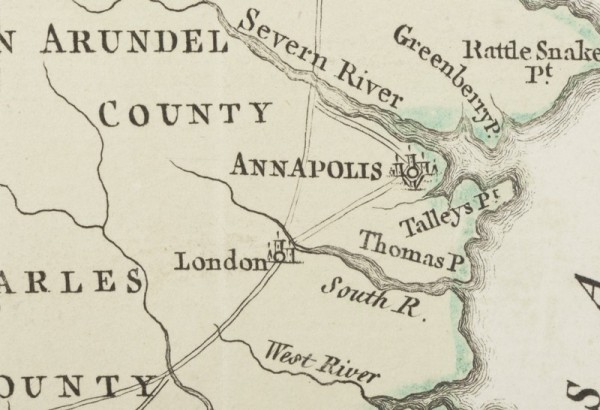

Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson, Map of the Most Inhabited part of Virginia, containing the whole province of Maryland with part of Pensilvania, New Jersey and North Carolina (detail), 1754. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.) The map shows the close proximity of London Town to Annapolis.

The Edward Rumney/Stephen West Tavern cellar during archaeological excavations, 2001. (Photo, Al Luckenbach.) The William Brown House and Tavern at Historic London Town can be seen in the distance.

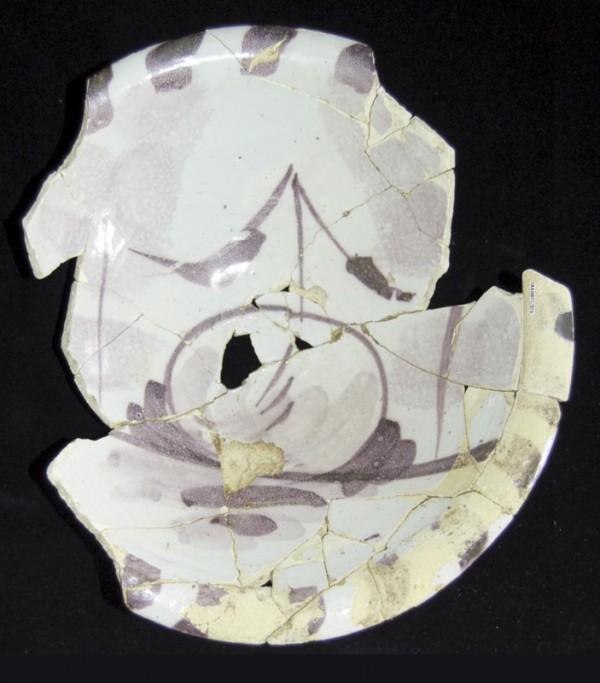

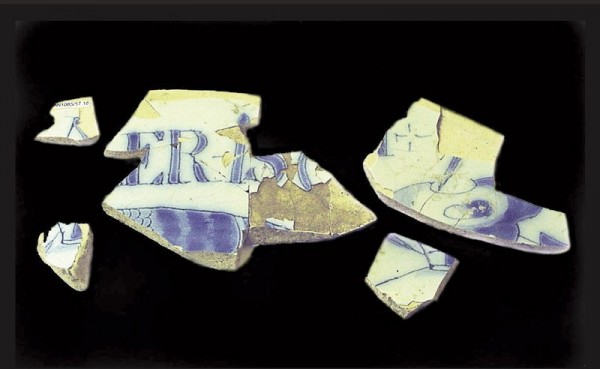

Amorial plate, Portugal, tin-glazed earthenware. D. 10 3/8". (Courtesy, Maryland State Archives; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The fragments of this complete vessel were found on the floor of the cellar at the Broadneck site.

The Great Seal of Talbot County, Maryland. The design was originally based on the Lloyd family arms.

Crumhorn (“crooked horn”) pipe, attributed to Emmanuel Drue, Providence, Maryland, ca. 1650–1669. Low-fired earthenware. L. 4 13/16". (Courtesy, Anne Arundel County Lost Towns Project; photo, Shawn Sharpe.) This highly decorated, unique form is considered to be a presentation piece made by Drue.

Three pieces of a pipe with a distinctive, very large heel termed Drue Type C. These sherds were excavated at the Burle site at Providence nearly a decade before the stamp on the right was recovered at Swan Cove. (Photos, Gavin Ashworth.)

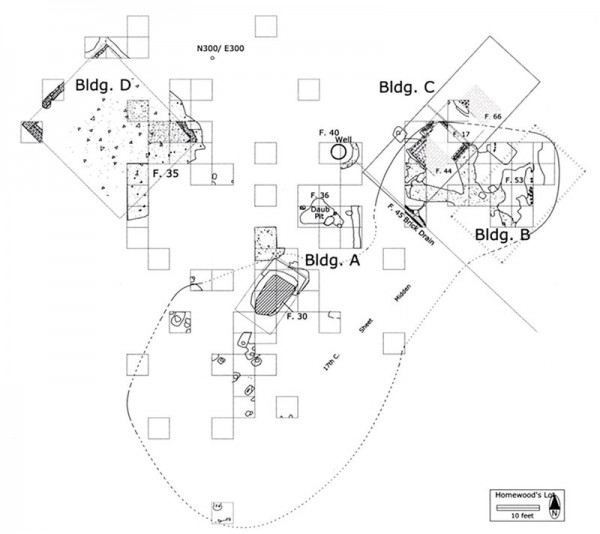

Archaeological site plan showing building sequence at Homewood’s Lot (18AN871), 2004. (Courtesy, Anne Arundel County Lost Towns Project.) Evidence for five separate buildings were discovered with construction dates between ca. 1650 and ca. 1700.

Mid-drip candlestick fragments, probably England, 1660s. Tin-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Anne Arundel County’s Lost Towns Project; photo, John E. Kille.) These fragments were recovered from Homewood’s Lot “Building A” cellar.

Erin Cullen excavating the brick cellar under “Building D” at Homewood’s Lot, in 2002. (Photo, Al Luckenbach.)

Bowl fragment, Netherlands, ca. 1640–1680. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 10". (Courtesy, Anne Arundel County’s Lost Towns Project; photo, Al Luckenbach.)

The Calvert House, State Circle, Annapolis, Maryland, 2016. (Photo, Al Luckenbach.)

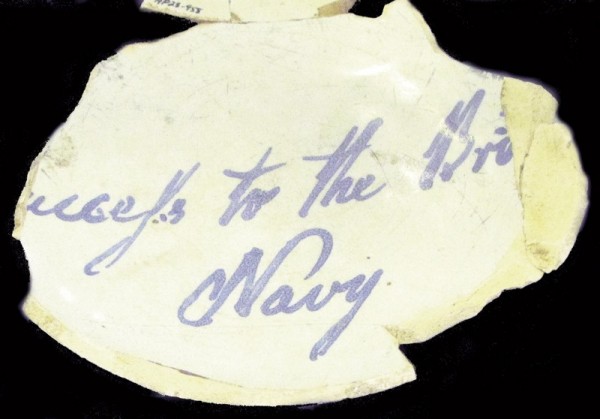

Punch bowl fragment, probably Liverpool, England, ca. 1754–1765. Tin-glazed earthenware. L. 6". (Photo, Al Luckenbach.) This fragment is part of a larger number of archaeologically derived vessels on display at the Calvert House.

Tankard, Westerwald, Germany, 1750s–1760s. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 6 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Al Luckenbach.) This remarkably intact vessel was excavated by bulldozer.

Wine bottle, England, 1750s–1760s. Glass. H. 9 1/2". (Courtesy, Anne Arundel County Lost Towns Project; photo, Shawn Sharpe.)

Punch bowl fragments, probably Italian, early eighteenth century. Max. L. 4". (Courtesy, Anne Arundel County Lost Towns Project; photo, Al Luckenbach.)

Punch bowl fragments, London, England, early eighteenth century. Max. L. 2 1/2". (Courtesy, Anne Arundel County Lost Towns Project; photo, Shawn Sharpe.) These fragments from a single vessel represent the only ceramics from the courthouse cellar at London Town..

Tin-glazed earthenwares recovered from the Rumney/West Tavern cellar. (Courtesy, Anne Arundel County Lost Towns Project; photo, John E. Kille.) This tightly dated ca. 1725 context produced a total of thirty-seven vessels.

Spiked bowl fragment, England, ca. 1725. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. of spike 1 1/4". (Courtesy, Anne Arundel County Lost Towns Project; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This so-called pineapple bowl may have held butter or sugar instead. Note the interesting use-wear patterns that appear on the three edges of the pyramidal spike.

Tankard, attributed to John Dwight, Fulham, London, England, ca. 1720. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 6 1/2". (Courtesy, Anne Arundel County Lost Towns Project; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Beverage vessels, Fulham, London, England, ca. 1720. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Anne Arundel County Lost Towns Project; photo, John E. Kille.) The ten salt-glazed vessels recovered from the Rumney/West Tavern cellar are important for their early date.

Coffeepot fragments, England, ca. 1720. Lead-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Anne Arundel County Lost Towns Project; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These English brown and off-white fragments include part of the handle and the acorn-shaped finial from the lid.

Coffeepot fragments from the Rumney/West Tavern arranged on a wire frame in the shape of the original vessel for a stoneware exhibition at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.) The reconstruction is now on display at Historic London Town in Edgewater, Maryland.

The Severn and South Rivers run parallel courses as they drain into the Chesapeake Bay in central Anne Arundel County, Maryland. During the seventeenth century, towns developed on each river: on the South, London Town was legislatively established in 1683 as a potential port of trade (fig. 1); on the Severn, the 1649 settlement of Providence eventually transformed into modern Annapolis. Despite being situated a mere three and a half miles apart “as the crow flies,” the towns had drastically different fates.

London Town quickly grew into the most important tobacco port in Maryland, and was even considered as a locality for the colonial capital, to replace St. Mary’s City. But by the time of the Revolutionary War, it had become a near ghost town, important only for its ferry crossing. The growing political importance of nearby Annapolis and the loss of economic activity to the new seaport of Baltimore were followed by the disruptions of trade caused by the war with England. By the nineteenth century, London Town was virtually no longer on the landscape, one of a number of “lost towns” in the region.

Annapolis, on the other hand, became the state capital in 1695 and remains so. It is a thriving tourist destination and a recreational boating gateway to the Chesapeake.

As a consequence of the English Civil Wars, the year 1649 was clearly difficult for Lord Baltimore (1605–1675), a Catholic and proprietor of Maryland. King Charles I, who had “given” him the colony (first settled in 1634, partially as a refuge for Catholics), was beheaded by the soon-to-be-victorious Protestant Parliamentarians. This development led Lord Baltimore to take three immediate steps in an attempt to maintain possession of his colony: he appointed a Protestant governor; he passed a law to grant religious freedom to all who believed in the Trinity in order to protect the religious liberty of Maryland’s Catholics; and he invited a group of Nonconformist Puritans from the Nansemond River area of Virginia to settle in Maryland.

The Puritans established the Providence settlement in 1649, at the mouth of the Severn River, with “Town Lands,” “Town Creek,” and a “Town Path” leading to the interior. As the population of St. Mary’s City had greatly declined in the 1640s, Providence became the main population center of the Maryland colony. By 1695 the colonial capital had moved away from St. Mary’s City, reflecting this new reality on the Severn River.

Providence town lands were established on both sides of the Severn River. Although portions were located directly under what is today urban Annapolis, the bulk of the settlement was on the northern bank. Over time, and through an impressive number of name changes (Providence, Severn, Proctor’s, Arundelton, Anne Arundel Town, Annapolis), the main population and urban center concentrated on the southern bank and remain there today.

For more than thirty years the University of Maryland and Historic Annapolis have sponsored the “Archaeology in Annapolis” program at numerous sites in the city, under the direction of Mark Leone, and these investigations have concentrated on lots associated with eighteenth- and nineteenth-century structures. One clearly stands out in terms of its ceramic assemblage: the excavations in 1982 by Anne Yentsch at the Calvert House, where a large grouping of early-eighteenth-century vessels was recovered and is now on permanent display in the hotel lobby of the Calvert House.[1]

The seventeenth-century origins of Annapolis are much better preserved on the north bank of the Severn River, where Anne Arundel County’s “Lost Towns Project” conducted extensive investigations. Over the course of more than a decade, eight sites were discovered that clearly were part of the early Puritan settlement of Providence and provide the best ceramic evidence for the first fifty years of what eventually became Annapolis.[2]

The Lost Towns Project also spent over a decade (1993–2011) excavating six urban house sites on lots at London Town on the South River. The most impressive ceramic assemblage was encountered during the work conducted at the site of the Edward Rumney/Stephen West Tavern (fig. 2).[3] Today, some of the excavated structures have been reconstructed in a county-owned park, to augment the surviving William Brown House and Tavern.

Given the intensity of archaeological investigations in Annapolis and London Town over the years, one can select from a wide variety of vessels for an article highlighting important examples. The ten ceramic objects described below represent only a partial representation of those found, many of which have made important contributions to our understanding of ceramic history.

Broadneck Plate

Based on the artifactual data, the Broadneck House is one of the earliest contexts discovered in the town of Providence, where it was built and apparently abandoned during the 1650s. Discovered in an eroded setting, little remained of this approximately 36-by-16-foot house but two subfloor pits containing ash, food remains, and discarded artifacts.

On the excavated cellar floor of what had been the house were stacked the broken sherds from a large Portuguese tin-glazed plate, which, when reconstructed, proved to have an armorial design bearing a lion rampant (fig. 3).[4] Although expressions of lions rampant are relatively common in Portuguese tin-glazed products—only sometimes associated with specific families—this example is a match for the arms of Edward Lloyd, the first commander of the Providence settlement.

Edward Lloyd eventually moved to Talbot County, Maryland, where he established the famous Wye Plantation, whose family silver and tombstones can still be seen with this design. Talbot County eventually adopted this particular lion-rampant arms as its county seal (fig. 4).

The late Ivor Noël Hume once called this plate “unquestionably one of the most important examples of seventeenth-century tin-glazed earthenware yet found in America.”[5]

Crumhorn Pipe

One of the early Providence settlement sites, Swan Cove (18AN934), proved to be one of the region’s most important contributors to Maryland’s ceramic history, with the discovery of the production of tobacco pipes fired from local clays.[6] Although described as a “planter,” Emmanuel Drue, the site’s occupant from 1661 to 1677, must have had an extensive home industry to produce such pipes. The only documentary clue is a reference in his inventory to “two pipe molds—brass,” but excavation of the site yielded extensive evidence of kiln firings, including ceramic muffles tempered with broken pipe stems, kiln furniture, and pipe wasters.

Drue clearly was producing two basic styles of pipes, undoubtedly related to the two brass molds. The first is an angular elbow form (often highly decorated), a familiar tobacco-pipe shape in the Chesapeake region; the second is a traditional footed belly-bowl form that corresponds more directly with European types. Decoration of the belly-bowl form was usually confined to rouletting of the rim. That this form was produced from local white clays has important implications as they are indistinguishable from imported products. The angular elbow form, on the other hand, was often fired from deliberately mixed and sometimes marbleized clays of brown, green, pink, and white, some of which were obtained as far as fifteen miles from the kiln site.

In addition to his two mold-produced types Drue also created special hand-form pipes, such as the one shown in figure 5. Similar in shape to rare Dutch crumhorn pipes, this piece was decorated by multiple stamps. In fact, one of the stamps used on this pipe was recovered during the excavation of Drue’s kiln (fig. 6). Other pipe fragments with this stamp had first been seen years earlier at the house site of Drue’s neighbor Robert Burle.[7] At the time it was assumed to be a Native American product, but now it can be seen as another of Drue’s special pipes, perhaps one he presented to his neighbor.

Homewood’s Lot Candlestick

Salvage archaeological investigations at the site of Thomas Homewood’s town lot in Providence were conducted in anticipation of the construction of a new home. At the time, an existing house and the ruins of a late-eighteenth-century structure were visible, and ultimately the excavations revealed five earlier structures that had occupied the location beginning in the 1650s (fig. 7).[8]

The earliest structure discovered at Homewood’s Lot (designated Building A) had a subfloor cellar that had been used for the disposal of ash and trash. This feature, filled circa 1660–1680, contained an interesting and varied ceramic assemblage that included Rhenish blue and gray salt-glazed stoneware, North Devon and Staffordshire earthenwares, and decorated and undecorated tin-glazed earthenware. Among the latter were the remains of three identical porringers as well as fragments of plates and bowls.[9] Perhaps the most unusual vessel, however, was a rare tin-glazed earthenware candlestick with mid-drip pan and trumpet base (fig. 8).

A similar plain example, attributed to mid-seventeenth-century Southwark, is illustrated in Britton’s London Delftware.[10] A corresponding candlestick in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, dated 1648 and decorated with the arms of the Fishmongers Company, is purported to be the earliest dated example.

Such candlesticks are based on metal prototypes in gold, silver, and brass, but candlesticks of any kind were considered a luxury in the New World. Like many of the items recovered from Providence town sites, this candlestick provides further evidence that the town’s connection to the transatlantic tobacco trade offered its citizens access to the latest luxury goods despite their frontier location.

Homewood’s Cherry Bowl

The third building constructed on Homewood’s Lot, designated as Building C, was built around 1700. Even though it had a more substantial brick foundation and cellar, the structure was abandoned and its cellar filled with debris around 1750 (fig. 9). One of the vessels recovered from this cellar was a Dutch tin-glazed bowl with a single cherry rendered in purple manganese with broadly painted dashes for rim decoration (fig. 10). This rim treatment clearly places the vessel as a contemporary of the famous “blue dash chargers” dating to circa 1640–1680.[11]

Two interesting points can be made with reference to this bowl. The first involves the amount of time such a vessel can be serviceable in a household, since it was not discarded until nearly a century after its manufacture. The second reflects the strong cultural connection between the Protestant Netherlands and the Puritan town of Providence. A significant amount of Dutch material culture, notably including basic building materials like bricks, floor tiles, and roofing pantiles, have been recovered during excavations. This degree of material interchange, which was forbidden by English trade laws, is notably lacking in other Chesapeake towns such as St. Mary’s City or Jamestown.

Success Punch Bowl

In 1982 the Archaeology in Annapolis program conducted salvage excavations at the Calvert House on State Circle across the street from the Maryland State House (fig. 11).[12] During these excavations they recovered an impressive assemblage of ceramics, principally delftware and white salt-glazed stoneware vessels that are now on display in the hotel lobby.

Although not as complete as many of the other ceramic finds recovered from the Calvert House excavations, one of the more interesting discoveries was the fragmentary base of a punch bowl inscribed “Success to the British Navy” (fig. 12). The bowl is part of a large group of delftware (and stoneware) produced to commemorate the French and Indian War (1754–1763).[13] Variations on the inscription included “Success to the British” (fleet, navy, flag) and “Success to the King of Prussia.” Examples of such vessels have been recovered from Colonial Williamsburg, among them a unique example inscribed “Success to the St. Olave Privateer.”[14]

The pro-English military punch bowl’s presence on State Circle in Annapolis can be seen as slightly ironic, given the revolutionary fervor that would overtake the town within the next few decades.

GR Tankard

One of the more spectacular ceramic vessels recovered in downtown Annapolis came from a less than ideal archaeological context. Decades ago, after a nineteenth-century structure on Prince George Street was destroyed by fire, a bulldozer operator was removing the remains of the associated cellar. He discovered that this cellar had been situated where an eighteenth-century cellar of different dimensions once stood. This had produced a void that still contained a number of intact eighteenth-century wine bottles and the Westerwald stoneware tankard shown in figure 13. Fortunately, a local avocational archaeologist happened by and managed to obtain the mug as well as a bottle for his private collection.

While the blue and gray salt-glazed stoneware tankard impressed with “GR” (for Georgius Rex, or King George) is a well-known form, this example is noteworthy for its remarkable condition, lacking any scratches or visible wear. A hole was placed in the handle to accommodate metal fittings, but this hole clearly was never used. It is a typical product of the Westerwald region of the Rhineland, decorated with incisions, stamps, and cobalt paint.

The shape of the wine bottles suggests that they date to the 1750s–1760s (fig. 14), which appears true for the date of manufacture for the GR Westerwald tankard as well.[15]

London Town Courthouse Punch Bowl

Unlike Annapolis, which eventually became a densely urban context, abandoned London Town converted to a suburban setting and a twenty-three-acre county-owned park, which encompasses nearly a fourth of the legislated town. As a result, archaeologists have had far greater opportunities to investigate intact contexts for early ceramics.

The best example of this is the cellar beneath the Rumney/West Tavern (see fig. 2), but other town sites provided interesting contrasts to that assemblage. For example, the impressive delftware assemblage at Rumney/West Tavern appears to derive almost exclusively from London potteries, mainly Vauxhall, whereas at the Larrimore site, on a plot part of the original acreage of London Town, contemporary tin-glazed vessels were recovered of Dutch, Portuguese, and even Italian manufacture (fig. 15).

One of the more interesting vessels outside the Rumney/West Tavern was found at what was the site of the Anne Arundel County Courthouse from 1684 to 1695. At this locality a small, subfloor pit contained a single ceramic vessel—a relatively large tin-glazed punch bowl. This polychrome decorated English bowl is unremarkable in its own right and is represented by only a half-dozen poorly preserved sherds (fig. 16). In addition, tremendous quantities of wine bottle fragments and tobacco pipes were also found within the pit. Surprisingly, evidence of food remains, including the usually ever-present oyster shells, were absent from the courthouse pit. The discovery within this specific context affirms that communal drinking and smoking were an important part of the judicial landscape during courthouse proceedings—an activity often described in period diaries and journals in Colonial America.

Pineapple Bowl

As mentioned, the Rumney/West Tavern cellar produced an amazing assemblage of tin-glazed earthenwares. Previously reported in the 2002 issue of Ceramics in America, these included teacups, coffee and punch bowls, and plates (fig. 17). The plates showed some indication of being “sets,” with four sunflower, three pagoda, and three mermaid motifs recovered. The mermaid motif was adopted as the symbol for Historic London Town, where the collection is now on display.

The most unusual delftware vessel is a basal fragment of a large punch bowl. What little remains of the exterior decoration consists of the same blue annular design seen on other bowls and most plates in the assemblage. On the interior a prominent, pyramidal spike projects centrally from the base (fig. 18). This feature shows clear use wear from impaling something at the bottom of the bowl. Similar bowls have been apocryphally called “pineapple bowls,” implying that a pineapple, or other fruit such as lemons or limes, might have been impaled on the bottom to create a punch. Other experts suggest that the spike may have served to keep butter from sliding around in the bowl.[16]

At least two examples of this unusual vessel type are extant in the Victoria and Albert Museum and in the Fitzwilliam Museum, and three fragments were recovered during the salvage excavations at Vauxhall, London.[17] Vauxhall appears to be the source of most of the tin-glazed vessels from the Rumney/West Tavern cellar.

As the first reported New World example, the presence of such a specialized vessel in a circa 1724 deposit in colonial Maryland attests to the high-end clientele at this tavern on the South River.

Fulham Tankard

An important white salt-glazed tankard attributed to the Fulham pottery established by John Dwight was among the vessels recovered during the excavation of the Rumney/West Tavern in London Town (fig. 19).[18] Part of its significance lies in the early date for this context. The tankard stands 6 1/2 inches high and has a brown iron-wash applied to the rim. Its knife-cut “double pyramid” handle terminal and the fine articulation of the turned base have been used to link it to Fulham.

Although the earliest known dated example of white salt-glazed stoneware is 1715, New World archaeologists usually cite 1720 as a start date for the appearance of the ware type in American contexts. As a consequence, the white salt-glazed tankard found within the cellar under the Rumney/West Tavern represents one of the earliest examples of Fulham white salt-glazed stoneware in this country, and stands apart from the later Staffordshire-made white salt-glazed wares found in most colonial ceramics assemblages. Using a statistical analysis of delftware design motifs, the deposit has been dated to 1724, which corresponds nicely to the property transfer between Rumney and West that year.[19]

At least eleven of these early white salt-glazed vessels from the Rumney/West Tavern were recovered, most with brown rims caused by dipping into an iron-rich slip (fig. 20). The assemblage includes at least seven tavern mugs, a pitcher, and three teabowls. One of these well-potted, thin teabowls was found lying next to its saucer.

Rumney’s Coffeepot

Although represented by only a few sherds, perhaps the most significant stoneware vessel from the Rumney/West Tavern site was a rare coffeepot with a distinctive conical form (fig. 21). The pot was lead-glazed, with the upper half dipped in an iron wash.[20] The distinctive “double glaze” is attributed to John Dwight’s son Samuel at the Fulham manufactory circa 1700–1710.[21]

Only a handful of such vessels are known to exist. The Rumney/West Tavern coffeepot was used in an exhibit on stoneware made and used in early America at Williamsburg (fig. 22), and is now on permanent display at Historic London Town.[22]

A white salt-glazed bowl was also recovered of a size that suggests its use as a coffee bowl. Similarly sized delftware bowls that could serve this purpose were also found. As with the delft “pineapple bowl,” the presence of a coffeepot and possible cups in a New World tavern context at this early date reveals much about the establishment and its clientele. The port of London Town had a number of taverns and ordinaries which undoubtedly served different social classes, but the Rumney/West Tavern, as indicated by this vessel as well as other artifacts, clearly catered to the higher echelon, including ship captains, tobacco merchants, and planters.

Ann Elizabeth Yentsch, A Chesapeake Family and Their Slaves: A Study in Historical Archaeology (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994).

Al Luckenbach, “Providence 1649: The History and Archaeology of Anne Arundel County, Maryland’s First European Settlement,” 1995, The Maryland State Archives and the Maryland Historical Trust.

Al Luckenbach, “Ceramics from the Edward Rumney/Stephen West Tavern, London Town, Maryland, Circa 1725,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2002), pp. 130–52.

Al Luckenbach, “The Seventeenth Century ‘Lloyd Plate’ from the Broadneck Site in Maryland,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2002), pp. 205–6. See also Al Luckenbach and Paul Mintz, “The Broadneck Site (18AN818): A 1650s Manifestation,” in Al Luckenbach, C. Jane Cox, and John Kille, eds., The Clay Tobacco-Pipe in Anne Arundel County, Maryland (1650–1730), published by the Lost Towns Project.

Personal communication, May 1991.

Al Luckenbach, “The Swan Cove Kiln: Chesapeake Tobacco Pipe Production, Circa 1650–1669,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2004), pp. 1–14.

Shawn Sharpe, Al Luckenbach, and John Kille, “Burle’s Town Land (ca. 1649–1676): A Marked Abundance of Pipes,” in Luckenbach, The Clay Tobacco-Pipe in Anne Arundel County, Maryland (1650–1730) (Annapolis, Md.: Anne Arundel County Trust for Preservation, 2002), pp. 28–39.

Lauren Franz and Al Luckenbach, “The Building Sequence at Homewood’s Lot, Anne Arundel County Maryland,” Maryland Archeology 40, no. 2 (2004): 19–28.

Al Luckenbach and John Kille, “Ceramic Treasures in Seventeenth-Century Trash: A 1660s Cellar Deposit,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2011), pp. 3–13.

Frank Britton, London Delftware (London: J. Horne, 1987), p. 117.

See Ivor Noël Hume, A Guide to Artifacts of Colonial America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1969), p. 108.

Yentsch, A Chesapeake Family and Their Slaves.

Amanda E. Lange, Delftware at Historic Deerfield: 1600–1800 (Deerfield, Mass.: Historic Deerfield, 2001), p. 52.

John C. Austin, British Delft at Williamsburg (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation in association with Jonathan Horne Publications, 1994), pp. 26–27.

Noël Hume, A Guide to Artifacts of Colonial America, pp. 66–67.

Michael Archer, Delftware: The Tin-Glazed Earthenware of the British Isles: A Catalogue of the Collection in the Victoria and Albert Museum (London: The Stationery Office, in association with the Victoria and Albert Museum, 1997), p. 314.

Frank Britton, English Delftware in the Bristol Collection (London: Sotheby Publications, 1982), p. 122.

Diana Edwards and Rodney Hampson, White Salt-Glazed Stoneware of the British Isles (Woodbridge, Suffolk, Eng.: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2004). See also Janine E. Skerry and Suzanne Findlen Hood, Salt-Glazed Stoneware in Early America (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 2009).

Al Luckenbach and John Kille, “Delftware Motifs and the Dating of the Rumney-West Tavern, London Town, Maryland (ca. 1724),” American Ceramic Circle Journal 12 (2003): 12–26.

Chris Green, John Dwight’s Fulham Pottery: Excavations, 1971–79 (London: English Heritage, 1979), p. 135.

Edwards and Hampson, White Salt-Glazed Stoneware of the British Isles, p. 19.

Skerry and Hood, Salt-Glazed Stoneware in Early America, p. 108.