George A. Schastey and Company, Worsham-Rockefeller Dressing Room, New York City, 1881–1882. (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of The Museum of the City of New York, 2008. [2009.226.1–19a–f])

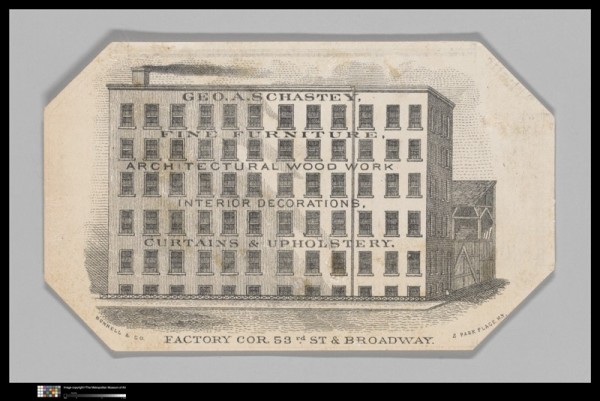

Trade card for George A. Schastey (reverse), New York City, 1876–1879. Paper and ink. 2 1/4" x 3 3/4". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art; gift of Paul Manganaro, 2016 [2016.631.2].)

Photograph of George A. Schastey and Company’s showroom, 1681–1683 Broadway, New York City, ca. 1885. (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art; gift of Paul Manganaro, 2016 [2016.631].)

Model B grand piano from the William Clark House, Newark, New Jersey, case by George A. Schastey and Company, instrument by Steinway and Sons, New York City, 1882. Satinwood and purpleheart; brass, silver. H. 40" (closed), W. 60", D. 84". (Collection of Paul Manganaro; photo, Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

George A. Schastey and Company, chair from the drawing room of the William Clark House, Newark, New Jersey, New York City, ca. 1882. Satinwood and purpleheart; brass. H. 40", W. 30", D. 36". (Collection of Marco Polo Stufano and the late John H. Nally; photo, Metropolitan Museum of Art.) The upholstery is modern.

Dressing table, attributed to George A. Schastey and Company, New York City, 1881–1882. Satinwood and purpleheart with white pine; marble, mother-of-pearl, silver-plated drawer pulls, brass, mirrored glass. H. 86 3/8", D. 36", W. 18 3/4". (Courtesy, High Museum of Art, Virginia Carrol Crawford Collection.) The velvet on the upholstered footrest is replaced.

Cabinet, attributed to George A. Schastey and Company, New York City, ca. 1880. Satinwood and purpleheart; brass, glass. H. 78 1/2", W. 92 1/4", D. 18 1/4". (Courtesy, Mission Inn; photo, Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

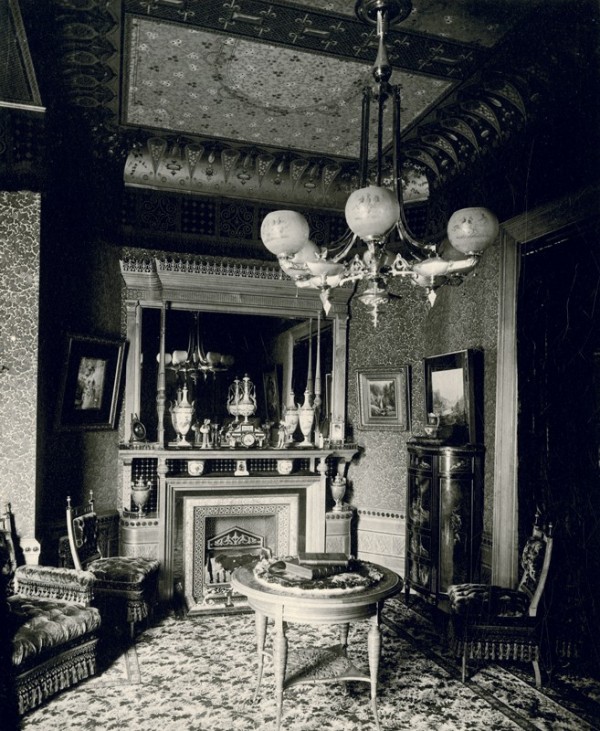

George A. Schastey and Company, drawing room of the Samuel Nickerson House, Chicago, Illinois, ca. 1880. (Courtesy, Richard Driehaus Museum; photo, Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Cabinet, attributed to George A. Schastey, New York City, ca. 1878. Satinwood and unidentified dark wood; brass, glass. H. 121", W. 75", D. 27". (Courtesy, Hotel del Coronado; photo, Metropolitan Museum of Art.) This cabinet originally furnished Linden Towers, the James C. Flood House, Menlo Park, California, now demolished.

George A. Schastey and Company, Worsham-Rockefeller Bedroom, New York City, 1881–1882. Ebonized cherry and lightwood marquetry; brass, glass. (Courtesy, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Gift of the Museum of the City of New York.)

George A. Schastey and Company, Worsham-Rockefeller Moorish Reception Room, New York City, 1881–1882. Ebonized cherry and gilded wood; polychrome pigment, brass, glass, textiles. (Courtesy, Brooklyn Museum, gift of John D. Rockefeller Jr.)

George A. Schastey and Company, cabinet from the drawing room of the Worsham-Rockefeller House, New York City, 1881–1882. Ebonized oak; brass, gilded bronze, agate. H. 60 1/2", W. 75 3/4", D. 13 1/4". (Courtesy, Seattle Art Museum, The Guendolen Carkeek Plestcheeff Endowment for the Decorative Arts, The Decorative Arts and Paintings Council and the Decorative Arts Acquisition Fund, in honor of the 75th Anniversary of the Seattle Art Museum.)

George A. Schastey and Company, side chair from the drawing room of the Worsham-Rockefeller House, New York City, 1881–1882. Ebonized oak; metal casters. H. 37 1/2", W. 23", D. 23 1/2". (Courtesy, Brooklyn Museum, gift of John D. Rockefeller III.) The upholstery is not original.

Tall case clock, case by George A. Schastey and Company, movement by Tiffany and Company, New York City, 1882. Ebonized oak; leaded glass, brass. Approx. H. 96", W. 18", D. 18". (Collection of Brian A. Emery; photo, Metropolitan Museum of Art.) This tall case clock has an oral history of being purchased from the William Clark House.

George A. Schastey and Company, worktable from the bedroom of the Worsham-Rockefeller House, New York City, 1881–1882. Purpleheart, satinwood, walnut, and mahogany with tulip poplar; brass, pewter or lead, mother-of-pearl, glass, colored resin, velvet. H. 30 3/4", W. 40 3/8", D. 24 1/4". (Courtesy, Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute, Museum of Art, Utica, New York, Museum Purchase by exchange with gifts from Jane B. Sayre Bryant and David E. Bryant in memory of the Sayre Family, and from the H. Randolph Lever Bequest.) The velvet on the exterior of the slide drawer is a reproduction.

Detail of the fallboard of the piano illustrated in fig. 4.

Cabinet, attributed to George A. Schastey and Company, New York City, 1884–1885. Rosewood, mahogany, and cherry with pine; pewter, brass, and mother-of-pearl inlay. H. 85 1/4", W. 42 3/4", D. 17 1/2". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Barrie and Deedee Wigmore, 2015. [2015.51a–h])

Detail of the fall front on the cabinet illustrated in fig. 17.

Detail of the jigsaw-cut music stand on the piano illustrated in fig. 4.

Detail of the footrest on the dressing table illustrated in fig. 6.

Photograph of a stair hall in one of the Andrew J. White residences, New York City, ca. 1886. (Historic Architecture and Landscape Image Collection, ca. 1865–1973, Ryerson & Burnham Archives: Archival Image Collection, Art Institute of Chicago, digital file #23766.)

Detail of a jigsaw-cut side panel on the cabinet illustrated in fig. 7.

Detail of the piano illustrated in fig. 4.

Detail of the cabinet illustrated in fig. 7.

Detail of a wardrobe drawer in the dressing room illustrated in fig. 1.

Detail of the door frame in the dressing room illustrated in fig. 1.

Samuel Gottscho, photograph of the Moorish reception room in the Worsham-Rockefeller House, New York City, ca. 1937. (Courtesy, Museum of the City of New York.)

Detail of a photograph by Samuel Gottscho of the entrance hall in the Worsham-Rockefeller House, New York City, ca. 1937. (Courtesy, Museum of the City of New York.)

Detail of the marquetry ornament in the dressing room illustrated in fig. 1.

Detail of a door on the cabinet illustrated in fig. 7.

Detail of one of the plaques flanking the jigsaw cut upright music stand on the piano illustrated in fig. 4.

Detail of a brass marquetry ornament on the cabinet illustrated in fig. 17.

Detail of a cabinet door in the dressing room illustrated in fig. 1.

Detail of the cabinet in the bedroom illustrated in fig. 10.

Detail of the carved ornament at the base of the tall clock illustrated in fig. 14.

Detail of the wardrobe in the dressing room illustrated in fig. 1.

Detail of the wainscoting, attributed to George A. Schastey and Company, in the dining room of the Samuel Nickerson House, Chicago, 1881–1882. Oak. (Courtesy, Richard H. Driehaus Museum.)

Detail of the cabinet illustrated in fig. 12.

George A. Schastey and Company, dressing glass from the Worsham-Rockefeller Dressing Room, New York City, 1881–1882. Satinwood, and purpleheart; mother-of-pearl, brass, glass. H. 23 1/4", W. 15 1/4", D. 10 1/2". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of the Museum of the City of New York, 2008. [2009.226.2])

Detail of the carved ornament on the piano illustrated in fig. 4.

George A. Schastey and Company, armchair from the drawing room of the Samuel Nickerson House, New York City, ca. 1880. Satinwood; brass. H. 42 5/8", W. 25 7/8", D. 23 3/4". (Collection of the Richard H. Driehaus Museum.) This chair may have been designed by W. August Fiedler (1842–1903). The upholstery is modern.

Detail of the chimneypiece from the entrance hall of the Worsham-Rockefeller house illustrated in fig. 48.

Detail of the chimneypiece from the drawing room of the Worsham-Rockefeller House, George A. Schastey and Company, New York City, 1881–1882. Mahogany; brass. (Private collection; photo, Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Detail of the pediment on the tall case clock illustrated in fig. 14.

Detail of a side chair from the Worsham-Rockefeller Dressing Room, George A. Schastey and Company, New York City, 1881–1882. Satinwood and purpleheart; brass. H. 36 7/8", W. 19 1/4", D. 23". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of the Museum of the City of New York, 2008. [2009.226.4]) The upholstery is a modern reproduction.

Detail of the chimneypiece from the dining room of the Worsham-Rockefeller House illustrated in fig. 59.

Detail of the cabinet from the entrance hall of the Worsham-Rockefeller House, George A. Schastey and Company, New York City, 1881–1882. Mahogany; brass, glass, marble. H. 155 1/2", W. 220 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

George A. Schastey and Company, chimneypiece from the entrance hall of the Worsham-Rockefeller House, New York City, 1881–1882. Mahogany and brass. (Private collection; photo, Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Detail of a spandrel from the entrance hall of the Homestead, Arabella and Collis P. Huntington’s country estate, Bronx, New York, George A. Schastey and Company, New York City, 1881–1882. Mahogany. (Courtesy, Preston High School; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the chimneypiece from the dining room of the Homestead, Arabella and Collis P. Huntington’s country estate, Bronx, New York, George A. Schastey and Company, New York City, 1881–1882. Oak; brass. (Courtesy, Preston High School; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a cabinet door in the dressing room illustrated in fig. 1.

Detail of the pier table from the entrance hall of the Homestead, Arabella and Collis P. Huntington’s country estate, Bronx, New York, George A. Schastey and Company, New York City, 1881–1882. Mahogany. (Courtesy, Preston High School; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the frieze of the wardrobe in the dressing room illustrated in fig. 1.

Detail of the fireplace mantel in the bedroom illustrated in fig. 10.

Wall clock, case by George A. Schastey and Company, movement by Tiffany and Company, New York City, 1881. Walnut with pine; brass, glass, silver-plated brass. H. 40", W. 25", D. 11 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Detail of a cabinet in the entrance hall of the William Clark House, Newark, New Jersey, George A. Schastey and Company, New York City, 1880–1882. Oak. (Courtesy, North Ward Center; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

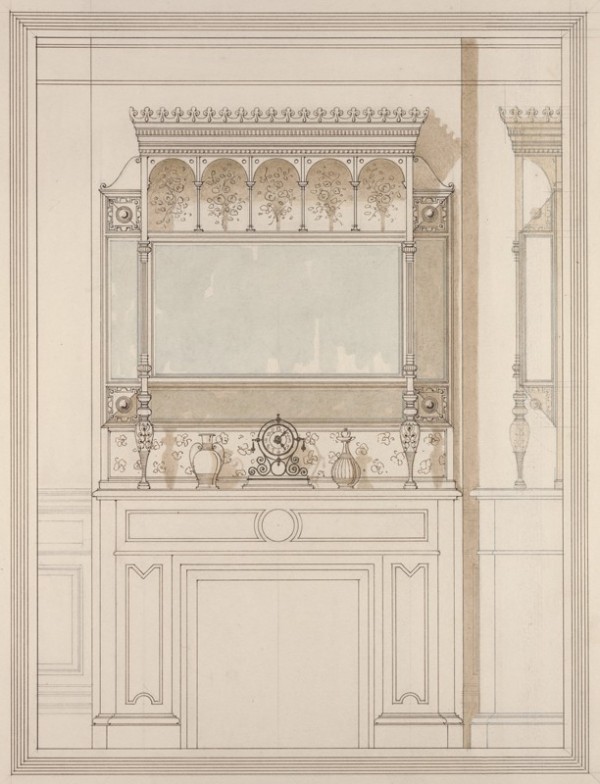

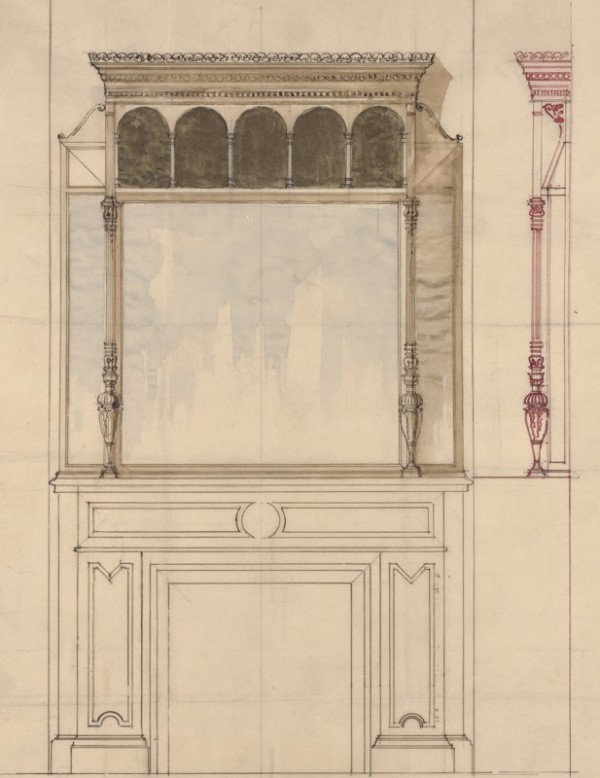

George A. Schastey and Company, design for an overmantel for the Edward C. Hegeler House, La Salle, Illinois, New York City, ca. 1880. Pen and ink, watercolor, and graphite on wove paper. 17" x 14". (Courtesy, Hegeler Carus Mansion, La Salle, Illinois; photo, Metropolitan Museum of Art.) The design may have been done by W. August Fiedler.

George A. Schastey and Company, design for an overmantel for the Edward C. Hegeler House, La Salle, Illinois, New York City, ca. 1880. Pen and ink, watercolor, metallic pigment, and graphite on tissue paper. 10 1/2" x 10". (Courtesy, Hegeler Carus Mansion, La Salle, Illinois; photo, Metropolitan Museum of Art.) The design may have been done by W. August Fiedler.

George A. Schastey and Company, chimneypiece from the dining room of the Worsham-Rockefeller House, New York City, 1881–1882. Oak; marble, glass. H. 160 1/4", W. 101". (Private collection; photo, Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Photograph of the boudoir of the Worsham-Rockefeller House, ca. 1883. (Courtesy, Hispanic Society of America.)

Side chair, one of a pair, attributed to George A. Schastey and Company, New York City, ca. 1882. Unidentified wood; white and gold painted decoration, brass. H. 35 /4", W. 20 3/4", D. 20 1/2". (Collection of A. Michelle Foote.) The upholstery is replaced.

Photograph of the dining room in the Samuel Nickerson House, Chicago, Illinois, ca. 1883. (Collection of the Richard H. Driehaus Museum.)

George A. Schastey and Company, staircase paneling in the entrance hall of the William Clark House, Newark, New Jersey, 1880–1882. Oak. (Courtesy, North Ward Center; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Samuel Gottscho, photograph of the ceiling of the dining room in the Worsham-Rockefeller House, New York City, ca. 1937. (Courtesy, Museum of the City of New York.)

Detail of the vanity in the dressing room illustrated in fig. 1.

Detail of the chimneypiece from the entrance hall of the Worsham-Rockefeller House illustrated in fig. 48.

Detail of the cabinet from the entrance hall of the Worsham-Rockefeller House, George A. Schastey and Company, New York City, 1881–1882. Mahogany; brass, glass. H. 106" W. 99", D. 14 5/8". (Private collection; photo, Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Detail of the hardware on the cabinet illustrated in fig. 12.

George A. Schastey and Company, center table from the Moorish reception room of the Worsham-Rockefeller House, New York City, 1881–1882. Ebonized cherry; brass, malachite, metal casters. H. 30 1/4", W. 34", D. 34". (Courtesy, Brooklyn Museum, Gift of John D. Rockefeller Jr.)

In the recent exhibition and publication Artistic Furniture of the Gilded Age, the Metropolitan Museum of Art debuted a substantial body of work by the late nineteenth-century cabinetmaking firm George A. Schastey and Company (1873–1897), which produced some of the Gilded Age’s most artistic and lavish furnishings for clients across the United States. The museum’s acquisition and installation of the Worsham-Rockefeller Dressing Room, a remarkable 1881–1882 interior in the aesthetic style that survives from Schastey’s best-documented commission for Arabella Worsham, later Huntington (ca. 1850–1924), prompted the exhibition and extensive investigation into Schastey’s little-known career and work (fig. 1). The exhibition built on the American Wing’s long-standing commitment to fine and decorative art of the late nineteenth century, a period of unprecedented patronage, innovation, and creativity. Drawing on the exhaustive research carried out for the exhibition, this article examines the surviving body of work now attributed to Schastey’s luxury cabinetmaking and decorating house and highlights the ornamental and technical characteristics that define this firm’s distinctive work in the aesthetic style.[1]

The work of George A. Schastey and Company stands out as an exceptional example of the originality and quality that flourished in the New York City cabinetmaking trade during the last quarter of the nineteenth century. While many features discussed below align with those used throughout the luxury cabinetmaking and decorating trade during this period, a selection of features is specific to Schastey. The firm’s preference for certain materials, such as satinwood with contrasting dark wood marquetry; its frequent use of certain decorative techniques, including metal marquetry and jigsaw-cut fretwork; and its nuanced interpretation of broadly used ornamental motifs like Renaissance-inspired putti, set Schastey and Company apart from other high-end cabinetmaking shops. Due to the absence of any signed or systematically marked objects, the work of George A. Schastey and Company has frequently been misidentified as that of its better-known competitors, such as Herter Brothers and Pottier and Stymus Manufacturing Company; however, the identifiable characteristics discussed in this article will allow scholars to make informed attributions to Schastey and Company in the absence of documentation, signatures, or stamps.

George A. Schastey

George A. Schastey (1839–1894), the proprietor of the firm, was born in Merseburg, Germany, and immigrated to the United States with his family in 1849. Although documentation of his early life is scant, obituaries and business reports suggest that he learned the upholsterer’s trade working at the firms Rochefort and Skarren and Marcotte and Company, before taking on leading positions at Pottier and Stymus, Herter Brothers, and Conrad Boller. Schastey opened his eponymous New York City cabinetmaking enterprise in 1873, and the firm offered a complete range of services that included furniture, architectural woodwork, various decorations, and upholstery. The company’s earliest commissions came from the railroad titans of California, who built palatial mansions in San Francisco following the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869. Early on, Schastey’s firm served as a subcontractor to its larger competitors but soon became the lead decorator on large commissions, including the San Francisco residence of Charles Crocker, a founding partner of the Central Pacific Railroad. A grand showing of the firm’s work for Crocker, at the 1876 Centennial International Exhibition held in Philadelphia, cemented its status as one of the nation’s leading cabinetmaking and decorating concerns.[2]

Despite working exclusively on commission and offering no ready-made stock, the business continued to grow and Schastey expanded the manufacturing operation to a substantial factory at West Fifty-Third Street and Broadway (fig. 2) with a showroom in the heart of New York City’s fashionable shopping district at Union Square. As money flowed into the city, its most affluent citizens sought to express their newfound identities as masters of industry and finance through domestic architecture, outfitted with fine art and custom furnishings. This boom created a prime market for the luxury cabinetwork and decorating services offered by Schastey and his competitors, and the 1880s proved to be the firm’s most productive and creative period. The company undertook a number of large-scale commissions, including the complete interior decoration of at least three substantial residences between 1880 and 1882—those of banker Samuel Nickerson of Chicago (ca. 1880); thread manufacturer William Clark of Newark, New Jersey (1880–1882); and the self-made Arabella Worsham, later Huntington, of New York City (1881–1882).[3]

In 1885 the firm, now known as George A. Schastey and Company, added an enlarged showroom to its factory (fig. 3), an addition that followed the northward migration of New York City society uptown, away from the overcrowding of lower Manhattan. Many of Schastey’s clients remained loyal to his firm and continued to call on him for all of their decorating needs. Such loyalty is best exemplified by Arabella Worsham, who later, with her husband, Central Pacific Railroad industrialist Collis P. Huntington, hired Schastey to decorate three additional New York dwellings, with the most extensive work done on their country estate, the Homestead (1885), located at Throggs Neck in the Bronx. In addition to these large-scale commissions, the firm carried out a number of smaller renovations, produced individual pieces of furniture, and supplied window curtains along with other upholstery goods for a variety of clients, including zinc manufacturer and publisher Edward C. Hegeler of La Salle, Illinois (ca. 1880), and oil magnate John D. Rockefeller of New York City (1884–1893).[4]

Although continually plagued by a shortage of liquidity, Schastey’s operation persevered through multiple economic depressions. In 1890 he saw potential in the emerging middle-class market and opened an additional cabinetmaking operation in Springfield, Massachusetts, then a booming industrial town. This new enterprise, named George A. Schastey Company, accepted commissions and offered a selection of more moderately priced, ready-made furniture in the colonial revival and arts and crafts styles, as well as furnishings for museums. Although both branches of Schastey’s firm continued after his death in 1894, neither was able to sustain long-term success; the New York branch closed in 1897, and the Springfield manufactory folded in 1907.[5]

Shop Style

George A. Schastey and Company’s work was largely influenced by the aesthetic movement, a design revolution that combined historic revival forms and ornament with the conventionalized style of the contemporary British design reform movement and the decorative vocabulary and aesthetic sensibilities of the arts of China, Japan, and the Islamic world. The firm also continued to favor the highly sculptural Renaissance-revival style, and motifs such as putti, term figures, lush flora, lions, and grotesques featured prominently in the company’s decorative vocabulary. While the work of other high-end firms, such as Herter Brothers and Pottier and Stymus, reflected a similar aesthetic, each company combined these styles and influences in an idiosyncratic way. Many of the craftsmen employed by these cabinetmaking and decorating firms were highly skilled immigrants from France and Germany. Over the course of their careers, these men often worked in multiple shops, transferring designs and techniques from place to place. At Schastey’s workshop, supervisors ensured that production was consistent with their employer’s aesthetic vision. The employees’ individual proclivities combined with Schastey’s vision to create a nuanced and distinctive interpretation of prevailing styles.[6]

Materials and Technique

Firmly documented to George A. Schastey and Company, the Worsham-Rockefeller Dressing Room is a cornerstone for attributions to that firm (fig. 1). The architectural woodwork, built-in elements, and furnishings are made of satinwood and ornamented with purpleheart, also called amaranth. This combination creates a striking effect, as the rich hue of the purpleheart contrasts with the light yellow tone of the satinwood, all accented by glimmering mother-of-pearl. As research into the dressing room progressed, a remarkable Steinway and Sons piano made by George A. Schastey and Company in 1882 for William A. Clark of Newark, New Jersey, came to light (fig. 4). As in the dressing room, Schastey employed satinwood as the principal material in the piano’s case and purpleheart for its carved and marquetry ornament. Instead of mother-of-pearl, brass appears throughout the case to provide an eye-catching effect. Shortly after its completion, the Clark mansion was featured in the celebrated publication Artistic Houses. The book included photographs and a flowery description of the mansion’s interiors; although Schastey and Company’s contributions to the decoration went unmentioned. The published photography of Clark’s drawing room that shows the piano in situ, along with surviving architectural woodwork and a pair of satinwood and purpleheart chairs from that room, confirms that the instrument was made en suite with the room and its other furnishings (fig. 5). While these two imported woods were available to other cabinetmakers during this period, Schastey’s firm appears to have used this combination of materials with greater frequency than any of his competitors.[7]

The use of satinwood with purpleheart enriched with brass or mother-of-pearl was one of the first attributes to emerge as an indicator of Schastey and Company’s work. In 1983 decorative arts scholar David Hanks attributed the dressing table illustrated in figure 6 to Schastey’s firm based on those materials and the object’s stylistic relationship to the Worsham-Rockefeller Dressing Room. Although lacking any documented history, another cabinet is now attributed to Schastey based on its use of satinwood with purpleheart and brass marquetry, jigsaw-cut side panels, and square feet (fig. 7). The interiors of the Samuel Nickerson House in Chicago offered scholars of Schastey’s work another example of the firm’s preference for satinwood, but paired with an unidentified dark wood (fig. 8). A cabinet, part of a suite of furniture to survive from the James C. Flood mansion, Linden Towers, in Menlo Park, California, presents a similar combination of satinwood with marquetry decoration in a dark-hued wood that may be purpleheart (fig. 9). Although Pottier and Stymus are cited as the primary outfitters of Flood’s residence, Schastey claimed a hand in its execution and the cabinet is now attributed to his firm. These objects and interiors illustrate Schastey’s extensive use of ornamented satinwood and purpleheart across various commissions throughout his career.[8]

Schastey’s shop also produced work in a number of other imported woods, including rosewood and mahogany, as well as domestic woods such as cherry and oak. These varieties were ubiquitous in cabinetmaking during the late nineteenth century; however, Schastey’s unconventional use of oak with an ebonized finish is a distinguishing feature of his shop’s work. During this period, furniture treated to look like ebony was highly desired because it imitated the exotic material and had a similar appearance to Japanese lacquer, an imported and expensive material prized for its laborious creation, simplified aesthetic, and associations with the exoticism of Japan. Most surviving examples of ebonized furniture from this period are made of cherry and are often decorated with lightwood marquetry, typically in a minimalistic, floral design to further evoke the arts of Asia. Schastey’s suite of ebonized cherry furniture for Arabella Worsham’s bedroom (fig. 10) and reception room (fig. 11) reflect this more traditional approach to the production of Japanesque furnishings. Schastey diverged from this tradition by adding an ebonized finish to robustly carved oak furniture. A surviving cabinet from Worsham’s drawing room executed in this manner shows how Schastey abandoned any stylistic association with the Japanesque by using a sixteenth- or seventeenth-century European court cupboard form and a Western ornamental vocabulary of classical moldings, floral swags, and putti (fig. 12). A side chair from the same room (fig. 13), one of two known, and a tall clock by Schastey and possibly from the Clark commission (fig. 14) display this same treatment. Oak furniture in a Renaissance-revival style with an ebonized finish is not commonly seen in the work of Schastey’s competitors.[9]

Another element found throughout Schastey and Company’s work is complex marquetry executed in a variety of metals and mother-of-pearl. Marquetry in those materials reached the height of its popularity in America during the 1880s and can be found in the products of numerous high-end cabinetmaking shops, including Herter Brothers, Pottier and Stymus, and Herts Brothers. Schastey’s firm was well known for its use of geometric-patterned marquetry. In November 1883 the Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide noted, “[o]rnamentation by means of marqueterie has become very popular, some choice pieces, inlaid in geometrical designs with mother of pearl and brass, were shown by Geo. Schastey and Company, of No. 9 East Nineteenth street, this style of decoration is quite new and very successful in its results.”[10]

A virtuosic rosewood worktable, recently documented to the Worsham commission, best demonstrates the firm’s mastery of complex geometric metal marquetry (fig. 15). Schastey’s craftsmen arranged small pieces of fan-shaped pewter and brass in a rhythmic, alternating pattern over the majority of the surface. Red resin fills the small gaps in the pattern, while brass stringing and spindles, along with small patterns in mother-of-pearl, further ornament the form. Similar fan-shaped brass pieces appear on the marquetry of the fallboard of the Clark piano (fig. 16). On the piano, the brass is surrounded by purpleheart and accented with incised lines, which together create the stylized trompe l’oeil effect of a textile draped over the keyboard.[11]

An elaborately ornamented cabinet displays related diaper-patterned brass marquetry along the front and side surfaces of the cabinet’s drawer (fig. 17). This piece was described in a review of Schastey’s new showrooms at Broadway and West Fifty-Third Street published in the August 18, 1885, issue of the New York Times:

To return to the cabinet work, nothing finer is imported than the inlays that are made here. While in workmanship and design they rival foreign work, they also have the very positive advantage of being adapted to our climate, which the foreign work, as we know from its yawning cracks under our extremes of heat and cold, has not. One of these is a bedstead of black oak, with slender rayed forms inlaid in brass. The most striking piece, however, is a large cabinet of amaranth inlaid with mother of pearl and silver. . . . The central panel is an elaborate design in the silver. Surrounding it the plainer surfaces are interspersed with stars of mother of pearl. Below a carved band is a fine inlay of brass, making another band, and below again come the richer forms in pearl and silver. Work of the same kind is seen in small round tables, each a work of art.[12]

The firm’s designers drew their inspiration from Islamic sources for the mother-of-pearl cypress tree, surrounded by blooming lotus flowers and vines in pewter on the central door of the upper case and for the intricate web of interlaced arabesques, also in pewter, on the fall front of the lower case (fig. 18). The firm’s extensive use of pewter in marquetry and the complexity of the designs on this cabinet and the worktable offer additional characteristics with which Schastey and Company’s work can be identified.

The arabesque design on the cabinet’s fallboard relates to the jigsaw-cut fretwork on the music stand on the Steinway and Sons piano (fig. 19). To execute this complex sawn ornament, Schastey’s craftsmen laminated multiple pieces of wood together to create a piece strong enough to withstand the sawing process and maintain a crisp edge. The fretwork’s pierced maze of intersecting lines and bold curves derives from Islamic architectural screens and calligraphic designs, which were widely published in the late nineteenth century. The dressing table illustrated in figure 6 has similar jigsaw-cut panels on each side of the central footrest in an asymmetrical design of inverted lyres and scrolls (fig. 20). In both fretwork designs, small circles create an intricate play of positive and negative space. A photograph of the entrance hall in a New York City town house, one of two neighboring dwellings decorated by Schastey in the spring of 1886, shows an intricate screen composed of small and large pierced panels (fig. 21), which were likely laminated and sawn like those on the music stand and dressing table. This same approach was used to execute the side panels on the cabinet illustrated in figure 7, but instead of interlacing arabesques, the pattern is a systematic arrangement of geometric shapes (fig. 22).[13]

Designs and Ornamental Motifs

In interpreting the aesthetic style, Schastey’s designers blended the sculptural styles of the Renaissance and baroque periods with the more flattened and geometric styles of Asia and the Islamic world, using both marquetry and carved ornament to create an original decorative vocabulary. Similar ornamental motifs were often executed in different materials to add further variety, as with the aforementioned arabesque design in metal marquetry and jigsaw-cut fretwork. This translation of designs across media is also evident in the strapwork-like rectangular plaques that appear throughout Schastey’s work. On the Clark drawing room suite, including the piano (figs. 5, 23), and on the cabinet discussed above (fig. 24), the small brass rectangles rhythmically punctuate the bands of floral marquetry. In the Worsham-Rockefeller Dressing Room, Schastey substituted mother-of-pearl to create the same plaques, imitative of Renaissance designs, along the door and window frames, entablatures, drawer fronts, and doors (figs. 25, 26). The motif appears in painted decoration just above the overmantle in Worsham’s Moorish reception room (fig. 27), and although the Worsham-Rockefeller House does not survive, similar strapwork plaques appeared in the carved mahogany details of the wainscoting in its entrance hall and main stairwell (fig. 28).

Another distinctive motif that occurs throughout Schastey’s oeuvre in a variety of materials is a series of small hatched lines. In the Worsham-Rockefeller Dressing Room, these lines appear in the marquetry ornament of various scrolling motifs (fig. 29). Schastey derived this motif from sixteenth-century Renaissance carved ornament, where hatched lines often appear incised within volutes or scrolls. By reinterpreting these hatched lines into the stylized perspective of aesthetic marquetry, Schastey added dimension and texture to visually and physically flat surfaces. The doors of the cabinet illustrated in figure 7 exhibit this same effect, and each hatched line tapers with the narrowing of the scroll (fig. 30). On the drawer fronts of the wardrobe in the Worsham-Rockefeller Dressing Room, Schastey reversed the color palette, adding lines of purpleheart to the satinwood ground of the scrolling volutes (fig. 25). An identical treatment appears on the two decorative panels of the music stand on the Steinway and Sons piano (fig. 31). Almost like ram’s horns, the two hatched scrolls flank the pewter satyr’s face, surrounded by a field of stylized flora. The number of hatched lines that fills each scroll varies, reflecting the handcraftsmanship of this precisely executed ornament. On the cabinet that likely stood in Schastey’s newly renovated showrooms, small inverted lyre shapes with hatching executed in brass enliven the spandrels of the lower case (fig. 32).

Schastey also used these hatched lines on carved ornament, more in keeping with their original Renaissance sources. Often a minute detail, the incised lines consistently appear in the small volutes integrated throughout Schastey’s work (fig. 33). Even in their carved interpretations, the hatched lines reflect the conventionalized style drawn from the British design reform movement. Shallow incised lines also appear as a framing element along the edge of many of Schastey’s forms, such as the C-curve of the canopy and the built-in cabinets of the Worsham-Rockefeller Bedroom (fig. 34) and on the cabinet illustrated in figures 7 and 24. The Clark piano exhibits similar hatching as a framing mechanism around the carved purpleheart vignettes on each leg (fig. 40).

Perhaps the most intriguing use of this motif are the hatched lines on the ebonized tall clock (fig. 35). Shallow lines decorate the interlacing strapwork pattern at the base. Surrounding the jewel-like bosses, this design anticipates the whiplash lines of the impending art nouveau style. The design of the glass panel at the waist shows the mark of Schastey’s designers, as the gilded lead is arranged as hatched lines along the border and down the center of the composition (fig. 14).[14]

For most luxury cabinetmakers, the Renaissance revival served as their primary decorative theme throughout the 1860s and 1870s, and by the 1880s, their work drew heavily on the Eastern influences of the aesthetic style. For Schastey, the Renaissance revival remained the principal style of his shop throughout the 1880s, as his designers continued to rely on richly carved putti, lions, floral swags, ribbons, and interpretations of the grotesque. One of Schastey’s most recognizable carved motifs derived from this Renaissance idiom are the plump putti heads that appear throughout his shop’s work. Schastey and Company’s frequent use, placement, and particular handling of putti heads—a common motif in the Renaissance-revival style—are distinctive to the firm. In the Worsham-Rockefeller Dressing Room, these angelic putti with swollen cheeks, puckered lips, and enlarged foreheads are carved and applied as embellishment to the built-in wardrobe, brackets, and cabinet doors of the wardrobe (fig. 36). Similar, yet slightly more mature faces and less exaggerated facial features appear on the lower cabinet doors of Worsham’s dressing mirror (fig. 33), on the cabinet illustrated in figures 7 and 24, and the ebonized oak tall clock (fig. 14). Putti also appear in great number in the oak dining room of the Nickerson mansion, where they line the room’s wainscoting (fig. 37) and on the cabinet from Worsham’s drawing room (figs. 12, 38). A three-dimensional application of that motif can be seen in the finials of the delicate tabletop dressing mirror from the Worsham-Rockefeller Dressing Room (fig. 39) and on the Clark mansion’s drawing room seating furniture (fig. 5).[15]

Classically inspired terms are another carved motif that are prominent in Schastey and Company’s work. As the legs of the Clark piano reveal, his figures are typically buxom female torsos with foliate details below (fig. 40). The applied figures emerge from acanthus leaves, draped with a cascading garland of flowers and surrounded by blooming cornucopias. Crowned with a small diadem, each figure’s hair falls to the sides and has the same undulating quality seen in the carved ribbons often found on Schastey and Company’s pieces.

A set of four armchairs from the Nickerson drawing room feature similar female busts that form part of the winged sphinx arm supports (fig. 41). These sphinxes relate to those on the piano in their overall form, with a revealed chest, jewelry, and parted hair with diadem. However, their pupil-less eyes are opened, their noses are slightly more angular, and their lips are more puckered. For Arabella Worsham, a self-made, then-unmarried woman, Schastey used similar carved classical figures prominently in her entrance hall and drawing room. Two large term figures flank the bronze relief sculpture of Diana on the chimneypiece from the entrance hall (fig. 42). A double-strand necklace supports their classical garb and the falling array of vegetation, and other accessories include a pair of large pendant earrings and armband. Although anchored within the column, the upheld arms, folding garments, and sprawling hair of the figures add liveliness to the composition. The surviving chimneypiece from Worsham’s drawing room has similarly exposed, yet significantly smaller figures at the side of the fireplace (fig. 43). The execution of their hair, physical form, and foliage recall the figures of the Clark piano, and each holds a garland of jingle bells, likely a self-conscious reference to Worsham, who was always called “Belle.” The faces on the drawing room chimneypiece have less angular noses, plumper lips, and swollen heads—more in line with the firm’s interpretation of the putti seen in the dressing room. The differing scale and placement of these figures, along with the various carvers in Schastey’s workshop, likely account for the slight differences in each iteration, yet this body of work reflects a consistent shop style. While other firms also drew on this Renaissance motif, Schastey’s frequent use of these highly sculptural, female-foliate terms into the 1880s sets his work apart from that of his competitors, who largely depended on such motifs in earlier decades.

Beyond human figures, Schastey and Company’s Renaissance-inspired ornamental vocabulary includes a number of grotesques and animal forms. One of the most finely rendered examples is the satyr’s face that surmounts the ebonized oak tall case clock, surrounded by a scallop shell (fig. 44). Interspersed through the marquetry in Worsham’s dressing room are a number of small grotesque masks (figs. 29, 45). Created by lines finely incised into the purpleheart and highlighted by a light colored putty infill, these faces can be discerned in the leafy motifs employed throughout the woodwork. Two staunch griffins flank the fireplace on the oak chimneypiece from the dining room of the Worsham-Rockefeller House (fig. 46). Like the satyr on the tall clock, a naturalistic cluster of vegetation hangs from each creature’s mouth. On a surviving cabinet from the entrance hall of Worsham’s Fifty-Fourth Street town house, griffins or sea lions sit at attention on each side of the mirror (fig. 47). Their firm stance recalls the pose of the griffins on the dining room chimneypiece, while their wings and scrolling, scaly fish tails add a mythical flair to their composition.

Lions constitute one of the most common animal motifs in Schastey’s work and appear with particular frequency in commissions connected to Worsham. On Worsham’s entrance hall chimneypiece, three lion’s heads, with their manes and furrowed brows masterfully articulated, rest above the fireplace and clutch a brass bail in their mouths (fig. 48). An almost identical interpretation of the lion appears in Worsham’s bedroom, along the sloping brackets of her bed canopy and other built-in cabinets (fig. 34). Meanwhile, in the woodwork of her dressing room the lion and the lioness are subtly hidden in the purpleheart foliage. At her country estate, the Homestead, a roaring lion composed of hatched scrolls and leaves graces the spandrel of the entrance hall archway (fig. 49). Its less rigid handling is mimicked in the florid dragons that frame the upper portion of the fireplace in the dining room of the same house (fig. 50).[16]

Two other Renaissance-inspired motifs found in Schastey’s work are the ribbon and floral swag. Frequently paired together, these two items appear as both carved ornament and in marquetry. In the Worsham-Rockefeller Dressing Room, carved ribbons adorn the door panels and cornices, and ribbons in marquetry appear on the architectural woodwork. Ribbons weave through the strands of jewelry and vines on the wardrobe cabinet doors, unifying the composition and taking on a remarkable three-dimensional quality through their textural lines and projecting folds (fig. 51). The ribbon’s undulating tail splits into two at its end and terminates with a small bead. This style of ribbon appears throughout Schastey’s oeuvre, as seen on the built-in pier table in the entrance hall of the Huntingtons’ summer residence (fig. 52).

Throughout Worsham’s dressing room, ribbons are paired with a floral swag, bound at the center with an X-crossed bow (fig. 53). The swag is composed of small, stylized, four-petal blossoms, distributed in an even pattern. Identical swags and ribbons in a larger scale appear on the mantel in the Worsham-Rockefeller Bedroom (fig. 54). Alternatively, naturalistic floral swags adorn various works, such as those draped across an unusually proportioned wall clock by Schastey (fig. 55) and repeated around the case of the Clark piano (fig. 23). Swags of oak leaves also appear throughout Schastey’s work, perhaps a symbolic statement of strength and fortitude on behalf of his nouveaux riche clients. These oak-leaf swags appear along the frieze of a surviving built-in cabinet from Clark’s entrance hall (fig. 56), across the crest rail of Nickerson’s satinwood drawing room chairs (fig. 41), and on the crest rail of Worsham’s ebonized oak drawing room chairs (fig. 13). The ribbons that accompany the oak-leaf swags on the crest rails are formed through more dramatic swelling and tapering that mimic the quality of the carved hair on the term figures. The incised texture is more regular and conventionalized, again demonstrating the strong influence of British design reform on Schastey’s shop style.[17]

The ability of Schastey’s designers to creatively rework these Renaissance and classically inspired decorative elements in a range of media and integrate them into a variety of architectural woodwork and furniture forms stemmed from the need to create original works for each commission. The unnamed author of the New York Times review of Schastey’s showrooms praised the variety of the firm’s output and stated, “Such work is never duplicated, so that each interior undertaken has the value of uniqueness.” Schastey’s commission-based business model ensured that each client’s order was customized to individual wishes and needs, and to date, no two identical pieces from separate commissions have been located. Schastey’s manufactory likely housed an extensive library of pattern books, reference materials, and previously executed designs to assist the designers in creating new material. Although Schastey’s designers repeated various discrete elements of their decorative vocabulary, the firm’s surviving body of work attests to its ability to refashion these motifs into something altogether new for each client.[18]

Before any work commenced, Schastey’s designers created a series of proposals, which were submitted to the client for approval. From their numerous commissions, only ten drawings, presented to Edward C. Hegeler of La Salle, Illinois, as an update to his existing interior decorations, are known to survive. Two proposals for a chimneypiece demonstrate how Schastey and Company reinterpreted designs across commissions (figs. 57, 58). Each depicts an existing fireplace below a newly designed overmantel mirror with a decorated cove-molded frieze and trefoil-lined cornice. Although it seems neither design was executed for Hegeler, elements from each were incorporated into chimneypieces executed for Schastey’s long-standing client Arabella Worsham. For Worsham’s dining room chimneypiece, Schastey and Company used carved bosses with strapwork—details found in the designs submitted to Hegeler—to punctuate each corner of the overmantel mirror (fig. 59). Similarly, the chimneypieces in Worsham’s boudoir, a more intimate second-floor sitting room (fig. 60), and the Moorish reception room (figs. 11, 27) both featured the pierced crenellated cornice with trefoils. Another cornice of small trefoils and circles paired with carved jewels and necklaces tops the three built-in elements in the Worsham-Rockefeller Dressing Room (fig. 1). At each corner, the finial sweeps upward slightly to create a pagoda-like profile, demonstrating the influence of Asian designs. A related cornice design also appears on a walnut wall clock case that Schastey’s firm made to house a Tiffany and Company movement (fig. 55).[19]

This reuse of designs with slight variations is also seen in Schastey and Company’s seating furniture. Three chairs from different commissions, made of different woods and treated with different finishes, all share a related crest rail design. On the Nickerson armchairs, two oak-leaf swags with ribbons follow the undulation of the crest rail and the ears scroll outward in a pronounced fashion (fig. 41). The crest rail of the ebonized oak side chair from Worsham’s drawing room features a single carved swag of oak leaves with a string of beads and large scrolling ears that scroll inward (fig. 13). The consistency of this crest rail design allows for the attribution of a side chair with a white-and-gold painted surface to Schastey’s firm (fig. 61). Here, the scrolling ears of the crest rail take on the form of a ram’s head, adding an extra flourish to the design. Unlike Worsham’s drawing room chair, which included carved decoration below the upholstered back, this side chair presents evidence that a decorative ribbon or cord was once laced between the rear seat rail and upholstered back.[20]

Another design feature found in Schastey’s seating furniture is a stylized paw foot that is square in section. As the Nickerson armchairs reveal, the foot is not in an active grasp and often rests on a carved pad to which a caster is attached (fig. 41). A related version of this foot appears on Worsham’s drawing room chairs (fig. 13), the white-and-gold side chair illustrated in figure 61, and the worktable executed for Worsham’s bedroom (fig. 15). On the worktable, the highly articulated paws sit on a carved round disk. A variation of this design also appears on the feet of the cabinet illustrated in figure 7, where the knuckles of the claw blend into curling leaves.

This original foot design captures George A. Schastey and Company’s almost whimsical design aesthetic, one derived not only from its eclectic ornamental vocabulary but also from its tendency to exaggerate the scale and proportion of certain motifs. Elements like the paw foot appear in monstrous scale on the dining room table from the Nickerson residence (fig. 62). A comparable degree of exaggeration can be seen in the woodwork in the Clark mansion, where an unusually large-scale basket-weave motif is used as the wall paneling along the underside of the U-shaped grand staircase in the entrance hall (fig. 63). The strips of wood are arranged to suggest Japanese latticework. Although this motif appears in a variety of furniture and woodwork from the period, including the contemporaneous stair hall from the Metcalfe House in Buffalo, New York, designed by McKim, Mead, and White, its enlarged scale in the Clark residence distinguishes it as Schastey’s work.[21]

Repetition of forms constitutes another example of Schastey’s penchant for exaggeration. His designers often repeated a particular ornamental element on the same piece to increase its impact. One such detail is the profusion of architectural brackets, like those on the ceiling of Worsham’s dining room, captured in a photograph taken just before the house was demolished in 1937 (fig. 64). A series of small S-shaped brackets lines the ceiling beams as a decorative flourish. As evident on Worsham’s dressing room vanity, the number of brackets greatly exceeds what is necessary to support the wooden and marble shelves and are, instead, used for decorative effect (fig. 65) The surviving chimneypiece from the entrance hall of 4 West Fifty-Fourth Street also uses multiple brackets just above the central metal relief of Diana, appearing to support the recessed space but not actually doing so (fig. 66). Similarly, a cabinet also from the entrance hall of the same house demonstrates this same excess under the carved panel above the mirror (fig. 67).

Hardware

Schastey and Company also used distinctive forms of cabinet hardware, which offer another avenue for identifying the firm’s work. While many cabinetmakers purchased stock hardware, some luxury cabinetmaking shops ordered or made custom-designed hardware. It is unclear if Schastey had the ability to produce his own hardware, but a series of notable forms suggests that the firm did at least design customized decorative pulls. In the Worsham-Rockefeller Dressing Room, the drawers of the wardrobe feature two large, silvered-brass bail pulls (fig. 25). The reeded bail swells as it approaches the center and is capped with two studded rings. The backplate of the hardware is a pierced design of interlaced arabesques with hatched lines on the solid portions. The relation of this design to Schastey’s recurring use of artistic arabesques and hatched lines mentioned above suggests that this hardware was designed, if not executed, by the firm. Identical hardware appears in brass on the drawers in the Worsham-Rockefeller Bedroom. On smaller drawers, Schastey used a modified version of this design without the elaborate backplate (fig. 33), as seen on the High Museum’s dressing table (fig. 6) and the worktable with ornate marquetry now documented to be from Worsham’s bedroom (fig. 15).[22]

This nearly identical bail shape is used on the two large brass mounts on the fall front of the ebonized oak cabinet from Worsham’s drawing room (fig. 68). Here the backplate is a design of stylized cypress trees that serve as the rays of an eight-pointed star, with brown and white agate bosses situated between each tree. The screws at each point that hold these heavy mounts to the cabinet are visible and integrated into the design. Surrounding each agate boss is a beaded scroll design on a stippled background. Similar small bosses of malachite ornament the skirt of a surviving center table from the Worsham-Rockefeller Moorish Reception Room (fig. 69). The application of these colorful stones creates a striking overall impression, and their use is not common on furniture from this period.

Conclusion

Much remains to be learned about George A. Schastey and Company. While a number of commissions are now documented to Schastey’s firm, many of his clients are still a mystery owing to the absence of company records. Questions as to the division of labor within the firm and the scope of the manufactory linger, and many of the firm’s employees have yet to be identified. Because no signed or marked works survive, attributing interiors and furniture to the workshop continues to be a challenge; however, the materials employed, such as the firm’s well-documented use of satinwood with purpleheart, metal marquetry, and distinctive jigsaw-cut panels, provide initial clues for identifying the firm’s work. Closer analysis of the designs and ornamental motifs used by the firm, including square paw feet, hatched lines, ribbons, swags, putti, and other carved figures, reveals that its approach to these elements differs from the work of its closest competitors. When viewed in conjunction with other attributed characteristics, these materials, techniques, and decorative motifs serve as useful vehicles for identifying the work of this impressive Gilded Age firm. As more work comes to light, along with further documentation about the workshop, Schastey’s legacy as one of the late nineteenth century’s leading cabinetmakers will continue to grow.[23]

Beginning with the landmark exhibition and publication 19th-Century America (1970), the Metropolitan Museum of Art has been a leader in studying late nineteenth-century decorative arts. Later exhibitions and publications including In Pursuit of Beauty (1987) and Herter Brothers: Furniture and Interiors for a Gilded Age (1994–95) built on this tradition. Berry B. Tracy, Marilynn Johnson, et al., 19th-Century America: Furniture and Other Decorative Arts (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1970); Doreen Bolger Burke et al., In Pursuit of Beauty: Americans and the Aesthetic Movement (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1986); Katherine Howe et al., Herter Brothers: Furniture and Interiors for a Gilded Age (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1994). The three-part exhibition “Artistic Furniture of the Gilded Age” (Metropolitan Museum of Art, December 15, 2015–June 5, 2016), which included the debut of the Worsham-Rockefeller Dressing Room, a focused exhibition on George A. Schastey, and an installation of material by Herter Brothers for William H. Vanderbilt, continued this legacy. The exhibition was co-curated by Alice C. Frelinghuysen and Nicholas C. Vincent, and the author is deeply indebted to these scholars for their guidance and support in writing this article. Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen et al., “Artistic Furniture of the Gilded Age,” Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 73 (Winter 2016). In 1881–1882 Arabella Worsham, the mistress of railroad magnate Collis P. Huntington (1821–1900), commissioned George A. Schastey and Company to decorate her newly renovated town house at 4 West Fifty-Fourth Street in New York City. Shortly after the work was completed, Worsham married Huntington and sold the house to John D. Rockefeller (1839–1937). After Rockefeller purchased the house, George A. Schastey wrote to him, offered his firm’s services, and noted: “We desire to state that the interior woodwork and decoration of your new residence (#4 W. 54th St.) was designed and executed by us.” (George A. Schastey & Co. to John D. Rockefeller Esq., October 29, 1884, The Papers of John D. Rockefeller Sr., Part 3: Office Correspondence, 1879–1894, reel 33, Rockefeller Archive Center). Following Rockefeller’s death in 1937, the house was demolished; however, three intact rooms—the dressing room, the primary bedroom, and the Moorish-style reception room—were preserved, along with other furnishings and architectural features. The Rockefeller family gave the three rooms to the Museum of the City of New York, which in turn gifted the dressing room to the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the bedroom to the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in 2008. The Moorish reception room was transferred to the Brooklyn Museum in 1946. For more on the history of the Worsham-Rockefeller House, see Frelinghuysen et al., “Artistic Furniture of the Gilded Age,” and Shelley Bennett, Art of Wealth: The Huntingtons in the Gilded Age (San Marino, Calif.: Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens, 2013), pp. 46–54. Former curator at the Museum of the City of New York, Margaret Sterns discovered Schastey’s correspondence with Rockefeller, and was the first to identify his firm as the primary decorator of the Worsham-Rockefeller House. Before the exhibition, the only known publication on George A. Schastey and Company was David A. Hanks, “George A. Schastey & Company,” Art & Antiques 6, no. 5 (September–October 1983): 54–57.

C. A. Scheist [sic] arrival on the Guttenberg on October 4, 1849; New York, Passenger and Immigration Lists, 1820–1850, microfilm series M237, reel 84; accessed on Ancestry.com. Details of Schastey’s early life are slim but captured in “Obituary: Captain George A. Schastey,” New York Tribune, December 1, 1894. Information on Schastey’s former employers and early work in California are documented in George A. Schastey, entry dated October 13, 1873, New York, vol. 439, p. 582, R. G. Dun and Co. Credit Report Volumes, Baker Library, Harvard Business School, Cambridge, Mass. Although Rochefort and Skarren, Marcotte and Company, Herter Brothers, and Pottier and Stymus are well known to modern scholars of late nineteenth-century furniture, Conrad Boller is largely unknown. Boller appears in New York City as a cabinetmaker as early as 1860 in U.S. Federal Census (Schedule 5—Products of Industry in 2nd dist., 8th ward in the county of New York . . . during the year ending June 1860, Selected U.S. Federal Census Non-Population Schedules, 1850–1880, p. 9; accessed on Ancestry.com). Boller’s shop received commissions from the New York City government under the corrupt administration of William M. “Boss” Tweed and the Tammany Ring. This ultimately led to Boller’s financial ruin, and he fled New York under suspicions of corruption (“Local Miscellany: Conrad Boller’s Disappearance,” New York Times, May 11, 1877). No works by Boller are known to survive. It was not uncommon in this period for competitors to work collaboratively on large commissions. This is documented by Schastey’s work on the commission from Central Pacific Railroad tycoon Alfred Cohen for his Alameda, California, residence, Fernside (1874–1878). Pottier and Stymus and Herter Brothers served as the principal decorators on the commission; however, correspondence between Cohen and his wife confirms that employees of George A. Schastey were on-site to furnish parts of the dining room. Alfred A. Cohen to Emilie Gibbons Cohen, October 15, 1874, cited in entry for Pottier and Stymus dining suite in Harvey Clars Auction Gallery, Clars July Fine Art & Antique Auction, Day 2 Catalog, July 15, 2012, Oakland, Calif., lot 6293; https://www.liveauctioneers.com/item/12046991_pottier-and-stymus-dining-suite. For more information on Fernside, see Hank Dunlop, “Fernside: The Estate of Alfred Andrew Cohen and Emilie Gibbons Cohen,” 19th Century Magazine 16, no. 2 (1996), pp. 28–37. Schastey served as the principal decorator of the Crocker residence and was awarded a medal for the dining room sideboard he displayed at the 1876 Centennial International Exhibition. “Crocker’s House,” San Francisco Chronicle, June 10, 1877; George Titus Ferris, Gems of the Centennial Exposition (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1877), 140–42.

Schastey’s business address first appears as “33 E. 17th & 208 W. 53d” in Trow’s New York City Directory, For the Year Ending in May 1, 1877, vol. 90 (New York: Trow City Directory Company, [1877]), p. 1207. Schastey’s involvement at the Nickerson residence is mentioned in D. Davis to Mason, May 22, 1881, cited in M. Kirby Talley Jr., This House Was the Pride of the Town: Mr. Nickerson’s Marble Palace Becomes Mr. Driehaus’ Museum (Washington, D.C.: Cottontail Publications, 2008), pp. 13–15. Shastey’s work at the Clark Mansion is confirmed by a surviving Steinway and Sons piano from that house. An entry in the Steinway and Sons’ company log books corresponding to the piano’s serial number confirms that Schastey made the piano’s art case for William Clark (Archives of Steinway and Sons, communicated via email correspondence). The Samuel Nickerson and William Clark Houses were both featured in Artistic Houses, although Schastey’s contributions went unmentioned in the descriptions of both residences. Artistic Houses: Being a Series of Interior Views of a Number of the Most Beautiful and Celebrated Homes in the United States . . . (New York: printed for the subscribers by D. Appleton and Company, 1883–1884), vol. 1, pt. 2, pp. 144–47, vol. 2, pt. 1, pp. 48–55.

. In 1880 Schastey added William M. Williams, an upholstery and trims merchant, as a partner and changed the firm’s name from George A. Schastey to George A. Schastey and Company. George A. Schastey, entry dated February 24, 1880, New York, vol. 439, p. 600E, R. G. Dun and Co. Credit Report Volumes, Baker Library, Harvard Business School, Cambridge, Mass. Schastey’s business address first appears as “228 W. 53d & 1681 B’way” in Trow’s New York City Directory, For the Year Ending in May 1, 1886, vol. 99 (New York: Trow City Directory Company, [1886]), p. 1684. A description of his new Broadway showroom appears in “New-York’s Bankers, Merchants, and Manufacturers,” New York Times, August 18, 1885. For more information on Arabella and Collis Huntington’s other New York City residences, see Bennett, Art of Wealth, pp. 57–63 (Throggs Neck), pp. 66–67 (5 West Fifty-First Street), and pp. 79–95 (25 East Fifty-Seventh Street). Schastey worked for Collis Huntington as early as 1878, when he executed work for his residence at 65 Park Avenue, New York City. On November 9, 1878, Schastey invoiced Huntington for $3,750 for refurbishments to his Park Avenue house. Collis P. Huntington Papers, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University, Syracuse, N.Y., microfilm series III, reels 14, 15, and 19, cited in Bennett, Art of Wealth, p. 26. Many thanks to Shelley Bennett for sharing her extensive research on the Huntingtons with the American Wing. The firm’s work for Edward C. Hegeler came from Schastey’s relationship with W. August Fiedler (1843–1903), a German-American designer previously associated with the New York furniture trade, who went bankrupt after establishing a decorating firm in Chicago. David Bagnall, An American Palace: Chicago’s Samuel M. Nickerson House (Chicago: Richard Driehaus Museum, 2011), pp. 36–38. After John D. Rockefeller purchased Worsham’s house at 4 West Fifty-Fourth Street, he continued to patronize Schastey and Company for minor improvements and furniture needs. Correspondence between Schastey and Rockefeller regarding such work dates from 1884 until 1893. Papers of John D. Rockefeller Sr., Part 3, Office Correspondence, 1879–1894, reel 33, Rockefeller Archive Center.

“Though the amount of their business has been financially affected by the depression, they have done fairly and financially maintained previous record;” George A. Schastey and Company, entry dated January 8, 1885, New York, vol. 439, p. 600A, B, R. G. Dun & Co. Credit Report Volumes, Baker Library, Harvard Business School, Cambridge, Mass. Schastey consolidated the Springfield Wood-Working Company into George A. Schastey Company, Springfield. “A New Wood-Working Company: Which Will Double the Capacity of the Present Concern on Hillman Street,” Springfield Republican (Springfield, Mass.), April 4, 1890. The Springfield firm published a catalogue that advertised moderately priced stock furniture. George A. Schastey Company, Springfield, Occasional Pieces of Choice and Useful Household Furniture (Springfield, Mass.: F. A. Bassette Company, ca. 1890), p. 3. George Schastey died in 1894 and his New York business continued under his sons and brother. “Obituary: Captain George A. Schastey,” New York Tribune, December 1, 1894; and “Legal Notices,” New York Times, February 24, 1897. Acts and Resolves Passed by the General Court of Massachusetts in the Year 1907 . . . , published by the Secretary of the Commonwealth (Boston: Wright & Potter Printing, Co., 1907), p. 235.

For more information on the aesthetic movement, see Burke et al., In Pursuit of Beauty.

Although doubts persisted over the years as to who was the author of Worsham’s splendid interiors, the previously cited correspondence between Schastey and the house’s final owner, John D. Rockefeller in October 1884 confirmed Schastey’s authorship. For more on the Worsham-Rockefeller Dressing Room, see Frelinghuysen et al., “Artistic Furniture of the Gilded Age,” pp. 8–16. Many thanks to Paul Manganaro and Richard Wolfin for bringing this piano to the attention of the American Wing. The Steinway and Sons log books record that the piano, a model B, was completed on April 27, 1882, then delivered to Schastey and Company on June 13, 1882, to have its art case constructed. The completed instrument was delivered to Clark on December 30, 1882 (Archives of Steinway and Sons, communicated via email correspondence). Artistic Houses, vol. 1, pt. 2, pp. 144–47. The William Clark House still stands and is now the headquarters of the North Ward Center, Newark, New Jersey.

Hanks, “George A. Schastey & Company,” pp. 54–57. The cabinet at Mission Inn was first published in John Werry, “Could It Be Herter Brothers?,” Rare Victorian blog, June 13, 2010, http://rarevictorian.com/2010/06/could-it-be-herter-brothers.html. This piece was also identified during research for the 1994–1995 exhibition “Herter Brothers: Furniture and Interiors for a Gilded Age,” American Wing research files, Metropolitan Museum of Art. For Schastey’s work at the Nickerson mansion, see D. Davis to Mason, May 22, 1881, cited in Talley, This House Was the Pride of the Town, pp. 13–15. The firm’s involvement at the James Flood mansion was published in “A New Wood-Working Company. . . ,” Springfield Republican (Springfield, Mass.), April 4, 1890.

Many thanks to Margot Johnson for bringing Worsham’s drawing room cabinet, now in the collection of the Seattle Art Museum, to the attention of the American Wing. The Tiffany and Company order book confirms Schastey made the clock’s case. Order no. 194, April 4, 1882, delivered on August 21, 1882. Tiffany and Company, “Order Book, 1879–1918, Clock Department, New-York Historical Society. The tall case clock has an oral history of being purchased at an auction held at the Clark mansion in the 1970s, when the property was sold by the Prospect Hill Country Day School.

Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide (Brooklyn, N.Y.) 32, no. 819 (November 24, 1883): 926–927.

Many thanks to Anna Tobin D’Ambrosio for graciously sharing her insights on this worktable and its connection to George A. Schastey with the American Wing. Photographs of Worsham’s bedroom taken circa 1883 and recently identified by Shelley Bennett in the collection of the Hispanic Society of America, New York, confirm that this piece was originally in Worsham’s bedroom.

“New-York’s Bankers, Merchants, and Manufacturers,” New York Times, August 18, 1885.

Widely published design books such as Owen Jones’s Plans, Elevations, Sections, and Details of the Alhambra (1836–45) and The Grammar of Ornament (1856) provided colorful images of architectural details and other ornamental motifs from around the world that inspired designers throughout the late nineteenth century; although, it remains unknown which publications Schastey’s designers may have referenced. This pair of town houses were built on prospect by Andrew J. White and designed by architect James A. Ware, “New Buildings,” New York Times, June 29, 1882. The interiors received a laudatory review in the periodical Art Age, praising Schastey and Company’s work, “not only for its beauty, but for its mechanical perfection.” “Mr. A. J. White’s House,” Art Age 3, no. 34 (May 1886): 181.

In keeping with the newfound popularity of artistic leaded glass, such as that made by John La Farge (1835–1910) and Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848–1933), Schastey and Company incorporated decorative leaded glass into doors, windows, transoms, and lighting fixtures in many of its commissions. For the Worsham commission, Schastey incorporated a series of leaded-glass windows by La Farge, including two large windows depicting allegorical figures of Morning and Evening, now in the collection of the Academy of Arts and Letters, New York. Such elaborate compositions required the skills of an expert glass artist. However, it is possible that Schastey’s designers may have provided the designs for the smaller nonfigural panels, such as the leaded-glass panel of the tall case clock discussed in this article and smaller transom panels associated with the Worsham, Nickerson, Clark, and Huntington residences.

For the built-in elements of the Worsham-Rockefeller Dressing Room, the purpleheart putti were carved and applied to the surface of the vanity; however, on the wardrobe and dressing mirror, the putti and other carved details of purpleheart were set into substrate material before satinwood veneer was applied around them. Setting the purpleheart into the substrate material was incredibly laborious and required expert skill. It is unclear why this approach was used only on two of the room’s built-in components and does not appear in Schastey’s other work that utilizes the same materials and ornamental motifs, such as the piano or the dressing table at the High Museum of Art.

Scholar Anne Higonnet proposed that the imagery of the lion and lioness was selected by Arabella Worsham to ornament her house as a symbol of her ferocious ambition. Both Arabella and her later husband Collis Huntington came from modest backgrounds and rose to become two of the wealthiest individuals in America. Higonnet, “The Lioness,” in series “Artistic Furniture of the Gilded Age,” MetSpeaks (lecture), February 11, 2016, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The serial number on this wall clock matches the entry in the Tiffany and Company clock log book that confirms the works were ordered to accompany a case made by George A. Schastey and Company. Order no. 89, Fall 1880, delivered on June 30, 1881. Tiffany and Company, Order Book, 1879–1918, Clock Department, New-York Historical Society.

“New-York’s Bankers, Merchants, and Manufacturers,” New York Times, August 18, 1885. Although there has been no documentation of such a library at George A. Schastey and Company, the broad distribution of design-related texts and the advent of photography allowed manufacturers in various media to compile such collections for their designers.

Bagnall, An American Palace, pp. 47–48.

Many thanks to David Petrofsky and Max Foote for bringing this chair form to the attention of the American Wing.

For more information on the Metcalf House stair hall, see Amelia Peck et al., Period Rooms in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1996), pp. 269–273.

For more information on Schastey’s competitors’ use of hardware, see Howe, Herter Brothers, pp. 121–23, n. 20.

A catastrophic fire in October 1893 likely accounts for the lack of any business records from George A. Schastey and Company’s New York operation. “Four Millions in Smoke: Buildings on Two Blocks Swept Away by Flames,” New York Times, October 19, 1893. Other documented commissions not discussed in this article include the Stephen Mann Blank Mansion, New York City (demolished) (“Advertisement,” New York Herald, April 26, 1886, issue 116, 9); residence at West One Hundred Third Street and Riverside Drive, New York (demolished) (“Advertisement,” New York Herald, December 30, 1888 and March 31, 1889); and the residence of Charlotte H. F. Skidmore, Madison Avenue and Sixty-Seventh Street, New York (demolished) (“Sales at Auction,” New York Herald, January 18, 1898). To date, no surviving material from these houses has been located.