Cover of Luke Vincent Lockwood’s Colonial Furniture in America (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1901; photo, Gavin Ashworth). The first edition of this milestone publication featured cover art derived from the “Hartford chests” Lockwood so admired. A “Hadley chest” illustrates the title page, and the frontis features a highly stylized “Portsmouth” blockfront. Although the text is far from exclusive in its emphasis on regional styles, there has never been an American furniture survey that balanced the regional and the cosmopolitan more equally.

Portrait of Homer Eaton Keyes, ca. 1925. (Courtesy, Antiques.)

Frontis of Albert Sack’s Fine Points of Furniture: Early American (New York: Crown Publishers, 1950). (Courtesy of Sack Heritage Group; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) www.sackheritagegroup.com

Governor’s Palace dining room as furnished ca. 1950. (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Governor’s Palace dining room as furnished ca. 1980. (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Furniture exhibit in the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Gallery, ca. 1988. (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Connecticut Furniture, Wadsworth Atheneum, 1967. In addition to its role as a catalyst for the study of regional furniture, this exhibition was also the first to display furniture on high pedestals as “art.” John Kirk designed the installation.

Portrait of Alice Winchester, ca. 1970. (Courtesy, Antiques.)

Arts of the Pennsylvania Germans, Special Exhibition, Philadelphia Museum of Art and Winterthur Museum, 1983. (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art.)

American Rococo, 1750-1775: Elegance in Ornament, held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Jan. 26-May 17,1992. (Courtesy, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, all rights reserved.)

The Great River, Wadsworth Atheneum, 1985. (Courtesy, Wadsworth Atheneum.)

China table attributed to Robert Harrold (fl. 1765-1792), Portsmouth, 1765–1775. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with maple and white pine. H. 28 5/8", W. 36 1/4", D. 22 7/16". (Courtesy, Carnegie Museum of Art; museum purchase, Richard King Mellon Foundation grant, acc. 72.55.2.)

East Windsor and Philadelphia compared: Left: Side chair, attributed to Eliphalet Chapin, East Windsor, Connecticut, ca. 1780. Cherry with pine. H. 38", W. 22 3/4", D. 18". Right: Side chair, Philadelphia, ca. 1755. Mahogany with pine. H. 40 1/4", W. 23 1/2", D. 18 1/2". (Courtesy, Wadsworth Atheneum; Hartford. Gift of Mrs. Gordon W. Russell [left]. Gift of Samuel P. Avery [right].) Eliphalet Chapin made “Philadelphia chairs” for a Connecticut market. They were related in proportions, construction, and form, but different in materials and decorative details.

Chest with drawers, probably Hadley, Massachusetts, 1695–1700. Maple with pine. H. 45 1/8", W. 43 1/2", D. 19 3/4". (Courtesy, Wadsworth Atheneum; Evelyn Bonar Storrs Trust Fund and gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, by exchange, acc. 1991.18.) This chest is presumed to be the earliest of several variants of the “Hadley chest” produced in the mid-Connecticut Valley between about 1685 and 1730. This example is the most similar to carved chests from the Wethersfield, Hartford, and Windsor vicinity and is believed to have been adapted by joiners from that area.

Desk-and-bookcase, Hampshire County, Massachusetts, ca. 1775. Cherry with pine. H. 82 3/4", W. 35 1/2", D. 19 3/4". (From the Collections of Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village, Copy and Reuse Restrictions Apply.)

Door, circa 1750, from the Daniel Fowler house, Westfield, Massachusetts,. (Courtesy, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1916. (16.147) Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Gravestone of Samuel Pease, possibly made by Ezra Stiles, Enfield, Connecticut, 1770. (Photo, William Hosley.)

Cupboard in the Dr. Alexander King House, attributed to Eliphalet King, Suffield, Connecticut, ca. 1764. (Courtesy, Suffield Historical Society.)

Gravestone of John Thrall, carved by Phineas Newton, East Granby, Connecticut, 1791. (Photo, William Hosley.)

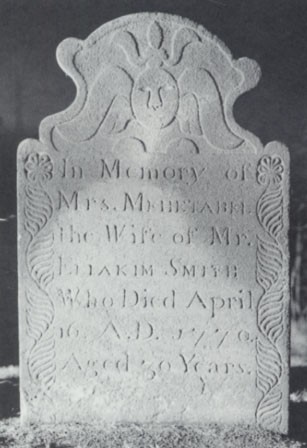

Gravestone of Mehetabel Smith, Hadley, Massachusetts, 1770. (Photo, William Hosley.)

Detail of the pilaster of a high chest of drawers attributed to Eliakim Smith, Hadley, Massachusetts, ca. 1770. Cherry with white pine. H. 89 3/4", W. 39 15/16", D. 20 3/8". (Courtesy, Historic Deerfield, Inc. photo, Amanda Merullo.) www.historic-deerfield.org

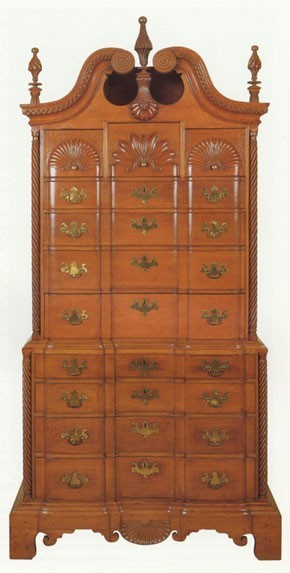

Chest-on-chest, southern New Hampshire, ca. 1780. Maple with pine. H. 89", W. 40 5/8", D. 19 7/8". (Courtesy, The Currier Gallery of Art, Manchester, New Hampshire. Museum purchase: George A. Leighton Fund, 1960.7; photo, Frank Kelly).

Chest-on-chest on frame by Samuel Loomis, Colchester, Connecticut, ca. 1775. Mahogany with pine. H. 88", W. 45", D. 26". (Courtesy, Wadsworth Atheneum; gift of Mr. and Mrs. Arthur L. Shipman, acc.1967.140.)

Cupboard and case of drawers, Mount Lebanon, New York, ca. 1820. Painted pine with fruitwood knobs. H. 96", W. 54", D. 14". (Courtesy, Mount Lebanon Shaker Collection. Circulated by Art Services International, Alexandria, Virginia.)

Gibson House, Canandaigua, New York, ca. 1820. (Courtesy, Ontario County Historical Society.)

George West house, Irasburg, Vermont, 1824–1834. (Courtesy, Middlebury College and Erik Borg.) This is one of a group of houses built in the upper Connecticut Valley from the mid-1820s until about 1850. The earliest examples appear to have originated in the northern part of the state and may have roots in French Canadian building practices.

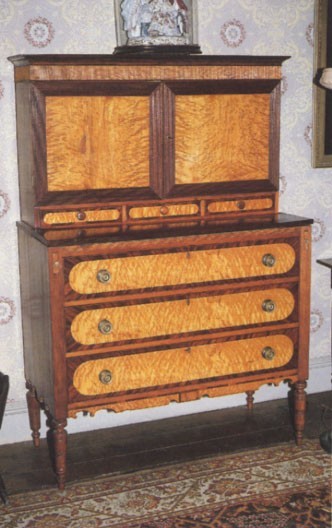

Desk-and-bookcase, Middlebury, Vermont, ca. 1820, Maple and cherry with pine. (Courtesy of the Henry Sheldon Museum of Vermont History, Middlebury, Vermont.) Although the contrasting veneers of this desk-and-bookcase are stylistically related to cabinetwork from Portsmouth, New Hampshire, it is part of a group of western Vermont furniture distinguished by brilliantly figured curley and bird’s-eye maple panels and veneers.

Desk-and-bookcase by John Shearer, Martinsburg, West Virginia, 1801 (desk) and 1806 (bookcase). Walnut, cherry, and mulberry with yellow pine and oak. H. 106", W. 45", D. 24 1/2". (Collection of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Winston-Salem, North Carolina.)

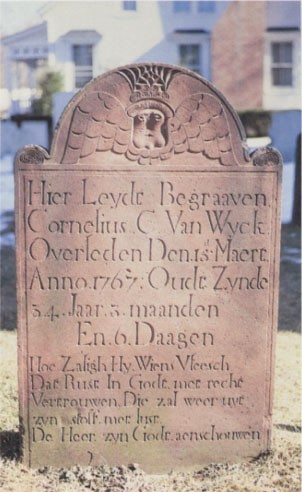

Gravestone of Cornelius C. Van Wyck, Fishkill, New York, 1767. (Photo, William Hosley.)

Gravestone of Catherina Elserin, Adamstown, Pennsylvania, 1793. (Photo, William Hosley.)

German Palatine Church, Stone Arabia, New York, 1770 with tower about 1805. (Photo, William Hosley.)

Gravestone of Cuffe Gibbs by Pompe Stevens, Common Burying Ground, Newport, Rhode Island, 1768. (Photo, William Hosley.) The several dozen stones marking the graves of African slaves in Newport’s largest colonial burying ground is the largest concentration in New England. This stone is signed by an African American stonecutter, Pompe Stevens, who probably worked in the shop of John Stevens, Newport’s most skilled and prolific stonecutter.

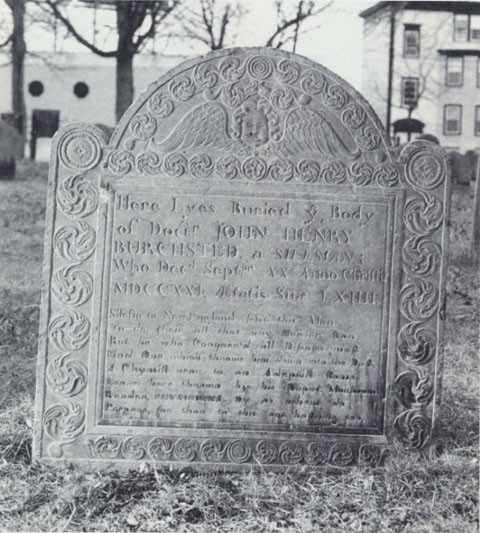

Gravestone of Dr. John Henry Burchsted, Lynn, Massachusetts, 1721. (Photo, William Hosley.) This prominent physician was from Silesia, and his gravestone is one of the most expensive from its time.

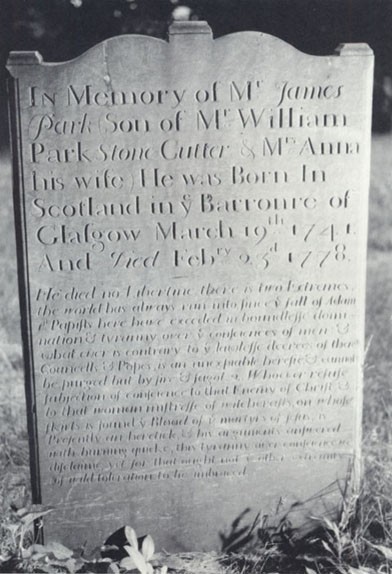

Gravestone of James Park, Groton, Massachusetts, 1778. (Photo, William Hosley.) The Park family of Groton were a multigenerational dynasty of Scotch stonemasons.

In preparing for the tour of Brock Jobe’s exhibition, Portsmouth Furniture, organized by the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities and the Currier Gallery of Art, the Wadsworth Atheneum faced the problem of finding a way to position a regional subject outside the subject region. The curators, educators, media, and marketing people who ponder such things asked the obvious question, “Why should Connecticut care about New Hampshire furniture?” Said another way, Why should one part of the country care about a different part of the country, especially where there is no obvious connection between them? Most of the time, the basic answer—it’s art, it’s beautiful, it’s important—works. But playing the regional card always seems to throw the pundits off balance and usually results in a subject being diminished and reclassified as of “local significance.” Clearly, however, Portsmouth Furniture contained not only splendid “works of art” but a message that is universal in its appeal, transcending the peculiarities of place. Is that a surprise?

We struggled with the problem and in the end decided to enmesh Portsmouth Furniture in a program that included a Connecticut component and a Massachusetts component—a three-ring circus of regional furniture with Portsmouth in the center ring. The now-clichéd quest for a “sense of place” was the overarching theme. “A Sense of Place: Furniture from New England Towns,” and the conference that gave rise to this collection of articles, was our way of addressing the problem of moving a regional subject outside its subject region. The solution worked (good attendance, lots of publicity, and a sold-out conference), but it should not have been necessary. Why is contemporary life so poorly connected with the extraordinary language of regional life? How has a quality once so totally enveloping and pervasive (the violation of states rights and regional self-determination was one of the causes of the Civil War) become so mysterious and inaccessible? Is this loss of regionalism a result of the global village?

History shows that regional identity has not always been so hard to embrace. The national media, “global” corporations, and command-and-control government bureaucracies, however, have spent the past half century evangelizing national culture and globalism. The regional dimension of culture has been stigmatized. To be “provincial” or “parochial” is to be dismissed. History, as it is taught where it matters most—at the elementary and secondary level—is about “the national experience.” Granted, it is difficult to customize texts and curricula to reflect state and local conditions.[1] Although regional and (more often) ethnic diversions provide anecdotal seasoning, the “main storyline” rarely accounts for the extraordinary texture and diversity of cultures and culture regions that is and has long been a powerful but elusive feature of the United States, a nation much of the rest of the world regards as hopelessly and frighteningly expansive.

It is perhaps sensible to tread lightly in citing literature with an imprint date of 1972, but, in a short essay titled “The Regional Motive,” Wendell Berry—the poet laureate of American regional life—had much of current relevance to say on this subject. Berry, whose writings emanate from a sense of his Kentucky surroundings, describes the word “regional” as often “either an embarrassment or an obstruction,” “sloppily defined in its usage,” and “casually understood.” Dismissing “‘regionalism’ based upon pride” as well as that which “tends to generalize and stereotype” by imposing “false literary or cultural generalizations upon false geographical generalizations,” Berry, instead, defines regionalism as “local life aware of itself.” One might, to good effect, engrave the frieze of a public building with Berry’s words: “By memory and association men are made fit to inhabit the land.” He concludes, “Without a complex knowledge of one’s place, and without the faithfulness to one’s place on which such knowledge depends, it is inevitable that the place will be used carelessly, and eventually destroyed.” According to Berry, only through such “knowledge and faithfulness” does a culture (or antique furniture, for that matter) avoid being reduced to the merely “superficial and decorative.” The regional dimension thus matters much, and it is almost certainly the quality that gives antique furniture such enduring power, not only in museums and collections but especially in those places of “memory and association.”[2]

Because art museums often serve as proxy for museums in general, and because they are so dominant in the museum economy, it is interesting to ponder the ways in which “the regional motive” plays out in these institutions renowned for their commitment to globalism and cosmopolitanism. My director, an Anglo-Australian, has marveled from time to time at the almost fetish-like way American museums collect and display furniture, to a degree apparently unmatched elsewhere in the world. I suspect he would regard Winterthur and Historic Deerfield as uniquely American sorts of institutions, and I would argue that it is the “regional motive” that makes them special. Also, until about 1975, the “field” of paintings was so dominated by Eurocentrists that the decorative arts was about the only avenue for American art in American art museums. American painting, then mostly looked after by curators of antiques who preferred “pots and pans” and curators of paintings who preferred Europe, never quite got out of the bag. Today, American paintings are very much out in front, having marched rapidly from obscurity to prominence, leaving to furniture and “antiques” an ever-more iconoclastic role.

Is American furniture art, or is it history? The fact that historians in the field are notoriously and almost uniquely equivocal on this point is proof of the intractability of an ideology rooted in regionalism and antiquarianism, areas of study strikingly incompatible with “modernism” and traditional art history. I prefer to characterize modernism as “the ‘art-for-art’s sake,’ one-world point of view” that willfully drains art of the context that gives it meaning. Antiquarianism, on the other hand, is an extension of love for one’s surroundings, or even love of the earth. It is potent stuff, and it is ancient in its practice. The Japanese have a long tradition of antiquarianism that elevates reverence for objects (partly a spiritual quest for knowledge, not unlike what the West calls connoisseurship) to an art. Antiquarianism is inevitably centered in the study of place, and it is no accident that the greatest antiquarians have also been regionalists or, at least, persons who practiced the kind of “complex knowledge” and “faithfulness to one’s place” that Wendell Berry describes so artfully. Antiquarianism thus survives—albeit barely—in art museums in the guise of furniture studies, period rooms, and exhibitions like Portsmouth Furniture, and in other manifestations of “civic mission.”[3]

American furniture studies is not monolithic and, over the years, has been unmistakably committed to exploring aspects of aesthetic pluralism and regional diversity. As early as a century ago, pioneers like Irving Lyon and Luke Vincent Lockwood hinted that the regional character of early American craftsmanship was the primary source of its appeal (fig. 1). Many of the pioneer collectors who built the great public collections were antiquarians and regionalists who sought the convergence of art, history, and place.[4]

The eclipse of the antiquarian tradition in American furniture studies began in the 1920s with the quest to annoint cabinetmaking’s canonized saints. The first issue of the magazine Antiques embraced both modernist and anti-modernist sentiments. In spite of feature articles such as “A Cabinet-Maker’s Cabinet-Maker, Notes on Thomas Sheraton,” founding editor Homer Eaton Keyes (fig. 2) was able to write a mission statement for the magazine that skewered modernism as “purposely disdainful of tradition, sublimely certain of its own ability to invent, devise, design in and for the future, . . . without recourse to an obviously . . . incompetent past.” Playing on Daniel Webster’s famous claim about Dartmouth College, Keyes acknowledged that “the past is, indeed, sorely disprised; yet there are those who love it.” Furthermore, in a passage worthy of Edmund Burke, Keyes outlined the essential conservatism of the antiquarian tradition, claiming that among the “defenders of the past are some who realize . . . things have been done as well as human inventiveness . . . can do them; far better . . . than they are likely ever to be done again.” The “industrial arts and crafts,” Keyes concluded, are the perfect antidote to “novelty for novelty’s sake,” providing a “humane acquaintance” with the past.[5]

Regionalism and antiquarianism were never eclipsed entirely, and throughout the Depression, studies of Hadley chests, Connecticut furniture, and Sandwich glass, among other things, show the persistence of regional scholarship in the field of American “industrial arts and crafts.” The middle half of the twentieth century marked the triumph of aesthetics over antiquarianism, epitomized in Albert Sack’s Fine Points of Furniture (1950), which coined the term and gave rise to the “good, better, best” school of furniture appreciation (fig. 3). Although antiques evangelists like Wallace Nutting (Furniture of the Pilgrim Century [1924] and Furniture Treasury [1928]) were basically aiming for the same target, Nutting was either unwilling or unable to advance a fully developed hierarchy of quality amidst the messy jumble of facts, images, and anecdotes that characterize his work. Nutting remained to the end as much minister as man of commerce. He was never very facile at manipulating the commercial side of his passion for antiques, and he never fully embraced the property of art that now makes it such a powerful vehicle for articulating prestige. Nutting was a transitional figure between the antiquarians and regionalists and their modern (and modernist) counterparts in the auction houses and museums.[6]

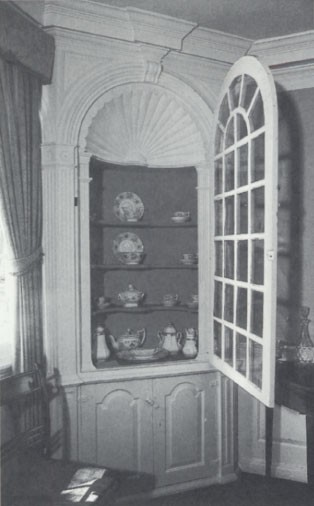

The ideological battle between historicism and modernism, regionalism and aesthetics, recently played itself out in a very public and tangible way at the flagship museum of Americana, Colonial Williamsburg. Curators there spent much of the 1970s and 1980s “restoring” regional context and socioeconomic authenticity (not to mention regionally appropriate furniture) to houses that had served primarily as architectural settings for “tasteful” assemblages of great collections (figs. 4, 5). It is ironic that Williamsburg’s legendary curator, the late John Graham, wrote the introduction to Fine Points, where he rightly claimed for Colonial Williamsburg an important influence “toward improving the general taste of the country.” Apparently there are still legions of admirers who regret that Colonial Williamsburg abandoned its use of historic houses as models of good taste and interior design. In the midst of its campaign of reinterpretion, Colonial Williamsburg created the Dewitt Wallace Decorative Arts Gallery (1985) (fig. 6), a museum-within-the-museum that not only provides for thoughtful temporary exhibitions but is especially devoted to the display of furniture and related decorative arts as art.[7] Colonial Williamsburg and its visitors are richer for the diversity of its new and improved programs of interpretation that, in addition to aesthetics and period verisimilitude, also feature craft demonstration and “living history.” With Williamsburg, Virginia has a museum of international significance that has struck a skillful balance of art and history.

After a long exile, regionalism and antiquarianism are back and, for the first time since the 1920s, rival “good, better, best” as an ideology in American furniture studies. Neo-regionalism, if I may call it that, began thirty years ago with John Kirk’s pathbreaking article on “Sources of Some American Regional Furniture.” This piece not only invoked the concept of “regional furniture” but grappled with the central argument that inspired this collection of articles by asking, “How much originality is to be attributed to American furniture makers?”[8] Not surprisingly, the search for answers to this important question has not always interested furniture historians, and I would argue that differing attitudes about dependence versus independence is at the heart of the ideological tension that makes American furniture studies so interesting.

Like Colonial Williamsburg, John Kirk has also straddled both sides of the fence in ways that have given his work tremendous durability and importance. After reopening the door to regionalism in 1965, Kirk organized a landmark exhibition, Connecticut Furniture: Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries (1967) (fig. 7), and eventually provided a cogent analysis of regional diversity and regional culture in American Chairs: Queen Anne and Chippendale. Yet, fifteen and twenty years later in an essay on “dependence and independence” in his American Furniture and the British Tradition to 1830 and in a subsequent article on “American Furniture in an International Context,” Kirk chided regionalism for its excesses, noting that “until recently parochialness and chauvinism made it nearly anti-American to think of our culture and its expressions as extensions of Europe.” Kirk warned against “this myopic view of our art,” noting that the “recent acceptance of the integration of American and European art” was threatened by what he dubbed “the new chauvinism.” The search for regional style, Kirk argued, was a false quest that overlooked the persistent indebtedness of American artisans and their clients—even those in “provincial” settings—to British influence. Without directly repudiating regionalism, Kirk undermined one of its traditional assumptions, the notion of American inventiveness and originality. With hundreds of case studies and comparisons, Kirk showed how even obscure furniture-making traditions were closely related and probably derived from British and European sources. Again, globalism scores.[9]

Does Kirk’s proof that American furniture makers often depended on European ideas disprove the occasional act of inventiveness? That much American furniture was based on European models is hardly as surprising as the fact that some was not. To reduce interpretation to an argument between regionalists and aesthetes trivializes the depth and mutual indebtedness both points of view have to each other and to other areas of study. Nonetheless, American furniture studies remains polarized in its view on originality and innovation. Regionalists and antiquarians generally champion the notion of an indigenous American craft tradition of distinction and originality, while the aesthetes prefer to dwell on the continuity of Anglo-American culture, anxious to avoid looking “provincial” by ignoring stylistic dependence on “the mother culture.” The truth, such as it is, however, is mostly a matter of degree. Originality varies depending on where you look, hence, once again, the importance of place. It is thus the relationship between innovation, diversity, and place that the regional furniture symposium and these papers explore.

Call it what you will—neo-regionalism, “the new chauvanism,” or the new antiquarianism—beginning in 1965, regional furniture began its slow march back to respectability as art and as a point of view. On the heels of Connecticut Furniture, Alice Winchester (fig. 8), the editor of Antiques, dedicated a theme issue to the subject of “country furniture.” She convened a “symposium” during which leading authorities, such as Charles Hummel and Charles Montgomery of Winterthur, the late antiquarian/collector Nina Fletcher Little, Frank Horton of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, and Connecticut antiquarian, William Warren, were asked to “define country furniture.”[10] Its purpose was to honor and recognize the importance of rural work, much neglected after years of emphasis on Boston, Newport, and Philadelphia; on Frothingham, Seymour,Goodard-Townsend, Affleck, and Savery. It also served to revisit the question of American inventiveness that the panelists widely and almost unanimously associated with rural work.

Charles Montgomery characterized country furniture by its “bold statement of city elements,” perpetuation of tradition, use of native woods, and, perhaps most importantly, by the tendency of makers to borrow from whatever sources were handy. He concluded by asserting that the act of making an object that “shrieks its countryness” is “highly creative.” In Connecticut Furniture and “American regional furniture,” John Kirk said essentially the same thing, noting that “small individual style centers developed an originality of interpretation which is characteristic of rural furniture in all countries,” and that, “while they did not create something wholly new, they drew upon their heritage to create something distinctive and to that extent original.”[11]

In March of the following year, the reawakening of interest in rural, regional, and vernacular art continued with Winterthur’s conference, corresponding “rotunda exhibition,” and conference report titled Country Cabinetwork and Simple City Furniture. The conference aimed to “define country furniture” (their term for the tendencies Kirk, myself, and others describe as “regional”), describe the contacts between rural and urban craftsmen, analyze the relationship between central and regional style centers, and ultimately address “those who assail museum collections as not representing the objects owned by a cross section of earlier Americans.” Ironically, it was Winterthur’s concern about this last point that shifted the discussion from an emphasis on the inherently “elitist” notion of innovation to the anti-elitism of “less sophisticated furniture.” Winterthur’s contribution to the study of “country furniture” had the effect of linking the subject with a campaign to, as one conference participant put it, become “involved in the history of the working classes; . . . history from the ‘bottom up.’”[12] The subtext of the conference, which conjoined “country cabinetwork” with “simple city furniture,” submerged country furniture into a grab-bag of underrepresented, nonelitist “goods,” now presumably as worthy of study as “the best.” It is hardly a surprise, given the mood of the 1960s, that museums were anxious to refute charges of “elitism.” By associating “country” with other forms of “non-high-style” furniture, Winterthur helped transform the study of regional furniture into a program aimed at establishing parity for, or at least the viability of studying, all furniture-making regions. Unfortunately, doing so diverted the discussion from more reliable issues, and it certainly left many questions—questions that speak directly to the subject of American cultural identity and the social uses of furniture—unanswered. When examining the Dunlaps, Hadley chests, or even Vermont painted furniture, anti-elitism is hardly the first thing that springs to mind in a first encounter.

Since Winterthur helped pry open the door to the study of furniture regions everywhere, the flurry of scholarship and activity has been almost too much to keep up with. Whether or not audiences are large for monographs such as Furniture of the Georgia Piedmont Before 1830, New London County Joined Chairs, 1720–1790, North Carolina Furniture, 1700–1900 (1977), Raised-Panel Furniture 1730–1830 (of the Eastern Shore, Virginia), or for studies of furniture from the Upper St. John Valley (in Maine), Ohio, or even Long Island, these books and articles, not to mention the proliferation of scholarship out of institutions like the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, prove the vitality of regional scholarship, a pursuit once nearly given up for dead. Add to this plethora the related scholarship on ethno-regional art and history, notably, The Arts of the Pennsylvania Germans (fig. 9) and Remembrance of Patria: Dutch Arts and Culture in Colonial America, and the impression of a stampede is complete.[13] Knowledge about rural craft, the relationship between “rural” and “urban” places, relations among ethnic subcultures, and the issue of inventiveness in furniture design has finally reached the point where it was worth revisiting the subject with the goal of drawing some new conclusions and, perhaps, resolving some of the questions first raised by Kirk and the symposium participants at Antiques, almost thirty years ago.

Where does the renaissance in regional scholarship leave the aesthetic tradition? Alive and well. Is it not a healthy sign that “furniture studies” admits mulitiple points of view? Indeed, some of the best work in American furniture studies is unabashedly aesthetic in perspective, striving, as always, to document, define, and qualify aesthetic excellence. That it is not always reliable in its historical interpretation is no surprise. Authors of the recent exhibition catalogue American Rococo, 1750–1775: Elegance in Ornament stated their purpose in selecting “the best examples of domestic creativity,” which they defined as objects of “exceptional workmanship and aesthetic merit.”[14] Actually, as masterful as the work may be, American furniture of “exceptional workmanship and aesthetic merit” may well be the least expressive of “domestic creativity.”

Pejorative notions of provincialism oversimplify and undermine one of the most interesting processes in American art, the formation of high-style work that actively resists conforming to cosmopolitan design standards. In condemning the “new chauvinism,” John Kirk talked about the “recent acceptance” of internationalism as if there was resistance. Since the late 1970s, however, no topic in furniture studies has been nearly so prominent as the debunking of American originality, the effort to prove that virtually none of our American furniture—especially the symbolically charged “furniture of the pilgrim century”—failed to exhibit British influence.[15]

In hindsight, the clamoring for British acceptance, implicit in the late Charles Montgomery’s American Art: 1750–1800, Towards Independence (1976), an exhibition that celebrated our bicentennial by attacking the notion of American independence, strikes me as ironic. Similarly, John Kirk’s American Furniture and the British Tradition provided a breathtaking panorama of American dependence by illustrating hundreds of styles, forms, and regional craft traditions that link America to British design. Mutual respect and understanding between the ideological poles has not always been generously forthcoming. Most recently, in The American Craftsman and the European Tradition (1988), Michael Conforti announced that “in time, the sentimental patriotism on which the study of American decorative arts was founded will be completely erased from the institutional and museological programs it fostered.” The introduction to this recent exhibition and catalogue dismissed the quest for a romantic vision of the heroic past as “patriotic antiquarianism” while positing an internationalist view emphasizing webs of influence and dependence. Certainly, such intolerance is unintended and based on an incomplete reading of the antiquarian tradition, which, as I have suggested, was always more than the sum of its caricature, a caricature peopled with provincial regionalists, “sentimental patriots,” bigots, and Anglophiles.[16]

American Rococo, the last major furniture exhibition before Portsmouth Furniture, appealing as it was, is a topic that could not fail to underscore the notion of American dependence on British and European tradition. Who can recall a more impressive assemblage of impeccibly crafted and intricately designed American furniture (fig. 10)? It must have been especially comforting to those fond of the idea of Americans communing with European art and culture. No style in the history of American furniture was ever more elitist in its practice and origin. In the hierarchy of “good, better, best,” American rococo is generally perceived as the best of the best. When authors talk about engraved designs, print sources, pattern books, imported objects, and immigrant artisans as vehicles for the transmission of the rococo style, they are looking at a context that was almost exclusively urban and not especially representative or “inclusive.” So what? American rococo-style furniture is some of the best American art, even if it is often American with a small “a.” But it is a different kind of art than I see from my perch in Connecticut country. Some years ago, when we were preparing The Great River: Art and Society of the Connecticut Valley, 1635–1820 (1985) (fig. 11), I was amused to discover no evidence of furniture or architectural pattern book ownership anywhere in the Connecticut Valley before the Revolution. Probably, few practiced cabinetmaking as a specialty then, let alone carving, upholstery, or chairmaking. It was a different world. Regional versus cosmopolitan habits were thus mostly a matter of degree and vary depending on where you look.

The aesthetic and regional approaches are both useful, and each contributes significantly to making American furniture studies vital and interesting. In addition to its luscious sensuality, efforts like American Rococo dispel provincial anxiety by emphasizing international networks of style and the formation of artisan skill. Antiquarians and regionalists mostly agree that aesthetic quality matters. Noting Israel Sack’s criticism (preface to Fine Points of Furniture) of people who value antiques “merely because of their age,” regionalists do not value furniture only because of its place of origin. Skillfulness at craft and inventive design vary between places and within them. The fact that something was made in Portsmouth, for example, does not mean that Portsmouth antiquarians will necessarily prize it. Antiquarians and aesthetes alike can share admiration for an aesthetic triumph like the great Portsmouth-made rococo china table (fig. 12) while acknowledging that its design was conceived three thousand miles away in Britain. In The Great River, we were just as interested in documenting Boston, New York, and Philadelphia objects and influences (fig. 13; see Philip Zea’s article in this volume, fig. 32) as in showing the peculiarities of our subject region. Of course, devotees to Philadelphia and Boston would be correct in identifying a regional dimension in that furniture as well. English pattern books were not used much anywhere, so again, the rivaling perspectives quibble mostly over matters of degree.

It is not surprising to find the “Hadley chest” (fig. 14) in the crossfire on this issue of dependence and independence and as a symbol of an indigenous American art. In addition to Portsmouth Furniture, our program—“A Sense of Place: Furniture from New England Towns”—included a special gallery tour of the Wadsworth Atheneum’s “Furniture Treasures from Connecticut Towns,” and a splendid exhibition, Hadley Chests, organized by Suzanne Flynt and the staff at Memorial Hall in Deerfield. Admired by collectors for more than a century, the Hadley chest seems inherently intriguing, and its power acts in strange ways. Efforts to deny this iconic example of American originality have, I think, failed.[17] Instead, their study has led to demands that we reopen the question Kirk and the participants in Antiques’ “country furniture” symposium sought to answer in the first place: “How much originality is to be attributed to American furniture makers?” What defines originality? Where should we look for it? Is the legend of Yankee ingenuity a reality or a myth? Might regional diversity be the root of innovation?

To address these and other pertinent questions, a group of prominent academics and museum curators gathered in Hartford, Connecticut, on March 26, 1993, for a one-day program entitled “Diversity and Innovation in American Regional Furniture.” This meeting was the intellectual centerpiece of a program called “A Sense of Place.” Beginning in the spring of 1992, assistant curator Karen Blanchfield, museum educator Cynthia Cormier, and I planned the program, solicited papers, lined up sponsorship from the Connecticut Humanities Council, and collaborated with “Connecticut Antiques Show” manager, Linda Turner, and Trinity College’s American Studies department chair, James Miller, in concept development and promotion. Best of all, the Chipstone Foundation kindly agreed to adopt the theme of the conference for this special issue of American Furniture, thus enabling us to attract and publish new work by leading experts: Donna K. Baron, curator at Old Sturbridge Village, Edward S. Cooke, professor of art history at Yale University, Neil D. Kamil, professor of history at the University of Texas at Austin, Kevin M. Sweeney, professor of history and American studies at Amherst College, and Philip Zea, curator at Historic Deerfield. We were especially fortunate in Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s willingness to provide a keynote address. Now a professor of history at Harvard University, Ulrich at the time was riding a wave of acclaim for her widely tauted, A Midwife’s Tale: The Life of Martha Ballard, Based on Her Diary, 1785–1812, a social biography that captures the essence of daily life, place, and personality with alluring power.

Citing precedent from John Kirk’s writings and from the Antiques and Winterthur programs twenty-five years earlier, conference participants were asked to consider “how regional cultures interface with each other and with ‘parent’ cultures”; if a “buy local” policy may have affected consumer choice; the relationship between art, ethnicity, and place; the “impact of industrialization and mass communications on regional art during the 1810s–1830s”; the relationship between furniture studies and other “non-traditional modes of scholarship”; and, most importantly, the role of cultural diversity in fostering innovation.

In “Furniture as Social History: Gender, Property, and Memory in the Decorative Arts,” Laurel Ulrich sets the tone with a call for furniture historians to reconnect objects with social context and by asking the surprising question: “If tables and chairs have arms, legs, and toes, do they also have sex?” Ulrich’s essay reminds us that beyond fashion and place are men and women with personal needs, making personal choices. Her study of the social economy of women’s work has greatly enhanced awareness of the intractable and unquantifiable factors that shape the lives of individuals and communities. Nowhere is the effectiveness of her approach more apparent than in her pathbreaking analysis of Hannah Barnard’s cupboard, one of the most richly symbolic and totemic pieces of early Connecticut Valley furniture. By shifting the emphasis from furniture makers to furniture owners, Ulrich helps us personalize and humanize matters of style and innovation. By providing a perspective on women’s roles in the consumer culture of colonial America, Ulrich has broadened the notion of diversity and made it easier to grasp how peculiarities of gender may have affected the use and appearance of furniture.

With “Hidden in Plain Sight: Disappearance and Material Life in New York Colony,” Neil Kamil has produced a crisply articulated analysis of ethnic subcultures that shared space and shaped civic culture together. Skillfully deploying furniture and artifacts as powerful and convincing documentary evidence, Kamil takes aim at the Knickerbocker myth and reveals how the “real story of New York’s material culture was . . . ethnic and cultural diversity.” Almost as an aside he makes the most convincing case yet for the role of “Boston chairs” as a “medium of intercolonial communication” and as icons of cosmopolitanism. Kamil’s mysterious Huguenot artisans emerge as deft cultural arbitrators greasing the wheels by which diverse European joinery traditions and cultures converge in a new world environment.

In “Regions and the Study of Material Culture: Explorations Along the Connecticut River,” Kevin Sweeney, eminent Connecticut Valley historian and the primary collaborator on The Great River exhibition, offers valuable historiographical insights into the uses and abuse of “regionalism” and a thoughtful selection of case studies exploring aspects of design, innovation, and cultural accommodation through regional furniture. Sweeney distinguishes between regional history and “regionalism,” a concept that too often devolved into a search for the uses and abuse of “regionalism” and a thoughtful selection of case studies exploring aspects of design, innovation, and cultural accommodation through regional furniture. Sweeney distinguishes between regional history and “regionalism,” a concept that too often devolved into a search for the “the essence of America and a yearning for community stability.” In a meticulously reasoned case study on Wethersfield, Connecticut’s famed “sunflower” chests, Sweeney brings closure to a long-standing debate about the source of this renowned and iconic “American” design. Although indebted to several imported joinery traditions, including one from the north of England and another rooted in the Low Countries or the Channel Islands, the unusual configuration of carved flowers, geometric panels, and applied turnings was invented in Wethersfield, the result of diverging subcultures and the quest for consensus among competing artisans.

Philip Zea, Historic Deerfield’s resident regionalist and a noted evangelist for rural material culture, broadened the discussion with a series of multiregional case studies spanning almost two centuries, entitled “Diversity and Regionalism in Rural New England Furniture.” Zea surveys New England’s material landscape, selecting regional objects with a seasoned eye and demonstrating aesthetic complexity with case studies that point out how situational and irreducible the creative process can be. Connecticut inventors Benjamin and Timothy Cheney adapt an inheritance of woodworking knowledge to come up with the first American timekeeping mechanism made of wood, an achievement largely overlooked by aesthetes because the cases that house their clocks do not conform to high-style paradigms. Seasoned by the old rythmns of the agricultural year, improvisation was natural for first-generation “urban” cabinetmakers like William Lloyd of Springfield, who answered the need for new forms by reshaping and adapting components of the old. Zea illustrates the process of hybridizing fashion and treats the diversity of regional furniture as metaphor for the dynamic complexity of regional life.

“The Social Economy of the Preindustrial Joiner in Connecticut, 1750–1800” is Ned Cooke’s contribution to the problem of explaining the extraordinary stylistic diversity of rural work, especially in Connecticut, the least centralized of the thirteen colonies and one with incredibly diverse furniture styles. Zeroing in on the critical last half of the eighteenth century, Cooke provides a new reading of the “social contract” within the apprenticeship system as a basis for exploring the “social economy of joinery.” The foundation of “Yankee ingenuity” must lie somewhere near Cooke’s image of the rural joiner who, if not a jack-of-all-trades, was often a master of design, workmanship, decoration, and marketing—furniture and buildings—bundled together before the “era of specialization.” Cooke’s declaration that “part time does not mean part skilled” reveals the rural joiner as the quintessential inventive mind at work.

Finally, Donna Baron takes us into the nineteenth century with “Definition and Diaspora of Regional Style: The Worcester County Model.” However one defines regional art, at some point furniture apparently ceases to be a powerful medium of regional culture. Baron’s study of Worcester County’s remarkable and under-reported role as a precedent-setting incubator for industrial technology and marketing illustrates the forces that reduce “our chair” to a universal, mass-produced, mass-marketed product I like to call “McChair.” Worcester County chairmakers intentionally hybridized stylistic sources to create the chair that would test the waters of mass production and mass marketing. Baron’s description of Worcester County chairs as “undistinguished but typical,” unappetizing as it sounds, explains an important process at work. Do we expect more of a homogeneous, one-size-fits-all style?

This collection of essays opens some new doors while answering questions raised both now and thirty years ago. In addition to the material assembled here, I share below a portfolio of illustrations and some interpretations in hopes of stimulating further inquiry into regional furniture and joinery, work that testifies to the power of regional life in early America.

Interlocking Trades and Parallelism of Style

Regional furniture represents a conversation between theory and practice, patron and maker, tradition and fashion. It might be understood as a bottom-up solution to a top-down problem. Sources of influence are not easily pinned down because, in the life of the multi-skilled, multi-occupational country joiner, sources were everywhere and anywhere. One of the most conspicuous features of regional work is what Jules Prown and others have described as the parallelism of style. Objects linked in place, time, and sensibility are illustrated by four Connecticut Valley items in the rural baroque style of the 1765–1780 period, objects that epitomize the quality Wendell Garrett once described as “artisan mannerism.”[18] The Hampshire County desk-and-bookcase illustrated in figure 15, the scroll-topped “Connecticut Valley doorway” from the Daniel Fowler house in Westfield, Massachusetts (fig. 16), the gravestone of Samuel Pease in Enfield, Connecticut (fig. 17), and the corner cupboard from the Alexander King house in Suffield, Connecticut (fig. 18), are each striking examples of what Kevin Sweeney, Scott Swank, and others have described as “rural bourgeois art.” Artisan mannerism describes a craftsman pushing the boundaries of skill through what Phil Zea describes as purposely hybridized mixing and matching of elements, with details not infrequently carried out in multiples. Here, however, the impression is not just of craftsmen drawing on a common language of ornament but of actually looking over each other’s shoulders—perhaps even working together—to create a fusion art of totemic significance to their place in time.

This kind of animated dialogue turns up over and over in the Connecticut Valley and also among the Pennsylvania Germans, where, in addition to furniture, architecture, and gravestones, a lively tradition of ornamental painting and ornamental cast and wrought iron reveals an astonishing level of aesthetic integration between craft media. Instances of parallelism abound in the Connecticut Valley: a gravestone (fig. 19) ornamented with the signature feature of the valley’s much-admired “scalloped-top tables,” other gravestones in which the “Connecticut Valley doorway” is mimicked, and, the most suggestive of all, the gravestone for Mehetabel Smith (1770) (fig. 20), whose husband Eliakim is credited with introducing a stylized variant of Boston block-front furniture to the mid-Connecticut Valley.[19] The latter’s signature-flowered pilasters (fig. 21; see also Zea, fig. 35) are the same as the border design on his first wife’s gravestone, one he undoubtedly bought and that might have been the inspiration behind his use of the motif in furniture, or the other way around. In the social economy of face-to-face relationships and custom work, anything is possible.

Adapt and Improvise

The late Charles Montgomery characterized “country furniture” by its “bold statement of city elements,” perpetuation of tradition, and use of native woods. Of rural joiners, Montgomery noted: “As Jacks-of-all trades, he may have been master of none but he was not timid.”[20] Indeed, the rural joiner was a master of appropriation whose mantra was “adapt and improvise,” “adapt and improvise.” At its best, regional furniture is like jazz. Philip Zea shows how this process unfolded in the creation of japanned furniture in East Windsor Hill, Connecticut (see Zea, fig. 23). Other examples abound. A chest-on-chest from southern New Hampshire (fig. 22) shows how an unidentified regional joiner, probably in answer to a patron’s demand for a Boston-type, block-front chest, translated that city’s style into a regional idiom. Instead of mahogany, he used stained maple; instead of a classical, evenly lobed fan, he carved a highly idiomatic, peacock-like motif with outward sweeping lobes; and where Boston work is structurally refined—the work of a new brand of specialist called “cabinetmakers”—this chest is a joiner’s work, the product of a hand (and tool chest) as accustomed to running cornice moldings on houses and laying floors as making finely dovetailed drawers. Massive, bulky, and sculptural, it owes as much to the logic of house joinery as to that of fine cabinetwork. The drawer sides are made of thick, local pine stock, finished with a fat beaded molding on the upper edge. The drawer bottoms are also much thicker than in comparable Boston work, finished with deep chamfering where the edges fit into the drawer sides. Most emblematic of all, the drawer bottoms are fastened at the rear, not with nails as invariably found in city work, but with trunnels (wooden pegs).

Another remarkable example of regional adaptation is the work of Samuel Loomis (1748–1814) of Colchester, Connecticut. Loomis is one of the key figures in the “Colchester School.” The chest illustrated in figure 23, possibly the heaviest and bulkiest American example of this form, is architectural and yet represents a skillful adaptation of the widely exported and eminently cosmopolitan work of Newport’s Goddards and Townsends.[21] The incised vine tracery of its upper drawers suggests a kind of traditional medievalism filtered through the sensibility of the rural bourgeoisie, and where the Newport chests achieve a kind of fussy, repetitive perfection in their finials, Loomis and his New London County peers transform the finial into a virtuoso piece, subject of relentless variety and experimentation.

The Social Economy of Joinery

The “social economy” that Ulrich and Cooke describe so well functions in furniture making by way of customwork and the commitment to “buy local” among community elites. Remember the custom tailors and shoemakers of old? Until the nineteenth century, most regional furniture was produced the same way. An interpersonal dimension thus becomes inherent in the actual product, with occasionally extraordinary results. Laurel Ulrich explores this aspect in the remarkable Hannah Barnard cupboard (see Ulrich, fig. 16) that, in addition to its identity as a product of gender-based familial relations, is also a remarkably inventive demonstration of the expansibility of the Hadley chest.

One of the most memorable examples of the social economy of joinery is the image of Jonathan Smith of Conway, Massachusetts working through a mound of indebtedness to Simon DeWolf and Lydia Batchelder by making one of the most obvious examples of “artisan mannerism” ever produced in the Connecticut Valley (fig. 24). Naturally, two pediments would have to be twice as good as one, especially if they are the only way you are ever likely to see the money this poor but inventive joiner owed you. In addition to providing a means to work off debts, the community elite who commissioned the joiner’s most expensive work were anxious to promote harmony by keeping the home team at work and on the field of play.[22]

Shaker furniture provides another notable instance of a social economy in operation. Although widely recognized for their role in adopting machine technology and for mass producing certain standardized furniture forms, the Shakers also produced a bewildering array of work customized for a domestic economy of obsessive orderliness.[23] Is there another class of American furniture that exhibits more variety than the ubiquitous Shaker cupboards (fig. 25) with their seemingly infinite door and drawer arrangements and built-in and free-standing forms? Symmetry yes, but repetition, almost never. “A place for everything and everything in its place,” but also every place customized to the requirements of the Shakers’ unique social dynamic. That the Shakers were mostly situated in rural locations, inhabited by refugees from a foundering rural economy, only partly explains the inventiveness of Shaker cupboards.

Hyper-Regionalism and Mass Communications

Donna Baron’s discussion of the standardization and mass marketing of furniture during the early nineteenth century calls for an examination of a kind of hyper-regional response that coincided with its development. Specifically, we are led to a discussion of the mannered and conspicuously stylized furniture that was produced in places that may have felt threatened by the onslaught of urbanization, mass communications, and, eventually, the mass marketed furniture that put country joiners out of business. This phenomenon has been neglected in the past, but some tentative interpretations may be suggested from a reading of the furniture itself.

In traveling the back roads of New England and New York, it is immediately apparent that the early architecture and furniture in places like Canandaigua (fig. 26), Utica, and Painted Post, New York, and Castleton, Irasburg (fig. 27), Middlebury, and Chester, Vermont, displayed a pronounced local peculiarity. The impression of worldly and ambitious people marking their turf with an art of their own is overwhelming, especially when traveling from one region to the next. These mostly new communities, founded by educated lawyers, doctors, and entrepreneurs, published their own newspapers and were relentlessly expansionist;[24] nevertheless, at the very moment when these country towns, villages, and regional centers were becoming connected via turnpikes and mass communications, the need to articulate or preserve differences apparently intensified. At a time when pattern books, urban design sources, and other modes of transmitting cosmopolitan culture were finally more widely available, a sort of hyper-regionalism kicked in.

A recent Wall Street Journal article described a “global paradox,” noting that in spite of “the growth of the global economy and of more powerful transnational institutions, . . . nationalism is flourishing. . . . big corporations and institutions shaping the world economy seem so remote that many people turn to local ethnic groups and obscure languages for their identity.” Eventually, it noted, “the world may fracture into 500 states from the current 200, . . . with the central government little more than a shell and power residing in the regions.” Surely, the revolution in transportation and communications that swept America between 1790 and 1830 had as much impact on their time as the technological changes of today are having on ours. In Portsmouth and Haverhill, New Hampshire (see Zea, fig. 9), in Shaftsbury (see Zea, fig. 5) and Middlebury, Vermont (fig. 28), through western New York and Ohio,[25] and south into West Virginia (fig. 29), cabinetmakers and clients did a last tango around woodwork that was flamboyant and distinctive. If not a gesture of defiance to the homogenizing waves of progress, the items were at least a celebration of cultural control through art. Work that might have been labeled folk art twenty years ago as often as not belonged to well-traveled and educated regional professionals, movers and shakers fully aware of the choices they were making.

Ethnicity and Region

At a time when “cultural diversity” is widely equated with differences in ethnicity, perhaps there is value in demonstrating that regional diversity also has a long history in the United States. Indeed, ethnic differences are so conspicuous that they are nearly taken for granted. Dutch (fig. 30), French, Germans (fig. 31), Swedes, and Scotch-Irish have long been recognized as a significant presence in early America.[26] The discussion of ethnic subcultures is usually confined to the specific regions where their numbers were greatest; still, without leaving the Northeast one can find abundant evidence of ethnic diversity.

Philip Zea interprets the style of the Dunlaps—New Hampshire’s most renowned country joiners—as a product of their Scotch ancestry (see Zea, figs. 14, 27). Kevin Sweeney and Susan Prendergast explore the French Huguenot roots of the Wethersfield “sunflower” chests.[27] Neil Kamil shows how New York’s Huguenots positioned themselves at the center of a cosmopolitan cultural triangle involving New York, Boston, and London. But what of the German Palatines (fig. 32) in upstate New York, or the lingering influence of the French in Vermont and the Champlain Valley, or the continuing presence of Native Americans throughout the Northeast and the large concentrations of African slaves in places like Newport, Rhode Island (fig. 33)? There were “strangers” everywhere, and, often enough, they had wealth, connections, and new ideas (figs. 34, 35). How might their presence have affected the art and material culture of the various regions? A good road-trip survey or a walk through almost any old burying ground offers much evidence and more than a hint at new directions for research.

Several purposes were in mind when we set out to revisit the subject of regional furniture. As much as anything, we believe it worthwhile to create an American furniture history that more closely resembles the history of the people who lived here. In the usual chronologies of “style,” too much gets left by the wayside.[28] Given the abundance of high-style urban furniture, it is certainly possible to form dozens of public collections in which each period is represented by urban “examples” of the various “style periods”—nice and tidy, but redundantly bland. To be sure, it is more difficult to be inclusive and impossible to be comprehensive. Unfortunately, too much of what ends up on the cutting floor is the art that tells the richest story.

Implicit in the prospectus for the conference that lead to this collection of articles was the notion that diversity and innovation are somehow related. It is no accident that the industrial era in American history is brimming with the kind of inventors who gave rise to the myth of “Yankee ingenuity.” More often than not, these inventors—men like Samuel Colt, Eli Whitney, Charles Cheney—had roots in the trades. Without leaving the Connecticut Valley one can find numerous examples of legendary inventors who were both the lineal and spiritual descendants of rural artisans. The quality of inventiveness is partly a consequence of circumstances and partly temperament. Artisans working in the “out-and-beyond” inevitably learn to adapt. The capacity for self-teaching and the ability to strip problems to their absolute essentials, coupled with persistence, tenacity, and unusual curiosity, are characteristics of inventive minds, and these, more than a skill at marketing, management, or capital formation, are what distinguished many of the best rural artisans.[29] Their furniture solved problems inherent in bridging the gap between fashion and tradition, worldliness and a sense of place. The rules by which we measure their success should be not only aesthetic but situational.

The issues of art versus history, dependence versus independence, and international versus regional define the two-party politics of American furniture studies. Although one point of view may hold sway over the other, is it not good that both remain intact? Although we bunk, debunk, rebunk, and bunk again, in the end we share a purpose in seeking new ways of seeing old things. Furniture is art, but it is also a manifestation of the character and quality of place. With place-markers getting harder and harder to find, it is no small wonder that we can stare a chair in the splat and say, “I know you from whence you came.”

Early Western art critics and travel writers marveled at Japan’s sense of history and reverence for craft. Art reform critic and aesthetic designer Christopher Dresser described the importance of Shinto, the traditional state religion, in keeping “alive a sense of gratitude” in Japan: Its Architecture, Art and Art Manufacturers (1882; reprint, New York: Garland Publishing, 1977), p. 230. Legendary Japanophile, antiquarian, and collector Edward S. Morse of Salem, Massachusetts, wrote of the importance of collecting among Japanese nobility, citing centuries-old family collections of pottery, swords, brocade, and “roofing tiles” passed down with reverence, generation after generation, in Japan, Day by Day (1917; reprint, Dunwoodly, Ga.: Norman S. Berg, 1978), pp. 106–7; Morse further described a renowned Japanese antiquarian who “held it to be a solemn duty to learn any art or accomplishment that might be going out of the world, and then describe it so fully, that it might be preserved to posterity” in Japanese Homes and Their Surroundings (1886; reprint, Rutland, Vt.: Charles E. tuttle, 1972), p. xxxi. In Japan, antiquarianism is connected with the ancient rituals of the tea ceremony and “tea culture” (Richard L. Wilson, “Tea Taste in the Era of Japonisme: A Debate,” Chanoyo Quarterly 50 [1988]: 23–39). State and local historical societies were the pioneer institutional antiques collectors. The Massachusetts Historical Society has collected paintings and antiques since the time of its founding in 1791 (see Witness to America’s Past: Two Centuries of Collecting by the Massachusetts Historical Society [Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England, 1991]). The oldest continuously operated museum in the United States, Pilgrim Hall (founded 1820) has always concentrated on art and antiques. Elizabeth Stillinger’s The Antiquers (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1980), gave less attention to the earliest collectors and failed to mention legendary figures like George Sheldon of Deerfield (see Suzanne L. Flynt, Susan McGowan, and Amelia F. Miller, Gathered and Preserved [Deerfield, Mass.: Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association, 1991]) and Thomas Robbins of Hartford (see Robert F. Trent, “Thomas Robbins and Early Antiquarianism in New England,” lecture at the 1994 Winterthur Conference on “Perceptions of the Past: Private Collections/Public Collections,” [publication forthcoming]). These men—staunch regionalists all—were giants who layed the foundation for the work that followed. Stillinger profiled a few pioneer antiquarians such as the Rev. William Bentley (1759–1819) of Salem, “who collected a variety of things related to the history of Essex County”; John Fanning Watson (1779–1860) of Philadelphia, whose “study of colonial customs in his area” involved pioneering efforts at oral history, collecting antiques, and designing “relic furniture”; and Cummings Davis (1816–1896) of Concord, Massachusetts, whose “extraordinarily rich collection of the antiques of Concord” is the core of the Concord Antiquarian Museum (recently renamed The Concord Museum) (Stillinger, The Antiquers, pp. 17, 19, 22). The notion of “civic mission” is used by urban museums to describe service programs for and about the city or region where the museum is located. Although the priority given to the museums’ “global artistic mission” is typically undeclared, it plays out in the quest to be artistically correct and typically involves buying and exhibiting artists, both living and dead but never local, who have been vetted by the professional (and predominately commercial) networks devoted to such things. In 1993, I delivered a paper for the closing ceremony of Historic Deerfield’s Summer Fellowship Program on “The Role of Museums in Creating and Fostering Civic Identity.” I argued the importance of the role museums have to play in preserving “authenticity of experience” and “a sense of place in the face of an astonishing assault by our nation’s commercial popular culture.” What is indigenous or distinctive—a locale’s history, industries, and art, for example—is the only thing most places can still claim as their own. Although regional knowledge is not based entirely on indigenous stories and things, a place without them is unlikely to maintain or develop a strong or very durable identity or economy.

In an April 3, 1979, lecture at Winterthur, Brock Jobe, who was curator of Exhibition Buildings at Colonial Williamsburg, described John Graham as “a decorator” who set out to “acquire great objects and didn’t care if documentation got in the way.” The earliest attempt to furnish accurately a period room was Ivor Noël Hume’s “traveler’s” room in the Anderson House (Conversation with Graham Hood, January 1, 1995), but it was not until Hood’s arrival in early 1971 that the “old decorator tradition” began to give way to historic documentation. The Brush-Everard House, Raleigh Tavern, and Geddy House were the first properties to undergo major refurnishing; however, the greatest challenge involved refurnishing the Governor’s Palace—a veritable cultural icon. The Governor’s Palace is the signature building in the restoration and the most popular destination for museum visitors. Efforts to introduce historical accuracy in a building that epitomized Williamsburg’s role as tastemaker were amply chronicled in a special edition of Colonial Williamsburg Today 3, no. 3 (spring 1981) and in Michael Olmert, “The New, No-Frills Williamsburg,” Historic Preservation 37, no. 5 (October 1985): 27–33. Response was not always supportive. One long-time supporter described the restored buildings as “gloomy,” and at one point the administration received several letters of complaint per week. The Foundation responded with a candid, polite letter explaining the value of change and how John D. Rockefeller Jr.’s original intent was for Colonial Williamsburg to remain the leader in research pertaining to the town. As curator John Sands explains it (interview December 22, 1994), Colonial Williamsburg recognized that it was tampering with an icon cherished for reasons unrelated to the staff’s quest for historical authenticity and that some people would never accept the change. C. Knight, “Elegance Underground: The DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Gallery, Williamsburg, Virginia,” Architecture 75, no. 1 (January 1986): 52–55. “The New DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Gallery at Colonial Williamsburg,” Antiques 128, no. 4 (October 1985): 266–69.

Jane C. Nylander, Our Own Snug Fireside: Images of the New England Fireside, 1760–1860 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1993), is arguably the best recent example of what I call the “new antiquarianism.” Simply put, I believe that “material culture,” the banner under which revisionists attempted to unseat “the decorative arts” as the reigning ideology behind object study, failed to evolve into a program that followers could grasp or care for. The conflict at the heart of material culture and the decorative arts is, perhaps, best summarized by Michael J. Ettema’s controversial article, “History, Nostalgia, and American Furniture,” Winterthur Portfolio 17, nos. 2/3 (summer/autumn 1982), 135–44, and by the unprecedented outpouring of commentary from colleagues and professionals (see Winterthur Portfolio 17, no. 4 (winter 1982): 259–67. Ettema had little good to say about furniture studies or the decorative arts, and he was also critical of what he called “scientific antiquarianism” and the “antiquarian tradition.” He was searching for a program where objects are “used to enhance our understanding of history” rather than the other way around. I like to think of what I do as “object-based history,” not “art history,” recalling years ago a conversation with an art historian who preferred to be called a “professor of the history of art.” It is an important distinction. The merging of object study (involving connoisseurship) with social history is what “new antiquarians” do and, I believe, what antiquarians have always done to the limits of their ability and resources. Imagine Darret B. and Anita H. Rutman’s brilliant but visually challenged A Place in Time: Middlesex County, Virginia 1650–1750 (New York: W.W. Norton, 1984) with a dollop of object knowledge, or imagine an illustrated version of Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s A Midwife’s Tale: The Life of Martha Ballard, Based on Her Diary, 1785–1812 (New York: Vintage Books, 1990), and you begin to see visually rich, human narrative the equal or better of film in communicative power. In addition to Jane Nylander’s work, Richard Bushman’s The Refinement of America (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1992); Elisabeth D. Garrett’s At Home: The American Family, 1750–1870 (New York: Harry Abrams, 1990); and several of the marvelous and underexposed exhibition catalogues produced by the staff at the Margaret Woodbury Strong Museum in Rochester, New York, show what is possible when object knowledge and documentary resources are deftly deployed with the aim of rendering the past. Ultimately, this work is either that of gifted generalists or teams of collaborating specialists, hence it flourishes outside the academy where the tradition of scrupulously segregated fields of study continues to suppress the kind of multidisciplinary work that I regard as essential to the task of rendering the past or even rendering American furniture as more than “superficial and decorative.” John T, Kirk, “Source of Some American Regional Furniture,” Antiques 88, no. 6 (December 1965): 790–97.

The passages cited are from E. McClung Fleming, “Foreward,” and Charles F. Hummel, “The Dominys of East Hampton, Long Island, and Their Furniture,” both in Country Cabinetwork and Simple City Furniture, edited by John D. Morse (Charlottesville, Va.: University Press of Virginia for the Winterthur Museum, 1970), pp. xi, 67. The conference took place March 27–29, 1969, a year after the Antiques issue on “country furniture” and after the tumultuous Democratic National Convention in Chicago. Country Cabinetwork was originally billed as a conference on “less sophisticated furniture.” Winterthur Newsletter 15, no. 3 (March/April 1969): 5. Wendell D. Garrett, “The Matter of Consumer’s Taste,” Winterthur Newsletter 15, no. 3 (March/April 1969): 210. To me and to several of the conference participants (cited in the transcription of the post-lecture roundtable discussions, p. 281), the most intriguing idea in Garrett’s essay was the notion of “artisan mannerism,” a phenomenon not fully developed in the essay or in the other associated papers. Garrett’s emphasis on social context and labor history, witnessed in the citing of then au courant revisionist literature, such as Barton J. Bernstein’s, Towards a New Past: Dissenting Essays in American History (New York: Pantheon Books, 1968), helped move the emphasis from issues of place to issues of politics

Henry D. Green, Furniture of the Georgian Piedmont Before 1830 (Atlanta: High Museum of Art, 1976); Robert E. Winters Jr., ed., North Carolina Furniture 1700–1900 (Raleigh: North Carolina Museum of History, 1977); Robert F. Trent with Nancy Lee Nelson, “New London County Joined Chairs, 1720–1790,” Connecticut Historical Society Bulletin 50, no. 4 (fall 1985); James R. Melchor, N. Gordon Lohr, and Marilyn S. Melchor, Raised-Panel Cupboards of the Eastern Shore of Virginia (Norfolk, Va.: Chrysler Museum, 1982); Dean F. Failey, Long Island Is My Nation: The Decorative Arts and Craftsmen, 1640–1830 (Setauket, N.Y.: Society for the Preservation of Long Island Antiquities, 1976); E. Jane Connell and Charles R. Muller, “Ohio Furniture 1788–1888,” Antiques 125, no. 2 (February 1984): 462–68; Edwin A. Churchill and Sheila McDonald, “Reflections of Their World: The Furniture of the Upper St. John Valley, 1820–1930,” in Ward, ed., Perspectives on American Furniture, pp. 63–92. Since 1975, the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts’s Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts has been the leading forum for scholarship on southern antiquities. Scott T. Swank et al., Arts of the Pennsylvania Germans (New York: W.W. Norton for the Winterthur Museum, 1983); and Roderic H. Blackburn and Ruth Piwonka, Remembrance of Patria: Dutch Arts and Culture in Colonial America, 1609–1776 (Albany, N.Y.: Albany Institute of History and Art, 1988).

Robert Blair St. George, The Wrought Covenant: Source Materials for the Study of Craftsmen and Community in Southeastern New England, 1620–1700 (Brockton, Mass.: Brockton Art Center, 1979); and David Grayson Allen, In English Ways: The Movement of Societies and the Transferral of English Local Law and Custom to Massachusetts Bay in the Seventeenth Century (Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 1981). Jonathan L. Fairbanks and Robert F. Trent, eds., New England Begins: The Seventeenth Century, 3 vols. (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1982). Among the many valuable contributions made by this milestone exhibition, the idea that seventeenth-century New England was peopled by settlers who “transferred their entire culture to the New World, maintained strong ties with England, . . . and enjoyed a complex geometric, artificial, and colorful artistic style now called Mannerism” (p. xvii) now seems somewhat reductionist. Layering example upon example of “transferral” and dependence, New England Begins virtually ignored the possibility of invention. The one chapter that focused on furniture (Robert F. Trent, “New England Joinery and Turning before 1700,” pp. 501–50), although a brilliant analysis of craft and style, mostly illustrates objects that are emphatically derivative. Where Hadley chests are discussed (p. 529), the narrative trails off with a disclaimer that “it is impossible to suggest any exact origin for them” but that tracing “Connecticut River Valley craftsman to England’s North Country may someday provide a valuable clue.”

The origins of the idea of “Yankee ingenuity” are not clear. It may have originated, and was certainly stimulated, by the success of New England manufactured products (notably the firearms manufactured by Robbins & Lawrence in Windsor, Vermont, and the revolvers manufactured by Samuel Colt in Hartford, Connecticut) at the 1851 Crystal Palace Exhibition (see Brooke Hindle and Steven Lubar, Engines of Change: The American Industrial Revolution, 1790–1860 [Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1986]; Nathan Rosenberg, “Why in America?” in Yankee Enterprise: The Rise of the American System of Manufacturers, edited by Otto Mayr and Robert C. Post [Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1981], pp. 49–62). As early as 1851, a Hartford newspaper described New England’s “laying claim . . . to extraordinary ingenuity and inventive power,” as if it were then already a part of the mythology of the region (Hartford Daily Times, August 1, 1851). An 1855 article on “Connecticut Manufacturers” claimed that the nation’s “largest axe factory,” “largest clockmaking establishments,” “most numerous and extensive paper mills,” and “largest silk factory” were in Connecticut and noted how glass bottles, silverware, guns, clothespins, pianos, scythes, oars, coffee mills, steam engines, pewter ware, “and a hundred other things, are made in Connecticut, whose sons are famous for ingenuity and honest industry” (Hartford Times, July 12, 1855). Hank Morgan, Mark Twain’s fictional “Yankee inventor” in A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (1889), describes a personal history that could as easily have been that of the regional joiners and blacksmiths: “My father was a blacksmith, my uncle was a horse doctor, and I was both. . . . Then I went over to the great arms factory and learned my real trade; learned all there was to it; learned to make everything; guns, revolvers, cannon, boilers, engines, all sorts of labor-saving machinery. Why I could make anything a body wanted—anything in the world . . . and if there wasn’t any quick new-fangled way to make a thing, I could invent one—and do it as easy as rolling off a log.” Daniel V. DeSimone, “The Innovator,” The Engineer 8, nos. 1, 2 (1967), in Dartmouth Readings in the History and Philosophy of Technological Development: The Invention and Development Phases, edited by Joseph J. Ermenc (Hanover, N.H.: unpublished manuscript, Thayer School of Engineering, Dartmouth College, 1977), pp. 267–71. Tom D. Crouch, “Why Wilbur and Orville? Some Thoughts on the Wright Brothers and the Process of Invention,” in Inventive Minds: Creativity in Technology, edited by Robert J. Weber and David N. Perkins (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992), pp. 80–81. The Wright brothers were noted for their “relentless drive and will, their ability to look skeptics and rivals in the eye without blinking,” and for their “hard-edged and uncompromising personalities.”