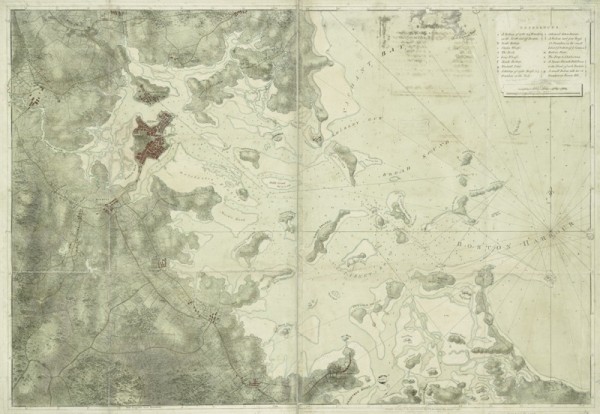

Joseph F. W. Des Barres, A Chart of the Harbour of Boston, 1775. 32 x 48". (Courtesy, Norman B. Leventhal Map Center, Boston Public Library.)

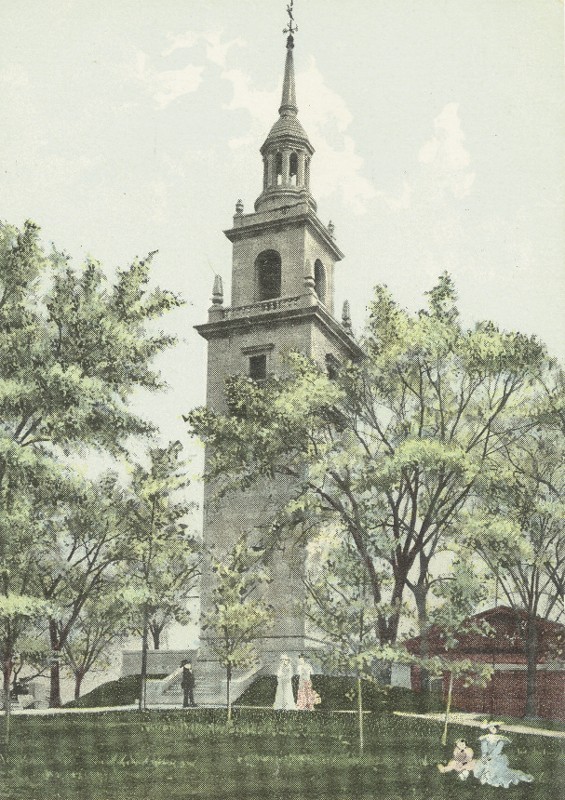

Metropolitan News Co., Boston, Massachusetts, Evacuation Monument, Dorchester Heights, ca. 1901–1907. 3 1/2 x 5 1/2". (Courtesy, Boston Public Library.) The monument commemorated the fortification of Dorchester Heights, which led to the evacuation of British troops from Boston on March 17, 1776.

Pearl and Milk Streets Looking Southwest, After the Fire, November 9–10, 1872. Albumen silver print from glass negative. (Courtesy, Boston Public Library; photo, James Wallace Black.) Residents stand among ruins of downtown Boston after the fire of 1872.

Commonwealth Avenue in Process, ca. 1872. Albumen silver print from glass negative. (Courtesy, Boston Public Library; photographer unknown.) This view is of newly built Victorian row house mansions in the recently created Back Bay neighborhood, formerly a tidal mud flat.

Conjectural drawing of (left) Early Woodland pottery, ca. 3000–2600 BP, and (right) Late Woodland pottery, ca. 1000–400 BP. (Courtesy, Massachusetts Archaeological Society; artwork by William S. Fowler.)

Vessel fragment, 3200–1000 BP, attributed to the Massachusett Native People. Low-fired earthenware. L. 1 7/8". (Courtesy, City of Boston Archaeology; photo, Joseph M. Bagley and Jennifer L. Poulsen.) The fragment was recovered on Boston Common in 1986.

Dish fragments, Portugal, seventeenth century. Tin-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, City of Boston Archaeology; photo, Joseph M. Bagley and Jennifer L. Poulsen.) All of these fragments were excavated from the James Garrett site.

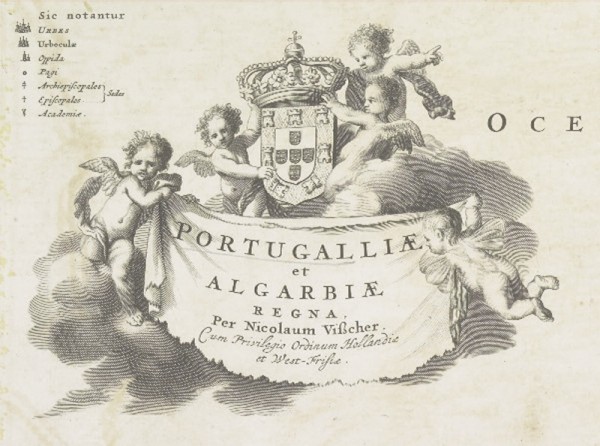

Cartouche detail, from PORTUGALLIÆ et ALGARBIÆ REGNA, Per Nicolaum Visscher. Cum Privilegio Ordinum Hollandiæ et West-Frisiæ [Portugal and the Algarve, by Nicolaes Visscher, with privilege of Holland and West Frisia], 1683–1698. (Courtesy, British Library, London, UK / © British Library Board. All Rights Reserved / Bridgeman Images. Shelfmark Cartographic Items Maps K.Top.74.48.)

Storage jar, Boston, Massachusetts, seventeenth century. Lead-glazed red earthenware. H. 11 3/4". (Courtesy, City of Boston Archaeology; photo, Joseph M. Bagley and Jennifer L. Poulsen.) Only the interior of this jar is glazed.

Detail of the glazed interior of the jar illustrated in fig. 9, showing weathering where the cherries were in contact with the vessel walls. (Courtesy, City of Boston Archaeology; photo, Joseph M. Bagley and Jennifer L. Poulsen.)

Sugar cone, likely Boston, Massachusetts, area, ca. 1728. Red earthenware. H. of upper fragment 11", H. of lower fragment 4". (Courtesy, City of Boston Archaeology; photo, Joseph M. Bagley and Jennifer L. Poulsen.) The fragments were recovered from fill deposits at the former Town Dock under Faneuil Hall.

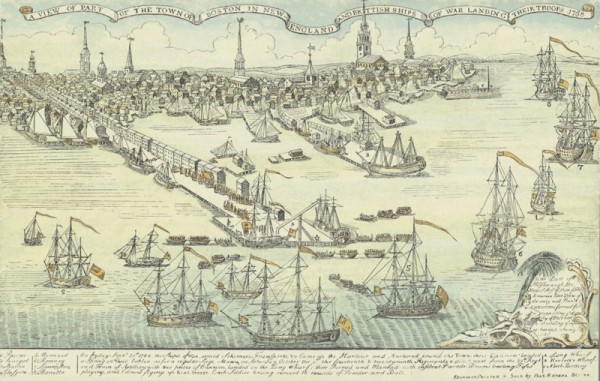

Paul Revere Jr. (1735–1818), A View of Part of the Town of Boston in New-England and Brittish Ships of War Landing Their Troops! 1768, printed 1770 by Alfred L. Sewell, Boston, Massachusetts. Hand-colored engraving. 9 13/16 x 5 9/16", on sheet 10 7/16 x 1515/16". (Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society.) Note Boston’s Long Wharf on the left and the Town Dock on the right.

Porringer, attributed to Parker pottery, Boston, Massachusetts, ca. 1742–1754. Lead-glazed, slip-decorated earthenware. D. 5 1/4". (Courtesy, City of Boston Archaeology; photo, Joseph M. Bagley and Jennifer L. Poulsen.)

Mug fragment on kiln brick, Boston, Massachusetts, ca. 1714–1754. (Courtesy, City of Boston Archaeology; photo, Joseph M. Bagley and Jennifer L. Poulsen.) This waster was recovered from the Parker Pottery Works site in 1986.

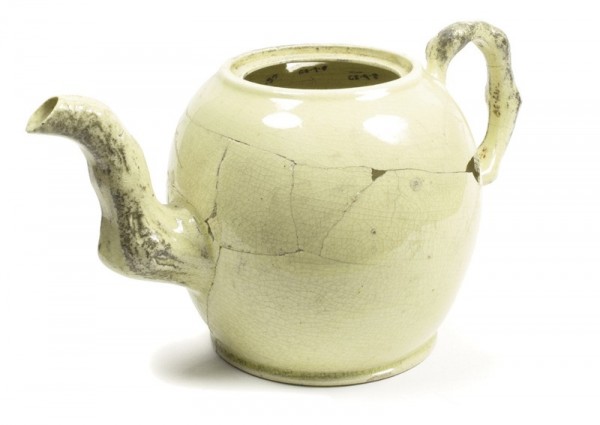

Teapot, probably Staffordshire, England, 1762–1775. Creamware. H. 3 1/2". (Courtesy, City of Boston Archaeology; photo, Joseph M. Bagley and Jennifer L. Poulsen.)

Nathaniel Currier, The Destruction of Tea at Boston Harbor, 1846. Hand-colored lithograph, 7 11/16 x 12 1/2". (Courtesy, Library of Congress.)

African Meeting House, Boston, Massachusetts, 1972. (Courtesy, City of Boston Archives; photo, Boston Redevelopment Authority.)

Soup plate, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1806. Pearlware. Extrapolated D. 9". (Courtesy, City of Boston Archaeology; photo, Joseph M. Bagley and Jennifer L. Poulsen.)

Charles King Dillaway [center] and Japanese students, 1860–ca. 1900. Carte de visite. 2 1/2 x 4 3/16". (Courtesy, Henry and Nancy Rosin Collection of Early Photography of Japan, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives, Smithsonian Institution, partial purchase and gift of Henry and Nancy Rosin, 1999–2001; photo, Antoine Sonrel. FSAA1999.35 479)

Vase fragment, Satsuma ware, Japan, ca. 1870. Earthenware with gilded polychromatic enamel overglaze designs. (Courtesy, City of Boston Archaeology; photo, Joseph M. Bagley and Jennifer L. Poulsen.) This type of raised surface decoration is called moriage.

Vase, Satsuma ware, Japan, ca. 1870–1890. Earthenware with gilded polychromatic enamel overglaze designs. H. 12". (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Partial miniature teaset, likely Germany, ca. 1860. Porcelain. H. of cream jug 1 1/2". (Courtesy, City of Boston Archaeology; photo, Joseph M. Bagley and Jennifer L. Poulsen.)

Doll’s head, Germany, ca. 1860. Unglazed porcelain. H. 2 1/4". (Courtesy, City of Boston Archaeology; photo, Joseph M. Bagley and Jennifer L. Poulsen.)

Paperweight, Dorchester Pottery Works, Boston, Massachusetts, early nineteenth century. Stoneware. L. 3 5/8". (Courtesy, City of Boston Archaeology; photo, Joseph M. Bagley and Jennifer L. Poulsen.) The paperweight is inscribed “1620” to commemorate the landing at Plymouth Rock.

Artifacts recovered from the Dorchester Pottery Works, Boston, Massachusetts, clockwise from top right: Henderson foot-warmer waster, partially burned daybook, two pieces of kiln furniture, and blue-decorated inkwell, early nineteenth century. L. of foot warmer 11". (Courtesy, City of Boston Archaeology; photo, Joseph M. Bagley and Jennifer L. Poulsen.)

More than twelve thousand years ago, the retreat of an ice sheet over what is now Boston exposed the land to nomadic Native American bands. Rising seas eventually transformed this hilly glacial landscape into a protected harbor of tiny islands, at the center of which was a prominent peninsula. Approximately three thousand years ago, Native groups began settling at the confluences of rivers and coastal outlets, taking advantage of newly stabilizing sea levels, stabilizing natural resources, and the development of new technologies, including ceramics and agriculture. When European explorers and colonists arrived in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries they encountered native people who called themselves the Massachusett and who referred to the peninsula as Shawmut.

In 1629 colonial governor and Puritan preacher John Winthrop and his fleet arrived at another, smaller peninsula just north of Shawmut which he named Charlestown, after Charles I. Realizing the brackish waters of the coastal town and its relatively sparse springs were not suitable for a future city, Winthrop moved his colonial capital south across the Charles River to Shawmut and founded the town of Boston (fig. 1).

Fish, trees, and a deep protected harbor gave Boston its economic strength, but Puritan laws governed all aspects of its residents’ daily lives, religion, and politics. By the turn of the eighteenth century the Enlightenment movement, coupled with the increasing wealth of Boston’s merchant class, diminished the effect of puritanical rule in favor of capitalism. As the city grew, the arrival and development of local artisans and craftspeople made the community less dependent on imported goods and services. This independent spirit percolated throughout society as Boston and the rest of America came to resent the heavy-handedness of the Crown’s oversight, meddling, and taxes.

Political outcry and demonstrations against the British during the 1760s led to physical violence at what became known as the Boston Massacre on March 5, 1770. Reacting to the rebellion, George III sent thousands of British Regulars to occupy Boston, blockade Boston Harbor, and quell the rebellion. These efforts were unsuccessful, as skirmishes led to battles that triggered the American Revolution.

A yearlong stalemate between the Regulars and rebels in Boston ended in 1776 with the fortification of Dorchester Heights, which prevented British troops from being able to defend themselves and their positions (fig. 2). On March 17, 1776, the British evacuated Boston.

As the Revolutionary War waged on, Boston turned its sights toward recovery and the development of the new nation. In 1780 Massachusetts passed its state constitution, which remains the oldest functioning constitution in the world. Following the war, the fledgling economy of the United States was still heavily reliant on ship production and trade with the Caribbean, which allowed Boston to flourish, although the return of the Boston Harbor blockade during the War of 1812 was disastrous to the city’s economy.

Boston recovered quickly, however, spurred on by a rapid increase in newly arrived English immigrants to the booming town, doubling its population between 1810 and 1830. During this period Boston saw its role in the young nation’s abolitionist movement result in a burgeoning population of freed slaves, freeborn blacks, and their supporters. The potato famine in Ireland and northern Europe, European overpopulation, and political upheaval in the mid- to late nineteenth century led to waves of Irish, Italian, and Jewish immigrants and a radical shift in population demographics in Boston.

A tragic fire that gutted downtown Boston in 1872, a new sewer system in 1874, and hundreds of acres of land created by filling the bays and estuaries resulted in a building boom (figs. 3, 4). Wealthy Bostonians of mostly English ancestry moved into newly built Victorian neighborhoods as ethnic neighborhoods developed and the population density increased downtown. Those immigrant communities faced oppression until political movements in the early twentieth century placed representatives of a broader spectrum of Boston residents in political power.

Urban renewal and car culture resulted in massive demolition of ethnic neighborhoods and the creation of new highways, housing developments, and commercial properties in their place in the 1950s and 1960s. As universities grew in number and population, Boston became known as a “college town” and the historic tourism industry flourished due to effective forethought in the historic preservation of significant buildings and landscapes. Broad urban-planning initiatives and late-twentieth-century highway projects such as the massive highway tunnel project known as the Big Dig in the early 1980s pumped money, businesses, and people into the city, and in the early twenty-first century a burgeoning technology industry provided Boston some protection from the Great Recession.

In response to the numerous ongoing archaeological investigations throughout the city, and at the urging of the Massachusetts Historical Commission, the City of Boston created the position of City Archaeologist in 1983. Joseph Bagley is currently the fourth City Archaeologist and runs Boston’s City Archaeology Program, which is responsible for conducting community and public archaeological surveys, archaeological education events, and maintaining an active social media presence. The program’s success is due primarily to the residents of Boston, who greatly appreciate and value the history of their city, and it relies heavily on volunteers and a robust local archaeological community for all of its activities. In 2016 Bagley published A History of Boston in 50 Artifacts, which features archaeologically recovered materials from the city, among them several of the ceramics discussed in this article.[1]

The ten ceramic artifacts we chose were recovered by professional archaeologists during archaeological surveys ahead of development and improvement projects on historic properties over a span of forty years. They represent Boston’s most notable ceramic finds that help tell the complex story of the city.

Fabric-Impressed Native Pottery

Ceramic history in Boston spans many centuries. The local marine clay deposit, the Presumpscot Formation, is the result of seawater rushing into the area behind the receding glacier.[2] Around three thousand years ago, during the Early Woodland period, ceramic production began in Massachusetts with thick-walled, conical-shaped vessels with fabric surface impressions (fig. 5, left). In the Middle Woodland period, between 2,600 and 1,000 years ago, decorations included exterior fabric impressions and more complicated rocker dentate, cord-wrapped stick, punctuation, and shell marks. By A.D. 1000 Iroquois-like vessel forms dominated, with globular bases, constricted necks, and highly incised decorated square, round, and canoe-shaped collared rims (fig. 5, right). The Massachusett used both grit and shell temper for their vessels, though grit temper dominates the pottery.

Most Boston-area native pottery finds are highly fragmentary. One especially large pottery fragment, however, bears the impression of carefully spun native fibers embedded in the clay (fig. 6). Most likely a fabric-wrapped paddle was used to consolidate the walls of the coil-formed vessel, also creating this distinctive surface. It was recovered on Boston Common in 1986, during an archaeological survey of the park for a lighting installation project.[3]

James Garrett’s Portuguese Tin-Glazed Earthenwares

Not having the infrastructure for production, early colonies including Boston required the import of many durable goods. Ceramics were no exception, and the diversity of ceramic origins was at its greatest during the seventeenth century. The James Garrett site was excavated ahead of the Big Dig in the early 1980s.[4] This small cellar hole measured only a few square meters in size, but its early date (1638–1656) coupled with the massive quantity of artifacts recovered from it makes it one of the most significant seventeenth-century sites in New England. Hundreds of fragments of dozens of tin-glazed vessels dominate the assemblage, which was also rich with German Westerwald and bellarmine stoneware, North Italian slipware, and North Devon and early Staffordshire slipware. The assemblage of tin-glazed ceramics contains some Dutch and Italian Montelupo wares, but it is the Portuguese tin-glazed wares decorated with stylized elements from the Portuguese coat of arms that are most dominant in number (figs. 7, 8).

As a wealthy merchant, James Garrett had access to a wide variety of wares and likely encountered these vessels during his trips to the Azores. Portuguese tin glazes are the dominant tin-glaze type encountered by the authors on all recently recatalogued early-seventeenth-century sites in Boston. This small sample of the Portuguese vessels from the Garrett site shows the wide variety of this ceramic type present in the assemblage, and demonstrates the much-overlooked contributions Portuguese ceramic artists and Portuguese traders had on early American colonial ceramic consumption.[5]

Katherine Nanny Naylor’s Cherry Jar

In 1992 archaeologists discovered Katherine Nanny Naylor’s unexcavated privy at the Cross Street site in Boston’s North End neighborhood.[6] This rare seventeenth-century urban site is remarkable as it is predominantly associated with a single mother and her children who continuously occupied the property for more than fifty years, from 1660 to 1716. Much of what we know of Katherine’s personal life is through salacious court documents that record allegations of adultery and the physical abuse of Katherine and her children by her second husband, Edward Naylor, the attempted poisoning of Katherine by Edward’s pregnant mistress (their servant), and the ultimate banishment of Edward after their divorce, the first recorded legal divorce in the Colonies.[7]

Though Puritans, the Naylors’ lives clearly were far from the persisting modern generalizations of an austere Puritan life in New England. Having inherited a large amount of money from her first husband, Katherine was exempt from sumptuary laws forbidding extravagant personal adornment and material culture in Puritan Boston. The archaeological assemblage demonstrates this through fine silks, lace, and expensive and sometimes lavishly decorated ceramics and glass.

Chemical analysis of the inside of the recovered storage jar illustrated in figure 9 revealed that it contained cherries, which left echoes of their presence etched in the glaze at the bottom of the vessel (fig. 10).[8] Archaeobotanical evidence confirms the household’s abundance of cherries and stone fruit, with more than 250,000 fruit pits recovered from the privy. This quantity of fruit suggests Katherine prepared cherry wine at home, which was illegal in Puritan Boston.

Town Dock Sugar Cones

As part of a “Triangular Trade” network, Boston imported partially refined sugar from the Caribbean to convert it into refined sugar and rum, then exported the rum and other goods to Africa, which in turn exported enslaved African people to the Caribbean to work on plantations that exported sugar to Boston. Sugar production included the placement of a slurry of partially crystallized sugar and molasses into large conical vessels with a small hole at their base (fig. 11). The molasses would drip through the base into a syrup jar, leaving behind a compact cone-shaped sugar mass. This, when fully refined, dried, and flipped over, formed a sugar loaf.

These unglazed earthenware vessels played a major role in the Atlantic trade and slave network. Archaeologists excavating fill deposits under the floor of Faneuil Hall ahead of an elevator installation project recovered several sugar-cone molds, including the one shown here, and their associated syrup pots.[9] Faneuil Hall had been built on reclaimed land within Boston’s 1630 Town Dock, so these earlier artifacts suggest that a local Boston merchant used them to further refine the coarse Caribbean sugar being shipped to the city via Boston Harbor in the early eighteenth century (fig. 12). This same Town Dock was used as an auction site for recently arrived shipments of enslaved people until 1783, when slavery was abolished in Massachusetts.

Grace Parker’s Porringer

Charlestown’s rich clay deposits supported dozens of potters and a thriving earthenware industry from the mid-seventeenth century until the burning of the city by British soldiers during the Battle of Bunker Hill on June 17, 1775. Isaac Parker and his wife, Grace, founded a pottery works in 1714. After Isaac’s untimely death in 1742, Grace and her son, John, continued the business, experimenting with stoneware production until she died in 1754. Josiah Harris subsequently took over operations at the pottery until it was destroyed during the Battle of Bunker Hill in 1775.

The wares made by the Parkers and other Charlestown potters were highly regarded and collectively known as “Charlestown ware” in advertisements from Canada to South Carolina.[10]

In 1986 archaeologists excavating in advance of Boston’s Big Dig found the remains of the once-bustling pottery in the Charlestown neighborhood of Boston.[11] The Parkers had situated their home, warehouses, and kiln on a waterfront property, with the majority of the operation on a pier so their goods could be transported almost directly onto waiting ships. While the Parker kiln was never located and likely lost due to development, thousands of wasters, pieces of kiln furniture, and dozens of vessels were recovered from waste piles deposited in the docks adjacent to the Parker pier (fig. 13).

Some of the Parker redware was highly decorated in distinct scale motifs. A nearly complete porringer was found in a mid-eighteenth-century privy deposit at the Three Cranes Tavern, located across the street from the Parker pottery.[12] It matches decorated fragments from the Parker pottery site, and this style of slip decoration is found on a variety of forms, including pans, mugs, and chamber pots made during Grace Parker’s tenure as pottery owner.

Revolutionary Teapot

The teapot illustrated in figure 15 was recovered from a tavern privy in the Charlestown neighborhood of Boston. Creamware has a terminus post quem of 1762, the year Wedgwood is known to have first exported it to the colonies.[13] This teapot’s style and deep yellow color suggest that it was made during the early years of British creamware production, The privy was one of five associated with the colonial Three Cranes Tavern.[14] This particular one, Privy 2, was found with several burned beams covering the top of the privy deposit.

On June 17, 1775, in retaliation for the overnight and secret fortifications of Breed’s Hill by rebel troops, British troops stationed in Boston Harbor and the mainland of Boston fired upon the fortifications and also fired incendiary missiles at the nearby town of Charlestown, all of which by the end of the day had burned, including the Three Cranes Tavern and Privy 2. Given the temporal brackets of its deposition, this little imported English teapot may have seen the passing of the 1764 Sugar Act, the 1765 Stamp Act, and the 1773 Tea Act and Tea Party demonstration (fig. 16), all while likely sitting on the table of the Three Cranes Tavern among individuals discussing these events.

Domingo Williams Dish

The 1806 African Meeting House in Boston’s Beacon Hill neighborhood (fig. 17) is the oldest standing black church in the United States and serves as a reminder of the growth of community identity and the fight for civil rights and social equality of Boston’s African-American community. The building has been used as a meetinghouse, church, school, and rallying place for abolitionists such as Frederick Douglas and William Lloyd Garrison. Since 1975 a series of archaeological surveys has resulted in a remarkable assemblage of artifacts from this gathering place.[15]

Archaeologists recovered a surprising quantity of blue shell-edge pearlware (fig. 18) from the backyard of the Meeting House. The basement of the church was rented out to black residents, among them Domingo Williams, a well-known caterer, who lived there from 1819 to 1830. Williams serviced events at the homes of wealthy white Bostonians, providing the food and dinnerware, scheduling the entertainment, arranging decorations, and other party services. Archaeologists interpreted the presence of the numerous matching pearlware plates as Domingo’s catering set, which served double duty as both a part of his successful business and for community events held at the Meeting House. Domingo’s plate not only demonstrates his success as an entrepreneur, since maintaining a catering set would have included the expense of regular replacements as vessels were damaged or broken, but also the vibrancy of the black community in which he lived and worked.

Japanese Students’ Satsuma

Japanese ceramics influenced imported Chinese porcelains in the eighteenth century, specifically Imari, but they are rarely present in the archaeological record in America because Japan chose to isolate itself politically, socially, and economically from the outside world under a policy known as Sakako from 1633 to about 1868. In the 1850s U.S. Navy ships were granted limited access to ports for the first time; that access expanded, leading to the opening of Japan to the West in the late 1860s.

In 1870 Charles Dillaway, deacon of the First Church of Roxbury, a neighborhood of Boston, hosted four young Japanese men who traveled to the United States in one of the earliest cultural-exchange events between America and Japan (fig. 19). Dillaway taught and perhaps even housed the young men in his home, which was built in the 1740s and served as the parsonage for the church.[16]

Archaeologists working in the yard of the Dillaway-Thomas house, as it is known, recovered several unusual fragments of earthenware with raised enamel decoration known as moriage (fig. 20). While not initially cataloged as such nor recognized by the authors when first encountered in 2014, posting one of the ceramic fragments on social media immediately led to its identification as Satsuma ware (fig. 21). It is likely that these Satsuma ceramic fragments date to the period of the visit of the Japanese students in 1870 and represent a gift of a ceramic vessel, likely a vase, to Charles Dillaway from a grateful Japanese Embassy.

Industrial School Girls’ Doll Dishes

Established in 1854 by wealthy Bostonian women, the Dorchester Industrial School for Girls was intended to provide practical and marketable domestic-servant skills for young daughters of impoverished immigrants, or single parents, or those with developmental issues.[17] The school housed up to thirty girls at a time, aged eight to seventeen, who lived there year-round.

Dorchester Industrial represented several shifts in nineteenth-century ideology by wealthy Bostonian women, many of whom were well educated but struggled with Victorian norms that barred them from employment. These women recognized their financial ability to provide education and worked to create employment opportunities for less fortunate females by converting domestic labor into marketable jobs in the public sector. This early feminist movement resulted in a cultural shift in the understanding and acceptability of working women in the late Victorian period.[18]

The archaeological assemblage recovered from a privy behind Dorchester Industrial included a large quantity of domestic goods associated with the girls’ training to become domestic servants: sewing pins, tatting needles, sewing birds, and beads. The large quantity of dolls and doll tea sets probably indicates these were teaching tools, used to reinforce important lessons in the Victorian tea service of another social class (figs. 22, 23).

Dorchester Pottery Plymouth Rock Paperweight

In 1895 George Henderson opened a smooth-glaze stoneware factory in the Dorchester neighborhood of Boston. There he produced primarily custom-ordered and -designed commercial goods, avoiding competition with the local Dedham Pottery’s decorative stone wares. One of his greatest successes, which he patented in 1912, was a stoneware foot warmer.[19]

After George died in 1928, Charles and Ethel, his son and daughter-in-law, took over the business, which struggled due to a drop in industrial orders during the Great Depression. In the 1940s, the company began creating decorative housewares using traditional potting techniques—mustard-yellow and pale-blue allover decoration as well as hand-painted cobalt pinecones, ships, and fruit, which supplemented weakening industrial orders. Lura Woodside Watkins praised this twentieth-century pottery company for “its high standards of quality workmanship that characterizes the potteries of an earlier day.”[20]

The small paperweight of Plymouth Rock illustrated in figure 24 will win no beauty contests, but it demonstrates the transition of the nineteenth-century industrial stoneware industry toward a domestic consumer–based market in an effort to remain both relevant and profitable. The Dorchester Pottery Works closed in 1979. During the process of its designation as a Boston City Landmark, archaeologists surveyed the kiln and waster pile ahead of conversion of the building into a nonprofit space. Among the hundreds of recovered artifacts are this paperweight and other fragments of the Works’ production history, including kiln furniture, a partial foot warmer, a painted inkwell, and several partially burned daybooks (fig. 25).

Joseph M. Bagley, A History of Boston in 50 Artifacts (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England, 2016).

R. Scott Anderson, N. G. Miller, R. B. Davis, and R. E. Nelson, “Terrestrial Fossils in the Marine Presumpscot Formation: Implications for Late Wisconsinan Paleoenvironments and Isostatic Rebound along the Coast of Maine,” Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 27, no. 9 (1990): 1241–46.

Steven R. Pendery, Archaeological Survey of the Boston Common, Boston, Massachusetts (1988), report on file at the Massachusetts Historical Commission, Boston.

Steven R. Pendery, Russell Barber, Peter Bogucki, Penelope Lie, and David Singer, Phase III, Chelsea-Water Streets Connector Project, Charlestown, Massachusetts: Excavations at the Wapping Street and Maudlin Street Archaeological Districts: Final Report (1984), report on file at the Massachusetts Historical Commission, Boston.

Steven R. Pendery, “Consumer Behavior in Colonial Charlestown, Massachusetts, 1630–1760,” Historical Archaeology 26, no. 3 (1992): 57–72.

Lauren J. Cook and Joseph Balicki, Archaeological Data Recovery: The Paddy’s Alley and Cross Street Back Lot Sites (BOS-HA-12/13), Boston, Massachusetts (1998), 4 vols., report on file at the Massachusetts Historical Commission, Boston.

Lauren J. Cook, “‘Katherine Nanny, alias Naylor’: A Life in Puritan Boston,” Historical Archaeology 32, no. 1 (1998): 15–19.

Cook and Balicki, Archaeological Data Recovery.

Michael L. Alterman and Richard M. Affleck, Archeological Investigations at the Former Town Dock and Faneuil Hall, Boston National Historic Park, Boston, Massachusetts, 3 vols. (Silver Spring, Md.: Eastern Applied Archeology Center, National Park Service, Denver Service Center, 1999), report on file at the Massachusetts Historical Commission, Boston.

Lura Woodside Watkins, Early New England Potters and Their Wares (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1950).

Joan Gallagher, Laurie Boros, Joyce Fitzgerald, and Neill DePaoli, The Parker-Harris Pottery Site, Central Artery North Reconstruction Project, Archaeological Data Recovery, Charlestown, Massachusetts, vol. 3 (1992), report on file at the Massachusetts Historical Commission, Boston.

Joan Gallagher, Laurie Boros, Neill DePaoli, K. Ann Turner, and Joyce Fitzgerald, Archaeological Data Recovery, City Square Archaeological District, Central Artery North Reconstruction Project, Charlestown, Massachusetts, vol. 7 (1994), report on file at the Massachusetts Historical Commission, Boston.

George L. Miller and Robert Hunter, “How Creamware Got the Blues: The Origins of China Glaze and Pearlware,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2001), pp. 135–61.

Joan Gallagher, Laurie Boros, Neill DePaoli, K. Ann Turner, and Joyce Fitzgerald, Archaeological Data Recovery, City Square Archaeological District, Central Artery North Reconstruction Project, Charlestown, Massachusetts, vol. 7 (1994), file on report at the Massachusetts Historical Commission, Boston.

Beth Anne Bower, The African Meeting House, Boston, Massachusett: Summary Report of Archaeological Excavations, 1975–1986 (1986), report on file at the Massachusetts Historical Commission, Boston; David B. Landon, Investigating the Heart of a Community: Archaeological Investigations at the African Meeting House, Boston, Massachusetts (2007), Andrew Fiske Memorial Center for Archaeological Research Publications 2 (2007), report on file at the Massachusetts Historical Commission, Boston.

Duncan Ritchie and Beth P. Miller, Archaeological Investigations of the Prehistoric and Historic Period Components of the Dillaway-Thomas House Site, Roxbury Heritage State Park, Boston, Massachusetts (1994), report on file at the Massachusetts Historical Commission, Boston.

Annual Report of the Board of Managers of the Industrial School for Girls, in Dorchester: For the Year 1859 (Boston: printed by Prentiss and Sawyer for the Industrial School for Girls, 1860).

Suzanne M. Spencer-Wood, “A Survey of Domestic Reform Movement Sites in Boston and Cambridge, ca. 1865–1905,” Historical Archaeology 21, no. 2 (1987): 7–36.

City of Boston, “Dorchester Pottery Works, Boston Landmarks Commission Study Report, Petition #55” (1980), on file at the Boston Landmarks Commission.

Watkins, Early New England Potters and Their Wares, p. 91.