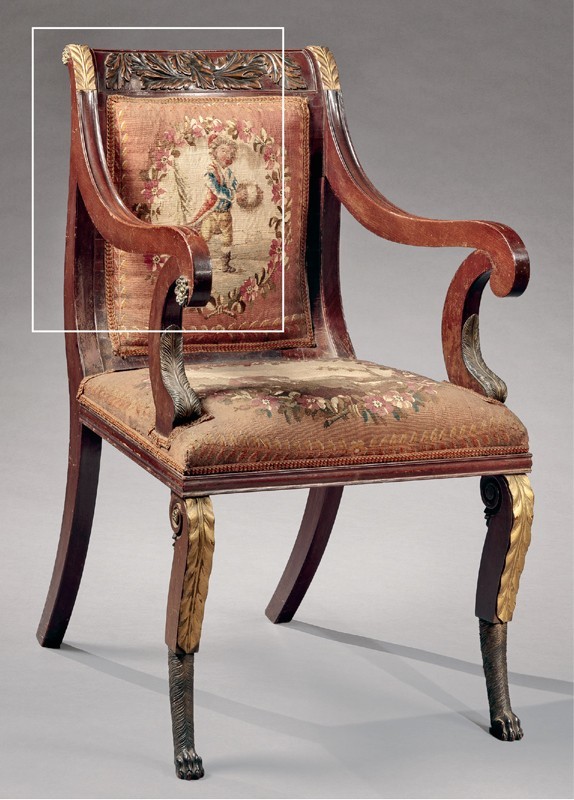

John Banks, armchair, New York City, 1819. Mahogany with ash and white pine. H. 37 3/4", W. 21 1/2", D. 27 3/4". (Courtesy, Bernard and S. Dean Levy, Inc.; photo, Richard Goodbody.) The letter designations provided for some of the seating illustrated here are derived from accession numbers assigned by the New-York Historical Society. This armchair is “H”.

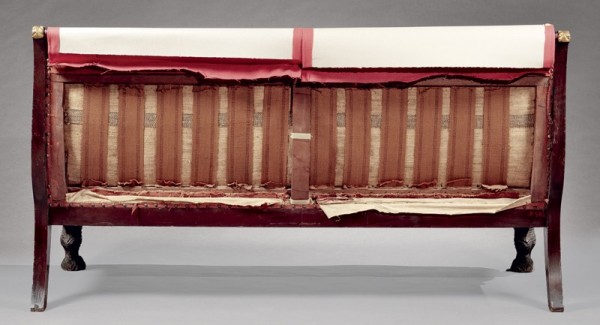

John Banks, sofa, New York City, 1819. Mahogany with cherry, ash, and white pine. H. 38 1/2", W. 72", D. 27". (Courtesy, Bernard and S. Dean Levy, Inc.; photo, Richard Goodbody.)

John Banks, armchair, New York City, 1819. Mahogany with cherry, ash, maple, and white pine. H. 37 3/4", W. 21 1/2", D. 27 3/4".(Courtesy, Bernard and S. Dean Levy, Inc.; photo, Richard Goodbody.) This is armchair “K”.

Frontispiece to Esther Singleton, The Furniture of Our Forefathers, pt. 4, (New York: Doubleday, Page, August 1901).

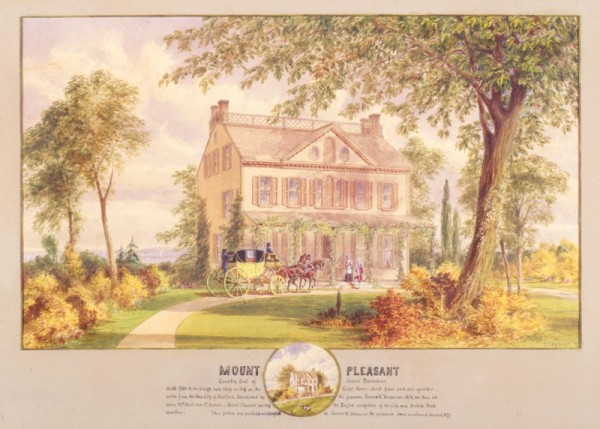

Abram Hosier, “Mount Pleasant,” New York City, ca. 1874. Watercolor, gouache, and graphite on paper. 30" x 40". (Courtesy, New-York Historical Society, gift of the Beekman Family Association.)

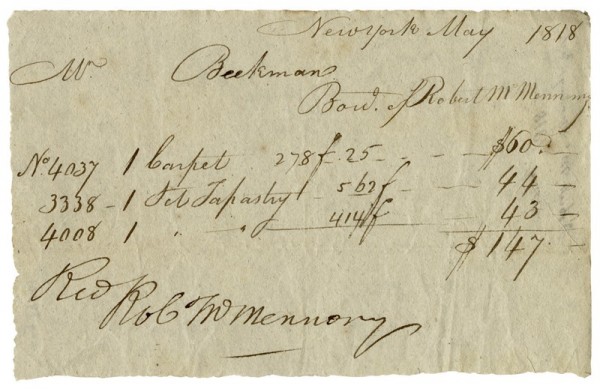

Robert McMennomy to James Beekman, invoice for tapestry sets, May 1818. (Courtesy, New-York Historical Society.)

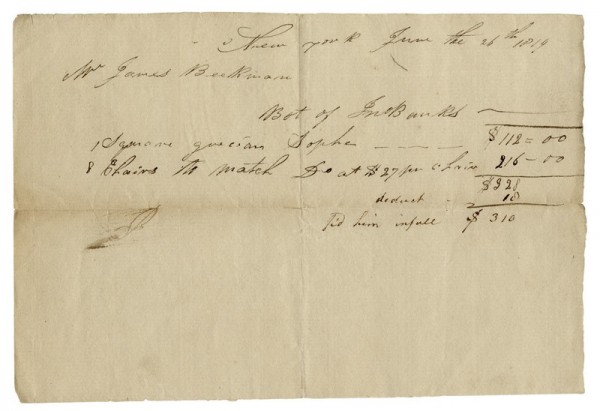

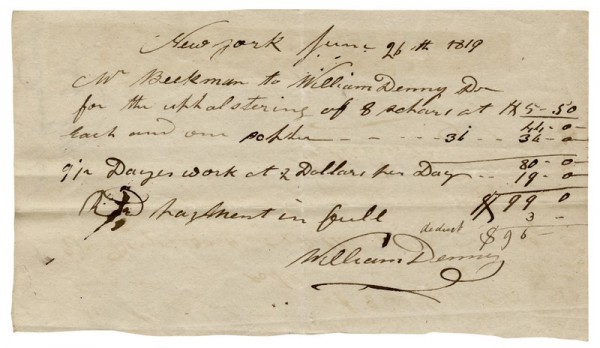

John Banks to James Beekman, invoice for a set of eight armchairs and one sofa, June 26, 1819. (Courtesy, New-York Historical Society.)

Thomas Seymour, Grecian card table (one of a pair), Boston, 1816. Mahogany. H. 30 1/8", W. 36 1/4", D. 18". (Courtesy, Adams National Historic Site; photo, David Bohl.)

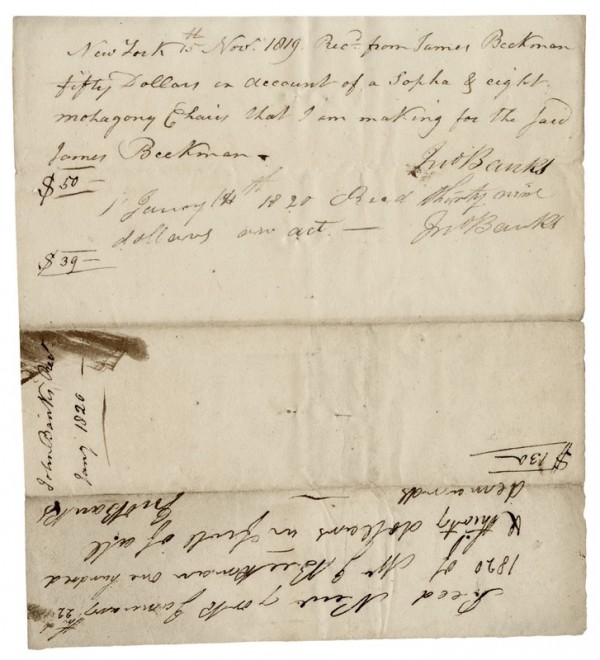

John Banks to James Beekman, accounting for a set of eight armchairs and one sofa, November 15, 1819. (Courtesy, New-York Historical Society.)

John Banks, tall case clock, New York City, 1820–1826. Mahogany, light and dark wood inlays and stringing with tulip poplar. H. 96", W. 21 1/2", D. 11 1/4". (Courtesy, Sotheby’s.)

John Banks, work table, New York City, ca. 1824. Mahogany, rosewood, and walnut with tulip poplar and white pine. H. 31 1/2", W. 24 3/4", D. 20 3/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; photo, Laszlo Bodo.)

John Banks , serving table, New York City, 1820–1826. Mahogany with tulip poplar and white pine. H. 33 1/4", W. 36 1/4", D. 18". (Courtesy, Locust Lawn.)

John Banks, dining table section (one of a pair), New York City, 1820–1826. Mahogany. H. 28 1/4", W. 46", D. 21". (Courtesy, Decorative Arts Photographic Collection, Winterthur Museum.)

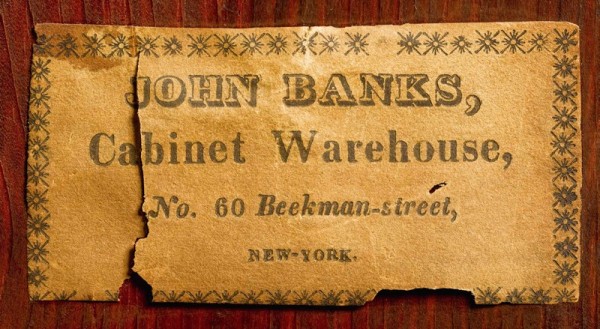

Printed label of John Banks on the tall case clock illustrated in fig. 10.

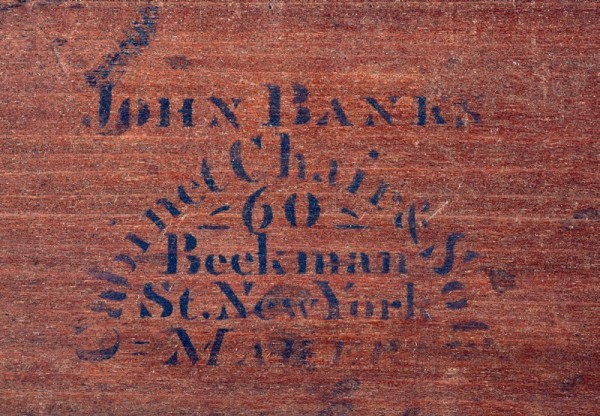

Stenciled label of John Banks on the work table illustrated in fig. 11.

Underside of armchair “P” showing medial brace and corner blocks.

Underside of armchair “F” showing no medial brace and one remaining corner block.

Leg detail of medial armchair “P”.

Leg detail of no-medial armchair “F”.

Crest rail of medial armchair “K”.

Crest rail of no-medial armchair “A”.

Backs of medial and no-medial armchairs “I” (left) and “D” (right).

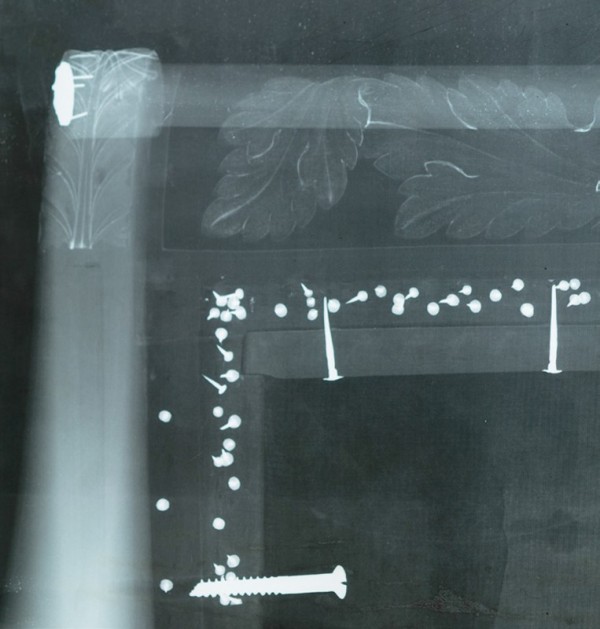

X-ray showing the back construction of no-medial armchair “A”.

X-ray showing the back construction of medial armchair “P”.

Charles Honoré Lannuier (1779–1819), pier table, New York City, 1815–1819. Rosewood with white pine, tulip poplar, and ash. H. 37", W. 54", D. 22 1/2". (Courtesy, Historic Deerfield, Inc.; photo, Amanda Merullo.)

Tavern sign for the Williams Inn of Centerbrook, Connecticut, 1803. Pine and maple. 54 3/4" x 35 1/8". (Courtesy, Connecticut Historical Society.)

X-ray of a broken arm support showing an internal dowel on no-medial armchair “F”.

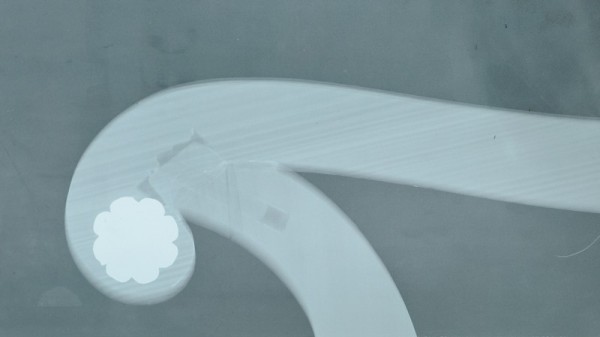

X-ray showing the long original dowel in an arm support on medial armchair “P”.

Detail showing a dowel with tenon notch. (Photo, Philip Zimmerman.)

Detail of the red sofa showing a leg and arm support.

Comparative detail showing the leaf-carving on the front legs of no-medial armchair “F” (left) and medial armchair “P” (right).

Comparative detail showing the arms of a medial (left) armchair and a no-medial (right) armchair.

Comparative detail showing the arms of the green (left) and red (right) sofas.

Detail of the arm support of the red sofa.

Detail showing the back of the arm support of the red sofa.

Detail showing the sea monster tail inside the rosette of the arm support base of the red sofa.

Detail showing the arm support of the green sofa.

Green tapestry back and seat from medial armchair “K”.

Red tapestry back of armchair “O” with a composition similar to that of armchair “L”, illustrated in fig. 40.

Green tapestry back of armchair “L” with a composition similar to that of armchair “O” illustrated in fig. 39.

Detail of the green sofa showing the wide veneer border between the upholstered panel and the rear stile.

Detail of the red sofa showing the narrow veneer border between the upholstered panel and the rear stile.

Sofa, New York City, 1805–1810. Mahogany and light and dark wood inlays and stringing with beech, ash, and other unidentified woods. H. 39", W. 73 1/2", D. 26". (Courtesy, New‑York Historical Society; photo, Glenn Castellano.)

Sofa, New York City, 1805–1810. Mahogany and light and dark wood inlays and stringing with ash, oak, cherry, tulip poplar, and white pine. H. 40", W. 73 1/2", D. 25 1/2". (Courtesy, New-York Historical Society; photo, Glenn Castellano.)

Detail showing patched-in tapestry inside the arm of the sofa illustrated in fig. 43.

Detail showing tapes at the arm supports of a chair from each group (armchairs “D” [left] and “L” [right]).

Detail of armchair “A” showing deep red, modern tapes.

Detail showing the foundation upholstery of medial armchair “P”.

Detail showing the arm support mortise and upholstery blocks of medial armchair “J”. (Photo, Philip Zimmerman.)

Detail showing the arm support mortise and grass seat roll on no-medial armchair “D”.

William Denny to James Beekman, invoice dated June 26, 1819. (Courtesy, New-York Historical Society.)

Unidentified artist, portrait of Cornelia Augusta Beekman, ca. 1897, oil on canvas. 48" x 31 1/2" (sight). (Privately owned; photo courtesy New-York Historical Society.)

Armchair “F”, with highlighted detail showing the area depicted in the portrait illustrated in fig. 52.

View of the red sofa showing the open back.

Detail of the exposed back upholstery and tacks of armchair “F” with original trim (fig. 53). The loosened tacks were kept in place.

Detail of the exposed upholstery and multiple tack holes in the back of armchair “A” with replaced trim.

Medial armchair “G” with green upholstery.

No-medial armchair “A” with red upholstery.

The historical record for early American furniture seldom releases its secrets about who made a particular piece of furniture, when and where it was made, for whom, or under what circumstances. Some objects survive with oral traditions of descent in particular families, but often those reconstructed histories are more aspirational than factual. Similarly, long-time attributions to makers may signal over-eagerness or other evidence of wishful thinking. Early written records of such object histories or provenances do much to eliminate speculation. Such is the case with two sets totaling sixteen armchairs and two sofas, all upholstered in rare French woven tapestry (figs. 1-3).

Furniture historian Esther Singleton first published this seating in The Furniture of Our Forefathers (1901), her serialized history of American furniture regions and styles, as belonging to the Beekmans, a leading family of New York and direct descendants of Wilhelmus Beekman (1623–1707), who immigrated to New York in 1647 with Peter Stuyvesant and others. Singleton included the chairs and sofas among pre-1776 “Dutch and English -Periods,” apparently influenced by caption author Russell Sturgis (1836–1909), an architect, art critic, and founder of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. He dated one sofa (and by implication the other sofa and all of the armchairs) circa 1760 (fig. 4). Sturgis’s sense of furniture history may have been influenced by the prominence of James Beekman (1732–1807), a great-grandson of Wilhelmus but better known as the builder of Mount Pleasant, a grand country seat constructed in 1763–1764 and overlooking the East River near what is now First Avenue and 51st Street (fig. 5). The house was demolished in 1874. Sturgis, born in Maryland but educated in New York City where he subsequently practiced architecture, may have seen the house and furnishings, but regardless, Mount Pleasant was known through drawings, photographs, interior paneling, and the carved parlor chimney breast given to the New-York Historical Society in 1874. Sturgis went on to identify the extraordinary upholstery as “French tapestry, Gobelins or Beauvais, of the same or a somewhat later epoch.”[1]

A remarkable family reminiscence recorded on December 30, 1876, was more accurate. In it, Mary Beekman de Peyster (1800–1885), a great niece of James Beekman, recalled:

The gobelin tapestry chairs and sofas were bought by the same uncle James Beekman–from a French nobleman who had fled to the West India Island about the year 1818 or 1820 the chair and sofa frames were made here in New York.

Concerning the gobelin tapestry chairs and sofas, I was told by Catharine Moulton (Catharine Hill) – who lived for many years as housekeeper with my uncle James Beekman at the mount [i.e., Mount Pleasant] – from about 1817 till his death in 1837.) a few months before her death in 1875 that she remembered that these chairs and sofas were bought by my uncle – they were not inherited by him she said, but he bought the tapestry, and had the frames made in New York – She remembered that they were bought while she lived with him. This confirms Mrs. de Peyster’s recollection and establishes the history of the gobelins – which have therefore been in our possession only about 55 years.

“Uncle James” was Beekman’s son and namesake, James Jr. (1758–1837). This younger James was correctly identified as the original owner when the Beekman armchairs and sofas were exhibited at the New-York Historical Society throughout most of the twentieth century, but the furniture maker’s identity proved elusive. A modest exhibition pamphlet published by the society in 1976 dated the seating circa 1820 and attributed it to the “workshop of Duncan Phyfe,” a generalized form of identification that is sometimes understood to be code for confusion. Given the ambitiousness of the Beekman seating, its upholstery, and its esteemed provenance, furniture historians of the 1970s might have thought that the chairs and sofas should have been made by Duncan Phyfe, although this furniture does not sit comfortably among Phyfe’s known work. In 2001 furniture historian Elizabeth Bidwell Bates laid uncertainty to rest by discovering several Beekman invoices and accounts that address different aspects of the seating, including its manufacture by New York furniture maker John Banks (ca. 1789–1826).[2]

The earliest manuscript is a bill of sale describing James Beekman’s purchase of two “Set Tapastry” and a carpet from New York auctioneer Robert McMennomy (ca. 1769–1842) in May 1818 (fig. 6). As multiple newspaper notices beginning in 1801 attest, McMennomy regularly sold a variety of goods along the New York City waterfront. By 1805 he advertised selling “valuable property” specifically at “public vendue” (i.e., auction), and in 1817 he was listed among some thirty other New York City auctioneers as having paid duties on auction sales to the city in the previous year. Although newspapers often detailed auction offerings, no notice has yet been found that describes the precise circumstances of McMennomy’s tapestry sale to Beekman. It is possible that the tapestry sets were sold to him privately rather than at public auction.[3]

In light of the Beekman bills of sale, Mary de Peyster’s personal reminiscence assumes an interesting dimension. Historians of all kinds rightfully challenge the accuracy of such reminiscences—and historical memory in general. With the help of psychological studies, they point out regular reportings of factual misstatements, enhancements, and wish-fulfillments. From the perspective of furniture history, one need only consider the number of beds George Washington slept in or all of the furniture that supposedly came over on the Mayflower. But Mary de Peyster’s recollections are substantiated by independent and reliable historical evidence. Her Uncle James inherited Mount Pleasant in 1817, as she said, the year in which his mother and surviving parent died. The seating in question was in fact bought by her uncle and not inherited, as Sturgis erroneously assumed. And, inasmuch as the “gobelins”—that is, the tapestry coverings—were bought at an auction or private sale, even the fleeing French nobleman story may contain an element of truth.

De Peyster did not mention that all of the Beekman seating comprised two separate sets of eight armchairs and one sofa each, although she surely must have noticed the differences. Casual inspection of the sixteen armchairs readily divides them into two groups of eight. Eight have upholstery covers with green backgrounds and eight have red. There is one green sofa and one red one. Details of construction and carving also divide the sixteen chairs into two groups of eight, but those groupings are not the same. Six of one construction type have green covers and the remaining two have red. The other eight chairs complement this six-and-two distribution of covers on frames. The two sofas exhibit less obvious carving and construction differences from one another. More detailed analysis below links construction of one sofa to one set of eight chairs and the other to the second set.

The McMennomy tapestry bill listing two sets leaves open to question what designated a set in the early nineteenth century. No single definition prevailed, but various contemporary listings often enumerated eight chairs and one sofa. For example, in 1811 the auction company C. and H. F. -Barrell in Boston offered for sale “1 Sopha, and 8 Chairs, Gobelin Tapestry.” Another set of eight chairs accompanied three sofas “of Goblin Tapestry in perfect order” in an 1801 offering by Arden and Close of New York City as part of “a variety of superb and costly household Furniture.” Still other references remind the modern researcher that the number of chairs that constituted a set was not constant. Nonetheless, the evidence suggests that in the United States after 1800, sets of eight were both common and reasonable alternatives to sets of six, which seem to have prevailed (but with exceptions) in the eighteenth century.[4]

John Banks’s two furniture bills, which support the concept of a set representing eight chairs and one sofa, require some explanation. The first one, dated June 26, 1819, specifies a “Square grecian Sopha” and eight matching chairs (fig. 7). Although the seating forms are straightforward, use of the term “Grecian” is not. This early reference is not the first in New York usage. Upholsterer William W. Galatian, for example, offered “a handsome Grecian Couch” among wallpapers, upholstery textiles, and other items in an 1814 advertisement. Several different tradesmen listed Grecian sofas and couches in 1817 advertisements. And the next year, the auction firm of Franklin and Minturn mentioned a “Grecian sofa and chairs to match” among “the furniture of a parlour and bed room” they offered for sale.[5]

What, precisely, did the term Grecian communicate to those living in the early nineteenth century? As is so often the case in furniture history, exact definitions are elusive. Typically, either the historical term survived or the piece of furniture in question did, but not the two linked together, leaving scholarly application of one to the other open to various possibilities. The Beekman chairs and invoices are a rare exception. Another rare instance is Bostonian Peter Chardon Brooks’s purchase of “a p[ai]r of Grecian card-tables” from Thomas Seymour in December 1816 (fig. 8). Comparison of the Beekman chairs to the Brooks card tables yields little to define what “Grecian” might have signaled. Other written references to Grecian, lacking direct ties to the individual pieces of furniture that could illuminate the term to modern viewers, contribute little. For example, the 1810 New-York Revised Prices for Manufacturing Cabinet and Chair Work lists a “Grecian Sofa” but offers no image or further description. The 1815 Additional Prices edition includes a telling phrase, namely “the foot to form a Lion’s leg and paw at bottom.” Such reference to an animal paw foot was probably a meaningful feature in American usage at the time. “Lion’s paws” accompanies the term Grecian in an entry for stools in an 1808 London price book, but as in America, English usage was never precise. In other contexts, Grecian denoted certain “antique” features, such as in-curved front legs (popularly called saber legs today) and “Grecian cross” chair-backs or front stretchers shaped as two semicircles, one above the other and joined (lapped) where they touch. English designer Thomas Sheraton, writing in The Cabinet Dictionary of 1803, captured the vagueness associated with the term by explaining that it signified anything in the taste of the Greeks.[6]

To return to the Banks payment records, Beekman received a deduction of $18 from the total of $328 for the one set listed on the 1819 invoice. No explanation accompanies this deduction, but it probably rewarded prompt payment. A single Beekman receipt bearing three separate payments beginning with $100 on June 26, 1819 (the invoice date), shows that purchase of this first set was completed on August 3, 1819. Documentation for the second transaction is indirect. On November 15, 1819, some five months after billing for the first set, Banks acknowledged receipt of “fifty Dollars on account of a Sopha & eight mohagony Chairs that I am making for the said Beekman,” clearly designating a second set (fig. 9). On December 13, Banks issued a bill of exchange in the amount of $111.75 that he owed to a third party, namely J. R. Hardenbergh, a gunpowder manufacturer. Those funds, due in sixty days, were to be charged to James Beekman’s account, in essence representing a payment from Beekman to Banks. The following January, Banks received two payments of $39 and $130, bringing the grand total for the second set to $330.75, or slightly more than the cost of the first set. The last reference to Banks in the Beekman manuscripts is a receipt dated June 17, 1820, for $9.00 “in full of all Demands.”[7]

Furniture maker John Banks is enigmatic. He is first recorded as a cabinetmaker in the 1818–1819 New York City directory, working at 66 1/2 Beekman Street. Henry Banks, cabinetmaker, occupied 66 Beekman Street that year. Two years later, John and Henry were both listed at 60 Beekman Street. Henry died on December 31, 1821, “in the 62d year of his age. His friends and acquaintances are respectfully invited to attend his funeral tomorrow afternoon at 3 o’clock, from his late residence No. 60 Beekman street.” Given Henry’s age, occupation, and residence, he was likely John’s father, or perhaps an uncle. Regrettably, no information about John’s birth, parentage, or upbringing has come to light. The 1819 New York City Jury Census, which recorded adult males eligible for jury duty, identified their occupation and age. John’s age was given as thirty in 1819, indicating a date of birth about 1789. Curiously, no New York City resident of that name is listed in the 1820 U.S. Census, although Henry’s name is. “John Banks, cabinetmaker,” disappears from repeated listings in New York City directories after a final address at 51 Beekman Street in the 1825–1826 edition. A court document dated February 2, 1827, directs that “Ann Banks the Mother of John Banks, late of the city of New York, Cabinet-maker, Deceased,” be given power of attorney for John, who died without leaving a will. No probate records, notably an estate inventory (which furniture historians find immensely valuable to fill out details of a furniture maker’s life), have yet been found. However, a death record conforming to the timing of the court decree states that John Banks, age thirty-three, born in Dublin, Ireland, died on December 24, 1826. It introduces a four-year discrepancy in John’s age.[8]

If these records were all that survived about John Banks, furniture historians would bemoan the paucity of information, note the uncertainty of his birth year, and move on—but there is more to his story. The New-York Evening Post, the same newspaper that published Henry Banks’s death notice in 1821, reported on August 18 of that year, “DIED Yesterday morning, in the 24th year of his age, Mr. John Banks, of a tedious illness, which he bore with a manly and christian fortitude, entire [sic] resigned to the will of his Maker.” The newspaper notice does not identify this John Banks by any trade that might have distinguished him from others of that name in New York City, but it follows another item published on May 5, 1821:

Elegant and Substantial Cabinet Furniture.

On Monday at 11 o’clock, at No. 62 Beekman street, the entire stock of fashionable Cabinet Furniture, of Mr. John Banks, consisting of 8 side-boards, 3 handsome pillar and claw card tables, large and small sets of dining do. [“ditto,” i.e., having pillar and claw bases] ladies work do. 2 bed chairs, bureaus, secretarys, mahogany high post bedsteads, maple field do. candle and wash stands, cradles, &c, &c.—will be sold without reserve for cash.

Robert McMennomy, Auctioneer.

Taken together, these references provide strong evidence that the young John Banks (this one born in 1797 according to his stated age of twenty-four when he died), an active and accomplished furniture maker working at 62 Beekman Street (the same address as listed in the 1820–1821 New York City directory), terminated his business because of a serious illness, which subsequently caused his death. Yet Banks’s name continued to be listed as a cabinetmaker on Beekman Street until his apparent death again in 1826. Resolving this dilemma with certainty requires further historical evidence, which is simply lacking. Early New York City records are notoriously less numerous than those for most other large American cities. Fires, British occupancy during the Revolutionary War, constant building and rebuilding in the rapidly growing city, and other forces all contributed to substantial gaps and losses. Until some confirming evidence comes to light, the court record of 1826 seems to be more plausible than the newspaper notice. Instead, that notice likely referred to another John Banks. New York City was home to several men of that name, including three listed in the 1830 U.S. Census. Newspapers noted the death of a Mr. John Banks, described only as “a native of England,” on July 17, 1818; in April 1819, Mrs. Elizabeth Banks, wife of another John Banks (unidentified, but not the furniture maker), died; John Banks, shoemaker, appears in the 1822–1823 city directory; combmaker John Banks is listed the next year; and “John Banks, cartman,” appears in the year following. Again, details are not rich enough to confirm how many different people these several listings represented.[9]

Four pieces of furniture bearing the printed label or stencil of John Banks are known. They include a profusely inlaid mahogany tall case clock, a gilt-stencil lyre-base work table of rosewood veneer and mahogany, a mahogany chamber table, and a pair of elliptic dining table ends known only by photographs (figs. 10-13). Banks’s printed label and stencil each give his address as 60 Beekman Street, where he first appears (with his father Henry) in the 1821–1822 city directory and where he remained for the next four years (figs. 14-15). No further evidence allows this labeled furniture to be dated more specifically, except the work table. It has the name “LAFAYETTE” worked into decoration on the top in honor of the marquis de Lafayette’s triumphal visit to America. That thirteen-month tour to all twenty-four states began in New York City with his celebratory landing at Castle Garden (now Castle Clinton in Battery Park), at the lower tip of Manhattan, on August 16, 1824. Otherwise, comparisons between and among these documented pieces of furniture contribute little to defining Banks’s shop production beyond demonstrating a broad range of forms, decoration, and practices. More important, nothing suggests why the wealthy and influential James Beekman might have chosen the young Banks to make two sets of seating furniture intended to be upholstered in exotic French tapestry. The commission, however, may have inspired Banks’s description of himself as “Cabinet Chair & Sofa Maker” on his stencil. The printed paper label, in contrast, advertises “John Banks / Cabinet Warehouse,” with the address.[10]

Banks’s “Cabinet Warehouse” at 60 Beekman Street was probably a first-floor room, visible from the street, where he stored and showed readymade furniture. Living quarters were upstairs. Before he and his father moved to that address from a few doors up the street, cabinetmaker John L. Everitt occupied that space. Beekman Street, which ran from south of New York City Hall (built 1802–1811) southeast to the East River, supported a small enclave of furniture makers living (and renting) in buildings numbered from 40 to 66, clustered near the middle of the street and mostly on one side. In 1819 James Poillon’s “Cabinet Warehouse” was at number 40, fancy chair painter William Brown was at number 50, and cabinetmaker Andre Froment occupied number 66. The proximity of all these furniture makers introduces the possibility that they cooperated with one another on work from time to time, but the historical record is simply not rich enough to document or detail such circumstances. Personal relationships, rather than proximity, might also have driven cooperative ventures, which could easily have established connections to other furniture enclaves in the city. Duncan Phyfe was at 168–172 Fulton Street a few blocks away, and Michael Allison was at 46–48 Vesey Street, another block or so farther. Many other furniture makers were scattered elsewhere. New York City and the furniture trade it supported were rapidly growing in scale and complexity in the opening decades of the nineteenth century.

Construction and Decoration of the Armchairs

The Beekman armchairs and sofas represent ambitious design and stylish-ness on the one hand and telling documentation for American furniture history on the other. Examination and analysis of physical features yield significant evidence and generate engaging questions. For purposes of this study, construction features, rather than more readily apparent upholstery cover colors, will be used to identify the two sets of eight armchairs.

The sixteen armchairs readily divide into two sets of eight defined by the presence or absence of a medial brace running front-to-back underneath the upholstered seats. In one group of eight, a cherry brace is dovetailed into the front and rear rails, each of which is made of ash and covered by mahogany molding strips and veneer, respectively (fig. 16). Long and narrow front glue blocks made of cherry attach to the side rails, a configuration that helps resist front-to-rear wracking of the chair. The other group of eight has no medial brace; instead, large, square blocks made of ash stabilize the front corners of the seat frame (fig. 17). These no-medial chairs also have slightly thicker seat rails, and their seat frames taper in plan slightly more toward the back, bringing the rear legs closer together than those on the set with braces. The stay rails (the lowermost horizontal framing member of the back) curve to echo the shape of the crest rail, whereas the stay rails on the medial chairs are straight. The crest rails of the no-medial chairs are noticeably thinner in depth or thickness than those of the other group, a small detail that has further implications for the way the former were assembled (discussed below). Other, less visible construction details that separate the two groups are noted in Appendix A.[11]

The two sets of chairs have three different surface colors, in keeping with stylish principles of the day. The uncarved mahogany has a clear coating that saturates the deep reddish hue of the nearly grainless wood selected for these chairs. Certain carved passages—the deeply modeled foliage in the armchair crest rails, the cornucopia arm supports on the sofas, carved acanthus fronds on the fronts of the armchair arm supports, and all of the feet—have a dark green- and deep yellow-tinted coating that yields a “patinated bronze” (or verte antique as it is also known today) appearance, recalling classical antiquity. Finally, strategic highlights are gilded and punctuated with stamped brass ornaments nailed in place. Gilded details include the acanthus-carved tips of the rear stiles and upper leg sections on the armchairs and several locations on the sofas. More subtle manipulations of the surface include recessed panels of bookmatched mahogany veneers that introduce distinct grain patterns on the sofas.[12]

Variations in surface treatment and carving between the two seating groups are minor but sufficient enough to indicate work by different craftsmen, whose identities remain unknown. On the chairs with medial braces, the tops of the arms have two broad flutes cut into them; on the no-medial chairs, the arms are molded to a serpentine profile. The gilded waterleaves that run down the tops of the front legs are different (figs. 18, 19). On the medial chairs, the leaves are naturalistically shaped and have undulating contours and pronounced ruffled edges; on the no-medial chairs the ruffling is less defined and the leaves have flatter surfaces. The leg fur and feet also differ from group to group. On the no-medial chairs, the fur has thick clumps and the paws are ovoid in shape; on the medial chairs, the fur is finer and more uniform and the feet are blockier. The foliate panels in the crest rails diverge in similar ways (figs. 20, 21). The no-medial leaves undulate more. In these iterations, the leaves look more natural than the flatter medial leaves. The grounds of the foliate panels in the no-medial crest rails have been smoothed to remove more toolmarks than in the medial counterparts (Appendix B provides a more complete listing of carving differences between the two groups).

Carving and construction features are consistent within each set; differences occur only between the sets. Although numerous, these differences exist within a narrow spectrum of possibilities. That, combined with the absence of any formal design sources and the relative rarity in New York of the features decorating this seating, argues persuasively that the craftsmen working on the second set had to have seen the first set to understand what they were required to make. The differences represent alternative and concurrent solutions to small problems—for example, how to frame a seat or how to decorate the top of an arm. Given that the seat plan is a trapezoid, at what angle should the side rails meet the rear rail of the chair to achieve a gentle taper toward the back? Should the tops of the arms be molded using a molding plane with a cutting blade of a certain profile, or should a shallow fluting plane be used twice (once for each of the two flutes) to ornament that surface? Considered together, the several variations represent intriguingly different approaches to chair making, which furniture historians readily identify elsewhere as evidence of different artisans or shops. But the Beekman armchairs hold further surprises for historians.

The upholstered backs of both sets are made with an inner frame, similar to a slip seat frame, to which the woven tapestry cover is tacked on the front face. Nails driven through this inner frame hold it within the rectangular chair back formed by the crest rail, stay rail, and narrow framing members attached to the insides of the rear stiles. Cross banding covers these additional side members and the stay rail, thus forming the border around the tapestry panel except at the crest. Decorative tape or gimp covers the tack holes on the front, and cloth bordered in more tape covers the chair back (fig. 22). X-radiography reveals internal construction (figs. 23, 24). On the no-medial chairs, the inner frame incorporates a lapped joint and is held in place with wrought, rosehead nails. On the medial chairs, the frame is butt-jointed and secured with L-shaped cut nails. Differences also occur in the construction of the crest rails. The chairs with medial braces have substantial crest rails with mortise-and-tenon joints, whereas the no-medial chairs have thinner crests attached with three dowels. Dowels are wooden pins, each end of which inserts into a drilled hole. Round tenons, in contrast to dowels, are projections cut from a larger piece of wood, shaped round rather than in the more common rectangular shape. The advantage of dowels over tenons in this location is easy to understand. The thin crest rail curves across the front plane, creating a hollow back for the sitter; the crest also rolls backward (in what was often described as a Grecian fashion). A rectangular tenon cut from the ends of these crest rails had to fit into the rear stiles at the correct angle. That angle was enough to risk breakage due to sheering or splitting along the grain. The thicker crest rails of the medial group provide more wood mass behind and in support of their tenons.[13]

Conventional marketplace wisdom holds that dowels are evidence of late construction. They are popularly associated with mechanized furniture manufacturing in the late nineteenth century, when they all but replaced the more labor-intensive mortise-and-tenon joints. Indeed, use of dowels in certain aspects of construction is prima facie evidence of out-of-period workmanship. But the presence of dowels in the Beekman armchair construction inspires reassessment of their role and asks for more precision regarding when and under what circumstances they were introduced into American furniture.[14]

Dowels appear in the 1828 Philadelphia Cabinet and Chair Makers’ Union Book of Prices for Manufacturing Cabinet Ware. That publication specifies “Doweling piece of stuff on top of back to form cape, from two to three feet long” (i.e., the shaped and finished wood cap above the upholstered back) in an entry for a “double scroll.” In contrast, an entry for a plain sofa describes stump feet that had “tenons prepared by the turner,” indicating the need to turn the rounded tenons on a lathe to true their cylindrical shape. Clearly, both joining techniques were in use by 1828. Similar wording occurs in the 1834 New-York Book of Prices for Manufacturing Cabinet and Chair Work: the labor charge for “dowels in sofas” was valued at two cents each, whereas tenons were four cents, acknowledging the additional work necessary to make the latter. The fifteen-year hiatus from when the Beekman chairs were made reflects the absence of any known New York price books published in the interim. The 1817 New-York Book of Prices for Manufacturing Cabinet and Chair Work is not explicit: it describes “Dowelling tenons, each dowel” two pence, which may refer to rounding a tenon but likely denotes a true dowel. This particular interpretation of ambiguous wording stems from the common practice of copying ideas and wording from earlier price books, whether published in the United States or London. The 1802 London Chair-Makers’ and Carvers’ Book of Prices for Workmanship brings to light a revealing reference to dowels. The manufacture of chairs with “oval, round, or bell [shaped] seat,” as described in the price book, specifies: “Dowels in the tenons, each” one-half pence. This construction detail did not refer to pinning tenons in place, despite the similarity of a pin to a dowel, because that common practice affected all chairs (and other furniture forms), whereas “dowels in the tenons” was only noted with rounded seats. The particular problem it addressed was the need to cut a tenon from the end of a curved piece of wood. The angle of the tenon veered away from the direction of the wood grain, thereby weakening the tenon, a circumstance similar to that encountered with the thin, curved crest rails on the no-medial group of Beekman chairs. Furniture makers typically call this circumstance “short grain.” American chairs with bell-shaped seats were made in Philadelphia and New York, but only one set survives with historical documentation of when it was made: a set of ten side chairs and two armchairs made in 1807 by Duncan Phyfe for New Yorker William Bayard.[15]

The use of dowels in American furniture that can be dated firmly before 1820 is rare, although ongoing observations and research bring new instances to light. A pier table bearing the engraved label of Charles Honoré Lannuier (1779–1819), which dates it between 1815 and 1819, has two dowels securing each of the rear pilasters to the platform base (fig. 25). In work related to furniture making, a tavern sign for the Williams Inn of Centerbrook, Connecticut, bearing the date 1826 painted over 1803—its probable time of manufacture—is made from two boards that are glued together and have four original dowels reinforcing the joint (fig. 26). Undated pieces of New York furniture that may be dated in the late 1810s by style and construction include a scroll-back side chair made with a harp banister, which attaches to the underside of the crest rail with dowels.[16]

An x-ray of an arm support, repaired along a grain split at the juncture of the arm, shows a dowel through the middle of the tenon and continuing into the underside of the arm and the curved portion of the support beyond the break (fig. 27). The grain split occurred at the site of short grain, precisely the problem that the 1802 London price book reference to dowelling tenons sought to avoid. The strong, longitudinal grain of the dowel stabilized this inherent weakness and was an effective repair. X-ray of another arm support, which is unbroken, shows the presence of a much longer dowel that runs from the tenon through the cross- or short-grain section of the curved arm support (fig. 28). Given the undisturbed appearance of the arm and arm support, this dowel is clearly preventative in function and could only have been installed at the time of manufacture, representing a variant of “dowels in the tenon.” A loose arm support on another armchair shows insertion of a dowel, which at first glance appears to be an attempt to repair the break. But disassembly of this break reveals that this dowel has a shoulder cut out of it (fig. 29). Such a cut only makes sense if the dowel was originally inserted into the arm support before the arm tenon was completely shaped. It and the long, undisturbed dowel both come from the medial-group armchairs, whereas the shorter dowel—which appears to be a repair—is in a no-medial chair. Thus, both sets of armchairs have dowels in different places, in the crest rail on one and in the arm support on the other.

Construction and Decoration of the Sofas

The striking differences between the two groups of armchairs beg comparison with the two sofas (see Appendix C). As with the armchairs, the sofas are different from one another, but in less obvious ways. Each is built around a rectangular frame with four medial braces made of cherry and dovetailed into the front and rear rails. The sofa with green upholstery has cherry seat rails with long, narrow cherry glue blocks attached to the side rails in the front corners and large ash blocks in the rear corners. The medial braces have full dovetails cut into each end. The other sofa, with red upholstery, has ash seat rails with small rectangular blocks in front and small triangular ones in back. Medial braces are half-dovetailed. The lushly carved foliate brackets above the animal feet of the red sofa lie within the plane of the side seat rails, as does the richly carved cornucopia above the seat. In contrast, those elements on the green sofa are more massive and project a half inch beyond the side rails. This difference in scale applies generally to the construction of each and parallels the heavier scale of the medial group of armchairs compared to the no-medial group.

Both sofas stand on carved hairy paw feet (fig. 30). Unlike most other sofas of this style, the feet face forward rather than to the sides. This ninety-degree change in orientation derives from the unusual cornucopia arm supports. Their curve is visible from the sides, like that of the feet. When viewed from the front, the cornucopias appear more or less straight. Were the feet to point to the sides, they would look detached and awkward. Each foot has the customary winged bracket above, although a composition of deeply carved scrolls and acanthus fronds replaces the usual feathers encountered on other sofas. The thickness of wood required to create these robust feet and motifs was achieved by laminating thinner boards. The laminations can be difficult to discern by eye, especially when surfaces are painted or gilded and foot bottoms are scarred by long use. The legs of the green sofa appear to be laminated from two pieces of wood, whereas those of the red sofa appear to be made of three or four pieces. Again, the number of laminations reflects the scale of the components, which are larger in the medial chairs.[17]

The modeling of the feet and fur does not readily associate the feet on each sofa with the feet on either group of armchairs. Better physical evidence lies in the acanthus leaves immediately above the feet and in the stylized floral squares or rosettes at the base of the arm supports. The leaves on the green sofa are more serrated than those on the red sofa. Similar variations in detailing can be seen on the leaves of the armchairs, which have ruffled edges on the medial group and smooth edges on the no-medial group (fig. 31). The tops of the arms provide the most definitive links between the sofas and armchairs. On the red sofa and no-medial armchairs, the surface is molded; on the green sofa and medial chairs, the surface is fluted (figs. 32, 33). Thus, physical evidence of the two sofas ties each firmly to a particular set of eight armchairs.

The lushly carved arm supports use an iconic cornucopia motif in an unusual and notable way (fig. 34). The tops of the spiral horns of plenty join the undersides of acanthus-decorated arm volutes. Each cornucopia rests on the back of a sea monster, whose oversized head and even larger gaping mouth and teeth face backwards (fig. 35). The tail of this scaly sea monster sticks out of the center of the rosette in front and below the cornucopia as it coils around itself (fig. 36). One can only imagine what comments these little details might have inspired during polite conversation at a Beekman social gathering in the 1820s.

Although exhibiting similarities in subject and arrangement, the arm supports of the sofas differ in several respects (figs. 34, 37). On the green sofa, the cornucopias are laminated, and on the red sofa, they are not. Carving differences are also evident in: the edge treatment of the cornucopia openings; the modeling and composition of the fruit; the direction and detailing of the spiral sections; and execution of the leaves on the arm terminal bases. Despite these differences, the sofas have shared idiosyncrasies establishing that one must have been copied directly from the other. The green sofa frame is about 2 1/2 inches shallower front-to-back than the red one, although the length is approximately the same at 72 1/2 inches. Finally, vertical in-fills flanking the sides of the tapestry back panel on the green sofa are almost two inches wider than those on the red sofa, indicating that the red back panel was four inches longer than the green, although the seat panels appear approximately equal in length.

Upholstery Evidence and Techniques

When James Beekman purchased the tapestry upholstery, the origin of the textile was not identified. However, contemporary newspaper references to similar textile offerings regularly called them “Gobelin,” referring to the Parisian manufactory, first established in the sixteenth century by the Gobelins family and then acquired in 1662 by Jean-Baptiste Colbert (1619–1683) on behalf of Louis XIV. The factory enjoyed royal patronage for several generations thereafter. Russell Sturgis, in his 1901 captions, introduced the possibility of Beauvais origin, another French manufacturer named for its locale, a city some fifty miles north of Paris. Similar tapestry covers were also manufactured in the factories of Aubusson, France, over two hundred miles to the south of Paris. Identifying the origins of early nineteenth-century and later tapestry upholstery can be problematic. These uncertainties stem in part from inconsistencies, disruptions, and reorganizations throughout the French tapestry industry in the years following commencement of the French Revolution in 1789. Royal patronage ended, and quality became uneven and generally declined. Nonetheless, tapestry producers needed new markets, and some French tapestries found their way to America. The earliest reference found to date is an advertisement for “A very orname[n]tal sett of tapestry covering for a room, -consisting of 2 arm, 6 common chairs and sopha, beautifully worked in rural emblems” that was to be auctioned in Philadelphia on May 6, 1793, barely four months after the execution of Louis XVI. Tapestry upholstery was occasionally sold in the years immediately following. Tapestries were sold in Boston and New York as well, such as Aubusson “sopha and chair Bottoms and Backs, in a great variety of sets” to be auctioned in Boston on November 17, 1796. By the turn of the century, the most frequent references came from New York, such as an advertisement in 1801 for “4 handsome pcs [pieces] of tapestry of Gobelin manufacture, . . . these articles would command a very high price in Russia.” Some tapestry sets were sold with larger pieces that may have hung on walls. The “eight chairs and three sofas of Goblin Tapestry” discussed above had “five pair curtains to suit, with elegant trimmings,” which might also have been tapestries but could have been color-coordinated silks made en suite. Gouverneur Morris (1752–1816), who lived in France from 1789 to 1794, described the tapestry hanging in the drawing room of his house, Morrisania, as a picture of “Telemachus rescued from the charms of Circe by the friendly aid of old Mentor.” In all of the advertisements, whether printed in New York, Philadelphia, or Boston, “Gobelin” likely referred generically to French-made tapestries rather than to the specific products of that factory, although in some cases it accurately identified the source of the tapestries in question. The names Aubusson and Beauvais were rarely mentioned; however, at least one set of Beauvais tapestry was used in America. A set of twelve armchairs and one sofa made in Philadelphia for Eliza (1793–1860) and Edward Shippen Burd (1779–1848), probably about the time of their marriage in 1810, survived into the early twentieth century with Beauvais covers. Despite the esteem with which tapestries were marketed in America in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, examples other than those on the Beekman sofas and armchairs—and the tabouret discussed in Appendix D—that survive on American-made frames are virtually unknown.[18]

The upholstery on the Beekman chairs encompasses the woven wool tapestry covers, decorative tapes or trim, and the foundation or under upholstery. The tapestry chair covers depict thirty-two different scenes—one for the back and one for the seat of each of the sixteen armchairs. The sofa covers add four more scenes to the total. Back panels show people; the seats show animals, in keeping with the convention that people did not sit on people (fig. 38). The backs exhibit young women or men in tranquil settings, usually engaged in peaceful garden- or farm-related tasks such as feeding domesticated animals, tending plants, gathering fruits and vegetables, or fishing. The broad sofa panels narrate courting scenes. The scenes featuring animals on the seats range from peaceful and bucolic compositions to more violent encounters between the hunter and the hunted. The red tapestry set has oval floral borders, whereas the green set has elaborate drapery, tassels, and floral festoons. Each of these decorative strategies occurs in other late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century French tapestry covers. Similarly, the specific panel designs, reproduced from cartoons, turn up elsewhere. Within the Beekman seating, the sofa backs illustrate duplication of the image: they depict the same composition of two people dancing in the center, a cluster of three in conversation on the left, and a piper on the right. These two tapestry panels differ in foliated background details, and one is against green and the other red, each accompanied by the appropriate drapery and floral devices. This repetition of design must have been happenstance; no armchair scenes repeat, although two backs—one red and one green—are similar (figs. 39, 40): they each show a boy or young man holding an oval portrait-like device, possibly a shield. This particular design may have been adapted from another design of a young actress holding a mask, an image woven by the Gobelins Manufactory in 1725, and taken in turn from a painting or print source. Specific sources have not yet been identified for the images on the Beekman covers. Esther Singleton identified them as representing Aesop’s fables. Indeed, some may have been inspired in general by that fountain of imagery, but the animals appear to be representations without Aesop’s characteristic narrative cues. All of the back designs are tranquil and appear devoid of moral or ethical themes.[19]

The designs on the tapestry covers do not fit the armchair seat frames precisely. The curved drapery motif across the bottom of the green seat covers and the outermost stylized vine border on the red chairs intersect the straight seat rail moldings in front (figs. 39, 40). The relatively thin upholstery stuffing and correspondingly thin seats accentuate this visual awkwardness. Most French chairs, in contrast, have thicker upholstered seat foundations, creating a higher vertical dimension in front. Many French chairs—but not all—have bowed seat rails in front, which conform better to the green and red designs. Yet like the Beekman chairs, tapestry covers used in some other French seating sometimes do not coordinate exactly with the shape of the chair frames either. The decision to make the Beekman chairs with straight rails may also have taken into consideration the sofas, whose overall rectilinear design favored a straight front.[20]

Fitting the back panels was simpler and yielded better aesthetic results. The width of the mahogany crossbanding around the upholstered panel and the width of a horizontal insert across the bottom allowed adjustment within the frame of the back. No discernable adjustment was necessary from chair to chair, even from one set to the other, because the tapestry back covers are all approximately the same dimensions. The sofa covers, however, are of notably different dimensions. Although each sofa frame is about seventy-two inches wide, the red tapestry sofa back cover is about four inches longer from side to side than is the green back. The difference is visible where mahogany veneers have been glued to the frames just inside the rear stiles and arms (figs. 41, 42). Those on the green sofa are two inches wider, thereby compensating for the shorter dimension. More ambitious design adjustments compensate for the narrower depth of the green seat cover. The overall frame of the green sofa is about 2 1/2 inches shallower than that of the red sofa. Even with that adjustment, the seat cover had a narrow strip of green wool sewn along the back border to extend its depth and provide a tacking edge. The wool strip was covered with a strip of wood, now missing. The raw bottom edge of the tapestry back cover is visible in figure 37. The original strip was probably made of mahogany, cut to a simple cove molding, and veneered with mahogany crossbanding similar to that on the armchairs. Each sofa, whose construction and carved detail tie it to either the medial or no-medial set of armchairs, bears the matching tapestry -covers—namely green on the medial set and red on the no-medial set.[21]

The unusual problem of fitting pictorial tapestry covers onto New York chair and sofa frames brings into consideration a pair of sofas originally owned by Robert L. (1775–1843) and Margaret Maria (1783–1818) -Livingston (figs. 43, 44). The sofa frames, made in New York, retain their original French tapestry covers, outer side and back panels (colored red on one sofa and a now-faded blue on the other), and complete foundation upholstery. The Livingstons likely acquired the tapestry covers when they lived in France from 1801 to 1805, assisting Margaret’s father, Robert R. Livingston (1746–1813), whom Thomas Jefferson had appointed to serve as the United States minister to France. The Livingston sofa frames were probably made soon after the couple returned to New York. Following Robert’s death in 1843, the sofas passed through generations of Livingston ownership. Much of that time, from about 1865 until 1950, they were in storage at the Manhattan Storage and Warehouse Company—a remarkable circumstance that preserved these important artifacts of furniture history. The sofas are in extraordinarily good condition, with no patches and no extra nail holes indicating any alteration of the upholstery. Examination of the wool tapestry not exposed to light shows that much of the blue now visible was originally green, the yellow colorant in the dyes having faded. The sets of backs and seat covers for each sofa are similar in design, suggesting manufacture in the same time and place, but no two covers appear to be specifically paired. The pictorial image of one back looks fuller and richer than the other, and the draped and floral borders differ in details. More important in terms of aesthetics, the inside arm panels differ substantially from the backs and seats (fig. 45). In fact, they look patched-in from unrelated sources, although the integrity of the upholstery application confirms their originality to these frames. Their differences, as well as the less obvious differences among the large back and seat panels, suggest that matched sets were not available to the Livingstons for -purchase. Instead, they had to be content with more limited selections of these rare covers.[22]

Unlike the Livingston sofas, the Beekman sofas and armchairs were used throughout the nineteenth century and into the opening years of the twentieth. Accordingly, they exhibit evidence of upholstery repairs and refreshenings. Three generations of decorative trim outline the tapestry panels on the chairs, and two generations survive on the sofas. Correspondingly colored tapes made of woven wool, and others of silk, each appear on the green and red armchair sets. Brass tacks spaced about an inch apart accompany the silk tapes (fig. 46). In addition, some red-set chairs display a third, brighter, woven tape colored a deep red that is modern, possibly applied when the chairs were in the custody of the New-York Historical Society, although no records document their application (fig. 47). Each of the sofas has silk and brass tack treatments on the backs and brass tacks with a different woven tape on the seats. Making sense of this assortment of materials requires sorting through all of the upholstery evidence on the various chairs and sofas to determine sequences of restoration through several generations of ownership. However, examination still does not resolve all of the questions, including basic sequences.

Twelve of the sixteen armchairs have original upholstery foundations for the seats. Although not exposed to view, the back foundations are also likely intact, because backs receive significantly less wear and tear than seats do. A few of the Beekman chairs appear to have had stuffing (cotton batting) added from the outside back so as to push the front surface of the upholstered back forward (i.e., towards the sitter), making it fuller. The original seat material, which is readily visible from underneath, was applied in two different ways. The seats of chairs with medial braces have three strips of webbing two inches wide running front to back and two running side to side. On the no-medial chairs, the webbing arrangement is reversed (figs. 16, 17). The foundation upholstery of the backs is covered by the tapestry panels in front and by solid green or red cloth panels (coordinated with the tapestry background color) in the back. On one chair in the medial group, the back panel is open enough to reveal one vertical and two horizontal strips of webbing (fig. 48). A broken and reglued arm support on another chair in that group reveals the use of wood blocks to define the corners of the seat upholstery (fig. 49). Thin grass rolls atop the front rail and along the side rails square out the seat. On the no-medial chairs, a more substantial grass roll without wood blocks in the corners shapes the front edge all the way across the seat (fig. 50). The sides have no grass roll and taper from the middle of the seat to the edges. Without the large wood blocks to provide shape, the seat corners look and feel softer. Figures 49 and 50 also show differences in how the tapestry seat covers were cut to fit around the rectangular base of the respective arm supports (see also fig. 46). In the medial or green set, the upholsterer cut in from the side edge of the seat cover aligned with the back edge of the arm support, whereas in the no-medial or red set, his cut intersected the middle of what became the rectangular arm-support opening. In each instance, diagonal cuts within the rectangle allowed the upholsterer to fold or cut away the triangular tabs to open the rectangle and minimize fraying of the woven tapestries. Decorative tapes bordered the rectangle and covered the cut on the side edge of the seat. On both sets of chairs, the upholstered backs were padded without rolls or other shaping devices. Other differences exist between the two sets regarding specific types and weaves of upholstery webbing and cloth used to contain the stuffing.[23]

The differing techniques (and materials, to a lesser degree) used on each set of seating indicate that at least two upholsterers were responsible for that work. An invoice to James Beekman from William Denny documents his upholstery of one set, (fig. 51), but no invoice for the other has come to light. Denny wrote his invoice on June 26, 1819, the same day as Banks’s first furniture bill, indicating coordination between these two craftsmen. Like Banks, Denny is somewhat enigmatic. He is listed as an upholsterer at 64 Nassau Street in the 1819–1820 New York City directory. That directory also lists a William Denny with no accompanying trade designation at 44 Nassau Street, and a third William Denny, referred to as a blockmaker, at 40 Washington Street. Blockmaker Denny had been listed each year since 1815 at various addresses, but no other William Denny appears in those earlier directories. More interesting, Denny’s name disappears from the directories entirely after the 1819–1820 edition. The disappearance of one William Denny from the written record was noted in the New-York Gazette on October 23, 1819: “DIED. Suddenly, on Saturday evening last, Mr. WILLIAM DENNY, of the firm of John Fine & Co. aged 31 years.” Denny might have suffered a fatal accident or possibly succumbed to yellow fever, which plagued the city until 1823.[24]

But what about the two other William Dennys, especially the one listed as an upholsterer? The 1819 New York City Jury Census provides some insight. Organized by street, this census lists Thomas L. Jennings, a forty-year-old tailor, at the 64 Nassau address, and Thomas D. Penny, a tavern keeper (identified as “porterhouse” in the census, reflecting the term’s use in early New York for establishments that served porter), age thirty-eight, at 44 Nassau Street. The only William Denny mentioned is the blockmaker, listed at the Washington Street address. Given all of this evidence, it seems unlikely that three William Dennys resided in New York City for a brief moment, yet were not recognized in the 1819 Jury Census. Instead, all three city directory listings probably refer to the same person, who began dividing his time as he pursued a new trade: he could be found at the Washington Street blockmaker establishment, where he had worked for several years; he probably resided at 44 Nassau Street; and he may have begun his new upholstery trade on a tailor’s premises. Denny’s sudden death late in 1819 may explain why the U.S. Census lists a William Denny in 1820, assuming census takers began their work before year-end. Regardless, no one by that name appears in the 1830 U.S. Census of New York City.

With Denny gone, the second set, which Banks began making in the autumn of 1819, had to be upholstered by someone else. No evidence suggests who that person might have been, but many upholsters were active in New York City during the opening decades of the nineteenth century. Moreover, James Beekman had dealings with several upholsterers around the time he commissioned the seating. For example, he paid upholsterer John Voorhis $20.00 for sixty-four yards of fringe on October 5, 1818, an amount equal to the trim requirements of a single set. Each armchair required about six yards, for a total of forty-eight; one sofa took about fifteen yards, leaving a mere yard left over from the order. Beekman bought yard goods and “Borders” from another upholsterer, Peter D. Turcot, on July 18, 1819, but neither the price nor the yardage suggests any association with the tapestry seating. And Lawrence Ackerman charged him £5.14.00 on July 12, 1821, for “repairing sofa.” Since John Banks had just made Beekman two new ones, which presumably did not yet need repair, Ackerman’s bill must have referred to some other piece of furniture.[25]

Although variations in construction and upholstery techniques place the seating made by Banks into two clearly discernable groups, inconsistencies occur with regard to the tapestry covers: two chairs from the medial group have red covers and two chairs from the no-medial group have green covers. Denny’s and Banks’s bills for the earlier set indicate that it was completed by June 1819, more than six months before the second set. Given all of the similarities in upholstery and woodworking that exist within each set, imagining a mixing of the red and green tapestry sets from the outset seems untenable. Consequently, some covers from both sets must have been removed from the frames at a later date and reinstalled on different frames, and in some instances, installed on frames from the other (i.e., “wrong”) set.

Payments to craftsmen in the mid-nineteenth century, although cryptic, suggest that such a switch likely occurred. In 1844 James William Beekman (1815–1877), who had inherited Mount Pleasant and other estate assets from his childless uncle James Jr., paid H. Haddaway (possibly Henry Hathaway of uncertain birth and death dates) for “rubing & varnishing” and occasionally oiling, polishing, and repairing a lot of furniture. In addition to one entry for twenty-two chairs, the bill lists the two tapestry sets, continued on the back as “2 sofas” and “16 chairs.” Haddaway’s work is not detailed but can be inferred by the associated charges, which are the same as the rubbing and varnishing costs on the front side. Three years later New York upholsterers Joseph Dixon and Henry Stoney of 555 Broadway billed James William for “repairing Tapestry chairs, $30.00.” Several other entries in Beekman’s cash book reference “repairing chairs,” “arm chair, &c,” “cleaning furniture,” and “repairing furniture” over several years in the 1850s, although none specifically mentions the tapestry-covered furniture or gives further details. Various payments for house carpentry, wall papering, and new pieces of furniture signaled a lot of activity, all of which seems appropriate and customary, reinforcing ongoing use of and interest in the armchairs and sofas throughout changing domestic circumstances. About 1897, when Cornelia Augusta Beekman (1849–1917) had her full-length portrait executed in pastel (fig. 52), she appreciated these nearly eighty-year-old chairs enough that she posed with one, which can be recognized specifically as the chair illustrated in figure 53. Regrettably, these references are too vague to determine more precisely what repairs to the sets were made and when.[26]

Physical evidence is more revealing. One of the two red-upholstered armchairs from the medial group has its red wool back panel cut away to the brass-tacked borders, exposing an old repair across the top rail of the back framing (see fig. 48). The slightly arched piece of wood immediately below the mahogany crest rail was wrapped in a strip of linen impregnated with glue. The only apparent function of the linen covering was to repair or stabilize damage. This mending technique, commonly used in the furniture making and upholstery trades, cannot be dated, but it demonstrates that some of the Beekman seating needed repair. Similarly, a row of unoccupied holes underneath the bottom edge of the outside-back panel is from an earlier campaign to secure a textile, perhaps this same fabric if the back panel had been switched at an earlier time.[27]

The remains of the present back panel are held in place by silk tape and brass tacks. Much of the silk on the Beekman furniture has deteriorated over time, and sorting through the physical evidence of the various tapes does not yield conclusive results. Accurate dating of upholstery trim typically requires accompanying bills of sale or other manuscript evidence of manufacture or purchase. If original, trims can also be dated by bills, documents, or other evidence related to the seating on which they are installed. In the case of the Beekman seating, there is little basis for concluding whether the silk or the wool tapes present are earlier, and reasonable scenarios can be posited in support of either sequence. One could assign the earlier date to the silk tape because it is the finer material and more in keeping with the ambitious qualities of Beekman’s tapestry seating. Original attachment of the silk tape may have consisted of few place-holding tacks and glue, neither of which would have left an imprint on the tapestry or chair frame definitive in establishing that it was the first trim used. The brass tacks have iron shanks, and some of their heads appear to have a gold or other metallic coating. These tacks may have been added later in the nineteenth century, both as a decorative treatment and as a way of reinforcing attachment of the fragile silk trim.

Of the three types of trim on the Beekman seating, silk tape is by far the most widely present, and on the sofas silk is the only decorative trim. The sofas also have a second, partially woven silk tape, representing a fourth trim. Used around the seat covers but not the back covers, it is the later of the two silk tapes. Both sofas have replaced foundation upholstery in the seats, which required removal of the original tapes and the tapestry seat covers when that work was done. As with the armchairs, the sofa backs are less disturbed. Although the outside back panels have been removed and additional webbing has been installed over the original webbing and stuffing, the tapestry back covers seem not to have been removed (fig. 54). The new seat foundations were made with different materials and techniques. The new webbing, which matches that added to the backs, is wider and made of jute rather than linen (and possibly hemp), and it was installed with no gaps between the straps. The work was probably done in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century. Four of the no-medial armchairs have new foundations made of similar materials applied in a similar fashion. The repair of original foundation upholstery on seating from that group does not indicate that the materials and workmanship were inferior to that of the set with medial braces. Rather, the braces deflected the sitter’s weight off the webbing and helped preserve the foundation upholstery. The four armchairs with newer foundations have deep red tapes, which represent the third and most recent generation found on that seating form (see fig. 47). Somewhat jagged renailing of the seat covers at the upholsterer’s scissors-cut below the arm support also indicates reapplication of the seat covers following installation of the new foundations on these four chairs.

Examination of two armchairs with original foundation upholstery and wool trim yielded evidence that their tapestry covers had never been removed. Sections of upholstery were carefully detached from the back frame of one chair and the seat of the other. Separation of the back panel revealed a clear and solitary line of ten tacks spaced roughly an inch apart (fig. 55). In contrast, lifting a section of upholstery just below the crest rail of an armchair with new trim revealed multiple rows of tack holes, indicating that this back cover was either removed from the frame and reapplied or was from another chair in the set (fig. 56). There was no evidence of additional holes on the tapestry covers of the chairs with original trim, indicating that they were never on any other example. Two unoccupied nail sites were observed in the seat frame of yet another chair. The purpose of those sites remains unknown, but two holes is far too few to suggest the presence of an earlier upholstery cover. The extra holes may have been introduced by the upholsterer when he positioned and temporarily tacked the seat cover in place before attaching it permanently. Alternatively, the holes may have come from sprigs holding silk trim, now replaced for some un-known reason.

Finish evidence from the green sofa establishes the originality of these tapestry covers much more conclusively. That sofa has a shorter back panel than the red one, requiring the use of wide strips of mahogany veneer to cover the side edges of the inner frame that supports the tapestry panel between the mahogany rear stiles (see figs. 41, 42). Microscopy establishes that the finish layers on the veneer strips match those on other primary-wood components of the frame, indicating that they are original to the sofa frame. Had the green sofa been upholstered previously with any other back panel, it is highly likely that the dimensions of that textile would have covered the side edges, thus eliminating the need for this awkward solution. The veneer strips represent original modifications, as do the adjustments along the back edge of the seat covering—namely, the added strip of green textile and the now-missing mahogany coved molding.[28]

Establishing the originality of the tapestry covers to the seating frames is more than an exercise in connoisseurship. It directly challenges another physical finding—a yellow textile fragment trapped under a nail head on the frame of one of the armchairs. While this might suggest that the tapestry upholstery was preceded by an earlier covering, the evidence presented above precludes that conclusion.[29]

Understanding the Beekman Seating

The Beekman seating is innovative, extraordinarily well documented, and was owned by a leading New York City family—an unusual and potent combination for early American furniture history. Yet detailed study and focus on this furniture occurs only now, rather than decades earlier. A likely cause for this delay stems at least in part from some of the unfamiliar features integral to the two suites, coupled with the lack of manuscript documentation of manufacture that only recently has come to light. Although all aspects of the chair and sofa designs drew from an ornamental vocabulary in place in New York City by the late 1810s, the particular combinations and expressions in the Beekman seating differ from other New York work (as well as from that of other American urban centers), and the tapestry upholstery is unconventional. The rich historical documentation that now accompanies this furniture reveals craftsmen and circumstances that add a degree of mystery to the narrative. Collectively, this furniture raises engaging questions for which there are not ready answers. Nevertheless, the contribution of the Beekman seating to a more comprehensive understanding of early American furniture history is substantial.

Differences between the two seating groups are significant. In short, had manuscript evidence not survived for both sets, they likely would not have been assigned to the same maker. This circumstance alone makes the Beekman seating notable. The two sets are a reminder that accurate furniture history cannot be written without adequate manuscript references and support. These sets also document the occasional departure from consistency that occurred within or between historically related suites.

Notions of consistency deserve more attention. Setting aside construction and upholstery details that may be noticeable only to a small group of furniture historians, collectors, and connoisseurs, the differences in carving, curve of the chair backs, and other particulars may be seen clearly by more casual observers of the two Beekman sets. These differences exceed modern ideas about what degrees of consistency are generally “acceptable” in handwork. Did not James Beekman and his family notice, or care? Since one set copied the other, why were the workers in question not motivated to replicate the first set more accurately? From the perspective of furniture history, the differences between the two sets generate concerns. Specifically, they undermine generally accepted notions of consistency that characterize or define individual pre-industrial furniture shops in America. In turn, those identified shops form the building blocks of further maker identifications of anonymous furniture. What happens when furniture historians try to generalize about John Banks’s work from this well-documented—yet inconsistent—furniture or use it to help interpret related furniture?

Some comfort may follow from recalling other anecdotes in American furniture history that, quite frankly, are equally disquieting. Specifically, there are a few, perhaps even several, well-documented instances in which furniture pairs (represented here by the two Beekman sets) are significantly different from each other. Other Beekman-owned furniture, for example, includes a “pair” of Chippendale-style cabriole-leg card tables that resemble each other only generally. Differences include front skirt veneers, carving details, shaping along the bottom edges of the rear fixed and swing rails, and construction details. Long considered a pair because they survived together with the same provenance, these two card tables may have been purchased at different times. To this point, furniture historian Lauren Bresnan found manuscript evidence for only one table—purchased in 1768 by James Beekman, builder of Mount Pleasant, from New York furniture maker William Proctor. A pair of turret-corner Philadelphia Chippendale card tables appear very similar but have significant construction differences. In 1770 Philadelphia cabinetmaker Thomas Affleck billed John Cadwalader for another pair of card tables that exhibit a similar range of differences. This pair was unambiguously listed as “2 Commode [i.e., serpentine] Card Tables @ £5” apiece. Their differences contrast with another pair of Cadwalader card tables, not listed in that or any other extant bill, composed of two truly identical tables, thus clearly demonstrating the degree to which craftsmen could match pieces of furniture if they intended. In the Affleck-Cadwalader easy chair, made at the same time, noticeable variations in carving exist between one side seat rail and the other. The set of chairs made for Samuel or Daniel Crommelin Verplanck of New York divides into two groups based on differences in the splat patterns and in decorative carving details. Last, the Livingston pair of New York sofas with original tapestry covers exhibit significant differences in the frames, upholstery materials and construction, and tapestry covers. Although both are believed to have been made in New York at the same time, they are structurally dissimilar from one another. In addition, inlay decoration in the crests and arms looks different. Aside from subtle differences in the pictorial qualities of the tapestry covers and disparities—but unnoticeable to the casual viewer—in the size and placement of upholstery webbing that supports the seats, the original outer side and back panels are strikingly different. One sofa uses a red harrateen or moreen, whereas those of the other combine blue velvet out sides, applied with the nap on the inside (see figs. 43, 44), with the same red outside back as the first sofa. The color selections of the out sides create inexplicable differences in the appearance of this pair.[30]