Jean-Baptist Lelarge III, side chair, Paris, ca. 1780. Beech; paint. H. 35 3/8", W. 18 1/8", D. 16 1/2". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Dessert service, Niderviller, France, ca. 1782. Porcelain (hard-paste). (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

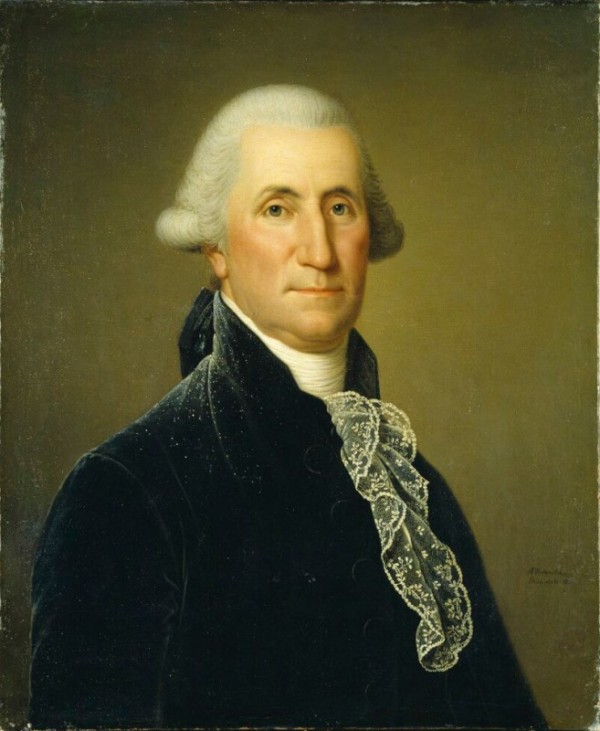

Adolf Ullrik Wertmüller (1751–1811), George Washington, United States, 1795. Oil on canvas. 25 1/2" x 20 13/16". (Courtesy, Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, Sweden; photo, Nationalmuseum, CC BY-SA.)

James Peale (1749–1831), portrait miniature of Martha Washington, United States, 1796. Watercolor on ivory. H. 1 5/8", W. 1 1/4". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Paul Kennedy.)

Bread basket, England or France, ca. 1783–1784. Sliver-plated copper. H. 11 1/2", W. 14 5/8". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Wine coaster, England or France, ca. 1783–1784. Silver-plated copper, wood, ivory. H. 1 3/8", Diam. 5". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Mark Finkenstaedt.)

Grand Salon from the Hôtel de Tessé, by Nicolas Huyot; carved by Pierre Fixon and (or) his son Louis-Pierre Fixon, Paris, ca. 1768–1772. (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Mrs. Herbert N. Straus, 1942, acc.42.203.1.)

François-Joseph Bélanger, elevation of a wall in the salon of the duchesse de Mazarin, Paris, ca. 1780. Pen, ink, and watercolor on paper. 16 5/16" x 10 7/8". (Copyright, Victoria and Albert Museum, London.)

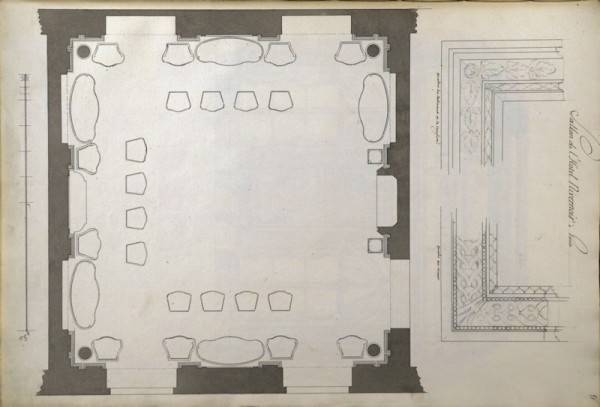

Erik Palmstedt, floor plan of the Hôtel du Châtelet, Paris, 1778–1780. Pen and ink on paper, 20 1/4" x 13 3/4". (Courtesy, Kungliga Akademien för de fria konsterna/Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Stockholm.) This plan shows the two-row circular configuration of seating with sieges meublants on the outside and sieges courants on the inside.

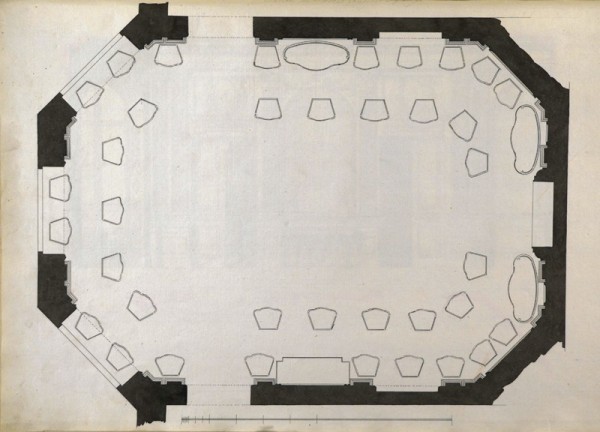

Erik Palmstedt, floor plan of the Hôtel du Nivernai, Paris, 1778–1780. Pen and ink on paper, 10 1/16" x 14 3/16". (Courtesy, Kungliga Akademien för de fria konsterna/Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Stockholm.) This plan shows the U-shaped grouping of side chairs in the center and the larger armchairs and sofas along the perimeter.

François Dequevauviller, after Niklas Lafrensen II, L’assemblé au salon (Gathering in a Salon), Paris, 1783–1784. Engraving and etching. 15 7/8" x 19 3/4". (Copyright, Victoria and Albert Museum.) The chairs have been arranged in small, informal groups for a variety of activities.

Robert Bénard, after Radel, Tapissier. Intérieur d’une boutique et differens ouvrages, plate 1, Encyclopédie, planches, sur les sciences, les arts libéraux, et les arts méchaniques, avec leur explication, vol. 9, edited by Denis Diderot et al. (Paris: Chez Briasson, 1762-1772). Engraving. 18 45/64" x 13 31/32". (Courtesy, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, University of Pennsylvania.)

Soup tureen and stand and preserves stand, Royal Porcelain Manufactory of Sèvres, France, 1782. Porcelain. Tureen, H. 13"; Stand, H. 17 3/4"; Preserves stand, H. 3 3/16". (Courtesy, White House Historical Association © 2000.) John and Abigail Adams probably acquired this china service during their time in France while John Adams served as the minister to France between 1784 and 1785.

Table, France, ca. 1785. Cherry; Brescia marble, brass. H. 28 1/16", W. 25 5/8". (Copyright, Thomas Jefferson Foundation, Monticello.) While residing in Paris, Thomas Jefferson commissioned several pieces of furniture, including this table a trois fin. Jefferson likely appreciated the table’s versatility. It has a removable circular tabletop, finished in leather and wool on opposite sides, that can be placed on top of the marble to expand the table’s functions: the marble surface might thus be used to serve drinks, the leather for writing, and the wool for playing games.

Side chair, France, ca. 1780–1790. Beech. H. 37 1/2", W. 17", D. 16". (Courtesy, John Jay Homestead State Historic Site, Katonah, New York, New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) In the fall of 1783, Parisians were captivated by the recent invention of the hot-air balloon. Sarah Livingston Jay witnessed several ascents, including the first hydrogen-powered balloon flight by Jacques Charles and Nicolas Robert. Many French craftsmen translated the popular balloon shape into furniture, jewels, and clocks. The Jays brought two such souvenir chairs back to the United States upon their return in 1784.

William Birch and Son, “View in Third Street, from Spruce Street, Philadelphia,” Philadelphia, 1800. Hand colored engraving on paper, 13" x 16". (Courtesy, Library Company of Philadelphia.) This view shows the William Bingham Mansion.

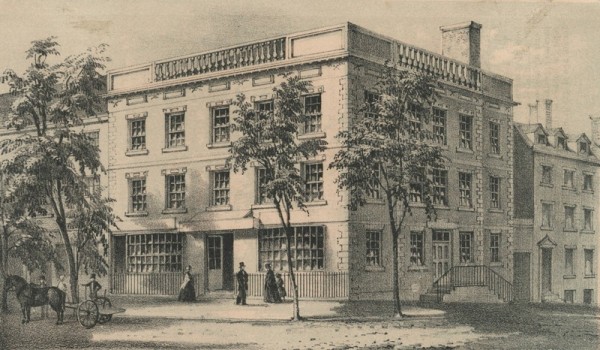

G. Hayward, “No. 3 Cherry Street, First Presidential Residence,” New York, 1853. Lithograph published in Valentine’s Manual [Manual of the Corporation of the City of New York, edited by D. T. Valentine]. (Courtesy, New-York Historical Society.)

Armchair (one of a pair), attributed to Thomas Burling, New York City, ca. 1790. Mahogany with oak; haircloth. H. 40", W. 28", D. 17". (Courtesy, Division of Cultural and Community Life, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.)

Presidential table wares, including the plateau, figural group of Venus and cupids and La Peinture, and Sèvres dinner service. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Plateau, France, ca. 1789. Silvered brass, mirrored glass, unidentified wood. H. 2 7/8", W. 17 3/8", L. 24". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Figural group of Venus and cupids, Duc d’Angoulême’s porcelain factory, France, ca. 1790. Biscuit porcelain (hard-paste). H. 15 1/4", W. 12 7/8". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

La Peinture, Duc d’Angoulême’s porcelain factory, France, ca. 1790. Biscuit porcelain (hard-paste). H. 11 1/4", W. 5", D. 3 1/2". (Courtesy, Stephen L. Zabriskie; photo, Gavin Ashworth.

Charles Burton, “Bunker’s Mansion House, Broadway, New York City: Study for Plate 5A of ‘Bourne’s Views of New York,’” (39–41 Broadway), New York, ca. 1831. Brown ink and wash, gray wash, and graphite on paper. H. 2 5/8", W. 3 1/2". (Courtesy, New-York Historical Society, bequest of Stephen Whitney Phoenix, 1881.10.)

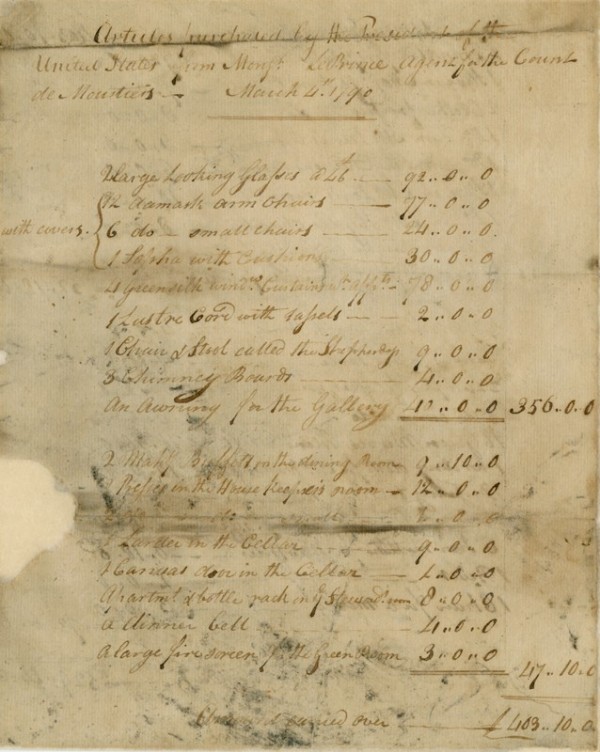

“Articles purchased by the President of the United States from Mons. Le Prince agent for the Count de Moustiers, March 4, 1790.” (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association.)

Ignazio Pio Vittoriano Campana, Marquise Jean-François-René-Almaire de Bréhan (Anne-Flore Millet), 1777. Watercolor on ivory. H. 2 11/16". (Courtesy, Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, Sweden; photo, Nationalmuseum, CC BY-SA.)

Marquise Jean-Françoise-René-Almaire de Bréhan (Anne-Flore Millet), George Washington, France, 1789. Watercolor on ivory. H. 2 3/4". (Courtesy, Yale University Art Gallery.) Madame de Bréhan was an accomplished pastelist and noted for the artistic decorations she created and displayed during lavish events at the minister’s residence. She made two miniatures of George Washington: the first shortly after her visit to Mount Vernon in the spring of 1788; and this one after her return to Paris in 1789.

Victor-Jean-Gabriel Chavigneau, lady’s writing table, France, ca. 1787–1789. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with white oak; marble, brass, silvered brass, leather, gold leaf. H. 41 1/2", W. 28 1/4", D. 19". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Dressing table, France, ca. 1760–1780. Mahogany with fir; marble, glass. H. 29", W. 37 5/8", D. 21". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Bidet, France, ca. 1790. Mahogany; leather, brass. H. 15 1/2", W. 18 1/4", D. 8 7/8". (Courtesy, Joseph James Ryan; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Dinner service, Sèvres factory, France, ca. 1780. Porcelain (hard-paste). (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Abraham Godwin, label of Thomas Burling, New York, ca. 1786–1793. Engraving on paper. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Collection of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Old Salem Museum and Gardens, Winston-Salem, North Carolina.)

W. L. Breton, “Residence of Washington in High Street, Philadelphia,” Philadelphia, ca. 1828-1830. Watercolor on paper. 9 13/16" x 7 1/2". (Courtesy, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.)

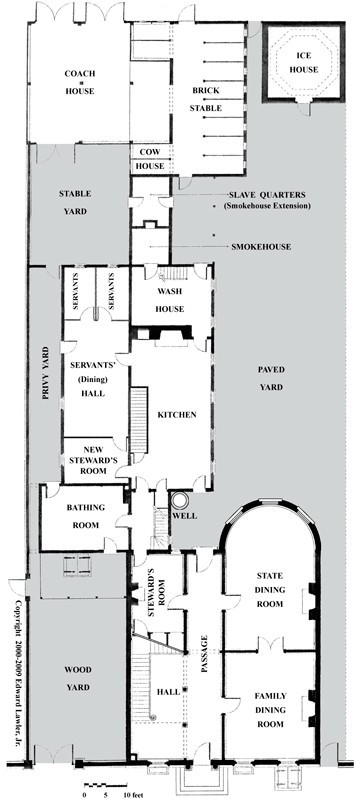

Conjectural floor plan (ground floor) of the President’s House in Philadelphia. (Courtesy, Edward Lawler Jr. © 2001-2019. All rights reserved.) The bottom is north.

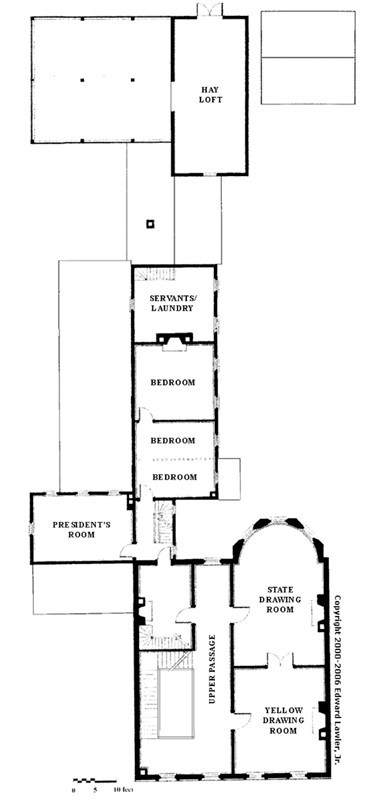

Conjectural floor plan (second floor) of the President’s House in Philadelphia. (Courtesy, Edward Lawler Jr. © 2001-2019. All rights reserved.) The bottom is north.

Conceptual sketch of the Green Drawing Room, President’s House, 190 High Street, Philadelphia. (Artwork by Wynne Patterson.) This is a visual interpretation that relies on such evidence as a fire insurance survey from 1773, Edward Lawler Jr.’s conjectural reconstruction of the floor plans, Washington’s inventory of the drawing room in 1797, personal correspondence of the president and his aides, as well as extant furnishings and architectural trimmings.

Mantelpiece, Philadelphia, ca. 1781. Wood; paint. H. 56 1/2", W. 79 1/2", D. 8 1/2". (Courtesy, Philadelphia History Museum at the Atwater Kent, Historical Society of Pennsylvania Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This mantelpiece was salvaged from the yellow drawing room in the President’s House prior to the building’s demolition in 1832, and the pulvinated frieze of banded foliage may represent the style of the woodwork on the mantel wall and above the doors in the green drawing room.

Looking glass, probably France, ca. 1788. Basswood; gesso, gold leaf, glass. H. 81 1/4", W. 43". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Looking glass, attributed to James Reynolds, Philadelphia, 1791–1797. Yellow poplar with Atlantic white cedar; gesso, gold leaf, glass. H. 50", W. 16 1/2". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Wall bracket, attributed to James Reynolds, Philadelphia, ca. 1791. White pine; gesso, gold leaf, wire, iron. H. 15 3/4", W. 12 1/4", D. 9". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Argand wall lamp, probably England, ca. 1790–1797. Silver-plated copper, brass, tin, glass. H. 16 1/8", W. 7 3/4", D. 4". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This lamp was retailed by Joseph Anthony.

George Beck, The Great Falls of the Potomac, United States, 1797. Oil on canvas. 44" x 55 1/4". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

George Beck, The Passage of the Pato’k thro’ the blew mountain, at the confluence of that River with the Shan’h, United States, 1797. Oil on canvas. 39" x 49 5/8". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

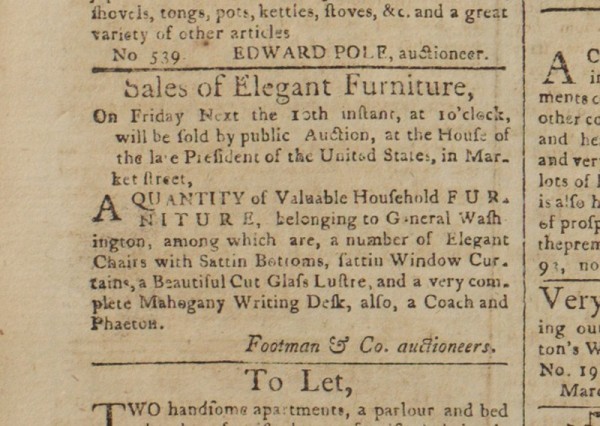

“Sales of Elegant Furniture,” advertisement in Claypoole’s American Daily Advertiser, Philadelphia, March 8, 1797. (Courtesy, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.)

New Room, Mount Vernon, Mount Vernon, Virginia. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, attributed to John Aitken, Philadelphia, ca. 1797. Mahogany and light wood inlay with unidentified secondary wood. H. 37 7/16", W. 20 5/8", D. 18 3/4". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Sideboard, attributed to John Aitken, Philadelphia, ca. 1797. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, and light and dark wood inlays with white pine, tulip poplar, and unidentified softwood. H. 37 5/8", W. 71 7/8", D. 26 11/16". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Bergère, attributed to Jean-Baptiste Lelarge, Paris, ca. 1780. Beech; paint, brass. H. 35 1/8", W. 25 1/2", D. 22 3/8". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Footstool, attributed to Georges Bertault, Philadelphia, ca. 1793. Ash with sweet gum and beech; silk, flannel, haircloth. H. 18", D. 16 3/4". (Courtesy, Tudor Place Historic House and Garden; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Footstool, attributed to Georges Bertault, United States, ca. 1788–1790. Mahogany, walnut, and pine; leather. H. 12", W. 23", D. 23". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Armchair, France or United States, ca. 1790–1795. Unidentified woods; paint, silk. H. 34 1/2", W. 24", D. 21 1/2". (Courtesy, Museum of the American Revolution; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing the plaque on the armchair illustrated in fig. 50. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The inscription reads: “Presented after Washington’s death, by the members of his Family to Gen. Sam Smith, after Gen. Smith’s death, purchased by Jno. B. Cannon, Baltimore, Md.”

Armchair, possibly France, 1790–1800. Walnut. H. 38 1/2", W. 24", D. 18 3/4". (White House Collection, Courtesy, White House Historical Association © 2019; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Armchair, France or United States, 1790–1795. Beech; paint. H. 31 3/4", W. 23 3/8", D. 20 1/4". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Sofa, probably France, ca. 1795–1800. European walnut; paint, silk. H. 39 7/8", W. 70", D. 23 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

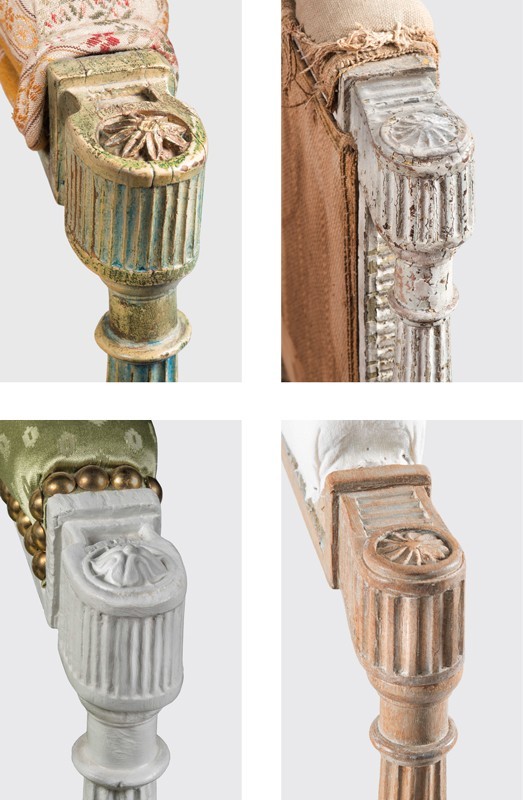

Details of the arm terminals of the chairs and sofa illustrated in (from left to right) figs. 50, 54, 53, 52. (Photos, Gavin Ashworth.)

Details of the arm supports of the chairs and sofa illustrated in (from left to right) figs. 50, 54, 53, 52. (Photos, Gavin Ashworth.)

Armchair, probably France, 1785–1790. Beech; silk. H. 38 1/2", W. 24", D. 18 3/4". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Armchair, possibly United States, ca. 1790–1810. Ash; paint, gold leaf, silk. H. 35 1/2", W. 21", D. 20". (Courtesy, Delaware Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Armchair, France or United States, ca. 1785–1797. Beech; silk, linen, haircloth, paint, gold leaf. H. 34 1/4", W. 22 3/16", D. 22". (Courtesy, Connecticut Historical Society, lent by Mrs. Arnold G. Dana, 1983.57.0.)

Jean-Baptiste Lelarge III, bergère, Paris, ca. 1780. Beech; paint, silk. H. 39 3/8", W. 28 1/2", D. 26 1/2". (Courtesy, Chateaux de Versailles et de Trianon, Versailles, France. Copyright, RMN-Grand-Palais/Art Resource, NY ; photo, Christophe Fouin.)

Jean-Baptiste Lelarge III, fauteuil, Paris, ca. 1780. Beech; paint, silk. H. 38 3/16", W. 26 7/32", D. 23 15/64". (Courtesy, Chateaux de Versailles et de Trianon, Versailles, France. Copyright, RMN-Grand-Palais/Art Resource, NY; photo, Christophe Fouin.)

Chaise, Paris, ca. 1809. Beech ; paint, silk. H. 36 29/64", W. 19 11/16", D. 18 45/64". (Courtesy, Chateaux de Versailles et de Trianon, Versailles, France. Copyright, RMN-Grand-Palais/Art Resource, NY; photo, Franck Raux.)

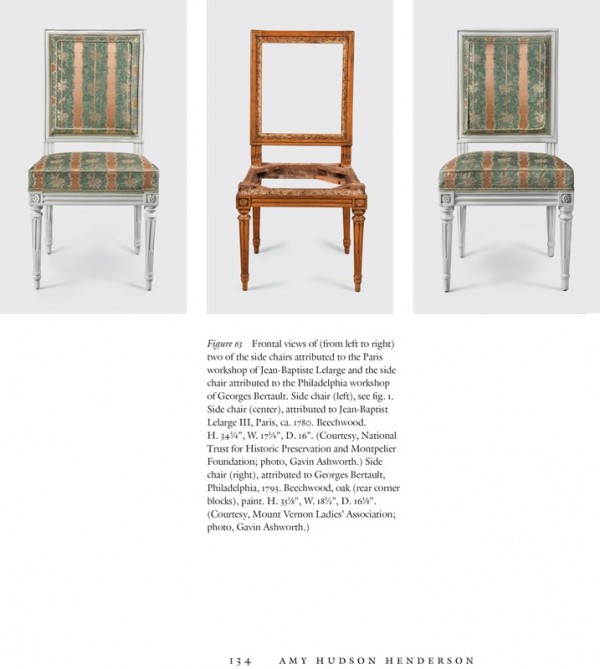

Frontal views of (from left to right) two of the side chairs attributed to the Paris workshop of Jean-Baptiste Lelarge and the side chair attributed to the Philadelphia workshop of Georges Bertault. Side chair (left), see fig. 1. Side chair (center), attributed to Jean‑Baptist Lelarge III, Paris, ca. 1780. Beechwood. H. 34 3/4", W. 17 3/4", D. 16". (Courtesy, National Trust for Historic Preservation and Montpelier Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Side chair (right), attributed to Georges Bertault, Philadelphia, 1793. Beechwood, oak (rear corner blocks), paint. H. 35 1/8", W. 18 1/2", D. 16 5/8". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

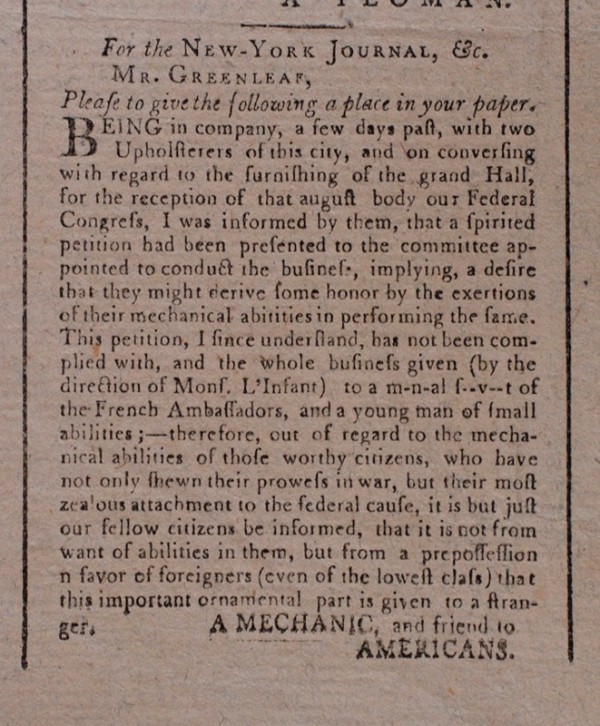

Editorial, New York Journal, March 28, 1788. (Courtesy, Library of Congress; photo, author.)

Armchair, New York, ca. 1788. Mahogany. H. 36", W. 23 1/2", D. 20". (Courtesy, New-York Historical Society.)

Armchair, attributed to Georges Bertault and Adam Hains, Philadelphia, 1793. Mahogany, ash. H. 35", W. 23", D. 19 3/4". (Courtesy, Longfellow House-Washington’s Headquarters, National Park Service; photo, Andrew Davis.)

Detail showing the stamp on the side illustrated on the far left in fig. 63.

Five of the six surviving pieces from George and Martha Washington’s Green Drawing Room suite.

Abigail Adams likely determined the fate and historical fortunes of the French furniture suite that once graced George and Martha Washington’s presidential drawing room when, as the incoming first lady, she declared to her husband in February 1797: “I want not a stick of it at the close of the term” (fig. 1). Resolved that Congress—and not she and John—should pay to refurnish the president’s residence after the Washingtons retired to Mount Vernon that spring, Abigail instructed her husband to turn down George Washington’s offer to purchase the fine French chairs and settee the Washingtons had assembled during George’s presidency. As John informed his wife, the president personally owned the furniture in the drawing room, besides many items throughout the house, and now “all the Glasses, ornaments, kitchen furniture, the best Chairs, settees, Plateaus &c.” had to be replaced. The Adamses, however, were determined to live modestly and within the allowance Congress provided for household furnishings and expenses—even if it meant, as John put it, they “shall be put to great difficulty to live and that in not one third the Style of Washington.” As a result, they declined to purchase the “Articles in the Green Drawing Room” proffered by Washington. The Adamses’ decision thus set in motion the first auction of presidential furniture and, ultimately, the widespread dispersal of what would become the famed—and elusive—drawing room suite.[1]

More than 200 years after the Adamses’ decision, historians continue to search for those auctioned chairs and settee in the French taste, as they unquestionably give insight into the Washingtons and their carefully considered furnishing choices. Just as pertinent, however, is what this famous suite reveals about the material and philosophical decisions many members of the founding generation faced when they set out collectively to build their new republic. In essence, the story of a few chairs brings attention to several key questions these men and women faced as they transitioned from a confederation to a more mature nation. For instance, would the leaders of this new nation follow the materials and manners of Britain and Europe, or would they embark on something entirely new? How would they define moderation and simplicity as well as extravagance and superfluity? And, how would these concepts impact the development of a cohesive national identity? Scholars seek to identify and authenticate the pieces in this drawing room suite because their journey from an upholsterer’s workshop in Paris to a workshop in New York (after being damaged in the Atlantic crossing), their service in the elevated salons of a French ambassador and then an American president, and finally their legacy as souvenirs after that 1797 auction, attest to—and visually document—the emerging and competing values that profoundly shaped Federal America.[2]

Today there is considerable confusion about what the Washingtons’ French furnishings looked like since there are multiple contenders that vary in style, materials, and provenance. New research into written records and the physical evidence of extant pieces now allows scholars to clarify several misattributions and to state with greater authority which of these pieces were once part of the set. According to historical records, the core of the suite comprised twelve armchairs, six side chairs, and a sofa—all upholstered in a green, flowered silk damask and made in Paris by Jean-Baptist Lelarge—and imported into the United States by then-French ambassador the cômte de Moustier. Washington purchased the suite in 1790 and three years later commissioned Georges Bertault, a French émigré upholsterer in Philadelphia, to make an additional six side chairs and two stools in a matching green silk. Ever since the twenty-four green chairs and a sofa were purportedly sold at auction in 1797, there has been tremendous interest in the pieces as relics of Washington, his presidency, and the style of his and Martha’s republican court. There has also been uncertainty as to which “relics” are authentic.[3]

This article relates a broad story about the Washingtons and how they came to be interested in, and have access to, a wide array of French decorative objects. The narrative explores how the Washingtons navigated the changing perceptions of what kinds of material display were appropriate, desirable, and even necessary, in a nascent republic; the role of American diplomats and tourists in introducing the French taste to their countrymen; the French craftsmen responsible for their suite of furniture and shopping practices in ancien régime Paris; and finally, what the green drawing room in the President’s House in Philadelphia looked like during the Washingtons’ tenure. By contextualizing the suite in terms of its style, function, and evolution in the salons of Paris, New York, and Philadelphia, we can analyze more deeply the cultural and political vision the Washingtons and their contemporaries shared for their country.

The story of the Washingtons and their consumption of French fashions should rightly begin at the close of the Revolution, when Americans were seeking ways to rebuild their communities and homes after seven long years of war. It was in the early 1780s when the Washingtons were introduced to the elegant manufactures of Paris and had their first taste of what the luxury capital of Europe had to offer. Through the friendships they formed with French officers serving in the war, they were exposed to French aristocratic manners. In 1782 Martha received a “Present of Elegant China” from a titled French officer, Adam-Philip, comte de Coustine, in appreciation for a dinner he attended at Mount Vernon (fig. 2). The tea and coffee service was likely a sampler set since each piece is enameled with a different combination of ribbons, swags, garlands, bands, and scrolls yet linked by the monogram “GW.” In one gesture, the comte de Coustine demonstrated his admiration for Gen. Washington and his family while simultaneously advertising the wares of the Niderviller porcelain factory, of which he was the principal owner. In return, the Washingtons joined a select community of Americans with access to the products of France. Equally important, they now had friends with knowledge of, and a taste for, such refined wares.[4]

The following year, as the war ended and Gen. Washington prepared to return to Mount Vernon and resume life as a private citizen, he initiated a plan to enhance the French porcelain service with a collection of new furniture, dinner china, and silver wares. Accordingly, he did what he had often done in the past: he sought out trusted friends and family members for advice on shopping. “There is another thing likewise which I wish to know,” he wrote to his nephew Bushrod Washington from his encampment at Rocky Hill, New Jersey,

& that is, whether French plate is fashionable & much used in genteel houses in France & England; and whether, as we have heard, the quantity in Philadelphia is large—of what pieces it consists, & whether among them, there are tea urns, Coffee pots, Tea pots, & the other equipage for a tea table, with a tea board, Candlesticks & waiters large & small, with the prices of each.

Bushrod was then studying law in Philadelphia and a frequent guest in the home of Samuel and Elizabeth Willing Powel, among the city’s more esteemed and wealthy citizens and dear friends to the Washingtons. One presumes Bushrod was happy to share his observations on what was fashionable in the homes of the city’s genteel families, many of whom he met through the Powels. Furthermore, he may have been able to visit shops along High Street to enquire about availability. Although there is no record of Bushrod’s response to his uncle, he likely wrote that yes, such items were fashionable, but no, not readily available in post-war Philadelphia, because the next letter Washington composed on the subject was to his French brother-in-arms, the marquis de Lafayette, requesting his assistance in procuring “everything proper for a tea table” in silver plate.[5]

Like so many of their colonial peers, the Washingtons (figs. 3, 4) were long used to Great Britain serving as their guide in all things cultural and material. In fact, prior to the war, few Americans had access (through either commercial or personal ties) to household goods that did not originate within the British Empire. All of this changed when the Confederation Congress dispatched diplomats to the courts of Europe; word of fashions on the Continent began to trickle home, first in personal correspondence and then when the goods themselves eventually arrived as gifts or prized possessions. Upon the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1783, trade with foreign nations was legalized, and Americans eagerly turned to France to see what she had to offer in the domestic line. Indeed, post-war negotiations among the British, French, and Americans were barely over before Washington initiated his correspondence with Lafayette.[6]

Washington could not have selected a better friend than Lafayette to help him with his shopping, for the marquis had returned to France during the treaty negotiations with the view of being an unofficial American representative at the court of Louis XVI. Lafayette’s passion for the well-being of both countries led him to believe that a policy of open markets was in the best interests of both nations. In his view, this was the only viable way for America to rebuild its commerce and thus repay its debt to France. Ideally, the French would provide a market for America’s raw materials in exchange for manufactured goods, and if France acted quickly to open her markets, there was the added benefit of financially cutting off the British from her former colonies. Lafayette surely recognized that there could be no better way to show off the variety and beauty of French wares than by sending examples to the Washingtons at Mount Vernon.[7]

Washington knew his friend well and understood that he would be delighted to serve as a proxy shopper. Yet Washington still felt the need to justify the commission, assigning the following reasons for recruiting Lafayette as his delegate:

1st. then, because I do not incline to send to England (from whence formerly I had all my goods) for any thing I can get upon tolerable terms elsewhere.

2nd. Because I have no correspondence with an[y] Merchants or artisans in France.

3d. If I had, I might not be able to explain so well to them, as to you, my wants, who know our customs, taste & manner of living in America. and 4th Because I should rely much more upon your judgment and endeavors to prevent impositions upon me, both in the price & workmanship, than on those of a stranger.

It is hard to know which of the reasons was most important—breaking ties with England, getting the best price, or having a friend with good judgment to serve as a style guide—yet the last may well have been uppermost in Washington’s mind. At the start of the letter he also noted that “as I am not much of a connoisseur in, & trouble my head very little about these matters, you may add anything else of the like kind which may be thought useful & ornamental.” Washington was looking for guidance on what was fashionable and appropriate and evidently ready to put himself in the hands of the marquis for his first commission of French wares.[8]

The memorandum Washington included at the end of the letter documents an extensive order, and one wonders what role Martha played in the process, especially in light of Washington’s admission that he thought little upon these matters. “A List of Plated Ware to be Sent to General Washington, by the Marq.s de la Fayette,” with the following descriptions, could very well be imagined as Martha communicating with Lafayette’s wife, Adrienne, who likely assisted her husband with the shopping:

Everything proper for a tea-table, & these it is supposed may consist of the following Articles: A Large Tea salver, square or round as shall be most fashionable; to stand on the Tea table for the purpose of holding the Urn, teapot, Coffee pot, cream pot, China cups and saucers &ca.

A large Tea-Urn, or receptacle for the water which is to supply the tea pot, at the table. 2 large Tea pots, and stands for Ditto, 1 Coffee Pot and stand, 1 Cream Pot, 1 Boat or Tray, for the Tea spoons, 1 Tea-chest, such as usually appertains to tea or breakfast tables, the inner part of which, to have three departments, two for tea’s of different kinds, the other for Sugar. If any thing else should be judged necessary it may be added, although it is not enumerated.

Also, Two large Salvers, sufficient to hold twelve common wine glasses, each.

Two smaller size Do for 6 wine glasses, each.

Two Bread baskets, middle size.

A Sett of Casters, for holding, oil, Vinegar, Mustard &ca.

A Cross or Stand for the centre of the Dining table.

12 Salts, with glasses in them.

Eight Bottle sliders.

Six large Goblets, for Costers.

Twelve Candlesticks. Three pair of snuffers, and stands for them.And anything else which may be deemed necessary, in this way. If this kind of plated Ware will bear engraving, I should be glad to have my arms thereon, the size of which will, it is to be presumed be large or small in proportion to the piece on which it is engraved.

The marquis and marquise de Lafayette were pleased to help the Washingtons establish connections with Parisian silver merchants, and by the spring of 1784 the Lafayettes had done their best to fulfill the order. Surviving pieces include a pierced, oval bread basket with engraved leaves, wheelwork flowers, and swags, as well as a similarly decorated bottle slider, or coaster, both done in the delicate neoclassical style then taking over cosmopolitan Europe (figs. 5, 6). With these wares as exemplars, the Washingtons and Lafayettes began to ponder the many commercial advantages that could result from a strong Franco-American trade relationship.[9]

The Washingtons were hardly alone in turning to France for commercial and cultural opportunities. By the time the Treaty of Paris was ratified on September 3, 1783, an influential band of American diplomats, businessmen, and tourists had gathered in the French capital and were becoming acquainted with Paris and her material world first hand, an experience that would profoundly impact them and their country’s future. The list of Americans in Paris after the war is long and distinguished and includes such individuals as Benjamin Franklin, John and Sarah Livingston Jay, John and Abigail Adams and their children (John Quincy, Charles, and Nabby), Thomas Jefferson, William and Anne Willing Bingham, Alice DeLancey Izard, Gouverneur Morris, Abraham Swan, Henry Laurens, and Matthew and Anne Richardson Ridley. This expatriate group used diplomatic channels and ties with French officers and ministers, forged during the war, to gain entrée into the elite levels of French society. It was there—in the salons of French hostesses, along the paths of the Tuileries gardens, shopping in the Palais Royal, or visiting the theater—that they carefully observed French manners, hospitality, and style of living. It was also in Paris that these Americans began to form opinions about which (if any) French manners, and what material goods that supported politeness and sociability, would be best suited in a republic back home. A deeper look at their experience in Paris is therefore fundamental to the story of the Washingtons’ drawing room chairs. Collectively, the Lafayettes and expatriate friends helped the Washingtons develop an appreciation for French decorative arts as well as the art of polite sociability, which consequently influenced the appearance of, and protocols in, the president’s house.[10]

One could argue that among the many lessons Americans learned during their years in Paris was how to recognize the invisible ties among the French drawing room, worldly sociability, and the Enlightenment. As historian Antoine Lilti explores in his study of eighteenth-century Paris, behaviors in the drawing room had much to do with evolving notions of status, since men of noble birth could no longer rely on military valor or their membership in the nobility to solidify their high place in society. Rather, aristocratic prestige rested on being a l’homme du monde or “man of the world,” capable of demonstrating mastery of the cultural practices of polite society. In salons—the appartements de societé or the room in a Paris townhouse where hosts received guests—men and women could practice, perfect, and demonstrate their worldly sociability and lay claim to this prestige. Moreover, in contrast to the French royal court, salons were spaces in which individuals of varied backgrounds (aristocrats, men of letters, patrons of the arts and belle lettres, diplomats, members of government, financiers, and foreign visitors) could assemble and converse on a wide range of topics, all the while exhibiting wit, knowledge, and generosity to others. The salon was ultimately both a physical space and a society composed of men and women, based in private homes and often orchestrated by women, where individuals made (or lost) their reputations for gentility and civility.[11]

Tastefully decorated salons were integral to the demonstration of prestige and worldly hospitality; elegant furnishings not only signaled a host’s financial resources but also his or her commitment to what was known as l’art de vivre. Historian Joan DeJean has shown how this concept, the art of living, grew out of Greek Stoic philosophy and by the late eighteenth century could be linked directly to the decorative arts and manufactures of France. Drawing on related strands of Enlightenment thought, DeJean argues that when civilizations began to measure themselves by their degree of material, social, and cultural advance, then enhancements in architecture and household furnishings—such as improved seating furniture, more efficient lighting, or the convenience of indoor plumbing—were an indication of rational thought and a society’s ability to make continual progress. She sees the French as taking this idea one step further and states “it was only in a comfortable environment that individuals could use rational thinking (as opposed to religious faith) to transform their way of life.” The relationship then, among French furniture design, materials, and use at the end of the ancien régime is clear: the French style came to be synonymous not just with quality, beauty, and comfort but also with rational thinking and worldly sociability.[12]

Letters and journal entries by Abigail and Nabby Adams, John and Sarah Jay, Thomas Jefferson, and Gouverneur Morris all attest to the importance—and indeed brilliance—of this salon culture in 1780s Paris. As members of the diplomatic corps, they received their education in French manners in the afternoon salons and evening dinner parties of some of America’s greatest champions, including the marquis and marquise de Lafayette, the marquis and marquise de Chastellux, the duchesse de Mazarin, monsieur and madame Necker, madame de Genlis, madame de Ségur, madame de Helvetius, and madame de Tesse. In these elaborately decorated rooms, such as the grand salon from the Hôtel de Tesse (fig. 7), the Americans observed how to blend politics and politeness. They discovered which decorative furnishings lent support to their hosts’ efforts to create spaces of distinction and comfort, on the one hand, and how those furnishings were best arranged to facilitate rational conversation and entertainment on the other.[13]

Those lessons in decorating revealed the importance of creating visual and social harmony throughout the salon. By the 1780s the soft, curvaceous rococo style popular under Louis XV had given way to the geometry and motifs of the classical world favored by Louis XVI and his court. Well-appointed social spaces were filled with groups of objects that matched and were designed to work as a whole. New, specialized furniture forms—sofas, and chairs of varying shapes and sizes; tea, card, and pier tables; looking glasses and picture frames—coordinated with one another in materials, ornamentation, color, and texture as well as with the architectural fixtures, as demonstrated in the elevation by François-Joseph Bélanger for the salon of the duchesse de Mazarin illustrated in figure 8. Upholstery on chairs matched the window treatments. Both were likewise in accord with the color of the walls, whether they be covered with paint or wallpaper. Of all the objects in the salon, seating furniture was paramount. Chairs in this period were designed for a multitude of functions and consisted of two ranks: armchairs and side chairs. Large armchairs and sofas with flat backs (called sieges meublant) were placed along the walls around the room, while side chairs and lighter cabriolet armchairs (or sieges courants) were positioned either in a U or circular fashion to facilitate group conversation or in small clusters for games and private discourse (figs. 9-11). By some accounts, the formal etiquette of the French salon dictated that guests did not sit in the sieges meublant around the perimeter of the room but only in the sieges courants, and that the host and hostess reserved for themselves yet another form of armchair, the bergère, which was stationed on either side of the hearth, the place of honor. Symmetry, hierarchy, and harmony were the underlying principles in this French neoclassical decorating scheme.[14]

There was never any question in the minds of American diplomats that their world was quite different from the one they found in these aristocratic townhouses, yet they also realized that many aspects were adaptable and transferable. Subsequently, when they furnished their own homes in Paris to receive guests as part of their diplomatic obligations, they gave careful consideration to which furnishings they might bring home after their mission. It is interesting to note that among their first considerations was whether to buy French or British furnishings; both were available in 1780s Paris due to the Anglomania sweeping through many aristocratic households. Indeed, there was an equal degree of Francomania in London as British tourists, artists, and diplomats had likewise flocked to Paris at the close of the war intent on experiencing l’art de vivre and bringing home to England that quintessential French style.

Cross-pollination and exchange between the two countries was evident in everything from furniture, silks, and silver wares to garden design, scientific equipment, and porcelain. Nabby Adams, for instance, enjoyed two visits to the Paris home of the duc de Chartres—one of the more notable collectors of things English—and commented how “The Duke has built, finished, and furnished the house in the English style,” and she found the rooms “truly elegant.” And in London, cabinetmakers were heeding the advice of George Hepplewhite and Thomas Sheraton and making delicate, neoclassical drawing room chairs in the French taste: lightweight, upholstered in silk, and painted. The lesson learned from these examples was that sometimes the French, and sometimes the British, did things “better,” and it was the responsibility of savvy American consumers to decide which country’s manufactures suited their lifestyle.[15]

Gouverneur Morris nicely articulated the process Americans went through to find the right balance between the manufactures of France and England. In a 1792 letter to Thomas Pinckney, who was then serving as U.S. ambassador to Great Britain, Morris offered this advice:

In respect to Furniture there is no doubt but that rich and elegant Furniture can be had in this Town [Paris] for much less than London, but plain and neat Furniture can be had rather cheaper and a great deal better with you. The Stile of living in the two Countries is so different that I have found myself as it were oblig’d to lay out a great Deal of money in Furniture which I should hardly know what to do with in America, Whereas you can in London get Articles which will answer well to take with you.

Morris was not alone in his assessment. A popular travel journal aimed at advising German tourists similarly instructed readers intent on buying goods abroad: “English furniture is almost without exception solid and practical; French furniture is less solid, more contrived and more ostentatious.” And even the Frenchman and social observer Louis-Sébastien Mercier wrote: “England may seem to have more to offer in the way of peacefulness and the decent conduct of domestic life; but then, what prevents the Frenchmen from enjoying these blessings? They might be his if he would choose comfort and commodity rather than his present silly luxury, which kills true happiness and wastes energy and money.” Despite such a chorus of criticism, Paris remained the shopping destination for wealthy tourists, especially those making the Grand Tour, as it was the fashion center of Europe; and for every warning against buying French, there was an equally happy shopper who did so. The Baroness d’Obkirche, for instance, confided in her diary, “We did not know where to put all our purchases, which accumulate, one scarcely knows how, in a city like Paris.” So, shop in Paris these Americans did.[16]

Morris may have warned Pinckney away from investing in French goods, but he, like his predecessors Thomas Jefferson and Abigail Adams, was a seasoned shopper in Paris and knew what was available and at what price. They all spent time visiting the marchands merciers in the Palais Royal and along the rues Saint Honoré and Saint Martin, the heart of the high-end trade in new and used luxury goods, as well as the marchands de meubles (cabinetmakers), tapissier (upholsterers), and wallpaper and porcelain manufactories scattered throughout the city and surrounding villages (fig. 12). They visited shops for the social experience as well as for purchasing much needed household furnishings. Jefferson, it seems, furnished his Paris town-house top to bottom in the French style, while Abigail Adams just rented furniture and used her resources selectively to purchase table and bed linens, tea and dinner china, glass, and plate (fig. 13). Abigail complained about prices and that “Everything which will bear the name of elegant, is imported from England, and, if you will have it, you must pay for it, duties and all.” But Paris shops were renowned for both the quality and novelty of their wares. Indeed, there was a strong second-hand market that kept prices accessible for non-aristocrats. Ultimately, each of these Americans learned how to compare style, quality, cost, and suitability and to weigh their options with an eye both to their immediate needs in Paris and their future interests back home.[17]

Over the course of the next several years these American diplomats and travelers gradually made their way back to Massachusetts, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and South Carolina, their minds filled with ideas and their trunks laden with goods. One cannot pass on the opportunity to reflect on the sheer amount of furnishings Jefferson shipped home in 1790: eighty-six crates filled with bedsteads, tables and chairs; paintings, looking glasses, wallpaper, and window curtains; silverware utensils and serving pieces, and a silver-plated plateau; dinner china, tea china, and decorative porcelain figurines for the table; clocks, watches, scientific instruments; and myriad other goods such as the Brescia marble table illustrated in figure 14. Philadelphians William and Anne Bingham, who completed a Grand Tour between 1783 and 1786, similarly returned with enough furnishings from Paris and London to outfit their 18,000-square foot mansion on South Third Street, then the largest townhouse in America. So notable was their taste that a visiting Frenchman remarked that the Binghams “displayed a luxury and a magnificence that could not be more French. He has built a very beautiful house that he is furnishing with the greatest elegance.” Whether on a small or grand scale, these diplomatic families shipped home enough French goods (and British-made goods in the French style) for themselves, their families, and their friends to make a statement about their newly acquired taste (fig. 15).[18]

Material souvenirs were only part of the imports, for these well-traveled Americans also returned with an acute awareness of French manners and the rituals of hospitality. Nabby Adams, who carefully chronicled the individuals she met while living in Paris, London, and New York—and was therefore well versed in behaviors at home and abroad—could appreciate a woman such as Anne Bingham for having mastered the art of conversation, or Sarah Jay in her pleasures of the French table. “Mrs. B. gains my love and admiration, more and more every time I see her,” Nabby confided in her journal:

she is possessed of more ease and politeness in her behavior than any person I have seen. She joins in every conversation in company; and when engaged herself in a conversation with you, she will, by joining directly in another chit chat with another party, convince you, that she is all attention to everyone.

The ability to converse freely, draw others into the conversation, and make everyone feel special was considered one of the highest accomplishments of the Parisian salonnière. Anne Bingham would show her friends in Philadelphia how it was done.[19]

In New York, Sarah Jay likewise introduced French customs. Nabby noted that when the Jays hosted a party for the diplomatic corps in the late 1780s, “the dinner was à la Française and exhibited more of the European taste than I expected to find.” These little insights on conversational style and how a table was set reveal the quiet way some of the wealthier, more influential families in the United States were adopting French customs. Before long, these were the families who would be shaping the political discourse during the Constitutional Convention and the creation of the federal government, and their time in Paris would be felt. Abigail Adams, who forever despaired at the costs tied to hospitality, never underestimated its worth. She saw clearly how all the lessons learned in the Paris salon—polite sociability, civility, and harmony—were put to use for diplomacy: “More is to be performed by way of negotiation, many times, at one of these entertainments, than at twenty serious conversations.” These Americans who ventured across the Atlantic to secure independence came home with the materials and manners of polite sociability that they would use—just as much as the trade agreements—to build and define their new republic.[20]

This interest in French manufactures and the French style remained steady in the years following the American Revolution. Many Americans saw the fine examples brought back by the diplomats, but they increasingly also had the opportunity to purchase French goods themselves. Importation statistics indicate that Great Britain continued to dominate the post-war American commercial market, but French furnishings did find their way into ever greater numbers of American homes. Few families, of course, spent time personally shopping in Paris and London or, as the Binghams had, turned their homes into showpieces of European elegance and style. Yet some did have friends abroad who served as proxy shoppers. Robert and Mary White Morris, Samuel and Elizabeth Powel, and James and Dolley Todd Madison relied variously on Gouverneur Morris, Sarah Jay, and James and Elizabeth Kortright Monroe to fulfill commissions, just as the Lafayettes had for the Washingtons. In this way Americans at home acquired French seating and case pieces (bedsteads, chairs, commodes, and tables); lighting devices (silver-plated candlesticks and Argand lamps); looking glasses; porcelain dinner and tea china; decorative plateaux with porcelain figurines, vases, and flowers; silk (damask and velvet for seating upholstery and plain silk for window treatments); and clocks.[21]

Finally, for those families with no international ties, there were always local shopkeepers and émigré craftsmen eager and willing to introduce them to the French taste. By 1787 cabinetmaker and carver William Long, recently arrived from London, advertised that he made “French Sophas in the modern taste” and had “Cabriole and French Chairs on reasonable terms.” In 1790 upholsterer Francis De L’Orme, lately from Paris, began boasting that he made furniture in “the most fashionable Taste, . . . all in the English or French style” and that he had an “assortment of Handsome Paper-Hangings from Paris.” Craftsmen’s advertisements suggest that by the 1780s, furniture and housewares in the United States were readily distinguishable by country of origin and that there was a French versus a British style on this side of the Atlantic Ocean. Consumers were therefore increasingly faced with a choice: how did they want their American homes to look? Further, what were they signaling if they invested in one style over another, or between things made in Europe versus in America? As the United States was moving closer to reorganizing itself as a more unified, federal body, what would it mean for its founders to embrace the French art de vivre?[22]

George Washington could very well have been mulling over such questions following the summer of 1787, when he resided in Philadelphia during the Constitutional Convention and was a daily witness to the fine French furnishings his friends the Binghams, Morrises, and Powels were displaying in their townhouses. With the aid of such companions as the comte de Coustine and the marquis de Lafayette, Washington had already been introduced to French manners and select examples of porcelain and silver table wares; but one can imagine the Binghams’ home was an entirely new experience for him (fig. 16). Polish statesman Julian Ursyn Niemcewicz left this account of visiting the Binghams’ grand house on South Third Street:

One mounts a staircase of white native marble. One enters an immense room with a sculptured fireplace, painted ceiling, magnificent rug, curtains, armchairs, sofas in Gobelins of France. The dinner is brought on by a French cook; the servants are in livery, the food served in silver dishes, the dessert on Sevres porcelain. The mistress of the house is tall, beautiful, perfectly dressed and has copied, one could not want for better, the tone and carriage of a European lady . . . . In a word, I thought myself in Europe. This house, as opulent as it is, would never be pointed out in the big cities of Europe, but here it attracts attention, criticism and envy; and woe for the country if it ceases to astonish, if it ceases to be pointed out.

Although Washington did not leave a similar account of his impressions (indeed, all he noted on his first visit in May 1787 was “Dined, and drank Tea at Mr. Binghams in great Splender”), he surely understood that the Binghams and their French taste represented an entirely new commitment to the cosmopolitan manners of Paris. Is it possible that the Binghams’ ostentation and obsession with Europe could have caused him to reconsider what place French-made things should have in the nascent republic?[23]

As the months ticked by and the delegates to the Constitutional Convention re-settled themselves in at home and waited for the states to ratify the constitution, Washington began to put into words his evolving thoughts about how much Americans should look to France for models of taste. Perhaps in anticipation of the coming election (in which he knew, whether he wanted to admit it openly or not, that he would be elected the first president), Washington spent time reflecting on American manners and the influence the new executive would have in shaping them. In response to a letter from his friend Annis Boudinot Stockton, in which she had congratulated him on the likely passage of the constitution, he returned the compliment by observing that while American women had been essential to the colonies in securing independence from Great Britain, they could now have an even more important role in the creation of the federal government. “I think the Ladies are in the number of the best Patriots America can boast,” he shared in August of 1788:

And now that I am speaking of your Sex, I will ask whether they are not capable of doing something towards introducing federal fashions and national manners? A good general government, without good morals and good habits, will not make us a happy People; and we shall deceive ourselves if we think it will. A good government will, unquestionably, tend to foster and confirm those qualities, on which public happiness must be engrafted. Is it not shameful that we should be the sport of European whims and caprices? Should we not blush to discourage our own industry and ingenuity; by purchasing foreign superfluities and adopting fantastic fashions, which are, at best, ill suited to our stage of Society?

Throughout his life Washington repeatedly embraced the principles of balance, and it would seem he thought the ladies of America were the best individuals to show the nation how to find balance in their manners and their homes. Within eight months Washington would rise to the presidency and need the aid of everyone—and especially women—to help him steer this infant nation down the right path, presumably away from “foreign superfluities” and “fantastic fashions” and toward republican simplicity.[24]

If Washington thought it would be easy to define republican simplicity as president, he would discover within days of arriving in New York City for his inauguration the inherent challenges in modeling such an ambiguous concept. This would prove especially difficult when he and Martha assumed the management of the first presidential household, a physical embodiment of the executive branch. The Washingtons may have wanted to encourage their countrywomen to furnish their homes with (and display on their bodies) American products that represented a national ingenuity and taste—and also spur on manufacturing and commerce—but in those early days of the federal government, the couple was unable to make that commitment. In 1783 buying French goods had helped Washington symbolically break with Great Britain, and six years later it would help him prove that the reconstituted United States was ready to be a player in the Atlantic world. He quickly realized that to secure his (and his country’s) place on the international stage, he would first have to demonstrate that he was an homme du monde, and he recognized that American manufactures were not quite ready for this task. So, with the help of America’s diplomatic families, the Washingtons would learn how to gain power and prestige by following the rules of civility and blending polite sociability with American politics. It is undoubtedly this recognition that led the Washingtons to buy the cômte de Moustier’s furnishings and chart a new path for republican simplicity, one that found inspiration in—but was never a slavish imitation of—French manners and materials.[25]

The story of the French furniture suite thus picks up again on the eve of Washington’s inauguration on April 30, 1789. In the frenzied days prior to the president-elect’s arrival in New York (by himself, as Martha remained in Mount Vernon for an additional two weeks to ready their household for the transition), Congress rented a house for the president at 3 Cherry Street and commissioned two local businessmen, Samuel Osgood and William Duer, to furnish the dwelling, top to bottom, in eight days (fig. 17). According to Osgood’s niece, Sarah Robinson, the gentlemen quickly recognized the monumental scope of this commission, so they “pitched on their wives” for help as the ladies were “likely to do it better.” Catherine Alexander Duer and Maria Franklin Osgood, evidently seasoned shoppers, “spared no pains nor expense” and acquired for every room the “best of furniture” available on short notice. Indeed, the ladies knew which craftsmen, merchants, and shopkeepers had ready-made furniture on hand and could supply such a substantial order. New York cabinetmaker Thomas Burling alone provided 125 pieces of furniture, from tables and sideboards to wash stands, beds, and seventy-three chairs. In Sarah’s estimation, the completed house did “honors” to her aunt and Catherine Duer. Shortly after being furnished, the house was being described as the “palace.”[26]

Despite the ladies’ every effort, opinions varied on whether or not they had succeeded in creating a home fit for the leader of the new nation. Martha Washington observed that the house was “a very good one and is handsomely furnished all new for the General;” but the French ambassador, the cômte de Moustier, used the word chétive to describe it, and this has been translated as both “humble” and “squalid.” To visitors like Moustier—seasoned diplomats and foreign dignitaries with an appreciation for the importance of image in the world of international politics—the house did not measure up. Later inventories of the presidential furnishings, coupled with a surviving example of a Burling chair with a Washington provenance (fig. 18), suggest that the ladies purchased items in a provincial, less fashionable style. To Moustier, coming from Paris where furniture styles changed on average every six years and a sophisticated neoclassicism was all the rage, the house at 3 Cherry Street must have seemed inelegant indeed. Based on Washington’s own reaction to his accommodations, the president likely felt the same way. While the couple wanted to promote American manufactures, they decided soon after settling into their new house—which they called the President’s House—that it would not be prudent to avoid all the fripperies and fantastic fashions of Europe.[27]

This recognition that the President’s House needed more elegant furnishings was undoubtedly informed by the social events that the Washingtons hosted from the earliest days of the presidency. Prior to his inauguration, George had determined that he and Martha would interact carefully with the public in such a way as to avoid showing preference to any single private citizen. Once they arrived in New York, however, they quickly discovered that some form of structure was essential to manage the numerous visitors who sought them out on both official and unofficial business at all hours of the day. As a result, George enacted a set of protocols designed to construct a social environment for the leaders of the new country. The solution was a combination of formal and informal events, called “levees” and “Drawing Rooms,” hosted respectively by the president and the first lady. On Tuesday afternoons between 3:00 and 4:00, upon the close of Congress, Washington held his levee, and on Friday evenings between 7:00 and 10:00, Martha hosted her reception in the drawing room. Additionally, on Thursday evenings they jointly hosted state dinners for members of the president’s cabinet and Congress, foreign diplomats, and their wives. All visitors, as long as they wore formal attire, were welcome at these events.

Abigail Adams wrote that Martha Washington’s drawing rooms were “usually very full of the well born and well bred. Sometimes it is as full as her Brittanick Majesties Room, and with quite as handsome ladies, and as polite courtier.” From the very beginning of George Washington’s administration, he and Martha turned to the European patterns of polite sociability to cope with the crowds and to bring dignity to their new roles. Other leading families immediately joined them in opening their drawing rooms on different nights of the week, and an official salon culture—just as in Paris and London—was born. First in New York, and then in Philadelphia once the capital was relocated, genteel Americans perfected the art of worldly hospitality. Over tea, dinner, and rounds of cards, they discussed literature and the theater, horticulture and politics, all the while performing their version of sociability. Historians in the nineteenth century would dub this social and political whirl the Washingtons’ “republican court,” a nice turn of phrase that suggests they could at once blend republican principles with the aristocratic aura of nobility.[28]

Washington’s first steps in ameliorating the look and feel of the President’s House came just two weeks after Martha joined him in New York and took charge of housekeeping. As frequent guests in the homes of leading families in Philadelphia and New York, the Washingtons were already well aware how the strategic placement of decorative objects in the French style could transform a room from pedestrian to prominent. They likely observed in these same houses that a new taste for the classical world was spreading, advocated by such designers as Thomas Sheraton, who advised his readers that anyone wanting a drawing room to “admit of the highest taste and elegance” would naturally turn to the neoclassical style. Once again, Washington relied on his instincts and past practices: he reached out to friends to help him buy more fashionable French and neoclassical pieces to supplement the furnishings provided by Congress. One can only assume that the president and the first lady believed they could remedy the situation with the addition of a few decorative accents in their public rooms.[29]

On June 8, 1789, secretary Tobias Lear wrote to Clement Biddle in Philadelphia on Washington’s behalf:

The President is desireous of getting a sett of those waiters, salvers, or whatever they are called, which are set in the middle of a dining table to ornament it—and to occupy the place which must otherwise be filled with dishes of meat, which are seldom or never touched. Mr. Morris & Mr. Bingham have them, and the French & Spanish Ministers here, but I know of no one else who has—I am informed that they are most likely to be got at French Stores as they are made in France;—we can find none in this place, and the Presid.t will thank you to enquire if a sett can be procured in Philada. And if it can, to procure it for him.

One wonders if Washington persuaded himself he needed a plateau de dessert after dining at the French minister’s residence, which he had done just a few weeks previously on May 14. According to the Gazette of the United States, that evening had been “uncommonly elegant, in respect both to the company and the plan of the entertainment;” another eyewitness reported how “three rooms were filled [for dancing], and the fourth most elegantly set offas a place for refreshment.” It could very well have been on these tables that Washington spied the silver and porcelain ornaments and decided they could provide that all important touch of l’art de vivre.[30]

Unfortunately, no plateau matching Lear’s description was to be found in Philadelphia, so the president wrote next to Gouverneur Morris, then in Paris and always a willing proxy shopper. Washington commissioned Morris to find “mirrors for a table, with neat and fashionable but not expensive ornaments for them—such as will do credit to your taste,” and to refer to the plateau on Robert and Mary Morris’s table as a model. After describing the general parameters of his request and giving Morris leeway to shop in either London or Paris—wherever he could get the best terms—Washington stressed yet again the importance of financial restraint. “One idea however I must impress you with,” he confided, “and that is in whole or part to avoid extravagance. For extravagance would not comport with my own inclination, nor with the example which ought to be set.”[31]

Gratified to render his friend this service, Morris promptly filled the order for the plateau and figurines (fig. 19). With his knowledge of the fickleness of French fashions, Morris recognized that the style of these pieces was essential: if he sent less expensive, but what he called a more au courant design, the president’s table would resemble “the style of a petite Maitresse of this city,” which was most assuredly not the style they would want. If, on the other hand, the Washingtons were willing to invest a reasonable amount of money, they could be assured that their ornaments would be fashionable (as well as valuable) for years to come and, perhaps most importantly, they would exude a “noble Simplicity.” Morris could not refrain from reminding the president that at this point in the nation’s development it was essential “to fix the Taste of our Country properly,” and that his example alone would “go very far in that Respect.” Morris thus explained:

It is therefore my Wish that every Thing about you should be substantially good and majestically plain; made to endure. Nothing is so extravagant in the Event as those Buildings and Carriages and Furnitures and Dresses and Ornaments which want continual Renovation. Where a Taste of this kind prevails, each Generation has to provide for itself whereas in the other there is a vast Accumulation of real Wealth in the Space of half a Century.

Morris selected a plateau in the neoclassical style together with two vases and fifteen biscuit-porcelain figurines representing characters from classical mythology that would, he believed, allow the Washingtons to signal their politeness without triggering a fear of luxury. These visual allusions to the classical world—columns, swags, chitons, the pure white of marble, and Venus, the mother of Rome herself—referenced the political ideals of ancient Greece and Rome and reminded viewers that America was founded on these same principles (figs. 20-22). Through this commission, Morris instructed the Washingtons how to use French fashions to signal their confidence that America could be—indeed would be—the next great civilization.[32]

Relating this whole exchange on the plateau is instructive in illustrating how the Washingtons (with the help of their proxy friends) were consciously and conscientiously crafting a persona for the presidential family through material choices. They understood the political and personal risks the president was taking with each purchase, and Washington communicated as much to his acquaintance, British historian Catherine Macaulay Graham. “In our progress toward political happiness my station is new; and I may use the expression, I walk on untrodden ground,” he began. “There is scarcely any action, whose moves may not be subject to a double interpretation. There is scarcely any part of my conduct which may not hereafter be drawn into precedent.” Washington wrote this letter in January 1790, the same month when Morris completed the commission in Paris and Washington himself was contemplating additional changes to the President’s House. Washington was keenly aware that he would be criticized for being aristocratic if he surrounded himself with expensive (but equally beautiful, convenient, and elegant) foreign imports on the one hand, and uncivilized if he did not invest in the tools and activities of polite sociability on the other. As a result, he attempted to steer a narrow path between the two extremes. Judicious purchases of French furnishings would, he hoped, show him to be a man not only of republican virtue but also of cosmopolitan taste.[33]

Desirous of finding that middle ground between aristocratic pretension and republican austerity, the Washingtons might have contented themselves with adding those few, select table decorations Morris shipped to the President’s House and considered the business done. However, an unlooked-for opportunity to buy French furnishings en suite arose when the French ambassador, Élénor-Francois Élie, Comte de Moustier, was recalled to Paris in October 1789 and chose to sell his household goods instead of shipping them home. This was the same minister who had fêted Washington in grand style the previous May and had worked hard to cultivate a relationship with the new president since his arrival in January 1788. As the Cherry Street house selected by Congress proved rather inconvenient for the Washingtons in terms of size and location, the first couple opted to take over the lease of 39 Broadway from the French legation (fig. 23). This house was newer, larger, and better situated to the work of Congress in Federal Hall in the lower Broadway; and, most importantly, it was decorated in the French taste. Using £665 of their personal money, the Washingtons purchased the ambassador’s furnishings and were thereby able to infuse their public rooms with the lightness and sophistication of French neoclassicism without the added expense and delays associated with proxy shopping abroad (fig. 24).[34]

Among the many benefits to the Washingtons in securing such a large collection of furnishings was that these items had been pre-selected and assembled by fashionable Parisians who understood worldly hospitality. While the practice may seem strange to modern sensibilities, buying and selling second-hand luxury and semi-luxury goods was quite common in Paris. It offered aristocrats an outlet for the items they no longer needed (because of rapidly changing fashions or excessive debts), and it made high-end fashions available to individuals who could otherwise not afford them new. Such furnishings were desirable not only because they were often of excellent quality and design (and had a discounted price), but also because they gave purchasers a connection to the original owners. By moving into 39 Broadway and stepping into the furnished spaces orchestrated by Moustier and his traveling companion, his sister-in-law Anne-Flore Millet, marquise de Bréhan, the Washingtons were taking advantage of Moustier and Bréhan’s collective skills setting up houses intended for the work of diplomacy.[35]

Moustier was an experienced ambassador by the time of his arrival in the United States, having worked his way up through the diplomatic service with postings to Lisbon, London, Naples, and Coblenz, and he certainly knew the role polite sociability and hospitality could play in forging strong diplomatic relations between the two countries. Indeed, this awareness may be the reason the widowed minister invited his sister-in-law to accompany him and serve as his hostess in this prominent posting. Thomas Jefferson (then still in Paris) certainly believed that together the pair were imminently suited for the new position and would serve as welcome models of European politeness. In his letters of introduction to both Madison and Jay, Jefferson sang Moustier and Bréhan’s praises, declaring his countrymen would find in the new minister a man “simple in his manners, and a declared enemy to ostentation and luxury.” Moreover, he continued, they could not find a “better woman, more amiable, more modest, more simple in her manners, dress, and way of thinking” than madame de Bréhan (fig. 25). Jefferson in fact saw such promise in the pair that his parting words to the minister upon his departure for New York were “Mr. Jefferson . . . considers the Count de Moustier as forming, with himself, the two end links of that chain which holds the two nations together;” and he cautioned Bréhan that although the “imitation of European manners, which you will find in our town, will, I fear, be little pleasing,” he hoped she would continue to practice her own, “which will furnish them a model of what is perfect.” Arbiters of taste, manners, and (Jefferson hoped as well) French policy, Moustier and Bréhan came with all the essential housewares they needed to entertain on a grand scale and share their culture with the new nation (fig. 26).[36]

One can assume that when the Washingtons moved into 39 Broadway on February 23, 1790, they anticipated that the elegance and comfort of their French furnishings would lend prestige to their weekly social and political gatherings. They could replace the less fashionable items purchased by Congress for their public rooms and use instead the coordinated suite of drawing room seating furniture with matching window treatments, fire screens, mahogany buffets, looking glasses, and lamps. They also now had a desk, dressing table, bidet, and clothes presses for the private rooms, and a dinner service of white and gold Sèvres porcelain for their public events (a welcome upgrade from the everyday Queen’s Ware they had been using) (figs. 27-30). Visually, the new pieces spoke a different stylistic language than the ones made locally, as can be seen by comparing them with furniture made in Thomas Burling’s workshop. Burling was a well-respected cabinetmaker in New York when he received this important commission for the President’s House, and his surviving furniture indicates he was aware of the latest taste for neoclassicism. Like so many of his contemporaries, Burling began to embrace the so-called Federal style during the 1780s, but it is impossible to determine if the Cherry Street furnishings were in that mode or were more indicative of New York furniture made just prior to or during the Revolutionary War (fig. 31). It is likely, however, that the chairs he provided Congress represented an intermediate step between the two styles and could thus have been deemed less fashionable.[37]

Characterized as “plain” or “carved” in period inventories, Burling’s mahogany chairs derived inspiration from British seating. Although surviving chairs from the Duer-Osgood decorating campaign can no longer be attributed reliably to Burling, an armchair reputedly purchased by Washington from Burling in 1790 provides some suggestion of what the other chairs might have looked like (fig. 18). This shield-back chair, with a feather-motif splat design popularized by the British firm Gillow and Company, has reeded arm supports and reeded legs that terminate in spade feet. It is decidedly British in its aesthetic and contrasts greatly with the painted French chairs (see fig. 1). The former appears heavy and at times awkward in its execution with thick legs and feet, whereas the latter’s molded stretchers, tapered, straight, and fluted legs, with neatly carved rosettes set in the corner blocks, lend it a more refined and delicate aspect. These are certainly unequal interpretations of the neoclassical—one provincial, the other cosmopolitan—and that distinction could have highlighted their juxtaposition in the same house. The visual comparison of the chairs shows how the Washingtons aligned themselves more than ever before with the materials and manners of French sociability. With the purchase of the Moustier suite they silently acknowledged that the products of France offered a roadmap to civility and, thereby, a path to a strong and enlightened federal government.[38]

When the government relocated to Philadelphia nine months later, the entire contents of 39 Broadway were carefully packed up, shipped south, and reinstalled in 190 High Street, the home Congress rented from Robert and Mary Morris to serve as the third President’s House (fig. 32). With secretary Tobias Lear’s able assistance (and likely also Mary Morris’s since Washington reminded Lear to seek her advice, too), each and every piece of presidential furniture was strategically placed to create, once again, that sense of distinction in the public rooms. George Washington hosted his levees now in the dining room, located on the ground floor, while Martha held her formal drawing rooms in the large, second-floor parlor, officially known as the “Green Drawing Room” because of the coordinating upholstery in their beautiful French suite (figs. 33, 34). On the whole, it seems likely the new drawing room was arranged much like it had been established by Moustier and Bréhan in New York, although the Washingtons did make a few changes. They installed a new carpet, which had been ordered from London and intended for 39 Broadway but had not arrived before the relocation; acquired additional mirrors and lighting devices; and enlarged the suite of chairs from eighteen to twenty-four. After settling into a routine, one presumes the Washingtons recognized a need for additional side chairs, and George paid French émigré upholsterer Georges Bertault for “six chairs, 2 stools G[reen] Drwg” in January 1793.[39]

Knowing the precedents for furnishing salons in Paris, a picture of the Washingtons’ famed state drawing room increasingly comes into focus (fig. 35). The painted walls and woodwork provided an elegant architectural backdrop for the furnishings. Although the exact nature of the woodwork cannot be determined, it is possible the walls were finished with pedestal-high wainscoting and a fretwork cornice, and that the chimney wall and door pediments were set off with a more elaborate pulvinated frieze of banded oak foliage (fig. 36). The paint could have been cream-colored, as was then the fashion, giving the room a light, airy aspect. The inventory Washington completed in 1797 indicates the walls were adorned with a combination of gilt mirrors, framed pictures, and lighting devices. The two rectangular looking glasses purchased from Moustier could have hung on the northern, eastern, or western walls, but it is more likely they were displayed as a pair, bracketing either the doors or the mantle and arranged in such a way as to maximize the sense of light and space (fig. 37). Complementing these large looking glasses were four oval mirrors with brackets (figs. 38, 39). Also in the neoclassical style, these pieces were made in Philadelphia by carver and gilder James Reynolds. Hanging nearby were two matching, urn-shaped patent lamps with delicately engraved floral garlands that echoed details on the mirrors (fig. 40). Washington listed two landscape views as part of the wall furnishings, The Great Falls of the Potomac and The Passage of the Potomac, both by George Beck (figs. 41, 42). The final piece of fixed decoration was a lustre of eight lights, with carved and gilt flowers and tassels, suspended from the center of the ceiling.[40]