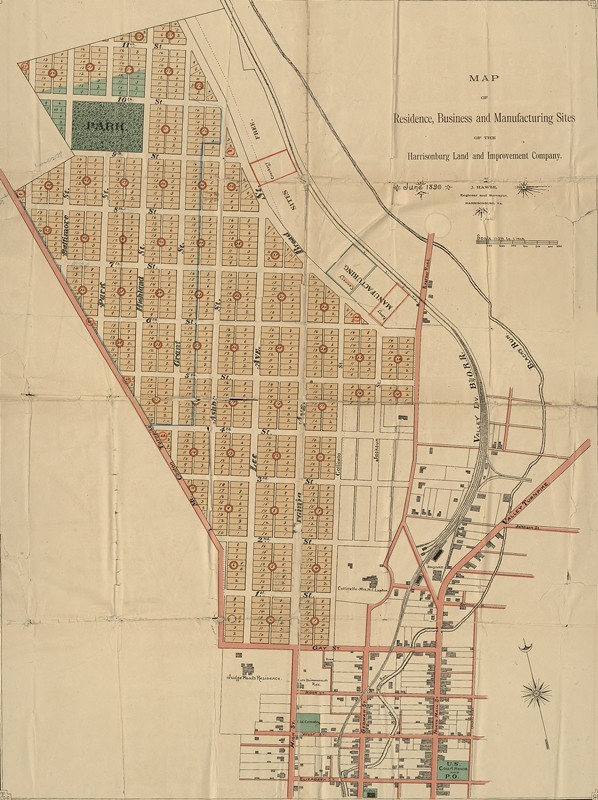

Map of Harrisonburg Land & Improvement Company Sites, 1890. C. M. Berry v. Harrisonburg Land & Improvement Company, Rockingham County Chancery Causes, 1901-007, p. 160.

The Virginia Pottery, Harrisonburg, Virginia, 1890. (Courtesy, Julius F. Ritchie Collection.)

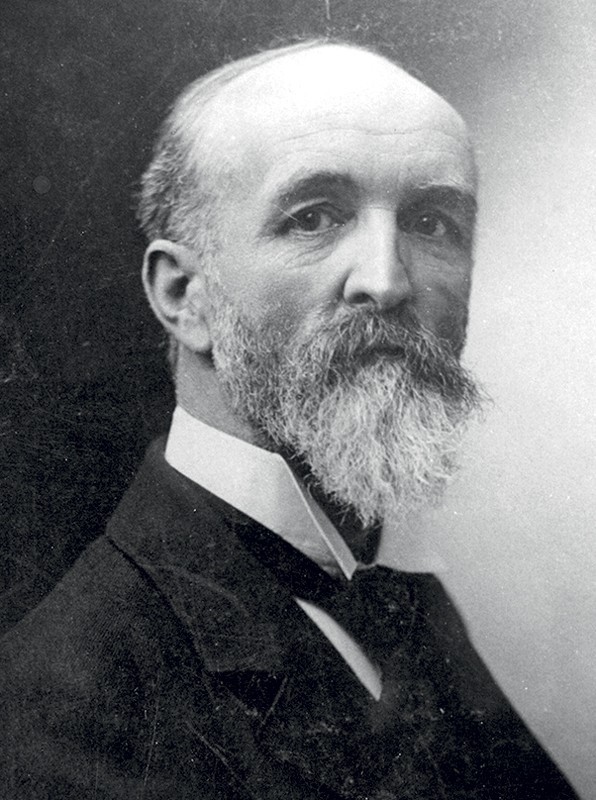

William W. Sherratt (1849–1892), ca. 1885. (Courtesy, Zach Houck.)

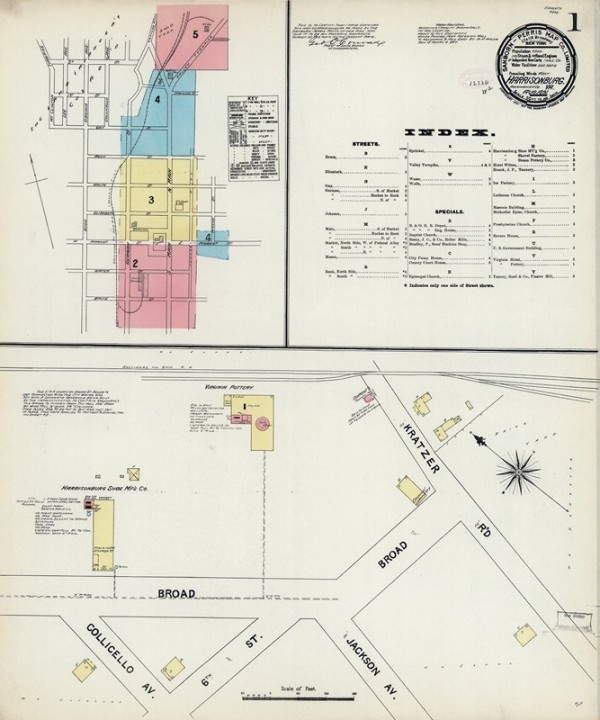

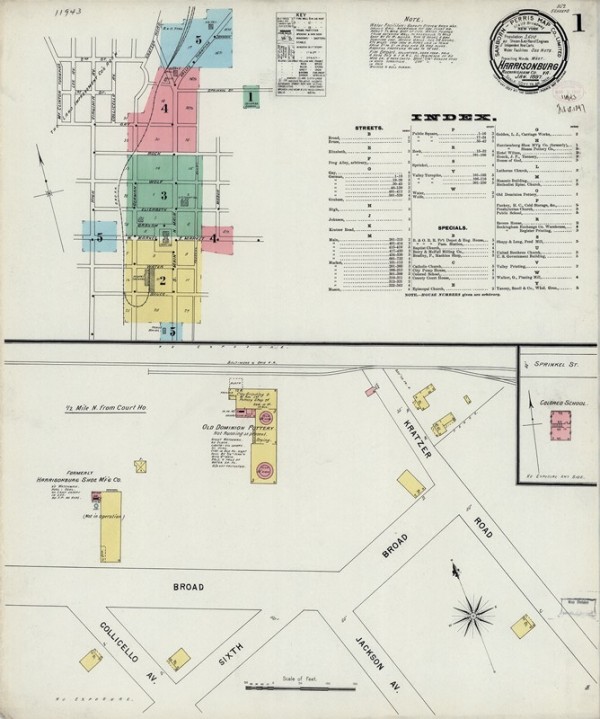

Sanborn Map, 1891, sheet 1, showing the Virginia Pottery. Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Harrisonburg, Independent Cities, Virginia, Sanborn Map Company, August 1891; www.loc.gov/item/sanborn09029_002/ (accessed January 22, 2019).

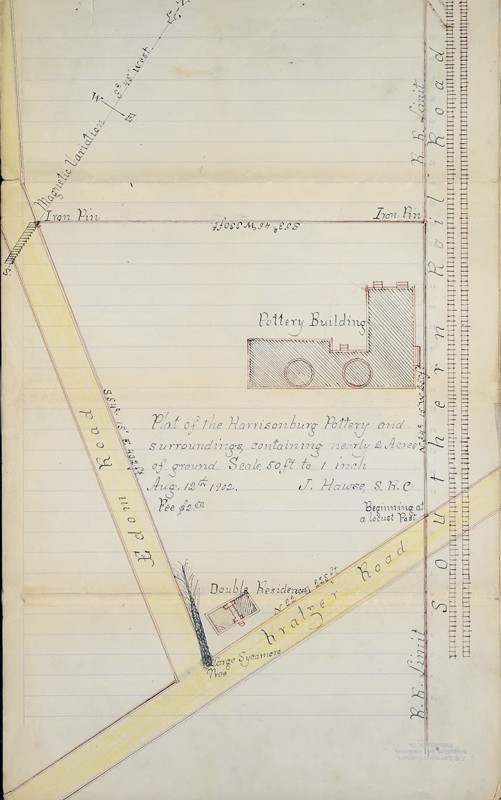

Plat drawn by Jasper Hawse, 1902. Lupton, Sullivan & Company vs. Harrisonburg Land & Improvement Company, Rockingham County Chancery Cause 1906-038, p. 649.

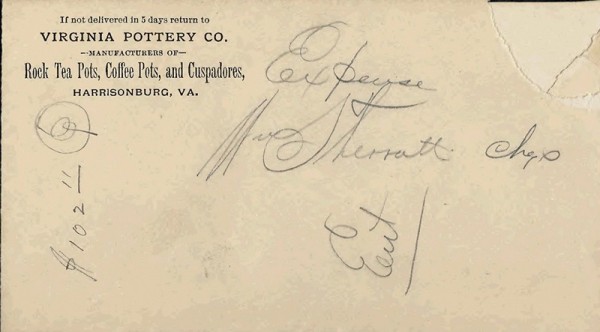

Virginia Pottery envelope, Sprinkel and Houck v. Sprinkel and Houck, Rockingham County Chancery Cause 1901-072.

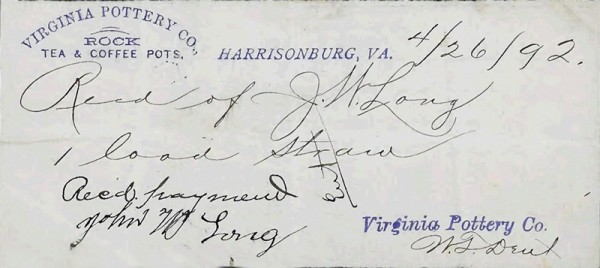

Virginia Pottery receipt, Sprinkel and Houck v. Sprinkel and Houck, Rockingham County Chancery Cause 1901-072.

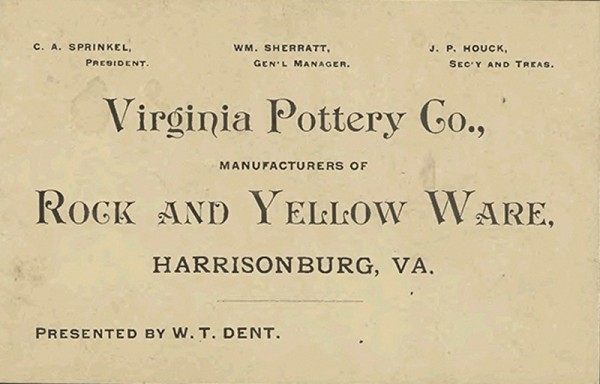

Virginia Pottery business card, Sprinkel and Houck v. Sprinkel and Houck, Rockingham County Chancery Cause 1901-072.

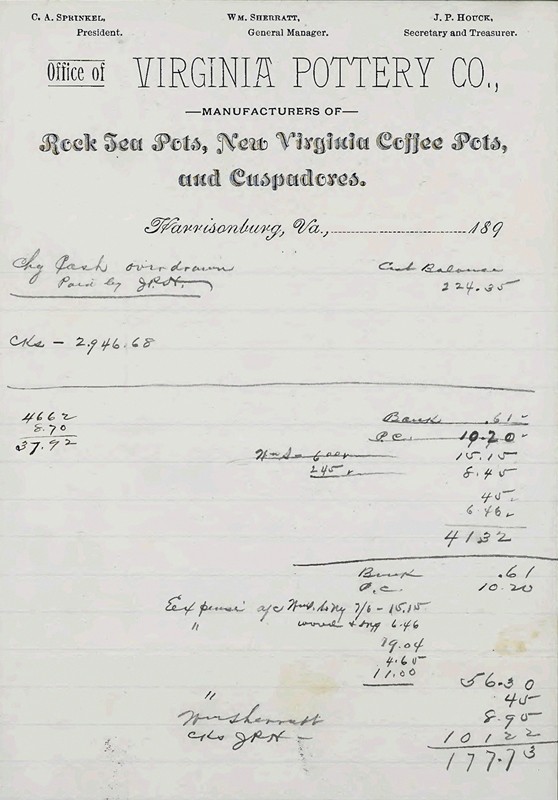

Virginia Pottery letterhead, Sprinkel and Houck v. Sprinkel and Houck, Rockingham County Chancery Cause 1901-072.

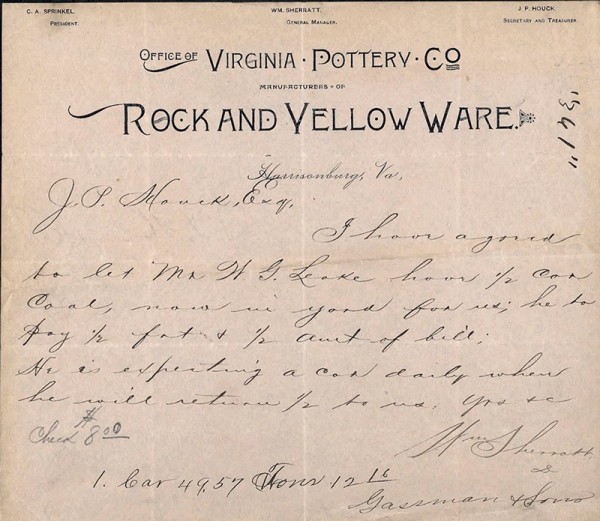

Virginia Pottery letterhead, Sprinkel and Houck v. Sprinkel and Houck, Rockingham County Chancery Cause 1901-072.

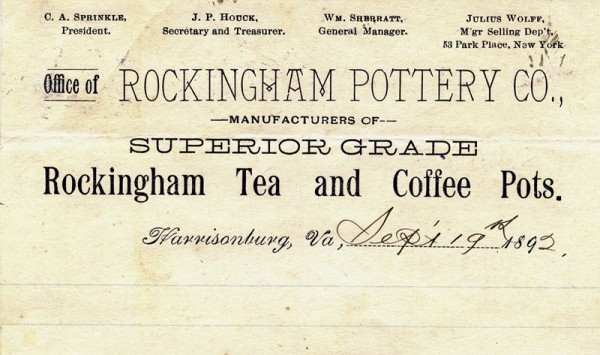

Rockingham Pottery Company letterhead. (Private collection.)

Rebecca-at-the-Well teapot, Virginia Pottery Company or Rockingham Pottery Company, Harrisonburg, Virginia, 1890–1892. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 6". (Private collection; photo, William McGuffin.)

Knobs and handles from teapots, Virginia Pottery Company or Rockingham Pottery Company, Harrisonburg, Virginia, 1890–1892. Lead‑glazed earthenware. (Private collection; photo, William McGuffin.)

Cuspidor base fragments, Virginia Pottery Company or Rockingham Pottery Company, Harrisonburg, Virginia, 1890–1892. Lead‑glazed earthenware. (Private collection; photo, William McGuffin.)

Reverse view of the cuspidor base illustrated in fig. 14.

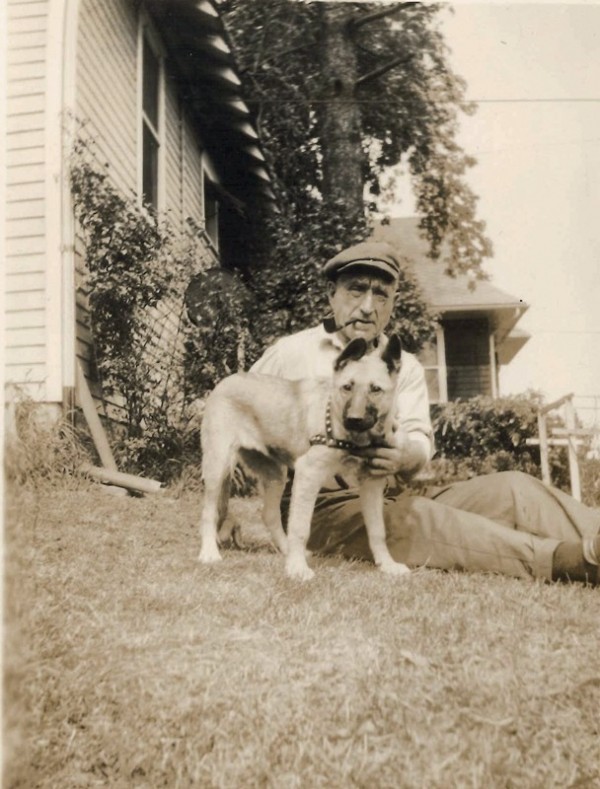

Sandy Daniels (1865–1938), undated. (Courtesy, Zach Houck.)

Sanborn Map, 1897, sheet 1, showing the Old Dominion Pottery. Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Harrisonburg, Independent Cities, Virginia, Sanborn Map Company, January 1897; www.loc.gov/item/sanborn09029_003/ (accessed January 22, 2019).

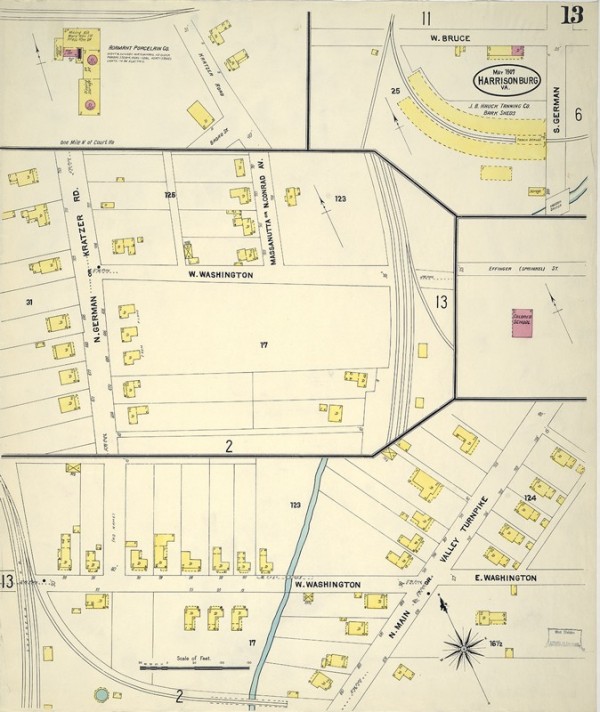

Sanborn Map, 1907, sheet 13, showing the Adamant Porcelain Company. Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Harrisonburg, Independent Cities, Virginia. Sanborn Map Company, August 1912. “Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps” (Teaneck, N.J.: Chadwyck-Healey, 1983).

Cover of the Standard Porcelain Catalogue, Adamant Porcelain Company (Lmtd.) (New Market, Va.: Henkel & Co., n.d.). (Courtesy, Special Collections Department, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va.)

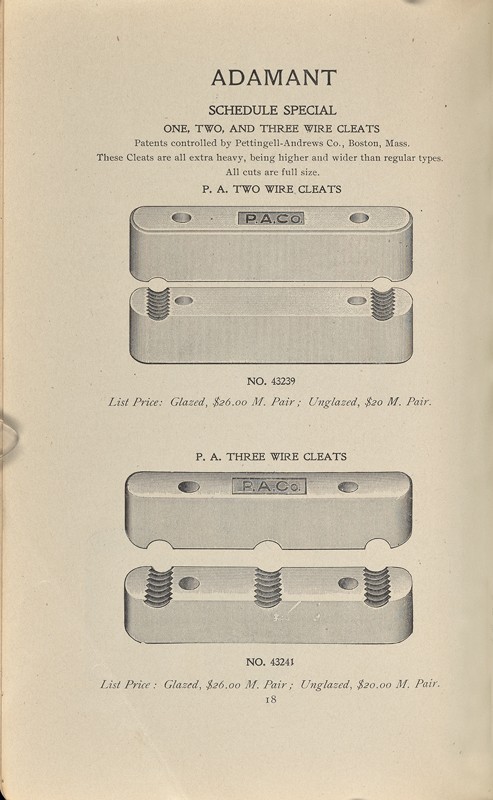

Standard Porcelain Catalogue, Adamant Porcelain Company (Lmtd.), p. 18 (New Market, Va.: Henkel & Co., n.d.). (Courtesy, Special Collections Department, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville.)

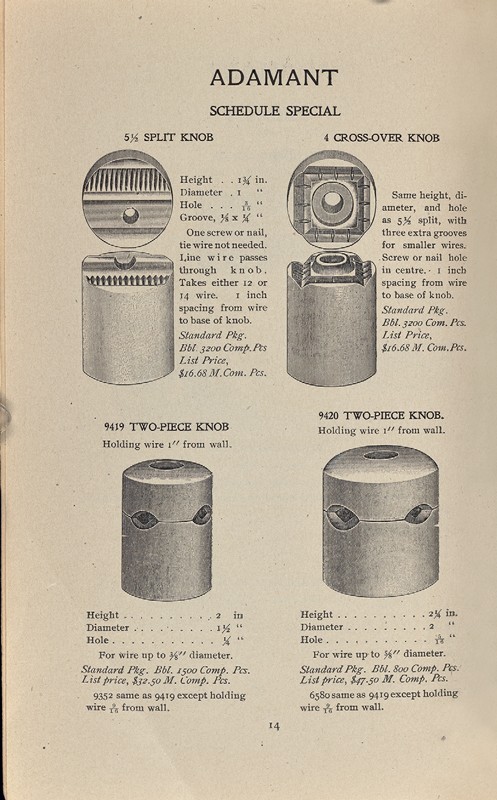

Standard Porcelain Catalogue, Adamant Porcelain Company (Lmtd.), p. 14 (New Market, Va.: Henkel & Co., n.d.). (Courtesy, Special Collections Department, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville.)

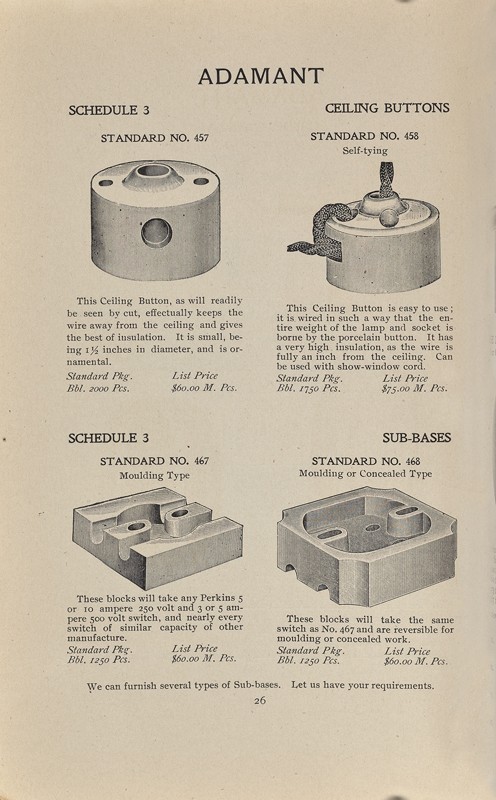

Standard Porcelain Catalogue, Adamant Porcelain Company (Lmtd.), p. 26 (New Market, Va.: Henkel & Co., n.d.). (Courtesy, Special Collections Department, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville.)

John Edwin Roller (1844–1918), principal owner of the Adamant Porcelain Company. (Courtesy, Harrisonburg-Rockingham Historical Society.)

Elias Howard Sellards (b. 1875), Pit of kaolin—Edgar, Florida, 1909. Black-and-white photoprint, 5 x 7". (State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory: www.floridamemory.com/items/show/124319 [accessed February 27, 2018]; Florida Geological Survey Collection GE0066.)

The Shenandoah Valley has been renowned as a pottery region ever since the eighteenth century. Potters recognized the excellent clay sources in the area, and scholars and collectors have acknowledged the incomparable ware that has been produced from that clay. The socially and culturally significant craft has been analyzed in books, essays, and exhibitions, and individual craftsmen and their shops are the focus of much scholarly activity.[1] In 1890 the reputation of the region led one group of late-nineteenth-century entrepreneurs to open an industrial pottery for the manufacture of fancy ware in Harrisonburg, Virginia, a booming town in the central valley. Comprised of local business leaders and a Staffordshire-bred potter most recently from Trenton, New Jersey, the faction opened a state-of-the-art manufactory. Although rarely mentioned in studies of Shenandoah Valley pottery, this venture represents the final chapter of the region’s pottery culture. This essay combines the history of the physical pottery building, available documentary evidence, and archaeological material to fill in the gap left by the many years of focus on the traditional aspects of the Shenandoah Valley region’s pottery production. By exploring the business side of the five different entities that manufactured ware at the site, the background of the potters themselves, and archaeological remains, this study contributes to a more complete understanding of Shenandoah Valley pottery.

Introduction

The Harrisonburg Land & Improvement Company was formed in the spring of 1890, adding to the growing number of such organizations in the Valley of Virginia region. Business leaders in towns such as Buena Vista, Shendun, Lexington, Glasgow, Elkton, and Shenandoah were all capitalizing on the favorable financial and industrial opportunities of the time, and they exerted much effort in planning new residential areas and industrial sections within these communities. Subscribers to these companies expressed pride in their localities and a desire to “keep this money at home, and build up our own town.”[2] These efforts met with varied results, and the impetus affected the towns in different ways. In many instances the projected industries and businesses never materialized or failed to live up to expectations and eventually closed; still, in 1890 optimistic visions created a new landscape in the Shenandoah Valley (fig. 1).[3]

At a board meeting of the Harrisonburg Land & Improvement Company on May 29, 1890, member S. K. Cox successfully moved that “we accept the proposition made by W. W. Sherratt of Trenton, for the establishment of a pottery of higher grade on one acre of the company’s lands,”[4] and thus Harrisonburg entered the world of industrial pottery. By June the pottery was underway. Initially known by various names—the Sherratt Pottery, the Harrisonburg Pottery—by February 1891 the business had been incorporated as the Virginia Pottery Company (fig. 2), with well-known Harrisonburg businessmen and members of the Harrisonburg Land & Improvement Company as the officers. C. A. Sprinkel and J. P. Houck joined general manager Sherratt as the president and secretary/treasurer of the enterprise, the stated goal of which was to “manufacture and sell all kinds of earthen and queens ware [and] to mine and sell potter’s clay.”[5] Touting the new works and the arrival of Mr. Sherratt, the Rockingham Register reported that the manager had “been engaged for a number of years in the manufacture of pottery both in this country and Canada,” adding that he had “more recently acted in a higher capacity in the business in Trenton.” The story continued, “unless delayed by unforeseen circumstances, Mr. Sherratt hopes to turn out his first kiln of ware within ninety days.”[6] The history of this venture offers an important look at the nature of late-nineteenth-century industrial potteries outside the centers of Trenton, New Jersey, and East Liverpool, Ohio, and demonstrates the challenges such an enterprise faced in the striving “New South.”

A chronological account of this manufactory provides a useful introduction to the specifics of each attempt to operate the pottery. Initially, the Harrisonburg Land & Improvement Company offered the potter -William W. Sherratt (1849–1892) (fig. 3) an acre of land along the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) railroad, and a loan of $10,000 toward the establishment of a factory to produce decorative pottery (fig. 4). Breaking ground in June 1890, the pottery was in operation later that same year. It was successful by April 1892, according to reports in the local press, and a new charter for the company was prepared in order to reorganize and expand the business. The Rockingham Register noted that the “business has steadily increased during the time it has been in operation . . . and it is now proposed to double its present capacity.”[7] The Virginia Pottery reorganized, and on May 3, 1892, William Sherratt and the Virginia Pottery sold all of their rights to the newly incorporated Rockingham Pottery Company, which also increased its stock to $50,000, added a new partner, Julius Wolff of New York City, and instituted the growth of the business.[8] The plant doubled in size with the erection of another building and an additional double kiln (fig. 5). All was going well with the reorganization, and on a sultry day in mid-July the new kiln was fired for the first time, alarming local firemen who rushed to the scene only to find the pottery in full swing. Enthusiastic reports explained that the pottery’s two kilns had a “capacity of 1200 dozen pieces. The buildings are equipped with all the newest conveniences and appliances for the rapid handling of a large output of ware, and several new steam jiggers have also been added.”[9] The Rockingham Pottery had become one of Harrisonburg’s few thriving industries, but hard times lay ahead.

On the morning of October 29, 1892, William Sherratt died unexpectedly of heart failure at the age of forty-three, throwing the Rockingham Pottery Company into turmoil. Unable to proceed without a manager and quickly shutting its doors, the manufactory sat idle for several years as lengthy court cases attempted to unravel the financial history and failures of the company. In December 1892, the company’s accountant, William Dent, was appointed receiver and directed to attempt to make the company solvent by continuing production. The requirement of sinking the company further in debt to begin the process led creditors and lien holders to seek an injunction against the order.[10] With the injunction granted, the building and its contents were offered for sale at public auction in June 1893, when the Harrisonburg Land & Improvement Company purchased it for $6,000. Because the pottery company was still beset with troubles, however, the court set aside the sale in October 1893, and the terms were not settled until April 1901, when the sale was ratified.[11]

After remaining idle for nearly two years, in 1895 the pottery was leased to Leonard Forester, a British immigrant who had most recently managed the mechanical department of the a Broadway Pottery in nearby Broadway, Virginia.[12] A native of Longton, Staffordshire, in the United Kingdom, he had arrived in New York in 1891 and promptly moved on to Trenton, where he worked as a potter.[13] Forester’s father was the principal owner and operator of the Phoenix Pottery in Longton, and the younger Forester was negotiating to open a branch of the company in the Harrisonburg factory.[14] That arrangement never materialized; Forester contracted to rent the pottery for one year, but few details offer facts into this period. References to the company, known as the Old Dominion Pottery, are found in the diary of Benjamin Franklin Thompson, who mentioned in late December 1895 that he “went to the pottery to see about work.”[15] Thompson last mentions the business in June 1896: “I went to town and to the pottery and got my pay for 36 doz pots being $6.12.”[16] Thereafter, the records and numerous chancery causes pertaining to the pottery remain largely silent on Forester’s venture.

Curiously, in the spring of 1897 two out-of-town newspapers mentioned another pottery in Harrisonburg—the Forestwood Pottery Company—although no further accounts of it have been located and there is no indication that the pottery ever began operating in the town.[17]

Idle once again for a number of years, in 1902 a new group took control of the pottery works. Isaac Greenburg of New York City purchased the property from the special commissioner assigned to oversee the business matters in the various cases against the Rockingham Pottery Company. Greenburg agreed to pay $2,500 for the property and everything that remained in the pottery buildings.[18] He and his associates eagerly set about getting the manufactory back in shape, but factors seemed to work against them. Harrisonburg’s Evening News reported in September that while the building was in the process of being painted on the outside, inside things were moving slowly, due to the failure of materials to arrive and a shortage of skilled labor. Nevertheless, clay had been processed by late September, and Leonard Forester had been brought back as the manager of the plant he had operated six years earlier.[19] The trade journal Clay Record stated in its September 1902 issue: “The Massanetta Art Pottery company will operate the old Virginia Pottery at Harrisonburg, Pa. [sic]. Leonard Forrester [sic] will have charge of the plant.”[20]

This pronouncement is significant because it not only clarifies that Forester was the potter in charge, but also identifies the incorporated business that was reopening the shop. A document dated October 24, 1902, indicates that Greenburg and his wife, Rachel, deeded the pottery and property to the company, which was chartered according to the laws of New York with its corporate office located in New York City.[21] Named for the Massanutten Mountain ridge that bisects the Shenandoah Valley with its prominent southern peak near Harrisonburg, the company clearly had hopes of reviving the business that had never lived up to its potential in the well-recognized pottery region of northwestern Virginia. Illustrated Glass and Pottery World declared the arrival of a “new art pottery in the field,” and noted that the company was “advertising in an East Liverpool [Ohio] daily for workmen of various crafts and will have something to say to the readers of the World in the near future,” adding that “its locale has a wealth of suitable material for art ware, the dark clays of the Shenandoah valley [sic] being of fine quality.”[22]

The comment that workers were being sought in East Liverpool emphasizes a predicament identified earlier by Harrisonburg’s newspaper, that skilled labor in the field was difficult to find. Even so, the pottery was operating, as evidenced by a January 1903 notice in the Evening News: “WANTED—Two good respectable white girls, between the ages of 18 and 20 years, for wareroom work. Also a few good girls and youths from 10 to 18 years of age to learn trade. Apply THE MASSANETTA ART POTTERY CO.”[23] News of a jigger-journeyman, Mr. Lechtinstine, suing the company for being discharged without cause surely added to the company’s labor problems.

Along with the labor issues the company faced another problem—access to a water source. A series of articles in the local press details negotiations with Harrisonburg’s town council regarding access to municipal water. As early as September 1902, the company had requested that the town extend water to the pottery, and at its October meeting the town council referred to Forester’s desire for a 750-foot extension of the water main. Because the company was a private enterprise situated outside the town limits, council members felt there should be some sort of revenue guarantee, or that the company should pay for the improvement itself. No action was taken on the request, which was passed on to the council’s water committee.[24] Not revealing its opinion until March 3, 1903, that committee recommended the extension be added, provided the company contributed $400 toward the project. In exchange, the pottery would receive free water for ten years.[25] The following week the Daily News sought to dispel speculation that the pottery would close its doors, declaring that “The rumor circulated about town yesterday to the effect that the Massanetta Art Pottery would close down entirely within a few days because the town would not give the water for the building is untrue.” Forester, the article continued, revealed that a lack of coal was another contributing factor in the decision to lay off the company’s potters but that other workmen would continue to be employed. Isaac Greenburg had also been in town to discuss these issues at the pottery.[26] By April 1, however, the Massanetta Art Pottery ceased to operate in Harrisonburg. An account of the town council meeting of April 7 reported that the company protested the action of the council regarding extending water and was “disgusted with such treatment.” In light of the council’s decision, the pottery would be closed.[27] Despite remaining incorporated until 1926, the company never operated again in Harrisonburg.[28]

The manufacture of pottery at the site was not over, however. In September 1904, nearly a year and a half after the Massanetta Art Pottery ceased operation, Harrisonburg attorney and businessman John E. Roller (1844–1918) purchased the property for $3,000. Along with the real estate, the transaction included all chemicals, tools, saggers, molds, and machinery left on site, but excluded the “ware finished and unfinished that is on the premises which the party of the first part has the right to remove.”[29] In 1904 Roller, who was also the principal owner of a pottery business located at Broadway in Rockingham County, became a founding member—with William H. Tantum and Thomas Coldnough, both of Trenton—of the Adamant Porcelain Company Limited.[30] The company began to manufacture porcelain electrical fixtures in Broadway later that year, and was perhaps the most successful of the businesses to operate in the structure. Unfortunately, the Harrisonburg factory was destroyed by fire in June 1907. Without insurance, the loss was estimated to be between $8,000 and $10,000.[31] The buildings were not rebuilt and the lot has remained vacant to the present.

Virginia Pottery Company and Rockingham Pottery Company

THE STRUCTURE The pottery consisted of a three-story main building measuring 70 feet by 36 feet, and an adjoining one-story building, 30 feet by 50 feet, which also contained the double kiln.[32] Notes from stonemason G. W. Altaffer provide some measurements of the pottery’s foundation. He recorded that the main wall was 70 feet by 36 feet with an average height of 7 1/2 feet. The ell walls were 60 feet by 32 feet with an average height of 3 1/3 feet.[33] A bill dated September 23, 1890, from the Trenton kiln builder John Hawthorn indicates the work he performed for the pottery: he received $400 for constructing one double kiln and $100 for building a “decorating kiln.”[34]

Many improvements took place in connection with the company’s reorganization from the Virginia Pottery Company to the Rockingham Pottery Company. These included construction of a second kiln, raising the ell to three stories, erecting another three-story building measuring 40 feet by 80 feet, and purchasing new machinery.[35] The kiln, like the original, was constructed by Hawthorn, who received a total of $479 for his work and that of his bricklayers and laborers.[36] Hawthorn’s letter to Sherratt provides rich details about the kiln and its construction:

Trenton Dec. 6th 1891

Dear Sir,

You do not say whether you are going to build a double kiln or not, so I will give it boath [sic] ways.

I will build you a fifteen feet nine inch, in clear, kiln 15 ft 9 inch, for the sum of four hundred dollars if single and if double four hundred fifty dollars.Single Kiln $400.00

Double Kiln $450.00My estimate is for labor only and do not agree to furnishing material or scaffolding, if these terms are satisfactory. Shall be ready right after Christmas, I have 16 kilns to build early in spring so should have time to build yours first. It would be much better if you would build shed on block before building kiln so as to protect kiln and builder. The material will be as follows:

8,000 No. 1 square, 10,000 No 2, 700 arch, 500 jamb, 100 splits, 500 keys, 300 soaps, 500 wedge, 200 side skew, 200 end skew. If a double kiln add 7,000 No. 2 square and 400 wedge before ordering bricks. Let me know who you are getting them from so that I can write them about the odd bricks for almost every maker uses different terms for the same brick. If I were you I would have Mount Savage bricks for the inside arch. The bricks we used before are not good enough. When you write me again address Menlo Park Ceramic Works N.J. I shall be there till Christmas.Yours respectfully,

John Hawthorn[37]

Receipts indicate that fire bricks for the company’s original kiln were ordered from Welch, Palmer & Maxwell of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Those lots included a mixture of manufactured bricks, including Philadelphia Fire Brick, Alleghany Fire Brick, and North Savage Fire Brick.[38] The only references to subsequent brick orders are receipts from the Baltimore Retort and Fire Brick Company dated December 11, 1891, and a freight receipt for 475 fire bricks shipped on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad on December 12, 1891. The first receipt details an order for 300 arch fire bricks, 50 bullheads, 50 splits, 50 keys, and 25 skewbacks. Another receipt, from April 1892, records an order for 300 end skew, 800 arch, and 300 extra bricks.[39] A note in the margin of Hawthorn’s letter, written in a different hand, records: “Welch, Palmer, Maxwell $385.66.”

During court depositions William T. Dent, the company’s bookkeeper, described in detail the kilns and how they were used:

We have two kilns, each being divided into two parts known as upper and lower kilns, or biscuit and glost kilns. The upper or biscuit kiln is the part in which the green ware is placed for burning. This part of the process of burning is known as the “crown setting,” and the taking out of the ware after burning is known as crown drawing. After the ware is burned in the upper part of the kiln it is in a state called “biscuit” and is ready to receive the glaze. After it is glazed it is placed in saggers and the saggers one on top of the other is place [sic] in the lower or glost kiln for final burning. This part of the process is known as placing glost or lower kiln.[40]

WARE Numerous accounts of the Virginia Pottery Company and its successor, the Rockingham Pottery Company, along with archaeological fragments remain to detail the forms produced by the shop during these years (figs. 6-11). Prior to the pottery’s opening, the Rockingham Register reported that the company would manufacture white granite plain and decorated ware.[41] An undated, handwritten list on Virginia Pottery Company letterhead catalogs nappies ranging from five to eleven inches, bowls in the same range, chambers, teapots, Rockingham jugs, white jugs, bed pans, spittoons, and cuspidors; a bill from February 1892 records many of the same forms, delineating between Rockingham ware and yellow ware.[42] The two documents declare the type of ware produced by the pottery: one states “Cuspidores a Specialty”; the other identifies the company as “Manufacturers of Rock and Yellow Ware” (see fig. 8).

Legal documents also provide clues to the forms and types of ware made by the manufactory. In an 1893 deposition Dent detailed the reasons for the pottery’s failure in 1892, citing the initial use of an inferior clay and partnering with an unskilled sales representative. He noted that the manufacture of cuspidors, “which for a long time was carried on at a great loss,” was curtailed. He also recounted that “the manufacture of yellow ware also proved a losing venture, on account of the lack of room for the proper storage and handling thereof.” Importantly, he reported that the company began to make teapots exclusively, and from that point onward made high-quality ware.[43] However, a list of the inventory in 1893 refers not only to teapots, but also to yellow ware, spittoons, bowls, bakers, chambers, nappies, bedpans, and jugs (figs. 12-15).[44]

Dent detailed that the type of ware manufactured also involved technology:

After the invention of Mr. Sherratt proved a success, the company decided to adopt it and use it exclusively in the manufacture of ware. The molds before used were rendered worthless, and a full set had to be made costing at least $1,000, and the old molds for which $1,500 was paid are stored away in the garret. The molds are not worthless, but can only be used for work made by hand.[45]

Sherratt’s “invention,” which he called a “profile” or “pull-down,” has not been specifically identified and no patent information can be located, but these types of machines were not unique.[46] Noting that the “devices affixed a profile tool to a moveable arm that descended to a level limited by a setscrew to press batted clay to a mold,” Marc Jeffrey Stern points out that some Trenton shops had adopted these labor-saving devices in the late 1870s but found them unsatisfactory. Requiring few skilled laborers, these machines were supposed to increase production at a cheaper rate, but Trenton potteries learned that only small pieces could be produced on them successfully, and the tool was never widely adopted.[47] Just what Sherratt proposed is unknown.

LABOR The Virginia Pottery Company and its successor the Rockingham Pottery Company shared the same management and labor. William Sherratt was the general manager of both companies until his death in 1892, and skilled laborers were sought in both Trenton and East Liverpool.[48] Numerous laborers were hired at the pottery, including Sandy Daniels, who was from Trenton and Sherratt’s son-in-law.[49] Daniels was a skilled potter, and during the deposition hearing after the Sherratt’s death, Dent declared that Daniels’s “results were as good if not better than Mr. Sherratt’s best.”[50] Daniels was also a petitioner for the formation of the Virginia Pottery Company.[51]

Born in England, Sherratt lived at least for a time in Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, where in 1868 he married Elizabeth Gilbert. After living for several years in Scotland, the family immigrated to the United States in October 1874, eventually moving to St. Jean sur Richelieu, Quebec, Canada, in 1875 or 1876, where Sherratt was listed as a “hand” at the St. Johns Stone Chinaware Company in the 1881 Canadian census.[52] Sherratt appears to have moved with his family to Trenton in late 1887, since his daughter married there on January 9, 1888. His naturalization record lists his occupation as a “moulder.”[53]

Sherratt’s arrival in Harrisonburg warranted a mention in the Rockingham Register, which described him in favorable terms: “Mr. Sherratt is a gentleman of affable manner, and appears to be thoroughly versed in the details of the business. He is a native of England, and a strong foreign accent betrays his nativity. He has been engaged for a number of years in the manufacture of pottery both in this country and Canada.”[54] He died of heart failure at the age of forty-three; his obituary noted that he was the father of fifteen children and that all thirteen living children resided in Harrisonburg.[55] Other reports suggested that he was a man of intemperate ways. Dent commented under oath on the “unfortunate habits of the former manager” that “resulted in losses that could otherwise have been avoided,” and J. P. Houck, secretary and treasurer of the company, stated: “I remember a number of occasions, when [Sherratt] made himself very offensive, when under the influence of liquor. I refer to one however. . . . Sherratt made his appearance at the door under the influence of liquor and without any provocation on the part of Capt. Sprinkel [president of the company] used towards him some very abusive and offensive language, which so enraged Capt. Sprinkel, occasioning him to open his desk drawer and draw from it a pistol and arose from his chair, as I believe to have fired it at Sherratt, and but for my quick action and interference, I believe bloodshed or death would have occurred.”[56]

Sandy James Daniels (1864–1938) (fig. 16), Sherratt’s brief successor at the Rockingham Pottery Company, was born July 31, 1864, in Quebec and immigrated to the United States in 1887. The 1881 Canadian census lists the sixteen-year-old as a worker in the St. Johns Stone Chinaware Company. He married Sherratt’s daughter, Hannah, in Trenton in January 1888, and eventually followed Sherratt to Harrisonburg in 1890. Recalling that Sherratt worked in Canada, the two potters may have encountered each other there. Indicating that the Danielses may have returned to Trenton, their son Sandy James Jr. was born there in November 1893, and the 1900 U.S. census lists the elder Daniels in Trenton working as a kiln man.[57]

Records in the chancery causes list numerous workers at the Rocking-ham Pottery Company during the early 1890s, but for researchers of Shenandoah Valley pottery Isaac Good stands out. Good was a traditional potter who had learned the craft from the master Rockingham County potter Emanuel Suter in the 1870s. Suter, whose Harrisonburg Steam Pottery opened near the Virginia Pottery in 1891, also employed Good in his industrial venture.[58] Good’s occupation at the Virginia Pottery is listed on the payroll as a “Pull-down” operator, a task for which he received one dollar per day.[59] Good’s employment at the two industrial potteries in late-nineteenth-

century Harrisonburg presents a significant statement about how some traditional potters adapted in the wake of technological change in the craft and a downward shift in the call for traditional forms.

The payroll records itemize the many tasks that were required to keep the pottery functioning, and depending on the month there were normally about forty-five employees drawing pay. William Sherratt, Sandy Daniels, and William Dent each received $15 per week for their managerial work. The other specific jobs and rates varied according to the individual. Some employees were paid per week (six days of work), some per day, and others were paid for piece work. The tasks and rates were generally as follows:

Pull-down $1 per day

Driver $4.50 per week

Jigger Boy $2.00 per week; $ .25 per day

Decorator $3.50–$4.50 per week

Sticking Up $4.50 per week; by the piece/dozen

Kiln-man $1.00–$1.75 per week

Engineer $1.25 per day

Carpenter $1.00–$1.25 per day

Jiggering $ .25–$ .50 per day

Dresser $ .50 per day

Painter $1.50 per day

Ware room $ .25 per day

Mold Maker $3.00–$3.50 per week

Cellar Boy $ .25 per day

Off-Bearer $ .25–$ .30 per day[60]

Various random slips of paper in the chancery files also document payment for specific jobs. For instance, one shows a payment to B. F. Black of $6.00 for a week of sitting up with the kiln. Other undated, handwritten examples record paying H. Sanders for “Modelling and Moulding Flower pot $15.00,” “Modelling and Molding [a] cuspidor $10.00,” and for both “modelling” ($8.00) and “moulding” a cuspidor ($2.00).[61] Ambrose Sanders (whether a relation to H. Sanders is unknown) is another case of a skilled worker migrating to Harrisonburg from Trenton. Listed variously as a potter or saggermaker in Trenton city directories from 1888 to 1891, he shows up on the Harrisonburg payrolls as a saggermaker and kiln man in May 1891, and throughout his time at the pottery he received $1.75 per day plus $ .04 per sagger.[62] With the closing of the pottery he returned to Trenton in 1893. Additionally, by September 1890, reports indicated that “skilled artisans” were expected from East Liverpool, although none was named specifically.[63]

On November 6, 1891, the company ran the following advertisement in the Rockingham Register: “WANTED—At the Virginia Pottery a number of girls to learn decorating.”[64] Often several of Sherratt’s daughters—Laura (b. 1871), Thanie (b. 1874), and Emily (b. 1875)—performed jobs such as “sticking up” and “dressing.” Numerous other women were also employed at these jobs and were paid by the dozen according to the pieces they completed.[65] Sherratt’s son, Willie (b. 1876), made ware at the pottery from the start.

MATERIALS Both the Virginia and the Rockingham companies used materials from local and out-of-state sources. Merchants from Baltimore, Cleveland, New York, and Trenton, among other cities, supplied impor-tant pottery-making materials to the Harrisonburg plant; clay was ordered from New Jersey as well as from nearby Rockingham County sources. Machinery was likewise ordered from manufacturing centers, but smaller pieces and repairs were furnished by local machine shops and factories. What follows is a list of companies with which the pottery dealt along with the supplies each provided, divided by state and city.[66]

MARYLAND

Baltimore

• Patapsco Flint Paper Mills (Belt, Riefle & Co)—potter’s litharge, red lead, litharge, red lead, dry white lead, manganese, turkey umber, Paris white, borax

• George’s Creek Coal and Iron Co.—coal

• W. J. Chapman—coal

• James Bates—elevator

• Baltimore Retort and Fire Brick Co.—fire brick

Hanoverville

• Josephus Smith—76 tons of clay, April and May 1892

NEW YORK

Albany

• M.V.B. Wagoner—slip clay

New York City

• L. Feuchtwanger & Co.—manganese, burnt turkey umber, other colors

• John E. Thropp—steam pulldown, 1 kiln door frame, grog mill

• Louis Rosenfeld & Co.—brilliant pale gold, brilliant copper, brilliant silver, brilliant light green, brilliant light blue, brilliant carmine, bronzing liquid

• Lansker and Berstein—sponges and chamois

NEW JERSEY

Newark

• The Newark Lime & Cement Co.—plaster

South Amboy

• Rose and Son—yellow clay

—20 tons yellow ware clay

—40 tons yellow ware clay

• George Such—mixed sagger clay

Trenton

• H. E. Fisher—trimming tools, fettling knives

• Trenton Terra Cotta Co.—tile

• The Golding & Sons Co.—flint, feldspar

• Trenton Stilt Manufactory—stilts

Woodbridge

• John H. Leisen—sagger clay

OHIO

Cleveland

• Billings, King & Co.—decorating materials, “Red in Japan,” vermilion, yellow, medium green

East Liverpool

• Diamond Stilt Factory, Rowe & Mountford—spurs, stilts

VIRGINIA

Broadway

• Broadway Iron Works—turning jigger head and shaft, small jigger head, wad press, wrought step for mud mixer

Harrisonburg

• P. Bradley’s Sons—pieces for pull down, crank wheel and boring, foot for plunger, boring and set screw, turning shaft, bottom for wad box

• L. J. Golden—new shaft, welding jigger, 6 new scrapers (steel), straightening shaft, plating tools, making a new packing paddle, plating molding tools with brass, repairing jigger

• Yancey, Snell & Co.—coal

• C. L. Matthews, Fine Plumbing—pumps, pipes

Staunton

• New River Coke Co.—coal

Timberville

• S. L. Hoover—clay

PENNSYLVANIA

Philadelphia

• John T. Lewis and Brothers Co.—litharge

• Harrison Brothers Co.—potter’s red lead, litharge

• Leonard & Ellis, Oil Refiners—oil

WEST VIRGINIA

Piedmont

• H. G. Davis Coal Co.—coal

Clearly, nearly all the manufacturing machinery, fixtures, and glazing materials were shipped to the Harrisonburg pottery. Local artisans maintained the tools and machines, and occasionally, but rarely, furnished clay. That, too, was shipped primarily from Rose and Son in New Jersey.

The Old Dominion Pottery

Very little is known about this period of the pottery’s history. In late 1895 the Staunton, Virginia, press reported, “The Virginia pottery at Harrisonburg, which has been shut down for several years, has been leased by Mr. Forester, who has had large experience in the business, and will be put in operation with a full force of employees.”[67] Chancery documents indicate that the Harrisonburg Land and Improvement Company, owners of the building, leased the structure to Leonard Forester for one year beginning on January 1, 1896. Forester was to pay five hundred dollars per month for rent with an option to purchase the plant for ten thousand dollars.[68] As noted, the pottery was most likely out of business by June 1896. An 1897 Sanborn map identifies the shop as the Old Dominion Pottery, and states that it was “not running” (fig. 17).[69]

WARE No identified examples of ware from this brief period of production have been identified, and the mix of archaeological sherds sheds no light on which may have come from the Old Dominion years.

LABOR As noted, Forester was himself an accomplished potter who had come to the Harrisonburg venture after several years of working locally at the Broadway Pottery. Born in Staffordshire, England, in 1860, he is listed on the 1881 England census as a “Potter Manager,” living with his parents, Thomas and Mary Ann Forester.[70] Thomas was owner and operator of several potteries over the years in Longton, Staffordshire, most notably Thomas Forester & Sons’ “Phoenix Works.”[71] After immigrating with his wife and children to Trenton, New Jersey, in 1891, Leonard Forester moved to Rockingham County, Virginia, most likely by 1893, and his son was born in Broadway in July 1895.[72] After leaving Harrisonburg at some point in 1896, he returned in 1902 to manage the Massanetta Art Pottery. He continued to work in potteries in Ohio, including the Summitville Face Brick Company and Cowan Art Pottery.[73] He died in September 1932 in Steubenville, Ohio.[74]

No records have been found that detail the operations of the pottery during this year. Benjamin Franklin Thompson’s diary entries indicate that he did work there as a sticker-upper at the time. It is not unreasonable to assume that other local employees of the Rockingham Pottery Company returned to work there when the pottery reopened. Emanuel Suter, president of the Harrisonburg Steam Pottery, recorded that Isaac Good was working for him in 1895, indicating that Good was still working as a potter at the time the Old Dominion Pottery was operating.[75]

The Massanetta Art Pottery

Specific information about the Massanetta Art Pottery Company is also scarce, but data can be gleaned from a chancery cause filed in Rockingham County, Virginia, and from brief mentions in newspapers and trade journals. The company was incorporated in the State of New York with New York City attorney Ira J. Ettinger serving as president, Samuel Fruchthandler as secretary treasurer, and Isaac Greenburg as assistant secretary.[76]

WARE Although Paul Evans declared that “no evidence has been found that art pottery was ever actually produced” by the Massanetta Art Pottery Company, recent research reveals that ware was manufactured by the company, if only briefly.[77] An optimistic note in Harrisonburg’s Evening News of January 9, 1903, reported “Its Wares a Success,” adding,

The Massanetta Art Pottery Company will give a kiln of its wares a second burning the last of this week. The wares will be glazed by this second application of heat. The kiln, which was the first the pottery burned, was fired for the first time on Christmas day. The work was successfully done and the wares are turning out first class.[78]

Upon the closing of the shop in April 1903, Leonard Forester filed a claim for wages due him under contract. In his response to the complaint, Isaac Greenburg, acting as spokesperson for the company, offered many details that provide a clearer picture of what ware the company might have produced. Forester claimed to have “a complete line of molds, and blocks and casings for producing molds needed in the manufacture of Yellow and Rockingham ware,” and that he could make “a certain ware known as Sarguimeres [sic].”[79] Instead, Greenburg averred, “After six months of an experienced and capable mold maker, assisted for three months by Forester’s son, supplies and molds were inadequate: all of the Complainant’s efforts to make better ware had proven complete failures.”[80] Moreover, the document contends that “nearly every kiln that was burned under the management of the said complainant was a failure. Not one . . . yielding as much as twenty per cent of good ware.” Greenberg did, however, note that the “finished ware and accounts on hand” had a value of $1,000, indicating that ware was, in fact, completed.[81]

LABOR Labor information is also difficult to find for this period of the pottery. As indicated previously, newspaper accounts suggest that Forester did advertise for young, local women to work, although specific tasks are not mentioned. And the case filed by Lechtinstine reveals that workers were needed to operate jiggers. That ware was produced and that Forester mentions laying off potters reveal that skilled potters must have been active in this brief period. Similarly, Greenberg’s comments about a skilled mold maker attest to work achieved at the plant. Contractual agreements indicate the terms of Forester’s employment. He was to work for a period of three years with the following pay scale: “the first two weeks of the term hereof the sum of Twenty-five dollars per week; for the following thirteen weeks of the term hereof the sum of Fifteen dollars per week; for the following one hundred and twenty-four weeks of the term hereof the sum of Twenty dollars per week, and for the remainder of the term hereof the sum of Thirty-five dollars per week.” After the first one hundred and thirty-five weeks, he was to receive fifty shares of company stock valued at one hundred dollars per share.[82]

MATERIALS The chancery documents submitted by Greenberg clearly state assurances that Forester made to the company before it agreed to purchase the Harrisonburg properties, including his belief that he could obtain clay, coal, and other materials nearby, and that he could use clay “found in abundance on the pottery premises.”[83] While local clay could be used for pottery manufacture, Forester’s source for it is unknown. One of Greenberg’s complaints was that Forester failed to order coal and was forced to purchase inferior coal from local vendors at a higher price.

Adamant Porcelain Company Limited

When John E. Roller purchased the idle Massanetta Art Pottery plant in 1904, he quickly set about getting the place in order for manufacturing the same porcelain electrical fixtures that his pottery in Broadway had been successfully producing since the company’s organization in 1903. Repairs to the plant began in earnest in December 1904, with firebrick arriving along with four skilled kiln repairmen from Trenton (fig. 18). The new management also began to renovate the structure and replace the machinery with those needed for the new line of products. Although a January 1905 start date was anticipated, the company fired the kilns for the first time in May of that year.[84] The company’s main office was located in Virginia; its two factories were in Broadway and Harrisonburg. Promotional literature lists sales offices in Atlanta, Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, Montreal, New York, Norfolk, San Francisco, and Virginia (fig. 19).[85]

WARE Products of the Adamant Porcelain Company’s Harrisonburg manufactory are well documented since numerous sherds have been collected from the site and the company produced a catalog at some point between 1904 and 1907 (figs. 20-22). It offered many different electric fixtures including insulators of various sizes, splits, split knobs, crossover knobs, wire cleats, bushings, tubes, ceiling buttons, sub-switch bases, Snyder-Hunt knobs and insulators, straight strain insulators, egg strain insulators, and so-called nifty appliances such as a combination weatherproof cleat and shade-holder receptacle, a festoon receptacle, and a ceiling switch.[86] The Harrisonburg plant was expected to produce two kilns of ware per week, with each kiln filling one-and-a-half railcar loads.[87]

The Adamant Porcelain Company manufactured products to other firms’ specifications, and its product line, as its catalog suggests, was extensive. The declaration “Let us have your requirements for special shape porcelain; send us blue print or model,” clearly describes the company’s approach. Along with products of its own design, the catalog features cleats and knobs with patents controlled by C. S. Knowles of Boston, Massachusetts, and Pettingell-Andrews Company, also of Boston, as well as by Electrical Products Company of New York City.[88] References in the company’s ledgers indicate that among the buyers were G. F. Brunt Porcelain Works and the Manhattan Electrical Supply Company.[89]

LABOR Few specifics regarding employees of the Adamant Porcelain Company have been found; however, some facts can be inferred from a variety of sources. At the time it was destroyed by fire the pottery employed more than thirty workers and the monthly payroll averaged $1,000.[90] John Roller (fig. 23) was the principal owner of the factories in Broadway and Harrisonburg, but the company’s cofounder William H. Tantum served as general manager at both plants. Tantum was later joined by Charles A. Witt as assistant manager of the Harrisonburg pottery.[91] By December 1906, Tantum was identified as the president and general manager of both plants.[92] Tantum received $25 salary per week, while Roller was paid $15 per week.[93] No extant records indicate Witt’s pay. Another recipient of frequent payments recorded in the company’s ledgers was George B. Williams of Richmond, Virginia, who is listed as an agent. Williams was also the secretary-treasurer of the Virginia Light and Power Company, and auditor of the Richmond and Chesapeake Railway Company.[94]

MATERIALS No records have been found that relate specifically to suppliers to the Adamant Porcelain Company’s Harrisonburg plant, but a note in the local press as well as mentions in the Broadway factory’s ledgers shed light on where some materials had been obtained. Once repairs were made to the kilns, workers set about making the saggers required for production. The Rockingham Register reported that all of the nearly five thousand saggers produced were “made from native or Hoover clay,” indicating that Samuel Hoover of nearby Timberville continued to supply clay to the pottery as he had during its first venture as the Virginia Pottery. The same news item noted that “the greater part of the material for the porcelain ware is imported from England, while portions come from Maine and other states of the Union.”[95]

Kaolin, the clay required to make porcelain, was supplied by both domestic and international companies. The St. Austell China Clay Company shipped clay from its mines in Cornwall, England, and the potteries also used kaolin from the Edgar Plastic Kaolin Company of Putnam County, Florida (fig. 24).[96] Coal was purchased from J. Blair Kennerly, whose Philadelphia office managed coal from Pennsylvania’s anthracite region.[97] Local businesses benefited from Adamant Porcelain as well. Many barrels for shipping ware were supplied by the Broadway Milling Company and Shenandoah Manufacturing Company in Harrisonburg.[98]

Conclusion

Despite the promising vision of a nascent industrial center in Harrisonburg, the reality proved less rosy. Even though several businesses, along with the Virginia Pottery, opened in 1890 or shortly after: a shoe factory produced eight hundred pairs weekly; A. Norris and Company, formerly of Stowbridge, England, fabricated shovels; the Harrisonburg Steam Pottery fired stoneware; an ice factory generated its frozen product; and even a steel mill was projected.[99] By January 1893, however, Harrisonburg Land and Improvement Company president Jacob Messerole could recount the fate of many of these enterprises: “The shoe factory was sold for debt, the shovel factory failed, the ice plant has been a losing business and is advertised for sale under decree of court, the steel plant never materialized, the pottery co. is in the hands of the court.”[100] Only the pottery factory managed to maintain the ability to yield products, but, as this study demonstrates, only to a limited degree.[101] The details in this narrative suggest that the pottery industry in the central Shenandoah Valley struggled to an inglorious end. Hampered initially by poor clay and an imprudent sales force, the Rockingham Pottery Company never regained a foothold in the pottery world despite increased sales. The death of its manager foretold the demise of the company’s efforts. Optimistic attempts to revive the business were hampered by deficiencies in management and the difficulties of obtaining reliable and economical resources such as coal, water, and clay, which in turn prevented the profitable manufacture of ware on the site. The Adamant Porcelain Company mustered a successful effort for a few years by manufacturing electrical insulators, but even that seemed doomed to fail. After the Harrisonburg plant burned, the Broadway operation ceased operation in 1911.

The rich cultural history of pottery production in the Shenandoah Valley offers a broad avenue for understanding not only life in that region, but also the development of traditional crafts into other industries as well. This study offers a glimpse of one attempt to modernize the local craft of a New South town that was striving to evolve from backcountry hamlet to urban center. Although the endeavor failed, it punctuates the story of pottery in the central Shenandoah Valley of Virginia.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I thank Pete Adler, Laura Griffiths, Zach Houck, and Wendy Sherratt for graciously sharing genealogical material and photographs. I am indebted to Cheryl Lyon and Angelika Kuettner for their assistance with images. Their contributions have made this a more complete account of the history of this pottery enterprise.

See, for instance, Alvin H. Rice and John Baer Stoudt, The Shenandoah Pottery (Strasburg, Va.: Shenandoah Publishing House, 1929); H. E. Comstock, The Pottery of the Shenandoah Valley Region (Winston-Salem, N.C.: Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, 1994); JeVrey S. Evans and Scott Hamilton Suter, A Great Deal of Stone & Earthen Ware: The Rockingham County, Virginia, School of Folk Pottery, exh. cat. (Dayton, Va.: Harrisonburg-Rockingham Historical Society, 2004). Comstock offers an extensive bibliography of studies published through 1994.

Lupton, Sullivan & Co. vs. Harrisonburg Land & Improvement Co., Rockingham County Chancery Cause 1906-038, pp. 2, 218, 335.

For a look at how one of these towns—Harrisonburg—evolved after this period, see Scott Hamilton Suter and David Ehrenpreis, “Boosterism and Heritage: Postcards of Harrisonburg, 1900–1915,” in David Ehrenpreis, ed., Picturing Harrisonburg: Visions of a Shenandoah Valley City since 1828 (Staunton, Va.: George F. Thompson Publishing, 2017), pp. 89–118.

Harrisonburg Land & Improvement Co. vs. Rockingham Pottery Co., Rockingham County Chancery Cause 1901-022, p. 366.

Rockingham County (Va.) Charter Book 1, 1867–1891, p. 286.

“Personal,” Rockingham Register, June 13, 1890, p. 3.

“An Important Pottery Deal,” Rockingham Register, April 8, 1892, p. 3.

Rockingham County (Va.) Deed Book 43, 1892, p. 455.

“Fire at the Pottery,” Rockingham Register, July 22, 1892, p. 3.

“An Injunction Granted,” Rockingham Register, January 6, 1893, p. 3.

Creditors vs. Rockingham Pottery Co., Rockingham County Chancery Cause 1901-049, pp. 44, 116–17.

“Virginia Pottery Leased,” Rockingham Register, December 20, 1895, p. 3.

Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1820–1957. Year: 1891; Arrival: New York, New York; Microfilm serial: M237, 1820–1897; Microfilm roll 579; Line 29; List number 1794; www.ancestry.com/interactive/7488/NYM237_579-0758?pid=7745682&back

url=https://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?indiv%3Dtry%26db%3Dny

pl%26h%3D7745682&treeid=&personid=&hintid=&usePUB=true&usePUBJs=true. For information on his time in Trenton, see Trenton, New Jersey, City Directory, 1892; Ancestry.com; U.S. City Directories, 1822–1995 [database online]; Provo, Utah: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011. www.ancestry.com/interactive/2469/11070459?pid=580040422&back

url=https://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?indiv%3D1%26dbid%3D2469%26h%3D580040422%26tid%3D%26pid%3D%26usePUB%3Dtrue%26_phsrc%3DeDY8%26_phstart%3

DsuccessSource&treeid=&personid=&hintid=&usePUB=true&_phsrc=eDY8&_phstart=

successSource&usePUBJs=true.

“Bright Outlook for the Pottery,” Rockingham Register, March 27, 1896, p. 3.

Diary of Benjamin Franklin Thompson, December 26, 1895, private collection.

Ibid., June 27, 1896.

The Staunton Spectator and Vindicator, March 25, 1897, p. 3, noted: “It is stated that the Forestwood Pottery Co. of Harrisonburg will put in blast their pottery at that place.” Similarly, the Roanoke Times, April 4, 1897, p. 2, declared: “The Forestwood Pottery Company has been incorporated with capital stock of $50,000, and will put in operation the old Virginia Pottery at Harrisonburg.”

Rockingham County (Va.) Deed Book 68, p. 219. See also Lupton, Sullivan & Co. vs. Harrisonburg Land & Improvement Co., Rockingham County Chancery Cause 1906-038, p. 170. The Rockingham Register (August 22, 1902, p. 3) reported the sale, noting that the pottery “will be operated to its full capacity in the manufacture of goods that are in constant demand, and that the product will be marketed by a large New York firm of importers and manufacturers’ agents.”

“Pottery Matters,” Evening News (Harrisonburg), September 26, 1902, p. 1. Forester signed a contract with the company on October 4, 1902. See Leonard Forester vs. The Massanetta Art Pottery Co., Rockingham County Chancery Cause 1904-019, pp. 28–30.

“Pottery News Items,” Clay Record 21 (September 15, 1902): 26.

Rockingham County (Va.) Deed Book 69, p. 38.

Illustrated Glass and Pottery World 10 (November 1902): 18.

“Wanted,” Evening News (Harrisonburg), January 31, 1903, p. 1.

“Meeting of Town Council,” Rockingham Register, October 10, 1902, p. 3.

“Will Have Electric Fire Alarm,” Rockingham Register, March 6, 1903, p. 3.

“Rumors Untrue,” Daily News (Harrisonburg), March 14, 1903, p. 1.

“Meeting of Town Council,” Rockingham Register, April 10, 1903, p. 3.

Paul Evans, Art Pottery of the United States: An Encyclopedia of Producers and Their Marks, Together with a Directory of Studio Potters Working in the United States through 1960, 2nd ed., rev. and enl. (New York: Feingold & Lewis Publishing, 1987), p. 164.

Rockingham County (Va.) Deed Book 74, p. 98. Roller’s life and accomplishments are summarized in John W. Wayland, ed. Men of Mark and Representative Citizens of Harrisonburg and Rockingham County, Virginia (Staunton, Va.: McClure Co., 1943), pp. 298–99.

“To Reopen Pottery,” Rockingham Register, December 8, 1903, p. 2. In the Trenton City Directory of 1903 Tantum is listed as living with his widowed mother and employed by “Adamant Porcelain Wks.”

“Porcelain Plant Burned to Ground,” Harrisonburg Daily News, June 21, 1907, p. 1.

“Motion of Dr. Cox, May 29, 1890,” Harrisonburg Land & Improvement Co. vs. Rockingham Pottery Co., Rockingham County Chancery Cause 1901-022, p. 366.

Sprinkel and Houck vs. Sprinkel and Houck, Rockingham County Chancery Cause 1901-072, p. 2273.

Ibid., p. 2068.

Harrisonburg Land & Improvement Co. vs. Rockingham Pottery Co., Rockingham County Chancery Cause 1901-022, p. 132.

“Receipt–June 15th, 1892.” Harrisonburg Land & Improvement Co. vs. Rockingham Pottery Co., Rockingham County Chancery Cause 1901-022. See also Rockingham County (Va.) Deed Book 45, 1892–1893, p. 10.

Sprinkel and Houck vs. Sprinkel and Houck, Rockingham County Chancery Cause 1901-072, pp. 2615–16.

Ibid., pp. 2606–13.

Ibid., p. 3273. The Baltimore receipt is found in Harrisonburg Land & Improvement Co. vs. Rockingham Pottery Co., Rockingham County Chancery Cause 1901-022, pp. 384, 386.

Harrisonburg Land & Improvement Co. vs. Rockingham Pottery Co., Rockingham County Chancery Cause 1901-022, p. 187.

“An Important Industry,” Rockingham Register, September 12, 1890, p. 3.

Sprinkel and Houck vs. Sprinkel and Houck, Rockingham County Chancery Cause 1901-072, pp. 2584–85, 2776–77.

Harrisonburg Land & Improvement Co. vs. Rockingham Pottery Co., Rockingham County Chancery Cause 1901-022, p. 198.

Creditors vs. Rockingham Pottery Company, Rockingham County Chancery Cause 1901-049, pp. 108–9, 112.

Harrisonburg Land & Improvement Co. vs. Rockingham Pottery Co., Rockingham County Chancery Cause 1901-022, p. 200.

Sprinkel and Houck vs. Sprinkel and Houck, Rockingham County Chancery Cause 1901-072, p. 2232.

Marc Jeffrey Stern, The Pottery Industry of Trenton: A Skilled Trade in Transition, 1850–1929 (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1994), p. 32.

The East Liverpool Daily News reported on August 28, 1890, that Sherratt was in that city “after men to operate a large white and yellow ware pottery” in Harrisonburg. Harrisonburg’s press also reported that Sherratt was in Harrisonburg looking for workers, noting that he “says our factories are far ahead of those in Trenton.” “Personal,” Rockingham Register, September 5, 1890, p. 3.

The local press noted his arrival: “Mr. Sandy Daniels and family of Trenton, N.J. have become residents of Harrisonburg. Mr. D is one of the skilled artisans connected with the new pottery. “Personal,” Rockingham Register, September 26, 1890, p. 3.

Harrisonburg Land & Improvement Co. vs. Rockingham Pottery Co., Rockingham County Chancery Cause 1901-022, pp. 190–91. Daniels’s salary was $15 per week. Ibid., p. 1985.

“Virginia Pottery Company,” Rockingham County (Va.) Charter Book 1, 1867–1891, pp. 286–87.

National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C. (hereafter referred to as NARA), Soundex Index to Petitions for Naturalizations Filed in Federal, State, and Local Courts in New York City, 1792–1906, Microfilm serial M1674, Microfilm roll 264. See also Canadian Census 1881; St. Jean Town, St. Jean, Quebec; Roll: C_13205, p. 58, Family No. 258. Sherratt must have worked for the St. Johns Stone Chinaware Company, which operated in St. Jean sur Richelieu in Quebec from 1873 until 1899. See Elizabeth Collard, Nineteenth-Century Pottery and Porcelain in Canada (Montreal: McGill University Press, 1967), pp. 281–90.

NARA, Soundex Index to Petitions for Naturalizations Filed in Federal, State, and Local Courts in New York City, 1792–1906, Microfilm serial M1674, Microfilm roll 264.

“Preparing for the Pottery,” Rockingham Register, June 13, 1890, p. 3.

“Death of Wm. Sherratt,” Rockingham Register, November 4, 1892, p. 3.

Harrisonburg Land & Improvement Co. vs. Rockingham Pottery Co., Rockingham County Chancery Cause 1901-022, p. 200. Sprinkel and Houck vs. Sprinkel and Houck, Rockingham County Chancery Cause 1901-072, pp. 147–48.

https://www.werelate.org/wiki/Person:Sandy_Daniels_(1) (accessed February 12, 2018). See also Sandy James Daniels, https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/person/tree/32681108/person/72001266367/story (accessed February 13, 2018).

For information on Isaac Good, see Evans and Suter, A Great Deal of Stone & Earthen Ware, pp. 19–21; Comstock, Pottery of the Shenandoah Valley Region, pp. 410–11; and Scott Hamilton Suter, A Potter’s Progress: Emanuel Suter and the Business of Craft (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, forthcoming).

See, e.g., Sprinkel and Houck vs. Sprinkel and Houck, Rockingham County Chancery Cause 1901-072, p. 1985.

Ibid. The payroll information for the Virginia Pottery Company and the Rockingham Pottery Company is found in ibid., pp. 1937–90.

Ibid., pp. 2366, 2509, 2526. H. Sanders is most likely Henry Sanders, who is listed as a “modeler” in the 1891 Trenton City Directory, p. 529.

Ibid., pp. 1973, 1937. Sanders’s Trenton occupations are listed in the Trenton City Directory for 1888, 1889, 1891, 1893.

“An Important Industry,” Rockingham Register, September 12, 1890, p. 3.

“Wanted,” Rockingham Register, November 6, 1891, p. 3.

There are numerous payroll listings in the chancery file. For a sample from May 23, 1891, see Sprinkel and Houck vs. Sprinkel and Houck, Rockingham County Chancery Cause 1901-072, pp. 1985–90.

The numerous Rockingham County Chancery causes referred to in this essay contain this information throughout the files.

Staunton (Va.) Spectator, December 25, 1895, p. 2.

Decree of December 10, 1895. Creditors vs. Rockingham Pottery Company, Rockingham County Chancery Cause 1901-049, pp. 18–19.

“Harrisonburg, Rockingham County, Virginia, 1897,” Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Harrisonburg, Independent Cities, Virginia, Sanborn Map Company, January 1897. Available online at www.loc.gov/item/sanborn09029_003/.

1881 England Census, Staffordshire, Stowe, Trenthem, District 2, digital image available at Ancestry.com (accessed February 16, 2018); The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1881 England Census [online database], Provo, Utah, 2004. See also Certificate of Death, State of Ohio, file no. 53940, filed September 15, 1932. See also Leonard Forester, Certificate of Death, Division of Vital Statistics, Death Certificates and Index, December 20, 1908–December 31, 1953, State Archives Series 3094, Ohio Historical Society, Ohio.

See Peter Beckett, A Victorian Pottery: Thos. Foresters’ “The Forgotten Giant.” (Staffordshire, Eng.: Three Counties Publishing, 2001).

Forester was a manager at the Broadway Pottery by 1893. The Rockingham Register reported in December 1895 that the Virginia Pottery would be leased by “Superintendent Forrester, who for several years had charge of the mechanical department of the Broadway Pottery.” See “Virginia Pottery Leased,” Rockingham Register, December 12, 1895, p. 2. Further documentation can be found in Virginia Echo 8, no. 25 (November 15, 1895): 3. See also Fred W. Radford, A. Radford; Pottery: His Life & Works ([Columbia, S.C.]: Privately printed, 1973), p. 4.

Forester’s work at the Cowan Art Pottery is confirmed by a photo in the Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 12, 1922, Rotogravure section. A Forester descendant, Laura Griffiths, provided memories of Forester from Pete Johnson, whose father, F. H. Johnson, owned the Summitville Face Brick Company, where Forester worked. Email to author, February 17, 2018.

Leonard Forester, Certificate of Death, Division of Vital Statistics, Death Certificates and Index, December 20, 1908–December 31, 1953, State Archives Series 3094, Ohio Historical Society, Ohio.

Diary of Emanuel Suter, August 17, 1895, Suter Papers, Emanuel Suter Collection, Virginia Mennonite Conference Archives, Eastern Mennonite University, Harrisonburg, Va.

Leonard Forrester vs. Massanetta Art Pottery Company, Rockingham County Chancery Cause 1904-019, p. 30.

Evans, Art Pottery of the United States, p. 164.

“Its Wares a Success,” Evening News, January 9, 1903, p. 1.

Leonard Forrester vs. Massanetta Art Pottery Company, Rockingham County Chancery Cause 1904-019, p. 7. Forester undoubtedly was referring to producing ware in the style of Sarreguemines, a pottery-producing city in eastern France. A concise history of pottery in that region can be found at http://www.infofaience.com/en/sarreguemines-hist (accessed February 26, 2018).

Leonard Forrester vs. Massanetta Art Pottery Company, Rockingham County Chancery Cause 1904-019, p. 12.

Ibid., p. 11.

Ibid., pp. 29–30.

Ibid., pp. 6–7.

“To Operate Pottery,” Rockingham Register, December 6, 1904, p. 3; “Making Porcelain Ware,” Rockingham Register, May 16, 1905, p. 3.

Standard Porcelain Catalogue, Adamant Porcelain Company (Lmtd.) (New Market, Va.: Henkel & Co., n.d.).

Ibid.

“Making Porcelain Ware,” Rockingham Register, May 16, 1905, p. 3.

Standard Porcelain Catalogue, p. 2. C. S. Knowles was an electrical supply house. An account of the Pettingell-Andrews Company can be found in Electrical World 23, no. 17 (1894): 590. Established in 1906, the Electrical Products Company specialized in “all sorts of conduits, metal moldings, outlet boxes, locknuts and bushings.” B. Olney Hough, ed., American Exporter’s Export Trade Directory (New York: Johnston Export Publishing, 1920), p. 321.

Business Ledger #6 1906–1911, Papers of John E. Roller, acc. no. 9478, Special Collections Department, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va. (hereafter Business Ledger #6). For an account of the Brunt works, see “The Midsummer Meeting of the American Ceramic Society,” Clay Worker 46, no. 2 (August 1906): 136.

“Porcelain Plant Burned to Ground,” Harrisonburg Daily News, June 21, 1907, p. 1.

“Local and Personal,” Harrisonburg Daily News, August 2, 1907, p. 4.

“Mr. Tantum—Miss Zoncada,” Rockingham Register, December 5, 1906, p. 2.

Business Ledger #6.

Ibid. See Richmond, Virginia, City Directory, 1906, p. 907.

“Making Porcelain Ware,” Rockingham Register, May 16, 1905, p. 3.

Business Ledger #6. The history of the clay industry in Cornwall, England, is treated in great detail in Rita M. Barton, A History of the Cornish China-Clay Industry (Truro, Eng.: D. Barton Bradford Ltd., 1966).

“Improvements at Kennerly Properties,” Coal Trade Journal (1911): 683. See also Report of the Department of Mines of Pennsylvania, pt. 2 (Harrisburg, Pa.: Department of Mines of Pennsylvania, 1908), p. 237.

Business Ledger #6.

“A Year’s Work,” Rockingham Register, June 5, 1891, p. 3.

Harrisonburg Land & Improvement Co. vs. Rockingham Pottery Co., Rockingham County Chancery Cause 1901-022, p. 79.

The Harrisonburg Steam Pottery manufactured ware into the late 1890s. See Evans and Suter, A Great Deal of Stone & Earthen Ware, p. 27; and Suter, Potter’s Progress.