Miniature chest of drawers, attributed to Robert Crosman, Taunton, Massachusetts, 1729. White pine with maple; paint. H. 22 1/2", W. 21", D. 11 1/2." (Private collection; photo, © 2006 Christie’s Images Limited.)

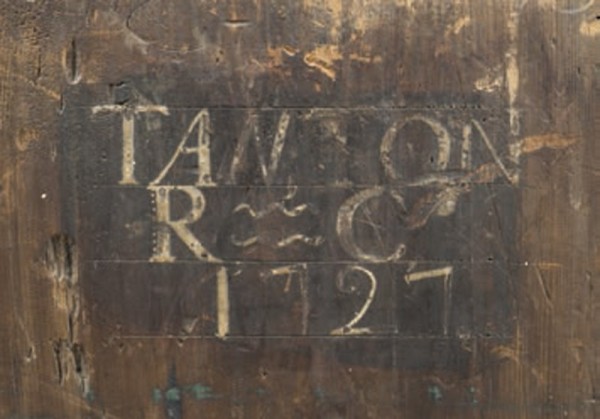

Detail showing the painted inscription on the reverse of the chest illustrated in fig. 1.

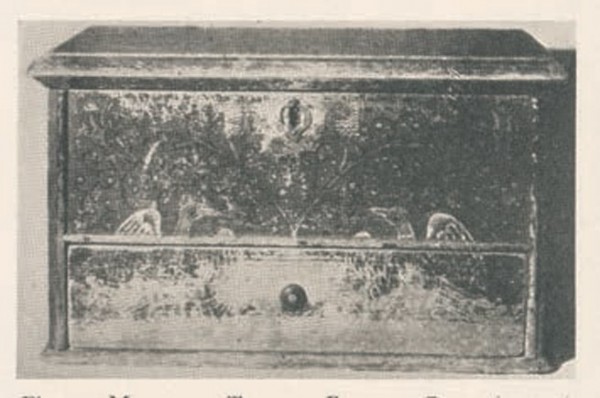

Miniature chest with drawer, attributed to Robert Crosman, Taunton, Massachusetts, 1727. White pine with chestnut; paint. H. 20 1/2", W. 22 5/8*", D. 13." (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Bayou Bend, gift of Miss Ima Hogg, B.57.92.) This is a group A chest.

Chest with drawer, attributed to Robert Crosman, Taunton, Massachusetts, 1729. White pine; paint. H. 32 3/4", W. 35", D. 17". (Courtesy, Currier Museum of Art.) This is a group B chest.

Chest with drawer, attributed to Robert Crosman, Taunton, Massachusetts, 1735. White pine with cedar; paint. H. 32 1/2", W. 35 1/2", D. 17". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Mrs. J. Insley Blair, 1945, 45.78.5.) This is a group C chest.

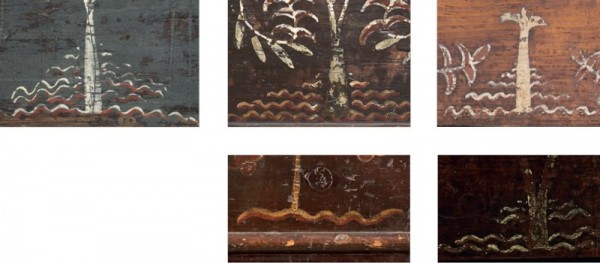

Details of wavy lines (from left to right, top to bottom) on the chests illustrated in cat. nos. 2, 8, 7, 20, 15.

Details of three-berry clusters (from left to right, top to bottom) on the chests illustrated in cat. nos. 2, 9, 8, 1, 13, 22.

Details of tulips (from left to right, top to bottom) on the chests illustrated in cat. nos. 9, 13, 16, 15, 17, 19.

Details of raspberry-type motifs (from left to right, top to bottom) on the chests illustrated in cat. nos. 9, 8, 13, 24.

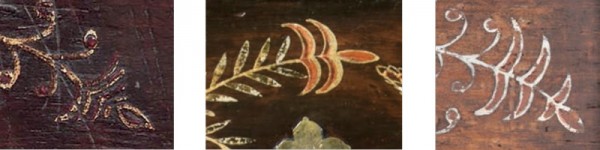

Details of thorn-like leaves (from left to right) on the chests illustrated in cat. nos. 22, 9, 7.

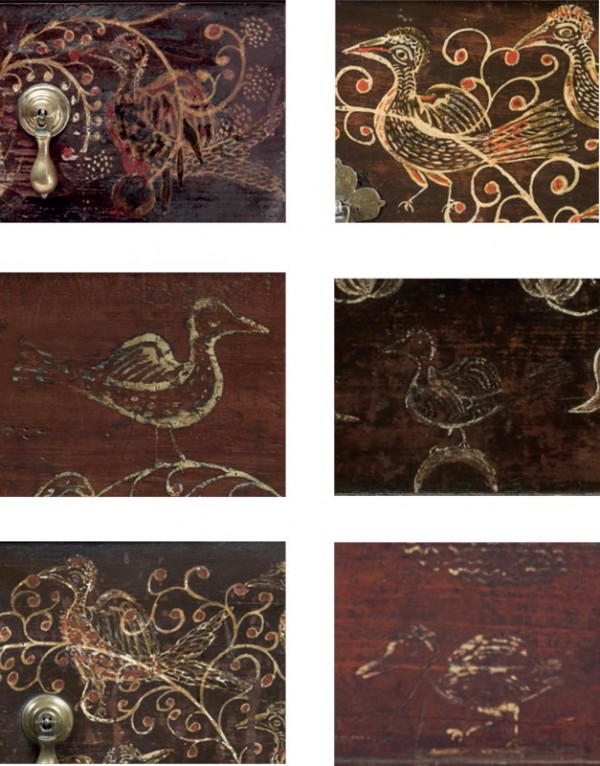

Details of roosting birds (from left to right, top to bottom) on the chests illustrated in cat. nos. 24, 9, 13, 15, 8, 16.

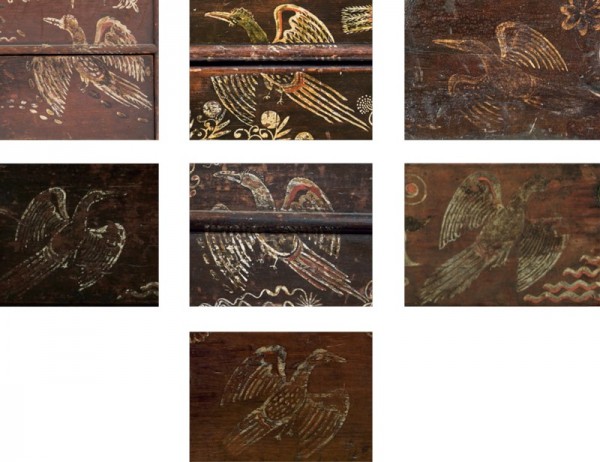

Details of flying birds (from left to right, top to bottom) on the chests illustrated in cat. nos. 25, 9, 17, 15, 8, 19, 13.

Details of branches and berries (from left to right) on the chests illustrated in cat. nos. 2, 1, and 20.

Details of the thorny leaves on the chests illustrated in cat. no. 21 (left) and cat. no. 3 (right).

Digital overlay of the tree and bird motifs on the chest illustrated in cat. no. 9. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing the drawer construction of the chest illustrated in fig. 4. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing the construction of the chest illustrated in cat. no. 7. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing the lock from the chest illustrated in cat. no. 8. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing the reverse of the lock illustrated in figure 18. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inscription on the reverse of the chest illustrated in cat. no. 23. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Robert Crosman, drum, Taunton, Massachusetts, 1740. Oak; paint. H. 18", diam. 15". (Courtesy, Museum of the American Revolution.) This drum has been repainted.

Robert Crosman, drum, Taunton, Massachusetts, 1739. Oak; paint. H. 14 1/4", diam. 16 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Colony History Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This drum has been repainted.

Detail showing the label on the drum illustrated in figure 22. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

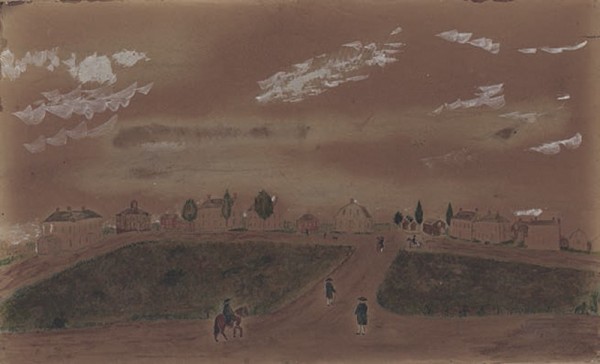

J. S. Howard, Taunton Green in 1790, Taunton, Massachusetts, 1790–1870. Watercolor on

paper. 5 3/5" x 5 1/10". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Photograph of Esther Stevens Brazer, 1940–1945. (Courtesy, Historical Society of Early American Decoration.)

Photograph of Esther Stevens Brazer at work, 1940–1945. (Courtesy, Historical Society of Early American Decoration.)

Photograph of Esther Stevens Brazer (right) with an unidentified subject, 1940–1945. (Courtesy, Historical Society of Early American Decoration.)

Detail of the chest illustrated in fig. 4. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest of drawers, southeastern Massachusetts, 1700–1725. White pine and maple; paint. H. 39 1/2," W. 36" (case), D. 20 1/2" (case). (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the decoration on the chest of drawers illustrated in figure 29. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest of drawers, southeastern Massachusetts, 1700–1725. Pine; paint. H. 41", W. 36 3/4", D. 20 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the decoration on the chest of drawers illustrated in figure 31. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest of drawers, probably Taunton, Massachusetts. 1700–1730. Pine; paint. H. 39 3/4", W. 37", D. 19". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chest has a shipping label for the Taunton Express and is inscribed “WR Atwood, Aurora, Cuyuga County.” William Richmond Atwood was born into an old Taunton family and was related to the Atwoods who owned the chest illustrated in cat. no. 9. He was listed as living in Aurora, N.Y., according to the 1850 Federal Census (Sotheby’s, Property from the Collection of Irvin and Anita Schorsch, New York, January 20–22, 2016, lot 425).

Detail of the vines on the chest of drawers illustrated in fig. 33. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest with drawer, probably Taunton area, Massachusetts, 1700–1725. White pine; paint. H. 21 1/2", W. 18 1/2", D. 43." (Courtesy, Brooklyn Museum of Art.) The crude construction of this chest, which was made without dovetails, sets it apart from the Crosman group; however, the related decoration suggests that Crosman’s designs may have been influenced by an earlier local tradition.

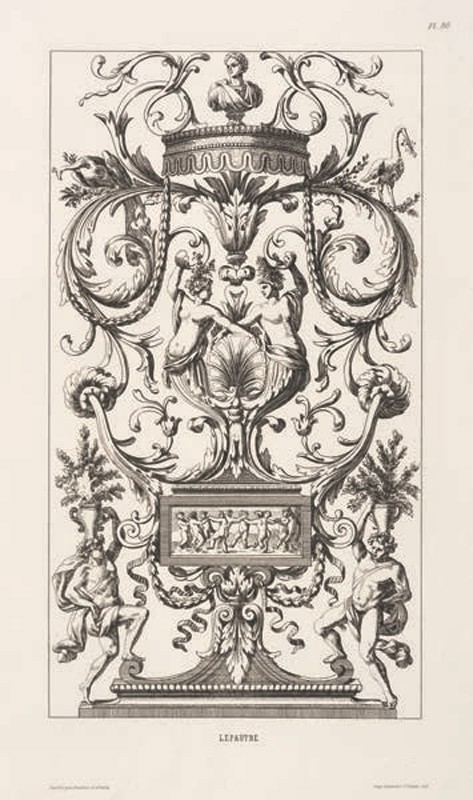

Jean Le Pautre, ornamental design, Paris, 1640–1682. (Jean Le Pautre, Collection des plus belles compositions de Lepautre, gravée par Decloux, architecte, et Doury, peintre [Paris: E. Noblet, 1854]; courtesy, Winterthur Library, Printed Book and Periodical Collection.)

Jean Bérain, design for a lock, Paris 1640–1711. (After Hugues Brisville, Diverses pièces de serruriers, Paris: N. Langlois, ca. 1663, p. 10, recto; courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Page from the design book of Jean Berger, Boston, 1718. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Printer’s ornament, used by James Franklin and Samuel Kneeland, Boston, 1718. (Elizabeth Carroll Reilly, A Dictionary of Colonial American Printer’s Ornaments and Illustrations [Worcester, Mass.: American Antiquarian Society, 1975]; courtesy, Winterthur Library, Printed Book and Periodical Collection.)

High chest of drawers, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1725. Japanned pine with maple. H. 61", W. 40 1/2", D. 22", (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Japanning probably by Nehemiah Partridge.

Bed hanging, Connecticut, 1750–1800. Linen, cotton, and wool. 72 3/4" x 33 1/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

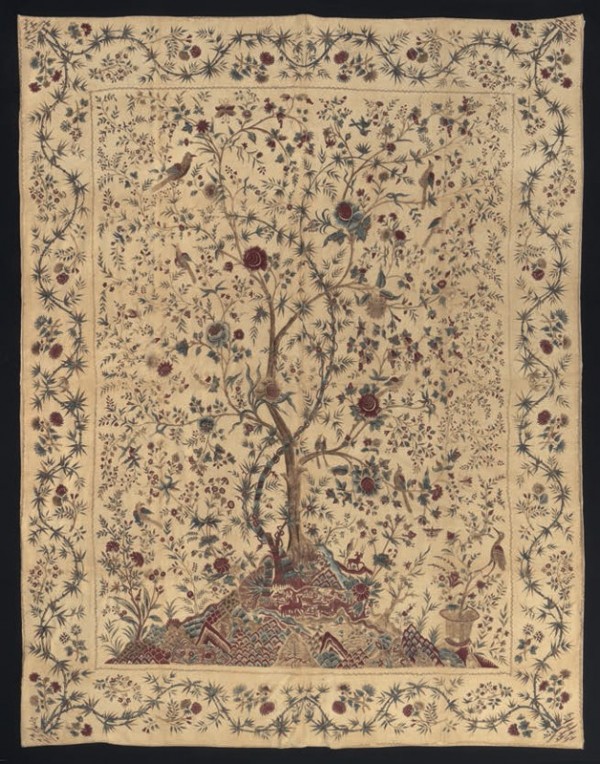

Palampore, India, 1750–1800. Cotton. 105 1/4" x 79 3/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Palampore, India, 1700–1800. Cotton and linen. 111" x 87". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Miniature chest with drawer, attributed to Robert Crosman, Taunton, Massachusetts, 1725–1728. Pine; paint. H. 20 1/2", W. 12 1/2", D. 12 1/2."

Miniature chest with drawer, attributed to Robert Crosman, Taunton, Massachusetts, 1725–1730. Pine; paint. H. 20 3/4", W. 22 1/2", D. 12 3/4."

Miniature chest with drawer, attributed to Robert Crosman, Taunton, Massachusetts, 1725–1730. Pine; paint. H. 21", W. 22 5/8", D. 13."

Miniature chest with drawer, attributed to Robert Crosman, Taunton, Massachusetts, 1725–1730. Pine; paint. H. 20 1/2", W. 22 1/4", D. 12 3/4."

Miniature chest with drawer, probably by Robert Crosman, Taunton, Massachusetts, 1725–1730. Pine; paint. H. 21 1/2", W. 21", D. 12 1/4."

Miniature chest with drawer, attributed to Robert Crosman, 1727. Pine and chestnut; paint. H. 20 1/2", W. 22 5/8", D. 13."

Miniature chest with drawer, attributed to Robert Crosman, Taunton, Massachusetts, 1728. Pine; paint. H. 20 1/2", W. 21", D. 12 1/4."

Chest with drawer, attributed to Robert Crosman, Taunton, Massachusetts, 1729. Pine; paint. H. 32 3/4", W. 35", D. 17."

Chest with drawer, attributed to Robert Crosman, 1729. Pine; paint. H. 32 1/4", W. 35 1/2", D. 17."

Chest with drawer, attributed to Robert Crosman, Taunton, Massachusetts, ca. 1729. Pine, paint. H. 33 7/8", W. 35 7/8", D. 17 1/2."

Chest with drawer, attributed to Robert Crosman, Taunton, Massachusetts, ca. 1729. Pine; paint. H. 32 3/4", W. 38 1/2", D. 18 1/2."

Chest with drawer, attributed to Robert Crosman, Taunton, Massachusetts, 1731. Pine; paint. H. 32 1/2", W. 37 3/4", D. 17 3/4".

Chest with drawer, attributed to Robert Crosman, Taunton, Massachusetts, 1731. Pine; paint. H. 32", W. 35", D. 17 1/4."

Chest with drawer, attributed to Robert Crosman, Taunton, Massachusetts, 1732. Pine; paint. H. 32 1/2", W. 36", D. 17 3/4."

Chest with drawer, attributed to Robert Crosman, Taunton, Massachusetts, 1735. Pine and cedar; paint. H. 32 1/2", W. 35 1/2", D. 17."

Chest with drawer, attributed to Robert Crosman, Taunton, Massachusetts, 1735. Pine; paint. H. 32", W. 35", D. 18."

Chest with drawer, attributed to Robert Crosman, Taunton, Massachusetts, 1736. Pine; paint. H. 31 1/2", W. 37", D. 17 1/2."

Miniature chest with drawer, attributed to Robert Crosman, Taunton, Massachusetts, 1738. Pine; paint. H. 20", W. 21", D. 12 1/2."

Miniature chest with drawers, attributed to Robert Crosman, Taunton, Massachusetts, 1742. Pine, red oak, and chestnut; paint. H. 24", W. 21 3/4", D. 13 1/2."

Chest with drawer, attributed to Robert Crosman, Taunton, Massachusetts, 1725–1730. Pine; paint. H. 32 1/2", W. 38 1/2", 18 1/2."

Chest with drawer, attributed to Robert Crosman, Taunton, Massachusetts, 1726. Pine; paint. H. 18", W. 36", D. 17 1/4."

Chest with drawer, attributed to Robert Crosman, Taunton, Massachusetts, 1727. Pine; paint. H. 32 1/2", W. 37 1/2", D. 16 3/4."

Chest of drawers, attributed to Robert Crosman, Taunton, Massachusetts, 1727. Pine; modern paint. H. 31 1/2", W. 35 3/4", D. 18 3/4."

Miniature chest of drawers, attributed to Robert Crosman, Taunton, Massa-chusetts, 1729. Pine and maple; paint. H. 22 1/2", W. 21", D. 11 1/2."

Box with drawer, attributed to Robert Crosman, Taunton, Massachusetts, 1729–1742. Pine; paint. H. 10", W. 15 3/4", D. 9."

Box with drawer, attributed to Robert Crosman, 1729–1742. Pine; paint. Dimensions unknown

Chest with drawer, attributed to Robert Crosman, 1729–1742. H. 32 1/2", W. 42 1/4", D. 16 1/2."

There are over two dozen examples of “Taunton chests” in museums and private collections throughout the country. Though constructed simply, the chests are intricately decorated, featuring expressive painted designs that range from single trees of life to complex compositions of multiple trees, birds, vines, berries, and blossoms. Due to the early work of pioneering scholar Esther Stevens Brazer (1898–1945), these objects have historically been attributed to Robert Crosman (1707–1799), a drum maker and member of a family of craftsmen working in the town of Taunton, Massachusetts, from approximately 1726 to 1742. Since the publication of Brazer’s seminal article, “The Tantalizing Chests of Taunton,” several scholars have conducted research on and provided further analysis of the chests, but an extensive consideration of the entire group has never been published. As a result, neither Brazer’s original findings nor her Colonial Revival viewpoint has been fully assessed. This article will address several questions about the chests, most notably: was Brazer correct in her attribution to Robert Crosman? Is there now further evidence to strengthen or refute her claims? Who was Esther Stevens Brazer, and how might elements of her personal and cultural circumstances have influenced her scholarship and our subsequent understanding of the Taunton group? Finally, how can the chests’ changing interpretations over time inform our own present-day understanding of these objects’ importance?[1]

Renewing the Case for Robert Crosman

Beginning in 1925 Esther Stevens Brazer was, to use her own word, “haunted” by a paint-decorated chest of drawers bearing the inscription “TaunTon/R.C./1729” (figs. 1, 2). First exhibited by dealer Herbert Lawton at Boston’s Park Square, that object was the catalyst for the research that culminated in her 1933 article. In that publication, Brazer catalogued eleven similarly painted chests and asserted that Robert Crosman was their maker. Although sixteen examples have been discovered since Brazer published her article, “The Tantalizing Chests of Taunton” has served as the essential text on Crosman and his work for more than eighty years. Given this expanded number of chests and their various decorative compositions, one might now speculate that the Taunton group represents the work of multiple painters or even a regional school. Further, Brazer’s attribution to Crosman might initially appear problematic, since she based it on the initials painted on a single chest and was able to identify him solely as a drum maker. However, new research on Crosman, coupled with a comprehensive study of the entire Taunton group, strengthens the claim that he was the primary maker, possibly aided by one or more workers in his shop. Within this context, compositional variations in the decoration of Taunton chests provide a striking counter-point to the notion that rural designs evolved slowly.[2]

Decoration

Decorative similarities and divergences are most apparent when the chests are divided into three groups. Group A consists of a series of miniature chests featuring a single tree of life, occasionally accompanied by two smaller trees on a drawer below (fig. 3). Flowers and foliage are typically absent or minimal, with branches terminating in small red berries. In two cases, small chicks appear. In contrast to these plainer compositions, group B chests have a profusion of trees of life bursting into bloom (fig. 4). Though the trees are still distinct from one another, their sheer number creates a sense of overflowing abundance. The depiction of several different types of foliage, fruit, and flowers adds to this baroque effect. In addition, these compositions feature as many as twelve different birds. Some are standing, some roost in trees, and some are depicted in flight. The chests in group C are markedly different, featuring elegant, scrolled vines terminating in tulips. These designs cross over the drawer dividers to encompass the full surface of the chests (fig. 5). The remaining chests attributed to Crosman, classified for convenience as group D, are connected only in so far as each of the examples seems to defy categorization, representing a range of compositions that depict birds, berries, and trees in various combinations.[3]

On the basis of composition alone, it is tempting to propose that each group represents a different hand; however, the occurrence of virtually identical motifs and details throughout the entire body of Taunton work supports Brazer’s interpretation that these chests are from the same shop. For instance, similarly executed wavy lines are typically found at the base of each tree or vine (fig. 6). The ends of small branches curve delicately

inwards to terminate in little red berries, often forming characteristic clusters of three (fig. 7). Wherever an overall composition appears to advance new visual ideas distinct from other examples, details provide links to the larger body of work. The chest illustrated in figure 4 provides one example. It has an early iteration of the tulip motif, connecting the furniture in group B to that in group C (fig. 8). A raspberry-like feature, consisting of a cluster of white dots (fig. 9), appears on two group B chests (cat. nos. 8, 9), the signed and dated example from group D (cat. no. 24), and a chest in group C (cat. no. 12). Similarly, thorn-like clusters of triple-lobed leaves terminate branches of certain chests from groups A, B, and D (fig. 10). Comparable bird motifs link all four of the Taunton groups, as demonstrated by the chicks on two group A chests (cat. nos. 2 , 7) and the roosting birds on some group B, C, and D examples (fig. 11). Pairs of adult birds flying in profile appear across almost all of the chests in groups B and C as well as some in group D (fig. 12).

Despite these similarities, it is possible that at least one additional painter worked in Crosman’s shop. A miniature chest that descended in his family (cat. no. 1) has characteristic motifs, but the composition is simple and the painting is executed with less competence than that on other chests in the Taunton group. Most of the decoration attributed to Crosman is more controlled and, in some areas, almost Byzantine in its complexity (fig. 13, cat. nos. 2, 8). Brazer felt that the Crosman family chest was done early in his career, possibly while he was still learning his trade. Although that interpretation remains plausible, there is no physical or documentary evidence that the chest predates other pieces in the group. An alternative explanation is that an apprentice or journeyman decorated the chest. In either case, the full, rounded berries and wavy line at the base of the tree link that object to other pieces in the group (fig. 13).

The chest illustrated in catalogue number 21 is dated 1726, when Crosman was only nineteen years old and was possibly still serving his apprenticeship. The motifs are similar to those on the chests illustrated in catalogue numbers 3, 5, 8, and 9, but some of the execution appears rudimentary by comparison (fig. 14). This discrepancy could indicate that Crosman’s skills were still developing, as may be the case with the family chest, or, more likely, it could signify the work of a collaborative hand.[4]

The methods and materials used to decorate Taunton chests are consistent within the group. Analytical work done on four chests (cat. nos. 3, 19, 22, 24) indicates that the decorator first applied a reddish-brown, iron-based wash. The binder for the wash tested positive for protein, the source of which could have been animal hide or bone glue—or less likely, blood—all materials that a rural maker could easily have accessed. Pigments found on the chests include lead white, vermillion (cat. nos. 2, 19, 24), and copper (probably verdigris) (cat. nos. 19, 24). As noted in the analytical reports, the presence of azurite, used on the eyes of the birds in catalogue number 24, is somewhat surprising; many artists of the period had switched to Prussian blue, which was first synthesized in 1704. Further, the painter’s decision to bind the azurite in oil, rather than protein, is atypical, as this combination was known to cause the color to darken. In each of these senses, then, the use of azurite suggests a gap in technical knowledge as well as limited access to new materials, factors that are consistent with the early rural colonial context.[5]

Taunton chests provide limited evidence of the painter’s work methods. For group C chests, the decorator clearly used a compass to lay out many of the scrolls and circles (see cat. nos. 9, 13, 15, 16, 19); indeed, his reliance on that tool may account for the regularity of design and elegance of this particular subset. Under-drawing in the form of scribed lines is visible on several chests (see cat. nos. 13, 15, 19) and is probably present on others. This technique may have been confined to the most elaborate examples. The miniature chests, with their often irregular and asymmetrical tree branches and berries, appear to have been painted freehand, perhaps because the relative simplicity of their designs allowed for an easier, spontaneous execution (see cat. no. 3). Digital overlays suggest that patterns were used sparingly (fig. 15). Some of the flanking birds are similar enough to have had their basic designs transferred with a pattern, but no two birds are identical; all have elements that were painted freehand. As was the case for virtually every period craftsman, Crosman’s work habits, attained through apprenticeship and made instinctive through repetition, allowed him to recreate similar designs.[6]

Construction

The construction of Taunton chests provides compelling evidence that all are from the same shop if not made by the same hand. As other scholars have noted, the use of small wooden pins to attach the drawer bottoms to the drawer sides is one of the more idiosyncratic features (fig. 16). All of the original drawers on large chests examined for this study exhibit this distinctive pin placement. Of the smaller chests, only catalogue numbers 17, 19, 24, and 25 have side-pinned drawers. Pinning would not have been as critical for small drawers because they were not intended to support as much weight.[7]

Other construction elements are consistent among Taunton chests. Shared features include shallow rabbeted joints on the four primary boards of the case; rough backboards attached with large wrought nails; three to four dovetails at the front and back of each drawer (typically smaller in the back); drawer bottoms set into dadoes at the front and nailed at the back; the use of two nails driven through each side to affix the chest bottom; and, for the majority of the chests, a large wooden pin driven through each side to attach the lower rail (fig. 17). Chests of the same format also display similar dimensions: larger format examples are approximately 32" high, 35–37" wide, and 17" deep; smaller chests are approximately 20" high, 21" wide, and 12" deep. Some chests have scored assembly marks in the form of Roman numerals on the carcass and drawers, and those with original pulls and escutcheons have similar hardware. The locks appear to have been made locally, possibly by the same blacksmith. The locks installed on the chests shown in catalogue numbers 8 and 14 are marked “FC” on the rear (figs. 18, 19).[8]

Structural interrelationships within the Taunton group suggest that all the chests were made and decorated in the same shop. Although in urban areas furniture makers often contracted painting, japanning, and gilding to specialists, in rural settings such divisions of labor would have been unusual. The most plausible conclusion relative to the Taunton group is that the primary painter and woodworker were probably the same man.[9]

Attribution

Before settling on Robert Crosman as the most likely maker, Brazer identified a total of five individuals with the initials RC living in the Taunton area during the chests’ period of manufacture. More recent research expands her list, adding the names of Robert Claffin of Attleboro, who died in 1753; Richard Collins of Freetown, who died in 1753; Richard Church Jr. of -Rochester, who died in 1772; Ruth Campbell of Taunton; and Rebeckah Cobb of Taunton. None of those men ever lived in Taunton, however, and it is unlikely that Campbell and Cobb were cabinetmakers given their gender. There is also no evidence that either woman was an ornamental painter. Although Brazer felt that the initials RC on the chest illustrated in figure 1 referred to the decorator, it was common practice for patrons to have objects emblazoned with their own initials and dates, particularly in commemoration of important events. No major occurrences in Ruth Campbell’s life are known to have aligned with the 1729 date on the RC chest, but Rebeckah Cobb did marry in that year.[10]

In spite of possible alternatives, new evidence reasserts Brazer's attribution to Robert Crosman as the most likely explanation for the "RC" inscription. A recently discovered chest of drawers inscribed “TANTON RC 1727” (cat. no. 23) refutes the notion that the initials and dates on it and on the miniature example shown in figure 1 are those of patrons. Although the painted decoration on the chest is modern, that object has side-pinned drawer bottoms and scored assembly marks like others in the Taunton group. The inscription relates closely to that on the 1729 example, especially in terms of the numeric forms, serifs of the “T”s, wavy lines, and dotted borders (fig. 20). The existence of two chests marked “RC,” both inscribed on the back rather than the front as in the case of all other initialed Taunton chests, strengthens Brazer’s argument that “RC,” and by extension Robert Crosman, was their maker.

Crosman was documented as a drum maker long before Brazer published her article, and she cited his trade and upbringing “in an atmosphere of craftsmanship” to support her theory that he was the maker of the chests. Many members of his family were tradesmen; his great-grandfather Robert (d. 1692) was a drum maker, carpenter, and gunsmith who helped build the Taunton ironworks; his grandfather Robert (1657–1738) was a drum maker, carpenter, and miller; his great-uncle Samuel (1667–1755) and second cousins Thomas (1694–1765) and Gabriel (1702–ca. 1763) were carpenters and joiners; and his father-in-law, Henri Gachet (1676–1737/8), was a shipwright. Crosman’s father, Nathaniel, has traditionally been described as a miller, but a recently discovered entry from a local constable’s notebook indicates that he was also a furniture maker. On October 24, 1709, Nathaniel agreed to make Rebeckah Walker “a ches of draws woth 3 pound.” Although previous scholars have suggested that Crosman apprenticed under Gachet, the former also had opportunities to learn woodworking within his immediate family.[11]

Newly discovered documentation also indicates that Robert Crosman was a furniture maker. Entries in the account book of Taunton attorney Samuel White reveal that Crosman made the former a table on February 6, 1731; a trundle bedstead in February 1740; a chair the following June; a small chest in 1745; and a “writing desk” in 1747. Other woodworking performed by Crosman included “mending . . . of my desk” in March 1737; “making two casements” in 1740; making a wheel and “making a fork handle and putting a tooth to the rake” in 1741; and “making a cheese press” in 1745. Another entry shows that White provided Crosman with a variety of goods, including a “bottle of linseed oil and colors,” indicating that the craftsman was acquiring ingredients to mix his own paints. References pertaining to drum-making also appear among the same pages—including Crosman’s acquisition of calf-skin, drum rims, and nails—confirming that he was working as a furniture maker, drum maker, and carpenter.[12]

A chest dated 1742 (cat. no. 19) has drawer bottoms made of very thin, flat-sawn oak, suggesting that the maker may have been constructing drums and furniture simultaneously. Although not present in other Taunton chests, oak was used to make two contemporaneous drums signed by Crosman (figs. 21-23). Measuring approximately one-quarter-inch thick, the drawer bottoms of the 1742 chest were probably cut in the maker’s shop, most likely with a frame-saw fitted with a fence and manipulated by two men. Black oxidation stains around the nail-heads in the bottom boards reveal that the wood was wet at the time of assembly. Because it could be bent, thin wet oak was perfectly suited to form the round bodies of drums; however, that material was not necessary to construct chests. The thickness of the oak used on the chest is roughly the same as that of the 1740 drum, suggesting that the maker of the former object may have used stock intended for drum work.[13]

Robert Crosman’s World

The Crosman family’s relative stability within their time and place provides a context for the chest maker’s exuberant painting. As one of New England’s oldest settlements, Taunton was almost seventy years old when Robert Crosman was born (fig. 24). Though governed under the jurisdiction of Plymouth Colony, Taunton was officially settled in the mid-seventeenth century by a group of Puritans from Dorchester in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Perhaps feeling hemmed in during the population increases of the Great Migration, the forty-six original Taunton purchasers arrived from Dorchester in the late 1630s, settling in the area previously known by native populations as Tetiquet and Cohannet. The strategic location at the confluence of the Taunton and Mill Rivers, situated between Boston and Newport, was attractive to these English colonists for good reason: in the coming years, the waterways would ensure the community’s success as a regional transport and industrial center, spawning early ironworks and shipyards. Also in the town’s early days, an abundance of fresh, flowing water facilitated farming, fishing, and the establishment of a sawmill and gristmill. The Taunton River’s course, which proceeds down through southeastern Massachusetts and into Rhode Island’s Mt. Hope Bay, facilitated connections to Newport, while the fifty-mile ride to Boston overland provided a link to New England’s most important urban center and its networks of international trade. As local colonists laid claim to more and more land, conflicts with native populations, especially King Philip’s War, may have slowed but did not prevent growth and expansion in Taunton. From 1675 to 1765, during the prime of Robert Crosman’s grandfather’s life through that of his own, the number of houses in Taunton grew from 150 to almost 400, even as additional towns such as Norton and Dighton broke off to form their own communities.[14]

Within this environment, the Crosmans became an established family of artisans cum businessmen. The chest maker’s great-grandfather Robert (d. 1692) was one of the original Taunton settlers and may have come over from England with his father, John. Robert II (1657–1738) served as both a town selectman and a representative at the Massachusetts General Court. He acquired the local gristmill, built a large house beside it on present-day Cohannet Street, and obtained a license to operate a tavern there. His successes seem to have given him a measure of power within the community. In 1687/8 Robert II was listed among local residents who enticed the Reverend Samuel Danforth, a member of the vaunted clerical family, to take over the Taunton parish. When Robert II died, an obituary in a Boston newspaper praised him as “a religious and useful Man, and a true lover of his Country” as well as “the first Attorney in the County of Bristol” who “served his Town faithfully.”[15]

Less is known about Robert II’s son, Nathaniel Crosman (d. 1757). He continued to run the mill purchased by his father and amassed an estate that included about eighty-five acres of land. His son Robert took over operation of the family mill as well as the tavern in the Cohannet Street house established by his grandfather. Although at least twenty-seven chests attributed to Robert III’s shop survive, he seems to have abandoned furniture making and painting as he grew older, possibly because milling and inn-keeping proved more stable and profitable. As was the case with many rural New Englanders, Crosman maintained numerous sources of income. This approach seems to have served him well. He died in 1799 at the age of ninety-two and left a comfortable estate. Among the more valuable items listed in his inventory are an eight-day clock, a high chest of drawers, a desk, and a riding carriage. A list of outstanding loans to various townspeople indicates that Crosman had liquidity to spare and was engaged with his community. He owned over eighty acres of land, with his total estate valued at about $3,000. Although this would not have placed him among the very wealthiest of Taunton’s residents, Crosman’s inventory attests to the degree of stability that he and his forebears had achieved over the course of four or five generations in the New World.[16]

Crosman’s financial security and position within an established family of artisans and businessmen may have afforded him greater creative freedom than that experienced by the typical rural craftsman. Many scholars have emphasized the conservatism of rural design and shown how that tendency reflected limited access to new fashions and restrictions imposed by the agrarian cycle; but as Philip Zea cautions, there is danger in oversimplification. Delighting the eye with their inventiveness, the chests attributed to Crosman attest to the kind of originality that was achievable within the strictures of the rural lifestyle. The Taunton group demands a nuanced definition of rural conservatism, one that allows ample room for creativity and experimentation even within a limited stylistic vocabulary.[17]

Esther Stevens Brazer and the Re-Reading of Taunton Chests

While Brazer’s scholarship remains essential to understanding the eighteenth-century history of Taunton chests, her work also shows how the interpretations of early twentieth-century antiquarians were influenced by their backgrounds, time, and place. In particular, her biography reveals proclivities that infused her perspective with themes of story-telling, inheritance, mysticism, and romance. Considering these factors can help explain why “The Tantalizing Chests of Taunton,” even in the absence of key pieces of evidence, focuses almost solely on authorship, privileging the craftsman’s story over that of the chests’ consumers and their relationship to their possessions.

Understanding Brazer requires insight into the historical context in which she built her career. As recounted in the work of scholars such as Elizabeth Stillinger, Briann Greenfield, Michael Kammen, and Richard Saunders, Americans began collecting and studying antiques in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, largely as a way of telling stories about their past. As a relatively young nation, the United States experienced a sense of deficiency in relation to the storied countries of Europe. As early as 1854, George Templeton Strong wrote that “we are so young a people that we feel the want of nationality . . . we have not, like England and France, centuries of achievements to look back on: we have no record of Americanism and we feel its want.” People turned to American antiques as a way of constructing a national history and a sense of national pride. Celebrating political heroes, while simultaneously telling stories of intense hardship endured by the early settlers, Americans developed a narrative to justify their country’s worthiness. As written in Harper’s Weekly in response to the 1889 George Washington Exhibition, “we treasure the relics of illustrious men . . . [because] their acts [seem] less tangible than the material objects they have left behind them.” In addition to the adulation of objects ostensibly owned or touched by great men, the passing down of family antiques became a meaningful activity for Americans in search of a more deeply rooted past. In particular, members of elite “old” families praised the pure beauty of American antiques as evidence of their forebears’ superiority, adding to a gathering sense of nostalgia for times past that was pervading aspects of popular culture, especially among certain segments of society. In addition to the waves of new immigrants perceived as a threat to white Anglo-Saxon Protestant supremacy, multiple other factors—such as the rise of increased industrial production, electricity, and motor vehicles—contributed to a general sense of American malaise. An appreciation of pre-industrial craftsmanship, advocated by the Arts and Crafts movement and applied to the collecting of Americana, offered succor to those suffering from the strains of an increasingly fast-paced modern life.[18]

Although the seeds of an antiquarian movement had sprouted first in the nineteenth century, the 1920s marked a period of particularly vigorous interest in American antiques. The marketplace, once perceived as comprising an eccentric band of scavengers raiding country attics, evolved into a sophisticated forum for the expression of elite tastes, with members of the nation’s most privileged and educated classes incorporating Americana into their homes and vying for top prizes at auction. By the end of the decade record-setting sales, such as the 1929 auction of Howard Reifsnyder’s Philadelphia high chest for a staggering $44,000, provided evidence of a full-blown market frenzy. One of the driving forces behind these developments was a shift in collectors’ priorities. While earlier interest in Americana focused on the associational aspects of objects as relics of patriotic history, collectors increasingly became more appreciative of the aesthetics of antiques. The development of a scholarly historiography facilitated a more nuanced understanding of styles while also identifying some of the Colonial period’s major craftsmen, an area of research that collectors and researchers found more and more compelling. “The cult of the craftsman,” as Briann Greenfield has termed this development, had narrative appeal that could match collectors’ earlier interest in story-telling and provided scholars with practical research goals. In an approach similar to pre-existing art historical models, researchers had ample material from which to construct “Berenonsian-style” lists of attributions and to celebrate artistic virtuosity, proliferating a preoccupation with the single master craftsman that would extend through the twentieth century and even into the twenty-first.[19]

At the same time, according to Stillinger, the rise of Darwinism offered collectors and museum professionals a framework in which to organize their holdings, encouraging the interpretation of objects in terms of evolutionary progression, both genealogical and cultural. The idea of “folk art” also gained traction on the American art scene at this time, with exhibitions such as Holger Cahill’s The Art of the Common Man (1932) adding momentum to an appreciation of seemingly humbler objects, such as rural painted furniture, that fell outside the high-style craftsmanship traditions typically associated with urban centers and the elite. Women played an active role in each of these developments, with key figures such as Colonial historian Alice Morse Earle, folk art dealer Edith Halpert, and collector and Metropolitan Museum of Art patron Natalie K. Blair advancing the Americana field through various means.[20]

This atmosphere provided a fertile ground for the successes of Esther Stevens Brazer (figs. 25-27). Accordingly, the themes of the Colonial Revival era are very much present in both her work and her approach to her personal life. Born in Portland, Maine, in 1898, Brazer died young in 1945, but she achieved much during her short life: a combination of her strong personality and the surging popularity of her areas of interest soon resulted in a rise to the top of her field. Over the course of approximately twenty-three years, Brazer published extensively, producing at least one article for Antiques on an almost annual basis. Her writing focused mostly on themes of decorative painting during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, including regional traditions of Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire, and extending across a variety of forms, from furniture to toleware. Combining her various stores of knowledge, Brazer’s most substantial work was an extensively researched book, Early American Decoration, which provided readers with historical background as well as practical expertise in decorative painting and restoration. Her scholarship was well received. A historic advertisement refers to Early American Decoration as “the most beautiful and scarce work of its kind . . . a limited edition of the magnificent and monumental work . . . hailed by collectors, dealers and museums as a priceless reference book and a landmark in the art of early design and its restoration.” On a general reputational level, sources from Brazer’s lifetime celebrated her as “clever” and even “famous,” with one article declaring her to be “probably the Nation’s outstanding authority on the discovery, restoration and reproduction of early American painted designs and stencils on home furnishing.” In addition to her accomplishments as a scholar, decorator, and restorer, Brazer was beloved as a teacher of ornamental painting techniques, prompting a number of her students to form the Esther Stevens Brazer Guild (now known and still operating as the Historical Society of Early American Decoration) upon the author’s early death in 1945. Throughout her life she was also a collector of American antiques, and some of her more passionate writing stems from her personal connection to the objects—including historic houses and furnishings, among them a small Taunton chest—that she owned during her lifetime.[21]

The strong voice behind Brazer’s autobiographical papers provides a revealing view into some of her personal values, exposing themes that would also work their way into her scholarship. In interviews and writings, Brazer framed her life as a story of artistic inheritance, a construction that would have fit comfortably into the genealogically determinist tendencies of the Colonial Revival period. She made regular reference to an aunt and a great-grandmother as possible sources for her artistic talents and for the solace she took from them. Her aunt is said to have been an academically trained painter who exhibited in Paris; her great-grandmother “painted charming Victorian flower arrangements with hummingbirds and ribbons . . . . When she wanted peace from her children, she retreated to her bedroom, pulled a bureau across the door and painted.” In later years Brazer also spoke wonderingly of a connection to an ancestor in the tin-painting trade, great-great-grandfather Zachariah Stevens: “perhaps this inheritance is responsible for the pride I take in matching the skill of old-time craftsmen.” The ideas of tradition and legacy played key roles in Brazer’s conception not only of her talents but also of her profession’s importance. In Early American Decoration, she wrote reverently of the need to inspect objects carefully for overpainted designs, “for within our grasp we may hold a precious inheritance which demands our recording.”[22]

An additional narrative thread in Brazer’s autobiographical and scholarly material employs popular themes of romance and mysticism in framing discussions of the past. In reflecting on her work, Brazer used language to emphasize the spiritual connection she felt with history and historical objects, going so far as to credit such emotions with improving her restoration results. Writing of her last residence, a historic home in Flushing, New York, known as Innerwyck, she mused: “I would not know myself if I did not have an old house to live in and feel with to recreate artistic rooms in the old styles I know so well. It seems to me that I can better restore a piece when I work here in this house surrounded by antiques which have lived through the years that made history.” Such sentiments reflect the popular late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century belief, advanced by advocates of the Arts and Crafts movement, that properly designed interiors could elevate the individuals who inhabited them. Brazer extended her thrill in mystical ideas to her interactions with particular antiques, envisioning a fantastical link between an object’s past and present and cautioning against the destruction of such connections. “I like to think that the invisible spirit of the first purchaser hovers about old furniture. But I am afraid that a lot of great-grandmother spirits have sadly turned away and wanted to forsake some of their dear old chairs, because of the obliterating coats of paint which they have received.” The writer also had her horoscope cast and kept a coded diary, now lost, in which she made daily entries “in strange triangles and symbols each apparently standing for a letter in a word.” Brazer continued to weave references to the uncanny into her work until late in her career, writing in Early American Decoration of a “sixth sense” about an object’s authenticity, developed by her longstanding handling of antiques.[23]

Brazer’s unabashed romantic sensibility, the value she placed on inheritance, and her love of story-telling were all characteristic of the time and place in which she lived and all surfaced regularly in her work. The many scholarly merits of her research notwithstanding, Brazer’s article on Taunton chests is no exception. From the outset of the article the author evokes a connection between herself and the object that is both emotional and spiritual in nature, writing of her first discovery of Taunton chests and the way that the “RC” initials “kept haunting” her. She justified her attribution of “RC” as the painter rather than the owner of the objects through an -unexplained visual instinct and an uncanny emotional understanding of the maker’s work: “Somehow, that painted label seems to express a certain pride . . . .” She even admits to her own irrationality in this instance, conceding that “I recognized that the “RC” might stand for the owner . . . but I preferred the alternative.” In each of these ways, Brazer infused her work with a sense of romanticism and nostalgia, themes that helped drive the Americana-collecting movement forward but that also have sometimes obscured the original intentions behind eighteenth-century objects. As a case in point, in her article on Taunton chests, Brazer barely touches upon the chests’ original function and offers few indications of how eighteenth-century viewers might have read these objects.[24]

Eighteenth-Century Perspectives

What did eighteenth-century viewers see when they looked at a Taunton chest? Brazer’s one suggestion regarding the objects’ original function was that they were made for young women at the time of their marriages. Subsequent scholars have agreed, pointing to correlations between some of the inscribed examples and the marriage dates and initials of girls living in Taunton, especially those with Crosman family connections. Crosman’s expansive, kinetic compositions are certainly celebratory in character; the motifs of chicks, sometimes accompanied by adult birds, and blossoming vines are traditional symbols of fertility and family that were considered essential to a successful eighteenth-century marriage (fig. 28).[25]

Another possible metaphorical reading is that the chests expressed a desire to create order out of disorder. It is easy to imagine why such a visual idea would have been compelling to settlers positioned on the edge of a new continent. Citing contemporary writers such as Samuel Sewall, historian Roderick Nash has noted the preoccupation with the evils of wilderness for the early New Englander, from both a physical and spiritual perspective. Arriving in Massachusetts in 1620, William Bradford famously proclaimed the place “a hideous and desolate wilderness, full of wild beasts and wild men.” As Laurel Thatcher Ulrich has suggested, under such circumstances, to construct a case piece was a psychologically powerful act, “[asserting] permanency, stability and power in a world where Indians, witches, and illness lurked.” Although eighteenth-century Taunton was no longer situated in the wilderness, the fears of older generations may have endured and become manifest in local visual culture. Painted with images of an idyllic, fruitful garden, Taunton chests would have evoked innumerable biblical references while affirming their owners’ need to maintain a sheltered space in which their families could prosper. Vines stretch out across the surface of the chests with a disregard for boundaries in the same way that Old Colony settlers dispersed into new areas of land in southeastern Massachusetts around Robert Crosman’s time. Particularly with respect to the chests in group C, the inherent movement of the motifs is brought into harmony by the symmetry of the composition and the careful measurements of the compass, pulling visual ideas of growth and activity into a controlled, comfortable balance that would have helped to assuage eighteenth-century concerns about the unpredictability or hostility of nature.[26]

In each of these senses, the chests were operating as indicators of abundance, brought on by domestic and spiritual harmony. Most likely positioned within public spaces of a house, the chests would have carried this meaning not only for the householders but also for their guests, associating the owners with a vision of an ordered and fruitful family in keeping with the community’s highly religious way of life. These meanings, however, do not preclude an additional, worldlier significance. To the local eighteenth-century eye, Taunton chests would have had a dazzling and sophisticated aesthetic appeal. This is especially true within the context of local interiors, which, as inventories reveal, were considerably more modest than those in larger towns and cities. An elaborately painted chest would have stood out impressively, serving as an indicator of the householders’ appreciation for, and ability to indulge in, items of beauty and luxury.

This is not to suggest that the settings for these objects were stark or unadorned. Bristol County households included visual points of reference for the designs Crosman employed. Painted chests by other makers and decorators active in southeastern Massachusetts, some of which predate his work, have analogous motifs, including undulating vines and small trees that spring from central mounds and sprout into various blossoms and pointy leaves (figs. 29, 30). One example incorporates birds and vines, with a flower composed of dots on the backboard (figs. 31, 32). On an early chest of drawers connected to Taunton, the painted decoration crosses over the drawer dividers as it does in some examples of Crosman’s work (figs. 33, 34). Although the composition and brush-work of the chest of drawers is less refined than that associated with Crosman, the vines that meander across the surface, the triple-lobed leaves, and the clusters of berries at the ends of branches all recall motifs on pieces from the Taunton group. The chest of drawers also has small wrought nails in the same positions as the pins used to secure the drawer bottoms to the drawer sides on many chests attributed to Crosman’s shop. Although it is impossible to determine if there was a direct connection between the maker of the chest of drawers and Crosman, it is possible that the former object was an antecedent of the latter. Among consumers, a taste for elaborately painted furniture was well established in Massachusetts and coastal Connecticut more than a decade before Crosman began working. This is evident from the aforementioned objects and a blanket chest that, although differently constructed and crudely painted, has decoration similar to Crosman’s (fig. 35).

For some eighteenth-century observers, Crosman’s decoration would have been understood in the context of international style. In particular, his work broadly reflects the history of French ornamental design, made popular across Europe and England in the seventeenth century by the far-reaching cultural influence of Louis XIV’s court. Driven into a frenzy of production by the king’s insatiable appetite for beauty, France’s designers and craftsmen created a panoply of ornamental designs to adorn the walls and furnishings of royal and elite interiors. In the grotesques of royal designers such as Jean Le Pautre (1618–1682) and Jean Bérain (1640–1711), networks of scrolling vines spread out across the page, interspersed with whimsical birds and other creatures, berries, flowers, and foliate forms (figs. 36, 37). Daniel Marot (1661–1752), primary designer to William III, was among the many Huguenot craftsmen who sought refuge abroad, bringing French ornamental designs and technology to England. By the mid-1720s, when Crosman began his career as a furniture maker and decorator, French baroque designs had permeated the material culture of England and her colonies. One of the first painters to work in that style in America was Jean Berger, a Lyonnais immigrant who probably arrived in Boston around 1709. His 1718 drawing book includes designs for japanning as well as ornamental painting in the French baroque taste (fig. 38). Crosman’s designs are far less complex and less diverse than those of court artists and Berger, but common underlying structures are apparent in their work.[27]

Crosman was well within reach of sophisticated baroque designs. Although ostensibly a country town, Taunton’s status as a regional riverine hub ensured the regular comings and goings of tradesmen carrying a variety of imported goods from nearby urban centers, including books and prints adorned with contemporary ornament (fig. 39). River-going vessels themselves could have provided a source of inspiration, especially since Taunton was a shipbuilding center. Craftsmen employed by that industry included ornamental painters who decorated the hulls and interiors of ships. Taunton was also within the stylistic sphere of Boston, London’s surrogate city in the colonies and the center of the japanning trade there. Although Crosman did not employ chinoiserie motifs like those commonly found on japanned furniture, he may have been influenced by the use of brilliantly painted and gilded decoration like that on the Boston high chest illustrated in figure 40.

Textiles may have been the most direct source for Crosman’s decorative work. As a number of scholars have noted, his motifs resemble those on eighteenth-century crewel-work embroideries (fig. 41), which often feature a tree of life rising from a mound. Likely inspired by imported Indian palampores (figs. 42, 43), this motif is represented in Crosman’s work as a single or bisected stem with wavy lines below. As on many palampores and their English and American derivatives, the tree of life typically has scrolling branches terminating in a variety of leaves and flowerheads as well as birds perched and, occasionally, in flight. Although elements of Crosman’s birds can be likened to local species, it is more likely that they are imaginary representations like those on many textiles and on japanned furniture. Expensive textiles were often part of a young woman’s dowry and would commonly have been stored in a chest. It is conceivable that some of the chests attributed to Crosman commemorated marriages, and their decoration was a signifier of the contents to be held within.[28]

As totems of sophisticated international tastes and reflections of well-ordered, fruitful households, Taunton chests had a powerful effect on the eighteenth-century eye, allowing owners to communicate multiple messages both internally and to visitors to the home. In contrast, the early twentieth-century viewer inverted the meaning of the chests, casting them as symbols of simplicity. Nonetheless, a common thread unites these readings. Brazer and her counterparts were influenced by the malaise that accompanied a rapidly mechanizing society and yearned for a simpler way of life, which they equated with the colonial era. Although in a different way, the eighteenth-century consumer, too, was driven by a longing for something he or she often found hard to possess: an abundance of resources and a sense of stability within the perceived wilderness of their own environment. If consumers’ interpretations of Taunton chests have changed over time in these ways, we can see that there is a common psychological impulse behind the love of such objects—this sense of longing—while also understanding that it is the chests’ very mutability, their ability to provoke multiple interpretations over time, that gives them their power of endurance.[29]

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by a Craft Research Fund grant from The Center for Craft, Creativity and Design, Inc.; The Brock Jobe Student Travel, Research and Professional Development fund, The Winterthur Program in American Material Culture Gift Fund, and The Decorative Arts Trust. For assistance with this article, the author thanks Mark Anderson, Gavin Ashworth, Brian Baade, Wendy Bellion, Hollis Broderick, Tara Cederholm, Lisa Compton, Edward S. Cooke, Brian Cullity, Matthew Cushman, Peter Deen, Linda Eaton, J. Ritchie Garrison, John Hays, The Historical Society of Early American Decoration, Andrew Holter, Charles F. Hummel, Brock Jobe, Leigh Keno, Alexandra Alevizatos Kirtley, Gregory J. Landrey, Joshua W. Lane, Deanne Levison, Arthur Liverant and Kevin Tulimieri, Susan Newton, Catharine Dann Roeber, Frances Gruber Safford, William Samaha, Jim Schneck, Matthew Skic, Robert F. Trent, Martha Willoughby, Wintethur Library staff, and each of the museum professionals and private owners who shared information on their Taunton chests.

Appendix: Catalogue of Chests

This appendix catalogues each of the Taunton chests currently attributed to Robert Crosman’s Taunton, Massachusetts, shop. The catalogue is organized into groups according to the composition of the chests’ decoration, as discussed in the accompanying article. The individual entries note only those characteristics that diverge from or expand upon the overall description included at the outset of a given group. Within each group, entries are organized chronologically. In general, measurements apply to the size of the case, excluding the overhanging tops. Those chests noted with an asterix were not examined in person for this study.

Group A: Miniature Chests with Rudimentary Tree of Life Motifs

Each chest in this group has a lift-top and a single drawer. The chests display workman-like construction, with the four primary sides fitted together using rabbet joints and likely secured with nails beneath the corner moldings. Large wrought nails are used to attach the back, which consists of one or two boards. The bottom of the chest section is attached with two nails driven through each side. The bottom rail is set into the side boards and reinforced on either side with a wooden peg. A simple half-round molding, attached with wrought finish nails, runs down either side of the front; the bottom of the chest compartment is rounded to match the shape of the moldings. Cleats and drawer runners are attached with large nails. Snipe-bill hinges are typical where the original hardware remains. The iron lock/keyhole mechanisms, where they exist, are similar. All are made simply and may have been produced locally. The drawers are dovetailed in front and back. Drawer bottoms are set into a dado at the front and nailed at the back. These chests do not have side-pinned drawer bottoms like the large format examples examined for this study. The dimensions of the chests are similar, and some components may have been laid out using patterns. The miniature chests are more similar in form than in decoration. Decorative motifs typically consist of a single tree of life but sometimes diverge in other respects. Two examples include chicks. The use of a compass, common among other chest groups, is rarely apparent.

Catalogue 1, (fig. 44) Miniature chest with drawer, attributed to Robert Crosman, Taunton, Massachusetts, 1725–1728. Pine; paint. H. 20 1/2", W. 12 1/2", D. 12 1/2."

Provenance: By family tradition, originally owned by Robert Crosman’s son Deacon Robert Crosman, thence by descent to William Ware Crossman, Robert [and Martha] Crossman, Sarah and Ellen Hall [or alternately, William Robert Crossman, to Ella Maria Crossman Reed, to Dorothy Dean Reed], Robert and Ruth Crossman, by descent to consignors to Northeast Auctions, Furniture, Art, Decorative Objects, Silver, Portsmouth, N.H., February, 25, 2006, lot 712.

Literature: Esther Stevens Fraser [Brazer], “The Tantalizing Chests of Taunton,” Antiques 23, no. 4 (April 1933): 135, fig. 1; Taunton Daily Gazette, June 7, 1939, p. 7; Martha Wilbur, “Robert Crosman, the Taunton Chests, and Our Family Connection,” Decorator 69 (Spring 2008): cover, 22.

Exhibited: Historical Hall, Taunton (present location of the Old Colony History Museum), 1933; Old Colony History Museum, 2006 to present.

There are graphite score marks to sides of the drawer—“X” on one side and “II” on the other—which may be maker’s marks used to facilitate assembly. There are also indecipherable graphite markings to the bottom of the lid, but these do not appear to be maker’s marks. There are no wooden pegs used on the sides of the drawers, as is typical for larger chests.

Although the decorative motifs on this object are not unusual, the execution is distinctly different from that on other chests attributed to Crosman and may represent the work of an apprentice or journeyman. Alternatively, it is possible that this chest was decorated by Crosman before his skills as a painter developed fully, as suggested by Brazer: “There is about it . . . something very amateurish—as if its fabricator had been a very young man when he undertook the work” (Brazer, “The Tantalizing Chests of Taunton,” p. 136).

The early provenance of this chest, through Dorothy Dean Reed, is taken from the 2006 Northeast Auctions catalogue entry, presumably as recorded by the Crosman descendants who consigned the object. However, as noted by Martha Willoughby in her research papers, this chest was located by Brazer at 60 Dean Street, Taunton, in the attic of the former residence of sisters Ellen and Sarah Hall, where Ruth and Robert Crossman were living at the time. Genealogical records show that the Halls were connected to the Crosman family by marriage: their sister Martha married Robert Crosman, who appears to have been the great-grandfather of Dorothy Dean Reed. Martha Hall—daughter of Phoebe “Roby” and Leonard Hall—married Robert L. Crosman in 1848; the 1860 census shows that this couple were the parents of William R. Crosman, corresponding to the family history in the Northeast catalogue. In 1880 elderly mother Phoebe was living with her unmarried daughters Sarah and Ellen at 60 Dean Street (Massachusetts Town and Vital Records; and, 1860 and 1880 United States Federal Census, ). Dying unmarried after their sister Martha, it seems that the Hall sisters possibly left their property directly to Ruth and Robert Crosman, rather than the alternative narrative presented in the Northeast catalogue, that the chest descended from Robert and Martha Crosman through their son, granddaughter, and great-granddaughter as listed above.

Condition/Conservation: In “The Tantalizing Chests of Taunton,” Brazer notes that the decoration was covered by a layer of red at the time of discovery (Brazer, “The Tantalizing Chests of Taunton,” p. 136). The leaf hinges are modern replacements. The front surface of the chest is split in two places. The lift-top was originally attached with snipe-bill hinges.

Catalogue 2, (fig. 45) Miniature chest with drawer, attributed to Robert Crosman, Taunton, Massachusetts, 1725–1730. Pine; paint. H. 20 3/4", W. 22 1/2", D. 12 3/4."

Provenance: Possibly Hampden, Mass.; Art Institute of Chicago, Wirt D. Walker Fund, 1946.561.

Literature: “The First Hundred Years of American Furniture: The Sanford Collection at the Chicago Art Institute,” Antiques 52, no. 3 (September 1947): 185; Meyric Rogers, “American Decorative Arts at the Art Institute of Chicago,” Antiques 74, no. 1 (July 1958): 50; Helen Comstock, American Furniture (New York: Viking, 1982), no. 180; Joseph T. Butler, Field Guide to American Antique Furniture (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1985), no. 6.; Marvin D. Schwartz, “New Wing Presents Design, Colonial Period to Present,” Antiques and the Arts Weekly (December 30, 1989): 38–39; Judith A. Barter and Monica Obniski, For Kith and Kin: The Folk Art Collection at the Art Institute of Chicago (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press for the Art Institute of Chicago, 2012), no. 4.

Black painted markings on the backboard appear to have been added by a later owner and consist of “RDC[?]/Hampden/M[?]/S[?]” plus a sequence of numbers that may represent a zip code. There are graphite markings on either side of the carcass: “X” and “XI.” Pegs have been added to tighten the joint where the drawer bottom is dadoed to the drawer front. The backboard only extends down far enough to cover the chest section. This chest retains its original lock and snipe-bill hinges.

This is the only chest attributed to Crosman’s shop with a blue ground. The painted decoration incorporates the initials “HB,” but there is no accompanying date. It has been speculated that the “B” might stand for a member of the Blake family of Taunton, since Crosman’s second wife was Desire Blake. However, they did not marry until after 1762, long after the year inscribed on Crosman’s latest dated chest. Further, according to the files of the Old Colony Historical Museum (Lisa Compton, letter to Claire Moschel of the Art Institute of Chicago, August 19, 1993, acc. file 1900.74, Old Colony History Museum Library, Taunton, Mass.), genealogical research has failed to identify any Crossman in-law whose initials correspond with those on the chest. The decoration includes a finely executed tree of life, two successions of chicks, and clusters of three berries, motifs repeated on many Taunton chests. Somewhat more unusual are the starburst motifs, the thorn-like shape of some of the leaves, and the triple-leaved terminations of the tree’s primary branches. Also uncommon is the dentate border on the molding beneath the drawer, which appears on only one other example (cat. no. 7).

Condition/Conservation: There are no records of conservation in the Art Institute of Chicago files, but there appears to have been some infilling of damaged areas of the case. The accession file contains several infrared photographs of markings on the chest’s backboard. The brass pull is probably a replacement.

Catalogue 3, (fig. 46) Miniature chest with drawer, attributed to Robert Crosman, Taunton, Massachusetts, 1725–1730. Pine; paint. H. 21", W. 22 5/8", D. 13."

Provenance: Mary Allis, Fairfield, Conn., before November 1969; The Old Store on the Harbor; Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum, Museum Purchase, 1971.2000.1.

Literature: Wendell D. Garrett, “Living with Antiques: The Connecticut Home of Mary Allis,” Antiques 96, no. 5 (November 1969): 754. Barry A. Greenlaw, New England Furniture at Williamsburg (Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia / Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1974), no. 72.

There are graphite markings on the carcass: “X” on the left side and “I” on the right. Pins secure the drawer frame. The iron lock appears to be original and is similar to the example illustrated in figs. 18 and 19.

The combination of pointy, single-lobed leaves and oblong clusters of white dots, with heavily undulating dotted lines beneath each tree, does not appear on any other chest, although a similarly formed line is barely discernible at the bottom of the example illustrated in cat. no. 6, and a more crudely executed version of the pointy leaves appears on the chest shown in cat. no. 21. The smaller trees on the drawer face, with their combination of single- and three-berry clusters, resemble those on cat. no. 6.

Condition/Conservation: The hinges have been replaced with modern ones. There is a long split to the front surface of the chest. The edges have sustained numerous scrapes and scratches from long use.

* Catalogue 4, (fig. 47) Miniature chest with drawer, attributed to Robert Crosman, Taunton, Massachusetts, 1725–1730. Pine; paint. H. 20 1/2", W. 22 1/4", D. 12 3/4."

Provenance: Esther Stevens Brazer, before 1933 through at least 1943; Historical Society of Early American Decoration; to a private collector in September 1990; to Keno Auctions, American and European Paintings, Folk Art, Furniture, and Decorative Arts, New York, January 18, 2011, lot 156.

Literature: “Antique a Day,” Boston Evening American, January 6, 1930; Esther Stevens Fraser [Brazer], “The Tantalizing Chests of Taunton,” Antiques 23, no. 4 (April 1933): 136, fig. 3; “Antiques in American Homes: The Long Island Home of Mr. and Mrs. Clarence W. Brazer,” Antiques 43, no. 5 (May 1943): 218.

The decoration is most similar to that of the chest illustrated in cat. no. 6. Judging from a photograph included in the 1943 Antiques article cited above, the chest occupied a prime place beside the fireplace in Brazer’s -studio.

Condition/Conservation: According to Keno’s catalog entry, the top is replaced, the lock is missing, and square nail holes are present where cleats once would have been. The entry also notes that traces of green paint were apparent, and some in-painting had occurred on the smaller trees. The bottom rail is repaired.

*Catalogue 5, (fig. 48) Miniature chest with drawer, probably by Robert Crosman, Taunton, Massachusetts, 1725–1730. Pine; paint. H. 21 1/2", W. 21", D. 12 1/4."

Provenance: Sam Winek, September, 1910 (sold for $8, William J. -Hickmott Scrapbook, ms. 84470, Connecticut Historical Society); William J. Hickmott, Hartford, Conn., ca. 1957; current location unknown.

Literature: Luke Vincent Lockwood, Colonial Furniture in America (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1957), fig. 39.

Although it is difficult to make judgments based solely on a single old photograph, the proportions and construction features of this chest—including the half-round moldings, “boot-jack” feet, thumb-nail molded lid, iron keyhole escutcheon, and nail placement—are consistent with other pieces attributed to Crosman’s shop.

The decoration is unusual in having small tightly scrolled branches following the lines of larger, simpler ones; however, similar motifs appear on the chest shown in cat. no. 21. Idiosyncratic details on this object —the slightly pointy berries and dotted wavy lines—also occur on the chests illustrated in cat. nos. 2 and 3.

Catalogue 6, (fig. 49) Miniature chest with drawer, attributed to Robert Crosman, 1727. Pine and chestnut; paint. H. 20 1/2", W. 22 5/8", D. 13."

Provenance: John S. Walton, 1957; Ima Hogg, 1957; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Bayou Bend Collection, gift of Miss Ima Hogg, B.57.92

Literature: David B. Warren, Bayou Bend: American Furniture, Paintings, and Silver from the Bayou Bend Collection (Houston: Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1975), fig. 30.

The backboard is dated 1727 in red paint. There are score marks on the left side of the case interior and left side of the drawer, both resembling “X.” There is also a “I” on the right side of the carcass. The backboard does not extend beyond the chest compartment, as on the chests illustrated in cat. nos. 2 and 7.

The decoration on this chest is one of the simpler compositions associated with Crosman’s shop. In a departure from the ornament on the Crosman family example (cat. no. 1), many of the tree branches are tightly curled, fitted underneath a schema of two overarching c-scrolls. The remains of a heavily undulating dotted line, similar to that found beneath the tree of the chest illustrated in cat. no 3, can be seen along the bottom of the drawer frame.

Condition/Conservation: The lock is missing, and the drawer pull is replaced.

Catalogue 7, (fig. 50) Miniature chest with drawer, attributed to Robert Crosman, Taunton, Massachusetts, 1728. Pine; paint. H. 20 1/2", W. 21", D. 12 1/4."

Provenance: Thought to have descended in the Montgomery -family, Taunton (Lisa Compton et al., “Chart of Chests” [working paper], no. 2, accession file 1900.74, Old Colony History Museum Library, Taunton, Mass.; Exhibition label, accession file 8.2.4.256, Dietrich American Foundation); Jess Pavey Collection, Mich.; to Garth’s Auctioneers, Jess Pavey Collection of American Antiques, Delaware, Ohio, October 22, 1967, lot 561; Dietrich American Foundation.

Literature: Brian Cullity, Plain and Fancy: New England Painted Furniture (Sandwich, Mass.: Heritage Plantation of Sandwich, 1987), no. 5.

Exhibited: Detroit Institute of Art, November 1964–July 1965; Valley Forge, 1970–1978; Morgan House, Kulpsville, Pa., 1978–1986; Heritage Plantation, Sandwich, Mass., 1987; Baltimore Museum of Art, 1988–1993; Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1993 to present.

The back of the chest is dated 1728 in black paint. The backboard extends to the bottom of the chest section. The chest has its original hinges, lock, keyhole escutcheon, and key.

The front bears the initials “AD” and the date “1728.” The initials are surrounded by a rectangle made up of wavy lines, a detail similar to that of the chest shown in cat. no. 2. “AD” may refer to Alice Hayward, who married Joseph Drake in Bridgewater, Massachusetts, in 1727. She was the daughter of Joseph Hayward and Sarah Crosman and appears to have been a great-granddaughter of Robert Crosman I and a second cousin of the chest maker (Massachusetts Town and Vital Records, ; and, Robert Owen Crossman, A Genealogy of the Crossman Family: Descendants of John and Robert Crossman of Taunton, Massachusetts [Morrilton, Ark.: Crossman, 1977], p. 241). The decoration relates most closely to that of the chest illustrated in cat. no. 2, particularly the procession of chicks along the drawer. Two more chicks roost in the branches of a tree, unusual for its double c-scroll branches. There is also evidence of a dentil border similar to the one on the chest shown in cat. no. 2.

Condition/Conservation: Quakertown furniture conservator Alan Miller removed later in-painting in the 1980s (Conversation among Chris Storb, Debbie Rebuck, and the author, July 2016).

Group B: Larger Format Chests with Multiple Trees of Life

These four chests are the most exuberant of those attributed to Robert Crosman, displaying roosting chicks, flying birds, and diverse foliage across multiple trees of life. All have a faux upper drawer with a triangle composed of wavy lines and bearing initials and usually a date. The examples examined for this study also have a lower drawer with a side-pinned bottom and compass-generated decoration as described in the text. Unless otherwise noted, all other construction details are in keeping with those described for the miniature chests in group A.

Catalogue 8, (fig. 51) Chest with drawer, attributed to Robert Crosman, Taunton, Massachusetts, 1729. Pine; paint. H. 32 3/4", W. 35", D. 17."

Provenance: Thought to have been made for Abigail Woodward of Taunton on the occasion of her 1730 marriage to George Read in Rehoboth, Mass.; by descent to Betsey Harvey Reed Briggs (Lisa Compton et al., “Chart of Chests,” no. 3, acc. file 1900.74, Old Colony History Museum Library, Taunton, Mass.; see also the family trees compiled for the Woodwards and the Reeds in this same file); Old Colony History Museum, 1900.74.

Literature: Esther Stevens Fraser [Brazer], “The Tantalizing Chests of Taunton,” Antiques 23, no. 4 (April 1933): fig. 6; Taunton Daily Gazette, November 16, 1933; Ethel Hall Bjerkoe, The Cabinetmakers of America (New York: Bonanza Books, 1957), p. 72; Peg Hall, Early American Decorating Patterns (New York: M. Barrows, 1951), p. 63; Boston Sunday Herald, August 1969; Brian Cullity, Plain and Fancy: New England Painted Furniture (Sandwich, Mass.: Heritage Plantation of Sandwich, 1987), p. 3; Martha Willoughby, catalog entry 59, in Brock Jobe et al., Harbor and Home: Furniture of Southeastern Massachusetts, 1710–1850 (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England, 2009), pl. 59.2; Benjamin Colman, “Recalling the Past: Memories and Antiquarian Objects in the Former Plymouth Colony, 1692–1824” (master’s thesis, University of Delaware, 2012), fig. 4.

The lock on this chest and the example illustrated in cat. no. 14 are marked “FC” on the rear (Lisa Compton to Deanne Levison of Israel Sack, Inc., May 19, 1992, accession file 1900.74, Old Colony History Museum Library, Taunton, Mass.). Both locks resemble those found on other chests.

The decorator used a compass to lay out some of the designs on this chest; indentations from that tool are visible at the centers of the red fruit on the center tree of the lower faux drawer. The decoration features nine different trees with six different combinations of foliage, fruit, and flowers. There are ten birds, eight of which are roosting in the trees at either side of the lower faux drawer. A pair of birds flank the center-most tree in a vignette that appears on many later chests, including where curling vines are used in place of trees. The composition of this chest relates most closely to that of the example illustrated in fig. 4, cat. no. 9.

Condition/Conservation: The drawer pulls and escutcheon have been replaced, but the hinges and lock (figs. 18 and 19) are original.

Catalogue 9, (fig. 52) Chest with drawer, attributed to Robert Crosman, 1729. Pine; paint. H. 32 1/4", W. 35 1/2", D. 17."

Provenance: Said to have been made for Sarah Andrews and given to her sister Esther Andrews Lincoln, of Taunton (1715–1803), then by descent to Susanna Lincoln Stephens (1750–1822), Esther Stephens Atwood (1781–1858), Abigail Atwood Park (1814–1880), Mary Louisa Park Paige (1842–1927), Abbie Louise Paige, Brookline, Mass.; to her cousin Franklin Atwood Park, N.Y., 1934 (sold for $865, letter from Abigail Louise Paige to Franklin Atwood Park, February 2, 1934; and, Genealogical Notes, acc. file 1988.5, Currier Museum of Art Archives); by descent to Marjorie Park Swope; Currier Gallery of Art, gift of Marjorie Park Swope, 1988.5.

Literature: Karen Blanchfield et al., American Art from the Currier Gallery of Art (New York: American Federation of Arts, 1995), no. 34.

The chest is dated and initialed “SA 1929.” There are graphite markings on the carcass: “I” on the right side and “II” on the left. The iron lock again closely resembles those found on other chests. The tulip motif appears here for the first time among the dated chests, with the center-most tree culminating in a blossom on either side. In all other respects this chest is markedly similar to cat. no. 8.

The early provenance is taken from a label compiled by Abbie Louise Paige and based on oral and written family tradition. Paige’s elders told her that the chest originally belonged to Esther Andrews Lincoln, but she proposed that the piece was made for her sister Sarah (Paige to Park). It is also plausible that the chest descended in the Atwood line and that Abigail Atwood Park inherited it. This could explain a possible discrepancy in Abbie Louise Paige’s provenance, wherein Susanna Stephens reputedly gave the chest to her daughter Esther Stephens Atwood. Esther’s mother left her just one dollar, bequeathing all of her other possessions to her other daughter (Will of Susanna Stephens, Taunton, Mass., September 21, 1823, Massachusetts Wills and Probates, ).

Condition/Conservation: Williamstown Regional Art Conservation Lab cleaned and varnished the chest in 1988 (acc. file 1988.5, Currier Museum of Art Archives, Manchester, N.H.). Areas of re-touching, particularly to the initials and date, are visible under ultraviolet light.

*Catalogue 10, (fig. 53) Chest with drawer, attributed to Robert Crosman, Taunton, Massachusetts, ca. 1729. Pine, paint. H. 33 7/8", W. 35 7/8", D. 17 1/2."

Provenance: Descended in the Pierce/Hoard families of Taunton, Plymouth, and Lakeville, Mass., then by descent to the present owner.

Literature: Leatrice Kemp, “The Taunton Chest as an Icon of Its Culture,” n.d., Old Colony History Museum Archives, Taunton, Mass.