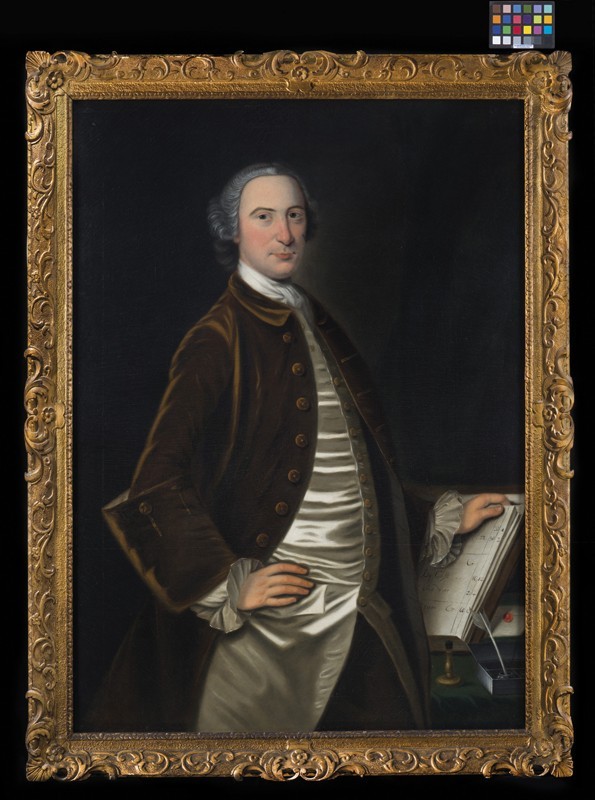

Frame on Lawrence Kilburn’s portrait of James Beekman, attributed to Stephen Dwight, New York City, 1762. White pine; gilded. 52 3/4" x 40". (Courtesy, New-York Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) In the September 14, 1761, issue of the New-York Mercury, Dwight advertised an “Assortment of Picture Frames of the newest Fashions.” Like many carvers, Dwight probably imported frames in addition to making them.

Frame on Lawrence Kilburn’s portrait of Jane (Keteltas) Beekman, attributed to Stephen Dwight, New York City, 1762. White pine; gilded. 52 3/4" x 40". (Courtesy, New-York Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest of drawers with casework attributed to Thomas Brookman and carving attributed to Henry Hardcastle, New York City, 1750–1755. Mahogany with tulip poplar. H. 33 5/8", W. 37", D. 21 3/8". (Private collection; photo, Andrew Davis.)

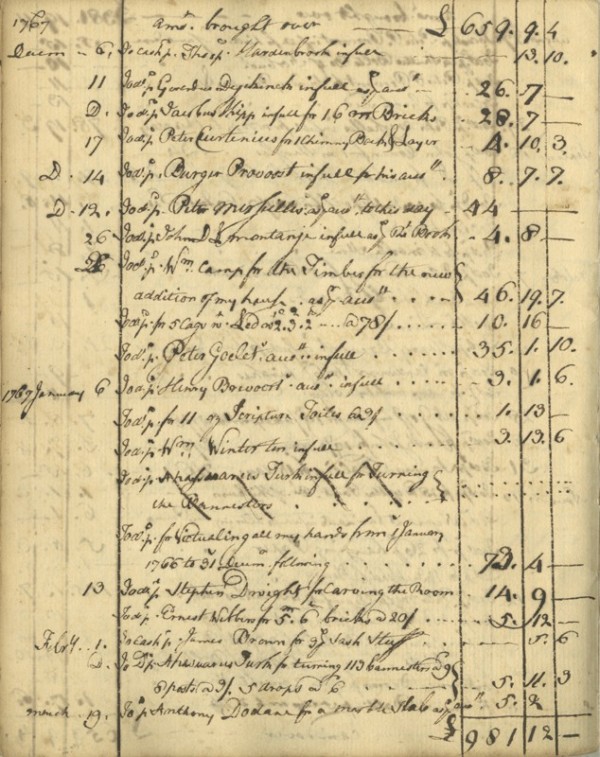

Entry from James Beekman’s daybook, January 6, 1767. (Courtesy, New-York Historical Society.)

Chest of drawers with casework attributed to Thomas Brookman and carving attributed to Henry Hardcastle, New York City, 1750–1755. Mahogany with tulip poplar. H. 33", W. 35 1/2", D. 20 3/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Desk-and-bookcase with casework attributed to Thomas Brookman and carving attributed to Henry Hardcastle, New York City, 1750-1755. Mahogany with tulip poplar and gum. H. 99 1/2", W. 45 1/2", D. 25". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The outermost portions of the pediment appliqué and heron ornament are restorations based on carved ornaments in Philipse Manor.

Details showing the feet of the chests of drawers illustrated in fig. 3 (left), the chest of drawers illustrated in fig. 5 (middle), and the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 6 (right). The carving on the desk-and-bookcase is in higher relief than that on the chests, but the outlining, modeling, and shading cuts on all of the comparable leaf forms are consistent with Hardcastle’s work. The shallow leafage on the feet of the chests also relates to the architrave carving on the overmantel in the first-floor parlor of Philipse Manor (fig. 8) and the knee carving on a card table attributed to Hardcastle.

First-floor, southeast parlor, Philipse Manor, Yonkers, New York, ca. 1750. (Courtesy, Philipse Manor Hall State Historic Site, Yonkers, New York, New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Second-floor, southeast parlor, Philipse Manor, Yonkers, New York, ca. 1750. (New York State Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

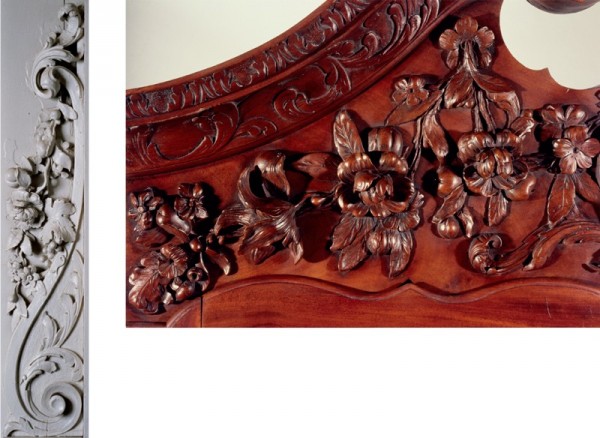

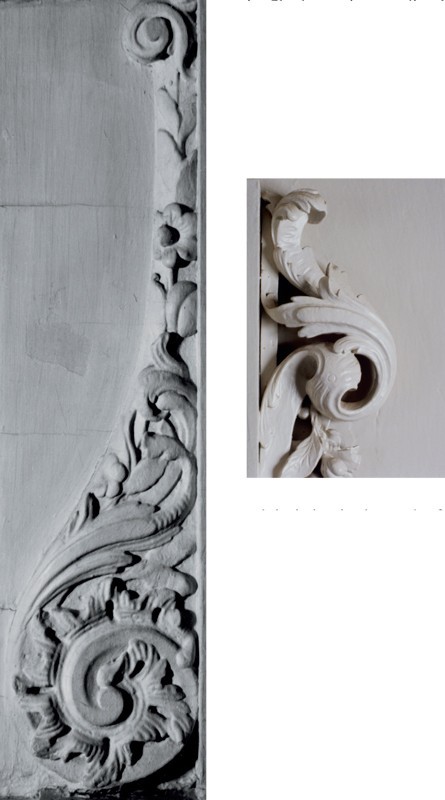

Details of the left side bracket on the chimneypiece illustrated in fig. 9 and the left side of the pediment appliqué on the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 6 (Photos, Gavin Ashworth.)

Details of the right rosette on the chimneypiece in the first-floor southeast parlor in Philipse Manor (fig. 8) and the right rosette on the pediment of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 6. (Photos, Gavin Ashworth.)

Abram Hosier, Mount Pleasant, New York City, 1874. Watercolor on paper. 15 1/2" x 26 1/4". (Courtesy, New-York Historical Society.)

Chimneypiece from Mount Pleasant, carving attributed to Stephen Dwight, New York City, 1767. (Courtesy, New-York Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Beekman coat of arms, attributed to Stephen Dwight, New York City, ca. 1767. H. 21 1/4", W. 15", D. 3 1/2". (Courtesy, New-York Historical Society.)

Beekman coat of arms, attributed to Stephen Dwight, New York City, ca. 1767. H. 21", W. 16 1/4", D. 3 1/2". (Courtesy, New-York Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing the upper left rosette on the chimneypiece illustrated in fig. 13. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the frieze appliqué on the chimneypiece illustrated in fig. 13. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the frieze appliqué on the chimneypiece illustrated in fig. 9.

Desk-and-bookcase with casework attributed to Thomas Brookman and carving attributed to Henry Hardcastle or Stephen Dwight, New York City, ca. 1755. Mahogany with tulip poplar and gum. Dimensions not recorded. (Private collection; John Walton Antiques.)

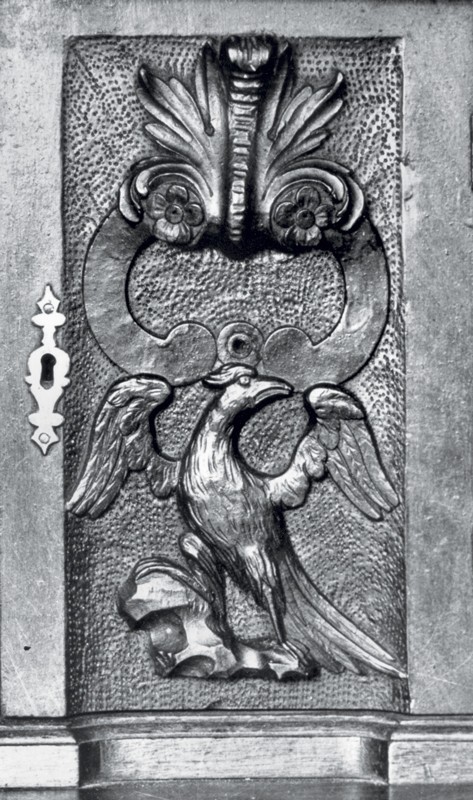

Detail of the prospect door of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 19.

Detail of the left truss on the chimneypiece illustrated in fig. 13. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Entrance hall from Van Rensselaer Manor, Albany, New York, 1765–1768. (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

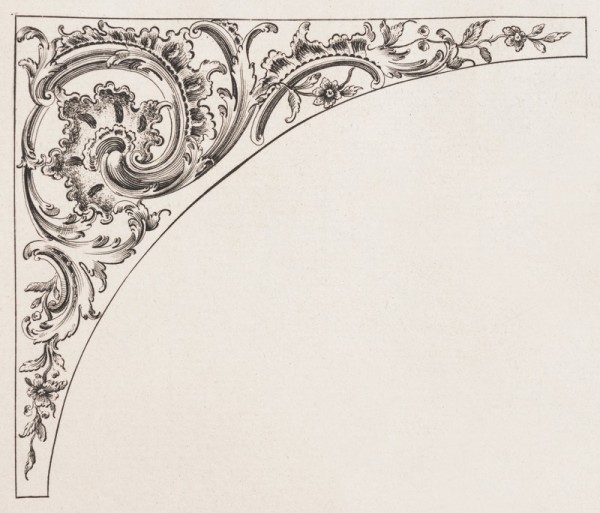

Detail of a spandrel appliqué in the entrance hall illustrated in fig. 22. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Design for a spandrel illustrated on plate 10 of Matthias Lock and Henry Copland’s A New Book of Ornaments (first ed., 1752). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Interior of St. Paul’s Chapel, Broadway and Fulton Street, New York City, 1764–1766. (Courtesy, St. Paul’s Parish of Trinity Church; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Cartouche over the Venetian window illustrated in fig. 25. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing the frieze of the pulpit stair in St. Paul’s Chapel. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Wallpaper panels in the entrance hall from Van Rensselaer Manor, Albany, New York, installed 1768. (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Wallpaper panel in the entrance hall from Van Rensselaer Manor, Albany, New York, installed 1768. (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Details showing leaves on the trusses from Hampton Place (left) and Philipse Manor (right).

In a 1990 article in Furniture History, Morrison H. Heckscher illustrated one of two picture frames documented to carver Stephen Dwight, made for Lawrence Kilburn’s portraits of New York merchant James Beekman (1732–1807) and his wife, Jane (Keteltas) (figs. 1, 2). The frames cost £11.10 and appear to have been copied from the British example on Kilburn’s portrait of James’s brother Abraham. Because the ornaments on Dwight’s frames are derivative, roughly modeled, and somewhat muted by gesso and gold leaf, they have offered scholars little help in attributing other work to him. A subsequent article in American Furniture included additional biographical information on Dwight and posited that several examples of architectural and furniture carving were products of his shop. All of those attributions were based on stylistic and technical parallels between that work and carving associated with Dwight’s master, Henry Hardcastle, rather than on archival evidence. This essay will present new documentary information that supports those attributions and places Dwight at the forefront of carvers active in New York City during the third quarter of the eighteenth century.[1]

Stephen Dwight was born in New York circa 1736. His parents, Thomas, a shipbuilder, and Cathalyntje (Biddue), were members of the New York City Dutch Reformed Church, where two of the carver’s older siblings—Joseph and Anna—were baptized. Stephen served his apprenticeship in the shop of Henry Hardcastle, who apparently trained with Henry Leech, a carver from St. Martin in the Fields, London. On September 25, 1736, Leech’s widow, Margaret, released an apprentice named Henry Hardcastle from his indenture. Hardcastle subsequently established a shop at St. James Clerkenwell, where he took Benjamin Saunders as an apprentice on October 25, 1743. The precise date when Hardcastle arrived in New York is not known, but he received freeman status there on June 4, 1751. Judging from his surviving work, Hardcastle maintained a relatively small shop. His only known apprentices, Dwight and John Mooney, both ran away in 1755, and Hardcastle moved to Charleston, South Carolina, where he died in October 1756. At the time of his departure, Dwight must have been nearing the end of his term. On July 21, 1755, “STEPHEN DWIGHT, late an apprentice to Henry Hardcastle” advertised that he had “set up his business, between the Ferry Stairs and Burlings Slip, where he carves all sorts of ship and house work; also tables, chairs, picture and looking-glass frames and all kinds of work for cabinetmakers, in the best manner and all on reasonable terms.” It took Dwight little time to establish himself in his trade. He married Martha Glover in the Dutch Reformed Church on September 21, 1757, and relocated five years later. On April 19, 1762, the New-York Gazette reported that Dwight was moving into the house of “Mr. Johnston Cabinetmaker” and the shop “opposite, where Mr. Osborne, Cabinet Maker, now lives, . . . near the Moravian Meeting.” In that notice, Dwight announced his intention to “follow Carving in General . . . and also Portrait and History Painting” and to “teach drawing in Crayon, black and white Chalk, India Ink, and black Lead Pencil, in the quickest and best Manner.” Dwight appears to have worked independently until circa 1774, when he formed a partnership with carver Richard Davis. On March 10 of that year, he advertised that “Dwight & Davis continue to carry on the business of carving as usual, where ladies or gentlemen may be supplied with girandoles, looking glasses, and picture frames.” Although work by their firm has not been identified, Davis must have been a competent carver. He was listed in later city directories at 25 Vesey Street and led the carvers and engravers in the Federal Procession in New York in 1788.[2]

It is unclear how Dwight was able to set up shop less than a month after running away from Hardcastle, but Stephen’s access to his master’s patrons probably contributed to his early success. Two of Dwight’s clients owned nearly identical commode-front chests with carving attributed to Hardcastle. The example illustrated in figure 3 descended in James Beekman’s family and may have been among the household furnishings he purchased from Thomas Brookman in 1752 (figs. 3, 4), and the other chest reputedly belonged to Stephen Van Rensselaer II (1742–1769) (fig. 5), whose house in Albany had carving attributed to Dwight’s shop. Both chests have carved tops and ogee feet with acanthus leaves similar to those on a monumental desk-and-bookcase with appliqués related to those in Philipse Manor (figs. 6, 7), the only surviving house with interior ornament attributed to Hardcastle (figs. 8-10). All three case pieces have drawers with fully paneled bottoms and thin dustboards with broad beveled edges (front and sides) that are set into grooves plowed in the drawer blades and drawer runners, which are dadoed, notched, and nailed into the case sides. These shared details suggest that all three pieces are from Brookman’s shop. He may also have fabricated some of the interior architectural components for Philipse Manor. The overmantle in the first-floor parlor has a low, broken-scroll pediment, moldings, and rosettes similar to those on the pediment of the desk-and-bookcase (figs. 6, 8, 11). Cabinet shops occasionally produced interior woodwork, and a 1748 list of freemen in New York has an entry for a “carpenter” named Thomas Brookman.[3]

James Beekman was clearly one of Dwight’s most important patrons. Between 1760 and 1764 the merchant spent £1,123 enlarging and refurbishing his house on Queen Street, which included paying Dwight for “carving 4 flowers for my New roome.” Those appliqués were probably for the crosseted corners of doors, windows, or a chimneypiece architrave. In 1763 Beekman purchased land on the East River between Forty-Ninth and Fifty-First streets for £738 and began constructing Mount Pleasant. Within a year, he had spent an additional £1,967 for “utensils, and creatures . . . cost of materials, Labor, and Victuals.” Although the house was demolished in 1874, nineteenth-century depictions indicate that it was a five-bay frame-and-clapboard dwelling with four chimneys and a roof balustrade (fig. 12). A contemporaneous description of the house appeared in the October 12, 1872, issue of the New York Times:

Entering the front door a fine wide hall greets the view, on each side of which are somewhat low doors opening into the rooms formerly occupied as library and dining hall. . . . The old dining-room . . . is much grander [than the library]. Over the door are pediments . . . in the somewhat heavy style of the Dutch of the seventeenth century. . . . [on] the mantle-piece, which is of a black marble, “bleu belge,” is some elaborate carving of foliage and scroll, out of which a dog and two swans, in mezzo relieve…. The bannisters [of the staircase] are of solid mahogany, the railings very handsomely carved. . . . At the head of the stairs the corridor is reached, which is of the same dimensions as the hall below, the whole length of the house with a width of seventeen feet. . . . Here from the pretty corridor . . . the visitor steps into what was the suite of the house. There is a heavy wainscot, above which the walls are painted of a deep cobalt blue, with an elegant cornice of molding and gilding. . . . The plaster of Paris moldings in the center of the ceiling are of very superior workmanship. . . . The mantel-pieces in each room exactly correspond . . . and have both the same odd side cupboards. The decoration of the fireplaces consists of old Dutch tiles, with Scriptural subjects.

A recently discovered daybook maintained by James Beekman contains numerous entries pertaining to the construction of Mount Pleasant, including a credit of £14.9 to “Stephen Dwight for Carving the Room” on January 6, 1767. That work almost certainly included the chimneypiece illustrated in figure 13 and may have included two carved coats of arms (figs. 14, 15). According to an article in the April 1860 issue of the Ladies’ Repository, one of the coats of arms hung over the chimneypiece before that object was removed from the house.[4]

Beekman’s daybook entry and the style of the carving on the chimneypiece leave little doubt that Dwight was responsible for all of the ornaments in Mount Pleasant. The crossette appliqués on the Beekman chimneypiece (fig. 16) are clearly related to the rosettes attributed to Hardcastle on the chimneypiece in the first-floor parlor of Philipse Manor and the pediment of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in figure 11. Both sets of flowers have broad convex petals with deeply fluted and veined depressions and flat half-petals in the background. Similar rosettes appear on a New York desk-and-bookcase said to have descended in the Cotton Mather Smith family.[5]

No exact design source for the dog and swans on the chimneypiece has been identified (fig. 17), but similar animals are depicted in eighteenth-century furniture and architectural designs, particularly those for chimneypieces, looking glasses, and pier tables. Dogs and fowl are also depicted in combative postures in period paintings and engravings, the latter of which were widely distributed and, as exemplified by the work of Francis Barlow, reinterpreted by carvers. The animals on the chimney are less sculptural than those attributed to Hardcastle, but Dwight’s use of short, paired gouge cuts to articulate the dog’s fur and swans’ feathers has precedents in his master’s work. Hardcastle used the same techniques to simulate fur on the feet of a monumental paw-foot bedstead and the body feathers of the heron in the center of the frieze appliqué of the chimneypiece in the second-floor southeast parlor of Philipse Manor (fig. 18). Similar carving appears on the body feathers of the heron on the prospect door of a desk-and-bookcase that descended in Peter Stuyvesant’s (1727–1805) family, although it is difficult to determine whether that work was done by Hardcastle or Dwight (figs. 19, 20).

As the trusses on the chimneypiece from Mount Pleasant and those in the second-floor parlor of Philipse Manor reveal, Dwight’s work is much less naturalistic than Hardcastle’s. Many of the leaves on the trusses and appliqué on the Beekman chimneypiece terminate in tight clusters of rounded lobes, and most of their convex elements are articulated with short gouge cuts made perpendicular to the flow of the design (fig. 21). Hardcastle used similar cuts in the same context, but not nearly as extensively as his former apprentice.

It is unclear if the Beekman coats of arms were included in the £14.9 payment to Dwight, but they are undoubtedly from his shop (figs. 14, 15). The principal difference between the two armorials is the presence of a bird’s head on one. Tradition maintains that the bird’s head signified the colonial branch of the family, whereas the other denoted the European branch. The former design was also painted on James Beekman’s coach. Since Dwight’s coats of arms probably predate the coach, their designs may have been inspired by armorials on Beekman’s silver, bookplates, or other decorative arts.

For the spandrel appliqués in Stephen Van Rensselaer’s manor house in Albany, New York, Dwight copied elements from plate 10 in Matthias Lock and Henry Copland’s A New Book of Ornaments (first ed., 1752) (figs. 22-24). Although there is no documentary evidence of that book being in colonial New York, Heckscher speculated that Van Rensselaer “probably acquired a copy from his father-in-law Philip Livingston (who was living in London).” As was the case with Mount Pleasant, the hall in Stephen’s house was an important public space, providing access to the stair and adjoining rooms. The woodwork includes six doorways with crossetted surrounds, pulvinated friezes, and pitch pediments; four recessed, paneled windows; and an elliptical archway flanked by fluted Ionic pilasters. Shortly after the interior was completed, Stephen ordered hand-painted wallpaper depicting the four seasons. He had originally planned to install an ornamental stucco ceiling; however, Livingston advised him otherwise: “I am told You Intend to gett Stucco Work on the Ceiling of Your Hall which I would not advise You to do, a Plain Ceiling is now Esteemed the most Genteel.”[6]

In their complexity, the spandrel appliqués are matched only by a cartouche from St. Paul’s Chapel (figs. 25, 26). Both designs have elaborate scrollwork and multiple layers of acanthus leaves, the latter of which have convex surfaces articulated in precisely the same manner as those on the Beekman chimneypiece. Several of the flower and fruit elements on the spandrel appliqués also appear on other carving in St. Paul’s Chapel (fig. 27) and on the Beekman chimneypiece (figs. 17, 21). No records for the construction of St. Paul’s are known, but the carving in the church may predate that from the Beekman and Van Rensselaer houses. Tradition maintains that the architect was Scottish immigrant Thomas McBean; however, recent scholarship suggests that Peter Harrison may have been involved in the design. On June 23, 1764, the church paid John Dies £600 for “his Bond & Mortgage per order of Mr. Marston & Mr. Harrison payable [illegible] 9th June 1763.”[7]

The most unusual carving in St. Paul’s is the relief work on the frieze of the pulpit stair (fig. 27). Several of the leaf, scroll, and flower elements are repeated in other work attributed to Dwight, but the design has several awkward passages and may have been laid out with several patterns, including one used for the scrolls and leafage on the stair brackets. Dwight’s frieze most closely resembles the rococo borders on contemporaneous wallpaper panels like those in the entrance hall from Van Rensselaer Manor (figs. 28, 29). Although wallpaper has not been studied as a design source, it is possible that Dwight and other colonial carvers copied details from, or were at the least inspired by, imported papers.

A drawing of the south elevation of St. Paul’s is inscribed, “This is the plan designed for the New Church to be executed by Messrs. Gautier and Willis 17th of July 1764.” Between March 25, 1762, and December 22, 1768, Andrew Gautier received £4,689.12.4, primarily “for the use of St. Paul’s Church.” Most of the construction appears to have been completed by October 1766, when the New York Gazette reported, “On Monday, 27th . . . the pews in St. Pauls Chapel will be let at public auction . . . and on the Tuesday following the chapel will be opened, and a sermon preached.” A subsequent account of the opening described the church as “one of the most elegant edifices on the continent” and noted that “the Mayor and Corporation of the City” and Governor Henry Moore attended the service.[8]

St. Paul’s was not the only public building for which Dwight provided carving. On May 30, 1775, the Common Council of the City of New York instructed the treasurer to pay “Messrs. Dwight & Davis . . . Nineteen Pounds, two Shillings in full for their Account for Work done Ornamenting the Court Room in the City Hall.” The duration of the carvers’ partnership remains unknown, but Dwight eventually moved to Newark, New Jersey, whereas Davis remained in New York. Dwight had earlier connections to two Newark residents, Dr. William Barnet and schoolteacher William Haddon, who mentioned the carver in a 1768 advertisement. The earliest architectural carving associated with Dwight is in a parlor from Barnet’s house, known after the owner’s death as Hampton Place.[9]

In his October 1, 1785, will, Dwight left his second wife, Hannah, all of his estate in Newark as well as the estate she had inherited from her father for her use until Dwight’s daughter Dorothy came of age. Dwight’s son Stephen received all of the carver’s property in New York, which was located on William Street. The executors of the will were Newark chairmaker Isaac Alling and Richard Davis, whom Dwight described as his “well beloved friend.” An “Account of Monies received & paid for the Estate of Stephn” Dwight decd included a disbursement of £18.6.9 to Davis. Described as “the balance of . . . [Davis’s] Acct ,” this payment may have been the final settlement of his partnership with Dwight.[10]

The furniture and architectural carving attributed to Dwight and Hardcastle show how apprentices adopted the drawing styles and working methods of their masters and adapted both to changing styles and consumer tastes. Dwight learned his trade from one of the most highly skilled carvers who immigrated to the colonies, a craftsman who had trained in London during the early 1730s and witnessed the emergence of the rococo style before immigrating around midcentury. Hardcastle’s most significant carving—exemplified by the pediment appliqué on the desk-and-bookcase and architectural carving in Philipse Manor—is incredibly sculptural, highly detailed, and exceedingly complex in terms of tool use. His inventory, taken in Charleston in 1756, listed 216 “Carving Tools.” As one might expect, Dwight’s earliest work closely resembles that of his master. This is most evident in the leafage from Hampton Place, which is Dwight’s earliest architectural carving, and Philipse Manor (fig. 30). What is surprising is how quickly Dwight’s work began to diverge from that of his master in both composition and technique. By the mid-1760s only subtle details linking the two hands are discernible. Evidence of such profound stylistic and technical deviation in the work of master and apprentice is significant; it shows how craftsmen could adapt even the most habitual aspects of their trade to suit changing styles and consumer tastes and how important it is to observe and weigh myriad details in studies of their work.[11]

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For assistance with this article, the authors thank Gavin Ashworth, Lauren Brincat, Natalie Brody, Alyce Englund, Leigh Keno, Susan Newton, Lauri Perkins, and Jon Prown.

Morrison H. Heckscher and Leslie Greene Bowman, American Rococo: Elegance in Ornament (New York: Harry N. Abrams for the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1992), pp. 156–57; For more on Dwight’s frames, see Morrison H. Heckscher, “The Beekman Family Portraits and Their Eighteenth-Century New York Frames,” Furniture History 26 (1990): 114–20. Luke Beckerdite, “Immigrant Carvers and the Development of the Rococo Style in New York, 1750–1770,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1996), pp. 233–65.

“Records of the Reformed Dutch Church in New York,” New York Genealogical and Biographical Record 21, no. 4 (October 1890): 155; and 22, no. 1 (January 1891): 12; Names of Persons for Whom Marriage Licenses Were Issued by the Secretary of the Province of New York, Previous to 1784 (Albany: New York State Archives, 1860), p. 123. Dwight Family Miscellany file, New York Public Library. In the June 30, 1755, issue of the New York Mercury, Hardcastle reported that his apprentice Stephen Dwight had run away. “Henry Hardcastle, apprentice—for release from Margaret, widow of Henry Leech of St. Martins in the Fields, carver,” September 25, 1736, ref. MJ/SP/1736/09/25, London Metropolitan archives, http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/rd/b2ef2f90-101e-4726-a08a-8274b5713054. Saunders’s indenture is recorded in A Biographical Dictionary of Sculptors in Britain, 1600–1851, online database, Henry Moore Foundation, Paul Mellon Centre. “The Roll of Freemen of New York City, 1675-1866,” in Collections of the New-York Historical Society for the Year 1885, vol. 18 (New York: New-York Historical Society, 1885), p. 173. Hardcastle probably moved to Charleston, South Carolina shortly after Dwight ran away in June 1755 and before the latter advertised independently the following July. Hardcastle was buried in Charleston on October 20, 1756 (Register of St. Phillip’s Parish, Charles Town, or Charleston, S.C., 1754-1810, compiled by D. E. Huger Smith and S. A. Sally Jr. [Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1971], p. 282). For more on Hardcastle and his work, see Luke Beckerdite, “Origins of the Rococo Style in New York Furniture and Interior Architecture,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1993), pp. 15–37; and Beckerdite, “Immigrant Carvers.” The partnership of Dwight and Davis is mentioned in Rivington’s New-York Gazette, March 10, 1774. New York engraver Alexander Anderson recalled marching next to Davis, who led the carvers and engravers and whose son and namesake held the group’s silk banner (Robb K. Haberman, “Periodical Publics: Magazines and Literary Networks in Post-Revolutionary America” [Ph.D. diss., University of Connecticut, 2009], p. 17 n. 19).

Keno Auctions, Inaugural Sale, New York, May 1–2, 2010, lot 259. Brookman attained freeman status in 1744 (“The Roll of Freemen of New York City” p. 143). James Beekman daybook, 1763–1793, Beekman Family Papers, 1720–1920s, ms 51, Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, New-York Historical Society. For the history of the Van Rensselaer chest, see Winterthur acc. file G54.86.

“Account of Repairs of My Dwelling House,” in James Beekman account book, 1761–1796, Beekman Family Papers, New-York Historical Society; James Beekman daybook, 1763–1793, New-York Historical Society.

Advertisement by French & Co., Inc., Antiques 52, no. 2 (February 1950): 105. The authors have not examined this desk-and-bookcase.

For more on the Van Rensselaer House and family, see Katherine Schuyler Baxter, A Godchild of Washington: A Picture of the Past (New York: F. Tennyson Neely, 1897), pp. 414–19; and Some Colonial Mansions and Those Who Lived in Them, edited by Thomas Allen Glenn, (Philadelphia: Henry T. Coates & Co., 1898), pp. 156–68. These early publications allude to other architectural carving, which may have been part of the original fabric of the house, as well as to subsequent alterations made by architect Richard Upjohn. For Upjohn’s alterations, see Edgar Mayhew and Minor Myers, A Documentary History of American Interiors from the Colonial Era to 1915 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1980), p. 55. For more on the entrance hall, see Heckscher and Bowman, American Rococo, pp. 23–25. John Baptist Jackson wrote of wallpaper, “Saloons in Imitation of Stucco may be done in this manner, and Staircases in every Taste as may be agreeable. These papers being done in oil, the Colour will never fly off—no water or damp can have the least effect on it” (Jackson, “An Essay on the Invention of Engraving and Printing in Chiaro obscuro, as Practised by Albert Durer, Hugo di Carpi, etc. and the Application of It to the Making of Paper Hangings of Taste Duration and Elegance,” as quoted in Nancy McClelland, Historic Wall-Papers [Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, Co., 1924], pp. 144–49).

The building of St. Paul’s is discussed in Parish of Trinity Church, St. Paul’s Chapel of the Parish of Trinity Church Broadway and Fulton Street, brochure; Morgan Dix, Historical Records of St. Paul’s Chapel, New York (New York: F. J. Huntington & Co., 1867), pp. 26–29; and Morgan Dix, A History of the Parish of Trinity Church in the City of New York (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1896), pp. 302–5. For more on McBean, see Gulian Verplank’s letter to the editor, “Notes and Queries,” The Crayon (New York), June 1857. Verplank and subsequent writers have speculated that McBean trained with British architect James Gibbs. John F. Millar of Williamsburg, Virginia, attributed St. Paul’s church to Harrison (John F. Millar, “Peter Harrison, 1716–1775,” brochure, copy in the archives of Trinity Parish, New York). Trinity Parish Account Book, 1756–1769, RG2: SG1,2,3: Box 3 [2]; transcribed information provided by the Parish of Trinity Church.

For Gautier, see St. Paul’s Chapel; Dix, History of the Parish of Trinity Church, pp. 302–5; and The Arts and Crafts of New York, 1726–1776: Advertisements and News Items from New York City Newspapers, Collections of the New-York Historical Society, compiled by Rita S. Gottesman (1958; reprint, New York: Da Capo Press, 1970), pp. 97, 112–13, 118, 281, 395. As quoted in Dix, Historical Records of St. Paul’s Chapel, p. 27.

Minutes of the Common Council of the City of New York, 1675–1776, 8 vols. (New York: Dodd, Mead and Co., 1905), 3: 92. For Haddon’s advertisement, see New York Gazette and Weekly Mercury, April 18, 1768. The carving from Barnet’s house is illustrated and discussed in Beckerdite, “Immigrant Carvers,” pp. 237-39.

New Jersey Historical Society, Calendar of New Jersey Wills, Administrations, etc., vol. 6 (Newark: New Jersey Historical Society, 1901), p. 111; Ancestry.com. New York, Estate Inventories and Accounts, 1666–1822, database on-line. Ancestry.com Operations, 2014. The accounting of Dwight’s estate was completed on April 26, 1788. Inventories and Accounts, 1666–1822, series J0301-82, microfilm, New York (State), Court of Probates, New York State Archives, Albany, New York.

Register of St. Phillip’s Parish, p. 282. Transcript of Charleston County, South Carolina, Wills, etc., 1756–1758, 84:54, Craftsman Files, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Winston-Salem, N.C.