Tall clock with case by John Janvier Sr., Elkton, Maryland, and movement by Benjamin Chandlee, Nottingham, Pennsylvania, 1770-1774. Mahogany with tulip poplar and hard pine. H. 101 1/2", W. 21 1/4", D. 11 1/8". (Courtesy, Biggs Museum of American Art; photo, Carson Zullinger.)

Rear view, showing the stacked backboards of the tall clock illustrated in fig. 1.

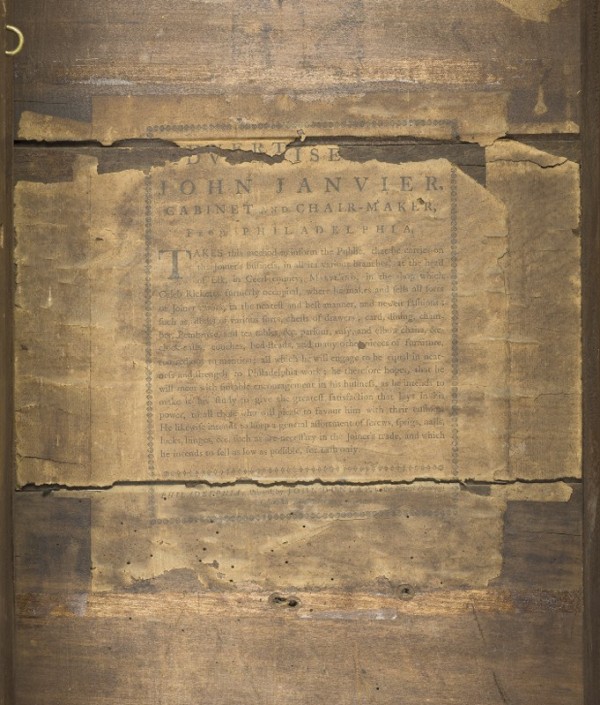

Detail of the printed label of John Janvier pasted on the inside backboards of the tall clock illustrated in fig. 1.

Card table, probably New York City, 1795–1805. Mahogany with unidentified secondary woods. H. 28 1/2", W. 33 3/4", D. 18" (closed). (Courtesy, New-York Historical Society.)

Detail showing the conventional horizontal lamination of the rail of a Rhode Island card table, 1795–1805. (Courtesy, Stanley Weiss Collection; photo, Marc Beaulac.)

Detail of the vertical laminations forming the rail of the card table illustrated in fig. 4.

Tall clock with case by Thomas Janvier, Odessa, Delaware, and movement by Duncan Beard and Christopher Weaver, Odessa, Delaware, 1792. Mahogany with yellow pine and tulip poplar. H. 100", W. 21 3/8", D. 10 3/4". (Courtesy, Biggs Museum of American Art; photo, Carson Zullinger.) The scrolls and feet are replacements, and the pediment has been extended 1 3/8 inches to accommodate a replacement blind fretwork.

Tall clock with case by James McDowell and Daniel McDowell, Smyrna, Delaware, 1793–1800. Mahogany with unidentified secondary woods. H. 96 1/2", W. 19 3/4", D. 10 1/4". (Private collection, photograph courtesy of Israel Sack, Inc. Archives, Yale University Art Gallery.)

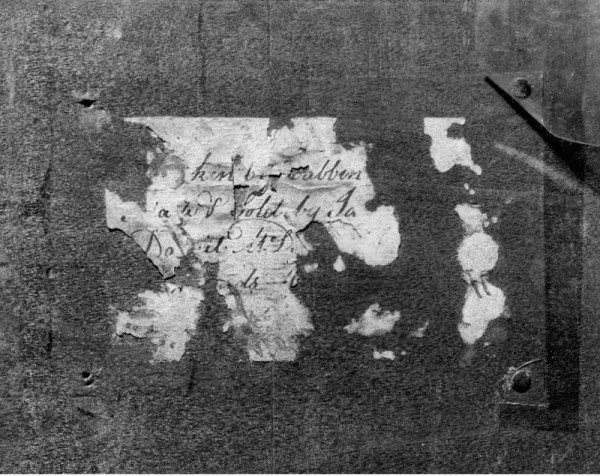

Detail of the label pasted to a horizontally grained backboard on the tall clock illustrated in fig. 8.

Tall clock with case by John Janvier Sr., Odessa, Delaware, 1795. Walnut with white cedar and tulip poplar. H. 94 3/4", W. 21 1/8", D. 11 3/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

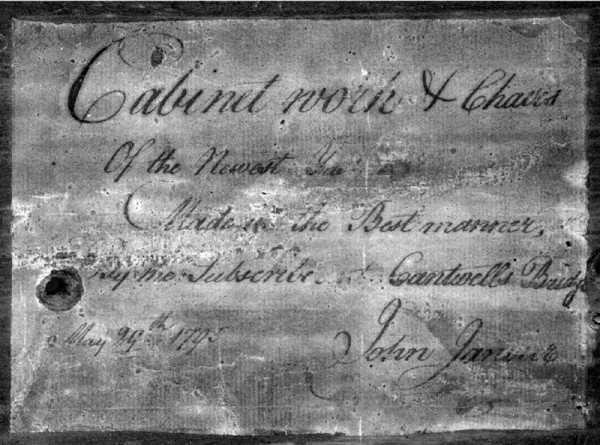

Detail of the handwritten label pasted to the inside center of backboards on the tall clock illustrated in fig. 10.

Tall clock with case by John Janvier Sr., Odessa, Delaware, 1779, movement by Duncan Beard. Mahogany with unidentified secondary woods. H. 97", W. 21", D. 11" (approximate). (Courtesy, Leslie Miller and Richard Worley.)

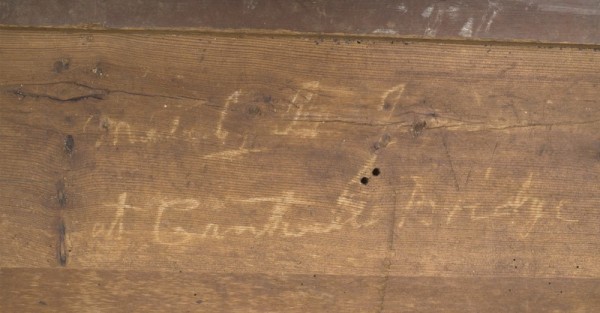

Detail showing the inscription inside the waist door of the tall clock illustrated in fig. 12.

Chest of drawers by John Janvier Jr., Odessa, Delaware, probably 1806. Mahogany with cherry, tulip poplar, yellow pine, and white cedar. H. 33 5/8", W. 39 1/8", D. 22". (Courtesy, Historic Odessa Foundation; photo, Carson Zullinger.)

Detail of the inscription on the outside case bottom of the chest illustrated in fig. 14.

Chest of drawers by Peregrine Janvier, Odessa, Delaware, 1804. Mahogany with tulip poplar, yellow pine, and white cedar. H. 34 3/4", W. 41 1/4", D. 22 3/4". (Courtesy, Biggs Museum of American Art; photo, Carson Zullinger.)

Detail of the half-dovetail groove cut into the top of the chest illustrated in fig. 14.

Detail of the interior glue blocks securing the top of the chest illustrated in fig. 14.

Detail of the glue blocks along the underside edges of a drawer from the chest illustrated in fig. 14.

Chest of drawers by John Macdonough, Odessa, Delaware, 1807. Mahogany with tulip poplar, white cedar, and oak. H. 34 7/8", W. 41", D. 23 1/2". (Courtesy, Biggs Museum of American Art; photo, Carson Zullinger.)

Detail of one of the half-dovetail grooves and wooden plugs in the top of the chest illustrated in fig. 20.

Sideboard by John Janvier Jr., Odessa, Delaware, 1812. Mahogany with tulip poplar, oak, and white pine or white cedar. H. 52 1/4", W. 72 3/8", D. 29 7/8". (Private collection; photo, Carson Zullinger.)

Table, eastern Pennsylvania, 1740–1770. Walnut with tulip poplar. H. 29", W. 41", D. 26 1/2". (Courtesy, Monmouth County Historical Association, Freehold, N.J.; photo, McKay Imaging.)

Detail of the dovetailed cleat and pins (missing from holes) securing the top of the table illustrated in fig. 23.

Chest of drawers, Odessa, Delaware, 1790–1810. Cherry with tulip poplar. H. 36 1/8", W. 40 1/4", D. 22 3/4". (Courtesy, Biggs Museum of American Art; photo, Carson Zullinger.)

Detail of the inscription on the outside bottom of the chest illustrated in fig. 25.

Detail of the foot construction of the chest illustrated in fig. 25. The rounded glue block is a later addition.

Detail of the construction of the left rear foot of the chest illustrated in fig. 25.

When Delaware cabinetmaker John Janvier (1749–1801) made and labeled the mahogany tall clock case illustrated in figure 1, he used many horizontal backboards—one stacked atop another—instead of a single, vertically oriented backboard (fig. 2). Nailed within rabbets cut into the back edges of the case sides, these slats have tongue-and-groove edges on the long (horizontal) sides, which help protect the case interior from dirt and dust (which eventually fouled delicate clock movements, requiring them to be disassembled and cleaned) as each slat expands and contracts with changes in humidity. Because the long side boards of the case stop at the base of the bonnet, therefore ending a rabbeted place to attach stacked boards, the backboard behind the bonnet has vertically oriented grain in the conventional manner. Stacked-backboard construction is significantly more time-consuming than using a single, vertically oriented board. Its value lies in the comparatively greater stability it represents. As time demonstrates among surviving clock cases, those single, long boards might shrink across the grain, an action that either pulls the rear case sides together or pulls the backboard nails from their holes. More serious in some instances, these long backboards have warped, creating a twist that forces the clock case out of square. In contrast, if the stacked boards shrink or warp, which is less likely given their shorter dimensions, the overall effect on the clock case is negligible.

John Janvier’s Life and Circumstances

As is the case with most other early cabinetmakers, relatively little is known about Janvier’s life, and nothing in the historical record suggests anything particularly noteworthy or unusual. Judging from the usual paper trail of real estate, civil, and probate records, he led a successful life, but his accomplishments paralleled, without demonstrably exceeding, those of others in his region and time. Born in 1749, John was the fifth of six sons (only four of whom outlived childhood) of Francis Janvier (1705–1761), a first-generation Delawarean, and his second wife, Sarah de Haes. Francis may have done carpentry, but particulars of his trade are uncertain. He was one of six sons and four daughters born to French Huguenot immigrant Thomas (1664–1728), who arrived in Philadelphia in 1686 and settled several years later in New Castle, Delaware, the principal town of the colony, located some forty miles downstream from Philadelphia.[1]

Essential details of John’s biography come from his printed maker’s label, known only by its single use in this clock and affixed to the inside on the back (fig. 3). In the wordy text, Janvier advertises himself as “cabinet and chair-maker, from Philadelphia,” who “carries on the Joiner’s business in all its various branches, at the head of Elk in Cecil county, MARYLAND. In the shop which Caleb Ricketts formerly occupied, . . . he makes and sells all sorts of Joiner’s work, in the neatest and best manner, and newest fashions . . . equal in neatness and strength to Philadelphia work.” Janvier must have completed his Philadelphia apprenticeship by 1770, when he turned twenty-one. Shortly thereafter, presumably, he left for the headwaters of the Chesapeake Bay to begin his furniture-making career. John Dunlap (1747–1812) of Philadelphia, famous for printing the first copies of the Declaration of Independence, printed Janvier’s label and, like him, had only recently commenced his career. Unlike Dunlap, who at age nineteen assumed his uncle William Dunlap’s printing business in Philadelphia, Janvier seems to have had no promising pathways to shop ownership there, short of marrying a well-connected woman. More affordable real estate likely attracted him to Head of Elk. This destination lay another twenty-five miles or so beyond New Castle on a southwestern vector from Philadelphia toward Baltimore. Head of Elk and the northern waters of the Chesapeake were very much part of a geographic community united by economics and religion—primarily shipment of wheat and other grains grown in Lancaster County situated to the north and Presbyterianism, which Janvier practiced.[2]

The departing Caleb Ricketts, whose biography is similarly sketchy, seems to have left his shop for better business prospects. Beginning in 1768, he had provided the vestry of St. Paul’s Church, near Centreville, Maryland, along the eastern shore of the Chesapeake, with carpentry services and, subsequently, building plans for a new church. Although the new house of worship seems not to have been completed, Ricketts’s multiyear engagement likely caused him to move south, closer to this employment. By January 1772 he owned property in Chestertown, about thirty-five miles (or a full day’s travel) southwest of Head of Elk and ten miles north of present-day Centreville.[3]

Janvier’s time in Head of Elk was limited. Evidence does not detail when he relocated to Odessa (then variously called Cantwell’s Bridge or Appoquinimink), but he married Elizabeth March (1752–c. 1810) of St. George’s Hundred, Delaware, on August 6, 1772. St. George’s Hundred, one of many political subdivisions in Delaware called “Hundreds” and created by William Penn for tax purposes, lay between Head of Elk and Odessa, a small community on the Delaware River. By 1775 the couple had built their house in Odessa, according to an inscription discovered on an old floorboard, and had their first child, Francis de Haes (1775–1824). John Janvier’s name was listed on St. George’s Hundred tax rolls in 1777.[4]

For the most part, Janvier’s life and work in Odessa followed broadly practiced norms. From today’s perspective, furniture making in the eighteenth century was remarkably consistent and stable in design, materials, and construction. Apprenticeships instructed boys through repetition. Employment of and for journeymen favored and depended on predictable outcomes. And shop production followed widely accepted notions of what a final product should be—from the perspectives of both workers and customers. Perusal of furniture makers’ account books and other written evidence reveals remarkably little descriptive detail about the manufactured goods because expected outcomes were well defined and regularly realized. The individual early American furniture maker strived to make his products better than the next, but not necessarily different.

All of these circumstances and the broader socioeconomic practices that flourished with them produced regional profiles of furniture making on which fundamental understandings of early American furniture today are based. Regionalism expressed itself through design conventions, predictable choices of materials, especially secondary woods, and construction practices. Styles (as defined today) lasted for decades or generations. Consistency dominated, although furniture historians routinely seek and explore changes, notably in design, which imparts a seemingly dynamic quality to the study of early furniture.

Innovation goes against the grain of eighteenth-century craft. It distinguishes itself as a feature or quality that lies outside the inevitable variations of expression present in individual handwork. Its existence, consequently, is intentional on the part of the maker. Consider the highly original structural feature found in a small group of New York federal card tables (fig. 4). It derived from the challenge of making geometrically shaped table frames from straight pieces of wood—a material that might split, warp, or otherwise deform over time if bent or cut from the solid to a curve. Specifically, the New York card-table maker wanted a frame of rounded rails or sides. Normally, the wood used for the rounded table rails was cut into horizontal strips, one to two inches high, and glued atop one another (totaling from three to six layers or laminations) to build a structurally stable wall capable of being cut into the desired curve (fig. 5). Careful attention to grain orientation of each layer, laid in alternating directions (called cross-graining today), ensured that natural expansion and contraction of the wood across the grain due to humidity changes would not alter the overall shape of the rail. This construction technique also avoided the possibility of deep splits along the grain from longer-term seasoning of large, solid blocks of wood.

The maker of the New York card table illustrated in figure 4 (and others) addressed the needs of curved table rails by laminating multiple thin sheets of wood vertically rather than horizontally, resulting in thin rails rather than the one-inch thickness of horizontally laminated rails (fig. 6). Because of their durable construction, these lightweight, vertically laminated rails did not move or split. Although they represented an elegant solution that showed considerable knowledge of materials, they did not inspire broader use at the time, perhaps because the additional labor required to manufacture the multiple-ply boards outweighed the benefit. Two generations later, in 1858, John Henry Belter patented a modest variation on this technique to protect his use of it in the curved backs of his seating furniture. Eventually, the technique spread to become the many types of plywood forms ubiquitous throughout the twentieth century.[5]

Janvier as Innovator

Janvier was solely responsible for two innovations in tall clock cases. A third innovation occurred in construction of a four-drawer chest, signed “J Janvier,” but the inscription does not distinguish between him and his second son and namesake, John (1777-1850), one of several Janvier sons and apprentices trained by the elder John. When John died in 1801, his son John, aged twenty-four, no longer needed to distinguish himself by adding “Jr.” or “II” to his name. Thus, when John Jr. signed a sideboard in 1812, he identified it as “Made by John Janvier at Cantwell’s Bridge New Castle County / Delaware 1812.” A second four-drawer chest, also bearing a “J Janvier” signature embodies yet another innovation. This level of curiosity and the resulting changes in furniture-making practices on the part of preindustrial artisans is exceptional. As the leading furniture maker in his small community, the elder Janvier influenced others to use his innovations, notably those who worked in his shop, but also others, some of whom worked seventy-five or more miles away.[6]

The impact of stacked backboards in tall clock cases may seem marginal to modern eyes, but other eighteenth-century furniture makers took notice and copied the technique. Among Janvier’s close associates, his nephew Thomas signed and dated a tall clock on May 28, 1792, with stacked backboards (fig. 7). Thomas (1772–1852), having turned twenty, likely had just completed his apprenticeship with his uncle. Another tall clock of very similar design and also with stacked backboards bears the fragmentary manuscript label of James McDowell (act. 1785–1836) and Daniel McDowell (act. c. 1793–1830), who identified their place of business as Duck Creek Crossroads, now Smyrna, about twenty miles south of Cantwell’s Bridge (figs. 8, 9). The relationship between James and Daniel is not known, but they were likely brothers or similarly close relatives. Interestingly, John Sr. used a similar handwritten label on a walnut tall clock case (figs. 10, 11) in 1795, suggesting the undated McDowell clock case may have been made closer to Daniel’s earliest working date of 1793 than to the time of his move to Dover, Delaware, in circa 1809.[7]

By the close of the eighteenth century, makers in several more distant communities to the northwest employed stacked backboards. Lancaster City and County in Pennsylvania, seventy-five miles or a long two-day trip, was one such place. For example, fourteen of thirty-three tall clocks by several makers in the Rock Ford Plantation collection are made that way. Other clock cases with stacked backboards were made in central and eastern Pennsylvania counties. Central New Jersey examples include at least one labeled by John Scudder (act. 1793–1815) of New Brunswick or Flemington and early nineteenth-century examples by Edward Hudson of Mount Holly, John Whitehead of Haddonfield, and William J. Leslie of Trenton. Arthur Johnston, working from 1804 to 1814 in Hagerstown, Maryland, many miles west of Cantwell’s Bridge, used stacked backboards. Other makers in Maryland and elsewhere may have used this construction, but tracking diffusion of the technique is difficult because it is seldom, if ever, noted in modern furniture publications.[8]

These geographic patterns of use seem to be linked to regular inter-regional contact based on trade and, to a lesser extent, religious and social ties. In the case of Lancaster County, shipments of grain traveled south to the Chesapeake Bay and the Delaware River. More general trade (and ideas) moved via the Delaware River to Trenton and then overland northeast toward New York and accessed central and northern New Jersey. No instance of stacked backboards is known in Philadelphia-made cases, where Janvier apprenticed. Nor does any other use of this technique anywhere predate Janvier’s Head of Elk clock. The inescapable conclusion is that Janvier, trained in conventional construction techniques, did something completely different shortly after he went out on his own.

Janvier’s second clock-related innovation involved the long doors in the waist that opened to reveal the pendulum and weights. Pre-Revolutionary American clock case doors were made of solid wood. They had lip-molded edges that overlapped the door opening, thus creating a seal against dirt and dust, as well as hiding unsightly open edges. The more embellished case doors had shaped tops—half-rounds, rounds flanked by ogee curves, or some similarly complex line—and the best were also richly grained. Janvier’s Head-of-Elk clock-case door displayed some of these features, establishing the overall decorative ambition of the clock as modest but not memorable. By 1779, however, Janvier had introduced a new kind of door. Fortunately for furniture historians, he signed the work, “Made at Cantwells Bridge / Delaware / 1779” (figs. 12, 13). Its door exhibited a level of decoration—namely, scalloping around all sides—that signaled an expensive piece of furniture. Some clock historians have likened this decoration to that of tall clock cases made in Bristol, England, but the scalloped lines of the Janvier doors contain three or four times the number of ogees as the Bristol doors, producing a far more agitated line. As conservator Christopher Storb observed, its rhythm may resemble more closely the scalloped tea-table tops that Janvier likely saw when he was an apprentice in Philadelphia. Only one of the dozen or so Janvier scalloped door cases has longer, Bristol-style scallops, and that case was likely made circa 1800. Any similarity between the one Janvier clock and contemporary Bristol work appears to be happenstance.[9]

Beyond visual qualities, the door represents another construction innovation. In the 1779 clock, Janvier replaced the solid wood door with a framed door, covered with a highly figured facing about one-quarter-inch thick. Unlike solid doors, this door did not split, shrink, or warp. It closed and locked neatly in the door frame regardless of humidity changes or the passage of time. As with stacked backboards, similarly constructed framed doors that Janvier might have imitated have not come to light. His framed doors were made many years before federal sideboard tops were constructed in a similar way. These likewise were framed with thin mahogany boards well supported from underneath to avoid the distortions and splitting along the grain that might compromise solid board tops.

Construction of framed tall clock doors incorporated several refinements, befitting Janvier’s accomplished woodworking skills. The mortise-and-tenon corners of the mahogany rails and stiles met at miters on the outside of the door. A medial rail dovetailed into the stiles prevented any bowing of the strips of wood that formed the long vertical sides. Thick white cedar boards filled the vacant centers, adding stability and creating a continuous plane on which an elaborately scalloped panel made of attractively figured walnut or mahogany was glued. Cockbeading finished the outside edges of the door. The scalloped panel—a more complex series of ogees and in-curved corners than in the base panel—lay atop the framing rails and stiles and integrated all of the door parts into a single, coordinated decorative statement. Interestingly, many federal clock-case makers working throughout the United States applied veneers and complex decoration to the outsides of solid waist doors.

The decorative qualities of Janvier’s door panels became a highly recognizable feature of his work and that of his immediate followers, although the 1795 clock case (see fig. 10) documents his occasional manufacture of the cheaper, simpler, solid-door alternative. The attractive visual properties of the framed doors need to be seen as inseparable from Janvier’s ambition to build long-term stability into his best work. Of interest in understanding his work routines, the scalloping differs in measurements from one door to the next, indicating that not only did he not use patterns or templates, but he also did not stockpile parts. Instead, each composition was laid out individually after the particular door had been framed. Although he made several tall clock cases, each was a new venture, tied to past work only by his consistent approaches to design and construction.

The seven tall clocks reliably documented by signatures and other evidence to Janvier, his nephew Thomas, and the partnership of James McDowell and Daniel McDowell, all of whom likely apprenticed in Janvier’s shop, are strikingly similar in appearance and construction. Overall consistency among them makes authorship of individual cases difficult to discern without specifying evidence. That same degree of shop consistency applies to chests of drawers. The four-drawer chest illustrated in figures 14 and 15, signed “Made by John Janvier / Cantwells Bridge” in chalk across the outside case bottom, cannot be assigned to John Sr. or Jr. by construction characteristics; instead, that determination needs independent evidence of when the chest was made. Style analysis might suggest that it predates 1790 or so and is therefore the work of the elder Janvier, but there are too many instances of stylistic features persisting beyond modern style periods to accept such generalizations. To the point, a second, faint inscription on the lower drawer bottom of the Janvier chest appears to read, “Recd Febr 21st 1806 of Mr. Nathan Woodruff / The sum of £ 2 : 7 : 6 [illegible].” Although possibly recording subsequent resale of the chest decades after it was made, this inscription more likely documents its original sale in 1806, making it the work of John Jr. Close comparison of construction details yields no significant differences from another chest (fig. 16), which is inscribed, “MADE August 1804 / By Peregrine Janvier / Appoquinimink / for / for [sic] Mr. David Wilson,” on the outside bottom boards of the second drawer from the bottom. Peregrine (1781–1865) was John senior’s third son.[10]

The importance of the two chests lies in the construction of their tops, each of which attaches with a sliding dovetail (fig. 17). Half-dovetail-shaped tongues cut into the top edges of the chest sides fit into similarly shaped grooves cut into the underside of the top. The grooves cut through the back edge allow the top board to slide into place from the front of the carcass toward the back. Both Janviers then neatly plugged the open grooves in the overhang of the top along the back edge. Had a plug not broken away on the John junior chest, this construction feature might have gone unnoticed. Inside the case, each top is secured in the same fashion (fig. 18). Glue blocks laid end to end run along the corners where the chest sides meet the top. A long strip of wood fills the corner across the back. Nails through the outside top edge of the backboard hold it fast to this long glue block.

Furniture historians will recognize sliding-dovetail top construction as common in furniture made in the latter half of the eighteenth century in Boston and other eastern Massachusetts shops and communities. Some Newport chests used related dovetail-shaped keys (similar in shape to inset “butterfly” repairs) to secure the mahogany top board to the framing of the subtop. Other Newport chests and those made everywhere else in America used glue blocks and/or screws in screw pockets to secure the top. In all other respects, the Janvier chests display classic Philadelphia regional design and construction features, such as the engaged quarter columns on the one and the shape of the ogee feet on both. Inside, each chest has full dustboards, white cedar drawer bottoms with grain oriented front to back, and tulip poplar drawer sides. Hard pine secondary wood is used elsewhere. Characteristic of the elder Janvier’s work, glue blocks along the underside of the drawer fronts and drawer sides reinforce the drawer bottoms, which slide in grooves cut along the bottoms of the drawer sides (fig. 19). The Peregrine chest has mahogany veneered drawer fronts on hard pine, whereas the John junior chest is veneered on cherry drawer fronts, an unusual choice in Delaware or Philadelphia work.[11]

The slide-on top is unknown in Philadelphia work and in the broader mid-Atlantic region, which raises obvious questions of how and why either Janvier came to use it. Some might speculate that one of the Janviers saw this construction on a Boston-area chest of drawers, perhaps when it was shipped up the Delaware River on its way to a Philadelphia purchaser. Such an explanation is possible but not likely. Shipment of Boston case furniture to Philadelphia at this time was incidental at best, to say nothing of the circumstances required to put Janvier, working in a small village along the Delaware River, in front of such a chest. More reasonable from a historical perspective is that one of the Janvier sons devised this top construction independently. Whether that individual was John junior or Peregrine is impossible to say, because the dated and surviving chests may not have been the first to employ sliding tops. Once in play, the idea then passed to others working in the Janvier shop. One such individual was John Macdonough (b. 1789), who signed his bowfront chest on the underside of the top drawer, “Made by John Macdonough Cantwell’s Bridge / 1807” (figs. 20, 21). He also plugged the backs of the grooves and used the same arrangement of interior glue blocks. Another construction feature that ties Macdonough’s work to the Janvier shop is his use of oak secondary wood for the drawer fronts, a very unusual—but not innovative—practice evident in an 1812 sideboard by John Jr. (fig. 22).[12]

Why the Janviers made the chests illustrated in figures 14 and 16 with a sliding-dovetail attachment for the tops has no clear answer. Use of sliding dovetails to secure tops was a well-known technique among Pennsylvania-German furniture makers, whose work any of the Janviers and others in the Odessa shop may have seen at various times and places. Pennsylvania-German “pin-top” tables, typically made of walnut, had multiple-board tops that slid in half-dovetail tongues cut into cleats, which were then attached to the table frame with removable pins (figs. 23, 24). This construction allowed the boards to expand and contract across the grain with changes in humidity, thereby preventing splitting or movement of any fasteners. However, if Janvier intended to minimize damage to his chest top by allowing it to slide with changes in humidity, he defeated that possibility by attaching multiple glue blocks along the inside corners formed by the chest sides and top, which prevented movement (see fig. 18). Janvier’s efforts to construct stable and durable case furniture may have inspired him to select cherry for the mahogany-veneered drawer fronts, rather than pine, as was common.

An Unsuccessful Innovation

One last piece of furniture, a cherry chest of four graduated drawers, merits attention for its construction innovation (figs. 25, 26). Authorship of this chest derives from a chalk inscription, “J Janvier,” on the underside of the case. Its notable innovation lies in the fabrication of its bracket feet. Late eighteenth-century bracket feet were almost always made in one of two ways. In both techniques, outside primary-wood facings for each of the two sides were mitered in the corner and glued around a square or quarter-round block of wood that bore the weight of the chest (fig. 27). The difference between the two techniques lay in how the foot was attached to the case. One type was glued directly on the underside while the unfinished carcass lay upside down. Alternatively, the facings and wood block were first attached to a horizontal board or plate, creating a complete foot unit that could be made on the bench. It was then attached to the underside of the chest. In both cases, smaller glue blocks often reinforced the basic foot construction.

In the cherry chest, all of the bracket feet look the same as conventionally constructed bracket feet from the outside, but their construction differs in key respects (fig. 28). Instead of a large weight-bearing block, a narrow strip of wood reinforces the joint of the facings, which are somewhat thinner than most. Grooves cut into the tops of the facings accommodated complementary tongues cut into the edges of a squared, horizontal board or plate, also relatively thin, that completed the foot unit. The plate was then glued to the underside of the chest. Three of the four bracket feet have had larger, weight-bearing glue blocks installed in place of the narrow strips, thereby substantially reinforcing the foot. Miscellaneous other repairs indicate that these feet did not withstand usage well. Only the left rear foot survived unchanged. Furniture makers in Hartford, Connecticut, made similarly engineered feet, except they were made initially of significantly heavier components that have not failed. This basic difference between the two foot innovations suggests that no personal ties bridged their geographic separation.[13]

That no other case furniture with this foot variation has come to light measures the limited life and influence of innovations with little or no merit. This one survival cannot serve as an indicator of how often early furniture makers experimented and failed, but it is a reminder that, in their premodern world of conformity, some individuals might pursue alternatives. This survival also raises the question of its relationship to the Janviers and their shop. Does the existence of this foot design suggest the possibility of other Janvier innovations that failed? Three enduring innovations credited to a single shop is already an extraordinary number.

Comparing the foot innovation to other Janvier work raises a question of consistency, itself an important value in the output of this shop. All of the innovations, especially those concerning tall clocks, pursued long-term durability and stability of the object in question. Other conventional aspects of their cabinetmaking, notably the consistent surplus of glue blocks, reinforced those long-term objectives. In contrast, the thin—and ultimately flimsy—nature of the foot variation clashes. Many other features of the chest are at odds with Janvier cabinetry, which call into question the chalk “J Janvier” signature (compare figs. 15, 26). Nothing suggests that the signature is not authentic, but reading it as “Janvier” is the only piece of evidence that links this chest to John Sr. or Jr. Otherwise, almost every construction detail differs: drawer dovetails differ; drawer bottoms are tulip poplar rather than white cedar and are not secured by glue blocks; dustboards are fielded with the fielded surface upward; the chest top is blind-dovetailed to the sides; and foot facing profiles differ. Removing this innovative piece of furniture from the shop output does not alter the Janvier profile as remarkably innovative. The three (successful) improvements demonstrate that this shop surpassed John Sr.’s advertised claim of work to be “equal in neatness and strength to Philadelphia work.”

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For assistance with this article, the author thanks Ryan Grover, Christopher Storb, Debbie Buckson, Michael Podmanizcky, Richard Cooch, Frank Levy, Steven Petrucelli, Lauri Perkins, Gary Sullivan, Kim Jovinelli, Sarah Drennen, David Sperling, Joe Hammond, and Julia Hofer.

L. Corwin Sharp, “The Janvier Family of Cabinetmakers of Odessa, Delaware” (master’s thesis, University of Delaware, 1980), pp. 4–5. Francis’s first father-in-law, John Calvert, was a wheelwright in New Castle.

Dunlap assumed his uncle William’s printing business in 1766. He first advertised what he called the “Newest Printing Office in Market Street” in the February 9, 1769, issue of the Pennsylvania Gazette.

Frederic Emory, Queen Anne’s County, Maryland: Its Early History and Development (Baltimore: Maryland Historical Society, 1950), pp. 169, 171–72, 213–14; Charles G. Dorman, Delaware Cabinetmakers and Allied Artisans, 1655–1855 (Wilmington: Historical Society of Delaware, 1960), p. 43.

Susan Johnson and Horace L. Hotchkiss Jr., “Odessa Cabinetmaker’s Stable Restored,” Winterthur Newsletter (October 1980), pp. 2–3. Sharp, “The Janvier Family,” p. 10. The place-names referenced the Appoquinimink River and the bridge over it. The town was renamed in 1855.

Philip D. Zimmerman, “New York Card Tables, 1800–1825,” American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2005), pp. 120–21. Not recognizing its earlier use, Clare Vincent speculates that Belter brought “the plywood type of construction of furniture to the United States,” in “John Henry Belter’s Patent Parlour Furniture,” Furniture History 3 (1967): 98. Eighteenth-century English furniture construction used three-ply laminations in tea table galleries and some chair splats. The author thanks Adam Bowett for these observations. An early description of the technique occurs as “press-work, of recent introduction,” in George Dodd, Dictionary of Manufactures, Mining, Machinery, and the Industrial Arts (New York: D. Van Nostrand, 1869), p. 414.

Deborah D. Waters, Plain and Ornamental: Delaware Furniture, 1740–1890 (Wilmington: Historical Society of Delaware, 1984), no. 37.

Philip D. Zimmerman, Delaware Clocks (Dover, Del.: Biggs Museum, 2006), pp. 42–43. These two McDowells signed other furniture, including a chest by James, which is also signed by Thomas Stevenson (1787–1865), also of Smyrna. James’s sons William (act. c. 1815–1829) and James Jr. (act. c. 1820–1860), both of Smyrna, were also cabinetmakers.

The author thanks Sarah Drennen, Curator, Rock Ford Plantation. Walter Hamilton Van Hoesen, Crafts and Craftsmen of New Jersey (Rutherford, N.J.: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1973), p. 53. Thanks to Frank Levy, Steven Petrucelli, and Gary Sullivan for identifying these clocks. James Biser Whisker, Daniel David Hartzler, and Steven P. Petrucelli, Maryland Clockmakers (Cranbury, N.J.: Adams Brown, 1996), p. 179, fig. 139, illustrates stacked backboards in a clock by Arthur Johnston of Hagerstown, active 1804–1814.

Robert E. Booth Jr. and Edward F. LaFond Jr. describe the 1779 Janvier clock as having a “Bristol-style scalloped door” in “It’s about Time,” Philadelphia Antiques Show 2000 (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Antiques Show, April 8–12, 2000), p. 50. For examples of Bristol cases, see Tom Robinson, The Longcase Clock (Woodbridge, U.K.: Antique Collectors’ Club, 1981), pp. 330, 332, figs. 10/72, 10/73. Zimmerman, Delaware Clocks, p. 33, fig. 16.

Wilson (1743–1820) lived a few houses away from the Janvier shop on Main Street in Odessa.

Philip Zea, “Construction Methods and Materials,” in Brock Jobe and Myrna Kaye, New England Furniture: The Colonial Era (Boston: Houghton Mifflin for the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, 1984), p. 85. Typically, Massachusetts construction did not entail plugging the open groove. Margaretta Markle Lovell, “Boston Blockfront Furniture,” in Boston Furniture of the Eighteenth Century (Boston: Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 1974), p. 84; Patricia E. Kane, Art & Industry in Early America: Rhode Island Furniture, 1650–1830 (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Art Gallery, 2016) pp. 286–87. The only other instance of mahogany veneer on black cherry known to the author is the unusual high chest of drawers signed “J Claypoole” and dated 1743 at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (1998-78-1a–c). Thanks to Chris Storb for this observation.

Philip D. Zimmerman et al., Sewell C. Biggs Museum of American Art: A Catalogue, 2 vols. (Dover, Del.: Biggs Museum, 2002), 1: no. 68.

Alice K. Kugelman, Thomas P. Kugelman, and Robert Lionetti, “Hartford Case Furniture Study Survey, III: The Connecticut Valley Oxbow Chest,” Maine Antique Digest (October 1995): 1–4C, especially “The Quadrant Base” on 3-C.