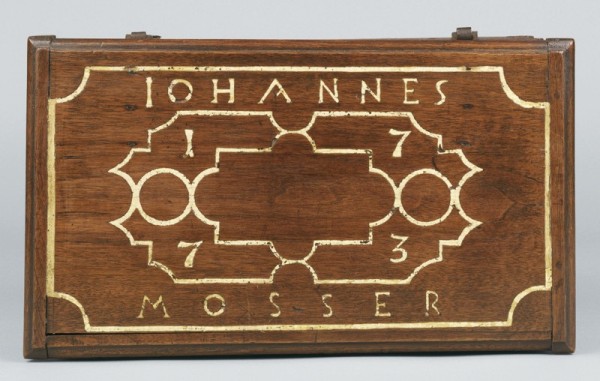

Miniature chest, made for Johannes Mosser, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1773. Walnut and sulfur inlay with tulip poplar; iron. H. 7 1/4", W. 14 3/4", D. 8 5/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; photo, Laszlo Bodo.)

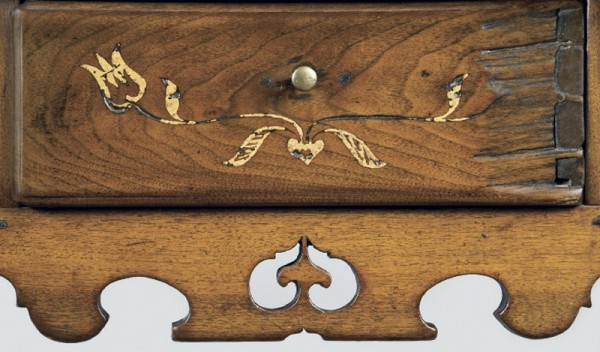

Lid of the miniature chest illustrated in fig. 1.

Map of Pennsylvania. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Chest, Bologna, Italy, ca. 1550. Walnut and probable orpiment inlay. H. 16 1/8", W. 32 1/4", D. 14 1/2". (Courtesy, Museum Angewandte Kunst, Frankfurt am Main; photo, Ute Kunze.)

Detail of the inlay on the front of the chest illustrated in fig. 4.

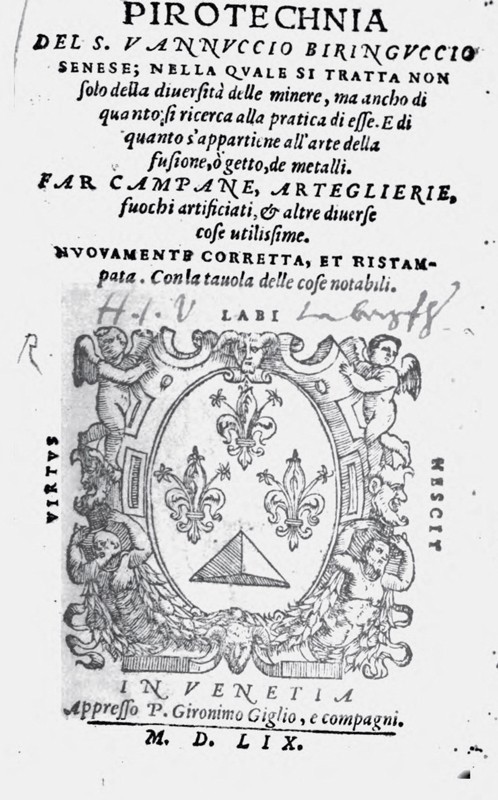

Title page of De la pirotechnia, written by Vannoccio Biringuccio, 4th edition, printed by P. Gironimo Giglio, Venice, Italy, 1559. (Courtesy, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich.)

Detail of a relief carved fleur-de-lis on the schrank illustrated in fig. 38. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a sulfur-inlaid fleur-de-lis on the schrank illustrated in fig. 27. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

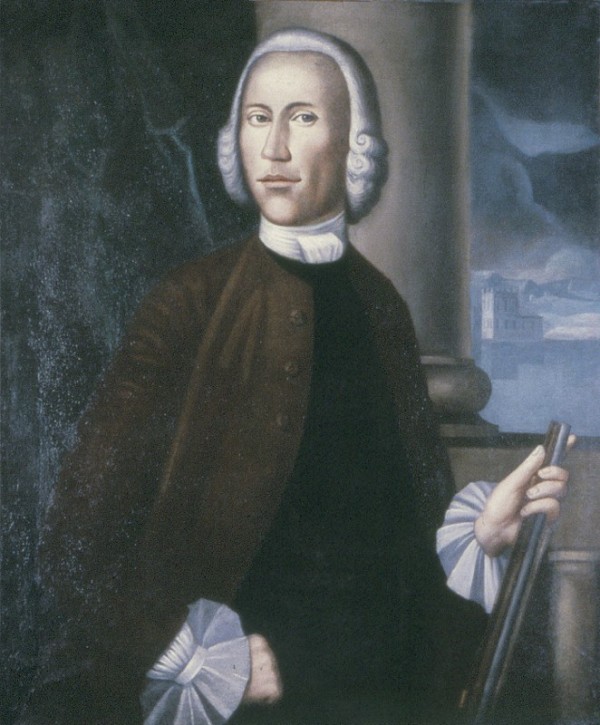

Portrait of William Henry, attributed to Benjamin West, Lancaster, Pennsylvania, ca. 1754. Oil on canvas. 36 3/4" x 30 1/2". (Courtesy, Philadelphia History Museum at the Atwater Kent, Historical Society of Pennsylvania Collection.)

House of Christian Herr, West Lampeter Township, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1719. (Courtesy, 1719 Hans Herr House & Museum; photo, Winterthur Museum, Laszlo Bodo.) The stone lintel above the door is inscribed “17 CH HR 19.”

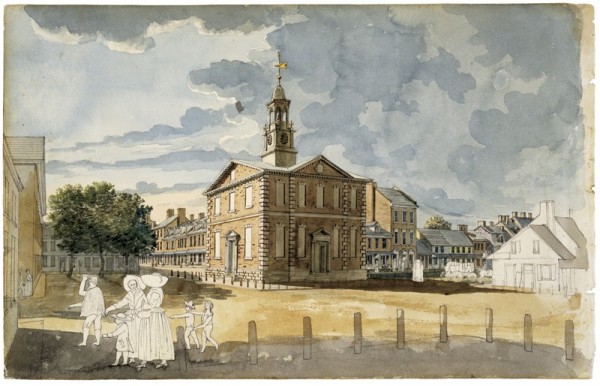

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, view of the Lancaster County Courthouse (built 1787), Lancaster, Pennsylvania, ca. 1801. Watercolor, pencil, pen and ink on laid paper. 8" x 12 3/4". (Courtesy, Maryland Historical Society, 1960.108.1.8.8.)

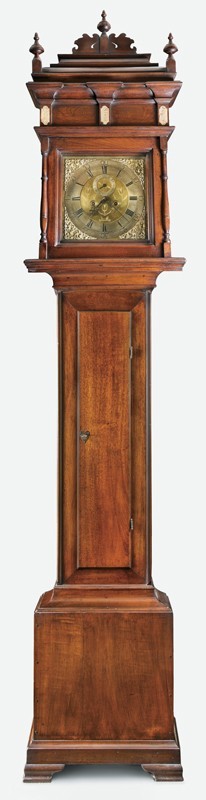

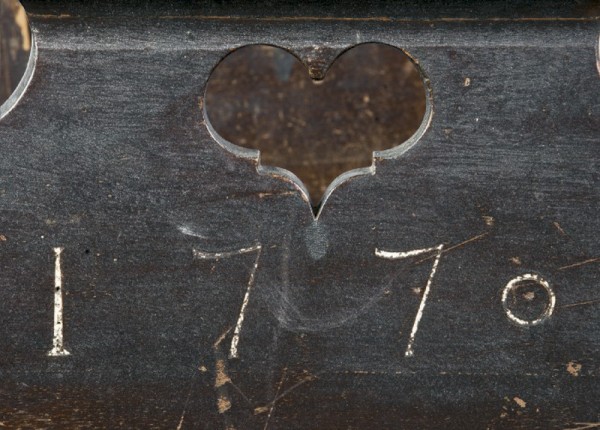

Tall clock, made for Andreas and Catharina Beierle, probably Lancaster, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1745. Black walnut with tulip poplar. H. 91 1/4", W. 21 3/4", D. 12 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Winterthur Museum, Laszlo Bodo.) The base molding is replaced and the movement is not original to the case.

Detail of the carving on the tall clock illustrated in fig. 12.

Pendulum door of the clock illustrated in fig. 12.

Mantel, probably Lancaster, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1746. (Whereabouts unknown; photo, Raymond J. Brunner.) This photograph was taken in the shop of antiques dealer Hattie Brunner in Reinholds, Lancaster County.

Schrank, probably made for Michael and Anna Margaretha Fordney, Lancaster, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1758. Walnut and pewter inlay with pine and tulip poplar; brass, iron. H. 84", W. 78", D. 21 3/4". (Courtesy, Clint and Cindy McCauley; photo, Pook & Pook.) The feet are a later addition.

Schrank, made for Johannes and Anna Maria Spohr, Lancaster, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1760. Walnut and mixed-wood inlay with tulip poplar; brass. H. 85", W. 71 1/2", D. 26". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art; photo, Pook & Pook.)

High chest, made for Matthias Slough, Lancaster, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1770–1785. Mahogany with tulip poplar; brass. H. 96", W. 42", D. 24". (Courtesy, LancasterHistory.org, Heritage Center Collection, bequest of the estate of George J. Finney; photo, Winterthur Museum, Laszlo Bodo.)

Schrank, made for Christian and Veronica Herr, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1763. Walnut and sulfur inlay with tulip poplar and oak; brass, iron. H. 86", W. 84 1/2", D. 30 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the sulfur inlay on the schrank illustrated in fig. 19. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the sulfur inlay on the schrank illustrated in fig. 19. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Schrank, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1765. Walnut; brass, iron. H. 85 1/2", W. 71 1/2", D. 26". (Private collection; photo, copyright 1995 Christie’s Limited.)

Detail of the carved fleur-de-lis on the schrank illustrated in fig. 19. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the carving on the door of a building in Hildesheim, Germany, ca. 1730. (Photo, Lisa Minardi.)

Landisville Mennonite Meetinghouse, East Hempfield Township, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1740. (Photo, Lisa Minardi.)

Detail of a wrought iron hook inside the schrank illustrated in fig. 34. (Photo, Winterthur Museum, James Schneck.)

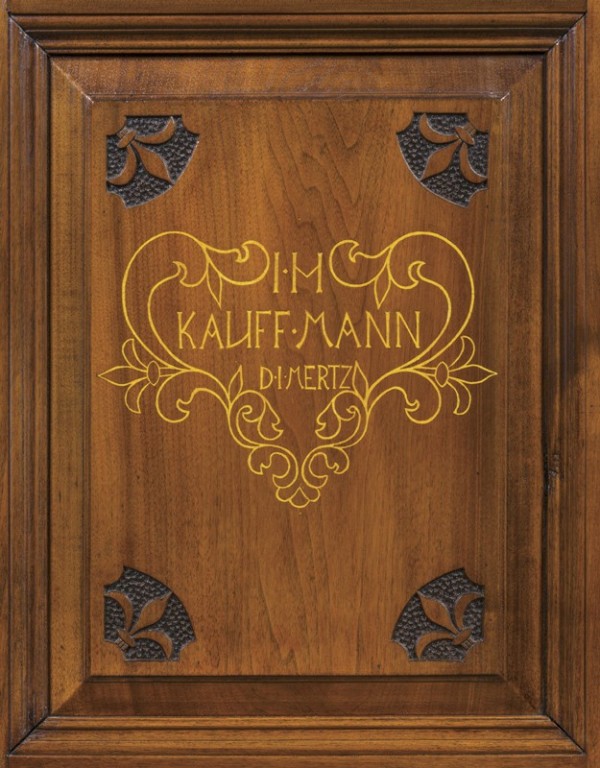

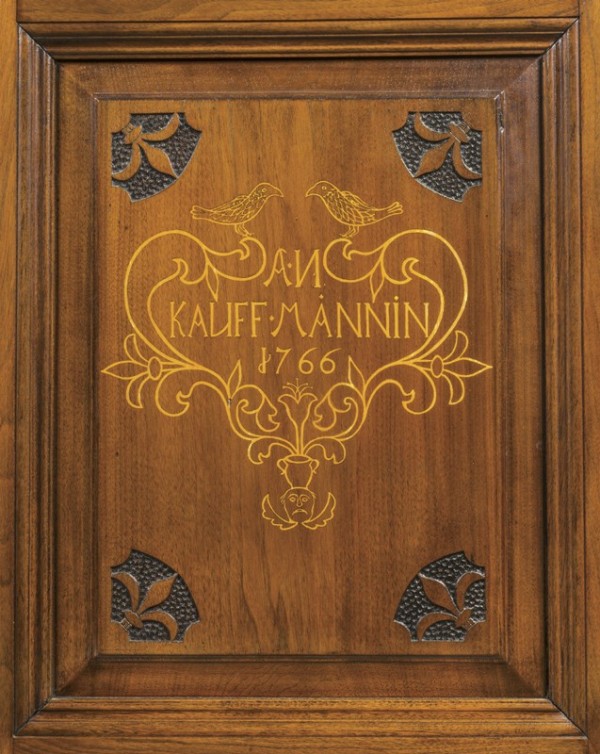

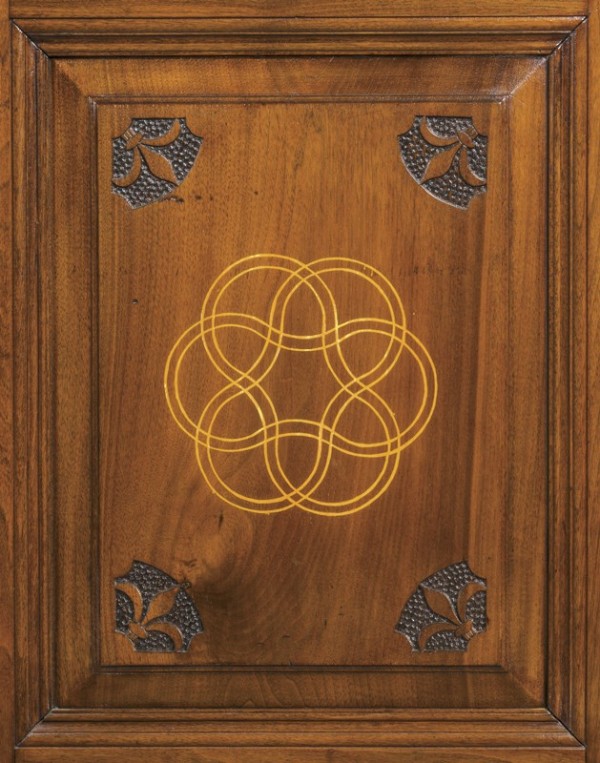

Schrank, made for Johannes and Anna Kauffmann, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1766. Walnut and sulfur inlay with tulip poplar and oak; brass, iron. H. 89", W. 84", D. 30". (Courtesy, Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, State Museum of Pennsylvania; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

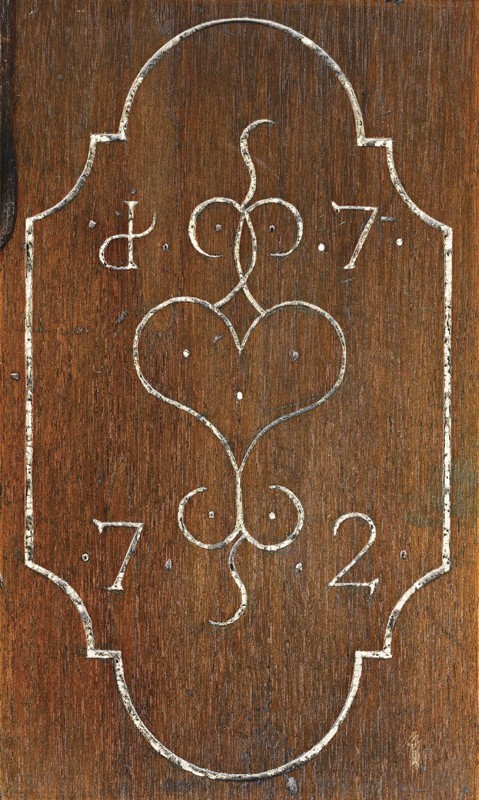

Detail of the inlay on the schrank illustrated in fig. 27. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the schrank illustrated in fig. 27. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the schrank illustrated in fig. 27. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Schrank, probably made for Peter and Maria Bachmann, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1767. Walnut and sulfur inlay with tulip poplar and oak; brass, iron. H. 89", W. 84 1/4", D. 30". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The feet are replaced.

Detail of the inlay on the schrank illustrated in fig. 31. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the schrank illustrated in fig. 31. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

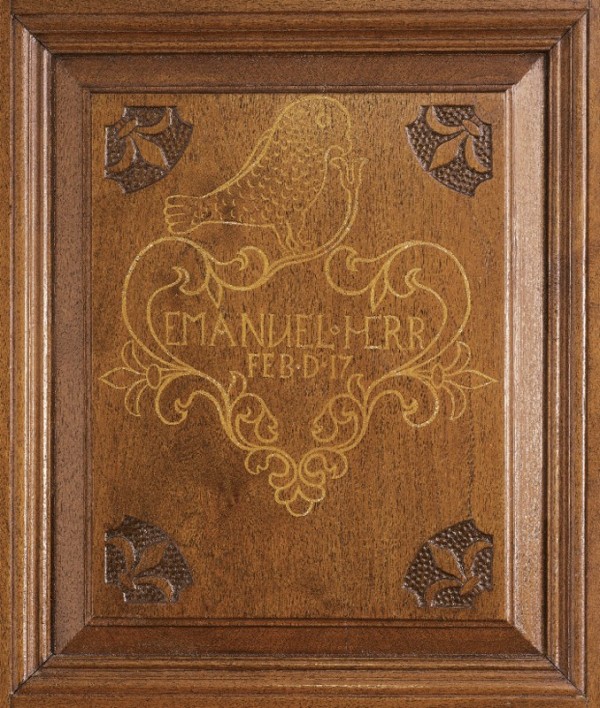

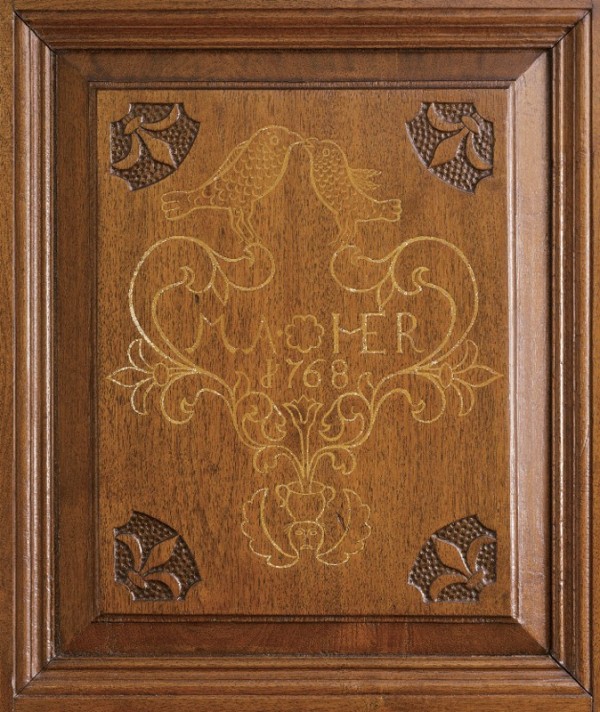

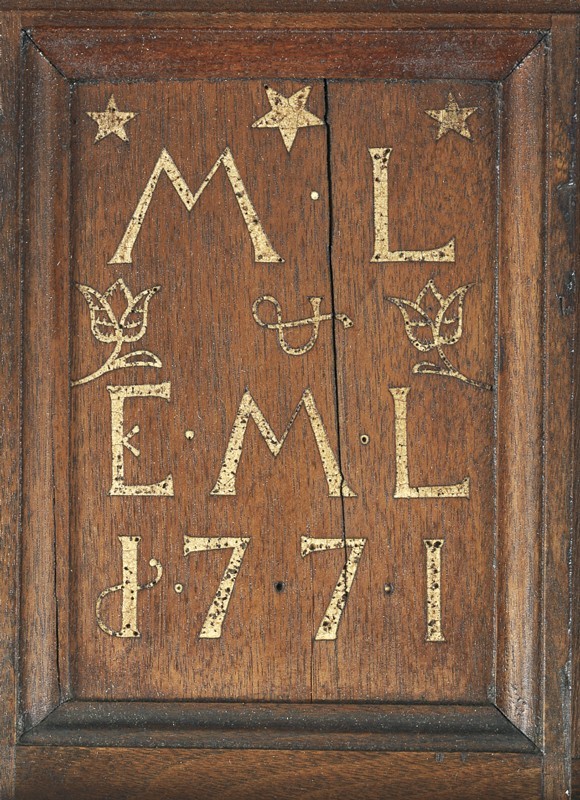

Schrank, made for Emanuel and Mary Herr, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1768. Walnut and sulfur inlay with tulip poplar. H. 89 1/2", W. 85 3/4", D. 30 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; photo, Laszlo Bodo.)

Detail of the inlay on the schrank illustrated in fig. 34. (Photo, Winterthur Museum, James Schneck.)

Detail of the inlay on the schrank illustrated in fig. 34. (Photo, Winterthur Museum, James Schneck.)

Detail of the carving at the base of the schrank illustrated in fig. 34. (Photo, Winterthur Museum, James Schneck.)

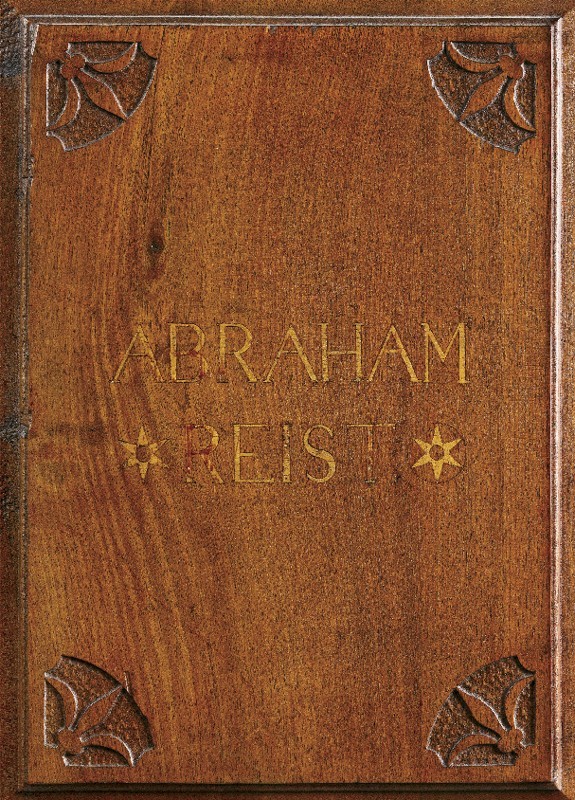

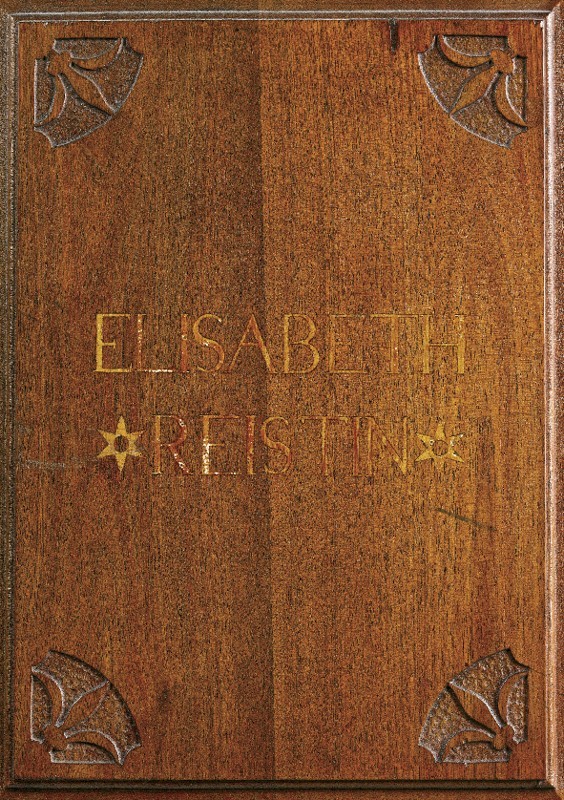

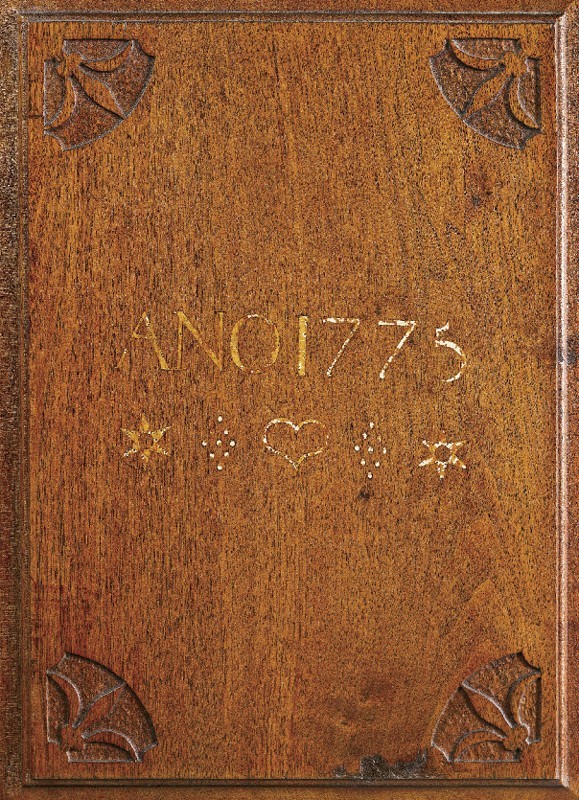

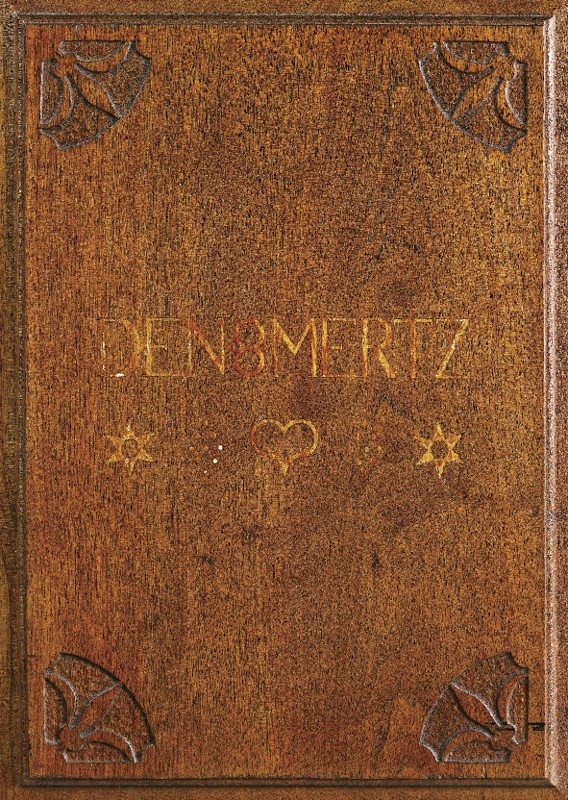

Schrank, made for Abraham and Elisabeth Reist, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1775. Walnut and sulfur inlay with pine; iron, brass. H. 91", W. 86", D. 31". (Courtesy, LancasterHistory.org, Heritage Center Collection, acquired through the generosity of the James Hale Steinman Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the schrank illustrated in fig. 38. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the schrank illustrated in fig. 38. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the schrank illustrated in fig. 38. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the schrank illustrated in fig. 38. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1765. White pine; paint; iron. H. 25 1/2", W. 52", D. 24 1/2". (Courtesy, Clarke Hess; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The paint is restored.

Detail of the chest illustrated in fig. 43. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1765. White pine; paint; brass, iron. H. 26 1/4", W. 53 1/4", D. 27 1/8". (Private collection; photo, David Bohl.) The paint is restored.

Detail of a hinge inside the chest illustrated in fig. 45.

Chest, probably made for Michael Kauffman, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1765. Walnut and sulfur inlay; iron. H. 25 5/8", W. 51 1/2", D. 24 3/4". (Courtesy, Rocky Hill Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The feet are replaced.

Detail of the inlay on the chest illustrated in fig. 47. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, possibly made for Daniel Wolf, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1766. Walnut and sulfur inlay with white pine; iron. H. 27 1/4", W. 52", D. 24". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The feet are replaced.

Detail of the inlay on the chest illustrated in fig. 49. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

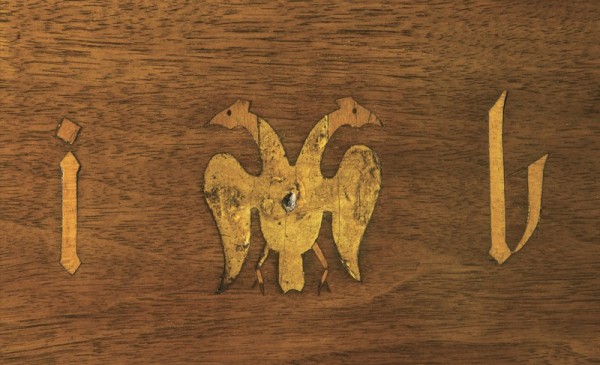

Chest, made for “I D,” Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1768. Walnut and sulfur inlay; iron. H. 25 1/8", W. 51 7/8", D. 24 7/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the chest illustrated in fig. 51. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the chest illustrated in fig. 51. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a foot on the chest illustrated in fig. 51. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tall clock, probably made for Frederick Stone, movement signed by Rudolph Stoner, Lancaster, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1762. Cherry, mixed-wood inlay, and pewter inlay with tulip poplar. H. 101 1/2", W. 21", D. 11 1/2". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The feet are replaced and a board has been added between the cornice and sarcophagus.

Hood of the clock illustrated in fig. 55. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Pendulum door of the clock illustrated in fig. 55. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Pair of candlesticks, marked by Johann Christoph Heyne, Lancaster, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1755–80. Pewter. H. 22, W. 7 3/4", D. 8 5/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tall clock, made for the Eaby family, movement signed by Christian Forrer, Lampeter, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1765. Walnut and mixed-wood inlay with walnut; brass. H. 92 1/2", W. 19 3/4", D. 13". (Courtesy, Carolyn C. Wenger; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The feet are replaced; the broken scroll pediment is a later addition.

Hood of the clock illustrated in fig. 59. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tall clock, made for Peter Ferree, movement signed by Rudolph Stoner, Lancaster, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1765. Cherry and sulfur inlay with tulip poplar. H. 107 1/4", W. 21", D. 11 1/2". (Courtesy, Rocky Hill Collection; photo, Winterthur Museum, Laszlo Bodo.)

Hood of the clock illustrated in fig. 61. (Photo, Laszlo Bodo.)

Tall clock, made for Christian Schwar, movement attributed to George Hoff, Lancaster, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1766. Walnut and sulfur inlay with tulip poplar. H. 107", W. 19 1/4", D. 11". (Courtesy, Rock Ford Plantation, bequest of John J. Snyder Jr.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The feet, finials, and valance are replaced.

Hood of the clock illustrated in fig. 63. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tall clock, made for Daniel Besore, movement signed by George Hoff, Lancaster, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1768. Cherry, red mulberry, and walnut with pewter and mixed-wood inlay and tulip poplar. H. 105", W. 19 3/4", D. 11". (Courtesy, Dietrich American Foundation.) The finials and valance are replaced.

Hood of the clock illustrated in fig. 65. (Photo, Dietrich American Foundation.)

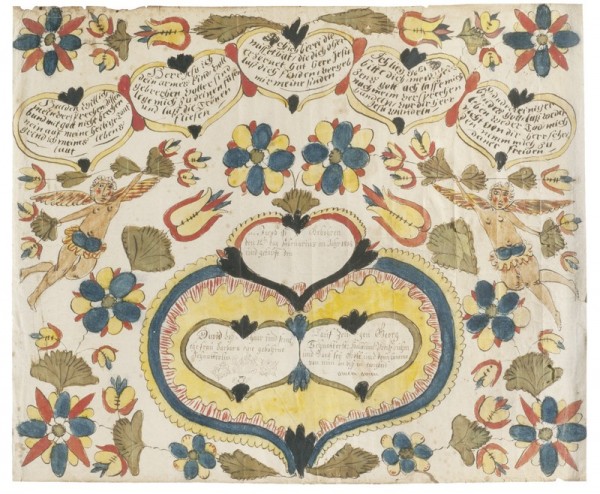

Birth and baptismal certificate for Jacob Boshaar, attributed to Joseph Lochbaum, Washington Township, Franklin County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1805. Watercolor and ink on laid paper. 13" x 15 1/2". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art, promised gift of Joan and Victor Johnson; photo, Graydon Wood.)

Tall clock, movement attributed to Samuel Meyli, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1770. Walnut and sulfur inlay with tulip poplar; brass. H. 102", W. 20 1/2, D. 11 1/2". (Private Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The feet, finials and plinths, and valance are restored.

Hood of the clock illustrated in fig. 68. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tall clock, movement signed by Benjamin Lamb of London, case made in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1765. Walnut with tulip poplar. H. 96 1/2", W. 22 1/8", D. 12 1/2". (Courtesy, Rock Ford Plantation, bequest of John J. Snyder Jr.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Hood of the clock illustrated in fig. 70. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, possibly made for Johannes Kilheffer, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1765. Walnut and mixed-wood inlay with white pine; iron, brass. H. 23", W. 42 1/2", D. 19 1/4". (Courtesy, Lancaster Mennonite Historical Society, bequest of John J. Snyder Jr.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Lid of the chest illustrated in fig. 72. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the façade of the chest illustrated in fig. 72. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, probably made for Jacob Gochnauer, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1767. Walnut, mixed-wood inlay, and bone inlay; iron. H. 24 1/4", W. 50", D. 23 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the façade of the chest illustrated in fig. 75. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, made for “EL S,” Pennsylvania, 1769. Walnut, pewter inlay, and sulfur inlay with pine and oak; iron, brass. H. 24 1/4", W. 53 3/4", D. 22 3/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a drawer from the chest illustrated in fig. 77. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Schrank, made for Georg Huber, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1779. Walnut and sulfur inlay with tulip poplar, pine, and oak; brass and iron. H. 83 1/8", W. 78", D. 27 1/2". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1957-30-1.) The feet are replaced.

Chest, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1783. Walnut and sulfur inlay with pine; brass, iron. H. 29 1/4", W. 54 1/2", D. 26 1/2". (Courtesy, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution; photo, Winterthur Museum, Laszlo Bodo.) The feet are replaced.

End of the chest illustrated in fig. 80.

Till compartment of the chest illustrated in fig. 80.

Chest, made for Henrich Kauffman, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1779. Walnut and sulfur inlay. Dimensions unrecorded. (Photo, Steven F. Still Antiques.)

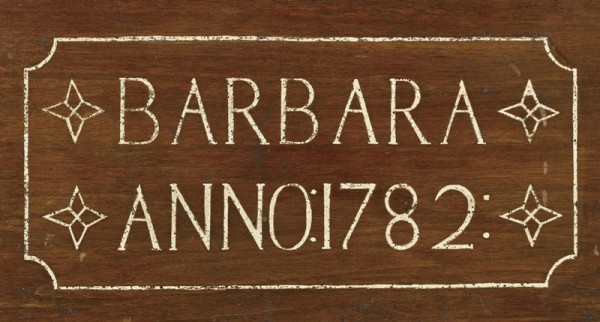

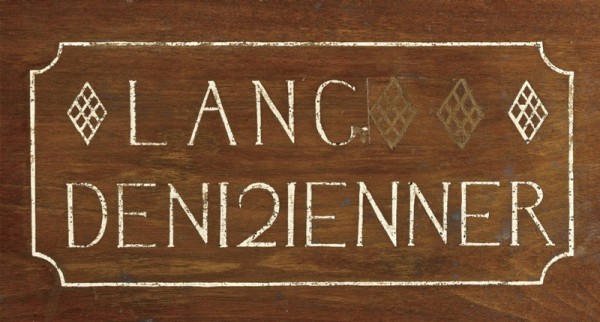

Chest, made for Barbara Lang, Manheim Township area, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1782. Walnut and sulfur inlay with pine and tulip poplar; iron. H. 26 5/8", W. 52", D. 26 1/2". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert L. Raley, 1978-101-1; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the chest illustrated in fig. 84. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the chest illustrated in fig. 84. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

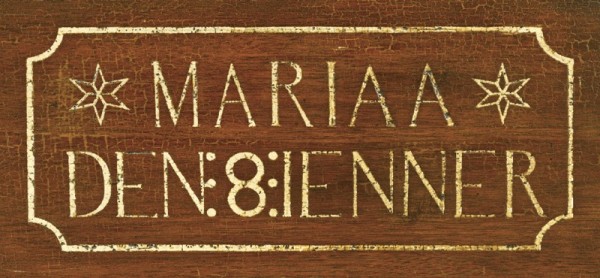

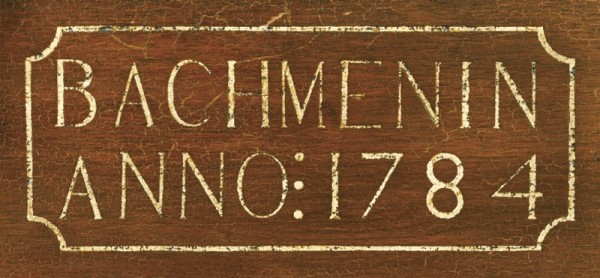

Chest, made for Maria Bachman, Manheim Township area, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1784. Walnut and sulfur inlay with tulip poplar; iron, brass. H. 26 3/4", W. 52", D. 25 1/2". (Courtesy, Joan and Victor Johnson; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the chest illustrated in fig. 87. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the chest illustrated in fig. 87. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on a chest, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1784. Walnut and sulfur inlay. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; photo, James Schneck.)

Table, made for “I R,” Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1788. Walnut and sulfur inlay with white pine; brass. H. 28 5/8", W. 52 3/4", D. 31". (Courtesy, Chester County Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The stretchers are replaced.

Detail of the inlay on the table illustrated in fig. 91. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

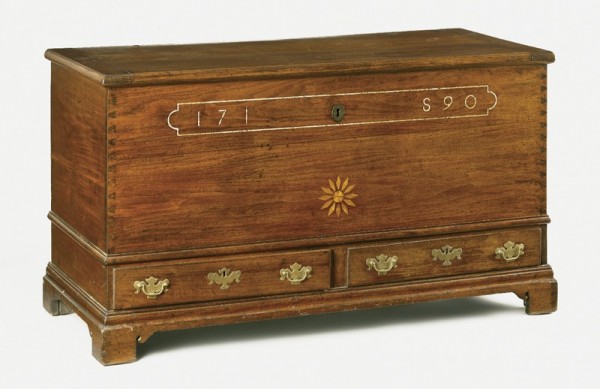

Tall clock, movement by George Hoff, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1790. Walnut and sulfur inlay with tulip poplar, pine, and oak. H. 89 1/2", W. 20 1/2", D. 16". (Courtesy, Joan and Victor Johnson; photo, Winterthur Museum, Laszlo Bodo.)

Detail of the inlay on the clock illustrated in fig. 93.

Miniature chest, made for “BA RI,” Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1799. Walnut and sulfur inlay with tulip poplar; iron. H. 8 1/2", W. 17 3/4", D. 9 1/2". (Courtesy, Kelly Kinzle Antiques; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the chest illustrated in fig. 95. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Straightedge, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1800. Walnut and sulfur inlay. H. 1 7/8", W. 22 1/2", D.1/4". (Courtesy, Stephen and Dolores Smith; photo, Winterthur Museum, Laszlo Bodo.)

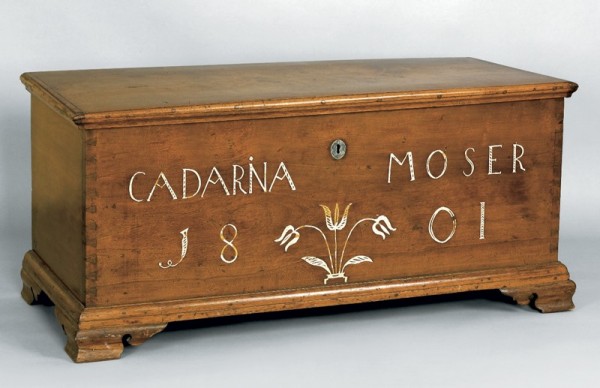

Chest, made for Cadarina Moser, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1801. Walnut and sulfur inlay with white pine; iron. H. 23", W. 48 1/4", D. 20". (Photo, Pook & Pook.)

Schrank, probably made for Johannes and Anna Elisabeth Kauffman, East Hempfield Township, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1764. Walnut and sulfur inlay with tulip poplar and oak; brass, iron. H. 80 1/2", W. 73 3/4", D. 35". (Private collection; photo, Philip H. Bradley Co.)

Schrank, made for David and Anna Mumma, West Hempfield Township, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1768. Walnut and sulfur inlay; iron, brass. H. 84 1/2", W. 74 1/2", D. 27 1/4". (Courtesy, Lancaster Mennonite Historical Society, bequest of John J. Snyder Jr.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tall clock, probably Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1767. Walnut, sulfur inlay, and mixed-wood inlay with tulip poplar. H. 89 1/8", W. 19 3/4", D. 10 3/4". (Courtesy, Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, 01.24.25.)

Hood of the clock illustrated in fig. 101.

Schrank, probably made for Peter and Ada Schwar, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1769. Walnut and sulfur inlay with tulip poplar and white pine; iron, brass. H. 82", W. 87", D. 27 1/2". (Courtesy, Clarke Hess; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The five ball feet are missing.

Detail of the inlay on the schrank illustrated in fig. 103. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Cradle, possibly made for Anna (Schwar) Shenk, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1770. Walnut and sulfur inlay with tulip poplar. H. 28", W. 30", D. 38". (Courtesy, Clarke Hess; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) One of the pillow panels is missing.

Detail of the inlay on the headboard of the cradle illustrated in fig. 105. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Miniature chest, made for Andreas Bartruff, Manheim, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1775. Walnut and sulfur inlay with tulip poplar; iron. H. 7 5/8", W. 16 1/8", D. 8 5/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the chest illustrated in fig. 107. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, made for Barbara Stauffer, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1790. Walnut and sulfur inlay with white pine; iron, brass. H. 30 1/2", W. 52 1/2", D. 24 1/2". (Courtesy, Salvatore A. Rizzuto; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The feet are replaced.

Detail of the inlay on the chest illustrated in fig. 109. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Schrank, made for Michael and Eva Magdalena Ley, probably made by Christoph Uhler, Lebanon, Lancaster (now Lebanon) County, Pennsylvania, 1771. Walnut and sulfur inlay with tulip poplar and white pine; brass. H. 99 1/4", W. 91", D. 26". (Courtesy, Rocky Hill Collection; photo, Winterthur Museum, Laszlo Bodo.)

Detail of the inlay on the schrank illustrated in fig. 111.

Schrank, probably made by Christoph Uhler (1741–1804), Lebanon, Lancaster (now Lebanon) County, Pennsylvania, 1771. Walnut and sulfur inlay with pine and tulip poplar; iron, brass. H. 91 1/2", W. 86 1/2", D. 26". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the schrank illustrated in fig. 113. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tulpehocken Manor, built for Michael and Eva Magdalena Ley, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, 1769, remodeled 1883, photo ca. 1885. (From Rev. P.C. Croll, Ancient and Historic Landmarks in the Lebanon Valley [Philadelphia: Lutheran Publication Society, 1895].)

Door pediment from Tulpehocken Manor, signed by Christoph Uhler, Lebanon, Lancaster (now Lebanon) County, 1769. White pine; paint. H. 21 3/4", W. 70 1/4", D. 3 3/4". (Courtesy, James C. Keener; photo, Winterthur Museum, Laszlo Bodo.)

Corner cupboard from Tulpehocken Manor, probably made by Christoph Uhler, Lebanon, Lancaster (now Lebanon) County, ca. 1769. Pine and tulip poplar; paint; glass. H. 101", W. 57", D. 40". (Courtesy, Greg K. Kramer and Co.)

Fireplace surround from Tulpehocken Manor, probably made by Christoph Uhler, Lebanon, Lancaster (now Lebanon) County, ca. 1769. (Courtesy, Lynda and Richard Levengood; photo, Lisa Minardi.)

Tall clock, probably made for Henry Eshleman, movement signed by John Heinselman, Manheim, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1795. Walnut and sulfur inlay with tulip poplar. H. 86", W. 18 1/4", D. 10 1/4". (Courtesy, Rock Ford Plantation, bequest of John J. Snyder Jr.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the clock illustrated in fig. 119. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the cornice on the clock illustrated in fig. 119. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the groove for the hood on the clock illustrated in fig. 119. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tall clock, made for “H h,” movement signed by Christian Forrer, Lampeter, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1766. Walnut and sulfur inlay. H. 89 3/4", W. 21," D. 11 3/4". (Courtesy, Ed and Mary Ann Dixon; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the clock illustrated in fig. 123. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tall clock, probably made for Michael Horst, movement signed by George Hoff, Lancaster, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1785. Walnut and sulfur inlay with white pine. H. 84 3/4", W. 22," D. 12". (Courtesy, Clarke Hess; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The base has been shortened.

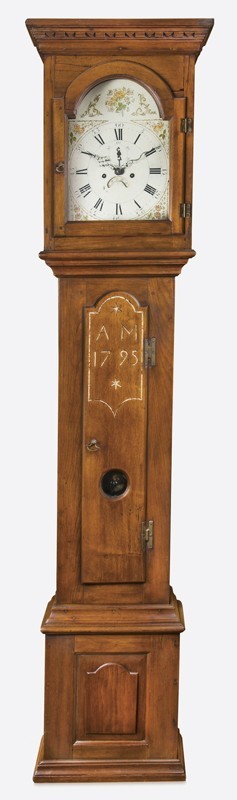

Tall clock, made for “A M,” probably Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1795. Walnut and sulfur inlay with tulip poplar; brass. H. 87", W. 20 1/2," D. 10 3/4". (Courtesy, Carl and Yvonne De Paulis; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the tall clock illustrated in fig. 126. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, probably made for Jacob Ebersole, probably Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1785. Walnut and sulfur inlay; iron, brass. H. 28", W. 52", D. 25". (Courtesy, Leslie Miller and Richard Worley; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

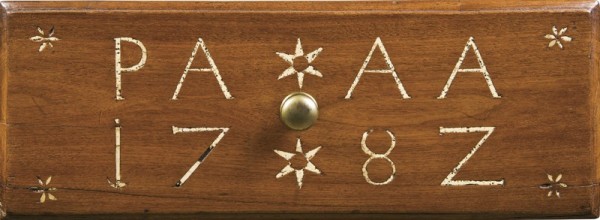

Drawer from a table, made for “PA AA,” probably Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1782. Walnut and sulfur inlay. Dimensions unrecorded. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Schrank, made for Christian and Elisabeth Schneider, probably Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1780. Walnut and sulfur inlay; iron. H. 80 1/2", W. 74", D. 24 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Joseph Schneider Haus.)

Frieze of a schrank, made for John and Mary Mennig/Minnich, probably Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1789. Walnut and sulfur inlay. H. 8 3/4", W. 68 3/4", D. 1". (Courtesy, David A. Schorsch; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Cradle, made for “EV MI,” probably Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1789. Walnut and sulfur inlay. H. 22 3/4", W. 28 1/8", D. 38 3/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, promised gift of David A. Schorsch and Eileen M. Smiles; photo, James Schneck.)

Detail of the inlay on headboard of the cradle illustrated in fig. 132.

Detail of the inlay on the footboard of the cradle illustrated in fig. 132.

House of George and Maria Catharina Miller, Millbach, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, 1752. (Courtesy, Millbach Foundation; photo, Winterthur Museum, Laszlo Bodo.)

Chest, probably made for Eva Koppenhefer, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, 1785. Walnut and sulfur inlay with white pine and tulip poplar; iron, brass. H. 28 1/2", W. 54 7/8", D. 24 3/8". (Courtesy, Philip H. Bradley Co.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the chest illustrated in fig. 136. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Christ Lutheran Church, near Stouchsburg, Marion Township, Berks County, Pennsylvania, built in 1786. (Courtesy, Mr. and Mrs. Michael Emery.)

Chest, made for John Illig, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, 1797. Walnut and sulfur inlay. H. 25", W. 52 1/2", D. 23". (Private collection; photo, Conestoga Auction Co.)

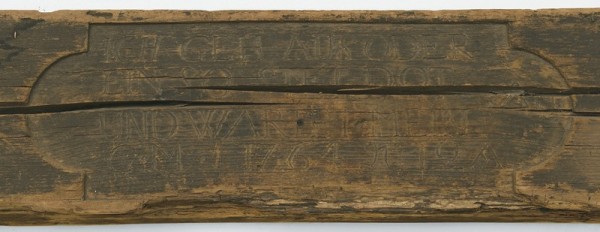

Detail of a door lintel, probably Middletown, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, 1764. Pine. H. 9", W. 40 1/2", D. 5 1/4". (Courtesy, Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, State Museum of Pennsylvania.)

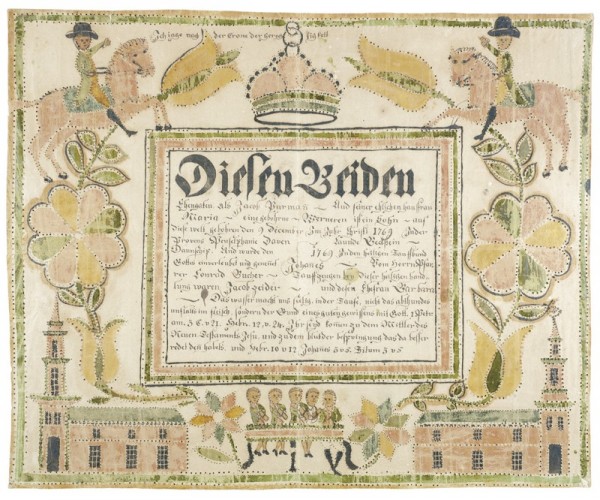

Birth and baptismal certificate, made for Johannes Poorman, Paxton Township, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1785. Watercolor and ink on laid paper. 12 1/2" x 15 1/2". (Courtesy, Susan and Stephen Babinsky; photo, Winterthur Museum, James Schneck.)

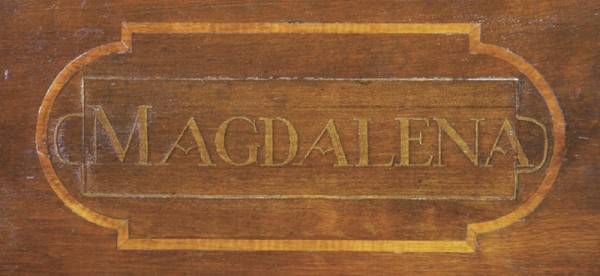

Chest, made for Magdalena Fischborn, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, 1781. Walnut, sulfur inlay, and mixed-wood inlay with pine; iron. H. 27 1/2", W. 52 3/4", D. 24 1/4". (Courtesy, Carl and Yvonne De Paulis; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlaid star on the chest illustrated in fig. 142. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the till compartment of the chest illustrated in fig. 142. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the bracket foot of the chest illustrated in fig. 142. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the glue block of the chest illustrated in fig. 142. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

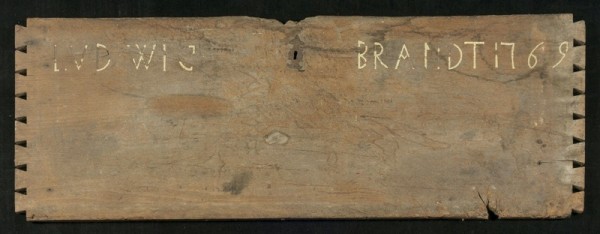

Façade of a chest, made for Ludwig Brandt, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, 1769. Walnut with sulfur inlay; iron. H. 18 3/8", W. 51 3/4", D. 1". (Courtesy, Edward and Linda Rosenberry; photo, Winterthur Museum, James Schneck.)

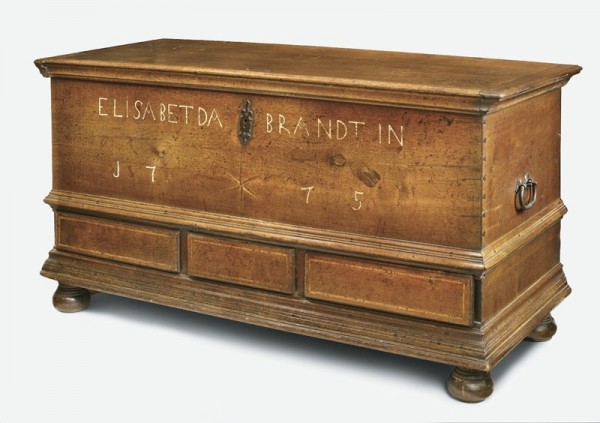

Chest, made for Elisabetha Brandt, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, 1775. Walnut with sulfur and wood inlay and white pine and tulip poplar; iron. H. 30 1/2", W. 58 3/4", D. 25 3/4". (Courtesy, Renfrew Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the till compartment of the chest illustrated in fig. 148. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the hidden drawers of the chest illustrated in fig. 148. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, made for Elisabeth Brua, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, 1776. Walnut, sulfur inlay, and wood inlay with tulip poplar; iron. H. 26", W. 49 1/2", D. 24". (Courtesy, Pook & Pook.)

Chest, made for Henrich Miller, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, 1781. Sycamore, sulfur inlay, and mixed-wood inlay with tulip poplar; iron, brass. H. 27 3/4", W. 54 1/4", D. 24". (Courtesy, Rocky Hill Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Interior of the chest illustrated in fig. 152. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The maker used a sliding batten to stabilize the three-board lid and installed a slanted till compartment.

Side of the chest illustrated in fig. 152. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

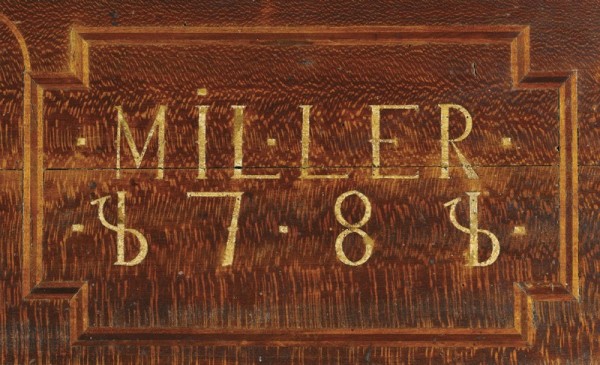

Detail of the inlay on the façade of the chest illustrated in fig. 152. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the façade of the chest illustrated in fig. 152. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, made for Lutwig Fischborn, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, 1783. Walnut, sulfur inlay, and mixed-wood inlay with tulip poplar; brass, iron. H. 27 1/2", W. 51 1/2", D. 23 3/4". (Courtesy, Carl and Yvonne De Paulis; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the chest illustrated in fig. 157. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, made for Maria Klinger, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, 1792. Walnut, sulfur inlay, and mixed-wood inlay with tulip poplar and white pine; brass, iron. H. 27", W. 51 1/2", D. 24". (Courtesy, Rock Ford Plantation, bequest of John J. Snyder Jr.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the chest illustrated in fig. 159. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the chest illustrated in fig. 159. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, made for “CH KM,” probably Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, 1788. Walnut and mixed-wood inlay with tulip poplar; brass, iron. H. 26", W. 54", D. 23". (Courtesy, Clarke Hess; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the star inlay on the chest illustrated in fig. 162. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, made for “ML,” probably Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, 1789. Walnut, sulfur inlay, and mixed-wood inlay with tulip poplar; brass, iron. H. 27 1/8", W. 50", D. 23 3/4". (Courtesy, Mr. and Mrs. Stephen D. Hench; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, made for “IS,” Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, 1790. Walnut and sulfur inlay with tulip poplar; brass, iron. H. 27 1/2", W. 49 1/2", D. 23". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, bequest of John J. Snyder Jr.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, made for “S A C,” probably Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, 1793. Walnut and sulfur inlay with tulip poplar; brass, iron. H. 29 5/8", W. 50 1/2", D. 23 3/4". (Courtesy, Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Landis Valley Village and Farm Museum, bequest of John J. Snyder Jr.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, made for Magdalena Baum, probably Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, 1798. Walnut and mixed-wood inlay with white pine and tulip poplar; brass, iron; paint. H. 27", W. 55 1/2", D. 23". (Courtesy, Historical Society of Dauphin County, Harrisburg, Pa.; photo, David Pickel.)

Detail of the inlay and paint on the chest illustrated in fig. 167.

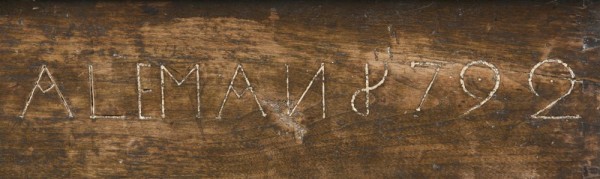

Chest, made for Margaret Alleman, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, 1786. Walnut and sulfur inlay; iron. H. 22", W. 48", D. 24". (Photo, Pook & Pook.)

Chest, made for Martin Alleman, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, 1792. Walnut and sulfur inlay with white pine, tulip poplar; iron. H. 20 1/2", W. 52", D. 24 1/4". (Courtesy, Clarke Hess; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The chest was originally over drawers and has been reduced in height.

Detail of the inlay on the chest illustrated in fig. 170. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

William Wagner, view of York, York County, Pennsylvania, 1830. (Courtesy, York County Heritage Trust, York, Pa.)

Tall clock, made for “A G and AMG,” movement signed by John Fisher, York, York County, Pennsylvania, 1773. Walnut and sulfur inlay. H. 99", W. 17 1/2", D. 11 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Winterthur Library, Decorative Arts Photographic Collection.)

Detail of the clock illustrated in fig. 173.

Desk, made for George Gelwicks, York County, Pennsylvania, 1790. Walnut with sulfur inlay and pine. H. 44 1/4", W. 41 1/4", D. 22". (Private collection; photo, Rob Manko.)

Detail of the inlay on the desk illustrated in fig. 175.

Birth and baptismal certificate for Johannes Gelwicks, decoration and infill attributed to the Pseudo-Otto Artist, printed form attributed to the Ephrata Cloister, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1788. Watercolor and ink on laid paper. 13" x 16". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art, promised gift of Joan and Victor Johnson; photo, Graydon Wood.)

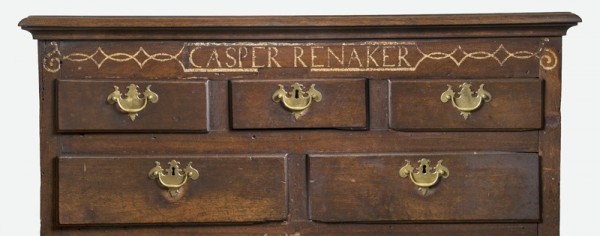

Chest of drawers, made for Casper Renaker, York County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1790. Walnut and sulfur inlay with pine and tulip poplar. H. 51 1/2", W. 41 1/4", D. 22". (Courtesy, Carl and Yvonne De Paulis; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The feet, top, and knobs are replaced.

Detail of the inlay on the chest of drawers illustrated in fig. 178. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tombstone for Michael Gibler, St. Mary’s Church, Carroll County, Maryland, 1791. (Photo, Lisa Minardi.)

Tombstone for Anna Elisabeth Margreth Gibler, St. Mary’s Church, Carroll County, Maryland, 1791. (Photo, Lisa Minardi.)

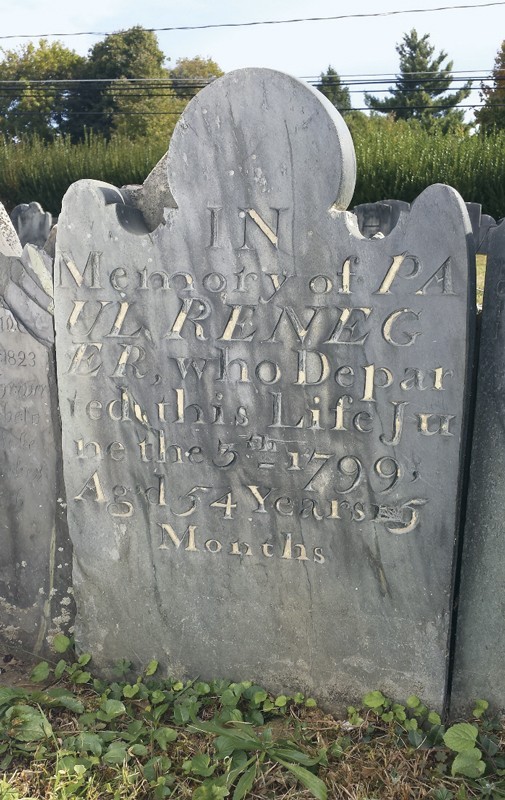

Tombstone for Paul Renecker, St. Mary’s Church, Carroll County, Maryland, 1799. (Photo, Lisa Minardi.)

Chest, probably York County, Pennsylvania, 1789. Yellow pine; paint; iron. H. 22 1/2", W. 49", D. 21 1/2". (Courtesy, Museum of the Shenandoah Valley, Winchester, Va.; photo, Ron Blunt.) The left foot is restored. It is also possible that this chest was made in Shenandoah County, Virginia.

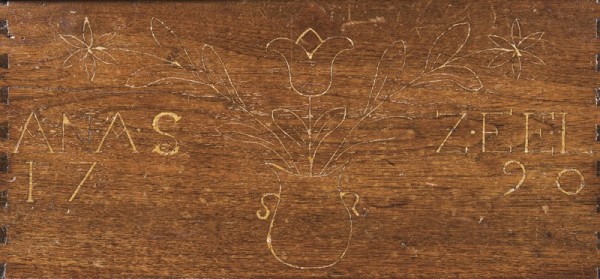

Miniature chest, probably made for Anna Sell/Zell, York County, Pennsylvania, 1790. Walnut and sulfur inlay with pine. H. 11 3/8", W. 19 1/4", D. 11 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the chest illustrated in fig. 184. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

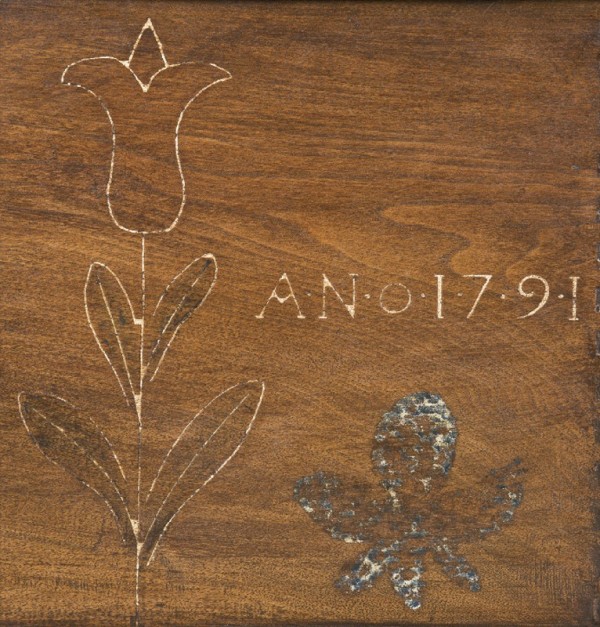

Chest, probably made for Peter Holtzappel, York County, Pennsylvania, 1791. Walnut and sulfur inlay with pine; paint. H. 24 1/2", W. 49", D. 20 1/4". (Courtesy, Clarke Hess; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The feet and base molding are replaced.

Detail of the inlay on the chest illustrated in fig. 186. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tall clock, southeastern Pennsylvania, 1766. Walnut, sulfur inlay, and mixed-wood inlay; secondary woods unrecorded. H. 88", W. 19", D. 10 1/2". (Location unknown; photo, Christie’s.)

Corner cupboard, southeastern Pennsylvania, 1768. Walnut, sulfur inlay, and mixed-wood inlay with tulip poplar and pine; iron, brass. H. 85 1/2", W. 47", D. 22 1/2". (Courtesy, Renfrew Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The upper door is missing.

Detail of the inlay on the cupboard illustrated in fig. 189. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the cupboard illustrated in fig. 189. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

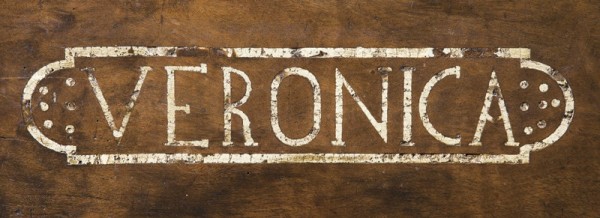

Chest, made for Veronica Miller, southeastern Pennsylvania, 1785. Walnut and sulfur inlay with tulip poplar; iron, brass. H. 20", W. 52", D. 23 3/4". (Courtesy, Clarke Hess; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The feet and base molding are replaced; the chest used to be over two drawers.

Detail of the inlay on the chest illustrated in fig. 192. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the chest illustrated in fig. 192. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Slide-lid box, made for “H D,” probably Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1796. Walnut and sulfur inlay. H. 3 1/4", W. 6 5/8", D. 12". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Slide-lid box, made for “C D”, probably Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1796. Walnut and sulfur inlay. H. 4 3/8", W. 8", D. 13 3/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

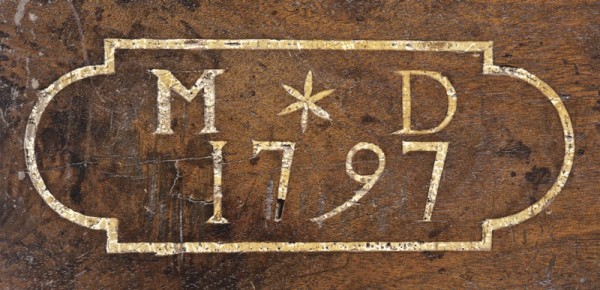

Slide-lid box, made for “M D,” probably Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1797. Walnut and sulfur inlay. H. 4 3/8", W. 8", D. 13 3/8". (Courtesy, Mr. and Mrs. Stephen D. Hench; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the lid of the box illustrated in fig 195. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the lid of the box illustrated in fig 196. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the lid of the box illustrated in fig 197. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

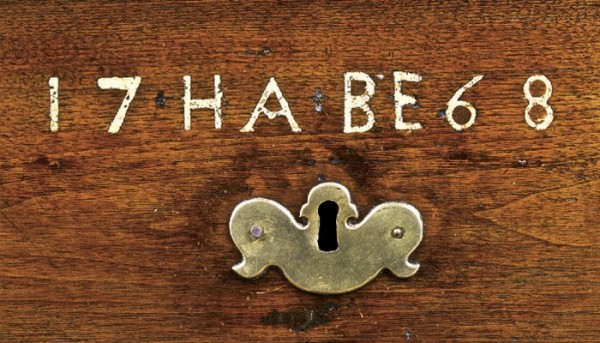

Chest, made for “HA BE,” possibly Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1768. Walnut and sulfur inlay with walnut and oak; brass, iron. H. 27 5/8", W. 48 3/4", D. 22 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The feet are replaced.

Detail of the inlay on the chest illustrated in fig. 201. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Kitchen cupboard, possibly made for Adam and Anna Brandt, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, 1770. Walnut and sulfur inlay with pine and tulip poplar; brass, iron. H. 89 1/2", W. 76 /2", D. 20 3/4". (Courtesy, Rocky Hill Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The pie shelf section and brasses are restored.

Detail of the inlay on the cupboard illustrated in fig. 203. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the cupboard illustrated in fig. 203. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the cupboard illustrated in fig. 203. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Hanging cupboard, probably Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1772. Walnut and sulfur inlay with pine. H. 33", W. 18", D. 11 7/8". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1953-125-9; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The bottom lip of the drawer is replaced.

Detail of the inlay on the cupboard illustrated in fig. 207. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the cupboard illustrated in fig. 207. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

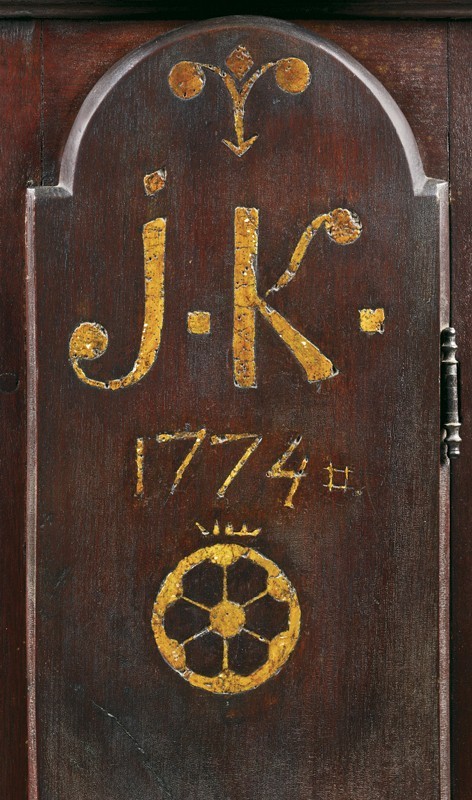

Tall clock, made for “J.K.,” movement signed by George Hoff, probably Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1774. Walnut and sulfur inlay with tulip poplar. H. 86 3/8", W. 20", D. 10 1/8". (Courtesy, Philip H. Bradley Co.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The feet are replaced and the inlay is restored.

Detail of the inlay on the clock illustrated in fig. 210. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tall clock, made for “H.S.,” movement signed by Jacob Gorgas, Ephrata, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1790. Walnut and sulfur inlay with tulip poplar. H. 95 1/2", W. 23 1/2", D. 12 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the clock illustrated in fig. 212. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Table, possibly Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1790. Walnut and sulfur inlay; brass. H. 30", W. 41", D. 29 1/2". (Courtesy, Carl and Yvonne De Paulis; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Slide-lid box, made for “W B,” probably Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1790. Walnut and sulfur inlay with pine. H. 5", W. 11 3/4", D. 5 7/8". (Courtesy, Rocky Hill Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

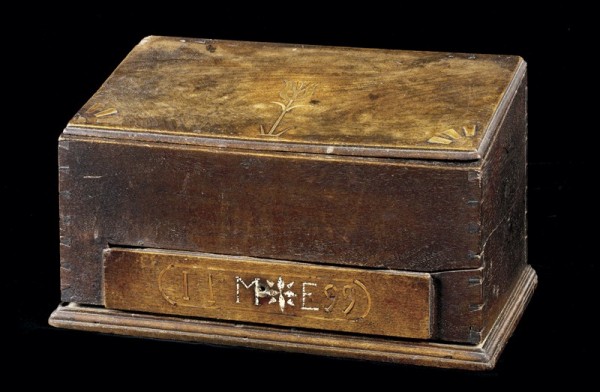

Box with drawer, made for “M E,” probably Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1799. Walnut, sulfur inlay, and mixed-wood inlay with tulip poplar; brass. H. 9 1/4", W. 18", D. 8 3/4". (Courtesy, Rocky Hill Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

In December 1929 antiques dealer Hattie Brunner of Reinholds, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, wrote to Henry Francis du Pont offering an enticing object for sale:

Am enclosing photo of a miniature chest which I bought last week, out of the original family, who had cherished it all these years, always kept it stored in a large chest, is in wonderful condition for the age. A unique piece. Dated 1773 made by Johannes Mosser who was one of the first settlers in this section. Was a shoe maker by trade. The old lady that owned it gave me the whole history of the piece . . . . It was inlaid with the same old putty as that walnut Kass [schrank] I sold you this spring. Will send it on approval if interested.

Du Pont complained about the $1,000 asking price but bought the chest anyway (figs. 1, 2). What neither he nor Brunner realized was that the “putty” inlay on the chest and schrank (see fig. 34) was in fact sulfur—a material used by Pennsylvania German craftsmen in southeastern Pennsylvania from at least 1763 to 1801 and for several decades later in the South. For years this inlay was described as putty or wax, as Frances Lichten claimed in 1960 when she wrote that it was made of “humble substances: powdered white lead and beeswax” and referred to the technique as Wachseinlegen or wax inlay. It was not until analytical work was undertaken in the 1970s at the behest of Smithsonian curator Monroe Fabian that the inlay was correctly identified as sulfur. In Fabian’s 1977 article on the subject, he claimed to have located twenty-two examples of sulfur-inlaid furniture. Subsequent work by Clarke Hess later identified many more pieces owned by Mennonite families in Lancaster County. Analytical work by Mark Anderson and Jennifer Mass at Winterthur Museum has also yielded new insights into the materials and techniques of making sulfur inlay. More than 125 examples of sulfur-inlaid furniture can now be documented from Pennsylvania, as well as from Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina; they range in date from 1763 to 1844. The majority are chests, tall clocks, and schranks; other known forms include slide-lid boxes, miniature chests, corner cupboards, hanging cupboards, kitchen cupboards, tables, a slant-front desk, and even a straightedge.[1]

Brunner’s letter typifies some of the other challenges that have plagued efforts to research sulfur-inlaid furniture. Although she claimed to have acquired the miniature chest out of the “original family” and to have its “whole history,” no further information was ever provided to du Pont. Like so many other objects, the chest lost its provenance once it was removed from the family in which it had descended. Thankfully, many pieces of sulfur-inlaid furniture include the owners’ names, or at least initials, and dates that offer clues as to their points of origin. Based on this information, sulfur inlay can now be documented in Lancaster, Lebanon, Dauphin, and York counties, Pennsylvania (fig. 3). The following article is an attempt to reconstruct the origins of the various major groups as well as individual examples of Pennsylvania German sulfur-inlaid furniture. In many cases, the owners’ names are unique or sufficiently unusual that they can be identified with certainty. In other cases, especially for those pieces bearing only initials, educated guesswork must be used to make tentative identifications. Depending on the level of certainty, this article will use the modifiers “probably” or “possibly” to indicate when attributions of ownership or maker are less than certain.

In the case of the miniature chest acquired by du Pont, the presence of an owner’s name, “Johannes Mosser,” and the date 1773 inlaid on the lid provide a starting point for investigation. Brunner’s letter also claims that Mosser was “one of the first settlers in this section,” implying that he lived somewhere near her antiques shop in Reinholds, located in West Cocalico Township, Lancaster County, near the Lebanon County border. Armed with this information, a search of local church records offers some promising leads. A Johannes Mosser/Moser is mentioned numerous times in the baptismal records of John Waldschmidt, a German Reformed minister who served in the Cocalico region from 1752 to 1786. In 1780 and 1782 Johannes Moser and his wife, Anna Elisabeth, served as baptismal sponsors; on both occasions she is identified as the daughter of Christian Eschelman. In 1785 Johannes and Anna Elisabeth had a son, Johannes Jr., baptized by Waldschmidt. Waldschmidt also confirmed a Johannes Mosser (possibly the same one) in 1775 at the Cocalico church “at Michael Amweg’s” (the German Reformed congregation also known as Little Cocalico or Swamp, located in what is now West Cocalico Township). Given the close proximity of this church to the Reinholds area in which Brunner’s shop was located and her claim that Mosser had lived locally, it is probable that this Johannes Mosser was the original owner of the box.[2]

European Origins: Ivory, Orpiment, and Metallurgy

Before turning to examine the use of sulfur inlay in Pennsylvania German furniture, some investigation of the European origins of this decorative technique is needed. The contrast of light and dark was one of the foremost design concepts of the baroque era. At the same time, exotic materials such as ebony and ivory were becoming increasingly accessible to Europeans. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, elaborate furniture in which light-colored inlay was used in contrast with dark woods became fashionable. Possibly as a less expensive alternative to such precious materials, arsenic sulfide, or orpiment, was also used to achieve a similar visual effect. Although highly toxic, orpiment was used for medicinal purposes, to remove hair from hides as part of the tanning process, and as a gold-colored pigment for paint and sealing wax. Formed by the crystallization of sulfurous gases emitted from volcanic fumaroles, orpiment was especially prevalent in Italy, home to the only active volcanoes in mainland Europe. Several examples of Italian furniture inlaid with orpiment have been identified, including a Venetian prayer bench and a small Bolognese chest dating to the mid-1500s (figs. 4, 5). Mining sulfur ore was once very common in Italy, especially in Sicily, but also in places such as Naples, Campania, Formignano near Cesena (mined for nearly 500 years), and Perticara near Novafeltria (mined from about 1741 to 1964). In 1864 it was estimated that there were 615 sulfur mines in Italy, of which 237 were abandoned because their ore was already extracted. During that time Sicily’s mines alone produced more than 157,000 tons of sulfur per year.[3]

Sulfur has long been used in a variety of trades, especially metalworking. Its properties of melting at a relatively low temperature (about 240°F) and hardening to a solid, yellowish material would have been widely known to craftsmen. Sulfur was also used for bleaching wool, silk, and even hair and was an essential ingredient in gunpowder. Numerous references to sulfur in newspaper advertisements, diaries, and probate inventories reveal that the mineral was commonly available in southeastern Pennsylvania during the 1700s. In 1746 the Pennsylvania Gazette ran an advertisement from two Philadelphia merchants offering for sale “just imported” fabrics, buttons, sewing supplies, pigments and dyestuffs including “red lead, white lead, Spanish brown, Spanish whiting, madder, ground redwood, allom, copperas, brimstone, sulphur, saltpetre, hammers, augers, files, gimlets” and various types of locks. In 1769 weaver George Michael Kettner of Tulpehocken Township, Berks County, had “brimstone” or sulfur listed in his estate inventory. Daniel Hiester Sr. of Berks County owned a “half Barrel with a quantity of Brimstone” valued at £3 when he died in 1795. Sulfur is also mentioned several times in the journals of Lutheran minister Henry Muhlenberg of Philadelphia and Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. In 1777, Muhlenberg reported with skepticism that his wife Anna Maria took a “mixture of molten sulphur and steel” in an attempt to treat her epileptic condition. “One takes a piece of raw sulphur and a piece of glowing steel,” Muhlenberg noted, “the two are held over a pan of water and allowed to drip in; afterwards it is made into a fine powder. Now and then an amount that can be placed on the point of a knife is taken with honey or molasses.” He also recorded purchases of sulfur, paying 3s. 9d. in 1777 for a half-pound of sulfur and 1s. 3d. “for steel to strike fire and for sulphur sticks.” In all likelihood, Pennsylvania German cabinetmakers turned to sulfur inlay as a less expensive and more readily available substitute for ivory or orpiment. Once the sulfur was inlaid into a native wood such as black walnut or cherry, it provided a similar light and dark effect. Given that it was inlaid in a molten state with the excess simply scraped away after it cooled, sulfur inlay also saved time. And unlike orpiment, sulfur inlay was not toxic.[4]

The technical process for using molten sulfur as an inlay is rooted in metalworking. A brief survey of early metallurgical publications reveals numerous German and Italian sources. Studies by German scholars were especially prominent due in part to the prevalence of ore deposits and mining in Germany; there was also significant pressure to develop new metalworking techniques due to the influx of metals from South American mines after 1492. One such early metallurgical manual, Das Bergbüchlein (Augsburg, 1505), explains how to locate and work veins of ore. A 1556 study by Georg Bauer (also known as Georgius Agricola), De re metallica (On the Nature of Metals), focused on mining, assaying, and smelting; it also includes a section on purifying sulfur that was derived in large part from the earlier and highly influential book De la pirotechnia, first published in Venice in 1540 and illustrated with dozens of woodcuts depicting various aspects of metalworking. A direct link between Pennsylvania German sulfur inlay and European metallurgy can also be established through the Pirotechnia, which very likely served as the design source for the fleur-de-lis motif that is a particular hallmark of the earliest known examples of sulfur-inlaid furniture, made during the 1760s and 1770s in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. Although the fleur-de-lis motif is often associated with the French, leading some to speculate that the furniture’s owners or makers were French Huguenots, most of the owners were in fact of Swiss-German Mennonite heritage. However, the fleur-de-lis was also a popular motif in Italy. Best known as the symbol of the city of Florence, the fleur-de-lis was also used in papal crowns and by the doges of Venice and dukes of Parma. The title page of the 1559 edition of De la pirotechnia—which was printed in Venice—features three large fleur-de-lis motifs nearly identical to those inlaid in sulfur and carved on Lancaster County furniture more than 200 years later (figs. 6-8).[5]

The earliest known European manual on metallurgy, the Pirotechnia was written by Vannoccio Biringuccio (1480–ca. 1539), who is often considered the father of the foundry industry. A native of Siena, Biringuccio was appointed head of the papal foundry and director of munitions in 1538. The treatise is divided into ten books on topics such as minerals, assaying, smelting, separating gold from silver, alchemy, and the art of casting metals. Book 2 contains a chapter on sulfur, which begins with the statement “Sulfur is a very well-known mineral” and then describes how to purify sulfur ore by heating it in ceramic vessels with a spout near the top, through which the sulfur is distilled by means of ceramic tubes into a second vessel. After applying a “good and powerful flaming fire” to the vessels containing the crude ore, Biringuccio writes that the “substance that is in the ore . . . passes like a smoke through the tubes, thickens there and becomes sulphur; when it becomes like melted wax, it falls to the bottom. If the master wishes, he causes it to run out as it forms . . . to form a cake or else it is poured into tubes of cane, wood, or terra cotta.” He ends the chapter: “To conclude: As I told you, sulphur melts and by means of its fusion one can mould any desired object from it as if it were plaster of Paris, wax, or melted metal.” There is also a short chapter on arsenic and orpiment that describes them as a “most powerful poison to the life of all things” and advises against using them “except by force of necessity.” Although it is not certain exactly how Lancaster County craftsmen would have accessed this manual, it is possible that a copy was in the collection of the Lancaster Library Company, established in 1759 and renamed the Juliana Library Company in 1763. In 1766, the library moved to the home of the Moravian gunsmith William Henry (1729–1786). As a gunsmith, inventor, patron of the arts (including the painter Benjamin West), and member of the American Philosophical Society, Henry is a likely person to have owned a copy of the Pirotechnia (fig. 9). He is known to have had an extensive personal library at the time of his death in 1786. Even if Henry could not read Italian, the dozens of woodcuts showing various aspects of metalworking would no doubt have been useful.[6]

Lancaster County

The use of sulfur-inlaid decoration on Pennsylvania German furniture appears to have originated in Lancaster County. The earliest known dated example is a schrank made in 1763 for Christian and Veronica Herr; the latest known is a chest dated 1801 (see figs. 19, 98). The majority of Lancaster County sulfur-inlaid furniture can be divided into one of three major groups. The earliest group, dating to the 1760s and 1770s, includes at least fifteen tall clocks, schranks, and chests decorated with varying combinations of sulfur, mixed wood, pewter, and even bone inlay. Common design elements include fleur-de-lis motifs and heart-shape, foliate cartouches that frame the owners’ names or initials and dates; some pieces also have crossbanded wood inlay in geometric shapes. Highly sophisticated in their design and execution, these pieces were probably made in the county seat of Lancaster, although the original owners lived throughout central Lancaster County. Additional sulfur-inlaid furniture was owned by some of the same families but appears to be the work of various other makers. The second group consists of a pair of chests made in or near Manheim Township in the early 1780s. The third group ranges in date from 1781 to 1801 and includes three full-size chests and a miniature chest, tall clock, stretcher-base table, and straightedge ornamented with floral and bird motifs, dates, and initials.

The Pequea and Conestoga Settlements

One of the earliest settlements in what is now Lancaster County was founded by a small group of Swiss-German Mennonite families about 1710, when some 10,000 acres was warranted to Hans Herr, Christian Herr, Martin Kindig, Jacob Miller, Martin Oberholtzer, John Funk, Hans Graff, Wendell Bauman, Martin Mylin, Christopher Franciscus, and Michael Oberholtzer. The land was located in the Pequea Valley of what was then western Chester County. In 1719 Christian Herr, a Mennonite bishop, built a substantial stone house that also served as a meetinghouse until 1849 (fig. 10). The Conestoga settlement soon grew to such an extent that in 1729 the inhabitants successfully petitioned the legislature to establish a new county. The county seat, also known as Lancaster, was laid out in 1730 some ten miles east of the Susquehanna River, near the Conestoga Creek. In 1742 the town of Lancaster was officially incorporated as a borough; it did not assume the legal status of a city until 1818 (this article will use the term “Lancaster” to denote the town/borough). Despite its English name, Lancaster was a predominantly German-speaking locale from the very start. Seventy-five percent of the lot holders in 1740 were Germans; in 1759 about 67 percent of the town’s population was German and in 1789 about 63 percent was German. Within twenty years of Lancaster’s founding there were 311 taxpayers, and by 1775 its population was approximately 3,288—making Lancaster the largest inland town in America at the time. As the town prospered, its architectural landscape also became increasingly sophisticated. From 1761 to 1766 the Lutheran congregation built a large brick church, Trinity Lutheran, and in 1794 they added a steeple tower adorned with statues of the four evangelists. In 1787 a new brick courthouse was completed, which also served as the Pennsylvania State House when Lancaster was the state capital from 1799 to 1812 (fig. 11).[7]

Early Lancaster Furniture

Lancaster’s German-speaking inhabitants included many talented woodworkers as well as affluent consumers who demanded furniture of the best sort. One of the earliest known dated objects associated with Lancaster is an extraordinary tall clock made in 1745 for Andreas Beierle (Andrew Beyerle) and his wife Catharina (figs. 12-14). Adorning the hood are two finials in the shape of reclining putti or cherubs, while the pendulum door is carved with a baroque floral design and symbols representing Beierle’s trade as a baker: a pretzel and loaves of bread. Born in Rohrbach im Kraichgau, Germany, in 1713, Andreas immigrated in 1738 and settled in Lancaster by 1743, when he and his wife served as the sponsors for two baptisms at Trinity Lutheran Church. His training as a master baker in Europe would have included mold carving (necessary for making gingerbread, marzipan, and various fancy pastries), and thus it is possible that Andreas did some of the carving on the clock case himself. In 1754 Andreas and his family moved to Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania; he served as a baker for the army during the French and Indian War and died in 1781. The same person who carved the floral designs on the clock case probably also executed the ornament on an undated paneled walnut chest and a fireplace mantel with a central plaque dated 1746, flanked by rampant lions (fig. 15).[8]

Another early and impressive example of Lancaster-made furniture is a schrank with the pewter inlaid inscription “MF AMF ANNO 1758” (fig. 16). The original owners were probably Michael Fordney (Fortineux) and his wife Anna Margaretha Freuler of Lancaster. Of French Huguenot heritage, Fordney was born in 1714 in Landstuhl in the Palatinate. He immigrated in 1737 together with two of his brothers; their parents and several more siblings joined them by 1742. Michael was a butcher by trade and rented a stall in the Lancaster market house during the 1750s. His father-in-law, Jost Freuler, was Swiss and a gunsmith by trade. Freuler, his wife, and seven children emigrated from Germany to Pennsylvania in 1738, and by 1740 he was an active member of Lancaster’s First Reformed Church. Between 1754 and 1762 four of Michael and Anna Margaretha Fordney’s children were baptized at First Reformed Church, and in 1769 Michael became a trustee. In his will, Michael left detailed instructions for the distribution of his two town houses, several plots of land, and a brick house and property in Manheim. Michael died in 1778, survived by his widow and three children: Casper, Henry, and John. A great-nephew, Melchior Fordney (1781–1846), was a famous gunsmith in Lancaster prior to his grisly murder at the hands of an axe-wielding religious fanatic. Two years after the Fordneys’ pewter inlaid schrank was made, Johannes and Anna Maria Spohr of Lancaster received a schrank of similar form but embellished with relief-carved floral decoration and baroque inlay on the two doors (fig. 17). Born in 1725, Johannes was thirty-five years old when the schrank was made. His oldest child, John George Spohr, was born in 1749 and baptized at First Reformed Church in Lancaster.[9]

During the 1770s and 1780s Lancaster woodcarvers also produced some of the most sophisticated carved rococo furniture made outside of Philadelphia. One of the most elaborate pieces is a mahogany high chest that was owned by Matthias Slough of Lancaster (fig. 18). A wealthy tavernkeeper and elder at Trinity Lutheran Church, Slough also served as the Lancaster County coroner (1754–1769), and as a member of the Pennsylvania Assembly (1773–1776 and 1783–1784). He was also the largest slaveholder in the borough, with five enslaved servants in his possession in 1782. Profuse, relief-carved foliate designs cover the tympanum and skirt of Slough’s high chest, carved from the solid wood in the Germanic manner rather than made separately and applied. During the 1760s and 1770s several of Lancaster County’s iron furnaces also cast five- and six-plate stoves using rococo patterns carved by Philadelphia artisans. These and other objects provide a broader context for the study of Lancaster County furniture, especially the earliest group of sulfur inlay, which in all likelihood was made in the borough of Lancaster.[10]

Early Lancaster County Sulfur-Inlay Group

The earliest and largest group of sulfur- and related inlaid furniture made in Lancaster County includes more than twenty objects, consisting of schranks, chests, and clocks. Variations within the group—such as the occasional use of pewter inlay, bone inlay, and crossbanded geometric designs—suggest that several craftsmen or workshops may have been involved in the production of this furniture. The following survey of this group is arranged primarily by form and then chronologically within each category to facilitate comparisons among like types of furniture.

Schranks

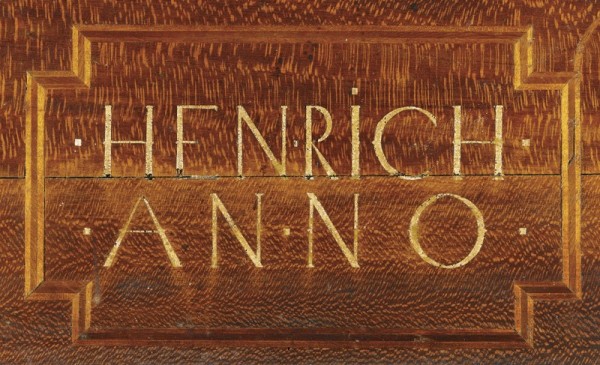

During the 1760s and 1770s at least five walnut schranks with sulfur inlay and carved fleur-de-lis motifs were made by the same unknown craftsman for couples living in central Lancaster County (figs. 19-21). A sixth example is neither inlaid nor dated but has carved fleur-de-lis motifs and is otherwise nearly identical (fig. 22). As discussed above, the design source for this motif is almost certainly the title page of the 1559 edition of De la pirotechnia (see fig. 6). The maker of the schranks used a small, star-shape punch to mat the ground surrounding the relief-carved fleur-de-lis motifs (fig. 23). A similar technique was used on both German furniture and architectural woodwork, as seen in the paneled door of a 1730s building in Hildesheim, Germany (fig. 24). Many of the schranks’ original owners lived in Manor or Hempfield townships (the latter divided into West and East Hempfield townships in 1817), where a log meetinghouse was constructed in about 1740 by the local Mennonite community (fig. 25). Although the Mennonites are known for their use of plain clothing, humble speech, and spare meetinghouses rather than ornate churches, their furniture was often quite elaborate—especially the fine walnut schranks embellished with sulfur-inlaid decoration.[11]

Like most Pennsylvania German schranks, the examples in this group were made to disassemble into pieces. A distinctive feature of this group is that the sections are held together by wrought iron hooks rather than wedged tenons (fig. 26). Otherwise the schranks display typical Germanic construction techniques, including the use of pegged up drawer bottoms and wedged dovetails. On the interior, shelves for storing folded linens are usually located on the left and wooden pegs for hanging clothing on the right. Some of the schranks also have secret compartments hidden between the drawers. On occasion, one of the drawers is divided into smaller compartments. The drawers are constructed of hefty stock, often a full inch in thickness, and some use walnut for the drawer sides. The schrank doors hang on castle-type hinges, made of either iron or brass. On all of the schranks, the husband’s name or initials is inlaid on the upper left door panel and the wife’s name or initials on the upper right. The inscriptions also include an exact date (month, day, and year), although the placement of the dates varies; on some schranks the year is on the left and the month and day on the right, and on others just the opposite occurs. Contrary to popular misconceptions, schranks were usually not made for newlyweds but rather for well-established couples. The inlaid dates do not correspond to marriage dates but in all likelihood are the dates of the schranks’ completion or presentation. The amount of inlaid and carved decoration varies from piece to piece, with some examples being significantly more elaborate than others. Another variable is the presence of a center foot; the earliest schrank, dated 1763, never had one (see fig. 19) but the other four do.

The earliest known example of sulfur-inlaid furniture made in America is the schrank dated April 7, 1763, and inscribed for Christian and Veronica Herr (see fig. 19). The upper left panel bears Christian’s name and the year 1763 framed within a foliate cartouche; the upper right panel contains Veronica’s name, the date April 7, and a pair of small birds and a winged angel head above and below the cartouche. This schrank was probably made for Christian Herr (d. 1811) and his first wife, Veronica Bachman; after her death Christian married Catharine Eyeman (d. 1831). Christian Herr lived in Manor Township and owned a sawmill; in his will of 1811, he bequeathed “one wild cherry clothespress with all the contents thereof” to Catharine as well as three feather beds, a chest, a kitchen dresser and its contents, and £1,000 in gold or silver specie. In an earlier will, written in 1796 but never recorded, he bequeathed to Catharine “my Cloths Press standing in the upper story of my House” along with three beds, a kitchen dresser, and a house clock. Of particular note is that he also bequeathed “unto the said Emanuel Herr Junior my Clothes Press standing in my chamber” along with a ten-plate stove and a dining table of cherry wood. Given that Christian Herr owned a sawmill and identified certain pieces of furniture as being made of cherrywood, it is unlikely that he would have confused the wood of the schrank. Thus, the schrank he bequeathed in the 1796 will to Emanuel Herr Jr. (his nephew) was in all likelihood the sulfur-inlaid walnut schrank, which was transferred to Emanuel prior to Christian’s death in 1811 and thus not mentioned in his last will and testament. It remains in the possession of Herr family members to this day.[12]

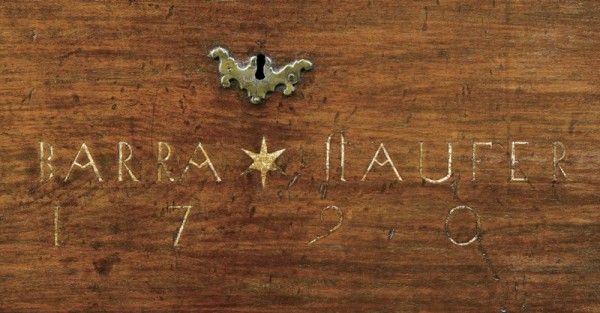

The next schrank in the group bears the date March 1, 1766, and the names “IH KAUFFMANN” and “AN KAUFFMANNIN” (figs. 27-29). In all likelihood, the original owners were Johannes and Anna Kauffmann; the “–in” at the end of Anna’s surname is a German feminine suffix used on women’s surnames, both married and unmarried. The schrank also bears the name of a later owner, “C. L. Nissly,” and the date 1949 on the top, as well as the inscription “C.L. Nissly, 255 Marietta Pk., Mt. Joy PA.” written on the side of a drawer. Closely related in overall form and decoration to the 1763 Herr schrank, the Kauffmann schrank is further embellished with inlaid geometric designs on the lower door panels (fig. 30). John Kauffmann married Anna Shwahr/Schwar, who was probably the daughter of Christian Shwahr Sr. (d. ca. 1784) of East Hempfield Township. Either Christian Sr. or his son Christian Jr. (d. 1807) was the original owner of a sulfur-inlaid tall clock, dated January 18, 1766—a little over a month before the date on the schrank (see fig. 63). In 1775 John Kauffmann and Abraham Reist (owner of the schrank illustrated in fig. 38) served as co-executors of the estate of Jonas Nolt of Hempfield Township. Various John Kauffmanns were named as sons in the wills of Christian Kauffmann (d. 1798), Christian Kauffmann (d. 1806), and Jacob Kauffmann (d. 1812), all of Manor Township, and of Christian Kauffmann (d. 1816) of Hempfield Township.[13]

The third schrank is more restrained in its ornament. It retains the fleur-de-lis carving in the corners of the raised panel doors but lacks the sulfur-inlaid cartouches and bears only the date—February 27, 1767—and the initials “P BM” and “M BM” (figs. 31-33). The original owners have been identified as Peter Bachmann (1725–1782) and his wife Maria of Manheim Township, Lancaster County; a walnut schrank was listed in the inventory taken at Peter’s death. Of Swiss Mennonite heritage, Peter married Maria/Mary Kauffman (ca. 1736–1805), daughter of Jacob Kauffman Sr. of Hempfield Township. In 1781, Peter Bachmann and his brother-in-law, Jacob Kauffman Jr., served as co-executors for the estate of Benjamin Eshelman (brother of Jacob’s wife, Barbara Eshelman) of Hempfield Township.[14]

The fourth and most elaborate of the schranks in this group is dated February 17, 1768, and inscribed for Emanuel and Mary Herr (figs. 34-36). Like the 1766 Kauffmann schrank, it has sulfur-inlaid geometric designs in the lower door panels. The inlay in the upper door panels is slightly different, however, as the cartouche framing Emanuel Herr’s name is topped by a figure of a large parrot eating a tulip. This schrank is also the only one of the group that has an interrupted cornice—a more sophisticated architectural treatment—and relief-carved medallions flanked by turned, engaged columns in the base (fig. 37). The original owners were Emanuel Herr (1745–1828) and his wife Mary. Although most schranks were made for well-established couples rather than newlyweds, this one is an exception since Emanuel Herr was only twenty-three when it was made. Family circumstances likely explain this anomaly, as Emanuel’s father Christian Herr (1720–1763) died when he was only forty-three, and his children consequently received their inheritance at a younger-than-normal age. Emanuel Herr’s sister, Maria, married John Bachmann, brother of the Peter Bachmann for whom the schrank illustrated in figure 31 was made.[15]

Following the 1768 Herr schrank, there is a gap of seven years before the manufacture of the schrank dated March 8, 1775, and inscribed for Abraham and Elisabeth Reist of Warwick (now Penn) Township, Lancaster County (figs. 38-42). Of similar overall form to the previous examples, the Reist schrank has the fleur-de-lis carving but the sulfur inlay is greatly simplified, consisting of small six-point stars, diamonds, and hearts rather than the foliate cartouches, parrots, and winged angel heads. The schrank was commissioned by the Reists to furnish their new home, a large stone house built in 1774 on what is now Fruitville Pike. Abraham Reist (1737–1813) married Elisabeth Kauffman (1739–ca. 1780); her brother John Kauffman owned a sulfur-inlaid schrank made in 1764 (see fig. 99). His second wife was Elisabeth Metz (1739–1810). Abraham lived on the upper tract of his father Peter Reist’s farm in Lancaster County, where Abraham became a wealthy farmer and distiller. He also acquired extensive landholdings in Waterloo Township, Ontario, where the couple’s eldest son, John Reist, later settled. In 1786 Abraham and Elisabeth’s daughter, Elisabeth Reist (1769–1847), received a painted chest prior to her marriage to John Schwar; the vertical dividers between the two drawers echoes the so-called linen fold panel common on many Lancaster County schranks.[16]

Chests

Two painted chests and three sulfur-inlaid chests are related to this group of schranks. The painted chests, which are built out of pine, have engaged quarter columns and carved fleur-de-lis motifs in the corners of the raised panels on the façade and, in the example built over drawers, on the ends (figs. 43-45). Although both chests have been repainted, traces of the original red, white, and blue palette remained on both examples prior to restoration. The chest over drawers also has elaborate wrought iron hinges with pierced terminals (fig. 46). On the three sulfur-inlaid chests, fleur-de-lis motifs project from both sides of the cartouches, echoing the carved versions on the schranks. The earliest example is dated 1765 and bears the initials “M K” (figs. 47, 48). The owner has been identified as Michael Kauffman (1745–1816), youngest child of John Kauffman (ca. 1700–1759) and Anna Bamberger, whose farm lay adjacent to the Landisville Mennonite Meetinghouse in East Hempfield Township (see fig. 25). The year after he received the chest, Michael Kauffman married Veronica Berg (1746–1813), daughter of Mennonite émigré Andrew Berg. Michael inherited a 220-acre plantation at the age of twelve; he became a farmer and also a physician.[17]

The next chest, which is virtually identical, is dated 1766 and bears the initials “D W” (figs. 49, 50). It is constructed almost entirely of walnut, including all visible parts of the till compartment. The till has a false bottom; by pulling up on the front board of the till, a shallow compartment with drawer is revealed. Written on the bottom of the drawer is the name of a later owner: “John C. Sadler Hopewell Township York Co. Pa.” A probable candidate for the original owner is Daniel Wolf; his father John Nicholas Wolf emigrated from Germany in 1738, married Anna Maria Bower, and settled in what is now East Hempfield Township, where he died in 1771. Daniel Wolf was born on August 25, 1752, and baptized on September 22 at First Reformed Church in Lancaster; five of his siblings were also baptized there between 1754 and 1769. A store- and tavernkeeper, Daniel Wolf founded the town of East Petersburg, Lancaster County, in 1812. Other surnames beginning with W listed on the 1758 tax assessment for Hempfield Township include Weller, Whitman, Welty, Walter, Whitmore, Wagoner, Wright, Weaver, Waltz, and Weldy.[18]

The third chest is the most elaborate example of the 1760s group. It is dated 1768 and inscribed with the initials “I D” (figs. 51, 52). The only surnames beginning with D on the 1758 Hempfield Township tax list are Dowenbark (probably Dowbenberger), Deyeman, and Davis. In Manor Township in 1780, the surnames include Derstler, Dercher, Domini, Dunckle, and Dundore. A Johannes Dunckel, born in 1747 to Swiss émigré Melchior Dunckel (1701–1769) and his wife Anna Barbara, is one possible candidate whose initials and life dates correspond to the chest. A unique feature of this chest is the pair of mirror-image foliate framing devices that flank the central cartouche (fig. 53). The large ogee bracket feet (fig. 54) are also not found on any of the other chests or schranks, but they relate closely to the original, albeit more diminutive, ogee feet on a sulfur-inlaid tall clock made in 1765 (see fig. 61).[19]

Clocks

At least eight tall clocks are known with closely related cases (several built of cherry rather than walnut) and inlaid ornament including sulfur, pewter, and wood. The earliest example is dated 1762 and has the initials “FR ST” inlaid in pewter in the hood; bands of pewter also encircle two of the finials and additional pewter inlay is on the plinth blocks (figs. 55, 56). Within the arcs of the inlay are clearly visible compass points made by the craftsman as he laid out the design. The pewter was poured into the wood in a molten state, as evidenced by tiny areas in which it leaked beyond the confines of the incised channels. Pewter inlay is extremely rare in Pennsylvania German furniture. Other than this clock, two other clock cases (see fig. 65), and the 1758 schrank (see fig. 16), there are only two or three known examples with pewter inlay. Both pewter and sulfur have a relatively low melting point (depending on its composition, pewter melts between 338–446°F; sulfur melts at about 240°F), enabling them to be poured directly into the wood as an inlay material. The clock case (fig. 57) is inlaid with crossbanded wood strapwork in geometric designs, outlined in pewter stringing; it houses an eight-day, arched dial movement signed by Rudolph “Rudy” Stoner (1728–1769) of Lancaster. A Moravian, Stoner is one of the first documented clockmakers in Lancaster County, where he appears in the borough tax lists by 1754. He purchased a brick house just north of Center (now Penn) Square by 1760, but his life was cut short at the age of forty. The inventory of his estate, valued at £604.19.2, includes fine furniture, a clavichord and two violins, and a workshop full of highly specialized equipment—including clock- and watchmaking tools, a “Cutting Engine for Watch work,” polishing and fusee engines, clock and watch parts, and lead patterns.[20]

The pewter inlay on the clock case may have been provided by Johann Christoph Heyne (1715–1781), who, like Stoner, was a Moravian. A talented pewterer, Heyne immigrated to Pennsylvania in 1742 and worked in Lancaster from 1752 to 1781. After the death of his first wife in 1764, Heyne married Anna Regina Steinman, herself a widow who had moved from Bethlehem to Lititz in 1756 with her first husband, Christian Frederick Steinman (d. 1760). Her son John Frederick Steinman (1752–1823) likely apprenticed with Heyne; he was one of the administrators of Heyne’s estate and afterwards took over management of the metalworking business, which he developed into a successful hardware store. At the time of his death in 1781, Heyne owned dozens of pewter spoons, plates, basins, and other wares (including three “Church cups” or chalices), as well as household furnishings such as a spinet, window curtains, a twenty-four hour clock, a desk and bookcase, and several looking glasses. Heyne’s pewter shows a great deal of ingenuity and skillful craftsmanship; he made ecclesiastical vessels for Lutheran, Reformed, and Brethren congregations, for the Moravian churches in Lititz and Bethlehem, as well as a set of altar sticks for a Catholic church. The baroque style of the pewter inlay on the tall clock was an aesthetic in which Heyne was well-versed, as evidenced by the baroque form altar sticks he made for the Most Blessed Sacrament Catholic Church in Bally, Berks County (fig. 58).[21]

The original owner of this impressive clock was probably Frederick Stone (1734–1792) of Lancaster. He was born on November 4, 1734, to Ludwig and Maria Catharina Stein/Stone and baptized at Trinity Lutheran Church in Lancaster. In the year the clock was made, 1762, Frederick married Anna Maria Hambrecht/Hambright on April 12 at St. James Anglican Church in Lancaster. The clock may have been a wedding present, as Ludwig Stein went to great lengths to help his son Frederick get established. In Ludwig’s will of June 4, 1782, he left to Frederick only two English guineas because Frederick had previously received “a handsome Estate consisting of a House & other valuable Effects.” Frederick and Anna Maria had at least five children: Frederick Jr.; Ludwig, born in 1770 and baptized at Trinity Lutheran; Catharine; Susanna; and Anna Maria, who died in 1775 at age seven. From at least 1766 to 1773 Frederick rented a pew at Trinity Lutheran. His father Ludwig Stein was a wealthy innkeeper, land speculator, and staunch Lutheran. Ludwig also made business trips to Germany and on one occasion brought back a silver chalice and bowl, which he presented to Trinity Lutheran. When the Lutheran minister, Laurentius Nyberg, became a Moravian sympathizer, Ludwig led the opposition against Nyberg’s efforts to unite the congregation with the Moravians. During a heated confrontation and attempted lock-out in 1745, he shoved the pastor into the sacristy and broke down the church door. Nyberg and his supporters withdrew from the Lutheran church and established their own Moravian congregation in 1746. Despite this turmoil, Ludwig was one of the town’s leading citizens and from 1750–1751 served as the burgess of Lancaster. In 1758, Ludwig was made captain of an all-German militia company. He was also an active member of Lancaster’s Union Fire Company together with some of the town’s wealthiest residents, including Jewish merchant Joseph Simon. The detailed inventory taken after Ludwig’s death in 1782 lists an impressive assortment of fine clothing, several sets of bed curtains, two pairs of brass-topped andirons, fourteen glazed pictures, a clothes press, a walnut desk, a gilded German bible and silver-mounted psalm book, and extensive china, delft, and Queensware.[22]

Frederick Stone followed in his father’s footsteps and became a tavernkeeper and leading citizen of Lancaster. He helped to found both the Lancaster Library Company (est. 1759) and Friendship Fire Company (est. 1763). Frederick served as Lancaster County coroner from 1761 to 1762 and, in December 1763, was one of fourteen jurors selected by then-coroner Matthias Slough for an inquest regarding the brutal murder of six Indians on December 14, 1763, by the so-called Paxton Boys, a tragedy known as the Conestoga Massacre. From 1767 to 1773 Frederick served as sheriff of Lancaster County; he was succeeded in this position by John Ferree. Although he was of Lutheran heritage, Frederick Stone was one of several leading Germans in Lancaster who at least nominally joined St. James Anglican (later Episcopal) Church. Other prominent English-speaking members of St. James included George Ross, an attorney and iron forge owner, and Edward Shippen, former mayor of Philadelphia. Frederick Stone was buried at Trinity Lutheran, however, following his death on December 19, 1792.[23]

How did Frederick Stein, whose father had so zealously opposed the Lancaster Moravians, come to own a clock with a movement made by a Moravian clockmaker and a case with pewter inlay possibly supplied by a Moravian pewtersmith? Put simply, much had changed in Lancaster in the twenty years since the 1745 controversy. Under the leadership of Lutheran patriarch Henry Melchior Muhlenberg, head of the Pennsylvania Ministerium, the Lutheran church was thriving while the Moravians’ influence was on the decline following the death of leader Nicholas Ludwig von Zinzendorf in 1760. As Lancaster grew, civic organizations also arose that provided opportunities for people of different faiths to interact. A prime example of this was the Juliana Library Company (est. in 1759 as the Lancaster Library Company). Its 1763 charter includes the names of both Frederick Stone and Rudy Stoner as founding members. Matthias Slough is also listed, as is the Moravian gunsmith William Henry (see fig. 9), into whose house the library’s books were moved in 1766. As proof of how far Lutheran-Moravian relations had improved by 1782, William Henry even served as a witness to Ludwig Stein’s will.

Closely related strapwork inlay appears on a tall clock with an eight-day movement signed by Christian Forrer (1737–1783) of Lampeter, Lancaster County (figs. 59, 60). Although the case is undated, it is stylistically early and was probably made between 1754—when Christian Forrer and his brother Daniel, also a clockmaker, emigrated from Switzerland—and 1774, when Christian moved to York County. The inlaid panels on the sides of the hood mimic the approximate size and location of sidelights; the inlay on the pendulum door is a smaller version of that on the sides of the case. Whereas the Stoner clock used pewter to outline the strapwork inlay, this clock uses lightwood stringing. The clock descended in the Eaby family of Leacock Township, Lancaster County; the pendulum is engraved “Jacob Eaby 1799 / Jason K. Eaby 1907.” The first name probably refers to Jacob Eaby (1776–1842), who married Susanna Miller in 1799. He was the youngest son of Jacob Eby (1728–1794) and Hannah Laeder (1733–1810), who were probably the first owners of the clock. Jason K. Eaby was born in 1845 to Moses Eaby (son of Jacob Eaby) and Susanna Kurtz.[24]