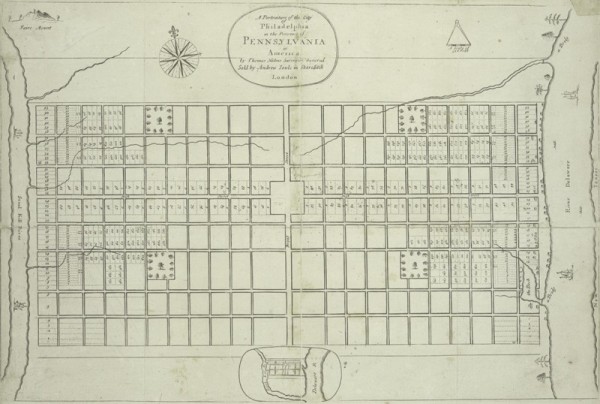

Thomas Holme, A Portraiture of the City of Philadelphia in the Province of Pennsylvania in America, London, England, 1683. 11 1/2 x 17 1/2". (Courtesy, New York Public Library.)

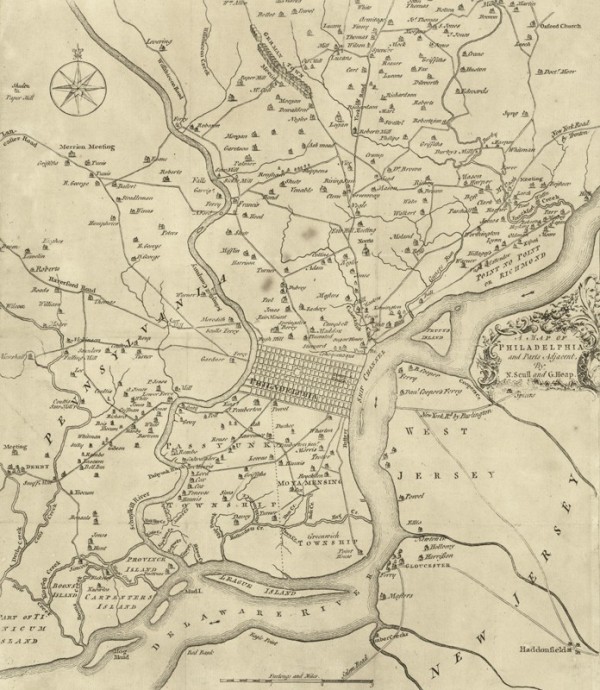

Nicholas Scull (1686?–1761?) and George Heap (act. 1715–1760), A Map of Philadelphia and Parts Adjacent, reproduced from Gentleman’s Magazine 23 (1753): 373. 13 3/4 x 11 13/16". (Courtesy, Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division, LCCN 2010587015.) Thomas Holme’s original grid plan for the city (see fig. 1) is intact in the center of the map, illustrating how much Philadelphia and her immediate hinterlands had grown by the mid-eighteenth century.

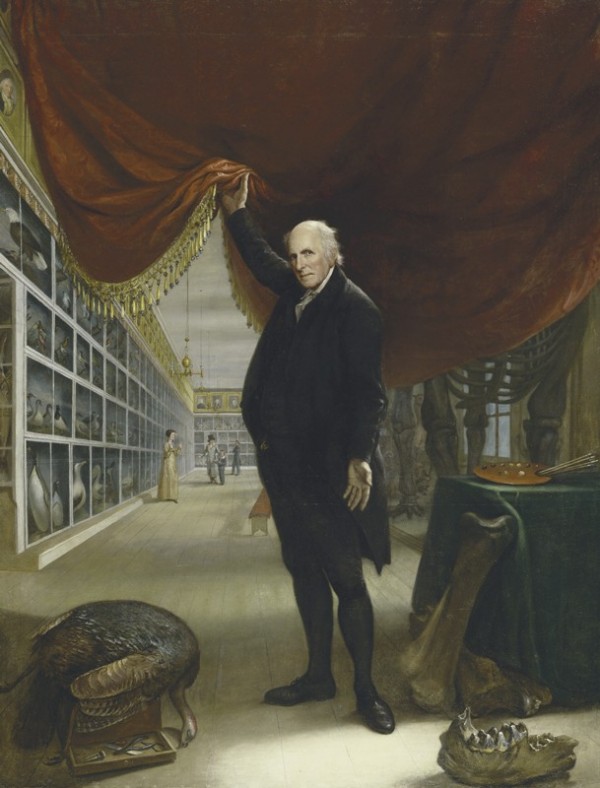

Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827), Artist in His Museum, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1822. Oil on canvas, 103 3/4 x 79 7/8". (Courtesy, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, Gift of Mrs. Sarah Harrison.) The first of its kind in America, the Philadelphia Museum, which Peale founded in what is now Independence Hall, embodied the civic, intellectual, and artistic achievements of Philadelphia. Its exhibits captured the essence of enlightened thought and the sophisticated spirit of the new nation.

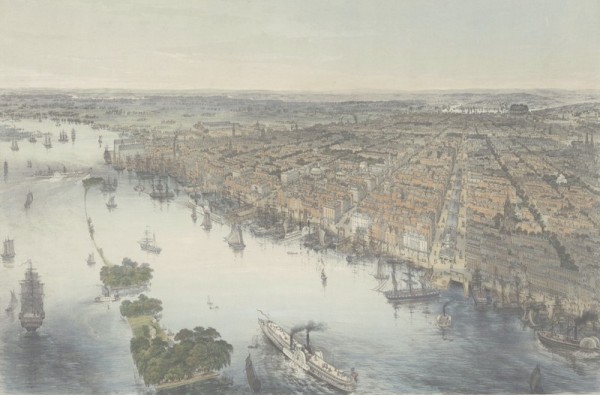

John Bachmann, Bird’s Eye View of Philadelphia, Drawn from Nature and on Stone by J. Bachmann, ca. 1850. Printed by Williams and Stevens, New York, New York. Hand-colored lithograph, 27 x 18 1/4". (Courtesy, Free Library of Philadelphia.) Philadelphia had grown well beyond its original boundaries by the mid-nineteenth century. Manufacturing was centered on the banks of the Delaware in Kensington, just north of the city center and along the Schuylkill River to the east.

Volunteers at the Independence National Historical Park Archaeology Laboratory mend red earthenware fragments recovered from one privy. Note the variety of decoration and form exhibited by this ceramic assemblage. (Courtesy, National Park Service, Independence National Historical Park.)

Partially excavated privy from the National Constitution Center site, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2003. (Courtesy, National Park Service, Independence National Historical Park.) This photo shows a trash layer containing discarded eighteenth-century domestic goods, such as ceramics, glass, and small household items. The scale in the photo is three feet in length.

Charger and bowl, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, second quarter of eighteenth century. Slipware. D. of charger 14 3/4", H. of bowl 2 5/16". (Courtesy, Chris Rowell; photo, Deborah Miller.) The charger is reminiscent of English Staffordshire-type slipware that is commonly found on American colonial archaeological sites. The form and decoration of the bowl are consistent with wasters discovered in a rubbish pit behind George Peter Hillegas’s property on Second Street. The use of copper oxide was introduced after the arrival of German and, in the case of the Hillegas Brothers, French potters to the colony in the 1720s.

Charger, bowl, dish, and pan, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, late eighteenth century. Slipware. D. of charger 15". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Independence National Historical Park.) Vessels of diverse forms with multiple applications of straight and wavy lines, sometimes combined with splotches of copper oxide, are characteristic of “Philadelphia Style” wares. Examples like these number in the tens of thousands on Philadelphia archaeological sites.

Jug, Anthony Duché, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1720–1764. Salt-glazed stoneware with iron oxide slip. H. 9 3/4". Impressed “AD” below handle terminal. (Courtesy, State Museum of Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This jug was excavated from a privy at Front and Dock Streets, where the Society Hill Sheraton Hotel is now located.

Chamber pots, Anthony Duché, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1724–1764. Salt-glazed stoneware. Impressed “AD” at base of handle. H. 6" (all vessels). (Courtesy, National Park Service, Independence National Historical Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These five chamber pots are decorated with stamped designs infilled with cobalt. The fleur-de-lis on the center vessel is a reminder of Anthony Duché’s French heritage.

Pan, southeastern Pennsylvania (likely Philadelphia), ca. 1730–1765. Slipware. D. 14". (Courtesy, The National Society of The Colonial Dames of America in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania at Stenton; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This pan might have played a ceremonial role in diplomatic negotiations held at Stenton between James Logan and delegates from the Six Nations in 1736 and 1742.

John Simon, Sa Ga Yeath Qua Pieth Tow, King of the Maguas, London, England, 1710. Mezzotint. 16 5/16 x 10 1/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, museum purchase, 1970.0005 A.) This is the one of a set of four mezzotints after full-length oil protraits commissioned of John Verelst by Queen Anne. Contrmporary images like this one may have served as the model for common objects like the slipware bowl excavated at Stenton (fing. 11).

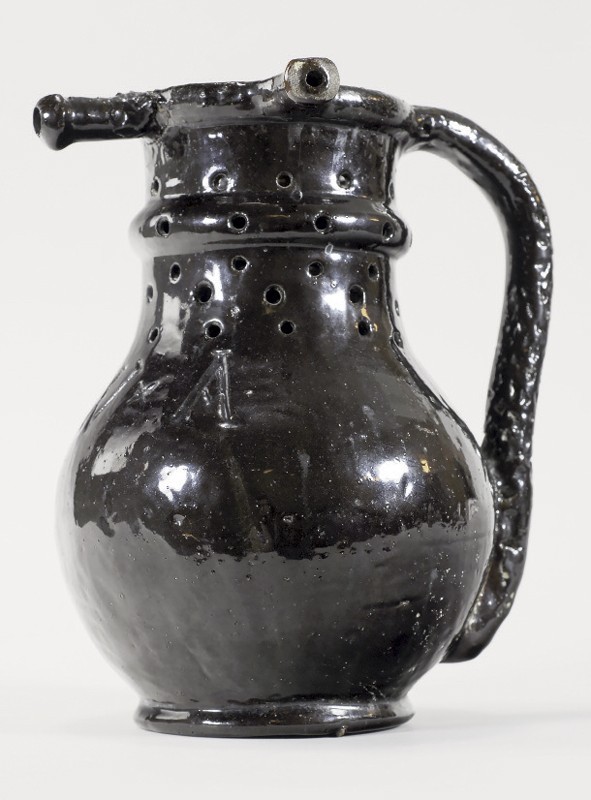

Puzzle jug, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1747. Red earthenware with manganese glaze. Incised “WA” on front. H. 8 3/4". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Independence National Historical Park.) Found in the privy near the home of William Annis, the initials suggest that this striking puzzle jug was made for him but discarded intact, probably because a manufacturing flaw on the handle made it unusable.

Plate, Jingdezhen, China, ca. 1735–1748. Porcelain. D. 9". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Independence National Historical Park.) The central pineapple is flanked by a branch of cloves on the left and a nutmeg on the right.

Teapot fragments, probably Staffordshire, England, ca. 1755–1785. White salt-glazed stoneware with a Littler-Wedgwood blue glaze. (Courtesy, State Museum of Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission; photo, Deborah Miller.)

Tea table, set with English white salt-glazed and cream-colored earthenware teapots and Chinese porcelain teawares, ca. 1725–1760. (Courtesy, The National Society of The Colonial Dames of America in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania at Stenton; photo, Jeff Story.) At least twelve teapots and dozens of teabowls and saucers were excavated from a cistern at Stenton, the ca. 1730 home of James Logan in Germantown. For families like the Logans, tea drinking solidified social and political networks while demonstrating participation in polite culture.

Cooking pot, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, late eighteenth century. Earthenware. (Courtesy, National Park Service, Independence National Historical Park.) Colonoware is exceedingly rare on archaeological sites north of the Chesapeake, and fewer than one hundred examples have been excavated in Philadelphia. This partial vessel is the largest and most intact example to be recovered in the city to date.

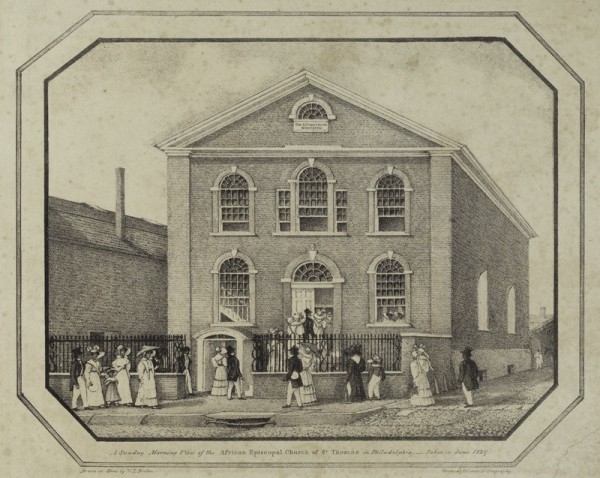

William L. Breton (ca. 1773–1855), A Sunday Morning View of the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas in Philadelphia. . . Taken in June 1829 (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Kennedy & Lucas Lithography, 1829). Lithograph on paper. 9 3/4 x 13 3/4". (Courtesy, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.) In 1787 former slaves Richard Allan and Absalom Jones founded the Free African Society, one of America’s first societies dedicated to improving the lives of newly freed slaves. By the nineteenth century, independent churches like the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas and Mother Bethel A.M.E. were the core of the free African-American community in Philadelphia.

Two sauceboats, saucer, and teabowl, American China Manufactory, Philadelphia, 1770–1772. Soft-paste porcelain. H. of sauceboats 3", D. of saucer 5 1/2", base of teabowl, 1 3/4". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Independence National Historical Park.) These four examples of Bonnin and Morris porcelain were excavated from two different sites at Independence NHP. The sauceboats are believed to have been owned by Caleb Cresson, a wealthy Quaker who originally developed what is now the National Constitution Center site. The ownership of the saucer and teabowl, both of which are marked “P” on the base, is unknown.

Saucer, American China Manufactory, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1770–1772. Soft-paste porcelain. D. 5 1/2". (Courtesy, Matthew and Melissa Dunphy; photo, Deborah Miller.) This saucer, along with a small punchbowl, was recently excavated from a privy at 103 Callowhill Street in the Northern Liberties. The punchbowl is marked "P" on the base. They are the most recent examples of Bonnin and Morris to be discovered.

Raphaelle Peale (1774–1825), Still Life of Fruit, Pitcher and Pretzel, 1810. Oil on wood panel, 11 3/4 x 13". (Courtesy, Hirschl & Adler Galleries, New York; photo, Eric W. Baumgartner.) In 1808 Peale’s father, Charles Willson Peale, exhibited at his museum some of the first examples of Philadelphia queensware, presumably made by Alexander Trotter at the Columbian Pottery.

Philadelphia queensware vessels. D. of plate 7". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Independence National Historical Park.) This group highlights the diversity of form and decoration found on Philadelphia queensware

Pitchers, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1815–1820. Pearlware. Black transfer-print with enamel decoration and pink lustre. H. 6". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Independence National Historical Park.)

Dish, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1818–1828. Red earthenware with “Alice” inscribed in slip. D. 9". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Independence National Historical Park.) In 1818 Otis and his family moved into the house at 63 Cherry Street, where they lived for almost ten years. Numerous artifacts from their personal lives were recovered from a privy that was once located behind their house, including this dish, which likely belonged to Otis’s wife, Alice.

Pitcher, Tucker and Hemphill, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1826–1838. Porcelain. 9 1/2 x 7 3/8 x 5 3/4". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift of John T. Morris, 1895.)

Pitcher and serving dish, Tucker and Hemphill, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1826–1838. Porcelain. H. of pitcher 7 1/4", D. of dish 8 1/4". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Independence National Historical Park.)

William Penn established the capital of Pennsylvania between the banks of the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers in 1682. Combining the Greek words for “love” and “brother,” Penn named his new settlement “Philadelphia” as an expression of his hopes and expectations for the kind of place it would be. Philadelphia was to be many things, a welcoming refuge for fellow Quakers and those of other faiths, a healthy “Greene Country Towne,” and a place that would “always be wholesome.”[1] To that end, in a progressive example of urban planning, he laid out Philadelphia with broad, straight streets in a gridiron plan with large lots with ample space for gardens (fig. 1).

Philadelphia’s foundations in religious acceptance and mild government, along with a temperate climate and rich soil, attracted a diverse group of settlers to the shores of the Delaware. Most came willingly from Britain, France, and the Germanic speaking regions of Europe, but others did not.[2] Enslaved Africans arrived in chains and many indentured servants came under duress, driven by economic necessity and a chance for a better life.

Despite energetic and enthusiastic promotion by the proprietor, the population saw only modest growth before 1720.[3] By the late eighteenth century, however, the city had more than 30,000 inhabitants. Its economic development was fueled by a fine port and bountiful hinterlands to the west and north (fig. 2).[4] Parades of ships delivered an endless stream of merchandise from European and Caribbean ports. From kegs of nails and chests of tea to hogsheads of Chinese porcelain, goods flooded the shelves of local merchants. Importers and dealers were happy to cater to Philadelphia’s taste for fine goods, with merchants offering an astonishing array of imports in the eighteenth century.

Philadelphia also became a center of domestic manufacturing. As early as the 1690s local artisans began producing goods, and laid the foundation of change that would ultimately transform Philadelphia from a “Country Towne” into a manufacturing hub. Immigrant potters were among the first craftspeople to set down roots in Philadelphia, establishing an unequaled earthenware industry that also experimented, sometimes successfully, with stoneware and porcelain. By the mid-eighteenth century, Philadelphia led the country in domestic ceramic manufacture until the rise of Trenton, New Jersey, and East Liverpool, Ohio, a century later.[5]

The early decades of the nineteenth century were marked by prosperity and growth. Philadelphia had become an incubator of American art, academics, and scientific endeavor, earning the moniker “Athens of America” in recognition of its cultural achievements (fig. 3).[6] Improvements in transportation and manufacturing, spurred by the introduction of the steam engine, saw the beginnings of Philadelphia’s transformation to an industrial powerhouse (fig. 4).[7] The city’s fortunes would wax and wane over the next century as its economic and social life was buffeted by national and international currents and by increasing competition from domestic and foreign markets. Despite its diversified industrial base and active port, this competition ultimately led to the collapse of Philadelphia’s manufacturing core.

Excavations at Independence National Historical Park in the early 1950s demonstrated the rich potential of archaeology in the city. By the mid-1980s, dozens of excavations had revealed astonishing deposits of household debris, including vast quantities of imported and domestic ceramics.[8] Excavation and study of such deposits endures to this day, and continues to provide new insights into Philadelphia’s past (fig. 5).

Our selection of Philadelphia’s “top ten” ceramics reflects the city’s commercial success and the sophisticated consumers it created and sustained, where goods from distant shores flowed into the homes, and, most important for us, the privies, of residents (fig. 6). But, these ceramics also stand as a testament to the productive spirit of Philadelphia’s people, many of whom brought with them skills acquired in their homelands—skills that they honed and adapted in the city of brotherly love. Here they crafted useful and beautiful things, and laid down the roots of an industry that would grow and contribute to the river of goods exported from a city that came to be known as the “workshop of the world.”

The “Philadelphia Style”

Potters were among the first artisans to arrive in Philadelphia, and soon founded what would become the most prolific utilitarian ceramic manufacturing center in preindustrial America. By 1700 three English-born potters were operating their own shops, using the locally abundant red clay for their pots, and lead, manganese, and copper for glaze. Here they made an array of forms reminiscent of their English forebears. Two decades later the first wave of German immigrants brought with them the colorful slip-decorated birds, flowers, and geometric designs so often associated with Pennsylvania red earthenware (fig. 7).

In 1726 Michael and George Peter Hillegas, French Huguenots who had resettled in Germany before coming to America, established the first European-style pottery on what is now Elfreth’s Alley.[9] Excavations at the back of George Peter’s Second Street lot, where wasters from the pottery had been discarded, made it possible to firmly attribute Hillegas wares. To date, the Hillegas waster tip is the only pottery production–related site to be excavated in the city.

By mid-century, English, French, and German pottery traditions had melded into one, what is now commonly referred to as the “Philadelphia Style” (fig. 8). Blending slip decoration and splashes of copper oxide on a multitude of forms, these wares were known for quality and durability and were sought throughout America well into the nineteenth century. They are commonplace on archaeological sites across the eastern seaboard and in Philadelphia number in the hundreds of thousands from local sites alone.

Duché Stoneware

Anthony Duché established a stoneware pottery on Chestnut Street between 4th and 5th Streets in the early 1720s.[10] Duché was not a potter himself, but his three sons—Anthony II, James, and Andrew—learned the trade and likely served as the pottery’s workforce while their father provided financial backing.[11]

Duché stoneware has been recovered from several archaeological sites in Philadelphia, and was first identified by the impressed initials “AD” found on several vessels (fig. 9).[12] All known examples are wheel-thrown gray- to brown-bodied stoneware. Some tankards and jugs are partially coated with slip under a salt glaze, and are virtually indistinguishable from English essels of the same type. Chamber pots have uniquely incised or stamped decorations infilled with cobalt (fig. 10).[13]

In 1730 the Duchés petitioned the Pennsylvania Assembly for a stoneware monopoly, which was “heretofore unknown in these Parts.”[14] This attempt to gain an advantage in a market otherwise dominated by imports failed when his request was denied. Despite this setback, Duché continued to operate the pottery until his death in 1762.[15] His son Andrew went on to found a pottery outside of Savannah, Georgia, where he claimed to have made the first American porcelain in 1738. In 1742 James lived briefly in Charlestown, just outside of Boston, after he was hired to teach the Parkers, who operated an earthenware pottery, how to make stoneware. The venture was not successful. Their sister Ann, who might have been a potter, managed the pottery after her father’s death until it burned in 1764. The efforts of the Duchés set the stage for American ceramic production, and firmly established them as America’s first great pottery dynasty.

The “Indian Bowl”

A red earthenware pan or bowl decorated with a slipped image of a Native American leaning on a musket was excavated from a cistern at Stenton, the home of James Logan, William Penn’s secretary (fig. 11).[16] The pan, along with more than twenty-five thousand other artifacts, was discarded into the cistern sometime around 1765, when improvements were being made to the property by William Logan, the second-generation owner of Stenton.

The slip figure is likely that of Sa Ga Yeath Qua Pieth Tow, chief of the Maguas and one of four Iroquois kings who visited the court of Queen Anne in 1710 (fig. 12). Portraits of each chief were made at that time. Mezzotint prints were available shortly thereafter, and are first documented in America in 1718.[17]

The “Indian Bowl,” as it has come to be known, is a unique reminder of the long and often contentious relationship between Pennsylvania and its native peoples. For five decades Logan advanced the interests of the Penn family (as well as his own) and the Pennsylvania Council in negotiations with the many tribes in and around the region. He hosted a Native American council at Stenton in 1736 and 1742. Both delegations, which consisted of more than one hundred men, women, and children, camped on site and were well entertained by Logan and his family. It is possible that the bowl played a ceremonial role in the complex negotiations between Logan and the visiting tribes, and served as a potent symbol of the rapidly fading history and culture of Pennsylvania’s original inhabitants.

A Sea Captain’s Plates

Centuries of development have obscured the dense networks of residential side streets and alleyways that were once common in the city. Excavations at the Area F site in Philadelphia’s Old City neighborhood uncovered one such streetscape, formerly known as Gray’s Alley, where William and Patience Annis lived from 1729 to 1749.[18] William was a successful ship captain who sailed to various American, European, and West Indian ports during his career. He operated within a multifaceted web of social and political networks, working with and for prominent Philadelphians such as James Logan. Through these connections, his own wit, and an advantageous marriage, Annis prospered.

The Annis privy was sealed about 1750, following the deaths of both William and Patience in 1749. The deposits within contained British slipware, Spanish majolica, refined English white salt-glazed stoneware, and locally made red earthenware (fig. 13). Three Chinese porcelain plates depicting a pineapple and single branches of nutmeg and clove were also recovered (fig. 14). The design, copied from a 1712 drawing in Pierre Pomet’s A Compleat History of Drugs, is a departure from the traditional Chinese landscapes and floral motifs common in the period.[19]

These three plates are the only known examples of this pattern in early America. They are physical evidence of Philadelphia’s connection to an extended global network of cultural and social exchange that defined eighteenth-century society. As a sailor, Annis transported not only goods, but also the ideas that helped shape the modern world.

Littler’s Blue Teapot

Sometimes archaeological finds fascinate us because they are beautiful and, in this case, rare objects. Such was the case of a “Littler’s Blue” teapot that was excavated from the Quaker Meeting House privy at the New Market/Head House site on Second Street (fig. 15). The pit contained tens of thousands of artifacts including 9,722 ceramic fragments discarded between 1755 and 1785.[20] Despite the association with the Friends Meeting, most of the artifacts belonged to nearby residents who used the privy as a neighborhood dump. While it is impossible to link the teapot to its owner, this piece confirms that they had access to fine goods.

Littler-Wedgwood Blue is a white salt-glazed stoneware coated with a fine blue slip. Developed by William Littler and his brother-in-law Aaron Wedgwood as early as 1749, the first advertisement for its sale was not until four years later, in 1753.[21] This ware type is rare on American archaeological sites, although examples have been identified at other urban sites such as Charleston, South Carolina, New York, and Williamsburg, Virginia.

Eighteenth-century Philadelphians were active participants in the world of polite culture, where refined behaviors and material goods communicated one’s gentility, and fashionable goods like this Head House teapot were socially important tools (fig. 16).[22] Tea drinking was the highest form of genteel expression, used to convey notions of refinement while solidifying the social and political networks of its drinkers.

Colonoware in the City

Even though urban archaeology is fairly predictable, especially on large-scale projects involving multiple house lots along major streets in a city, we are sometimes surprised by what we find, especially when we are not at all expecting it. One such surprise came during the excavation of the National Constitution Center (NCC) site, when the first examples of colonoware were recovered in Philadelphia (fig. 17).

Colonoware is a hand-built, unglazed, low-fired earthenware that most often mimics European utilitarian forms. It was first described in 1962 by Ivor Noël Hume as “Colono-Indian ware,” and was believed to have been made by Native Americans but used by enslaved Africans.[23] Archaeologists quickly came to recognize that people of African descent—both enslaved and free—were also intimately involved in both the use and the manufacture of this unique fusion of African, European, and Native American pottery traditions.[24]

In the fifty years following the Revolution, free African-Americans in Philadelphia comprised the nation’s largest and most important free black community.[25] Autonomous black churches, beneficial organizations, and other institutions sustained their community. Colonoware vessels reflect, in physical form, a cultural tradition rooted in Africa and tempered in the African Diaspora (fig. 18). The recent recovery of colonoware fragments from multiple vessels at the NCC site, along with scattered finds at sites across the mid-Atlantic and as far north as Massachusetts, extended the geographical range of the ware, which previously was thought to be limited to the Southeast and the Caribbean.[26] These finds suggest that colonoware represents a broader vernacular tradition, one that kept alive the knowledge and skill required to maintain casual production of a low-cost, utilitarian, ceramic ware.

The American China Manufactory

There is little need to rehash the full history of the American China Manufactory, Philadelphia’s first commercial porcelain factory.[27] Established in 1771 by Englishman Gousse Bonnin and Philadelphia native George Anthony Morris, the two-year enterprise produced blue-and-white soft-paste porcelain tea- and tablewares in the English style. Wasters excavated from a small part of the factory site point to a diversity of wheel-thrown and molded forms with hand-painted or transfer-printed decoration (fig. 19).

Philadelphia was the perfect incubator for such an endeavor. As one of the most cosmopolitan cities in the British Empire, it already supported an extensive network of artisans employed in making luxury goods for an eager provincial clientele.[28] Despite its ultimate failure, the American China Manufactory was a fundamentally important step in the development of American ceramics.

Archaeological examples of Bonnin and Morris are even rarer than the twenty surviving examples in museum collections—only ten have been firmly identified from Philadelphia domestic sites: two teabowls, four saucers, two punchbowls, and two sauceboats (fig. 20).[29] All are underglaze-blue painted in Chinese-style landscapes; the sauceboats are elegantly molded, with delicate C-scroll reliefs on either side of the body and double-scroll handles. Most recently, an example of American-made true porcelain was recovered during excavations for the new Museum of the American Revolution. The undecorated punchbowl is likely a result of Bonnin and Morris’s experiments using Cherokee clay that was sent to them in 1772 by Henry Laurens from Charleston, South Carolina.[30]

Although this group is limited, there are likely many more examples of Bonnin and Morris porcelain boxed away in the dusty basements and warehouses that serve as the final resting places of all too many archaeological collections. Careful reassessment of these collections, particularly those excavated before 1980, would likely yield an array of previously unidentified vessels.

Philadelphia Queensware

Philadelphia queensware became an established industry in 1808 when Jefferson’s Embargo interrupted trade between America and Britain. With the American marketplace starved for goods, local potters seized on the opportunity to fill the vacuum with a home-grown alternative.[31] Led by entrepreneurs Binny and Ronaldson, the first queensware manufactory was the Columbian Pottery, where “yellow and red teasets” were made by master potter Alexander Trotter.[32] By 1810 John Mullowny was making queensware at his Washington Pottery. Mullowny claimed to have introduced press molding to the United States in an 1812 advertisement noting “Turn’d and Pressed Ware, (the latter being the first manufactured in America).”[33] The mention of “Turn’d” ware may have been a nod to the introduction of engine-turned lathes to ceramic manufacture in the city during this period. Numerous excavated red earthenware and queensware vessels bearing engine- and lathe-turned decoration dating to this period have been identified as being of local manufacture.[34]

Philadelphia queensware has been recovered from a number of archaeological sites across Philadelphia, although it was first recognized at the McKean-Cochran site in Delaware.[35] Outwardly it bears no resemblance to the British creamware it imitated. The bodies are typically buff-colored, although later examples are made from refined white clays and are coated with a clear lead glaze. To the untrained eye it looks quite like yellow ware (fig. 21). The forms are plentiful—teabowls, saucers, teapots, plates, bakers, and so on (fig. 22). Decoration, if any, most often consists of green splotching across the body.[36] A jug and teapot with purple enameled decoration were excavated from the Independence Visitor Center and National Constitution Center sites in Independence National Historical Park.

The resumption of trade at the end of the War of 1812, particularly with England, flooded the market with inexpensive, high-quality ceramics that surpassed Philadelphia’s humble attempt at making sophisticated tableware, thus spelling the end to queensware manufacture in the city.

Victory at Sea

Excavations at the National Constitution Center site uncovered a pair of identical Staffordshire jugs commemorating two American naval victories during the War of 1812 (fig. 23). One side depicts the second American naval victory of the war, when the USS United States, a Philadelphia-built ship under the command of Stephen Decatur, captured the British frigate Macedonian off the coast of Madeira Spain on October 25, 1812.[37] The reverse shows the capture of the HMS Boxer by the USS Enterprise on September 13, 1813, a fierce albeit brief battle in which both captains were killed. The jugs were made in Staffordshire sometime between 1815 and 1820, and are based on source prints from The Naval Monument: Containing Official and Other Accounts of All Battles Fought Between the Navies of the United States and Great Britain during the Late War, an official account of the war published in 1816.[38]

The jugs belonged to Bass Otis (1784–1861), prominent portrait painter and “Father of American Lithography,” who in 1818 moved to a three-story house at 63 Cherry Street (fig. 24). It was in this house that Otis experimented with, and later perfected, lithography, the printing technique using acid-etched limestone plates as a printing base. Otis made his living primarily by painting portraits of local residents, but also copied numerous paintings of significant American leaders and events for clients interested in publically displaying their patriotism.[39]

Transfer-printed ceramics would certainly have interested Otis for their technical achievements, and their patriotic message would have appealed to him as well. These two jugs would have been fitting additions to his home or studio, and could have served as props in some of his work.

William Tucker and Joseph Hemphill Porcelain

A recounting of Philadelphia’s top ten ceramic finds would be incomplete without a mention of Tucker and Hemphill porcelain. While it is neither unique nor the most beautiful, its production marked a critical step in the development of porcelain manufacturing in America (fig. 25).

William Ellis Tucker first started experimenting with porcelain in the early 1820s in a small shop behind his father’s store on Market Street.[40] In 1827 he presented the first samples of his porcelain at the Franklin Institute as part of its annual exhibition of American manufacturing, where they were well received. Tucker and later Joseph Hemphill—who operated the factory after Tucker’s death in 1832—exhibited annually at the Franklin Institute until the factory operations ceased in 1838. Records from the exhibitions note the gradual improvement in the quality of Tucker’s porcelain over time, but it was not until 1833 that it was finally considered “equal, if not superior, to that of the imported.”[41]

There are likely hundreds of examples of Tucker-Hemphill porcelain from archaeological sites in the city, but attributions are rare. Sherds of ambiguous white soft-paste porcelain are difficult to distinguish from one another, and most have been identified by the archaeological catchall term Euro-American porcelain, an attribution that includes American, French, and German products. The dish and jug shown here are likely what most Philadelphians who purchased Tucker-Hemphill porcelain in local shops encountered (fig. 26). Both are blanks, that is, undecorated and lacking the gilding and/or floral enamels that adorn the well-known examples in private and museum collections.

Russell F. Weigley, Nicholas B. Wainwright, and Edwin Wolf, eds., Philadelphia: A 300-Year History (New York: W.W. Norton, 1982), pp. 1–2.

Marie Basile McDaniel, “Immigration and Migration (Colonial Era),” The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, http://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/immigration-and-migration-colonial-era (accessed September 19, 2016).

Jean R. Soderlund, ed., William Penn and the Founding of Pennsylvania, 1680–1684: A Documentary History (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press for the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1983) pp. 53–54; Susan E. Klepp, “Demography in Early Philadelphia, 1690–1860,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 133, no. 2 (June 1989): 94–95; Gary B. Nash, The Urban Crucible: Social Change, Political Consciousness, and the Origins of the American Revolution (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1979), p. 409.

Robert Greenhalgh Albion, The Rise of New York Port, 1815–1860 (1939; reprint, New York: Scribner, 1970), p. 5; Klepp, “Demography in Early Philadelphia.”

Early ceramics researchers such as John Spargo and Edwin Atlee Barber recognized the importance of Philadelphia in the development of ceramic production in America. More recently, the results of archaeological investigations have led researchers to an increased appreciation of the work of Philadelphia’s potters. Susan H. Myers, “A Survey of Traditional Pottery Manufacture in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States,” Northeast Historical Archaeology 6, no. 1 (1977): 2.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe (Anniversary Oration Pronounced before the Society of Artists of the United States [Philadelphia: Bradford and Inskeep, 1811], p. 17) was the first to remark on the richness of intellectual life in Philadelphia: “. . . days of Greece may be revived in the woods of America, and Philadelphia become the Athens of the Western World.” See also “Athens of America,” The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, http://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/events/the-athens-of-america (accessed September 19, 2016).

Weigley et al., Philadelphia, pp. 166–280.

John L. Cotter, Daniel G. Roberts, and Michael Parrington, The Buried Past: An Archaeological History of Philadelphia (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992); Jed Levin, “Franklin Court, The President’s House, and Other Sites: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania,” in Archaeology in America: An Encyclopedia, vol. 1: Northeast and Southeast, edited by Francis P. McManamon (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2009), pp. 166–72.

French Huguenots like the Hillegas brothers, who made their way to America via Germany during this period, also brought with them potting traditions that were not dissimilar to their German counterparts.

An advertisement in the January 26, 1724, edition of American Weekly Mercury notes a parcel of ground “on the upper end of Chestnut Street . . . over against the Pott-House belong to Mr. Anthony Duchee [Duché]. . . .” Duché was also making red earthenware at his pottery, as indicated by waste material recovered from excavations at Independence Square behind the Pennsylvania State House (Independence Hall) and the Omni Site at the northwest corner of 4th and Chestnut Streets.

It has always been assumed that Anthony Duché Sr. was the master potter at his family pottery, although evidence of his being a potter has never been found. The first documented advertisement for Duché, in the American Weekly Mercury, December 21, 1721, identifies him as a “Glover.” Throughout the 1720s and 1730s he regularly advertised textiles and fabric-related services such as dying, pressing, souring, and printing fabrics from his Front Street store. His occupation is often listed as “Dyer” in those advertisements.

Duché stoneware has been recovered from a number of sites across the Old City district, including 8 and 114 South Front Street, New Market, 121–123 Market Street, and various sites at Independence National Historical Park, including Franklin Court, Area F, and the National Constitution Center. Other excavated examples were collected by independent “diggers” and are known to exist in private collections.

While Duché likely produced a variety of products, only three forms—tankard, chamberpot, and jug—have been identified.

“Votes and Proceedings of the House of Representatives of the Province of Pennsylvania,” quoted in Pennsylvania Archives, 8th ser., vol. 3 (October 14, 1726–September 22, 1741), edited by Gertrude MacKinney (Philadelphia, 1931), p. 2047.

Although Duché and/or his family continued to operate the pottery until 1764, the pottery was on the market twice, first in 1734 and again in 1737. The motivations behind these attempts to sell are unknown.

Stenton is approximately six miles outside of the eighteenth-century center of Philadelphia in Germantown. While today it is well within the city limits, historically it was part of the so-called Liberty Lands, where many wealthy Philadelphians constructed country seats. Stenton is currently a historic house museum administered by the National Society of Colonial Dames of America in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

Laura Keim and David Orr, “Indian at Stenton: A Trail Left in Slip on a Redware Bowl,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2008), p. 297.

Juliette Gerhardt et al., Life on the Philadelphia Waterfront, 1687–1826: A Report on the 1977 Archaeological Investigation of the Area F Site, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (West Chester, Pa.: John Milner and Associates, 2006), pp. 65–68. The Annis privy was designated YOHC1, AS I with a terminus post quem (tpq) of ca. 1750.

Colonial Williamsburg has a beaker, saucer, and dish with this pattern in its collection: http://emuseum.history.org/view/objects/asitem/search@/13/title-asc?t:state:flow=7a1a6518-ece4-42be-964c-0d40d10708c5 (accessed February 21, 2017). The pattern is based on a drawing in Pierre Pomet’s A Compleat History of Drugs (London, 1712), which itself was a copy of the original drawings from Pomet’s earlier French edition, Histoire Generale des Drogues, 3 vols. in 1 (Paris, 1694).

Cotter et al., The Buried Past, pp. 159–60.

Diana Edwards and Rodney Hampson, White Salt-Glazed Stoneware of the British Isles (Suffolk, Eng.: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2005), pp. 188–19.

Dennis Pickeral, “The Proper Equipage: Tea and Tea Ware at James Logan’s Stenton,” master’s thesis, Department of American Studies, Pennsylvania State University, Harrisburg, 2008, pp. 11–12; Rodris Roth, Tea Drinking in 18th-Century America: Its Etiquette and Equipage, Contributions from the Museum of History and Technology Paper 14, United States National Museum Bulletin 225 ([Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution], 1961).

Ivor Noël Hume, “An Indian Ware of the Colonial Period,” Quarterly Bulletin of the Archaeological Society of Virginia 17, no. 1 (1962): n.p.

Leland Ferguson, Uncommon Ground: Archaeology and Early African America, 1650–1800 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1992), pp. 3–22.

Gary B. Nash, Forging Freedom: The Formation of Philadelphia’s Black Community, 1720–1840 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1988), p. 2.

Keri Sansevere, “On Common Ground: An Examination of Colonoware in the Northeast,” paper presented at the annual meeting of the Council for Northeast Historical Archaeology, Long Branch, New Jersey, November 6–9, 2014.

For further reading, see Graham Hood, “Bonnin and Morris of Philadelphia: The First American Porcelain Factory, 1770–1772,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2007), pp. 6–75.

Ibid., p. 10.

Two teabowls and a saucer were excavated from a shared privy at 1–3 Gray’s Alley, designated archaeological feature YohF1, AS I-III with a tpq date of 1766, at the Area F site in Old City. For more information, see Gerhardt et al., Life on the Philadelphia Waterfront, 1687–1826, pp. 57–58. A saucer was excavated from the New Market site, Area 5B, Feature 29; see Barbara Liggett, Archaeology of New Market: Excavation Report (Philadelphia, Pa.: The Athenaeum of Philadelphia, 1981), p. 164. A third saucer, counted here, was uncovered just outside of the present limits of the city at the Printzhof site, on Tinicum Island by the Philadelphia airport; see Robert Hunter and Jeffrey Ray, “A Bonnin and Morris Waste Bowl,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2007), pp. 185–87. Two sauceboats were recovered from the National Constitution Center site in Feature 142; for results of analytic testing, see J. Victor Owen, Andrew Meek, and William Hoffman, “Geochemistry of Sauceboats Excavated from Independence National Historical Park (Philadelphia): Evidence for a Bonnin and Morris (c.1770–73) Provenance and Implications for the Development of Nascent American Porcelain Wares,” Journal of Archaeological Science 38, no. 9 (2011): 2340–51. A saucer and waste bowl (or small punch bowl) were recently discovered in a privy at 103 Callowhill Street in the Northern Liberties, just north of the eighteenth-century city boundary. The objects are owned by Matthew Dunphy and Melissa Dunphy, the property owners.

Robert Hunter and Juliette Gerhardt, “An Eighteenth-Century American True-Porcelain Punch Bowl,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2016), p. 191; J. Victor Owen, Joe Petrus, and Xiang Yang, “Bonnin and Morris Revisited: The Geochemistry of a True Porcelain Punch Bowl Excavated in Philadelphia,” in ibid., pp. 201–19; J. Victor Owen, John D. Greenough, and Nick Panes, “Statistical Evaluation of Analytical Data for Eighteenth-Century American and British Sulphurous Phosphatic Porcelains,” in ibid., pp. 163–78.

Queensware development was encouraged as early as 1792, when the Pennsylvania Society for the Encouragement of Manufactures and Useful Arts announced a competition for domestic earthenware and stoneware production. A January 25, 1792, advertisement in the New Jersey Journal called for “such person as shall exhibit the best specimen of Earthenware or Pottery, approaching nearest to Queensware, or the Nottingham or Delf [sic] ware, of the marketable value of fifty dollars—a plate of the value of fifty dollars, or an equivalent in money. . . .” For more details, see Edwin Atlee Barber, Salt Glazed Stoneware, Primers of Industrial Art (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1907), pp. 25–26. There were numerous queensware potteries operating in the city from ca. 1795–1820; this article highlights the two most successful producers.

Edwin Atlee Barber, The Pottery and Porcelain of the United States: An Historical Review of American Ceramic Art from the Earliest Times to the Present Day, 3rd ed., rev. and enl. (1909; reprint, [New York]: Feingold & Lewis, distributed through J & J Publishing, 1976), p. 111. Trotter was making queensware as early as 1808 at the Columbian Pottery.

Philadelphia Aurora General Advertiser, February 10, 1812, p. 5, quoted in Susan H. Myers, Handcraft to Industry: Philadelphia Ceramics in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century, Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology 43 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1980), pp. 78–79. John Mullowny was a brickmaker by trade but employed an English-trained potter, John Charlton, to make queensware in the early years of his endeavor.

For more on engine turning in early-nineteenth-century Philadelphia, see Deborah L. Miller, Meta F. Janowitz and Allan S. Gilbert, “Identifying Red, Brown, and Black Philadelphia ‘China’ through Compositional Analysis: Initial Results,” American Ceramics Circle Journal (forthcoming, 2017).

To our knowledge, Philadelphia queensware has been identified only in archaeological contexts and no known identified examples are in museum or private collections. The first detailed discussion of Philadelphia queensware from an archaeological perspective was published in John Bedell, Ingrid Wuebber, Meta Janowitz, Marie-Lorraine Pipes, Sharla Azizi, and Charles H. LeeDecker, Farm Life on the Appoquinimink, 1750–1830: Archaeological Discoveries at the McKean/Cochran Farm Site, Odessa, New Castle County, Delaware Department of Transportation Archaeology Series 156 (1999), pp. 216–20.

A jug and teapot with purple enameled decoration were excavated from the Independence Visitor Center and National Constitution Center sites in Independence National Historical Park.

The USS United States was built in Philadelphia at Humphreys’ Shipyard in Southwark, now the Philadelphia Navy Yard, by naval architect Joshua Humphreys. Humphreys was commissioned by the United States Navy to build its first six frigates.

Abel Bowen, comp., The Naval Monument: Containing Official and Other Accounts of All Battles Fought Between the Navies of the United States and Great Britain during the Late War (Boston: A. Bowen, 1816). See also Deborah Miller and Ronald Fuchs, “The War of 1812 on Pots: Two Pearlware Jugs from Philadelphia,” American Ceramics Circle Newsletter (2012): 4–5. The interpretation in the ACC newsletter was based on early analysis of Feature 142, the privy behind 63 Cherry Street in which the jugs were discarded. Initial analysis suggested that the jugs may have belonged to Caleb Canby and his family, who lived at the site beginning in the late 1820s. This was significant because Canby’s mother-in-law, Elizabeth Claypoole, better known as Betsy Ross, lived at the house from 1822 until her death in 1836. New analysis based on Mean Ceramic Dates for the privy points to the jug being discarded in the late 1810s–early 1820s.

Thomas Knoles, The Notebook of Bass Otis, Philadelphia Portrait Painter, Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society 103, pt. 1 (Worcester, [Mass.]: American Antiquarian Society, 1993), p. 192, available online at http://www.americanantiquarian.org/proceedings/44517814.pdf (accessed August 3, 2016).

Barber, Pottery and Porcelain of the United States, p. 127.

Myers, Handcraft to Industry, p. 102.