Sala Bosworth (1805–1890), Landing of the Pioneers, Marietta, Ohio, ca. 1840. Oil on canvas. 37" x 40". (Private collection; courtesy, Decorative Arts Center of Ohio.) On April 7, 1788, the first forty-eight members of the Ohio Company of Associates landed at the confluence of the Ohio and Muskingum Rivers. They were met by several dozen Delaware Indians, led by Captain Pipe, who were trading with the residents of Fort Harmar (seen in the background), an army post established to clear the land of squatters and make room for legal settlement.

Joseph B. Warin (ca. 1768–1796), Vue de Marietta sur de bords de l’Ohio, Marietta, Ohio, 1796. Watercolor on paper. Dimensions not recorded. (Western Reserve Historical Society.)

Silhouettes of Joshua Shipman (1767–1822) and Sybil Chapman Shipman (1768–1828), ca. 1787. Cut paper. 7 3/4" x 6 1/4". (Private collection; courtesy, Decorative Arts Center of Ohio.)

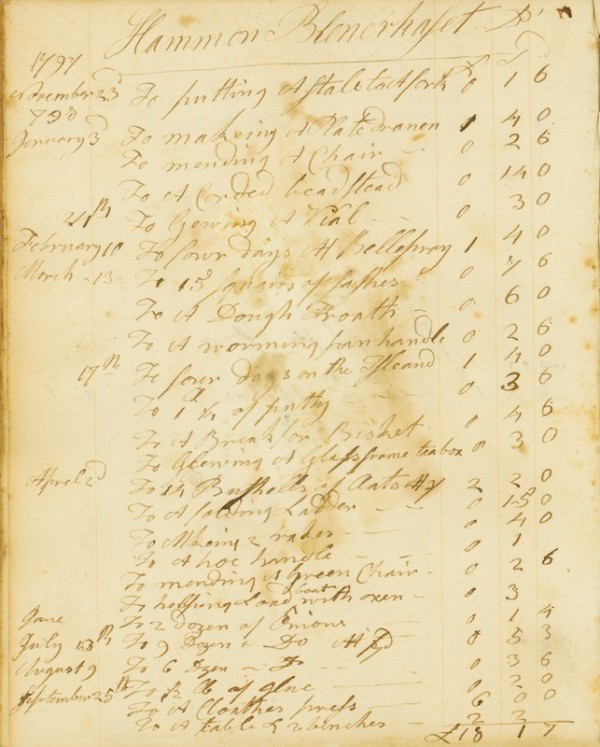

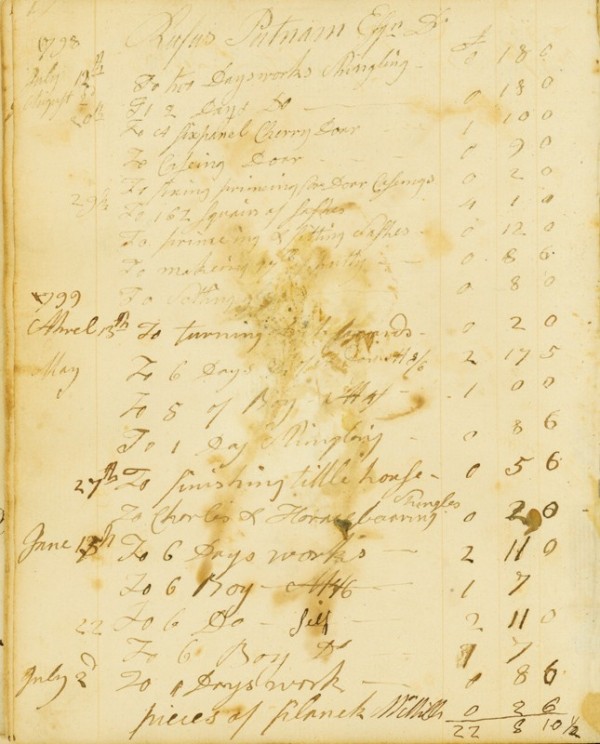

Page from Joshua Shipman’s account book, Marietta, Ohio, 1797–1798. Pen and ink on paper. 8" x 6 1/4". (Collection of the Slack Research Collection, Legacy Library, Marietta College.) Wealthy Irish immigrant Harman Blennerhassatt built a plantation home on an island in the Ohio River near Parkersburg, Virginia (now West Virginia). He hired numerous Marietta craftsmen, including Joshua Shipman, to build and furnish the home.

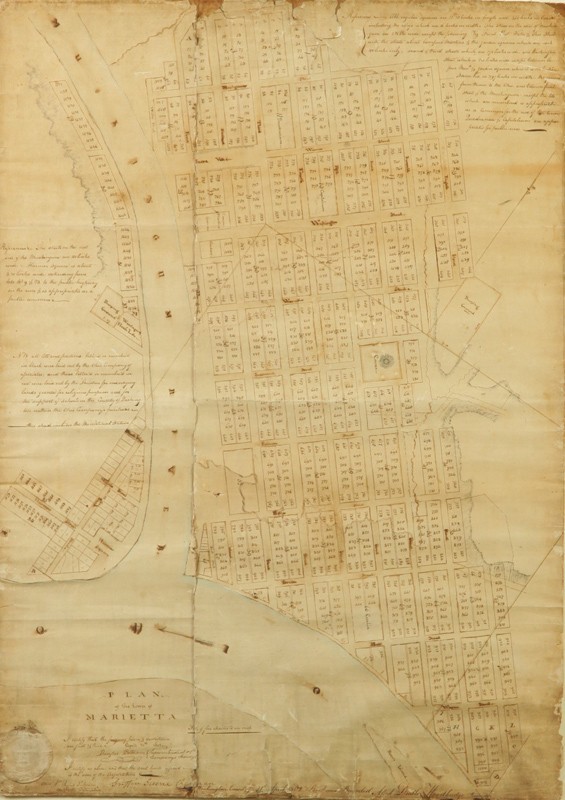

Rufus Putnam (1738–1824), plat map of Marietta, Marietta, Ohio, 1802. Pen and ink on paper. 43 1/2" x 34 1/2". (Private collection; courtesy, Decorative Arts Center of Ohio.) As a principal member of the Ohio Company of Associates and as Surveyor General of the United States, Rufus Putnam created many maps of early Marietta.

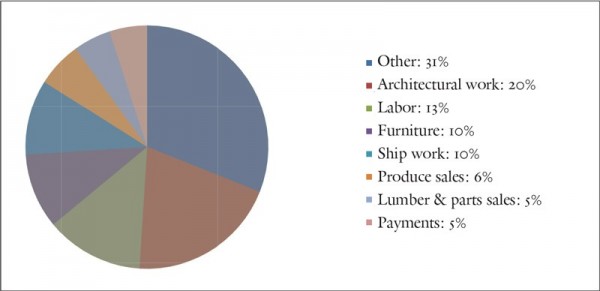

Transactions by Job Type

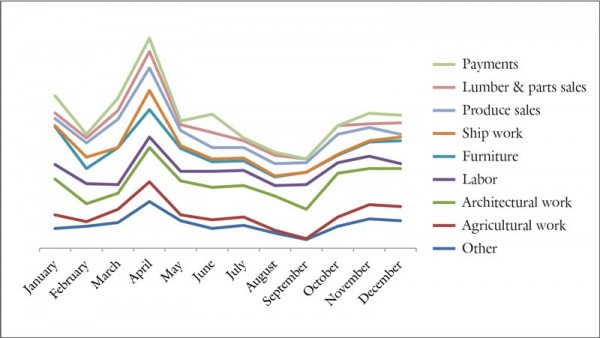

Average Monthly Transactions by Job Type

Postcard, 1907. Photographic print. 3 1/4" x 5 1/4". (Private collection.) This early twentieth-century view of the Rufus Putnam house shows the west bays, which Joshua Shipman added in 1787–1788, at the back of the house. These bays were stripped down to the timber frame during the renovation of the house in 1966–1972.

Page from Joshua Shipman’s account book, Marietta, Ohio, 1798–1799. Pen and ink on paper. 8" x 6 1/4". (Collection of the Slack Research Collection, Legacy Library, Marietta College.) Based on account book entries from 1797 to 1799, it is clear that Joshua Shipman was largely responsible for the addition to Rufus Putnam’s house.

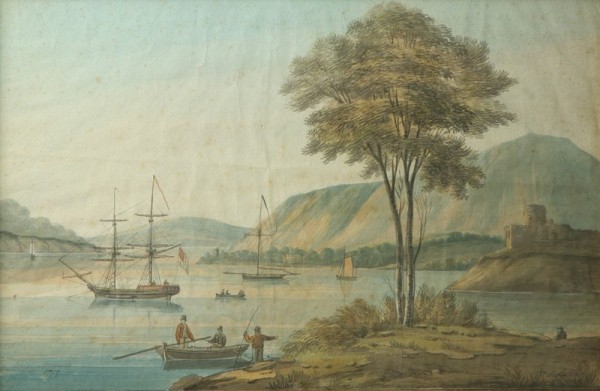

William Moffat (1775–1850), View on the Ohio, America, 1792, Marietta, Ohio, ca. 1825. Watercolor on paper. 11 1/2" x 17 1/2". (Private collection; courtesy, Garth’s Auctions, Inc.) Moffat was an English captain in the East India Company. This romanticized view of the confluence of the Ohio and Muskingum Rivers was likely executed in the 1820s or 1830s, decades after the date in the title and long after the shipbuilding industry had ceased. Moffat depicts Fort Harmar as constructed of stone, rather than wood, and the hills around Marietta as larger than they are.

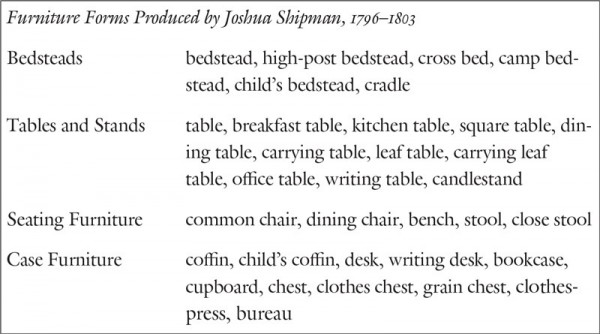

Furniture Forms Produced by Joshua Shipman, 1796–1803.

Table attributed to Truman Guthrie, Washington County, Ohio, 1790–1800. Tulip poplar and oak. H. 26 1/4", W. 35 1/2", D. 23 1/4". (Courtesy, Ohio History Connection, Campus Martius Museum.) This simple “sawbuck” table is probably similar in design to the form Shipman described as a carrying table. The name suggests a table that folds for easy transport, such as campaign (or camp) tables used in the military. They are often similar to this table but lack the additional cross braces and utilize dowels, rather than nails, in the battens, to allow for folding.

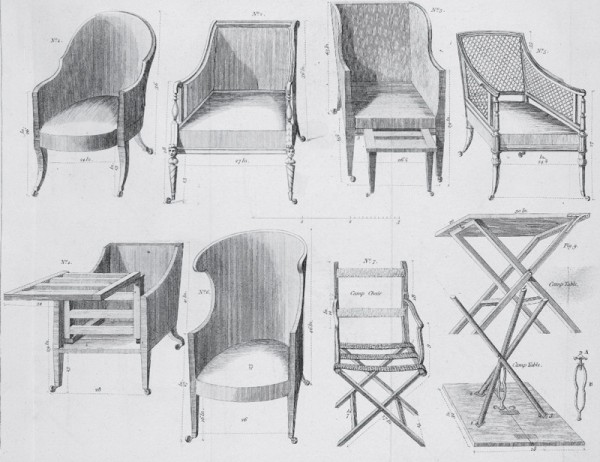

Design for a folding camp table. Thomas Sheraton, Cabinet Dictionary (London, 1803). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) Sheraton’s designs reflected his belief that furniture made for military use “must be made very portable.”

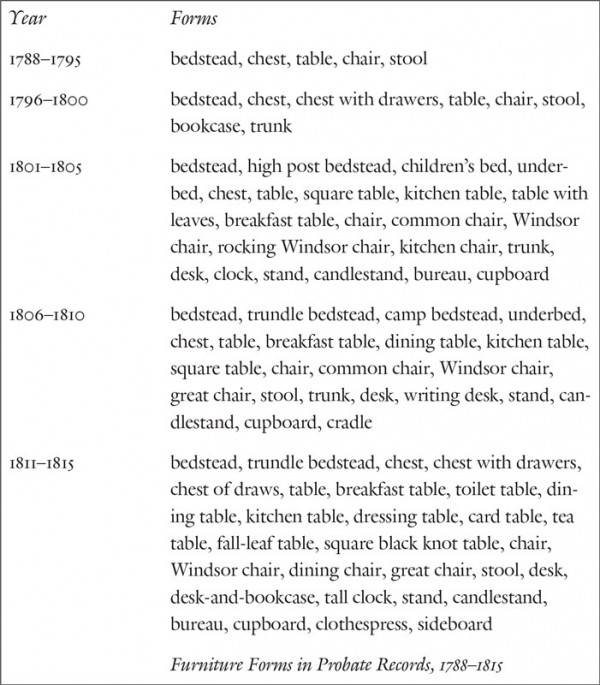

Furniture Forms in Probate Records, 1788–1815.

Detail from Joshua Shipman’s account book, Marietta, Ohio, 1797. Pen and ink on paper. 8" x 6 1/4". (Collection of the Slack Research Collection, Legacy Library, Marietta College.)

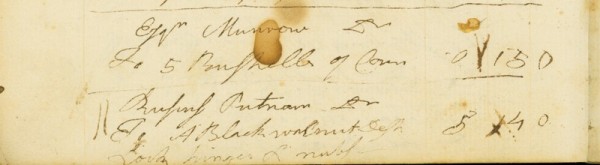

Detail from Joshua Shipman’s account book, Marietta, Ohio, 1798. Pen and ink on paper. 8" x 6 1/4". (Collection of the Slack Research Collection, Legacy Library, Marietta College.)

In April 1788, having traveled most of the winter, a group of New England settlers landed on the edge of the newly formed Northwest Territory, just at the point where the Muskingum River merges peaceably with the Ohio (fig. 1). Over the next few years, Marietta, as they named the immigration in honor of Marie Antoinette, would bear witness to the first real wave of settlement west of the Appalachians, as thousands would slide downriver, borne on flatboats they had boarded in Pittsburgh. Newcomers typically disembarked on what became known locally as “the Point,” short for “Picketed Point Stockade,” a fortification constructed on the eastern shore of the Muskingum at the confluence (fig. 2). Although the region, fertile and accessible as it was, seemed poised to draw a steady stream of settlers, “Indian troubles,” which would not be truly put to rest until the signing of the Treaty of Greenville in 1795, prompted many westward-looking immigrants to drift by in favor of the growing cities of Cincinnati, Louisville, and Saint Louis.

Early residents must have found life in Marietta filled with incongruities and contradictions. The muddy little river town grew steadily, with records showing the population in 1800 at around 500 (a number that increased to 1,500 by 1806) and about 5,400 in all of Washington County. However, Marietta’s growth appears slow compared with that of the boomtown of Cincinnati, which was formally established only a few months after Marietta and where the population of Cincinnati and Hamilton County had ballooned to more than 15,000 by 1800. Yet, thanks to the strong infusion of New England wealth and prominence among the early settlers of Marietta and to the flatboats shuttling back and forth laden with trade goods, it was possible to buy imported silk or Queensware, along with books, prints, glass, and any number of fashionable goods. Trade not only built on the wealth of the original settlers but also created wealth for the new, as a shipbuilding industry flourished. Full-scale seaworthy vessels, more than twenty, were actually constructed on the banks of the Ohio, loaded with local agricultural goods (mostly flour and salt pork), then sailed downriver on the surge of the spring melt. Whereas flatboats had to stop in New Orleans to move cargo to larger ships (and pay a duty), the Marietta-built ships bypassed the city, stopping in the Caribbean, selling the goods, and were freighted with more goods (often sugar) that were transported to eastern ports like Philadelphia, where the crew would sell both the goods and the ship before venturing back home overland. The nascent industry was quite profitable but soon collapsed under a combination of the treacherous falls in the Ohio River near Louisville and the suspension of international trade due to Thomas Jefferson’s Embargo Act in 1807.[1]

As the new nation looked westward, there were differing views on how the country should expand (or if it should expand at all). Jefferson and his fellow Republicans envisioned the West as an agrarian paradise, a place for his republic to strengthen and grow, and a place where men would carve out egalitarian communities and govern them themselves. However, the founders of Marietta, led by General Rufus Putnam, were, by and large, Federalists. To them, the great Ohio and Mississippi River systems were a perfect means to establish outposts in a tidy chain reaching far into the wilderness, outposts that would successfully relay resources out of the frontier, which they saw as a vast expanse of exportable raw materials, and back to the East, where there were war debts to be paid and a new government to fund.[2]

From the city’s very founding, Federalists had a fairly tight grip on early Marietta, and being in business could be a politically charged undertaking. One path to success was to court the sizable influence and patronage of the town founders, but to do so required one to adopt their Federalist views or at least to abandon the more autonomous hopes of an independent farmer on a growing homestead. Early residents often seemed to have to choose between the two, making a ringing political announcement in their choices. Shifting away from the Federalist ideas, which were in many senses an updated view of colonialism, required hard work and a skillful balancing act. Through the account book of Joshua Shipman, a young joiner from Saybrook, Connecticut, we can see this process unfold, and in some senses, Shipman’s efforts parallel those of the country in which he lived, as the late eighteenth century also found the newly formed United States working to develop an identity and to realize the promise of the lofty rhetoric that had fueled the Revolution.

Shipman and his family relocated to the Ohio Country shortly after it opened for settlement, but much of his past remains a cipher (fig. 3). For the most part, his life is indistinguishable from that of so many other unknown and lost lives in history, but for his account book, which was rediscovered in the summer of 2002. Marietta College, which holds the account book, had the title page from the volume catalogued in its special collections, but it was believed that the volume itself had been lost. While sorting through a file of unprocessed collections, an account book was found, clearly that of a woodworker of some kind, but lacking any identifying title page. It quickly became clear to anyone who had viewed the catalogued title page that this was the volume to which it belonged.

Most of what is known about Shipman comes from two principal sources: a biographical sketch published in the Marietta Register in January 1879; and the privately printed reminiscences of Joanna Shipman Bosworth, Joshua Shipman’s granddaughter. It was through the ownership of a single share of the Ohio Company of Associates, the land company responsible for orchestrating the first official community north of the Ohio River, that the family found its way to Marietta. Perhaps as a means to give a young family a strong start, Samuel Shipman, Joshua’s father, partnered with Levi Chapman, who had a daughter, Sybil, to purchase one share, which could be had for $1,000.00 in depreciated Continental currency or $125.00 in gold. Joshua and Sybil had married in 1786 or 1787 and headed west to the family’s land in Ohio a few years later in 1790. After favorable reports back to Connecticut from his daughter, Levi moved his family west in 1794 as well.[3]

Sybil Shipman had already had three children by the time she and Joshua left New England in 1790. (They would have twelve children in all, but of their three oldest children born in Connecticut, only Charles survived to make the journey to Ohio.) After abandoning their original plans to travel in the company of fellow Connecticuter Joseph Buell and his family, the Shipmans went to western Pennsylvania overland, as did most of those going to the Northwest Territory. They ended their land journey in Robbstown, Pennsylvania, known today as West Newton, a town southeast of Pittsburgh that straddles the Youghiogheny River, just south of where it flows into the Monongahela River at McKeesport, which is another short distance from the heart of Pittsburgh, where the Monongahela merges with the Allegheny River to form the headwaters of the Ohio. Here, at Summrell’s Ferry, Shipman met another Connecticuter, Ebenezer Nye, and together they built a flatboat, disassembled wagons and loaded both the wagons and the oxen onboard, and floated the rest of the way via the Youghiogheny, the Monongahela, and the Ohio Rivers to Marietta, where they reassembled their wagons on arrival in 1790.

With winter bearing down, Shipman built a small log house near Washington and Second Streets, where the family lived until the Indian Wars forced them to retreat into the security of the stockade. After the Treaty of Greenville enabled a more lasting peace in 1795, Shipman moved his family just a short distance downhill from the fort to Front Street on the Muskingum River. According to the Marietta Register, the cabin was disassembled and the materials recycled into the new home.[4]

The earliest reference to Joshua Shipman and furniture making involves, ironically, the making of a desk-and-bookcase by someone else. Shipman’s granddaughter Joanna relays in her memoir that family legend always held that her grandfather had the first log cut in the first mill in the Ohio Country. Shipman later employed a young cabinetmaker, Alexander Hill, to make a desk-and-bookcase from these walnut boards. Whether or not this is true, a desk-and-bookcase is listed in Shipman’s inventory and valued at $20.00. Joanna, who married artist Sala Bosworth, inherited the walnut secretary with this history and later passed it to her niece Mary Gates, who married into the Dawes family, in which it purportedly descended.

Ultimately, however, aside from marginal references such as this one scattered in family and local histories, Joshua Shipman was a largely unknown figure until the rediscovery of his account book, which represents the earliest known craftsman account from Ohio (fig. 4). The volume contains approximately 170 pages and 1,500 entries, with the earliest dating to October 1793 and the last to July 1813 (although entries are sparse and sporadic before 1796 and after 1803) and the most comprehensive coverage from August 1796 to February 1804. Shipman’s record keeping was exceedingly sloppy, and only roughly half of the transactions are dated with even the month and year, the remainder being incompletely dated or undated entirely. (It is also possible that, despite the range covered in this volume, there may have been others. One entry for customer and Rhode Island émigré Gilbert Devol reads, “brought from old book,” which certainly suggests the existence of records that predate this volume.) While it is commonly referred to as an account book, the book is more accurately described as a mix of daybook and account book, although there is little repetition between the two aspects. In the first sixty pages, Shipman records daily transactions—through early 1799—and for the next sixty pages, he records customer accounts. Shipman then uses the next forty pages again to record daily transactions (mid-1801 through mid-1803), and he concludes his bookkeeping with twenty pages of accounts that relate to a short-lived shipbuilding industry before filling the final few pages with a simple index by customer name.

Shipman’s seemingly lackluster efforts as a bookkeeper were not aided by the variety of currencies in play in Marietta during this period (a situation that certainly plagued record keepers throughout the young nation). Most transactions are listed in pounds-shillings-pence, although later records occasionally have totals in dollars and cents. Payments, interestingly, tend to appear more often in dollars than other transactions do, and in a couple of instances in which Shipman totaled a customer’s account he converted it to dollars and cents. Conveniently, on July 18, 1797, Shipman notes a $2.00 loan to William Bridge, which is recorded at 12s., hence establishing a conversion rate of $1.00 to 6s., a rate that seems to be stable and consistent over the period of years covered in the volume (and is reinforced by a few other recorded loans).

Perhaps part of the reason Shipman’s record keeping was so disordered is the fact that specie was in general very scarce on the frontier. Like any rural businessman, Shipman accepted nearly anything as barter—from lumber and nails to pork and calico. Many accounts were paid down with “sundreys,” the nature of which is not further described. Shipman’s accounts ran months—years, in a number of cases—without ever being fully settled, no doubt contributing to his flexible definition of what constituted payment. Of all the accounts kept, only one, that of David Putnam (one of Rufus Putnam’s many relations to go west), is ever shown as being paid in full, and of the eighty payments recorded, only eight were paid with cash and those were with fairly small dollar amounts.

In Marietta, one is never far from a river, certainly not geographically, and, during the frontier period at least, one was rarely very far removed from the rivers economically, either (fig. 5). In the early days of the settlement, many of the residents made their living selling river-brought merchandise, hosting river-working men, or producing river-bound goods. Shipman, interestingly enough, did little of this, apparently choosing instead to work his New England connections to find employment. While we do not know where or with whom he trained or even if he had formal training, he is variously described in contemporary and later sources as a carpenter, contractor, and housewright, as well as “house joiner” by his granddaughter Joanna, and his account book illustrates that he engaged in an even richer variety of work, including making a significant quantity of furniture. Yet even at this distance, the rivers would still generate some income for Shipman, via his work for the shipbuilders in the opening years of the nineteenth century.

When viewed as a whole, Shipman’s account book shows him to be a successful entrepreneur, building a solid and consistent business based on a variety of work and a reliable network of customers. During the years for which the account book contains the most thorough records (1797–1803), Shipman recorded between 100 and 225 transactions per year, with stronger showings from 1797 through 1799, during which time he logged considerable transactions for a small handful of customers.

An analysis of his clientele makes it clear that Shipman made a secure living for himself in the shadow of the town founders’ patronage. For the 1,395 transactions in which a customer could clearly be identified, Shipman had a total of 162 clients, and of the 79 with identifiable origins, only four were non–New Englanders, with 56 of the 79 hailing from Massachusetts or Connecticut. Of the 162, 54 can be considered “regular” customers, as they logged five or more transactions, and within that group, 15 had more than 25 transactions. Shipman’s number-one customer during the years of the account book was town founder, Revolutionary War general, and “dyed in the wool” Federalist, Rufus Putnam. Still, Shipman, though a staunch Federalist as well, did not discriminate. Two of his other key clients, after a few local shipbuilders, were Return Jonathan Meigs Jr., a Jeffersonian Republican who would serve from 1810 to 1814 as Ohio’s fourth governor, and Harman Blennerhassett, an Irishman who left his native country for a plantation home on an island in the Ohio River in present-day West Virginia. Another customer was the friend with whom Shipman had planned to travel west, tavern keeper Joseph Buell. Buell went west a New England Federalist but underwent a political conversion in the Ohio Country.[5]

As was typical in most rural or small communities, kinship networks also played a role in building Joshua Shipman’s clientele. His in-laws, the Chapmans, were customers (both father Levi and brother-in-law Joseph), and the brother of Shipman’s employee James Kelly married the sister of client James Flagg, who also, as a minor, happened to be the ward of another customer, Return Jonathan Meigs. And though not related by blood or marriage to Rufus Putnam, Shipman certainly gained entry into that family through his reputation. In addition to Rufus, Shipman recorded transactions with seven other Putnams, one of whom, William R., along with Jonathan Clark, was charged with appraising Shipman’s estate in 1823. Another very good customer was Revolutionary War veteran Christopher Burlingame, who in 1787 became the son-in-law of Rufus Putnam by marrying his daughter Susanna.

Of Shipman’s 162 customers, 74 of them bought furniture from him, 68 hired him for architectural work (everything from framing houses to glazing windows to even making the glazing putty), and seven were shipbuilders. Shipman’s diversification is apparent too in the 50 customers who bought produce from him, the 39 who hired him or his employees as laborers, the 74 who purchased items from him as various as tool handles and Jacob staffs, and the 23 customers who went to him for loans.

This diversity, which is readily apparent in nearly every account listed in Shipman’s book, was the key to his success; in fact, such diversity was crucial to the success of any rural businessman. In a frontier town such as Marietta, even with the help of a good customer base and a thriving river trade, specialization was extremely difficult. Most craftsmen who went west carried with them a broad set of skills. For example, Jonathan Sprague, who built a stone house on the Muskingum River ten miles north of Marietta circa 1800, was a millwright by trade but did all of the stonecutting, blacksmithing, and carpentry work for his home.

Likewise, Shipman, though primarily a builder of houses, engaged in a wide array of work, from painting to selling produce, manufacturing ship parts to, of course, making furniture (fig. 6). He helped set up Elijah Backus’s printing press. He provided parts for Jonathan and Gilbert Devol’s ships, and he worked on Gilbert’s house, also fashioning a “washing machine” for him. Shipman helped build and furnish the homes of many of Marietta’s most prominent families: the Putnams, Devols, Burlingames, Greenes, Buells, Pratts, and many more.

His records show that architectural work, mostly the construction of windows and doors, constituted the highest percentage—about 20 percent—of his sales, by the number of transactions (about 35 percent of the dollar amount), while various types of labor by Shipman and his employees made up about 13 percent by transaction (17 percent of the dollar amount). Ship work and furniture making each made up approximately 10 percent by transaction (20 percent and 13 percent of the dollar amounts, respectively). Produce sales amounted to 6 percent (3 percent in dollars). This amount included plenty of actual produce but other foodstuffs as well, along with the ubiquitous whiskey, and the sale of lumber and parts contributed another 5 percent (2 percent in dollars). Interestingly, payments recorded among the 1,395 transactions accounted for about 5 percent of Shipman’s entries (4 percent in dollars). Of those payments, it is worth noting that a small fraction, only about 10 percent, was paid in cash (about 15 percent in dollars). The vast majority of payments Shipman received, a staggering 85 percent of his income according to the account book, was in goods, typically produce and supplies, and sometimes even labor (often, Shipman assigned no specific value to such barter). The remaining transactions, nearly one-third of the 1,395 transactions (representing only about 5 percent in dollars), were for everything from manufacturing tool handles and signs to wool wheels (a type of spinning wheel) and hatchel boards. Shipman even made a flagstaff, Jacob staffs, and, in October 1801, several “espontoon” handles.[6]

A closer analysis of his account book shows a very clear pattern in Shipman’s work, but it does not mirror the typical seasonal cycles of a rural craftsman-cum-farmer (fig. 7). Most rural craftsmen focused on their agricultural and other outdoor activities during the spring and summer months, and then, as the weather turns in the fall and into the winter, they practiced their craft. For Shipman, spring was extremely busy, as illustrated by a significant spike in all types of transactions. Over the course of the account book, in April he averaged 22.4 transactions. These transactions included the expected categories, such as hiring out himself, his employees, and his oxen for farm labor, architectural work, and ship work, as this was the time of year that the Ohio River ran high, so blocks, deadeyes, and pump boxes were needed to help finish the ships for their downriver journeys. However, Shipman also experienced an increase in furniture output as well as produce sales (which included whiskey, butter, and other processed foodstuffs) and payments. These are categories typically seen more often in the fall and winter months.[7]

During the later spring, summer, and early fall—what one might term the farming season—Shipman’s business slides, bottoming out in September with only 10.3 transactions on average. This steady decline in all categories, with some categories such as agricultural and general labor, as well as ship work and produce sales with fewer than two transactions per month on average, suggests that he was otherwise engaged. Most likely, Shipman was working his own land, spending those summer months cultivating his out lot (all shares in the Ohio Company entitled the holder to a town lot and an out lot), and the fall months harvesting his crops. During the harvest, his business does pick up, and growth in all types of transactions is seen through the winter months.

Shipman’s accounts reflect generally little business in agricultural produce—average monthly transactions of produce sales, even during the peak month of April, never surpassed 2.5. Moreover, in the fall, when one might expect a surge in “country produce” payments on customer accounts, there are few. In fact, there are no payments at all listed in any September or October included in the account book. His business patterns, then, suggest that Shipman was not a craftsman who supplemented his income by farming but, rather, a farmer who supplemented his farming by building houses and making furniture. This pattern becomes even clearer after 1803, when transactions in his account book become fewer and fewer, likely signaling the complete conversion of Shipman’s business to farming.

Shipman and other craftsmen like him quite literally built Marietta. He helped build the Congregational Church, the courthouse, the jail, and the Muskingum Academy, for which he also made tables and benches. It had to be a stirring feeling to stroll around town, perhaps down to the Point, past the houses, stores, and taverns on one side and the ships on the other, recognizing that he helped shingle this building and provided window frames for that one, that his brick molds had helped form the bricks for a particular store or that the goods in the front windows were displayed on his shelves, to see his blocks (as in block and tackle) affixed to the masts of the ships preparing to sail south. While it is certainly possible that somewhere in Marietta, Shipman-made doors, shelves, window frames or sashes, or floors still survive, as yet, no documented example of Shipman’s work has been found.

Unlike many craftsmen who chose to live in homes at the Point, close to the source of their livelihood, the river trade, Shipman and his family lived farther north on Front Street, not far from the home of Rufus Putnam and the protection of the fortification called Campus Martius. In 1797, once the native hostilities were over and the fort was abandoned, blockhouses in Campus Martius were being sold off. Putnam purchased the blockhouse adjacent to his original home for $70.00 and had it disassembled, repurposing the materials to add the west section to his home, effectively doubling the size by converting it from two-over-two to a four-over-four dwelling (fig. 8). On July 10, 1797, Shipman recorded an entry for “pulling down the old house,” which took two and a half days and for which he charged one pound. He also charged 7s. 6p. for the labor of James and 5s. each for one day of labor by Messrs. Stone and Pierce (probably Stephen Pierce and Captain Jonathan Stone, both customers). Over the ensuing twelve months, Shipman records regular debits in Putnam’s account for work on the house, including the making and installing of doors, shingling the roof, and the framing, glazing, and installing of windows with a total of 162 panes of glass (fig. 9). Unfortunately, although the Putnam home still stands, the addition largely built by Shipman was skeletonized during a restoration in 1966–1972. The goal of this restoration was to take the house back to its original fort configuration, but it also had the unfortunate effect of removing all of Shipman’s work.

As mentioned, Shipman’s architectural work must, at one time anyway, have been all over town. There are in excess of 275 entries relating to this sort of work, and more than half pertain to the making, casing, and hanging of windows and an additional 10 percent relate to making, casing, and hanging doors. The account book, however, indicates that Shipman did all manner of architectural work, producing window blinds, chair molding, slitwork (square rough-cut boards used as studs and floor joists), window cornices, and window shutters, as well as laying floors, installing shelves, fashioning brick molds, priming and painting, building stairs, and shingling roofs. The aforementioned Muskingum Academy hired Shipman to build the basic structure and to do a fair amount of the finishing work, including the shingling. Jail superintendent Griffin Greene paid him in several installments for work on the building in late 1799, while in 1802 Shipman did a great deal of work on shipbuilder Gilbert Devol’s house. Over the years, he did various kinds of work on the house and shop of silversmith Azariah Pratt, laid floors for Rufus Putnam’s son and future judge Edwin Putnam and finished his office, built stairs for the store owned by successful merchant Dudley Woodbridge, made brick molds presumably used in the construction of the large home of Return Jonathan Meigs, as well as planed clapboards and provided various kinds of shelves, and constructed barns, smokehouses, and other manner of sheds.[8]

The variety and quantity of transactions allow us a great deal of insight into the pricing of this type of work in Marietta. Merchant and tanner Ichabod Nye paid Shipman for $71.24 worth of “joyner work,” whereas merchant and shipbuilder Benjamin Gilman’s “new house bill” in May 1803 tallied nearly $200.00. The jobs are often broken down in the account book, revealing that laying a floor cost $3.50 per one hundred board feet; window sashes cost 6p. per pane with larger 10- by 12-inch panes costing 12p. apiece; window frames ranged from 9s. to 15s., depending on the size, with shutters costing 12s. ($2.00) each; while doors ranged from 3s. to 5s. per panel (presumably based on size, although possibly on wood choice as well, though Shipman rarely records the wood choice for doors). Shingles brought Shipman $2.00 per 1,000 for hauling and another 12s. ($2.00) for installing the same number.

The second most frequent type of transaction record in Shipman’s account book is labor, various types of work performed by him and his employees. He recorded 211 transactions related to labor, divided among 44 customers, with his biggest customers being, again, Rufus Putnam and Return Jonathan Meigs, as well as Ichabod Nye, shipbuilder Edward Tupper, and merchant Dudley Woodbridge. The labor recorded was not just Shipman’s; over the course of the account book, 13 men are listed as being in his employ. Most of them appear to be casual labor, sometimes used on only one or two occasions, and some of them possibly operated as subcontractors. The names James Kelly and James Welch appear with the most regularity, frequently enough that they were both probably employed on a full-time basis. (Welch was often referred to just as “the boy,” and in February 1804 Shipman records the charging to Dr. Nathan Mackintosh for 23.5 days of labor for “the boy James W.” Edward Tupper was charged in September 1801 for ten days of labor by “the boys,” likely Welch and Kelly.) Shipman also hired out his oxen for agricultural labor. The oxen could be had for 3s. per day, the hired men for anywhere from 2s. to 9s. for the day, depending on the type of labor. Shipman’s own wages fluctuated occasionally from their normal 9s. a day, but for only one task, painting. Perhaps Shipman was not fond of painting, as he often charged an extra shilling a day when he recorded such a job. Whether he was fond of it or not, painting makes up a fair amount of his generic labor transactions, both his and the boys’, from general painting to specialty jobs (signs, ship name, etc.). They also did great deal of hauling and agricultural labor as well as a considerable amount of shingling.

Despite all this mundane work, Shipman’s account book also provides a rare, firsthand glimpse into that strange and fascinating industry in early Marietta: shipbuilding (fig. 10). Since his account book covers the peak years for shipbuilding in Marietta, we get a fairly clear picture of what local joiners may have contributed to the ships and what role shipbuilding may have played in their income. As mentioned previously, shipbuilding accounts for roughly 10 percent of the transactions Shipman recorded, of which very few are actually dated, but counted in those transactions are a considerable number and variety of ship parts, including pump boxes, cross trees, hearts, sheaves, bull’s-eyes, and deadeyes, as well as blocks in a range of sizes (singles, doubles, and triples, and from 2 1/2 to 16 inches long). Shipman also billed “the Gentlemen Owners of the Brig” for a “Table for the Cabbin” and painting “letters on stern.”

Shipman’s two principal customers in this fleeting but lucrative industry were Charles Greene (formerly of Rhode Island) and Benjamin Ives Gilman (of New Hampshire), Marietta’s earliest shipbuilders. Both men’s accounts are lengthy, but sadly, the ship-related transactions are undated. However, an amendment to Gilman’s account earlier in the book includes the total charges not only for his “New House” but also for the “Ship Muskingum.” The 200-ton ship was built for Gilman by Jonathan Devol in 1801. This fact suggests that it is likely the undated charges for ship parts listed in Greene’s account were for the construction of Marietta’s first boat, the 110-ton brig St. Clair. Stephen Devol, Jonathan’s brother, built the brig for Greene in 1800, and Commodore Abraham Whipple, whose celebrated career spanned the French and Indian War and the American Revolution before he settled in Washington County, commanded it on its voyage down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, and then, via the Caribbean, east and north to Philadelphia.[9]

While helping build ships was, perhaps, the most unusual aspect of the career of Ohio Country craftsmen, one very typical feature was that, like nearly every rural businessman, Joshua Shipman also traded in agricultural and other goods, if in smaller quantities than one might expect. Some of the produce he probably farmed himself, but since he readily took “country produce” in trade, he likely resold that which he did not need. Shipman recorded the selling or receiving of bacon, pork (even whole pigs), veal, butter, cheese, tobacco, corn, oats, and onions, as well as the ever-precious salt and ever-present whiskey. Other goods that regularly appear in Shipman’s records are tallow, soap, coffee, a variety of fabric and sewing notions, and even one pound of “Green tea of Bohea” (valued at 13s.).

Being a woodworker, Shipman also sold and received lumber and hardware as payment. Across 98 transactions, Shipman recorded 87 sales and 11 payments involving oak, poplar, elm, and black walnut boards (including more than five hundred feet of oak boards from Benjamin Gilman in the spring of 1802, possibly in payment for Shipman’s work on the Muskingum). Also listed among these transactions were hardware (nails, most often eight penny, as well as screws, hinges, and chest locks) and finishing supplies (linseed oil, white lead for paint, and putty for window glazing).

The making of the furniture, itself, may have only amounted to 10 percent of Shipman’s transactions, but it appears to have provided the most variety of any of his work (fig. 11). Among the nearly 150 transactions recorded relating to furniture among 74 customers are listed 144 pieces of furniture: 38 bedsteads, 36 tables of various types, 13 coffins, 8 candlestands, 7 chests, 6 cradles, 6 dining chairs, 8 benches, 4 bread troughs, 4 grain chests, 3 bureaus, 3 desks, 1 bookcase, 1 carrying board, 1 close stool, 1 clothes chest, 1 clothespress, 1 common chair, 1 cupboard, 1 firescreen, 1 “square board to write on,” and 1 stool. In addition to the furniture he made, Shipman recorded 21 jobs that entailed repairing or painting furniture.

Using the price differences and Shipman’s specific descriptors, it is possible to get a sense of these furniture forms and their variations and refinements. Bedsteads, for example, range from a camp bed listed at 10s. ($1.66) to a high-post bed for £4s. ($4.00), but it would appear that an ordinary bedstead (probably of poplar, with turned posts) could be had for 14s. ($2.33), since most are listed at this price.

The widest variety of types and prices, however, is found in tables. The three dozen tables that Joshua Shipman made include inexpensive forms, such as the 14s ($2.33) table made for Rufus Putnam’s office, to more expensive types, such as Benjamin Gilman’s writing table, for which Shipman charged £2.2s. ($7.00). Shipman made specialized tables, such as kitchen and dining tables, as well as fashionable breakfast tables (for which he typically charged £2.2s., or $7.00).

Perhaps the most unusual type of table listed is the “table for carrying” (fig. 12) or, as he described it in the November 8, 1799, sale to Messrs. Mathers and Sproat, “Table leaf to carry to woods.” There must have been considerable variety in these tables, since Shipman’s price ranged from 3s. ($0.50) to £1.8s. ($4.66). It is likely that this form is a folding table similar to those used by military officers, sometimes referred to as camp tables (fig. 13). Certainly the significant number of veterans of the American Revolution living in and around Marietta would have been quite familiar with such tables, and in a frontier settlement, portable work surfaces would have been highly useful. Although little information can be found on the partnership between John Mathers and Colonel Ebenezer Sproat, they were two of the four original surveyors for the Ohio Company, so it is not surprising that their work required a table that could be carried into the wilderness they were plotting.

A survey of furniture forms that appear in probate inventories during this time period provides a useful context in that it shows what forms were currently in use. Figure 14 illustrates that the opening years of the nineteenth century saw an explosion of new furniture forms listed in probated estates. Because items listed in inventories are generally not new, one can assume that the diversification and specialization of furniture that the early nineteenth-century probate records reflect likely happened in the closing years of the eighteenth century. In other words, local furniture production became very interesting after the cessation of native hostilities in 1795, and it is during this time that Joshua Shipman’s furniture production peaked. Between 1797 and 1798 Shipman made sixty-three pieces of furniture—nearly half of his production recorded in the entire account book.

This boom in production was not limited to Shipman’s furniture. As previously mentioned, during this same period, Shipman was experiencing an overall increase in business, with 200 or more transactions in each year between 1797 and 1799. He was not alone. In the years following the Treaty of Greenville, Mariettans could worry less about survival and instead focus on building a town. Immigration from the East, which had all but ceased during the Indian War, resumed. While the immigration to Marietta may not have been on par with that to Cincinnati, the frontier settlement did triple in size between 1800 and 1806. To merchants and craftsmen, new settlers meant new customers, and the increased traffic on the Ohio (both traditional flatboats and the newly constructed ships) meant access to even more new customers. As a result, the economy flourished, as did the likes of Joshua Shipman.

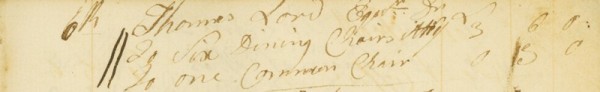

It is not surprising, then, that in the late 1790s a handful of Shipman’s customers ordered the most expensive furniture recorded in his account book. In February 1797 Shipman made a £5. ($16.66) bureau for shipbuilder Charles Green, and a year and a half later, he made a £6. ($20.00) clothespress for Harman Blennerhassett’s island plantation. For Thomas Lord (the brother of shipbuilder Abner Lord), Shipman made a set of “Six Dining Chairs At 11/” in March 1797, for which he charged him £3.6s. ($11.00). Shipman made very few chairs, and these were, far and away, the most expensive (fig. 15).

At that time, most chairs in Marietta were simple ladderback chairs with rush or woven seats. Such chairs were typically termed “common” or “kitchen chairs” and could be purchased for about $0.50. In fact, at the same time Thomas Lord purchased his dining chairs, Shipman also charged him 3s. ($0.50) for a “common chair.” By circa 1800 Windsor chairs had made their appearance in Marietta. Makers such as Thomas Ramsey provided his customers with a more fashionable chair at the cost of about $1.00 per chair.[10] At nearly $2.00 each, what did Lord’s chairs look like? Might they have been higher-grade Windsors, perhaps with upholstered seats? Or might they have been of cherry or walnut and modeled after eastern chairs in the Hepplewhite style and of mahogany? Unfortunately, no other details are known, and Lord’s expensive chairs must remain a mystery.

In fact, since no known piece of Shipman’s furniture survives, we have very little idea of what it looked like. Shipman only rarely mentioned the type of wood used in furniture production (when he did, it was either walnut or cherry—mahogany did not make its appearance in the Ohio Country until a few years later). Nor did he offer detailed descriptions in his record keeping, choosing only to list the forms. It is likely that since both he and most of his customers were New Englanders, the furniture he produced was, to some extent, styled after the furnishings he and his customers had left behind.

As one would expect, Joshua Shipman’s main customer, Rufus Putnam, was among those who purchased an expensive piece of furniture during this period. In April 1797 Shipman recorded a £5.4s. charge for a “black walnut desk.” The desk was one of about a dozen pieces of furniture Shipman made for his patron (fig. 16). It would seem that Shipman built and furnished the Putnam family home. In addition to overseeing the expansion of the house, Shipman made four bedsteads (12s.14s. each) and four grain chests (2s. each), a table for the office (14s. to make it and 1s.6p. to deliver and place it), a cherry table (19s.6p.), a kitchen table (£1.8s.), and a clothes chest (14s.).

Although much can be learned about Joshua Shipman from his account book, much remains unknown. According to the biographical sketch in the Marietta Register, at some point, presumably circa 1805 or 1810, Shipman left the woodworking trade and moved his family to a house he built on one of his out lots, where he worked his land until his death in 1823. One wonders if the dwindling number of transactions he recorded in his account book in the later years of its coverage signaled that this move was coming, was perhaps even planned. It may have been Shipman’s success in diversity, particularly during the boom years of the late 1790s, that allowed him to move away from building houses and making furniture entirely.

The transition from craftsman who farmed to full-time farmer may have always been Joshua Shipman’s intent. Otherwise, a more prudent, business-savvy decision would have been to join his fellow craftsmen at the Point and involve himself more fully in the prosperous river trade, as did his friend and fellow Connecticuter Joseph Buell. Buell kept his tavern, called the Red House, in the heart of the business district at the Point. There, Buell engaged daily with an incredibly varied clientele—merchants, craftsmen, flatboatmen, and others, some, like himself, from New England, but others from Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, and elsewhere. His culturally diverse community and his success within that community are likely what inspired Buell to largely abandon his New England Federalist roots, as evidenced by his southern-styled furniture, two pieces of which survive.[11]

By contrast, Joshua Shipman remained loyal to his New England origins and patrons, such as Rufus Putnam. He lived his Marietta life away from the Point, and although he readily sold furniture and performed work for non-Federalists (such as Buell), he clearly showed his fellow Federalists favor. Perhaps it is no coincidence that the last well-documented year is 1803, the year Ohio became a state, the year the Federalists lost their grip on Marietta, and the year Rufus Putnam was removed from his powerful post as surveyor general. It may be that with the loss of such influential patronage (and, within a few years, the loss of the shipbuilding industry as well) Joshua Shipman had no choice but to refocus his energies on farming.

The last glimpse of the life of Joshua Shipman the historical record provides is his probate inventory and appraisement, which was performed on December 17, 1823, by Jonathan Clark and William R. Putnam. Valued at more than $1,200.00 (with another $1,500.00 due from debtors), clearly life in Marietta had been good to Shipman. His inventory includes the desk-and-bookcase that tradition states was made by Alexander Hill, as well as a “large dining table,” a “cherry breakfast table,” eight Windsor chairs, and six kitchen chairs. Also listed are luxury goods, such as a “Looking Glass in the Parlor” valued at $1.00, silver tablespoons and teaspoons valued at $9.50, and a sizable library of books, including works on chemistry, geography, history, and literature. Of particular note is an “old Set of Joiners tools” (valued at $30.00). Though multiple workbenches and other tools, including multiple lathes, are listed, the description of Shipman’s joiner’s tools as “old” suggests not only that they were older but also that they may have been little used in later years.

Frederick Jackson Turner would, seventy years later in his landmark address “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” discuss at length the unique development of America, where forward, westward movement allowed for a constant building on the past in the East, drawing elements of a shared history along with each westward shift. In the small-scale version of his theory, Shipman’s tools are that historical remnant, having formed the foundation for Shipman’s new life in the West. Elevating him from the teeming masses who roiled westward in America for decades before and after, Shipman’s account book offers a brief but rich glimpse not only into the story of one such man but into the story of America itself. The settlement of Marietta, Shipman’s life, his work and its progression, are all microcosmic versions of the American frontier as Turner would one day speak of it, “a steady growth of independence,” away from the monarchical government of colonialism, away from the security of the settlements in the East, away from a reliance on patronage and labor for others, and a tenuous, tenacious stretching toward self-reliance. Exactly as Turner later delineated, drawing from John Mason Peck’s A New Guide for Emigrants to the West, Shipman moved upward, becoming a man “of capital and enterprise” himself, one of many who broke ground not only on the path west but on the path to the vision that would become the American dream.[12]

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Christopher Busta-Peck, Glenna Hoff, Brock Jobe, Claire Kegerise, Bill Reynolds, Linda Showalter, Dr. Ray Swick, and Ernie Thode.

Andrew R. L. Cayton and Paula R. Riggs, City into Town: The City of Marietta, Ohio, 1788–1988 (Marietta, Ohio: Marietta College Dawes Memorial Library, 1991), p. 58. U.S. Bureau of the Census, Decennial Census of Population, 1800–2000, by County, online, Ohio Department of Development, 2001, accessed August 8, 2013, http://urban.csuohio.edu/nodis/historic/pop_county18002000.pdf. Kim Gruenwald, River of Enterprise: The Commercial Origins of Regional Identity in the Ohio Valley, 1790–1850 (Bloomington: Indiana University, 2002), pp. 63–64; and Leland D. Baldwin, “Shipbuilding in Western Waters, 1793–1817,” Mississippi Valley Historical Review 20 (June 1933): 29–39.

For a thorough discussion of Marietta as a key part of a burgeoning commercial network in the early Ohio River valley, see Gruenwald, River of Enterprise.

“Joshua Shipman, Pioneer of 1790,” Marietta Register, January 18, 1879, p. 1. Joanna Shipman Bosworth, Papers of Joanna Shipman Bosworth, Being the Diary of a Carriage Trip Made in 1834 by Charles Shipman and His Daughters, Joanna and Betsey, from Athens, Ohio, to Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington, and a Family History (Chicago: privately printed by H. M. Dawes, 1914).

“Joshua Shipman, Pioneer of 1790,” p. 1.

If there was ever any doubt about Joshua Shipman’s political leanings, his granddaughter Joanna dispelled them in her memoir. She relates a story about her father (Joshua’s son), Charles: “When he was quite young he attended a political meeting in the court house with his father [Joshua], and they were dividing themselves into two parties by standing and he knowing where he belonged sprung into line with the federalists, which raised a great excitement and clapping of hands.” Bosworth, Papers of Joanna Shipman Bosworth, p. 36.

This percentage was calculated by totaling all of the transactions, converting them to dollars and cents (using the conversion rate 6s. to $1.00 that is found within the account book), and deducting the total payments received. This method is somewhat problematic, however, as a significant number of transactions (particularly in the categories of ship work and payments) include no monetary amount. Thus, tallying the number and kind of transactions rather than income is a more reliable method of illustrating the proportional diversity of Shipman’s business. However, the rough estimates of income percentage are still useful in illustrating the relative value of the various branches of his business. Espontoons, or spontoons, were also called half-pikes and were pole arms with a somewhat trident-shaped head that saw some use in the American Revolution.

Philip Zea, “Rural Craftsmen and Design,” in New England Furniture: The Colonial Era, edited by Brock Jobe and Myrna Kaye (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1984), pp. 58–59.

Contract between Joshua Shipman and James Lawton for building the Muskingum Academy, September 15, 1798, vol. 4, no. 122; contract for building a jail, vol. 3, nos. 72–74; bill from Shipman to Washington County for work on the courthouse, vol. 3, no. 79, both, Samuel Prescott Hildreth Collection, Marietta College Library.

A list of the ships built in Marietta, along with the owners and builders, appeared in the Marietta Register, March 24, 1881, and was reprinted in “Shipbuilding in Marietta,” Historical Marietta, Ohio, December 9, 2011, accessed August 17, 2013, http://historicalmarietta.blogspot.com/2011/12/ship-building-at-marietta.html.

For a discussion of Ramsey and his Windsor production in early Marietta, see Andrew Richmond, “The Fashionable Frontier: Thomas Ramsey, Windsor-Chair Maker in Marietta, Ohio,” Antiques 165, no. 5 (May 2004): 136–43.

For a thorough discussion of Buell, see Andrew Richmond, “Southern Sophistication on the Ohio Frontier: Furniture and Identity in Washington County, Ohio, 1788–1825,” American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2004), pp. 206–38.

Frederick Jackson Turner, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” a paper read at the meeting of the American Historical Association in Chicago, July 12, 1893, viewed online (accessed August 20, 2013), http://www.library.csi.cuny.edu/dept/history/lavender/frontierthesis.html.