Couch, Boston, Massachusetts, ca. 1698. Maple and oak; original upholstery foundation and Turkey-work covers and trim. H. 46 5/8", W. 59 5/8", D. 27". (© 2017 Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, MA; photo, Bob Packert.)

Stool, probably New Haven, Connecticut, 1640–1660. Oak. H. 14 1/2", W. 13 1/2", D. 14 1/2". (Courtesy, Wadsworth Atheneum, Wallace Nutting Collection, 1926.467; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Andrew Passeri and Robert F. Trent fabricated the nonintrusive upholstery in 1984. Fragments of original webbing remain on the seat rails. It is possible that this frame originally had a down cushion sewn atop the webbing and sackcloth, like many of the objects with original upholstery at the historic house Knole in Kent.

Armchair, London, England, 1641–1655. Beech. H. 41 5/8", W. 25 13/16", D. at seat 18". (Pilgrim Society, bequest of Anna Nightingdale Warren Hobbs, 1957, PHM# 1175; photo, Andrew Davis.) Peter Arkell restored the lower part of the feet, seat rails, stay rail, and the forward portions of the grips in 1984, using the armchair illustrated in figure 4 as a guide. Manfred Woerner installed the current upholstery in 1986.

Armchair, London, England, 1640–1660. Beech; fragmentary silk velvet upholstery and painted decoration over gesso. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, R. W. Symonds Papers, collection 57, series 2, box 1, 59.436.) This image was taken before the armchair entered the collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London in 1953. The gesso under the painted decoration is visible in many areas of paint loss.

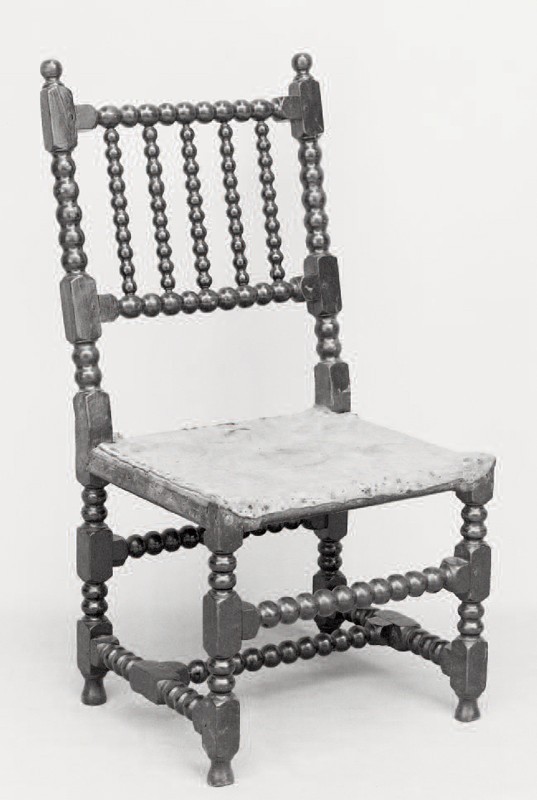

Side chair, possibly Boston, Massachusetts, 1660–1680. Maple and oak. H. 37 1/8", W. 18", D 15 3/16". (Yale University Art Gallery, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Frank J. Coyle, LL.B. 1943, 1991.178.1.) The present leather upholstery is modern.

Side chair, probably Ipswich or Newbury, Massachusetts, 1670–1700. Maple and oak. H. 36", W. 18", D. 15 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Jim Wildeman.) Keith Lackman and Robert F. Trent fabricated the nonintrusive upholstery foundation and covers in 2005.

Side chair, New England or New York, 1670–1690. Maple. H. 37 5/8", W. 18 5/8", D. 19 3/4". (Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Mrs. Russell Sage, 1909, 10.125.203.) The left seat rail is a replacement, and the seat board is missing. The frame was upholstered later, perhaps in the eighteenth century. This example and two others from the Delaware Valley (Winterthur Museum; Philadelphia Museum of Art) are the only known American examples of this seating design.

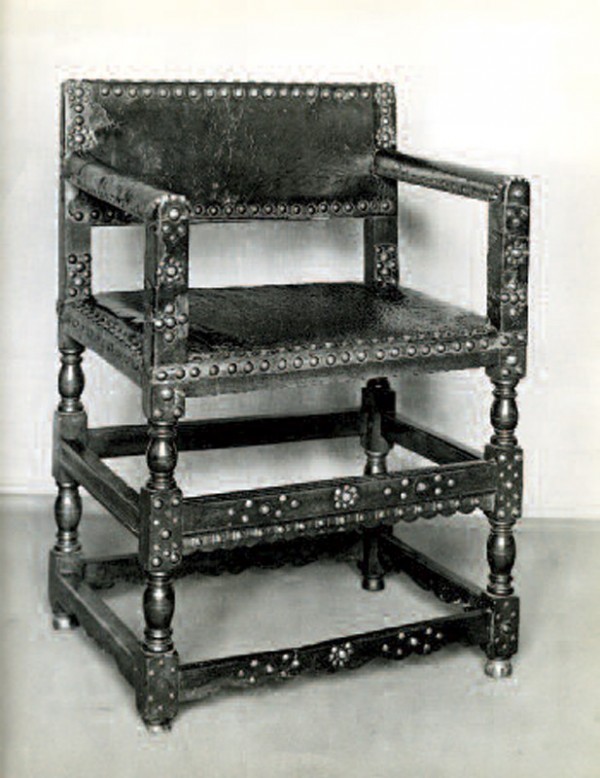

Armchair, attributed to the Symonds shop tradition, Salem, Massachusetts, 1675–1685. Maple and oak; with original upholstery foundation and leather covers. H. 38", W. 23 5/8", D. 16 3/8". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Seth K. Sweetser Fund, 1977.711.) The Endicott armchair underwent conservation in 1977 and 1978; Vincent Cerbone did the finish work, and Andrew Passeri and Robert F. Trent conserved the upholstery foundation and covers. The brass nails are period replacements in the sites of the lost originals. The outside back was reinforced, and the original webbing and sackcloth were reattached in several places. One small section of the trim strip on the front seat rail and one corner of the back cover were in-filled with pieces of leather from the back cover of an early eighteenth-century Boston chair. Merville E. Nichols washed the leather with saddle soap and treated it with a lanolin mixture.

Armchair, Netherlands, ca. 1620. Probably walnut; original upholstery foundation, leather covers, and brass nailings. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, R. W. Symonds Papers, collection 57, series 2, box 1, 59.428.) The extravagant brass nailing on this chair is reminiscent of Iberian seating. All four posts have urn turnings, and the back has moderate layback. While it appears that the seat and back have little loft, the leather covers probably shrank and deflected the stuffing.

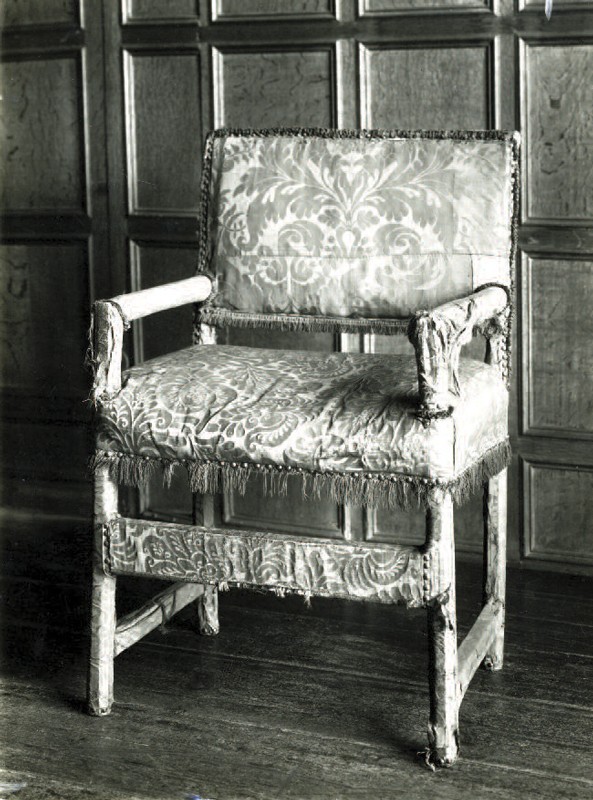

Armchair, possibly France, 1630–1670. Beech; silk damask. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, R. W. Symonds Papers, collection 57, series 2, box 1, 59.72.) This armchair is at Knole, Kent. The broad, flat front stretcher is common in sheathed chair frames. An extensive campaign to describe and conserve all the early upholstery at Knole is being conducted by conservator Heather Porter, Senior Conservator, Knole Conservation Studio, National Trust.

Detail of the armchair illustrated in figure 8, showing the stitching in the seat. Because the seat cover shrank drastically, the stitches appear to have snapped or to have been deliberately cut to prevent tearing.

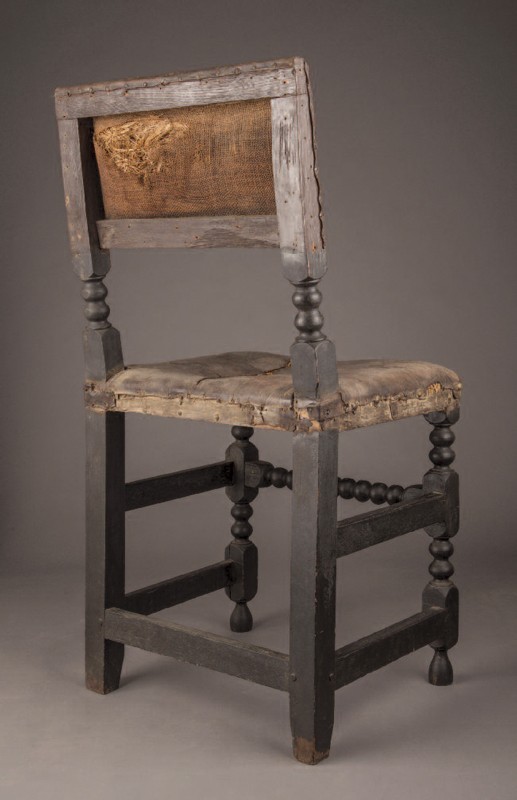

Side chair, probably Marlborough, Massachusetts, 1670–1700. Oak. H. 32 1/8", W. 18 3/4", D. 13 5/8". (Courtesy, Concord Museum, gift of Russell Kettell, F1094.) The chair retains the sackcloth and two webbing strips. One front post is replaced. Robert Walker, Andrew Passeri, and Robert F. Trent fabricated the nonintrusive upholstery panels and covers in 1984. There is no evidence of brass nailing, and the dimensions of the frame dictated the short fringe.

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1660–1700. Maple and oak. H. 35", W. 17 3/4", D. 17 3/4". (Collection of Anne H. and Frederick Vogel III; photo, Jim Schneck.) This frame has minimally intrusive upholstery with grass and horsehair stuffing and Russia leather covers from the cache of hides found in the 1786 shipwreck Metta Catherina in Plymouth harbor, England, in the 1970s. The discovery of the Russia leather hides is described in Geoff Garbett and Ian Skelton, The Wreck of the Metta Catherina (Truro: New Pages, 1987). The upholstery was executed by Mark Anderson.

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1660–1700. Maple and oak; with original upholstery foundation and leather covers. H. 36", W. 18 1/8", D. 17 1/4". (Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, bequest of Henry Francis du Pont, 58.694; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The original leather covers of this chair have a later coat of what appears to be a resin-based green preservative similar to those used on leather bindings by nineteenth-century librarians. Wadsworth Atheneum conservator Stephen Kornhauser removed similar coatings from chairs in that collection in 1984. At the same time that the green preservative was applied on this chair, a green painted piece of linen duck was added to cover the outside back.

Oval leaf table, Boston, Massachusetts, 1660–1700. Maple and oak. H. 27 1/4", W. (open) 48", D. 58". (Collection of Anne H. and Frederick Vogel III; photo, Jim Wildeman.) The top is a replacement.

Side view of the chairs illustrated in figures 13 and 14, showing modern, minimally intrusive upholstery in eighteenth-century Russia leather on the left and original, shrunken calf leather covers and deflected upholstery on the right. (Photo, Jim Schneck.)

Side view of the armchair illustrated in figure 8, showing folded flags going around the posts on the seat leather and the shrunken arm sheathing retreated back from the brass nails.

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1660–1700. Maple and oak; original leather cover and foundation upholstery. H. 37 3/4", W. 18 3/4", D. 15 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Jim Wildeman.) This chair was found recently in Newbury, Massachusetts. The stuffing and leather covers survived under many subsequent layers of covers. The black paint is probably nineteenth century and was applied with the later covers in place.

Rear view of the side chair illustrated in figure 18, showing the open outside back and back cover tacked to the side of the post.

Detail of the side chair illustrated in figure 18, showing the webbing and sackcloth under the seat.

Detail of the side chair illustrated in figure 18, showing the stitching and torn leather cover on the seat.

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1660–1700. Oak and maple; original Turkey- work covers, trim, and foundation upholstery. H. 37 1/8", W. 19 5/8", D. 19 7/8". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, bequest of Mrs. J. Insley Blair, 52.77.51; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The webbing and sackcloth in the seat and the sackcloth in the back may be replaced. The upholstery retains extensive fragments of wool fringe and galloon held by brass nails. This is one of the few Boston Cromwellian chair frames with great heels.

Side chair, Boston Massachusetts, 1675–1700. Oak and maple; original Turkey-work covers, trim, and foundation upholstery. H. 40 3/4", W. 20", D. 20 3/4". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, bequest of Mrs. J. Insley Blair, 52.77.50; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The upholstery retains extensive fragments of original fringe and galloon held by brass nails. The original webbing and sackcloth of the seat are supported by a modern prosthesis.

Detail of the couch illustrated in figure 1, showing the folded flag going around the left front post. (Photo, Bob Packert and Kathy Tarantola.)

Detail of the couch illustrated in figure 1, showing the folded flag going around the left rear post, traces of red wash or stain, and the angle from sawing out the post blank, which was cleaned up with a flat chisel.

Detail of the couch illustrated in figure 1, showing a fragment of fringe heading held by two brass nails on the front seat rail.

Detail of the couch illustrated in figure 1, showing a lacquered brass nail at the junction of the left arm and the rear post.

Detail of the couch illustrated in figure 1, showing the mortise for the keeper mechanism and the rolled covers brought around to the rear surface of the right rear post.

Rear view of the couch illustrated in figure 1.

Detail of the couch illustrated in figure 1, showing the underside of the seat with the webbing, sackcloth, and stitches for the front edge roll.

Detail of the couch illustrated in figure 1, showing the grass stuffing over the edge roll on the front seat rail.

Detail of the couch illustrated in figure 1, showing the hinge sites on the end of the right arm.

Detail of the couch illustrated in figure 1, showing the hinge sites on the end of the left arm.

Detail of the couch in figure 1, showing a rounded rivet head on the inside of the left arm.

Couch, Boston, Massachusetts, 1680–1700. Oak and maple. H. 42 1/8", W. 65 1/2", D. 29 1/8". (Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, bequest of Henry Francis du Pont, 58.698; photo, Jim Schneck.)

Detail of the couch illustrated in figure 35, showing the mortise and plugged rivet holes for an iron keeper on the rear surface of the right post. (Photo, Jim Schneck.)

Detail of the couch illustrated in figure 35, showing the rivet holes for hinges on the left arm.

Couch, Boston, Massachusetts, 1690–1710. Maple. H. 37 1/2", W. 21 5/8", D. 67 3/8". (Collection of Anne H. and Frederick Vogel III for the Philadelphia Museum of Art; photo, Graydon Wood.) The swiveling back frame is replaced. Mark and Terry Anderson fabricated the leather upholstery of the back frame and the stitched hair seat mattress.

Side chair, New York City, 1660–1690. Oak; original upholstery foundation and leather covers. H. 37", W. 17 7/8", D. 16 1/4". (Courtesy, Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association, gift of Joseph N. Fuller, 1880.47.1; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the chair in illustrated in figure 39, showing the webbing and sackcloth under the seat. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The seat has four webbing strips placed near the center of the seat. The stitching of the seat passes through three of the webbing strips, but it is possible the upholsterer placed the stitched rectangle too far back. If he had placed it an inch forward, the stitches would have passed through all four webbing strips.

Detail of the chair illustrated in figure 39, showing the location of the stitches on the seat cover. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Interpreting Boston Cromwellian chairs and couches involves the same interpretive problems confronted in all the Boston seating articles in this and the forthcoming issues of American Furniture. Why are these chairs attributed to Boston, when only one couch has a dependable history of ownership in that stylistic center (fig. 1)? The histories of the other documented chairs of this type are scattered across New England and New Jersey. The large number of surviving examples suggests that the chairs were made in quantity over an extended period, perhaps as long as forty years. With the exception of a few oval leaf tables, no obvious parallels can be drawn between the chairs and joined case pieces or tables attributed to Boston. Which of Boston’s documented joiners made the frames is difficult to say. They are, certainly, very consistent in design and workmanship, barring a few poorly made frames with badly executed turnings. Three or four successive, overlapping upholstery shops in Boston, documented by furniture historian Benno M. Forman (1930–1982) almost fifty years ago, provide a plausible scenario for the execution and transmission of the equally consistent upholstery over the 1660–1705 time span of the design.

However, the Boston Cromwellian chair differs from the successive Boston ”turned-stiles” and “molded-stiles” upholstered chairs of the 1700–1740 period in one significant way. The Boston joiners and upholsterers had competitors in eastern Massachusetts, in Salem, in Ipswich or Newbury, and in Marlborough. The more ticklish problem of identifying New York Cromwellian chairs centers on a Dutch-looking leather chair with a history in Deerfield, Massachusetts. Two other leather chairs with histories in Old Saybrook, Connecticut (at the mouth of the Connecticut River), and in East Hampton, New York (on the eastern end of Long Island), are not in Dutch styles and are less plausible candidates for being New York City products. A Swedish-looking chair with single-bine twist turnings has been attributed to Philadelphia, because Philadelphia was the only early North American population center with a sizable Swedish population. All these “outliers” to the Boston tradition are different in design and technique, and they seem to reflect London or Amsterdam or Stockholm prototypes with some fidelity. In other words, they are not necessarily imitations of the Boston product. Before Benno M. Forman began studying the seventeenth-century furniture of eastern Massachusetts in the late 1960s, no one even bothered to attribute Boston Cromwellians to that city. Most likely that reflected their former low status among collectors, compared to high-backed leather chairs with vasiform turnings and carved crests, front stretchers, and arms.[1]

Models and Date Ranges of Cromwellian Chairs in New England

Documentary evidence of importation of English upholstered chairs to Boston prior to 1650 is scarce, although the Aspinwall Notorial Papers include references to one dozen Russia leather chairs being imported from London in 1650 and to importation of Russia leather hides in 1648 and 1650. Establishing what these early imported frames looked like is difficult, because most pre-1650 documented English seating represents extravagant royal or noble commissions, notably the famous Charles I suite of couches, chairs, and stools at Knole, Sevenoaks, Kent. This style is documented in French chairs shown in suites of Parisian engravings by Abraham de Bosse (c. 1604–1676). The heavy frames have Doric columns on the posts and spherical feet. Often they were used with tables and case pieces ornamented with the same columns. Another fixture shown in the de Bosse prints is the folding stool, much like the 1745 Boston example illustrated as figures 1 and 2 in Robert Trent’s article about other furniture forms in this volume.[2]

Cognates for these French-looking chairs undoubtedly were used in New England before 1650, as shown by the elaborate inventories of elite figures in New Haven, Connecticut, who were from London. The inventory of Governor Theophilus Eaton (c. 1590–1658) of New Haven, published by the antiquarian George Dudley Seymour (1859–1945) in 1938, lists numerous suites of high and low upholstered chairs and stools. One surviving New Haven upholstered stool with Doric columns is the only known New England seating in this manner, barely to be distinguished from joined seating intended to have board seats (fig. 2). Indeed, furniture scholar and dealer Wallace Nutting (1861–1941) provided it with a wooden top, even though fragments of webbing survived on the seat rails. Edward Winslow (1595–1655) of Plymouth, Massachusetts, owned an important London upholstered armchair (fig. 3). He may have purchased this armchair there in the late 1640s or early 1650s, when he was serving a series of high offices in Oliver Cromwell’s government. Winslow died in 1655 while taking part in the so-called Western Design, a naval expedition to the West Indies. His son, Josiah (c. 1628–1680), who lived in Marshfield, Massachusetts, probably inherited the chair, although there is an outside chance that the younger Winslow purchased the armchair in 1651, when he visited his father in England. The Winslow chair suffered a number of alterations over the years, including the addition of iron brackets to convert it into a sedan chair, but most of the alterations were reversed by Robert F. Trent and Peter Arkell in 1985, based on an identical armchair with fragmentary crimson silk velvet upholstery at the Victoria and Albert Museum. A photograph taken before the museum acquired their armchair in 1953 (fig. 4) suggests that the Winslow armchair also had gilding and painted decoration over a layer of gesso. The unfaded portion of the original velvet covers on the back of the Victoria and Albert chair above the arms indicates a second row of fringe, in addition to an identical fringe at the bottom of the back. This treatment is also seen on the set of early seating at Knole.[3]

English cognates for the Boston Cromwellian chair, with characteristic ball turnings, are usually assigned to the 1650s or 1660s by furniture historians, without much evidence to confirm that date range. What is important about this type of frame is its clear departure from contemporary joined seating with board seats. The frames are lighter, with a fairly standard 1 7/8" stock and rear posts with a significant layback—typically 12.5 degrees. English versions often were made of beech or oak, while the New England versions are usually maple and oak. The rear posts taper in depth above the seat, and they terminate in a chamfered or rounded crest. It would appear that this style of frame was made in substantial numbers in London, since weavers in Bradford, Yorkshire, and Norwich, Norfolk, began turning out large quantities of “setwork” or “Turkey work” knotted pile wool covers for such seating, much in the manner of southwest Asian carpets. The same weavers provided matching wool fringes and tapes to trim the chairs. Another prestigious cover was imported Russia leather, as opposed to locally produced calf leather. Across the board, the best quality upholstery covers were usually robust wools, but sometimes silk damasks, and wool chairs were also trimmed with wool or silk fringes and galloons—tapes, after the French galon—of greater or lesser complexity.[4]

A different London design may date from this same period or slightly later. Based on Dutch upholstered seating, the design features urn turnings on the front posts. Two examples of this design that appear to be from the same shop are undoubtedly New England products, most likely from a major port, possibly Boston (fig. 5). Previously Robert F. Trent attributed these chairs to New York City, on the basis of their Dutch-looking design, but London chairs of this exact model, made for the royal palace of Holyroodhouse in Edinburgh around 1668, suggest otherwise. The two New England chairs are to be distinguished from the extremely Dutch-looking chair at the Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association in Deerfield, Massachusetts, discussed below (fig. 39). One of the chairs (Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut) has a high front stretcher and molded ornament along the bottom edges of the seat rails. The other has upholstery entirely over the rails and a low front stretcher (fig. 5).[5]

Most English furniture scholarship concurs with Connoisseur articles written in 1934 and 1951 by the English furniture historian Robert Wemyss Symonds (1889–1958) that upholstered or wooden-seated chairs with ball or reel or twist turnings date from the mid-1650s to the 1680s. The period description for ball or reel turnings (or combinations of ball and reel turnings) was “turned all over,” whereas spiral turnings (partially executed with a coarse file) were called “the twisted turn.” The frames of four upholstered chairs with reel turnings, here attributed to a shop located in Ipswich or Newbury, Massachusetts, undoubtedly are based on imported London prototypes (fig. 6). In the 1970s and 1980s, Robert F. Trent attributed these chairs to Salem, Massachusetts, but subsequent intensive study of case pieces from Ipswich or Newbury has led to their re-attribution. The aggressive merchants of ports on the North Shore of Massachusetts were determined to compete with Boston, and they undoubtedly encouraged local artisans to make the frames. Surprising, all four frames display different decorative formats, and the joiners involved must have made substantial numbers of such chairs, even though only four survive. All four chairs from the group have a rounded top on the crest rail, which generally are associated with textile covers. A “Turki work Loom” is listed in the probate inventory of Samuel Rogers (1635–1693) of Ipswich, Massachusetts. His father was the town minister, Reverend Nathaniel Rogers (1578–1655). Samuel’s first wife Judith (1634–1653) was a member of the influential Appleton family, and his second wife Sarah Wade (1641–1717) was also from a prominent family. Sarah Rogers probably used the loom and may have been among a group of elite women who produced professional-caliber, knotted pile covers for locally made chair frames.[6]

A pair of high-backed side chairs with twist-turned ornament on the posts and front stretcher, at the Winslow House in Marshfield, Massachusetts, was identified as being made of American maple thirty-five years ago, although the validity of the wood sample has been questioned. Other Cromwellian chairs with twist turnings and Massachusetts histories of ownership were identified by wood anatomist Gordon Kelsey Saltar (1906–1988) as being made of American beech, but Saltar’s analyses for separating American and European beech are no longer accepted. In other words, all previous attributions to New England of Cromwellian chairs made of beech should be reevaluated.[7]

A newly recognized side chair with all-over ball turning, including a ball-turned back with five vertical spindles, may represent a New England or New York version of a style popular in London in the 1670s and 1680s (fig. 7). Made entirely of maple, the frame originally had a board seat held in grooves in the seat rails but was overupholstered later, perhaps when the seat board or the left seat rail failed. Most such frames have an oak seat board, even if the frame is walnut. Generally, white oak was selected for the seat board because it is much stiffer and stronger than red oak, which tends to deflect more and snap under pressure. Two other black walnut examples with twist-turned frames, long attributed to Philadelphia because of their histories of ownership in New Jersey, cannot be proven to be American. The Pearson or “Crosswicks” chair (Winterthur Museum, 1957.1389) has an original white oak seat board, and American white oaks cannot be separated from English white oaks by microanalysis. Further, both the Crosswicks chair and the related chair (Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1923-23-53) have black walnut frames, but black walnut was exported to England in quantity. Nevertheless the strong histories of ownership of the two chairs are plausible evidence for American origin, perhaps in the prosperous Delaware River port of Bordentown, New Jersey.[8]

The all-maple chair has ball turnings quite like those of Boston upholstered Cromwellian chairs, although it lacks the central reeded disk on the front stretcher (fig.7). Other details typical of this London type of frame are four turned vasiform feet, a high rear stretcher on a level with the front stretcher, and ball finials. This kind of frame may have provided a source for the acorn finials on a later Boston Cromwellian couch (fig. 38) and three related side chairs. A recent study of New York Dutch turned chairs makes it evident that this London style of joined chair with a board seat was heavily influenced by Dutch designs, as were the earliest London cane chairs. Paradoxically, English bills for such chairs sometimes denote them as “French,” and one surmises that this term was chosen as prestige branding, rather than a literal description of the stylistic origins of the frame.[9]

A major monument of the Cromwellian style in New England, the Endicott armchair, previously was attributed to Boston, but here is re-attributed to the Symonds joinery shops of Salem, Massachusetts, based on its provenance and ornamentation (fig. 8). The probable first owner of the armchair was Dr. Zerubbabel Endicott (1635–1684) of Salem, son of Governor John Endicott (1588?–1665) of Salem and Boston. Dr. Endicott was related by marriage to all the owners of four elaborate cabinets that are attributed to the Symonds shop tradition. Also, Dr. Endicott’s son married a daughter of Samuel Symonds (1638–1722), one of the Symonds joiners. The Endicott armchair and one of the cabinets descended in allied families, and both were owned by a single descendant in the early twentieth century, when they were sold to the collector Helen Jaques (1894–1976) of Marblehead, Massachusetts.[10]

As the only surviving New England Cromwellian armchair, the Endicott example is of considerable importance in determining what such a frame looked like and how it was upholstered. One important feature is the width of the frame, 23 5/8". Most Cromwellian side chairs are 18–18 1/2" wide. The extra five inches in width in an armchair mostly consisted of the arms themselves, which are almost two inches wide each, including the leather sleeves and brass nailing. Other important features are the front and rear posts immediately above the seat, which have no turned ornament, but are chamfered on their inside edges and partially sheathed with leather sleeves. Some Boston Cromwellian side chairs have unturned rear posts between the seat and the back, sometimes chamfered on the inside forward edge, sometimes not. Obviously this treatment may reflect cost cutting; by leaving the rear posts unturned, the makers avoided having to use an elaborate chuck system in the lathe in order to turn the posts. However, the Symonds joiners of Salem executed their own turnings, so economy of means is not the only possible explanation.[11]

Other possible influences on the design of the Endicott armchair are French and Dutch Cromwellian chairs where the arms and the front posts are rounded on their upper or outer surfaces and meet in what appears to be a neat miter at the front. Usually the posts and the arms are sheathed with leather or a textile. Such frames were influential in London, as noted above in connection with the London chairs made for Holyroodhouse in Edinburgh around 1668. A Dutch leather armchair of about 1620 (fig. 9) has an elaborate joined frame with double stretchers on all four sides and abundant brass nailing on the leather covers and on the frame, consisting of smaller brass nails and larger brass “bullions,” as they are called in English royal invoices for seating of the 1640–1670 period. Here the front posts are left square, while the arms are rounded.[12]

A second English or French example at the historic house Knole in Kent may date from 1630–1640, but it could also have been made just after the restoration of Charles II, between 1660 and 1670 (fig. 10). The frame is elemental but enlivened by extensive chamfering and rounding. Again, such frames were intended for extravagant covers and trim. An early seventeenth-century upholsterer described similar seating made for Queen Henrietta Maria of England in 1637 as “Covered all over on Rayles, Styles [i.e., the stiles, or upper portions of the posts], and feete [the lower portions of the posts].” This early twentieth-century photograph of the Knole armchair shows that the original covers were patched or renewed with seventeenth-century textiles, but the characteristic, original mitering of the covers at the front of the arms is evident. The chamfers on the frame were partially intended to prevent chafing on the edges, as well as to lighten the visual and actual weight of the frame. These chamfers are the immediate antecedent for chamfered crest rails, chamfered posts, and chamfered arms on somewhat later Cromwellian frames. The Knole armchair is quite like the upholstered chairs used at Louis XIV’s court before the advent of higher backed frames about 1670 and may in fact be of French origin.[13]

Earlier in the evolution of the Cromwellian chair (and allied ceremonial seats of curule design), a cofferer, or even a saddler, might have executed the upholstery. Similarly, chairs made outside Boston had to be stuffed and covered by artisans like saddlers, for few professional upholsterers are documented elsewhere in eastern Massachusetts until the eighteenth century. One exception, discovered by Benno M. Forman, was George Herrick (arrived before 1685—died 1695), who may have been active in Salem when the Endicott armchair was made. The armchair does have the characteristic stitched seat associated with professionally upholstered leather chairs (fig. 11), but saddlers used similar stitching and could have provided that feature after examining a Boston or London prototype. The turnings of the Endicott armchair are much like those on Symonds case pieces and tables. The front stretcher lacks the central, reeded disk seen on Boston chairs, and the transitions from the turnings to the posts differ as well. Above all, the Endicott armchair is noticeably lighter in weight.[14]

A final eastern Massachusetts Cromwellian chair with a history in Marlborough in Middlesex County retains some original webbing and sackcloth (fig. 12). The Marlborough chair has a low seat, a feature associated with seating for women. Inventory references with descriptions like “high” or “low” are somewhat ambiguous. In some instances, the terms refer to the height of the seat, while in other instances the terms apply to the height of the back panel. The Marlborough frame is remarkable for its pronounced great heels; that is, the rear posts end in a distinct jog on both front and rear faces, unlike most Boston chairs, where the posts have a chamfer on the front face of the heels but run straight to the ground on the rear face. The Marlborough chair also has two urn turnings on the front stretcher, an early appearance for this motif in New England seating.[15]

The upshot of these stylistic factors is that the so-called standard Boston Cromwellian frame probably went into production in the 1650s, but one other stylistic feature plays out in the course of the Boston tradition. Higher backs seem to have been introduced about 1680 (see figs. 1, 23), if English practice is any indication. Furniture historian Peter Thornton (1925–2007) demonstrated that chairs with higher backs were introduced at Louis XIV’s court about 1670 to 1675. High-backed Cromwellians were fashionable in New England from 1680 until 1705, and they overlapped with high-backed chairs with columnar, turned posts. This date range overthrows the traditional English practice of dating the inception of high backs to the restoration of Charles II in 1660, and it pushes the inception of the so called “William and Mary” style in New England at least five years later than the previously accepted date of 1695. It is difficult to say in what style a chair frame in a New England probate inventory of about 1700–1705 would have been, nor was Turkey work ipso facto old-fashioned as of that date.[16]

The one caution regarding the date range of high backs on Cromwellian frames is the couch form. Couches dating from the 1640s had high backs, as did chairs made en suite with them. Such high-backed seating seems to have been restricted to elite clients; low-backed couches upholstered in leather are not unheard of in England. For the most part, New England high-backed Cromwellian chairs and couches are to be regarded as dating 1680 to 1705. The most spectacular instance is the 1698 Leverett couch (fig. 1).[17]

Wood Extraction

The lumber sourcing and construction of early Boston upholstered chair frames play upon a number of questions in the scholarly literature. In the late 1960s, furniture historian Benno M. Forman sought to identify both London and Boston joinery. His idea was that all lumber in both locations had to be imported from elsewhere, and he posited that this lumber was more likely to have been sawn. In the thirty-seven years since Forman’s death in 1982, it has become evident that both sawn and riven lumber were commercially exploited in London and in Boston. The trick is to examine the components of furniture to determine the orientation of the ray plane and to look for telltale riving tear-outs on concealed surfaces. For example, in 1975 Forman asked Robert F. Trent to examine all external and internal surfaces of the Boston chest of drawers with doors at Yale University Art Gallery, to determine if any saw kerfs or riving tear-outs were visible. It so happens that all the internal and external surfaces of that object are planed smooth and no riving tear-outs are visible. Ultimately, however, even if all the surfaces of a given component were planed smooth during fabrication, lumber where the broader surfaces reveal medullary ray figure need not have been fabricated of riven stock and may have been made from quarter-sawn lumber. It was not all that likely in American work, but it was possible. This applies to ring porous oak as well as to diffuse porous maple. Ironically, Forman attributed the upholstered chairs under consideration here to Boston, even though the frames betray ample evidence of riven oak and maple.[18]

Examination of Boston Cromwellian chair frames reveals variable wood usage. While the four posts and the front stretchers invariably are maple, the other horizontal components—side and rear stretchers, seat rails, crest rails, and stay rails—display different woods. Some frames are mostly maple, with oak restricted to the seat rails, crest rails, and stay rails. Other chairs have more oak in them, including the side and rear stretchers, seat rails, and back and stay rails. Obviously, availability of lumber was key. The rear posts had to be made of maple plank roughly two inches thick to permit nested-sawing of the blanks. In other words, the posts, with their characteristic two-axis side profile, had to be sawn, and conserving lumber meant laying out four or so rear posts across a hypothetical twelve-inch-wide plank. It also meant that the side profiles of the posts would not necessarily lie on the ray plane, given that most sawn plank does not. Insofar as front stretchers and front posts are concerned, they could be made of sawn wood, but many reveal riving and hatcheting marks, which suggest that some components were reduced to dimension using the swift riving and hewing technique.

Standardization of components was a relative procedure. Ideally the rear posts were 1 7/8" square at the level of the seat rails. This measurement seems to have gone far back in the history of English and French upholstered chair frames (although many Dutch frames are lighter in weight). Joiners may have felt that a post with finished measurements of 2" square looked too bulky, while posts 1 5/8" or 1 3/4" square appeared too scant. Of course, the fairly widespread 1 7/8" square finished measurements were also directly related to the 2" plank from which the posts were sawn. Incidental circumstances of wood supply, including the occasional use of planks that were well under two inches thick, meant that some chairs had front posts that were full measure but had rear posts that were scant. All these observations also apply to later upholstered chair designs. Similarly, swift riving, hatcheting, and planing of subordinate components like side and rear stretchers, seat rails, and crest rails and stay rails, often led to the use of scant or otherwise substandard parts. Generally speaking, some effort was made to keep the outer and upper surfaces full thickness, but tear-outs, somewhat pentangular cross sections, and knot or knurl losses were tolerated with surprising frequency. These sorts of flaws are quite similar to those seen in London upholstered and cane chairs of lesser quality. In the better sort of London upholstered frames, the shop masters did not tolerate such flaws. The Holyroodhouse chairs purchased in London about 1668 are beautifully made, with excellent, full-dimension lumber, a high degree of finish, and exacting joinery.

Statics and Dynamics of the Cromwellian Seating Frame

The Boston frames illustrated in figures 13 and 14 embody the collector’s and curator’s ideal specimen. They have full, robust ball turnings with filleted transitions to the arrises and thence to the blocks on the posts. They have a reeded disk or reel at the center of the stretcher. They retain almost all of the turned feet on the front posts and the chamfered heels on the forward faces of the rear feet. They have the appropriate angle to the back, with ball turnings between the seat and the back panel. One frame retains original webbing and some fragments of original sackcloth; the other has almost all the upholstery foundation and leather covers. The chair illustrated in figure 13 has had a later layer of black paint removed, but some evidence of original surface remains. The evidence for iron tacks and brass nails has not been marred by multiple later upholstery treatments.[19]

Few have stopped to consider factors beyond such antiquarian desiderata. The performance of such seating furniture is not like those of case pieces or tables. For the most part, case pieces are literally static structures. The principal stress on a case piece is the weight of the objects stored in or on it. In those case pieces that have hinged lids, the upper rear rails are subjected to strain by opening and closing the lid, which can be considerable if repeated thousands of times. The rail might even experience torque if the lid is heavy and if it is not propped up correctly or allowed to swing back too far. The torque can take the form of stress distributed along the length of the rail, and in extreme cases, it can twist the tenons at each end.

Tables are also quite static. The only dynamics are the weight of the objects placed upon them and the lateral stress of feet upon the stretchers, or the weight of those seated at the table if they lift themselves up by pushing down on the top boards. One exception might be tables with hinged leaves. Those sorts of tables were also moved about far more than in modern usage, and clumsy lifting of the table by the top rather than by the frame can have obvious consequences. There are a lot of antique chests with replaced lids and a lot of tables with later tops!

In seating, entirely different sets of stresses are imposed on the frame. Obviously such frames are not static, because chairs were moved back and forth between the walls and tables in the center of the room, and the common habit of picking them up by the crest rails was of course perilous. When in use, the weight of the sitter is one kind of stress, and people are not static. As demonstrated by Niels Diffrient (1928–2013), the inventor of the air piston office chair, sitters tend to shift around when seated for any length of time. During the seventeenth century, decorum usually inhibited sitters from tipping back on the hind legs of a chair, although numerous Dutch paintings show carousing soldiers and peasants doing so. These kinds of stress were supplemented by sitters falling into and rising up from the frame, and the back itself, a novelty to those used to perching on stools or forms, allowed sitters to press back to a certain degree. The lack of pronounced heels on the rear surfaces of the rear posts of Cromwellian frames meant that leaning back in a slouching manner would overturn the chair.[20]

Cromwellian chair frames were subjected to some side-to-side strain by shifting occupants, but most of the stress was fore and aft, hence the use of double side stretchers. The angle of the sawn back posts meant that a principal flaw of the design was the short grain immediately above the seat rails, which could and did split with some frequency. Upholstered frames have an additional problem, straining and tacking the webbing and sackcloth on the seat rails and front post tops. Many Boston frames have seat rails bowed-in and even tipped inwards by this strain, and much of the damage probably occurred soon after the frames were upholstered, because the components were still somewhat above ambient humidity and were consequently still soft. Because the tacks were being driven down into the tops of riven rails, they were putting pressure on the medullary plane of the wood and could cause splitting.

Prolonged usage led to a long-term kind of structural failure, known as wracking. Other than outright breakage, wracking usually involves the shoulders of the tenons embossing the adjacent posts to the point that the frame can begin swiveling on the pins that hold the tenons in the mortises. Not all the joints of a Boston Cromwellian chair are pinned, but the seat rails, front stretcher, lower side stretchers, and rear stretcher always are. The pins themselves are rather large, about 3/8" square. They seem to be associated with some degree of draw-boring of the joints. The draw-boring system during the seventeenth century relied on relatively dry horizontal components being tenoned into somewhat wetter front and rear posts. Because these frames were made in quantity, shops must have prefabricated and stockpiled substantial numbers of dry horizontal components, while the four posts were sawn from somewhat wetter plank as needed. That these frames were constructed using the draw-bore technique is borne out by the slightly raised heads of the pins.

In the draw-bore system, as employed in case pieces, the inner shoulders of the tenons are undercut to insure that the outer shoulders of the joints—the ones visible on the exterior—meet tightly when the pins are driven in. In tables or chair frames, the system has to be modified, because grossly undercut inner shoulders on the joints would be visible. Boston Cromwellian frames have relatively little undercutting of inside shoulders on the stretchers.[21]

The original finish on such chairs has not been systematically investigated by the analysis of finish sections. Some chairs have what appears to be a thin red wash, and the Leverett couch has a thicker red wash on the rear surfaces, which may be a later cosmetic intervention. However, it seems implausible that the frames were left unfinished, and more technical research is needed on Massachusetts seating of the 1660–1730 era. A written source dating from the very end of the Cromwellian era sheds some light on what New England clients wanted in terms of color and surface luster on chairs. The Boston upholsterer Thomas Fitch (1669–1736) wrote to his London factor, William Crouch, on February 1, 1702/3, complaining about the finish on London cane chairs (presumably beech) Fitch had received earlier: “Please to mind that what chairs ye send be not of a reddish colour, but a good natural walnut, browne colour and well Varnished and let what I have writ for if not sent be most of ym worth five Shillg apc Sterling & a Fashonable neat shape and well varnished; I have no Service of any of the varnish that ye have sent me hardly, out of a 2 or 3 Gallo runlet I have not had above three pints and that not good witha [i.e., withall], the rest has been gross mattls [i.e., materials] which I take to be gum & Turpentine or Rosin not dissolved which must be for want of being honestly made at first, or thro age, or by being in wood runlets, tho possibly the rectified Spirits which dissolve the gums might evaporate: If therefore the chair maker will varnish ym better there, and give ym with each [parcel?] a Stone[ware] bottle of about two or three Quarts of good new Varnish, well stopt it may do [well?] and indeed I think it no more than he ought to do since I have been so disappointed in what I have hither to had.” The reference to a reddish finish as undesirable may suggest that the red stain found on several Boston Cromwellian frames represents a late seventeenth-century preference and not the current fashion for 1702. However, there is a possibility that the red stain was supposed to be brushed over with a walnut-colored varnish. The importance of this varnish reference, in addition to comments on color, lies in the components used to make the varnish. As opposed to the more durable and labor-intensive oil varnishes, this recipe calls for simple dissolving of alcohol and/or turpentine soluble resins (and “gums”). The recipe would produce a glossy but brittle, nondurable coating prone to developing a dark color and craquelure because of photodegradation.[22]

Turned Ornament

The ball ornament on Boston Cromwellians is specific to that city’s chairmaking tradition. Curiously, only a few Boston oval leaf tables have the same ornament (fig. 15). The lack of affinity between Cromwellian turnings and almost all the other recognized Boston turned ornament on case pieces and tables is curious, and it suggests that the shops producing the upholstered frames had little if any affiliation with the Mason and Messinger joinery traditions to which the case pieces are attributed.[23]

Incidentally, the ball turnings highlight several factors in fabrication. In those cases in which the post stock came up scant, the turnings often pass out of the work, leaving prominent flats. In some cases, the flats may have been caused by failure to place the element in question on centers in the lathe bed. The rear posts above the seat often display flats on the rear surface, most likely because the tapers on the posts were sawn out of line or over the line. Sometimes the ball turnings in that location are smaller in diameter than those on the rest of the frame, because of a problem with the stock. Another factor might be the off-axis chuck used to turn the balls on the rear posts. If the post was inserted into the chuck inaccurately, then the turnings would have been slightly off-axis and very often flat on one side.[24]

Stuffing, Covers, and Ergonomics

Benno M. Forman’s unpublished 1969 manuscript, “Boston Furniture Craftsmen 1630–1730,” details a succession of upholsterers active in that city beginning with William Allen (1637–1674), who began working in 1662. Forman hypothesized that merchant Edward Tyng (1610–1681) brought Allen to Boston from England. A succession of upholsterers followed, including Ebenezer Savage (1660–1686), Edward Shippen (1639—departed to Philadelphia 1688), Edward Tyng’s son and namesake (1649–1701), and Jonathan Everard (arrived 1688—died 1704). The life dates of these individuals suggest that their careers overlapped and that some may have served as apprentices or journeymen in the shops of their predecessors. In sum, enough of a paper trail exists to explain why the upholstery of all Boston Cromwellian chairs is so consistent.[25]

Cromwellian frames have always been considered crude compared to their successors. From an ergonomic point of view, the opposite is true. The back panels were designed to accommodate heavy stuffing and contact the sitter at the juncture of the lumbar and thoracic vertebrae, right under the lungs (fig. 16). This permitted the thoracic portion of the back to rest over the crest rail for optimal posture. The high seats of Cromwellian chairs were associated with footstools and stretchers on tables, as indicated in period prints. With the introduction of higher backs, this interaction of the sitter with the back panel was lost.

The stuffing system varied from modern practice in many respects: the number and distribution of webbing strips was quite low; the frames of middle-class chairs were stuffed with grass, rather than curled horsehair; the covers were visibly attached with wrought-iron tacks; and the seat covers of leather chairs were attached with a central stitched well (fig. 21). The heavy webbing of English chairs was woven in a 2" width (as opposed to French webbing, which was usually 3" wide). Cromwellian side chairs and armchairs usually had two strips running from front to rear and one from side to side (fig. 20). The webbing strips were situated to coincide with the stitched panel in the center of the seat. Over the seat was laid heavy linen cloth, usually called sackcloth in the period, although other names were used for it. In modern upholstery, the sackcloth is basically intended to contain the stuffing, while most of the support is assigned to the webbing. In Cromwellian stuffing, both the webbing and the heavy sackcloth had support duties.

The usual stuffing of middle-class Cromwellian seating in England and the colonies was grass. In many Massachusetts chairs, the stuffing is marsh grass harvested from salt marshes along the coast, but in other cases it may have been sweet grass from meadows. The grass was installed in carefully aligned handfuls, and it often was bent to go around corners. In chairs with textile covers, the entire seat was filled with grass. On leather chairs, the grass was installed around a central 5" x 3" well in the seat, created by a stitched rectangle that passed through the leather covers, the sackcloth, and the webbing (fig. 21). Generally there are ten stitch holes on the long sides of the rectangle and six stitch holes on the short sides. The stitched panel is sited 5 3/4" back from the fore edge of the front seat rail. The stitches may have been executed with a double-ended quilting needle or a long single-ended needle. While it is not entirely certain, the holes for the stitches in the leather covers may have been pierced with an awl before stitching, partly for accuracy, partly to prevent tearing the leather. An even number of stitches is required on each side of the rectangle, otherwise the stitching will conclude with a loose end in the air. The idea is to have the first stitch come up from underneath and the last stitched to go down, so that they could be tied off underneath.[26]

The leather covers probably were applied wet, or at least damp, as they were more pliant in that state. The front corners on side chairs are made with the pleats facing forward, which is completely inconsistent with modern practice. On some chairs, the rear corners are made with a folded flag, which is drawn around the rail (fig. 17), while in others, the rear corner is made with simple pleats drawn almost straight down. The seat covers are tacked halfway over the rails, because they were covered with trim strips about the same height as the seat rail or slightly shallower. The back covers were drawn just around the sides of the rear posts and tacked, while the upper edge was drawn over the crest and tacked to the upper rear edge of the crest rail (fig. 19). The decorative brass nailing is largely ornamental, without any genuine structural function. This changed on later, high-backed chairs, which have corresponding back covers secured with brass nails.

New England probate inventories draw a distinction between imported Russia leather and domestically produced calf leather. It is possible that other obscure kinds of leather, like imported Morocco goatskins, were also present, almost certainly as an incidental side use of hides intended for bookbinding. Russia leather on period chairs can usually be detected by the characteristic fine, diamond-shaped hatching on the hides; however, such hatching was sometimes simulated during the period on domestic calf leather. Other exotic leathers likely present on imported chair frames included tooled varieties of Spanish origin and embossed, gilded, and painted leather, a specialty of the Dutch.[27]

A final factor to bear in mind with leather covers is traumatic shrinkage (figs. 18, 21). This has been attributed to autoxidation of oils in the leather, to inherent degradation of collagen, and to exposure to moisture and high heat. The result is stiffening, hardening, and dramatic loss of surface area. The six Boston leather side chairs and one Salem leather armchair that retain their foundations and leather covers have experienced some degree of deflection of the stuffing by the shrinking leather. The seats usually have the stuffing pressed down into the webbing and sacking, while the backs usually have the bulk of the stuffing forced into the open outside back. In some cases, notably side chairs at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the Wadsworth Atheneum and the chair illustrated in figure 21, the seat covers tore after the stitches gave way; the leather drew up into a taut drum over the stitching well, and the seat subsequently tore as sitters placed pressure on the taut membrane.[28]

“Turkey-Work” Chairs and Couches

Only five Boston seating forms survive with original Turkey-work covers and a substantial amount of their original foundations: one low-backed side chair (fig. 22); three high-backed side chairs (fig. 23; another is in the collection of the New York State Department of Parks and Recreation and one is not located); and one couch (fig. 1). Unfortunately, English antique dealers of the early twentieth century—notably Samuel Wilfred Wolsey (1889–1958)—habitually cut up period Turkey-work carpets to upholster chair frames, thus confusing the issue of what an English Turkey-work chair or couch would have looked like. In some cases, the frames on which the cut-up covers were placed were of the period; in others, the frames were modern replicas or fantasies. Perhaps the most notorious of these concoctions is a set of Cromwellian revival side chairs with chamfered frames covered with chopped-up, period Turkey-work carpet covers, now divided between the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Brooklyn Museum. In a few instances, notably the Victoria and Albert Museum side chair with 1649 covers cited below, dealers or curators mounted period chair covers on a period frame.[29]

Professionally woven and knotted pile carpets, chair covers, and other fixtures, from Bradford, Yorkshire, and Norwich, Norfolk, are known, but little is known about specific manufactories or production in other areas of England. These textiles were woven on a stout, single warp/double weft system of linen cords, with knotted wool pile. Earlier in the tradition, the designs tended to imitate southwest Asian carpets, complete with wide borders. The vast majority of surviving Turkey-work upholstery covers date later in the tradition, when the pattern was reduced to repetitive, stereotyped flowers with narrow borders. Sometimes the design is reversed side-to-side, an indication that the weavers repeated the pattern by rote. The back and seat covers of the Leverett couch are a spectacular instance of this; the weavers simply wove a standard chair back pattern and then repeated it two more times to achieve the width needed to cover a couch. A detailed inspection of the covers in 1979 by Robert F. Trent, Benno M. Forman and Scottish textile historian Margaret Swain (1909–2002) confirmed that the seat and the back each were woven in one piece.[30]

Several documented English chairs with Turkey-work covers survive and provide context for Boston usage. A high-backed Cromwellian chair with twist turnings on the frame and original upholstery foundation and Turkey-work covers (Temple Newsam House, Leeds, Yorkshire) retains “campaign” [from the Italian campagne for bell-shaped] fringe and woven galloon, clearly made en suite to trim the selvedges of the covers. This chair is thought to be one of thirty-six purchased in London in 1680 for Hampton Court, Herefordshire (not to be confused with the royal palace of the same name). Another important set of fragmentary covers with the date 1649 woven into them (Victoria and Albert Museum) currently is mounted on a London Cromwellian frame made perhaps a decade later; the covers give the earliest known date for the stylized floral pattern that remained in production until the early eighteenth century.[31]

Petitions to Parliament by wool manufacturers in the 1680s and 1690s provide some sense of the scale of Turkey-work production. These petitions, published by R. W. Symonds in 1934 and again in 1951, claimed that 60,000 (5,000 dozen) Turkey-work chairs, 240,000 (20,000 dozen) chairs upholstered in various wools, and £40,000 worth of silk fringes made to trim them were produced each year. The petition also claimed that many of these chairs were sent “beyond the seas,” or exported, to Europe and the British colonies. While these figures undoubtedly were inflated for purposes of special pleading, they do demonstrate that Turkey-work was not an incidental decorative product, but part of a major industry.[32]

The Leverett Couch

The three Boston side chairs with original Turkey-work covers now in institutional collections have experienced some degree of restoration; one of the chairs (Metropolitan Museum of Art) has partially replaced or reinforced webbing and sackcloth and another (New York State Department of Parks and Recreation) has a renewed foundation. A high-backed chair with a low seat, illustrated by Luke Vincent Lockwood in 1913, has not been located. Because the repairs on the institutional chairs were executed with extreme restraint, the two examples in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art retain almost all their original tacking and brass nails and extensive fragments of 1/2" fringe heading and surprisingly narrow 3/8" galloon. The seats were stuffed with full-width bundles of grass in the front and the rear and partial-width bundles on the sides. While these bundles were not sheathed in linen, they functioned much like edge rolls, and the centers of the seats were filled with smaller bundles of grass. Curiously, the two Metropolitan Museum chairs have the kind of chamfered crest associated with leather covers, unlike the two couch frames, which have rounded crests.[33]

The Leverett couch is of international significance as an undisturbed monument that has been preserved as a respected antiquity since the mid-eighteenth century (fig. 1). It is the only couch in England and America to retain the original upholstery foundation and Turkey-work covers. The only other known Boston Cromwellian couch has no surviving upholstery foundation or covers (fig. 35). Although the history of the Leverett couch was traced forty years ago, it is useful to repeat the history here, because the probate citations illuminate the stylistic sequence of Boston Cromwellian design. Before 1977, the only information in print about the couch’s history was a well-known citation for May 18, 1819, in the diary of the minister Reverend William Bentley (1759–1819) of Salem, Massachusetts:

This day I was at a Vendue where I received from the family of Appleton a settee, which was formerly in the family of Dr. Appleton, Dr. Holyoke, now living aet. 91, & son of President Holyoke, near neighbor to Dr. Appleton at Cambridge, recollects the Settle for 80 years, & it is an ancient part of the furniture of the family at Ipswich. It is not far from the form of those now used in our houses being stuffed in the back & seat as our Settees & Sophias are only open between the seat & Back. It appears to be worn, but not the parts separated. The flowers are raised upon the ground not unlike our carpets. It is 5 feet long & 4 high & above 2 feet wide, in the frame. It has six feet, two in the middle, strongly framed together with rounds across & in front. The work is nowhere depressed by use but has its proper swell in the back & seat & it is nowhere rent or injuried by the want of any part. The sacking in the back & under the seat is sound. I was not a little pleased with the possession & I found no rival claims. All were willing honourably to dispose of to a friend of the family what they feared to destroy & dared not disgrace.[34]

Although individuals associated with the couch’s history were named in this account, no one attempted to trace its provenance before the 1970s. Throughout most of the nineteenth century, the couch was assigned a vague history of having belonged to Huguenot refugees; a nineteenth-century label glued on the proper left rear post recites this idea. The “Dr. Appleton” of Bentley’s diary entry was the Reverend Dr. Nathaniel Appleton (1693–1784), pastor of the Cambridge Congregational Church from 1717 to 1779 and father of John Appleton (1739–1817), from whose estate Bentley acquired the couch. “Dr. Holyoke” was Dr. Edward Augustus Holyoke (1728–1829), son of Edward Holyoke (1689–1769), president of Harvard College from 1737 until his death. Dr. Appleton’s probate inventory, dated April 8, 1784, confirms that the couch, described as a “Turkey wrought settee” and valued at £1.10, stood in his “great Room” or parlor. Investigation of Appleton’s relatives revealed that he received the couch from the estate of his uncle, John Leverett (1662–1724), president of Harvard College from 1707 until his death. Leverett’s probate inventory included “12 Small Turky Chairs 36s./7 Camblit Do. 40s./Six three back chairs 12s.” totaling £4.8 and “12 Large Turky Chairs & Couch £9. Lanthorn 7s. Lumber in ye Garrets 10s.” totaling £9.17.[35]

In 1697, Leverett married Margaret (Rogers) Berry (1664–1720), widow of the wealthy Boston merchant Thomas Berry (1665–1696). Berry’s probate inventory, taken in Boston on November 20, 1697, listed “Furniture of the Hall I dozn. Turkey worke Chairs 30/. Each,” “6 old-fashioned Turkey workt chairs. a[t] 9/ and Turkey Work for a Couch 16/” in the “Dining Room Chamber,” and “6 Turkey chairs a[t] 10/. Each” in the “Porch Chamber.” The inventories for Berry and Leverett demonstrate that the couch frame for the Turkey-work had not been made at the time of the former’s death. Most likely Leverett had a frame made for the covers soon after he married Berry’s widow in 1697. Further, the descriptions of the sets of Turkey-work chairs in Berry’s inventory compare favorably with the sets in Leverett’s inventory. The expensive set of twelve chairs corresponds to twelve large chairs in Leverett’s inventory, and the two sets of six old-fashioned chairs are probably the twelve small chairs in Leverett’s inventory. Further, the terminology indicates that “Large” chairs were high-backed, while “Small” chairs were low-backed and somewhat out of fashion. Because the large chairs and the couch were listed together in 1724, they appear to have been regarded as being en suite.[36]

Some of the damage to the seat covers of the Leverett couch undoubtedly occurred after the newly founded Essex Historical Society in Salem acquired that object from Dr. Bentley’s estate via Appleton’s heirs. During the nineteenth century, strict curatorial protocols did not exist, and many visitors to the organization probably sat on the couch in order to contemplate Puritan times. Nevertheless, the condition of the couch is extraordinary, and it is the most intact Turkey-work seating in both England and America.

On the two Cromwellian side chairs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the selvedges of the covers are turned under to reduce their width. On the couch, they seem to have been laid flat. The seat is deflected downward on either side of the central medial brace, and the selvedges on the sides may have been forced upwards to some extent. The back has experienced downward shifting of the stuffing, creating a defective bulge traditionally referred to in upholsterer’s parlance as a “bustle” (not to be confused with the intentional stitched panel in the lower back of some Victorian sofas, also known as a bustle). Obviously these covers have experienced what English textile scholars refer to as “perished” black pile; that is, the iron based dye used to color the black pile eventually disintegrated the wool, hence the effect of raised flowers noted by Reverend Bentley.

On the Leverett couch and three of the Turkey-work side chairs, the seat covers were cut and brought around the posts in what the authors call “flags”; the covers were given two cuts to create flaps, which were then turned under and drawn around the posts (figs. 24, 25). On surviving leather side chairs, this technique is not employed, but it does appear on the Endicott armchair (fig. 17). On leather side chairs, the covers are cut at a forty-five degree angle, turned under, and then drawn straight down next to the posts. Perhaps flags usually were associated with textile covers.

The fringe and galloon have largely fallen away, but many substantial fragments remain, captured by brass nails (fig. 26). They appear to be what the British call “parti-colored” (multicolored), and the wools look to be the same used to make the knotted pile. Some sequences of the headings and galloon suggest a checkered pattern. This is much the same treatment seen on the Hampton Court chair at Temple Newsam House, Leeds, although no way exists of ascertaining if the Leverett couch fringe was netted or simply straight. Galloon fragments are found all around the back panel.[37]

The back panel is applied in an unusual manner (fig. 28). The ends are drawn around the posts, rolled up, and tacked to the posts in the outside back. Obviously the covers were too wide for the frame, which should have been about six inches longer, as in the case of the couch illustrated in figure 35. On the other hand, the extraordinary bulk of the stuffing on the seat may have required the narrower width for the Leverett frame, as mandated by the upholsterer involved.

The foundation upholstery of the couch departs remarkably from the webbing, sacking, and stuffing of the side chairs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The large seat area has ten webbing strips fore and aft and three webbing strips side to side (fig. 30). The sacking in the seat and the back is heavier in weight than that of the chairs. The grass stuffing is particularly thick on the seat—approximately five inches—because the central medial strut is a wide, flat board and the stuffing was intended to protect the sitter from feeling the strut. A heretofore unrecognized feature is a large stitched edge roll, on and immediately behind the front seat rail (fig. 31). The rear edge of the edge roll cover was secured with a row of rough stitches visible underneath the seat (fig. 30). The edge roll itself is only visible on the left side of the seat where the covers have partially pulled away. It appears that the fore edge of the roll cover was secured with twines, which were tacked to the upper front surface of the seat rail. The two side chairs do not have edge rolls, but bundles of grass do lie completely across the front, the sides, and the rear on the outer margins to provide much the same stability. As it is, the Leverett couch has the earliest surviving edge roll in Anglo-American upholstery. Similar edge rolls may exist undetected in surviving seating in England, although this is not certain. Presumably royal and noble seating was stuffed with superior curled horsehair, and other ways of stitching the horsehair in place may have been employed. Better quality chairs in England dating after 1670 have extensive large edge rolls on all four sides of the seat, probably stuffed with hair; the edge rolls created a well that is stuffed with more hair, creating a domical loft.[38]

The Leverett couch had wings or falls hinged on the arms, supported by toothed iron arcs passing through keepers of some sort mounted on the outside back of the rear posts. Previous scholars have examined the arms and rear posts for evidence of those fixtures, and a brief description of them is in Benno M. Forman’s American Seating Furniture 1630–1730. Detailed photos of the evidence have not been published before now. Many modern reproductions of the Leverett couch have attached wings or falls to the arms with snipe hinges (or “cotter pin” hinges, in twentieth-century popular parlance). The evidence on the Leverett couch suggests a much sturdier arrangement (figs. 32-34). The hinge sites indicate that rivets passed through the arms to secure dovetail-style leaf hinges; the leaves attached to the wings may have been dovetailed as well, but they may have been straps, Ls, or some other type. The sawn-off ends of the rivets are visible on the outsides of both arms, and a round, wrought head is visible on the inside of the left arm. This demonstrates that the rivets were inserted from the inside, passed through holes in the leaves of the hinges, and then were peined on the outside to secure the hinges. This is certainly a hefty arrangement for a minor fixture, and the makers must have supposed that the wings would receive active use. Most likely the hinges were table hinges, of the sort intended for the leaves of large oval leaf examples.[39]

Neatly executed mortises for box mechanisms of some sort are on the rear surfaces of the Leverett couch’s posts (fig. 28). These mortises also have thin, subsidiary mortises below them. This configuration suggests that the boxes held a spring mechanism to secure the arcs at a given setting, which is a surprisingly elaborate arrangement. Most English leather couches with wings or falls have simple, U-shaped staples to secure the arcs. The couch illustrated in figure 35 has roughly chopped mortises, with rivet holes above and below the mortises. This evidence suggests a simpler mechanism, perhaps just a U-shaped yoke with reinforcements.

In general, the frames of the Leverett couch and the example illustrated in figure 35 are similar. Both have four corner posts and a subsidiary leg in front. Some English couches have three back posts, occasionally associated with the same number of front legs. Others have two rear posts and four front legs. Designs varied to accommodate the amount of stress the frame was thought to receive. The Leverett couch and the example illustrated in figure 35 are not wide enough to seat three occupants, so they were thought of as double chairs. Both couches have fore-and-aft struts in the center of the seat (figs. 30, 35).

The couch illustrated in figure 35 experienced a twentieth-century restoration of the top two inches of the rear post tops and the top of the vertical strut in the back frame. However, the sites for the keepers on the rear posts are evident. Here the frame maker roughly chopped mortises for the box, flanked above and below by rivets (fig. 36). The arms have holes for rivets (fig. 37).

One surviving one-ended couch, probably the earliest known American example, dates from the very end of the Boston Cromwellian tradition (fig. 38). The frame has acorn-shaped finials on the rear posts, much like those on three related side chairs. The framing is very much like those of so-called “William and Mary” and “Queen Anne” couches (see fig. 5 in Robert Trent’s article in this volume). Conceptually the seat frame is two fronts of a Cromwellian couch set back-to-back, with the addition of a back frame at one end; the center legs on the long, side rails are tenoned into the underside of the continuous rail. Rabbets in the seat rails and a sway brace set between the long rails indicate that the couch originally had a sacking bottom—three or four flaps tacked in the rabbets and laced into tension by cords passing through hand-stitched grommets in the inner edges. (This is similar to the sacking bottoms used in bedsteads. The idea that bedsteads with pins on the rails were simply strained with ropes is probably not true; in many such bedsteads, ropes may have passed back and forth to grommets sewn in the outer edges of a sacking panel.) In the usual manner, the couch seat would have received a stitched hair mattress or a down- or wool-stuffed pad, and the adjustable back would have had a down- or wool-stuffed pillow or perhaps a round bolster and a square down pillow. The present treatment with leather covers on the restored swiveling back frame and a stitched hair mattress on the seat is modern. Most likely the swiveling frame would have been upholstered in the same textile as the covers of the mattress or squab and the bolster and pillow, if any were provided. Slightly later turned couches from Pennsylvania sometimes have webbed and sacked seats with leather covers and may have been used with textile cushions.

Conclusion

Barring the kind of shipping records available for later Boston seating, the histories of ownership of Cromwellian chairs here assigned to Boston manufacture offer the most important evidence for their having been made in a central place and then exported. The histories include ownership or recovery in Essex County, Massachusetts; Newport and Providence in Rhode Island; Hartford, Fairfield, and Harwinton in Connecticut; and New Brunswick, New Jersey. As noted above, only the Leverett couch has a clear history of ownership in Boston and Cambridge, Massachusetts. Uniformity of design, execution, and upholstery also suggest that the chairs all originated in one place. And that place, in Benno M. Forman’s thinking and ours was Boston.

In fact, while Boston dominated the colonial carrying trade in the English colonies of the Atlantic from 1660 to 1720, it is remarkable that more upholstered seating in the low-backed design is not known from New York. The Dutch-looking leather chair illustrated in figure 39 is extraordinarily important in this regard, because it is squarely in the Dutch metropolitan tradition and must have been made in New York, perhaps during the period of Dutch rule, about 1650 to 1670, when the city was known as Nieuw Amsterdam. It was owned by John Amsden (1686–1742) of Deerfield, but obviously was purchased by his parents or grandparents.

The Amsden chair follows a typical Dutch design made in metropolitan centers in the Netherlands. The chair is smaller in plan and has a higher seat than most contemporaneous English and Boston chairs; Boston seats are roughly 18 1/8" wide, 15" deep, and 20" high (top of seat frame), whereas the Amsden chair’s seat is 17 3/8" wide, 15" deep, and is 21" high (originally higher due to at least 1" loss to the front legs and rear posts). The frame of the Amsden chair has relatively little layback, and it has prominent great heels to prevent it from oversetting backwards. The surviving upholstery of the seat is built around a 2 x 2 webbing strip pattern placed close to the center of the seat so that the stitching of the leather passes through three of the strips (fig. 40). The stitched panel is bigger in both dimensions than the panels on Boston versions, which means that the chair has a smaller stuffed area around the stitched panel. Boston chairs typically have a stitched panel 4 7/8" wide and 3 1/8" deep, whereas the Amsden chair has a panel 5 9/16" wide and 3 3/4" deep (fig. 41). The intention of this might have been to create a bigger well to keep cushions on the seat. The low front stretcher was intended to serve as a footrest when the chair was not drawn up to a table with stretchers.[40]

These differences might seem negligible, but in the North Atlantic community, the various national types of upholstered seating were studied quite closely. Most New Englanders—at least those with resources and residing in a port city—knew what a Spanish, French, or Dutch leather chair looked like, and how could it be otherwise? And the covers and trims were also scrutinized, given the high cost of the materials and labor involved. Having said all that, it is remarkable that the Boston Cromwellian frame remained so consistent over forty years of production. The next phases of chair design display far more variations and options over the 1705–1740 span of the style.

For assistance with this article, the authors thank Gavin Ashworth, Luke Beckerdite, Dennis Carr, John Childs, Carolyn Cruthirds, Andrew Davis, Alyce Englund, Suzanne Flynt, Nonie Gadsden, John Stuart Gordon, Joseph P. Gromacki, Erik Gronning, Rebecca Piccirillo, Alexandra Kirtley, Joshua W. Lane, Marie McFarland, Laura Parrish, Susan Newton, Timothy Neumann, Heather Porter, Jim Schneck, Jeanne Solensky, Kasey Stewart, Anne H. and Frederick Vogel III, and David F. Wood. Travel expenses and accommodations were provided by funds presented to Winterthur Museum by Anne H. and Frederick Vogel III.