High-post bedstead, New England, ca. 1800. Birch and pine with red wash. H. 72", W. 46 1/2", L. 70". (Courtesy, Austin T. Miller.)

Low-post bedstead, area of Barre, Massachusetts, 1800–1820. Woods not recorded; blue-green paint. H. 31 1/2", W. 51 3/4", L. 74 3/4". (Courtesy, Old Sturbridge Village, gift of the Derby family, 5.17.79.) The bedstead descended in the Bixby family of Barre.

Field bedstead, New England, ca. 1800. Birch and pine with red wash. H. 64" (without canopy), W. 54 1/2", L. 70". (Courtesy, Austin T. Miller.)

Turn-up, or folding, bedstead, Connecticut Valley in Massachusetts, 1740–1800. Birch and pine with red wash. H. 90 1/2", W. 50", L. 75 1/4". (Courtesy, Historic Deerfield, gift of Henry N. Flynt, 0845; photo, Penny Leveritt.) The bedstead is unusual in having trestle feet at the head; the tester has been reconstructed using new parts and refashioned old parts.

Trundle bedstead, New England, 1740–1800. Maple with red wash. H. 28", W. 36", L. 38". (Courtesy, Historic Deerfield, gift of Charles F. Montgomery, 0997; photo, Penny Leveritt.)

Folding cot bedstead, New England, 1800–1835. Maple, beech, and pine with red wash, and linen canvas. H. 35 1/2", W. 38", L. 76". (Courtesy, Historic Deerfield, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Henry N. Flynt, 53.094.2; photo, Penny Leveritt.) The headboard and footboard lift off, permitting the X-frame to fold.

Headboard of a French bedstead, area of West Leeds, Maine, ca. 1830–1840. White pine and maple grain–painted in black on red to simulate rosewood, accompanied by painted yellow banding and stenciled bronze decoration. H. 51 1/2", W. 53 1/4". (Courtesy, Maine State Museum, gift of Maine State Organization, D.A.R., 77.13.1.) The bedstead originally belonged to Stephen R. Deane (1816–1898), West Leeds, Maine, and was acquired from the family home.

Low-post bedstead with pillow panels, eastern Pennsylvania, 1790–1820. Yellow poplar with blue paint. H. 33 1/2", W. 51 1/2", L. 76 1/2". (Courtesy, Pook and Pook, Inc.) The bedstead formerly was in the collection of Dr. and Mrs. Donald A. Shelley.

Detail of the rear surface of the headboard of a field bedstead possibly by Brewster Dayton (d. 1796), lower Housatonic River valley at Stratford, Connecticut, 1780–1795. Yellow poplar and maple with red stain. (Bedstead) H. 85", W. 49 1/2", L. 73". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, 1952.0097.) The headboard is raised to expose the rabbeted top surface of the rails mounted with pins, or buttons, to accommodate cord or a sacking bottom. This object has a history of ownership in the Blakeman family of Stratford.

Low-post bedstead with pillow panels, eastern Pennsylvania, probably Montgomery County, 1800–1830. Maple and pine grain–painted in browns to simulate mahogany. H. 35", W. 49 3/4", L. 74". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, 1981.0010.) This bedstead has a history of ownership in Pottstown.

Low-post bedstead, probably New Hampshire, 1820–1830. Maple and pine grain–painted in red and black to simulate rosewood. H. 36", W. 53", L. 76". (Courtesy, Old Sturbridge Village, 5.17.38.)

Detail of a post of a high-post bedstead, Albany or New York, ca. 1800. Maple post with white paint and highlights in gold leaf. (Bedstead) H. 96 3/4", W. 57 1/4", L. 77 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, 1955.0786.) This bedstead reputedly belonged to Gov. Joseph C. Yates (1768–1837) and his third wife (m. 1800), Ann Elizabeth Delancey.

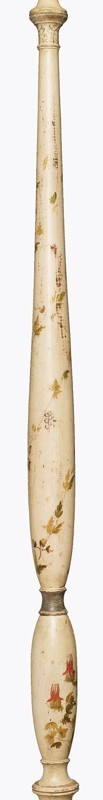

Detail of a post of a high-post bedstead, New England, 1800–1815. Cherry and birch with painted white ground and decoration of red blossoms and shaded leaves of green and gold with dark blue grapes and tan acorns, all accented by borders and striping in gray, black, and gilt. (Bedstead) H. 81 1/2", W. 54", L. 73 3/4". (Courtesy, Historic Deerfield, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Henry N. Flynt, 59.011; photo, Penny Leveritt.)

Low-post bedstead, coastal New Hampshire, ca. 1824. Maple and white pine with gray paint. H. 36 3/4", W. 53 3/4", L. 78". (Courtesy Woodman Institute, Dover, New Hampshire, gift of Mrs. Ellen Rounds, T1057; photo, Rob Karosis.) Mrs. Rounds inherited the bedstead from the Drew family of Dover in the 1880s. Inscribed on the rear surface of the headboard in gray paint with initials and date “M.T. 1824.”

Detail of a scalloped bedstead cornice, New England, 1770–1800. White pine with painted white ground and painted red edging (border). (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Museum purchase, 1970-147,11.)

Detail of serpentine-shaped bedstead cornice attributed with its bedstead to Langley Boardman (1774–1833), Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1800–1810. White pine cornice with painted black ground and painted red flowers accented by gold foliage and moldings. (Courtesy, Historic New England, Museum purchase, 1969.573.) The cornice and its bedstead are presumed to have belonged originally to William Hale (1765–1848) and Lydia Rollins Hale of Dover, New Hampshire, in whose family they descended.

Detail of a window cornice, probably Baltimore, Maryland, 1835–1850. Wood with painted black ground and gilded Greek key design. H. 7", W. 87 1/2", D. 7 1/2". (Courtesy, Maryland Historical Society, 1953.248.39.)

Detail of a window cornice (one of two), United States, 1825–1830. Wood and gesso with gilded ground and ornament, including Nelson balls, beading, and egg-and-dart molding. H. 7 1/4", W. 64 3/4", D. 9". (Courtesy, Munson-Williams-Proctor Art Institute, Museum purchase, 57.65.1–2.)

Window cornice (or valance), New England, 1830–1840. Pine with green paint and stenciled decoration. H. 7", W. 38 1/4". (Courtesy, The Henry Ford, 57.99.2.)

Detail of the cornice of a bedstead made by Jacob Sanderson (1758–1810), Salem, Massachusetts, 1807. Pine cornice with white, or off-white, paint and gilded sheaf of wheat ornament carved by Samuel McIntire. (Bedstead) H. 84", W. 58", L. 78". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of Miss Miriam Shaw and Francis Shaw, Jr., 122349.) The cornice and bedstead were made for merchant Aaron Waite, as per dated billhead.

Detail of an arched window cornice (set of three), probably New Hampshire, ca. 1807. Pine with off-white painted ground and light yellow painted fabric puffs, bows, and leafy border, all detailed with gilded accents, the fabric puffs accented along the bottom in deep amber and shaded in pale yellow. H. 10 1/2", W. 54 1/2". (Courtesy, Historic New England, Rundlett-May House, Portsmouth, N.H., gift of Ralph May, 1971.2042.)

Fragment of a bedstead cornice, probably New York City or New York State, 1770–1800. White pine covered with English red-on-white copperplate-printed cotton of ca. 1770. (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Museum Purchase, 1964-223,3.) The fragment is part of a cornice originally from the Glen-Sanders House, Scotia, New York.

Pigmented surfaces were relatively common in the late colonial and federal periods under study, and they provided colorful coatings for bedsteads and cornices, as attested in craft documents, probate records, period publications, and extant objects. The present study investigates both rural and urban examples made in a broad area that includes New England, the Middle Atlantic region, and the South. Unlike vernacular chairs and related seating, the subject of an article by the author in a previous volume of this journal, vernacular bedsteads and cornices have received little attention as a body of furniture. To these forms, when made of common woods, craftsmen applied colors, or “solid bodies” known as pigments, mixed with a fluid, or “uniting medium,” to produce a uniform, protective surface coating. The present investigation focuses on three common finishes: paints, washes, and stains. Painted finishes utilize pigment, or coloring matter, sufficient to cover the substrate with a homogeneous, opaque coating that adds some thickness to the surface. Washes require less pigment, their objective being to obscure only some detail of the substrate. They are translucent and relatively homogeneous. Stains provide some color, but only enough to accent the visual pattern of the substrate with a thin, transparent coating.[1]

Bedsteads

Craftsmen fabricated bedsteads in a full range of styles and colors during the late colonial and federal periods. Patterns identified most frequently in records are those with high posts, also called long posts (fig. 1); frames with low posts, alternatively termed common or short-post bedsteads (fig. 2); and field bedsteads, a few described in records as camp bedsteads (fig. 3). Field bedsteads, whose medium-high posts support an arched tester frame, originally were made to fold into compact bundles for easy transport and assembly in the field by military personnel. By the federal period most such frames had become more or less stationary. A few records describe a tall bedstead of another form as either “a Bedstead to turn up” or a “press Bedstead” (fig. 4). The side rails of this frame have joints near the head posts to permit the bedstead to fold against a wall. Additional joints at the foot posts allow the front legs to drop against the frame. When raised, some turn-up bedsteads were enclosed within a wooden case, or press. Among items of furniture sold at auction from a Boston, Massachusetts, estate in 1750 was “a Bedstead in a Painted Press.” Other frames might be concealed behind the curtains of a short tester frame or within a slipcase.[2]

Records also describe two bedsteads of low form and basic construction, the trundle (fig. 5) and the cot (fig. 6). The former takes its name from the trundles, or wheels (rounds), at the four corners of the low posts that permit the frame when not in use to be rolled under a larger frame. Craftsmen fabricated this form from the early colonial period into the nineteenth century. Hurst and Lybrand of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, advertised trundle bedsteads as late as 1823, and shop accounts list trundle bedsteads during most of the stated period. More insightful is information drawn from a published study of almost eleven thousand inventories filed through 1850 for households in Chester County, Pennsylvania, near Philadelphia. Among the hundreds of bedsteads listed, most of anonymous type, ninety-three trundle frames are identified between 1700 and the 1840s. In New England, Clark Peck of Danbury, Connecticut, paid William Chappel, a local furniture maker, 2s. 6d. (42¢) in 1798 for “turning rounds for trundle bead.” Of less consequence was the cot bedstead, a light frame of wood with a canvas bottom, the form made stationary or portable. The cot illustrated in figure 6 has removable head and footboards, permitting the frame to fold. Upholsterer George Haughton of Philadelphia sold military equipment and camp furniture in 1777, including “cott bedsteads to fold up,” as the Revolution began to engulf the city. Years later, in 1801, William Chappel charged 2s. (33¢) for “Mending cot beadsted” for a client in 1798 who had purchased a trundle bedstead for 12s. ($2.00).[3]

A frame of later date and sophisticated style noted in this study is the French bedstead (fig. 7), designed in France in the late eighteenth century and mentioned briefly by Thomas Sheraton in his Cabinet Dictionary (London) of 1803. Charles-Honoré Lannuier, a French émigré to New York, produced French bedsteads in that city during the first two decades of the nineteenth century. From New York and other urban locations, knowledge of the new frame spread to craftsmen and patrons in smaller centers of furniture production. The feature that distinguishes the French bedstead from other frames is its medium-tall headboard and footboard accompanied by medium-tall posts. Commonly, one long side of this frame was placed against a wall. Whether a long side or the head abutted a wall, a French bedstead might be accompanied by a wall-mounted dome hung with drapery. Many bedsteads were handsomely veneered; plainer frames were stained or painted.[4]

Regardless of bedstead type, color preferences varied. Green, blue, and red were popular choices from the mid-eighteenth into the early nineteenth century, a period when low-post, high-post, field, and trundle frames were prominent. An early reference, dating to the Revolution, is to “1 green camp bedstead” confiscated in Boston from Richard Lechmere, a Tory sympathizer. Daniel Rea Jr. of Boston recorded coating all four frame types with green paint during the 1790s, including a field bedstead “for a single person” for cabinetmaker John Bright. Another customer requested a green bedstead finished with a protective coat of turpentine varnish. Between 1795 and 1805 William Chappel of Danbury, Connecticut, made at least six high-post bedsteads painted green, a color identified four times for bedsteads listed in the 1792 Hartford Cabinetmakers’ Price List. Other New England craftsmen recorded painting bedsteads green, among them William H. Reed of Hampden, Maine; Silas E. Cheney of Litchfield, Connecticut; and Stephen Tracy of Plainfield, New Hampshire. The common pigment for painting furniture green was verdigris, described by Robert Dossie in Handmaid to the Arts as a “blue green colour” (see fig. 2). Sheraton noted that this “green may be compounded to any shade by means of white lead and king’s yellow.”[5]

When Nicholas Low, a merchant and land speculator of New York City, sought to purchase a green high-post bedstead with a sacking bottom in 1797, he turned to cabinetmaker Jacob Brouwer. The sacking bottom supplied by Brouwer was a common support for bedding in frames of all types. Made of sail duck, a sturdy linen fabric with a glazed surface, the sacking was installed in the frame with a cord laced through hand-sewn eyelets at the edges of the cloth. As early as 1742 Plunket Fleeson, an upholsterer of Philadelphia, offered householders “bedbottoms of good Duck.” More insight on the fabrication of a sacking is detailed in the purchase of a “Coloured poplar Trunnell Bedstead” by St. George Tucker of Williamsburg, Virginia, in 1811 from John Hockaday. The cabinetmaker charged 6s. ($1.00) for making the sacking bottom, employing “3 yds sail duck” at 12s. ($2.00), “6 yds Cord @ 3d. a yard” for 1s. 6d. (25¢), and “thread” at 1s.[6]

Other evidence of the use of green-painted bedsteads can be found in probate records, including that of William Walton, Esq., a New York resident, whose 1806 estate contained two such frames, one described as having the “Posts Sawed off.” Fenwick Lyell, a New York cabinetmaker who relocated in the early nineteenth century to Middletown in coastal Monmouth County, New Jersey, continued to produce fashionable furniture of fine cabinet woods and to fill occasional orders for painted furnishings. His green-painted bedsteads included field, trundle, and cot frames.[7]

Philadelphia records indicate that green-painted bedsteads were popular in that community. In 1773 John Cadwalader Jr. engaged the workman Eden Haydock to paint “6 Bedsteads Green” at his well-appointed town house in Second Street. Although the frames likely were for use by household staff in modest bedrooms, the choice of color was a deliberate one. Green remained popular for bedsteads at Philadelphia into the 1780s and 1790s, as indicated in the accounts of two prominent cabinetmakers. Bedsteads painted green are well represented in the accounts of David Evans, although only two frames are identified by type: “a Field Bedsted painted green” at £2.5.0 ($7.50 in later decimal currency) for Balthazar Woncher and “a Bedsted High Post Plain feet” constructed for £3.0.0 ($10.00) and “Painted...Green” at an additional 15s. ($2.50) for merchant William Lawrence. Evans also recorded a relevant exchange of services with a workman called “Limeburner.” The cabinetmaker supplied a green-painted bedstead “for which he [Limeburner] is to stuff my riding Chair Bodoy & top—I am to find materials Except wax and thread.” The agreed sum for the exchange was £2.5.0, a price that suggests Evans provided a field bedstead.[8]

On occasion Daniel Trotter, a Philadelphia cabinetmaker, chose to employ a painter outside his shop. From 1787 through 1791 John Gardner painted at least a dozen high-post and low-post bedsteads, although Trotter listed only an anonymous frame actually painted green. Trotter’s employment of painter George Flake in 1792 provides greater insight. Flake used green paint on three types of bedsteads—high-post, low-post, and trundle frames. The cost of painting each of the first two types was 7s. 6d. ($1.25); the charge for coating the trundle frame was 5s. (83¢).[9]

North of Philadelphia in Bucks County, Abraham Overholt (Oberholtzer) of Plumstead Township supplied German-American neighbors and other area residents with bedsteads from the 1790s into the early nineteenth century. Andres Wiesler and Elisabeth Rorian ordered tall frames painted green. Overholt recorded Rorian’s order as follows: “I made a bedstead...and I painted it green, I also made a top for it.” The total cost was £1.8.0 ($4.66). Bedstead frames in green also were a popular item west of Philadelphia in Chester County, where Margaret Schiffer’s comprehensive study of probate inventories through 1850 accounts for eighteen frames so identified.[10]

Painted bedsteads had a place in households furnished with more sophisticated frames. At his death in 1803 Stevens Thomson Mason, member of a distinguished Virginia family and a United States senator, owned two walnut frames and a mahogany “fluted bedstead” substantially valued at $30.00, although that figure may have included the bed hangings. In the same household, Mason’s country seat, Raspberry Plain in Loudoun County, stood a “Green painted” bedstead valued at $4.00, which may have been accompanied by some of the twelve green-painted chairs in the house.[11]

Based on a combination of written and visual records (extant bedsteads), blue appears to have been as popular a choice as green among householders for frames that supported their bedding. Chester County inventories suggest that blue bedsteads were particularly favored in eastern Pennsylvania, where there is record of a blue frame as early as 1716. In that year appraisers of John Hoskins’s residence in the town of Chester (now part of Delaware County) itemized a “blue bedstead containing [a] feather bed, boulster, 2 pillows, Coverlid [coverlet], & blankett.” The common blue pigment in general use during most of the period of this study was Prussian blue, recommended by its durability and low relative price. That Prussian blue was invented in Berlin only in 1704 raises a question, however, as to its early use on the bed frame in the Hoskins household. In this case it seems more likely the pigment was a blue verditer, a compound of unstable nature unless mixed with varnish.[12]

Elsewhere in the county, Amos Darlington Sr., a cabinetmaker of West Chester, sold blue bedsteads to several customers in the late 1790s, one fitted with a sacking bottom. Furnishings in the home of Adley Brown included blue bedsteads “Corded,” identifying use of a light form of rope to support the bedding. Blue bedsteads produced by Enos Thomas, a contemporary of Darlington, are identified by pattern in his accounts as high-post, “short”-post, and field bedsteads. John Mitchell’s house accommodated a “pair [of] high blew bedsteads.” Of little mention in records are the small, shaped side panels adjacent to the head posts of the bedstead illustrated in figure 8, which secured the pillows on some German-American frames. In Bucks County, Abraham Overholt may have had more calls for blue bedsteads than for green. Jacob Kraud purchased a blue “high posted bedstead” from him in 1793 for £1.6.0 ($4.33), the cost suggesting that anonymous blue bedsteads sold at comparable prices also had high posts. In 1775 David Evans recorded the sale of a blue frame at his shop in Philadelphia, where nine years earlier at the death of Daniel Jones, a local chairmaker, appraisers valued a “Blew Bedstead & Sacking bottom” at £1.5.0 ($4.17 in later decimal currency). As a maker of early turned chairs with rush bottoms, Jones could well have fabricated his own bedstead. Of further note is the half pound of Prussian blue pigment appraisers found among the contents of his home and shop.[13]

Across the Delaware River from Philadelphia, New Jersey craftsmen sold blue bedsteads. John Sager of Bordentown constructed “one Field Bedstead Sacken Bottom Painted Blew” in 1805 and charged his customer a substantial £3.0.0 ($10.00). On occasion Jeremiah Wood of Woodbury accepted bedsteads on credit from Job Kimsey. A “Common,” or low-post, bedstead in blue paint supplied in 1792 was valued at £1.1.0 ($3.50). A blue frame exchanged a decade later for a credit of £1.6.6 ($4.41) was unidentified.[14]

Evidence of blue-painted bedsteads occurs in a variety of New England records, and eastern Connecticut householders demonstrated a particular predilection for frames painted that color, although blue is not listed as a bedstead color in the 1792 Cabinetmakers’ Price List for Hartford. Between 1800 and 1803 Amos D. Allen of South Windham sold seven blue bedsteads of record for 12s.–14s. ($2.00–$2.33) apiece, the price suggesting they were basic low frames. A more costly frame sold in 1798 for $8.00 is described as “1 Bedstead high posts Painted blue, screws, sack[ing] bottom.” Large screws, termed bed bolts today, secured the four corners of the frame, permitting relatively easy assembly and disassembly. In later years Nathaniel F. Martin, a neighbor of Allen at Windham, recorded “mending bed Stid and painting blew,” the repair and refurbishing costing the customer 3s. 6d. (58¢). Samuel Loomis’s estate inventory drawn at Saybrook in 1814 records a bedstead assembly beyond the ordinary: “1 Blue bedsted, cord & underbed” (probably sacking) at $4.50, complemented by “1 Suit of Curtains on the same” valued at $5.00. At Newport, Rhode Island, Job E. Townsend posted pertinent work during the 1790s, when he painted a high-post bedstead blue in 1793 for Daniel Antony. Two years later Townsend constructed “a Palled [pallet] Bedstid” for Captain William Gardner at a cost of £1.10.0 ($5.00), charging 4s. (67¢) for “Painting the Same Blue.” The frame appears to have been for use on shipboard and may have taken the form of a couch.[15]

When dealing with the color red as a finish coat for bedsteads and other furniture forms, it is necessary to consider paint, wash, and stain. Records confirm use of these processes: a “bedstead painted red” and a “Bedstead stained.” Red paint was applied to furniture in two ways: by using sufficient pigment in the binder to conceal the surface pattern of the wood grain with an opaque coating; or by reducing the pigment content, thereby coating the wood with translucent color and revealing some detail of the grain (see figs. 1–6). Today the latter coating is referred to as a wash, although that term does not appear in the body of records consulted for this study. Whereas Nathaniel Whittock in his Decorative Painters’ and Glaziers’ Guide of 1827 describes “washing,” it is an “effect...produced in water colours,” a process applicable to fine art, but not pertinent to this study. Likely, washes were described merely as painted surfaces in craftsmen’s accounts; therefore, it is necessary to rely on a close examination of actual surfaces to distinguish between the use of paint or a wash. Bedsteads with red (brownish red) painted or washed surfaces of original or early age are relatively common in today’s marketplace. Most prevalent appear to be low-post and medium low-post frames, field bedsteads, and frames that turn up against a wall.[16]

The Pennsylvania household of John Hoskins, which in 1716 contained a bedstead painted blue, also was furnished at that date with a “red bed Containing A Cott Bed [possibly a canvas sacking], feathers bed, boulster & 2 pillows, one [bed] rugg, & 2 blanketts.” The style of frame is not identified, nor is that of later red-painted frames listed in craftsmen’s accounts, with a few exceptions. In 1802 Nathaniel F. Martin of Windham, Connecticut, recorded making for a customer a “bedsted painted red,” a color noted or implied nine times in the 1792 Cabinetmakers’ Price List for Hartford. Martin’s price at 12s. ($2.00) suggests the bedstead was a low, basic frame with a plain headboard. Of further note are many references in Martin’s accounts to painting materials, including pigments used in making red paint. Prominent are Spanish brown and red lead, with some mention of Venetian red. Several “spanish brown bedstids” are listed in the 1791 estate of Thomas Hoopes of Chester County, Pennsylvania, where cabinetmaker Matthias T. Foy’s estate identified his possession of “one Keg vanition read.” Spanish brown and Venetian red have a strong brown character. Red lead when roasted turns bright orange-red, although it is unstable and has a tendency to turn black over time. Nathaniel Martin likely favored Spanish brown or Venetian red for painting his bed frames, with the possible use of red lead as a base in a two-coat finish.[17]

Many red-painted bedsteads listed in records appear to have fallen into the 12s.–14s. range ($2.00–$2.33), describing a low, common frame. When probate records specify bedstead colors, Chester County, Pennsylvania, residents appear to have favored red paint after blue for coating their frames. Enos Thomas, a county resident, constructed low frames at higher prices, some probably accompanied by a sacking bottom. In Bucks County, Abraham Overholt made a red bedstead of unknown type fitted “with screws” and charged 18s. ($3.00). When Isaac Wright of Hartford, Connecticut, altered a red bedstead for Daniel Wadsworth in 1829, the charge also included “putting up & taking down” the frame. Other work in that community took place in the shop of Philemon Robbins, who had a brisk trade in French bedsteads during the mid-1830s (see fig. 7). Some were painted red, although there is no hint whether the coating was of a brownish cast, as in the use of Spanish brown or Venetian red, or of a brighter hue created by vermilion. Robbins’s charge for a French bedstead painted red varied from $3.00 to $4.50, the most expensive having a footboard.[18]

References to bedsteads finished in stain are relatively common in craftsmen’s accounts and describe a full range of frame types, some of substantial cost. In compiling his Cabinet Dictionary, Sheraton commented on the use of stain on wood: “at present red and black stains are those in general use.” The accounts of three craftsmen in this study identify several materials used in staining bedsteads. In 1808 Titus Preston of Wallingford, Connecticut, recorded “a high post bedsted for lacing with Crooked teesters [“O.G.” testers] stained with logwood & fustic.” Later, at Hartford, Philemon Robbins described an order for Mrs. Thomas Day: “a bedstead four feet wide out side, two bourds [head and foot], with screws and sacking, aqua fortis stain.” At Newport, Rhode Island, Job E. Townsend made “a field Bedsted Cherry Posts, Scrues, Staind with Spirrits.” The word “spirits” identifies use of spirits of wine (ethyl alcohol), a liquid when combined with coloring matter created a tincture suitable for staining wood. Major John Dunlap, a late-eighteenth-century cabinetmaker of southern New Hampshire, recorded several recipes for finishes containing spirits of wine. One was a stain for “orange Color,” or orange-red, the other a stain to simulate mahogany.[19]

Craftsmen likely used aquafortis (nitric acid) as a facilitator in the process of staining wood. The toxic liquid penetrated the natural tree resins and served as a fixative for a variety of stains. The tincture of logwood and fustic identified by Titus Preston as stain was extracted from plant materials. Logwood, or campeche wood, was imported from various locations in Central America and the West Indies. The wood chips when boiled produced a red dye. Sheraton identified fustic as “a hard yellow wood that grows in all the Caribee Islands. It is used in dying yellow.” By using the extracts of logwood and fustic together, Preston probably created a stained-wood surface with a distinct brownish cast approaching a light mahogany color. As an alternative to logwood, some craftsmen employed brazilwood, another tropical species. By the beginning of the nineteenth century, if not earlier, “Die Woods Chipped” were available commercially, as advertised by E. S. H. Leonard, a druggist of Providence, Rhode Island. Various authors also recorded a range of other ingredients used alone or in combination to produce a reddish liquid useful for staining wood.[20]

Records focused on red bedsteads finished in stain contain more detail than those describing painted frames. Large, sometimes moderately expensive, bedsteads in stain appear to have been reasonably popular among consumers in New England, the Middle Atlantic region, and beyond. At Litchfield, Connecticut, Silas Cheney recorded in 1814, “Staining seald [ceiled] Bedsted,” that is, a frame with tall posts and a covered top, or ceiling. Two stained high-post bedsteads without ceilings made earlier by John Sager at Bordentown, New Jersey, had sacking bottoms when delivered to the customer. High-post bedsteads in stain also were sought by householders at Philadelphia in the eighteenth century. David Evans made a stained high-post bedstead and cornice late in the Revolution, after the British had evacuated the city, for which he was paid with inflated currency of the period. Business had returned to normal by 1786, when the cabinetmaker exported a stained bedstead on speculation: “Shipd on Board the Sloop Betty, Jno Morrison, Master, 1 High Post poplar Bedstead Staind, with Sacking Bottom and cornice, which Said Master is to Dispose of to the Best advantage...in Virginia...& Remit the Neat [sic] Proceeds to me pr first safe conveyance.” Two other local craftsmen, Thomas Affleck and William Savery, also identified the wood of stained bedsteads as yellow poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera). Savery’s frame had “caps & bases,” likely describing a high-post bedstead with Marlborough legs and low conforming feet. Small brass disks covered the cylindrical holes that held the screws, or bolts, securing the frame.[21]

Evidence indicates that field bedsteads in stain represented a reasonable market item for cabinetmakers. Benjamin Bass’s 1819 Boston inventory describes a frame in the shop as a “Field single stained Bedstead.” Earlier, Benjamin Hathorne purchased a stained field bedstead from Isaac and Stephen Vose. At New York the household of Peter Curtenius contained two field bedsteads furnished with sacking bottoms, one frame stained, the other painted green. Records also identify the Philadelphia shops of William Savery and David Evans as producing stained field bedsteads. A new frame stood in Savery’s shop in 1787 at his death. Evans’s “Canopy Bedsted Stained,” made for Dr. Thomas Parke, was a four-post frame, the canopy elevated on testers. In addition, Evans supplied a “Sacking Bottom” with a “Cord” to lace the sacking in place.[22]

Figure 9 illustrates a detail from a red-stained field bedstead, being the outside back surface of the headboard and adjacent areas. The headboard, which is removable, is raised in slotted cleats on the inside faces of the head posts to expose the pins (buttons) mounted on the deep rabbet cut on the inside top surface of the rails. Also visible is the chamfered transition between the heavy, squared leg top and its slender head post, as well as the bead molding found on the outside top edge of all the rails. The round-top buttons were part of a system to create a support for the bedding inside the rails. Three basic systems were in use. Bedstead rails were drilled with spaced horizontal holes through which rope or lighter weight cord was woven lengthwise and crosswise. Chester County, Pennsylvania, inventories list both a “rope Bed” and “old Corded Bedsteads.” Another support method was to nail a heavy cloth border, such as sail duck, into the rails on plain inside rabbets. Through reinforced eyelets on the free edge of the border were laced one or more large pieces of heavy cloth with eyelet edges to form a sacking bottom. The 1793 Cabinet-Makers’ London Book of Prices includes an “Extra” charge of 6d. in bedstead construction for “Nailing in sacking.” The pins visible in figure 9 were part of a third support system. In 1829 John Mahargue of Halifax, Pennsylvania, charged 50¢ for “turning Bedstead posts & pins,” and at an earlier date William Chappel of Danbury, Connecticut, used the term “button beadsted.” Pins fulfilled one of two functions: they provided a “cross”-corded support in the wooden frame or accommodated a “sacking” bottom, both methods named or suggested in the 1792 Hartford Cabinetmakers’ Price List.”[23]

Craftsmen’s records contain some note of other stained frames. In 1798 Job E. Townsend constructed “a Turnup Bedstid with Scrues, Staind Poil[ishe]d” for a customer at Newport, Rhode Island. Later, in the mid-1810s, Abner Taylor of Lee, Massachusetts, produced a stained turn-up frame for one customer and “a trunelle Bedstead” for another. The accounts of Nathaniel Knowlton of Eliot, Maine, for 1830 demonstrate that sophisticated frames were not the sole province of craftsmen in large urban centers: they mention his “making a french Bedsted Staining and varnishing.” Several other records highlight particular bedstead parts, among them those of Elisha H. Holmes of Essex, Connecticut, who in 1829 placed casters on an unidentified stained frame. At East Granby, Oliver Moore noted, “putting side pieces to your bedsted and staining” for customer Samuel Clark. Bedrails, here called side pieces, were subject to damage and warping, leading to replacement.[24]

Many stained bedsteads received further surface treatment, varnish and polish being the most common. Josiah P. Wilder of New Ipswich, New Hampshire, recorded “Staining and varnishing Bedstead” in 1838 for Leonard Morse. Similar entries appear in the accounts of Nathaniel Knowlton of Maine, Silas Cheney of Connecticut, Frederick K. Coady of New York State, and John Sager of New Jersey. The japan that covered the stain on a high-post bedstead supplied to a customer by David Haven of Framingham, Massachusetts, likely was a varnish tinted with pigment. Whereas the polish placed on bedsteads in Rhode Island by Job Danforth Sr. and in Philadelphia by Thomas Affleck is not identified, the “oil” used by Silas Cheney on a stained bedstead may describe the material. Henry W. Miller’s record of “Staining & Gilding B Stead” in 1828 at Worcester, Massachusetts, is an uncommon written reference, although extant bedsteads indicate that gilded examples became increasingly popular in the second quarter of the nineteenth century, as grain-painted and stenciled surfaces also became prominent.[25]

Closely allied to references to paint and stain on furniture are those that specifically identify particular wood tones or wood patterns in painted, stained, or grained mediums. Mahogany, simulated in color or character, is the imitated wood named most frequently in records. The reddish brown color of this wood was replicated in paint, although actual recipes for mahogany-colored paint are rare or nonexistent. Nathaniel Whittock noted in his Painters’ and Glaziers’ Guide of 1827 that “brown of any shade or tint may be produced by the mixture of red, black, and yellow.” An alternative procedure was to select as pigment an ochre, or earth, such as terra de sienna or stone yellow, and subject it to roasting to convert the natural yellow color to a rich reddish brown.[26]

Customers of Daniel Rea Jr. of Boston, found mahogany color desirable for bedstead frames. Before the Revolution Rea painted two bedsteads mahogany color for Ellis Gray. A second client ordered a frame painted “Green and Mehogony Colour.” Among orders recorded after the war was one for “painting a short post Bedstead mehagony Colour” at a charge of 9s. ($1.50). Another customer engaged Rea for a job of “Painting a Bed press &c mehogony Colour.” It is unclear whether the “&c” described the bedstead frame within the press (cupboard) or architectural work within the room. Stephen Tracy noted another instance of this work at Lisbon, Connecticut, in 1809, when he recorded “painting a room & bed press.”[27]

Philadelphia craft accounts also document interest in bedsteads painted mahogany color. In 1785 David Evans noted, “Making a High Post Bedsted with Square feet & Bases” for a local merchant at a cost of £3.7.6 ($11.25). Evans charged another 12s. 6d. ($2.08) for “Painting D[itto] a mohogany Colour.” Several customers ordered a more expensive frame. A purchase made by John Davis in 1790 is described as a “mohogany foot Post Bedsted fluted, the other Part Painted.” The combination of a fine cabinet wood and a lesser species that would be painted in the same frame was relatively common. In recording a completed order for William Powell in 1795, Evans identified this type of work in still another way: “a high Post Bedsted Painted mohogany Colour with 2 feet Posts of mohogany.” Daniel Trotter, who frequently employed George Flake as a painter, also reported local demand for “Height Post” bedsteads painted “Moho Couller.” In the year 1792 alone, Flake painted sixteen high-post bedsteads with mahogany-colored paint in addition to six field bedsteads and three low-post frames. A trundle bedstead in mahogany-colored paint followed in 1793. Most of this work represented new construction, as opposed to frames deposited for refurbishing.[28]

In neighboring Chester County, where William Stewart possessed “One Mahogny Collard Bedsted” in 1811, Enos Thomas enjoyed a reasonable trade in bedsteads painted mahogany color during the 1790s and later. His mahogany-colored frames were made for either ropes or sacking bottoms to support the bedding. A high-post bedstead painted mahogany color could cost a moderate £1.10.0 ($5.00) or, in the case of a frame with a “head cornice,” a more substantial £2.5.0 ($7.50). A mahogany-painted field bedstead often cost £2.5.0, even when constructed of yellow poplar. “Short”-post frames in simulated mahogany fitted with a sacking bottom brought £1.10.0 ($5.00).[29]

Some craftsmen employed a stain to simulate mahogany color. Titus Preston of Wallingford, Connecticut, recorded an order in 1802 for “a field bedsted with O.G. teesters stained mahogany and fixed for lacing” a sacking bottom at a cost of £2.5.0 ($7.50). A quarter century earlier Andrew Cresman, a workman in the Philadelphia shop of David Evans, received a credit of 13s. ($2.17) for providing the cabinetmaker with a “mohogany Stained Bedsted” for resale. Throughout New England and the Middle Atlantic region other bedsteads in mahogany stain are unidentified in pattern among the substantial number of anonymous stained frames that appear in craftsmen’s accounts.[30]

An account book kept by Thomas Heston (also the firm of Heston and Gibbs), painter and glazier of Philadelphia, provides a glimpse at another direction taken by painters and ornamenters when creating a simulated mahogany finish on furniture. Orders for Heston’s client John Suplee recorded between 1804 and 1807 describe the work, although they raise questions of interpretation. Rather straightforward was Heston’s initial job of “Staining and gra[i]ning 1 pair high post Bedsteads mahoggany” in 1804 for 7s. 6d. ($1.25), the work followed by “Painting 1 pair high post Beadsteads mahogany” at 7s. 6d. in 1806 and “Graining 1 pair Beadsteads high post” in 1807 at a charge of 5s. (83¢). Clearly, the coatings on the surfaces of the bedsteads finished (or refinished) in 1804 and 1807 were imitative of the structural pattern of mahogany. Questioned is whether the grained coat of 1807 was placed over a ground of stain, as in 1804, or a base coat of paint. Also unclear is whether the bedstead painted mahogany in 1806 was grained or merely imitative of the color of mahogany. Current research supports the interpretation that before circa 1810 only furniture surfaces specifically identified as “grained” reproduced the surface pattern of the wood. Other grounds simply simulated the color of the wood. The picture changed during the 1810s, however, when grain-painted surfaces, often referred to as “imitations” of particular woods, began to come into their own. The grained finish of the low-post Pennsylvania bedstead with small pillow panels adjacent to the headboard illustrated in figure 10 appears to imitate mahogany, given the dark courses running through the pattern, especially on the outside of the footboard, and the simulated book-matched veneers on the face of the headboard.[31]

Craftsmen’s accounts name several other wood tones for bed frames executed in paint or stain, including cedar, maple, cherry, and oak. The earliest reference, dating to 1768, identifies a “Cedar Painted Bedstead” in each of two bedchambers in the mansion house of Samuel Moffatt, a merchant of Portsmouth, New Hampshire. One frame stood in a room on the third storey. The second cedar-painted frame was part of the furnishings of the “Green Chamber” on the second storey. This frame, probably the larger and more expensive of the two, was fitted with “Green Check Furniture,” that is, hangings woven in a checked pattern. Also listed were “2 Window Curtains of Ditto” and “6 Chairs Green Check Covering.” The inventory of sale items dated 1768 marks the year young Moffatt became a bankrupt and fled to the West Indies after a residence of five years in the house.[32]

What exactly was the surface appearance of Moffatt’s cedar-painted bedsteads? Were they grain-painted or merely coated in a color similar to that of cedar? Japanned furniture with simulated tortoiseshell grounds was in vogue in the early eighteenth century, as was imitative painting on interior walls and woodwork. Grain-painted imitation cedar panels distinguished a room from the George Goble House built circa 1725 at Lincoln, Massachusetts. A house advertised for sale at Boston in 1753 had several colorful rooms, one identified as “Painted...Cedar,” although whether grained or plain-painted is unclear. After midcentury, when interest in imitative surfaces on furniture declined, cedar-painted bedsteads made for an up-to-date household of the 1760s could merely have replicated the color of cedar. As lumber merchants, Moffatt and his father, John, were familiar with red cedar obtained in the West Indies. Recipes for reproducing this color in paint are rare, however. Hezekiah Reynolds, who published Directions for...Painting years later in 1812, named the pigments in “Red Cedar Color” as vermilion mixed with white lead as a ground, with “India red” for shading, or graining. Both vermilion and India[n] red, a ferric oxide earth, are bright red tinged with orange or yellow, producing a coral color. Whether Moffatt chose a brilliant hue for his bedsteads or a muted tone achieved with the use of white lead is unknown. Either color would have provided a striking contrast with the checked textiles of the “Green” bedchamber.[33]

References to bedsteads descr--ibed as maple usually identify frames made of that wood, the natural surfaces enhanced in color with stain or covered with paint. Pursuing the first option, Amos D. Allen of South Windham, Connecticut, filled an order in 1799 for Solomon Huntington described as “1 Bedsted high posts, screws, sack bot’m, Maple stained” priced at £2.8.0 ($8.00), and at Newport, Rhode Island, Job E. Townsend noted related work for Captain Caleb Gardner as “a Mapol Bedstid Staind and Poilish” for £1.7.0 ($4.50). Townsend also carried out different work for the Reverend Gardner Thurston, recorded as “a Mapol Bedstid and Painting” at a charge of £1.6.0 ($4.33). That frame may have been similar in type to the “highpost maple bedstead painted” purchased by Capt. Ephraim Kendall for £1.14.0 ($5.66) in 1786 from Daniel Ross at Ipswich, Massachusetts.[34]

Job E. Townsend also did business at Newport with another member of the Gardner family, Captain William Gardner, who purchased for £3.3.0 ($10.50) “a field Bedsted Cherry Posts, Scrues, Staind with Spirrits.” The high cost of this frame compared with those made of maple is, in part, a reflection of the greater esteem accorded cherry as a cabinet wood. The “Spirrits” used in staining the frame were spirits of wine (ethyl alcohol). One other wood, oak, is mentioned in documents. The reference dates to 1800, when Eph[raim?] Perkins of Mansfield, Connecticut, bespoke a “Press bedsted oak painted, sack bot’m” for 15s. ($2.50) from the shop of Amos D. Allen at South Windham, a location seven or eight miles distant. As clarity is not always a strong suit of period documents, it is not possible to know for certain whether Perkins’s new bed frame was made of oak and painted or made of another wood and painted to resemble the color of oak.[35]

A painted or stained finish unnamed directly in documents assembled for this study is one imitative of rosewood (see fig. 7). Presumably references to this finish lie buried in the large number of anonymous entries in craftsmen’s accounts of the early nineteenth century. Sheraton cited rosewood graining in relation to fancy chairs in 1803 in his Cabinet Dictionary. During the following decade this surface treatment began to gain popularity in the American seating market for Windsor and fancy chairs. By the late 1810s rosewood graining covered the surfaces of bedsteads. Perhaps Henry W. Miller’s staining and gilding a bedstead for J. T. Turner at Worcester, Massachusetts, in 1828 describes this type of ground, created, on occasion, with stain and frequently accompanied by gilding. Several authors published directions to “imitate Rosewood,” among them Jacob B. Moore of Concord, New Hampshire, whose Cabinet-Maker’s Guide of 1827 advised boiling logwood in water to produce a “very dark red” liquid, then adding a small amount of salt of tartar (potassium carbonate). Using this liquid “boiling hot,” a workman applied two or three coats to the wood to be stained, following it with a black stain, using a stiff, flat graining brush to imitate the character of rosewood. The graining might be streaked, waved, swirled, or splotched.[36]

As an alternative to stain, painters could imitate rosewood in oil paint, which Nathaniel Whittock described in his Guide of 1827 as “very easy”: “The ground is red, and should be painted twice over; the black grain is lamp black ground in dryers, with a little boiled oil; this must be put on the red with the flat brush. Knots or large veins may be taken out with the leather. When the whole is dry, let it be varnished with copal varnish.” An imitation rosewood finish with “knots,” such as Whittock describes, is illustrated in figure 11, a simple low-post design of early-nineteenth-century date. Simulated rosewood bedsteads from the 1830s and later are generally more ornamental in structure. Many qualify as French bedsteads, whose moderately high head- and footboards include arches, flat scrolls, and, on occasion, a turned and applied roll top (see fig. 7); vertical turnings are bold and complex. Gilded, stenciled, and banded ornament can provide further enrichment. On occasion grain-painted bedstead surfaces may be purely whimsical in nature, giving free rein to the imagination of the ornamenter.[37]

Brown paint on bedsteads encompassed several shades, identified by the terms “brown,” “stone,” “light color,” and “dark color.” The Oxford English Dictionary defines brown as “a composite color produced by a mixture of red, yellow, and black,” the proportions determining the exact tone. From 1791 until at least 1826, Abraham Overholt, a furniture maker of Bucks County, Pennsylvania, recorded the construction of many bedsteads painted brown. Most frames were of anonymous pattern, although two high-post frames and one low-post frame are identified. A number of frames were fitted with screws at the corner joints for easy assembly and disassembly. Overholt identified one of these as “a high posted bedstead with screws ... painted ... brown” and the cost as £1.17.6 ($6.25). Brown for bedsteads also was of consequence in neighboring Chester County, where Enos Thomas identified several brown-painted frames by type, including a trundle bedstead and two bedsteads with short posts, one “Painted brown for ropes” and another “Painted brown [for a] sacking bottom.”[38]

Stone, light color, and dark color were of brownish yellow hue and varied in shade from light to medium dark. Because paint was hand mixed, color could vary from batch to batch. The principal ingredients were yellow ochre and white lead in a binder, usually linseed oil. The Corporation of the City of New York engaged Josiah Furman, a local painter and glazier, for work in 1798 that included painting five bedsteads and other furniture. “Stone Colour” is prominent in Furman’s bill of work and materials submitted to the corporation. The city’s use of the bedsteads is not indicated, although they likely were part of the furnishings of a charitable facility overseen by the corporation. “Light color” and “dark color” were alternative terms for stone, the emphasis being on the depth of tone. Philemon Robbins of Hartford, Connecticut, a producer of French bedsteads during the mid-1830s, made a frame of this type described as “1 light colour bedstead with Roll on foot board.” The price at $6.25 was considerably higher than Robbins’s usual charge for a French frame, probably because of the presence of one or more special features. First was the identified roll on the footboard, jointed to the top of the tall panel as a full roll (see fig. 7) or as a half roll glued to the outside face of the rounded top edge. With a roll at the foot, some feature or ornamental shaping likely existed at the head. Special painted, stenciled, or gilded decoration also may have been present. Of similar date is Luke Houghton’s work in rural Barre, Massachusetts, where he recorded Daniel Bacon’s purchase of “1 Light Collar french bedsted” at $5.00 and “1 dark [Collar french bedsted]” at four dollars.[39]

Whereas the French bedstead at Philemon Robbins’s Hartford shop was an unusual request in light stone color, yellow-painted and red-painted French frames were in demand there. Prices varied from a low of $3.50 to as much as $5.75, the latter sum describing a “yellow french bedstead, foot board and wood Casters.” The headboard and footboard of some frames may have been paneled, as advertised in 1827 and 1828 by Jeremiah S. Short and Rhodes G. Allen at Providence, Rhode Island. In rural Bolton-Coventry, Connecticut, east of Hartford, Jeduthern Avery made yellow-painted French bedsteads with footboards. He described one frame as a “French bedstead 4 1/2 posts yellow,” identifying the height of the posts in feet. Well before the French bedstead took center stage, however, bedstead frames painted yellow appear to have been an occasional selection. In 1814 the furnishings of the household of Samuel Loomis, a cabinetmaker of Saybrook, contained a “yellow bedsted, Cord and underbed,” which may have shared chamber space with three yellow chairs listed with the seating furniture elsewhere in his probate inventory.[40]

White-painted seating furniture introduced during the 1790s likely stimulated interest in expanding the forms available in that color by the turn of the century, especially when gilt decoration was introduced to expensive fancy seating. A variety of decorated chamber furniture followed, including “White & gilt Bedsteads, with Cornices to match,” as advertised by Samuel Gridley at Boston. The white and gilt bedstead post illustrated in figure 12 is from a high-post frame with a history of descent in the family of Governor Joseph C. Yates of New York and his third wife, Ann Elizabeth Delancey. Although craftsmen’s records identify a variety of structural patterns, it is unlikely that all bedsteads painted white were gilded. In 1801 Amos Darlington Sr. made “a high Post Bedstead (white)” priced at £2.8.9 ($8.12) for a customer in Chester County, Pennsylvania, and at Bordentown, New Jersey, John Sager finished a “Field Bedsted Sacken Bottom Painted Wight” in 1805, charging £3.0.0 ($10.00). Eventually, white was an option for the French bedstead.[41]

A light ground, such as white, also was an optimal surface to receive hand-painted decoration, such as a vine spiraling up a bedpost. Although records are silent on the subject of specialized hand-painted ornament for bedsteads, aside from gilding, the accounts of Titus Preston of Wallingford, Connecticut, provide insight. A large order of furniture for Cornelius Cook in 1803 included six “dining chairs striped,” the decoration further described at the bottom of the bill: “the striping of the chairs to be a vine on the front of the bow & legs.” The multicolor vine spiraling up a post from a high-post bedstead (fig. 13) is comparable to that on the chair legs of Cook’s order and is a rare survival of a decorative technique of the federal period.[42]

Other bedstead colors may have found a modest market from time to time, including gray (fig. 14). In Margaret B. Schiffer’s study of Chester County inventories, gray occurs only twice among named bedstead colors. One was the “Lead Coulerd Bedstead” located in 1793 in the home of Philip Rapp. That reference is complimented by another from the accounts of Job E. Townsend of Newport, Rhode Island, who recorded “Pa[i]nting a bedstid Led Coller.” Gray paint, made of white lead colored with lampblack to the desired shade, more commonly served as a priming coat on raw wood, especially under the colors green and blue, rather than as a finish coat. Here the inscription “M.T. 1824” on the reverse of the headboard in the same gray as the finish coat identifies the date of painting and the initials of the painter, who also may have constructed the frame.[43]

Bedstead and Window Cornices

Bedstead and window cornices, furnishings of architectural inspiration, became prominent in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Initially associated with an opulent lifestyle, these embellishments eventually became relatively common. By 1803 Sheraton noted that “in cabinet work, cornices are now made much lighter then formerly.” A cornice is aptly described as a wooden box, or holder, from which valences and curtains are hung in plain or festooned patterns. In period documents cornish is a frequently seen alternative term. Paint was the popular surface coating for cornices, although several other finishes are noted: blacking, coloring, staining, and japanning.[44]

Solomon Fussell, a Philadelphia craftsman working in the 1740s, identified “blacking” and “Coulering” as processes for coating cornice surfaces. In “blacking and varnishing the cornish of a bead tester” for his client Thomas Sugar, Fussell probably first employed a paste or liquid to achieve the dark color. When “Coulering [and] Varnishing [a] Bead cornish” for Benjamin Franklin, the artisan likely used color in size, a glue-like material. The cost was 1s. 6d. (equal to 25¢ in later decimal currency), similar to that for blacking. Coloring remained an inexpensive, occasional choice for cornice and bedstead finishes into the late eighteenth century. Staining a cornice was more usual. As noted, David Evans of Philadelphia made and stained a bedstead and cornice for Jonathan Zane late in the Revolution, and following the war he shipped a stained high-post bedstead and cornice to Virginia as venture cargo. Japanned cornices entered the marketplace somewhat later. When the partners William Haydon and William H. Stewart of Philadelphia were listed as “fancy japanned chair and cornice makers” in an 1810 city directory, this finish, of limited early eighteenth-century use, was achieving a revival. Sheraton commented earlier on “Japanning Window Cornices” in his Cabinet Dictionary, advising workmen to prepare the ground with at least “one lay of common whiting and size” before adding the “finishing colours” and any ornament required.[45]

Of the materials used for finishing cornices, paint was the common choice. An unusual look behind the scenes in window-cornice production is found in a probate record of 1832 for the New York estate of Edward A. Ball, a manufacturer of window blinds and accessories. The inventory of shop materials provides insight into fabrication processes and pricing. Fifty-two cornices valued at 17¢ apiece were “made but not painted.” Another 302 frames, primed “in Lead colour,” were given a value of 18¢ apiece. Cornices with one coat of finish paint were 20¢ apiece. The five-cent difference between cornices with one coat of paint and finished frames at 25¢ suggests the latter received both a second coat of paint and a protective coat of varnish, and probably some basic ornament. A large number of “Brackets,” some “not painted” at 2 1/2¢ apiece and others in “Lead Colour” at 3¢ apiece, presumably were used with the cornices. Appraisers located “10 Cornice patterns” and production materials, including “277 feet pine boards,” “200 lb common Lead col[ore]d paint,” “4 Keg white Lead” weighing one hundred pounds, ten gallons of turpentine, and one-half barrel of varnish estimated at fifteen gallons. Some notice was given to equipment. A “machine to cut cornices” was a simple, basic device, given its low valuation at 1s. (12 1/2¢ in New York decimal currency). Two painting horses supported the cornices for surface finishing. Of the shop’s two paint mills for grinding pigment, the one valued at $40.00 probably employed dressed millstones. A gray horse “old & Blind” was the power source. Other shop mills ground chalk for whiting.[46]

The basic window cornice was a rectangular box finished in a plain color and frequently made en suite with a cornice for a bedstead. Structural variations in the window cornice could include a frame of “Broad” dimension, as found in the estate of Edward A. Ball. The Philadelphia cabinetmaker Daniel Trotter described other options in filling an order for a local customer about 1796: “6 Window Cornices, 2 Swelled, 4 Scallop & painted” (fig. 15). James Martin identified alternative language for the “Swelled” cornice a few years later, when he billed William Taylor at Baltimore for “3 Bow Window Cornices.” Acquired at the same time as the bowed window cornices were a “Bed cornice” and a “Mahog’y Bedstead.” Other information indicates that all the cornices were painted but suggests the window and bedstead cornices were not used together.[47]

In contrast to the amount of information in craftsmen’s records identifying finish colors on bedsteads, data illuminating ground colors on cornices are modest. White was a popular choice in the federal period, likely because it provided a light, neutral ground for decoration. Green and blue are the other named ground colors in the written records at hand. David Alling recorded on June 3, 1815, that his ornamenter Moses Lyon painted a “Sett of Green Bed Cornices” during a stint in the chairmaker’s Newark, New Jersey, shop. Earlier, in 1796, George Davidson, a Boston painter, billed the firm of Stone and Alexander for “Painting Mr Stones Cornices Blue” at a charge of 7s. 6d. ($1.25). Blue also was the choice of Elijah Warner, a cabinetmaker of Lexington, Kentucky, for a “High post Bedstead Blue Cornise,” itemized in an 1829 inventory of his household furnishings.[48]

Among basic embellishments used to decorate cornice surfaces, craftsmen’s records identify borders and edging, probably interchangeable terms (see fig. 15). At Boston in 1793 Daniel Rea Jr. recorded “Paint’g a sett Bed Cornices plain white with Green Edge, new ones,” the charge 9s. ($1.50). In another account he recorded “Painting a sett Bed Cornices Plain white & Green Border.” Dictionaries describe a border as “an edge,” making the two words synonymous. Further insight into customer choices of edging (borders) was recorded by George Davidson, a contemporary of Rea’s at Boston, who had business with the cabinetmakers Stone and Alexander between 1795 and 1797. The firm sought Davidson’s services for “Painting a Sett of Cornices Edgd with Red” and for painting a blue and a green set, both “edgd with gold.” Of variant form were cornices recorded by Rea in 1791, when he painted “a sett Bed Cornices double Escalop’d Edges” (see fig. 15). At Baltimore John and Hugh Finlay produced more lavish bedstead and window cornices with “Painted Fruit, Scroll, and Flower Borders of entire new patterns.” Both fruit and floral motifs were widely popular (fig. 16).[49]

Most American furniture craftsmen in urban centers offered gold ornament for cornices (fig. 17) following the resurgence of gilded surfaces in the late eighteenth century under the influence of British designers Robert Adam and Thomas Sheraton. The cost of “Painting five Window Cornices and gilting the same” after construction cost John Coffin Jones 15s. ($2.50) apiece in 1795 at the Boston shop of George Davidson. In 1811, when Thomas Boynton painted and gilded “a set of cornices” for local cabinetmakers Bryant and Loud, Samuel Gridley had already advertised “White and Gilt Bedsteads, with Cornices to match” in the Columbian Centinel. At neighboring Roxbury John Doggett also pursued a brisk business in painting and gilding cornices supplemented by the sale of gold size and books of gold leaf to other craftsmen. North of Boston, Richard Austin of Salem provided a cost comparison for painted versus painted and gilded work, when recording a job of 1805–1806 for cabinetmaker Jacob Sanderson. A set of cornices in paint (probably two items) cost $2.00; a painted and gilded set was $4.50. Ever mindful of the Boston furniture market, ornamental painters at Portsmouth, New Hampshire, including George Dame and Henry Bufford, also offered local customers painted, gilded, and varnished window and bedstead cornices.[50]

William Palmer had been a fancy chair and cornice maker in New York for more than a decade in 1803, when he sold George Brewerton “2 window Cornices white and Gold.” Brewerton’s purchase possibly represented one of the “newest pattern Cornices” Palmer had advertised the previous year. Palmer also had a brief business relationship with young Newark, New Jersey, chairmaker David Alling, who by 1815 employed Moses Lyon to paint and decorate furniture, including “Gild’g &c 2 Cornices” for a Mrs. Gobles. Fenwick Lyell, another New Jersey craftsman, worked in New York during the late 1790s before moving to Middletown, where he made “a Set Bed Cornishes Painted & Gilded” in 1806 for £3.8.0 ($8.50 in New York currency). New York City influence extended up the Hudson River to Albany, home to artist Ezra Ames, who supplemented work on canvas with ornamental work, including “painting & Gilding 4 fancy window Cornichs” for the Gansevoort family.[51]

Members of the furniture-making community at Philadelphia also offered furnishings with gilded accents. In 1801 David Evans recorded “making 2 Cornices Painted & Gilt.” Books of gold and silver leaf and painting supplies were available at shops such as that kept in Front Street by John McElwee, painter and glazier. At Baltimore Smith and Company stocked a supply of gold leaf for the convenience of local craftsmen, and John and Hugh Finlay offered cornices “of various colors, ornamented and gilt in the most fanciful manner,” some with gilded moldings and composition “Beads, Twists, Nelson Balls, &c.” (fig. 18). Large, marble-size composition Nelson balls were a frequent component of the looking glass, and beads and twists also appear on picture frames.[52]

Whereas craft documents provide few insights into the nature, subject, and variety of cornice ornament, extant period work identifies basic processes and provides insight into decorative range. Among processes are ornamental painting and stenciling (fig. 19), paneling, carving and shaping, stamped-metal, and composition work. The vocabulary of decoration is broad. To banding and gilding can be added painted or stenciled floral and fruit subjects; bird and animal forms; scrollwork; landscape, waterscape, and imaginary views; mythological and neoclassical subjects (see fig. 17); trophies, comprising agricultural or military implements; and imitative surfaces.

Craftsmen rarely commented on cornice decoration in their records, unless it was of a special nature or costly. David Alling of Newark, New Jersey, in recording the work of his ornamenter Moses Lyon in 1815, identified a set of bedstead cornices, probably painted green, decorated with “Oak Wreaths,” although it is unclear whether the ornament was gilded or “bronzed” (stenciled). More elaborate was a “Bed Cornish” made by Jacob Sanderson at Salem, Massachusetts, in March 1807 for merchant Aaron Waite at a base price of $4.00, with an additional $4.25 for “Painting & Guilding said Cornish.” Work did not end there, however, as three months later Waite paid Sanderson $3.50 “for 3 Carvd sheeves [of] wheete and guilding the same,” bringing the total of his handsome bedstead cornice to $11.75 (fig. 20). Sanderson engaged Samuel McIntire to do the carving.[53]

As impressive as it was, Aaron Waite’s bedstead cornice appears to have paled by comparison with purchases made in 1808 and 1809 by Mrs. Elizabeth Derby West, daughter of Salem merchant Elias Hasket Derby (died 1799), for Oak Hill, the mansion house on her farm nearby at South Danvers (now Peabody). William Lemon, upholsterer, provided a bedstead cornice in December 1808, which he transferred to the Roxbury shop of John Doggett for “Gilding Bed Cornise, Bows, Darts, Quivar, arrows, &c,” Doggett’s charge adding $16.00 to the basic construction cost. The cornice may have been for use on a bedstead listed earlier in the year on a Vose and Coates bill of September 15 to Mrs. West, although the bedstead was not priced and the item was lined through. The bow-and-arrow motif apparently was popular in Salem, as several cornices with this ornament survive, and there is record in 1812 of local craftsman Joseph True carving at least two “Bow & arrow” cornices for cabinetmaker Nehemiah Adams.[54]

Following her business with William Lemon, Mrs. West dealt directly with Doggett in March 1809, when ordering “1 Bed [cornice] and 4 window cornises 41 feet at 15s.,” or $2.50 the foot, the total cost $102.50. Presumably, Doggett’s charge included making, painting, and decorating the cornices. If each window cornice measured 4 1/2 feet (including wall returns), the bedstead cornice measured a sizable 23 feet. At $2.50 per foot, the bedstead cornice would have cost Mrs. West $57.50 and each window cornice $11.25. Doggett provided no further information in his accounts about this costly suite, which likely made substantial use of gilding.[55]

Baltimore craftsmen Hand and Barber alluded to another decorative technique when they painted and gilded three circular (bowed) “Composition cornices” made by John Martin for William Taylor. These window cornices, priced at $5.62 apiece, perhaps were ornamented in part with beads, twists, and Nelson balls, like those advertised by the Finlay brothers. Shedding more light on this work are the records of John Doggett. “Composition beeds” (and probably twists) were available for purchase at 3¢ the foot at his Roxbury, Massachusetts, shop. “Large balls” in composition were priced at $6.00 or $7.00 the gross, although they were available in smaller quantities. Alternatively, Taylor’s cornices may have been ornamented with classically inspired composition medallions or tablets. Mary Rawlins of Baltimore advertised “Composition Work” consisting, in part, of “Ornaments for Doors, Windows, ... Wood Cornices, and particularly Chimney-Pieces” (mantelpieces) in the late eighteenth century, although the principal focus of her product was architectural.[56]

In 1794 Daniel Trotter of Philadelphia paid John Gardner the sum of £5.5.0 ($17.50) for “painting & Ornamenting 6 Cornishes.” As the date is early for stencil work and gilding is not identified, hand-painted work appears indicated, although few craft records illuminate hand-painted ornament on cornices. Sheraton described “Window and bed cornices” briefly in his Cabinet Dictionary as “generally ornamented with leaves and some kind of trophy, or flowers,” noting that the decoration should be “touched” with highlights and some strong shading. The fabric puffs in figure 21 have been detailed to exhibit a three-dimensional quality achieved with highlights and shading. Sheraton further advised finishing the work with two coats of hard white varnish.[57]

Cornices and textiles shared a close relationship in the period under study. Just how close at times is demonstrated in several entries in the accounts of two ornamental painters of Boston, Daniel Rea Jr. and George Davidson. In 1793 John Miller approached Rea with a somewhat unusual, though not unknown, request for “Painting a sett of Bed Cornices in Imitation of the Copperplate,” for which he paid £1.4.0 ($4.00), a charge reflecting only the cost of ornamentation. Copperplate refers to English cottons printed with scenic and floral patterns using large copperplates. Of the several colors available, red and blue appear to have been the most popular. The same year Miller made his purchase from Rea, the local firm of Hayward and Blake engaged Davidson to paint “a sett of Bed & Window Cornices Resembling the Coperplate.” Larger than Miller’s order, the partners’ purchase cost them $9.00. Two years later the firm again hired Davidson, this time to paint “a Sett of window Cornices in Imitation of Calico,” a general textile term for cotton cloth block-printed or plate-printed with a figured pattern. The partners paid $5.00 for the work.[58]

The limited practice of painting cornices in imitation of cloth likely originated in a costly decorative scheme of earlier date in which cornices were covered in actual cloth. An instance of this is an order placed in 1725 by Thomas Fitch of Boston with a London factor to obtain a partial set of bedstead hangings, including a cornice covered with camlet, to use as a pattern in his own upholstery work. Camlets were woven of wool or a wool mixture and available in patterns ranging from stripes to figures. Several decades later, in 1759, George Washington looked to London for an extensive suite of hangings that included “a Neat cut [shaped] Cornish” for a bedstead accompanied by similar cornices for two windows. All the cornices were covered in “Chintz Blew Plate Cotton furniture,” a woven cloth available in a variety of printed patterns.[59]

At least two examples of bedstead cornices covered in figured cloth still exist. A fragment of a shaped and molded cornice from the Glen-Sanders family of Scotia, New York, near Schenectady, is covered with a late-eighteenth-century English red-and-white copperplate-printed cotton in a figured pattern (fig. 22). A complete cornice with elaborately shaped edges and pierced openings made for a member of the Porter-Belden family of Wethersfield, Connecticut, at midcentury is covered with a blue and white, resist-dyed cotton in a bold floral pattern. In households where neither cloth-covered nor painted imitations of figured cloth-covered cornices were affordable or the area to be furnished was of secondary importance, another option was available. The estate of Robert Marvin, probated at New York City in 1812, reveals that he owned “3 Paperd Cornices” valued at a modest 94¢. To preserve cornices covered in printed paper, William Palmer of New York proposed in 1796 to “varnish ... paper cornices ... so as to heighten and preserve the spirit and brightness of the colours from all kind of dirt” and to permit them to “be washed with effect.”[60]

Whereas this has been a relatively brief look at bedstead and cornice options available to American consumers in the late colonial and federal periods, it demonstrates the considerable variety of coated grounds and ornament from which customers could choose. Consumers were limited only by the size of their pocketbook and the limits of their imagination.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For assistance in interpreting technical terms and/or locating and acquiring suitable illustrations, the author thanks Christine Bertoni, Deanna Bonner-Ganter, Donna Braden, Nicole Chalfant, Tara Chicirda, Jeanne Gamble, John Hart, Thom Hindle, Christie Jackson, Brock Jobe, Rob Karosis, Alexandra Kirtley, Angelika Kuettner, Dean Lahikainen, Gregory Landrey, Joshua Lane, Penny Leveritt, Megan MacNeil, Marianne Martin, Austin T. Miller American Antiques, Christina Milliman, Robert D. Mussey Jr., Susan Newton, Jane and Richard Nylander, Jim Orr, Milicia Patil, Pook and Pook, Inc., Jeannette Robichaud, Paul Rubenson, Charles Sable, James Singewald, Michael Somple, and Christopher Swan.

Nancy Goyne Evans, “Documentary Evidence of Painted Seating Furniture: Late Colonial and Federal Periods,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2011), pp. 204–85; Nathaniel Whittock, Decorative Painters’ and Glaziers’ Guide (London: Isaac Taylor Hinton, 1827), p. 8. The author is indebted to Gregory Landrey of the Winterthur Museum for his insights on the visual differences between paints, washes, and stains.

Abner Taylor Account Book, Lee, Massachusetts, 1806–1832, account with Asahel Foot, July 29, 1815, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Winterthur Museum Library, Winterthur, Delaware (hereafter DCM); Daniel Ross Account Book, Ipswich, Massachusetts, 1781–1804, account with Amos Jones, February 12, 1802, Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts (hereafter PEM); Samuel Haly, “Painter stainer,” household goods sold at public vendue, Boston Gazette, January 30, 1750, as quoted in The Arts and Crafts in New England, 1704–1775, compiled by George Francis Dow (Topsfield, Mass.: Wayside Press, 1927), p. 112.

Hurst and Lybrand Advertisement, Lancaster (Pennsylvania) Journal (Pennsylvania), January 24, 1823; Margaret B. Schiffer, Chester County, Pennsylvania, Inventories, 1684–1850 (Exton, Pa.: Schiffer Publishing, 1974), pp. 130–31; William Chappel Ledger, Danbury, Connecticut, 1793–ca. 1816, accounts with Clark Peck, November 2, 1798, and Eliakim Peck, November 6, 1801, and December 31, 1793, DCM; George Haughton Advertisement, Pennsylvania Journal (Philadelphia), March 2, 1777, as quoted in The Arts and Crafts in Philadelphia, Maryland, and South Carolina, 1721–1785, compiled by Alfred Coxe Prime (Philadelphia: Walpole Society, 1929), pp. 170–71.

Thomas Sheraton, The Cabinet Dictionary, 2 vols. (1803; reprint, New York: Praeger Publishers, 1972), 2: 213–14; Peter M. Kenny et al., Honoré Lannuier: Cabinetmaker from Paris (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998), pp. 86, 88, 90, 102, 122, 130.

Richard Lechmere Estate Inventory, Boston, 1776, Massachusetts State Archives, Boston, photostat DCM; Daniel Rea Jr., Daybook, Boston, 1789–1793, accounts with Dr. Bulfinch, July 13, 1790, and Stephen Codman, July 25, 1793, and Ledger, Boston, 1764–1799, accounts with John Bright, September 20 and November 30, 1792, and “Rogers, Joyner,” December 28, 1765 (varnish), Baker Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts (hereafter BL); Chappel Ledger; Cabinetmakers’ Price List (Hartford, Conn., 1792), as reproduced in Gerald W. R. Ward and William N. Hosley Jr., eds., The Great River: Art and Society of the Connecticut Valley, 1635–1820 (Hartford, Conn.: Wadsworth Atheneum, 1985), pp. 471–73; William H. Reed Account Book, Hampden, Maine, 1803–1848, DCM; Silas E. Cheney Daybooks, Litchfield, Connecticut, 1799–1821, Litchfield Historical Society, Litchfield, Connecticut; Stephen Tracy Ledger, Lisbon, Connecticut, and Plainfield, New Hampshire, 1804–ca. 1826, privately owned; [Robert Dossie], Handmaid to the Arts, 2nd ed., 2 vols. (London: J. Nourse, 1764), 1: 12–13; Sheraton, Dictionary, 2: 424.

Jacob Brouwer Bill to Nicholas Low, New York, July 12, 1797, Miscellaneous Legal Papers and Accounts, Nicholas Low Collection, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. (hereafter LC); Plunket Fleeson Advertisement, Pennsylvania Gazette (Philadelphia), September 23, 1742, as quoted in Prime, Arts and Crafts, 1721–1785, pp. 201–2; John Hockaday Bill to St. George Tucker, Williamsburg, Virginia, April 13, 1811, St. George Tucker Papers, Tucker-Coleman Collection, Swem Library, College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia.

William Walton Estate Inventory, New York, 1806, DCM; Fenwick Lyell Account Book, Middletown, New Jersey, 1800–1813, accounts with John Hilliker, June 11 and December 6, 1807, and Henry A. Coster, June 28, 1808, Monmouth County Historical Association, Freehold, New Jersey.

Eden Haydock Account and Bill to John Cadwalader Jr., Philadelphia, 1771–73, item for May 6, 1773, General John Cadwalader Papers, 1770–1786, Cadwalader Collection, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia (hereafter HSP); David Evans Daybook, Philadelphia, 1784–1806, accounts with Balthazar Woncher, April 3, 1790, William Lawrence, May 10, 1785, and “Limeburner,” May 1785, HSP.

Daniel Trotter Estate in Account with John Gardner, 1787–1800, and George Flake Account and Bill to Daniel Trotter, Philadelphia, 1791–1793, Daniel Trotter Family Papers, ca. 1780–1803, DCM.

Abraham Overholt Account Book, Plumstead Township, Bucks County, Pennsylvania, 1790–1833, accounts with Andres Wiesler, February 13, 1795, and Elisabeth Rorian, 1795, as published in The Accounts of Two Pennsylvania German Furniture Makers: Abraham Overholt, Bucks County, 1790–1833, and Peter Ranck, Lebanon Cunty, 1794–1817, translated and edited by Alan G. Keyser, Larry M. Neff, and Frederick S. Weiser, Sources and Documents of the Pennsylvania Germans 3 (Breinigsville, Pa.: Pennsylvania German Society, 1978), p. 9; Schiffer, Chester County Inventories, pp. 99, 146.

Stevens Thomson Mason Estate Inventory, Loudoun County, Virginia, 1803, Loudoun County Probate Records, photostat DCM.

John Hoskins Estate Inventory, Chester, Pennsylvania, 1716, as transcribed in Schiffer, Chester County Inventories, pp. 298–301, esp. p. 300; for Prussian blue discussion, see Richard M. Candee, “House Paints in Colonial America: Their Materials, Manufacture, and Application ...,” Color Engineering (March/April 1967): 36–37.