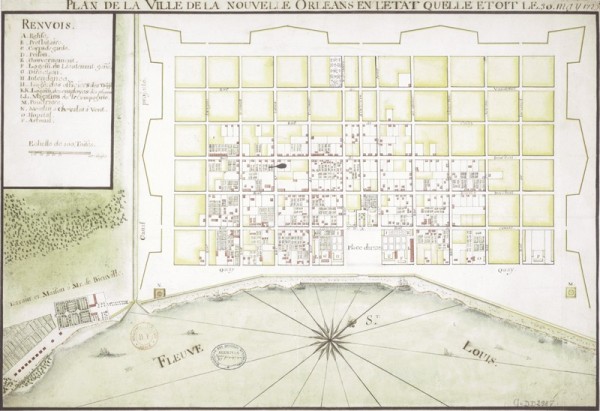

Plan de la ville Nouvelle Orléans en l’etat quelle étoit le 30 May 1725, probably New Orleans, Louisiana, or France, 1725. 17 1/2 x 25 3/16". (Courtesy, Bibliothèque nationale de France, FRBNF40608362.)

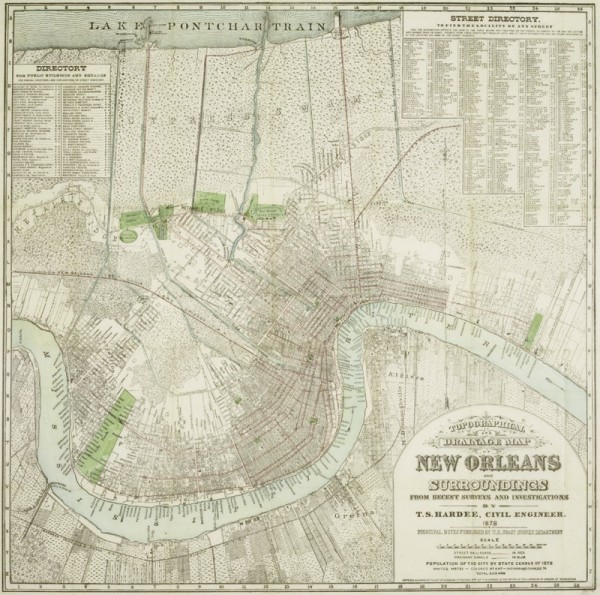

Thomas Sydenham Hardee (1832–1880), Topographic and Drainage Map of New Orleans and Surroundings, ca. 1877. Lithograph with watercolor. 33 5/8 x 32 5/8". (Courtesy, The Historic New Orleans Collection, 00.34 a,b.)

Plate fragment, France, first half of eighteenth century. Tin-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Dr. Shannon Dawdy, University of Chicago; photo, Adela Amaral.) This piece, shown in situ, was recovered during excavation at St. Anthony’s Garden, New Orleans, Louisiana.

Jug, Rouen, France, ca. 1750–1770. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 8". (Courtesy, University of New Orleans Archaeology Lab; photo, D. Ryan Gray.)

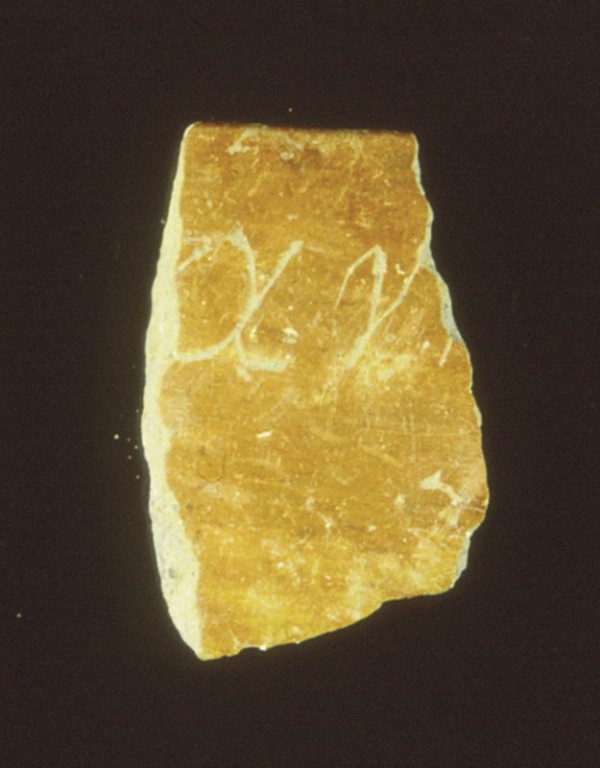

Pipe, Louisiana, ca. 1760–1780. Low-fired earthenware with sandy temper. (Courtesy, University of New Orleans Archaeology Lab; photo, D. Ryan Gray.)

The Black Men of Labor organization is followed by the Treme Brass Band, which is leading a second line of the procession starting at St. Augustine Catholic Church in the Treme on April 15, 2015, for the reburial of human remains recovered from the St. Peter Street Cemetery. (Courtesy, New Orleans Advocate; photo, Eliot Kamenitz.)

Fieldwork by Greater New Orleans Archaeology Program at St. Augustine site, Morand-Tremé Plantation, 1999. (Courtesy, University of New Orleans Archaeology Lab; photo, Christopher Matthews.)

Bowl fragment, Louisiana, eighteenth century. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Greater New Orleans Archaeology Program; photo, Christopher Matthews.)

Punch bowls and mug fragments, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1780–1800. China-glaze earthenware D. of bowl (top center) 4 1/2". (Courtesy, University of New Orleans Archaeology Lab; photo, D. Ryan Gray.)

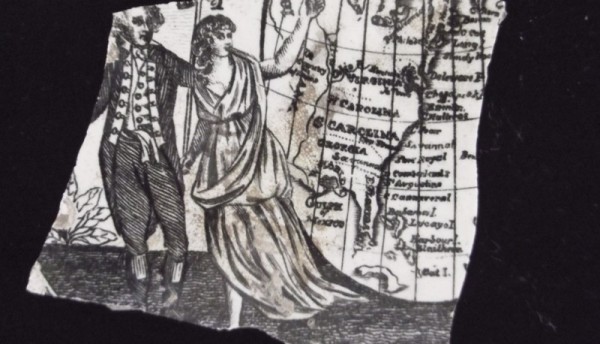

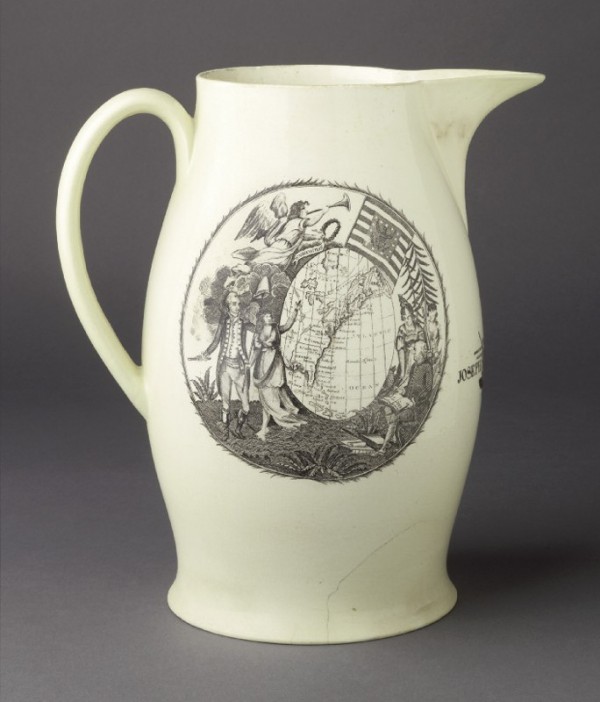

Jug fragment, probably Herculaneum Pottery, Liverpool, England, ca. 1800–1810. Creamware with black transfer print. (Courtesy, University of New Orleans Archaeology Lab; photo, D. Ryan Gray.) This jug fragment was recovered from 810 Royal Street, New Orleans, Louisiana.

Jug, probably Herculaneum Pottery, Liverpool, England, ca. 1800–1810. Creamware with black transfer print. H. 11 1/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum Collection, 2009.0021.010.)

Rouge pots, probably Moustiers, France, late eighteenth or early nineteenth century. Tin-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Historic New Orleans Collection.) These examples were recovered from excavations at 535 Conti Street, New Orleans, Louisiana. Such rouge and galley pots with monochrome green and blue exteriors are found throughout the Mississippi Valley, and date even into the early twentieth century.

Rouge pot, probably Moustiers, France, second half of nineteenth century. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 2". Inscribed: “GELLE Freres,/Parfrs Brevete line/dex vieux Augustins/a Paris.” (Courtesy, University of New Orleans Archaeology Lab; photo, D. Ryan Gray.) Faience rouge pots from the late nineteenth century often have the printed marks of make-up and perfume distributors. This example, recovered from excavations at Square 130 of the Iberville Housing Projects, came from a household in the neighborhood that became the Storyville red-light district (ca. 1898–1917).

(clockwise) Cups, wash basin, and chamber pot, Joseph Heath and Company, Tunstall, England, ca. 1828–1841. Whiteware. D. of basin 13 1/2". (Courtesy, Earth Search, Inc.; photo, D. Ryan Gray.) Transfer-printed decoration of “The Residence of the Late Richard Jordan, New Jersey”; these pieces were recovered from a privy at 923 Magazine Street, New Orleans, Louisiana.

Details of the transfer print, printed mark, and impressed pinwheel mark on the reverse of the basin and chamber pot illustrated in fig. 14. The pinwheel mark sometimes occurs along with a small printed “H” mark, presumably for Heath. The third example here is another transfer-printed vessel attributable to the Heath pottery.

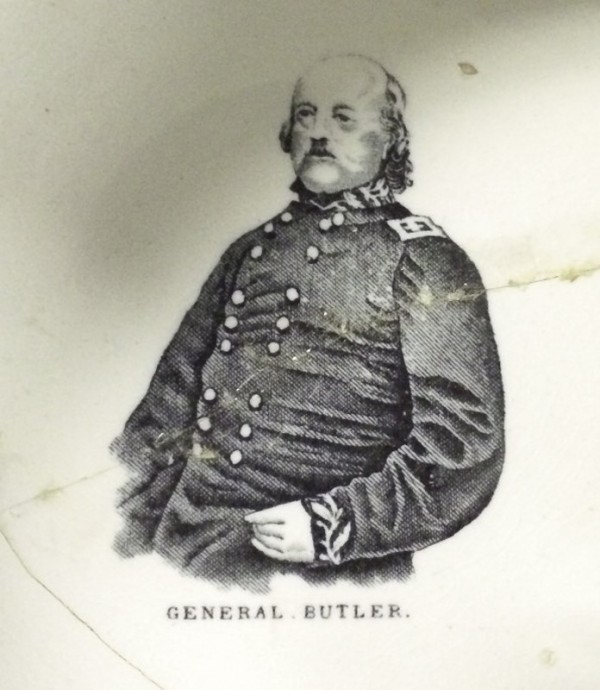

Chamber pot, England, late nineteenth century. Whiteware with transfer print of General Benjamin Butler. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery, Alabama.)

Detail of the transfer print inside the chamber pot illustrated in fig. 16.

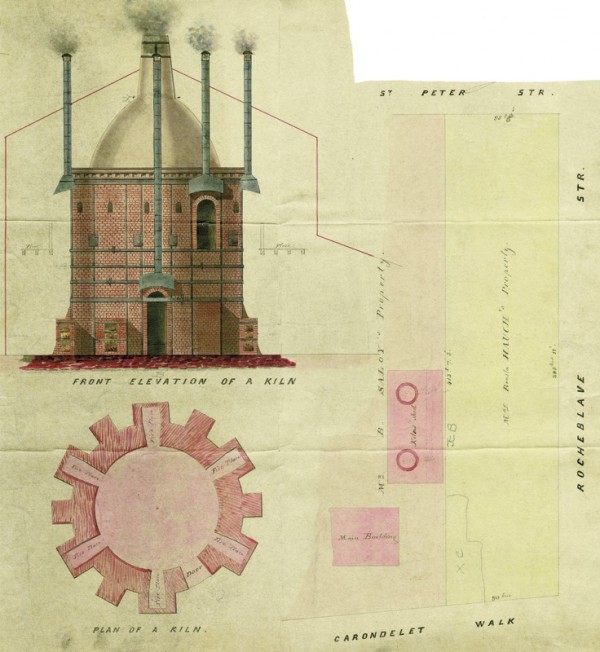

Plan showing the adjoining properties of Mr. Bertrand Saloy and Mrs. B. Hausch by St. Peter Street, Rocheblave Street, and Carondelet Walk, 1880–1885. Ink and watercolor on paper. 19 1/4 x 17 7/8". (Courtesy, Historic New Orleans Collection.)

Wasters and examples of wares, Lucien Gex Pottery, New Orleans, Louisiana, ca. 1890. Earthenware and stoneware, some fragments with remnants of Albany-type slip. (Courtesy, Earth Search, Inc.; photo, D. Ryan Gray.)

Kiln furniture and test firings, Lucien Gex Pottery, New Orleans, Louisiana, ca. 1890. (Courtesy, Earth Search, Inc.; photo, D. Ryan Gray.)

Olla, Zuni Pueblo, ca. 1890s. Earthenware with polychrome hand-painting. H. 10 1/2". (Courtesy, Earth Search, Inc.; photo, D. Ryan Gray.)

Big Chiefs Tyrone Casby (Mohawk Hunters), Cyril Green (Black Seminoles), and Darin Perry (Wild Red Flame) at a memorial gathering of the Chiefs of the Nation on the fifth anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, organized by New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu at the Mahalia Jackson Theater, New Orleans, 2010. (Photo, Jeffrey Ehrenreich.)

Summer 2013 excavations by the University of New Orleans field school in historical archaeology at Iberville Housing Projects, former location of “Storyville” red-light district, New Orleans, Louisiana. (Photo, D. Ryan Gray.)

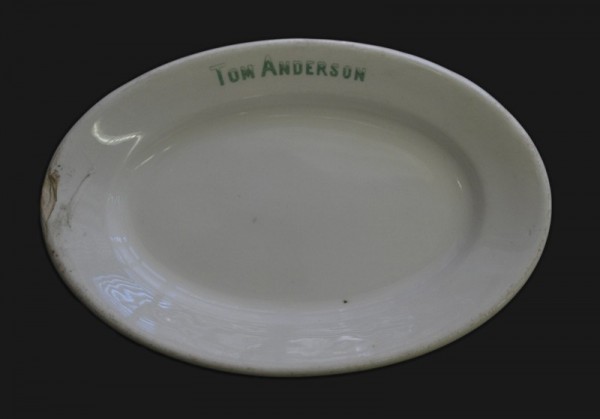

Platter, America, ca. 1898–1917. Porcelaneous stoneware. D. 10 1/2". Overglaze-printed “TOM ANDERSON”; unidentified mark impressed on base. (Courtesy, New Orleans Jazz Club Collections of the Louisiana State Museum; photo, D. Ryan Gray.) Tom Anderson, sometimes referred to as the unofficial mayor of Storyville, operated a saloon and restaurant on Basin Street, the location of some of the district's most famous brothels.

Ring holder, England, ca. 1890. Unglazed porcelain with unidentified registry mark. H. 6 3/4". (Courtesy, University of New Orleans Archaeology Lab; photo, D. Ryan Gray.)

In 2018 the tricentennial of the founding of New Orleans will undoubtedly be welcomed with a great deal of fanfare. After all, less than a decade and a half ago there was widespread speculation as to whether the city could be sustained. Hurricane Katrina and the engineering failures that followed it had devastated the area, leaving vast swaths of the city under water, and inept responses at all levels of government turned this disaster into a tragedy of epic proportions. The “City that Care Forgot” had been exposed, revealed as a place that was still, even in 2005, separate and unequal.[1] Now, by some accounts, the city is thriving once again. Tourism has returned in force to the Vieux Carré (or French Quarter) and the Garden District, and historic riverfront neighborhoods are flourishing. A boom in film production has attracted an influx of young professionals and artists, and property values have been inflated by the short-term rental industry. Large-scale redevelopments have appeared all around the city, and work on infrastructure clogs traffic uptown and downtown. Of course, cities—dense, heterogeneous, chaotic—are often sites of conflict, and what these developments mean for the character of New Orleans is hotly debated. Many locals fear that gentrification, changing demographics, and persistent racial inequality are diluting the very essence of the city.

This essence has given New Orleans a unique place in America’s imagination, as wild, licentious, and roguish, almost since it was incorporated into the growing nation.[2] The city’s origins were modest enough. Clearing the land began in 1718, relatively late in America’s colonial history, when Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville, then commandant of the French Louisiana colony, established a settlement along an old portage shown to his brother, Pierre Le Moyne, Sieur d’Iberville, by a Bayogoula Indian guide years earlier. A trickle of European settlers had arrived earlier in the century, but the founding of New Orleans represented a visible, permanent presence and an attempt to manufacture a town on principles of metropolitan order from what had been wilderness (fig. 1).[3]

In its French era (lasting until 1769), New Orleans remained an underdeveloped backwater, a product of continual cultural negotiation between isolated Euroamerican settlers, Native American tribes, and enslaved Africans.[4] In the era of Spanish colonial rule, which ended in 1802, the city’s population of free people of color grew rapidly while the city as a whole grew slowly, a consequence of the liberal manumission policies of the Spanish crown.[5] The physical appearance of the city was transformed radically in the latter part of the eighteenth century, when two fires, in 1788 and 1794, destroyed most of the city; the so-called French Quarter of today is almost entirely a product of the Spanish and American eras. By the time of the first American census in 1810, there were slightly more than 6,000 free whites, nearly 6,000 slaves, and 5,000 free people of color.[6]

During the American period, the shift in Louisiana to large-scale plantation agriculture, particularly sugar, had dramatic effects on the city (fig. 2). It became one of the great port cities of the country, allowing some to accumulate enormous wealth at the expense of profound suffering for others, as New Orleans became one of the most important markets for slave traders in the antebellum South.[7] In the period after Emancipation, the city would become increasingly divided by race, with the patterns of segregation that were revealed during Hurricane Katrina becoming the norm of the urban landscape.[8] Despite this, New Orleans also became home to a vibrant “Creole” culture, expressed in food, in music, in visual arts and performance, and in architecture, blending influences from Europe, from Africa, and from indigenous America to create something new.[9]

So what does all of this have to with the history of ceramics in the city, and with the ceramic artifacts listed here? New Orleans is not particularly known for its ceramic industry, and few of the examples here would qualify alone as masterpieces of American pottery. However, these items tell a story of New Orleans from its underside: a neglected colonial experiment that came to epitomize the luxury of a slave society, a place where sexuality and racial ambiguity were commercialized and celebrated, and a city whose gray areas and disorderly margins allowed for the birth of a special blend of cultures that was uniquely American.

Polychrome Hand-painted Faience from the French Quarter and the Tremé, Eighteenth Century

Intact archaeological deposits dating to the early part of the French Colonial era are relatively rare in New Orleans, even though much of the historical archaeology done in the city prior to the 1980s was focused on this period.[10] For the most part, the oldest parts of the city are concentrated along the high ground of the natural levee of the Mississippi River. As this well-drained land is very desirable in the low-lying alluvial fan of the delta, it remains densely developed, making it difficult to access anything that might be preserved beneath the contemporary landscape.[11] French tin-glazed pottery (or faience) and glazed coarse earthenware, especially the green-glazed wares associated with the potteries of the Saintonge region, dominate the assemblages from the French period.[12]

The most common varieties of faience found in New Orleans have relatively simple hand-painted decoration, often in monochrome blue or in blue highlighted with black. The soft earthenware fabric of this pottery is not very durable, especially in the dense clays that comprise many early colonial-era deposits in the city, so examples are often highly fragmented, like the polychrome plate from St. Anthony’s Garden, just behind St. Louis Cathedral, illustrated in figure 3. It was recovered in association with a circa 1730–1750 fire ring thought to mark the location of an informal market.[13] Faience continued in use in New Orleans long after Louisiana was no longer a French colony. The vessel pictured in figure 4, recently excavated from a trench associated with late-eighteenth-century plantation development at the edge of the city, is truly exceptional, both for its figural decoration and its state of preservation.[14]

Clay Pipe Bowl from St. Peter Street Cemetery, New Orleans, Louisiana, Eighteenth Century

“Colonoware” vessels have been a hotly contested subject in the eastern part of North America, with much of the debate centering on the question of African influence in their manufacture.[15] Given the substantial African presence and the vibrant African-American culture of New Orleans, it is somewhat surprising that colonoware is only rarely mentioned in Louisiana.[16] While colonial-era sites frequently contain small quantities of low-fired hand-built earthenwares, most of these are consistent with indigenous pottery traditions, and they are usually assumed to be the result of interactions with Native tribes. True colono-type vessels, with distinctive forms and decorations, at one time seemed practically nonexistent in the area.

Recent discoveries are challenging this view, and now some older collections are being reexamined in this light, with preliminary results showing considerable variability in sources for hand-built earthenware from New Orleans sites.[17] The low-fired, hand-modeled clay pipe with lightly incised or peck-marked decoration illustrated in figure 5 is a particularly distinctive example that could be considered a colonoware. It was recovered from the colonial-era St. Peter Street Cemetery, interred with a man of African descent, probably as part of the contents of a pouch containing flints, an animal tooth, and copper wire. Such a pouch or bundle could have meanings in both Native and African cultural traditions, and the style of the pipe has analogs in both.[18] This item has now been reinterred with the individual with whom it was buried, part of a public ceremony in which the remains of at least fourteen other individuals were returned to consecrated ground after their excavation (fig. 6).

Native Red-Slipped Vessel with Letters Inscribed in Brim from Morand-Tremé Plantation, Eighteenth Century

The Tremé has become synonymous with the musical culture of New Orleans, and as one of the city’s first creole faubourgs (similar to a suburb), it has a rich historical legacy as well.[19] The residential neighborhood was carved out of a colonial-era plantation tract around 1810, with the venerable St. Augustine Catholic Church now standing alongside the site of the former plantation house. Excavations at the churchyard in 1999 by the now-defunct Greater New Orleans Archaeology Program located stratified deposits associated with the plantation, including a large quantity of Native American–made ceramic wares dating from the mid-eighteenth century (fig. 7). The most common vessel forms among these wares were open bowls, which would not have been very well suited to transporting or storing food or liquids. This pattern has been noted at many other sites in the city as well, and the occurrence of these vessels might relate to the formation of reciprocal relationships through gift exchange.[20]

A fragment of a red-slipped bowl from the Tremé Plantation site, likely of Native manufacture, had the letters X and Y scratched into the brim after firing (fig. 8). Presumably the letters were part of a complete alphabet encircling the vessel’s opening and were meant to instruct, like the alphabet plates of the nineteenth century. A vessel like this typifies the emergent “Creole” culture of New Orleans.[21] The importance of the Native American heritage of the city is celebrated in African-American cultural traditions today, particularly that of the Mardi Gras Indians, parading groups known for their elaborate beaded costumes (see fig. 22).[22] Unfortunately, almost the entirety of the collection of materials from the St. Augustine excavations is now lost, unintentionally discarded with debris from Hurricane Katrina.

English Creamware and Pearlware Vessels

The shift to Spanish dominion in New Orleans was completed in 1769, and although the quantity of Spanish majolica does increase in this era, the period is marked much more by an influx of English pottery. The city was devastated by two fires, in 1788 and 1794, and the difference in assemblages from levels associated with these fires is drastic, with English creamware most numerous in those from 1788 and pearlware predominant in those from 1794. Trade with England was formally restricted in the Spanish colonies in much of this time, so the prevalence of English wares has been interpreted by some as evidence of illicit trade and smuggling. While this assumption may be a stretch, it is clear that New Orleans was being integrated into the same commercial networks as the colonies to the east. This process would be completed with the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, after a brief period of resumed but nominal French control.[23] The Americanization of the city was an occasionally bumpy process, and for a time in the antebellum there were separate city governments, one for the old “Creole” downtown municipalities and one for the newly forming American sector uptown.

Clear signs of the Anglicization of the city can be seen in a unique assemblage from the French Quarter, deposited in a brief span in the latter part of the 1790s and recovered after a catastrophic building collapse in 2013 left the lot at 810 Royal Street accessible for archaeological investigations. The assemblage contains a diverse array of English creamware and pearlware, much of the latter of the “China glaze” blue hand-painted variety (fig. 9). It is marked in particular by the number of vessels of Liverpool creamware with black transfer-printed designs, including multiple examples with a patriotic scene of George Washington and Lady Liberty alongside a map of the newly independent United States (figs. 10, 11). These vessels—English pottery produced for an American market, found in Spanish territory in a city that was still, ostensibly, culturally French—typify the material flux in New Orleans society in those years.[24]

Tin-Glazed and Enameled Rouge Pots from the Rising Sun Hotel

After the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, settlers from throughout the United States moved to New Orleans seeking to make their fortunes. By 1820 it was the fifth largest city in the country, with a population of 41,000, more than half of whom were people of color, both enslaved and free. The residents of the expanding American sector of the city ranged from the wealthy elite who dealt in the export of plantation commodities to rough-hewn “Kaintuck” flatboatmen who transported wares downriver and then populated the barrooms, billiard halls, and gambling dives of the riverfront and backswamp.

The antebellum saw the emergence of some of the city’s first “tenderloins” (vice districts), cementing its association with debauchery in the public imagination. Perhaps nowhere is this evinced more than in the fascination with the song “House of the Rising Sun,” made popular by Eric Burdon and the Animals in the 1960s.[25] While the song itself likely has its roots in English balladry, archaeological excavations in 2005 at the site of the Rising Sun Hotel at 535 Conti Street in the French Quarter revealed a unique intersection of historical legend and material culture.[26] Archaeologists recovered a number of fragments of faience rouge pots, burned and shattered in the 1822 fire that destroyed the hotel (fig. 12). While there was no way to determine for certain if this was the Rising Sun referred to in the song, or even if the location was a brothel, the concentration of cosmetic jars suggests an association with commercial sex. Even more so, it speaks to the city’s emerging notoriety as a place where “Frenchness” was commodified and linked to the illicit (fig. 13).[27]

Collection of Whiteware: Washbasin, Chamber Pots, and Other Vessels with “Richard Jordan” Transfer Print

By 1860 New Orleans was a booming port metropolis whose population of nearly 175,000 was expanded by waves of Irish and German immigrants. While these antebellum years have been marketed as a “Golden Age,” the city’s wealth was generated from the labor of the enslaved. Life for them and for the immigrant poor alike was harsh and oppressive. Regular bouts of epidemic disease, particularly yellow fever, were a near constant hazard. As the city grew, health became an increasing concern for city authorities, but little action was taken to improve sanitary conditions until the Union occupation during the Civil War.

Given this context, it is somewhat surprising that one of the most widely reported transfer-printed patterns from the late antebellum found archaeologically in the city is “The Residence of the Late Richard Jordan, New Jersey,” commonly attributed to the Staffordshire pottery of Joseph Heath and Company (ca. 1828–1841) of Tunstall, England.[28] The bucolic scene, based on an engraving of the eponymous, widely traveled abolitionist Quaker minister (1756–1826), was commissioned before his death (figs. 14, 15).[29] While the design’s popularity in the Northeast may have been related to Jordan’s antislavery sentiments, it is so widespread in antebellum New Orleans (including in contexts associated with slave-holding households) that it seems unlikely that this was the primary message of the design. Rather, the imagery could evoke the order and hygiene of an idyllic rural setting as a contrast to the chaos of city life for the dominant class, even as it carried a quiet message of resistance to slavery for others.

“Beast Butler” Chamber Pot

Louisiana seceded from the Union in 1861, joining the other Southern states in defending the institution of slavery. New Orleans, the largest city in the Confederacy at the time, was occupied by Union forces relatively quickly and with little resistance, sparing it from sweeping physical destruction. The next years in the city would be tense, characterized by riots and street violence, with the so-called Battle of Liberty Place in 1874 ending Reconstruction in Louisiana and marking the restoration of white supremacist rule. The 1897 Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court decision effectively legalized segregation, setting the stage for a civil rights struggle that is still contentious in the city of New Orleans.[30]

One of the most noted artifacts ostensibly associated with the Civil War in Louisiana is said to have originated in New Orleans during the period of Union occupation. On May 1, 1862, Major General Benjamin Butler officially took possession of the city as military governor. He was soon vilified as the “Beast Butler” by Confederate sympathizers, particularly after his General Order No. 28, which allowed women who disrespected Union soldiers in the streets to be considered prostitutes. The hatred of Butler is said to have been so extreme that his likeness was printed inside chamber pots as a form of protest (figs. 16, 17). This story has become very popular among Civil War buffs, especially ones with sympathies for the Confederate cause. In fact, replicas of the Butler chamber pots were once sold in the gift shop of New Orleans’ own Confederate Memorial Hall Museum.[31]

However, it is difficult to determine whether these objects were actually produced during the period of Butler’s occupation of the city. Few extant examples have any historical provenance, and some that have appeared for auction were clearly produced decades after the 1860s.[32] The one illustrated here, from the collection of the Alabama Department of Archives and History in Montgomery, was acquired in 1924 and thus certainly has considerable age, but it probably was not made in the 1860s. No examples of these chamber pots have been found in an archaeological context.[33] It is possible that they are a product of Lost Cause revisionism, an attempt to romanticize Southern resistance dating from the same period as the Confederate monuments that are only now being dismantled in the city.[34]

Wasters and Kiln Furniture from Lucien Gex Pottery

In 1883 Bertrand Saloy embarked on a short-lived attempt “To manufacture and sell porcelain goods and all kinds of crockeries, glassware and potteries for domestic and foreign markets.”[35] His New Orleans Porcelain Manufacturing Company generated considerable interest, but in 1886 its kilns were reported as being “completely destroyed” by fire (fig. 18).[36] Saloy soon sold his interest in what became the Louisiana Porcelain Works, and the former superintendent of Saloy’s venture, Lucien M. Gex, moved a short distance away on the Carondelet Walk and opened his own pottery. In 1889 a complaint lodged by the Health Committee of New Orleans declared that “The Gex Pottery” was a nuisance; within a few years, Gex left for Bay St. Louis, Mississippi, apparently abandoning the pottery business entirely.[37]

Archaeologists began to examine the block on which the Gex Pottery was located prior to the redevelopment of the Lafitte Public Housing Project, which had occupied the site since World War II.[38] While remains of the kiln itself had been obliterated by later development, a collection of wasters and kiln furniture dating to the period of the Gex Pottery was recovered (figs. 19, 20). Much was made of Saloy’s efforts to use both French workmen and materials to manufacture true hard-paste porcelain, but the Gex Pottery seems to have been aimed mostly at utilitarian wares, such as stoneware jugs and crocks, many with Albany-type slips.

Zuni Pueblo Olla

A number of major redevelopment projects in the years since Hurricane Katrina have transformed the built landscape of New Orleans. Because so many of these were the result of federal involvement, the pace and scale of archaeological work done in compliance with Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act in the city has increased dramatically. The construction of the new Medical Center of Louisiana and Veteran’s Administration hospital complex near downtown New Orleans is a case in point, involving some twenty-seven blocks that were formerly part of the historic Mid-City neighborhood. Thousands of artifacts have been recovered in archaeological excavations in advance of such projects. This material is being coupled with documentary sources to produce a detailed picture of consumer practices in complex, multiethnic neighborhoods in the period after Emancipation and the end of the Civil War.

Some of the ceramic finds from excavated contexts in these areas are themselves unexpected. In what had been the yard of a Mid-City house located at 1905/1907 Cleveland Street, archaeologists excavated a well filled with a large collection of material, including a Zuni Pueblo olla, or water jar (fig. 21). The polychrome decoration, with the repeated “heartline deer” and stylized bird motifs, is typical of Zuni pottery in the latter part of the nineteenth century.[39] Based on the age of other artifacts found in the well, the olla appears to have been deposited there around 1900–1910. Why it was put there is a minor mystery but its presence is a reminder of the popular fascination with the Native societies of the Plains and Southwest in the era around the turn of the century. The visit of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show to the city during the 1884–1885 Cotton Centennial Exposition has sometimes been claimed as a source of inspiration for the masking traditions of the Mardi Gras Indians (fig. 22), even though the mixing of Black and Native American cultures in New Orleans has much deeper historical roots, as discussed earlier in this article.[40] The presence of this Zuni vessel suggest that there might have been many avenues of influence in the development of the New Orleans Indian traditions.

Ceramic Items from Storyville

After traveling abroad and seeing European attempts to regulate commercial sex, alderman Sidney Story, an anti-prostitution reformist, proposed the creation of a restricted district in New Orleans. The city, fearful of appearing to legalize prostitution per se, sidestepped the appearance of doing so through the careful wording of an 1897 ordinance that made it unlawful for “any public prostitute or woman notoriously abandoned to lewdness” to occupy a premises outside of the district’s boundaries. The “Storyville” vice district has since taken an outsized importance in the mythology of the city for its sheer size and visibility, its marketing of sex across the color line, and, perhaps most famously, its reputation as the birthplace of New Orleans jazz. Although the district was officially shuttered by 1918, the Storyville name can be found applied today to music clubs, shops, clothing lines, and more.[41]

It is unfortunate that nearly the entire architectural legacy of Storyville has been lost, demolished around World War II to make way for the Iberville Public Housing Projects. The Iberville Projects, as of this writing, are going through their own redevelopment, allowing archaeologists an opportunity to access the archaeological remains of the Storyville neighborhood (fig. 23). While the luxurious brothels along Basin Street have been the focus of museum collections and of romanticized accounts of the district, the material recovered archaeologically documents the unsavory life behind that façade of gentility (fig. 24).[42] Illustrated in figure 25 is a bisque hand for storing rings and jewelry that likely would have been kept on a dresser or mantlepiece. It was recovered from a privy shaft along with medicinal bottles, buttons, glass beads from a chatelaine, and hygienic syringes suitable for treating venereal diseases.

A great deal has been written about the post-Katrina planning process. For a start, see the collections in Manning Marable and Kristen Clarke-Avery, eds., Seeking Higher Ground: The Hurricane Katrina Crisis, Race, and Public Policy Reader (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2008); and Philip E. Steinberg and Rob Shields, eds., What Is a City?: Rethinking the Urban after Hurricane Katrina (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2008). See also Lynnell L. Thomas, Desire and Disaster in New Orleans: Tourism, Race, and Historical Memory (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2014).

See, e.g., Shannon Lee Dawdy, Building the Devil’s Empire: French Colonial New Orleans (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008); Sophie White, Wild Frenchmen and Frenchified Indians: Material Culture and Race in Colonial Louisiana (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012); J. Mark Souther, New Orleans on Parade: Tourism and the Transformation of the Crescent City (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2006); Judith Kelleher Schafer, Brothels, Depravity, and Abandoned Women: Illegal Sex in Antebellum New Orleans (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2009); Alecia P. Long, The Great Southern Babylon: Sex, Race, and Respectability in New Orleans, 1865–1920 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2004); Emily Epstein Landau, Spectacular Wickedness: Sex, Race, and Memory in Storyville, New Orleans (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2013); Gary Krist, Empire of Sin: A Story of Sex, Jazz, Murder, and the Battle for Modern New Orleans (New York: Crown, 2014); Herbert Asbury, The French Quarter: An Informal History of the New Orleans Underworld (1936; reprint, New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press, 2003).

Daniel H. Usner Jr., “American Indians in Colonial New Orleans,” in Powhatan’s Mantle: Indians in the Colonial Southeast, edited by Peter H. Wood, Gregory A. Waselkov, and M. Thomas Hatley (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1989), pp. 163–86.

Jennifer M. Spear, Race, Sex, and Social Order in Early New Orleans (Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009); Gwendolyn Midlo Hall, Africans in Colonial Louisiana: The Development of Afro-Creole Culture in the Eighteenth Century (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1992). See also Arnold R. Hirsch and Joseph Logsdon, eds., Creole New Orleans: Race and Americanization (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1992); Bradley G. Bond, ed., French Colonial Louisiana and the Atlantic World (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2005).

Lawrence N. Powell, The Accidental City: Improvising New Orleans (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2012). See also Charles Gayarré, History of Louisiana, Vol. 3: The Spanish Domination, 5th ed. (1903 reprint of 4th ed., Gretna, La.: Pelican Publishing, 1974); Sybil Kein, ed., Creole: The History and Legacy of Louisiana’s Free People of Color (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2000); Carolyn Cossé Bell, Revolution, Romanticism, and the Afro-Creole Protest Tradition in Louisiana, 1718–1868 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1997); Kimberly S. Hanger, Bounded Lives, Bounded Places: Free Black Society in Colonial New Orleans, 1769–1803 (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1997).

The population estimates are summarized in Richard Campanella, Geographies of New Orleans: Urban Fabrics before the Storm (Lafayette: Center for Louisiana Studies, 2006).

Nathalie Dessens, From Saint-Domingue to New Orleans: Migration and Influences (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2007); Robert C. Reinders, End of an Era: New Orleans, 1850–1860 (New Orleans, La.: Pelican Publishing, 1964), H. E. Sterkx, The Free Negro in Ante-bellum Louisiana (Rutherford, N.J.: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1972).

Craig E. Colten, An Unnatural Metropolis: Wresting New Orleans from Nature (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2005). See also Virginia R. Domínguez, White by Definition: Social Classification in Creole Louisiana (1986; reprint, New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1994).

Shirley Elizabeth Thompson, Exiles at Home: The Struggle to Become American in Creole New Orleans (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2009); Kent B. Germany, New Orleans After the Promises: Poverty, Citizenship, and the Search for the Great Society (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2007); Kevin Fox Gotham, Authentic New Orleans: Tourism, Culture, and Race in the Big Easy (New York: New York University Press, 2007); Daphne Spain, “Race Relations and Residential Segregation in New Orleans: Two Centuries of Paradox,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 441 (January 1979): 82–96; John W. Blassingame, Black New Orleans, 1860–1880 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1973).

An up-to-date general overview of archaeology in New Orleans may be found in Shannon Lee Dawdy and Christopher N. Matthews, “Colonial and Early Antebellum New Orleans,” in The Archaeology of Louisiana, edited by Mark Rees (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2010), pp. 273–90; D. Ryan Gray and Jill-Karen Yakubik, “Immigration and Urbanization in New Orleans,” in ibid., pp. 291–305; and Jason A. Emery, “What Do Tin-Enameled Ceramics Tell Us? Explorations of Socio-Economic Status through the Archaeological Record in Eighteenth-Century Louisiana, 1700–1790,” master’s thesis, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, 2004.

For a general discussion of the topography and development of New Orleans, see Peirce F. Lewis, New Orleans: The Making of an Urban Landscape, 2nd ed. (Santa Fe, N.M.: Center for American Places in association with the University of Virginia Press, 2003); and Ari Kelman, A River and Its City: The Nature of Landscape in New Orleans; (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003). See also Campanella, Geographies of New Orleans, and Richard Campanella, Time and Place in New Orleans: Past Geographies in the Present Day (Gretna, La.: Pelican Publishing, 2002).

The only in-depth studies of eighteenth-century ceramics on New Orleans sites are those found in Jill-Karen Yakubik, Ceramic Use in Late-Eighteenth-Century and Early-Nineteenth-Century Southeastern Louisiana, Ph.D. diss., Tulane University, New Orleans, La., 1990; and Emery, “What Do Tin-Enameled Ceramics Tell Us?” For a number of good color illustrations of French faience and glazed coarse earthenwares, including some from New Orleans contexts, see George E. Avery, ed., French Colonial Pottery: An International Conference (Natchitoches, La.: Northwestern State University Press, 2007).

See Shannon Lee Dawdy, Kristen Gremillon, Susan Mulholland, and Jason Ramsey, Archaeological Investigations at St. Anthony’s Garden (16OR443), New Orleans, Louisiana, Volume I: 2008 Fieldwork and Archaeobotanical Results, report submitted to St. Louis Cathedral, Archdiocese of New Orleans, 2008; and Shannon Dawdy, C. Bowman, Z. Chase, S. deFrance, D. R. Gray, K. Gremillion, and L. Zych, Archaeological Investigations at St Anthony’s Garden (16OR443), New Orleans, Louisiana, Vol. II: 2009 Fieldwork Results, Faunal Report, Artifact Analyses and Final Site Interpretations, report submitted to St. Louis Cathedral, Archdiocese of New Orleans, 2014.

The item was recovered during excavations undertaken by Christopher Grant, Ph.D. candidate at the University of Chicago, as part of his dissertation fieldwork in New Orleans, with the assistance of the University of New Orleans Department of Anthropology.

The basic lines of the debate over colonoware are outlined in a number of chapters in the edited volume by Theresa Singleton, ed., “I, Too, Am America”: Archaeological Studies of African-American Life (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1999), particularly the ones by Leland Ferguson, Matthew Emerson, and L. Daniel Mouer et al. See also Leland Ferguson, Uncommon Ground: Archaeology and Early African America, 1650–1800 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2004), and Ivor Noël Hume, “An Indian Ware of the Colonial Period,” Quarterly Bulletin: Archeological Society of Virginia 17, no. 1 (1962): 2–14. The special forum in Historical Archaeology on the meaning of the “Edgefield crosses” on South Carolina pottery mirrors some of this debate as well. See Charles Ewen, “Crosses to Bear: Searching for Symbolism and Meaning in Edgefield Pottery,” Historical Archaeology 45, no. 2 (2011): 132–33, and accompanying articles.

Morgan and MacDonald have suggested that the colonoware label be extended to much of the hand-built pottery found in Colonial Louisiana, but their criteria of definition seem too broad to have much analytical utility. David W. Morgan and Kevin C. MacDonald, “Colonoware in Western Colonial Louisiana: Makers and Meaning,” in Kenneth G. Kelly and Meredith D. Hardy, eds., French Colonial Archaeology in the Southeast and Caribbean (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2011), pp. 117–51.

Lauren Zych, “Low-Fire Earthenwares and Intercultural Relations in French Colonial New Orleans, 1718–1763: Preliminary Results from Three Sites,” Louisiana Archaeology 40 (2013): 73–112.

D. Ryan Gray, Rediscovering the “Antiguo Cementerio”: Archaeological Excavations and Recovery of Human Remains from the St. Peter Street Cemetery (16OR92), Orleans Parish, Louisiana, report submitted to the Louisiana Division of Archaeology, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, 2016; and Ginesse Listi and Mary Manhein, Analysis of Human Skeletal Remains Excavated in 2011 from the St. Peter Street Cemetery (16OR92), New Orleans, Louisiana, report prepared for the Louisiana Division of Archaeology by the LSU FACES Laboratory, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, 2013.

Michael E. Crutcher Jr., Tremé: Race and Place in a New Orleans Neighborhood (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2010). Of course, the musical connections of the Tremé neighborhood have also now been cemented in the minds of many by the HBO series of the same name, set in post-Katrina New Orleans.

Christopher N. Matthews, Management Report of Excavations at the St. Augustine Site, 16OR148, report submitted to Louisiana Division of Archaeology, 1999. These red-slipped filmed wares have been noted at a number of colonial-era sites in New Orleans, including St. Anthony’s Garden (16OR443), Madame John’s Legacy (16OR51), 400 Chartres Street (16OR467), and 810 Royal Street (16OR706). Rob Mann discussed the wider distribution of these wares in the Lower Mississippi Valley in his paper “Persistent Pots and Durable Kettles: Aboriginal Pottery Production during the Colonial Period in the Lower Mississippi Valley and Great Lakes,” presented at the 2009 meetings of the American Society for Ethnohistory, New Orleans, Louisiana; Lauren Zych (“Low-Fire Earthenwares”) has also incorporated these wares in her project.

The term Creole is itself a contentious one. Though often associated with New Orleans, its meaning even within the city has changed over time. See the discussion in Shannon Lee Dawdy, “Understanding Cultural Change through the Vernacular: Creolization in Louisiana,” Historical Archaeology 34, no. 3 (2000): 107–23; Dawdy, preface to ibid., pp. 1–4; and Dawdy, “Ethnicity in the Urban Landscape: The Archaeology of Creole New Orleans,” in Archaeology of Southern Urban Landscapes, edited by Amy L. Young (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001). See also Stephan Palmié, “Creolization and Its Discontents,” Annual Reviews of Anthropology 35 (2006): 433–56.

Christopher N. Matthews, “Political Economy and Race: Comparative Archaeologies of Annapolis and New Orleans in the Eighteenth Century,” in Race and the Archaeology of Identity, edited by Charles E. Orser Jr. (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2001). On the significance of parading traditions in African-American New Orleans, see, e.g., Rachel Breunlin and Helen A. Regis, “Putting the Ninth Ward on the Map: Race, Place, and Transformation in Desire, New Orleans,” American Anthropologist, n.s. 108, no. 4 (December 2006): 744–64. Jason Berry has written very accessibly about some of the long-standing traditions of the Black Indian community in New Orleans, in The Spirit of Black Hawk: A Mystery of Africans and Indians (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1995).

John Garretson Clark, New Orleans, 1718–1812: An Economic History (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1970). See also Meredith Hardy, “A Question of Origin: Archaeological Evidence of 18th Century Spanish Trading Practices in the New Orleans Colony, Hermann-Grima House, 16OR45,” master’s thesis, University of New Orleans, College of Urban and Public Affairs, 1998.

As of this writing, field investigations at 810 Royal are still ongoing, as rebuilding on the lot has been delayed by the complex permit process of such a sensitive section of the French Quarter. Periodic updates may be found on the project’s website, theartofdigging.com.

A very personal account of the attempt to trace the song’s origins can be found in Ted Anthony, Chasing the Rising Sun: The Journey of an American Song (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2007).

The technical report of these investigations is available for download from the University of Chicago. See Shannon Dawdy, Ryan Gray, and Jill-Karen Yakubik, Archaeological Investigations at the Rising Sun Hotel Site (16OR225), New Orleans, Louisiana, Volume I, report prepared for the Historic New Orleans Collection, New Orleans, Louisiana, 2008, http://home.uchicago.edu/~sdawdy/risingsun/RisingSun%20complete.pdf.

Shannon Dawdy and Richard Weyhing, “Beneath the Rising Sun: ‘Frenchness’ and the Archaeology of Desire,” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 12 (2008): 370–87.

My thanks to Mr. Randy Boyer, an enthusiastic collector of the Richard Jordan pattern, who has researched it extensively and was kind enough to share his findings with me, including materials demonstrating conclusively that the pattern was produced by Joseph Heath and Company. The dates for Joseph Heath and Company are those given in Arnold A. Kowalsky and Dorothy E. Kowalsky, Encyclopedia of Marks on American, English, and European Earthenware, Ironstone, and Stoneware, 1780–1980 (Atglen, Pa.: Schiffer Books, 1999).

The items illustrated here were recovered during excavations conducted on short notice by Earth Search, Inc., for a small expansion of what was then the National D-Day Museum. The scope increased significantly when the museum became the National World War II Museum and expanded into two additional city blocks. While the full technical report is still under preparation, some of the work has been discussed in Benjamin D. Maygarden, D. Ryan Gray, and Jill-Karen Yakubik, Historical and Cartographic Background Research, National D-Day Museum Expansion, Archaeological Mitigation Plan, New Orleans, Louisiana, submitted to the Division of Archaeology, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, 2005.

For example, see James K. Hogue, Uncivil War: Five New Orleans Street Battles and the Rise and Fall of Radical Reconstruction (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2006); and William Hair, Carnival of Fury: Robert Charles and the New Orleans Race Riot of 1900 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2008). On the longer history of the civil rights struggle in New Orleans, see Germany, New Orleans After the Promises.

Asbury, The French Quarter, pp. 227–28, gives at least one version of the story, attributing the resentment against Butler mainly to the women of the red-light district: “A large number of portraits of Butler had been distributed soon after he entered the city, and most of them eventually found their way into the houses of prostitution. A few days after the issuance of the Woman Order, Butler learned that his portraits were being put to an extraordinary use—the prostitutes had pasted them to the bottoms, inside, of their tinkle pots!” Even Asbury, who is loose with facts throughout this work, goes on to say that this story is unconfirmed. Nevertheless, it has been taken by some historians as authoritative; Chester Hearn, for instance, repeats it almost verbatim, even going so far as to refer to “tinkle-pots” as well. See Hearn, When the Devil Came Down to Dixie: Ben Butler in New Orleans (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1997), p. 108. Other accounts, including many of those circulated on online Civil War history forums, give a more formal version of the story, attributing the chamber pots to enterprising merchants who capitalized on the animosity toward Butler, though without specific attribution. So far, I have not been able to locate a version in print before Asbury’s in the 1930s, and many of the historians working from primary source documents like Butler’s extensive correspondence do not reference it, even when it would have direct bearing on their research. See, e.g., Alecia Long, “(Mis)Remembering General Order No. 28: Benjamin Butler, the Woman Order, and Historical Memory,” in Occupied Women: Gender, Military Occupation, and the American Civil War (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2012); and Hans Trefousse, Ben Butler: The South Called Him Beast (New York: Octagon Books, 1974). Joan Cashin, a historian specializing in the material culture of the Civil War era, has also suggested that the chamber pots are a postwar phenomenon (Cashin, personal communication, September 7, 2016).

The only marked example to which I could find a reference was one from an antiques auction that bore a mark from the Johnson Brothers Pottery of England, which was not in business until 1883. The print shown on this example was completely different in style from the one in the (ADAH).

The item in the ADAH collection was donated in 1924 by Mrs. C. B. Whitfield of Demopolis, Alabama, when the department was actively seeking Civil War artifacts, and was said by her to have been bought in New Orleans. The repairs in evidence in figure 16 had apparently already taken place. My thanks to Graham Neeley and the staff at the ADAH for their assistance, and for providing me with copies of the documentation they had on hand.

In 2015 the City Council and Mayor Mitch Landrieu approved a plan to remove four Confederate Civil War monuments: statues of Confederate President Jefferson Davis and Confederate Generals Robert E. Lee and P.G.T. Beauregard; and a monument honoring the “White League” and the so-called Battle of Liberty Place, which effectively ended the era of Reconstruction in Louisiana and restored white supremacist rule in the city.

New Orleans Daily Picayune, March 7, 1883. I am indebted to Elizabeth Williams and the staff of Earth Search, Inc., for sharing their preliminary research on the Saloy and Gex potteries. We hope to present some of this research in more depth in the not-too-distant future. In addition, Gretchen Byers, a master’s student in the urban studies program at the University of New Orleans, is currently researching the Gex Pottery for her thesis.

New Orleans Daily States, November 25, 1886. There is a rather extensive discussion of the pottery and its production process in the New Orleans Daily Picayune of April 22, 1883. The Saloy endeavor to manufacture porcelain in New Orleans is also referenced in such standard sources as John Ramsay, American Potters and Pottery ([Boston]: Hale, Cushman & Flint, 1939), p. 112, and Edwin Atlee Barber, The Pottery and Porcelain of the United States (New York and London: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1893), p. 313.

New Orleans Daily States, March 15, 1889.

Elizabeth Williams, Dorion Ray, Dayna Lee, and Michael Godzinski, “Excavations at City Square 281, Phase III Cultural Resources Survey of the Lafitte Housing Project, New Orleans, Louisiana,” 2016, ms. on file at Earth Search, Inc., New Orleans, Louisiana. The excavations at Square 281 and the Gex Pottery are a small component of a much larger investigation of the Lafitte redevelopment.

In some cases, the “heartline deer” might actually be an elk or pronghorn antelope; it is considered one of the characteristic designs motifs on Zuni Polychrome vessels. A tremendous number of these vessels were collected from 1879 to 1885 by Frank Cushing for the Bureau of American Ethnology, and by the beginning of the 1900s some visitors considered the pueblo to have been so scoured by collectors (particularly those from museums) that few nineteenth-century examples were left. The designs on Zuni Polychromes have been extensively studied; see Dwight Lanmon and Francis Harlow, The Pottery of Zuni Pueblo (Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press, 2008), for one of the more comprehensive attempts to explore the development of Zuni pottery.

The possible influence of the Wild West show on the imagery of the Mardi Gras Indians has been discussed by the photographer Michael Smith, among others, although he also emphasizes that there were many Black-Indian connections in the late-nineteenth-century South. Michael Smith and Alan Govenar, Mardi Gras Indians (Gretna, La.: Pelican Publishing, 1994). See also Jeffrey Ehrenreich, “Bodies Beads, Bones, and Feathers: The Masking Tradition of Mardi Gras Indians in New Orleans, a Photo Essay,” City and Society 16, no. 1 (2004): 117–50; and Helen Regis, “Second Lines, Minstrelsy, and the Contested Landscapes of New Orleans Afro-Creole Festivals,” Cultural Anthropology 14, no. 4 (1999): 472–504.

The most widely circulated source on Storyville is Al Rose, Storyville, New Orleans: Being an Authentic, Illustrated Account of the Notorious Red-Light District (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1978), but Landau’s Spectacular Wickedness and Long’s The Great Southern Babylon provide much more nuanced accounts of the origins and development of the district, without quite so much of an eye to romanticizing.

Earth Search, Inc. and the University of New Orleans have both conducted excavations during the Iberville Housing Projects redevelopment. A full report is still in progress, but descriptions of the archaeological projects at Iberville and three other housing projects in the city may be found in D. Ryan Gray, Re-Newing New Orleans: Race, Labor, and Archaeology in the City’s Public Housing Projects (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, forthcoming).