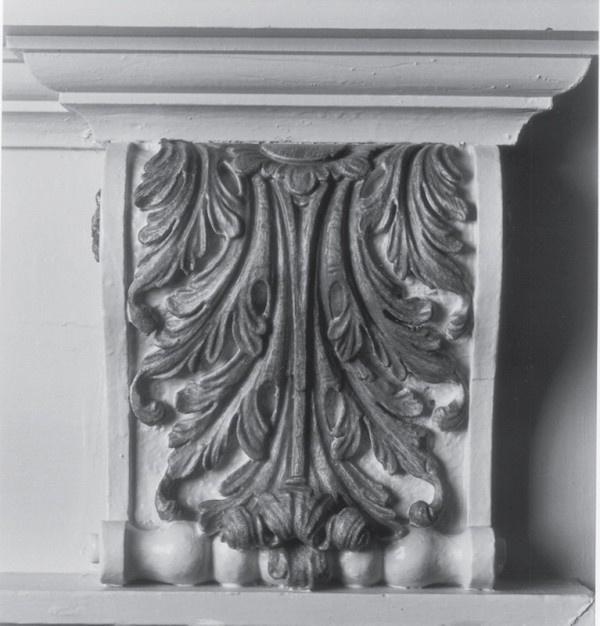

Frieze appliqué in the Assembly Room of the Pennsylvania State House. (Historic American Building Survey, Library of Congress.)

Frieze appliqué attributed to Samuel Harding in the stair tower of the Pennsylvania State House, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1753–1756. (Courtesy, Independence Hall National Historic Site; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Desk-and-bookcase with carving attributed to the shop of Samuel Harding, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1750–1755. Walnut with tulip poplar, yellow pine, and white cedar. H. 112", W. 40 3/4", D. 23 3/4". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the tympanum appliqué on the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 26. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The appliqués on either side of the shell are so undercut that they make little contact with the tympanum and appear to float over it.

Chimney back, Oxford Furnace, Warren County, New Jersey, 1747. Cast iron. 32 1/4" x 29 1/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Exterior truss on the steeple of Christ Church, Philadelphia, 1753. (Historic American Building Survey, Library of Congress.)

Franklin stove attributed to Warwick or Mount Pleasant Furnace, Chester or Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1742–1748. Cast iron. H. 31 1/2", W. 27 1/2", D. 35 3/4". (Courtesy, Mercer Museum of the Bucks County Historical Society; photo, Philadelphia Museum of Art.)

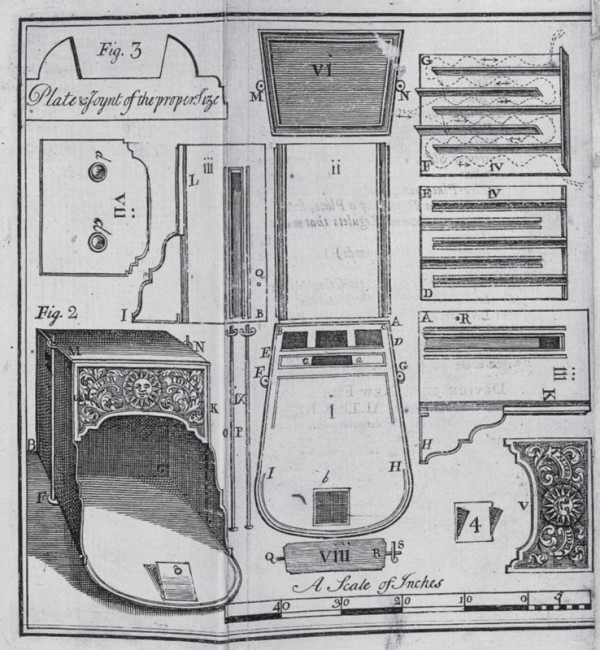

James Turner (act. 1744–1759) after Lewis Evans, design for Franklin’s Stove, illustrated in An Account of the New Invented Pennsylvanian Fire-places. (Courtesy, Library Company of Philadelphia.)

Detail of the front plate of the stove illustrated in fig. 30.

Details of the frieze appliqué illustrated in fig. 24.

Tea table, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1745–1755. Mahogany. H. 27 1/2", W. 34 5/8", D. 21 1/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Detail of the carving on a side rail of the tea table illustrated in fig. 34.

Side plate of a jamb stove, New Jersey or Pennsylvania, 1760. Cast iron. H. 22 1/2", W. 23 1/2". (Courtesy, Mercer Museum of the Bucks County Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

End plate of a jamb stove, New Jersey or Pennsylvania, 1760. Cast iron. H. 221/4", W. 18 1/4". (Henry C. Mercer, The Bible in Iron: Pictured Stoves and Stoveplates of the Pennsylvania Germans [1914; revised, corrected, and enlarged by Horace C. Mann, Doylestown, Pa.: Bucks County Historical Society, 1914], no. 88-c.)

Side chair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1765. Mahogany. H. 41 1/8", W. 23 3/4", D. 21 3/4". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the side plate illustrated in fig. 36. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the crest rail of the side chair illustrated in fig. 38. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

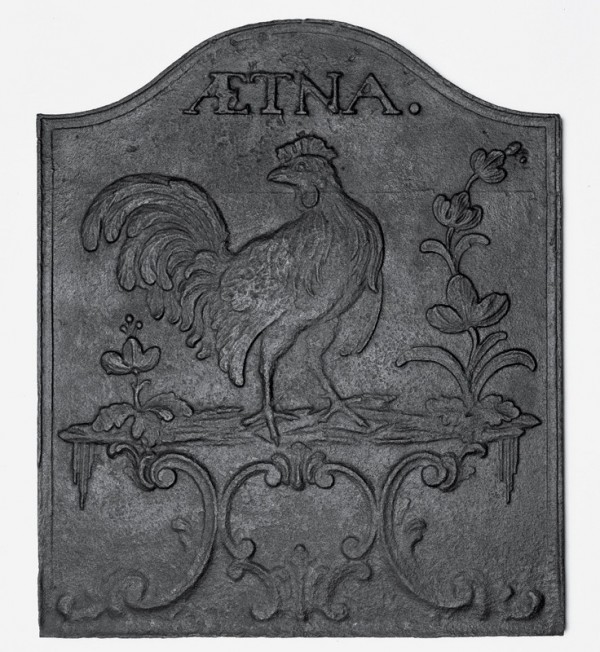

Chimney back, Aetna Furnace, Burlington County, New Jersey, 1767–1775. Cast iron. H. 26 1/4", W. 22 1/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Chimney back, Aetna Furnace, Burlington County, New Jersey, 1767–1775. Cast iron. H. 31", W. 29 1/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

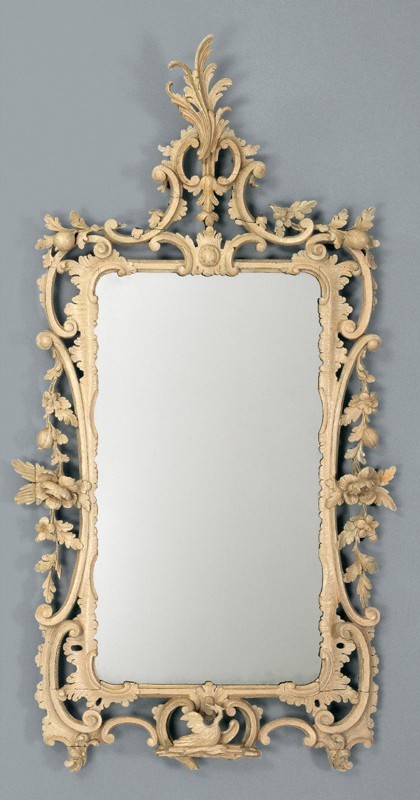

Pier glass attributed to the shop of James Reynolds, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1766–1775. White pine. 48" x 26". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Pattern for a six- or ten-plate stove attributed to the shop of James Reynolds, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1775–1790. Mahogany. Dimensions not recorded. (Private collection.)

Detail of the carving on the pattern illustrated in fig. 44.

Detail of the carving in the upper left corner of a parcel gilt pier glass made by James Reynolds for John and Elizabeth (Lloyd) Cadwalader in 1771. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Chimney back, Marlboro Furnace, Frederick County, Virginia, 1770–1775. Cast iron. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.) The pattern that produced this chimney back was also used to cast stove plates like the example illustrated in fig. 48.

Side plate from a six-plate stove, Marlboro Furnace, Frederick County, Virginia, 1770–1775. Cast iron. 24" x 26". (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.) The pattern that produced this side plate was also used to cast chimney backs like the example illustrated in fig. 47.

Truss attributed to Bernard and Jugiez, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1769. (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art; photo, Luke Beckerdite.) This truss is on a chimneypiece from the Samuel Powel House installed in the American Wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Side plate from a six-plate stove, Pottsgrove Furnace, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1770. Cast iron. 19 1/4" x 23 1/4". (Courtesy, Mercer Museum of the Bucks County Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Thomas Affleck, chest-on-chest , Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1770. Mahogany with tulip poplar and white cedar. H. 101", W. 46 3/8", D. 24". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; acquired through the generosity of Mr. and Mrs. Lewis B. Rumford II.)

Detail of the ornament of the chest-on-chest illustrated in fig. 51.

Side chair with carving attributed to Martin Jugiez, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1765. Mahogany. H. 39 1/2", W. 25 1/2", D. 23 1/2". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Design for a side chair shown on pl. 12 of the first and second editions of Thomas Chippendale’s The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (1754, 1755). (Courtesy, Winterthur Library.) This design appeared on pl. 14 in the third edition (1762).

Side plate from a six-plate stove, Batsto Furnace, Burlington County, New Jersey, 1766–1775. Cast iron. 19 3/4" x 22". (Henry C. Mercer, The Bible in Iron: Pictured Stoves and Stoveplates of the Pennsylvania Germans [Doylestown, Pa.: Bucks County Historical Society, 1914], no. 173.)

High chest of drawers with carving attributed to Bernard and Jugiez, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1770–1775. Mahogany with yellow pine, tulip poplar, and white cedar. H. 96 3/4", W. 45 1/2", D. 24 1/2". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art; photo, Graydon Wood.)

Detail of the appliqué on the center drawer of the lower case of the high chest illustrated in fig. 56.

Detail of a design for a pier glass illustrated on pl. 21 in Thomas Johnson’s One Hundred Fifty New Designs (collected editions, 1758 [untitled] and 1761 [titled]). (Courtesy, Winterthur Library; Printed Book and Periodical Collection.) Johnson sold the designs incrementally in groups between 1756 and 1757. (Jacob Simon, “Thomas Johnson’s ‘The Life of the Author,’” Furniture History 39 [2003]: 10.)

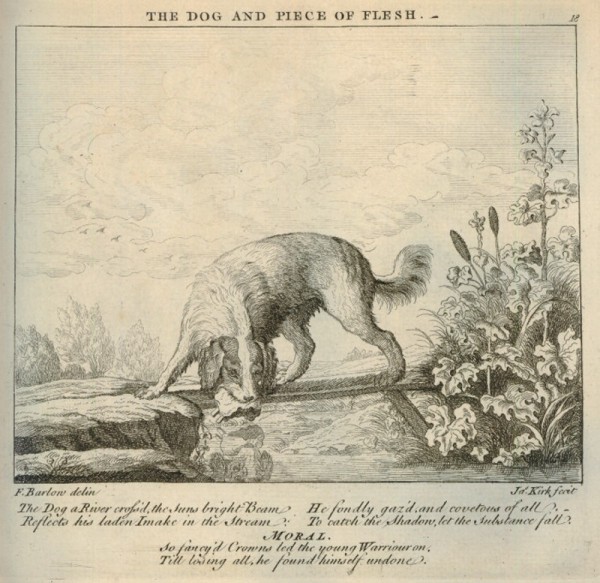

James Kirk (etcher) after Francis Barlow, The Dog and Piece of Flesh, published by Robert Sayer, London, ca. 1760. (Courtesy, © Trustees of the British Museum.)

Ten-plate stove, Elizabeth Furnace, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1769. Cast iron. H. 63 1/4", W. 44 1/4", D. 15". (Courtesy, Hershey Museum.)

Detail of the front plate of the stove illustrated in fig. 60.

Detail of the center tablet on a chimneypiece from the Samuel Powel House, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1770. (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art, gift of Mr. and Mrs. George D. Windner, 1926.)

Side plate from a six-plate stove, Elizabeth Furnace, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1769. Cast iron. 23" x 25". (Courtesy, Mercer Museum of the Bucks County Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side plate from a six-plate stove, Elizabeth Furnace, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1769. Cast iron. Original dimensions, 18 1/2" x 23". (Courtesy, Historical Society of Berks County Museum & Library; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side plate from a six- or ten-plate stove, Reading Furnace, Chester County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1772. Cast iron. 23" x 30". (Courtesy, State Museum of Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.)

Side view of the stove illustrated in fig. 60.

Six-plate stove, Hopewell Furnace, Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1772. Cast iron. H. 35", W. 41", D. 18". (Courtesy, Hopewell National Historic Site; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a side plate of the stove illustrated in fig. 67. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the back plate of the stove illustrated in fig. 67. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Details showing a frieze appliqué on a chimneypiece from the Thomas Ringgold House, Chestertown, Maryland, and a design for a frieze illustrated on pl. 2 in Thomas Johnson, A New Book of Ornaments (1762). (Courtesy, Baltimore Museum of Art; photos, Gavin Ashworth [appliqué] and Victoria & Albert Museum [design].)

Pier table attributed to the shop of Benjamin Randolph with carving attributed to John Pollard, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1769. Mahogany with yellow pine. H. 32 3/8", W. 48", D. 23 1/4". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the side plate illustrated in fig. 68. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the carving on the front rail of the pier table illustrated in fig. 71. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Base of a high chest of drawers with carving attributed to the shop of John Pollard, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1775. Mahogany with yellow pine and white cedar. H. 38", W. 45 5/8", D. 22 13/16". (Courtesy, Diplomatic Reception Rooms, U.S. Department of State.)

Detail of the appliqué on the bottom center drawer of the high chest base illustrated in fig. 74.

Side plate from a six- or ten-plate stove, Durham Furnace, Bucks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1780. Cast iron. 25" x 31 3/4". (Courtesy, Mercer Museum of the Bucks County Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the right frieze appliqué on a chimneypiece from a Philadelphia town house installed in the Winterthur Museum, ca. 1770. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) The frieze appliqués are attributed to John Pollard.

Title page of Animals of Various Species Accurately Drawn by Francis Barlow, part three of Various Birds and Beasts Drawn from Life (London, ca. 1660–1670). (Courtesy, © Tate Museum. CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0)

Pattern fragment, probably Durham Furnace, Bucks County, Pennsylvania, 1775–1780. (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Side plate from a six-plate stove, possibly Durham Furnace, Bucks County, Pennsylvania, or Marlboro Furnace, Frederick County, Virginia, 1775–1780. Cast iron. 22" x 27 1/4". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, gift of Wallace and Liza Gusler.)

End plate from a stove, possibly Durham Furnace, Bucks County, Pennsylvania, or Marlboro Furnace, Frederick County, Virginia, 1775–1780. Cast iron. 21 3/4" x 14 3/8". (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

End plate from a stove, possibly Durham Furnace, Bucks County, Pennsylvania, or Marlboro Furnace, Frederick County, Virginia, 1775–1780. Cast iron. 21 3/4" x 14 1/8". (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

End plate from a stove, possibly Durham Furnace, Bucks County, Pennsylvania, or Marlboro Furnace, Frederick County, Virginia, 1775–1780. Cast iron. 23 3/4" x 14". (Courtesy, Mercer Museum of the Bucks County Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

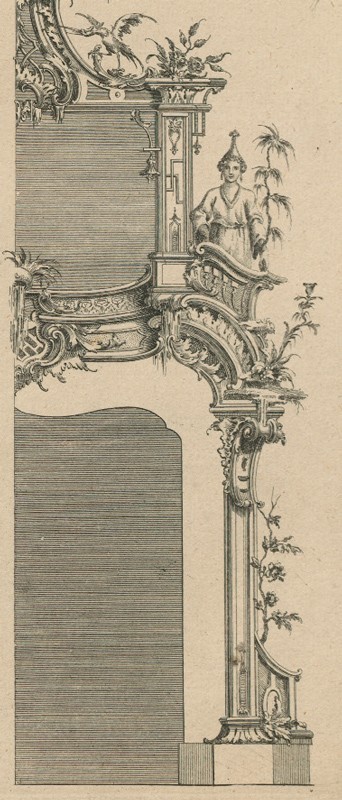

Design for a chimneypiece illustrated on pl. 7 in Matthias Lock and Henry Copland, A New Book of Ornaments (1752). (Courtesy, Winterthur Library; Printed Book and Periodical Collection.)

Design for a chimneypiece illustrated on pl. 4 in Matthias Lock and Henry Copland, A New Book of Ornaments (1752). (Courtesy, Winterthur Library; Printed Book and Periodical Collection.)

Side plate from a six-plate stove, Batsto Furnace, Burlington County, New Jersey, ca. 1772. Cast iron. 23" x 25 1/2". (Courtesy, Mercer Museum of the Bucks County Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Francis Barlow, “The Fowler and the Ringdove,” London, ca. 1687.

Side chair with carving attributed to John Pollard, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1770. Mahogany with yellow pine. H. 38 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the carving on the crest and left stile of the side chair illustrated in fig. 88. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chimney back, Batsto Furnace, Burlington County, New Jersey, 1770–1775. Cast iron. 26 1/4" x 22 1/4". (Courtesy, New Jersey State Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Looking glass with carving attributed to the shop of John Pollard, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1770–1780. Mahogany with white pine. Dimensions not recorded. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the left garland on the chimney back illustrated in fig. 90 and the left garland on the looking glass illustrated in fig. 91. (Photos, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side plate from a ten-plate stove, Sally Ann Furnace, Bucks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1795. Cast iron. 26" x 35". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, purchase, Dobson Foundation, Inc., gift.)

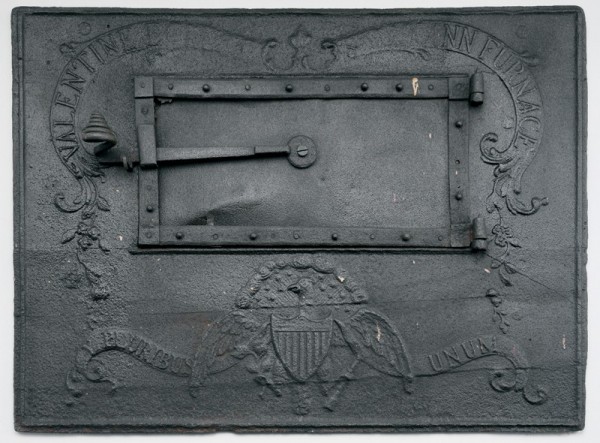

Abraham Buzaglo, stove, London, 1770. Cast iron. H. 88 1/2", W. 35 1/8", D. 21 11/16". (The Commonwealth of Virginia on loan to the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

A Buzaglo, Patent Warming Machine Maker to Their Majesties, Opposite Somerset House Strand, London, ca. 1770. Black and white line engraving. (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; gift of Reverend Richard Webster Meyers, 1992-145.)

Tall case clock, Philadelphia, 1775–1785. Mahogany with tulip poplar. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Philip Bradley Antiques.)

Details of the carving on a quarter-column of the tall case clock illustrated in fig. 96.

Side plate from a six- or ten-plate stove, Mount Aetna Furnace, Washington County, Maryland, 1775–1785. Cast iron. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Six-plate stove, Batsto Furnace, Burlington County, New Jersey, 1780–1790. Cast iron. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, State Park Service, Batsto Village; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a side plate of the stove illustrated in fig. 99. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the carving on the pattern illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the carving on the pattern illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the carving on the pattern illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

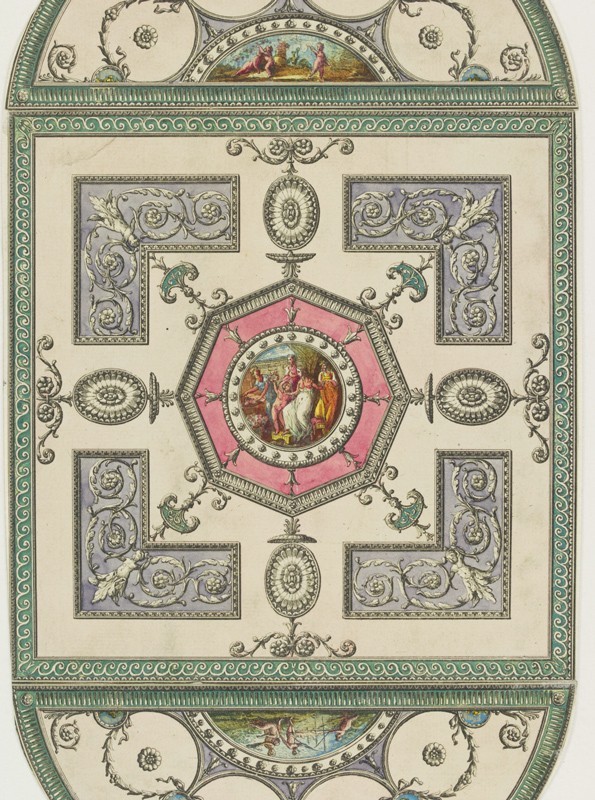

Ceiling design by Robert Adam, 1769. (Courtesy, Victoria & Albert Museum.)

Side plate from a six-plate stove, probably Berkshire Furnace, Berkshire County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1782. Cast iron. 16 1/2" x 24". (Courtesy, Mercer Museum of the Bucks County Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The stove represented by this side plate may have had an end plate like the example illustrated in fig. 106.

End plate from a stove, probably Berkshire Furnace, Berkshire County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1782. Cast iron. 22 1/2" x 15". (Courtesy, Mercer Museum of the Bucks County Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The stove represented by this end plate may have had side plates like the example illustrated in fig. 105.

Side plate from a six- or ten-plate stove, Berkshire Furnace, Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1780–1790. Cast iron. 22 1/2" x 32 1/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) The stove represented by this side plate had an end plate like the example illustrated in fig. 108.

End plate from a six-plate stove, Berkshire Furnace, Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1780–1790. Cast iron. 25" x 15 1/2". (Courtesy, Mercer Museum of the Bucks County Historical Society, photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The stove represented by this end plate had side plates like the example illustrated in fig. 107.

Tall case clock, Philadelphia, 1770–1780. Sabieu with tulip poplar. H. 104". (Courtesy, Philip Bradley Antiques.)

Detail of the hood of the tall case clock illustrated in fig. 109.

Research over the last thirty years has shown that the tools and techniques used by individual carvers are distinctive enough to support strong attributions, particularly when based on documented work and considered within specific historical contexts. Scholars who worked as carvers in the gun-stocking, furniture-making, and restoration trades were largely responsible for establishing this methodological framework, which has led to the identification of work by carvers in nearly every major coastal city as well as those who plied their trade in small towns and rural areas. Today, the names of many of those artisans—Henry Hardcastle, John Lord, John Pollard, and John Welch, to name but a few—are as familiar as those of iconic cabinetmakers cited in publications dating from the beginning of the twentieth century.

Most colonial carvers worked in “all the branches” of their trade. In the February 22, 1773, issue of the Pennsylvania Gazette, John Pollard and Richard Butts advertised carving in the “House, Cabinet, Coach, and Ship way.” New York cabinetmaker John Brinner was more specific. In May 1762 he boasted that his workforce included six “well skill’d” craftsmen “brought over from London” and was capable of carving “all sorts Architectural, Gothic, and Chinese Chimneypieces, Glass and Picture Frames, Slab Tables, Gerondoles, Chandaliers, and all kinds of Moldings and Frontispieces.” Some carvers were able to work in other media. The Philadelphia firm of Bernard and Jugiez advertised “all sort[s] of Carving in Wood or Stone,” whereas James Wilson, a London-trained carver who worked in Williamsburg, Virginia, made “all kinds of Ornaments in Stuco, human Figures and Flowers,” and cut “Seals in Gold and Silver.” Some carvers also taught drawing, which was an essential skill in their trade. According to Robert Campbell’s London Tradesman (1747), “the Carver must have a natural Genius for the Art.... As soon as...this Inclination appears in a Youth, he ought to be set to Drawing, and Kept at it as Long as his Apprenticeship lasts.” For many carvers, the drawing and composition of their designs were almost as distinctive as the techniques used to render them.[1]

Recent studies of colonial American carving have focused on furniture, which accounts for a majority of the surviving work, and architectural ornaments, which are occasionally documented by bills or references in daybooks, account books, ledgers, and correspondence. Very little ship carving survives, although several detailed references to figureheads and other decorative components are known. Patterns for casting stucco, brass, and iron are almost as scarce, but their production was an important branch of the carving trade, particularly in the Middle Atlantic region, which had a flourishing iron industry (fig. 1).

Documentary references to pattern carving are rare. On November 1, 1772, John Dickinson paid Philadelphia carver Hercules Courtenay £105.7.6 for carving fifty architectural trusses, twenty-three stair brackets, “2 long Brackets for [the] West Room,” 55' 2" of molding, and “3 Small Flowers...1 Sun Flower” and a small spandrel “for [the] Stucco man.” Brass founders like Daniel King also commissioned patterns from local carvers. In January 1771 he billed Philadelphia merchant John Cadwalader 15s. for “a carved foot for andirons.” King probably used that wooden positive to create a mold for casting the legs of one or more of the six pairs of andirons he had made for Cadwalader the previous September, one of which had Corinthian capitals and cost £25 (figs. 2-4).[2]

The most widely known reference to a carved casting pattern is from the receipt book of Philadelphia merchant John Pemberton. On December 20, 1770, he paid Nicholas Bernard and Martin Jugiez £8 for “carving the Arms of Earl of Fairfax for a Pattern for the back of Chimney sent Isaac Zane jr.” (fig. 5). Jugiez, who appears to have done most of the carving during his partnership with Bernard, based his design on an armorial in A Survey of the Northern Neck of Virginia, a map commissioned by Thomas Lord Fairfax (1692–1782) in 1745 (fig. 6).[3]

Although no contemporaneous castings are as thoroughly documented as the Fairfax chimney back, many can be linked to specific Philadelphia craftsmen or their shop traditions. Local carvers probably began producing patterns for furnaces during the late 1720s, but only a few dated castings from that period survive. Those seminal objects do, however, represent a baseline for understanding the evolution of the iron industry in the Middle Atlantic region and the role Philadelphia carvers played in the production of later chimney backs and stove plates. This article will survey their work and explore the techniques used by foundry men to produce castings. The focus will be pattern carving for chimney backs and stove plates cast between 1760 and 1790, the period when the rococo reached its peak in Philadelphia and was gradually supplanted by the neoclassical style.

Early Furnaces and Forges

In 1717 Philadelphia mayor Jonathan Dickinson wrote, “This last Summer one Tho Rutter a Smith who Lives not farr from Jerman Town hath removed farther up in the Country and of his own Strength hath Sett upon making Iron....All the Smiths here say that the best of Sweeds Iron Doth not Exceed it.” Rutter’s works was the first of its kind in Pennsylvania, but it was a small forge dedicated to hammering iron into small blooms. It was not until 1720 that he built the colony’s first blast furnace, which he named Colebrookdale, after a prominent Shropshire, England, ironworks established by fellow Quaker Abraham Darby. Other ironmasters and entrepreneurs quickly followed suit, and by the middle of the eighteenth century blast furnaces were active throughout the Middle Atlantic region (figs. 7, 8).[4]

Labor and material costs for building and operating a blast furnace were substantial, and most ventures required financing from several investors. For example, the stock company created to establish Durham Furnace in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, in 1727 included William Allen, Andrew Bradford, Robert Ellis, George Fitzwater, John Hopkins, James Logan, Jeremiah Langhorne, Thomas Lindsey, Anthony Morris, Griffith Owen, Clement Plumstead, Samuel Powel, Charles Reed, and Joseph Turner. Large-scale production of cast iron also depended on access to water and vast quantities of ore, timber, and limestone, which was used as a flux to remove impurities. According to decorative arts historian John Bivins, eighteenth-century blast furnaces typically required approximately “130 bushels of charcoal to smelt a ton of ore, which yielded about 700 pounds of cast iron. A cord of wood yielded about 40 bushels of charcoal, and a dense acre of hardwoods contained about 20 cords. Since 3 to 4 cords were expended per ton of ore, a furnace easily burned an acre of woodlot each twenty-four hours in blast.” In addition to foundry men, who supervised the production of pigs (ingots suitable for transport) and castings, furnaces employed laborers to mine ore and process limestone, woodcutters and colliers to produce fuel, joiners to make wooden implements, hammer men and blacksmiths to work the iron, potters to make positives for hollow ware, and carvers to make patterns for chimney backs and stoves.[5]

Blast furnaces were typically part of a large industrial complex that included one or more forges, mills, houses for the workmen and ironmaster, storage buildings, and barns (figs. 9, 10). One of the most detailed descriptions is an advertisement for the sale of Batsto ironworks in Burlington County, New Jersey, in the July 2, 1783, issue of the Pennsylvania Gazette:

Offered for sale...a furnace, sufficiently large and commodious to produce upwards of 100 tons of pigs and castings per month...is furnished with an excellent sett of brass patterns for hollow ware, and may be put in blast in a short time.

A Rolling and Slitting Mill, which, from the strength and construction of the works, and large head of water, is capable of great execution.

On the same Dam are also a Saw Mill and small Grist Mill; and the stream...is sufficient to admit of extensive additional works.

A Forge with four fires and two hammers, nearly new, well constructed and in good order, now at work, distant about half a mile from the Furnace, on another well adapted stream; on which is also an excellent, newly built Saw Mill; and near the Forge are some Tenements for workmen, and a large new Coalhouse.

Contiguous to the Furnace is a commodious Mansion house, accommodated with a spacious, well cultivated garden, in which is a well chosen collection of excellent Fruit trees of various kinds, and adjoining it a young bearing orchard of about 2000 apple trees, mostly grafted.

A number of dwelling houses for the best accommodation of tradesmen and others necessarily employed about the works; which, together with the storehouses, barns, stabling, smith shops, nailery, coal house and other convenient buildings, form a considerable village; the whole of which, together with the various works are overlooked from the door of the Mansion House, which stands on a pleasant eminence.

A large and plentiful body of Woodland surrounding the works, and within convenient distance, in which are divers Cedar Swamps, and a considerable quantity of Pine, adapted to Saw Mills; also large bodies of Ore in various parts, which may be raised and collected with little trouble and expense.

About 200 tons of Pig iron on the bank, and near 300 cords of wood ready for coaling, besides a tolerable supply of coals in stock. The river affords a good and easy navigation for sea vessels of burden within a mile, or thereabouts, of the works, and for large scows to the Furnace bank, which offers an easy communication by water with Philadelphia, New York, the West Indies, &c.

It is easy to see why early scholars like Henry Chapman Mercer considered cast-iron stoves and chimney backs to be consummate examples of early American industry.[6]

Casting Iron

Eighteenth-century blast furnaces were essentially large chimneys with sandstone or firebrick inner walls; rubble, sand, or clay shielding; and thick, downward-flaring walls, which were required to support the weight of the molten iron and slag (fig. 11). Charcoal, ore, and limestone were loaded from the top in ratios specified by the ironmaster—a process that continued during the entire time the furnace was in blast. The heat required to melt the ore was achieved by introducing air, forced through the tuyere (a nozzle or pipe) with large water-powered bellows. Periodically, workmen tapped off the slag, then released the molten iron. Pigs and flat objects were cast directly into the sand floor, whereas hollow ware was cast in flasks or other receptacles that could be disassembled for removal of the finished products (fig. 12).

Fewer than a dozen eighteenth-century stove plate patterns from the Middle Atlantic region survive. All of the examples examined for this study are approximately two inches thick and made of mahogany, which was hard enough to withstand abrasion from being pressed into the sand floor, and reinforced with battens to prevent warping (figs. 1, 13, 14). Those used for six-plate stoves are composed of horizontally configured boards with glued mortise-and-tenon joints; those for ten-plate stoves differ only in having vertically configured boards on either side of the door aperture (see fig. 13). Only one end plate pattern is known. It was made of a single board cut from the center of the tree and channeled on the ends to accommodate lifting handles (figs. 15, 16). The Doric columns are turned laminates secured with glue and nails.[7]

Pattern carving was particularly demanding because the craftsman had to avoid undercuts, which would collect sand and disturb the impression when the pattern was lifted out of the floor, and he had to create a level ground much larger than that typically required for relief carving in furniture and architecture (fig. 17). Despite those limitations, some carvers achieved remarkable results. The pattern used to cast the Fairfax chimney back produced one of the most sculptural objects from colonial America (see fig. 5). The horse and lion are naturalistic, whereas their counterparts on contemporaneous British chimney backs are typically diagrammatic and in much lower relief. In nearly every respect, the lion’s head on the Fairfax chimney back is a smaller, two-dimensional profile of that on a monumental pier table Martin Jugiez carved circa 1765 (figs. 18, 19).[8]

Early Philadelphia Carving Traditions and Regional Castings

Two chimney backs dated 1728 are among the earliest castings from the Middle Atlantic region. One has a history of use in Graeme Park, built by colonial governor William Keith in Horsham in 1721, and the other bears the initials of James Logan, who built Stenton in Germantown in 1728 (fig. 20). Given Logan’s association with Durham Furnace, it is likely that his chimney back was cast there. Although the designs of these two objects are very similar, differences in the strapwork, leaves, husks, and date panels are discernible. Neither of the castings is clear enough to determine much about the pattern used to produce it. The ironmaster could have used an imported chimney back as a pattern or commissioned a wooden example from a local tradesman. Few carvers were active in Philadelphia during the 1720s. Anthony Wilkinson, who reported a runaway stonecutter in the November 2, 1727, issue of the American Weekly Mercury, was connected to at least two of the founders of Durham Furnace. In July 1730 he carved a six-foot lion figurehead valued at £4.4 for the ship Tryal, which was owned by Samuel Powell and Clement Plumstead.[9]

A much later chimney back bearing the initials “CG” and two different date plaques supports an attribution of the Stenton chimney back to Durham Furnace (fig. 21). Two patterns were used to produce the design of the former—one for a chimney back like the Logan example and the other for a stove plate whose 1756 date and inscription refer to Indian attacks during the French and Indian War (the inscription on the side plate and a front plate combine to read, “This is the year in which rages the Indian war party”) (fig. 22). The pattern for the “CG” chimney back appears to have been impressed first. The designs on the arch and upper portions of the shoulders are relatively clear, but most of the impression below was smoothed over in preparation for insertion of the stove plate mold. Remnants of the outer “drops” on the lower portion of the chimney back pattern remained, but the impressions of the middle drop and central portion of the side plate pattern were smoothed over more thoroughly. This resulted in a relatively clean surface for impressing the design of the 1746 date panel and crossed swords. The latter date is clearly commemorative and may refer to a military campaign during King George’s War. The 1756 panel is significant because it matches that on a related chimney back emblazoned with the name “Samuel Flowers,” who in that year was ironmaster at Durham Furnace.[10]

The earliest cast-iron objects that can be firmly linked to Philadelphia furniture and architectural carving are armorial chimney backs from Oxford Furnace in Warren County, New Jersey. Built in 1741 by Jonathan Robeston, an ironmaster from Philadelphia, and his partner and financier Joseph Shippen Jr., Oxford was the third furnace established in that colony and the first located near a major source of iron ore. According to an 1881 history of Sussex and Warren counties, the first pigs were cast by March 9, 1743. At least two different chimney backs—both depicting the arms of George II—were cast at Oxford Furnace. The designs and sizes of these models vary, but their patterns appear to have been made at or about that date.[11]

One model, represented by a chimney back dated 1746 (fig. 23), has mantling similar to carving in the Pennsylvania State House, commonly referred to as Independence Hall (figs. 24, 25). Two carvers are known to have worked there. In 1756 Samuel Harding submitted a bill for more than £195.13.11’s worth of architectural carving (begun in 1753), which included 400 feet of molding, 146 banisters, 76 floral appliqués, 58 stair brackets, 33 leaf appliqués, 32 trusses, 30 capitals, 29 garlands, 8 flame finials, 6 stair posts, 5 friezes, 4 angles, 2 tabernacle frames, 2 pediment frames, and 2 keystones with “faces.” The frieze appliqués are composed of a central flower flanked by C-scrolls, leaves, and husks, details also found on a seminal group of Philadelphia case pieces and tables dating from the 1740s (figs. 26, 27). His work in the stair tower is also related to the carving on a larger, and possibly earlier, appliqué over the tabernacle frame in the Assembly Room (see fig. 24). Anthony Wilkinson’s son Brian submitted a bill for £85.8.10’s worth of carving in 1756, but neither the type nor location of his work was specified. Brian was working independently by 1748, when he offered to sell twenty-one months of “a servant man’s time...he is a carver by trade.” Subsequent advertisements in the Pennsylvania Gazette indicate that at least two other indentured carvers worked for Wilkinson during the period when the State House was under construction. On April 5, 1749, he offered a reward for the return of an Irish carver named William Mooney, and on May 26, 1754, he published a similar advertisement for a Dutch carver named Lawrence Perkley.[12]

The second chimney back model cast at Oxford Furnace is represented by an example dated 1747 (fig. 28). This version has a tall arched head and is smaller in height and width, which may explain why its ornamental details are more condensed than those on the other model. The baroque leafage in the mantling is similar to that on the 1746 chimney back, but it is difficult to determine whether the two patterns used for these castings were carved by the same hand or by two related hands. The modeling of the lions and unicorns also differs, but both variants reflect comparable sculptural ability. Assuming that Wilkinson trained with his father, he would have learned to carve figureheads and other three-dimensional ornaments during his apprenticeship. Similarly, the mask-decorated trusses Harding carved for Christ Church in 1753 document his ability to produce sculptural work (fig. 29).[13]

Given the stylistic and technical relationships between the carving in the State House, Wilkinson’s advertisements for runaway indentured workmen, and the probability that Harding also employed journeymen and took apprentices, the armorial patterns used at Oxford Furnace are best understood as products of the Wilkinson-Harding school. That designation could also be applied to the front plate of an early Franklin stove (fig. 30). The first examples of that form appear to have been cast at Mount Pleasant Furnace in Berks County, Pennsylvania, and Warwick Furnace in Chester County. A September 23, 1742, entry in a ledger for Coventry Forge, which served Mount Pleasant, recorded a charge of £23.3.2 for “seven small new-fashioned fireplaces.” Two years later, Benjamin Franklin published An Account of the New Invented Pennsylvania Fire-places, which included an engraving of his hearth stove and instructions for its manufacture (fig. 31). That design was clearly the inspiration for the cast example, but the carver who produced the pattern for the front plate inverted the banner and incorporated his own style of leafage. The closest cognates for that work are the frieze appliqué in the Assembly Room of the State House and the rail carving on a tea table said to have been among the original furnishings of Graeme Park (figs. 32-35).[14]

Pattern Carving and Cast Iron in the Rococo Style

The earliest castings in the rococo style are side plates and an end plate from a jamb stove bearing the inscription “THE SAUTAN” and the date “1760” (figs. 36, 37). Two plates were found near Lebanon, in Hunterdon County, New Jersey, about twenty-two miles from the site of Oxford Furnace. The craftsman who produced the patterns for these plates also carved a group of contemporaneous Philadelphia chairs, some of which have reputed Penn family connections (fig. 38). His carving is stylistically aligned with British work of the mid- to late 1740s, but the scale of the work varies from component to component and is not fully integrated into the overall design of the chair (figs. 39, 40). As the carving on the crest and knees of the chairs reveals, many of the leaves have awkwardly outlined edges, irregular shading, and leaves that curl and hook in an exaggerated manner. Very few examples of this carver’s work survive, which suggests that he may have been an indentured tradesman who ran away or a journeyman who relocated to another city.[15]

In The Bible in Iron, Henry Mercer speculated that the inscription “THE SAUTAN” might be an abbreviation for “THE SALUTATION,” or a reference to the Salute, a dance figure mentioned in Randle Holme’s Academy of Armor and Blazon (1701). He also noted that “THE SAUTAN” was one “of the few English inscriptions thus far found cast upon jamb stoves.” Rococo ornaments are even more rare on jamb stoves, most of which feature religious, moralistic, or bucolic scenes or have motifs associated with Pennsylvania-German vernacular art. Colonists of Germanic descent likely introduced jamb stoves to the Middle Atlantic region and probably accounted for a majority of that form’s ownership. Many iron furnaces offered jamb stoves with Germanic ornament concurrent with six- and ten-plate stoves with Anglo rococo and neoclassical designs. Philadelphia craftsmen were keenly aware of the need to serve both the English- and German-speaking markets, as indicated by the use of labels in both languages.[16]

Most of the surviving six- and ten-plate stoves with rococo designs were cast from patterns carved between 1765 and 1785. Several immigrant carvers were active in Philadelphia by the mid-1760s, including Nicholas Bernard, Martin Jugiez, Hercules Courtenay, John Pollard, and James Reynolds. In the November 25, 1762, issue of the Pennsylvania Gazette, Bernard and Jugiez advertised “Carving in Wood or Stone and Gilding...in the neatest Manner.” Courtenay and Pollard came to Philadelphia three years later under indentures to cabinetmaker Benjamin Randolph. The former probably completed his term by May 16, 1769, when he married Mary Shute. Pollard, who appears to have been Randolph’s principal carver and received payments from him as late as 1779, advertised independently in March 1773. James Reynolds arrived in Philadelphia on August 21, 1766. The following month he advertised architectural, ship, and furniture carving from “his house in Dock Street opposite Lodge Alley.” All of these carvers worked until the 1780s, and all furnished casting patterns for regional iron furnaces.[17]

Two of the earliest chimney backs associated with an immigrant carver are from Aetna Furnace (figs. 41, 42), which was one of four ironworks established by Charles Read in Burlington County, New Jersey. Read was one of the most politically powerful men in that colony, a status that helped him acquire or secure the rights to vast quantities of woodland, iron ore deposits, and water access. In only two years, he built Atison Forge (1765), Batsto Furnace (1766), Aetna Furnace (1766–1767), and Taunton Forge (1766–1767). Read’s grand “iron works scheme” quickly took a toll on his finances and health. On June 30, 1773, the Pennsylvania Gazette reported that he had left for the West Indies “for the recovery of his health, as well as for securing and recovering some large sums of money due to him” and instructed “all persons who have any demands against him” to submit their accounts to either his son Charles at Aetna Furnace, Daniel Ellis at Burlington, or Thomas Fisher at Philadelphia.[18]

Charles Read Jr. has been credited with changing the furnace name from “Etna” to “Aetna” after his father’s departure, which has led some scholars to postulate that the patterns for the surviving chimney backs were carved between 1773 and 1774. However, advertisements in the Pennsylvania Gazette indicate that “Aetna” was in use earlier. On July 4, 1771, the elder Read reported that two servant lads had run away from “Aetna Furnace.” That same designation for this ironworks appeared in another runaway advertisement the following year. Based on those documents and the absence of neoclassical details on the chimney backs, a date range of 1767–1775 is plausible for both patterns.[19]

The scrolls and leaves on the Aetna chimney backs echo those in furniture carving documented and attributed to James Reynolds’s shop. On both chimney backs, the animals stand on a rocky surface surmounting C- and S-scrolls similar to those on several pier glasses, including the painted example illustrated in figure 43 and a parcel gilt frame commissioned by Philadelphia merchant John Cadwalader in 1771. The stag chimney back is the more elaborate of the two castings, featuring acanthus leaves in the upper corners and clusters of flowers and leaves rising from the rocks below. All of the elements in those clusters are repeated on Reynolds’s frames and the pediment of a desk-and-bookcase attributed to his shop.[20]

Reynolds also carved at least one pattern for Elizabeth Furnace. The example illustrated in figure 44 has an upper banner inscribed “BERT COLEMAN,” for Robert Coleman, an Irish immigrant who arrived in Pennsylvania in 1764. After working briefly as a clerk at Hopewell Forge in Lancaster County, he was hired by ironmaster James Old, who managed several furnaces and forges during his career. Coleman began working at Reading Furnace in 1767 and married Old’s daughter Ann six years later. Soon after his marriage, Coleman began developing his own iron business. He leased Elizabeth Furnace in 1776 and acquired it by 1784, the same year he purchased Speedwell Forge from his father-in-law. Although the urn on the pattern might suggest a post-Revolutionary production date, the “antique” taste was well established in London when Reynolds immigrated and was beginning to appear in Philadelphia decorative arts during the 1770s. The leaf carving on the pattern is consistent with his earlier work, as comparison of the clusters rising from the lower scrolls and those in the upper corners of the Cadwalader pier glass frame reveals (figs. 45, 46).[21]

No patterns by Bernard and Jugiez survive, but the Fairfax chimney back attests to the high level of their work in that area of the carving trade (fig. 5). Their firm was also exceptional for offering stone carving and for marketing its products and services outside the Philadelphia region. Beginning in the late 1760s Bernard and Jugiez placed advertisements in newspapers in Philadelphia, New York, and Charleston, the latter of which mentioned “the King’s Coat-of-Arms carved in wood, suitable for a State House or Court-House.” In 1768 the firm received £73.10 for “the King’s Arms in the Council Chamber” of the newly constructed South Carolina State House. That payment would have been approximately £17.17 in Philadelphia currency, indicating that the armorial was probably larger than the pattern for the Fairfax chimney back and most likely had painted and gilded decoration.[22]

The Fairfax chimney back was cast at Marlboro Furnace, located in the Shenandoah Valley southeast of Winchester, Virginia. Although that site was approximately two hundred miles from Philadelphia, Marlboro’s owner was born in the Quaker city and maintained close ties with family and business associates there. Isaac Zane Jr.’s entrée into the iron business occurred at age twenty-four, when he purchased interest in a furnace established near Winchester, Virginia, by John Hughes, Samuel Potts, and John Potts Jr., all of whom owned similar businesses in Pennsylvania. Zane subsequently bought out all his partners and was sole owner of Marlboro Furnace by 1768. Like many Pennsylvania ironmasters, he catered to a culturally diverse market. Marlboro Furnace produced Germanic jamb stoves with religious and bucolic scenes as well as six-plate stoves and chimney backs with Anglo-rococo ornament.[23]

An inventory of Marlboro Furnace taken in 1794–1795 lists several patterns but does not describe their design (with the exception of the Fairfax example) or identify their maker:

1 Franklin Stove pattern 6.0.0

1 10 plate Stove do. 6.0.0

1 £4 open do. Mahogany Carv’d 4.0.0

1 do. do. do.more plain/ 2.0.0

1 £3 pipe ditto 3.0.0

1 £3 open do. Mahogany Carv’d 3.0.0

1 do. do. do. plain 1.10.0

1 £3 pipe do. plain 3.0.0

1 Fairfax Arms back wall plate pattern 8.0.0

Bernard and Jugiez may have produced one or more of the “Mahogany Carv’d” examples. In a March 1776 letter to his brother-in-law and Philadelphia agent John Pemberton, Zane wrote, “I should be glad to pay Bernard & Jugiez, but I have not an exact account of the Debt.” A small group of stove plates and a chimney back marked “ZANE MARLBORO FURNACE” have recovery histories in the Winchester area and appear to have been cast from a pattern supplied by their firm (figs. 47, 48). Those objects feature a central vase with a gadrooned body, scalloped leafage around the mouth, handles composed of opposing C-scrolls, and an asymmetrical arrangement of flowers and leaves. A three-dimensional version of that vase was used for the central ornament on the pediment of a high chest attributed to Bernard and Jugiez, and the leaves around the mouth relate to the petals of half-flowers on trusses they furnished for Samuel Powel’s town house (fig. 49) as well as other architectural and furniture work documented and attributed to their firm. Similar vase and flower motifs can be found in English design books, including Matthias Lock and John Copland’s A New Book of Ornaments (1752, 1768), Thomas Chippendale’s Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (1754, 1755, 1762), and Thomas Johnson’s One Hundred and Fifty New Designs (1758 [untitled], 1761). All of these publications were present in Philadelphia during the period when Marlboro Furnace was active, and some may have been among the books in Isaac Zane’s library, which was one of the largest in colonial America.[24]

A side plate from a six-plate stove cast marked “POTTSGROVE” (fig. 50) and a chest-on-chest made by cabinetmaker Thomas Affleck for Germantown merchant David Deshler have similar urns (figs. 51, 52), and the C- and S-scroll border of the plate has passages like those on tympanum appliqués of double case pieces, clocks, and overmantels documented and attributed to Bernard and Jugiez. Like many Philadelphia cabinetmakers, Affleck subcontracted carving to specialists. His bill to John Cadwalader for eighteen pieces of furniture made between October 13, 1770, and January 14, 1771, noted payments of £24.4 to Bernard and Jugiez and £37 to James Reynolds.[25]

The “POTTSGROVE” mark clearly refers to one of the ironworks owned or managed by the Potts family. Thomas Potts was the first member of his family to engage in that business. He acquired a share in Colebrookdale Furnace in 1725 and subsequently built Mount Pleasant Furnace. His son John became manager of Mount Pleasant after his father died in 1752 but soon moved to run Warwick Furnace. John’s mother-in-law, Ann Nutt, had given him and his wife, Ruth, half interest in the latter furnace in 1745. Warwick was one of the largest furnaces in Pennsylvania. During the last half of the eighteenth century, it produced pig iron for the Potts family’s forges and possibly decorative castings like the Pottsgrove stove plate as well. The term “Pottsgrove” first appears in John’s business accounts during the 1740s, and he subsequently used that term in reference to other interests. In 1752 he built Pottsgrove Manor on 945 acres of land he purchased from Samuel McCall the preceding year, and in 1761 John began laying out the town Pottsgrove (later called Pottstown). He died in 1768, leaving his estate to his children. Presumably the stove plate illustrated in figure 50 was cast at one of the Potts family’s furnaces after that date. The earliest known advertisement by Bernard and Jugiez was in 1762.[26]

Two scroll-foot side chairs (from a set of at least six) attributed to Bernard and Jugiez were reputedly among the furnishings of an Odd Fellows Hall in Pottstown (fig. 53). The chairs are based on a design in Chippendale’s Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (pl. 12 in the 1754 and 1755 editions; pl. 14 in the 1762 edition) (fig. 54) and are among the most sculptural examples of eighteenth-century American seating. Given the probable cost of the set and their recovery history, it is plausible that they descended in the Potts family.[27]

A stove plate formerly in the collection of the Moravian Young Men’s Missionary Society in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, may also have been cast from a pattern carved in Bernard and Jugiez’s shop (fig. 55). The plate depicts “The Fox and Crane,” which was also used on a later example from Batsto Furnace. That fable and “The Dog and Piece of Meat” appear as needlework designs for “Horse Fire Screens” illustrated on pl. 127 in the first and second editions of the Director. The central scene and scrollwork border of the plate relate to other carving associated with Bernard and Jugiez, including the high chest illustrated in figures 56 and 57 and an appliqué in Cloverfields in Queen Anne’s County, Maryland. The design sources for the furniture and architectural carving were plates 21 (fig. 58) and 30 respectively in Johnson’s One Hundred and Fifty New Designs.[28]

The two craftsmen most closely associated with the introduction of English rococo designs to Philadelphia were Hercules Courtenay and John Pollard. Courtenay served his apprenticeship with Thomas Johnson, one of the leading proponents of the rococo style in London. Johnson’s designs often include details based on Aesop’s fables, which were illustrated by Wencelaus Hollar, Francis Barlow, Elisha Kirkhill, and others (fig. 59). Courtenay followed in his master’s footsteps when he carved a representation of “The Dog and Its Reflection” (also “The Dog and Piece of Flesh” and “The Dog and Shadow”) on an end plate pattern for a ten-plate stove marked “W.H. STEIGEL / ELIZABETH FURNACE” and dated 1769 (figs. 60, 61) and a chimneypiece tablet installed in Chief Justice Samuel Powel’s Philadelphia town house in 1770 (fig. 62). Details from Johnson’s A New Book of Ornaments also occur in furniture carving associated with Courtenay, including the so-called Madame Pompadour high chest in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[29]

In 1769 the ironmaster of Elizabeth Furnace was Henry William Stiegel, a German émigré who arrived at Philadelphia in 1750. Six years later, he partnered with Charles Stedman, Alexander Stedman, and John Barr to purchase an ironworks near Manheim in Lancaster County. The investors subsequently built a new furnace on the site, and Stiegel named it after his first wife, Elizabeth. The patterns for the stove illustrated in figure 60 were carved in the year when Stiegel was expanding his iron- and glassmaking businesses and Courtenay opened his own shop. In the summer of 1769 Courtenay reminded the public that he had trained in London and offered “all Manner of Carving and Gilding in the newest Taste, at his house between Chestnut and Walnut on Front.” As Morrison Heckscher has noted, 1769 was also the year when Samuel Powel purchased and began renovating the house of Stiegel’s former partner Charles Stedman. Stoves like the example illustrated in figure 60 may have appealed to the owners of Philadelphia houses, since their cast decoration would have resonated with contemporaneous furniture and architectural ornament from that city’s cabinet and carving shops.[30]

Stiegel produced at least two other stoves with Anglo-rococo ornament. One model has side plates with a classical bust framed by a wreath and Masonic tools in the lower corners (fig. 63) and a front plate decorated with a shield and trophies. Although there is insufficient evidence to support an attribution, Courtenay would have to be considered a candidate for the pattern carver. Stiegel commissioned patterns for another stove from Courtenay the same year (see fig. 60), and the latter was capable of producing highly sculptural work. John Cadwalader paid Courtenay £8.10 for a chimneypiece tablet depicting the “Judgment of Hercul [es]” in 1770 and £2.5 for “6 Busts” for his coach in 1773. The complexity and quality of the tablet are suggested by its price, which was ten shillings more than the pattern for the Fairfax chimney back (see fig. 5).[31]

Representing the other Stiegel stove is a side plate with an asymmetrical rococo urn, scrolling foliage, and the date 1769 (fig. 64). The letters “EGE” were part of a larger mark that read “H. E. STIEGEL” and do not refer to the ironmaster’s nephew George Ege, who purchased Charles Stedman’s interest in Elizabeth Furnace in 1782. Stiegel’s full mark is visible on three other stove plates of the same design. The scrollwork and floral elements on these plates share more details with work from Bernard and Jugiez’s shop than with carving by Courtenay.[32]

Courtenay may have carved the pattern for the side plate of a six-plate stove cast at Reading Furnace in Chester County, Pennsylvania (fig. 65). James Old, whose name appears on the upper banner, was master of the ironworks from 1772 to 1778. With the exception of the center panel (which occupied the space for the door when used for casting ten-plate stoves), the design is almost identical to that of the side plates of the Elizabeth Furnace stove (figs. 60, 66). The hands, scales, sheaf of wheat, and ship on the panel are details from the Seal of Philadelphia, which is represented in shield form on the end plate of an early jamb stove (see fig. 8). As Morrison Heckscher observed, the pattern for the center panel appears to have been reused. Elements of the design disappear at the bottom and sides, indicating that a larger pattern—possibly one for the end plate or side plate of a six-plate stove—was reduced in size.[33]

A six-plate stove marked “MARK BIRD HOPEWELL FURNACE” is even more elaborate than the examples from Stiegel’s ironworks (figs. 67-69). Bird built Hopewell Furnace in Union Township in Berks County, Pennsylvania, in 1771 and subsequently established or invested in ironworks (including forges) in other areas of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, Virginia, and North Carolina. It is not known when Hopewell first went into blast, but it is possible that the 1772 date on the side plates commemorated that event. The stove and individual side plates recorded for this study are not clear enough to determine if the patterns used to cast them were carved by Courtenay or Pollard. Both men appear to have had similar training in London, and they seem to have assimilated aspects of each other’s working style while together in Randolph’s shop. The iron maker’s name appears in Randolph’s account book several times between 1771 and 1779, but the work the latter’s shop provided is not specified.[34]

No documented carving by Pollard is known, but strong circumstantial evidence suggests that he furnished much of the architectural ornament for parlors in the Stamper-Blackwell House in Philadelphia and the Ringgold House in Chestertown, Maryland. This work was probably done during his tenure in Randolph’s shop, since both interiors also have carving attributable to Courtenay, and the Stamper-Blackwell parlor has ornaments by a third hand. The frieze appliqués on the chimneypiece in the Ringgold parlor are derived from plate 2 in Johnson’s A New Book of Ornaments (fig. 70), which comprised a set of six engravings “Designed for Tablets & Friezes for Chimneypieces.” Pollard and Courtenay also had access to Chippendale’s Director. Randolph’s trade card has details taken from that publication, and the reclining figure on a scroll-foot side table with carving attributed to Pollard (fig. 71) was derived from plate 152 in the third edition. The table descended in the family of John Cadwalader. On October 10, 1769, he credited his brother Lambert £94.15 for “B. Randolph[s] acct for Furniture” and £30 for “2 marble Slabs etc. had of C. Coxe.” As decorative arts scholar Andrew Brunk noted, Pollard received £180.24 for work performed between November 1768 and September 1769, and he was last paid ten days before the entry was made in Cadwalader’s waste book. Although the patterns for the Hopewell stove were carved later, they were clearly by the same hand that carved the sideboard table (figs. 72, 73).[35]

Pollard was working independently by January 18, 1773, when he took George Connell as an apprentice. Two months later, the Pennsylvania Gazette reported, “POLLARD and BUTTS...At the sign of the CHINESE SHIELD”...nearly opposite Carpenter’s HALL...do all manner of CARVING in the House, Cabinet, Coach, and Ship way.” Pollard’s partner may have been the same Richard Butts mentioned in two entries in Benjamin Randolph’s account books, although there is no evidence that Butts and Randolph had any significant business relationship. Other than Courtenay, the only other carver who appears to have worked with Pollard in Randolph’s shop was the anonymous craftsman known today as the “Garvan high chest carver.” The latter carver was one of the most highly skilled and prolific artisans active in eighteenth-century Philadelphia, and his work influenced that of several competitors, including Pollard (figs. 74, 75).[36]

From 1772 until the mid-1780s Pollard’s shop furnished patterns for several regional ironworks. The side plate illustrated in figure 76 was cast after 1779, when Richard Backhouse, whose company name is emblazoned on the banner, purchased Durham Furnace in the dispersal of loyalist Joseph Galloway’s seized property. Backhouse relinquished ownership by 1791 and died two years later. The lower half of the plate depicts a rural scene in which a fox is fleeing from a farm with a slain goose, a design replicated on a frieze appliqué attributed to Pollard (fig. 77). Both compositions were derived from the title page of Animals of Various Species Accurately Drawn by Francis Barlow, part three of his Various Birds and Beasts Drawn from Life (ca. 1660–1670) (fig. 78). The upper half of the plate is decorated with scrolls, leaves, and flowers similar to those on a fragmentary casting pattern that descended in the Henry family of Boulton, Pennsylvania, with a history of having been used at Durham Furnace (fig. 79).[37]

The same carver produced the patterns for an unmarked side plate from a six-plate stove and three different, but closely related, end plates (figs. 80-83). The chinoiserie figures were taken from chimneypiece designs illustrated on plates 4 (end plate) and 7 (side plate) in Lock and Copeland’s A New Book of Ornaments (figs. 84, 85). On the end plate illustrated in figure 81, the torso of the flautist and surrounding scrollwork are represented in mirror image. The end plate illustrated in figure 83 is even more complex, featuring a flautist sitting in a chair with rocks, leaves, and scrolls below. Two of the end plates (see figs. 81, 82) and a side plate like the example illustrated in figure 80 have recovery histories in the upper Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, but since none of the examples is marked, it is impossible to determine if they were cast there or at a Pennsylvania furnace.[38]

Pollard appears to have been the principal pattern carver for Batsto Furnace. By 1768 Charles Read had sold all of his interest in that ironworks to Philadelphia brewer Reuben Haines, New York merchant Walter Franklin, and Burlington entrepreneurs John Cooper and Richard Wescoat. During the fall of 1770 Philadelphia merchants Charles Cox and Charles Thompson bought out all of their interests. Thompson sold his shares to Cox three years later, and the latter maintained ownership until 1778, when Thomas Mayberry paid him £40,000 for Batsto. Approximately six months later, Mayberry sold the furnace to Joseph Ball, who had managed Batsto during Cox’s ownership. Ball subsequently sold shares in the business and, beginning in 1783, advertised the ironworks for sale. Although Batsto sold in July of the following year, “Ball...as well as [Charles] Petit and [John] Cox retained an interest...for years to come.”[39]

Batsto Furnace began casting stove plates before the American Revolution. On June 5, 1775, Cox advertised:

MANUFACTURED at BATSTO FURNACE, in West New Jersey, and to be sold, either at the Works, or by the Subscriber, in Philadelphia, a great variety of iron pots, kettles, Dutch ovens, and oval fish kettles, either with or without covers, skillets of different sizes, being much lighter, neater and superior in quality to any imported from Great Britain; potash, and other large kettles, from 30 to 125 gallons; sugar mill gudgeons, neatly rounded, and polished at the end; grating bars of different lengths; grist mill rounds; weights of all sizes, from 30 to 56; Fullers plates; open and close stoves, of different sizes; rag wheel irons for sawmill; pestles and mortars; sash weights, and forge hammers, of the best quality. Also Batsto Pig Iron as usual, the quality of which is too well known to need any recommendation.

An example likely derived from Francis Barlow’s engraving of Aesop’s fable “The Fowler and the Ringdove” (also called “The Bird Hunter and the Snake”) (figs. 86, 87) is marked “17 BATSTO 70,” which suggests that it dates from the period when John Cox and Charles Thompson owned Batsto Furnace and Pollard was working in Benjamin Randolph’s shop. Thompson was a client of Randolph and owned a set of elaborate chairs with carving attributed to Pollard. The leaves on the ears of those chairs, as well as those on another set owned by Philadelphia merchant David Deshler (figs. 88, 89), relate closely to the foliate ends of the banner on “The Fowler and the Ringdove” plate (fig. 86) as well as those on other castings associated with Pollard’s shop.[40]

The chimney back illustrated in figure 90 is the only recorded example from Batsto Furnace. Probably dating from the first half of the 1770s, it features a rococo urn with leaves and flowers surmounting a plinth-like structure composed of C- and S-scrolls—a design with cognates in the tympanum appliqués of contemporaneous Philadelphia high chests, double chests, and tall clock cases. The garlands at either side have passages almost identical to those on a looking glass attributed to Pollard (figs. 91, 92) as well as to individual elements, rendered in more sculptural form, in architectural work likely done during his tenure in Randolph’s shop.

The shop tradition Pollard established probably continued after his death in 1787. That theory is supported by the side plate from a ten-plate stove decorated with a foliate banner similar to those associated with earlier castings from patterns attributed to him along with the Great Seal of the United States, which came into use in 1782 (fig. 93). Valentine Eckhart built Sally Ann Furnace in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, in 1791, four years after Pollard’s death.[41]

Pattern Carving and Cast Iron in the Early Neoclassical Style

Among the earliest neoclassical objects imported into the colonies were three cast-iron stoves designed and made by Abraham Buzaglo of London for use in the Governor’s Palace and House of Burgesses in the Capitol Building at Williamsburg, Virginia. All were installed in 1770, but only one example survives (fig. 94). Buzaglo published a design for another neoclassical stove contemporaneously (fig. 95) and made a related example for John Sackville, 3rd Duke of Dorset in 1774. Acclaimed for their innovation, efficiency, and “elegance of workmanship,” Buzaglo’s stoves were consummate expressions of the neoclassical taste in cast iron. The examples sent to Williamsburg likely influenced local tastes and made an impression on visitors from other colonies, including prominent Philadelphians.[42]

Philadelphians became interested in classical cultures during the middle of the eighteenth century. James Logan purchased a fourth-century Italian skyphos from a London dealer in 1740, and several of his contemporaries—including Samuel Powel and John Morgan—visited Herculaneum and Pompeii while on the grand tour. Those who were unable to travel abroad had access to the Library Company of Philadelphia’s copy of Pierre d’Hancarville’s Antiquités étrusques, grecques, et romaines tirées du cabinet de M. Hamilton (1766–1767), which illustrated artifacts recovered from those sites. Subscribers could also see how classical objects were influencing the new “antique” taste in publications like The Works in Architecture of Robert and James Adam. The Library Company owned a copy of volume one by 1775 but apparently failed to acquire the second volume.[43]

Neoclassical designs began to appear in Philadelphia decorative arts before the American Revolution. Conduits for the new style included publications like those of the Adam brothers, émigré craftsmen, and imported goods. Silversmith Richard Humphreys made a neoclassical urn for the Continental Congress as a presentation piece for Charles Thompson in 1774, and it is likely that local carvers, including those who produced patterns for regional furnaces, began working in that style at approximately the same date (figs. 96, 97).[44]

A stove plate marked “MOUNT AETNA” is one of the earliest castings with neoclassical ornament (fig. 98). Samuel and Daniel Hughes built that furnace near Hagerstown, Maryland, and reportedly put it into blast during the mid-1770s. The design of the plate suggests that its pattern was carved between 1775 and 1785, in the shop of Pollard or a craftsman associated with him. The same date range and attribution can be assigned to the mahogany pattern illustrated in figure 1 and a six-plate stove cast and used at Batsto Furnace (figs. 1, 99, 100). Like the Mount Aetna plate, the pattern and side plates of the stove have banners with foliate ends similar to those on castings dating as early as 1770 (see fig. 86) and neoclassical details, most notably, urns with handles composed of leaves that curl in almost circular arcs (which are tighter than those in most rococo compositions), and an unusual motif with a vasiform base and an upper section resembling the head of a Roman axe (figs. 101-103). Robert Adam used a more elaborate version of this composite design in a hand-colored engraving of the Countess of Bute’s dressing room in Luton Hoo, Bedfordshire, England, in 1769 (fig. 104).[45]

The central ornament on a stove plate marked “P. GRUBB / G. EGE” is more closely aligned with Adam’s designs (fig. 105). Its pattern may have been carved circa 1782, since another stove plate marked “PETER GRUBB AND GEORGE EGE” bears that date. The leafage is very similar to that on an end plate decorated with an arabesque with an anthemion at the top (fig. 106) and suggests that both objects were from the same model of stove, which appears to have been fully in the neoclassical style.[46]

Vestiges of the rococo style persisted in pattern carving of the 1780s and 1790s, as indicated by the leafage on a stove marked “JOHN PATTON / BERKSHIRE” (figs. 107, 108). Patton owned Berkshire Furnace from 1764 to 1789, when he agreed to sell his business to George Ege (title transferred the following July). The end plate of the stove features an ovoid classical urn with a cabochon and asymmetrical acanthus below, and the side plates have banners with exquisitely detailed leaves, drapery festoons, and figures—Britannia adjacent to an Ionic column, an angel blowing a trumpet, and an Indian seated with one hand holding a bow and the other resting on a dog’s head. The drapery relates very closely to that on the pediment of a tall case clock likely carved in Pollard’s shop (figs. 109, 110).[47]

Like Pollard, several of the carvers active after the American Revolution were immigrants who had arrived during the 1760s, learned their trades when the rococo style was at its peak, and gradually came to embrace the neoclassical taste. James Reynolds and Martin Jugiez participated in the 1788 Grand Federal Procession in Philadelphia, which had a classical edifice as its focal point and elaborate displays and “cars” representing the city’s trades:

Before the car walked the artists of several branches, preceded by Mr. Cutbush, ship carver, and Mr. Reynolds and M. Jugiez, house furniture and coach carvers, with young artists going before, decorated with blue ribbands round their necks, to which were suspended medallions, blue ground, with ten burnished gold stars, one bearing a figure of Ceres, representing agriculture; another Fame, blowing her trumpet, announcing to the world the Federal Union; the middle one carrying a Corinthian column complete, expressive of the domestick branches of Carving.

As the century wore on, carvers found increasingly fewer outlets for their work, as the federal style and later iterations of neoclassicism came into vogue and craftsmen like Robert Wellford began mass-producing composition ornaments.[48]

Although underrepresented in museum and private collections, stove plates and chimney backs cast from Philadelphia-carved patterns are among the most significant and sophisticated examples of American rococo and neoclassical decorative art. These objects are also an important resource for scholars interested in the stylistic vocabularies and techniques of individual carvers and their shop traditions, the influence of British design books and other published sources, and patronage. Many account books, ledgers, and other documents pertaining to the early furnaces and forges of the Middle Atlantic region survive, and it is hoped that this essay encourages further exploration of them.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For assistance with this article, the author thanks Cory Amsler, Gavin Ashworth, Philip Bradley, Sophia Brothers, Frances Delmar, Sarah Good, Angika Kuettner, Jenny Martin, Alan Miller, Lisa Minardi, John Morsa, Susan Newton, Don Oxenhandler, Lauri Perkins, Sumpter Priddy, Valerie Seiber, Leah Sutherland, Matt Thompson and Ann Wagner.

New York Mercury, May 31, 1762, as quoted in The Arts and Crafts in New York, 1726–1776: Advertisements and News Items from New York City Newspapers, Collections of the New York Historical Society, compiled by Rita S. Gottesman (1938; reprint, New York: Da Capo Press, 1970), p. 124. Pennsylvania Gazette, November 25, 1762. Virginia Gazette, June 20, 1755, as quoted in Wallace B. Gusler, Furniture of Williamsburg and Eastern Virginia, 1710–1790 (Richmond: Virginia Museum, 1979), p. 61.

Nicholas B. Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur in Philadelphia: The House and Furniture of General John Cadwalader (Philadelphia: Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1964), p. 143. Stucco ornaments associated with colonial American carvers are extremely rare, but a few are associated with Virginia carver William Bernard Sears. He carved a chimneypiece in the small dining room at Mount Vernon in 1775 and appears to have produced molds for the “stucco man,” who provided all the decoration above the mantel shelf. Luke Beckerdite, “William Buckland and William Bernard Sears: The Designer and the Carver,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 8, no. 2 (November 1982): 29–40. The stucco ornaments directly above the mantel shelf share details with the carving below. Letters from Lund Washington to his cousin George indicate that the stucco man was working at the same time as Sears. On October 15, 1775, Lund reported that the stucco man “can plaster in one day more than our two men can in a week.” Two months later he wrote, “I have sent the plasterer back to Colonel Lewis. I think the dining room very pretty” (Betsy Panhorst to Luke Beckerdite, October 15, 1985, citing letters among the Toner transcripts in the George Washington Papers, Library of Congress). More elaborate stucco ornaments by the same craftsman are in Lewis’s house Kenmore. For the King bill, see Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur, p. 77. Donald L. Fennimore, Metalwork in Colonial America: Copper and Its Alloys (Wilmington, Del.: Winterthur Museum, 1996), p. 136. Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur, p. 38. To put the cost of the andirons in perspective, the standard price for a mahogany sofa frame with “fret on the feet and rails, and carved mouldings” was £10.10 in 1772 (Price of Cabinet and Chair Work [Philadelphia: printed by James Humphreys Jr., 1772]).

John Bivins Jr., “Isaac Zane and the Products of Marlboro Furnace,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 11, no. 1 (May 1985): 43. Luke Beckerdite, “Philadelphia Carving Shops, Part II: Bernard and Jugiez,” Antiques 128, no. 3 (September 1985): 509–11. Luke Beckerdite and Alan Miller, “A Table’s Tale: Craft, Art, and Opportunity in Eighteenth-Century Philadelphia,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2004), pp. 32–33.

Jonathan Dickinson, Letter Book, 1715–1721, p. 111, Library Company of Philadelphia, http://explorepahistory.com/kora/files/1/4/1-4-14A-71-ExplorePAHistory-a0k1i3-a_735.pdf. See also Henry C. Mercer, The Bible in Iron: Pictured Stoves and Stoveplates of the Pennsylvania Germans (1914; revised, corrected, and enlarged by Horace M. Mann, Doylestown, Pa.: Bucks County Historical Society, 1961), pp. 104–5.

See http://durhamhistoricalsociety.org/history3.html for a short history of the establishment of Durham Furnace. Bivins, “Isaac Zane,” pp. 23–25.

Mercer, Bible in Iron.

For more on the end plate pattern, see ibid., p. 169, nos. 14–15.

For more on the pier table and its relationship to other work documented and attributed to Jugiez, see Beckerdite and Miller, “Table’s Tale,” pp. 30–40.

The Graeme Park chimney back is illustrated in Mercer, Bible in Iron, no. 385. For Anthony Wilkinson’s bill, see R. Curt Chinnici, “Pennsylvania Clouded Limestone: Its Quarrying, Processing, and Use in the Stone Cutting, Furniture, and Architectural Trades,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2002), p. 122 n. 14.