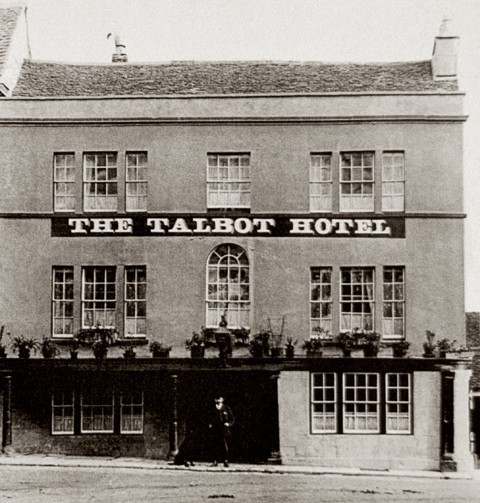

Photograph of the Talbot Hotel, Tetbury, England, ca. 1910. Edwin Webb, the landlord and captain of the Tetbury Fire Brigade is in the foreground. (Courtesy, Peter Williams.)

The Talbot Hotel today. (Photo, Peter Williams.)

A view of the cellar in the Talbot Hotel where archaeological excavations revealed the late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century refuse deposits. (Photo, Peter Williams.)

A selection of archaeological objects exhibited at the Corinium Museum shortly after their recovery. (Courtesy, Peter Williams.)

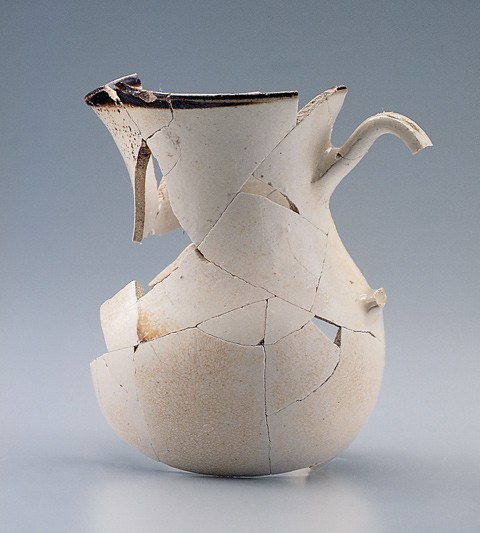

Fragments of a pitcher or chamber pot, England, ca. 1680. Lead-glazed coarse earthenware. ( All artifact photos by Gavin Ashworth unless otherwise noted.) These fragments represent a vessel with a rounded body and an internal mottled olive-brown glaze. The flared lip has traces of pinching, and the unglazed exterior has a wheel-turned double-grooved shoulder-band. The handle upper junction is at the lip, the lower junction with a thumbed attachment. Excavated evidence shows that chamber pots were not always used in the generally suspected manner. Many unearthed examples show signs of having been heated, as if they had been used for cooking purposes.

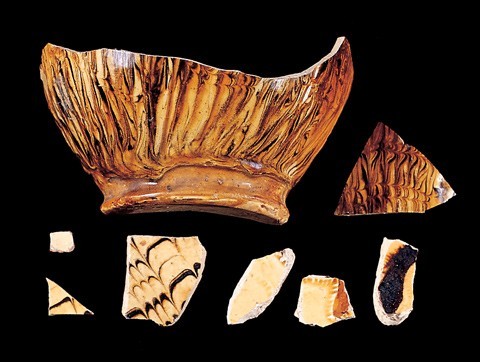

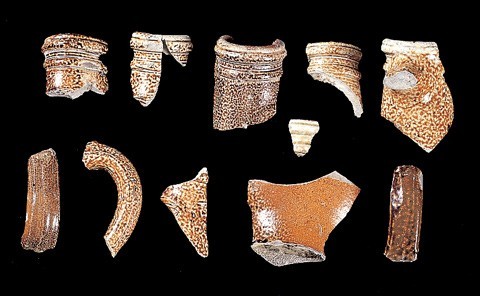

Various fragments, England, ca. 1680. Lead-glazed coarse earthenware. Diameter of this dish is estimated to be 16 3/4". The flange of this large dish has a rouletted, relief border of at least five concentric bands of zigzags reserved within concentric line borders. The upper surface is glazed. Fragments of various other vessels, including part of a lip with a wheel-turned, double-grooved band; part of a handle; and a small base fragment were recovered.

Jugs, Ashton Keynes, North Wiltshire, England, late seventeenth century. Lead-glazed coarse earthenware. H. 7 1/4" and 6". These jugs have a mottled olive-brown glaze on a tall, cylindrical body. The rims have been pinched to create pouring lips. The shoulder-bands are formed by wheel-turned grooves. The flat, circular bases are unglazed except for slight glaze flooding.

Jug fragments, Ashton Keynes, North Wiltshire, England, late seventeenth century. Lead-glazed coarse earthenware. H. 5 3/4". These fragments are from jugs with tall, cylindrical bodies with lip-pinch and shoulder-band formed by wheel-turned grooves. The jug on the left has a green glaze fired with a lustrous metallic appearance. The other has an olive-brown glaze, also fired with a lustrous metallic appearance. The flat, circular base is unglazed except for slight glaze flooding.

Jugs, Ashton Keynes, North Wiltshire, England, late seventeenth century. Lead-glazed coarse earthenware, H. 6 3/4", 5", and 6 1/2". These three jugs, each with a mottled olive-brown glaze, have slightly rounded, tall, cylindrical bodies. The flat, circular bases are unglazed except for slight glaze flooding. The jug on the right has a pinched lip for pouring.

Jugs, Ashton Keynes, North Wiltshire, England, late seventeenth century. Lead-glazed coarse earthenware. H. 5 1/2" and 4 5/8". Examples of two jugs with a mottled green glaze. The flat, circular bases are unglazed except for slight glaze flooding. The jug on the right has a pinched lip for pouring.

Jugs, Ashton Keynes, North Wiltshire, England, late seventeenth century. Lead-glazed coarse earthenware. H. 4 5/8" and 4 1/4". These jugs have a mottled green glaze on a slightly rounded, tall, cylindrical body with pouring lips. The flat, circular bases are unglazed except for slight glaze flooding.

Jugs, Ashton Keynes, North Wiltshire, England, late seventeenth century. Lead-glazed coarse earthenware. H. 5". These three jugs have a mottled, olive-brown glaze, although the glaze on the central jug has fired with a slight luster. The glaze on the far right jug has fired with a metallic lustrous appearance. Its base is also covered with glaze. The flat, circular bases of the other two jugs are unglazed except for slight glaze flooding.

Mug and cup, Staffordshire, 1660–1680. Lead-glazed red earthenware. H. 6" and 3 1/8". The waisted mug on the left has a cylindrical body with two cordons around the middle. The slightly concave, circular base is unglazed except for slight glaze flooding. There are three clay-pad marks, one mark having glaze and clay adhesions. The two elongated loop handles are set at approximately twenty-two degrees to one another, attaching above the waist and midway between the waist and base. The cup illustrated on the right has a flared, cylindrical body with a rib encircling the waist. The base is unglazed except for slight glaze flooding, and there are two clay-pad marks. Base and handle fragments of another mug, or mugs, were also found each similar to the recovered beaker-shaped mug.

Mugs, Staffordshire, 1660–1680. Lead-glazed red earthenware. (The example on the left courtesy, Potteries Museum.) Similar vessels are commonly found in excavations in the Stoke-on-Trent area and on numerous other sites throughout Great Britain.

Mug fragment, Staffordshire, 1700–1720. Manganese-mottled earthenware. (Courtesy, Potteries Museum.) Applied, or sometimes impressed, ale-measure marks are commonly found on “mottled ware” tavern mugs, these bearing the initials of the reigning monarch, namely “WR” for William III, “AR” for Queen Anne, and “GR” for George I.

Cup, Staffordshire, 1700–1720. H. 2 7/8". Manganese-mottled earthenware. This “thistle” shape cup has a compressed spherical body, a flared cylindrical neck, an unglazed short cylindrical foot and an unglazed flat circular base. The earthenware fabric is a pinkish buff. Slipware cups of similar shape were recovered from the same site (see fig. 47). A “mottled ware” triple fuddling cup is recorded, formed by conjoined vessels of the same shape.

Cup, Staffordshire, 1700–1720. H. 2 7/8". Manganese-mottled earthenware. This “thistle” shape cup has a compressed spherical body, a flared cylindrical neck, an unglazed short cylindrical foot and an unglazed flat circular base. The earthenware fabric is a pinkish buff. Slipware cups of similar shape were recovered from the same site (see fig. 47). A “mottled ware” triple fuddling cup is recorded, formed by conjoined vessels of the same shape.

Mugs, Staffordshire, 1700–1720. Manganese-mottled earthenware. H. 3 7/8" and 4". Mugs of similar shape, referred to at the time as a “gorge,” were also produced in German and English stoneware, delftware, and metalware, in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. The mug on the left has a short angular foot that is unglazed, as is the flat circular base (save for slight glaze flooding). The mug is rather heavily potted. The mug on the right also has a spherical body smaller than the body of the foregoing mug. Likewise, its slightly flaring cylindrical neck is taller and narrower. There is a glaze flaw on the extremity of the body where it has touched against another vessel in the kiln. The flared foot is unglazed, as is the flat circular base. The mug has been professionally reconstructed and has two small areas of restoration.

Mug fragments, Staffordshire, 1700–1720. Manganese-mottled earthenware. Several other fragments of these gorge shaped mugs were recovered.

Mugs, Staffordshire, 1700–1720. Manganese-mottled earthenware. H. of right mug: 3 3/4". These two mugs have a half-pint capacity. Each has a cylindrical body with a slightly tapering cylindrical neck and a single shoulder-band formed by ten deep wheel-turned grooves. The partially glazed foot-band is formed by five deep wheel-turned grooves, and the flat circular base is unglazed. The mug on the right has a ribbed “ear” shaped handle with the upper junction at the shoulder-band and the lower junction just above the foot-band. The mug on the left lacks the handle, but the junctions are in the same position. Both mugs are by the same maker. A number of other fragments of similar mugs were also recovered.

Mugs, Staffordshire, 1700–1720. Manganese-mottled earthenware. H. 4" and 5 3/4". The base of the half-pint mug on the left displays numerous parallel straight, string-mark lines. The elongated ribbed loop handles attach at the shoulder-band and just above the foot-band. The lower junction shows a tightly thumbed terminal that has excess clay folded over and up. The body of the pint mug on the right is misshapen, where it was accidentally squashed between the handle junctions before firing. The partially glazed foot-bands have been formed by numerous wheel-turned grooves, and the flat, circular bases are unglazed. Both mugs were probably made by the same potter.

Mugs, Staffordshire, 1700–1720. Manganese-mottled earthenware. H. 5 3/4" and 5 1/2". The mug on the left shows the reverse of the mug illustrated in fig. 20 (right). The mug on the right has a cylindrical body, slightly tapering cylindrical neck, and a single shoulder-band formed by numerous wheel-turned grooves. The unglazed, flared foot-band is also formed by numerous wheel-turned grooves, and the flat, circular base is unglazed. The same potter possibly made this and the two mugs illustrated in fig. 20.

Mug, Staffordshire, 1702– 1714. Manganese-mottled earthenware. H. 3 7/8". This half-pint mug’s cylindrical body has a single shoulder-band formed by numerous wheel-turned grooves. The shoulder-band incorporates an applied clay pad stamped with a crowned “AR” ale-measure mark with relief details. The elongated ribbed loop handle attaches at the lower part of the shoulder-band and just above the narrow, mainly unglazed, foot-band. The unglazed flat, circular base has clay adhesions from another vessel or kiln furniture. The mug has been professionally reconstructed, with only minor restoration.

Detail of the “AR” excise mark on the mug illustrated in fig. 22.

Mugs, Staffordshire, 1700–1720. Manganese-mottled earthenware. The mottled-ware mug on the left was excavated in Town Road, Hanley, Stoke-on-Trent, and is shown for comparison with the mug illustrated in fig. 22.

Mugs, Staffordshire, 1702– 1714. Manganese-mottled earthenware. H. (left) 5 3/4". The half-pint mug on the left shows a narrow, raised band around the rim with an underlying groove about 1/8 inch below. The double shoulder-bands and the unglazed foot-bands were formed by numerous wheel-turned grooves, and the flat, circular bases are unglazed. The handle’s lower junction is stamped with a crowned “AR” ale- measure mark. The same potter made both mugs, although the “AR” marks

are different.

Detail of the “AR” mark on the mug illustrated on the left in fig. 25.

Mug, Staffordshire, 1702–1714. Manganese-mottled earthenware. H. 6 5/8". This quart sized mug is very similar to the smaller pint mugs illustrated in fig. 25 and probably was thrown by the same potter. It is stamped with a crowned “AR” ale-measure mark.

Detail of the “AR” mark on the mug illustrated in fig. 27.

Mugs, Staffordshire, 1700–1720. Manganese-mottled earthenware. H. 5 1/2" and 5 1/4". The two nearly complete pint mugs display a double shoulder-band and an unglazed foot-band formed by numerous wheel-turned grooves. One mug (left) handle’s lower junction is stamped with an indistinct crowned “AR” ale-measure mark terminal with relief details. The same stamped terminal appears on the mug fragment (center). The mug on the left has been professionally reconstructed.

Mugs, Stafffordshire, 1700–1720. Manganese-mottled earthenware. H. (left) 5 1/8". Each of these pint mugs has a cylindrical body and a double shoulder-band formed by numerous wheel-turned grooves.

Mug fragments, Staffordshire, 1700–1720. Manganese-mottled earthenware. H. (left) 5 3/4". Each of these fragments of four mugs has a cylindrical body and an unglazed foot-band formed by numerous wheel-turned grooves.

Mugs, Staffordshire, 1700–1720. Manganese-mottled earthenware. D. (left) 3 5/8". Each of these fragments of four mugs has a cylindrical body and a glazed foot-band formed by numerous wheel-turned grooves.

Mug fragments, Staffordshire, 1700–1720. Manganese-mottled earthenware. D. of base: 3 1/8". The base fragment has an unglazed rounded foot displaying a single wheel-turned groove. The flat, circular base is unglazed.

Mug fragments, Staffordshire, 1700–1720. Manganese-mottled earthenware. The rim fragment on the left is from a thinly potted mug being 1/16" to 3/32" thick and has a mottled olive-brown glaze. The fabric is a high-fired gray earthenware, which does not appear to correspond with any of the other recovered “mottled” wares from the Talbot Hotel. The fragment on the right has a shoulder-band formed by numerous wheel-turned grooves that are additionally hand-incised with linked double-lined saltire crosses.

Jug fragments, Staffordshire, 1700–1720. Manganese-mottled earthenware. D. of base: 3 3/4". One jug (left) has a neck with a lip-pinch and a single groove running about ‹÷¡§ inches below the rim. A section of its elongated loop handle is set at ninety degrees to the lip-pinch. The second jug has a section of an elongated loop handle matching the handle of the first, and the handle’s upper junction is assumed to be in a similar position. The flat, circular base is unglazed.

Cup, Staffordshire, 1700–1720. Manganese-mottled earthenware. H. 5". This large cup has a rounded body with a widely flared cylindrical neck above a wide shoulder-band formed by numerous wheel-turned grooves, and incorporating a prominent cordon near the top and bottom. The short, angular foot is partially glazed, whereas the flat, circular base is unglazed. The fabric is grayish-buff earthenware. The glaze shows scratching and wear, particularly on the interior.

Mugs, Staffordshire, ca. 1720. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 5 1/8" and 6 5/8". These white dipped mugs have the addition of an iron-rich slip around the rim. Both mugs have areas of iron contamination, and the quart mug (right) has small areas of the white pipe-clay slip pulling away just below the rim interior.

Mug fragments, Staffordshire, ca. 1720. Salt-glazed stoneware.

Jug, Staffordshire, 1700– 1720. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 5 1/2". The spherical body has a flared neck, pinched lip, and band of iron-rich slip around the rim. A similar excavated jug is in the Potteries Museum and Art Gallery, Stoke-on-Trent, and at Rummey’s Tavern in London Town, Maryland.

Fragments, Staffordshire, ca. 1725. Salt-glazed stoneware. These small fragments represent one or more vessels including a base fragment and a rim fragment, with wheel-turned grooved banding.

Mugs, Staffordshire, 1700– 1720. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 5". The pint mug on the left has a foot-band formed by four wheel-turned cordons above a rounded foot-rim. The lower part of the pint has an off-white pipe-clay slip dip on the exterior, over a pale gray fabric, and there are areas of slip on the slightly concave base where the slip has run from the foot-rim. The upper part of the pint mug has a freckled iron-rich dip that also continues down from the rim on the interior about 3/4 inch (1.9 cm.) and on the remaining sections of the grooved handle. The half-pint mug on the right has a white-slip dip on the interior, on the lower part of the exterior and over the base. Both mugs are probably by the same maker. These mugs were included in Jonathan Horne’s 1985 Exhibition of English Brown Stoneware, in Kensington Church Street, London. Similar mugs were recovered from Swan Bank, Burslem.

Mugs, England, ca. 1710. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 7" and 6 1/2". The quart mug on the left was probably made in Nottingham and has an impressed circular ale-measure mark below the wide band, with the uncrowned conjoined initials “AR” in relief. The mug on the right was possibly made in Bristol. The pale gray fabric has a freckled iron-rich dip overall. These mugs were included in Jonathan Horne’s 1985 Exhibition of English Brown Stoneware, in Kensington Church Street, London.

Detail of the impressed “AR” on the mug illustrated on the left in fig. 42.

Mug and mug fragments. Salt-glazed stoneware. Left: Possibly Bristol, H. 3 3/4". The top three-quarters of the exterior of the mug, including the handle, has a freckled iron-rich dip over the pale gray stoneware fabric. The interior is partially wiped in dark brown. This mug was included in Jonathan Horne’s 1985 Exhibition of English Brown Stoneware, in Kensington Church Street, London. Right: Two large fragments of a Staffordshire mug, one fragment with a foot-band formed by a central cordon between wheel-turned grooves, above a rounded foot-rim. A white-slip dip over the pale gray fabric and the overall freckled iron-rich dip on the exterior is divided into two distinct tones by the white-slip base dip.

Mug fragments, Staffordshire, ca. 1710. Stoneware with a solid lustrous iron-rich dip on the exterior, matt mid-brown overall on the interior. The banded decoration is formed by wheel-turned grooves, and the incised stylized foliage has a zigzag infill. The base fragment has a wheel-turned, slightly waisted raised foot-band, a rounded foot-rim, and a partially recessed circular base. A similarly decorated mug was excavated near St. John’s Church, Burslem, in 1964. Another was recovered from the Wellfleet Tavern, at Wellfleet, Great Island, Massachusetts.

Mug fragment, probably Staffordshire, ca. 1710. This fragment exhibits a mid-brown, iron-rich dip on the exterior and interior. The ground decoration of numerous parallel wheel-turned grooves is hand-incised with straight lines to form an elongated diamond diaper pattern. Other fragments of this type of ware were recovered including one with an impressed partial ale-measure mark that includes the top of a raised unidentifiable royal initial.

Cups, Staffordshire, 1700. Slipware. H. 2 7/8" and 2 3/4". The cup on the left has a reddish-pink earthenware fabric displaying a white-slip coating. Its exterior is finely combed. The cup on the right has a pale buff earthenware fabric displaying an iron-rich slip coating on the exterior and a white slip coating on the interior. The exterior is trailed in white slip with five stylized vertical leaves, each central vein combed to produce numerous fronds. The slightly concave base is unglazed save for slight glaze flooding. Both cups have been professionally reconstructed and have areas of restoration. A Staffordshire mottled ware cup of similar shape was recovered from the Talbot Hotel site (see fig. 16). Similar cups were recovered from a workman’s trench at the present-day Sadler’s factory in Burslem.

Cups, Staffordshire, 1700. Slipware. H. 2 7/8" and 2 3/4". The cup on the left has a reddish-pink earthenware fabric displaying a white-slip coating. Its exterior is finely combed. The cup on the right has a pale buff earthenware fabric displaying an iron-rich slip coating on the exterior and a white slip coating on the interior. The exterior is trailed in white slip with five stylized vertical leaves, each central vein combed to produce numerous fronds. The slightly concave base is unglazed save for slight glaze flooding. Both cups have been professionally reconstructed and have areas of restoration. A Staffordshire mottled ware cup of similar shape was recovered from the Talbot Hotel site (see fig. 16). Similar cups were recovered from a workman’s trench at the present-day Sadler’s factory in Burslem.

Slipware fragments, Staffordshire, 1700–1720. D. of base fragment: 3 1/4". The largest fragment represents a cup, or honey pot, with a spherical body and a rounded, angular foot-rim. The pale buff earthenware fabric displays an exterior white-slip coating vertically striped in dark-brown slip with traces of horizontal combing. The small fragments include two dish fragments (bottom left) with combed decoration; three fragments (bottom right) from a press-molded dish, or dishes, with traces of a mid-brown slip infill; and a tiny vessel fragment (left).

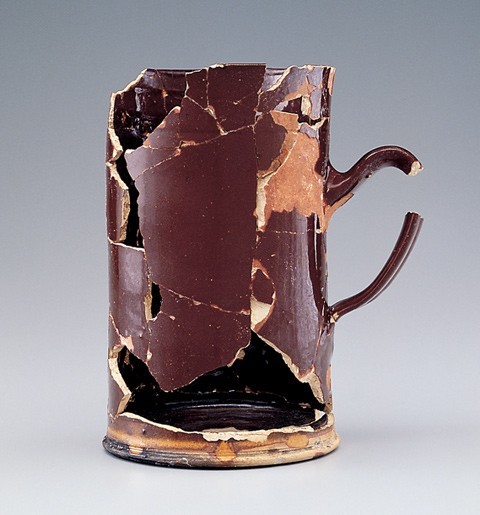

Mug, probably Staffordshire, England, ca. 1720. Slip-coated earthenware. H. 6 3/4". This quart capacity mug has a tall, cylindrical body with a single wheel-turned groove below the slightly flared rim. The wheel-turned, double-grooved foot-band and the rounded, angular foot-rim are unglazed except for slight glaze flooding. The lead glaze has transformed the slip-coat to a solid dark, reddish-brown color, and the glaze appears translucent yellow where it has flooded over the slip-free foot-band.

Mug, probably Staffordshire, England, ca. 1720. Slip-coated earthenware. H. 6 3/4". This quart capacity mug has a tall, cylindrical body with a single wheel-turned groove below the slightly flared rim. The wheel-turned, double-grooved foot-band and the rounded, angular foot-rim are unglazed except for slight glaze flooding. The lead glaze has transformed the slip-coat to a solid dark, reddish-brown color, and the glaze appears translucent yellow where it has flooded over the slip-free foot-band.

Plate and bowl fragments, England, 1700–1720. Tin-glazed earthenware. The large dish fragment is attributed to Brislington having a plain, shallow, rounded form and a matt, duck-egg blue, tin-glazed ground over a pale buff fabric. The indistinguishable decoration is washed in tones of blue and is delineated in manganese. The majority of the other fragments are attributed to Bristol and painted in blue and, most likely, belong to plates or dishes. The exceptions are a blue-painted fragment from a possible bowl rim; one fragment from a possible drinking vessel, displaying powdered manganese-purple on both interior and exterior; and one fragment with polychrome decoration painted in blue, sponged in green, and delineated in black.

Fragments of two bottles, Germany, ca. 1680. Salt-glazed stoneware. Each of these fragments of Bellarmine bottles have an ovoid body and a freckled, iron-rich exterior dip over a pale gray stoneware fabric. The bottles have a slightly varying oval, relief-molded, rosette medallion applied to the front.

Fragments of Bellarmine bottles, Germany, ca. 1680. Salt-glazed stoneware. One fragment’s applied relief-molded, oval medallion depicts a heart encircling a cross beneath a crown. Another fragment (not pictured) displays part of an applied relief-molded medallion, including the initial “H.” Similar initialed medallions were found on bottles made at John Dwight’s factory in Fulham, London. However, the fragment noted does not correspond with any known Dwight examples.

Detail of the heart medallion illustrated in fig. 52.

Bottle fragments, Germany, ca. 1680. Salt-glazed stoneware. These various neck, handle, and base fragments may belong to the bottles previously discussed.

Mug and mug fragments, Westerwald, Germany, 1690–1710. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 3 3/8". The nearly complete example on the left has a loop handle that has an indentation at the top for a metal cover. The stoneware fabric is pale gray, and the base is flat. The mug fragments on the right are incised with foliate scrollwork and display a cobalt-blue background wash.

Overall view of reconstructed vessels from the Talbot Hotel assemblage.

For centuries, the Talbot Hotel was one of the foremost taverns in the picturesque and historic Cotswold town of Tetbury, Gloucestershire.[1] Situated at No. 14 Market Place, the hotel is primarily a seventeenth-century building that was refronted in the early nineteenth century (fig. 1). A popular gathering place for travelers and locals alike, the Talbot enjoyed a reputation for the best of food, services, atmosphere, and all-night parties. In 1971, it even appeared in Dulcima, a Sir John Mills movie drama. Since 1594, when Richard Biddle bought and paid an extra two-pence rent for “A Taverne Head with a shoppe,” there has been a tavern on the Talbot Hotel site; that is, until April 5, 1986.[2] On this date, after nearly 400 years of welcoming guests, the Talbot closed its doors to the public. Today, the celebrated landmark is a private residential property (fig. 2).

Set in the midst of quiet, green countryside, Tetbury, nevertheless, was the center of much marching and fighting during the English Civil War, a conflict between Royalists and Parliamentarians, which began in 1641. The cloth manufacturing areas of the Stroudwater were strongly in favor of the parliamentary forces, and the towns of Malmesbury, Tetbury, Beverston, and Wotton-under-Edge were fortified posts for the crown on the edge of these disaffected districts.[3] In 1643, a royalist garrison was established in Tetbury. In fact, on his way from Bristol to Gloucester, King Charles I dined there—reputedly at the Talbot Hotel itself. Favorably impressed, perhaps, the king issued an order to his officers to “spare” the town. Other monarchs recorded as passing though Tetbury include Charles II (in 1664), James II (in 1687), and Queen Anne (in 1702).

The first mention of the Talbot Hotel by name does not occur until 1656, when the following entry appeared among the presentments of the borough court roll:

We order that the incroachment at the Inne called the

Talbott beinge a penthouse that the Landlord and

Tenent or one or either of them nor there successors

shall molest or hinder any person or persons in

standinge & selling of Cheese or any other commodity on the Market day there upon the fforfeiture for everie day ___________________ v s. [ 5 shillings ]

Local directories record the more recent Talbot landlords, but early information is difficult to find. For example, the Talbot is listed as one of the oldest inns in Tetbury, but no information is given about earlier owners or tenants.[4] As well, most of the alehouse recognizances for Gloucestershire were destroyed in the mid-nineteenth century. Unfortunately, none of the surviving records in the Gloucestershire Record Office include information on the Longtree Hundred, the parish in which Tetbury lay. Archaeology would tell us much more—at least about tavern life.

An Account of the Investigations at the Talbot Hotel

In May 1985 alterations to properties adjacent to the Talbot led the hotel owners, Mr. and Mrs. Roy Speakes, to explore their cellars. According to the hotel’s deeds, the Talbot contained five wells. Three were uncovered, including one lying under the dining room floor and another under a flagstone in the gent’s toilet (fig. 3).

The small, rough stone-built room, opening off the main cellar, was investigated by archaeologists Nigel Spry and Harold Wingham, and a short report on the exploration was published.[5] The stone room was located about five yards back from the hotel’s front wall, and had for many years been used for the disposal of rubbish. Clearance revealed a collapsed floor of reused oolite limestone flags, which had sealed either a large well, holding tank, or soak-away pit about two yards square and partially filled with water. Limited exploration yielded a great deal of dense, soft organic material, reminiscent of that encountered in medieval cesspits. Farther below, a more recent, final fill of large stone fragments and yellow-brown, clayey loam was uncovered. The final fill accumulation was extracted and a layer of the soft deposit was then removed to a depth of about eight inches. It was found to contain fragments of pottery, clay pipes, and glass wine bottles, including a complete onion-shaped bottle, identified as Flemish and pre-1710. Added to the mix were animal—mainly lamb—bones, corks, nuts, straw sweepings, leather, and preserved timber wainscoting. Oyster shells were also recovered. Since there are no records of oyster beds in the nearby River Severn, it is possible that the oysters were transported in seawater from the Kent coast.

Further explorations of the pit took place during the summer of 1985, down to a depth of about two yards where hard stones were encountered. Among the recovered items were two small pieces of jewelry engraved with a Tudor rose. These small items looked like cuff links, but were probably used as dress fasteners. Also recovered was a shoe heel and silver buckle, countless clay pipes, and more wine-bottle fragments, one with a seal initialed “T H.”

The recovered pottery and clay pipe fragments were received by local dealer and conservator, Peter Wain, who had assisted personally with the investigations. The pottery was considered to be from the late seventeenth century to the early eighteenth century. Since the ceramic fragments were found at the top of the pit, Wain deduced that it was sealed some time between 1720 and 1725. It was also concluded that if the pit had originally been a well, it probably dried up before this date, and was then used as a receptacle for rubbish from the hotel’s public rooms—a common practice of the period.

Three of the recovered clay pipes bearing maker’s marks were identified as having been made in Bristol. One was marked “R TIP” for Robert Tippett who was active from circa 1680. Another was marked “ANDRE——,” possibly for Andrews, a known pipe maker from 1739, although the date is inconsistent with other pipes found in the same layer. The large collection of clay pipes, including many by previously unrecorded makers, was donated to the Gloucester City Museum.

Other finds from the Talbot Hotel were passed to the Corinium Museum, Cirencester, where in December 1985 a collection of the best discoveries was put on display as “A Picture of Pub Life” (fig. 4). The glassware, including a previously unrecorded seventeenth-century Venetian fluted wine glass, was later donated to the Corning Museum of Glass in Corning, New York.

A Review of the Pottery Finds from the Talbot Hotel

Peter Wain initially reconstructed many of the salvaged pottery finds from the Talbot Hotel pit. The entire ceramic assemblage was subsequently reanalyzed with additional mending and refitting of fragments. The assemblage is presently in a private collection where it is being maintained intact. What follows is an overview and discussion of the ceramics organized by ware type from this virtually unparalleled assemblage of early English tavern wares.

Lead-Glazed Earthenware

COARSE EARTHENWARE

Only a handful of late-sixteenth- and seventeenth-century lead-glazed coarse earthenware fragments were recovered (figs. 5, 6). It is assumed that these remnants are probably all of local manufacture.

ASHTON KEYNES EARTHENWARE

A distinctive recovered group of lead-glazed red earthenware jugs was identified as having been made at the village of Ashton Keynes, North Wiltshire, situated some ten miles to the west of Tetbury (figs. 7-12). These late seventeenth-century jugs are almost medieval in character and are representative of a traditional localized pottery industry that had been prevalent in rural Britain for centuries.

Ashton Keynes was renowned for its leather glove-making industry, which probably developed because of the parallel growth of the woolen industry and tanning, which offered a good supply of raw material. Gloving flourished in the village in the nineteenth century, but the industry dates back in Wiltshire as early as the thirteenth century.

Evidence of early potters at work in Ashton Keynes has been found at a medieval settlement near Flood Hatch Copse (a half-mile stretch of gravelly water) and at many other sites within the village. The village is built mainly on Thames gravel, but to the north the land rises over clay. The interface seems to be behind the houses built in Back Street, and several closes in that area are called “Clay Piece” or the like. A brickyard existed at North End in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Documentary evidence about the villagers’ occupations does not commence until the seventeenth century, but it appears that there was never enough room in the village for more than one pottery at a time. The earliest record of a potter at Ashton Keynes is the will of Barbar Vincent, potter, proved November 13, 1661. Barbar was married in the village on January 23, 1629, and was buried there on September 25, 1661. Although the exact location of his premises is not known, it is thought to have been in the Kent End area at the eastern end of Back Street. The next record is the inventory of Richard Vincent taken in 1663 by his son Richard, potter, and including a quantity of “unburned potts” and “one potters oven to burn potts in.” Richard Vincent’s house also contained a shop described as an “inner room,” presumably therefore not facing the street. Richard Vincent’s relationship to Barbar is unknown, but they were possibly brothers. There are no further records of the Vincents as potters, though they remained in the village until at least 1700.

It is possible that the Vincents’ business was passed, or sold to the Taylor alias Corver family. The inventory of Anne Taylor als Corver, widow, dated May 15, 1684, includes “clay, potts, earthenware, and raw potts unburned,” clearly implying that she was running a pottery business. A few years later the parish registers reported the occupations of the villagers between 1700 and 1707, and listed the two following entries:

1701 Anne, the wife of Thomas Taylor alias Corver (potter), buried June 19th.

1705 John, the son of Henry Corver als Taylor (potter), baptized March 28th.

Later in the eighteenth century a series of records confirm that the family was still potting:

1750 Thomas Taylor is assessed for Land Tax at 15s 3 3/4d.

1761 Thos. Taylor, potter, is recorded in the Freehold Books. (He also appears in earlier books back to 1743, though occupations are not recorded in earlier years.)

1763 Deeds of 12/13 August include Thos. Taylor als Corver, potter.

1773 A deed of August 9 for the sale of land involves Thomas Taylor als Corver of Ashton Keynes, potter, as well as his son Robert, also a potter.

No further records of the Taylor alias Corver family as potters are known, but they did continue in the village for some decades afterwards and were clearly moderately well off.

It seems likely that the maker(s) of the group of Ashton Keynes earthenware jugs recovered from the Talbot Hotel would have been either Thomas or Henry Taylor alias Corver, or both. Although the surrounding road system was not particularly good in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, Ashton Keynes was only a few miles from the great Roman roads through Cirencester; thus transportation to Tetbury would not have proved too difficult at that time.

Other than two clay pipe manufacturers, the only other mention of a potter in the village in the eighteenth century seems to be a marriage settlement of October 18, 1775, concerning the Carter family, which mentions a messuage occupied by John Millard, potter. The Carters owned property at the top of Clay Hill at North End, near the brickyard, and Millard may have worked there.

Interestingly, amongst the entries in the 1851 census, which listed everyone in the village, together with their occupation, are:

Agricultural Labourers 122

Boot & Shoe Makers 14

Farmers 19

Glovers 55

Masons 14

Paupers 13

Potters 3

The principal of the three noted potters was Charles Gardner, who carried on a pottery at Harberts Cottage. However, while still described as a potter in 1851, he was by then blind and presumably retired. The two other potters were John Weaver, a potter journeyman who may have taken over Harberts Cottage from Charles Gardner, and Edward Turner, living in the family of Thomas Turner, brick manufacturers at Coxes Lane brickyard.[6] Sadly, any reference to the production of pottery at Ashton Keynes had disappeared by 1867, and the most notable local modern industries are those based on gravel extraction for concrete-based products.

BLACKWARE

A mid-seventeenth-century mug and cup made from red, iron-bearing, earthenware with a dark black iron and lead glaze were recovered, together with two small fragments of another mug, or mugs, found in the excavation (fig. 13). All appear to have been made in North Staffordshire and seem to have been influenced by earlier “Cistercian” wares.[7] Several mugs similar to the Talbot Hotel example were excavated from the Marquis of Granby Hotel site in Burslem, Stoke-on-Trent, in 1956.[8] The site was previously occupied by a house and oven, which could have been part of “Ralph Allon’s Red-Ware Work.” Similar blackware vessels are commonly found in excavations in the Stoke-on-Trent area (fig. 14) and on numerous other sites throughout Great Britain.[9]

MOTTLED WARE

A comprehensive group of thrown and turned lead-glazed, pale-buff earthenware vessels with mottled brown coloring was recovered from the Talbot Hotel (figs. 16-36). This assemblage—mainly cylindrical mugs—appears to be solely of North Staffordshire manufacture and dates from circa 1700–1720.

This type of pottery was referred to as “manganese-glazed ware” in excavation reports of the 1970s and 1980s. The glaze’s streaked appearance suggests that, possibly, it is the “Motley-colour” referred to by Robert Plot, “which is procured by blending the Lead with Manganese, by the Workmen call’d Magnus.”[10] However, it is conjectured that Plot, or the workmen he interviewed, could have been confusing manganese with magnas, an iron-ore.[11]

There was widespread production of mottled ware throughout Stoke-on-Trent, as evidenced by the excavations of kiln sites at Albion Square and Old Hall Street, Hanley. Significant groups of mottled ware were also recovered from Swan Bank, Burslem, and Town Road, Hanley.[12] The majority of the excavated production waste appears to date from the period 1700–1720.

Domestic groups of mottled ware were common during the eighteenth century. An ample assemblage of this early-eighteenth–century ceramic type was found at Temple Balsall, Warwickshire, at South Castle Street, Liverpool, and at Mount Street, Stafford. Although there is no conclusive evidence for Staffordshire production of mottled ware into the second half of the eighteenth century, a Stafford pit group dating to circa 1770 contained several late examples of mostly kitchen and food preparation vessels, as well as chamber pots.[13]

Mottled ware appears to have been made at other major potting centers during the eighteenth century, including Buckley, Prescot, Sheffield Manor, Bristol, Ironbridge, and Derby. Many examples are known to have forms that differ considerably from those found in Stoke-on-Trent, and widespread production is therefore indicated.

Applied, or sometimes impressed, ale-measure marks are commonly found on mottled-ware tavern mugs bearing the initials of English monarchs, “WR” for William III (see fig. 15), “AR” for Queen Anne, and “GR” for George I.[14] Several of the mugs recovered from the Talbot Hotel bear “AR” ale-measure marks. Interestingly, although utilitarian mottled ware vessels were obviously in common use at the time, examples are rarely found today, other than in an excavated context.

English Salt-Glazed Stoneware

WHITE DIPPED STONEWARE

The majority of the recovered white, salt-glazed stoneware has an off-white, pipe-clay slip dip over a pale gray stoneware fabric (figs. 37-39). The group appears to be of North Staffordshire manufacture and dates from circa 1720.

Similar white-dipped stoneware vessels have been excavated in Stoke-on-Trent, including one mug found at Fenton Vivian when the Thomas Whieldon factory site was investigated. A Staffordshire white-dipped stoneware mug was also found at Wetherburn’s Tavern in Williamsburg, Virginia, in a mid-eighteenth-century context.[15]

WHITE STONEWARE

Only a few small fragments of high-fired, salt-glazed white stoneware were recovered (fig. 40). These appear to be of North Staffordshire manufacture and date from circa 1725, or possibly later. These few fragments are the latest ceramic types in this assemblage suggesting the terminus date for the deposit.

BROWN STONEWARE

The salt-glazed brown stoneware mugs and fragments recovered from the Talbot Hotel are from various centers of manufacture, but all date from the early eighteenth century (figs. 41-46).

Slipware

The small amount of late seventeenth-century slip-decorated earthenware that was recovered from the Talbot Hotel is all apparently of Staffordshire manufacture. Although this group is relatively small, some exceptional examples were found (figs. 47, 48).

Slip-Coated Ware

Only one example of uncommon Staffordshire slip-coated earthenware (also called “chocolate-dipped ware”) was recovered, dating from circa 1720 (fig. 49). This type of buff-bodied, once-fired earthenware is characterized by a brown or dark red slip coat beneath a lead glaze. Dated examples of this pottery show that its production was in favor in the 1720s–1740s, although examples have been found in domestic groups of circa 1770. Flatwares tend to be coated and glazed on the inside only, whereas hollow wares are coated and glazed inside and out, with both frequently finishing a little short of the base.

Slip-coated ware is a relatively minor type of pottery, but small quantities have been found on most archaeological sites in Stoke-on-Trent. It is also known to have been made at Buckley, and will probably be found on other sites that produced mottled wares or Staffordshire-type slipwares in the eighteenth century.

English Tin-Glazed Earthenware

Only a handful of late-seventeenth- and early-eighteenth-century English tin-glazed earthenware fragments was recovered (fig. 50). Such a meager find is in direct contrast to the results of tavern site excavations in the United States, where fragments of British delftware, particularly punch bowls, are found in relative abundance. Recent studies of taverns in Williamsburg, Virginia, and London Town, Maryland, have documented the high frequency of delft punch bowls to the relative low occurrence of stoneware mugs.[16] This discrepancy might suggest a profitable avenue for future transatlantic research concerning the nature and functions of early-eighteenth-century British taverns.

German Salt-Glazed Stoneware

The only continental pottery finds from the Talbot Hotel site were fragments of mid- to late-seventeenth-century Rhenish salt-glazed stoneware, Bellarmine bottles, and two late-seventeenth-century Westerwald mugs (figs. 51-55).

Observations and Conclusions

The tradition of drinking unhopped ale and hopped beer from pottery mugs flourished from the Middle Ages until at least the beginning of the twentieth century. However, while the “pub culture” achieved a widespread following in England, the development of a ceramic industry was somewhat backward. Robust salt-glazed stoneware drinking vessels were therefore imported continuously from the Rhineland from the fourteenth century until the end of the seventeenth century, when native potters achieved self-sufficiency by producing their own durable drinking vessels, adapting the forms to suit the English taste (fig. 56).

The increasing popularity and complete lack of any regulation of tavern mugs led to William III’s Act of 1700 for “Ascertaining the Measures for retailing Ale and Beer,” whereby vessels were to be checked during manufacture and stamped with “WR” below a crown. In reality it was not feasible to check the capacity of an unfired clay pot, which would shrink considerably during firing, and it seems that the potters were entrusted with marking their own products. The terms of the Act of 1700 were so poorly understood that the royal cipher was substituted by “AR” by some potters during the reign of Queen Anne, while in Bristol “GR” was consistently used after the accession of George I and throughout the eighteenth century. From a ceramic historian’s point of view, the Act of 1700 is invaluable, as the presence of an ale-measure mark provides a date before which a vessel could not have been made.

Relatively few English inns and taverns have been archaeologically investigated.[17] However, such excavated assemblages have been summarized in an American model proposed by Kathleen Bragdon in a comparative study from two colonial sites in Massachusetts: the Joseph Howland farmstead, in Kingston, and the Wellfleet Tavern, at Wellfleet, Great Island.[18] The analysis suggests that tavern assemblages typically include:

1. A large number of vessels, both ceramic and glass.

2. A large proportion of drinking vessels in relation to the whole ceramic assemblage.

3. A large proportion of ceramic fabrics most commonly used for drinking vessels.

4. A large number of wine glasses.

5. A quantity of specialized glassware.

6. And a large number of clay pipes.

The recovered assemblage from the Talbot Hotel conforms to this analysis, and the exploration allows a fascinating insight into the life of the building in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. It can be deduced that the hotel guests were fed meat from the bone and oysters in their shells, washed down with good English ale and beer in Staffordshire pottery mugs. It appears that these superior utilitarian vessels quickly superseded the somewhat old-fashioned local pottery wares as soon as they had become widely distributed, and therefore readily available, throughout Britain.

After dining, the Talbot Hotel’s host would probably have supplied the guests with a “smoke” of tobacco in pre-packed locally made clay pipes– pipes which at that time were disposable as the tobacco was much more expensive than the pipes themselves. The refreshments would then perhaps have concluded with “toddy” of wine or spirit before the guests departed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am grateful for the significant contributions from the following people: Garry Atkins, Kensington Church Street, London, for encouraging me to undertake this project, and for his enthusiasm throughout; David Barker, Senior Museums Officer, The Potteries Museum & Art Gallery Stoke-on-Trent; David Britton and Ashton Keynes of Wiltshire; Geoff Haines, The History of Tetbury Society, Gloucestershire; Mrs. J.V. Thorpe, Archivist & Record Agent, Gloucestershire Record Office; and Peter Wain and the fellow enthusiasts involved in the explorations of the Talbot Hotel cellars.

The hills of the Cotswolds are where the long-wooled “Cotswold” breed of sheep originated.

A Tudor doorway was revealed when a modern fireplace in the front room of the Talbot Hotel was knocked out in the 1980s.

Stroudwater refers to the area in and around the town of Stroud, Gloucestershire, where there was a booming woolen industry.

Victoria History of Gloucestershire, edited by Nicholas Herbert et al., vol. 11 (London: Oxford University Press for the University of London Institute of Historical Research, 1976).

Nigel Spry and Harold Wingham, “Talbot Hotel, Tetbury,” Glevensis, The Gloucester and District Archaeological Research Group Review, no. 19 (1985): 28–30.

The full list of occupations is transcribed by Madge Paterson and Ernie Ward in Ashton Keynes, A Village With No History (Chirkbank, Shropshire: Keith Cowley, 1986), p. 120.

“Cistercian” ware is the term given to blackware vessels made in the late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries and commonly found near the sites of Cistercian monasteries in England.

Arnold R. Mountford, “The Marquis of Granby Hotel Site, Burslem, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffs.,” City of Stoke-on-Trent Museum Archaeological Society Report No. 7 (Stoke-on-Trent: City Museum and Art Gallery, 1975).

A similar, three-handled cup is in the Troy D. Chappell Collection. Troy D. Chapell, “An Adventure with Early English Pottery,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2001), p. 188, fig. 1, and fragments of similar cups have been found on early-seventeenth-century settlements in the Chesapeake region. A similar mug, commonly known as a “tyg,” is illustrated by Ivor Noël Hume in If These Pots Could Talk: Collecting 2,000 Years of British Household Pottery (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2001), p. 129, fig. VI.16a.

Robert Plot, The Natural History of the Countie of Stafford-shire (Oxford, 1686), p. 123.

Arnold. R. Mountford and F. Celoria, “Some Examples of Sources in the History of 17th Century Ceramics,” Journal of Ceramic History, no. 1 (Stafford, Eng.: George Street Press, 1968), p. 18.

F. S .C. Celoria and J. H. Kelly, “A Post-medieval Pottery Site with a Kiln Base Found off Albion Square, Hanley, Stoke-on-Trent,” City of Stoke-on-Trent Museum Archaeological Society Report No. 4 (Stoke-on-Trent: City Museum & Art Gallery, 1973). J. H. Kelly and S. J. Greaves, “The Excavation of a Kiln Base in Old Hall Street, Hanley, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffs,” City of Stoke-on-Trent Museum Archaeological Society Report No. 6 (Stoke-on-Trent: City Museum and Art Gallery, 1974). J. H. Kelly, “A Rescue Excavation on the Site of Swan Bank Methodist Church, Burslem, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, England,” City of Stoke-on-Trent Museum Archaeological Society Report No. 5 (Stoke-on-Trent: City Museum and Art Gallery, 1973).

Eileen Gooder, “The Finds from the Cellar of the Old Hall, Temple Balsall, Warwickshire,” Post-Medieval Archaeology, vol. 18 (1986): 173–81. David Barker and Mary Holland, “Two Post-medieval Pit Groups from Stafford,” Staffordshire Archaeological Studies, vol. 3 (1986): 110. Mary J. Kershaw, “An 18th Century Pit Group from Stafford,” Staffordshire Archaeological Studies, vol. 4 (1987): 80.

A “WR” marked mug is illustrated by Gordon Elliott in John and David Elers and their Contemporaries (London: Jonathan Horne Publications, 1998), pl. 7A.

Arnold R. Mountford, The Illustrated Guide to Staffordshire Salt-glazed Stoneware (London: Barrie and Jenkins, 1971), pl. 55, right. Ivor Noël Hume, If These Pots Could Talk, p. 199, fig. IX.24.

Robert R. Hunter, Jr., “English Delft From Williamsburg’s Archaeological Contexts” in John C. Austin, British Delft in the Colonial Williamsburg Collection (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation and Jonathan Horne, 1994). Al Luckenbach, “Ceramics from the Edward Rummey/Stephen West Tavern, London Town, Maryland, Circa 1725,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2002).

See Kevin Fryer and Andrea Shelley, “Excavation of a Pit at 16 Tunsgate, Guildford, Surrey, 1991,” Post-Medieval Archaeology, vol. 31 (1997): 139–230, and Jacqueline Pearce, “A Late 18th-Century Inn Clearance Assemblage from Uxbridge, Middlesex,” Post-Medieval Archaeology, vol. 34 (2000): 144–86.

Kathleen Bragdon, “Occupational Differences Revealed in Artifact Assemblages,” in Documentary Archaeology in the New World, edited by Mary C. Beandry (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), pp. 83–91.