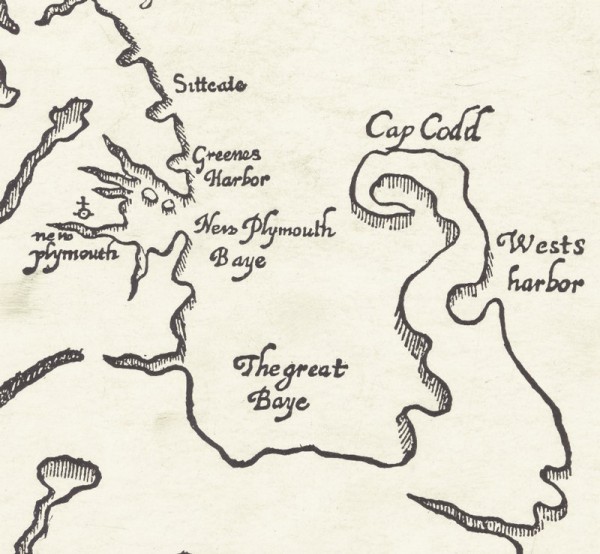

William Wood, The South part of New-England, as it is Planted this yeare, 1634 (detail), 1635. From William Wood, New Englands Prospect (London, 1634). (Courtesy, Boston Public Library.)

Pilgrim Hall, Plymouth, Massachusetts, 2016. (Photo, Steven Pendery.)

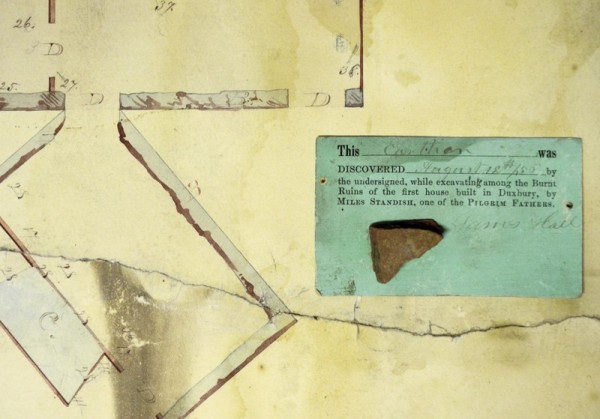

Portion of James Hall’s plan of the Miles Standish site (1856), and earthenware artifact tag from the site. Map overall 20 13/16 x 28 11/16". (Courtesy, Pilgrim Hall Museum; photo, Steven Pendery.)

Reconstructing the ca. 1621 Billington House at Plimoth Plantation in 1973. Foreground (left to right): James Deetz, Henry Hornblower, James Blogg, Henry Glassie. (Photo, Steven Pendery.)

Native American vessel, Late Woodland period, ca. 1400–1600. Low-fired earthenware. H. 12 3/16". (Courtesy, Massachusetts Archaeological Society; photo, Steven Pendery.) This reconstructed vessel with zone incised decoration, which is being held by David DeMello, was found at the Nemasket site in Middleborough, Massachusetts.

Pot or jar, Massachusetts, ca. 1650–1700. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 5 3/4". (Courtesy, Plimoth Plantation and Marshfield Historical Commission; photo, Steven Pendery.)

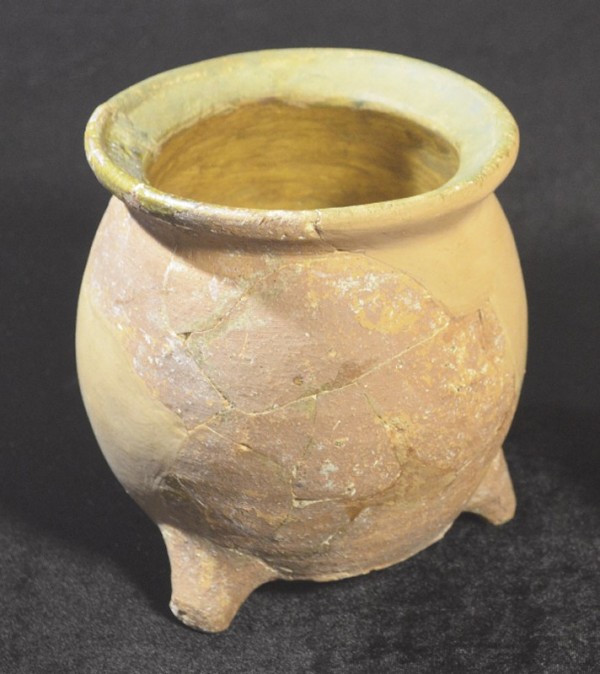

Pipkin, Bideford, Barnstaple, or Fremington, North Devon, England, ca. 1635–1650. Gravel-tempered earthenware. H. 6 3/8". (Courtesy, Plimoth Plantation; photo, Steven Pendery.)

Bellarmine, Frechen, Germany, possibly late sixteenth century. H. 8 1/16". (Courtesy, Plimoth Plantation; photo, Steven Pendery.) A fragment of a Bellarmine with a similar medallion was found in 2012 on the foreshore of the River Thames in London.

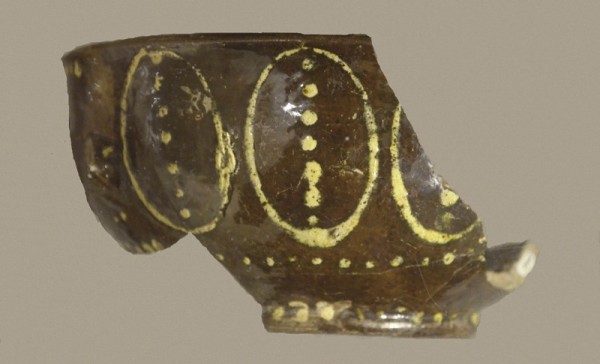

Bellarmine stoneware bottle fragments, ca. 1635–1675. L. of neck 2 3/4". (Courtesy, Plimoth Plantation; photo, Steven Pendery.)

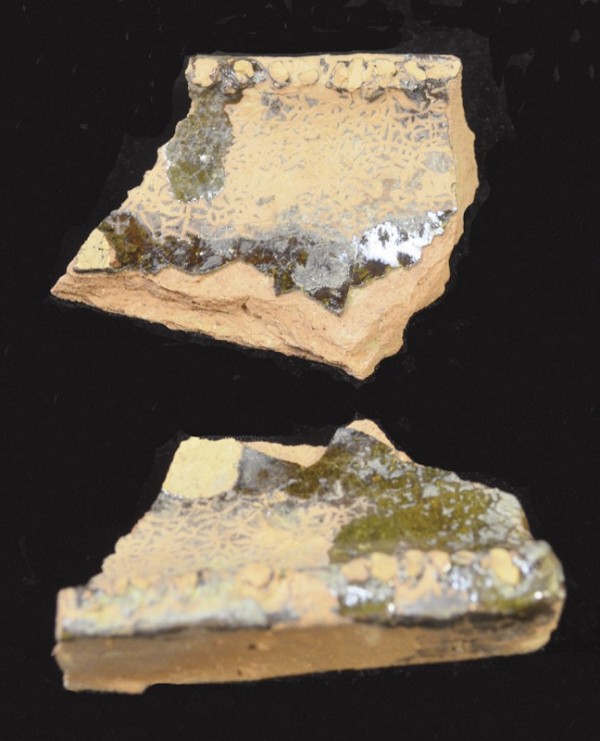

Bottle fragments, possibly Bessin-Cotentin, Lower Normandy, France, seventeenth century. Stoneware. (Courtesy, Plimoth Plantation and Marshfield Historical Commission; photo, Steven Pendery.)

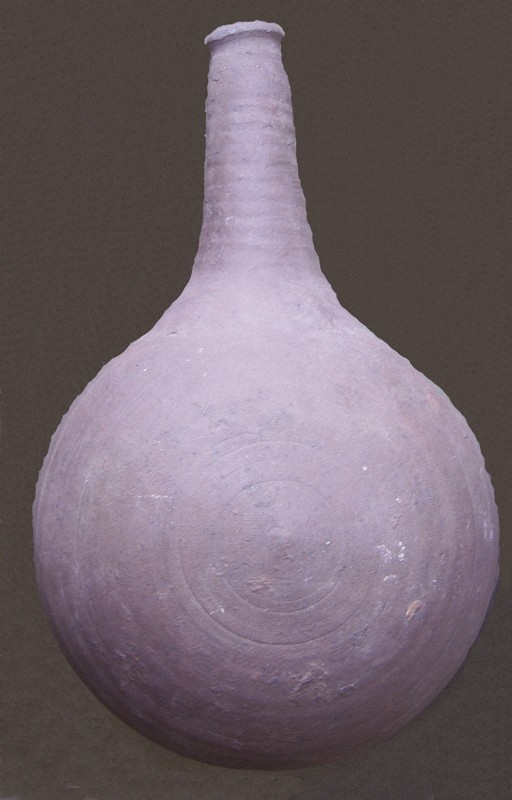

Bottle, Dieppe, France, early seventeenth century. Stoneware. H. 9 1/2". (Courtesy, Musée de Dieppe; photo, Steven Pendery.)

Salt, Southwark, London, England, ca. 1650–1680. White tin-glazed earthenware. H. 6". (Courtesy, Pilgrim Hall Museum.) Associated with the family of Mayflower passenger Edward Fuller.

Hispano-Moresque copper luster plate, probably Manises, Valencia, Spain, ca. 1650–1700. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 7". (Courtesy, Pilgrim Hall Museum; photo, Steven Pendery.)

Plate fragment, Portugal, seventeenth century. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 9/16". (Courtesy, Plimoth Plantation; photo, Steven Pendery.) Semicircular or floral decoration covered the area beneath the banded marley. This fragment was recovered from the ca. 1650–1700 Josiah Winslow site in Marshfield, Massachusetts.

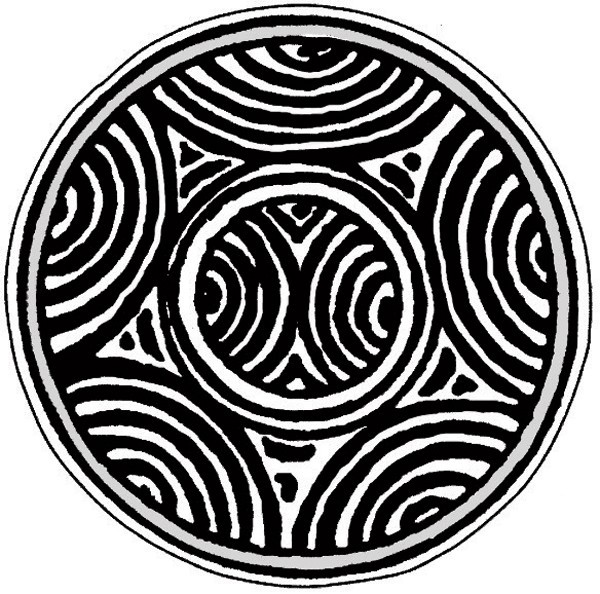

Semicircular design motif of a Portuguese faiança plate found in Brazil, most likely the same design as represented on the sherd illustrated in fig. 14. (Illustration by Steven Pendery.)

Porringer fragment, Massachusetts, ca. 1700. Slip-decorated red earthenware. H. 2 9/16". (Courtesy, National Park Service; photo, Steven Pendery.)

A selection of chamber pots from a ca. 1835 privy assemblage at site C13A in downtown Plymouth, Massachusetts. Foreground, delftware; center, redware; background, creamware. (Courtesy, Plimoth Plantation and Harold and Harriet Nathanson; photo, Steven Pendery.)

Plimoth Plantation curator Kate Ness examines vessels from a ca. 1835 privy fill excavated at Site C13A in downtown Plymouth, Massachusetts. (Courtesy, Plimoth Plantation and Harriet and Harold Nathanson; photo, Steven Pendery.)

Stilts or tripods, Stephen Bradford pottery, Kingston, Massachusetts, ca. 1837–1853. Earthenware. L. (right) 3 15/16". (Courtesy, Plimoth Plantation and Jones River Historical Society; photo, Steven Pendery.) These pieces, which were recovered in 1996, were used to support wares in the kiln.

Trough-shaped setting-tile fragments, Stephen Bradford pottery, Kingston, Massachusetts, ca. 1837–1853. Earthenware with patches of lead glaze. (Courtesy, Plimoth Plantation and Jones River Historical Society; photo, Steven Pendery.) Pans were nested vertically, with their rims set on the raised edge of the tile to prevent slippage and to control the flow of liquefied lead glaze.

Sugar drip jars, nineteenth-century. Earthenware. H. 19 11/16". (Courtesy, Plimoth Plantation; photo, Ted Avery.)

The eve of the 400th anniversary of the English settlement of Plymouth, Massachusetts, is an appropriate time to reflect on the history and meaning of its ceramics. The earthenware, stoneware, and porcelain objects presented in this article address both conventional and unconventional themes associated with Plymouth and its first Thanksgiving. These include the history of American historical archaeology, European and Native American interactions, diet, creolization, and the beginning of modern consumer behavior.

Plymouth was the setting of an important English plantation founded in 1620 about thirty-five miles due south of present-day Boston (fig. 1). Its settlers were English separatists known as Pilgrims, who had spent eleven years in exile in Holland before leaving England on the Mayflower for New England, to worship and work in peace.[1] Numerous Pilgrims died during the first winter even as the local Native Americans provided support and nutrition to the group. The survivors lived in a palisaded village with wood frame houses, a meetinghouse, and a fort.[2] In 1627 the settlers ventured out of the fortified enclosure to establish coastal farmsteads elsewhere in Plymouth and in today’s towns of Kingston, Marshfield, and Duxbury, sites that have yielded many of the ceramics discussed in this chapter. Other ceramics are from the urbanized center of Plymouth, from Wellfleet (provisioned from Plymouth), and from a Kingston pottery operated by a Pilgrim descendant.

Economic prosperity in nineteenth-century Massachusetts attracted foreign immigrants, a situation that triggered insecurity among the New England, “Yankee” families.[3] One tactic the Yankees used to maintain social legitimacy involved making explicit their family ties with Pilgrim founding fathers. Genealogical associations were formed, early houses were designated as historic landmarks, and Pilgrim Hall was founded in 1820 as America’s first museum (fig. 2). Two ceramics discussed in this article are heirloom objects that were donated to Pilgrim Hall by descendants eager to memorialize both their ancestors and themselves.

Archaeology played an important role in establishing genealogical ties. In 1856 James Hall excavated the Duxbury house site of his Pilgrim ancestor, Miles Standish, marking the first time in America that excavated artifacts were plotted on a site map (fig. 3).[4] In 1938 architect Sidney Strickland excavated the Pilgrim John Howland site in Kingston for Howland’s descendants. Academic interest in Plymouth sites began in 1940 with the excavation of the Edward Winslow site in Marshfield by undergraduate members of Harvard’s Excavator’s Club. Members Henry Hornblower and John Brewer excavated the RM Site, the seventeenth-century homesite of merchant William Clark, in Plymouth in 1940–42 and again in 1949. In 1957 Hornblower’s grandmother, Hattie, donated much of her own property along the Eel River to establish the Plimoth Plantation museum, where Pilgrim daily life is interpreted.[5]

In 1959 Harvard University graduate student James Deetz resumed excavations at the Howland site in Kingston. This was the first but certainly not the last colonial site excavated by Deetz, as during the 1960s he became a leading proponent of the emerging field of historical archaeology. He later served as assistant director of Plimoth Plantation while teaching at Brown University, which facilitated student involvement (including that of both authors) in Plymouth-area archaeology (fig. 4). Deetz’s special interest in ceramics led to his landmark article “Ceramics from Plymouth, 1635–1835,” which posited that ceramics exhibited a threefold division in time “corresponding to the three successive cultural systems in operation in New England (1620–1660, 1660–1760, 1760–1835).”[6] In light of this important study, Plymouth archaeology and ceramics assumed a global level of interest and significance.

The theme of initial contact between Native Americans and the Pilgrims is embedded in the First Thanksgiving story, but serious research on this topic began only recently. Native American pottery production in the Plymouth area endured for more than 3,000 years and ended about 300 years ago. English settlers who consumed Native American–prepared foodstuffs certainly may have used Native ceramic containers as well. Most Pilgrim archaeological sites of the first period (1620–1660) contain Native American shell-tempered pottery, which, like English gravel-tempered ware, is conducive for use as cooking pots. Because Native American–made colonoware (non-European colonial pottery made in European shapes) was commonly incorporated into colonial foodways elsewhere in the Americas, Pilgrim use of Native pottery needs additional study in this comparative context.

Creolization involves the blending of cultural traditions, especially in the area of foodways, where ceramics play an important role. The earliest colonial-period English potters were certainly influenced by a range of African, European, and Native American decorative traditions. To what extent does the earliest decorated New England pottery reflect those influences? Detailed work is needed to reconstruct entire vessel forms and to analyze their decoration, which will certainly add insight into the diversity of colonial New England’s cultural traditions.

Native American Pottery

“In the houses we found wooden Boules, Trayes & Dishes, Earthen Pots, Hand baskets made of Crab shells, wrought together. . . .”[7] Even before they reached Plymouth in November 1620, the Pilgrims had initially landed at Cape Cod, where they encountered Native American pottery while looting graves and exploring abandoned wigwams there. The earliest pottery known from the Plymouth area was made 3,000 years ago and is referred to as Vinette. Local clay was tempered with sand and later with pulverized shell. Coiling clay to form pots was introduced about 1,000 years ago, and added incised or impressed decoration was common. Pots were probably fired in shallow fire pits. The Late Woodland–period example from nearby Middleborough, shown in figure 5 and restored by William Fowler, has zoned incised decoration on the collar or neck and dates to about 1400–1600.

Native pots were used for storage, cooking, and ceremonial purposes. Pottery was also included as grave goods in Native American burials. Contact with Europeans led to the gradual replacement of Native pottery with European pottery and copper and brass cooking pots. While colonoware is rare in New England, the cooking pot is common to all cultures and each group could have used the other’s pots. Native ware is present at most early Pilgrim house sites, and Malcolm Watkins has noted some documentary references, such as the “Indian ware” listed in the 1666 inventory of Daniel Weld of Boston. Native pottery was also found in the mid-eighteenth-century well fill at the Daniel Bayley site in Newburyport.[8]

Locally Made Earthenware Pot

This restored red earthenware common pot from the Josiah Winslow site probably dates to the second half of the seventeenth century (fig. 6). In 1655 Josiah, a governor of Plymouth Colony, inherited the house of his father, Edward Winslow, who had been a three-term governor of the colony. The house was probably fortified during King Philip’s War (1675–1678) and continued to serve as a residence until 1699. The Winslow site was excavated by the Harvard Excavators Club in 1940–1943 and again in 1949.[9]

We have no record of a potter in early Plymouth, and it is likely that imported English earthenware filled its needs. The potter Philip Drinker settled in Charlestown in the Massachusetts Bay in 1635 and probably traded his wares as far south as Plymouth.[10] New England’s colonial potters mined surface deposits of glacial clay to produce both red earthenware pottery and bricks. Raw galena lead was dry sifted onto freshly turned earthenware vessels. Once dry, these ceramic wares were fired in wood-fired updraft kilns, producing lead-glazed red earthenware vessels commonly referred to as redware. Colonial-period redware pans were used to prepare dairy products and other food. A common pot was a multipurpose hollow container used mainly for storing preserved meat and other foodstuffs. During the seventeenth century, Native Americans gradually abandoned their traditional pottery in favor of locally made redwares, along with European copper and brass kettles.

North Devon Gravel-Tempered Pipkin

This pipkin was recovered at the Edward Winslow site in Plymouth, dating from 1635 to 1650 (fig. 7). The distinctive gravel inclusions of its clay body identify it as a product of one of the North Devon towns of Bideford, Barnstable, or Fremington.[11] The gravel temper provided strength to the highly plastic earthenware body, the interior surface of which, in this instance, was glazed with unrefined galena lead. This pipkin’s three-footed base indicates that it was used for cooking or for holding embers to provide warmth. This form is common in the Lowlands, and its presence in the west of England may reflect the immigration of Flemish potters to this area in the sixteenth century.[12]

Similar pots could have been produced in New England, raising the question of why coarse earthenware was imported in the first place. An answer may be found in the complex blend of kinship and seventeenth-century transatlantic trade practices. A strong correlation exists between the distribution of North Devon wares in colonial America and the trading activities of John Delbridge, an influential merchant of Barnstable. Delbridge promoted both trade and settlement in Bermuda, New England, and Virginia. In 1619, one year before the settlement of Plymouth, he sought rights in the fisheries off the coast of Cape Cod and probably helped settle the town of Barnstable, Massachusetts. Other North Devon merchants followed in the wake created by Delbridge and supplied key American colonies with coarse earthenware well into the eighteenth century.[13]

Bellarmine

Gray stoneware bottles sporting a human mask on the neck and one or more medallions on the body are known as bellarmines or greybeards, and are attributed to the village of Frechen near Cologne.[14] Typically, they are covered with an iron-oxide slip, which, when fired in a salt-glaze kiln, produces a mottled brown glaze. No examples dated later than 1699 have come to light, although similar undated bottles have been found in eighteenth-century contexts.[15] An intact, possibly late-sixteenth-century example from the museum collections of Plimoth Plantation is illustrated in figure 8. It is decorated with a somewhat comical mask on its neck and a medallion bearing an armorial.

Marley Brown iii noted a list of five “stone” jugs, two bottles, and one pot in a sample of Plymouth estate inventories.[16] The bellarmine fragments found at the RM Site in Plymouth illustrated in figure 9 appear to date to the first half of the seventeenth century, judging by the fine molding of the face and medallion. Such bottles may have served as containers for transporting and serving liquids such as spirits. Another possible use in evidence at some colonial sites is as “witch bottles,” which involved filling the bottles with pins and urine and burying them upside down near the threshold of a house to provide protection.[17]

Normandy Stoneware

Fragments of at least two Normandy stoneware bottles were recovered from the 1635–1650 Edward Winslow site (fig. 10). Although “Normany ware” is often attributed to the town of Martincamp in Upper Normandy, similar stoneware bottles were produced for export wherever suitable clay deposits were found.[18] The reddish fabric of these particular examples suggests an origin in the Bessin-Cotentin area of Lower Normandy.[19] Such bulbous bottles were made in two half spheres then joined at the side, leaving a vertical seam. The top was perforated and a conical neck was attached. A complete bottle found in Dieppe, France, is illustrated in figure 11. Such bottles were usually covered with wickerwork to help protect the vessels and to allow them to sit upright or to be suspended.

These thin-bodied bottles were exported in large numbers, apparently empty, to the British Isles. Examples still in their wicker covers were found in the 1545 wreck of the Mary Rose near Portsmouth.[20] Their occurrence in deposits from early Jamestown, Virginia, suggests they were used as flasks or canteens for military expeditions. The Edward Winslow house in Plymouth was converted for garrison use during King Phillip’s War (1675–1678), and these fragments might date to that period. Their presence reminds us of the extent to which the Atlantic world was a vast international emporium of consumer goods for the early colonies before the British Navigation Acts restricted colonial trade to the mother country in the third quarter of the seventeenth century.

Delft Salt

Were it not for what has survived in the ground, the role of the salt or saltcellar in the dining practices of the Pilgrims and their immediate descendants would have gone entirely unappreciated. The striking monochrome white example on display at Pilgrim Hall and associated with the family of Mayflower passenger Edward Fuller (fig. 12) resembles the vessel from a private collection in Virginia that prompted F. H. Garner and Michael Archer to reflect that “some of the most attractive delftware of this time was entirely unpainted. Such are the salts with these projecting arms. . . .”[21] A recently published Museum of London illustration of such forms, in biscuit, together with the separate ram’s horn or scroll finials, meant to be applied later, establishes their manufacture at the Rotherhithe Pothouse in Southwark during the period circa 1638–1684. Characterized as of the “waisted type,” these forms are not at all common at these early London-area delftware production sites. Likewise they are rarely found at early English domestic sites along the eastern seaboard.

Their presence on the dining tables of at least a few elite colonists in the seventeenth century, however, draws attention to the complexities of interpreting the place of ceramics in dining rituals rooted in the medieval courtly halls of Europe—complexities that are not fully captured in the Georgianization model set forth by James Deetz forty-five years ago.[22] Saltcellars like the one that passed down the Fuller line were copied from even more highly prized examples in silver, and were intended for several courses of an elaborate, formal meal. Contrary to Deetz’s original interpretation, such forms document the coexistence of communal and individualized relations with objects in the seventeenth-century dining setting.

Spanish Copper-Luster Decorated Plate

This seven-inch Hispano-Moresque plate in the collections of Pilgrim Hall has long been an object of interest to ceramic historians because of its unusual provenance (fig. 13).[23] It is probably from Manises in Valencia, Spain, and most likely dates to the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century.[24] It is covered overall with a cream-colored tin glaze and decorated front and back with copper-luster designs. This vessel is associated with the White family in Plymouth, which traces its ancestors back to Peregrine White, who was born on the Mayflower in Plymouth harbor in 1620. One of the few references to Spain in early Plymouth records mentions that colony treasurer Isaac Allerton sold a ship with its ordnance and fish cargo in Spain in 1632.[25] After1640, Massachusetts Bay merchants became active in transatlantic trade. A Charlestown, Massachusetts, merchant named Augustine Walker died in Bilbao, Spain, in 1635, where he was probably trading New England fish, salt, and lumber for Spanish wine, fruit, and consumer goods.[26]

Trade with the Iberian Peninsula and Spanish Caribbean introduced New England residents to the sophisticated ceramic arts of the western Mediterranean. The practice of using silver and copper stains on pottery dates back to the ninth century a.d. in the eastern Mediterranean, and was conveyed to Moorish Spain by the twelfth century. By the mid-fourteenth century the area of Valencia and the town of Manises had assumed a prominent position in luster ware production. The expulsion of Moors in 1610 contributed to the gradual decline in quality of Spanish luster wares.

Portuguese Tin-Glazed Earthenware

The rim fragment of a small plate (fig. 14) found at the 1650–1700 Josiah Winslow site in Marshfield is most likely a type of Portuguese tin-glazed earthenware known as faiança. The major production centers, among them Lisbon, Porto, and Coimbra, each used distinctive production methods and decoration.

The size of the sherd limits our ability to make a more specific identification, but the diverging brushstrokes of cobalt blue striking down from the rim hint at a common type of semicircular swag design (fig. 15).[27] During the early seventeenth century, Portuguese malequieros, producers of white (tin-glazed) ware, made close copies of Wan-Li Chinese porcelains entering the port of Lisbon. Later in the century those designs were blended with traditional Moorish designs and European motifs such as armorials and human figures. Both decorated and undecorated tin-glazed wares were shipped to the American colonies with Iberian produce that included wine and dried fruit, and exchanged for salt cod and a variety of wood products. As the trade-restricting British Navigation Acts were progressively enforced, Iberian ceramic imports to America diminished.

Archaeologist James Deetz asserted that the advent of matching sets of ceramic tableware in mid-eighteenth century Anglo-America was a consequence of the Georgianization of material life.[28] Conducting vessel-equivalent counts rather than sherd counts to analyze seventeenth-century ceramic assemblages, however, may reveal that matching sets of tin-glazed earthenware were used by affluent Plymouth households in dining and health-related activities a full century before the Georgian period (1714–1830) began.

Slip-Decorated Red Earthenware

This slip-decorated red earthenware porringer is a reconstructed vessel from the circa 1690–1740 Smith Tavern site in Wellfleet, Massachusetts, directly across Cape Cod Bay from Plymouth (fig. 16). The body is wheel-thrown and decorated with a white slip over which a lead glaze is applied. The closest known deposits of white-firing clay are found in the town of Gay Head/Aquinnah on Martha’s Vineyard, within the Wampanoag tribal reservation. Traditionally, redware was fired only once.

Massachusetts Bay slip-decorated redware appears to date no earlier than the last quarter of the seventeenth century. Potters produced it in response to local consumer interest in European decorated tableware, such as North Devon sgraffito and Metropolitan slipware. James Deetz characterized the second half of the seventeenth century as a period marked by the emergence of folk material-culture patterning. Early New England slipware reflects the process of creolization whereas in the eighteenth century there was deliberate imitation of specific English earthenware types such as Jackfield. Brushed decoration in fluid, abstract styles may have been inspired by decorated Iberian earthenware. Tighter geometric patterning, as seen in this example, may reflect a blend of Anglo, Native American, and African ceramic decorative traditions. This stands in sharp contrast to representational styles more commonly found farther south, in regions dominated by German and Moravian potters.

Plymouth C13A Ceramic Assemblages

By tradition, Leyden Street in today’s downtown Plymouth corresponds with the “fair street” of the village of Plymouth in 1620. In the early 1970s James Deetz conducted excavations at the back lot of Dexter’s Shoe Store on Leyden Street to determine whether Pilgrim sites could be detected. Testing revealed only a few fragments of seventeenth-century Border ware, but it unearthed spectacular evidence for late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century privy pits filled with refuse. The site, called C13A, contained Pit 1 dating to 1760, Feature 10 dating to 1800, and Pit 2 dating to 1835. These features provided Deetz with valuable information to formulate his three-period model for New England material culture.[29]

Given the quantity of plates and chamber pots in Pit 2, Deetz postulated his now-famous “one person/one dish/one chamber pot” model for symmetrical relationships in material culture of his third period, between 1760 and 1835 (fig. 17).[30] He notes that this time period coincides with the spread of Greek Revival architecture and suggests that a general reordering of the physical world of Americans occurred about fifty years after the American Revolution.[31] The sheer abundance of the Pit 2 assemblage captured in a 1973 Plimoth Plantation lab photograph is clearly seen in our 2016 photograph (fig. 18). Similar ceramic (and occasional glass) dumps from the 1820s and 1830s have since been reported at sites from Portsmouth, New Hampshire, to Flowerdew Hundred in Virginia.

Stephen Bradford Pottery Kiln Furniture, Kingston, Massachusetts

The town of Kingston, once part of Plymouth, was home to descendants of Pilgrim William Bradford. One of William’s sons, John Bradford, acquired a site on Wapping Road to make bricks and pottery around 1750. John’s sons Noah and Stephen became potters, and in 1798 Stephen acquired part of his father’s property, to which he soon added other parcels along the Jones River. Stephen was both a brickmaker and potter, and when he died in 1837 at age sixty-five his son Stephen continued in his trade until about 1854. In 1996 Steven Pendery conducted salvage excavations at the site along with Plimoth Plantation staff. We found a brick-lined clay cellar containing glazed pots, and 40,000 fragments were collected from across the site. A narrow range of vessel forms was represented, including pots, pans, jugs, and flowerpots as well as props or furniture used to stack the unfired earthenware in the kiln. Stilts supported delicate vessels, wedges braced the wares, and setting tiles with glaze troughs supported pans set upright in the kiln (figs. 19, 20).

The advent of industrial pottery production in Europe and America in the eighteenth century triggered the gradual demise of New England’s local potteries. Imported tableware and coarse earthenware could be obtained inexpensively, and stoneware and tin ware replaced certain redware forms. Local potters cut back on tableware items to focus on basic pots, pans, jugs, and flowerpots, and occasionally chimney safes and drainage tiles.

Parting Ways Site Earthenware Jars

Several years before the first phase of the colonoware debate was enjoined by archaeologists working in South Carolina, James Deetz suggested that two coarse earthenware jars of a type not previously recovered from New England sites were most likely produced in the Caribbean and had apparent significance through their association with people of African descent (fig. 21). In fact, Deetz used the two jars, which were discovered broken in place on a cellar floor at the settlement known as Parting Ways in the summer of 1975, to prompt his larger question regarding the degree to which what he labeled “African cultural survivals” could be recognized on sites occupied by enslaved Africans and their descendants—the question that is central to archaeological studies of the African diaspora to this day.[32] He also anticipated the discovery of coarse earthenware whose manufacture involved enslaved Africans themselves. A little more than a decade later, he was able to challenge the conventional wisdom of archaeologists working in Virginia with his contention that what had been identified as “colono-Indian ware” by Ivor Noël Hume twenty-five years earlier was, in fact, made by enslaved Africans.[33]

Finding a distinctive kind of earthenware in association with former slaves at Parting Ways, together with the subsequent arguments of Leland Ferguson and others for a ceramic “co-tradition” in South Carolina, encouraged Deetz to make the Virginia colonoware interpretation. In so doing, he was able to draw attention to the complexity of how this kind of pottery was produced, distributed, and used in the context of the daily lives of colonists throughout the New World. This line of interpretation, which originated with the two sugar jars from Parting Ways, has not only drawn critical attention to the differences to be seen in the foodways traditions of the different cultural groups caught up in the colonial process, but has also developed into a number of extremely nuanced and productive approaches to understanding the complex relationships between Native Americans and African Americans as their lives unfolded within various English colonial settlements along the eastern seaboard.[34]

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the following individuals and institutions for their support during the preparation of this article: Donna Curtin, Director, Pilgrim Hall; David DeMello, Director, Robbins Museum; Curtiss Hoffman, Bridgewater State University; Rob Hunter, Editor, Ceramics in America; Harriet Nathanson, Peabody, Massachusetts; Rebecca Piccirello, Curator, Pilgrim Hall; the Jones River Historical Society, Kingston, Massachusetts; and the Marshfield (Massachusetts) Historical Commission. In particular we thank Dr. Kate Ness, Curator, Plimoth Plantation, for providing access to the museum collections and archives.

A key source on the founding of Plymouth is the manuscript “Bradford’s History Of Plimoth Plantation,” now held by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts Library. An accurate transcription of the manuscript is William Bradford, Bradford’s History “Of Plimoth Plantation”: From the Original Manuscript (Boston: Wright & Potter, printed under the direction of the Secretary of the Commonwealth, 1898).

See George B. Cheever, ed., The Journal of the Pilgrims at Plymouth, in New England, in 1620: Reprinted from the Original Volume (New York: John Wiley, 1848). Also known as Mourt’s Relation, this account of the Pilgrims between 1620 and 1622 was probably authored by Edward Winslow and William Bradford.

Within New England itself, the term Yankee refers specifically to old-stock New Englanders of English descent.

James Deetz, In Small Things Forgotten: An Archaeology of Early American Life, exp. and rev. ed. (New York: Anchor Books, 1996), pp. 39–41.

An excellent summary of the history of the Plimoth Plantation museum is James W. Baker, Plimoth Plantation, Fifty Years of Living History (Plymouth, Mass.: Plimoth Plantation, 1997).

James F. Deetz, “Ceramics from Plymouth, 1635–1835: The Archaeological Evidence,” in Ceramics in America, Winterthur Conference Report 1972, edited by Ian M. G. Quimby (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1973), pp. 15–40.

Cheever, Journal of the Pilgrims at Plymouth, p. 39.

C. Malcolm Watkins, “Ceramics in the Seventeenth-Century English Colonies,” Arts of the Anglo-American Community in the Seventeenth Century, Winterthur Conference Report 1974, edited by Ian M. G. Quimby (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1975), pp. 275–99.

James Deetz and Patricia E. Scott Deetz, The Times of Their Lives: Life, Love, and Death in Plymouth Colony (New York: W. H. Freeman, 2000), pp. 245–46.

Lura Woodside Watkins, Early New England Potters and Their Wares (1950; reprint, [Hamden, Conn.]: Archon Books, 1968), pp. 16, 19.

Alison Grant, North Devon Pottery: The Seventeenth Century ([Exeter, U.K.]: University of Exeter, 1983), p. 40.

C. Malcolm Watkins, North Devon Pottery and Its Export to America in the Seventeenth Century, United States National Museum Bulletin 225 (Washington, D.C.: [Smithsonian Institution], 1960).

Grant, North Devon Pottery, pp. 114–28.

Ivor Noël Hume, If These Pots Could Talk: Collecting 2,000 Years of British Household Pottery (Milwaukee, Wisc.: Chipstone Foundation, 2001), p. 118.

Ivor Noël Hume, A Guide to Artifacts of Colonial America (1969; reprint, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1974), p. 57.

Marley R. Brown III, “Ceramics from Plymouth, 1621–1800: The Documentary Record,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Ian M. G. Quimby (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1973), p. 44.

Deetz and Deetz, Times of Their Lives, p. 92.

Pierre Ickowicz, “Martincamp Ware: A Problem of Attribution,” Medieval Ceramics 17 (1993): 51–60.

Jean-Pierre Chrestien and Daniel Dufournier, “French Stoneware in North-Eastern North America,” in Trade and Discovery: The Scientific Study of Artefacts from Post-Medieval Europe and Beyond, British Museum Occasional Paper 109, edited by Duncan R. Hook and David R. M. Gaimster (London: British Museum, 1995), pp. 91–103.

Duncan H. Brown and Robert Thomson, “Pottery Vessels,” in Before the Mast: Life and Death Aboard the Mary Rose, edited by Julie Gardiner with Michael J. Allen (Portsmouth: The Mary Rose Trust, 2005), pp. 462–67.

Frederick Horace Garner and Michael Archer, English Delftware, 2nd enl. and rev. ed. (London: Faber, 1972), p. 15 and pl. 27B

Kieron Tyler, Ian Betts, and Roy Stephenson, London’s Delftware Industry: The Tin-glazed Pottery Industries of Southwark and Lambeth (London: Museum of London Archaeology Service, 2008), pp. 63, 69, 82, 83.

Wendy Cooper, “Dish,” in Jonathan L. Fairbanks and Robert Trent, eds., New England Begins: The Seventeenth Century, exh. cat. (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1982), 3:395.

María Antonia Casanovas, “Ceramics in Domestic Life in Spain,” Cerámica y Cultura: The Story of Spanish and Mexican Mayólica, edited by Robin Farwell Gavin, Donna Pierce, and Alfonso Pleguezuelo Hernández, exh. cat. (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2003), pp. 54, 58.

Bradford, Bradford’s History “Of Plimoth Plantation,” p. 358.

Steven R. Pendery, “Portuguese Tin-Glazed Earthenware in Seventeenth-Century New England: A Preliminary Study,” Historical Archaeology 33, no. 4 (1999): 62.

Ibid., fig. 3J.

Deetz, In Small Things Forgotten, pp. 62–64.

Deetz, “Ceramics from Plymouth,” fig. 1 and table 1.

Deetz, In Small Things Forgotten, pp. 84, 86.

James Deetz, Flowerdew Hundred: The Archaeology of a Virginia Plantation, 1619–1864 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1993), pp. 115–35.

Deetz, In Small Things Forgotten, pp. 199–201.

James Deetz, “American Historical Archaeology: Methods and Results,” Science 239, no. 4838 (1988): 365–67.

Charles R. Cobb and Chester B. DePratter, “Multisited Research on Colonowares and the Paradox of Globalization,” American Anthropologist 114, no. 3 (2012): 446–61.