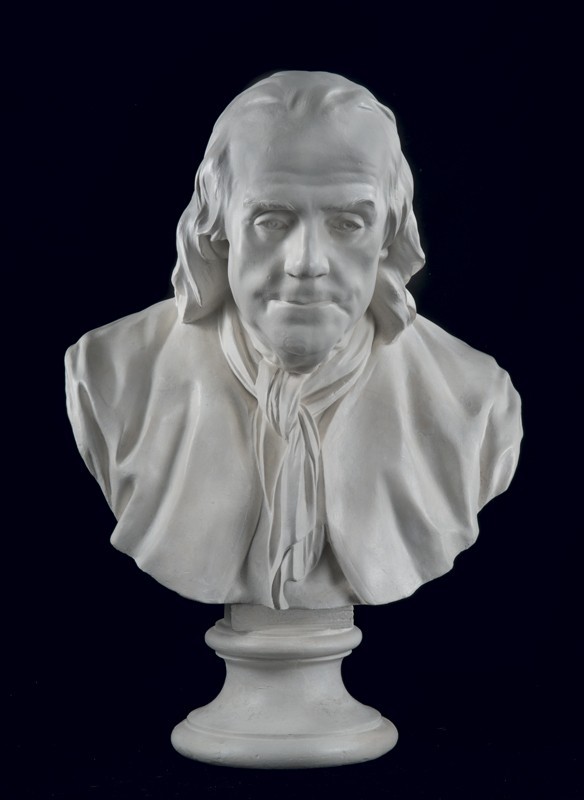

Bust of Benjamin Franklin, attributed to Martin Jugiez, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1779-1790. White pine; iron. H. 35", W. 21", D. 14 1/2". (Courtesy, Sotheby’s.)

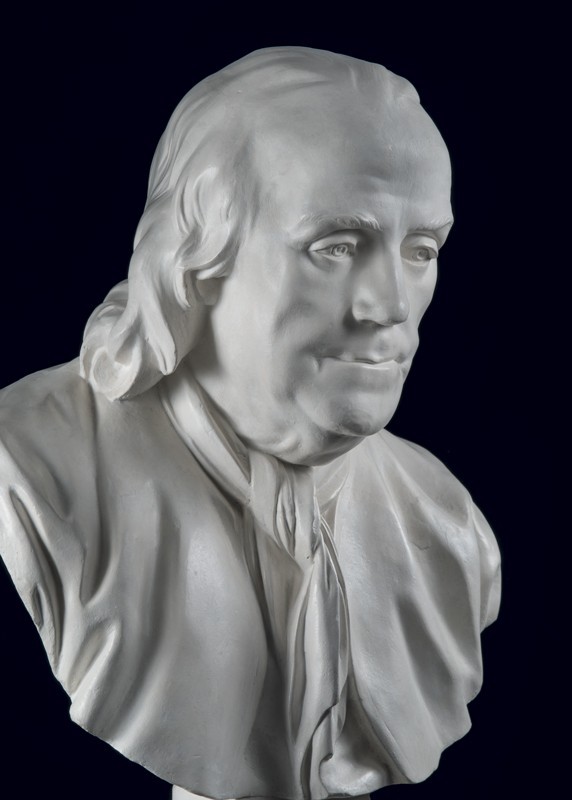

Bust of Benjamin Franklin, attributed to William Rush, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1787. White pine. H. 20 1/4", W. 16 1/4", D. 13". (Courtesy, Yale University Art Gallery.) According to Linda Bantel’s catalog entry in William Rush, American Sculptor (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 1982), p. 97, this bust “has been in the collection of Yale College since 1804.” It was described as “a “Bust of Dr. Franklin carved by Rush. . . . taken from life . . . [and] presented by Dr. Franklin to his friend Isaac Beers Esq.”

Chimney back, Marlboro Furnace, Frederick County, Virginia, c. 1770. Cast iron. H. 34 1/2", W. 31". (Courtesy, United States Army Engineer Museum, Fort Belvoir, Virginia; photo, Robert Hinds.)

Pier table with carving attributed to Martin Jugiez, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, c. 1765. Mahogany with white oak; marble. H. 32 1/2", W. 62 3/4", D. 31 5/8". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Finial bust of John Locke, attributed to Martin Jugiez, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, c. 1770. Mahogany. H. 10 1/2". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the lion head on the pier table illustrated in fig. 4. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Pre-conservation oblique view of the bust illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Portrait bust of Antoninus Pius, Roman, 140-165. Marble. Dimensions not recorded. (© The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.)

Finial bust, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, c. 1770. Mahogany. (Private collection; photo Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the left eye of the bust illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the left eye of the lion on the pier table illustrated in fig. 4. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the left eye of the bust illustrated in fig. 5. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Frontal view of the bust illustrated in fig. 1 with outer layer of paint removed. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Jean-Jacques Caffieri, Benjamin Franklin, Paris, France, 1777. Terra-cotta. H. 27". (Courtesy, Biblioteque Mazarine; photo, Bridgeman Images.)

Jean-Jacques Caffieri, Benjamin Franklin, Paris, France, 1779–1805. Plaster. H. 28". (Courtesy, New-York Historical Society; gift of Dr. David Hosack.)

Oblique detail of the bust illustrated in figure 1 with outer layer of paint removed. (Photo, Scott Nolley.)

Oblique detail of the bust illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

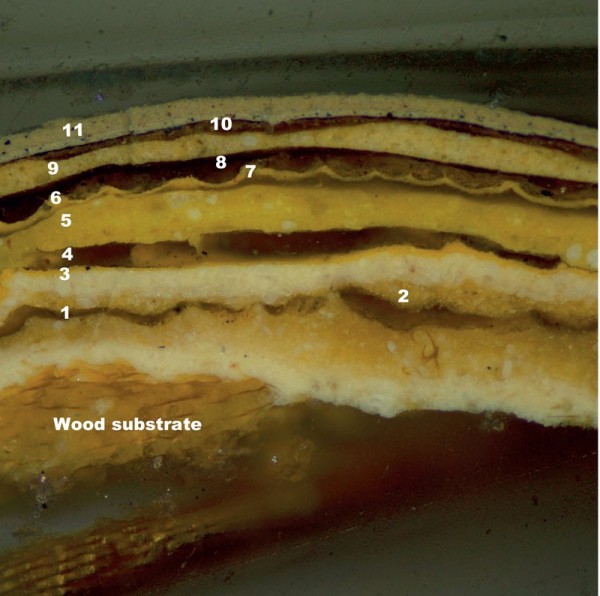

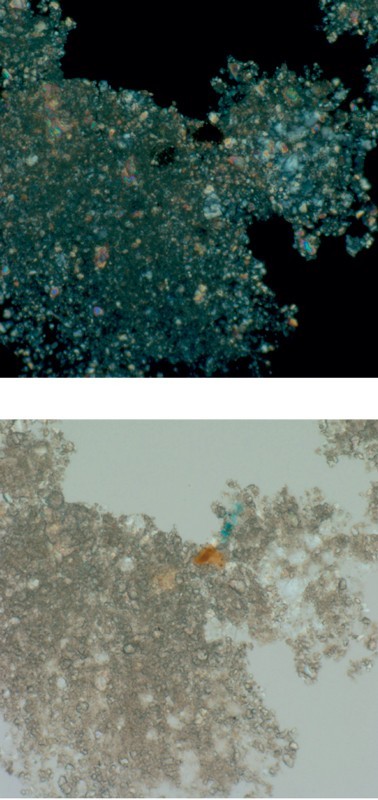

This cast sample from the interstices of the carved hair was photographed at 100x in reflected visible light. The cross-section reveals that there are 11 generations of varnishes and oil-based paints in the stratigraphy. The first generation consists of a grayish-white primer on top of the wood fibers at the bottom of the sample. There is a tannish base coat on top of this primer, followed by a gray glaze and a transparent varnish. There are remnants of gold leaf on top of a yellow base coat in the second generation. Gold leaf can be discerned on top of yellow base coats or varnishes in generations 2, 3, 4, 6, and 9. The varnish layers are transparent in reflected visible light, but are readily identifiable in reflected ultraviolet light. Bronze powder paint was applied in the tenth generation, and there are two applications of the most recent drab grayish paint at the top of the cross-section.

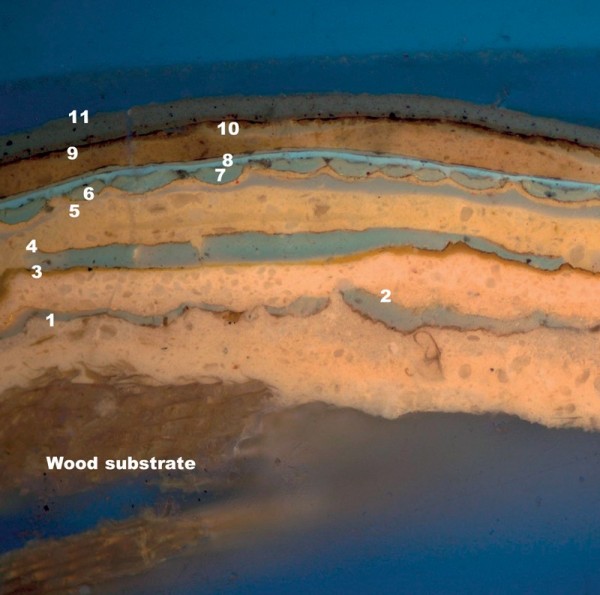

The cast sample from the interstices of the carved hair was also photographed at 100x in reflected ultraviolet light. The original pigmented grayish glaze on top of the tannish base coat is more obvious here than in reflected visible light. There are 11 generations of coatings in the stratigraphy, and there are plant resin varnishes in generations 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 8. These varnishes have a slightly quenched autofluorescence which is typical of natural resin-oil mixtures. The light bluish autofluorescence of the varnish applied in the seventh generation, on top of the sixth generation deeply cracked and dirty plant resin varnish, suggests it may be synthetic resin-based. The bright edges of the gold leaf layers in generations 2, 3 and 6 can also be seen where the leaf layers are turned over.

Pigments were scraped from the original base coat layer and analyzed at 1000x in plane polarized transmitted light, and with the polarizing light filters crossed for darkfield illumination. The pigments were identified based on their characteristic shapes, sizes and optical properties. The base coat was found to be made of a combination of tiny white lead pigments; larger translucent calcium carbonate particles; a few scattered burnt umber pigments; irregularly dispersed clumps of Prussian blue; and a few tiny sooty lampblack particles. These pigments are all consistent with eighteenth-century paints.

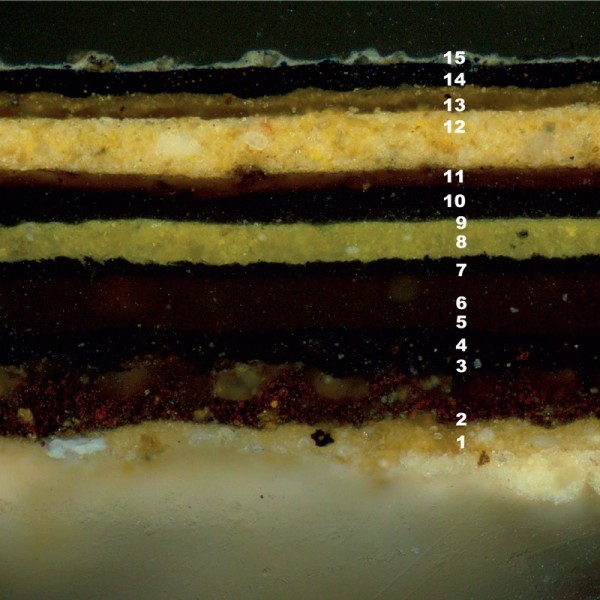

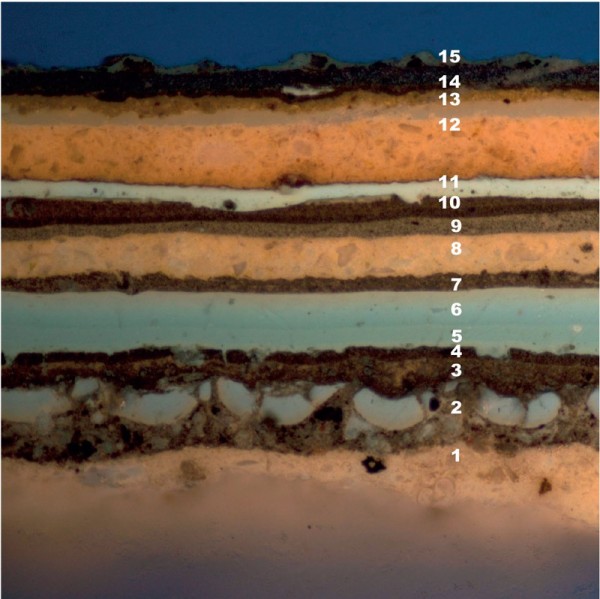

The evidence in the visible and ultraviolet light cross-section images photographed at 200x shows that earliest coatings from the base are damaged and disrupted, suggesting it was exposed to more exterior weathering and/or excessive heat than the bust. The comparative evidence indicates that the base was originally painted to match the rest of the sculpture, but it was subsequently painted dark brown, and then frequently repainted black or varnished. Fifteen generations of coatings were found on the base, compared to 11 on the bust, so perhaps it required more repairs or repainting because of exterior exposure. No gold leaf layers were found on the base.

The reflected ultraviolet light cross-section image at 200x from the base shows that the original tannish base coat and grayish glaze are more cracked and dirty than on the bust. There is a deeply cupped and cracked plant resin varnish on top of the brown paint in the second generation. This level of damage suggests the base was left exposed for an extended time to high heat and/or exterior weathering. After the second generation the base was painted black in generations 3, 4, 7, 9, 10, and 14, and varnished in generations 2, 5, 6, and 11.

“The portraiture of gods and famous men demands a standardization of the image. For deification to be successful, the worshipers should be of one mind upon the visual focal point.”

—Charles Coleman Sellers, Benjamin Franklin in Portraiture

At Sotheby’s Important Americana sale in January 2016, the Chipstone Foundation purchased a life-sized, carved wooden bust of Benjamin Franklin cataloged as “American school . . . executed circa 1785–1795, probably in Philadelphia” (fig. 1). That attribution was based on the object being made of white pine, its provenance, and its publication history. This essay will survey previous scholarship on the bust, identify its carver, and shed new light on the historical context in which this sculpture was created and used.[1]

The early history of the bust is unknown. Antique dealer David Stockwell reputedly acquired the object from Philadelphia collector John Morris Scott during the 1940s. Stockwell loaned the bust to the Delaware Historical Society, where he served as chair of the Museum Committee, around 1968 and donated it in 1979. After consignments to Hirschl & Adler and Peter H. H. Davidson & Co. failed to produce a sale, the society placed the bust at auction in 1982. Antique dealer and folk art scholar David Schorsh purchased the object and subsequently sold it to Stamford, Connecticut, dealers Rocky and Avis Gardiner. The Gardiners appear to have sold the bust to High Ridge Books of Rye, New York. By 1989, the bust was in the collection of the Haydn Foundation for the Cultural Arts. The foundation apparently sold the bust to a private collector who consigned it to Hirschl & Adler by 2010. Presumably that collector was the consignor at the Sotheby’s sale.[2]

While in the collection of the Delaware Historical Society, the bust became associated with William Rush, a Philadelphia ship carver described as “America’s first native sculptor.” Art historian Wayne Craven ascribed that object to Rush in 200 Years of American Sculpture (1976), but his attribution was subsequently refuted by Linda Bantel. Her catalog entry for the bust in William Rush, American Sculptor (1982) cited stylistic and technical departures from the ship carver’s work, most significantly differences in the sculpting of the eyes (fig. 2). Uncertainty regarding the attribution probably accounted for the bust’s poor performance in the marketplace prior to 2016.[3]

Before the Sotheby’s sale, the authors determined that the bust was carved by Martin Jugiez, an émigré craftsman active in Philadelphia by 1762. On November 25 of that year, the Pennsylvania Gazette reported:

Just imported . . . from London, and to be sold by BERNARD and JUGIEZ . . . at their Looking-Glass Store on Walnut-Street between Front and Second-Streets . . . A Compleat assortment of Looking-Glasses, framed in the newest Taste, Picture Frames, Sconces, Chimneypieces, Ornaments for Ceilings, Pictures Framed and Glazed, [and] a neat Harpsichord.

Bernard and Jugiez’s extensive inventory and apparent establishment of credit abroad suggests that their firm had been in business for some time.[4]

Many examples of furniture and architectural carving documented and attributed to Jugiez survive, but the objects most relevant to the attribution of the Franklin bust are a chimney back cast at Marlboro Furnace in Frederick County, Virginia (fig. 3), a pier table with a lion head on the front rail (fig. 4), and three busts of English philosopher John Locke (fig. 5). Unlike much colonial American carving, which was done in a two-dimensional linear style, Jugiez’s finest work is sculptural. He had a profound understanding of spacial relationships and how his carving would look when viewed from a distance. Although nothing is known of Jugiez’s apprenticeship or work as a journeyman abroad, his efficient tool use, capacity to carve three-dimensionally, and professed ability to work “in wood or stone,” suggest that he trained in a major urban shop.[5]

The chimney back was cast from a pattern carved for iron master Isaac Zane and commissioned by his brother-in-law John Pemberton (fig. 3). On December 20, 1770, Pemberton paid Bernard and Jugiez eight pounds “for the Arms of Earl of Fairfax for a Pettern for the back of a chimney.” Although the pattern is not known to survive, the castings from it are remarkable for their depth and naturalism. This work is particularly impressive when one considers that Jugiez had to avoid undercuts, which would prevent the pattern from drafting cleanly out of the sand. Even when carving in this imposed low relief, his sculptural ability was remarkable.[6]

Although the casting shows the lion’s head in profile, the animal’s mane, forehead, eyes, and nose are virtually identical to those of the lion on the pier table (fig. 6). In modeling the lions’ brows, Jugiez used shallow gouges with the blade turned upside down, an approach repeated in his sculpting of the forehead on the Locke busts. The Locke bust illustrated in figure 5 is the finest in the group, featuring naturalistically modeled cheeks, a well-defined nose and lips, and eyes with heavy lids—features found on contemporary ceramic and plaster versions of Locke. Like most figural busts produced by eighteenth-century Philadelphia carvers, Jugiez’s were probably inspired by imports. In 1765 he and Bernard advertised a “variety of neat figures and busts in plaister of Paris, with brackets for ditto.”[7]

The bust of Franklin differs from other sculptural work attributed to Jugiez in scale but not in technique (fig. 7). This is clearly seen in the carver’s treatment of the hair on Franklin and Locke and the mane of the lion on the pier table. The larger tufts overlap each other in rhythmic succession, and Jugiez’s modeling and shading cuts give them the appearance of curling into and out of view. Jugiez used similar techniques for flame finials, which typically open into S-shaped sections that spiral slightly at the top. The sculpting of the eyes on Jugiez’s busts is equally distinctive. Eyes represent much of the narrative content of a sculpture, but, if treated only as surface forms, as was the case in many classical Roman portrait busts, the iris and pupil are not differentiated from the white of the eye because they all share the same contour (fig. 8). This lack of differentiation can be seen on two portrait busts of John Milton, which were carved by one of Jugiez’s Philadelphia competitors (fig. 9). For a painter, it is easy to differentiate the components of the eye because they are different colors. Sculptors faced a greater challenge in representing the eye anatomically, but Jugiez developed a complex and effective method. He outlined the border of the iris and sclera (white of the eye) and then incised the border of the pupil and iris leaving the center of the pupil at the level of the circumference of the eyeball. He then shaded or deepened the iris’s circumference toward the border with the sclera, making the iris appear darker than the sclera, just as it appears in life. The raised centers of the pupils, while hardly anatomically correct, avoid the “dead eye” appearance created when the entire pupil is rendered as a deep hole. Jugiez used these techniques to depict the eyes of Franklin and the lion on the pier table (figs. 10, 11). For his likenesses of John Locke, he employed a simplified approach, leaving the whole pupil concave—a method effective for busts that small size (fig. 12).

The Franklin bust is the latest sculptural work associated with Jugiez and probably dates from the late 1770s to circa 1800 (fig. 13). As a result, it could have been made during his partnership with Bernard or after. By 1783, Bernard and Jugiez were operating separate businesses. The Philadelphia tax assessment for that year listed Bernard as a shopkeeper in the South Ward and Jugiez as a carver in the Middle Ward. In 1785, Jugiez and Philadelphia painter and gilder George Rutter requested payment of £112 from the general assembly of Pennsylvania for painting, framing, and installing the state coat of arms “over the seat of the Supreme Court of Judicature,” and three years later Jugiez marched with other carvers in the Grand Federal Procession in Philadelphia. City directories indicate that Jugiez worked until his death in 1815. He signed his will on July 9 of that year, leaving $100 to his nephew Jerome and the remainder of his estate to “my beloved friend John Bernard and his Heirs.” The bonds of friendship that formed during Bernard and Jugiez’s partnership, and possibly earlier, were incredibly strong. When Bernard signed his last will and testament in 1789, he requested that his family care for Jugiez if he became “necessitated.”[8]

Although there is no documentation regarding Jugiez’s production of the Franklin bust, it clearly imitated a likeness created by renowned French sculptor Jean-Jacques Caffieri (fig. 14). Franklin’s scientific pursuits earned him international acclaim during the 1750s, and his reputation grew exponentially during his residences abroad. In October 1776, Franklin traveled to Paris to secure a treaty and alliance with France for the Continental Congress. During his tenure as “ambassador” there, he socialized and collaborated with aristocrats, politicians, writers, philosophers, scientists, and artists, including Caffieri.

In Benjamin Franklin in Portraiture (1962), art historian Charles Coleman Sellers speculated that Franklin’s introduction to Caffieri may have been facilitated by his friend and neighbor in Paris, Anne-Catherine de Lingniville Helvetius. Caffieri had sculpted a marble bust of her husband, philosopher Claude-Adrien Helvetius, in 1773. Four years later Franklin commissioned Caffieri to produce a terra-cotta bust of himself, and shortly thereafter gave the sculptor a deposit for a monument to Richard Montgomery on behalf of the Continental Congress. On March 26, 1777, Caffieri wrote Franklin, requesting him to schedule a final sitting for his bust. The bust was completed by the following autumn and exhibited at the Salon du Louvre with the Montgomery monument and two other works by Caffieri. Although the French government purchased the sculptor’s original terra-cotta of Franklin for the royal collections, Caffieri made several plaster casts for Franklin, who gave them to family and friends. On December 9, 1777, he presented Franklin with the first casting, asking that no other artist be allowed to copy it. According to Sellers, the correspondence between Caffieri and Franklin contains eight references to plaster casts from the bust. The statesman’s grandson William Temple Franklin apparently received the first casting. In a letter dated July 18, 1817, William wrote that he had a bust of Benjamin Franklin “large as life and executed by Caffieri an eminent artist at Paris from the life.” A March 17, 1779 letter from the sculptor to William, who had accompanied his grandfather to Paris, refers to three plaster casts packed for shipment, presumably to America. Although the number of castings shipped to America is unknown, the Library Company of Philadelphia received one as a gift from Walter Franklin in 1805. Dr. David Hosack gave another to the New-York Historical Society in 1832 (fig. 15). Sellers speculated that the Library Company had received another casting fifteen years earlier, but the source he cited did not mention Caffieri nor describe the medium of the object. What is clear is that castings of Franklin by Caffieri and other European sculptors copying his work were available as sources for Jugiez (figs. 16-17). Italian sculptor Giuseppe Ceracchi, who arrived in Philadelphia in 1790, produced several marble derivatives based on Caffieri castings.[9]

Jugiez’s bust may have been commissioned for a public building associated with Franklin. Likely candidates are the Pennsylvania State House (Independence Hall), the Pennsylvania Hospital, the Pennsylvania Academy of Arts and Sciences, and Carpenter’s Hall. Franklin was a founder of the hospital and the academy as well as two organizations that made use of Carpenter’s Hall—the American Philosophical Society and the Library Company of Philadelphia. Scholar Keith Arbor speculated that Jugiez’s bust might have been the one described as being over the southeast door of the House Chamber in the State House by Henry Wansey in 1794, but there is no documentary evidence that the carver did work for that building.[10]

The Pennsylvania Hospital is the only building connected to both Franklin and Jugiez. In her entry for the hospital in Philadelphia: Three Centuries of American Art, decorative arts scholar Beatrice B. Garvan documented Jugiez’s production of Ionic capitals for the columns in the rotunda between 1797 and 1799. Although the early history of the lion mask table is unknown, it was reputedly found in the hospital in 1926, which prompts speculation that Jugiez made the table for the hospital or for a patron who donated it to that organization. The Pennsylvania Hospital apparently owned a bust of Franklin, which was subsequently acquired by the Library Company of Philadelphia. At a meeting of the Library Company held on January 7, 1790, “the Committee appointed for the purpose report that a Bust of Doctor Franklin has been purchased from the Managers of the Pennsylvania Hospital.” Although this evidence is insufficient to prove that this Franklin bust is the one sculpted by Jugiez, the carver’s connections to the hospital make that theory plausible.[11]

William Rush trained as a ship carver under Edward Cutbush and, in his later career, could fairly be described as a ship carver working as a sculptor. Martin Jugiez, on the other hand, was a sculptor who typically worked as a furniture carver. It is hardly surprising that, when commissions provided the opportunity, his sculptural prowess was manifested so clearly. The Franklin bust is not the three dimensional equivalent of a limner painting, like most American colonial and early republic carved figures, but a confident and expressive work of sculpture.

Exploring the Paint and Gilding History of the Benjamin Franklin Bust

SUSAN L. BUCK

When the bust was examined early in 2016, its murky, greenish-gray paint gave it a grim appearance (fig. 18). But it was also possible to see spots of bright gold in the areas where the paint had flaked away. When the bust was examined at low magnification the thick accumulations of paints, glossy varnishes and reflective gilding layers were obvious at the edges of the paint losses. This suggested that the bust had never been stripped, but it was not clear how it had been originally painted. Ten samples slightly larger than a pinhead were taken with a scalpel from protected areas of the bust and the base in order to compare the paint histories on different elements. The goal was to use the information provided by cross-section microscopy analysis to decipher its original appearance, and, if appropriate, to guide removal of the later overpaints to reveal the original decoration.

The best samples were cast in small polyester resin cubes and polished to expose the cross-sections of wood fibers and attached coatings. Comparative cross-section microscopy analysis revealed that there were eleven generations of decoration remaining on most of the areas sampled. Sample 1 from the carved hair contains a full stratigraphy of coatings (figs. 19, 20). It reveals that the wood was first prepared with a gray-white primer, followed by a tannish base coat, then a grayish-brown glaze, and a plant resin varnish.[12]

This sequence of layers is consistent with a traditional faux finish, such as marbleizing or faux bois, which typically begins with a neutral primer, followed by a base coat that mimics the lightest color of the wood or stone to be imitated, then glazes to create the figure of the wood or pattern of the stone, and finally a varnish coating to protect the glazes and create a glossy finished surface. The colors in the original base coat and glaze suggest that the bust was intended to resemble stone. When the cross-section images of the samples from different areas were aligned, it was apparent that all the elements of the bust—hair, face, ears, clothing, base—were originally painted in the same manner.

To interpret the paint stratigraphies it was necessary to compare the reflected visible and ultraviolet (UV) light cross-section images. In reflected UV light the plant resin varnishes in generations 1, 3, 4, 6 and 8 are distinguished by their whitish autofluorescence colors, while generation 7 may be a synthetic resin varnish coating based on its bluish autofluorescence color. It is also possible to discern the gold leaf layers in reflected UV light because of the bright gold reflections where each leaf layer was folded or turned on its edge.[13]

Pigments were also separated out from the original base coat for plane polarized transmitted light microscopy analysis which revealed that the original grayish-white primer is composed of white lead, calcium carbonate, and scattered burnt umber, Prussian blue and lampblack pigments (fig. 21). These pigments are all consistent with eighteenth-century paint-making practices.[14]

There are multiple generations of gold leaf applied on top of yellow preparatory layers in generations 2, 3, 4, 6, and 9. This evidence indicates that after the first generation, the bust was gilded to appear more expensive, and far more dramatic. Many of these gold leaf layers were varnished over for protection and saturation. More recently, bronze powder paint was applied in generation 10, which would have initially looked like gold until it began to degrade and tarnish. Several years of exposure to exterior weathering or perhaps a decade of interior exposure would have certainly caused the bronze-powder paint to degrade to dull brown. So, the combined evidence from the ten cross-sections indicates that for nine generations this bust was intended to look like gold.

The comparative cross-sections indicate that the plinth was originally painted to match the bust, but it was repainted more frequently than the bust. As early as the second paint generation the plinth was painted dark brown, and then repeatedly painted black or varnished (figs. 22). No gold leaf was found in the fourteen generations of coatings identified in the two samples from the plinth. It is significant that the earliest paints and varnishes on the plinth are deeply cracked and disturbed. This type of damage is typical of exterior coatings exposed to extremes of temperature and moisture, suggesting that this bust was displayed outside for at least an early part of its life, and that the plinth was more exposed to weathering than the rest of the bust.

Binding media characterization with biological fluorochrome stains (TTC, FITC, DCF and RHOB) showed that all the paint layers are oil-bound. The earliest paints reacted more weakly for the presence of oils with DCF and RHOB, suggesting these paints were either more leanly bound, or more weathered (which caused leaching of the oil binders). The two most recent paints also reacted positively for proteins with FITC, which are likely modern surfactant (with amine groups) additives to the paint layers, suggesting the last two generations of paint could date to the twentieth century.[15]

The missing or disrupted early layers in several of the samples are likely the result of accidental abrasion or cleavage, but there is no evidence of deliberate paint removal or cleaning. The evidence indicates that the bust was regularly recoated without removing the layers below, which resulted in thick accumulations of paints in the interstices of the carving.

This modest optical microscopy analysis project provides substantive information about the original appearance of the bust, and about how it was later gilded to appear grander and more important. It also suggests that the bust was initially displayed in an outdoor location because of the extreme degree of weathering of the early coatings on the plinth. From the perspective of conservation treatment, it is a great boon that this bust was never cleaned or stripped as all the coating evidence remains in situ from the time it was created to the present. However, these thick accumulations of coatings do obscure the details of the carved hair and the delicacy of the facial features. Fortunately, the evidence provided by the cross-sections also provides some clues to the composition and relative solubility of the later paints and varnishes which can help with selective overpaint removal. This type of significant wood sculpture rarely survives with its paint and gilding history intact, and any conservation treatment must also respect the importance of this paint evidence by leaving sections of untouched paint on protected areas of the bust and the plinth for future examination and research.

It must be noted that cross-section microscopy analysis provides clues to the original appearance of the bust. But the only way to fully understand the original intent of the painter is to do overpaint removal tests that carefully remove the later coatings to reveal the original decorative surface. The samples were taken from the crevices in the carving, so they may not represent the entirety of the initial decoration. A conservation treatment that involves significant overpaint removal may uncover surprising information about how the bust appeared when it was freshly painted. It may also provide some evidence about how soon the original paint and varnish was gilded over.

Observations on Jugiez’s Bust of Benjamin Franklin and Its Treatment

SCOTT NOLLEY

The source timber of Jugiez’s bust, oriented in a natural, vertical direction displays a marked degree of radial checking—cracking that develops along the radius of a log as a result of moisture loss—in this instance, apparently due to exposure to the elements. The interior faces of individual cracks display a dark staining suggesting mold and mildew infestations over time, and there are a number of campaigns of fill—putty and gesso-like materials—applied in these voids, largely to compensate for the resulting losses and voids over the portrait image. The integral base displays a marked degree of cracking and splitting—damages whose interior surfaces have simply been brushed with paint during restoration attempts.

The cross-sectional analysis carried out by Susan Buck is accurate in its general characterization of the complex paint laminate and surface treatment of the figure. The physical history of the bust—the conditions of its display and campaigns of “resurfacing” punctuated by numerous impact damages and local applications of fill and pigment/binder formulations—became clearer as the conservation treatment proceeded. The uppermost, visible gray-green color exists as two applications with intermittent filling and retouching to both applications carried out over time. Beneath these layers were irregularly applied areas of a metallic flake paint. The application of this material was intermittent and appears to have been applied to compensate for loss to the gold leaf below resulting from abrasion and impact damages, as well as to tone fills that were affected at this point along the object’s surface treatment timeline.

The multiple applications of gold leaf represent a significant commitment to the presentation of the portrait image as a gilded form. Empirical observations made during the treatment steps that resulted in the reduction of the gray-green pigment from the bust reveal not only the five layers of gilding identified in the cross-sectional analysis, but also a number of local applications of yellow ground, gold-colored metallic leaf and toned varnishes that appear to be associated with repairs to the damaged leafed surfaces below.

The decision was made to reduce the accumulated gray-green paint(s) instead of revealing the gold leafed presentation surface of the figure. Both treatment steps resulting in this revelation, as well as the cross-sectional analysis, gave evidence to a degraded and compromised paint laminate below—an original treatment that evidence suggests may have presented the work with a “faux stone” surface. The layers that comprise this generation of decoration appear somewhat degraded and cracked, as well as solvent sensitive. The inherent nature of this irregular application of a base color followed by subsequent applications of toned or pigmented varnishes as to mimic stone was thought to have been too fragile to successfully recover—the toned faux finishes being vulnerable to the solvents and cleaning agents that would have been required to reduce the gold leaf applications. Cleaning tests using various laser technologies also produced challenging and irregular results.

The gray-green paint was reduced from the gilded surfaces and a controlled campaign of filling was carried out, largely to restore visual integrity to the lyrical contours of the form. Fills were toned to match using shell gold, a genuine gold powder finely ground and dispersed in gum Arabic to form a solid watercolor pigment block.

Charles Coleman Sellers, Benjamin Franklin in Portraiture (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1962), p. 179. Sotheby’s, Important Americana, New York, January 22–23, 2016, pp. 190–91, lot 1590.

E-mail from Jennifer Potts, Curator of Objects, Delaware Historical Society to Luke Beckerdite, May 3, 2016. The authors thank David Schorsch for informing them of his ownership of the bust and its subsequent sale to the Gardiners.

Sotheby’s, Important Americana, pp. 190–91, lot 1590. Linda Bantel, et al, William Rush, American Sculptor (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, 1982), pp. 177–78.

Pennsylvania Gazette, November 25, 1762.

For more on these objects and their attribution to Jugiez, see Luke Beckerdite and Alan Miller, “A Table’s Tale: Craft, Art, and Opportunity in Eighteenth-Century Philadelphia,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2004), pp. 32–39.

John Bivins Jr., “Isaac Zane and the Products of Marlboro Furnace,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 9, no. 1 (May 1985): 43–44. Bernard and Jugiez carved additional patterns for Zane. In March 1776, the ironmaster wrote Joseph Pemberton, “I should be glad to pay Bernard & Jugiez but I have not an exact account of the debt.”

South Carolina Gazette, October 12, 1765.

Philadelphia: Three Centuries of American Art (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1976), p. 23. Luke Beckerdite, “Philadelphia Carving Shops Part II: Bernard and Jugiez,” Antiques 128, no. 3 (September 1985): 512–13, nts. 23–25. The Philadelphia procession was described in the August 7, 1788 issue of the Georgia Gazette. Beckerdite, “Philadelphia Carving Shops,” pp. 512–13, nt. 26.

Sellers, Benjamin Franklin in Portraiture, pp. 119–213. NNDB.com.

Sotheby’s, Important Americana, New York, pp. 190–91, lot 1590.

Philadelphia: Three Centuries of American Art, p. 64. Beckerdite and Miller, “A Table’s Tale,” p. 3. Sellers, Benjamin Franklin in Portraiture, p. 203.

The samples were cast in mini-cubes of polyester resin (Excel Technologies, Inc., Enfield, CT). The resin was allowed to cure for 24 hours at room temperature and under ambient light. The cubes were then ground to expose the cross-sections, and dry polished with 400 and 600 grit wet-dry papers and Micro-Mesh polishing cloths, with grits from 1500 to 12,000. The samples were analyzed and photographed using a Nikon Eclipse 80i epifluorescence microscope equipped with an EXFO X-Cite 120 Fluorescence Illumination System fiberoptic halogen light source and a polarizing light base using SPOT Advanced software (v. 5.1) for digital image capture and Adobe Photoshop CS for digital image management. The samples were photographed in reflected visible and ultraviolet light using a UV-2A filter with 330-380 nm excitation, 400 nm dichroic mirror and a 420 nm barrier filter and a B-2A filter with 450–490 excitation and a 520 nm barrier filter.

Varnish layers were not separated out for analysis of organic components, but further analysis with FTIR microspectroscopy or gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MSA) might help identify the specific composition of each varnish coating.

Pigments from individual paint layers were dispersed and crushed onto microscope slides with a scalpel. These dispersed samples were permanently mounted under cover slips with Cargille MeltMount with a refractive index of 1.66. The samples were examined under plane polarized transmitted light and crossed polars (darkfield) at 400x and 1000x, and the unknown pigments were compared to standard pigment reference samples.

The following fluorescent and visible light stains were used for examination of the samples: fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) 0.2% acetone to identify the presence of proteins; triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (TTC) 4.0% in ethanol to identify the presence of carbohydrates (starches, gums, sugars); 2, 7 dichlorofluorescein (DCF) 0.2% in ethanol to identify the presence of saturated and unsaturated lipids (oils); rhodamine B (RHOB) 0.06% in ethanol to identify the presence of oils.