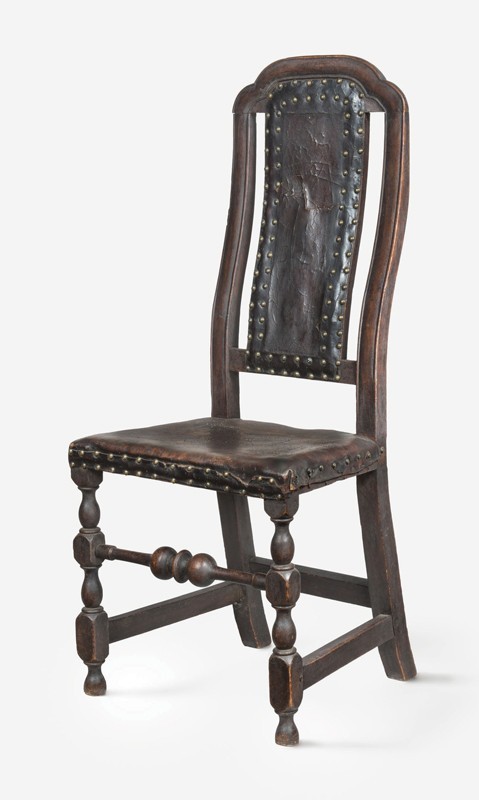

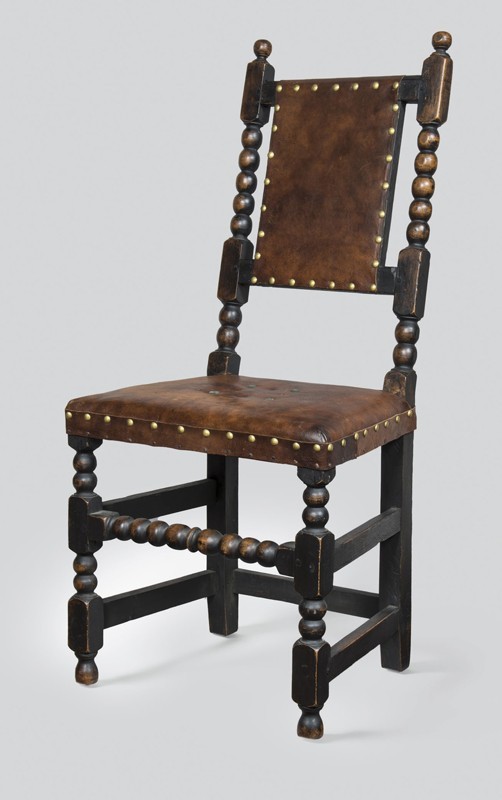

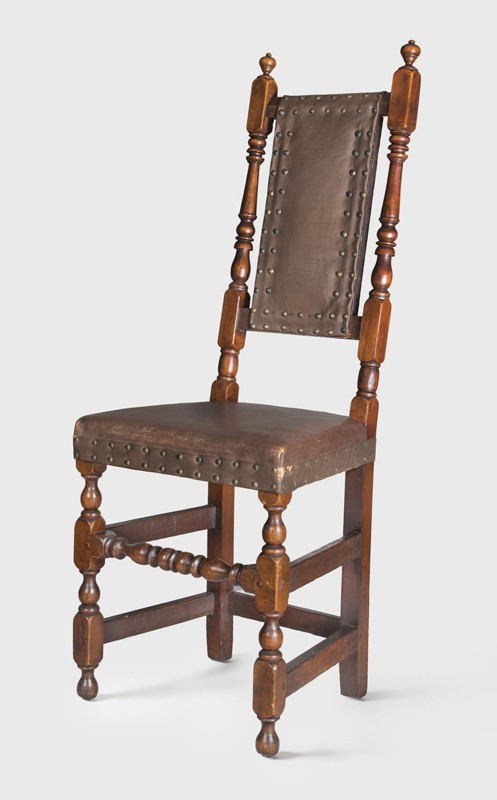

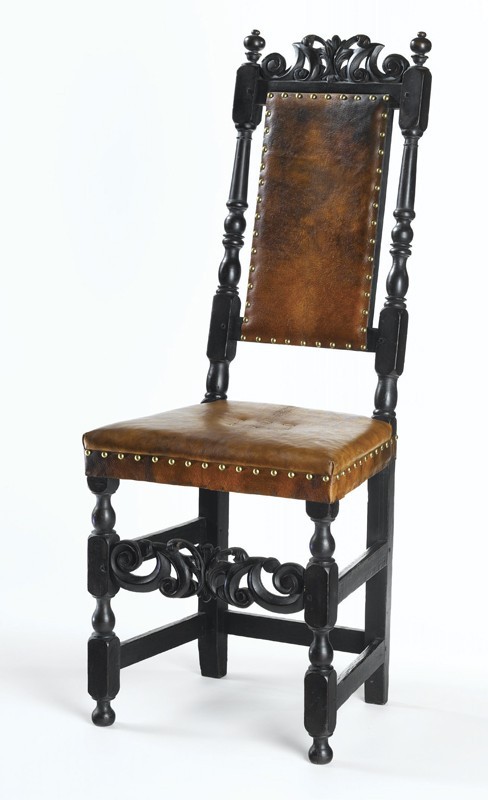

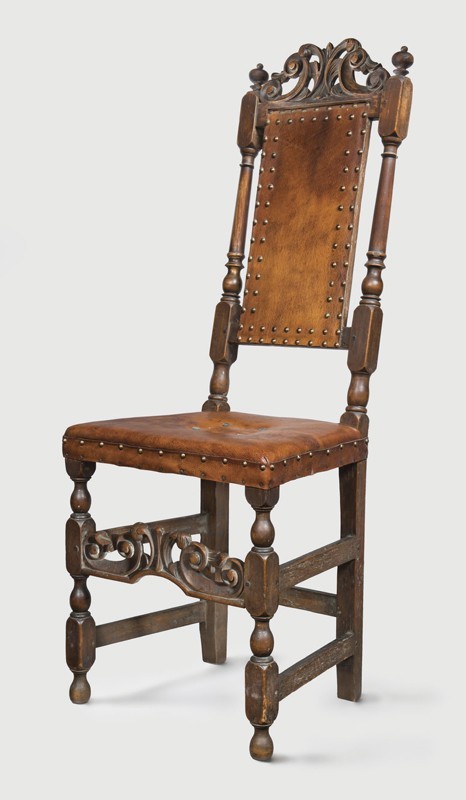

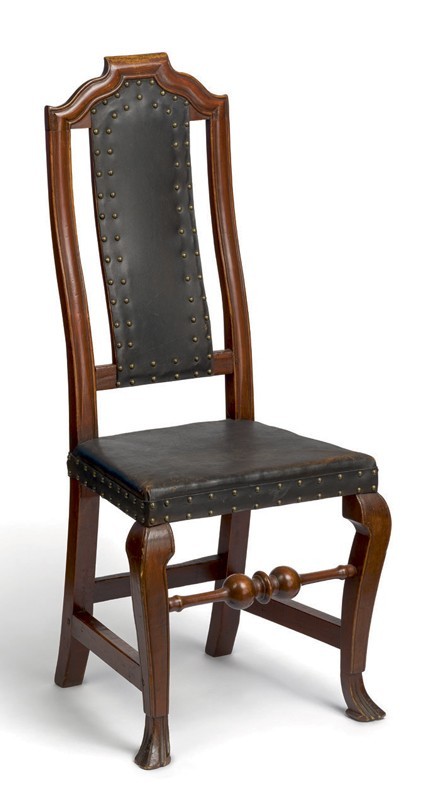

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1720–1750. Maple and oak; original leather upholstery. H. 43 1/2", W. 18 1/4", D. 15". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

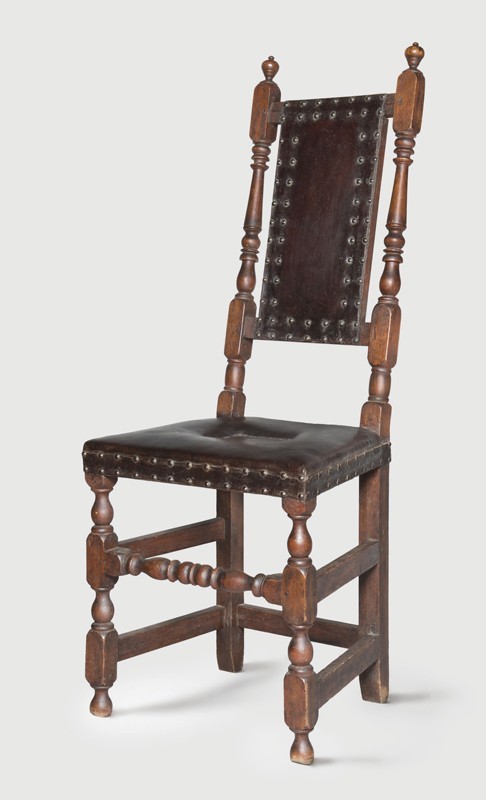

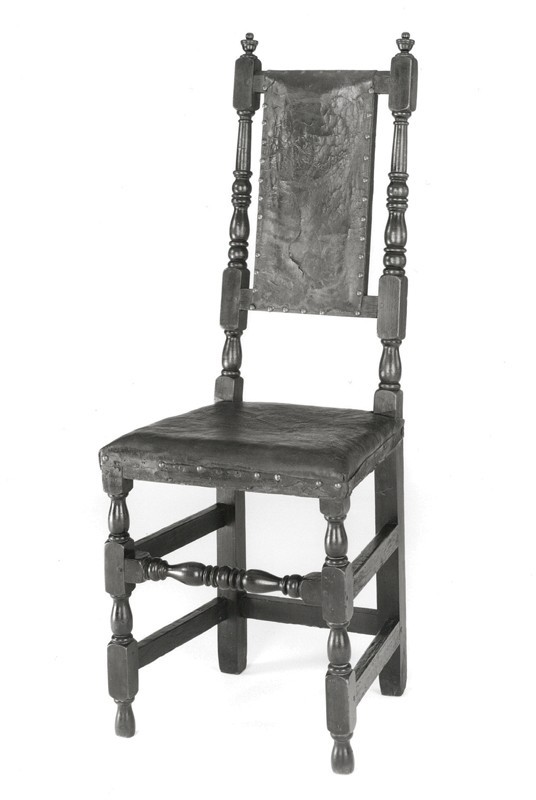

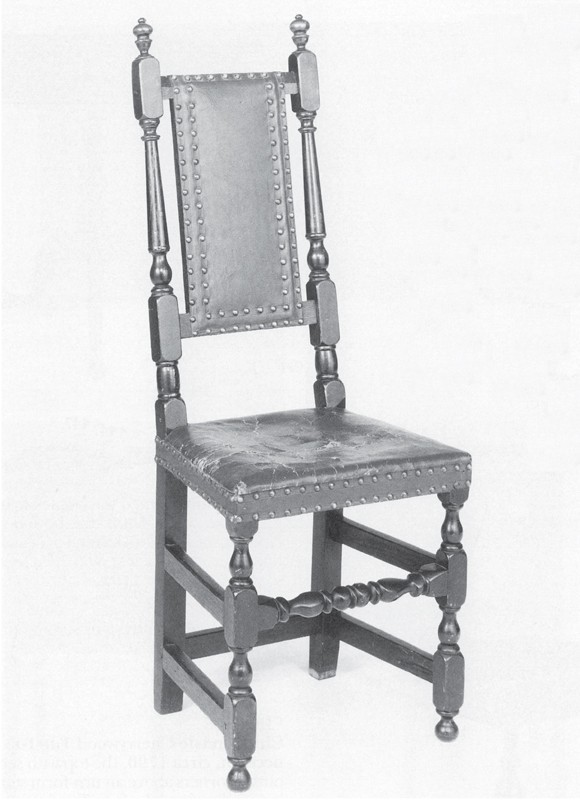

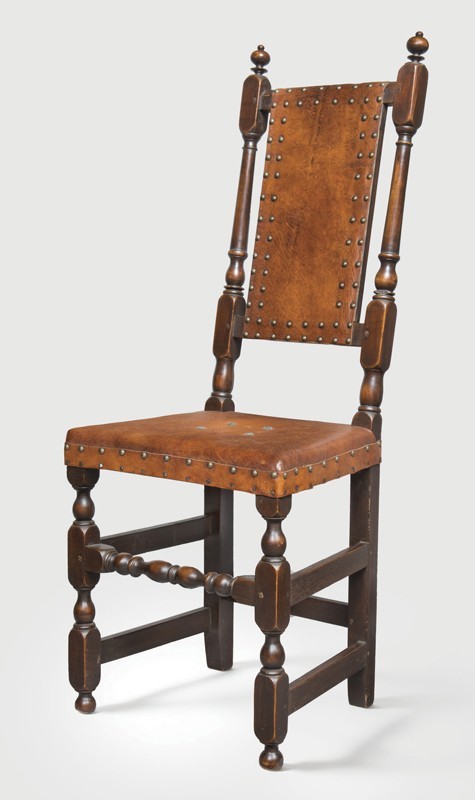

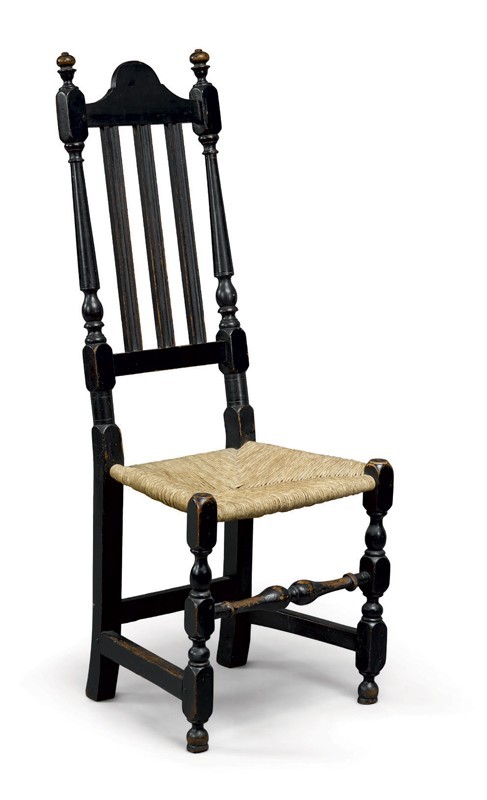

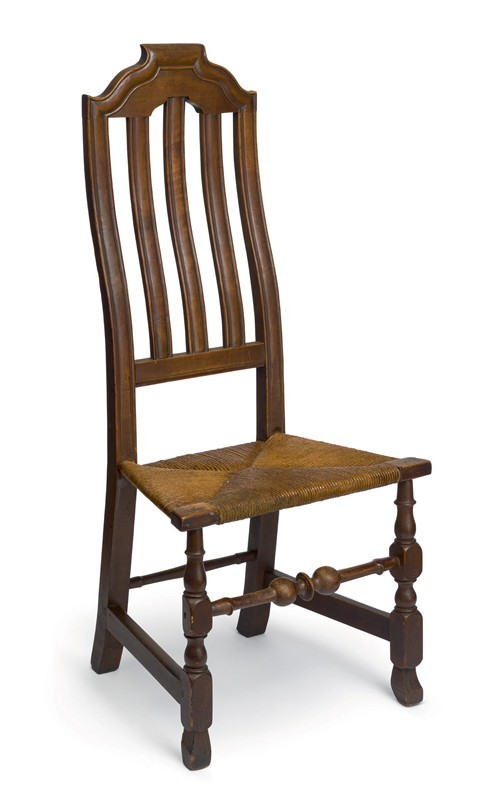

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1685–1705. Maple and oak. H. 48", W. 20 1/4", D. 22". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This is the first American example of a slot placed in the crest to pass through the leather upholstery.

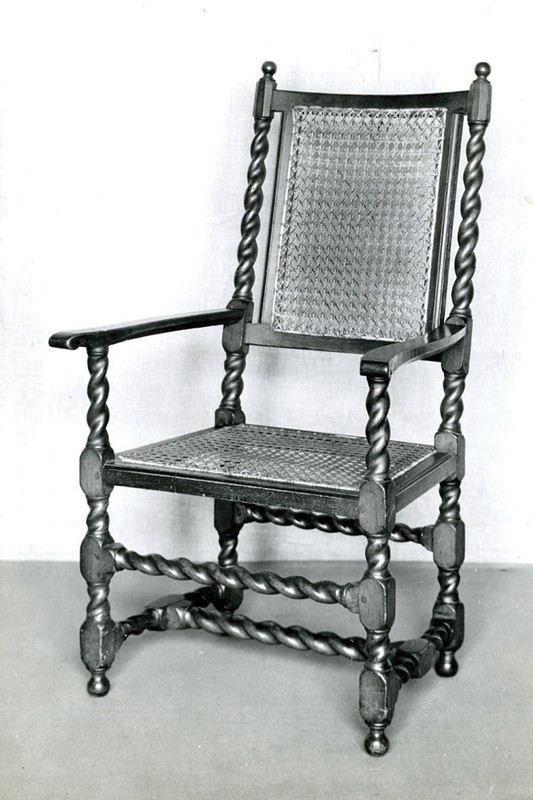

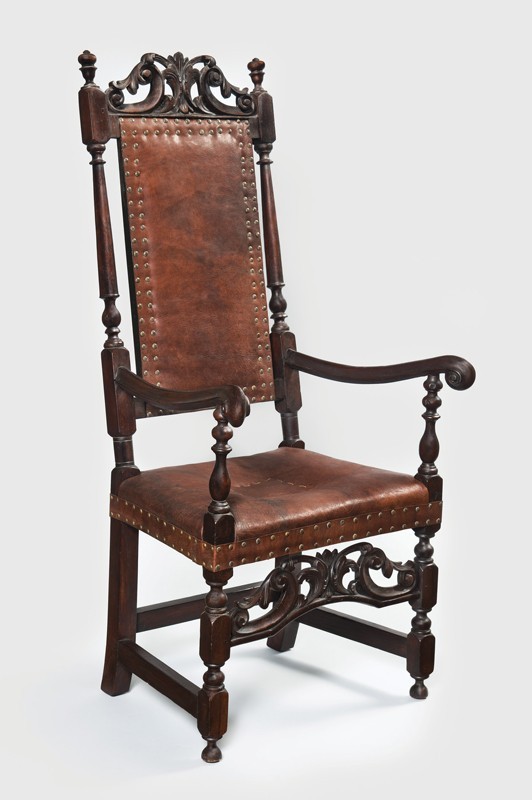

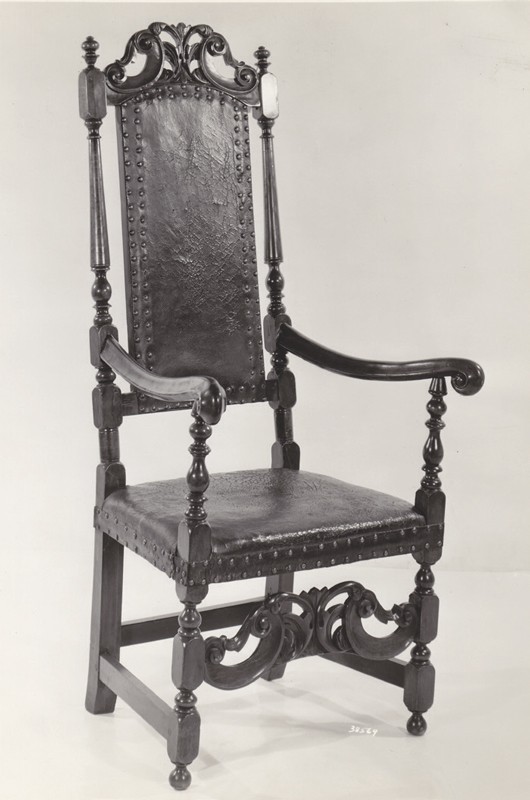

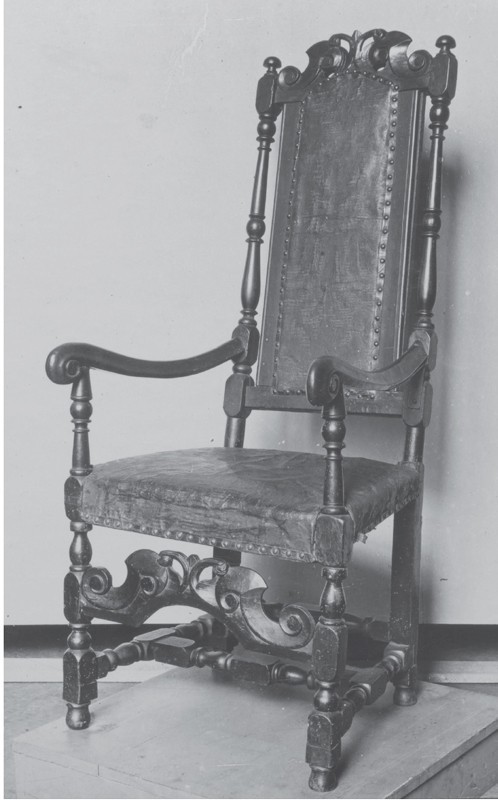

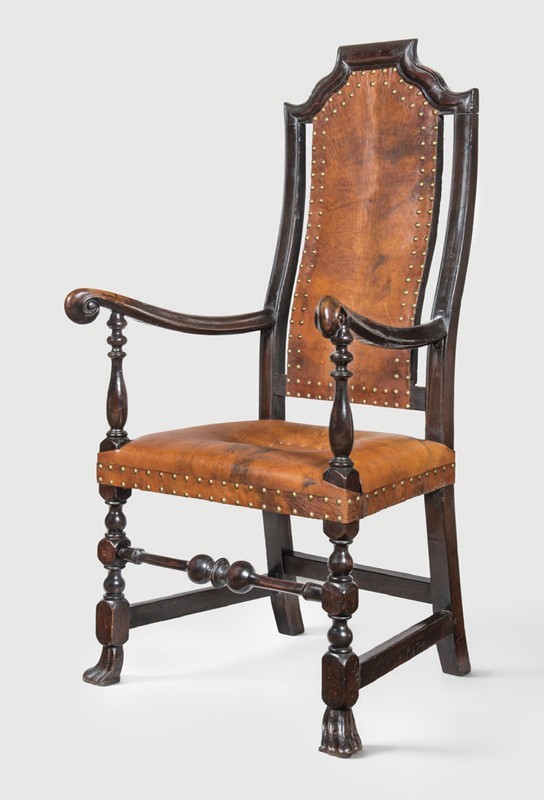

Armchair, probably London, 1685–1700. Woods and dimensions not recorded. (Photo, Symonds Collection, Decorative Arts Photographic Collection, Winterthur Library.) The back rails of this chair have a noticeable curve or hollow.

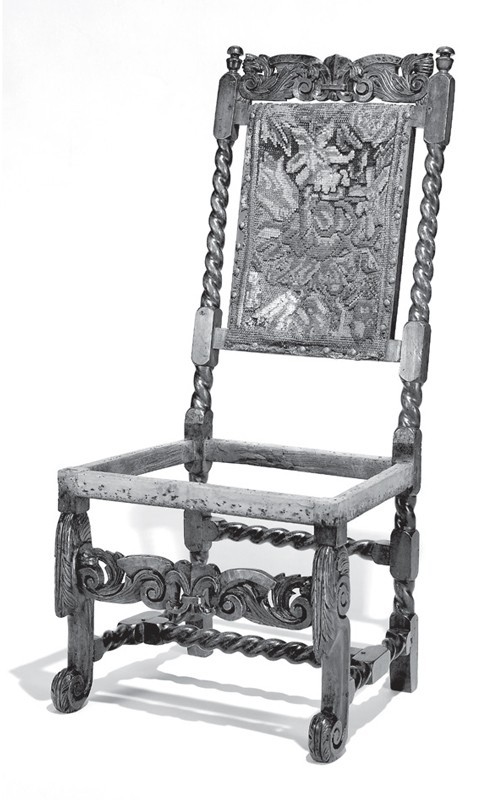

Side chair, probably London, 1685–1700. Beech; original turkeywork upholstery. H. 48 5/8". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, gift of Mrs. Winthrop Sargent in memory of her husband Jun, 17.1629.)

Side chair, probably London, 1685–1700. Woods and dimensions not recorded; original leather upholstery. (Photo, Symonds Collection, Decorative Arts Photographic Collection, Winterthur Library.) The crest and lower back rails have a noticeable curve or hollow. The turnings on the back posts closely relate to those present on group B chairs (fig. 13).

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1685–1705. Maple and oak. H. 42", W. 20", D. 20 1/2". (Courtesy, Anne H. and Frederick Vogel III Collection for the Philadelphia Museum of Art, acc. no. 188-2016-8.) The gilding was added in the nineteenth century. This chair is the only example of the group with a single side stretcher.

Couch, Boston, Massachusetts, 1685–1705. Maple and oak. H. 38", W. 21 1/2", D. 84". (Courtesy, Anne H. and Frederick Vogel III Collection for the Philadelphia Museum of Art, acc. no. 188-2016-9.) This is the only ball-turned couch known, and it may have been made en suite with the side chair illustrated in fig. 6.

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1685–1705. Maple and oak. H. 41 3/8", W. 19 1/2", D. 15". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The back dimensions are the same as those of low-back chairs, but the orientation is vertical rather than horizontal. The nailing pattern, with brass-headed nails at the top and wrought iron tacks at the bottom, is commonly found on Cromwellian chairs.

Side chair, England, 1675–1695. Oak. H. 43", W. 21 1/2". (Courtesy, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, W.29-1928.) The feet are missing.

Armchair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1685–1705. Maple and oak. H. 48 3/4", W. 23 1/2", D. 18". (Private collection; photo, Jim Wildeman.) The arms of this chair are carved with leafage and relate to those on contemporaneous English chairs like the one shown in fig. 12. The finials are identical to those on the side chair illustrated in fig. 8. The feet are restored.

Armchair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1695–1710. Maple and oak; original leather upholstery. H. 47 1/2", W. 23 3/4", D. 17 3/4". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Arthur Tracy Cabot Fund, 1971.624.) The iron rods in the arms are a nineteenth-century addition, and the feet are missing but would have been like those on the side chair illustrated in fig. 16.

Armchair, probably London, 1685–1700. Woods and dimensions not recorded. (Photo, Symonds Collection, Decorative Arts Photographic Collection, Winterthur Library.)

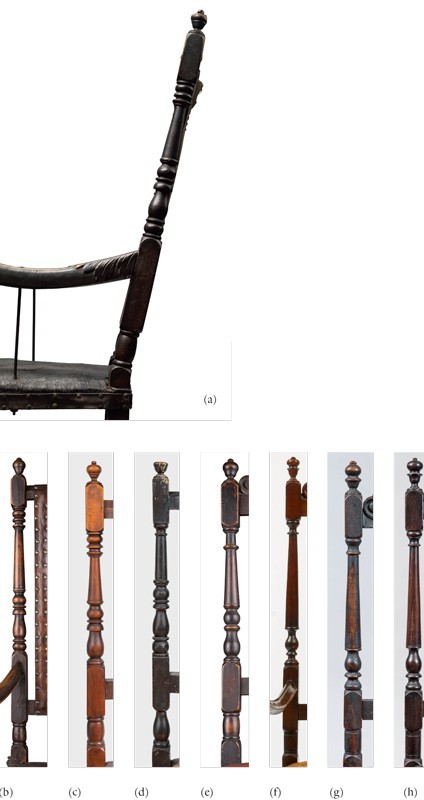

Composite illustration showing the rear post of the

(a) Group B armchair with foliate carved arms illustrated in fig. 11;

(b) Group B armchair illustrated in fig 18;

(c) Group B side chair illustrated in fig. 17;

(d) Group B side chair illustrated in fig. 24;

(e) Group C side chair illustrated in fig. 31;

(f) Group D armchair illustrated in fig. 45;

(g) Group E side chair illustrated in fig. 56;

(h) Group F side chair illustrated in fig. 69.

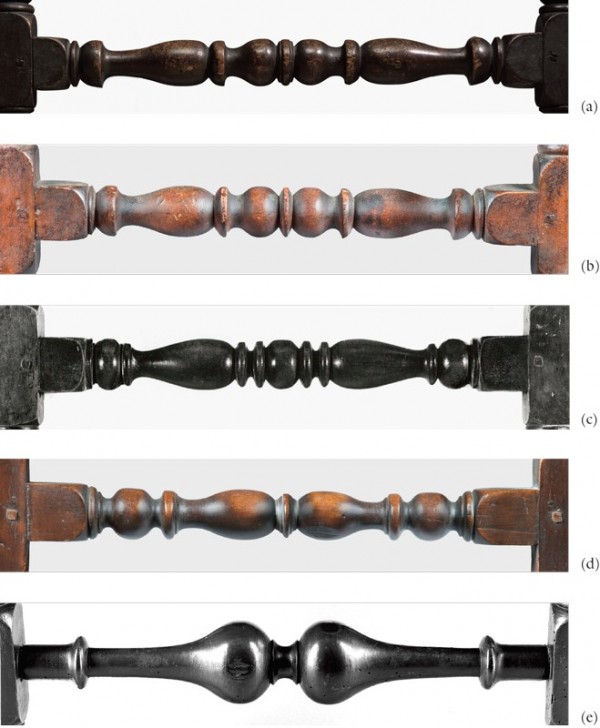

Composite illustration showing the front stretchers of the

(a) Group B armchair with foliate carved arms illustrated in fig. 11;

(b) Group B side chair illustrated in fig. 16;

(c) Group B side chair illustrated in fig. 23;

(d) New York side chair illustrated in fig. 51;

(e) Group E side chair illustrated in fig. 72.

Composite illustration showing the arm support of the

(a) Group A armchair with foliate carved arms illustrated in fig. 10;

(b) Group B armchair with foliate carved arms illustrated in fig. 11;

(c) Group B armchair with scroll-carved arms illustrated in fig. 18;

(d) Group D armchair illustrated in fig. 53;

(e) Group E armchair illustrated in fig. 88;

(f) Group E armchair illustrated in fig. 60;

(g) Group F armchair illustrated in fig. 112;

(h) Group C armchair illustrated in fig. 38 (arm scroll terminals replaced).

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1695–1710. Maple and oak. H. 46 5/8", W. 18 1/4", D. 15". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This side chair has rear posts identical to those of the chairs illustrated in figs. 11, 17, 18, and 20, absent the ring and compressed ball directly below the lowermost baluster turning.

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1695–1710. Maple and oak. H. 43 3/8", W. 17 5/8", D. 14 3/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, bequest of H. F. du Pont; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Armchair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1695–1710. Maple and oak; original leather upholstery on the seat. H. 51 3/4", W. 24 1/2", D. 17 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Jim Wildeman.)

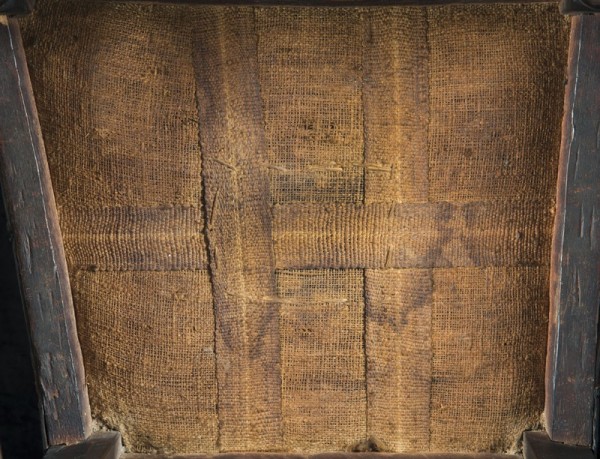

Detail of the stretchers and the original webbing and sackcloth under-upholstery of the armchair illustrated in fig. 18. Three webbing strips are placed front to back and are woven between the two side-to-side strips. This orientation of webbing was the standard arrangement used by Boston and New York upholsterers. Uncommon are the outer front-to-back strips angled at the same degree as the side seat rails.

Armchair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1695–1710. Maple and oak. H. 51", W. 23", D. 17". (Courtesy, Historic Huguenot Street, New Paltz, N.Y., gift of Alice Hasbrouck, 1999.7240.01.) The arms are replaced, and the feet are missing. This chair descended through the Hardenbergh family and was owned originally by Johannes Hardenbergh (ca. 1670–1745) of Ulster County, New York.

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1695–1710. Maple and oak. H. 44 5/8", W. 18 5/8", D. 16 5/8". (Courtesy, Saint Louis Art Museum, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Edward J. Nusrala, 249:1989.) The barrel turning above the seat is scored at its widest point. The urn finials diverge from the standard “muffin” variety.

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1695–1710. Maple. H. 45 5/8", W. 18 1/8", D. 15 1/4". (Courtesy, Milwaukee Art Museum, Layton Art Collection, L1982.116; photo, Richard Eells.) This chair descended in the family of artist Pieter Vanderlyn (ca. 1687–1778) of Kingston, New York. Pieter immigrated to New York City from the Netherlands in 1718. His arrival date suggests he acquired the chair from an earlier owner. The top and lower back rail have a noticeable curve or hollow.

Side chair, probably Boston, Massachusetts, 1700–1720. Maple and oak; original leather upholstery. H. 47 3/4", W. 18 1/2", D. 18 3/4". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chair’s leather trim strip was secured with brass nails along the top edge and wrought iron tacks along the lower edge.

Side chair, probably Boston, Massachusetts, 1695–1710. Maple and oak. H. 43 5/8", W. 17 5/8", D. 14 3/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, bequest of H. F. du Pont; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

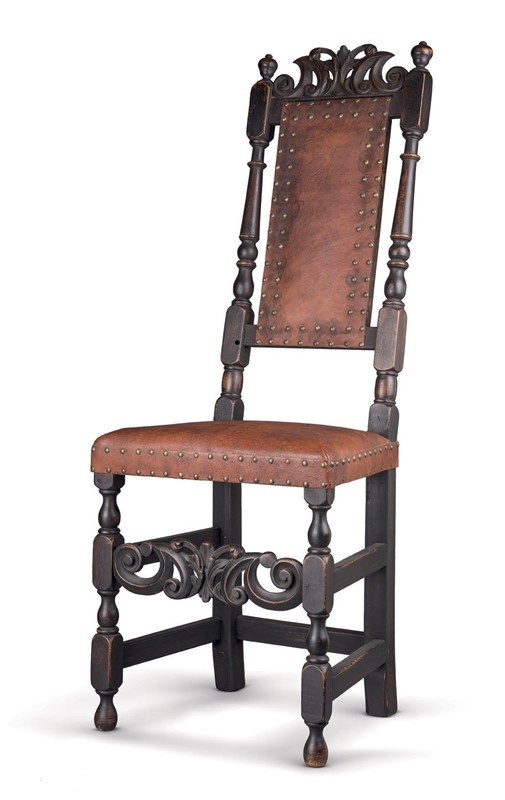

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1695–1710. Maple and oak. H. 48 1/4", W. 17 3/8", D. 12 7/8". (Private collection; photo, Nathan Liverant and Son.) This is the only group B side chair with a carved crest rail and stretcher.

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1695–1710. Maple and oak. H. 46 3/4", W. 19", D. 17 3/8". (Private collection; photo, Scottish Rite Masonic Museum and Library.)

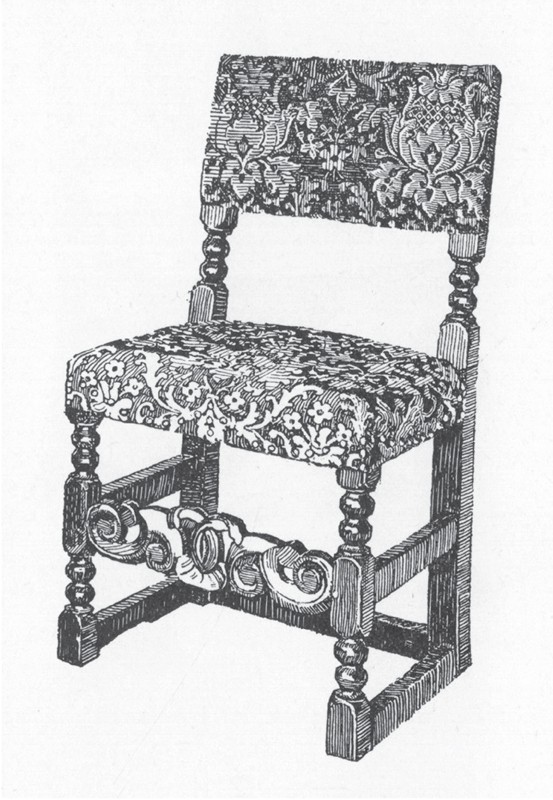

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1695–1705. Woods and dimensions not recorded. (Esther Singleton, The Furniture of Our Forefathers [New York: Doubleday, Page and Company, 1906], p. 183.)

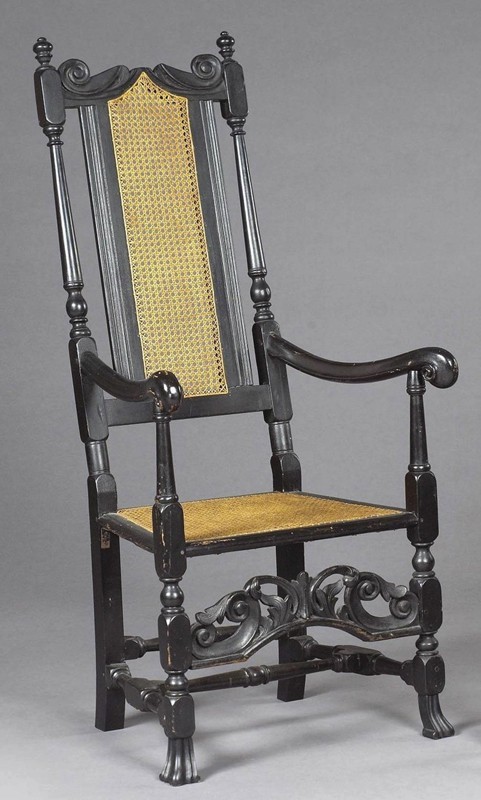

Armchair, London, 1695–1705. Beech; original Japanned decoration. H. 51 3/4", W. 23 3/8", D. 17". (Private collection; photo, Bill Russell.) This armchair’s seat would have been caned. It represents the first use of “banisters” as back support in English seating furniture. The ball feet are replaced.

Armchair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1700–1715. Maple. H. 53 3/4", W. 23 7/8", D. 16 3/8". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, gift of Mrs. Charles L. Bybee, 1980.379.) The complex, asymmetrically turned arm supports are essentially half of a Boston gateleg leg turning. This chair was given to Rev. John Chester (1785–1829) of Albany, New York, by one of his parishioners.

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1700–1715. Maple and oak. H. 46 3/4", W. 18 1/4", D. 14 3/4". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Miodrag R. Blagojevich, 1976-430.)

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1700–1715. Maple and oak. H. 48", W. 18", D. 14 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Jim Wildeman.)

Armchair, New York City, 1695–1715. Maple with oak and hickory. H. 47 1/2", W. 25 1/2", D. 27". (Courtesy, Historic Hudson Valley, Tarrytown, New York.) The feet and the finials are incorrectly restored.

Armchair, New York, 1700–1740. Maple. H. 50 1/2". (Courtesy, Sotheby’s Inc.) The feet are replacements.

Armchair, New York City, 1695–1710. Maple and oak. H. 52", W. 24 3/4", D. 17 1/2". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The urn and baluster turned arm supports are nearly identical to those on the rear posts of the armchair illustrated in fig. 28.

Side chair, New York City, 1695–1710. Maple and oak. H. 46 3/4", W. 18 1/4", D. 15". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, probably Boston, Massachusetts, 1705–1715. Maple and oak. H. 45 1/2", W. 18", D. 15". (Courtesy, Greene County [New York] Historical Society.) This chair descended through the Bronck family of Coxsackie, New York, and was discovered with remnants of the original Russia leather upholstery on the back.

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1705–1715. Maple and oak. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Sotheby’s, Fine American Furniture, Folk Art, Silver and China Trade Paintings including Property from the Estate of Esther Pace Kuna, New York, June 23, 1988, sale 5736, lot 445.) An early label on the chair states that it belonged to Rev. Thomas Potwine (1731–1802), who was born in Boston and moved to East Windsor, Connecticut. His grandfather was John Potwine (1668–1700), who immigrated to Boston in 1698, and his father was John Potwine (1698–1792), who was probably the chair’s first owner.

Armchair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1705–1715. Maple and oak; original leather upholstery. H. 50 1/2", W. 23 1/4", D. 17". (Courtesy, Peabody Historical Society and Museum; photo, Andrew Davis.) This chair belonged to Rev. Benjamin Prescott (1687–1777), the first pastor of South Church in Danvers (now Peabody), Massachusetts. The scrolled terminals of the arms and the feet are replaced. This chair is unique in that the original trapezoidal stitching in the seat is embellished with brass nails.

Detail of the stretchers of the armchair illustrated in fig. 38.

Side chair, probably Boston, Massachusetts, 1705–1715. Maple and oak; original leather upholstery. H. 46 1/2", W. 18", D. 15". (Courtesy, Albany Institute of History and Art, gift of James Ten Eyck, 1908.1; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chair descended through the Pierson family of Kingston, New York.

Detail of the original webbing and sackcloth under-upholstery of the side chair illustrated in fig. 40. The standard arrangement for webbing strips on side chairs applied by Boston and New York upholsterers was two strips front-to-back and one side-to-side. The trapezoidal-shaped stitching at the center of the seat is visible. Upholsterers would attach the webbing and then the sackcloth. The leather was roughly shaped to fit and then secured to the under-upholstery with waxed gut stitching. Grass was then stuffed in on the four sides and secured when the leather was nailed to the rails. The rough edges were concealed with trim strips of leather generally secured with double rows of decorative brass-headed nails on the front and sides, while the back edge was secured with wrought iron nails. The trim strip on the sides of this chair was secured along the top edge with brass-headed nails, but the bottom edge was secured with wrought tacks.

Detail showing the back of the crest of the side chairs illustrated in figs. 36 (left) and 40 (right). The back edges of the piercings are neatly chamfered, and the edges of the C-scrolls have a simple single chamfer at a 45 degree angle. While irregular now because of shrinkage, the leather pulled through the slot on fig. 40 would have originally been cut along a straight line.

Side chair, England, 1690–1710. Ash; original leather upholstery. H. 44 1/2", W. 19", D. 16". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1954-990.) The cylindrical turning between the seat and the lower back rail is identical to that found on the later groups of early baroque Boston chairs.

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1705–1715. Maple and oak. H. 47 1/2", W. 18 1/2", D. 15". (Private collection; photo, Andrew Davis.)

Armchair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1705–1715. Maple and oak. H. 51", W. 24", D. 22". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Table, Boston, Massachusetts, 1705–1720. Maple and white pine. H. 27 3/4", W. 37 3/4", D. 21 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The conical turning on the stretchers is nearly identical to that on the rear posts of group D chairs. The legs have turning identical to those on the arm supports of several of the leather-upholstered armchairs.

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1705–1715. Maple and oak; original leather upholstery. H. 48 1/2", W. 18 1/8", D. 14 1/2". (Courtesy, Wadsworth Atheneum, Wallace Nutting Collection, gift of J. Pierpont Morgan Jr., 1926.446; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chair descended in the Pierson family of Kingston, New York, and was first illustrated in Wallace Nutting, Furniture of the Pilgrim Century, 1620–1720 (Boston: Marshall Jones Company, 1921), p. 221, with a later crest that has now been removed. A remnant is all that remains of the lower ball on the foot.

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1705–1715. Maple and oak. H. 47 1/2", W. 19", D. 15". (Private collection; photo, Andrew Davis.)

Armchair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1705–1715. Maple. H. 48 1/2", W. 23", D. 17". (Courtesy, Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. William Y. Hutchinson Fund, 1989.57; photo, Art Resource, Inc.) The arms and feet are replaced; the arms would have resembled those on the armchair illustrated in fig. 45.

Side chair, New York City, 1705–1715. Maple and oak. H. 47", W. 18 1/2", D. 14 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, New York City, 1705–1715. Maple and oak. H. 45 3/4", W. 18", D. 14 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Armchair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1720. Maple and oak. H. 53 1/8", W. 22 3/4", D. 17 1/2". (Courtesy, Smithtown Historical Society, gift of Mrs. Norman Parke; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Family tradition maintained that this chair belonged to Ebenezer Smith (1712–1747). His father, Richard Smith II (ca. 1645–1720), was the chair’s probable first owner (Dean Failey, Long Island Is My Nation: Decorative Arts & Craftsmen 1640–1830, 2nd edition [Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.: Society for the Preservation of Long Island Antiquities, 1998], no. 23. pp. 26–7).

Armchair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1720. Maple and oak; original leather upholstery. H. 53 1/4", W. 22 7/8", D. 17". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, bequest of H. F. du Pont; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side view of the armchair illustrated in fig. 53. The height and dramatic cant of the chair back would make it susceptible to falling backward if not for the rearward kick of the rear feet.

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1720. Maple and oak. H. 47 1/2". (Courtesy, Freeman’s; photo, Thomas Clark.) The front stretcher is replaced. The original would have related to those on the chairs shown in figs. 52 and 53.

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1730. H. 46 3/4", W. 18 1/2", D. 14 7/8". (Courtesy, Washington’s Headquarters State Historic Site, Newburgh, New York Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation, WH.1971.641; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chair is one of three donated by Enoch Carter to Washington’s Headquarters prior to 1858. The chairs descended through the Ver Planck (also Verplanck) family and were reputedly used as altar furniture at the Dutch Reformed Church, Fishkill, New York.

Detail of the back of the crest of the side chair illustrated in fig. 56, showing the PVP brand. The back edges of the crest and the piercings are chamfered to lighten the crest visually when seen from the front.

Composite illustration showing the back of the lower stretcher of the group E side chair illustrated in fig. 56 (top) and group E side chair illustrated in fig. 69 (bottom). Boston chairmakers constructed their seating quickly and efficiently. As the saw kerfs visible here reveal, makers did not always plane the back surfaces of stretchers. The same is true of some crests.

Composite illustration showing the front turned feet of the group E side chair illustrated in fig. 56 (left) and group E side chair illustrated in fig. 69 (right). The baluster‑and-half-ball, or “double-ball,” foot was the standard for early eighteenth-century Boston chairmakers. Through centuries of use, many surviving chairs have lost the lower half‑ball if not their entire foot.

Armchair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1730. Maple and oak; original leather upholstery. H. 50 1/2", W. 24 1/2", D. 23". (Courtesy, Wadsworth Atheneum, the Evelyn Bonar Storrs Trust Fund, 1994.4.1; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) While the chair’s original owner is unknown, it descended in the Schuyler and Church families of New York. The chair was purchased from a descendant of John Baker Church (1777–1818) and Angelica Schuyler (1756–1814). Angelica was the daughter of Gen. Philip Schuyler (1733–1804) and Catherine Van Rensselaer (1735–1803) of Albany. The feet and the proper right finial are replaced.

Armchair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1730. Maple and oak; original leather upholstery. H. 52", W. 24 1/4", D. 21 1/4". (Courtesy, The Henry Ford, 30.557.64.) Henry Ford purchased the chair from Charles Woolsey Lyon of New York City in 1930. Lyon acquired the chair in 1901 from Mr. Stephen Schuyler of the Flats, Albany, New York. Stephen Schuyler stated that the chair originally belonged to Pieter Schuyler (1657–1724). The Flats is an area north of Albany along the Hudson River. The front stretcher is incorrectly replaced.

Nehemiah Partridge (1683–ca. 1737), Pieter Schuyler, Albany, New York, ca. 1718. Oil on canvas. 87 3/4" x 51". (Courtesy, New York State Museum.)

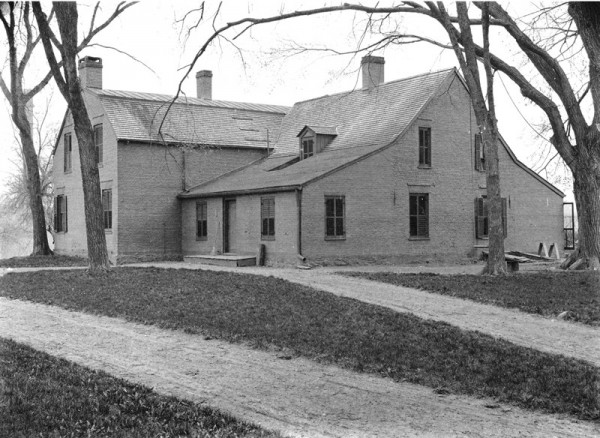

General Philip Schuyler House, ca. 1690 with a ca. 1765 addition, Colonie Township, Albany County, New York. (Courtesy, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, HABS no. NY-3102.) This house was destroyed by fire in 1962.

Armchair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1730. Maple and oak. H. 52 5/8", W. 23 1/8", D. 17". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, gift of Anne and Frederick Vogel III, 2016.538.) This chair is branded “W. MANCIUS” on the lower back rail. The feet are replaced.

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1730. H. 49 3/4", W. 18 1/2", D. 14 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The lower back rail is branded “W. MANCIUS”. The feet are replaced.

Composite illustration showing the brands on back of the lower back rails of the armchair illustrated in fig. 64 (left) and the side chair illustrated in fig. 65 (right).

Rev. George Wilhelmus Mancius, attributed to Pieter Vanderlyn (ca.1687–1778), Kingston, New York, ca. 1735. Oil on canvas. Measurements not recorded. (Courtesy, First Reformed Protestant Dutch Church of Kingston, New York.)

Armchair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1730. Maple and oak. H. 51 3/4", W. 23 1/4", D. 16 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chair was found in Yonkers, New York. Upholstery evidence indicates that this chair’s trim strip was secured on the side seat rails with a top row of brass-headed nails and the bottom with wrought tacks.

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1730. H. 49", W. 18", D. 15". (Courtesy, Washington’s Headquarters State Historic Site, Newburgh, New York Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation, WH.1971.643; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Four chairs from this set are known. According to Israel Sack, Inc., the chairs were purchased from descendants of the Van Rensselaer family.

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1730. Maple and oak. H. 47", W. 18 1/8", D. 15". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The feet are replaced.

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1730. Maple and oak. H. 48", W. 18 1/2", D. 14 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Jim Wildeman.)

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1730. Maple and oak; original leather upholstery. H. 48", W. 17 7/8", D. 14 5/8". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, bequest of Mrs. J. Insley Blair, 1951, 52.77.58; photo, image copyright © Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, Inc.)

Armchair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1730. Maple and oak. H. 51 1/4", W. 23", D. 16 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The upper portion of the crest rail is replaced.

Armchair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1730. Maple and oak. H. 50 5/8", W. 23 1/4", D. 16 7/8". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Miodrag R. Blagojevich, 1976-431.)

Armchair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1730. Maple and oak. H. 49 1/2", W. 23", D. 16 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1730. Maple and oak. H. 45 3/8", W. 18", D. 15 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Andrew Davis.)

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1730. Maple and oak. H. 45 1/4", W. 18", D. 15". (Private collection; photo, Andrew Davis.)

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1730. Maple and oak; original leather upholstery. H. 45 1/4", W. 18 1/2", D. 15 3/4". (Courtesy, Wadsworth Atheneum, Wallace Nutting Collection, gift of J. Pierpont Morgan Jr., 1926.440; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1730. Maple and oak. H. 38 3/8", W. 17 3/4", D. 14 3/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, bequest of H. F. du Pont; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1730. Maple and oak. H. 38 1/4", W. 18", D. 15 1/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Back stool, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1725. Maple. H. 44 3/4", W. 18 3/4", D. 15". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The feet and upper portion of the back are replaced.

Back stool, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1730. Maple. H. 48 1/4", W. 19 1/2", D. 15 1/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, bequest of H. F. du Pont, 1989.506; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The heels on this chair are quite pronounced and prevented the high-backed chair from toppling over.

Detail of the stretchers, legs, and double cyma-shaped front seat rail of the back stool illustrated in fig. 82. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Easy chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1730. Maple. H. 48 1/8", W. 31 1/2", D. 35 1/2". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 125th Anniversary Acquisition, gift of Anne H. and Frederick Vogel III, 1999.)

Couch, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1730. Maple. Dimensions not recorded. (Richard Withington, Inc., Oliver E. Williams Collection, Pigeon Cove, Cape Ann, Massachusetts, July 27, 1966, p. 22.)

Couch, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1730. Maple. H. 39 1/2", L. 61". (Courtesy, Bernard and S. Dean Levy, Inc.) This couch belonged to Rev. Daniel Shute (1722–1802) and his wife, Mary Cushing (1732–1756). Shute was the pastor of the Second Parish in Hingham (now Cohasset), Massachusetts, for nearly fifty‑six years.

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1705–1715. Maple and ash. H. 49", W. 18 3/4", D. 16 3/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This banister-back chair has a crest identical to those of the leather chairs illustrated in figs. 44 and 45.

Armchair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1730. Maple and ash. H. 52 3/4", W. 23", D. 16". (Private collection; photo, Jim Wildeman.) The feet are replaced. This chair and the one shown in fig. 89 originally would have been used with a large pillow that would have filled the space between the back rail and the seat.

Armchair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1730. Maple and ash. H. 52 5/8", W. 23 1/2", D. 16 5/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This is one of only two known examples of a Boston banister-back armchair with a carved crest rail and front stretcher. The other was offered by Roderic Blackburn but had replaced finials and feet.

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1730. Maple and ash. H. 49 1/2", W. 17 1/2", D. 14". (Private collection; photo, Andrew Davis.) The finials and the upper portion of the crest rail are replaced.

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1730. Maple and ash. H. 46 1/2", W. 18 1/4", D. 14 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1730. Maple and ash. H. 47", W. 18 1/2", D. 14 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Andrew Davis.) This chair was embellished with gilt decoration in the late nineteenth century. This chair has lost a portion of its feet.

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1730. Maple and ash. H. 47 1/2". (Courtesy, Sotheby’s, Important Americana including Property from the Collection of Joan Oestreich Kend, New York, January 21, 2017, lot 4327.)

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1730, Maple and ash. H. 48 1/8", W. 18 3/4", D. 14 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Jon Lam.) This chair, like the examples illustrated in figs. 79 and 80, has its crest rail placed on top of the stiles rather than between them.

Armchair, probably London, 1705–1715. Walnut. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Victoria and Albert Museum, given by W. H. Hammond in memory of Lieut. R. M. Hammond, Circ. 525-1921.)

The chair originally had a caned back and seat. The feet are replaced. The chairs in group E have arched crests and stretchers and turnings related to those on this chair.

Side chair, probably London, 1705–1715. Woods and dimensions not recorded. (Photo, Symonds Collection, Decorative Arts Photographic Collection, Winterthur Museum.) This chair originally had a caned back. The double side stretchers belie its later date as indicated with its arched crest, simple conical stiles, and cylindrical turnings above the seat.

Armchair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1705–1725. Maple. H. 50 3/4", W. 25 3/4", D. 27". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1725. Maple. H. 50 3/4", W. 17 1/2", D. 14 3/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Armchair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1725. Maple. Measurements not recorded. (Courtesy, Northeast Auctions, New Hampshire Weekend Auction, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, November 7, 2004, lot 723.) This chair has lost the upper portion of the carved crest, and the feet are replaced.

Armchair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1725. Maple and birch. H. 55". (Courtesy, ©2005 Christie’s, Important American Furniture, Folk Art, Silver and Prints, New York, January 21, 2005, sale 1474, lot 544.)

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1725. Maple. H. 48 3/4". (Courtesy, ©2005 Christie’s, Important American Furniture, Folk Art, Silver and Prints, New York, January 21, 2005, sale 1474, lot 545.)

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1720–1735. Maple. H. 45 1/4", W. 18", D. 14 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1720–1735. Maple. H. 45 1/4", W. 17 1/2", D. 14 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Armchair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1720–1740. Maple. H. 50 3/4", W. 23 3/8", D. 16 3/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1720–1740. Maple. H. 45 1/2", W. 19", D. 18". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Skinner, Inc., American Furniture & Decorative Arts, Boston, Massachusetts, February 18, 2007, sale 2349, lot 229.)

Armchair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1720–1740. Maple. H. 49 7/8", W. 24 1/4", D. 21". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, bequest of H. F. du Pont, 1954.528; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This armchair descended in the Hancock family of Boston, Massachusetts. This chair is one of the earliest examples showing the placement of the medial stretchers forward.

Armchair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1725–1745. Maple. H. 44 3/4", W. 23", D. 18 3/4". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Henry Herbert Edes, 36.37.) This chair descended in the Edes family of Boston and South Dartmouth, Massachusetts.

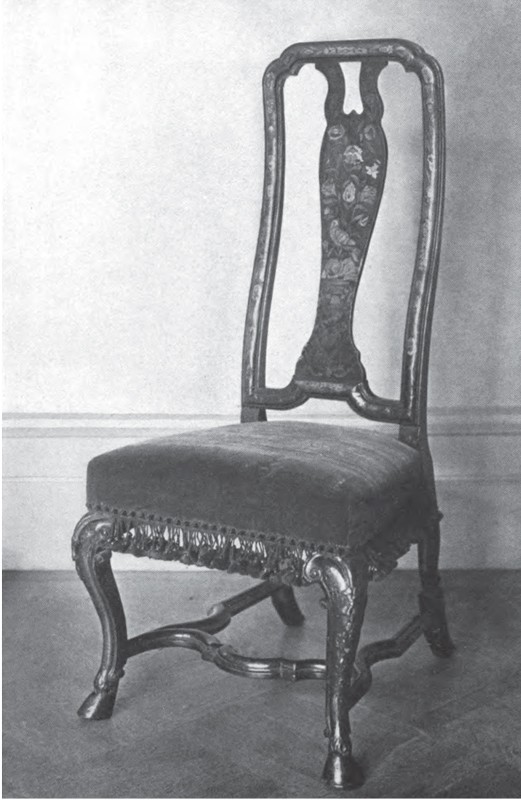

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1725–1730. Maple and oak. H. 48 1/2". (Courtesy, Skinner Inc., Personal Collection of Lewis Scranton, Killingsworth, Connecticut, May 21, 2016, sale 2897M, lot 303.) The feet are replaced. The splat directly relates to contemporaneous Chinese vases on stands.

Baluster vase, Qing Dynasty, Kangxi Period (1662–1722). (Courtesy, Sotheby’s Inc.)

Side chair, probably London, 1715–1725. Woods and dimensions not recorded. (Helen Churchill Candee, Jacobean Furniture and English Styles in Oak and Walnut [New York: Frederick A. Stokes Company, 1916], pl. 31.)

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1720–1745. Maple and oak; original leather upholstery. H. 45 1/4", W. 17 3/4", D. 18 1/8". (Courtesy, Wadsworth Atheneum, gift of James B. Cone, by exchange, 1982.160; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The applied carved front foot facings have been lost.

Armchair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1720–1745. Maple and oak. H. 47 3/4", W. 22 3/4", D. 16 7/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, bequest of H. F. du Pont, 1958.556; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1720–1750. Maple and oak. H. 45 1/2", W. 17 1/2", D. 15". (Private collection; photo, Andrew Davis.) The applied carved front foot facings have been lost.

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1720–1750. Maple and oak. H. 45 1/2", W. 17 1/2", D. 15". (Private collection; photo, Andrew Davis.)

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1720–1750. Maple and ash. H. 44 3/4", W. 18", D. 15". (Private collection; photo, Andrew Davis.) The front scroll feet on cabriole legged chairs are not laminated because of the extra dimension of the leg stock necessary to produce the curvature.

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1720–1750. Maple and oak. H. 44 3/4", W. 19", D. 15 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Andrew Davis.)

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1728–1735. Maple and oak. H. 45 7/8", W. 19", D. 15 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1720–1750. Maple and oak. H. 44 3/4", W. 18 1/4", D. 14 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Andrew Davis.)

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1720–1750. Maple. H. 44 1/4", W. 20", D. 15". (Private collection; photo, Andrew Davis.) The applied carved front foot facings have been lost.

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1720–1750. Maple and ash. H. 45 3/4", W. 19", D. 14 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Andrew Davis.) A related upholstered side chair with a solid splat is illustrated in Joan Freund and Leigh Keno, “The Making and Marketing of Boston Seating Furniture in the Late Baroque Style,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1998), fig. 8.

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1720–1745. Maple and oak; original leather upholstery. H. 41 3/4", W. 19", D.14 3/8". (Courtesy, Newport Historical Society.) The original owner of this chair may have been William Ellery (1727–1820) of Newport, Rhode Island. William C. Cozzens (b. 1846) found it in the Ellery House, Thames Street, Newport, Rhode Island, and it was donated to the Newport Historical Society in 1855. The applied carved front foot facings have been lost.

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1725–1750. Maple and ash. H. 44 3/4", W. 18", D. 15". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, probably Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1720. Maple. H. 52 1/8", W. 21 3/8", D. 22 1/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, bequest of H. F. du Pont, 1959.28.2; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, England, 1700–1710. Beech. Measurements not recorded. (Courtesy, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, W.36-1914.)

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1740–1770. Maple. H. 39 1/2", W. 22", D. 20 1/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, Museum Purchase with funds provided by Mr. and Mrs. George M. Kaufman, Mr. Martin E. Wunsch, and an anonymous donor, 1998.7; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The trim strip of leather is applied with a double row of brass-headed nails just as chairs made in Boston were ornamented half a century earlier.

Detail of the carved crest of the side chair illustrated in fig. 2.

Detail of the carved crest of the side chair illustrated in fig. 25.

Detail of the carved stretcher of the side chair illustrated in fig. 25.

Detail of the carved crest of the armchair illustrated in fig. 28.

Detail of the carved stretcher of the armchair illustrated in fig. 28.

Detail of the carved stretcher of the armchair illustrated in fig. 29.

Detail of the carved crest of the side chair illustrated in fig. 31.

Detail of the carved stretcher of the side chair illustrated in fig. 31.

Detail of the carved stretcher of the armchair illustrated in fig. 32.

Detail of the carved crest of the armchair illustrated in fig. 34.

Detail of the carved stretcher of armchair illustrated in fig. 34.

Detail of the carved crest of the side chair illustrated in fig. 36.

Detail of the carved stretcher of the side chair illustrated in fig. 36.

Detail of the carved crest of the side chair illustrated in fig. 40.

Detail of the carved stretcher of the side chair illustrated in fig. 40.

Detail of the carved crest of the side chair illustrated in fig. 44.

Detail of the carved stretcher of the side chair illustrated in fig. 44.

Detail of the carved crest of the armchair illustrated in fig. 45.

Detail of the carved stretcher of the armchair illustrated in fig. 45.

Detail of the carved crest of the side chair illustrated in fig. 50.

Detail of the carved stretcher of the side chair illustrated in fig. 50.

Detail of the carved crest of the armchair illustrated in fig. 52.

Detail of the carved stretcher of the armchair illustrated in fig. 52.

Detail of the carved crest of the armchair illustrated in fig. 53.

Detail of the carved stretcher of the armchair illustrated in fig. 53.

Detail of the carved crest of the side chair illustrated in fig. 56.

Detail of the carved stretcher of the side chair illustrated in fig. 56.

Detail of the carved crest of the armchair illustrated in fig. 60.

Detail of the carved stretcher of the armchair illustrated in fig. 60.

Detail of the carved crest rail of the armchair illustrated in fig. 64.

Detail of the carved crest rail of the side chair illustrated in fig. 65.

Detail of the carved stretcher of the side chair illustrated in fig. 65.

Detail of the carved crest rail of the armchair illustrated in fig. 68.

Detail of the carved stretcher of the armchair illustrated in fig. 68.

Detail of the carved crest rail of the side chair illustrated in fig. 69.

Detail of the carved stretcher of the side chair illustrated in fig. 69.

Detail of the carved crest rail of the side chair illustrated in fig. 70.

Detail of the carved stretcher of the side chair illustrated in fig. 70.

Detail of the carved crest rail of the side chair illustrated in fig. 71.

Detail of the carved stretcher of the side chair illustrated in fig. 71.

Detail of the carved crest rail of the side chair illustrated in fig. 72.

Detail of the carved crest rail of the side chair illustrated in fig. 79.

Detail of the carved crest rail of the side chair illustrated in fig. 80.

Detail of the carved crest rail of the armchair illustrated in fig. 88.

Detail of the carved crest rail of the armchair illustrated in fig. 89.

Detail of the carved stretcher of the armchair illustrated in fig. 89.

Detail of the carved stretcher of the side chair illustrated in fig. 90.

Detail of the carved crest rail of the side chair illustrated in fig. 91.

Detail of the carved crest rail of the side chair illustrated in fig. 92.

Detail of the carved crest rail of the side chair illustrated in fig. 94.

Detail of the carved stretcher of the side chair illustrated in fig. 94.

Detail of the carved crest rail of the armchair illustrated in fig. 97.

Detail of the carved crest rail of the side chair illustrated in fig. 98.

Detail of the carved stretcher of the side chair illustrated in fig. 98.

Detail of the carved stretcher of the armchair illustrated in fig. 99.

Detail of the carved crest rail of the armchair illustrated in fig. 106.

The comfortable and sturdy “Boston” chair, with its curved back and frame made of native maple and oak, is evidence of entrepreneurship in colonial Boston (fig. 1). The first mention of this distinctive form was documented on February 27, 1723, when Thomas Fitch (1669–1736), a prominent Boston upholsterer, billed Edmund Knight £16.4 (27s. each) for “1 doz crook’d back chairs.” Crooked or curved stiles had not been used in the colonies before then, and it was at this time that early baroque seating with turned stiles began to wane. “Boston” chairs stand as the finest representations of this important design transition from the early to the late baroque period in American seating furniture.[1]

Skilled in upholstering, Thomas Fitch was also a very enterprising merchant. As his surviving account books and letterbooks attest, he regularly sent chairs to numerous towns and cities throughout New England and the mid-Atlantic colonies. These trade routes were not transitory, but rather had been established over decades of relationships. Samuel Grant, Fitch’s apprentice, continued to use these same routes after his master’s death. The “Boston chair” design was not conceived in a moment of inspiration by Boston chairmakers. Rather, its design was derivative of seating furniture that was being imported continually from England. Before 1723 Boston chairmakers had been producing chairs in the early baroque style for over a quarter century. This article addresses this seating furniture and how chairmakers adapted their production to the changing tastes of their clients.[2]

America’s early baroque seating furniture has been discussed in numerous books and articles over the past century. The most comprehensive study is Benno M. Forman’s American Seating Furniture, 1630–1730, published in 1988. While additional chairs have surfaced since then and new research findings have been presented, to date all of the distinct Boston forms had never been assembled to demonstrate the progression from low-backed “Cromwellian” chairs to the archetypal crooked-back chair. The broad diversity of designs presented here demonstrates how the influx of imported chairs resulted in a bourgeoning of tastes in Boston and a broadening of that city’s stylistic and economic influence during the first quarter of the eighteenth century.[3]

As Robert F. Trent and Mark Anderson’s article in the 2017 volume of American Furniture suggests, the high-style seating form for most middling and well-to-do colonists during the second half of the seventeenth century was the Cromwellian chair. It was not until the last fifteen years of the seventeenth century that new forms, and chairmakers well versed in making them, began to appear in Boston. With its taller back, upholstered vertical back panel, and decorative rear posts with finials, the Boston side chair shown in figure 2 (see Appendix, fig. 126) was clearly influenced by late seventeenth-century English seating (figs. 3-5). The chairs illustrated in figures 4 and 5 display a range of features that had become standard by the mid-1680s, including carved stretchers and carved crests with slots through which turkey work or leather could be pulled and secured at the back.

The origin of the side chair illustrated in figure 2 has been in dispute among furniture scholars for more than thirty years. Oswaldo Rodriguez Roque describes that object as “probably New England” in American Furniture at Chipstone (1984), whereas Neil D. Kamil attributes it to New York City in his American Furniture (1995) article. The chair descended through the Pritchard family of Boston and Milford, Connecticut. The scion of the family, Roger Pritchard (1600–1671), arrived in Boston in 1636 and died in Milford. Given Pritchard’s life dates and the chair’s probable date range for manufacture, it is impossible that he was the original owner. It is also unclear when and how the chair came to be owned by Pritchard descendants. Fortunately, the chair’s origin can be determined by its construction and design. Although the crest rail design—scrolled leaves and central flower motif—has no known American cognate, the mortise-and-tenon joinery follows the Boston practice identified by Roger Gonzales and Putnam Brown in their article in the 1996 volume of American Furniture. In addition, the chair’s finials are almost identical to those on the Boston leather-upholstered side chair and couch illustrated in figures 6 and 7.[4]

The side chairs and couch illustrated in figures 6–8 reveal how Boston chairmakers transitioned from Cromwellian seating to early baroque forms. An early date of manufacture is indicated by the back panel of the side chair shown in figure 8, which is the same size as that of a typical Cromwellian side chair but oriented vertically rather than horizontally. Whoever made this chair also made Cromwellian chairs and was directly influenced by imported English seating. An example in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum appears to be the antecedent of the Boston form (fig. 9).[5]

Forman divided early baroque Boston chairs into two discrete phases, those with turned rear posts and those with molded and curved rear posts. Based upon surviving examples, the author has defined five distinct groups of high-back leather-upholstered chairs with turned posts, designated as A through E. Group A includes the high-back, ball-turned chairs discussed earlier and one armchair (fig. 10). The latter example has finials identical to those on the side chair illustrated in figure 8 as well as on seating at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Until the discovery of the armchair, only one other American example with foliate carving on its arms was known (fig. 11). Some scholars attributed these armchairs to New York and asserted that the carving reflected Dutch influence. Although the ornament may have Netherlandish antecedents, the leaf carving on the Boston chairs was most likely inspired by that on the arms of imported English cane chairs (fig. 12), which were influenced by Dutch seating. The construction of both armchairs and the turnings on the armchair shown in figure 10 match those on Boston Cromwellian chairs. The turning parallels are particularly meaningful as they relate in both shape and proportion.[6]

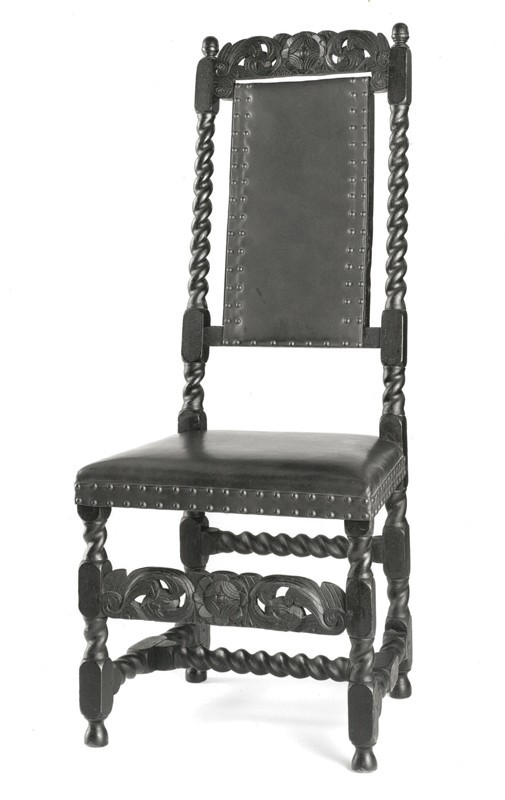

During the last decade of the seventeenth century, a steady stream of imported London cane and leather-upholstered chairs bombarded Boston chairmakers with new designs. The group B foliate carved armchair confirms that Boston craftsmen strove to keep abreast of the latest seating fashions (fig. 11). Though similarly constructed, chairs in groups A and B differ stylistically. Most obvious is the use of various turned elements in group B as opposed to the repetitive ball turnings typical of group A. Boston chairmakers and their patrons undoubtedly saw imported chairs with intricately turned rear posts (fig. 5) and desired to produce or own similar seating.

Group B chairs have rear posts with specific sequence turnings. The armchair shown in figure 11 has the characteristic “muffin top” finial surmounting (from top to bottom) a filleted, compressed ball; opposing filleted, echinus turnings; a tapered conical column; a bead; a compressed baluster; a ring; an ovolo; a baluster; and a ring-ball-ring. The ovolo and baluster turning combination that resembles a toadstool is the definitive hallmark of the group. Another diagnostic group B turning sequence is the “barrel” turning flanked by shallow rings on the rear posts directly above the seat. The front stretcher is the last Boston hallmark (fig. 14a). Its bilaterally symmetrical sequence of ring-ovolo-baluster-ovolo-compressed baluster-filleted ring-compressed baluster-ovolo-baluster-ovolo-fillet quickly became the standard for early eighteenth-century Boston chairmakers. The chair’s arm support turnings are analogous to the opposing baluster leg and stretcher turnings on contemporaneous Boston gateleg tables (fig. 15b). Two group B side chairs and the armchair illustrated in figure 11 have nearly identical rear posts except for the omission of the lowermost ring; the filleted ball is decreased substantially in size because of the reduced post height (figs. 13c, 16, 17). While both side chairs retain their feet and finials, their height differences indicate that chairmakers were making sets of chairs nearly indistinguishable from each other. As Gonzales and Brown noted, by the beginning of the eighteenth century Boston turners were mass producing individual components. The Cromwellian roots of group B side chairs are apparent on the retention of double side stretchers as opposed to the single stretcher on the armchair (fig. 11).[7]

Seventeenth-century Boston chairmakers offered little choice to their patrons, as is evident from the near uniformity of Cromwellian chair design. But with the importation of variously designed cane chairs at the end of the century, ambitious craftsmen were compelled to provide design options. These choices included foliate carved arms or simpler scroll arms, rectangular or turned side and rear stretchers, carved crests and stretchers, and plain crests. Fully turned stretchers like those on the armchairs illustrated in figures 18–20 were an option available to patrons, but they represented a significant cost increase over the standard rectangular forms. The same can be said of the arms on the chair shown in figure 18, which have compound downward and outward curves terminating with volutes. Their sweep and shape were almost certainly derived from the arms of imported English cane chairs. In addition to structural options, Boston chairmakers offered different finishes for their seating. On February 1, 1703, Thomas Fitch wrote William Crouch and Company, “Please to mind that what chairs ye send do not of a redish colour, but a good natural walnut, brown colour and well varnish and bot what I have writ for if not sent do most of y’or work five shills ap.”[8]

The group B armchair illustrated in figure 20 originally belonged to Johannes Hardenbergh (ca. 1670–1745) of Ulster County, New York. On April 20, 1708, he, Leonard Lewis, Philip Rokeby, William Nottingham, Peter Fauconnier, Robert Lurting, and Benjamin Faneuil received a grant of approximately two million acres of land, known as the Hardenbergh, or “Great,” Patent. Hardenbergh’s connection to Faneuil, who was one of Thomas Fitch’s agents for marketing and selling Boston seating in New York, suggests that the chair owned by Hardenbergh came from Fitch. Faneuil’s extensive mercantile ties allowed him to sell chairs to wealthy New Yorkers, as is demonstrated by both his correspondence with Fitch and the provenances of many surviving chairs.[9]

Given the significant number of chairmakers active in Boston at the turn of the seventeenth century, it is not surprising that there are several variants of the group B style chair. The sequence of turnings on the rear posts of the side chair illustrated in figure 21 are the same as those on group B armchairs (figs. 13a–c), but the finials are of a different style and the barrel turnings above the seat are scored along their center. A chair that appears to be from the same set once belonged to Margaretta Sanders (1764–1830) of Scotia, New York. Margaretta was the granddaughter of Barent Sanders (1678–1757), a prominent Albany merchant and likely the original owner of both chairs.[10]

Another group B chair descended through the Vanderlyn family of Kingston, New York (fig. 22). This example has turnings that differ markedly from the standard format (fig. 13c). They include balusters above the seat and a modified “Boston” stretcher, with a compressed ball at either end. The maker of this chair also incorporated a hollowed back (the crest rail and lower back rail have a concave curve)—a detail found on contemporaneous English leather chairs with carved crests (fig. 5). This practice was short lived, as it is not present on any later leather-upholstered chairs.[11]

Benno Forman attributed the side chair illustrated in figure 22 to New York, whereas decorative arts scholar Richard Randall postulated that an identical chair was made in the Piscataqua area of New Hampshire due to its discovery there. Gonzales and Brown identified it as a Boston product, but other possible towns of origin include Salem, Ipswich, and Newbury. All of these were wealthy communities and within Boston’s area of cultural influence. As exemplified by the Symonds shop in Salem, which was managed by James (1633–1714) and Samuel (1638–1722), these towns had craftsmen with the skill to produce chairs like the example shown in figure 22.[12]

A side chair related to the Vanderlyn example has nearly all of its original leather upholstery (fig. 23). It also has baluster turnings above the seat and balls at either end of the front stretcher, details found on the preceding side chair (figs. 14c and 22). The high front stretcher changes the proportions, and the debased turnings (with the replacement of the inner pair of balusters with a pair of reels centering a ball) of that component might initially suggest that the Vanderlyn chair and the example shown in figure 23 are not Boston products. Coincidentally, three nearly identical chairs originally belonged to Rev. Caleb Cushing (1673–1752) of Salisbury, Massachusetts. As Gonzales and Brown contend, provenance does not necessarily determine origin. The chair illustrated in figure 24 shares nearly all the attributes of the chair shown in figure 23 except that its front stretcher is a classic “Boston” variety. Therefore, while it is conceivable that these chairs could have been made in Salem or one of the other larger Essex County towns, it is more likely that they are Boston products.[13]

The earliest recorded reference to a Boston chair with a carved crest is Thomas Fitch’s September 9, 1709, letter to Benjamin Faneuil regarding the latter’s failure to sell his chairs:

I wonder the chairs did not sell; I have sold a pretty many of that sort to Yorkers since, and tho some are carv’d yet I make Six plain to one carv’d; and can’t make the plain so fast as they are bespoke, so yo may assure [them] that are customers that they are not out of fashion here. . . . I desire that you would force the sale of the chairs. . . . I also submit the price of them to your patience. It’s better to sell them than to let them lie. It might be better to have them rubbed over that they may look fresher.

The side chair illustrated in figure 25 is the only example from group B with a carved crest. It was originally published in the 1896 folio Colonial Furniture and Interiors, compiled and photographed by Newton W. Elwell, and listed as “Furniture in Salem, Mass., 17th Century.” A side chair that once belonged to D. J. and Alice Shumway Nadeau (fig. 26) appears to be carved by the same hand as the chair shown in figure 25. A Cromwellian chair that once belonging to Charles Waters of Salem, Massachusetts, further demon-strates that various styles of chairs continued to be produced in Boston during the first decade of the eighteenth century (fig. 27). Its front stretcher is nearly identical to that of the chair illustrated in figure 25.[14]

As is the case with their English counterparts, the earliest “carved topp’d” Boston chairs have crests with a horizontal slot through which the leather hide or textile of the back could be inserted, pulled tight, and attached to the backside with wrought iron tacks (see fig. 42). These early crests were designed with a broken scroll or, as royal chairmaker Thomas Roberts (active 1685–1714) identified them, a “horsebone” scroll. The body of the scroll has a medial ridge that attenuates towards the volutes and terminates in a circle. As furniture scholar Adam Bowett has noted, the horsebone scroll was a motif on English cane chairs made between 1690 and 1710 (fig. 28). Marking a departure from the English tradition, Boston carvers made the center of the volutes of different sizes and on the front stretchers added a circular device in the interstice between the volute and the break in the scroll—likely to add strength due to its being extensively pierced.[15]

The study of early Boston chairs is one of transition. Chairmakers continually updated their designs in response to the latest imported seating regularly arriving at Boston’s docks. An armchair given to Albany, New York, Rev. John Chester (1785–1829) by one of his parishioners represents the fullest maturation of group B design (fig. 29). Coinciding with this apex of form is the emergence of a new finial and rear post design allied with group C.[16]

Group C finials, with their well-defined urn-shaped bases surmounted with a slightly separated compressed ball capped with a diminutive, squat, conically shaped button or cylinder, are the earliest ascribed attribute of “second-generation” Boston leather chairs by Gonzales and Brown. The plainer turnings of the upper rear posts, with what Forman defined as a collarino or ring rather than the more complex opposing filleted echinus turnings, became the standard “Boston” post design. On the crest and stretchers of the armchair illustrated in figure 29, robust, layered leafage with sprigs emanating from pronounced deep sinuses replaces the interlaced sprigs on the carved side chair from group B (fig. 25). Another innovation in Boston chair design was the incorporation of a ball turning between the juncture of the arm and lower back rail. As the backs of chairs reached higher, -makers realized that the large square block between the stile and the barrel turning above the seat was visually too large and needed to be interrupted. A simple, compressed ball turning was their solution. The resulting chair, in its entirety, perfectly embodies the definition of baroque (fig. 29).

The back posts of two side chairs (figs. 30, 31) exhibit a divergent turning sequence. The “toadstool” turnings on the armchair shown in figure 29 are replaced with a baluster topped with a filleted ring, which is another -hallmark characteristic of group C chairs. The crest and stretcher carvings of the chair illustrated in figure 31 are merely smaller versions of those on the armchair (fig. 29); the only differences are the uncarved circular device in the stretcher and the sizes of the volute centers.[17]

With later baroque as well as rococo chairs, design books played an invaluable role in the creation of American seating furniture. Similar designs appeared in various colonial communities at vastly different times because books disseminated them in an unsystematic way. Could the variances in Boston’s early baroque seating furniture suggest that the dating of these traits and chairs in general may not be linear? Early eighteenth-century English chairmakers often changed their forms based upon both cultural and manufacturing demands, not design books. English chairmakers responded to their customers’ tastes by combining design sensibility with expeditious production, resulting in a significant upheaval in chair design during the first quarter of the eighteenth century. Boston chairmakers, in order to compete with imports, made related chairs that the American marketplace desired. Thus the development of Boston’s early baroque seating furniture was linear, driven by the ever-increasing influx of English chairs.

The early New York provenances of many leather chairs has led some scholars to attribute their origin to New York City and its environs. The reliance on provenance for attributions can be considerable, especially when combined with an apparent lack of additional information to suggest otherwise. Benno Forman, who relied on ownership histories to attribute several Boston leather chairs to New York, cited correspondence between Thomas Fitch and Benjamin Faneuil to support his argument. However, Fitch’s letterbooks actually suggest the opposite: they document the presence of a large and energetic market for Boston leather chairs in New York. Other colonial shipping records, though fragmentary, also detail the importation of Boston chairs into New York: nineteen arrived on the Dolphin of New York (Jacob Waldron, master) on May 10, 1716; the following March, the sloop Union, registered in Boston and captained by Joshua Thomas, brought a couch and twenty-five chairs; and on April 20, 1717, the sloop Warwick departed Boston for New York with a cargo including a dozen leather chairs. Although the consigners and sellers of the seating listed in these shipping records are not known, it is clear that Fitch was but one of many individuals involved in the leather chair trade between Boston and New York. On July 10, 1721, Boston merchant Edmund Knight billed -Robert Livingston of Livingston Manor, New York, £42.0.6 for “2 doz. Russia leather chairs & 3 elbow chairs.” Knight acted as Livingston’s factor in Boston. On November 10, 1722, the former wrote the latter, “Your couch is now sent by Schermerhorn & put into Mr. Van Horns bill of lading & you have enclosed Mr. [William] Down[es] note for making it.”[18]

As historian Neil Kamil surmised, New York craftsmen “did not sit idle while Fitch and others flooded the affluent New York market with -Boston leather chairs.” Kamil, Gonzales, and Brown have demonstrated that leather chairs, including elaborate carved versions, were made in New York, albeit in vastly smaller numbers. One such chair was made for Stephanus Van Cortlandt (1643–1700) or his son, Philip (1683–1748) (fig. 32). Its crest and stretcher carving, and pseudo barrel turning beneath the junction of the arm, likely reflect the maker’s desire to emulate contemporaneous Boston armchairs or imported English chairs. The Van Cortlandt chair’s upper rear post ovoid turning is a New York feature also occurring on banister-back seating (fig. 33). While the stretchers are of the same configuration as -Boston examples, the turning profiles relate to those on contemporaneous New York gateleg tables. The shape of the arms also confirms its New York attribution; they have a tube-like appearance, with a deeper curvature than Boston arms, and relate to arms on Northern European armchairs.[19]

The armchair illustrated in figure 34 is visually similar to the Boston example that belonged to Rev. John Chester (fig. 29), but the construction of the former possesses all of the attributes Gonzales and Brown associate with New York work. Its post and arm support turnings and front stretcher placement are also dissimilar from the Boston tradition. As noted by -Forman, urn turnings like those on the supports mirror details on a number of New York gateleg tables as well as on the posts of English cane chairs (fig. 28). The arms on the chair illustrated in figure 34 are heavier than those on Boston examples, and their shape bears a closer relationship to the arms on the Van Cortlandt chair. Another difference is the design of the carved front stretcher, which uses an inverted leaf sprig to connect the interstice in the horsebone scroll rather than a flower. The most telling attribute of this chair’s origin, however, is the broad squat baluster turning located on the rear post directly above the seat; nearly all unequivocally New York early baroque leather-upholstered chairs share this attribute. A side chair likely made by the same craftsman also survives (fig. 35). Its only differing characteristics are the uncarved circular interstices in the front stretcher and the lack of a thin collarino on the rear post’s lower baluster turning.[20]

When the Chester armchair was made, the use of horsebone scrolls was waning in England. At that time, chairs with more vertical backs were in fashion, and paired C-scrolls were more effective at drawing the eye upward than horsebone scrolls. A chair that descended in the Bronck family of -Coxsackie, New York, represents a major milestone for Boston chairmakers (fig. 36). As the earliest leather-upholstered chair to incorporate a C-scroll carved crest, an upward curved C-scroll carved stretcher, and rear post composed of an elongated conical and a baluster turning, this chair stands apart from other group C seating and places it as the progenitor of group D chair design. Notwithstanding, this chair also has traditional group C features: the crest barely extends above the finials; a circular device is used in the C-scroll interstices; the lower side and rear stretchers are at the same height; and the Boston barrel turning remains above the seat.

A side chair that once belonged to Rev. Thomas Potwine (1731–1802) (fig. 37) represents a less expensive alternative to carved examples like the one shown in figure 36. Rev. Potwine was born in Boston and died in East Windsor, Connecticut. Given Potwine’s birth date, it is probable that he inherited the chair from his father, John (1698–1792) or mother, Mary (née Jackson) (1698–1766). Except for the “Boston” front stretcher, the Potwine chair has turned components virtually identical to those on the Bronck chair (fig. 36).[21]

An armchair that reputedly descended from Rev. Benjamin Prescott (1687–1777), the first pastor of South Church in Danvers (now Peabody), Massachusetts, is possibly by the maker of the Potwine chair (fig. 38). The rear post turnings are identical to those on the Bronck and Potwine chairs. Although fitted with the standard “Boston” front stretcher, the Prescott armchair is unusual in having conical turnings rather than balusters on the other stretchers and arm supports (fig. 39). Conical turnings are common on English cane chairs but rare on American leather chairs. The compressed ball turning on the rear posts, between the arm joint and lower back rail, relates to those on the Chester armchair (fig. 29).

A side chair that descended in the Pierson family of Kingston, New York, appears to be from the same shop that produced the Bronck family chair (figs. 36, 40). The former is in remarkable condition and retains its original Russia leather upholstery. The seat has two strips of webbing running from front to back and one from side to side, a configuration used by Boston upholsterers since the early seventeenth century (fig. 41). The crest and front stretcher of the Pierson and the Bronck chairs have identical carving and the same diagonal chamfer on the back edge of the crest (figs. 42, 137–140). Despite these overt similarities, the Pierson chair differs from the Bronck chair in its addition of a compressed ball turning beneath the baluster turning on the rear post and the omission of its upper side stretchers. It is also the earliest known example showing the simplification of the barrel turning (associated with groups B and C) to a cylinder. Imported English chairs similar to the example shown in figure 43 may have been the antecedent for cylindrical turnings of that type. While patron preference may account for the variance between the Pierson and Bronck chairs, the desire to expedite production is a more likely explanation. Cutting four additional mortices is time-consuming, and it is significantly easier for a turner to shape a cylinder rather than a more complex barrel turning. Combined, these alterations surely decreased the production time of the Pierson chair. It does not appear from surviving records, however, that these timesaving approaches resulted in reduced prices for consumers. The consistency of price for form in the first few decades of the eighteenth century, while factoring inflation, implies that fashion trends influenced price beyond the simple mechanics of the cost of labor.[22]

The chairs illustrated in figures 44 and 45, with their C-scrolled, carved, and slotted crest, their simplified rear posts with a single collarino at the top of an elongated cone above a baluster turning, their cylindrical turnings above the seat, and their dissimilarly sized front leg baluster turnings, are the most highly developed examples of group D seating. Some contemporaneous Boston tables exhibit similar features, like conical and baluster turnings on the stretchers and legs (fig. 46). These chairs’ rear posts, like the Pierson chair, have a cylindrical turning above the seat (fig. 13f). Here, however, the Boston turners chose to deeply score the cylinders at their ends. These marks delineate a vestige of the rings that flanked the group B and C barrel turning. Boston turners further used score marks to represent the detailed ring turning located directly above the baluster turning on the rear posts of later group E chairs. Group D chairs were the first to have a raised rear stretcher, a compressed baluster-and-ball foot, and prominent heels to aid in balancing the chair’s taller backs. Like the Pierson and Bronck chairs, the crests on group D chairs barely extend beyond the tops of the finials, which all have conical caps (figs. 141, 143). In contrast, the crest and stretcher carving has a lively three-dimensional quality. The sprig tips curve back towards the center of the C-scrolls, and deeply carved sinuses are present on both the crest and stretcher. The crest of the armchair also has an added extra embellishment of horizontally aligned parallel gouges to the midribs of the central leaf carving (fig. 143).[23]

The presence of related debased carving on chairs recovered in Essex County, Massachusetts, and southern New Hampshire might suggest that the Bronck and Pierson chairs were not made in Boston, were it not for their wood choice, joinery quality, and similarity of their turnings to other group C chairs. Boston was home to many chairmakers, turners, and carvers at the beginning of the eighteenth century. This heterogeneity of craftspeople would naturally result in the production of many similar, yet disparate, chairs. Two nearly identical plain crest group C chairs validate this supposition (figs. 47, 48). The finials on the Wadsworth Atheneum’s Pierson family chair (fig. 47) have squatter urns, and the separation between the compressed ball and urn is less defined as compared to those on a chair found in southern Maine (fig. 48). The scoring of the cylinders above the seat is handled differently between the chairs, and subtle differences are present in the rear post turnings (figs. 47, 48). As their stretcher alignment reveals, the two chairs are even constructed differently.[24]

An armchair (fig. 49) with rear post and finials identical to the example illustrated in figure 45 demonstrates that craftsmen continued to offer their clients the option of fully turned stretchers as leather chair styles evolved during the first decade of the eighteenth century. The turner of the armchair shown in figure 49 followed the established practice of not differentiating the height of the front leg balusters, which resulted in the stretcher being positioned quite high. Similar turnings can be seen on the armchair illustrated in figure 45, which has a carved stretcher set well above the ground. Proportional idiosyncrasies occurred as makers adjusted to new styles through hands-on experimentation.[25]

New York chairmakers, responding to the demand for Boston chairs, produced their own versions of group D chairs. Although closely resembling their Boston counterparts, the New York chairs have double side stretchers (which were largely abandoned by Boston chairmakers by 1710) and muted balusters above the seat (figs. 50, 51). The finials of the New York side chair illustrated in figure 50 have large compressed spheres that relate more closely to those on the armchair illustrated in figure 34 than those found on Boston seating. The rear post turnings of these New York examples are also similar, although those of the armchair shown in figure 34 have an additional baluster element. Crest height is another feature separating the New York side chair illustrated in figure 50 from contemporaneous and earlier Boston work; the crest rises above the finials rather than being approximately parallel with them. The carver of the New York chair included sinuses in the crest ornament, albeit not very deep or sculpted, but omitted them from the front stretcher (figs. 145, 146). Another New York side chair is almost identical but has a plain crest (fig. 51). As with Boston-made chairs, plain-crested chairs from New York have turned front stretchers—New York chairmakers seemingly eschewed pairs of opposing balusters, embracing instead the rarer Boston front stretcher turning with compressed spheres on either end (figs. 23, 14c, 14d).

Although chairmakers in other port cities attempted to compete with their Boston counterparts, the scarcity of early leather seating made elsewhere suggests that such endeavors met with very limited success. Some patrons may have chosen to purchase chairs from local makers to avoid the risk of damage during shipping or to guarantee that their seating was free from defects before paying, but those consumers probably represented a tiny fraction of the market. The local merchants with whom wealthy New Yorkers did business relied on their Boston counterparts, not only for seating and other goods, but also for knowledge of prevailing fashions. Consignment agreements insured that New York merchants and ship captains had a vested interest in the marketing and sale of Boston leather chairs. Thomas Fitch’s correspondence with Benjamin Faneuil documents tremendous demand. As early as 1706 the former wrote that he “could scarcely comply with those I had promised to go by sloops.” The mass production and export of Boston leather chairs gave the sellers of such seating a tremendous financial advantage, but as Fitch relayed to Faneuil on September 9, 1709, it also occasionally resulted in market saturation. Despite such concerns, it is clear that Fitch and his predecessors in the leather-chair trade had created a strong market, both locally and in New York, and that they were able and willing to adjust prices as needed.[26]

An armchair that descended in the Smith family (fig. 52) and another illustrated in figure 53 represent the apex of Boston design for baroque seating. Although both have standard group D features—finials with conical caps and rear posts with a ring above the baluster—the chairs are distinguished by having arched crests in conjunction with arched front stretchers. The crest rises significantly above the flanking finials, drastically increasing each chair’s vertical stature. To accommodate their lower stretchers, the maker used a larger baluster turning on the top section of the legs to lower the stretcher placement. The front stretcher and crest design of the armchairs and the side chair shown in figure 55 is unique, featuring large abstract leaves that rise from C-scrolls at each corner and meet above confronting C-scrolls in the center; however, the turned stretchers follow the design on the earlier Prescott armchair (fig. 38), and the arm supports are nearly identical to those on the example shown in figure 49. The makers of the Smith chair and the closely related armchair and side chair gave the heels of their rear posts more rake than normal to counter balance their extreme height (figs. 52-55). This is apparent when comparing these chairs with seating from groups A through D.[27]

Unlike the preceding group D chairs with carved crests, those assigned to group E do not have a slot for the leather upholstery. Instead, their crests have an arched reserve to accommodate a face-nailed back panel. A set of chairs bearing the brand of Philip Ver Planck (also Verplanck) (1695–1771) have this feature as well as tapered conical stiles and cylindrical double-scored turnings on the rear posts above the seat (fig. 56). As with other group D chairs. The sinuses are smaller (see fig. 151), and the upper back edges of crest and stretcher piercings are roughly chamfered (figs. 57, 58 [top]). The Ver Planck chairs do, however, have finials similar to those on group D chairs, and their front feet have more definition between the upper and lower sections than those of other Group E chairs (fig. 59 [left]). Philip Ver Planck, who lived in Albany in the 1720s, would likely have inherited these chairs; his immediate ancestors lived in New York City.[28]

Two nearly identical group E armchairs also descended through prominent New York families (figs. 60, 61). The example shown in figure 60, which retains much of its original leather upholstery, is associated with the Van Rensselaer, Schuyler, and Church families. The other armchair belonged to English colonial Gov. Pieter Schuyler (1657–1724) and resided in the ancestral family home at the Flats in Albany until Charles Woolsey Lyon purchased the chair in the early twentieth century (figs. 62, 63). The crest rail ornament on these chairs is slightly more elaborate than that on other group E seating, but both have hallmark group E features: finials capped with a squat cylinder; double-scored lines above the balusters on the rear posts; and somewhat flat carving.[29]

The group E armchair and side chair shown in figures 64–66 are branded “W. MANCIUS” for Wilhelmus Mancius (1738–1808), a doctor in Albany, New York. His father, Rev. George Wilhelmus Mancius (1706–1762), immigrated to New York from the County of Nassau (Germany) in 1730 and was pastor of the Katsbaan Reformed Church in Saugerties, New York, and the (First) Reformed Church in Kingston, New York (fig. 67). Since Rev. Mancius arrived in America after these chairs were fashionable, it is probable that either Rev. Mancius, who married Cornelia Kierstede of Kingston, or Dr. Mancius, who married Anna Ten Eyck of Albany, obtained them through their wives’ families. Both the Kierstedes and Ten Eycks were wealthy enough to afford such a lavish set. Discovered in Yonkers, New York, a fourth Group E armchair has a crest carved by a different hand (see figs. 68, 158) and provides further evidence that these chairs were assembled from components obtained from specialists.[30]

The largest surviving set of group E side chairs descended in the Van Rensselaer family (fig. 69). Although these examples are virtually identical to the Mancius side chairs, variations occur within group E. Some side chairs do not have baluster turnings on their rear posts, and some have crests lacking deeply carved sinuses and overlapping leaves (figs. 70, 71). The earliest occurrence of what became a standard front or medial stretcher for Boston baroque and early Georgian seating is on some group E chairs (fig. 14e). The archetypal component features large, bilaterally symmetrical balusters separated by a small reel (fig. 72). On group E chairs stretchers of that type are joined to the front legs with round mortises, which were easier and quicker to produce than rectangular ones. On earlier leather chairs, round mortise-and-tenon joints were only used to secure turned supports to the underside of arms. Forman speculated that the use of round mortise-and-tenon joints for front stretchers “may have reduced the price of a chair by 1s. or so and saved 14s. on a set of 12 side chairs and 2 armchairs.” He also suggested that “this may explain the shilling or so variation in the cost of chairs billed in the Fitch accounts.” The use of this new stretcher marked a pivotal point in the progression of Boston chair design, representing a variation on the “classic” Boston model that had been popular for at least fifteen years.[31]

At no time before did patrons have such an assortment of seating choices. The group E chairs illustrated in figures 73–78 illustrate a variety of options for crests, stretchers, and arm supports, all of which affected both design and cost. The range of choices was even greater for Georgian framed seating made in Boston between 1730 and 1760, but the system of mass production and mercantilism that insured that city’s dominant role in the manufacture and export of seating in the colonies during that period had been established decades earlier.[32]

In response to the continual influx of English seating furniture, Boston chairmakers began producing different upholstered forms during the 1710s, though most of that seating is stylistically similar to contemporaneous leather chairs. The low-back leather chairs illustrated in figures 79 and 80 are the only Boston examples with crests affixed to the tops of the rear posts rather than between them. The chair illustrated in figure 79 has slightly more complex turnings, but the crests of the two examples are very similar (see figs. 167, 168).[33]