Mug, Vauxhall, London, England, ca. 1715. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 7 5/8". (Courtesy, Chipstone Foundation, ex coll.: Ivor Noël Hume; all photos by Robert Hunter.)

Tavern mugs, England. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. of tallest 8 1/8". (Left) Vauxhall, London, dated 1731;(center) Vauxhall, London, dated 1722; (right) Bristol, ca. 1760. (Private collections, ex coll.: Ivor Noël Hume.)

Detail of punch party scene spring on a tavern mug, Vauxhall, London, England, dated 1737. (Private collections, ex coll.: Ivor Noël Hume.)

Michelle Erickson, Hampton, Virginia, 2015. Glazed stoneware. H. 9 1/2". (Courtesy, Carol Noël Hume Collection.)

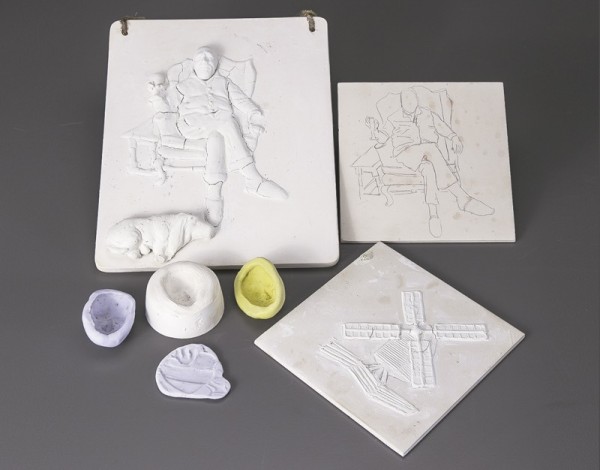

Sketch, molds, and model sprigs, Michelle Erickson, Hampton, Virginia, 2015. (Courtesy, Michelle Erickson.)

Ivor Noël Hume with Michelle Erickson examining the finished tavern mug, 2015.

Some ceramic collectors are content to own and admire while others extend to wondering how such a treasure could have been made. “Isn’t it amazing,” we marvel, “that way back then potters could be so inventive?” That display of ignorance and arrogance is usually as far as we go. Archaeologists, on the other hand, dig deeper. Learning how something was made is a step toward the ultimate goal of reaching the minds of both maker and user.

To what extent did practicality and beauty combine to influence the marketability of a common pot? In asking such questions we are reaching out—not to fawn over dead potsherds, but to appreciate the living, breathing life of the past. In other words we become students of social history rather than the aesthetics of connoisseurship.

My own focus has been on the evolution of English brown stonewares (fig. 1). Inherited from the Rhineland in the latter years of the seventeenth century, they would remain the standard kitchen and tavern ware into the twentieth century. It was a period wherein potters vied to make their products more appealing by capturing the fads of the moment, be they political slogans, victorious admirals, or monarchal patriotism. Then, too, there was the practical necessity of naming mugs and bottles to discourage thievery. Most such embellishments belonged to the second half of the eighteenth century and continued through the prolonged reign of Queen Victoria (r. 1837–1901).

The earliest examples were made in the Thames-side village of Fulham, to be followed by factories in Lambeth, Vauxhall, Mortlake, Bristol, and north into Scotland (fig. 2). There were so many that separating the products of one from another relies on guesswork and endless not always helpful debate. Identifying criteria rely heavily on differing details among the applied (sprigged) decoration (fig. 3).

The years that I spent studying and publishing these wares gave me an undeserved reputation for being a stoneware sage. Consequently, when our editor Rob Hunter said he had acquired a unique sprig-decorated tavern mug reputedly from London, he showed it to me over dinner in a poorly lit bistro to get my opinion. His companion, Michelle Erickson, helped build the drama of the revelation, saying that she knew that I would find it fascinating. Knowing them both so well I felt sure that I was in for a memorable experience.

My jaw, as novelists say, sagged. How was I to tell them that the mug was too big, the glaze too new, and the sprigging too robust. I had to hope that if the London source had sold it as dating from the eighteenth century Rob could get his money back. As I turned the mug around one of the smaller sprigs jumped out at me. Where there should have been hounds chasing a stag, there was a basset hound sitting contentedly at somebody’s feet. Closer inspection revealed that the somebody was me.

Michelle had used all the techniques employed in making eighteenth-century tavern mugs to create an 88th birthday present for me, commissioned by my wife Carol (fig. 4). The rest of the mug reflected our shared interest in mermaids, in excavated armor, in Indian arrow-heads, a German bottle in our collection and a palm tree remembrance of West Indian travel. A detail that I first thought to be a generously placed crown on my head turned out to be a broken chamber pot—put there at my wife’s request as symbolic of an archaeologist’s life. Or so she said.

Michelle had kept examples of every step in the process of decorating an eighteenth-century brown mug (fig. 5). Her original drawings, molds for each sprigged element, and step-by-step examples of the matrices and moldings had been retained to demonstrate the skills and labor, which, in the eighteenth century, had gone into creating a Queen Anne mug or another’s punch party panel. It is hard to imagine a more constructive gift for this or any other birthday.

If there is a moral to be drawn from this story, it has to be that no professed expert should be allowed to pontificate during a candlelit dinner (fig. 6).