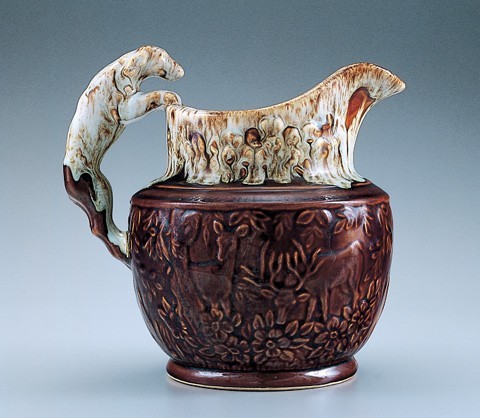

Hound-handle pitcher, Harker, Taylor & Co. East Liverpool, Ohio, 1847–1851. Rockingham glazed earthenware. H. 9 3/4". (All objects from the Arthur F. Goldberg collection; photos, Gavin Ashworth).

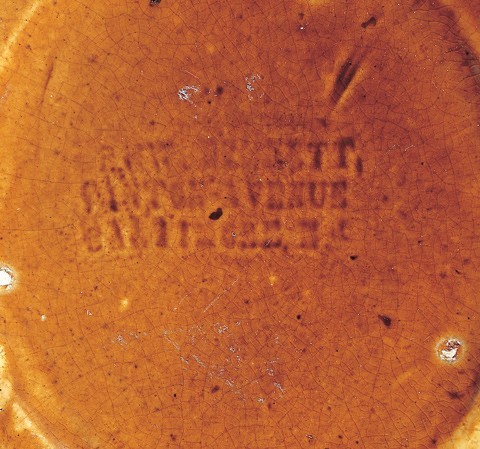

Detail of the Harker, Taylor & Co. mark on the bottom of the pitcher illustrated in fig. 1.

Hound-handle pitcher, East Liverpool, Ohio, ca. 1965. Rockingham glazed earthenware. H. 9 3/4". The upper portion and hound are covered with an off-white glaze. The impressed mark reads: “Reproduction Harker Rockingham/Mfg 1848/U.S.A. 1965.”

Octagonal paneled pitcher, attributed to Bennett & Brothers, East Liverpool, Ohio, or Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, ca. 1844. Rockingham glazed earthenware. H. 7 3/8". Powdered flint was added to the Rockingham glaze to produce the streaks of green and blue. A similar pitcher with a different Rockingham glaze is in the collection of the East Liverpool Museum of Ceramics, East Liverpool, Ohio.

“Boar and Stag Hunt” pitcher with hound handle, E. & W. Bennett, Baltimore, Maryland, 1850–1858. Rockingham glazed earthenware. H. 7 7/8".

“Boar and Stag Hunt” pitcher with hound handle, E. & W. Bennett, Baltimore, Maryland, 1850–1858. Rockingham glazed earthenware. H. 7 7/8".

Detail of the mark “E. & W. BENNETT/ CANTON AVENUE/ BALTIMORE, MD”. in large rectangle on the base of the pitcher illustrated in fig. 5. Two of the three stilt marks are visible.

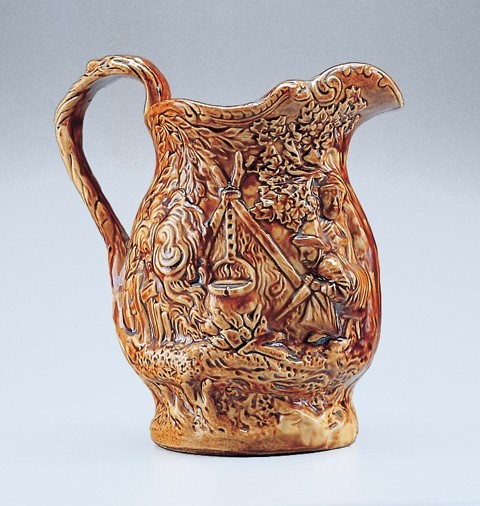

“Gypsy” pitcher, E. & W. Bennett, Baltimore, Maryland, 1850–1858. Rockingham glazed earthenware. H. 8 5/8". This pitcher has a modified branch handle with very crisp defined details. It is marked “E. & W. BENNETT/CANTON AVENUE/BALTIMORE, Md.” in small rectangle and has three stilt marks in a triangular pattern on the base.

“Gypsy” pitcher, E. & W. Bennett, Baltimore, Maryland, 1850–1858. Rockingham glazed earthenware. H. 8 5/8". This pitcher has a modified branch handle with very crisp defined details. It is marked “E. & W. BENNETT/CANTON AVENUE/BALTIMORE, Md.” in small rectangle and has three stilt marks in a triangular pattern on the base.

“Heron” pitcher, attributed to E. & W. Bennett, Baltimore, Maryland, 1850–1858. Rockingham glazed earthenware. H. 10". This is a molded covered ale pitcher with a branch handle.

Shaving mug, E. & W. Bennett, Baltimore, Maryland, 1850–1858. Rockingham glazed earthenware. H. 4 3/8". This molded mug has the image on both sides of Toby seated holding a razor in one hand with a mug in his other. It is marked “E. & W. BENNETT/CANTON AVENUE/BALTIMORE/ Md.” and has three stilt marks in a triangular pattern on the base.

Teapot, attributed to E. & W. Bennett, Baltimore, Maryland 1851–1857. Rockingham glazed earthenware. H. 10". This teapot has the molded inscription “REBEKAH AT THE WELL” on the front and a flower finial on the lid. Three spur marks in a triangular pattern are on the base.

Lion figure, attributed to Lyman, Fenton & Co., or United States Pottery Company, Bennington, Vermont, 1849–1858. Flint enamel earthenware. H. 9 1/2". The lion has a shredded clay mane and a protruding tongue.

Hound-handled pitcher, United States Pottery Company, Bennington, Vermont, 1852–1856. Rockingham glazed earthenware. H. 12 1/8". There are three stilt marks in a triangular pattern on the base.

Hound-handle pitcher, American Pottery Company, Jersey City, New Jersey, 1840–1845. Rockingham glazed stoneware. H. 9 1/4". This molded pitcher has double dipped brown glaze on its upper portion and a putty colored glaze inside. The neck and shoulder have an undulating vine with leaves, tendrils, and grape clusters. A scene of hounds attacking a stag is on one side and a boar being attacked by mastiffs is on the other.

Detail of the mark on the bottom of the pitcher illustrated in fig. 13.

Hound-handle pitcher, American Pottery Company, Jersey City, New Jersey, 1840–1850. Rockingham glazed stoneware. H. 8 1/2". This molded pitcher has a reddish brown glaze outside and a putty colored glaze inside. A vine with leaves, tendrils, and grape clusters is on its neck and shoulder.

Detail of the “AMERICAN POTTERY” mark on the collar band of hound-handle pitcher illustrated in fig. 15.

Pitcher, attributed to the American Pottery Co., Jersey City, New Jersey, ca. 1845. Rockingham glazed earthenware. H. 9 1/4". This molded pitcher is decorated with an elaborate design featuring gothic architecture and eight apostles. This example is unmarked although a similar pitcher with the American Pottery Co. mark is in the Clement Collection, Brooklyn Museum of Art.

Toby Philpott pitchers. Left: attributed to the Salamander Works, New York City or Woodbridge, New Jersey, 1837–1850s. Rockingham glazed stoneware. H. 13". This example has a reddish brown glaze, double dipped on its upper body, and a putty colored glaze inside. This form probably represents pattern J on the Salamander Works’ 1837 price list. Right: attributed to the American Pottery Company, Jersey City, New Jersey, 1840. Rockingham glazed stoneware. H. 9". This pitcher has a rustic branch handle and a reddish brown, putty colored glaze inside.

Hound-handle pitcher, attributed to Salamander Works, New York City or Woodbridge, New Jersey, 1837–1850s. Rockingham glazed stoneware. H. 11". A hunt scene of hounds attacking a stag is on one side and a boar being attacked by mastiffs is on the other. The pitcher has a leafy hop vine with flowers around the neck and a scalloped design around the shoulder.

Hound-handle pitcher, Salamander Works, New York City or Woodbridge, New Jersey, 1837–1850s. Rockingham glazed stoneware. H. 10". A hunt scene of hounds attacking a stag is on one side and a boar being attacked by mastiffs is on the other. The lower half of the pitcher is not glazed, and the interior is putty colored. The neck has a leafy hop vine with flowers, and the shoulder has a square scalloped fringe. The base is embossed “B2.” This pitcher is called the “Hound Pattern” on the Salamander Works’ 1837 price list.

Pitcher, Salamander Works, New York City or Woodbridge, New Jersey, 1837–1850s. Rockingham glazed stoneware. H. 11 1/2". This example is a reddish brown color with a putty colored glaze inside; an oak leafed branch with acorns is around its neck, a lotus leaf design on its shoulder, and its body surface is covered with elaborate parallel rhomboids surrounded by a delicate dot-like design simulating a pineapple. It has a branch handle and is embossed N1 on the base.

Covered pitcher, Swan Hill Pottery, Edward Hanks and Charles Fish, South Amboy, New Jersey, 1850–1852. Yellow ware. H. 11 7/8". This example has a strainer spout and an elaborate bifid branch handle with a branch finial on the lid.

Detail of the mark on the base of the yellow ware pitcher illustrated in fig. 22. It is impressed “SWAN HILL/POTTERY/SOUTH AMBOY.”

Hound-handle pitcher, possibly East Liverpool, Ohio, mid-nineteenth century. Rockingham glazed earthenware. H. 9 3/4". This eight sided pitcher has a molded eagle beneath its spout and is colored with a speckled blue flint glaze.

Pitcher, American, mid-nineteenth century. Rockingham glazed earthenware. H. 10". This molded pitcher has a hanging game scene and a branch shaped handle. Three stilt marks in a triangular pattern are on the base.

Presentation pitcher, attributed to John L. Rue and Company, 1870. Rockingham glazed earthenware. H. 9". The pitcher has a branch-shaped handle and a flint enamel glazed frog inside on the bottom. The name “D. REGAN” in raised white glazed letters is on the front with “Daniel Regan” and “August 3, 1870” incised on the base.

Presentation pitcher, probably South Amboy, New Jersey, 1860–1870. Rockingham glazed earthenware. H. 10". This pitcher may have been made by John L. Rue and Company, the Swan Hill Pottery, or a later firm copying their work. It has an elaborate filigree-like design around a circular medallion with a bearded man’s head. On the front, in white letters, is the name “MRS JOHN WEBB.” The inside has a white glaze and a molded Rockingham glazed frog on the bottom.

Teapot, attributed to John E. Jeffords and Company, Philadelphia, 1868–ca. 1876 and possibly later. Rockingham glazed earthenware. H. 9 3/4". A medallion of a woman’s head is on both sides.

Pitcher attributed to John E. Jeffords and Company, Philadelphia, 1868–ca. 1876 and possibly later. Rockingham glazed earthenware. H. 8". A medallion of a woman’s head is on both sides.

Pitcher, American, mid- nineteenth century. Rockingham glazed earthenware. H. 11 1/8".

Cake mold, American, mid- nineteenth century. Rockingham glazed earthenware. D. 10".

Spittoon, Harker, Taylor & Company, East Liverpool, Ohio, ca. 1852. Rockingham glazed earthenware. D. 8 1/2". Impressed mark on base: “ETRURIA WORKS/EAST LIVERPOOL” in circle with “1852” in center.

Candlestick, Lyman, Fenton & Co. / United States Pottery Company, Bennington, Vermont, 1849–1858. Rockingham glazed earthenware. H. 9 3/8". Flint enamel was added to the glaze.

Figures probably by W. H. Farrar, Geddes (Syracuse), New York, ca. 1840–1857, or made in Lyons, New York, by Nathan Clark or Thompson Harrington in the 1850s. Rockingham glazed molded earthenware H. 9 7/8" and 10 1/4". These unmarked figures have a quarter inch central hole in the base.

Yellow and Rockingham ware potteries were established in the United States primarily by Staffordshire potters who learned their trade before immigrating to America. Many were master potters and modelers, whose serviceable wares were widely used throughout the United States for the better part of the nineteenth century. These immigrants faced serious challenges, as there were fires that burned down their works; shortages of clay, mineral components, and labor; and financial difficulties. Some failed economically; others rebuilt their potteries, joined different potteries locally, or moved elsewhere.

The story of these potters and their potteries represents the history of an American industry led by a small number of intelligent, creative, hard working, and skillful individuals. Most significantly, their newly adopted country provided an environment of freedom and opportunity that encouraged the expression of their entrepreneurial spirit. Raw materials, transportation facilities, and markets were available, and the potters became successful and secure in their new lives. When Rockingham and yellow ware were no longer popular or economically viable, substitutions became necessary for survival, a necessity that eventually led to the growth of the whiteware and porcelain industries.

The American Pottery Company of Jersey City, New Jersey, was the initial employer of a number of potters when they emigrated from England beginning in 1828. Some of these early potters later moved on to make significant contributions to the American ceramic industry. Daniel Greatbach worked in Bennington, Vermont, and Peoria, Illinois; James Bennett in East Liverpool, Ohio; James Taylor and William Bloor in East Liverpool and Trenton, New Jersey; Charles Coxon in Baltimore, Maryland, and South Amboy, New Jersey; Thomas Locker and James Carr in South Amboy and New York City.[1]

Before discussing the more important potters and potteries of the period and their east-west association, however, a definition of Rockingham and yellow ware is in order. The name Rockingham was first used for a late-eighteenth-century, dark brown glaze created at the Swindon works in Yorkshire, England, on the estate of the Marquis of Rockingham.[2] Ever since, the glaze, with slight variations, has been copied by both English and American potteries. Somewhat confusingly, later Swindon potteries made an excellent porcelain which was also called Rockingham. Later on in the United States, the term was applied to yellow earthenware that, covered with a similar colored glaze, constituted a major generic group.

Although the Americans applied the glaze in a uniform overall fashion like the English, their techniques varied in many ways, including the amount of glaze used and the contrasting patterns employed to create something new and beautiful. The glaze was dabbed, spattered, or dripped in long, spreading streaks down the vessel’s side. Thinner coatings produced shadows outlining the molded designs and highlights to contrast or reveal the underlying yellow clay. Also attractive was the application of the glaze in a random pattern. In addition, some potteries used different metallic oxides in the glazing process, enhancing the overall appearance with variegated colors. This pottery is often referred to as flint enamel ware.

The term Rockingham has been equally applied to stoneware using the same glaze. Various potteries modified the glaze formulas creating different shades of brown, some with a reddish tint. Stoneware was almost always uniformly glazed, and some vessels were embellished with a double dip.

Just as there had been an earlier craze for glossy, black Jackfield-type ware and black basalts, the Rockingham glaze also stimulated the imagination of the potters and captivated America’s public taste for more than three-quarters of a century. Brown had become beautiful, and brown ware had become fashionable.

Yellow ware is earthenware made from native yellow clay. The potteries produced utilitarian wares—baking dishes, pie plates, bowls, custard cups, milk pans, cake molds, soap dishes, pitchers, chamber pots, and bedpans—for households. The yellow ware was covered with a clear, lead-based glaze allowing the underlying clay to show through.

In contrast, two methods were used for applying the Rockingham glaze to these earthenware and stoneware forms. In the first, potters air-dried the green ware, applied the Rockingham glaze all over uniformly, and then fired the vessel in the kiln. In the second, the green ware was bisque fired, immersed in an underglaze, and air-dried, producing a glossy film. The Rockingham glaze was then applied and refired.[3]

At the appropriate temperature, the glaze, consisting of silica in combination with a flux and metallic oxide, vitrified and fused to the ceramic surface (glost firing). Adding more manganese or iron to the Rockingham glaze would darken its brown color to black. Earthenware was fired to about 1200 degrees centigrade; stoneware, from about 1200 degrees to 1300 degrees centigrade. Determining the chosen method is as easy as examining the pottery’s base. The second method deposited a shiny coating of underglaze, absent in the first process. The second firing method produced wares of exceptional quality; the resulting glaze was a brilliant, lustrous brown having great transparency. Until replaced by whiteware, these Rockingham glazed earthenwares and stonewares became the most popular American wares during the mid-nineteenth century.

In America, the popularity and availability of English ceramics was widespread. It was believed that pottery was more marketable if made in the English fashion. Along with the expertise of these immigrant Staffordshire potters, a permissive intellectual and moral climate and lax copyright laws allowed American potteries to literally pirate another potter’s design.

East Liverpool

East Liverpool, Ohio, was the major center for the production of Rockingham and yellow ware during the 1840 and 1850s.[4] In fact it was in East Liverpool that James Bennett created the first American Rockingham ware. Some of the potters working there later left to establish their own businesses in Trenton, New Jersey, and Baltimore, Maryland. Others had links with Jersey City and South Amboy, New Jersey, and Bennington, Vermont.[5] As a result of this close relationship, the midwestern and eastern potteries laid the foundation for the development of Rockingham and yellow ware manufacture.

The genesis for the American production of this ware began when master potter James Bennett left Derbyshire, England, for America in 1834. He initially worked for D. & J. Henderson at the American Pottery Company in Jersey City, New Jersey, but in 1837 he moved to Troy, Indiana, to work with the famous Staffordshire potter James Clews. In 1839 he established his own pottery in East Liverpool, Ohio, with his younger brother, Edwin, and two other brothers who joined him in 1841. Their partnership, called Bennett Brothers, made the first Rockingham and yellow ware in the United States.

In 1842 Englishman Benjamin Harker, Sr., although not a potter, created East Liverpool’s second pottery for the manufacture of Rockingham and yellow ware. The business failed until James Taylor, who had previously worked at the American Pottery Co., joined the firm, forming Harker, Taylor & Company (1847 to 1850), also called Etruria after Josiah Wedgwood’s works in Staffordshire.[6]

The company’s most noted ceramic piece was an unusual and large, hound-handled pitcher, circa 1847–1851 (figs. 1, 2). Although slight changes were made, the pottery copied the earlier New Jersey Boar and Stag Hunt pitcher made by the American Pottery Company and the Salamander Works. About 1965 the Harker Pottery Company, a derivative enterprise, manufactured a Rockingham semivitreous reproduction. Although advertised as an authentic reproduction of the original pitcher, it was not. Besides adding an off-white glaze over the hound and the vessel’s upper portion, the violent scenes on its sides were replaced to show stags and does grazing in a peaceful, bucolic forest. The transformed images indicate a changing cultural climate, superseded by political correctness (fig. 3).[7]

Two other East Liverpool potteries of the period deserve mention. Jabez Vodrey, a Staffordshire potter, immigrated to the United States in 1827, operated a pottery in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, later worked in Louisville, Kentucky, and in 1839 took charge of James Clews’ Indiana Pottery Company. Clews, a Staffordshire potter, had left his English works and moved to Troy, Indiana, in 1837. He hoped to produce fine whiteware like the English, but was unsuccessful. As a substitute, Clewes made Rockingham and yellow ware. Vodrey added different metal oxides to his glaze, producing multiple colors.

Because local problems developed while Vodrey was in Indiana, he moved to East Liverpool, where in 1848, with the help of financial backers, he established his own successful Rockingham and yellow ware pottery. Although a fire destroyed his small enterprise, Vodrey rebuilt it and symbolically renamed it the Phoenix Pottery. By 1852 the company had grown to five buildings, three large kilns, and about seventy-five employees. The Phoenix Pottery was one of the largest potteries in East Liverpool, manufacturing some of the finest quality ware.[8]

John Goodwin emigrated from Burslem, England, in 1842 and initially worked for Bennett and Harker in East Liverpool. In 1844 he formed his own very successful Eagle Pottery making an extensive line of Rockingham and yellow ware (1844–1853). After a ten-year hiatus, he started another pottery but left in 1870 to purchase an interest in the Trenton Pottery Company, which manufactured ironstone and sanitary ware.[9]

Baltimore

In 1844 Edwin Bennett left East Liverpool and moved to Birmingham (Pittsburgh), Pennsylvania, with three other brothers (fig. 4). Shortly after, in 1847, Edwin and his brother William formed their own pottery, E. & W. Bennett, in Baltimore, Maryland. Their modeler, master potter Charles Coxon (1850–1858), designed a number of fine ceramic pieces, among them his Boar and Stag Hunt, Gypsy, and Heron pitchers, and a Toby shaving mug.[10]

The relief on the Boar and Stag Hunt pitcher contrasts two compelling images: violent and grisly hunt scenes against lushly encompassing, grape-clustered vines (figs. 5, 6). A similar pitcher was first made in stoneware by Phillips & Bagster of Hanley, England, about 1840, and was essentially duplicated by both the American Pottery Company and the Salamander Works of New Jersey in the 1840s and 1850s. With slight variations, especially of the hound handle, it was copied—in both Rockingham ware and stoneware—by many others including, most particularly, potteries in New York State and New England. Hunting pitchers have had a long tradition in England and America and were popular, judging from the number of extant pitchers. Coxon’s pitcher was copied by John Bell of Waynesboro, Pennsylvania, and Solomon Bell of Strasburg, Virginia (1845–1880).[11]

The Gypsy pitcher shows a panorama of life on the road (fig. 7). Its prototype was made in 1842 by James Walley and Samuel Alcock in England, and is almost an exact match with Coxon’s design. To date, there is no documentation that Coxon designed his version of this pitcher before arriving in Baltimore.

An original Coxon design is his Rockingham-glazed, Heron ale pitcher. This pitcher incorporates long-billed, long-legged herons posed against a backdrop of tall reeds and cattails on both sides. The naturalistic imagery is further embellished with an entwining snake, the head of a boar, and a broad band of oak branches. The cover, with acorn finial, is similarly decorated. To date, no marked Heron pitcher has been found (fig. 8).

The Rockingham-glazed shaving mug with a branch handle was designed in the English manner and with the characteristic image of Toby on both sides but without his traditional ale pitcher and mug (fig. 9). The overall design is remarkably similar to the flint enamel Toby snuff jars made in Bennington, Vermont, marked “Lyman, Fenton & Co.’s Fenton’s Enamel 1849.”[12]

Potter Edward Bennett claimed that he designed his most popular vessel, the Rebekah-at-the-Well teapot (fig. 10) about 1850. This assertion has been challenged by the suggestion that it was actually designed and modeled by his chief modeler, Charles Coxon. Regardless of who claims credit, the prototype for the teapot was a covered ewer made by the English pottery of Samuel Alcock and Company, circa 1847. Coxon left Bennett and moved to South Amboy, New Jersey, to run the Swan Hill Pottery (1858–1860), which manufactured Rockingham and yellow ware. In 1863 he established his own pottery, Coxon & Co., in Trenton, New Jersey.[13]

The Rebekah-at-the-Well teapot became so popular that it was copied by many American potteries, and was still in production at the Bennett pottery (although with different glazes) into the mid-1930s. Other companies modified the design, using less detail and modeling definition, as well as different Rockingham glaze shades and techniques. These copies never achieved the beauty and quality of those made in the early production of E. & W. Bennett.

All of the Bennett pieces exhibit characteristic coloring and glazing. The Rockingham glaze achieved its greatest beauty when it was lightly applied over the molded decorations leaving thin highlights on the low relief design, exposing the yellow clay. The relief outline and deeper grooves, pooled with additional glaze, delineated the design.

Besides the lustrous surface colored with shades of light and dark brown, the beauty of the overall glazing is its clarity, brilliant sheen, and transparency. No glazed vessel is alike due to the innumerable random applications of the glazes and the way they flow down the vessel’s surface to reveal and contrast with the clay. Nevertheless, in spite of variations, there is an overall balance and harmony between the glaze and clay body. Bennett produced some of the finest designs, modeling, and Rockingham glazes.

Bennington

During the period that Ohio potteries were developing, there was similar activity in New England. Christopher Webber Fenton joined the older Norton Pottery (established in 1793) in Bennington, Vermont, about 1839. In 1847, along with salt-glazed stoneware production, the first parian ware in the United States was made just two years after it was produced by W. T. Copeland in England. The Norton and Fenton firm was dissolved in 1847.[14]

About 1848 or 1849, Fenton created a new enterprise called Lyman, Fenton & Co., producing some of the finest American Rockingham ware marked “Fenton’s Enamel, Patented 1849.” The ware had a brilliant glaze with variegated colors of yellow, orange, blue, green, olive, brown, and red. The company’s name later changed to the United States Pottery Company, and primarily concentrated on parian ware and porcelain until 1858, when it closed for economic reasons. Initially its biscuit wares were covered with a transparent glaze. Later, the surface was sprinkled with various metallic oxides in amounts designed to produce different color intensities, yet leaving some openings for the clay to show through. The pottery was then glazed and refired. During the firing, the oxides melted fusing to the glaze in an abstract, flowing, or spotted pattern.[15]

Some have used the English terms, “Whieldon” or “tortoise shell,” to describe the American flint enamel ware. Thomas Whieldon (1740–1780) splattered metallic oxides on some of his earthenwares to create a mottled color effect. With the exception of flowing, variegated colors, the two were aesthetically different. One of the finest examples of this ware was a sculptural lion, believed to have been designed by modeler Daniel Greatbach, a major achievement of American ceramic production for the time (fig. 11).[16]

Stimulated by the reports of travelers taking the Grand Tour in Italy and the growing awareness of classical antiquities, many Staffordshire potters made ceramic lions. In particular, they were inspired by a pair of marble lions at the entrance to the stairs of the Loggia de Lanzi in Florence, Italy.[17] The Bennington Pottery modified earlier English ceramic designs using shredded clay, called “coleslaw,” to create a realistic, and charming, lion’s mane.

Brown-glazed earthenware, called dark lusterware, was also made. One example is the popular hound-handled pitcher designed and modeled by Daniel Greatbach. With some variation, this pitcher is similar to the one he designed for the American Pottery Company (fig. 12). To date, no marked pitcher has been found.

New Jersey

After purchasing the short-lived Jersey Porcelain and Earthenware Company in 1828, Scotsman David Henderson and his brother established a successful pottery using Staffordshire mold-making techniques to manufacture stoneware, Rockingham, and yellow wares. As a result, he revolutionized the American pottery industry by transforming the production of hand-turned pottery to a factory production system, and at prices competitive with imported wares. In 1833 their name changed from D. & J. Henderson Flint Stoneware Manufactory to the American Pottery Manufacturing Company, or the American Pottery Company, about 1840. Henderson’s pottery also played an important role in the formative years of the American pottery industry, employing immigrant Staffordshire potters when they first arrived in the United States. A number of them learned his methods and went on to establish important and successful potteries elsewhere.[18]

A very important figure in American pottery design during this period was Daniel Greatbach. Like his grandfather William Greatbach, who worked for Thomas Whieldon and Josiah Wedgwood, Daniel was a skillful modeler and a designer. In 1838 the younger Greatbach emigrated from Staffordshire to work for David Henderson’s American Pottery Company of Jersey City, New Jersey.

Around 1828, D. & J. Henderson obtained an original mold belonging to the English firm of Phillips and Bagster, and reproduced its version of a hound-handle hunt pitcher about 1828. Greatbach redesigned the Phillips and Bagster pitcher and also created many other original ceramic forms. For the next ten years, he designed and modeled a number of important pieces, including many Toby pitchers.[19]

The hound-handle hunt pitcher and other wares are high quality items, with exquisite modeling and an elaborate, inventive vocabulary of decorative designs (figs. 13-16). The skillful modeling and manufacturing techniques produced a product with crisp details. As well, the hound-handle pitchers have a strong sculptural image; the proportional open space between the hound and vessel body enhance their three-dimensional form. Their brown Rockingham glaze is rich and lustrous, and the smaller pitcher has a reddish hue. In areas where the glaze is thin, the underlying clay highlights the surface design. Greatbach’s contemporaries recognized the pitcher’s outstanding design, and it became so popular that it was copied by many potteries for years to come.[20]

Interest in the Gothic Revival is represented by another Rockingham glazed pitcher that Greatbach designed for the American Pottery Company. Except for some simplifications and added decoration, it is a copy of the “Apostle Pitcher,” a stoneware jug made by Charles Meigh of Hanley, England, in 1842. A gothic arcade and a canopy with eight sections, each containing a standing apostle, surrounds the pitcher’s body. Further decoration includes a dictionary of other gothic architectural motifs, from fine tracery to ornamental finials to pointed arches and satyr heads in place of gargoyles. In spite of its complexity, the dynamic interplay of individual parts unifies the design (fig. 17).[21]

In 1852 Greatbach left New Jersey for Bennington, Vermont, to work for Christopher Webber Fenton’s United States Pottery Company. There he designed their hound-handle pitchers along with many other ceramics. Later, he put in a short stint at the Swan Hill Pottery (1840–1875) in South Amboy, New Jersey, where he ran the pottery with Samuel Riley from 1856 to 1857. When Bennington’s United States Pottery closed in 1858, Greatbach joined Christopher Fenton and Decius Clark, his superintendent in Peoria, Illinois, to found the American Pottery Company. There, as at Bennington, Greatbach was chief designer and mold maker. In 1865 the enterprise failed and he moved to Trenton, New Jersey, where he eventually died in poverty.[22]

Another pottery, the Salamander Works, was making stoneware in New York City from about 1835 to 1839 or 1840 when it relocated to Woodbridge, New Jersey, and continued to make similar wares. Salamanders’ stoneware production changed to industrial items around 1857, although an exact date is not known. M. Lelyn Branin believed that their high point was the late 1830s to the 1840s and continued into the 1850s. Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen cites the active dates of the pottery as 1836–1855. She further illustrates stoneware examples in her article made circa 1837 to 1842 or 1845. Both Branin and Frelinghuysen recognized the production of stoneware in New York City before going to Woodbridge, New Jersey. Frelinghuysen correctly lists the stoneware illustrated in her section as Salamander Works, New York City or Woodbridge, New Jersey.[23]

Earlier authors believed that all Salamander Works pieces were made in Woodbridge, dismissing pieces marked New York and the 54 Cannon St., New York City address as representing only their sales office and not the site of ceramic production. There are two known hound-handle pitchers with the inscription “Salamander Works/Woodbridge/N.J.” on their bases.[24]

The Salamander Works received a diploma in 1835 from the American Institute of the City of New York for “a fine specimen of flint stoneware.” The following year they received another diploma at the Ninth Annual Fair for “a beautiful specimen of stoneware.” The judges noted that their ware “of all descriptions, [was] not to be surpassed by other manufacturers, either in America or abroad.” Silver medals were also awarded in 1838 and 1839.

An 1837 illustrated handbill showing pottery being made at Salamander Works in New York City helps identify existing ceramics. A sign of a major enterprise, it lists forty-five different items, many in multiple sizes. Besides fourteen different pitcher patterns, there were coffee and teapots, washbasins, water ewers, chamber pots, bed and foot pans, spittoons, table and kitchenware, spitting cups, inkstands, and toys.[25]Today, only about a dozen different items are known. Pitchers are the most common.

The imposing pitcher shown on the left in figure 18 was made by the Salamander Works of New York City or Woodbridge, New Jersey.[26] It is a commanding sculptural piece and is taller than its English counterparts, which usually measure nine to ten inches in height. This pitcher corresponds to what is called the Ordinary English Toby and was copied from this prototype. The tricorn hat makes an excellent pouring spout. The mold details are crisp and exquisite, from the fine details of the teeth, eyes, furrowed brow, crow’s feet, and fingernails to the knotted bow on the breeches and shoes.

A contrasting Toby pitcher was made by the American Pottery Company of Jersey City, New Jersey, also about 1840 to 1850 (fig. 18). Here is a new American form designed and modeled by Daniel Greatbach. Atypically, Toby is not seated, and the jolly tippler motif is absent. Similar fine modeling is present, exemplified by the lace blouse and the vertical design lines on the pipe bowl. The pooling effects of the Rockingham glaze enhance the beauty of the piece and accentuate the deeper modeling lines, creating a more three-dimensional figure.

Figures 19 and 20 represent two other examples of Salamander’s hound-handle pitchers. As competitors to the American Pottery Company, the Salamander Works recognized a popular form and design, and acted to capitalize on it. With the exception of a few minor changes, they copied the original Phillips and Bagster pitcher. However, they did appropriate Greatbach’s hound, although adding more details. Both pitchers are handsome examples, each having different colored lustrous glazes. The hops in the neck design suggest the pitchers were used to hold beer.

It is often difficult to distinguish unmarked, hound-handle hunt pitchers made by the American Pottery Company and Salamander Works based solely on their exterior and interior glazes. A simple and quickly discernable sign for differentiating between the two is Salamander’s inclusion of one to three incised lines, indicating digits, on the back of the hound’s paws. In addition, the ears of the hound on Salamander Works pitchers have multiple folds, whereas the ears of the hound on American Pottery Company pitchers are simpler. Close examination reveals further differences.

1. Both potteries tried to cover the seam of the two-part body mold with a tree. On the Salamander pitcher it is fully leaved with branches obscuring the seam. The tree’s short trunk is on a mound of earth with no brush on either side. In contrast, the American Pottery Company pitcher has a tall trunk over the seam, considerably fewer leaves on top, no earth mound, and usually has large leaved brush at either side. Usually in the rear below the hound handle is a tree over the seam similar to the one in front of the Salamander pitcher. In the American Pottery version, there is no tree and the seam is visible.

2. On the Salamander Works pitcher, the deer’s head points upward and its antlers terminate in a five pointed star formation. On the American Pottery Company pitcher the deer turns laterally and its longest antler has a bifid end.

3. The dogs on the Salamander Works pitcher are far behind the central hound, whereas those on the American Pottery Company pitcher are closer.

4. The fox hiding in the foreground brush of the Salamander Works pitcher has no tail, whereas the one on the American Pottery Company pitcher has a long tail.

5. There is a prominent dog’s head peering at the fox to its right on the Salamander Works pitcher. The dog’s head is barely visible on the American Pottery Company example.

6. The left forelimb of the central mastiff is outstretched and clearly visible on the Salamander Works pitcher. It is partially seen below the dog’s head on the American Pottery Company pitcher.

7. The small mastiff attacking the rabbit on the Salamander Works pitcher has long ears, whereas the one on the American Pottery Company pitcher has small ears.

8. Leafy foliage extends across the middle of the central mastiff on the Salamander Works pitcher, whereas a tree trunk extends across the middle of the dog on the American Pottery Company pitcher.

9. There are other details separating the two pitchers—from the width of the hound’s collar and variations in the forest floor foliage to tree and leaf designs in the open spaces as well as the detailed treatment of leaf clusters.

If a pitcher has white glazed letters spelling a dedicated name on its shoulders, those of the Salamander Works are smaller whereas the American Pottery letters are much larger, filling most of the width of the shoulders’ rim.

One particularly distinctive stoneware pitcher from the Salamander Works is unlike any other design made at that time (fig. 21). It has complex, finely molded details with a broad, rustic-branch handle enhancing its overall sculpted form. The embossed “N1” on its base identifies its maker and represents a non-titled pattern in the 1837 Salamander Works bill head. The design, simulating a pineapple, emulates a prototype from eighteenth-century Staffordshire wares.

Some of the finest American yellow ware was made during the earliest manufacturing period, as was this one from the Swan Hill Pottery of Hanks and Fish of South Amboy, New Jersey (1850–1852). An elaborate yellow ware ale pitcher (figs. 22, 23) shows a bold, bifid branch handle extending across its body. Its cover is embellished with a grape and vine design, all the details delicately sculpted. The beauty of the pitcher’s low relief design is best appreciated in raking light, which creates shadowing that outlines the sculptural surface and delineates its three dimensionality. The naturalistic design of the pitcher was an inventive form, free from English influence, and introducing a strainer at the spout. This pitcher was also made with a Rockingham glaze.[27]

Hanging-game pitchers were a popular subject. Figure 24 shows an elaborate eight-paneled example with a hound handle and a Rockingham, flint enamel glaze. An eagle postures below its spout, and suspended from its sides are ducks, rabbits, boars, and stags—all animals that were hunted in the countryside. Another example features suspended pheasants, deer, and rabbits. To hide the mold line, an expansive tree trunk covers both the front and rear seams. The pitcher’s branch handle cleverly rises from the trunk (fig. 25).

A molded Rockingham presentation pitcher with a colored enamel frog inside was made by the potter Daniel Regan while he was working at John L. Rue and Company, one of the successors to the Swan Hill Pottery (1860– ca. 1871) (fig. 26). On one side of this pitcher are two mounted hunters and on the other a confrontation between the proverbial (and violent) stag and hounds. Charles Coxon first designed this piece while working at Bennett’s Baltimore Pottery (1851–1858), and later reproduced it when he ran the Swan Hill Pottery (1858–1860). It continued to be made for many years after.[28]

Dedicated to Mrs. John Webb, yet another Rockingham frog presentation pitcher created a new, elaborate American design with the addition of a central medallion, and is attributed to the Swan Hill Pottery, South Amboy, New Jersey (fig. 27). Somewhat similar designs were also made at the John E. Jeffords and Company of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: one, a teapot (fig. 28), and the other, a pitcher (fig. 29), both with beautiful Rockingham glazes.[29]

In 1852 potters James Taylor and Henry Speeler moved to Trenton, New Jersey, to form the first factory making white ironstone dinnerware. They primarily made Rockingham ware, porcelain, Queensware, and stoneware. In 1855 English potter William H. Bloor joined them. Earlier, Bloor had worked at the D. & J. Henderson Pottery in Jersey City, and in 1849 he was making Rockingham and yellow ware with William Brunt, Sr., in his East Liverpool pottery.[30]

Bloor worked in Trenton until 1859 and then returned to East Liverpool, where he purchased part of the Phoenix Pottery and made the city’s first ironstone ware, as well as Rockingham and yellow ware. By 1861 he had established the East Liverpool Porcelain works, making fine porcelain and parian ware, another first for the region. Because of financial difficulties and loss of labor to the Civil War effort, Bloor was forced to sell his pottery in 1862. Returning to Trenton in 1863, he joined in partnership with Joseph Ott and Thomas Booth under the name of Bloor, Ott, and Booth, also called the Etruria Pottery Works. This firm was the forerunner of the renowned firm of Ott and Brewer, which continued to produce some of the finest porcelain and parian ware in the United States. Bloor’s role and achievement in both East Liverpool and Trenton established him as one of the major pioneers in the American ceramic industry.[31]

The Rockinghan Aesthetic

Besides its different glaze application, Rockingham ware displays a quality and variety of molded designs, from low relief with intricate modeling or rounded smooth edges to the fine detailing of delicately carved grapes, the underside of a leaf, wavy hair, or a wrinkled brow. All of these complexly designed vessels, to one degree or another, present their own aesthetic. However, there are many Rockingham glazed utilitarian vessels that do not have a sculptural surface embellishment. Others achieve great beauty beyond their useful value.

An example of this is a pitcher (fig. 30) that displays a long, graceful neck extending from an eight-paneled body. Its overall form is narrow, not globular, and has the appearance of a vase. The lip and rim have a gentle curve and a delicate dentilated edge. The handle, long, narrow, and slightly curved, accentuates its height. Independent of the shape, the vertical, flowing lines of Rockingham glaze acts to unify the overall design and accentuate its form. Its translucent glistening brown glaze contrasting with the underlying yellow clay adds to its beauty, singularly dependent on form and glaze.

Another example is a cake mold enhanced by a lustrous glaze (fig. 31) that arrests the viewer with its overall shape and blended colors. The gently swirled and fluted interior is accentuated by intense glaze pooling in its lower portion and up its central fluted column. One could not ask for a more translucent lustrous glaze, its tonalities of brown contrasted in more thinly applied areas with the underlying yellow clay.

Spittoons were a common product, a logical byproduct for the widespread habit of chewing and spitting tobacco. An early Rockingham example made by Harker, Taylor & Company’s Etruria Pottery (1847–1850) in East Liverpool is illustrated in figure 32. Conversely, a rare ceramic form, a flint enamel glazed candlestick made in Bennington about 1850 is pictured in figure 33.[32]

During the mid-nineteenth century, few people owned sculptural figurines like the Scottish lad and lassie illustrated in figure 34. Made of Rockingham-glazed yellow ware, this pair was inspired by similar Staffordshire examples. The quality of the mold shows in its detail—the young couple’s facial features, fringes on dress, plumed feathers, the lamb’s wool, and bag pipes, which, in some examples, are obscured by a thick glaze.[33]

Some yellow ware figures were also colored with a darker brown or a mottled glaze; others, made of stoneware, were salt glazed with highlights of cobalt blue. A broad line of utilitarian Rockingham and yellow earthenware, as well as stoneware, was also in production at a number of potteries in upstate New York and other parts of the country.

By the 1840s and 1850s, potteries had grown in size, numbers, efficiency, and industrialization. More modern mass production methods were introduced, and potteries were able to meet the demands of growing markets. As the popularity of Rockingham and yellow ware declined, the potteries were able to compensate by introducing new utilitarian products: whitewares for home table use, hotel china, and sanitary wares. American potteries were on their way to produce wares economically competitive with English manufactories. Later, fine porcelain art pottery and parian wares were made. Credit for this is largely due to the infusion of experienced immigrant potters primarily from Staffordshire and a few from elsewhere. As a result, major pottery centers were created in East Liverpool, Trenton, Jersey City, Woodbridge, Baltimore, and Bennington.

James Carr, who was born in England, worked at the American Pottery Company from 1844 to 1852. He left to rent Charles Fish’s Swan Hill Pottery at South Amboy and worked there with Thomas Locker and Joseph Wooten until 1853 making yellow, Rockingham and whiteware until 1853. One of their billheads is illustrated in both M. Lelyn Branin, The Early Makers of Handcrafted Earthenware and Stoneware in Central and Southern New Jersey (Cranbury, N.J.: Associated University Presses, 1988), p. 200, and Joan Liebowitz, Yellow Ware (Atglen, Pa.: Schiffer, 1993), p. 33. Carr subsequently moved to New York City where he formed the New York City Pottery, initially making opaque china, while later making granite and majolica and then excellent bone china and parian ware. See Edwin Atlee Barber, The Pottery and Porcelain of the United States (1893 and 1909; reprint, New York: Feingold and Lewis, 1979), pp. 179–80. Branin, The Early Makers of Handcrafted Earthenware and Stoneware, p. 198, and Arthur W. Clement, Notes on American Ceramics, 1607–1943 (New York: Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, 1944), p. 19, have Carr working at South Amboy until 1855. Thomas Locker continued to work at the Swan Hill Pottery after Carr’s departure. See Branin, The Early Makers of Handcrafted Earthenware and Stoneware, p. 99.

Arthur A. Eaglestone and T. A. Lockett, The Rockingham Pottery, new revised ed. (Rutland, Vt., and Tokyo, Japan: Charles E. Tuttle Company, Inc., 1973), pp. 89, 90; Frederick Litchfield, Pottery and Porcelain: A Guide to Collectors (New York: M. Barrows and Company, Inc., 1951), p. 217; Lura Woodside Watkins, Early New England Potters and Their Wares (1950; reprint, Hamden, Conn.: Archon Books, 1968), pp. 7, 212; Richard Carter Barret, Bennington Pottery and Porcelain: A Guide to Identification (New York: Crown Publishers, 1958), pp. 18, 19.

John Spargo, The Potters and Potteries of Bennington (1926; reprint, New York: Dover Publications, 1972), pp. 172, 173.

Not to be overlooked as well is the origin of utilitarian, salt-glazed stoneware manufacture, which was simultaneously made in the Midwest. Those potters working in Indiana were also primarily English, with only a small percentage from Germany. By 1840 at least twenty-three potters operated in Illinois making stoneware. The most famous were the Kirkpatrick family potteries established in 1836. See Eva Dodge Mounce, “Checklist of Illinois Potters and Potteries,” Historic Illinois Potteries 1, no. 3 (1989), p. 3.

William C. Gates and Dana E. Ormerod, “The East Liverpool, Ohio Pottery District; Identification of Manufacturers and Marks,” Historical Archaeology: Journal of the Society for Historical Archaeology 16, nos. 1–2 (1975): 15; Barber, The Pottery and Porcelain of the United States, pp. 192–96; Edwin Atlee Barber, Marks of American Potters (1904; reprint, New York: Feingold and Lewis, 1976), p. 143; Eugenia Calvert Holland, Edwin Bennett and the Products of His Baltimore Pottery (Baltimore, Md.: The Maryland Historical Society, 1973), p. 2.

Gates and Ormerod, “The East Liverpool, Ohio Pottery District,” p. 79; Barber, The Pottery and Porcelain of the United States, p. 199; Barber, Marks of American Potters, p. 105.

Their advertising sheet states it was made by the Harker China Company/The Oldest Pottery in America/Established 1840 as an “authentic reproduction of the first Harker Rockingham Hound Handled 2 Qt. Jug, produced in 1948.” They also created a hound-handle mug similarly glazed and a “Rebekah-at-the-Well” teapot with an overall dark brown glaze.

Gates and Ormerod, “The East Liverpool, Ohio Pottery District,” p. 300; Barber, The Pottery and Porcelain of the United States, p. 199; Barber, Marks of American Potters, pp. 160, 161, 201. An 1864–1865 price list of the Vodrey Pottery Works of his Rockingham and varigated ware and yellow ware is illustrated in Joan Liebowitz, Yellow Ware (West Chester: Pa.: Schiffer, 1993), p. 45.

Gates and Ormerod, “The East Liverpool, Ohio Pottery District,” p. 52; Barber, The Pottery and Porcelain of the United States, p. 200. An 1850 price list of his yellow and Rockingham ware is illustrated in Liebowitz, Yellow Ware, p. 43.

Holland, Edwin Bennett and the Products of His Baltimore Pottery, pp. 2–13. David Goldberg, “Charles Coxon, Nineteenth Century Potter, Modeler-Designer and Manufacturer,” American Ceramic Circle Journal 9 (1994): pp. 28–64.

H. E. Comstock, The Pottery of the Shenandoah Valley Region (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, 1994), p. 122, fig. 4.117, p. 220, figs. 8.62–8.64.

Barret, Bennington Pottery and Porcelain: A Guide to Identification, p. 320, pl. 417, p. 321, pl. 418. John Bell also copied this mug (see Comstock, The Pottery of the Shenandoah Valley Region, p. 130, fig. 4.143). Coxon continued to make this mug with slight variations when he was at the Swan Hill Pottery, ca. 1858–1860.

Gary Stradling, “Puzzling Aspects of the Most Popular Piece of American Pottery Ever Made,” Antiques 151, no. 2 (1997): 332–37; Goldberg, “Charles Coxon,” pp. 30, 31, 37–43. Branin, The Early Makers of Handcrafted Earthenware and Stoneware, p. 202; Goldberg, “Charles Coxon,” pp. 59, 60.

Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen, “Empire City Entrepreneurs: Ceramic and Glazes in New York,” in Art and the Empire City, New York 1825–1861, edited by Catherine Hoover Voorsanger and John K. Howat (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2000), pp. 136, 142; Watkins, Early New England Potters and Their Wares, p. 212.

John Spargo, Early American Pottery and China (New York: The Century Co., 1926), p. 317; Watkins, Early New England Potters and Their Wares, pp. 211–13.

Spargo, Early American Pottery and China, p. 306; Spargo, The Potters and Potteries of Bennington, pp. 180–84; Watkins, Early New England Potters and Their Wares, p. 218.

I am grateful to Leslie B. Grigsby for this citation and for sending me photographs of examples of early Staffordshire earthenware lions from her book The Henry H. Weldon Collection, English Pottery, Stoneware and Earthenware 1650–1800 (New York: Sotheby’s Publications, 1990).

Diana Stradling, Jersey City: Shaping America’s Pottery Industry, 1825–1892 (Jersey City, N.J.: Jersey City Museum, 1997); Ellen Denker, “Exhibition Checklist,” in ibid. Watkins, Early New England Potters and Their Wares, p. 211.

Diana Stradling, Jersey City: Shaping America’s Pottery Industry, 1825–1892; Barber, The Pottery and Porcelain of the United States, pp. 21, 438–40; Lura Woodside Watkins, “Henderson of Jersey City and His Pitchers,” Antiques 50, no. 6 (December 1946): 390, 391.

Diana Stradling and Ellen Denker have an excellent enlarged copy of the D. and J. Henderson 1830 price list, first reproduced in Antiques 26 (September 1934): 109. In copying Greatbach’s design, other potters modified the hound, its arched back, and the floral decoration, leaving the hunt scene usually unchanged. All have an Albany slip interior not seen in the American Pottery Company examples. The glazing and modeling details of the copies are inferior compared with the original ones.

New Jersey State Museum, The Pottery and Porcelain of New Jersey, 1688–1900 (Newark, N.J.: Newark Museum, 1947), p. 48, no. 113, pl. 26. It is also listed in Clement, Notes on American Ceramics, p. 17, pl. 24; Watkins, “Henderson of Jersey City and His Pitchers,” p. 392, fig. 14; and Barber, The Pottery and Porcelain of the United States, p. 124.

Barber, The Pottery and Porcelain of the United States, pp. 438, 439; Diana Stradling, Jersey City: Shaping America’s Pottery Industry, 1825–1892.

Branin, The Early Makers of Handcrafted Earthenware and Stoneware, p. 189; Frelinghuysen, “Empire City Entrepreneurs: Ceramic and Glazes in New York,” p. 336.

Clement, Notes on American Ceramics, p. 18; New Jersey State Museum, The Pottery and Porcelain of New Jersey, 1688–1900, p. 46; Early Arts of New Jersey, The Potters Art, c. 1680–c. 1900 (Trenton, N.J.: New Jersey State Museum, 1956), p. 30; New Jersey Pottery to 1840 (Trenton, N.J.: New Jersey State Museum, 1972). Barber, Marks of American Potters, pp. 75–77. Barber was unaware at this time of the Salamander Works at Woodbridge. New Jersey State Museum, The Pottery and Porcelain of New Jersey, 1688–1900, p. 47, no. 138, and New Jersey Pottery to 1840, fig. 119.

Frelinghuysen, “Empire City Entrepreneurs: Ceramic and Glazes in New York,” p. 334, fig. 273.

Ibid., p. 49, pl. 39, cat. no. 146.

The usual Hanks and Fish Swan Hill mark described in the literature is larger, a bit more elaborate, and the swan faces right. Illustrated in Clement, Notes on American Ceramics, pl. 54; Lois Lerner, Lerner’s Encyclopedia of U. S. Marks on Pottery, Porcelain & Clay (Paducah, Ky.: Collector Books, 1988), p. 452; Ralph M. and Terry H. Kovel, Dictionary of Marks–Pottery and Porcelain (New York: Crown Publishers, 1995), p. 161. There are two pitchers with Rockingham glazes which have a mark similar to this one. These are illustrated in Jane Perkins Clany, “Rockingham Ware in America, 1830–1930: An Exploration in Historical Archaeology and Material Culture Studies” (Ph.D diss., University of Pennsylvania, 2000). This is a long-awaited work on Rockingham ware. Besides chapters on archaeology and material cultures, there is an excellent comprehensive history and definition of the term Rockingham as used in England and the United States. Arthur W. Clement, New Jersey Pottery to 1840 at New Jersey State Museum, Trenton, New Jersey Collection. There is also a known spittoon with the same mark. Branin, The Early Makers of Handcrafted Earthenware and Stoneware, pp. 197, 198.

Branin, The Early Makers of Handcrafted Earthenware and Stoneware, p. 201

“J. E. Jeffords & Company, Philadelphia, Pa., Illustrated List of Yellow, Rockingham, White Lined, Lava and Buff Stoneware,” Crockery and Glass Journal 3, no. 17 (1876).

Gates and Ormerod, “The East Liverpool, Ohio Pottery District,” p. 79; David Goldberg, Preliminary Notes on the Pioneer Potters and Potteries of Trenton, N.J.: The First Thirty Years, 1852–1882 (Trenton, N.J.: Trenton Museum Society, ca. 1983), p. 24.

Gates and Ormerod, “The East Liverpool, Ohio Pottery District,” p. 16; Goldberg, Preliminary Notes on the Pioneer Potters and Potteries of Trenton, N.J., pp. 24, 25, 40–42.

Barret, Bennington Pottery and Porcelain: A Guide to Identification, pp. 134–35.

A different Rockingham glazed pair of these figures in a private collection has W. H. F. Geddes, N.Y., incised on the back of the young girl, presumably for W. H. Farrar who worked at the Geddes pottery ca. 1840–1857. A similar pair is known made of cobalt blue decorated stoneware and marked “Lyons” in bluish script on their bases. See Vicki and Bruce Waasdorp, American Pottery Auction (September 22, 2002), no. 272. Both Nathan Clark (ca. 1822–1852) and Thomas Harrington (ca. 1852–1872) worked in Lyons, New York, during this period. Their pottery’s name was stamped under their respective names and “Lyons” on their stoneware. William Ketchum, Jr., Potters and Potteries of New York State, 1650–1900, 2d. ed. (Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 1987), p. 481. Ketchum does not list Lyons as an isolated mark.