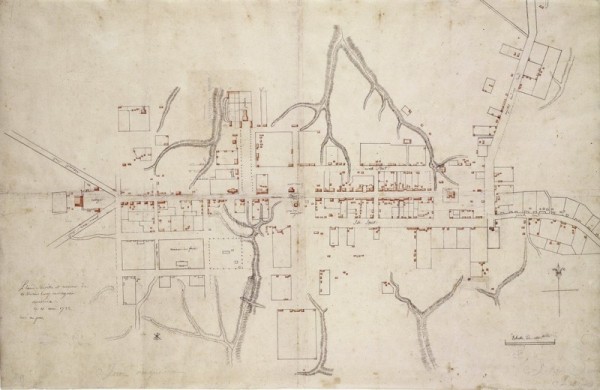

Plan de la ville et environs de Williamsburg en Virginie, America, May 11, 1782. 16 3/8 x 25 3/8". (Special Collections Research Center, Swem Library, College of William and Mary; photo, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

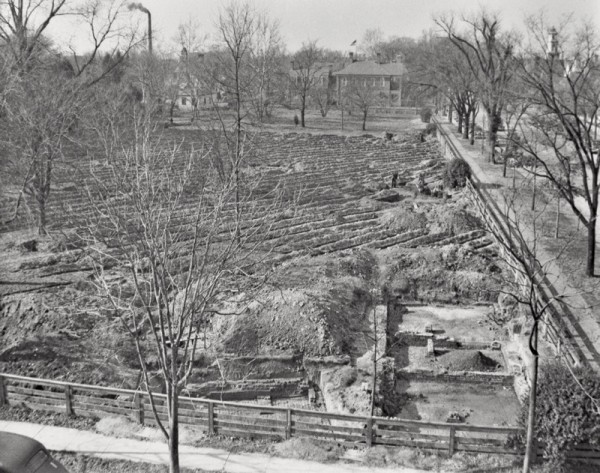

Early cross-trenching at the corner of Nassau Street (bottom) and Duke of Gloucester Street (right), mid-twentieth century. (Photo, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

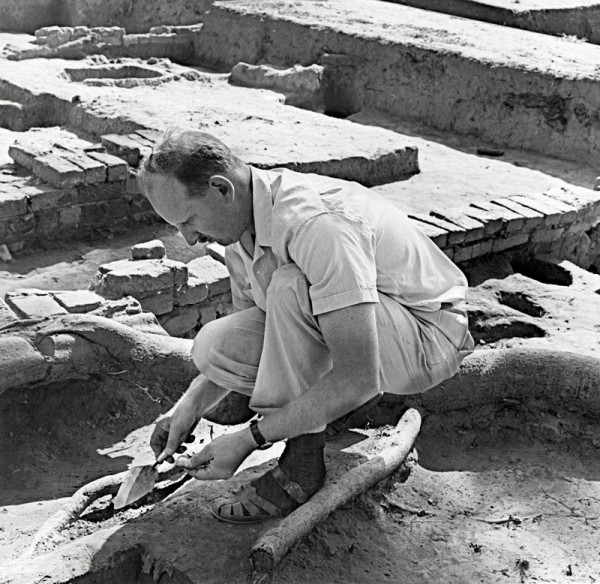

Ivor Noël Hume during excavations of Henry Wetherburn’s Tavern, 1965. (Photo, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Archaeologists Meredith Poole, Mark Kostro, and Andy Edwards excavating the Anderson Forge site, 2010. (Photo, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Flowerpot or vase, London, England, 1668–1700. Tin-glazed earthenware with Bleu persan decoration. H. 8 1/4". (Courtesy, Museum of London Archaeology, 23079.)

Flowerpot, probably London, England, 1680–1690. Tin-glazed earthenware with bleu persan decoration. (Photo, Robert Hunter.) Field photograph showing flowerpot excavation from the South Yard of the Wren Building at the College of William and Mary, 00008-16JA.

Teabowls, Jingdezhen, China, 1668–1700. Hard-paste porcelain. H. of bowl on left 1 3/4". Excavated from the site of the Governor’s Palace, 20AA-00261. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Attributed to Charles Bridges (1670–1747), Portrait of Alexander Spotswood, Spotsylvania County, Virginia, 1736. Oil on canvas, 48 1/8 x 38 5/8". (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Museum Purchase, 1940-359.)

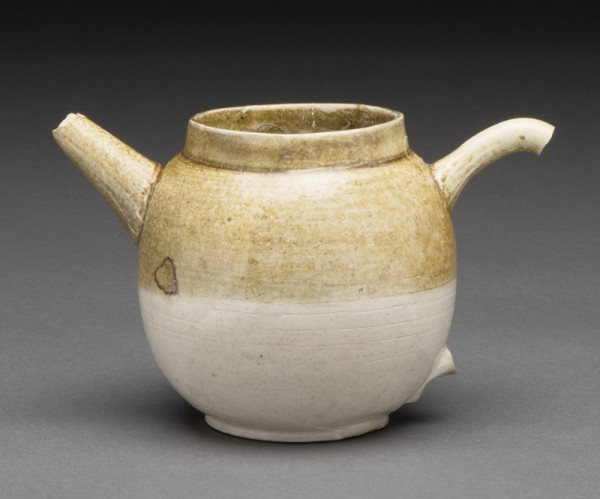

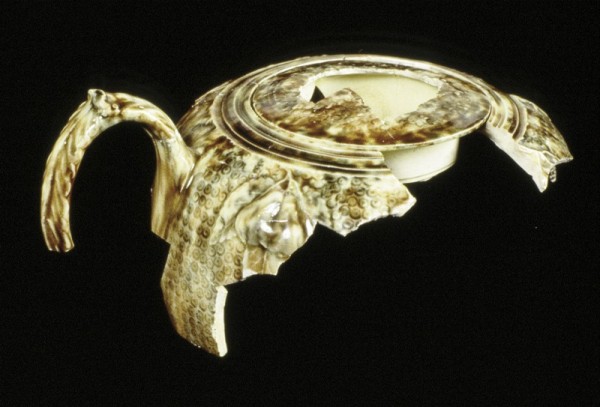

Teapot, attributed to John Dwight, Fulham, London, England, ca. 1700. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 3 3/4". Excavated from the site of the James Geddy House, 01204-19BB. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Pieter Brueghel the Younger (1564–1637/38), L’Auberge St. Michel, Brussels, Belgium, one of nine known versions painted between 1619 and 1634. Oil on panel, 20 1/4 x 33 1/4". (Courtesy, Sotheby’s.)

Martin pot or bird bottle, attributed to William Rogers’s pottery, Yorktown, Virginia, 1720–1745. Lead-glazed earthenware. L. 8 1/4". Excavated from the site of the James Geddy House, 3539.ER987D and 1329A-19.B. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Deckelterrine (covered tureen) missing cover, Westerwald, Germany, 1750–1775. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 1 7/8". Excavated from the site of the Anthony Hay house and cabinetmaking shop, 1526-28DB. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Storage jar, Westerwald, Germany, ca. 1750. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 9 3/4". Recovered from the site of John Coke’s Tavern, 0282-27AA. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Blumenkübel (flowerpot) fragments, Westerwald, Germany, 1740–1780. Salt-glazed stoneware. Excavated from the sites of the Peter Scott house and cabinetmaking shop, Ravenscroft, and the Moody House, 00039-13JA (Scott), 00526-28FA (Ravenscroft), and 00013-02CA (Moody). (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Blumenkübel (flowerpot), Westerwald, Germany, dated 1734. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 13". (Courtesy, Museum für Angewandte Kunst.)

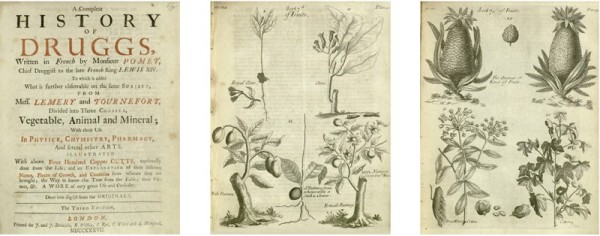

Pierre Pomet, A Compleat History of Druggs, 3rd ed. (London: Printed for J. J. Bonwicke, R. Wilkin, S. Birt, T. Ward, and E. Wicksteed, 1737), title page and pls. 46 and 54. (Courtesy, Boston Medical Library in the Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine.)

Dish, beaker, and saucer, Jingdezhen, China, ca. 1750. Hard-paste porcelain. D. of dish 14". (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Museum Purchase, Wesley and Elise H. Wright in memory of Mr. and Mrs. Henry Clay Hofheimer II and in honor of John C. Austin, 2012-79; The Buddy Taub Foundation, Dennis A. Roach and Jill Roach Directors, 2013-30a&b.)

Plate fragment, Jingdezhen, China, ca. 1750. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 6 1/4". Excavated from the site of the Chiswell-Bucktrout House, ER1568R.2H. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Plate fragment, Jingdezhen, China, ca. 1750. Hard-paste porcelain. Excavated from the site of the Raleigh Tavern, 17BC-00001. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Teapot, Staffordshire, England, 1750–1755. Lead-glazed earthenware, L. 3 3/4". Excavated from the James Geddy House site, Lot 161, 01665-19B. (Colonial Williamsbug Foundation.)

Teapot, attributed to Thomas Whieldon, Fenton, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1750. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 4 1/4". (© National Museums Scotland, A.1905.182.)

Plate, Staffordshire, England, 1760–1765. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 9 1/2". Excavated from the site of Henry Wetherburn’s Tavern, 01730-09NA. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Plate, Jingdezhen, China, ca. 1755. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 9 1/4". Excavated from the site of the Governor’s Palace, 20AA-01082. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Plate and pitcher fragments, probably manufactured in Staffordshire and printed in Liverpool, England, ca. 1783. Cream-colored earthenware. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Detail of the printed monogram for Philip and Ann Barraud that appears on the fragments illustrated in fig. 24.

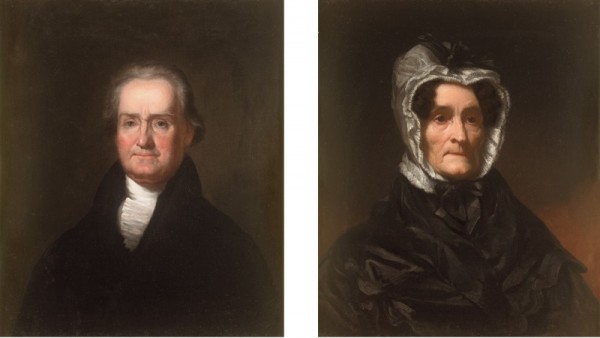

William James Hubard, Portraits of Dr. Philip Barraud and Ann Blows Hansford Barraud, Norfolk, Virginia, probably 1828–1830. Oil on canvas, 30 x 25". (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Museum Purchase, 1988-221, 1988-222.)

Sweetmeat or pickle dish fragment, Bow Porcelain Manufactory, London, England, 1760–1765. Soft-paste porcelain. H. 2 1/8". Excavated from the William Prentis House, 17DA-0017. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Sweetmeat dish, Bow Porcelain Manufactory, London, England, ca. 1765. Soft-paste porcelain. H. 5 1/8". (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Museum Purchase, Wesley and Elise H. Wright in memory of Mr. and Mrs. Henry Clay Hofheimer II and in honor of John C. Austin, 2012-88.)

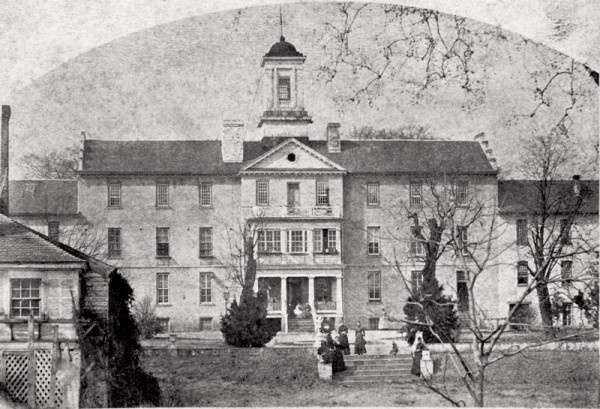

William Teiser, Eastern State Hospital (Public Hospital), Williamsburg, Virginia, ca. 1885. Black-and-white negative. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Wash basin, Sampson Bridgwood and Son, Ltd., Anchor Pottery, Longton, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1870. Earthenware. D. 14". Excavated from the site of the Public Hospital, ER1713.A.F.G.H.4C. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

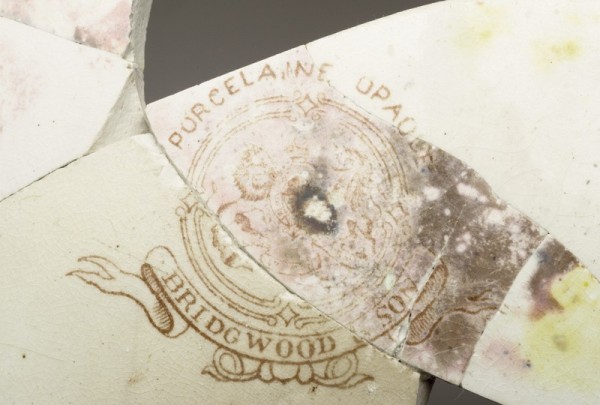

Detail of the mark found on the base of the wash basin illustrated in fig. 30.

Williamsburg, located in Tidewater Virginia between the James and York Rivers, was first settled in 1633. Governor John Harvey signed “An Act for the Seatinge of the Middle Plantation” in Jamestown to encourage consolidation of plantations on the York River with those on the James.[1] Over the next several decades political rebellion, the founding of the College of William and Mary, and fire helped shift the focus of political and economic power from Jamestown to Middle Plantation. When the Jamestown statehouse burned again in 1698, the decision was made to relocate the colonial capital and in 1699 Governor Francis Nicholson and the assembly passed “An Act directing the Building the Capitoll and the City of Williamsburgh.” It was further outlined that the area “shall be for ever hereafter called and known by the Name of the City of Williamsburgh” (fig. 1).[2]

As capital of the largest and most populous of the American colonies, Williamsburg was an important and thriving city during the eighteenth century. It was never a large municipality; the population increased and decreased in direct relationship to whether the government was in session. Over the course of the century Williamsburg and her residents were directly involved with and impacted by changes in politics and growing unrest. The Declaration of Independence and beginning of the Revolutionary War brought great change to the city, but perhaps no change was greater than the decision in 1780 to relocate the seat of Virginia government to Richmond. At the close of the century Williamsburg was described variously as not appearing “to be a place of much business, rather the residence of gentlemen of fortune,” as well as “dull, forsaken, and melancholy.” From 1800 until the early twentieth century Williamsburg was home to two important organizations—the College of William and Mary and the Public Hospital, an institution dedicated to the care and treatment of the mentally ill—but primarily it was simply a small town.

In 1926 the Reverend Dr. W.A.R. Goodwin, rector of Bruton Parish Church, an eighteenth-century Episcopal church in the center of Williamsburg, shared his dream of preserving the city’s historic buildings with John D. Rockefeller Jr. Shortly thereafter the restoration of Williamsburg began when Rockefeller purchased the Ludwell-Paradise House, the first of many eighteenth-century buildings to be acquired by what would become the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. From the early days of the organization, Colonial Williamsburg was interested in re-creating as much of the eighteenth-century streetscape as possible. This resulted in digging trenches on sites where colonial buildings were thought to have been in the hopes of finding foundations (fig. 2). Ceramics, glass, metals, and other artifacts recovered from these trenches during this process were sometimes preserved, but it was not until the 1950s that a more formal and scientific archaeology program was established under the direction of Ivor Noël Hume (fig. 3).

It would be difficult to overstate Noël Hume’s role in shaping not only the archaeology program in Williamsburg, but also our understanding of the colonial capital as a whole. He focused on the systematic retrieval of all artifacts, not just those that were pretty or unusual or might enhance an architectural reconstruction. Noël was a prolific author publishing numerous books and articles for academic and nonprofessional audiences alike. His passion for archaeology and the objects unearthed by it shaped Colonial Williamsburg and generations of scholars and collectors. In 1959, just one year after Noël arrived in Williamsburg, John C. Austin began his career at Colonial Williamsburg, first as a cataloger and eventually as curator of ceramics and glass. John used information gathered by Noël and his colleagues to influence the types of objects he acquired for the decorative arts collection. Decades later, the determination “we know it was here because of archaeology” is still one of the strongest reasons to add a particular ceramic object to the collection. Williamsburg may be “one of the most extensively studied eighteenth-century Anglo-American towns in the world,” but there is still much to learn.[3] Our understanding of the diversity of ceramics owned and used in eighteenth-century Williamsburg continues to grow as more is revealed (fig. 4). “With more than 85 years of excavation behind us, it might seem safe to assume that all of the archaeological work has been completed. In fact, this is nowhere close to true. Only an estimated 15 to 20% of the Historic Area’s 301 acres have been fully excavated.”[4]

Unusual Delft

During the seventeenth century, the art of the garden flourished in France and, by influence, in royal courts throughout Europe. Garden design during this period was both fanciful and elaborate, and an important component of the designs was the incorporation of portable ceramic containers for trees, shrubs, and plants. Most of these urns were made of tin-glazed earthenware in imitation of Chinese porcelain (fig. 5). In France the potters of Nevers were particularly successful in producing pieces worthy of Versailles and other palaces.[5] Huguenot designer Daniel Marot took the French baroque style with him when he moved first to the Low Countries and eventually to England in his work for King William and Queen Mary. Mary was particularly enamored with flowers both in and out of doors, as well as with delft flower containers. This passion for ceramic garden ornaments eventually encompassed most people of gentility in both England and the American colonies.

Bleu persan, also known as bleu de Nevers, is a particular type of faience that was popular during this period. Earthenware covered with an opaque-blue tin glaze and decorated with designs in a pure-white tin glaze was first made in Persia as early as the fourteenth century. It was copied in many regions of Europe, but perhaps nowhere as successfully as at Nevers during the mid-seventeenth century.[6] English potters in London and Brislington began imitating these pieces about 1670. Bleu persan was a desirable but uncommon decoration on delft in colonial America.

A flower urn excavated from the south yard of the Wren Building at the College of William and Mary is particularly interesting in that it combines the seventeenth-century fascination with gardens and delft flower containers with fashionable bleu persan (fig. 6). This flower urn and two other bleu persan vessels were recovered from the site of a sawpit that had been dug during the 1710s by carpenters repairing and rebuilding the college building after a 1705 fire. The pit was filled quickly and closed by 1720.[7]

A limited number of objects decorated in this manner has been recovered from other sites in America, including a pre-1715 context at Newington Plantation, South Carolina; the Humphrey Chadbourne House (ca. 1690) in South Berwick, Maine; St. Mary’s City, Maryland; and a seventeenth-century domestic site adjacent to the Chiswell House in Williamsburg.[8]

Sanskrit in Virginia

Given Williamsburg’s cultural importance, most people living there in the eighteenth century owned at least one or two pieces of Chinese export porcelain. Ownership of this type of ceramic was one way for colonial Virginians to express their growing affluence and participation in the larger consumer world. A pair of teabowls (fig. 7) recovered from the site of the Governor’s Palace was likely owned by Lieutenant Governor Alexander Spotswood, who served in Virginia from 1710 until 1722 (fig. 8).[9] In 1716 he was the first to reside in the Governor’s Palace. In addition to the teabowls’ connection to a lieutenant governor and their recovery from the highest style home in Williamsburg, they are important because of their decoration. The bowls are ornamented in underglaze blue over the entire exterior surface with a simplified version of the Sanskrit character for om.[10] The design is arranged over the surface in three ranks of concentric circles. On the more intact vessel, the same character as on the exterior is written once on the bottom of the interior. Sanskrit is a liturgical language used in Hinduism and Buddhism. It appears on a number of Chinese porcelains in Southeast Asia and India. On wares decorated similarly, the organization of the design is meant to be read like a pray wheel: as the bowl is rotated, the prayer is released.[11]

Fragments of a similar bowl were excavated from a sixteenth-century colonial Spanish settlement at Santa Elena, on Parris Island, South Carolina. Two nearly identical examples were recovered from the seventeenth-century sites Jamestown Island and Bacon’s Castle in Surrey, Virginia, and yet another was excavated at Johnson Hall, the site of an eighteenth-century home built by Sir William Johnson in Johnstown, New York.[12] It seems unlikely that the North American consumers of these porcelains were aware of the connection between the decoration on their teabowls and Hindu and Buddhist religious practice, but it does raise questions about how these vessels made it to the eastern seaboard of what would become America.

Were European merchants offered these bowls along with all those wares more closely associated with European trade? The traditional market for vessels decorated in Sanskrit was India, Tibet, and Southeast Asia. The Dutch were the only Europeans trading directly with China in the eighteenth century, whose base of operations was located in Southeast Asia at Batavia, what is now Jakarta, Indonesia.[13] Perhaps some of these Sanskrit-decorated wares were shipped to Indonesia for use there but instead made it onto Dutch ships bound for the West. There is at least one Dutch earthenware plate known that is decorated with these same designs, suggesting that enough of these wares made it to Europe to be copied by potters there.[14]

The Earliest White Salt-Glazed Stoneware Teapot Excavated in America

Tea was an important indicator of status and wealth from the time it was introduced into England in the seventeenth century. “In the late seventeenth century, consuming tea in a moderately ceremonious and quasi-Chinese way, using, if possible, porcelain cups and teapots imported from China, was a very significant ritual of gentility.”[15] It is not surprising that wealthy American colonists sought to continue a style of gentility that they had grown accustomed to in England, or for American-born gentry to seek to emulate the fashions of the day.

William Byrd of the Westover plantation on the James River kept detailed diaries from 1709 until 1741. Byrd was a prominent man in society who regularly traveled to Williamsburg to meet with members of the government, among them Virginia’s Royal Governor, Alexander Spotswood. When alone Byrd seems to have consumed tea primarily as a treatment for illness, but when he entertained guests of status or met on business, tea was included in the refreshments. Although he drank tea and was familiar with the rituals associated with consuming it, in those years it was not commonplace and certainly was not yet served every morning and afternoon.[16]

Not only is this circa 1700 teapot a very early example of the form in Williamsburg, it is also the earliest white salt-glazed stoneware teapot excavated in America (fig. 9). It was found at the James Geddy House site in a context dating 1730–1740. Modeled after a Chinese prototype, the teapot is made of white-slipped clay with a thin iron brown wash covering its upper half. It is attributed to John Dwight on the basis of archaeological evidence from the excavations of his Fulham pottery site.[17] The period of the factory’s production of white stoneware was limited to about 1685 to 1710.[18]

It is unclear whether this early teapot was brought from Scotland by James Geddy when he relocated to Williamsburg, or was owned by Samuel Cobbs, a licensed ordinary keeper who purchased the lot in 1716 and built the first house on the property. Samuel and his wife, Edith, were married in 1717 and by 1719 they had left Williamsburg for what was to become Amelia County, Virginia.[19] What is certain is that it is one of only four known white stoneware teapots made at John Dwight’s Fulham factory that was used in Williamsburg at a time when tea drinking was still a “mode of behavior exhibited by people who consciously wished to signify that they were ‘gentlemen’ and ‘ladies,’ that they possessed the manners of the hereditary aristocracy and pedigrees sufficiently distinguished to allow them to be accounted members of that class.”[20]

A Reexamination of the Bird Bottle

Earthenware pots or bottles designed to serve as nesting boxes for birds are documented in Europe as early as the sixteenth century. An early example was excavated in Zutphen, Netherlands, and several seventeenth-century examples have been recovered in London.[21] Archaeological and pictorial evidence suggests they were in use throughout the seventeenth and into the eighteenth centuries. Depictions of starling pots, as they are known in the Netherlands, appear in paintings such as Pieter Brueghel the Younger’s L’Auberge St. Michel, where they are grouped together under the eaves (fig. 10).

The presence of bird bottles in eighteenth-century Williamsburg is perhaps not surprising given their popularity in Europe, but archaeological evidence in North America is uncommon. An imported bird bottle was excavated in Philadelphia at the New Market East site from a privy pit associated with the Quaker Meeting on Pine Street, between Front and Second Streets. The contents of the privy range in date from about 1755 to 1780.[22] No imported examples have been recovered in Williamsburg, but several fragments of locally produced martin pots have been excavated at the James Geddy House (fig. 11), the ravine assemblage recovered at the Thomas Everard House site, and the Henry Wetherburn’s Tavern site. Additionally, an example was found bricked into the chimney of an outbuilding at Green Spring near Jamestown.[23]

Martin pots were advertised for sale in the Virginia Gazette along with other locally made earthenware and stoneware on March 12, 1752, “at a store near the church in Williamsburg” and they appear listed as “Bird Bottles” in the Williamsburg estate inventory of tavernkeeper John Burdett in 1746.[24] Based on archaeological evidence from the kiln site, all of the martin pots found in Williamsburg are attributable to the William Rogers pottery located in Yorktown just thirteen miles away. William Rogers owned and operated an earthenware and stoneware manufactory beginning in the 1720s.[25] His manufactory supplied English-style vessels to the region, including items listed in the 1752 advertisement mentioned above—“milk pans, cream pots, juggs, and bottles.” When Rogers died in December 1739 “4 doz bird bottles” were listed on his inventory.[26]

Since the mid-1960s Colonial Williamsburg has sold thousands of reproduction bird bottles based on the Rogers example excavated at the James Geddy House. First published in 1967, the form was described as a “nesting place for martins presumably to encourage the birds to dispose of marauding mosquitoes.”[27] Period writings indicate that nesting pots were intended to attract passerines such as martins, swallows, starlings, and sparrows for use as a food source, a use less appealing for twenty-first-century consumers.[28] Clay nest sites were hung beneath the eaves of houses “to induce sparrows to nest there, and facilitate the collection of eggs and young.” In Scandinavia and Italy during the nineteenth century bird bottles were used “under the eaves . . . to encourage Starlings to nest and provide a harvest of young for the table.”[29]

Eighteenth-century receipt books list numerous preparations for songbirds, including recipes on how to pot small birds, the preparation of a sauce for larks, and how to pickle sparrows. Cookery books that include such delicacies—among them The Compleat Housewife and The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy—were available in colonial America, and the 1705 publication The History and Present State of Virginia by Robert Beverley listed wildfowl available for consumption in the colony: “plover, larks, and many other good birds for the table that they have not yet found a name for . . . and an infinity of small birds.”[30]

A Variety of German Stoneware

Salt-glazed stoneware made in the Westerwald region of Germany comprises an important and sizable percentage of vessels excavated in Williamsburg. The majority of stoneware produced in the Westerwald was manufactured in the small towns of Höhr and Grenzhausen, known today as one municipality, Höhr-Grenzhausen. Tankards, jugs, and bottles were exported in large quantities to England and then on to the American colonies for the duration of the century alongside English vessels of the same type. The main difference between these otherwise utilitarian forms was the high level of decoration present on the Westerwald examples when compared with fairly plain English goods. Tureens, two-handle storage jars, and flowerpots are less common forms, but they too were an important part of the German stoneware owned and used in Williamsburg and elsewhere in America.

Shallow, flat-bottomed bowls with two handles have been recovered from two locations, the Anthony Hay house and the Governor’s Palace (fig. 12).[31] This shape is unknown in English ceramics and only recently have connections been made to the German Deckelterrine, or covered tureen, consisting of a low bowl with two handles and a flat-topped lid. The absence of a knop on the lids of these forms suggests that both halves of the vessels were intended to be used in serving at the table. The small size of the example excavated from the Hay house indicates that perhaps this piece was intended to serve as a sauce tureen. Westerwald stoneware, like Chinese export porcelain, was exported in large quantities and to a wide variety of markets, which increased the likelihood of the development of forms and styles targeted to specific markets. The covered tureen might have been intended for consumers in the Low Countries, where this form was in more common use.[32]

Flat-bottomed, double-handled, wide-mouthed gray storage jars from the Westerwald served as basic storage containers used for putting up a wide variety of foodstuffs (fig. 13). Such mundane vessels are likely candidates to have been the items listed as “Dutch stone . . . butter pots and pickling jars” in James and Drinker’s Pennsylvania Gazette advertisement of 1767.[33] Several unusually decorative Westerwald storage jars have been excavated in Williamsburg from the home of Captain Edward Champion Travis and the site of John Coke’s Tavern. In the last decades of the eighteenth century, American potters began to make similarly shaped storage jars with cobalt decoration, but the origins of those vessels were undeniably rooted in traditions emanating from the Rhineland.

Archaeological fragments confirm that Blumenkübel—large, urn-shaped gray stoneware flowerpots made in the Westerwald—were used in homes and gardens in early America (figs. 14, 15). Examples have been found at several locations in Virginia, including Monticello and five sites in Williamsburg.

Westerwald stoneware was a functional ware available to a broad cross-section of the populace, and was, perhaps more than any other type of ceramic, a primary influence in the burgeoning American stoneware industry. Specialized forms like these were less common, but they played an important role as the popularity of German stoneware persisted until the end of the century. In fact, specific references to Rhenish stoneware were found in more newspaper advertisements during the last three decades of the eighteenth century than all the previous years combined.[34]

Botanical Images on Chinese Porcelain

The eighteenth century saw a flourishing of the Enlightenment in Europe and, by extension, the American colonies. The fascination with the natural world led in part to a deep investigation into natural history and botany. More than one hundred botanical books were published in Europe in the first fifty years of the century. The illustrations used for those volumes were incorporated into the period’s textiles, wallpaper, silver and porcelain.[35]

While botanical imagery was a popular decorative motif on English porcelain during the mid-eighteenth century, however, comparable imagery was seldom depicted on Chinese export porcelain. Among the only known examples of Chinese porcelain decorated with motifs drawn directly from botanical prints—a pineapple and nutmeg and clove sprigs taken from Pierre Pomet’s A Compleat History of Druggs, originally published in French in 1694 and translated into English in 1712 (fig. 16)—are those illustrated in figure 17.[36] The decoration is closely matched to the original prints, suggesting that at least one copy of Pomet’s publication, or perhaps pages from it, reached Jingdezhen. The pattern appears to have been popular both with the English and the Dutch trade. The Griffin, an English East India Company ship that sank off the coast of the Philippines in January 1761, contained a saucer and beaker ornamented with this design.[37] In 1769 a Dutch East India Company order included 984 flat plates and 399 soup plates in a pattern described as “with the pineapple,” which likely was this pattern.[38]

Similarly decorated examples have been recovered from at least three colonial American sites, including three dinner plates found in a Philadelphia privy associated with an early house at 13 Gray’s (Morris) Alley. The privy’s 1750 closure indicates that the plates were deposited there more than ten years before the Griffin shipwreck, when the house was occupied by William and Patience Annis. William Annis was a sea captain who traveled regularly around the Atlantic world, and he could have purchased the plates on a trip to England.[39] The other two were recovered in Williamsburg at the site of John Chiswell’s house, built in 1750. Chiswell was a member of the House of Burgesses from Hanover Country, Virginia. The smaller fragment was found in 2016 during an excavation exploring the footings for a porch in front of the Raleigh Tavern (figs. 18, 19).

In many ways these objects embody the very best of eighteenth-century refinement and culture. Chinese porcelain, the most desirable of the ceramic types, bearing images fueled by the Enlightenment, depicting botanicals from exotic locales, all summed up in vessels that were used in colonial Virginia.

“. . . a Variety of Fruit Pattern Wares . . .”

Colonial Americans primarily used ceramics imported from England. Probate inventories and archaeological evidence indicate that the people of eighteenth-century Williamsburg were no different. Newspaper advertisements suggest a brisk trade in fashionable ceramic wares, especially with regard to the consumption of tea. The often-quoted advertisement for the firm Balfour & Barraud placed in the Virginia Gazette on July 25, 1766, contains a lengthy list of goods—tea, coffee, and chocolate as well as metal and ceramic objects used for the preparation and service of those beverages. Of particular note is the section that lists “mugs, coffee cups, butter tubs and stands, colliflower do. tea and cream pots, enamel, tortoise . . . .”[40] While this is one of the earliest advertisements in Virginia for wares decorated with metallic oxides in imitation of tortoiseshell, those types of ceramics were already well known in the colonies. Thomas Whieldon of Fenton, Staffordshire, first recorded in his memorandum book in 1749 that he had made this type of ware. Whieldon is the first potter known to use the term tortoiseshell, but he was just one of many potters who made these wares.[41] Advertisements in Boston and South Carolina newspapers listing tortoiseshell wares appear as early as 1754 and 1756, respectively.

Teaware decorated with so-called tortoiseshell colors was not uncommon in the colonies by the mid-eighteenth century. The teapot illustrated in figure 20 is unusual because of its molded design, often known today as the “bird’s eye and fruit” pattern. This example, recovered from a well on the site of the James Geddy House, is quite rare. The well in which it was found appears to have been filled between 1765 and 1775.[42] The only other known teapot in this pattern, attributed to Thomas Whieldon, has been given a date of circa 1750 and is in the collection of the National Museum of Scotland (fig. 21).[43] Perhaps it is indicative of what Benjamin and Edward Davis advertised for sale in the Boston Gazette on June 13, 1768, when they stated that they had just imported from Liverpool “A fresh assortment of neat cream-colour’d wares; also Agate, Tortoise, Mellon, Collyflower, new Pine-Apple and a Variety of Fruit Pattern Wares. . . .”[44]

Four plates in this pattern, more commonly found in green glaze, were recovered from a well at the site of Henry Wetherburn’s Tavern, also in Williamsburg (fig. 22). The material found in that well suggests that it was filled between 1765 and 1770.[45] The deep, rich green found on these plates was achieved by the use of copper oxide and is mentioned by Josiah Wedgwood in his experiment books in 1759.[46] Like Whieldon’s reference to tortoiseshell, while Wedgwood’s discussion of green glaze indicates his pottery produced it, it should not be assumed that he was the only—or even the first—Staffordshire potter to do so. In addition to imported examples, it seems that John Bartlam, a Staffordshire potter who relocated to South Carolina, also produced green-glazed plates with this design; fragments dating to the late 1760s were excavated at the site of his Cain Hoy pottery near Charleston.[47]

Bespoke Services

In the eighteenth century, bespoke, or custom-made, ceramics were costly, luxurious household items, just as they are today. Chinese export porcelain and transfer-printed, cream-colored earthenware were fashionable wares even when they weren’t made to order. Most people in England purchased sets of dishes for dining or tea off the shelf rather than custom-ordered them. While there was a greater number of affluent consumers in eighteenth-century England than in America who could afford personalized ceramics, bespoke ceramic tea and table services were present in households in colonial and early America as well.

Chinese export porcelain dinner services often included 250 to 350 pieces, composed of dinner plates, soup plates, graduated serving dishes, soup tureens, and sauce tureens. This armorial porcelain plate was part of a service ordered by John Murray, Earl of Dunmore, who brought the service from Scotland to Williamsburg in 1770 when he took up the post of Royal Governor of Virginia (fig. 23). This plate and fragments from several other pieces were recovered archaeologically from seven sites in Williamsburg, suggesting that the service was widely dispersed after Lord Dunmore and his family fled Williamsburg in 1775. This is the only known Chinese export porcelain armorial service with a history in eighteenth-century Williamsburg.

Cream-colored ware was highly fashionable and was used by many wealthy inhabitants of the Chesapeake, among them Lord Botetourt, Royal Governor of Virginia from 1768 until 1770. A number of creamware vessels survive from the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries that were additionally embellished for American-market clients with their initials and monograms. Among those are archaeological fragments from a service owned by Williamsburg residents Philip and Ann Barraud (fig. 24). Philip Barraud married Ann Blows Hansford on July 23, 1783, and it is likely that the bespoke dinner service was commissioned to celebrate that event. The Barraud service is unusual not only because it was a special order, but also because all of its design was printed, including the initials “PAB” (fig. 25). The fact that the monogram was printed suggests that a full service was ordered to warrant the extra expense of engraving a copper plate. The Barraud creamware was most likely printed in Liverpool, the most active port in the transatlantic trade during the second half of the eighteenth century.

Philip Barraud was originally from Norfolk, Virginia. He was a member of a French Huguenot family and his father, Daniel Barraud, was a successful merchant known today primarily for his partnership with James Balfour. The Norfolk firm of Balfour & Barraud advertised fashionable imported goods in the Virginia Gazette from at least 1766 until 1770. Archaeological investigations of the property where Dr. and Mrs. Barraud resided in Williamsburg revealed a ceramics assemblage “heavily weighted towards expensive tablewares, with half of the vessels comprised of creamware or pearlware, and over a third . . . Chinese porcelain.”[48] Barraud was not formerly trained as a doctor, but he gained medical training during the American Revolution and after the war he moved to Williamsburg and began a medical practice in partnership with apothecary James Galt. The Barrauds moved back to their hometown of Norfolk in 1798 (fig. 26).[49]

While the vast majority of ceramics exported to America during this period was for the general trade, Dr. and Mrs. Barraud’s earthenware and Lord Dunmore’s porcelain were both investments that indicated status and wealth beyond the means of most of their contemporaries.[50]

Dessert on Display

Fashionable dining in the homes of the wealthy elite during the eighteenth century, both in England and the American colonies, often involved two savory courses followed by an elaborate dessert. A wide array of specialized forms were developed to help showcase the fanciful creations served during dessert: molds to create pyramids of jelly, glasses for syllabub, ice cream molds, dishes and glass pyramids to display marzipan animals, and baskets and dishes for sweetmeats.[51]

The middle of the century saw the confluence of a fascination with the natural world and more elaborate desserts, resulting in the development of ceramic vessels, often of soft-paste porcelain, that reflected those two interests. In the 1755 Chelsea sale catalog a list of items from a dessert service includes cabbage leaves and basins, vine-leaved dishes, sunflower leaves, and vessels in the form of partridges, melons, and cauliflowers.[52] Shells singly and in groups were also popular during this time. A proposed table setting from Charles Carter’s The Complete Practical Cook (1730) illustrates a dessert table along with suggestions for where to place different dishes and the types of foods to serve. It includes “pyramids of fruit of sorts in porcelain,” which could be candied fruits in shell-shaped dishes of the type excavated from the site of the William Prentis House in Williamsburg (figs. 27, 28).[53]

Prentis was born in Norfolk County, England, in 1699. By 1725 he was in Williamsburg and married to Mary Brooke, daughter of John Brooke, an ordinary keeper in Williamsburg. The couple lived in a home conveyed to them by John Brooke in 1724 and inherited the property after Brooke’s death in 1729. William Prentis was engaged in a mercantile business with John Blair and Wilson Cary until his death in 1765.[54] The inventory taken upon Prentis’s death indicates that he owned a larger number of high-status items, including china and silver.[55] The Bow sweetmeat dish was certainly in keeping with the quality of goods listed on the inventory.

English porcelain was, on the whole, more expensive than Chinese porcelain and was not common among the residents of Williamsburg. However, it was present in larger amounts than might be expected.[56] Chelsea porcelain was listed in Governor Botetourt’s possessions at the time of his death in 1770 and Peyton Randolph’s widow, Elizabeth Harrison Randolph, owned a “set of Chelsea Tea China” at the time of her death.[57] Advertisements indicate that Bow was not only sold in the colonies, but that at least on occasion it was singled out and listed specifically rather than simply as English china. In 1754 Philip Breading of Boston had just imported “a variety of Bow China, cups and saucers, bowls, etc.,” and in that same city two years later a public auction selling the household goods of the late Mr. William Merchant included “Bow China Ware” among the list of goods. Bow was the only specific manufacturer listed in the advertisement.[58]

Sanitation and Sanity

The Public Hospital for Persons of Insane and Disordered Minds, later called Eastern State Hospital (Public Hospital), opened in Williamsburg in 1773 (fig. 29).[59] It was the first public institution dedicated to the care of the mentally ill in America. The original building consisted of twenty-four cells, an apartment for a live-in keeper, and a meeting room.[60] The treatment of those with “disordered minds” changed dramatically over the course of the next century, and the Public Hospital transformed with the times, significantly expanding to meet the needs of the community. A new set of directors took over the running of the institution in 1865, and in their 1870 report to the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Virginia the directors detailed some of the improvements, including that they had completed additional bathrooms “each furnished with bath tub, with hot and cold water, earth closet, slop hopper, and wash basin” (fig. 30).[61] A number of advances in sanitation and hygiene, particularly for the poor, was part of the social agenda of wealthy crusaders in England and America during this time.[62]

Most toilet wares used in America during the middle of the nineteenth century were manufactured in Staffordshire. This basin is marked “PORCELAINE OPAQUE / BRIDGWOOD & SON” for the firm of Sampson Bridgwood and Son, first recorded in 1805 and located at the Anchor Pottery in Longton (fig. 31). Their particular specialty was the manufacture of earthenware under various trade names, such as “semi-porcelain,” “porcelaine opaque,” and “limoges.” In 1880 The Pottery Gazette, American and Canadian Edition published the firm’s advertisement for “Dinner and Toilet Services &c., in Porcelaine Opaque or White Granite. Every article of the highest quality. Plain and slightly decorated goods.”[63]

Bridgwood marketed primarily to American and Canadian audiences, as detailed in the nineteenth-century publication The Ceramic Art of Great Britain: “services are made partly for the home but principally for the United States and Canadian markets. In earthenware white granite is made for the United States, Australian, and Canadian trades.”[64] In fact advertisements in American newspapers from the 1860s and 1870s suggest that Sampson Bridgwood and Son was a well-known firm among American consumers.[65] In 1876 The Philadelphia Inquirer ran an advertisement for the new firm of L. Straus & Sons, china merchants located in Philadelphia, Paris, and New York, that indicated they had Bridgwood for sale, alongside Minton, Copeland, Wedgwood, Haviland, and Baccarat, among others.[66] The presence of a Sampson Bridgwood & Son wash basin at the Public Hospital suggests that the directors placed a high priority on the care and treatment of their patients, even down to stocking wares produced by a well-regarded Staffordshire manufacturer. On June 7, 1885, the main building of the hospital was destroyed in a fire. This basin was excavated from the rubble of that fire, along with a wide variety of glass, metal, and other ceramic objects used to support the well-being of the mentally ill in nineteenth-century Williamsburg.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The work compiled here would not be possible without the efforts of archaeologists at Colonial Williamsburg past and present who toil tirelessly to bring the past to life. I am deeply grateful to them. This article benefited from the assistance of a great number of people. Particular thanks go to Andy Edwards, Ron Fuchs, Robert Hunter, Rod Jellicoe, Angelika R. Kuettner, Kelly Ladd-Kostro, Debbie Miller, Meredith Poole, Janine E. Skerry, and Emily Williams. Thank you especially to Jorin and HP, who support me in all things.

George Humphrey Yetter, Williamsburg Before and After: The Rebirth of Virginia’s Colonial Capital (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1988), p. 14.

Ibid., pp. 14–17.

Roderick Jellicoe with Robert Hunter, “English Porcelain in America: Evidence from Williamsburg,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2007), p. 165.

Meredith Poole, “A Short History of Archaeology at Colonial Williamsburg,” http://research.history.org/research/archaeology/history/ (written in 2001 and updated 2014).

Camille Leprince, “French Baroque Faience and André Le Nôtre’s Gardens,” American Ceramic Circle Journal 19 (2017): 25, 31.

Michael Archer and Brian Morgan, Fair as China Dishes: English Delftware from the Collection of Mrs. Marion Morgan and Brian Morgan (Washington, D.C.: International Exhibitions Foundation, 1977), p. 41.

Communication with Andrew C. Edwards, RPA, March 30, 2016.

John C. Austin, British Delft at Williamsburg (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation in association with Jonathan Horne Publications, 1994), pp. 18, 105, 201. For more on the Chadbourne Site, see http://oldberwick.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=category&id=42&Itemid=62 (accessed September 27, 2017).

Suzanne Findlen Hood, “Broken Objects: Using Archaeological Ceramics in the Study of Material Culture,” in Writing Material Culture History, edited by Anne Gerritsen and Giorgio Riello (London: Bloomsbury, 2015), pp. 67–72.

William Y. Willetts and Lim Suan Poh, Nonya Ware and Kitchen Ch’ing: Ceremonial and Domestic Pottery of the 19th–20th Centuries Commonly Found in Malaysia (Selangor, Malaysia: Southeast Asian Ceramic Society, 1981), pp. 6, 54–57.

See, e.g., a porcelain bowl in the British Museum, made in Jingdezhen, China, Wanli (mark and period), Ming dynasty, 1573–1620, porcelain with underglaze-blue decoration, H. 3 1/8". (The British Museum, Franks.759). It is decorated with a single large angular Tibetan character in the center and five concentric rings of characters in the cavetto; six rings of similar characters are inscribed outside. The base carries a six-character Wanli reign mark.

Linda R. Pomper, J. Legg, and C. B. DePratter, “Chinese Porcelain from the Site of the Spanish Settlement of Santa Elena, 1566–1587,” Vormen uit Vuur (2011): 37; J. B. Curtis, “17th- and 18th-Century Chinese Export Ware in Southeastern Virginia,” Transactions of the Oriental Ceramic Society 53 (1988–89): 54–55; David Sanctuary Howard, New York and the China Trade (New York: New-York Historical Society, 1984), pp. 62–63.

Rose Kerr and Luisa E. Mengoni, Chinese Export Ceramics (London: V&A Publishing, 2011), pp. 6–7.

Willetts and Poh, Nonya Ware and Kitchen Ch’ing, p. 6.

Woodruff D. Smith, “Tea and the Middle Class,” in Steeped in History: The Art of Tea, edited by Beatrice Hohenegger (Los Angeles: Fowler Museum at UCLA, 2009), p. 139.

Barbara G. Carson, “Determining the Growth and Distribution of Tea Drinking in Eighteenth-Century America,” in Steeped in History, pp. 160–61.

John Dwight was a successful manufacturer of brown stoneware by the time he ventured into new territory with the development of white salt-glazed wares. The earliest items, like this example, were fabricated of either white or pale-colored clay, the latter being covered with a coating of white slip or liquid clay, also known as engobe. Evidence of mugs, tankards, teacups, teapots, and coffee cups dating from the 1680s onward has been found among the materials excavated from Dwight’s factory. Jonathan Horne was the first to recognize this teapot as a product of the Fulham pottery. I am grateful to him and to Chris Green for their assessment of this piece. Before the excavations of Dwight’s Fulham pottery site, the teapot was attributed to Staffordshire and dated to ca. 1730–1740. Ivor Noël Hume, “Rise and Fall of English White Salt-Glazed Stoneware,” Antiques 97, no. 2 (1970): 250, fig. 4.

Janine E. Skerry and Suzanne Findlen Hood, Salt-Glazed Stoneware in Early America (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 2008), pp. 66, 108–9.

Harold B. Gill, Jr., James Geddy House Historical Report: Block 19, Building 11, Lots 161 & 162, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series 1442 (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library, 1967); “Cobb or Cobbs Family,” William and Mary Quarterly 19, no. 1 (1910): 51–56.

Smith, “Tea and the Middle Class,” p. 138.

John G. Hurst, David S. Neal, H.J.E. van Beuningen, Pottery Produced and Traded in North-West Europe, 1350–1650, Rotterdam Papers 6 (Rotterdam, Netherlands: Stichting “Het Nederlandse Gebruiksvoorwerp,” 1986), pp. 144–45; W. F. Grimes, The Excavation of Roman and Mediaeval London (New York: Praeger, 1968), pp. 73–75; Sylvia Pryor and Kevin Blockley, “A 17th-Century Kiln Site at Woolwich,” Post-Medieval Archaeology 12 (1978): 73–77; Museum of London Database, http://collections.museumoflondon.org.uk/online, s.v. “A24784,” “245BR87,” “A10396,” “73.162,” and “A11658” (accessed September 29, 2017).

John L. Cotter, Daniel G. Roberts, and Michael Parrington, The Buried Past: An Archaeological History of Philadelphia (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992), pp. 158–61.

Green Spring, a property once owned by Philip Ludwell whose 1767 probate inventory contained “Martin potts.” “Appraisment of the Estate of Philip Ludwell Esqr Decd,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 21, no. 4 (1913): 415; Audrey Noël Hume, Archaeology and the Colonial Gardener, Colonial Williamsburg Archaeological Series 7 (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1974), pp. 83–86.

Virginia Gazette, no. 63, March 12, 1752, p. 3; “Inventory and Appraisment of the Estate of John Burdett decd. Augst. 27th 1746,” Colonial Williamsburg Digital Library, http://research.history.org/DigitalLibrary/view/index.cfm?doc=Probates\PB00333.xml&highlight=Burdett (accessed September 29, 2017).

Norman F. Barka, Edward Ayres, and Christine Sheridan, The “Poor Potter” of Yorktown: A Study of a Colonial Pottery Factory, Vol. 3, Ceramics, Yorktown Research Series 5 (Denver, Colo.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1984), pp. 352–56; Norman F. Barka, “Archaeology of a Colonial Pottery Factory: The Kilns and Ceramics of the “Poor Potter” of Yorktown,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2004), pp. 31–33, 44; C. Malcolm Watkins and Ivor Noël Hume, The “Poor Potter” of Yorktown, United States National Museum Bulletin 249 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1967), pp. 107–9.

Ivor Noël Hume, Pottery and Porcelain in Colonial Williamsburg’s Archaeological Collections (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1969), pp. 31–33.

Ibid., p. 32.

Roger Lovegrove, Silent Fields: The Long Decline of a Nation’s Wildlife (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), p. 171.

Michael Shrubb, Feasting, Fowling, and Feathers: A History of the Exploitation of Wild Birds, Poyser Monographs 391 (London: T.& A.D. Poyser, 2013), pp. 155–60.

Eliza Smith, The Compleat Housewife; or, Accomplish’d Gentlewoman’s Companion, (1727; reprint, London: Printed for J. and J. Pemberton, 1739), pp. 80, 123–24; Hannah Glasse, The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy (1796; reprint, Hamden, Conn.: Archon Books, 1971), pp. 12, 22, 125; Jane Carson, Colonial Virginia Cookery: Procedures, Equipment, and Ingredients in Colonial Cooking (1968; reprint, Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1985), pp. 1–2.

Noël Hume, Pottery and Porcelain in Colonial Williamsburg’s Archaeological Collections, pp. 28–29.

David R. M. Gaimster, German Stoneware, 1200–1900: Archaeology and Cultural History (London: British Museum Press, 1997), p. 104.

Pennsylvania Gazette, Supplement, November 19, 1767, p. 1.

Skerry and Hood, Salt-Glazed Stoneware in Early America, p. 59.

Sally Kevill-Davies, Sir Hans Sloane’s Plants on Chelsea Porcelain (London: Elmhirst & Suttie, 2015), pp. 8, 44.

Pierre Pomet, A Compleat History of Druggs, 3rd ed. (London: Printed for J. J. Bonwicke, R. Wilkin, S. Birt, T. Ward, and E. Wicksteed, 1737), pp. 124, 152.

Franck Goddio and Evelyne Jay, 18th Century Relics of the Griffin Shipwreck (Manila, Philippines: National Museum of the Philippines, 1988).

C. J. A. Jörg, Porcelain and the Dutch China Trade (The Hague, Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff, 1982), p. 155.

Life on the Philadelphia Waterfront, 1687–1826: A Report on the 1977 Archeological Investigation of the Area F Site, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, prepared for Independence National Historical Park by Juliette Gerhardt (West Chester, Pa.: John Milner Assoc., 2006), pp. 17, 22–23, 53, 66.

Virginia Gazette, issue 7921, July 25, 1766, p. 2.

Boston Post Boy, December 2, 1754; South Carolina Gazette, June 17, 1756; David Barker and Pat Halfpenny, Unearthing Staffordshire: Towards a New Understanding of 18th-Century Ceramics; Exhibition Staged at the International Ceramics Fair and Seminar 1990, [Stoke-on-Trent], Eng.: City of Stoke-on-Trent Museum & Art Gallery, 1990), p. 35.

R. Neil Frank Jr., James Geddy House Archaeological Report: Block 19, Building 11, Lot 161, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series 1446 (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library, 1990), pp. 57–58.

National Museums Scotland Collections Database, s.v. “A.1905.182,” https://www.nms.ac.uk/explore-our-collections/collection-search-results/?item_id=378246 (accessed September 29, 2017).

Boston Gazette, published as Supplement to the Boston-Gazette, &c., no. 689, June 13, 1768, p. 2.

Ivor Noël Hume, Archaeology and Wetherburn’s Tavern, Colonial Williamsburg Archaeological Series 3 (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1969), pp. 39–40.

Roger Massey, “Understanding Creamware,” in T. Townsend Walford and Roger Massey, eds., Creamware and Pearlware Re-Examined (Beckenham, Kent, Eng.: English Ceramic Circle, 2007), p. 20.

Stanley A. South, John Bartlam: Staffordshire in Carolina, South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology Research Manuscript Series 231 (Columbia: University of South Carolina, 2004), p. 25.

Patricia Samford, Dr. Barraud House Trash Pit, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series 1713 (1987; reissued, Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 2001), p. 4.

Lou Powers, Barraud (Dr.) House Historical Report: Block 10, Building 1, Lot 19, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series 1193 (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1990), pp. 6–9.

S. Robert Teitelman, Patricia A. Halfpenny, and Ronald W. Fuchs II, Success to America: Creamware for the American Market (Woodbridge, Suffolk, Eng.: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2010), pp. 40–41, 47, 51.

Sweetmeat is a broad term used to describe candied fruits and nuts. The type displayed in this sweetmeat dish would have been of the dry variety—that is, the candied fruit, fruit peels, sugared seeds, nuts, and flowers were dry and storable, rather than in a sugar syrup—and were intended to be eaten with a fork or spoon as with wet sweetmeats. Louise Conway Belden, The Festive Tradition: Table Decoration and Desserts in America, 1650–1900 (New York: W. W. Norton, 1983), pp. 289, 294.

Robin Emmerson, Table Settings (Haverfordwest, Eng.: Shire Publications, 1991), p. 20.

Belden, Festive Tradition, pp. 52, 130–31; Charles Carter, The Complete Practical Cook; or, A New System of the Whole Art and Mystery of Cookery . . . (London: W. Meadows, C. Rivington, R. Hett, 1730), p. 41.

Mary A. Stephenson, Prentis House Historical Report, Block 17, Building 11A, Lot 51, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series 1365 (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1958), 1–2, 19–20.

Ibid., pp. 32–41.

Jellicoe with Hunter, “English Porcelain in America: Evidence from Williamsburg,” pp. 168–73.

John C. Austin, Chelsea Porcelain at Williamsburg (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1977), pp. 10–11.

Boston Evening Post, November 25, 1754, p. 3; Boston Evening Post, February 9, 1756, p. 3.

“Before 1841 the Williamsburg asylum was called by many different names. The founding act of 1770 spoke of ‘a public hospital’ and called the trustees the ‘court of directors of the public hospital, for persons of insane and disordered minds.’ In the act of March 6, 1841, the trustees were called the ‘Directors of the Eastern Asylum for the maintenance and cure of insane persons.’ Then in March 1861 the legislature specifically named the hospital the Eastern Lunatic Asylum. Its current name, Eastern State Hospital, dates from 1894.” Norman Dain, Disordered Minds: The First Century of Eastern State Hospital in Williamsburg, Va., 1766–1866 (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1971), p. 2n.

Shomer S. Zwelling, Quest for a Cure: The Public Hospital in Williamsburg, 1773–1885 (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1985), p. 1.

Eastern State Hospital, Williamsburg, Annual Reports of the Board of Directors, Richmond, 1870, p. 7, as quoted in Patricia A. Gibbs and Linda H. Rowe, The Public Hospital, 1766–1885: (Eastern State Hospital), Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series 240 (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1974), p. 279.

Richard A. Pizzi, “Apostles of Cleanliness,” Modern Drug Discovery 5, no. 5 (2002):51–55: https://pubs.acs.org/subscribe/archive/mdd/v05/i05/html/05ttl.html#auth (accessed September 29, 2017).

“S Bridgwood & Son,” A-Z of Stoke-on-Trent Potters, http://www.thepotteries.org/allpotters/174.htm (accessed October 3, 2017).

Llewellynn Frederick William Jewitt, The Ceramic Art of Great Britain (London: J. S. Virtue & Co., 1883), p. 552.

Bridgwood & Son, Anchor Pottery, Wharf Street, Longton, Notes on the History of Stoke-on-Trent, http://www.thepotteries.org/potworks_wk/133.htm; The Sun, Baltimore, Maryland, April 16, 1860, p. 3; The Sun, Baltimore, Maryland, April 2, 1868, p. 3.

The Philadelphia Inquirer, March 21, 1876, p. 8.