Elizabeth Paddy Wensley, artist unknown, 1670–1680. Oil on canvas. 41 1/2" x 33 1/4". (Courtesy, Pilgrim Society, Plymouth, Mass.)

Chest attributed to the shop of Thomas Dennis (w. 1659–d.1706), Ipswich, Massachusetts, 1676. Red and white oak. H. 31 11/16", W. 49 5/8", D. 2 25/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

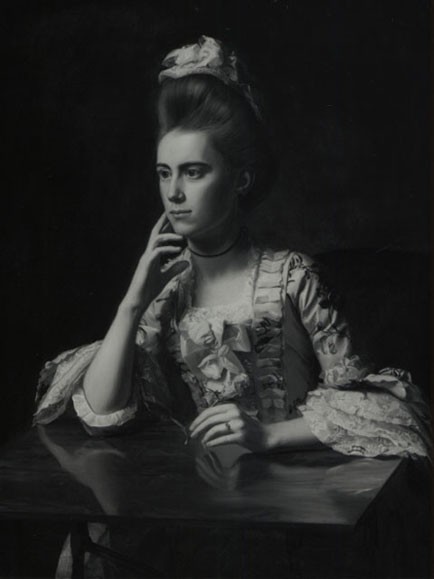

John Singleton Copley, Dorothy Wendell Skinner, Boston, 1772. Oil on canvas. 39 3/4" x 30 1/2". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; bequest of Mrs. Martin Brimmer, acc. 06.2428) ©2000 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. All rights reserved.

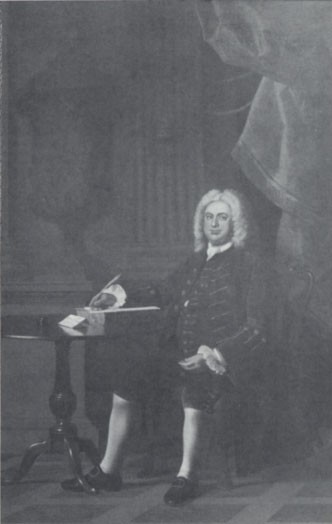

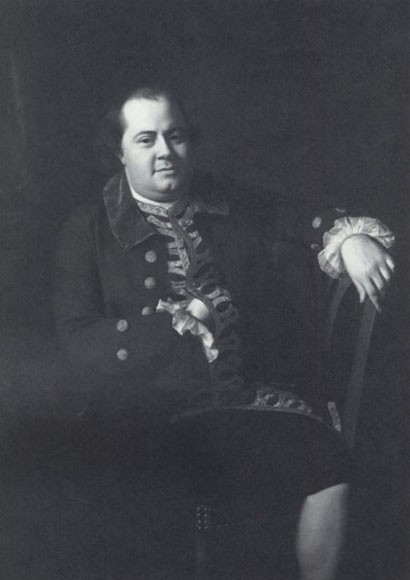

Portrait of a Gentleman (possibly Elisha Hutchinson, formerly identified as Sir George Downing), attributed to Thomas Smith, Boston, ca. 1675–1690. Oil on canvas. 43 1/2" x 35 7/8". (Courtesy, Harvard University Portrait Collection, Gift of Mr. Robert Winthrop, Class of 1926, to Harvard College, 1946. © 2004 President and Fellows of Harvard College.)

John Singleton Copley, Paul Revere, 1768. Oil on canvas. 35 1/8 " x 28 1/2". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Gift of Joseph W., William B., and Edward H.R. Revere, acc. 30.781) ©2000 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. All rights reserved.

John Singleton Copley, Thomas Hollis, 1765-1766. Oil on canvas. 94" x 58". (Courtesy, Harvard University Portrait Collection, Commissioned by the Harvard Corporation, 1765; ©2004 President and Fellows of Harvard College.)

The Old Maid, London, 1777. Engraving on paper. 10 3/16" x 8 3/16". (Courtesy, Library of Congress.)

Phillis Wheatley, Negro Servant to Mr. John Wheatley, of Boston, London, 1773. Engraving on paper. 6 1/2" x 4 3/8". (Courtesy, New York Public Library.)

John Singleton Copley, Mrs. Ezekiel Goldthwait, 1771. Oil on canvas. 50 1/8" x 40 1/8". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Bequest of John T. Bowen in memory of Eliza M. Bowen, acc. 41.84) ©2000 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. All rights reserved.

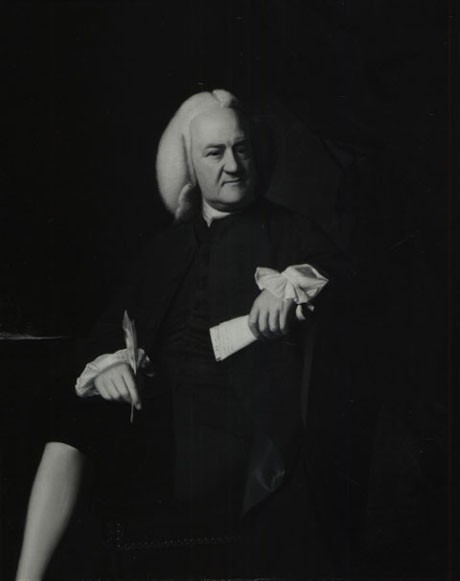

John Singleton Copley, Ezekiel Goldthwait, 1771. Oil on canvas. 50 1/8" x 40". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; bequest of John T. Bowen in memory of Eliza M. Bowen, acc. 41.85) ©2000 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. All rights reserved.

High chest possibly decorated by Charles Gillam, Saybrook or Guilford, Connecticut, 1703–1725. Pine, tulip poplar, and ash. H. 54 5/8", W. 40 1/8", D. 21 1/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Seventeenth-century couple from “a scarce print by Marshall” in Joseph Strutt, A complete view of the dress and habits of the people of England, 1799. (Special Collections, Dimond Library, University of New Hampshire.)

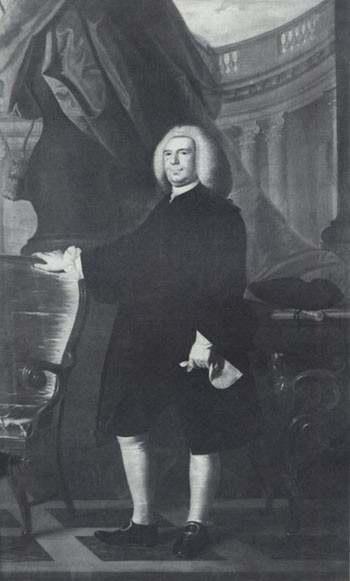

John Singleton Copley, Thomas Hancock, 1764–1766. Oil on canvas. 95 1/2" x 59 1/2". (Courtesy, Harvard University Portrait Collection, Gift of John Hancock, nephew of Thomas Hancock, to Harvard College, 1766; ©2004 President and Fellows of Harvard College.)

John Singleton Copley, Daniel Rogers [?], 1767. Oil on canvas. 50" x 40 1/2". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Bequest of Dr. Morrill Wyman.)

Cupboard, inscribed “Hannah Barnard,” Hadley, Massachusetts area, ca. 1715. Oak and yellow pine. H. 61 1/8", W. 50", D. 21 1/4". (From the collection of the Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village; photo Amanda Merullo.)

Chest with drawers, initialed “SH,” Hadley, Massachusetts area, ca. 1710. Oak with white pine. H. 45 1/4". W. 44 1/2", D. 18 1/2". (Courtesy, Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association, Memorial Hall Museum, Deerfield, Massachusetts.)

Embroidered bed hangings, England, 1680–1720. Wool on fustian (linen warp, cotton weft). (Courtesy, Wadsworth Atheneum. William B. and Mary Arabella Goodwin Collection. Bequest of William B. Goodwin.)

Chest with drawers, initialed “MS,” Hadley, Massachusetts area, ca. 1715. (Courtesy, Wadsworth Atheneum.)

Sampler by Mary Holingworth, Salem, Massachusetts, ca. 1665. Silk on linen. 24 3/4" x 7 1/2". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Mass. Bequest of George Rea Curwen, 1900, 4234.39.)

Sampler by Abigail Pinniger, Rhode Island, 1730. Silk on linen. 16" x 9 3/4". (Courtesy, Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, gift of Miss Susan B. Thurston, 14.60.)

Diagram on pages 324-325 of pie crust vents from The Accomplish'd Lady's Delight by Hannah Wolley, 1675. Reference (shelfmark) Douce P 412. (Courtesy, Bodleian Library, University of Oxford.)

Settee, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1800–1810. Mahogany and birch with maple and white pine. H. 34 3/4", W. 84 1/8", D. 16 1/4" (seat). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

High chest of drawers, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1733. Walnut and maple and walnut veneers with white pine. H. 86 1/4", W. 40 1/2", D. 22 1/4". (Courtesy, Warner House Association, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Thaxter Swan; photo, David Bohl.)

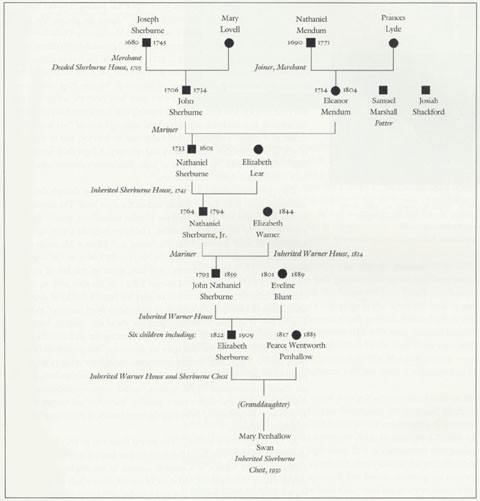

Provenance of the high chest illustrated in fig. 24: Mendum–Sherburne–Warner–Penhallow connections.

Detail of the initials and date on the inlaid heart of the chest illustrated in fig. 24. (Photo, Brock Jobe.)

Detail of the inlay on the upper drawer of the high chest illustrated in fig. 24. (Photo, David Bohl.)

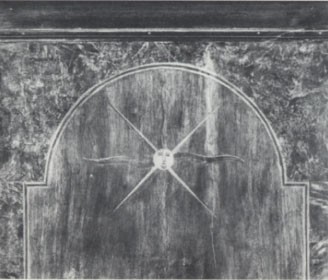

Detail of compass star inlaid on the case sides of the chest illustrated in fig. 24. (Photo, David Bohl.)

Prudence Punderson, “First, Second, and Last Scenes of Mortality.” (Courtesy, The Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford, Connecticut)

I am not a furniture historian. I am a social historian who in a moment of whimsy (or hubris) agreed to keynote a furniture symposium. I must admit that my initial forays into the literature were daunting. References to “stop-fluted pilasters,” “pendant drops,” and “double-arched beads” sent me scrambling back to more conventional history.[1] But as I persisted, I recognized beneath the technicalities a passionate enterprise of discovery. Material objects literally carry the print of their maker’s hand, but only those who are willing to narrow their gaze will find that evidence.

As the essays in this volume show, however, objects are not enough for historical discovery. The best furniture studies take us full circle from objects to documents and back again, showing how chests and chairs reveal societies and events as they derive new meaning from changing economic and social contexts. Ned Cooke’s marvelous phrase “part-time is not part-skilled” could only have been created by a person comfortable both in the archives and the gallery. Ned examined furniture, but he also used account books, probate records, and tax lists—the routine sources of social history—to reconstruct the rhythms of work among Connecticut furniture makers.[2] As I began my own research, I hoped to follow that example, but I also wanted to broaden the canvas of furniture scholarship by suggesting new ways of connecting it to social history.

Fifteen years ago, Robert Blair St. George urged his fellow scholars to recover the lives of the men who made furniture. “While studies of material life must begin with the artifact,” he wrote, “too frequently is the maker miraculously forgotten, obliterated by the supra personal creep of diffusion patterns or reduced to a finite set of oppositions that profess to capture his mind without capturing his feelings.”[3] The makers of early American furniture have begun to emerge from the shadows. We know far too little, however, about the auxiliary crafts related to furniture construction. Where are the upholsterers, stainers, painters, and chair caners who completed the work of cabinetmakers, joiners, and chairmakers? We also know too little about the ordinary patrons, including the female patrons, who made this work possible. Nor has enough been written about the relationship between furniture and other consumer goods, including ceramics and textiles. To focus on furniture without considering the broader consumption patterns of ordinary households is to leave out a vital part of the story; to think about consumption without considering the social context in which tables, chairs, chests, blankets, petticoats, and pots were acquired is to divorce objects from the human relations that gave them value. From my own position as a historian of early American women, I would argue that an essential step in broadening furniture scholarship is to begin thinking about gender.

Gender is the social construction of sexual difference. It is present symbolically in language, gesture, and costume; structurally in the organization of law and politics; and practically in the ordering of daily life. Yet it is often invisible. As Mary Douglas has written, “A . . . social order generates its pattern of values, commits the hearts of its members, and creates a myopia which certainly seems to be inevitable.”[4] For those with eyes to see, however, the social construction of gender can be found everywhere—even in furniture. To begin with, the visual and tactile qualities of furniture suggest new ways of thinking about the body and its reconfiguration over time. In the first half of my paper, I will pursue that theme, relating furniture to recent scholarship on clothing. The second half of the paper raises a more concrete issue—the question of female ownership and inheritance. My objective is not to give a definitive statement either about gender or furniture but to raise questions for further analysis. The methods I have suggested can be applied to other themes in social history, particularly to race and ethnicity, but since gender cuts across many human boundaries, it is an appropriate place to begin.

When I attended the Portsmouth furniture exhibit at the Currier Gallery in the winter of 1992, I was struck by the anthropomorphic (as well as zoomorphic) qualities of the artifacts. The notion that tables and chairs were somehow alive was reinforced by many of the period terms used to describe furniture and its components: head (pediment), legs, heel, feet, toes, arms, elbow, ears, cheeks (wings of an upholstered chair). Certain twentieth-century terms, such as bonnet (a closed head), are also anthropomorphic and gender based.[5] The fact that furniture forms are related to human forms is hardly surprising. We spread our bodies on and around furniture, extending our own trunks and limbs by appropriating the trunks and limbs of trees. A table is a kind of lap, an enlarged pair of knees for working or eating. A chair, too, offers supporting thighs for sitting on and a spine (or cushioned breast) to lean on. Clearly, the human body shapes furniture just as furniture constrains and sustains the human body.

I wanted to push that insight one step further. If tables and chairs have arms, legs, and toes, do they also have sex? That question forces us to define sexual difference. We could take a Freudian approach, looking for projecting appendages or inner and outer space. I chose a more historically grounded method derived from costume history. Since clothing almost always differentiates adult males from females, it is a perfect vehicle for understanding the ways in which gender changes over time. As Valerie Steele has written,

An article of clothing has no inherent meaning. Trousers do not have the idea of masculinity built into them, nor does a skirt automatically signify that the wearer is either female or feminine. The meaning of clothing is culturally defined. . . . It is the history of clothes and the context in which they are worn that determine the meanings that we ascribe to them.[6]

A search for the aesthetics of gender in furniture might begin, then, with a series of comparisons between furniture forms and human forms—or, more precisely, elite human forms as defined by fashionable clothing.

To explore some of the possibilities of this form of analysis, I compared a series of well-known New England portraits with furniture from the same period. I was surprised and delighted to see how in each period clothing rhymed with furniture. The lace, ribbon, lawn, and silk on Elizabeth Wensley’s sleeves (fig. 1), like the carving, paint, and moldings on a contemporary New England joined chest (fig. 2), form a series of clearly defined bands, each embellished with surface ornament. In both the painting and the chest, variety is the dominant aesthetic principle, as though each artist tried to see how many different colors and textures could be layered on one form. These late-seventeenth-century objects contrast with two eighteenth-century artifacts, a Connecticut high chest attributed to Eliphalet Chapin (1741–1807) (fig. 3) and John Singleton Copley’s portrait of Dorothy Wendell Skinner (1733–1822) (fig. 4). The eighteenth-century forms are sculptural, light, and playful. Height, rather than width, gives dignity to Chapin’s chest. The chest’s “head” is crowned with an open, scrolled ornament, whereas Dorothy Skinner’s is crowned with a delicate, lacy cap. Gilded looking glasses from the period also employ architectural elements and ornaments such as those on Chapin’s chest. An eighteenth-century lady, her hair dressed in the latest fashion, might see a double reflection of herself in such a mirror.

Costume historians warn against the tendency to abstract gendered meanings from broad stylistic changes that affect both sexes. Claudia Kidwell offers a particularly compelling example:

In 1840 an individual strolled through the city park cutting a fashionable figure in bottle green cloth and yellow brocaded silk. The figure was shaped like an hourglass. The fashionable silhouette had sloping shoulders, a padded chest, and a narrow, cinched waist. The clothing was seamed to fit snugly over the waist and flared over the hips into a full skirt. This could have been a skirt of a woman’s dress or the skirt of a man’s coat.[7]

An “hourglass” figure, then, is not an eternally feminine symbol, nor do ruffles, flowered fabrics, or satins belong exclusively to women. The first task in any study is to distinguish between design motifs that unite men and women in a given period and those that distinguish one sex from another. Although the contrast between the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries is more easily illustrated with women’s portraits than with men’s, the basic differences do in fact cross gender lines. Thomas Smith’s portrait of an unknown gentleman, circa 1680 (fig. 5), is every bit as fussy with surface details as that of Elizabeth Wensley, whereas in portraits by Blackburn or Copley, men as well as women, shimmer with light.

Careful reading of male and female clothing within the same period can, however, yield gender distinctions. The paintings of John Singleton Copley provide a rich field for such an analysis. Because Copley was interested in furniture, his paintings also help us connect chairs and tables with gender. In the eighteenth century, bare forearms were strongly associated with women, shapely legs with men. Significantly, in Copley’s paintings women’s arms were often displayed against polished wood, as in the painting of Dorothy Skinner (fig. 4). Although men’s hands (though never their arms) are sometimes reflected in polished tables, men usually grasp some object (fig. 6)— a paper, book, tool, or in one case a squirrel. Only with women does Copley emphasize the flesh alone. Here he is employing an aesthetic principle enunciated by the eighteenth-century philosopher Edmund Burke:

I do not now recollect any thing beautiful that is not smooth. In trees and flowers, smooth leaves are beautiful; smooth slopes of earth in gardens; smooth steams in the landscape; smooth coats of birds and beasts in animal beauties; in fine women, smooth skins; and in several sorts of ornamental furniture, smooth and polished surfaces.[8]

Copley reflects one kind of smoothness in the other.

Artists in other times and places might enjoy the play of light and shadow on a sun-freckled or mosquito-bitten arm or a fruit-stained or grease-splattered table. The gestures of Copley’s sitters—women resting on the surfaces of their polished tables, men fluttering their important papers—capture gender codes that might not be visible in other ways. In most of the female portraits, the tables are purely ornamental, dazzling mirrors for displaying female arms. In the portraits of men (and in the single case of Mrs. Thomas Mifflin who is working at a table loom), tables are settings for displaying if not for doing work. If one cannot imagine Paul Revere actually engraving a tea pot on the table pictured in Copley’s portrait, the surface nevertheless made a fine place for displaying his work and tools. More commonly, Copley’s gentlemen use tables for writing.[9] There is no difference in form between the pedestal table used by one of Copley’s scholars (fig. 7) and the table portrayed in a contemporary cartoon of an old maid at tea (fig. 8). The polished table in Dorothy Skinner’s portrait is neither a woman’s table nor a man’s table, neither a tea table nor a writing table, but an all-purpose surface for sustaining and displaying beautiful things—smooth arms, polished tools, sleek animals, and perhaps silken prose (fig. 4).

In Copley’s iconography, pen and paper are simultaneously marks of gentility and of industry—but only for males. Although nearly a quarter of his men are portrayed with loose papers, or account books, fewer than 2 percent of his women are shown with any kind of paper, including loose pages that might be letters. None of his women is pictured with a pen. This omission is surprising given the importance of letter-writing in the education of eighteenth-century women. Copley frequently pictured women with books, but apparently even among his elite clientele, quill and ink were still too closely associated with masculinity to fit comfortably into a female portrait, even into a portrait of a woman as literate and literary as Sarah Prince. Sarah holds her book in a vaporous landscape, while her husband, Moses Gill, receipt in hand, leans one elbow on what appears to be a merchant’s desk.[10] In comparison with Copley’s paintings, the contemporary engraving of Phillis Wheatley, quill in hand, seems even more revolutionary. Modestly (but tastefully) dressed in the garb of a gentlewoman’s maid, Phillis sits in a late baroque side chair, papers spread on what appears to be a pillar-and-claw tea table (judging from the shape of the top), about to compose her next line of poetry (fig. 9).

A table became a man’s or a woman’s table by virtue of its use. For the women in Copley’s portraits, a table was a place for quiet reflection and perhaps conversation. In a few paintings, female sitters finger fruit or flowers,traditional emblems of beauty and fertility, though in some of Copley’s paintings fruit may represent horticultural achievement as well. Mrs. Ezekiel Goldthwait, for example, rests one plump hand on a bowl of fruit while the other rests quietly on the polished surface of her table. Her bare arm is central to the composition, its reflection completing a circle of light from fruit to wood (fig. 10). In contrast, Mr. Goldthwait turns away from the table, his arms covered by his austere coat, his hands leading the eye downward from the stile of his chair to his smoothly stockinged leg (fig. 11). For Copley, men’s legs were as important as the bare arms of women.

To a twentieth-century eye, the graceful curves of a cabriole chair leg might appear “feminine,” a massive chest with stubby bracket feet, “masculine.” In the colonial world, the gender attributions were probably reversed. In both the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, a well-formed leg was one of the defining attributes of an upper-class male. Working men and sailors might disguise their calves in pantaloons, women in skirts, but elite males exposed and embellished their lower limbs. Here, too, furniture and fashion changed together. The decorative pulls on a baroque high chest (fig. 12) mirror the knobby ruffles and bows on the legs of a late-seventeenth-century male (fig. 13), whereas the smooth silk stockings and tightly fitting shoes of eighteenth-century gentlemen reflect furniture styles of that time. In his rather awkward, full-length portrait of Thomas Hancock, Copley acknowledged that relationship (fig. 14). Here the white-stockinged legs of the sober merchant are flanked by the wood and gilt legs of high-style furniture, the velvet-covered armchair appealingly empty, the gentleman’s outstretched arm inviting a real-life lady to take her place beside the fanciful nymph who grows, mermaid-like, out of the curving legs of the table. The same table—and the same rhyme with a man’s leg—reappears in Copley’s better-known portrait of Jeremiah Lee of Marblehead.

For a commercially successful artist like Copley, men’s legs were a bit of a problem. Few Boston patrons were willing to commission full-length portraits. In three-quarter-length poses, particularly when the subject was seated, men’s appendages could appear awkwardly cut-off at the ankles. In dozens of portraits painted between 1758 and 1774, Copley experimented with various devises to integrate silk-stockinged calves—sans feet—into his images of aspiring males. The Ezekiel Goldthwait portrait represents two of his most commonly used solutions. In the Goldthwait painting, as in those of John Gardiner, Daniel Rogers, and Isaac Royall, the man’s leg, highlighted in white silk, outlines the shape of the chair.[11] The Daniel Rogers portrait is particularly striking in this regard. Copley must have experimented for some time to achieve the marvelous blending of the subject and the chair. Rogers is seated at cross-angles to the chair, his right leg obscured by drapery, his left extending and completing both the back support and the rear leg (fig. 15).

The Ezekiel Goldthwait painting also exemplifies Copley’s use of quill pens as a rhyme for men’s legs. Goldthwait grasps his quill firmly between his thumb and index finger, establishing a vertical line that parallels the fold of his wig, the buttoned flap of his waistcoat, and the barely glimpsed stile of his chair. The point of the pen leads the eye ever so subtly to the bended row of brass nails that completes the edge of the chair. In his portraits of Issac Smith, John Erving, and Thomas Bolston, Copley used quills in similar ways.[12] In the Isaac Smith portrait, for example, the quill remains in its stand, tilted at the exact angle of Smith’s leg; the brass buttons of the man’s breeches and the brass nails of his chair bend in opposite directions.

Copley’s eye captured some of the gestures that distinguished women from men in eighteenth-century Boston, but gender codes are best conveyed in action. Portraits freeze people in time and space. If we could see more motion, actually observe these dignified gentlemen and ladies bowing, dancing, eating, working, or laughing, our conclusions about the period might change. Did the presence of high-style furniture inhibit or structure motion? Did a polished table presume an arm in repose? Did a lady reveal some part of her leg as she lifted her skirt to ascend a stair, perform a minuet, or cross a muddy street? Did a gentleman—or for that matter a prosperous mechanic like Paul Revere—ever roll his sleeves to the elbow? It seems inconceivable that men worked with their loose shirts falling to the wrists, yet engravings of street riots, like genteel portraits, show men’s forearms covered and their legs revealed. Legs are so thoroughly male in the visual grammar of the era that it is difficult not to see the carefully turned legs of period furniture as a celebration, if only subliminally, of the male human form.

If the Portsmouth furniture show provoked me to meditate on the symbolic meanings of arms and legs, the Hadley chest exhibition returned me to the material base of social life in eighteenth-century New England. Again the issue of gender rose to the forefront. I was not the only person intrigued by the remarkable Hannah Barnard cupboard (fig. 16). The curator of the exhibit purposefully “set up the other chests like so many little pews leading up to the cupboard, which sat there like a kind of throne or altar.” One observer saw a “proto-feminist statement” in Hannah’s cupboard. In this “rigidly patriarchal age,” he reasoned, only a rebellious woman would emblazon her name on a cupboard. Another suggested, more mildly, that Hannah’s cupboard must have been a gift from her future husband, “a valentine in furniture.”[13] As the only specialist in women’s history represented on the program, I felt compelled to explain Hannah’s cupboard. I began by asking furniture scholars how unusual it was for names—particularly women’s names—to appear on furniture. I soon learned that Hannah’s cupboard was closely associated with a large group of chests made in the Connecticut River Valley between the 1680s and about 1730.

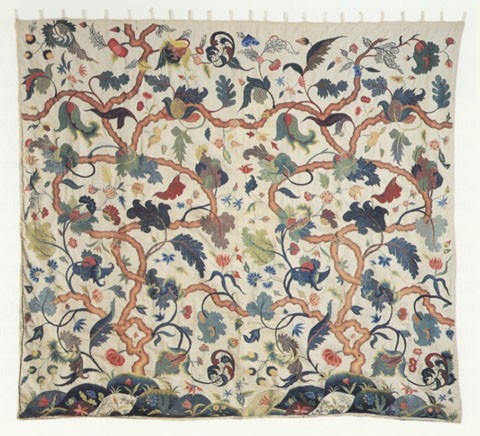

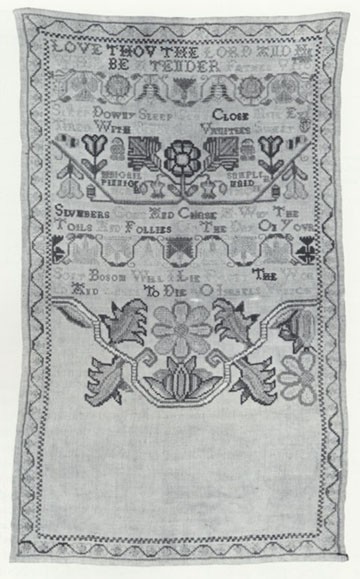

The more than sixteen variants of the so-called “Hadley chest” share certain design elements—undulating vines, tulip and leaf motifs, pinwheels, and letters with curling tendrils. Most are marked with initials; at least six have complete names, all of women.[14] The floral ornamentation on the Hadley cupboards and chests reinforces the notion that they were “dower” or “marriage” furniture. Most are exuberantly carved or painted, though the motifs they employ vary widely. The so-called “SH” chest (fig. 17), for example, employs design elements present in a seventeenth-century bed hanging at the Wadsworth Atheneum (fig. 18). The very different style of the “MS” chest with drawers (fig. 19), made about the same time as the Hannah Barnard cupboard, echoes design elements widely used in samplers (figs. 20, 21).

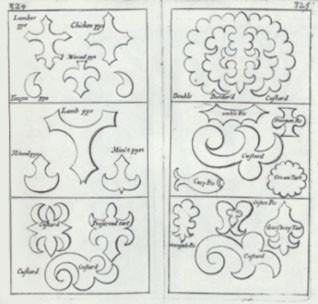

The association with embroideries is hardly surprising. We have already noted common elements in furniture and clothing within a given period. This connection is merely another example of the well-known unity of decorative arts. Furniture reflects architecture, gravestones, silver, and even pie crust vents from the same period (fig. 22). Seen in isolation, no motif would mark a piece of furniture as a “woman’s” cupboard or chest. It is the combination of decoration and form with the presence of women’s names that leads to that conclusion. Though almost all of the identified initials on Hadley chests (and all of the full names) belonged to women, plainer board chests from the same time and place were owned by men.[15] The terms “marriage cupboard” or “dower chest” are modern, but they point in the right direction. The Hannah Barnard cupboard marks a transition point in a woman’s life, the stage at which she left one household to join another.

Cupboards and chests, like the textiles, ceramics, and silver they were designed to store, belonged to that category of property known as “moveables.” Moveables were associated both with the marriage portions of daughters and with bequests granted to widows. In the Connecticut River Valley, as in most of the western world, “real” property or land followed the male line of inheritance. Women typically inherited portable forms of property—cooking equipment, animals, bed linens, and furniture. In such a system, women themselves became “moveables.” When Hannah Barnard married John Marsh in 1715, she changed her name, shifting her allegiance from one male-headed household to another; but her cupboard, like the marked sheets, pillow beers, and silver spoons she brought to the marriage, carried her maiden name.[16]

Although initials were more commonly used than full names, household goods preserved a woman’s birth name even as she lost it in marriage. The eighteenth-century meaning of such a practice is suggested in the memoir of a Vermont woman, Mary Palmer Tyler. Shortly after she and Royall Tyler were married, he purchased a dozen small and three large spoons and had them marked with her maiden initials “MP.” Since they were already married, it is surprising that he did not have the spoons marked “MT” for Mary Palmer Tyler or even “RTM” for Royall and Mary Tyler, as was sometimes done on linen, silver, pottery, and occasionally even furniture. To Mary, his selection of her maiden initials demonstrated his sensitivity to her parent’s precarious circumstances. “[H]e knew I could not purchase them,” she wrote, “and he wished to make it appear that my parents did so.” Hannah Barnard’s flamboyant cupboard not only preserved her personal identity, it ratified her connection with her family of origin. Significantly, a mammoth table stone in Hadley cemetery lists Hannah with her father rather than with her husband. Although this circumstance was probably a consequence both of Hannah’s early death and the remarriage and subsequent death of her spouse, there seems to be no question that she continued to be identified as a “Barnard” even after she became a “Marsh.”[17]

Still, the visibility of Hannah’s name on her cupboard speaks of more than family pride. Many women preserved their maiden identities by embroidering their initials onto linens or bed coverings. Few women emblazoned their full names on so visible a household object as a cupboard. In fact, the Barnard family seems to have nourished female independence as well as family pride. Hannah was named for her grandmother and for her paternal aunt, Hannah Barnard Westcar Beamon, a childless woman, twice married and twice widowed, who appears several times in Hadley and Deerfield records. In 1673 the aunt was acquitted of wearing silk contrary to law. In January 1677 she was again presented “for wearing silk in a flaunting garb to the great offence of several sober persons in Hadley.” Her first husband had died two years before, leaving an estate of £431. In 1694, now remarried and a schoolmistress in Deerfield, she rescued the town’s children from a French and Indian attack by rushing them to the fort. She died in Deerfield in 1725 in sober respectability, leaving her considerable estate to the town for the support of schools. It is not hard to imagine the niece of such a woman emblazoning her name on a cupboard. In fact, something about the arrangement of letters on the cupboard suggests a primer or a slate. Could Hannah also have been a teacher, like her aunt? If her recorded birthdate is correct, she was thirty-one years old when she married John Marsh, a widower five years her senior. (Hannah’s older sister had married at eighteen.)[18]

Hannah died in 1716, leaving an infant daughter, Abigail. Her husband married a third time, fathered several more children, then died in 1725. His will makes clear what the cupboard only suggests, that certain objects in the household were marked, literally or figuratively, with female lineages. Marsh promised his only son, a child of his third marriage, all of his real estate, reserving moveable property for his daughters. Hannah’s child was to receive £120, “to be paid in what was her own Mothers,” plus “her Mothers Wearing Cloaths . . . to be given her free.” The inventory contains separate lists for each of the wives. Although Marsh, as head of the household, controlled all this property, he understood its origins. The moveables each wife brought to the marriage formed the core of her own daughters’ inheritance. Hannah’s daughter Abigail grew up in Hadley, married Waitstill Hastings in 1736, and in 1742 had a daughter whom she named, not just Hannah, but Hannah Barnard Hastings.[19] Not surprisingly, this fourth Hannah Barnard eventually inherited the cupboard.

In the Marsh family, demographic accidents—the early deaths of two wives, the husband’s own premature demise—exposed female lineages. More commonly, the formulaic dispersal of moveables, as in “one-third of my household goods,” concealed the female labor that created and maintained those goods and the social customs, if not the female voices, that directed their disposal. Because daughters customarily received their portions at marriage rather than at the death of their father, wills and inventories actually mask much of what moved from one generation to another. Land can be traced in deeds, but moveables, by definition, flowed outside the constraints of law. For this reason, object-centered research is most useful. Probate records can tell us what sorts of objects people possessed at any one time and what kinds of things decedents willed to their children, but only detailed histories of surviving objects can tell us how certain moveables were transmitted—or lost—over time.

Establishing provenance is so basic to decorative arts scholarship that researchers may have overlooked its potential as social history. The range of possibilities—as well as the difficulties—are suggested in catalogues and books such as Brock Jobe’s Portsmouth Furniture: Masterworks from the New Hampshire Seacoast. Provenances range from a despairing “early history unknown” to complete genealogies stretching through centuries. Many of these document lineal descent from mother to daughter, even though, until the middle of the nineteenth century, husbands legally owned and controlled all of the property their wives brought to marriage. Thus, a secretary-and-bookcase by Langly Boardman, stamped on the bottom of every drawer with the name “Dr Dwight,” actually came to Susannah Dwight as part of her inheritance from her father, Thomas Thompson. It then descended to Susannah’s daughter, Martha Rundlet, who in turn gave it to her daughter, who gave it to a sister. Dwight’s stamp survives as an ironic commentary on male ownership of what was in fact female property.[20]

From the standpoint of social history, the most frustrating entries simply say, “Descended in the ______ Family.” Since families survive only by integrating new blood in each generation, one can never be certain what such an entry means. After all, Hannah Barnard’s cupboard descended through the Marsh family and the Hastings family while retaining the Barnard name. Because of the male bias of western naming practices, unbroken descent from father to son is easily traced, particularly when “moveables” become attached to houses. Thus, the magnificent neoclassical settee illustrated in figure 23 passed from father to son through three generations while remaining in the entry hall of the Pierce mansion. In contrast, the impressive Sherburne high chest passed by a circuitous route to the Penhallow and Swan families, eventually returning to the Warner house (figs. 24, 25).[21]

The history of the Sherburne chest reinforces a point made earlier in this paper about the importance in conducting research of moving between documents and objects. Until research began for the Portsmouth furniture book, the former owner of the chest did not know the meaning of the initials “I*S” on the tympanum (fig. 26). Three years later, he stumbled across an answer in an antiquarian bookstore. A 1902 furniture book identified “I*S” as John Sherburne, a Portsmouth mariner who died at sea in 1735. Genealogical research sustained the attribution. Sherburne was indeed a direct ancestor of the Penhallows, who owned both the Warner house and the chest in 1902. In the intervening century, however, John Sherburne’s marvelous highboy suffered a peculiar fate. As the 1902 history explained, “The legs of the chest were ruthlessly sawed off many years ago, in order that it might stand in a low-ceilinged room.” (The current owner had the feet restored in the early 1950s.)[22]

The last private owner believes that Elizabeth Warner Sherburne moved the highboy to the Warner house when she inherited it from her uncle in 1814. If so, it must have left the house again, because the 1902 history says, “it is only in comparatively recent years that it has belonged to the branch of the family now owning the Warner house.” Again the phrase “the family” is confusing. Was the author referring to Sherburnes, Penhallows, or both? Did one of Elizabeth Warner Sherburne’s grandchildren (there were six) take the chest after her death in 1844, cutting off the feet to accommodate a smaller house? If so, the chest with its outraged limbs returned to the Warner house during the tenure of Elizabeth Warner Pitts Sherburne Penhallow, who died in 1909 and who must have been the informant for the 1902 history. The mystery of the missing feet is of more than antiquarian interest. It is evidence not only of the shifting value of “old time” furniture as it passed from old to old-fashioned, to antique, but of the economic imperatives that shape history and memory. A high chest required a high-ceilinged room. At least one of John Sherburne’s descendants must have experienced downward mobility.[23]

The eighteenth-century history of the chest is obscure, though there are tantalizing hints in the family history and on the chest itself. The date on the tympanum below the center finial has puzzled researchers, since it doesn’t seem to refer to any known life event. The heart suggests a marriage, but according to local records, John Sherburne and Eleanor Mendum were married in 1731, not 1733.[24] Perhaps the baroque shell inlay on the large top drawer (fig. 27) signifies another, now lost, event in the life of its first owner—the birth of a first child named John (the couple’s only recorded child is Nathaniel, born just before or after his father’s death) or even the completion of a successful voyage or an ascendancy from “mariner’ to “captain.” There is nothing particularly personal about the imagery, however. The whimsical cherubs and Doric columns flanking the shell and the compass stars with faces on the case sides are distinctive interpretations of relatively generic, eighteenth-century ornaments, though the imagery is appropriate to an aspiring provincial class (figs. 26–28). The materials from which the chest is constructed—pine, walnut, burled maple—demonstrate the material base of Portsmouth’s rising gentility. Surveyors’ compasses as well as mariners’ compasses did indeed lay the foundations of Portsmouth—and Sherburne—wealth.

As James Garvin has written, “The period from 1725 to 1750 witnessed a dramatic mercantile expansion that bore fruit by mid century in a new generation of grand houses, in a notable increase in the display of personal wealth among the oligarchy, and in social stratification which strengthened the status of those few families that had seized wealth earlier in the century.” John and Eleanor Sherburne’s kin were among those families. Eleanor’s father, Nathaniel Mendum, rose from “joiner” to “shopkeeper” to “Esquire” during this era. John’s father, Joseph Sherburne, became a member of the King’s Council in 1734 and a justice of the Supreme Court in 1739. About 1730 he added a room (possibly a shop) to the Puddle Dock house he had accepted from his mother as part of the settlement of his father’s estate. Before the decade was out, he had completely gutted the old house, adding a proper Georgian stairway in the space once held by the old chimney and creating neoclassical orders from the then-outmoded windows and doors.[25]

The spate of building that began in 1729 with the purchase of an additional strip of land adjoining the back garden may indeed have been motivated by the coming-of-age of the Sherburne children. John’s marriage in 1731 and Joseph’s in 1734 marked a new stage in the family life cycle as one generation aged and the other prepared to take its place. John’s death in 1735 interrupted but did not halt this process. His wife soon married Samuel Marshall, who operated a pottery just across Horse Lane from 1736 until his death in 1745. (In fact, waste pieces from the Marshall pottery were found in the trench under the Sherburne addition when it was excavated in the 1980s.)

There is no way of knowing where young Nathaniel Sherburne or his father’s chest spent the 1730s and 1740s. Presumably the child and the chest were both cared for in the Marshall house or the neighboring Sherburne house. Joseph Sherburne’s 1745 inventory does, in fact, list a “Chest of Draws” that may have been a high chest.[26] It is conceivable that young Nathaniel, the oldest son of an oldest son, was raised in his grandfather’s house. By 1759, Nathaniel had inherited that house, receiving his father’s double portion as oldest son. He lived there until his death in 1805—with or without the Sherburne high chest. The family genealogist believes the chest passed from Eleanor Mendum to her son Nathaniel at her death. Perhaps it did, but since Nathaniel outlived his mother by only a year, it is also possible the chest bypassed him entirely, going directly from one John Sherburne, via his widow, to another.

Eleanor Mendum Sherburne Marshall Shackford, having survived three husbands, died in Portsmouth on February 4, 1804, at the age of ninety. Ten years before, she had witnessed what must have been a striking replay of her own life history. Her grandson, Nathaniel Sherburne Jr., a mariner, died of yellow fever a year after his marriage to Elizabeth Warner, leaving a son. Like Hannah Barnard Hastings, this little boy seems to have inherited both a chest and a name. He was christened John Nathaniel Sherburne. Perhaps he received the chest from his grandfather. It is just as likely that his great-grandmother bequeathed it directly to his mother—or to him (he was ten years old when she died). He became the father of the Elizabeth Sherburne who married Pearce Penhallow in 1845, connecting the Sherburne chest with the Penhallow family. By the twentieth century, the Sherburne association might have been lost entirely if it hadn’t been for that mysterious, heart-shaped inscription on the chest. The Sherburne high chest, like the Barnard cupboard, helps us understand how objects preserve lineages through time.[27]

Furniture scholars have adopted part of the vocabulary of social history. They now write of “ethnicity” as well as “taste,” “social economy” as well as “aesthetics.” Inspired by colleagues in other fields, they are likely to speak of networks as well as masterworks. But there is more to be done. To place furniture in a larger context requires the recovery of the unspoken assumptions that animated ordinary life. Furniture speaks about gender, family, literacy, gentility, and even mortality. It teaches us to look at the way objects are used, reused, inherited, and remembered, as well as at how they are made. Prudence Punderson’s tiny silk embroidery, “The First, Second, and Last Scenes of Mortality” (fig. 29), brings together many of these themes.

Prudence Punderson was born in Preston, Connecticut, on July 28, 1758, the oldest of eight children born to Prudence Geer and Ebenezer Punderson. Her father was a merchant and (later) a Loyalist. Her mother, too, had a genteel upbringing, as evidenced by Prudence Greer’s fine crewelwork embroidery now at the Connecticut Historical Society.[28] Prudence Punderson’s own medium was silk. Unlike most eighteenth-century embroiderers, she seems to have worked from life rather than from English models. Her remarkable embroidery, one of the few surviving representations of a prosperous New England drawing room, is filled with little-known details about eighteenth-century households, from the fringed rug on the floor to the slave child rocking the cradle. And it has a great deal to say about furniture.

Prudence’s embroideries of a falling leaf table, a pillar-and-claw tea table, a crested looking glass, and a rococo chair are punctiliously specific. Her family, in fact, owned and preserved the very items commemorated in the picture, which is, on the one hand, a remarkably realistic portrayal of an actual room and a stylized representation of the waxing and waning of human life. While the diminutive slave rocks a child not much smaller than herself, a young lady seated at a polished table works at her embroidery, a pewter or silver ink stand beside her. To her right is a shrouded mirror marking the passage of the “P.P.,” whose initials mark the coffin. Significantly, the tea table holds implements for writing as well as for needlework. Pewter ink stands, like those on the table, survive in Connecticut collections.

In Prudence’s picture, the tea table sustains work; the long table displays death; but it is the empty chair that signifies loss. If the child, the young woman, and the coffined corpse represent Prudence in the first, second, and last scenes of her life, the chair represents the male partner who might have arrived had death not cut short the journey. One scholar believes that the embroidered picture-within-a-picture above the slave child’s head represents Mary Queen of Scots summoned by the executioner. If so, this was probably not a random choice. In November 1778, Prudence Punderson fled Connecticut with her mother and sisters. Her father, Ebenezer Punderson, was already in exile on Long Island, serving as commissary for the King’s Troops. An undated manuscript in Prudence’s hands suggests that she had an offer of marriage at the time but chose instead to join her family. As she told her unnamed friend, “from the tumultuous jarring times of Civil War I think may be raised many objections against settling for Life & my Ill state of Health which look but too probably to end only with my Breath makes me unwilling to bestow on my Friend or go to my Paren[t]s under their present situation such a helpless Burthen.”[29]

Her embroidery is undated, but if it was created during this period, the meaning is less generic than has commonly been supposed. Prudence had reason to be thinking both about death and politics. The furniture was gathered, the young lady was educated in all the arts of gentility, but death and war, not a lover, knocked at her door.[30] The fine furniture in the embroidery adds poignancy to the representation. Furniture, embroidered textiles, and sometimes slaves were part of the “moveables” prosperous young gentlewomen brought to marriage. The empty chair represents, then, not only the accouterments of a genteel household but the missing “friend” who might give purpose to her accumulated goods and gifts. The Prudence Punderson of the picture will never change her name. Her goods will never form the core of a new household because her life is about to be interrupted by death.

Punderson did in fact die young, though not before marrying her cousin, Timothy Rossiter, and giving birth to a daughter, Sophia. Sophia’s birth transformed the linear narrative into a circular tale. As Prudence died, her infant picked up the story again, the narrative moving from the coffin back to the cradle as well as from cradle to coffin. Superimposed on the ancient theme of mutability was a new motif. Things—tables, chairs, cradles, curtains, mirrors, rugs, and embroidered pictures, the dross of the world that moralists condemned and that the dying can never take with them—conferred their own immortality. Prudence’s needle celebrates the material objects that were eventually passed on to her child, to her sibling’s children, and to their children’s children, coming in time to the Connecticut Historical Society as monuments to her own short life.

Prudence Punderson’s realism preserved another detail too often overlooked in New England social history as well as in decorative arts scholarship. Slaves were frequently part of the households that generated the magnificent furniture celebrated in publications like this one. Hannah Barnard’s husband, John Marsh, owned an “Indian [perhaps West Indian] Boy Sippey about 14 Years Old” at the time of his death in 1725. Joseph Sherburne owned “1 Negro Man” valued at £200 and “1 Ditto Woman” valued at £50 when his inventory was taken in 1745. The child rocking the cradle may be the “wench Jenny” mentioned in Ebenezer Punderson’s will. Seldom do these persons appear in eighteenth-century portraits, but Jenny, Sippey, and their kin were part of a social order that made high-style furniture, damask dressing gowns, and gilded mirrors possible.

Prudence Punderson’s embroidery is an imperfect mirror of her world, but in its focus on the female life cycle, its integration of furniture and textiles, and its acknowledgment of the inequality that underlay genteel households, it is more complete than much of what has been written since. By placing eighteenth-century furniture in context, it highlights new directions in social history.

See the essay by Edward S. Cooke, Jr., in this volume.

Anatomical terms from Martin Eli Weil, “A Cabinetmaker’s Price Book,” in American Furniture and Its Makers Winterthur Portfolio, vol. 13, edited by Ian M. G. Quimby (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1979), pp. 80–192; “Thomas Elfe Day Book, 1768–1775,” bound compilation of transcripts published in The South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine, photocopies at the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Winston-Salem, N.C.; Brock Jobe, ed., Portsmouth Furniture: Masterworks from the New Hampshire Seacoast (Boston: Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, 1992); Brock Jobe, “An Introduction to Portsmouth Furniture of the Mid-Eighteenth Century,” in New England Furniture, Essays in Memory of Benno Forman, edited by Brock Jobe (Boston: Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, 1987), pp. 163–195.

Claudia Brush Kidwell, “Gender Symbols or Fashionable Details?” in Kidwell and Steele, eds., Men and Women, p. 126.

Prown, Copley, 1:figs. 80, 141, 158, 272. Although Copley places books and papers on many kinds of surfaces, more of his male subjects sit at tables than at desks.

On Sarah Prince as correspondent, see Carol Karlsen and Laurie Crumpacker, “Introduction,” The Journal of Esther Edwards Burr (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1984).