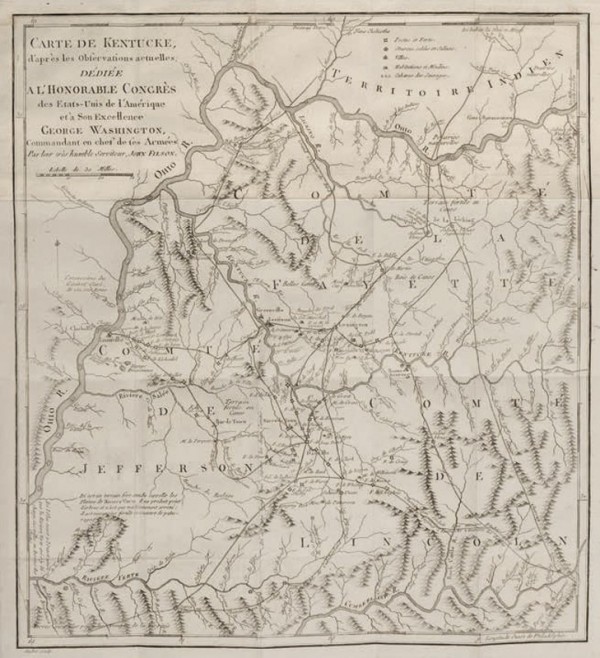

John Filson, Carte de Kentucke (Map of Kentucky), [1784], 1785. Engraving on laid paper. H. 15 1/4" x 13 1/2". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Museum Purchase, Antique Collectors Guild, 2013-83.)

Log cabin, Lexington, Kentucky, 1779–1783. (Photo, Mack Cox.) This cabin was built by Col. Robert Patterson.

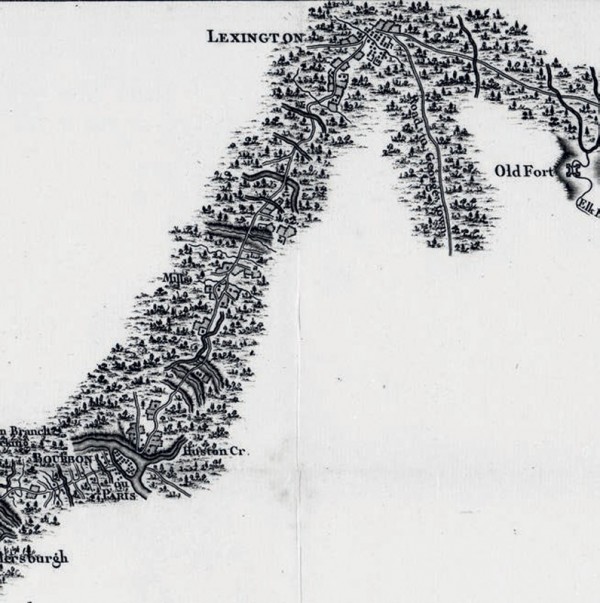

George Henri Victor Collot, Road from Limestone to Frankfort in the State of Kentucky, [1795], 1826. Engraving on paper. 21 1/2" x 21". (Courtesy, Kentucky Historical Society, 912.19769c714.)

Desk-and-bookcase, Mercer County, Kentucky, 1796. Walnut throughout. H. 102 3/4", W. 43 1/4", D. 23 1/4". (Private collection; courtesy, Cowan’s Auction.)

Desk-and-bookcase, Frederick County, Virginia, ca. 1795. Cherry with yellow pine. H. 103 3/4", W. 42 1/4", D. 24 1/2". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Museum Purchase, 1930-68.)

Tall case clock, attributed to Daniel Spencer (1741–1796), Lexington, Kentucky, 1793–1796, with movement by Thomas Walker (d. 1786), Fredericksburg, Virginia, 1760–1775. Black walnut with chestnut and yellow pine. H. 95 1/8", W. 21 5/8", D. 11 1/8". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Museum Purchase, 1951-578.) The Pennsylvania-style finials on this clock case are probably replacements.

Tall case clock, attributed to James Allen (1716–1789), with movement by Thomas Walker (d. 1786), Fredericksburg, Virginia, 1765–1785. Black walnut with yellow pine and oak. H. 96 1/2", W. 20 7/8", D. 10 3/8". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Gift of Elizabeth M. Nicholson, 2005-105.)

Tall case clock attributed to Daniel Spencer (1741–1796), Lexington, Kentucky, 1793–1796. Cherry with tulip poplar and chestnut. H. 98 1/4", W. 22 1/4", D. 11". (Private collection; photo, Mack Cox.)

Tall case clock attributed to Daniel Spencer (1741–1796), Lexington, Kentucky, 1793–1796. Woods and dimensions unknown. This clock was owned by James T. Coy, Sr. (1868–1946). (Photo, Mack Cox.)

Detail of a rosette on the tall case clock illustrated in fig. 6.

Detail of a rosette on the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 29.

Detail of the rosettes and finials on the tall case clock illustrated in fig. 8.

Detail of a finial on the tall case clock illustrated in fig. 14.

Tall case clock with movement by William Claggett, Newport, Rhode Island, ca. 1740 (movement) and ca. 1765 (case). Mahogany with chestnut and white pine. H. 100 1/4", W. 10 7/8", D. 11 5/8". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Museum Purchase, 1972-36.)

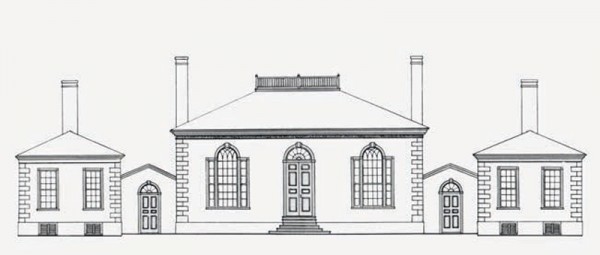

Drawing of the William Morton House, Lexington, Kentucky, ca. 1810. (Clay Lancaster, Vestiges of the Venerable City: A Chronicle of Lexington, Kentucky [Cincinnati, Ohio: Lexington-Fayette County Historical Commission, 1978], p. 29.)

Side chair, possibly by William Challen, Lexington, Kentucky, ca. 1810. Paint decorated wood. H. 35", W. 18 1/4", D. 15". (Private collection; photo, Mack Cox.) This Lexington, Kentucky, Fancy chair is of the type that William Morton may have owned in his Lexington home. Challen, a British immigrant, worked in London, then New York City by 1796, and was in Lexington, Kentucky, by 1809.

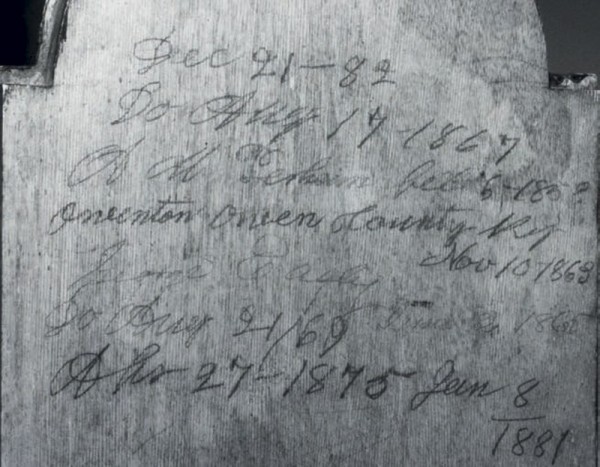

Infrared photography of the graphite inscription inside the trunk door of the tall case clock illustrated in fig. 6.

Infrared photography of the graphite inscription inside the backboard of the tall case clock illustrated in fig. 6.

Detail of a cleaning inscription illustrated in figure 17. “A M Perham feb 5-1852/ Owenton Owen County KY/ Nov 10-1863.”

Detail of a cleaning inscription illustrated in figure 17. “George Easley/June 2 1865.”

Detail showing the hood construction of the tall case clock illustrated in fig. 6.

Detail showing the hood construction of the tall case clock illustrated in fig. 8.

Detail showing the hood construction of the tall case clock illustrated in fig. 14.

Detail of a rear bracket foot on the tall case clock illustrated in fig. 6.

Detail of a rear bracket foot on a chest of drawers by John Townsend, Newport, Rhode Island, 1793–1795. Mahogany with maple, chestnut and tulip poplar. H. 34 5/8", W. 36 3/8", D. 20". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Gift of Dr. & Mrs. Warren Koontz, 1977-225.)

Detail showing a dadoed rear foot support on the tall case clock illustrated in fig. 6.

Detail of a rear bracket foot on a clothespress, Petersburg, Virginia or Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1780. Mahogany with yellow pine, red cedar, tulip poplar, and black walnut. H. 81 3/4", W. 47 3/8", D. 25 3/8". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Gift of Miss Martha B. D. Spotswood, 1977-228.)

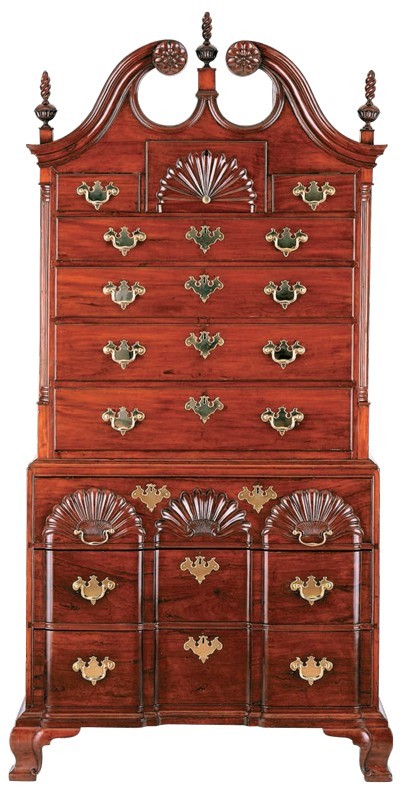

Chest-on-chest attributed to Daniel Spencer (1741–1796), Providence, Rhode Island, 1772–1790. Mahogany with chestnut, cherry, yellow poplar, and pine. H. 82 1/2", W. 42", D. 21 1/2". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Desk-and-bookcase attributed to Daniel Spencer (1741–1796), Providence, Rhode Island, 1772–1790. Mahogany with cherry, chestnut, and eastern white pine. H. 107 1/4", W. 44 11/16", D. 25 3/16". (Courtesy, Yale University Art Gallery, Mabel Brady Garvan Collection, 1940.320.)

Desk-and-bookcase signed by Daniel Spencer (1741–1796), Newport or Providence, Rhode Island, or Dartmouth, Massachusetts, 1765–1785. Mahogany with chestnut, tulip poplar, pine, maple, and cherry. H. 71", W. 38 3/4", D. 21 1/4". (Courtesy, Bernard and S. Dean Levy, Inc.)

Tall case clock, attributed to Daniel Spencer (1741–1796), Lexington, Kentucky, 1793–1796, with movement by Thomas Walker (d. 1786), Fredericksburg, Virginia, 1760–1775. Black walnut with chestnut and yellow pine. H. 95 1/8", W. 21 5/8", D. 11 1/8". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Museum Purchase, 1951-578.) Rhode Island-style finials were reproduced for this clock based on the Morton and Coy examples, and a Greek key blind fret was installed below the cornice molding based on nail evidence and a related fret on the Morton clock case.

Once part of virginia, Kentucky became the first state west of the Appalachian Mountains in 1792 (fig. 1). While explorers had known of the gentle topography and fertile soils of central Kentucky, the rugged Appalachian Mountains, distance from existing settlement, and hostile Native Americans kept settlers at bay until the 1774 Treaty of Camp Charlotte opened the region to western migration. The first permanent white settlements began in 1775 at Harrod’s Town (now Harrodsburg), St. Asaphs (now Stanford), and Boonesborough. Log cabins, including those within fortified walls, and skirmishes with Native Americans characterized the early years of settlement on the frontier. During the 1780s and 1790s settlers poured through the Cumberland Gap and down the Ohio River, bringing with them the desire to succeed in this virgin territory. A variety of craftsmen joined the throng of travelers, and by 1790 there were a handful of cabinetmakers working in Kentucky.[1]

Lexington, Kentucky, called the “Athens of the West” in a poem by Josiah Espy, became an elegant, sophisticated city. In 1806 he described Lexington as “the largest and most wealthy town in Kentucky, or even west of the Allegheny Mountains.” The city had begun more humbly around 1780, when it was comprised of a fort and log cabins (fig. 2). Chartered in 1782, Lexington grew into a town of 300 to 400 houses by 1796, some of frame and brick construction but most of logs. Despite such improvements as the construction of a stone courthouse in 1788 and a brick market house in 1792, Lexington remained a small town and a frontier community into the 1790s (fig. 3). In the summer of 1787, longtime resident Fielding Bradford recalled, “there was only a path where Main street now is . . . Gimson weeds grew so thick there you couldn’t have seen a hog on either side ten feet from the path.” Over the next twenty years Lexington changed dramatically. Fortesque Cuming, a visitor there in 1806, reported that “there are four cabinet-makers’ shops where household furniture is manufactured in as handsome a style as in any part of the country,” and the same year Thomas Ashe reported that many Lexington homes “are furnished with some pretensions to European elegance.”[2]

Although most of the late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century furniture made in Kentucky is neoclassical in form or detail, a few pieces dating from the 1790s reflect earlier modes of design. A desk-and-bookcase made in 1796 for John and Mary Cowan of Mercer County, Kentucky, illustrates this point (fig. 4). According to family lore, that object was made by a traveling cabinetmaker who fell ill and was nursed back to health on the Cowan plantation. Captain Cowan was one of the more prosperous landholders in what was then Mercer County, Kentucky, and presumably would have wanted the most fashionable furniture he could obtain. The basic design of his desk-and-bookcase relates to examples made along the Great Wagon Road from Pennsylvania to Virginia, particularly those associated with Winchester, Virginia, and neighboring Frederick County (fig. 5). As is the case with several contemporaneous Winchester case pieces, the Cowan desk-and-bookcase has scroll moldings that rise high above their junctures with the tympanum and give the pediment a lighter, more delicate aspect. This design, along with door fenestration featuring small flat panels over larger ones or single large panels with applied moldings—typically forming a rectangle with astragal corners—may be interpreted as early manifestations of neoclassic design. These neoclassic design elements were overlaid on a desk-and-bookcase form that was based on an earlier stylistic tradition. Despite the preponderance during the 1790s of neoclassic furniture along the Eastern seaboard, with French feet, veneers, and inlays, Kentuckians may not have begun to acquire furniture in the full-blown neoclassical style until circa 1795–1800. This delay was likely due to the expertise of local cabinetmakers and regional tastes rather than knowledge of the style or the availability of inlay.[3]

Scholarship on eighteenth-century Kentucky furniture is still in its infancy. In 1947 furniture historian Alice Winchester maintained that “Kentucky-made furniture [only rarely displays] a vestige of Chippendale influence.” The scarcity of eighteenth-century Kentucky furniture may reflect the paucity of cabinetmakers working there at the time or stem from misattribution. Edna Talbott Whitley’s Checklist of Kentucky Cabinetmakers from 1775–1859 lists one craftsman active in Fayette County in 1790, one in 1791, four in 1793, six in 1794 and 1795, and four in 1797. Most of those individuals were probably located in Lexington, the county seat. The dearth of cabinetmakers may have been due to the dispersed population and the frontier nature of eighteenth-century Kentucky. Newly arriving settlers would have been more concerned with subsistence and gaining an economic foothold than the acquisition of goods. As the population grew and families accumulated wealth during the late 1790s and early 1800s, there was a corresponding increase in the demand for more fashionable homes and furnishings.[4]

A tall case clock with a movement by Fredericksburg, Virginia, clockmaker Thomas Walker (fig. 6) is one of the earliest surviving examples of Kentucky furniture. For decades, the case has been erroneously attributed to the Shenandoah Valley region of Virginia. Previous furniture scholars recognized that the case differed significantly from those associated with Fredericksburg, which typically follow British design and construction practices (fig. 7). The ogee feet, fluted quarter-columns, and broken-scroll pediment with floral volutes were viewed as stylistic details that emanated from Philadelphia and influenced furniture designs in eastern Pennsylvania, western Maryland, the Shenandoah Valley, and Carolina back country, and it was plausible to assume that a cabinetmaker working west of Fredericksburg might have been commissioned to make a case for a Walker movement. Walker enjoyed widespread patronage, and few other clockmakers were active in the northern Virginia piedmont or Shenandoah Valley until the end of the eighteenth century. William Cabell, who lived in Amherst County just north of Lynchburg, Virginia, noted in his 1774 diary that he had “sent watch by P. Rose to Walker in Fredericksburg to be put in good order.”[5]

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation purchased the clock illustrated in figure 6 from the New York City antiques firm Ginsburg & Levy, Inc., who originally acquired the piece from New York dealer Abe Keyman in 1947. In a 1951 letter to curator John Graham, Bernard Levy described the case as being “undoubtedly of Southern workmanship” and noted that it showed “New England and Pennsylvania influence” and had “rosettes . . . almost exactly the same as those found on . . . [John] Goddard block-and-shell clocks and . . . fine finials . . . very much like Philadelphia ones, though slightly heavier in form.” Levy’s observations on the rosettes were astute (figs. 10, 11), but for most observers that feature was overshadowed by the clock’s other misinterpreted characteristics for the next half-century. It was not until two clock cases in private collections (figs. 8, 9) came to light that the Rhode Island attributes of the example illustrated in figure 6 were reconsidered. Both of the privately owned clocks have rosettes like the example with the Walker movement, along with Rhode Island-style flame finials (figs. 12-14). Although only one case was available for study, its finials have lower sections with fluted petals rising to the middle of the ball and upper “flames” simulated by spirals that were carved, filed, and finished while the work-piece was mounted on the lathe. Examination of the clock case illustrated in figure 8 revealed construction details similar to those on the example with the Walker movement, suggesting that all of these related cases were by the same cabinetmaker.[6]

The Kentucky histories of the clocks illustrated in figures 8 and 9 raised questions about the origin of the Walker case. One belonged to James T. Coy, Sr., who lived near Lexington in the early twentieth century; the current location of that object is unknown (fig. 9). The other clock descended in the Morgan and Morton families of Lexington, Kentucky, from its original owner, William Morton (fig. 8). Morton was an English immigrant who arrived in Lexington by 1787 and was a successful merchant, tanyard owner, and insurance company director. At the time of his arrival, Lexington was a frontier settlement. Commerce and transportation began to improve after the trustees of the town ordered that all streets be opened and cleared of stumps in 1788. That same year, local resident Mary DeWeese observed that “Lexington is a clever little Town with a court house and Jail and some pretty good buildings in it, Chief [ly] Log.”[7]

By 1810 considerable progress had been made on the town, and Morton, as one of the wealthiest inhabitants, built an ambitious Federal-style brick house with Kentucky marble steps on Mulberry, now Limestone, Street (fig. 15). His 1836 probate inventory includes a tall case clock, two cherry sideboards, a sofa, a parlor carpet, and a French tea set, each valued at $25. Due to the expense of importing heavy objects and materials into Kentucky prior to the introduction of steamboats, the majority of furniture made there from the late eighteenth to the mid-nineteenth centuries was constructed with locally available woods: cherry or black walnut primary, and mainly tulip poplar as well as yellow pine, sycamore, chestnut, ash, and oak secondary. After visiting Lexington in 1806, Fortesque Cuming noted that “the high finish given to the native walnut and cherry timber precludes the regret that mahogany is not to be had but at immense cost.” Morton was one of the few early settlers who could afford mahogany furniture. His inventory listed two sets of mahogany chairs, one in his dining room and one in his parlor, and one mahogany bedstead. Each “sett [of] mahogany chairs” was valued at $70. These unusually expensive objects were probably shipped to Kentucky rather than produced locally out of imported mahogany. By comparison, Morton owned a set of twelve Fancy chairs valued at $24 that were likely made by a local Lexington Fancy chairmaker such as William Challen (fig. 16).[8]

The cost of Morton’s clock relative to the imported mahogany furniture he owned and the woods used in its construction suggest that the case was made locally. Although chestnut was readily available to Kentucky cabinetmakers, it is not common in their work. The use of chestnut secondary in the construction of the clock cases illustrated in figures 6 and 8 was probably a conscious choice based on the maker’s prior experience working with that wood. Indeed, one of the few places where chestnut was almost habitually used as a secondary wood during the eighteenth century was Rhode Island.

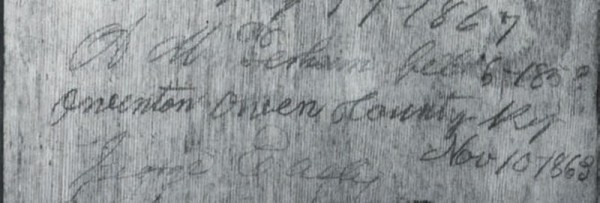

Although the Walker clock lacks an early history, inscriptions inside the case reveal that it was in the Lexington area from at least the mid-nineteenth century until the early twentieth century. Three Kentucky clock repairers/jewelers/silversmiths signed and dated the interior when they cleaned the movement (figs. 17, 18). Alfred M. Perham of Owenton, Kentucky, appears to have worked on the movement repeatedly. He only inscribed his name and location in 1863, but analysis of the handwriting indicates that he also cleaned the clock in 1867, 1869, 1875, 1881, and 1882. One additional date that may be in Perham’s hand appears to be 1852 (fig. 19). If so, that would represent the earliest known maintenance on the clock. Perham’s 1851 advertisement in the Lexington Observer & Reporter reveals that he was active in Lexington, Kentucky, at that date and that he had visited Georgetown, Paris, Versailles, Midway, Danville, Harrodsburg, and Athens—cities encircling Lexington—“as often as once in six months.” Other Kentucky clocks signed by Perham have inscriptions designating his location as Owenton, where he had moved to around 1860. The addition of his locale suggests that Perham continued cleaning clocks in the Lexington vicinity and wanted his customers to have a reminder of where to find him.[9]

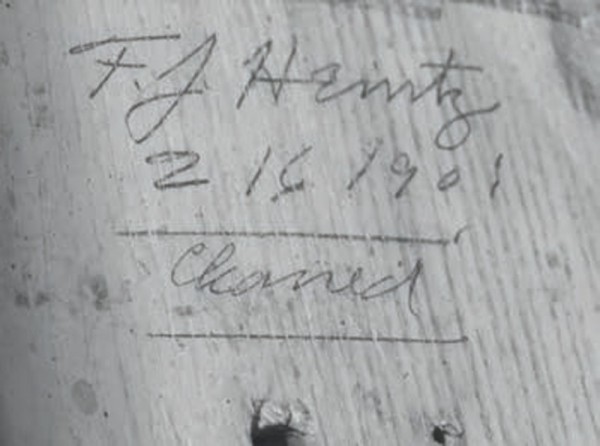

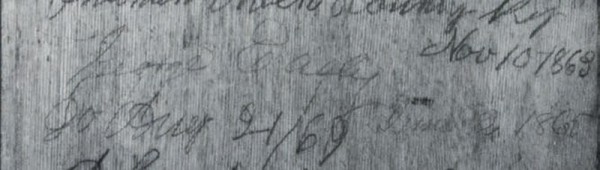

George Easley, a silversmith and farmer, signed the clock with the Walker movement in 1865 (fig. 20). Easley had been apprenticed to Lexington silversmith Asa Blanchard until the latter’s death in 1838. Despite the fact that Blanchard left Easley and another apprentice, Eli Garner, his silversmith tools, there is no evidence that the two apprentices ever worked together or that Easley ever opened his own shop. The 1850 census lists Easley as a silversmith with 700 acres in Jessamine County, Kentucky, just outside Lexington, but the 1860 and 1880 censuses describe him as a farmer. Silversmiths often did basic cleaning and repairing of clock movements, and it is clear that Easley continued that practice, perhaps seasonally, until at least the mid-1860s, when he worked on the Walker clock. The third name inscribed in the clock case is Frederick J. Heintz, who dated his signature 1901 (fig. 18). He was a jeweler in Lexington, Kentucky, from about 1887 until about 1940.[10]

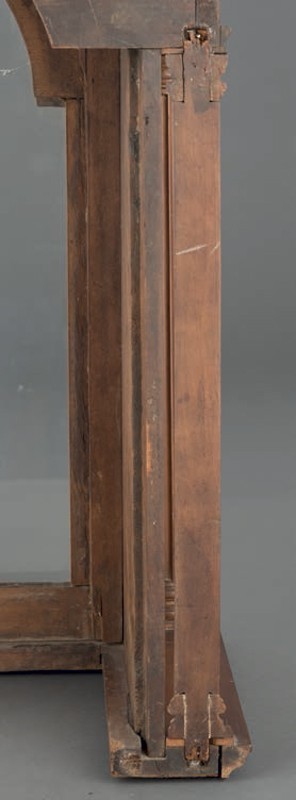

Several features of the clock with the Walker movement and the example that descended from William Morton suggest that the case maker was familiar with Rhode Island work. In addition to their shallow-fluted, eight-petal rosettes and the Rhode Island-style finials on the Morton and Coy examples (figs. 8 and 9), the cases examined for this article have typical Rhode Island hood door joinery, with the stiles tenoned into the top and bottom rails rather than the latter members being tenoned into the stiles as is found in clocks from most other regions. Although not all Rhode Island clock cases are constructed the same, many have features in common with the Walker and Morton examples: hood sides that are dadoed to the base frame and nailed up from below, and hood columns with separate bases, capitals, and abaci plinths attached to the tenons that hold each column in place. On the rear columns of the clock cases illustrated in figures 6 and 8, the tenons are nailed into open mortises in the back of the base frame and frieze-board (figs. 21-23).[11]

The rear feet on the Morton case are replaced, but those on the example with the Walker movement share details with contemporaneous and earlier Rhode Island furniture. Most notable are the cyma-shaped profile of the back of the rear feet (figs. 24, 25) and the use of a dado in the attachment of their support bracket (fig. 26). Most ogee rear feet from other regions are straight at the back and have butt-joined support (fig. 27). The shape of the ogee bracket feet on the Morton case does not follow either a typical Newport or Providence design, but appears closer to Pennsylvania work. This same foot design was perpetuated by cabinetmaker William Lowry working in nearby Frankfort, Kentucky, about a decade after Spencer’s death.[12]

Daniel Spencer

Only one Rhode Island cabinetmaker is known to have worked in Fayette County, Kentucky, at an early date. Thus Providence cabinetmaker Daniel Spencer (1741–1796), who died in Lexington in 1796, is the most plausible maker of the aforementioned clock cases. He apprenticed in Newport from around 1755 until 1762, possibly with his uncle John Goddard, a renowned Quaker cabinetmaker. Spencer relocated to Dartmouth, Massachusetts, by 1771 and to Providence the following year. A number of ambitious block-and-shell case pieces have been attributed to Spencer, including a chest-on-chest made for Providence merchant Jabez Bowen (fig. 28) and a desk-and-bookcase commissioned by Providence merchant John Brown (fig. 29). These attributions are based on relationships between those objects and a desk-and-bookcase signed by Spencer (fig. 30). Despite the quality of his work and the high level of patronage that he enjoyed, Spencer had fiscal problems throughout his career and was jailed for debt in 1785.[13]

Around 1790 Spencer’s financial difficulties and the death of Ann Spencer, his first wife and mother of their children, may have prompted his relocation to Lexington, Kentucky. It is also possible that Spencer was influenced by contemporaneous accounts that described Kentucky as a veritable Eden, abounding with “walnut, cedar, white and red oak, ash, elm, maple, sycamore, sugar maple and mulberry trees . . . the finest country on earth for horned cattle . . . and deemed the very best for corn, tobacco, indigo, cotton, hemp and flax.” Newspaper reports of Indian attacks and other challenges of frontier life did not dissuade Spencer from moving.[14]

In the June 8, 1793, issue of the Kentucky Gazette, Spencer reported that he had “taken a shop [in Lexington] . . . where he intends to carry on the cabinet and chair making business in its several branches” and that he “wants to purchase Cherry and Black Walnut plank and scantling suitable for Cabinet and Chair work, for which he will give a generous price in Cash.” According to one early historian, Spencer began making reed-bottom chairs and advertised repairing all types of seating just a few weeks after opening his shop. Little else is known about Spencer’s time in Kentucky. He signed his will on April 20, 1796, and died a few months later. Spencer’s dwelling house and personal estate consisting of cabinet work, joiner’s tools, plank, scantling, and unspecified household furniture sold at auction under the direction of his executor and landlord, William Huston.[15]

Daniel Spencer’s will was probated in Lexington in 1812. It lists the names of his (second) wife, three sons, and seven daughters. Of his ten children, at least five married in Providence between 1788 and 1802. By 1841 his son Giles and daughters Susannah Spencer and Nancy (Ann) Bliven had moved to Albany, New York, where Daniel’s brother Thomas had established himself as a merchant or trader. Daniel’s other son, Daniel, Jr., and daughters Margaret Lawrence and Lydia Williams remained in Providence. There is no evidence that any of Daniel Sr.’s children moved with him to Kentucky, but nothing is known about the lives of James, Katherine, and Welthen Spencer. It is also unclear when or where Daniel married his second wife, Mary. There is no record of their union in Rhode Island, which has relatively complete records, so it is possible that they married in Kentucky.[16]

Spencer's ownership of two pieces of property in Lexington suggests that his financial situation improved after moving to Kentucky. He purchased a lot in Lexington from Samuel McMillen in 1794 and owned a “lott of Ground in the Town of Port William at the mouth of the Kentucky [River]” at the time of his death. According to Robert Holmes, a Lexington Windsor chair and wheel-maker whose shop was located near Spencer’s property, Spencer provided McMillan with “Cabinet Work” in lieu of cash for his lot in Lexington. Port William, now known as Carrolton, was laid out as a town in 1792 at the confluence of the Ohio and Kentucky Rivers. Spencer most likely purchased the lot there as an investment. Goods and people heading from Pennsylvania to central Kentucky by river might have passed through Port William, as would have Kentucky produce being shipped south to market in New Orleans. Spencer’s knowledge of the land in Port William may indicate that he arrived in Kentucky by way of the Ohio and Kentucky Rivers rather than overland through the Cumberland Gap.[17]

The style of the clock cases attributed to Spencer aligns with both his Providence work and the slowly evolving tastes of Lexington’s early consumers. Although no Rhode Island clock cases associated with Spencer have been identified, he did make the form. In 1767 he charged clockmaker Thomas Claggett of Newport £300 (in highly inflated currency) for a clock case. A Rhode Island desk-and-bookcase signed “Dan Spencer” (fig. 30) is considered the “Rosetta Stone” for attributions to him, but variations in the construction of those pieces are observable. Some have back feet with cyma-shaped rear edge profiles and dadoed supports like those on the Walker case, whereas others do not. This same type of inconsistency occurs in the construction of the Walker and Morton clock cases; not every detail is identical, yet they are clearly by the same hand. One related detail not evident in an initial comparison of the two cases is the Greek key fret below the cornice molding of the hood. This element, seen on the Morton clock (fig. 8), had been lost from the Walker case and was subsequently reproduced for it along with Rhode Island-style finials (fig. 31).[18]

Despite the fact that Daniel Spencer worked for three years in Lexington, Kentucky, the clock cases that are the subject of this article are the only objects attributed to him from that time. The furniture listed in his estate inventory, some of which he presumably made, the work he exchanged for land in Lexington in 1794, and his financial recovery during his residence there all suggest that Spencer had a successful business. Future research may lead to the identification of additional objects and forms by him. The discovery of Daniel Spencer’s migration from Rhode Island to Kentucky has been unexpected, but similar revelations are anticipated in the future as Kentucky furniture studies progress. Kentucky was the first region settled west of the Appalachian Mountains and began the era of westward expansion in America. Thus its history and its furniture are integral to a broader understanding of the East Coast.[19]

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For assistance with this article, the authors thank Andy Anderson, Jim Birchfield, Greg Black, Jason Copes, Ron Hurst, Pat Kane, Angelika Kuettner, Frank Levy, Kirsten Moffitt, Sumpter Priddy, Albert Skutans, and Chris Swan.

Lowell H. Harrison and James C. Klotter, A New History of Kentucky (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1997), pp. 10–14. T. S. Arthur and W. H. Carpenter, The History of Kentucky from Its Earliest Settlement to Its Present Time (Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo & Co. 1853), pp. 27–29. Otis K. Rice, Frontier Kentucky (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1993), pp. 72–78.

Poem and quote by Josiah Espy as quoted in https://www.nps.gov/nr/travel/lexington/athens.htm. Clay Lancaster, Vestiges of the Venerable City: A Chronicle of Lexington, Kentucky (Cincinnati, OH: Lexington-Fayette County Historical Commission, 1978), pp. 6, 12, 14–15, 18. Fielding Bradford as quoted in Charles R. Staples, The History of Pioneer Lexington 1779–1806 (Lexington: Transylvania Press, 1939), p. 47. Fortesque Cuming, Sketches of a Tour in the Western Country, through the States of Ohio and Kentucky (Pittsburg, 1810) as quoted in Mary Willis Shuey, “Early Kentucky Cabinetmakers,” in Antiques 34, no. 6 (June, 1941): 306. Thomas Ashe, Travels in America Performed in 1806, 3 vols. (London: Richard Phillips, 1808), 2: 147.

“The Captain John Cowan Kentucky Secretary and Bookcase,” Cowan’s Auction, October 20, 2017, lot 291. https://www.cowanauctions.com/lot/the-captain-john-cowan-1748–1823-kentucky-secretary-desk-and-bookcase-3079226.

Alice Winchester, “Kentucky Furniture: The Styles,” in Antiques 52, no. 5 (November, 1947): 359. Mack Cox, unpublished list of “Pre-1805 Kentucky Cabinetmakers” (not including joiners, house carpenters or apprentices) compiled from Edna Talbott Whitley, A Checklist of Kentucky Cabinetmakers from 1775–1859 (Paris, KY, 1981), pp. 46, 67, 87, 93, 101, 113, 115. Fayette County—one of the three original Kentucky counties—was far larger in 1790–1792 than it is today.

According to the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (MESDA) Craftsman Database, most clockmakers began appearing in Valley of Virginia records around 1790. There were two mentioned in the 1760s: Clock smith Michael Barker took an apprentice, Jacob Williams, in Frederick County in 1763, and Samuel May was listed as a watchmaker and silversmith in Winchester in 1760. As quoted in Wallace B. Gusler, Furniture of Williamsburg and Eastern Virginia, 1710–1790 (Richmond: Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, 1979), p. 171.

E-mail from Frank Levy, Bernard & S. Dean Levy to Tara Chicirda, November 21, 2016, copy in CWF Object File #1951-578. Letter from Bernard Levy of Ginsburg & Levy, Inc. to John Graham, curator, November 8, 1951. Copy in CWF Object File #1951-578. For similar Rhode Island finials and rosettes, see Patricia E. Kane, Art & Industry in Early America (New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 2016), figs. 7, 8, 10, 11, cat. 56, 58, 60, 62, and 80; and Michael Moses, Master Craftsmen of Newport: The Townsends and Goddards (Tenafly, NJ: MMI Americana Press, 1984), figs. 1.19, 3.62a, 3.91, 3.92, 3.97, 3.109, 5.29, 7.17a, 7.20, 7.21, 8.5c, 8.11b, 8.12c, 8.13c, 8.14b, 8.15, 8.16c, 8.17c, 8.18a, 8.20, 8.21a, 8.24, pl. 1–2, 4, 12, 22.

The Coy clock appears in an early twentieth-century family photo of the James Tandy Coy, Sr. (b. 1868, Madison County, KY; d. 1946, Madison County, KY) home located in Kirksville, Madison County, Kentucky. Great-grandson Mack Cox knew the clock as “the Coy family clock.” The clock presumably descended to James Tandy Coy, Sr. from his great-grandfather, Samuel Coy (b. 1777, Montgomery County, MD; d. 1846, Howard County, MO), who wed Frances Page (b. 1784, Jamestown, VA; d. 1852, Howard County, MO) in 1801 in Madison County, Kentucky. James Tandy Coy, Sr. died in 1946 and one of his eight children inherited the clock, but which one is unknown nor is its present whereabouts. Photograph supplied by family descendant Mack Cox. A private collector purchased the Morton clock from Clifton Anderson, a Lexington, Kentucky, antique dealer, in September 2016. Anderson had acquired it from an undisclosed descendant of William Morton. Accompanying the clock was a coin silver beaker bearing the mark “A. Blanchard” for Lexington, Kentucky, silversmith Asa Blanchard, and engraved with an “M” and the Morton family crest; a coin silver pitcher bearing the mark “F&G” for Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, silversmiths Fletcher and Gardiner and engraved “M”; and a carbon copy of a letter dated April 26, 1926, from a grandson of William Morton to John Hunt Morgan, Esq. of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, concerning the purchase of his grandfather’s clock. The undisclosed descendant who sold the clock to Anderson was said to be a grandson of the letter’s author, or a great-great-great-grandson of William Morton. The clock was in Lexington, Kentucky, in 1926 and described as having at least one “sprial” finial. One eight-day clock valued at $25.00 is listed in William Morton’s probate inventory, taken December 12, 1836 (Fayette County, Kentucky, Will Book N, pp. 94–96), and was presumably among the items offered at the estate sale at his residence on December 14, 1836. Morton’s sale was advertised in the Kentucky Gazette on December 1, 1836, p. 3. Presumably an ancestor of John Hunt Morgan, Esq., who came from a prominent Lexington, Kentucky, family, bought the clock there since it descended in the Hunt/Morgan family until 1926 when it was reunited with the Morton family. Other Morton family relics changed owners at the same time as the clock, including his dueling pistols. While the chain of ownership from William Morton to the present owner is incomplete, there is sufficient evidence to believe it is correct. Staples, History of Pioneer Lexington, pp. 46, 52, 63, 68, 255. Mary Coburn Deweese journal, January 29, 1788, as published in Running Mad for Kentucky: Frontier Travel Accounts, edited by Ellen Eslinger (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2004), p. 145.

Clay Lancaster, Antebellum Architecture of Kentucky (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1991), p. 145, and Lancaster, Vestiges of the Venerable City, pp. 28, 29, 30. William Morton probate inventory, December 12, 1836, Fayette County, Kentucky, Will Book N, 1836, pp. 94–96. Fortesque Cuming, as quoted in Shuey, “Early Kentucky Cabinetmakers,” p. 306.

Advertisement for Alfred M. Perham (clock repairer), Lexington Observer & Reporter, April 5, 1851. Inscription in the Calk tall case clock, privately owned (Cox). Alfred Perham is listed in Owen County, Kentucky, in both the 1860 and 1870 US Federal Censuses as a mechanic (1860) and clock repairer (1870). He does not appear in any 1850 census in Kentucky, possibly due to his arrival in Paris and then Lexington in 1851 as detailed in his advertisement. Ancestry.com. 1860 and 1870 United States Federal Census [database online]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc., 2009. Images reproduced by FamilySearch.

Marquis Boultinghouse, Silversmiths, Jewelers, Clock and Watch Makers of Kentucky, 1785–1900 (Lexington: M. Boultinghouse, 1980), pp. 105, 302, 322. Easley was listed as a silversmith in Jessamine County, Kentucky, in the 1850 US Census and a farmer in the 1860 and 1880 US Censuses. Ancestry.com. 1850, 1860, and 1880 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc., 2009. Images reproduced by FamilySearch.

Patricia E. Kane and Gary R. Sullivan, “‘On this Moment Hangs Eternity’: Clockmaking

in Colonial and Early Federal Rhode Island,” in Kane, Art & Industry, p. 104. See Analytical Report, project #35181, Colonial Williamsburg Conservation Archives. Because the clock case and finials had been refinished, the samples extracted and analyzed were inconclusive in determining whether these finials were replacements or not. Given that the related Morton and Coy clocks have Rhode Island-style finials, it is highly unlikely that those on the case with the Walker movement are original. The original finials may have been discarded when that case was shortened prior to 1951. For Rhode Island clocks with the rear column tenons nailed into open mortises in the back of the base frame and frieze-board, or with the hood sides that are dadoed to the base frame and nailed up from below, see: The Rhode Island Furniture Archive at the Yale University Art Gallery, RIF94, RIF1102, RIF4393, RIF1208, RIF5448, RIF6068, RIF1855, RIF4251, RIF4610, RIF4515, RIF6040, RIF6110, RIF2275, RIF6097; and, Colonial Williamsburg acc. 1972-36.

Wendy A. Cooper and Tara L. Gleason, “A Different Rhode Island Block-and-Shell Story: Providence Provenances and Pitch-Pediments,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 1999), p. 185.

Providence Gazette, October 15, 1796. Rhode Island Furniture Archive, RIF281, RIF47, RIF1232, RIF2912, RIF5337, RIF5542, RIF3601; and, Daniel Spencer Biography. Kane, Art & Industry, pp. 308–13, 449. The United States Chronical (Providence, Rhode Island), July 14, 1784.

On July 8, 1790, the United States Chronicle reported, “DIED. . In this Town, Mrs. Spencer, wife of Daniel.” James N. Arnold, Vital Extracts of Rhode Island, vol. 15 (Providence, RI: Narragansett Historical Publishing Company, 1906), p. 556. This was most likely Ann Easton Spencer. Another death of “Mrs. Spencer, wife of Daniel, in this town” was reported in the United States Chronicle (Providence, Rhode Island), October 18, 1792. This was most likely Daniel Spencer, Jr.’s wife, Elizabeth Johnson Spencer, whom he married March 13, 1791. Arnold, Vital Extracts of Rhode Island, vol. 15, p. 556, and vol. 10, pp. 165, 172. “Extract of a letter from a gentleman in Lexington, (Kentucky) to his friend in this city [Philadelphia], dated October 20, 1790,” New-York Packet, November 25, 1790, p. 2.

Kentucky Gazette (Lexington, Kentucky), June 8, 1793. Staples, The History of Pioneer Lexington, p. 94. This advertisement was not cited by the author and cannot be substantiated in extant Kentucky newspapers. Kentucky Gazette, July 20, 1796. Providence Gazette (Providence, Rhode Island), October 15, 1796.

Will of Daniel Spencer, Fayette County, Kentucky, Will Book B, 1809–1813, pp. 421–22. A fire in the Fayette County courthouse in 1803 destroyed most of the records. The 1812 probated will is a copy of the original document. The Fayette County, Kentucky, tax list for 1793–1796 records Daniel Spencer and one other white male age 16–20 in 1794 only. While it is possible that this young man was one of Spencer’s sons (most likely James, who was younger than sixteen in 1790), the short duration of the former’s residence suggests instead that he was a journeyman. Daniel’s will lists his second wife, Mary, and children Giles, Daniel, James, Margaret Lawrence, Katherine Spencer, Elizabeth Anthony, Welthen Spencer, Ann Spencer, Lydia Spencer, and Susannah Spencer (Will of Daniel Spencer). Giles Spencer moved to Albany, New York, around 1798 and may have been the man of that name who advertised a trunk manufactory in 1798 (Albany Register, January 8, 1798). Isaac Hansen, master of the New York Court of Chancery and justice of the peace in Albany, recorded the oath of Giles Spencer “to me known” as well as that of two of Daniel’s other children, Susannah and her husband John Spencer and Nancy (Ann) Bliven in 1814 (Daniel Halstead v. McMillin Heirs et al.: Letter from Isaac Hansen [received February 10, 1814, and recorded in Book H, Folio 353, Fayette County, Kentucky], Fayette County Circuit Court Action, filed on February 15, 1820 [Archival box 56, drawer 499]). Daniel Spencer, Jr.’s estate was probated in Providence in 1800 (Providence, Rhode Island Book of Wills, vol. 8, 495–486, docket A3559). Margaret Spencer Lawrence lived in Providence until her death in 1817 and was buried in the North Burial Ground in Providence (Providence Gazette, May 10, 1817). Elizabeth Spencer Anthony died in Providence in 1819 (Providence Gazette, December 11, 1819). A Providence justice of the peace questioned Lydia Spencer Williams and her husband Andrew Williams, Jr. in 1814 (Daniel Halstead v. McMillin Heirs). The death of “Mrs. Spencer, wife of Daniel” was reported in the United States Chronicle on July 8, 1790. Vital Extracts of Rhode Island, vol. 15, p. 556.

Will of Daniel Spencer. Daniel Halstead v. McMillin Heirs. MESDA Craftsman Database records indicate Holmes was a Windsor chair and wheel maker, as well as a maker of bristle brushes, whose shop was across the Main Cross Street (now Broadway) in Lexington from the lot of ground Daniel Spencer owned. Daniel J. Kenny, Illustrated Cincinnati: A Pictorial Hand-Book of the Queen City (Cincinnati: Robert Clark & Co., 1875), p. 26.

Kane, Art & Industry, p. 98. Rhode Island Furniture Archive, RIF2912. The construction differences between the Walker and Morton clock cases are as follows: the Walker is black walnut with yellow pine (movement seat board) and chestnut, while the Morton is cherry, tulip poplar, and chestnut; the hood backboard is dovetailed to the sides on the Walker and nailed to the sides on the Morton case; the hood upper outer sides or frieze-board are set in a rabbet in the back of the tympanum on the Walker and joined with a miter on the Morton; the hood top board is nailed on the tops of the sides, back, and an inner tympanum backing board on the Walker and nailed to boards nailed to the inside, the sides, the top of the back, the tympanum backing board, and a board nailed inside the tympanum backing board on the Morton; the Morton has additional thin blocks above the capitals and below the bases of the case quarter-columns that are not present on the Walker case; glue blocks reinforce the case side to front stiles and backboard joints on the Morton but not the Walker case. The case bottom board is half-blind dovetailed to the base sides, and the base molding is nailed to the trunk front and sides on the Walker case; the case bottom board is set in a rabbet in the base sides and nailed in place from the sides on the Morton case. The wide boards that comprise the base molding on the Morton are nailed to the underside of the case bottom. Based on the comparison of the Walker and Morton clocks, a few alterations were noted to the Walker clock and corrected with conservation. It was unclear from finish analysis whether the Pennsylvania-type finials that the Walker clock arrived with in 1951 were original to the case or replacements. Given the Rhode Island finials on the other two clocks and the other Rhode Island construction and design details evident on all three clocks, Colonial Williamsburg chose to copy the Morton case’s Rhode Island-style finials for the Walker case. Curators and conservators also noted a shadow and nail holes below the cornice molding on the Walker case that suggested it originally had a blind fret like the Greek key fret on the Morton case. That fret was reproduced as well for the Walker clock.

Kentucky Gazette, July 20, 1796. Daniel Halstead v. McMillin Heirs.