Card table, labeled by Adam Hains (1768–1846), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1795. Mahogany, satinwood, and mixed-wood and mastic inlay with oak (hinged rail) and white pine (inner frame). H. 29 1/2", W. 35 1/4", D. 18". (Courtesy, Steven M. Still Antiques; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

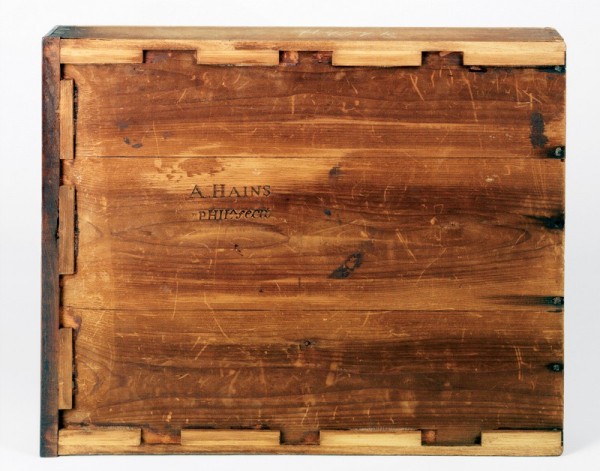

Pembroke table, branded by Adam Hains (1768–1846), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1788. Mahogany with tulip poplar, white cedar (glue blocks), and white oak (drawer support). H. 28", W. 20 1/2" (closed), D. 29 3/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, 1957.669; photo, Laszlo Bodo.)

Detail of the brand on the drawer of the table illustrated in fig. 2. (Photo, Laszlo Bodo.)

Detail of the drawer construction of the table illustrated in fig. 2. (Photo, Laszlo Bodo.)

Detail of the drawer underside of the table illustrated in fig. 2. (Photo, Laszlo Bodo.)

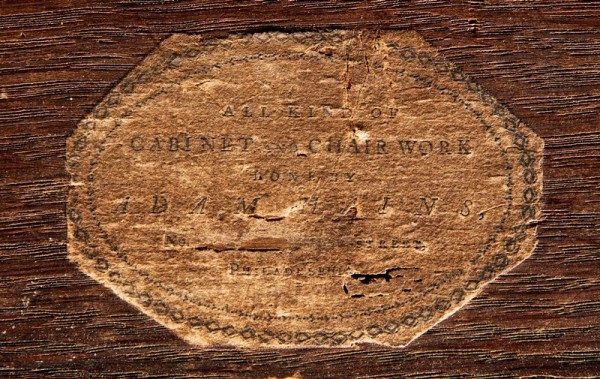

Detail of the label on the table illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

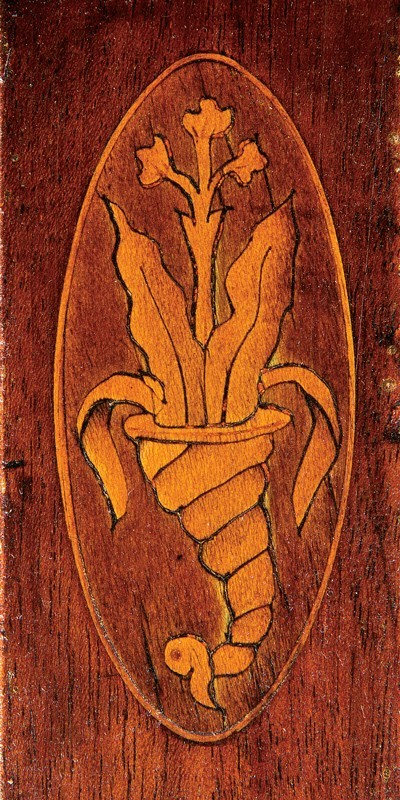

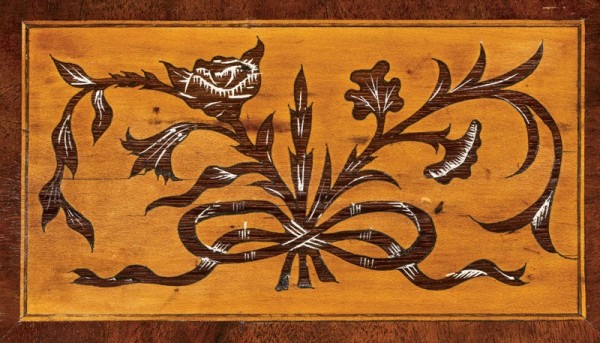

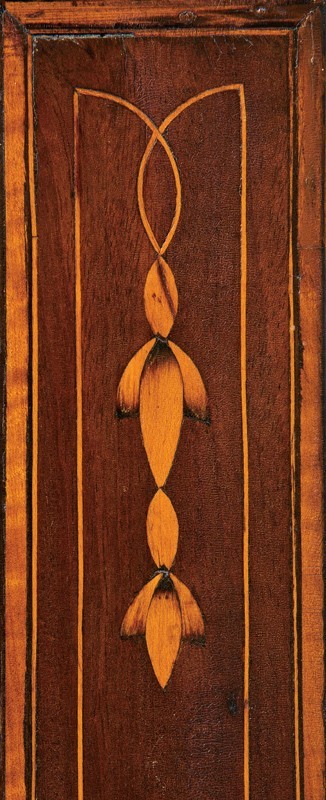

Card table, attributed to Adam Hains (1768–1846), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1795. Mahogany, satinwood, and mixed-wood and mastic inlay with oak (hinged rail) and white pine (inner frame). H. 29 1/2", W. 35 1/4", D. 18". (Courtesy, Steven M. Still Antiques; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the floral inlay on the table illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

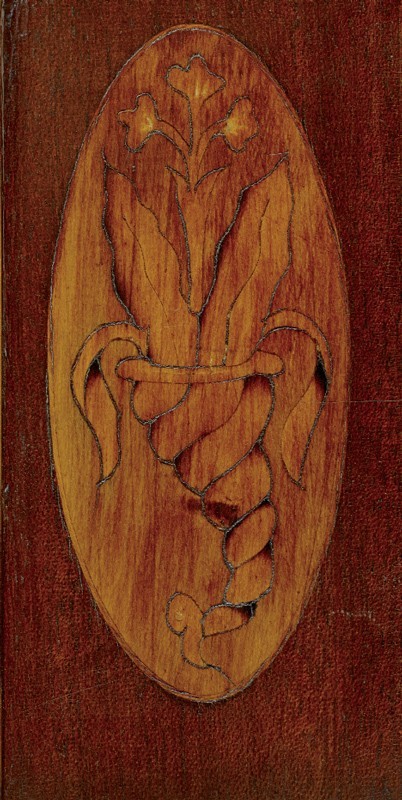

Detail of the oval inlay on the table illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

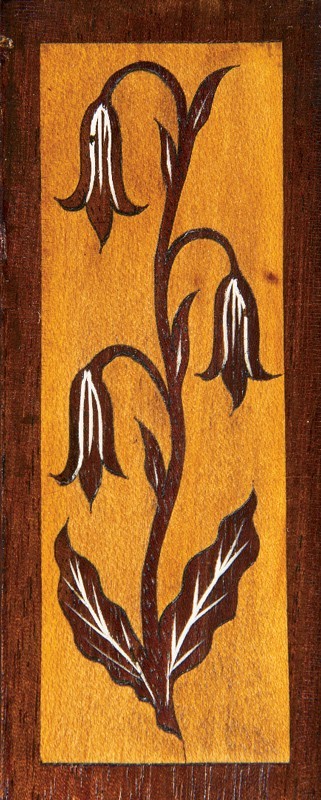

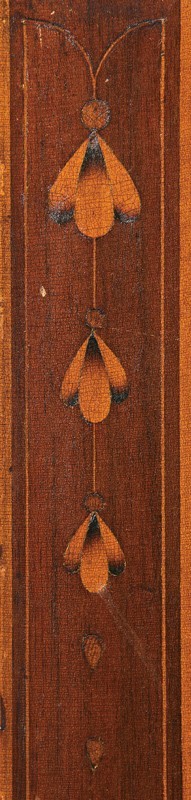

Detail of the bellflower inlay on the table illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Pier table, attributed to Baltimore, Maryland, ca. 1800. Mahogany, satinwood, and mixed-wood inlay with white pine and tulip poplar. H. 34 1/2", W. 39 3/4", D. 20 1/8". (Courtesy, Baltimore Museum of Art, gift of Angelica Yonge Pearre, 1982.143.)

Pier table, attributed to Adam Hains (1768–1846), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1795. Mahogany, satinwood, and mixed-wood and mastic inlay with hard pine (back rail). H. 28 5/8", W. 36 1/8", D. 17 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The applied cuffs are restored.

Detail of the inlay on the table illustrated in fig. 12. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the table illustrated in fig. 12. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Card table, attributed to Adam Hains (1768–1846), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1795. Mahogany, satinwood, and mixed-wood inlay with yellow pine (subtop, inner frame rails, and blocks) and white oak (hinged rail). H. 29 1/2", W. 36 1/2", D. 17 7/8". (Courtesy, Yale University Art Gallery, Mabel Brady Garvan Collection, 1930.2010.)

Detail of the floral inlay on the table illustrated in fig. 15.

Detail of the floral inlay on the table illustrated in fig. 15.

Detail of the griffin inlay on the table illustrated in fig. 15.

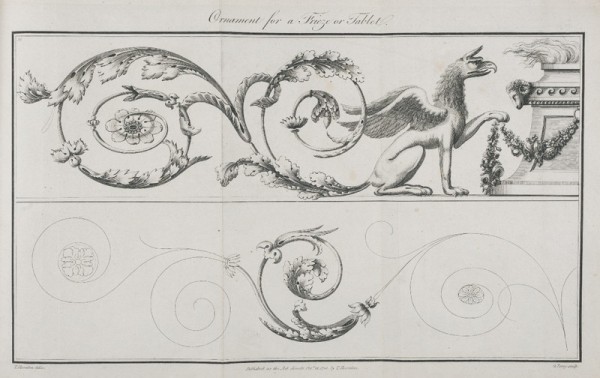

Design for a frieze or tablet illustrated as plate 56 in Thomas Sheraton’s The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing-Book (London: T. Bensley, 1791–1794). (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Printed Book and Periodical Collection; photo, James Schneck.)

Detail of the griffin carving on a long rifle, Christian Oerter (1747–1777), Christian’s Spring, Northampton County, Pennsylvania, 1775. Maple with iron, brass, steel, silver, and horn. (Courtesy, private collection.)

House blessing, Lehigh or Northampton County, Pennsylvania, 1803. Watercolor and ink on laid paper. 13" x 15 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, 1957.1190; photo, James Schneck.)

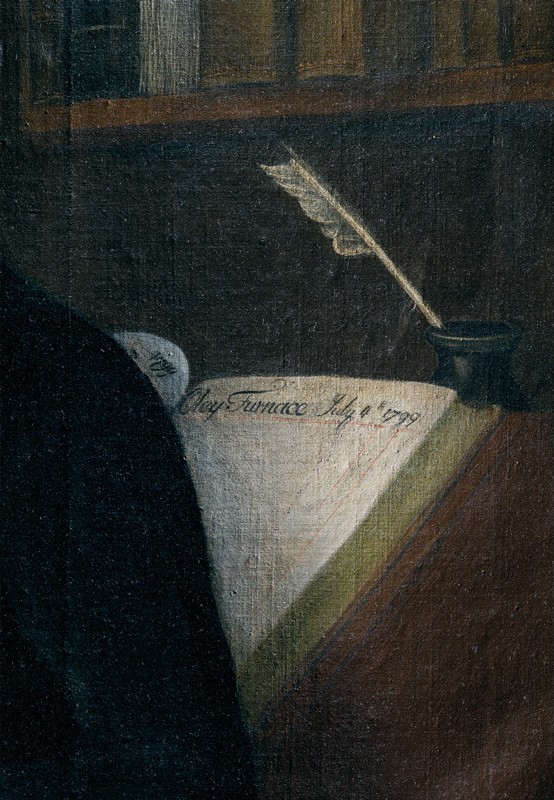

Side chair, attributed to John Aitken (d. 1839), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1797. Mahogany and lightwood inlay. H. 37 1/4", W. 20 5/8", D. 18 3/4". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

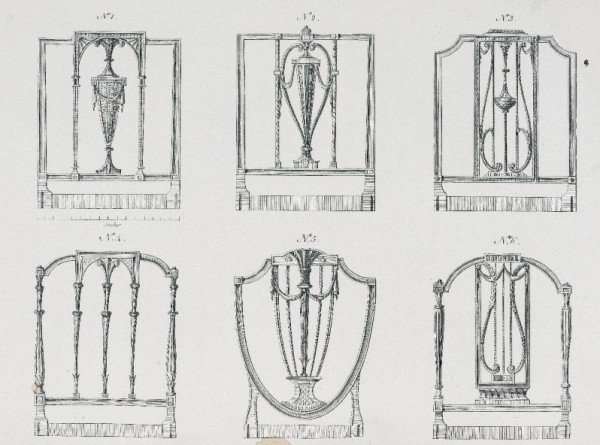

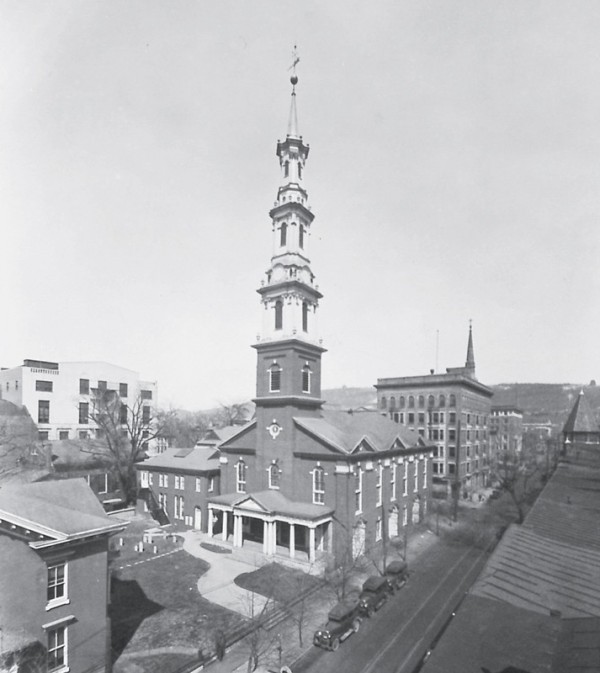

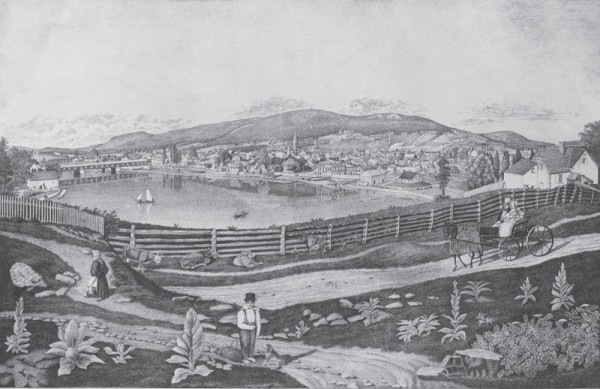

Designs for chair backs illustrated as plate 36 in Thomas Sheraton’s The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing-Book (London: T. Bensley, 1791–1794). (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Printed Book and Periodical Collection; photo, James Schneck.)

Side chair, probably by Adam Hains (1768–1846), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1800. Materials and dimensions unrecorded. (Whereabouts unknown. Photo reproduced from William MacPherson Hornor Jr., Blue Book Philadelphia Furniture [Philadelphia: the author, 1935], pl. 416.)

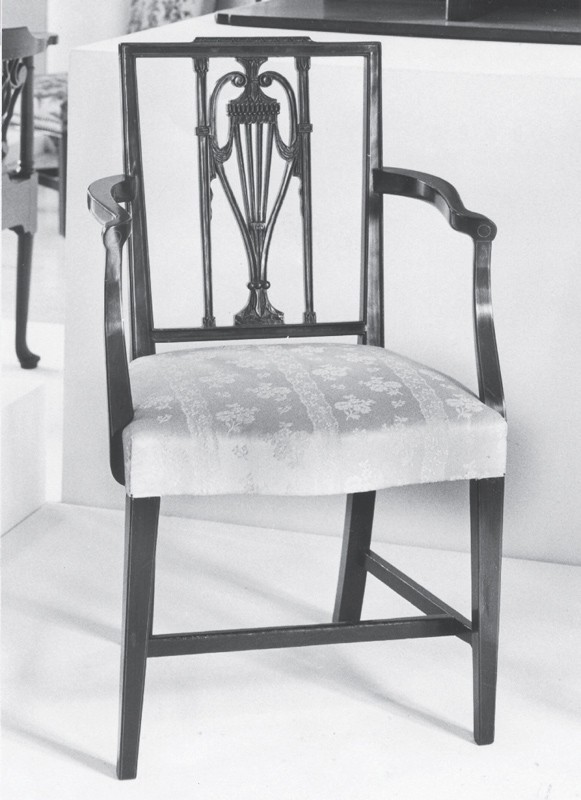

Armchair, possibly by Adam Hains (1768–1846), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1797. Mahogany. H. 36", W. 22", D. 18". (Whereabouts unknown. Photo, Winterthur Library, Decorative Arts Photographic Collection.)

John Eckstein (1736–1817), Justus Heinrich Christian Helmuth, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1795. Oil on canvas. 31" x 28". (Courtesy, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.)

Armchair, possibly by Adam Hains (1768–1846), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1800. Materials and dimensions unrecorded. (Whereabouts unknown. Photo, Muhlenberg College, Special Collections and Archives.)

Armchair, attributed to Adam Hains (1768–1846), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1795. Mahogany with ash. H. 33 3/4", W. 23 1/4", D. 19 1/4". (Courtesy, Historic New England, gift of the children of Arthur and Susan Cabot Lyman, 1966.121.)

Furnishings in the Bow Parlor at The Vale, Waltham, Massachusetts, built 1793. Photograph by A. H. Folsom, 1884. (Courtesy, Historic New England.)

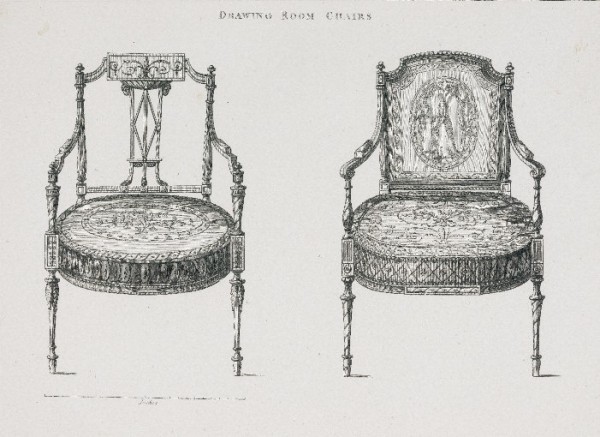

Designs for chairs illustrated as plate 6 in the appendix of Thomas Sheraton’s The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing-Book (London: T. Bensley, 1791–1794). (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Printed Book and Periodical Collection; photo, James Schneck.)

Armchair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1800. Ash with paint and gilding. H. 36 1/2", W. 20 1/2", D. 215/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, 1991.66; photo, James Schneck.)

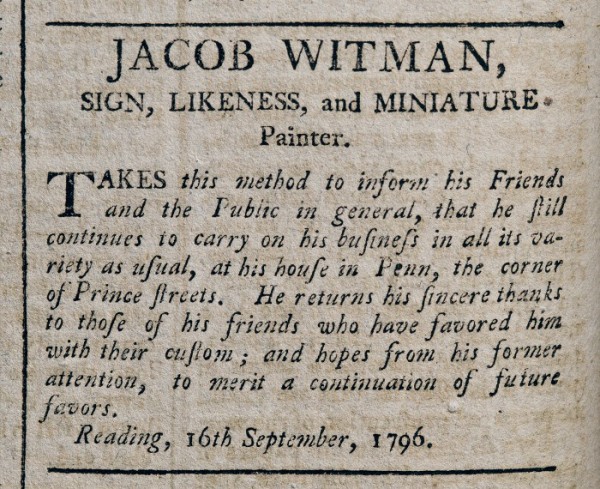

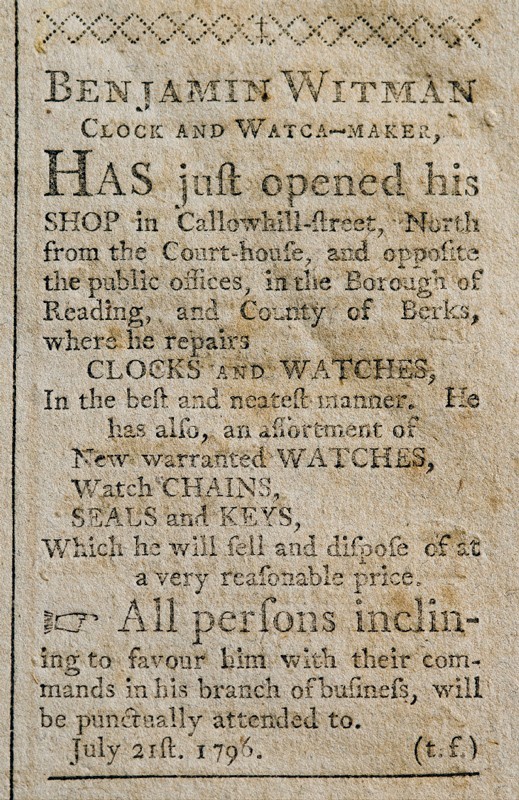

Armchair, attributed to Adam Hains (1768–1846) with under-upholstery attributed to George Bertault, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1795. Mahogany with ash. H. 33 3/4", W. 23 1/4", D. 19 1/4". (Courtesy, Historic New England, gift of the children of Arthur and Susan Cabot Lyman, 1966.124.)

Federal Hall: The Seat of Congress, printed by Amos Doolittle after a drawing by Pierre LaCour, New Haven, Connecticut, 1790. Watercolor and ink on wove paper. 18 1/4" x 14 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, 1957.816.)

Joseph Wright, Frederick Augustus Conrad Muhlenberg, New York, 1790. Oil on canvas with applied wood strip. 47" x 37" (including frame). (Courtesy, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.) A strip of wood 1 3/8" wide was added to the canvas at the left edge and painted by Wright.

Sofa, labeled by Adam Hains (1768–1846), with under-upholstery attributed to George Bertault, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1800. Mahogany with beech. H. 36", W. 72", D. 30". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, 1978.0159; photo, James Schneck.) The seat’s under-upholstery is a later replacement.

Detail of the carving on the sofa illustrated in fig. 35.

Detail of an arm on the sofa illustrated in fig. 35.

End view of the sofa illustrated in fig. 35. (Photo, James Schneck.) The rear leg seen here is an old replacement matching the two original rear legs.

Card table, attributed to Jacob Wayne (1760–1857), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1796. Mahogany with mixed-wood inlay. H. 29", W. 36", D. unrecorded. (Whereabouts unknown. Image from Parke-Bernet Galleries, New York, The Americana Collection of the Late Mrs. J. Amory Haskell, part 4, November 8–11, 1944, lot 192.)

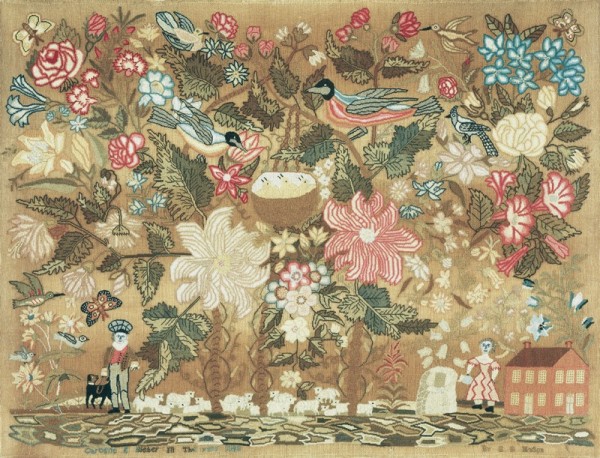

Needlework picture, by Caroline E. Bieber (1827–1885) under the instruction of Elizabeth Baish (Hains) Mason (1797–1875), Kutztown, Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1843. Wool and silk on linen. 22 1/4" x 28 1/2". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Victor L. Johnson, 1999-173-1.)

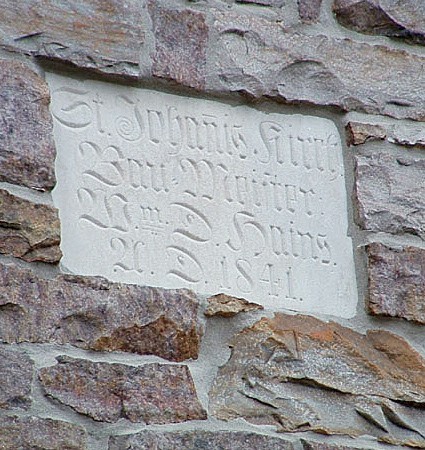

Date stone from St. John’s Church, Pricetown, Berks County, Pennsylvania, built 1841. (Photo, Mark Maxwell.)

Drawing of the Berks County courthouse, Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1820. Ink on wove paper. 14" x 10 1/4". (Courtesy, Berks History Center, Reading, Pa.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Portrait of Daniel Udree, Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1799. Oil on canvas. 72" x 39". (Courtesy, Berks History Center, Reading, Pa.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

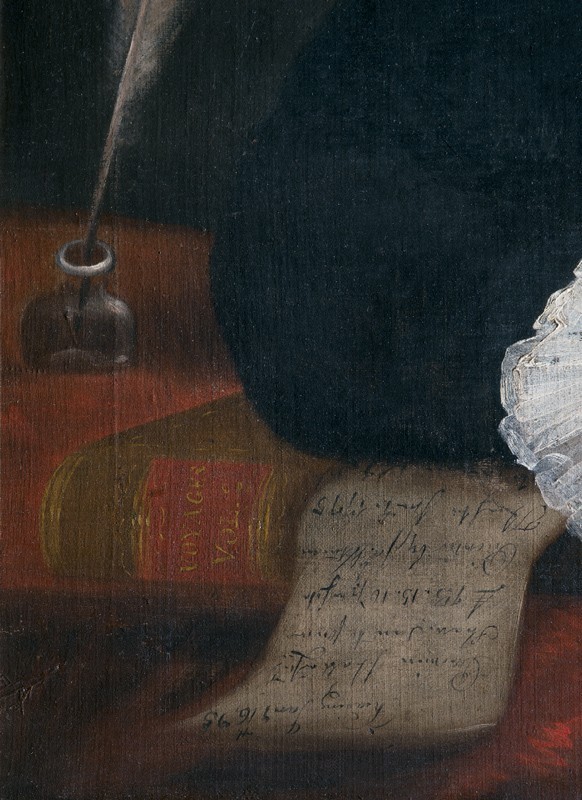

Detail of the portrait illustrated in fig. 43. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Trinity Lutheran Church, Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, built 1791–1794. Photo, ca. 1925. (Courtesy, Berks History Center, Reading, Pa.)

Detail from A View of Reading, drawn by F. A. Holzwart, printed by George Lehman and Peter Duval, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1837. Ink on wove paper. 20" x 28". (Courtesy, Berks History Center, Reading, Pa.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tall clock, case attributed to John Cunnius (1733–1808), movement signed by Daniel Oyster (1766–1845), Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1805. Walnut with white pine. H. 97 3/8", W. 21 5/8", D. 10 5/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, 1959.2807; photo, Laszlo Bodo.)

Portrait miniature of George Heller, Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1840. Watercolor on ivory. 2 1/4" x 2". (Courtesy, Berks History Center, Reading, Pa.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Dorothea Otto, portraits of Portraits of Dr. Bodo and Catharina, Pennsylvania, ca. 1750. Oil on canvas. 30" x 24". (Courtesy, Berks History Center, Reading, Pa.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tall clock, case signed by Daniel Rhein (1778–1868) and Henry Quast (1790–1870 or later), Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1809. Mahogany and mixed-wood inlay with white pine. H. 103", W. 18 1/2", D. 10 1/4". (Courtesy, Berks History Center, Reading, Pa., bequest of John J. Snyder Jr.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the clock illustrated in fig. 51. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tall clock, case attributed to Daniel Rhein (1778–1868), Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1810. Mahogany and mixed-wood inlay with white pine. H. 103", W. 22", D. 10 3/4". (Courtesy, Berks History Center, Reading, Pa., bequest of John J. Snyder Jr.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the clock illustrated in fig. 53. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

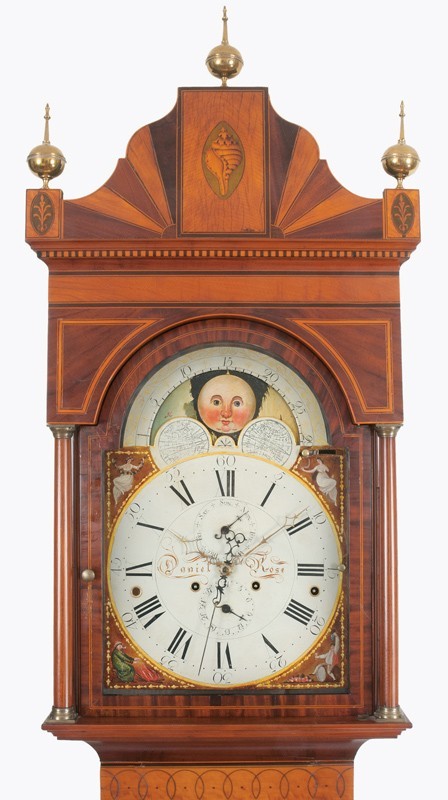

Tall clock, case attributed to Daniel Rhein (1778–1868), movement signed by Daniel Rose (1749–1827), Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1805. Mahogany with satinwood and mixed-wood inlay and pine. H. 112", W. 22", D. 11". (Private collection; photo, Gary R. Sullivan Antiques.)

Detail of the hood on the clock illustrated in fig. 55.

Slant-front desk, attributed to Daniel Rhein (1778–1868), Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1810. Mahogany and light-wood inlay with white pine and tulip poplar. H. 42 1/2", W. 44", D. 21 1/8". (Courtesy, Berks History Center, Reading, Pa., bequest of John J. Snyder Jr.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the desk illustrated in fig. 57. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Portraits of Matthias and Maria Salome Muhlenberg Richards, probably Pennsylvania, ca. 1790. (Photos reproduced from Henrietta Meier Oakley and John Christopher Schwab, Muhlenberg Album [New Haven, Conn.: the authors, 1910].)

Card table, attributed to Daniel Rhein (1778–1868), Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1810. Satinwood, mahogany, and mixed-wood inlay with tulip poplar and white pine. H. 30", W. 36 1/2", D. 17 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Card table, attributed to Daniel Rhein (1778–1868), Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1800. Satinwood, mahogany, and mixed-wood inlay with tulip poplar and white pine. H. 30", W. 36 1/2", D. 17 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Sotheby’s.)

Detail of the inlay on the table illustrated in fig. 62. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the table illustrated in fig. 66. (Photo, Pook & Pook.)

Card table, attributed to Daniel Rhein (1778–1868), Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1810. Satinwood, mahogany, and mixed-wood inlay with tulip poplar and white pine. H. 30", W. 36 1/4", D. 17 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Leigh Keno Antiques.)

Card table, attributed to Daniel Rhein (1778–1868), Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1810. Satinwood, mahogany, and mixed-wood inlay with tulip poplar and white pine. H. 30", W. 36 1/4", D. 17 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Pook & Pook.)

Detail of the underside of the table illustrated in fig. 61. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Top of the table illustrated in fig. 61. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Sideboard, attributed to Daniel Rhein (1778–1868), Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1810. Mahogany, satinwood, and mixed-wood inlay with tulip poplar and white pine. H. 38", W. 78", D. 24 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the sideboard illustrated in fig. 69. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the sideboard illustrated in fig. 69. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Square piano, labeled by John Haberacker (1780–1846), case attributed to Daniel Rhein (1778–1868), Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1810. Mahogany with mahogany and satinwood veneer, ivory, and ebony. H. 33 5/8", W. 64", D. 22 5/8". (Courtesy, Historic RittenhouseTown; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the piano illustrated in fig. 72. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest of drawers with looking glass, labeled by Daniel Rhein (1778–1868), Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1830. Mahogany veneer with tulip poplar, pine, and chestnut. H. 75 3/4", W. 41 1/8", D. 23 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Winterthur Library, Decorative Arts Photographic Collection.)

Tall clock, case attributed to Daniel Rhein (1778–1868), movement signed by Benjamin Witman (1774–1857), Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1805. Mahogany and mixed-wood inlay with white pine. H. 103", W. 22", D. 10 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Pook & Pook.)

Dial of the clock illustrated in fig. 75, painted decoration probably by William Witman (1770–1826), Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1805. (Photo, Philip H. Bradley Co.)

Dial of the clock illustrated in fig. 47, painted decoration probably by William Witman (1770–1826), Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1805. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.)

Advertisement by Jacob Witman in the Impartial Reading Herald, Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, September 16, 1796. (Courtesy, Berks History Center, Reading, Pa.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Advertisement by Benjamin Witman in the Impartial Reading Herald, Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, September 16, 1796. (Courtesy, Berks History Center, Reading, Pa.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

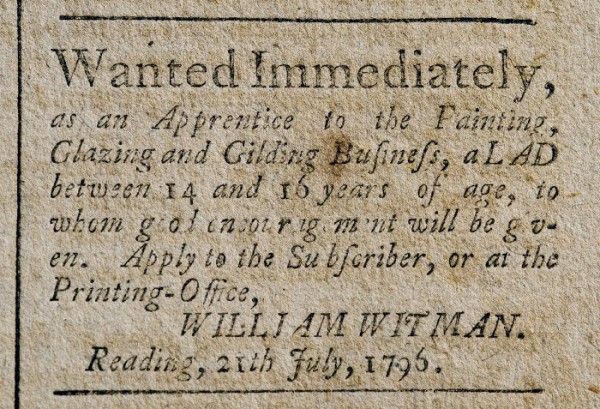

Advertisement by William Witman in the Impartial Reading Herald, Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, July 21, 1796. (Courtesy, Berks History Center, Reading, Pa.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a tall clock, movement by George Faber (1778–1834), Reading, Berks County or Sumneytown, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania; painted decoration probably by William Witman (1770–1826), Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1809. Cherry, walnut, and mixed-wood inlay with pine. H. 102 5/8", W. 23 5/8", D. 12 1/2". (Whereabouts unknown. Photo, Winterthur Library, Decorative Arts Photographic Collection.)

Detail of a drawing installed in the sidelight of the clock illustrated in fig. 81, probably by William Witman (1770–1826), Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1809. Watercolor and ink on paper. Dimensions unrecorded. (Photo, Winterthur Library, Decorative Arts Photographic Collection.)

Portrait of Joseph Hiester, signed by Jacob Witman (1769–1798), Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1795. Oil on canvas. 36" x 30 1/2". (Courtesy, Berks History Center, Reading, Pa.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the portrait illustrated in fig. 83. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Buttons owned by Adam Witman and Joseph Hiester, ca. 1780. Silver. Diam. 1". (Courtesy, Berks History Center, Reading, Pa.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

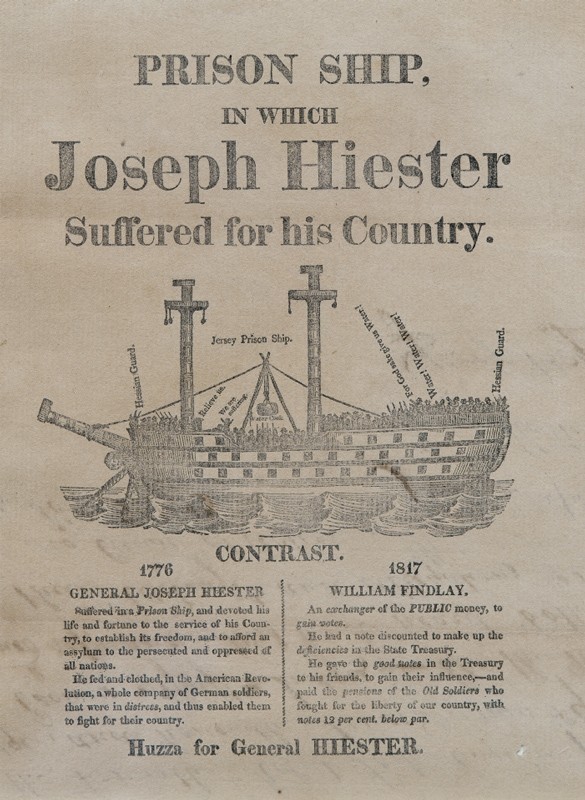

Broadside for the gubernatorial campaign of Joseph Hiester, Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1820. Ink on wove paper. 8" x 6". (Courtesy, Berks History Center, Reading, Pa.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Portrait of Elizabeth (Witman) Hiester, attributed to Jacob Witman (1769–1798), Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1795. Oil on canvas. 36" x 30". (Courtesy, Berks History Center, Reading, Pa.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Portrait of Rebecca or Mary Elizabeth Hiester, attributed to Jacob Witman (1769–1798), Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1795. Oil on canvas. 26 1/2" x 20 1/2". (Courtesy, Berks History Center, Reading, Pa.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Portrait of Rebecca or Mary Elizabeth Hiester, attributed to Jacob Witman (1769–1798), Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1795. Oil on canvas. 26 1/2" x 20 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, 2012.6; photo, James Schneck.)

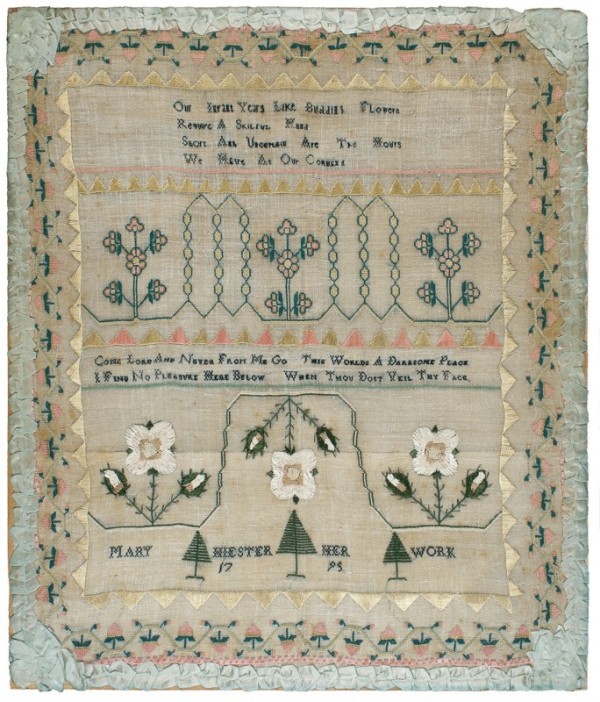

Sampler, by Mary Elizabeth Hiester (1784–1806), Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1795. Silk on linen. 19 1/2" x 16 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; photo, James Schneck.)

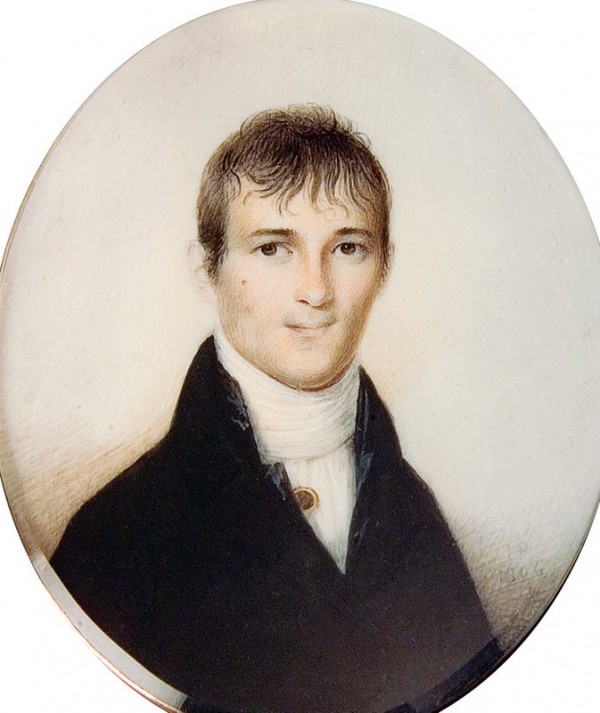

Portrait miniature of Henry Augustus Muhlenberg, by James Peale (1749–1831), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1804. Watercolor on ivory. Dimensions unrecorded. (Private collection; photo, Glenn Holcombe.)

Portrait of Peter Nagle, attributed to Jacob Witman (1769–1798), Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1795. Oil on canvas. 29 3/4" x 24 3/4". (Courtesy, Berks History Center, Reading, Pa.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Portrait of Daniel Rose, signed by Jacob Witman (1769–1798), Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1795. Oil on canvas. 64" x 40 1/2". (Courtesy, Berks History Center, Reading, Pa.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the landscape in the portrait illustrated in fig. 93. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the table in the portrait illustrated in fig. 93. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the signature in the portrait illustrated in fig. 93. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Portrait of a young woman (possibly Mary or Margaret Rose), attributed to Jacob Witman (1769–1798), Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1795. Oil on canvas. 35 3/4" x 30 1/4". (Courtesy, Berks History Center, Reading, Pa.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

One of the most talented cabinetmakers in Philadelphia at the turn of the nineteenth century was Adam Hains (1768–1846), a brilliant craftsman whose work is largely unknown within the canon of American furniture (fig. 1). Most often, he is confused with cabinetmaker Ephraim Haines (1775–1837), who apprenticed with Daniel Trotter in 1791 and went into partnership with him in 1798, but the two men were unrelated. For years, the only known example of Adam Hains’s work was a branded drop-leaf table (figs. 2, 3), which was sold at the Reifsnyder sale in 1929 and acquired by Henry Francis du Pont. In 1980 a study of upholstered seating furniture labeled by Hains was published in which he was linked to émigré French upholsterer George Bertault. New discoveries about Hains’s life and cabinetmaking have recently emerged, including an extraordinary group of inlaid furniture and intriguing ties to Reading, Pennsylvania, where a remarkably sophisticated group of inlaid furniture was made for members of the local German-speaking elite. The following article will present an overview of Adam Hains’s life and work, focusing on labeled or firmly documented examples, followed by a detailed look at the Reading furniture. The final section presents new information about Reading clockmaker Benjamin Witman and painters Jacob and William Witman.[1]

Adam Hains

Born on February 9, 1768, to Johann Heinrich and Anna Catharina (Lohrmann) Hähns of Philadelphia, Heinrich Adam Hähns/Hains was baptized on February 28 at St. Michael’s and Zion Lutheran Church. Adam Hains had at least five siblings: Anna Catharina (b. 1765), Maria Margaretha (b. 1770), Henry (b. 1772), John (b. 1775), and Jacob. His father was the proprietor of the Spread Eagle Tavern, located on the east side of Third Street in Philadelphia. Heinrich Hähns died in 1783, leaving a sizable estate valued at £753.1.8—including a silver watch, mahogany dining table and card table, two walnut tea tables, and a walnut desk. His widow and fifteen-year-old son Adam were appointed as executors, while his “esteemed Friend” John Steinmetz was named guardian of the minor children. A merchant, John Steinmetz (1740–1803) was the business partner and son-in-law of Heinrich Keppele—one of the wealthiest German Lutherans in colonial Philadelphia and the founding president of the German Society of Pennsylvania (est. 1764). Evidently the Hains family knew the Keppeles fairly well, as Heinrich Keppele’s daughter Anna Catharine was the baptismal sponsor after whom Anna Catharina Hains was named in 1765. On September 8, 1791, Adam Hains married Margaret Baisch/Baish (1773–1855), daughter of Philadelphia shoemaker Martin Baisch and his wife, Maria Magdalena. They had at least six children, including Maria (1793–1869), Henry Martin (1795–1851), Eliza Baish (1797–1875), Hannah Baish (1799–1836), Sarah Baish (1801–1881), and William D. (1804–1867).[2]

The earliest known example of Adam Hains’s cabinetmaking is a small, drop-leaf table branded “A. HAINS / PHILA fecit” on the underside of the drawer (figs. 2, 3). The table has a gadrooned skirt, serpentine-shape leaves, arched saltier stretcher, and fluted Marlborough legs terminating in slightly tapered, blocked feet. Because the legs are fixed to the stretcher, the leaves are supported by fly rails that swing out on wooden, six-finger knuckle hinges at either side. The table’s single drawer is cock-beaded and constructed with small, finely shaped dovetails; its bottom is chamfered at the edges, slid into a groove, and secured with small glue blocks around the perimeter (figs. 4, 5). Tables of this form became popular in the mid-1700s and were illustrated in plate 53 of Thomas Chippendale’s Director (1762), where they were described as “Breakfast Tables.” The Philadelphia furniture price book of 1772 refers to them as “Pembroke or Breakfast Tables” and notes a base price of £3 for a mahogany one with a drawer. The table’s small scale made it lightweight and easily portable, despite its sturdy construction. George Hepplewhite referred to tables of this form as “Pembroke Tables” in The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Guide (1787) and noted they were “the most useful of this species of furniture,” while Thomas Sheraton described an oval version in his Drawing-Book (1791–1794) as a table “for a gentleman or lady to breakfast on.” Pennsylvania German consumers were quick to acquire tables of this form, prompting cabinetmakers such as John Bachman of Strasburg, Lancaster County, to make examples in 1784 and 1786, which he noted in his account book as “ein Düsch brägfast Döbel” (a table, breakfast table) and “ein zümorganess Disch” (a breakfast table). Although the date of this table’s manufacture is unknown, it was likely not much before 1788, when Adam Hains was only twenty years old. A mid-to-late 1780s date is also suggested by the cast brass handle on the drawer, which is nearly identical to one illustrated in a catalogue of English brass hardware, dating between 1783 and 1789, that was owned by merchant Samuel Rowland Fisher of Philadelphia.[3]

The first identification of Adam Hains as a cabinetmaker appears on July 21, 1792, in Claypoole’s Daily Advertiser, where it was announced that someone had tried “to set fire to the house of Mr. Hains, cabinet-maker, in Third near Vine Street.” Hains is not listed in the 1791 Philadelphia directory, but his mother, Catharine, is listed as a shopkeeper at 135 North Third Street. In 1793 both “Haines, Adam, cabinet maker” and “Haines, Catharine, widow” are listed at the same address. Adam is listed there again in 1794 but his mother at 16 South Fourth Street; both are listed at 135 North Third Street again in 1796 and 1797. Hains appears to have been in partnership with Philadelphia merchant Joseph Rittenhouse, as the two men advertised jointly in May 1794 for two runaway “Dutch servant LADS,” one named William Peter Carroll, aged twenty, who “speaks pretty good English, writes a good hand, [and is] well educated in the German language.” The other runaway was Francis Carolus Grum, aged twenty-four, and “a Joiner by trade.” Three months later, Hains offered a reward of ten dollars for the return of an “apprentice lad named Isaac Nixon...about 18 years of age.” Apparently Nixon did not like working for Hains, as the ad noted it was the third time he had run away (after the second occasion, in January 1794, Hains offered only $1 for Nixon’s return). On June 7, 1797, Adam Hains announced the relocation of his “Cabinet Manufactory” to number 261 on the south side of Market Street (where his neighbors included attorney Benjamin Chew Jr. and merchant Simon Gratz). In 1798 he is not listed in the city directory but “Hains, widow” as well as “Haines, John, cabinet maker” are both listed at 135 North Third Street. In 1799 and 1800 Adam Hains is listed at 261 South Market Street while his mother and brother “Hains, John cabinet maker” are at 135 North Third Street. This is the only known indication that John Hains, Adam’s younger brother, also worked as a cabinetmaker. Nothing further is yet known about John or his furniture.[4]

The turn of the nineteenth century was a tumultuous time for Philadelphia artisans and laborers. Many master craftsmen such as Adam Hains struggled to make ends meet in the economic depression that followed the American Revolution, while journeymen resented the competition and lower wages that resulted from the rising use of apprentices and unskilled laborers. This volatile situation periodically erupted, such as in 1791, when Philadelphia’s carpenters organized one of the first labor strikes in United States history. Three years later, the city’s shoemakers formed the Federal Society of Journeymen Cordwainers in an effort to protect their income, followed by several more public “turn-outs” or strikes during the late 1790s. In the midst of these difficult economic times, Adam Hains decided to give up cabinetmaking and in November 1800 advertised a list of “Elegant Furniture for Sale...Being the remainder of a Stock on hand of the subscriber, who is about declining the business, and will sell for cash at a reduced price, or will exchange for Groceries.” The extraordinary listing that followed provides a glimpse of the impressive range of sophisticated furniture made by Hains’s workshop:

A LADY'S CABINET AND DRESSING TABLE

the first of that fashion in the United States, 200 dollars

2 elegant Secretaries and Book Cases

Secretaries, Desks portable do.

Wardrobes

Sideboards of the newest fashions and different patterns

Chairs do. do.

Sophas to match do. do.

Easy Chairs

Dining, Card, Breakfast and Peer Tables of all patterns

Circular and Square Bureaux

Dressing Glasses

Circular and Square Wash Stands

Two Eight Day Clocks, and Cases, &c. &c.

Hains also advertised one hundred acres of woodland for sale near the Duck Creek Cross Roads in New Castle County, Delaware. What did the furniture listed by Hains in this advertisement look like? Although no large case pieces have yet been identified, a number of labeled or firmly attributable tables and seating furniture have come to light that help provide some insight on the wide range of items produced by Hains’s workshop.[5]

Inlaid Furniture

While Adam Hains lived and worked as a cabinetmaker at 135 North Third Street from at least 1793 to 1797 and again in 1803, he used two different labels with identical typesetting but different borders, proclaiming “ALL KIND OF / CABINET AND CHAIRWORK / DONE BY / ADAM HAINS, / NO. 135, NORTH THIRD-STREET, / PHILADELPHIA” (fig. 6). Although speculative, it is possible that the labels may have been obtained from Philadelphia bookseller Ernst Ludwig Baisch—the uncle of Margaret Baisch, Adam Hains’s wife. No labels have yet been discovered bearing his 261 South Market Street address. A Hains label appears on one of a pair of mahogany card tables (fig. 7), each of which also bears the brand “T ELWYN” for the original owner, Thomas Elwyn (1775–1816). Born in England, Elwyn moved to Philadelphia to study law and in 1797 married Elizabeth Langdon of Portsmouth, New Hampshire. The couple bought a house on Samson Street in Philadelphia and acquired other locally made furniture, including a lady’s cabinet and writing table made in 1809 by John Sailor. The Elwyns’ card tables feature square tops with ovolo corners, made by applying a mahogany veneer over a five-part, horizontally laminated substrate; tables of this form had a base price of £2.5 each in the 1795 Philadelphia price book. On both card tables, the hinged rail is made of oak with a hefty 1!÷$-inch thickness. At the center of each table is a rectangular plaque inlaid with a bouquet of flowers and a bowknot (figs. 8, 9). Traces of red and white infill, possibly mastic, were used to add colorful highlights to the inlay, including the oval plaques dyed or stained green and inlaid with cornucopias of flowers. The square, tapered legs are inlaid with distinctive husks or bellflowers that have a long, narrow shape, central petals that are heavily darkened by sand-shading, and a pronounced outward flare of the petal tips (fig. 10). At the top of each leg inlay is a four-petal flower, beneath a pointed arch formed by the string inlay. Similar inlay appears on some Baltimore furniture (fig. 11), but its presence on the labeled Hains card table as well as on a square piano made in 1794 by Charles Taws of Philadelphia firmly documents this motif to Philadelphia.[6]

The labeled Adam Hains card table enables the firm attribution of a pier table with a central plaque inlaid with a closely related floral design (figs. 12, 13). In place of the oval cornucopias inset above the legs, the pier table has narrow, rectangular panels inlaid with a stylized lily-of-the-valley motif (fig. 14). Like the card tables, the pier table has a five-part laminate substrate in the ovolo corners. The applied cuffs on the legs appear to be replaced, but scoring marks and a lack of finish underneath—visible in areas of loss—indicates that the table did originally have applied cuffs. The numeral “2” is inscribed on the inside of the rear rail in chalk, suggesting that the pier table may have been one of a pair. It has a history of ownership by John Nixon (1733–1808), a Philadelphia merchant, wharf owner, and president of the Bank of North America from 1792 to 1808. An ardent patriot, Nixon is best known as the first public reader of the Declaration of Independence, which he did on July 8, 1776, from the steps of the Pennsylvania State House (later known as Independence Hall). Although Nixon was an Anglican and member of St. Peter’s Church, as a businessman and civic leader he had numerous dealings with the German-speaking community in Philadelphia. In 1796 Nixon and his daughter Elizabeth served as sponsors for the baptism of Elisabeth Temer, daughter of Henry Michael and Maria Jacobina Temer, at St. Michael’s and Zion Lutheran Church. Three years later, Elizabeth Nixon married Justus Erich Bollmann, a German physician.[7]

Survival, Revival, or Fraud?

The distinctive four-petal flowers and bellflowers used by Adam Hains are virtually identical to the inlay on a card table in the Garvan collection at Yale (figs. 15-18). The table has a solid mahogany upper leaf and a lower leaf made of mahogany veneer over pine; both leaves are countersunk to receive an inset cloth gaming surface. At the center of the front rail, the table has an inlaid plaque with image of a griffin based on plate 56 in Sheraton’s Drawing-Book (figs. 18, 19). Sold in 1929 at the Reifsnyder sale and acquired by Mabel Brady Garvan, the table was long thought to be from Baltimore and was included as such in the 1929 Girl Scout Loan exhibition and a 1947 exhibition of Baltimore furniture. By the 1970s, however, the table was denounced as a “skillful fake,” with new veneer and inlay on a frame that was “probably English.” The griffin was deemed spurious, as the motif was otherwise “unknown in American furniture inlay,” and the bellflowers were doubted for being “exaggerated in size.” Evidence of the table’s fraudulent construction that was cited included the use of modern dowels to attach the legs to the frame, marks on the underside of the top suggesting that it was not original to the present frame, and extensions to the legs that were hidden behind the inlaid cuffs. These conclusions were repeated in a 1992 catalogue, in which the card table was described as a “sophisticated fake made from fragments of at least two tables,” to which the inlay was later added.[8]

In light of the other inlaid tables made by Adam Hains, however, it is worth reexamining the table illustrated in figure 15. Its use of mahogany and satinwood veneers with oak and pine secondary woods is entirely consistent with Philadelphia furniture of this period. The dimensions of the table are very close to those of the pair of card tables made by Adam Hains, including the use of thick, 1 1/4-inch white oak for the hinged rail. The inlay on the legs as well as the oval plaques are virtually identical in size, shape, and technique of manufacture—including the use of red or white infill to add highlights to the flowers—to those on the Hains card tables. The griffin plaque inlaid at the center has a number of subtle features that relate it to the inlay on the legs. For example, the four-petal flower above the bellflowers has tiny, V-shape marks near the outer edge of each petal. Identical marks also appear on the outer lobes of the leafy terminus to the griffin’s tail. Although the griffin motif is rare and perhaps unique in American furniture inlay, that alone is not sufficient reason to doubt it. Moreover, the griffin or Vogelgreif was not an uncommon motif in Pennsylvania German art, where it adorns such objects as the carved buttstock of a long rifle and numerous fraktur, including a house blessing dated 1803 (figs. 20, 21).[9]

Careful reexamination of the Yale table indicates that, rather than being a sophisticated fake, it underwent a serious accident that snapped off the front legs at the top, damaging the veneer and inlay in the process. The rear rail was also likely broken in this accident, as it has a scarf joint repair. To restore the table, all four legs were removed and the inlaid oval plaques at the top of the rear legs were carefully sawn off and moved to the front. Plain mahogany veneer was then used to patch the rear legs. All four legs had been cut down at some point; to repair this, each leg was extended by three inches and a wide cuff used to conceal the joint. Comparison with the pair of labeled Hains card tables indicates how the legs were likely finished originally, with line inlay terminating in a slight arc above a narrow, dark-wood inlaid cuff with light-wood stringing border. Several pieces of the satinwood borders flanking the front legs were either replaced or reattached following the break. After the repairs were made, the legs were reattached to the frame with wooden dowels. The front legs were additionally secured by the attachment of wooden brackets with screws to the inside and the addition of a wooden spline to the front rail where the damage weakened the joint of the leg. Screw holes on the underside of the lower leaf’s subtop were most likely the result of someone at a later date fixing the two leaves together so the top stayed shut for ease of handling while the table was being repaired. Even with this extensive restoration, the card table’s elaborate serpentine shape and rare griffin inlay make it one of the most sophisticated pieces known that can be attributed to Adam Hains and merit its recognition as an extraordinary survival of Philadelphia federal furniture.

Inlaid and Carved Chairs

Among the most famous seating furniture made in federal Philadelphia is the set of two dozen chairs made for George Washington in 1797 by Scottish émigré cabinetmaker John Aitken (fig. 22). The Washington chairs are distinguished by their pierced, vasiform back splats topped with feathers based on plate 36 in Sheraton’s Drawing-Book (fig. 23). A similar, although not identical, splat appears on a chair that also has inlaid four-petal flowers and bellflowers on the front legs, which appear to be identical to the inlay on the Hains card tables (fig. 24). Although the original owner and present whereabouts of this inlaid chair are unknown, in 1935 it was owned by Philadelphia judge Thomas D. Finletter (1862–1947) and his wife. Given the close relationship of the inlay, Hains is a strong candidate to have made the latter chair. He may also have been the maker of a set of ten mahogany side chairs and two armchairs that were originally owned by Justus Heinrich Christian Helmuth (1745–1825), pastor of St. Michael’s and Zion Lutheran Church from 1779 to 1820 (figs. 25, 26). A native of Germany, Helmuth immigrated in 1769 and in 1784 succeeded Henry Melchior Muhlenberg as senior pastor in Philadelphia. In 1770 he married Barbara Keppele, whose father, Henry, was a wealthy merchant and one of the most powerful laymen in the congregation. Helmuth, who was known as an excellent preacher, zealously opposed the use of English in Lutheran church services and optimistically predicted in 1784 that soon “Philadelphia will resemble a German city much more than an English one.” Given Helmuth’s strong pro-German views, it seems much more likely that he would have patronized his own parishioner, Adam Hains, rather than a non-German Lutheran competitor such as John Aitken. A related armchair with a slightly different back splat was owned by Peter Muhlenberg (1746–1807), son of Henry Melchior Muhlenberg (fig. 27). Although the present whereabouts of the Muhlenberg chair are unknown, it was exhibited in 1942 at Muhlenberg College. Unfortunately, the only known photograph of the chair from that installation is quite dark, but a hint of line inlay can be detected at the ankle of the front legs.[10]

Upholstered Furniture in the French Taste

During the 1790s Hains made upholstered furniture that was strongly influenced by Sheraton’s Drawing-Book (London, 1791–1794) and the vogue for French fashions, spurred by the arrival in Philadelphia of many French immigrants seeking refuge from the French and Haitian revolutions. Hains made at least five closely related sets of French-style armchairs during this period. The basis of these attributions derives in part from a set of eight mahogany armchairs and two sofas (or settees) that were made for The Vale, the country seat in Waltham, Massachusetts, of Bostonian Theodore Lyman, that was designed by Samuel McIntire and built in 1793. Several of the chairs bear Hains’s label from 135 North Third Street (fig. 28). Although it is not documented that these chairs were among The Vale’s original furnishings, they do appear in photographs of its Bow Parlor taken in 1884, along with a related sofa (fig. 29). A set of twelve armchairs and two sofas purchased by Andrew Craigie for the Longfellow-Craigie House in Cambridge, Massachusetts, can also be attributed to Hains based on their similarity to the labeled examples. Seven of the Craigie armchairs survive, together with a bill dated July 9, 1793, from Philadelphia merchants John and Nalbro Frazier to Craigie that identifies George Bertault as the source. Bertault worked in Philadelphia during the 1790s and evidently acquired or commissioned the chairs from Hains. It was common for upholsterers to procure furniture from cabinetmakers as well as the textiles and other trimmings necessary to complement the room interior. In 1771 Philadelphia upholsterer Plunket Fleeson billed John Cadwalader £5.15 for “a Large Sopha stuff’d & finish’d in canvis with the matres also & a case made for do.” Other chairs attributed to Hains and Bertault have histories of ownership by Christopher Gore of Boston, who became governor of Massachusetts in 1809; Alexander Hamilton; and George Washington, who in 1793 purchased a set of “6 Chrs & 2 stools” from Bertault for the green drawing room of the President’s House in Philadelphia. The latter were made to enlarge a set of twelve French-made armchairs, which were among the furniture Washington purchased in 1789 from the French ambassador, Comte de Moustier, when he was recalled to France.[11]

The Hains-Bertault armchairs are of an open-arm design that closely resembles one of the “Drawing Room” chairs depicted in Sheraton’s Drawing-Book (fig. 30). According to Sheraton, that chair model was “intended to be finished in burnished gold, and the seat and back covered with printed silk.” Of a similar armchair illustrated in plate 32, he wrote, “these chairs are finished in white and gold, or the ornaments may be japanned; but the French finish them in mahogany, with gilt mouldings.” One set of at least eight armchairs is known that were originally painted white with gilt highlights; their raised decoration was made of applied composition ornament, however, rather than relief-carved (fig. 31). None of the known chairs associated with Hains appears to have had gilded or painted ornament. Made of mahogany with ash frames, the Hains chairs have arched crest rails with delicate, bell-shape carved finials. The arms terminate in scrolled volutes, which rest on curved, stop-fluted supports. The round, tapered legs are stop-fluted and have carved floral medallions at the top; the feet terminate in a molded disk above a plain conical shaft.[12]

The Hains chairs are also distinguished by their under-upholstery, which survives on most known examples and is a testament to its sturdy, durable construction (fig. 32). These substantial foundations resulted in a boxed edge, which was fashionable on French furniture and would have been well known to Bertault, who described himself as an “Upholsterer from Paris” in the April 12, 1793, edition of the General Advertiser. The finish upholstery was often silk damask. Andrew Craigie requested blue damask for the upholstery on his twelve armchairs, two sofas, and four pairs of matching window curtains, but Bertault had trouble procuring a suitable fabric in that color, and the final invoice reveals that “green & white Damask” was selected. The invoice also notes that “fancy Chintz” was used to make slipcovers for the chairs and sofas. The blue damask that Craigie requested may have been inspired by the furnishings of Federal Hall in New York, location of the first U.S. Congress from December 1788 through August 1790 (fig. 33). Among the grandest furnishings in Federal Hall were the elaborate chairs made for the Speaker of the House and President of the Senate. In July 1790 Speaker Frederick Augustus Muhlenberg was painted in one of the chairs (fig. 34). Although Craigie may never have seen those chairs in person, he likely read the description published in the Massachusetts Magazine of June 1789. The article noted that in the House chamber “the speaker’s chair is opposite the great door, and raised by several steps...the curtains and chairs in this room are of light blue damask,” while the Senate chamber had “crimson damask” furnishings. The renovation of Federal Hall was overseen by French military engineer Pierre Charles L’Enfant, who presumably also selected the furnishings. When Congress relocated to Philadelphia in late 1790, the furnishings stayed in New York. Muhlenberg’s portrait, however, was taken to his town house on North Second Street, where it helped introduce Philadelphians—particularly German Lutherans such as Adam Hains—to the French style of upholstered seating furniture.[13]

In addition to the two sofas made en suite with twelve armchairs for Andrew Craigie, a sofa of a different form that bears a Hains label from 135 North Third Street is known and documents what may be the stylistically latest known example of his work (fig. 35). Although this sofa was also inspired by French models, its ornament differs from the other known Hains sofas. The crest rail has a rectangular plaque at the center flanked by carved, radiating quarter-fans, while the molded arms are supported by reeded, baluster-shaped uprights and terminate in vertical reeding (figs. 36, 37). The seat frame has a central rectangular pendant drop and four turned and reeded, tapering legs terminating in bulbous feet at the front, with four non-reeded but otherwise identical legs in the back. The severe cant of the rear legs caused several of them to crack and break over the years where they attach to the frame (fig. 38). Although French sofas of this general form were made by the 1770s, few if any American-made examples can be documented before 1810. Given that Hains can be identified as residing at 135 North Third Street only from 1793 to 1797 and again in 1803, it appears that the sofa is one of the first American-made examples of this form. The sofa retains its original under-upholstery, with the exception of the seat, revealing that it was upholstered with the boxed edge associated in Philadelphia with Bertault. Fragments of an early, possibly original, finish upholstery were recently found in the process of removing the sofa’s later covering and will be undergoing further analysis.[14]

Who Trained Adam Hains?

At present, it is not known with whom Hains served his apprenticeship, although, based on the construction of his branded drop-leaf table and its lack of overtly Germanic woodworking techniques such as wedged dovetails or pegged-up drawer bottoms (see figs. 2–5), some have speculated that he trained under an English cabinetmaker. As recent scholarship on furniture made by German cabinetmakers in Philadelphia has demonstrated, however, such assumptions may be unfounded. Construction details such as fine, non-wedged dovetails and chamfered drawer bottoms are likely more indicative of urban workmanship than of ethnicity. Furniture made by Pennsylvania German woodworkers in other urban areas such as Lancaster also features non-wedged dovetails and chamfered drawer bottoms that are slid into grooves. High-end German cabinetmakers such as the Roentgens also used refined construction techniques including finely cut, non-wedged dovetails and chamfered drawer bottoms slid into a rabbeted groove, so it is probably unfair to make assumptions about Hains’s training based solely on his construction of a single drawer.[15]

Although no documentation has yet been found to identify the cabinetmaker who trained Adam Hains, several craftsmen can tentatively be put forth. A strong possibility is Leonard Kessler (1737–1803), who like Adam Hains was a German Lutheran and a member of St. Michael’s and Zion Lutheran Church. Although the only documented example of Kessler’s work known to date is a set of mahogany chairs he made in 1763 for Lutheran patriarch Henry Melchior Muhlenberg, he is known to have made major case pieces, including a mahogany desk-and-bookcase for Friedrich Schenckel in 1773. One of Kessler’s daughters, Rachel, married French émigré Antoine Charbonnet DuPlaine (1751–1800) in 1788. DuPlaine served as the French vice counsel in Boston before moving to Philadelphia. A schoolmaster, he took education seriously and in his will of 1796 instructed his wife that their children (both boys and girls) should learn French, German, Spanish, and English as well as arithmetic and bookkeeping. Given Hains’s French-style furniture and collaboration with Bertault, perhaps DuPlaine—via Leonard Kessler—was the inspiration.[16]

Another possibility is Jacob Wayne (1760–1857), the third generation in an extended family of Philadelphia cabinetmakers. A demilune card table with floral inlay on the legs similar to that on Adam Hains’s tables is attributed to Jacob Wayne based on an extant bill of sale dated June 25, 1796, that lists, along with other furniture, two mahogany circular card tables (fig. 39). Little else is known of Jacob Wayne’s work. A third possibility is John Aitken, the Scottish émigré cabinetmaker who made vase-back chairs in a style similar to Hains’s (see fig. 22). Aitken was the proprietor of a “cabinet and chair manufactory” located at the southeast corner of Chestnut and Second Streets from circa 1775 to 1800. In 1790 he advertised “chairs of various patterns, some of which are entirely new, never before seen in this city.”[17]

There is also the question of whom Hains himself may have trained. His only known apprentice is Isaac Nixon, who ran away twice in 1794. A Dutch joiner, Francis Carolus Grum, also worked in his shop, probably as a journeyman or indentured servant. Hains appears to have had a sizable workshop; in 1800 he is listed in the U.S. census as head of a household containing one boy aged ten to fifteen and three boys aged sixteen to twenty-five—likely all apprentices and journeymen, given that his own son was then only five years old. In November 1800 Hains advertised his remaining stock for sale; he is listed as a grocer in the city directories for 1801 and 1802. Yet he did not entirely give up working with wood, as in February 1801 the mayor of Philadelphia appointed Hains “Inspector of all the Cord wood brought by land into this city for sale.” No doubt his knowledge of wood accrued from years of working as a cabinetmaker helped qualify him for this position, which was a critical one, since the price of firewood rose dramatically in Philadelphia between 1795 and 1800. Demand was especially high in the city, where large institutions such as the Pennsylvania Hospital and government competed with households for firewood and drove up the cost considerably. Due to the expense, poor families were more likely to buy firewood in smaller quantities as needed, including at its peak during the winter months. In an effort to control prices, local regulations were enacted to ban the purchase of firewood for resale within the city between September and March.[18]

Two months after his appointment as the city’s firewood inspector, Hains sold his interest in the Spread Eagle Tavern and other buildings to his sister, Catharine, and her husband, Christian Dannaker (apparently the transaction did not go as planned, however, as in 1810 an advertisement announced the partitioning and sale of the property at a sheriff’s sale). In 1803 Adam Hains is listed again in the city directory as a cabinetmaker at 135 North Third Street. This is the last time that he appears in the Philadelphia directory, although his mother, Catharine, remained at 135 North Third Street through 1810. On January 2, 1804, Adam Hains “Cabinetmaker” of Philadelphia purchased a stone house and twelve acres of land near the village of Pricetown in Ruscombmanor Township, Berks County. Thereafter he appears consistently in the annual tax records and is listed in the 1810 through 1840 censuses as a resident of Ruscombmanor Township. His occupation is still given as cabinetmaker in an 1815 deed, although another deed in 1820 identifies him as a yeoman. In August 1820 Hains was one of five men appointed to a “committee of vigilance” for Ruscombmanor Township. In 1826 he purchased an adjacent tract of ten acres and house from the estate of Leonard Messersmith. By 1832 he had added a tanyard to the property, as he was taxed on that in addition to the two houses, twenty-two acres, one horse, four cows, and a Dearborn wagon. Adam Hains died on May 23, 1846, and was buried at St. John’s Reformed Church in Pricetown, about ten miles northeast of Reading, the county seat. His widow, Margaret, and their six grown children all remained in Berks County. Margaret and sons Henry Martin and William D. Hains were also buried at St. John’s. Daughters Maria Hains Jones and Sarah Hains Tea were buried at Charles Evans Cemetery in Reading, while daughter Hannah Hains Oyster was buried at Christ Lutheran Church in Dryville, Berks County. Another daughter, Eliza Baish Hains, married schoolmaster William Mason of Kutztown and taught a needlework school there in the early 1840s (fig. 40).[19]

Although it has long been assumed that Adam Hains did not make furniture after he moved from Philadelphia to Berks County, the identification of his trade as cabinetmaker in 1815 suggests otherwise. The recent discovery of a highly sophisticated group of inlaid federal furniture made in Reading also raises the question of whether Hains may have played a role in its development. Several tantalizing hints of his ties to Reading and continued woodworking emerge from the historical record. Adam Hains’s brief will, written on March 24, 1829, was witnessed by J. Wampole Sr. and Jr. By the time of Adam’s death in 1846, both Wampoles were deceased. To verify that the will was written by Adam Hains, two additional witnesses came forward: Hiester H. Muhlenberg and John S. Pearson. In their depositions, both men stated that “they were well acquainted with the hand writing of Adam Hains...[and] that they [had] often seen him write.” Both men were longtime residents of Reading, where John S. Pearson (1805–1885) was a prosperous dry goods merchant and Hiester H. Muhlenberg (1812–1886) was the son of Henry Augustus Muhlenberg, pastor of Trinity Lutheran Church in Reading from 1803 to 1829 (see fig. 91). Adam Hains’s daughter, Sarah Baish Hains, was married at Trinity Lutheran Church to Samuel Tea. A second piece of evidence is the marriage of Adam Hains’s daughter Hannah to Thomas Oyster, who was likely related to Reading clockmakers and brothers-in-law Daniel Oyster and Daniel Rose—whose movements were often housed in elaborate cases (see figs. 47, 55, 93). Another clue is at St. John’s Church, where a date stone in the side of the building is engraved in German Fraktur lettering with the inscription “St. Johannis Kirch / Bau-Meister / Wm. D. Hains / A.D. 1841” (fig. 41). William D. Hains, who served as the master builder (Baumeister) for the church, was born to Adam and Margaret Hains several months after they moved to Berks County in 1804. Who better to have taught him woodworking than his own father? William is listed in the 1850 census in Ruscombmanor Township as a farmer and head of a household that included his wife, Sarah; his niece Mary Ann Oyster (an orphan); his wife’s niece Sarah Heebner; and two carpenters: his older brother, Henry Hains, aged fifty-two; and “Lyman Heevener” or J. Lehman Heebner—who later moved to Reading and continued to work as a carpenter. William D. Hains lived on and inherited the ten-acre property adjacent to his father’s original land in Ruscombmanor Township. The 1876 edition of the Illustrated Historical Atlas of Berks County shows not only a tanyard but also a “Cabt. Shop” located on the property line between the two tracts owned by Adam Hains. Last, the will of Margaret Hains, written less than a month after Adam Hains died in 1846, was witnessed by two men: William Strong, a Reading attorney (who also wrote the will), U.S. Representative, and future U.S. Supreme Court justice; and William Weimer, a Reading cabinetmaker-turned-businessman. Although no inventory was taken when Adam died in 1846, the detailed inventory taken at Margaret’s death in 1855 includes tools such as a timber saw and a lot of planes. Furniture included a marble table valued at $5, two corner cupboards at $4, an eight-day clock at $8.50, a dining table at $2.75, and a bureau at $2.50. Given the high quality of Hains’s Philadelphia-made furniture and these hints that associate him with both Reading and a continued involvement in woodworking, it seems likely that Hains had some connection to the production of Reading’s most extraordinary group of inlaid furniture—although no firm evidence has yet been found. The next section will explore this furniture in more detail.[20]

Reading’s Inlaid Federal Furniture

Located about fifty-six miles northwest of Philadelphia near the east bank of the Schuylkill River, Reading was laid out in 1748 along the Great Road, which stretched from Philadelphia to Carlisle, where it intersected with the Great Wagon Road leading into the Shenandoah Valley. This privileged location made Reading a central point in a supply chain that linked urban goods and backcountry consumers; a loaded wagon could travel from there to Philadelphia in only two days. When Berks County was founded in 1752, Reading became the county seat, and a brick courthouse was erected ten years later (fig. 42). Local deposits of iron ore gave rise to a booming iron industry in Berks County, where numerous forges and furnaces dotted the landscape. Until the use of anthracite coal became common starting in the 1840s, these ironworks were fired by charcoal; as a result, much of Berks County’s forests had been cleared by 1800. Wealthy ironmasters were among the foremost members of a local elite who frequently chose to patronize local craftsmen and artisans, such as Daniel Udree (1751–1828), proprietor of the Oley Furnace and a member of the U.S. House of Representatives from 1813 to 1815 and 1820–1825. In Udree’s striking, full-length portrait, he holds a lump of iron ore in one hand and a pick in the other; a ledger book inscribed “Oley Furnace July 4th 1799” lies open on the desk behind him (figs. 43, 44).[21]

Despite the English origins of the town’s name, the majority of Reading’s inhabitants were German-speaking immigrants and their descendants. In 1790, when the first U.S. census was taken, Berks County as a whole had the densest concentration of German-speaking people in the entire state of Pennsylvania, comprising 85 percent of the county’s population. At the same time, Reading’s population of 2,235 residents was largely German. By the late 1700s rising prosperity enabled the town’s elite to embark on a series of building campaigns, including the construction of a monumental brick church for the Lutheran congregation in 1791–1794, under the direction of master builder John Cunnius (1733–1808), who had emigrated from Germany in 1749. The steeple of Trinity Lutheran Church dominated the town for decades, as seen in a view of Reading executed in 1837 by German immigrant F. A. Holzwart (figs. 45, 46). Reading craftsmen produced a variety of sophisticated objects, including ornately carved clock cases from the workshop of John Cunnius, silver made by three generations of the Mannerback family, and portrait miniatures such as the one of silversmith George Heller (figs. 47, 48). Among the most prominent early residents was Dr. Bodo Otto, who emigrated from Germany in 1755 and served as a senior surgeon for the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War (figs. 49, 50).[22]

At the turn of the nineteenth century, Reading became the center of production for one of the most sophisticated groups of inlaid furniture made in the early American republic—so sophisticated that many of the pieces, including four card tables and a sideboard, have previously been attributed to Philadelphia on the basis of their inlaid bellflowers and serpentine tops. Most examples that have been identified to date are tall clocks with locally made movements and distinctive inlaid bellflowers, which are identifiable by their nearly identical shape and the use of pointed oval or, less often, rounded centers, the tops of which are darkened by sand shading. The plainest cases have only limited inlay, primarily stringing and a few bellflowers, while the more elaborate models utilize highly figured woods and profuse inlay. The clock cases can be firmly assigned to Reading based on the discovery of a case signed and dated in 1809 by Reading cabinetmaker Daniel Rhein and his apprentice or journeyman Henry Quast (figs. 51, 52). The signed case has horizontal backboards with tongue-and-groove joints between them; the backboards are chamfered at the ends and nailed to the back of the clock. Another clock case with related construction and inlay has rounded, rather than pointed, bellflowers (figs. 53, 54). Yet another clock case, with inlaid vines rather than bellflowers, is also known. The most fully developed example is a mahogany and satinwood case with an eight-day, six-tune musical movement by Daniel Rose (1749–1827), one of Reading’s leading clockmakers (figs. 55, 56). The pediment is veneered with alternating light and dark wood, emulating the rays of the sun, with an image of a conch shell inlaid on the central plinth. Brass capitals and bases adorn the columns on the hood, while the dial is ornamented with images of the Four Seasons in the corners and an American eagle at the top. Several case pieces have also been identified, including a tall chest of drawers with rounded bellflowers like the clock case in figure 53 and a slant-front desk with rays inlaid on the exterior of the lid similar to those on the clock pediments (figs. 57, 58). On the interior, images of flowers set within oval plaques are inlaid on the document drawers flanking the prospect door.[23]

The distinctive bellflower inlay on these pieces enables the reattribution of two pairs of card tables and a sideboard from Philadelphia to the Reading workshop of Daniel Rhein. One of the tables has a firm history of descent in the Muhlenberg family and was owned by Maria Salome (Sally) Muhlenberg (1766–1827) and her husband (figs. 59-61). The youngest daughter of Lutheran minister Henry Melchior Muhlenberg and his wife, Anna Maria Weiser, Sally married Matthias Richards (1758–1830) on May 8, 1782. The couple lived first in New Hanover, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, before moving to Reading. A saddle maker by profession, Matthias served in the American Revolution as a member of Daniel Udree’s battalion of the Berks County militia from 1777 to 1778. In 1780 he was commissioned a major in the Fourth Battalion of the Philadelphia County Militia. After the war, in 1788, Richards was appointed a justice of the peace, an office he held for forty years. He became a merchant, a Berks County judge from 1791 to 1797, and member of the U.S. Congress from 1807 to 1811. By the time of his death in 1830, Richards had accumulated household furnishings worth more than $730, including a clock valued at $20, piano at $30, six looking glasses, a clothespress, corner cupboard, settee with cushions, and two card tables worth $10.[24]

The Muhlenberg-Richards pair of card tables have serpentine tops above a conforming satinwood frieze with seven oval fields outlined in mahogany string inlay (fig. 62). A band of alternating light and dark wood runs along the bottom of the frieze, while the edges of the tabletop are ornamented with light-wood stringing. The square, tapered legs are inlaid with bellflowers and light-wood stringing, terminating in contrasting, dark-wood cuffs (fig. 63). The other pair of card tables has no provenance but is inlaid with identical bellflowers and was clearly made by the same hand, the most significant difference being the use of rectangular plaques with ovolo ends on the aprons (figs. 64-66). All four tables share the same unusual construction technique of forming the substrate for the rounded corners with two large, horizontally laminated pieces secured by a scarf joint (fig. 67). In comparison with the Philadelphia card tables made by Adam Hains, which have hefty 1 1/4-inch-thick hinged rails, the Reading card tables have more slender 1-inch-thick rails. One of the most distinctive features of the tables are their curvaceous tops—with ovolo corners and serpentine fronts—a shape found on only a tiny fraction of American card tables (fig. 68). Heretofore, the known examples of this form were made in Baltimore, Newburyport, and Philadelphia. A large-scale version of this serpentine shape is also found on a mahogany sideboard that can now be attributed to the shop of Daniel Rhein (figs. 69-71). Although the inlaid bellflowers are nearly identical to those on the card tables and clocks, the pointed oval and dot borders outlining the drawers and doors of the sideboard are unique. Retaining its original silver-gilt hardware, the sideboard is constructed with chamfered drawer bottoms and very narrow dovetail pins. The case dividers are attached to the backboard via four large, square tenons, which are secured with 1/8-inch-thick wedges. Although the original owner of the sideboard is unknown, it descended in the Ludwig family of Berks County until 1847, when Miss Ann Ludwig sold it to John C. Hepler of Reading.[25]

Another form that can now be attributed to the workshop of Daniel Rhein is the case of a square piano made by John Haberacker (1780–1846), who worked in Reading as a piano and instrument maker during the early 1800s. At least four Haberacker pianos are known to survive, including an elaborate example that descended in a branch of the Rittenhouse family of Philadelphia (figs. 72, 73). Built of highly figured mahogany with a satinwood nameboard, the piano has inlaid bellflowers on the front legs that relate closely to those found on the clock case signed by Daniel Rhein and Henry Quast (see figs. 51, 52) as well as the card tables and sideboard. The nameboard is ornamented with elaborate painted decoration of Grecian scrolls, anthemion, and acanthus leaves based on designs in Sheraton’s Drawing-Book (see fig. 19). Although piano makers often built their own cases, it was not unusual for them to collaborate with cabinetmakers. Haberacker may not have found much of a market in Reading for his instruments, as he later focused on building furniture and identified himself as a cabinetmaker in his will of 1845.[26]

Daniel Rhein and Henry Quast. The primary maker of this extraordinary group of inlaid furniture, Daniel Rhein, was born on November 8, 1778, and died on December 1, 1868. His parents were David Rhein (1733–1801), who emigrated from Germany in 1751, and Maria Apollonia Meyer (1734–1809). Daniel was likely trained by his father, who was a joiner and Reading’s first undertaker. Daniel’s older brother Henry (1774–1843) and his nephew Henry Jr. (1799–1873) were also cabinetmakers. In 1817 “Daniel Rhein, Cabinet-Maker” advertised in The Berks and Schuylkill Journal, noting his location on West Penn Street opposite the printshop of Johann Ritter & Co. and advising prospective customers that “his new ware-room now exhibits an handsome specimen of the best and most fashionable furniture, chiefly made out of mahogany....He is also enabled to give his ware a superior polish, not only durable, but in beauty far surpasses the usual or common mode of polishing....Cherry, walnut, and common work made as usual, and on the most liberal terms.” Also in 1817 Rhein was listed along with Daniel Rose, John Miller, and John Birkenbine in a notice advising the public about the disbursement of money to aid “unfortunate persons who suffered in the falling down of Mr. Krauser’s house.” Rhein himself was paid $2 “in part for a coffin.” In 1820 Rhein advertised for rent a two-storey brick house, currently occupied by “Jacob Oyler, chairmaker,” and adjoining Rhein’s own house on West Penn Street. Rhein continued to make furniture of the latest styles, including an Empire period mahogany-veneered chest of drawers with looking glass that bears the stenciled inscription “D. Rhein / Cabinet Maker / Reading, Pa” on the undersides of several drawers (fig. 74).[27]

The second name on the signed clock case is that of Henry Quast (later spelled Quest), who was born on October 20, 1790, to Nicolaus and Maria Quast of Philadelphia and baptized on January 16, 1791, at St. Michael’s and Zion Lutheran Church. A native of Bondorf in Baden-Württemberg, Germany, Nicolaus Quast immigrated to Philadelphia on the Union in 1774. On April 3, 1781, he married Maria Eva Anthon at St. Michael’s and Zion. Six of the Quasts’ children were baptized there: Johannes (b. 1782), Georg (b. 1784 and d. young), Sarah (b. 1785), Georg (b. 1786), Heinrich (b. 1790), and Samuel (b. 1794). In the 1790 city directory, Nicolaus Quast was identified as a plasterer by trade and a resident of Cherry Street. By the early 1800s at least some members of the Quast family had moved to Reading, where Henry probably trained as a cabinetmaker in the workshop of Daniel Rhein. Henry’s brother, Samuel Quast/Quest, became a clockmaker and likely trained under the Reading clockmaker Daniel Rose, for whom he made a clock movement in 1812. By 1813 Henry and Samuel had moved to Maytown, East Donegal Township, Lancaster County; by 1850 they had moved to Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, where Henry is listed in the 1850 U.S. census as a carpenter. Henry lived to be at least eighty years old, as he is listed in the 1870 census.[28]

Having identified the inlaid card tables and sideboard, together with the related clock cases, as the product of Reading rather than Philadelphia cabinetmakers, let us now turn to consider their painted clock dials. On May 24, 1797, Reading clockmaker and storekeeper John Keim announced in the Readinger Zeitung that he had received via Philadelphia a shipment of English clock faces. Only two years later, in 1799, clockmaker Benjamin Witman of Reading advertised in the same newspaper that he had begun “manufacturing clock faces in all their different parts. It gives him pleasure to announce that he can make in a short time [clock] faces as well as they are made in England and sell them for a reasonable price.” On the basis of this ad, scholars have long recognized Benjamin Witman as one of the first in America to produce painted clock dials. Yet there has been much debate as to who was actually responsible for making the clock dials, which involved two distinct skills—metalworking and painting. As a clockmaker, Benjamin Witman had the requisite knowledge to fabricate a sheet iron dial and attach its components. Before the dial was assembled, however, the face and any additional elements, such as a moon phase wheel, had to be painted. The so-called Witman dials—which bear the names of not only Benjamin Witman but other clockmakers including Daniel Rose, Daniel Oyster, and George Faber (who were all related by marriage)—are distinguished by the high quality of their painted imagery, suggesting that they were decorated by a professional painter or painters. Common motifs include allegorical images of the Four Seasons in the spandrels, a spread-winged eagle on the moon phase disk, and the use of the same transfer-printed Western Hemisphere map, one rotated about thirty degrees (figs. 75-77). Sufficient variation exists to indicate there were likely several painters of Reading dials; the following discussion is focused primarily on only one subgroup. Some have identified a Reading painter named Jacob Witman as the dial painter, while others have speculated that it was a German émigré named Frederick Christopher Bischoff (1774–1834), who arrived in Reading circa 1799. Further complicating the picture is the presence of a William Witman, to whom a portrait of Reading clockmaker Daniel Rose has previously been attributed (see fig. 93). New research into the Witmans clarifies their relationship and firmly establishes William Witman as the probable dial painter and Jacob Witman as Reading’s most significant portrait painter before 1800.[29]

The Witman Family and Reading Clock Dials

Unraveling the tangled genealogical relationship of Benjamin, Jacob, and William Witman is critical to understanding who made the painted clock dials as well as a sizable group of portraits featuring Reading’s most prominent citizens. The answers to these questions shed light on the importance of kinship and ethnicity in the formation of patronage networks as well as the larger material world of German-speaking people in the early American republic. Benjamin Witman is the easiest to identify, as only one person of that name lived in Reading at the time. Born in 1774, he was active in Reading by 1796 as a clockmaker. His shop was located on Callowhill Street next door to the home of his father-in-law, Dr. John A. Otto, a son of Dr. Bodo Otto (see fig. 49). In 1819 Benjamin announced in the Berks & Schuylkill Journal the opening of a brush manufactory. Benjamin appears in the 1850 census as a resident of Reading, with his occupation listed as clockmaker; he died in 1857. The painters Jacob and William Witman are more difficult to identify owing to the simultaneous presence of multiple men by these names in Reading and Philadelphia.[30]

Jacob and William Witman. Documentary evidence about artists Jacob and William Witman helps to piece together their careers and, ultimately, their identity. Jacob is not listed in the 1790 census, presumably because he was not head of a household. By 1791 he resided in Philadelphia, where on October 13 he announced in the General Advertiser that he had moved to 12 Cherry Street, between Third and Fourth, where “he paints portraits on reasonable terms, and will warrant good likenesses...also sign painting executed with dispatch.” This notice continued to run through November and December. On September 15, 1792, Jacob placed a new advertisement, giving his location as 42 Fourth Street, near Chestnut. Identifying himself as a “Portrait and Sign Painter,” he proclaimed his ability to paint portraits “with striking likenesses, on the most reasonable terms—Also Sign Painting and Fire-Buckets, done in the best manner, and with expedition.” In 1793 the Philadelphia City Directory listed “Witman, Jacob, painter” residing at 136 Chestnut Street. The next record of Jacob Witman is on May 22, 1795, when the Columbianum exhibition—the first major public art exhibition in America—opened in Philadelphia. Listed in the catalogue of exhibited works is “JACOB WITMAN, Portrait Painter, Reading, Pennsylvania,” with two entries: a “Portrait of himself” and “Portrait of a Gentleman.” The next trace of Jacob Witman is on September 16, 1796, when he promoted himself in the Impartial Reading Herald as a “Sign, Likeness, and Miniature Painter” and informed patrons that he “still continues to carry on his business...as usual, at his house in Penn, the corner of Prince streets” (fig. 78). The same newspaper carried an ad by Benjamin Witman on the front cover, announcing the opening of his clock and watch shop on Callowhill Street in Reading (fig. 79). The last record of Jacob Witman is a notice in the October 2, 1798, issue of Claypoole’s American Daily Advertiser in Philadelphia, stating “DIED a few days ago, Mr. Jacob Witman, Limner.” Because no burial records for Jacob Witman have been found in Reading, it is likely that he died in Philadelphia during the yellow fever epidemic that killed thousands during the summer and fall of 1798.[31]

The most definitive clue to artist Jacob Witman’s life is the notice of his death in October 1798. In Philadelphia, a Jacob Witman/Whitman died in February 1798; thus, he can be ruled out as the artist. A Jacob Witman of Reading lived from 1776 to 1823; he can also be excluded. By process of elimination, the remaining Jacob Witman, born on February 7, 1769, can securely be identified as the artist. This Jacob was the youngest son of Christopher Witman Jr. (1725–1778) and his wife, Maria Barbara. After working as a shoemaker from 1756 to at least 1762, Christopher became the proprietor of a tavern located prominently on Penn Square in Reading, overlooking the courthouse (see fig. 42). He was one of three county commissioners when the courthouse was built in 1762, and his initials are carved into the keystone of the arch that once stood above the main entry. He served on the local Committee of Observation and as the county treasurer from 1775 until his death in 1778. Although Christopher Witman Jr. was only fifty-three years old when he died, he left a large estate to be divided among his widow and seven children: John, William, George, Abraham, Catharina, Jacob, and Daniel. The oldest son, John, inherited Christopher’s house and lot 34, located on the corner of Penn and Queen Streets, while Abraham inherited a half interest in the tavern (lot 32) on Penn Square and a set of shoemaker’s tools. William received £315, Abraham and Catharina each £350, and Daniel the other half interest in the tavern lot. Jacob, aged nine, was bequeathed £350 and two Bibles, one in German and one in English.[32]

Several clues help determine that artist Jacob Witman was the first cousin of painter William Witman and uncle of clockmaker Benjamin Witman. Born in 1770, William is listed in the Reading tax records as a painter. In 1826 the Readinger Adler announced the death of William Witman, “Anstreicher” (painter), aged fifty-six, on September 20. The burial records of Trinity Lutheran Church in Reading note that his father was Henry Witman. Born Johann Heinrich Witman (1734–1817), he was the brother of Christopher Witman Jr.—making the painters William and Jacob Witman first cousins. The pension file of John Witman (1749–1818), oldest son of Christopher Witman Jr., names Benjamin Witman as his son and thus the nephew of artist Jacob Witman. To summarize, artists Jacob and William Witman were first cousins; the clockmaker Benjamin Witman was Jacob’s nephew. The three men were also close in age; in 1790, Jacob was twenty-one, William was twenty, and Benjamin, sixteen. Since Jacob Witman died in 1798, he can be excluded as the dial painter, making William Witman the strongest candidate to have painted Benjamin Witman’s clock dials. On July 21, 1796, William placed an ad in the Impartial Reading Herald seeking an apprentice in the “Painting, Glazing, and Gilding Business” (fig. 80). The same newspaper also carried an advertisement by Benjamin Witman announcing the opening of his clockmaking business. William’s ad clearly identifies his trade as an ornamental painter who had the skills in painting and gilding needed for decorating clock dials. Additional evidence that William Witman was the painter of the clock dials comes from the presence of a watercolor drawing inscribed “1809 WW” on the side of a tall clock with a movement made by George Faber (1778–1834), who is thought to have apprenticed in Reading with Daniel Rose (Faber’s uncle) before he moved to nearby Montgomery County (figs. 81, 82).[33]

Having thus established that William, rather than Jacob, Witman was the likely painter of at least some of Benjamin Witman’s clock dials, what then can be attributed to Jacob? Based on the documentary evidence, Jacob Witman clearly specialized in portraiture rather than ornamental painting—thus calling into question the long-standing attribution of Daniel Rose’s portrait to William Witman (see fig. 93). The recent discovery of Jacob Witman’s signature on a portrait makes it clear that he, rather than William Witman, was the painter of a remarkable group of portraits depicting members of prominent Reading families in the 1790s.