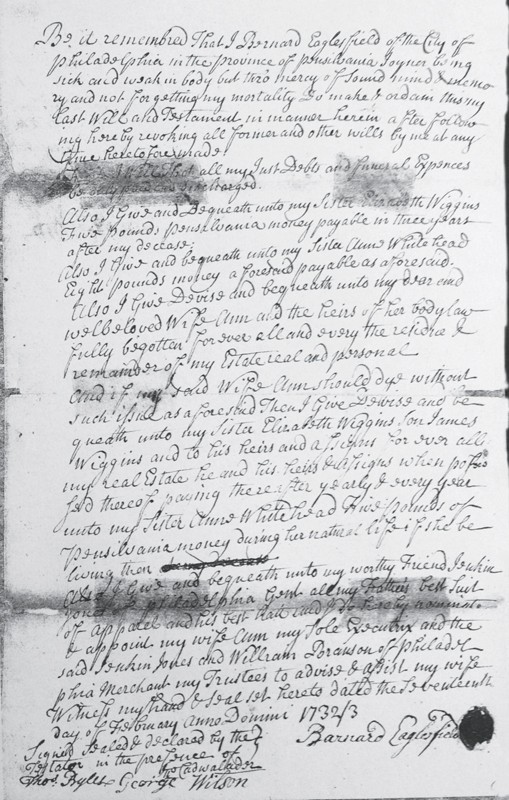

Will of Barnard Eaglesfield, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, dated February 17, 1732/1733 and probated April 13, 1733. (Courtesy, Philadelphia Register of Wills.)

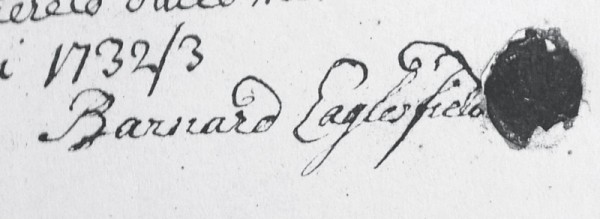

Signature of Barnard Eaglesfield on his will, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, dated February 17, 1732/1733 and probated April 13, 1733. (Courtesy, Philadelphia Register of Wills.)

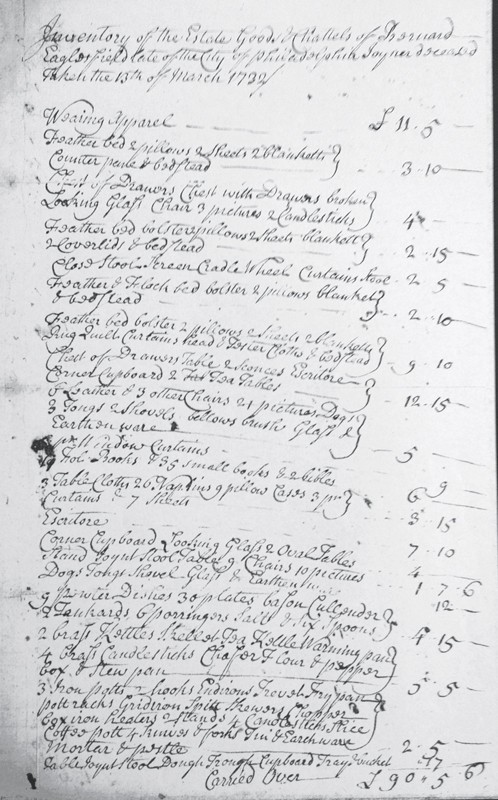

First page of the probate inventory of Barnard Eaglesfield, dated March 13, 1732[/1733]. (Courtesy, Philadelphia Register of Wills.)

Edward Evans, scrutoire, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1707. Walnut with Atlantic white cedar and white pine. H. 66 1/2", W. 44 1/2", D. 19 7/8". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.) The scrutoire is stamped “Edward Evans 1707” on the inside bottom drawer centered above the open well in the upper section. It is the earliest dated piece of Philadelphia furniture marked with a maker’s name.

Scrutoire, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1715–1730. Walnut with Atlantic white cedar and hard pine. H. 64", W. 32", D. 20". (Courtesy, Dietrich American Foundation.) This scrutoire is illustrated open with the fall missing in William McPherson Hornor Jr., Blue Book Philadelphia Furniture (Philadelphia: privately printed, 1935), p. 15, pl. 1.

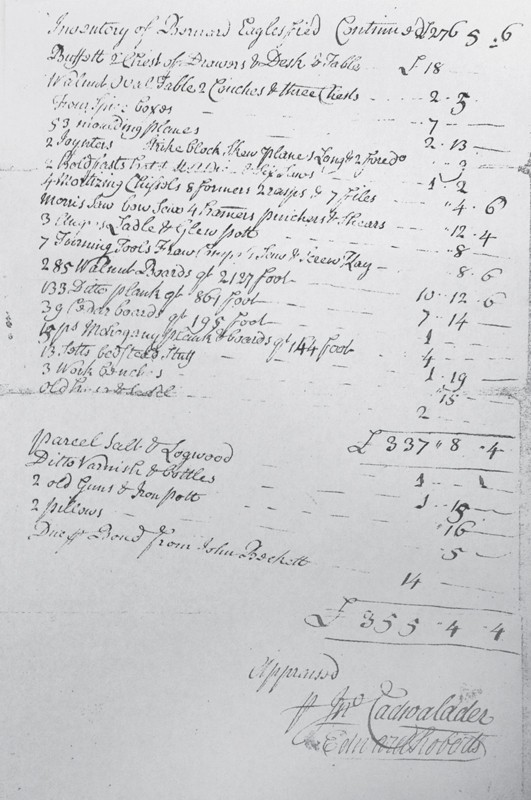

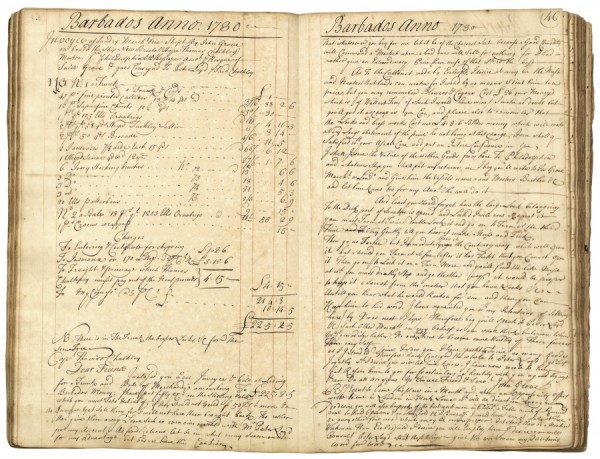

Last page of the probate inventory of Barnard Eaglesfield, dated March 13, 1732[/1733], listing 15 pieces of furniture; tools; varnish; planks and boards of mahogany, walnut, and cedar; and three work benches. (Courtesy, Philadelphia Register of Wills.)

Transcription of a 1730 letter of instructions from John Grove to Thomas Chalkley in the Thomas Chalkley Account and Letter Book, 1729–1732, p. 46. (Courtesy, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.)

Henry Popple, A Map of the British Empire in America with the French and Spanish settlements adjacent thereto, [1733] ca. 1735. Engraving on paper. H. 15", W. 20 1/2". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Desk-and-bookcase, probably Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1715–1730. Walnut with tulip poplar and walnut. H. 90", W. 40", D. 22 3/4". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art; gift of Mrs. John Wintersteen.)

Oval table, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1715–1730. Black walnut with Atlantic white cedar. H. 28 3/4", D. (top) 59 3/4", W. (open) 73". (Courtesy, Dietrich American Foundation.)

Significant new information on early Philadelphia furniture makers and their work has been published since the Philadelphia Museum of Art opened its seminal exhibition Worldly Goods: The Arts of Early Pennsylvania, 1680–1758 in 1999. We now know of additional pieces signed by or attributable to members of the Claypoole dynasty—Joseph (1677–1744), James (1720–1796), George (1706–1793), and Josiah (1717–1757)—and that joiner John Head (1688–1754; from 1717 in Philadelphia) was one of the city’s most prolific and innovative craftsmen. Insights into Head’s work originated with the author’s discovery of that cabinetmaker’s account book, which resulted in several publications and attributions of more than forty pieces of case furniture to Head’s shop. The author’s present discovery of unpublished manuscripts pertaining to Philadelphia joiner Barnard Eaglesfield (d. 1732) reveals that his stature and influence as a furniture maker may have been comparable to that of Head and the Claypooles.[1]

Previously, scant attention had been paid to Eaglesfield because no one had attributed objects to him or cited primary sources that document him as a furniture maker. A nineteenth-century genealogist cited a 1726 charge from a “Barnard Eaglesfield” to the estate of Philadelphia merchant Hugh Lowden for a coffin; however, coffins were produced by a variety of woodworkers including house joiners, carpenters, and cabinetmakers, so furniture production cannot be inferred from this reference. Similarly, William McPherson Hornor Jr.’s Blue Book Philadelphia Furniture (1935) identified Eaglesfield as a woodworker but failed to demonstrate that he was a furniture maker: “Bernard Eaglesfield, joiner, worked for Hugh Loudon, 1722–23; died 1732.” Because Hornor did not cite his sources, this and much other information on Eaglesfield in the Blue Book could not be verified. Moreover, not every joiner made furniture. Hornor’s reference to a “Buffett” (corner cupboard) purportedly made by Eaglesfield in 1735 was problematical since Eaglesfield died in 1732. Quoting from an unidentified “list,” Hornor stated that Eaglesfield had “13 Setts bedstead stuff,” “73 yds Calico in remnants,” and a “stock” of lumber. The last was especially tantalizing as it included walnut, mahogany, and cedar—all woods then common for making furniture in Philadelphia and readily available from lumber merchants. But without a reference to tools with which to fashion it, this was no confirmation that Eaglesfield was a maker rather than a merchant. In contrast, Joseph Claypoole’s advertisements and John Head’s account book, which also refer to quantities of materials, clearly relate that each is making furniture.[2]

Eaglesfield’s name came to this author’s attention when researching John Head’s account book. On June 13, 1724, Head charged “Barni Eagelsfield” for twenty brass knobs. The following day, Head credited him for 9 1/2 feet of “mohoganey plank” and made separate payments to Eaglesfield and his wife for the difference in cost, but there was no indication that Eaglesfield was using the hardware or wood to make furniture. “Barnard Eaglesfield” also appears in a ledger maintained by Philadelphia merchant James Logan (1674–1751). A 1725 credit entry recorded Eaglesfield’s payment of £180 in “cash,” and a debit was entered the following year for his purchase of two dozen looking glasses—a commodity Logan imported in large quantities. In an era when many transactions were conducted by barter, as ready money was being siphoned abroad to pay for finished goods, £180 was a significant cash sum. Although informative, the transactions in the Head account book and Logan ledger still were insufficient to show that Eaglesfield was a furniture maker. Indeed, his sale of mahogany to Head and his purchase of looking glasses from Logan lent greater weight to his being a merchant rather than a working craftsman.[3]

The manuscripts that are the subject of this essay reveal that Eaglesfield was a prominent and prosperous furniture maker who occupied premises on the busiest street in Philadelphia’s commercial center and had commissions for large and complex forms at premium prices; ties to more than one hundred members of Philadelphia’s commercial, political, and religious elite; and patrons as far away as the West Indies. Eaglesfield’s probate records are also the most extensive, detailed, and comprehensive found to date for any Philadelphia furniture maker. At his death, Eaglesfield owned at least seventy-two pieces of furniture—some of which were clearly stock-in-trade or unfinished commissioned work—and large quantities of materials, hardware, and tools. Previous researchers may have overlooked Eaglesfield because his prominence was not suspected and his probate records are not listed in the standard index used to locate such records in the City of Philadelphia archives.[4]

At first glance, Eaglesfield’s simple, one-page will appears to provide little information other than documenting his signature and describing him as a “Joyner” (figs. 1, 2). He left his estate to his wife, Ann, with the provision that, if she died without lawful issue, the estate would pass to his sister, her son, and his heirs. As no children are named, Barnard and Ann may have had none. When Eaglefield’s will is considered in a broader historical context, it sheds light on his business and personal relations, particularly with those of the Baptist faith. Barnard left “all my Father’s best Suit of Apparel, & his best hatt” to his trustee, “Jenkin Jones [1696–1760] of Philad: Gent[leman].” In 1726 Jones became a minister at the Baptist church in Philadelphia, succeeding George Eaglesfield (d. 1730). Logan’s ledger, in an account for “George Eglesfield,” records cash payments partly coming “from his Son,” between 1720 and 1724, and, in Barnard’s account, £10 in cash paid for “balancing his father’s Acco[unt]” in 1724. No other Eaglesfield or variant of that name appears in the ledger. Given that Jones and George Eaglesfield served the same congregation and that Barnard’s estate listed “6 folio Book[s] belonging to ye Baptist meeting,” the elder Eaglesfield appears to have been the cabinetmaker’s father.[5]

The other trustee of Barnard’s estate was also a Baptist, “William Branson [1684–1760] of Philad: Merch[an]t.” A convert from Quakerism, Branson transitioned from joiner to shopkeeper to one of America’s first iron industrialists. Branson may have supplied Eaglesfield with furniture hardware as he later did John Head. Barnard witnessed the will of another Philadelphia Baptist, James Tuthill, a gentleman. A provision in that document manumitted a “Negro Man Sharper,” who would later be paid for helping to bury Barnard. Barnard himself was probably a Baptist as, in 1724, Ann Eaglesfield was disowned by the local Quaker meeting for marrying outside the faith.[6]

In addition to his will, Eaglesfield’s probate records include a one-page affirmation by witnesses Thomas Biles, George Wilson, and John Cadwalader, dated March 12, 1732[/1733]; a five-page inventory of “Goods & Chattels” in his house and shop (including furniture, materials, hardware, and tools totaling £355.4.4) appraised by Cadwalader and Edward Roberts, and dated May 15, 1733; and an eight-page accounting listing more than a hundred creditors and debtors (totaling £681.18.11 1/2) signed by Thomas Hine and dated July 18, 1735. A decade later, Wilson made furniture for Philadelphia merchant Nathaniel Allen. The fact that Wilson was a joiner and witness to Eaglesfield’s will suggests that the two may have done business and possibly worked together.[7]

The first page of Eaglesfield’s inventory appears to list household objects, as it starts with a valuation of his “Wearing Apparel” and ends with smaller domestic wares (fig. 3). In between are entries for at least forty-eight pieces of furniture (of which thirty-eight are case pieces), evidence of his prosperity but also illustrative of the range of his output, as many of those objects were probably made in his shop:

Feather bed & pillows 2 Sheets 2 blanketts Counter pane & bedstead

£3.10

Chest of Drawers Chest with Drawers broken Looking Glass Chair 3 pictures 2 Candlesticks

£4

Feather bed bolster 2 pillows 2 sheets blanket 2 Coverlids & bedstead

£2.15

Close Stool Screen Cradle Wheel Curtains Stool

£2.5

Feather & Flock bed bolster 2 pillows blanket & bedstead

£2.10

Feather bed bolster 2 pillows 2 Sheets 2 blanketts Rug Quilt Curtains head & Tester Cloths & bedstead

£9.10

Chest of Drawers Table 2 Sconces Escritore Corner cupboard 2 Tea Tables

£12.15

6 Leather & 3 other Chairs 24 Pictures Dogs 3 Tongs 2 Shovels bellows brush Glass & Earthenware

£5

Escritore

£7.10

Corner Cupboard Looking Glass 2 Oval Tables

£4.10

Stand Joynt Stool Table 9 Chairs 10 pictures

£1.7.6

Table Joynt Stool Dough Trough Cupboard Tray & bucket

17s

Remarkably, Eaglesfield owned two “escritores,” a double-case form with a fall front also referred to contemporaneously as “scrutoire,” “scrutore,” “scrudore,” “screetore,” and “scriptor.” With its two sections, fall front, and varied drawer sizes, the scrutoire was one of the most elaborate and costly furniture pieces produced in colonial America and required an accomplished craftsman to make it. As no furniture by Eaglesfield has yet been identified, one or both escritores may have looked like an example bearing the mark of Philadelphia joiner Edward Evans (1679–1754) and the date 1707 (fig. 4), which has a lockable fall front and no exterior doors; or possibly resembled a scrutoire that once had a fall-front writing surface originally concealed behind two lockable doors (fig. 5).[8]

The second through fourth pages of the inventory list items in quantities and types so extensive that they appear to have been for resale. Some of the “9 small Looking Glasses” recorded on the third page may have been similar to those Eaglesfield bought from Logan and thus not necessarily made in the joiner’s shop. There are also more hardware and tools than Eaglesfield would have likely have required for his own work:

9 Compass & 1 handsaw. . . , 6 Sett Coffin handles. . . , 2 1/2 Doz: ditto handles & Squares. . . , 19 Drawer & 10 Chest Locks. . . , 11 Nippers Dantzick Lock & 7 pr. Spurrs & 3 smaller Locks. . . , 10 1/2 Inch and 10 3/4 & 13 Inch Augers. . . , 12 m of 2d nails. . . , 4 m of 3d ditto. . . , 12 m Tin Lackerd & other small nails. . . , 13 box irons. . . , 4 doz & 8 pr butts [i.e., butt hinges]. . . , 15 Socket Chisels & S Caulking Irons & 29 Chisels. . . , 2 Lotts Desk Locks & 1 box ditto. . . , 2 Drawer Locks & parcel [of] Screws. . . , 8 rass Locks & pins. . . , 6 Doz: handles & Scutcheons. . . , 16 pr. Hinges. . . , 8 Doz Scutcheons. . . , 2 Doz Knobs & 18 Drops. . . , 8 Doz & 10 Drops & Latche. . . , 3 Doz plane Irons & 16 padlocks & Spri[n]gs. . . , 3 Doz Small knives & 10 pr bright hinges. . . , 7 Doz: Dove Tails. . . , 2 Doz H hinges. . . , 22 files & 24 Scissors. . . , 15 Rules. . . , 4 Addices & 24 Hatchets. . . , 18 broad & 1 narrow Axe. . . , 20 Doz: Gimlets & 6 Chest Locks.

The third and fourth pages of the inventory also list substantial quantities of fabric, tape, ribbon, clothing, spices, spectacles, knives, and other items. These goods are evidence that Eaglesfield, like John Head, expanded his business to encompass distribution and lines of merchandise beyond furniture making, which was essential in a barter economy.[9]

The fifth page of the inventory appears to relate exclusively to Eaglesfield’s shop (fig. 6), which, judging from the quantities and types of wood, appears to have been active at the time of his demise: “285 Walnut Boards at 2127 foot, 133 Ditto plank at 861 foot, 39 Cedar boards at 195 foot and 5 ps Mahogany plank & boards at 144 foot.” The “3 Work benches” are an indication that others, perhaps including George Wilson, worked in the shop. The range of tools indicates that Eaglesfield could produce both joinery and turning, and their quantity is small enough to suggest that they were not items for sale: “53 moulding planes. . . , 2 Joynters, Strike block. . . , Skew planes Long & 2 fored. . . , 2 Holdfasts hatchets & Six Saws. . . , 4 Mortizing Chisels & formers 2 rasps & 7 files. . . , Morris Saw bow Saw 4 hamers pinchers & Shears. . . , 3 Augers Ladle & Glew pott. . . , 7 Turning Tools Fraw [froe] Compass Sens & Screw Key.” The last two listings—compass centers and a screw key—were parts of a lathe.[10]

The furniture in the shop consisted of a “Buffett 2 Chest of Drawers & Desk & Table” valued at £18, a “Walnut Oval Table 2 Couches & three Chests” valued at £2.5, and “Four Spice boxes” valued at 7s. Given their low valuations, the oval table, couches, chests, and spice boxes may have been incomplete at the time of the appraisal. If so, then several of the pieces of furniture listed on the first page of the inventory may also have been for sale, particularly one of the “escritores.” That form usually does not appear in duplicate in household inventories.[11]

Eaglesfield’s probate records indicate that he was financially successful, transacting business with prosperous mercantile firms and numerous members of Philadelphia’s elite, including Samuel Powel Sr. and Jr., Jonathan Fisher, Israel Pemberton, Lawrence Growden, William Chancellor, Anthony Morris, Logan & Shippen, and Willing & Shippen. Befitting his status, he may even have had his likeness painted by Philadelphia’s leading portrait artist, Gustavus Hesselius (1682–1755), as suggested by the latter’s March 3, 1734 charge of £1.13.3. Eaglesfield’s funeral costs were also substantial, totaling £14.17.4, of which £3 was Sharper’s charge “for work & Horse & at Burial.” A further indication of the cabinetmaker’s prominence is a November 6, 1730, indenture recording his acquisition of premises on a 24- by 102-foot lot on the north side of High Street. This property was in the commercial heart of Philadelphia, on the city’s widest thoroughfare, at the location of its market, and close to the businesses of others with whom Eaglesfield dealt, such as Head and Logan.[12]

Presumably, most furniture commissions in Philadelphia were conveyed orally from a patron (or a patron’s agent) to a shop master like Eaglesfield. As a consequence, only sparse documentation has survived to show how patrons contributed to the design and production of objects or to illuminate the negotiation process. A notable exception is a previously unpublished letter wherein John Grove, a wealthy Barbadian merchant, instructed ship captain Thomas Chalkley (1675–1741) to procure furniture from Eaglesfield (fig. 7). Grove’s letter is transcribed on two pages of an account and letter book kept by Chalkley. Being in a remote location, and wanting the finest furniture with no expense spared, Grove put his “Directions” in writing and insisted that they be transmitted “word for word” to “the best work man in Philada.”[13]

On the second voyage of the New Bristol Hope from Barbados to Philadelphia (fig. 8), April 28–May 30, 1730, Chalkley took on board a trunk and “Bale of Merchandise” with a combined value of “£225.2.5 Barbados Money.” Grove consigned the merchandise to fellow Quaker Chalkley and Philadelphia merchant Peter Lloyd (d. 1744/1745). To prevent the hardware for Grove’s furniture order from being mixed up with the consigned goods and inadvertently sold, Chalkley added the notation, “There is in The Trunk the brasses Locks etc for the scrutore.”[14]

Grove authorized Chalkley to spend the proceeds of the consignment but specified that “whatsoever you buy for me let it be of the choisest Sort because a Good Commodity will Command a Market when a bad one will sell for nothing for I had rather give an Extraordinary Price then miss of that wch is the best.” Given the fact that the Grove family had amassed considerable wealth in the triangular trade and that one of their kin acted as their agent in London, it is significant that John chose to patronize a Philadelphia joiner rather than an English one, particularly since cost did not seem to be an issue. “As to the Cabbinet [scrutoire] made by Ecclesfild,” Grove wrote:

I desire it may be the Ni[c]est and Neatest that hands can make for I would by no means Stint him to a price, but you may remember Blowers & Cogans Cost £26 your Money which is of Wallnut Tree / of which I would want have mine / I make no doubt but you’ll get it as cheap as you Can, and please also to remember that the Locks and brass works Cost me £4-3-6 BBdos money which will make a Very Large abatement of the price he not being at that charge.

He also assured Chalkley, “I am wholly Satisfied wth your Usuall Care and put an Intire Confidence in you.”[15]

Grove’s letter did not specify features for his scrutoire, probably because Eaglesfield had likely made, or was at least intimately familiar with, the one purchased by Grove’s competitor in Barbados, Blower & Cogan. By ordering a similar piece from the same source Grove would have known essentially what he was getting. Grove did, however, provide instructions as to the operation of the locks he furnished:

And least you should forget how the larg Lock belonging To the Desk part of Scrutore is open’d and Lock’d I will now Repeat it—you must Turn it Twice & double Lock it and go on to Turn it the third Time Very Gently till you hear it make a Noise and Tick, Then go no Further but Instead immediately Turn it the Contrary way which will open it but should you Turn it so far after it has Tickt that you Cannot open it Then go on to Lock it one Turn More and you’ll find the like Noise at wch. you must directly Stop and go the other way.

As a negotiating tactic, he also advised Chalkley to get a price for the locks and brasses before disclosing that he already had them in hand: “It would be proper to keep a secret from the maker that you have the Locks etc. ~ Untill you hear what he would Reckon for ’em and then you can Keep him to his word.” Grove may have gotten the hardware in London and thus was confident that he had them at prices cheaper than those at which Eaglesfield could buy them in Philadelphia.[16]

Although scrutoires were among the most expensive case forms available during the first three decades of the eighteenth century, £26 would have been an extraordinary price for a standard example. Of the two scrutoires listed in Eaglesfield’s probate inventory, one was valued at £7.10 and the other was included in a group of eight pieces valued at £12.15. By further comparison, Chalkley debited Samuel Collynns £7.10 for “a black Wallnut Scutroir” in 1730.[17]

Grove’s reference to Blower & Cogan’s walnut “scrutore” costing £26 raises questions about the appearance of that object as well as of the piece Grove wanted Eaglesfield to make for him. During the first quarter of the eighteenth century, the term “scrutoire” generally referred to a double-case piece with a fall front similar to the Evans example (fig. 4). Any such piece costing in the vicinity of £26, especially if primarily in walnut (a wood plentiful in Philadelphia), must have had additional features. Possible options include an elaborate interior or pediment, veneers of exotic woods, or mirrors. Given the 1730 date of Grove’s order, it is also possible that his use of the term “scrutore” referred to a desk-and-bookcase (fig. 9). In 1736 John Head charged James Steel £15 for “a scrudore and Bookcas apon a Chest of drawers,” one of the most complex and costly pieces recorded in Head’s account book, and perhaps the same “Desk and Book Case wth Glass Doors,” valued at like amount in Steel’s probate inventory.[18]

In a postscript, Grove expanded his order to include two tables:

I do desire you will also bespeak of the best work man in Philada. a Table much of a Round oval to hold 6 persons & an other to hold 12 is to Convenss. I should have ’em of wallnut Tree or any other fine wood which may be more proper, but should there be a neater Workman Than Ecclesfield I desire you will Employ him & desire you will Consult Peter Loyd about these things ~ give the workman my Directions word for word.

Gate-leg tables seating six were the norm; those seating twice that number were uncommon and expensive (fig. 10). Grove’s caveat regarding “a neater Workman” implies that while he knew of no one better than Eaglesfield, he may have been uncertain about the cabinetmaker’s ability to do turning for the bases; however, the tools and lathe components in the latter’s inventory indicate that such concern was unnecessary.[19]

In England, the importation of walnut was still popular in the 1730s, despite the greater availability of mahogany. Grove requested that his tables be made of walnut or “any other fine wood which may be more proper.” This calls into question why a Barbadian would order walnut when mahogany was plentiful in the West Indies and could readily be shipped to Philadelphia. Indeed, we know that Eaglesfield had it in his inventory. Grove may have deemed walnut a desired novelty, especially if imported from Pennsylvania, which some Barbadians held in high esteem. A year before, the governor of the island had told Chalkley, “Whoever lived to see it, Pennsylvania would be the metropolis of America, in some hundreds of years.”[20]

Now that Eaglesfield has been documented as a prominent early cabinetmaker, scholarship can focus on finding his furniture. Objects made by him may have descended in the families of fellow Baptists or the many individuals listed in his estate accounting. It is even possible that the scrutoire and tables mentioned in Grove’s letter have survived. Since Eaglesfield did not die until 1732 and Chalkley made many more voyages to Barbados, there would have been time for the fulfillment of Grove’s order. Should any marked objects be discovered, the script can be compared with Eaglesfield’s signature on the original will. Similarly, additional documents pertaining to his life and career may survive in archival collections in Philadelphia and Barbados, as well as in other areas where Eaglesfield had patrons. It is hoped that the manuscripts discussed in this essay will prompt further revelations about Eaglesfield and his work, just as the discovery of John Head’s account book did for his production.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For assistance with this article, the author thanks Adam Bowett, Wendy A. Cooper, Beatrice B. Garvan, Laura C. Keim, Deborah Rebuck, Christopher R. Storb, Philip D. Zimmerman, and the staffs of the Dietrich American Foundation, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, and Library Company of Philadelphia.

Jack Lindsey, Worldly Goods: The Arts of Early Pennsylvania, 1680–1758 (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1999). Jay Robert Stiefel, “Philadelphia Cabinetmaking and Commerce: The Account Book of John Head, Joiner, 1718–1753” and “The Head Account Book as Artifact: A Supplementary Essay,” Library Bulletin (American Philosophical Society), n. s., 1, no. 1 (Winter 2001), http://www.amphilsoc.org/bulletin/20011/stiefpdf.pdf. Jay Robert Stiefel, Alan Andersen, and Christopher Storb, “The John Head Project, Part 1: Documenting His Work,” Antiques & Fine Art 9, no. 1 (autumn/winter 2008): 190–93. Andrew Brunk, “The Claypoole Family Joiners of Philadelphia: Their Legacy and the Context of Their Work,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2002), pp. 147–73. Alan Miller, “Flux in Design and Method in Early Eighteenth-Century Philadelphia Furniture,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2014), pp. 30-86.

Mrs. Thomas Potts James, Memorial of Thomas Potts, Junior, etc. (Cambridge, Mass.: privately printed, 1874), p. 381, citing ledgers given to the Philadelphia Library by Robert Grace. “Lowden” is the spelling also found in his will. Will of Hugh Lowden, Philadelphia Wills 1726, Will Book D, 355, no. 276, Philadelphia Register of Wills. William McPherson Hornor Jr., Blue Book Philadelphia Furniture (Philadelphia: privately printed, 1935), pp. 2, 3, 26–27, 39, 66.

Stiefel, “Philadelphia Cabinetmaking and Commerce,” sec. X. C. 4, p. 45; John Head Account Book, p. 60, Vaux Papers, 1738–1985, American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia, Miscellaneous Manuscript Collection 73. James Logan Ledger 1720–1727, p. 180, collection no. 0379, vol. 3, Historical Society of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (hereafter HSP).

Will of Barnard Eaglesfield, February 17, 1732/1733, probated April 13, 1733, Will Book E, 231, no. 310, Philadelphia Register of Wills. Probate administration documents filed with the will include a one-page affirmation by the witnesses dated March 12, 1732[/1733]; a five-page inventory of his house and shop dated May 15, 1733; and an eight-page list of creditors and debtors dated July 18, 1735. (All of these will documents will hereafter be cited as Will of Barnard Eaglesfield.) None of the foregoing is listed in Richard T. Williams and Mildred C. Williams, Index of Wills & Administration Records, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1682–1782 (Danboro, Pa.: Richard T. Williams and Mildred C. Williams, 1971–1972), Index KFP 144.8.P5 W54 1972, HSP. The probate inventory of Philadelphia joiner Charles Plumley (d. 1708) lists many tools, materials, chairs, and unfinished furniture, but only a few case pieces (Benno M. Forman, American Seating Furniture, 1630–1730 [New York: W. W. Norton, 1988], app. 1).

Will of Barnard Eaglesfield. Early Baptist records are notoriously sparse, particularly as to congregants. No records were located for the birth, baptism, or marriage of Barnard. There are references, however, to the ministry of George Eaglesfield (Minutes of the Philadelphia Baptist Association from A.D. 1707 to A.D. 1807, edited by A. D. Gillette [Philadelphia: American Baptist Publication Society, 1851], pp. 12, 16; David Spencer, Early Baptists of Philadelphia [Philadelphia: W. Syckel Moore, 1877], chap. 5, pp. 58–59, 78). The only other Eaglesfield connected with Baptists in Philadelphia in the generation of George Eaglesfield is a “John Eaglesfield.” His name appears in the Will of William Elton (shipwright), June 22, 1702, proved December 15, 1702, Philadelphia Wills, Book B, no. 258. In 1698 Elton and his wife were baptized and became part of the first Baptist congregation to convene in Philadelphia (William Williams Keen, The Bi-centennial Celebration of the Founding of the First Baptist Church of Philadelphia [Philadelphia: American Baptist Publication Society, 1898], p. 468). George Eaglesfield’s purchases from Logan were all in 1720 and included nothing related to furniture. Logan Ledger, p. 28. Two other sons of George Eaglesfield are noted as non-Quakers buried in Philadelphia: William, on August 19, 1701, and Benjamin, April 9, 1703 (William W. Hinshaw, Encyclopedia of American Quaker Geneaology, 7 vols. [Ann Arbor, Mich.: Geneaological Publishing Co., 1938], 2: 443).

Will of Barnard Eaglesfield. Branson sold Head 7 1/2 dozen escutcheons and drops in 1721, and butt hinges in 1737 (Stiefel, “Philadelphia Cabinetmaking and Commerce,” nn. 310–14). Branson had sold James Logan a bedstead and sacking bottoms and “Cornishes for the Bed and 3 Windows” in 1712. Laura C. Keim, Stenton Room Furnishings Study (Philadelphia: National Society of the Colonial Dames of America in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, 2011), p. 46. Will of James Tutthill [Tuthill], February 9, 1727/1728, proved February 9, 1727, Philadelphia Wills, Book E, no. 71. Keen, Founding of the First Baptist Church, pp. 457–58. Ann Eaglesfield, formerly Bellows, was disowned by the Philadelphia Monthly Meeting for marrying “out of unity” on 1 mo. 27, 1724 (March 27, 1724) (Hinshaw, Encyclopedia of American Quaker Genealogy, 2: 510).

Will of Barnard Eaglesfield. Stiefel, “Philadelphia Cabinetmaking and Commerce,” n. 44.

Will of Barnard Eaglesfield. For more on scrutoires, see Peter Kenny, “Ark of the Covenant: The Remarkable Inlaid Cedar Scrutoir from the Brinckerhoff Family of Newtown, Long Island,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2014), pp. 2–29; and Sumpter Priddy III, “Musings on a Scottish-Irish Desk Form in Colonial Virginia: The Scrutoire,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 33 (2012), http://www.mesdajournal.org/2012/musings-sottish-irish-desk-form-colonial-virginia-scrutoire/.

Will of Barnard Eaglesfield. See “The Limitations of a Barter Economy,” in Stiefel, “The Head Account Book as Artifact,” sec. 1.A., pp. 82–85.

Will of Barnard Eaglesfield.

Ibid.

Will of Barnard Eaglesfield. Indenture from Joseph and Elizabeth Richardson to Bernard Eaglesfield, November 6, 1730 (collection of the author). This was the merchant Joseph Richardson, not the silversmith Joseph Richardson Sr., whose wives were Hannah and Mary, respectively. Jay Robert Stiefel, “All in the Family: Joseph Richardson’s Earliest Silver,” Catalogue of Antiques & Fine Art 5, no. 1 (Spring 2004): 145–49.

Thomas Chalkley, Account and Letter Book, 1729–1732, p. 46, collection no. 3215, location: 3V, 118F, HSP (hereafter Chalkley Account Book, 1729–1732).

Ibid. For other furniture entries in Chalkley’s accounts, see Stiefel, “Philadelphia Cabinetmaking,” nn. 494, 654.

Chalkley Account Book, 1729–1732, p. 46. John Grove appears to have been the son of another John Grove, “one of Barbados’ largest slave importers” (S. D. Smith, Slavery, Family, and Gentry Capitalism in the British Atlantic: The World of the Lascelles, 1648-1834 [Cambridge, Eng.: Cambridge University Press, 2006], p. 29). The elder Grove’s will mentions his widow “Rebeckah” and a minor son John (Will of John Grove, St. Georges Parish, Barbados, May 31, 1717, proved June 18, 1717, RB6/4, 151, compiled and edited in Joanne McRee Sanders, Barbados Records Wills and Administrations, vol. 3, 1701–1725 [Houston, Tex.: Sanders Historical Publications, 1981], p. 147). Rebecca Grove also appears in Chalkley’s accounts. In 1718 he transported sugar for her from Barbados and sold it in London, and clothing and goods in silver, brass, and pewter from London were consigned to her by Chalkley for his own account. John’s mother had ordered a tankard, salvers, and other silver. Thomas Chalkley, Account Book, 1718–1727, pp. 2, 7, collection no. LCP in 132, location: limbo 3C, HSP. The “Jos Grove Mercht. In Londn,” mentioned in John’s letter appears to have been the son of his uncle Joseph Grove (d. 1713), a merchant in Bermondsey, Surrey. Sanders, ed., Barbados Records Wills and Administrations, pp. 147–48. Chalkley may have been transcribing Grove’s spellings when he referred to Eaglesfield as “Ecclesfild” and “Ecclesfield”. In Chalkley’s earlier accounts, Barnard’s father appears in transactions in 1720 and 1722 as “George Eaglesfield” (Chalkley Account Book, 1718–1727, pp. 7, 30.) No persons named Eccelesfild or Eccelsfield could be found in contemporaneous records pertaining to Philadelphia or in a READEX search of local newspapers of that era.

Blower & Cogan imported slaves into Barbados (Eli Faber, Jews, Slaves and the Slave Trade / Setting the Record Straight [New York: NYU Press, 2000], p. 96). Chalkley Account and Letter Book, 1729–1732, p. 46.

Will of Barnard Eaglesfield. Chalkley Account Book, 1729–1732, p. 55.

Stiefel, “Philadelphia Cabinetmaking and Commerce,” sec. X. E. 12, p. 15, and n. 681. Will of James Steel, Philadelphia Wills, 1741 Will Book F, 261, no. 289.

Chalkley Account Book, 1729–1732, p. 46. Lindsey, Worldy Goods, p. 144, nos. 50–52.

Chalkley Account Book, 1729–1732, p. 46. Adam Bowett, “After the Naval Stores Act: Some Implications for English Walnut Furniture,” Furniture History 31 (1995): 116. Thomas Chalkley, The Journal of Thomas Chalkley: A Minister of the Gospel in the Society of Friends (1870), p. 295. Will of Barnard Eaglesfield.