Detail of Henricus Hondius’s Nova Virginiae Tabula, Amsterdam map of the Virginia colony and the Chesapeake Bay, 1630. 15 1/2 x 19 1/2". (Geographicus Rare Antique Maps Cooperation Project.)

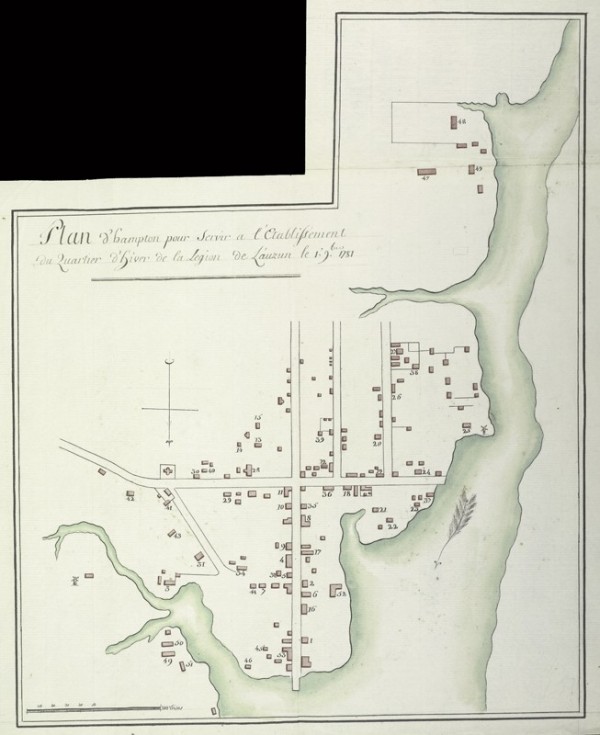

Plan d’Hampton pour servir a l’Etablissement du Quartier d’hiver de la Legion de L’auzun, le 1 9bre, 1781 (Plan of Hampton [Virginia] to be Used for Establishing the Winter Quarters of Lauzun’s Legion. 1 November 1781). 15 3/8" x 12 3/8". (Princeton University Library Collection.)

An 1864 photograph of the Grand Contraband Camp in Hampton, Virginia. (Courtesy, Library of Congress.) The camp was the first self-contained black community in the United States, with a population of 9,000 by 1865.

Photograph of fieldwork conducted by archaeologists from the College of William and Mary on the future site of Hampton’s Air and Space Center, 1988. (Photo, Robert Hunter.) Various seventeenth- and eighteenth-century trash pits containing large quantities of ceramics, glass, and animal bone can be seen.

Photograph of the excavation of an eighteenth-century cellar at the Goodyear-Kramer Tire Store lot on the corner of South King Street and Settlers Landing Road, 2006. The Hampton Air and Space Museum is in the background. (Courtesy, James River Institute for Archaeology, Inc.)

Photograph of a ca. 1690–1710 Westerwald stoneware mug moments after it was found in the fill of a seventeenth-century tavern cellar by archaeologists from the College of William and Mary, 1989. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

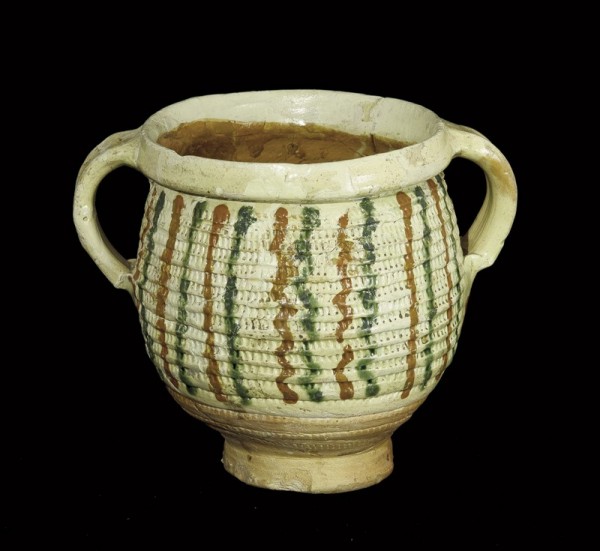

Weser slipware two-handle pot, Germany, 1590–1600. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 5 3/4". (Courtesy, St. John’s Episcopal Church, Hampton, Virginia; photo, Robert Hunter.) Weser ware was made in a number of production sites between the Weser and Leine Rivers in northern Germany. This example is distinguished by the addition of the unusual rouletted decoration.

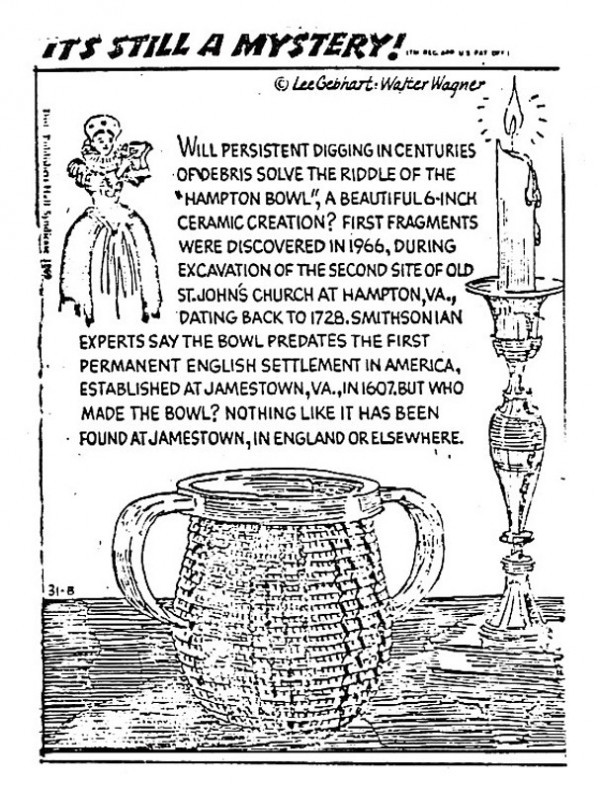

Illustration from Lee Gebhart and Walter Wagner, It’s Still a Mystery (New York: Scholastic Book Services, 1970).

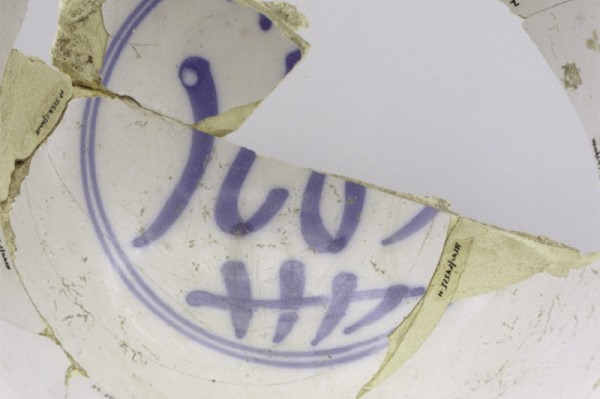

Dish, Portugal, ca. 1640. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 7 7/16". (Hampton University Museum; photo, Colonial Williamsburg.)

Reverse of the dish illustrated in fig. 9.

Jug, North Devon, England, ca. 1660–1670. Sgraffito slipware. H. 6". (Courtesy, Hampton History Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Dish, attributed to William Oliver, North Devon, England, dated 1668. Sgraffito slipware. D. 10". (Courtesy, Hampton History Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Punch bowl, possibly Brislington, England, or Netherlands, 1689. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 9 1/2". (Courtesy, Hampton History Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing 1689 date inscribed inside the bowl illustrated in fig. 13.

Salt, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1690–1700. Slipware. W. 4". (Courtesy, Hampton History Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Michelle Erickson, Hampton Salt, 1990. Slipware. H. 2 3/4". (Photo, Robert Hunter.) Facsimiles of the Staffordshire salt illustrated in fig. 15, showing the conjectural base of the original.

Trencher salt, Hugh Quick, London, ca. 1674. Pewter. (The British Museum, Portable Antiquity Scheme, www.finds.org.uk, Unique ID: LON-A83118.) Note the hexagonal shape.

Mugs, Westerwald, Germany, ca. 1690–1701. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. of tallest 4 3/16". (Courtesy, Hampton History Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

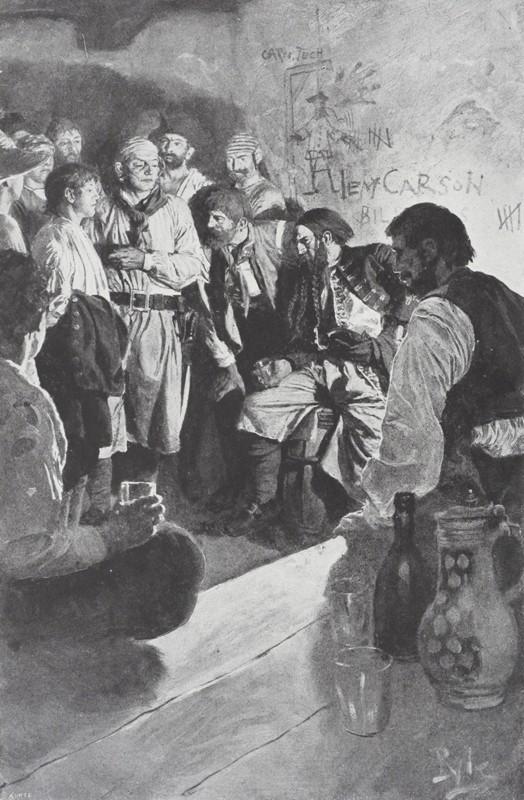

Illustration from Howard Pyle, The Story of Jack Ballister’s Fortunes (New York: The Century Co., 1895), p. 136. Pyle’s narrative recounts the adventures of a young man who was kidnapped in 1719 and carried to the plantations of Virginia, where he fell in with Captain Edward Teach, known as Blackbeard. Note the Westerwald stoneware jug in the right foreground.

Teapot, attributed to William Greatbatch, Staffordshire, England, 1760–1765. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 5". (Courtesy, Hampton History Museum; photo, Robert Hunter.) William Greatbatch was the most talented Staffordshire designer and maker of ceramic models and molds during the second half of the eighteenth century.

Waste bowl, Staffordshire, England, 1760–1770. Lead-glaze earthenware. D. 4 3/4". (Courtesy, Hampton History Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Sauceboat, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1775. Slip-decorated creamware. L. of fragment 5". (Courtesy, Hampton History Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Sauceboat, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1775. Slip-decorated creamware. L. 7 3/16". (Courtesy, The Mint Museum, Museum Purchase: Delhom Collection, 1965.48.1677.)

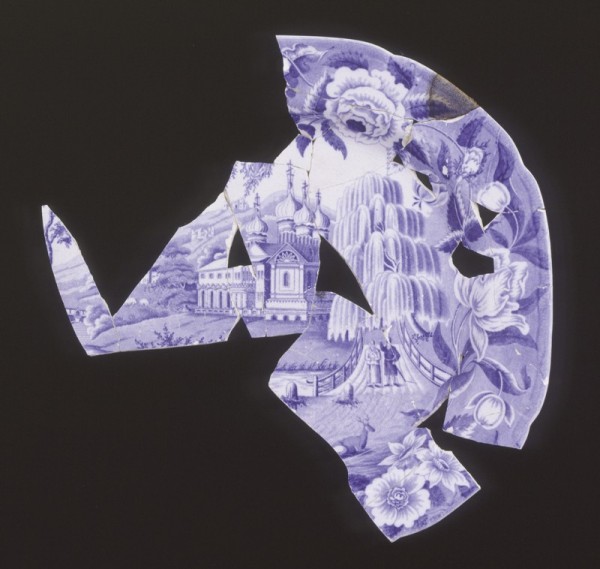

Dish, Staffordshire, England, 1820–1830. Pearlware. W. 12 3/4". (Courtesy, Hampton History Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Transfer-printed in the so-called Russian Scenery pattern.

Plate, possibly Davenport, Staffordshire, England, 1820–1830. Pearlware. D. 10". Marks: impressed anchor mark on the reverse; printed “SEMI CHINA” (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.) An antique example of the so-called Russian Palace pattern. It differs from the excavated example illustrated in fig. 24, suggesting that more than one manufacturer copied the pattern.

Jug, probably Staffordshire, England, 1850–1860. Whiteware. H. 6 1/4". (Courtesy, Hampton History Museum; photo, Robert Hunter.)

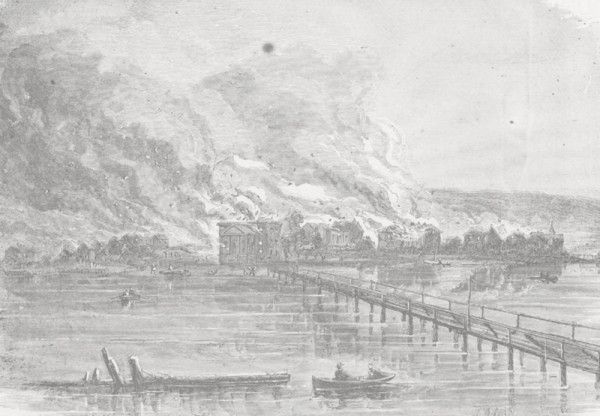

“The Burning of Hampton by the Rebel Forces under Colonel Magruder,” Harper’s Weekly, August 31, 1861, p. 550.

Hampton, Virginia, lies at the gateway of Hampton Roads, one of the world’s largest natural harbors. Located near the mouths of Virginia’s major rivers—the Elizabeth, the Nansemond, the James, and the York—Hampton is a natural defensive location, having access to marine and terrestrial resources and to the transportation routes inland (fig. 1). The area has been continuously occupied since the last Ice Age and was among the earliest North American locales visited by Spanish and English explorers.[1]

Native Americans were the first to make their homes on the broad flats adjacent to the Hampton River and the Chesapeake Bay. In 1607 Captain Christopher Newport, on his way to settle Jamestown, first stopped at the flourishing Powhatan Indian village called Kecoughtan.[2] By 1610 the English interlopers had erected several defensive forts along with a church and ultimately drove out the local natives. With these early beginnings, Hampton is often recognized as the oldest continuous English-speaking settlement in North America.[3]

By 1619 the settlement had grown and was renamed Elizabeth City, for the daughter of King James I (r. 1567–1625). By 1623 the town had established itself east of the Hampton River with a population of about 350. For much of the seventeenth century, Hampton was to remain a dispersed agrarian settlement.[4]

The 1680 Town Act secured the creation of the formal town of Hampton but it was not until 1691 that its principal streets of King and Queen were laid out (fig. 2). By late 1693 twenty-six half-acre lots had been sold.[5] In 1708 the Virginia General Assembly’s Act of Ports designated Hampton as an official port and established a customhouse there for the Lower James River District.[6] Cargo ships entering or leaving the area had to stop for inspection and tolls.

Merchants, tradesmen, and transient seamen shaped the character of Hampton’s economy for much of the first half of the eighteenth century. At least six waterfront taverns were in operation by the 1690s, and they were essential gathering places for the seamen hailing from many foreign ports. As a maritime haven, the town of Hampton developed a cosmopolitan but often raucous and lawless reputation.

Plantation-grown tobacco, tar from the local pine forests, and wheat and corn were among the primary exports. Hampton merchants competed for wharf space to import the latest goods from British ships. A large percentage of African slaves who went to work at plantations along the James and York Rivers came through the Hampton port.

Hampton’s maritime economy continued to grow in the early eighteenth century until sand bars developed that prevented larger ships from docking. As a consequence, nearby Norfolk, Virginia, became the preferred port for the region and by the 1740s the customhouse was relocated there. Hampton became a much quieter port town during the latter half of the eighteenth century and shipbuilding became a prominent trade. By the 1760s, the taverns of Hampton were known for their upscale hospitality, welcoming both arriving travelers and the local gentry.[7]

Hampton remained a relatively quiet village serving as a hub for the agrarian economy of the outlying areas for the last part of the eighteenth century. The British invaded Hampton during the American Revolution but little damage was done to the town. The British returned to Hampton during the War of 1812, burning buildings and committing acts of rape, pillage, and murder. Hampton recovered from these atrocities but ultimately the colonial buildings of the town were obliterated when they were burned to the ground at the outset of the Civil War. Within these ruins of the colonial townscape, a large settlement of freed and escaped slaves from Southern plantations took refuge in a hodgepodge of shanties and cabins, referred to in the North as “contraband camps,” during and after the war (fig. 3).[8]

The infrastructure of Hampton was slow to recover during Reconstruction, but tremendous growth took place in the twentieth century, with new industrial developments and the establishment of military bases in the Hampton Roads region. Of national importance is Hampton’s continuing role in America’s period of space exploration, beginning with the establishment of the NASA Langley Research Center in 1958.

Although the geographic size of Hampton pales in comparison to other major colonial centers, it has been the focus of some of the most intensive archaeological investigations in America—since the 1960s, more than two dozen professional investigations as well as excavations by concerned citizen archaeologists have been conducted there (fig. 4).[9] These studies have recovered evidence from Native American settlements, seventeenth-century plantations, and eighteenth- and nineteenth-century urban dwellings and taverns (figs. 5, 6). Thousands of ceramic artifacts are curated in the Hampton History Museum, and some of the most significant examples have been incorporated into their permanent galleries. Only a few are illustrated and discussed in this article but it is fair to say that Hampton has one of the richest archaeologically recovered assemblages of eighteenth-century English ceramics in the country.

Weser Slipware Two-Handle Pot

Between 1966 and 1970 archaeological excavations were conducted at the suspected site of the Second Church of Elizabeth City Parish.[10] The church was built in 1623 by the Virginia Company of London on the east side of the Hampton River and remained in service until 1667, when it was relocated. The church’s foundation and brick flooring were uncovered and mapped, along with the recovery of numerous artifacts.

Of particular significance was the recovery of a nearly complete two-handle pot known as Weser ware, made in an area of northern Germany (fig. 7). The pot was dated to 1590–1600, well before the construction date of the church. This early artifact created quite a stir among archaeologists and historians.[11] The discovery also attracted public attention, as the attempt to understand the vessel’s association with the later church was featured in “It’s Still a Mystery,” a nationally syndicated column (fig. 8).

The most likely explanation is that the vessel was from deposits created in 1611, when Lord De La Warr, first governor of Virginia, ordered construction of several defensive forts along the Hampton waterfront. One of those, Fort Henry, shared the same location as the later 1623 church. It is hoped that future excavation on the site will discover the remains of that earlier occupation. While Weser ware continues to be found in early Virginia contexts, this vessel remains the most complete example yet discovered in Virginia.[12]

Portuguese Majolica Sun-Face Dish

Another ceramic find from one of Hampton’s earliest English sites underscores the international scope of material culture found in relatively high-status colonial homes during the first half of the seventeenth century.[13] Archaeologists working in seventeenth-century sites in Virginia’s tidewater region routinely encounter fragments of Portuguese majolica.[14] Portuguese majolica was also widely used in New England during most of the seventeenth century.[15] Nevertheless, it remains a relatively understudied area of ceramic history.[16]

The circa 1640 Portuguese majolica dish illustrated in figures 9 and 10 was recovered from property on the Hampton River believed to have been part of the glebe lands set aside for clergy members assigned to the Kecoughtan Parish.[17] Excavations conducted by archaeologists from Colonial Williamsburg revealed a complex of several post-in-ground buildings, one having a rare tile-floored, brick-lined cellar that had been occupied from the 1630s to about 1660. The ceramic assemblage was rich and diverse with tin-enameled products from England, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain.[18] The partially complete dish was one of nine different Portuguese vessels found at the site.

European tin-glaze potters in the seventeenth century generally copied the blue-and-white Chinese porcelain “Kraak” wares with patterns derived from late Ming-dynasty porcelain of China’s Wan Li period (1572–1620). While this dish has elements of these Ming motifs, it is particularly distinctive because of the unusual sun face, not seen previously in examples from American archaeological contexts.

North Devon Slipware Dish

The North Devon potteries of England exported tremendous amounts of earthenware to North America in the seventeenth century. Examples of North Devon plain ware and the distinctive gravel-tempered variety are found in the earliest sites of the Chesapeake region. In the second quarter of the seventeenth century, examples of sgraffito-decorated North Devon slipwares begin to appear in local archaeological sites.[19] By the 1660s North Devon decorated slipware was nearly ubiquitous in Chesapeake archaeological contexts.[20]

In 1996 archaeologists from the College of William and Mary investigated a seventeenth-century trading plantation that was part of a 150-acre tract of land purchased by William Claiborne in 1630 and later owned by ship captain and merchant Thomas Jarvis. In addition to the numerous features related to the post-in-ground construction of the main house, several related trash-filled pits were excavated, one of which contained thirteen North Devon sgraffito-decorated vessels (fig. 11).[21] Of particular interest was a fragmentary North Devon sgrafitto dish dated 1668 (fig. 12).[22] This dish is the earliest dated North Devon example to be recorded in an American context.[23]

The dish is highly ornamented with an elaborate scalloped rim and a flowering plant in a basket in the center. Fanciful cockerels are part of its decorative scheme, motifs used by Barnstaple potter William Oliver, who worked from about 1655 to 1691.[24] Wasters found at the site of Oliver’s pottery contain dates between 1669 and 1689. If the attribution is correct, the 1668 Hampton dish may be the earliest dated example of Oliver’s work.

Delft Punch Bowl

The excavation of the Jarvis Plantation in Hampton produced an incredible wealth of late-seventeenth-century material culture related to high-status dining and the consumption of alcohol. Found in the same large trash pit that produced the North Devon vessels discussed previously was a nearly complete blue-and-white tin-glazed punch bowl (fig. 13). The bowl is decorated in a chinoiserie style of the so-called Chinese Scholar pattern, and bears the date 1689 in the bottom of the bowl (fig. 14).[25]

Punch bowls were iconic vessels in Anglo-American drinking-ritual culture from the late seventeenth through the eighteenth century.[26] The potent mixture of alcohol, fruit juices, sugar, water, and spices was adapted from a beverage brought from India to the West by Portuguese and Dutch sailors in the mid-seventeenth century. Although initially a sailor’s drink, punch became a beverage enjoyed by the upper levels of society.[27] The earliest mention of punch drinking from the colonial South comes from Maryland court records of 1670.[28] Inventory data from nearby York County first records the presence of a punch bowl in 1682.[29] Punch is mentioned by 1692 in records of Elizabeth City County’s taverns.[30]

Ceramic punch bowls have their origins in Chinese porcelain and stoneware prototypes. The dated tin-glazed punch bowl associated with the Jarvis occupation of the site is a candidate for one of the earliest punch bowls yet found in Colonial Virginia and may be the earliest dated example from an American context.

Staffordshire Slipware Salt

One of the true ceramic treasures from Hampton’s excavations is a remarkable Staffordshire slip-decorated salt (fig. 15). Salts are rarely seen in Staffordshire slipware.[31] This example was part of a massive trash deposit associated with an early waterfront tavern dating to the 1690s.[32] The deposit contained other tangible treasure: two real de a ocho, also known as Spanish dollars or eight-real coins. One coin, minted in Lima, Peru, was dated 1691; the other, minted in Potosi, Bolivia, was dated 1658. The presence of these coins amid the tremendous quantities of clay tobacco pipes, glass wine bottles, Staffordshire slipware, Chinese porcelain, North Devon coarsewares, and delft punch bowls reflects the rich material trappings associated with Hampton’s maritime heyday in the 1690–1730 period.

The slipware salt emerged from the ground nearly intact, only missing its pedestal base, which was never found. However, the complete form, which originally was wheel thrown and the rim then trimmed to create its hexagonal shape, was subsequently brought to life in a facsimile fashioned by ceramic artist Michelle Erickson (fig. 16). The additional embellishment was added when the wet form was covered in a dark ground slip and subsequently highlighted with trailed white-slip decoration. The hexagonal shape of the salt mimics English silver and pewter examples of the late seventeenth century (fig. 17).[33]

Westerwald Tavern Mugs

The history of Hampton is intertwined with swashbuckling maritime lore of the early eighteenth century. Several notable buccaneers used Hampton as a homeport, and pirate prisoners often arrived in Hampton for trial and execution by Elizabeth City County court justices. In 1718 the severed head of Edmund Teach—the infamous Blackbeard—was returned to Hampton by Virginia governor Alexander Spotswood to hang on a pole as an admonishment for all entering ships to see.

Tavern keepers were often enlisted to provide food and drink for imprisoned sailors in addition to their regular clientele. Although many of the area’s pirate tales are somewhat romanticized, there is no doubt that Hampton’s waterfront taverns served unsavory maritime outlaws on many occasions.[34] The two nearly complete German Westerwald stoneware mugs or tankards illustrated in figure 18 may well have been used to hoist rum or ale during onshore carousing by a ship’s crew, pirate or otherwise (fig. 19).

These mugs were found in the cellar of a circa 1680 post-in-ground building that undoubtedly functioned as a tavern. Other drinking vessels found in the same cellar include eight mugs, seven cups, and fragments from nine punch bowls.[35] Westerwald stoneware of this type is fairly common in Virginia archaeological contexts of this period, but it is unusual to find matching vessels. The straight-sided vessels were decorated with a deep cobalt ground having applied flower heads highlighted in manganese oxide, which dates these circa 1680–1710, the time period at the height of Hampton’s “Golden Age of Piracy.”[36]

Staffordshire Press-Molded Earthenwares

After the customhouse moved from Hampton to Norfolk in the 1740s, the character of the town gradually shifted from a rambunctious seafaring port to a more gentile urban center. Hampton tavern keepers sought out the latest ceramics for their tables to keep in step with British fashion. Expensive Chinese porcelain is found in Hampton contexts from this period, along with Staffordshire’s finest earthenware.

The teapot with molded Chinese figures highlighted with rich underglaze colors of green and yellow illustrated in figure 20 represents one such example of Staffordshire’s best efforts.[37] Although its specific archaeological context in downtown Hampton has been lost, the teapot can be attributed to Staffordshire potter William Greatbatch, who was a prolific designer and maker of molds. In addition to his own pottery, he supplied Josiah Wedgwood on a contractual basis. Identifiable Greatbatch or Wedgwood products are very rare in most Virginia archaeological contexts of this period.

Another example of Staffordshire’s choice products is the mottle-glazed waste bowl (fig. 21), part of a tea service, found in a circa 1770 trash deposit associated with Hampton’s Bunch of Grape’s Tavern. Bunch of Grapes was recognized as the “Best accustomed house in town.”[38] This bowl, along with dozens of Chinese porcelain vessels and similar Staffordshire earthenwares recovered from the site, suggests that the ceramics did their part in upholding the tavern’s reputation.[39]

Marbled Slip–Decorated Sauceboat

Not all ceramics need an important historical context to be significant; sometimes those that come from the ground are just plain rare. As seen with the previous entry, Hampton consumers were treated to some of Staffordshire’s finest cream-colored wares made in the third quarter of the eighteenth century. A 1971 archaeological excavation of a house site on Queen Street produced an unusual example of a circa 1775 press-molded, creamware sauceboat with a marbled slip decoration (fig. 22).[40]

The marbled decoration represents the nascent period of production of the so-called mocha wares in the third quarter of the eighteenth centaury.[41] The earliest use of marbled slip decoration was reserved for ornamental wares such as Wedgwood’s vases and garnitures and expensive tea wares.[42] The application of marbled slip to a form like the sauceboat required special effort, as mocha wares were generally round cylindrical objects, such as bowls or mugs, and decorated while on a lathe.

Only two other examples of marbled sauceboats are known. One is in a private New England collection and the other is in North Carolina’s Mint Museum collection (fig. 23).[43]

Russian Scenery Transfer-Print Dish

For the first half of the nineteenth century, the town of Hampton remained a small but stable village inhabited by boat builders, watermen, tradespeople, and merchants. Far from being isolated, however, Hampton consumers had access to the global trade networks established by the British ceramic industry. The advancement of transfer-printing technology had created a huge profusion of patterns and colors, and the Staffordshire industry, hungry for new products, culled popular travel books for print sources. Consumers were treated to glimpses of exotic foreign lands on their dinner plates and tea china.

When first discovered in a circa 1850 Hampton privy deposit, the bright-blue image of a Russian church on a Staffordshire dish seemed totally incongruous with the cultural landscape of Tidewater Virginia (fig. 24).[44] Three dishes and one plate of this pattern were found, suggesting that the early-nineteenth-century occupants of the property owned a partial dinner service.[45]

From a ceramic collecting perspective, the blue-and-white pattern—it has been called “Russian Scenery” or “Russian Palace”— is considered particularly rare. More than one British manufacturer may have used slightly differing versions of the print (fig. 25).[46] The large building in the scene might be the Church of St. Dmitry on the Volga River. A specific engraving has not been found as the source print, but conceivably it was printed in a travel book such as the 1790 Journey from St. Petersburg to Moscow by A. Radishchev.[47]

Civil War Dipt-Ware Pitcher

Slip-decorated utilitarian earthenware was a mainstay of the British ceramics industry from about 1780 to 1860. Colorful, functional, and—perhaps most important—cheap, the bowls, pitchers, mugs, and jugs were shipped throughout the world. At first glance the pitcher illustrated in figure 26 is like many others used in mid-nineteenth-century American households. However, its archaeological context and scorched glaze make it one of the most poignant of Hampton’s historical ceramics.

Hampton’s era of nineteenth-century tranquility came to an abrupt end with the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861. Federal troops almost immediately reinforced nearby Fort Monroe, which remained under their control for the duration of the war. In an effort to deprive Federal troops of the use of Hampton’s residences and warehouses, on August 7, 1861, Confederate Brig. Gen. John B. Magruder led a raid with 500 soldiers and burned the town to the ground.[48] Of the town’s some 500 buildings, only a handful were left standing when the fires subsided (fig. 27). It was a controversial act of desperation, and forever destroyed the colonial architecture of this seaport town.

The pitcher was found during archaeological excavations in the cellar rubble of a house once owned by Hampton merchant Thomas Watts and his wife.[49] The pitcher was buried deep in a layer of black ash and soot, clearly a victim of the 1861 conflagration. It is now on display in the Hampton History Museum as a grim reminder of the city’s sometimes tragic past.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank Joe Jones and David Lewes of the William and Mary Center for Archaeological Research for their help with supplying information on the excavations in Hampton. Nick Luccketi and Hank Lutton also shared their Hampton research. Chris McDaid shared his dissertation and related publications on Hampton’s eighteenth-century taverns. Beth Austin of the Hampton History Museum provided invaluable help with obtaining photographs and background about earlier Hampton archaeological finds. Jim Tormey and Jack Pope from St. John’s Episcopal Church in Hampton graciously assisted with the photography of the Weser two-handle jar recovered from the site of the Second Church of Elizabeth City Parish.

A very rare Clovis-period spear blade, a diagnostic relic of the Paleo-Indian era (ca. 10,000 BP) was found during the 1988 archaeological excavation of the site for the nationally acclaimed Hampton Air and Space Museum. Thomas F. Higgins III, Charles M. Downing, J. Michael Bradshaw, Karl J. Reinhard, Gregory J. Brown, Deborah L. Davenport, and Irwin Rovner, The Evolution of a Tidewater Town: Phase III Data Recovery at Sites 44HT38 and 44HT39, City of Hampton, Virginia, Technical Report Series 12, 2 vols. (Williamsburg, Va.: The Society of the Alumni, The College of William and Mary, 1993).

Numerous spelling variations include Kicotan, Kiccowtan, and Kikowtan.

Lyon G. Tyler, History of Hampton and Elizabeth City County, Virginia (Hampton, Va.: Board of Supervisors of Elizabeth City County, 1922), available online at https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/009599920 (accessed January 30, 2017).

Marion L. Starkey, The First Plantation: A History of Hampton and Elizabeth City County, Virginia, 1607–1887 ([Hampton, Va.]: Houston Printing and Publishing, 1936).

Joe Frankoski and Judith Milteer, “From the Sea to a City,” in, Hampton: From the Sea to the Stars, 1610–1985, edited by James T. Stensvaag (Norfolk, Va.: Donning, 1985), pp. 11–31.

Emily J. Salmon and Edward D. C. Campbell Jr., The Hornbook of Virginia History: A Ready-Reference Guide to the Old Dominion’s People, Places, and Past, 4th ed. (Richmond: Library of Virginia, 1994), p. 191; Higgins et al., Evolution of a Tidewater Town, pp. 28–29; Tyler, History of Hampton, p. 29.

Christopher L. McDaid, “‘The Best Accustomed House in Town’: Taverns as a Reflection of Elite Consumer Behavior in Eighteenth-Century Hampton and Elizabeth City County, Virginia,” Ph.D. diss., University of Leicester, School of Archaeology and Ancient History, 2013.

See, “The Contraband Camps,” Boundless U.S. History, https://www.boundless.com/u-s-history/textbooks/boundless-u-s-history-textbook/the-civil-war-1861-1865-18/emancipation-during-the-war-131/the-contraband-camps-707-4621/ (accessed January 28, 2017).

For a summary of archaeological investigations conducted in Hampton, see Mark St. John Erickson, “Rescuing Hampton’s Past One Archaeological Dig at a Time,” Daily Press (Newport News, Va.), May 16, 2016, available online at http://www.dailypress.com/features/history/dp-nws-old-hampton-dig-tours-20160521-story.html (accessed January 28, 2017). Through local amateur explorations in the 1960s and 1970s, we recovered some remarkable ceramic objects still in private hands. See also Joseph L. Benthall, Buried Treasure ([Hampton, Va.]: Hampton Association for the Arts and Humanities, 1973).

Eleanor Sayer Holt, The Second Church of Elizabeth City Parish, 1623/4–1698: An Historical-Archaeological Report, Archaeological Society of Virginia Special Publication 13 (Richmond: Archaeological Society of Virginia, 1985).

Ibid., pp. 98–113.

The two-handle jar is on display at St. John’s Episcopal Church Parish House in downtown Hampton.

Beverly Straube, “European Ceramics in the New World: The Jamestown Example,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2001), pp. 47–71.

Robert Hunter, “English Delft from Williamsburg’s Archaeological Contexts,” in John C. Austin, British Delft at Williamsburg (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation in association with Jonathan Horne Publications, 1994), pp. 24–29.

Steven R. Pendery, “Portuguese Tin-Glazed Earthenware in Seventeenth-Century New England: A Preliminary Study,” Historical Archaeology 33, no. 4 (1999): 58–77; Charlotte Wilcoxen, “Seventeenth-Century Portuguese Faianca and Its Presence in Colonial America,” Northeast Historical Archaeology 28, no. 1 (1999), available online at http://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/neha/vol28/iss1/2 (accessed January 28, 2017).

In contrast, see the work of Tânia Manuel Casimiro, Portuguese Faience in England and Ireland, BAR International Series 2301 (Oxford, Eng.: Archaeopress, 2011), translated from the Portuguese.

Andrew C. Edwards, William E. Pittman, Gregory J. Brown, Mary Ellen N. Hodges, Marley R. Brown III, and Eric E. Voigt, Hampton University Archaeological Project, Volume 1: A Report on the Findings (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1989).

Ibid., pp. 117–39.

Ivor Noël Hume, If These Pots Could Talk: Collecting 2,000 Years of British Household Pottery (Milwaukee, Wis.: Chipstone Foundation, 2001), pp. 237–39, 300–303.

In the 1930s a remarkable group of North Devon slipware vessels were excavated at Jamestown. Recovered from a drainage or boundary ditch and dating to the 1670s, the assemblage is thought to represent the contents of a shipping crate or barrel whose contents had broken in transit. With more than fifty nearly complete vessels representing at least a dozen different vessel forms, this group was first published by C. Malcolm Watkins, North Devon Pottery and Its Export to America in the 17th Century, United States National Museum Bulletin 225 ([Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution], 1960), and subsequently by Merry Outlaw, “Scratched in Clay: Seventeenth-Century North Devon Slipware at Jamestown, Virginia,” Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2002), pp. 17–38. Without question, this collection represents the best-preserved evidence of seventeenth-century North Devon vessels in the world.

Thomas F. Higgins III, Charles M. Downing, and Donald W. Linebaugh, Traces of Historic Kecoughtan: Archaeology at a Seventeenth-Century Plantation (Williamsburg, Va.: William and Mary Center for Archaeological Research, The College of William and Mary, 1999), p. 88.

Ibid.

Robert Hunter, “17th-Century North Devon Slipware and the ‘Keep Me’ Factor,” in A Glorious Empire: Archaeology and the Tudor-Stuart Atlantic World; Essays in Honor of Ivor Noël Hume, edited by Eric Klingelhofer (Oxford, Eng.: Oxbow Books, 2013), pp. 169–72.

Alison Grant, North Devon Pottery: The Seventeenth Century ([Exeter], Eng.: University of Exeter Press, 1983), p. 21.

Higgins et al., Traces of Historic Kecoughtan, p. 97; Sarah Fayen Scarlett, “The Chinese Scholar Pattern: Style, Merchant Identity, and the English Imagination,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2011), pp. 2–45.

Sharon V. Salinger, Taverns and Drinking in Early America (Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002).

Mary C. Beaudry, Janet Long, Henry M. Miller, Fraser D. Neiman, and Garry Wheeler Stone, “A Vessel Typology for Early Chesapeake Ceramics: The Potomac Typological System,” in Documentary Archaeology in the New World, edited by Mary C. Beaudry (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), pp. 51–67.

Proceedings of the Provincial Court, 1679–1680/1, vol. 69, p. 334, available online at Archives of Maryland Online, http://aomol.msa.maryland.gov/000001/000069/html/am69—334.html:

670 John Parker Dr To John Richardson T Tobacco

May 19th ...To 6 bowles of punch at 6o) 20th To one

bowle of punch att 6o .................... 420

Eleanor Breen, “‘One More Bowl and Then?’: A Material Culture Analysis of Punch Bowls,” Journal of Middle Atlantic Archaeology 28 (2012): 81–98.

Rosemary Corley Neal, Elizabeth City County, Virginia (Now the City of Hampton): Deeds, Wills, Court Orders, Etc. 1634, 1659, 1688–1702, 2 vols. ([Bowie, Md.]: Heritage Books, 1986), 1:90.

Michelle Erickson and Robert Hunter, “Dots, Dashes, and Squiggles: Early English Slipware Technology,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2001), pp. 94–114; Leslie B. Grigsby, English Slip-Decorated Earthenware at Williamsburg (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1993).

Higgins et al., Evolution of a Tidewater Town.

For an example, see https://finds.org.uk/database/artefacts/record/id/257422 (accessed January 28, 2017).

A human skeleton unearthed during the excavation of the site of the Radisson Hotel was purported to be an early-eighteenth-century pirate. Jerome D. Traver and Ronald A. Thomas, eds., Archaeological Data Recovery at 44HT20, Radisson Hotel Tract, City of Hampton, Virginia, 3 vols. (Williamsburg, Va.: MAAR Associates, 1989), 2:198–202.

Deborah Davenport, “Artifact Analyses, Site 44HT38,” in Higgins et al., Evolution of a Tidewater Town, 2:3.

Janine E. Skerry and Suzanne Findlen Hood, Salt-Glazed Stoneware in Early America (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 2009), pp. 42–43.

Benthall, Buried Treasure.

Virginia Gazette, April 16, 1767, p. 3, col. 1.

Davenport, “Artifact Analyses, Site 44HT38,” pp. 14–16.

It was found in the well of the dwelling site designated as 44EC28. Benthall, Buried Treasure.

Donald Carpentier and Jonathan Rickard, “Slip Decoration in the Age of Industrialization,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2001), pp. 115–34.

Leonard S. Rakow and Gary Tropper, eds., Wedgwood Specialties: Fairyland Lustre, Tricolor, Drabware, Basalt, Wedgwood’s Contemporaries, Miniatures, Encaustic, Variegated, published on the 25th anniversary of the Wedgwood Society of New York (Brooklyn: Wedgwood Society of New York, 1982).

Brian D. Gallagher, ed., British Ceramics, 1675–1825: The Mint Museum, with contributions by Barbara Stone Perry, Letitia Roberts, Diana Edwards, Pat Halfpenny, Maurice Hillis, and Margaret Ferris Zimmerman (Charlotte, N.C.: Mint Museum, in association with D. Giles, London, 2015), p. 46.

Davenport, “Artifact Analyses, Site 44HT38,” pp. 21–25.

Ibid., p. 21.

A. W. Coysh and R. K. Henrywood, The Dictionary of Blue & White Printed Pottery, 1780–1880 (Woodbridge, Suffolk, Eng.: Antique Collectors’ Club, 1982), p. 316. The online database of the Transferware Collectors Club suggests that this particular print was used for entire dinner services. See http://www.transcollectorsclub.org.

The title page of this is available online at http://cultureru.com/journey-from-st-petersburg-to-moscow-a-radishchev-title-page/ (accessed January 28, 2017).

“The Burning of Hampton,” Charleston Mercury, August 14, 1861.

Nicholas M. Luccketti and Hank D. Lutton, An Interim Report on the Archaeological Investigations at the Goodyear-Kramer Tire Store Lot, Hampton, Virginia (2007), pp. 30–31, on file at the James River Institute for Archaeology, Williamsburg, Va.