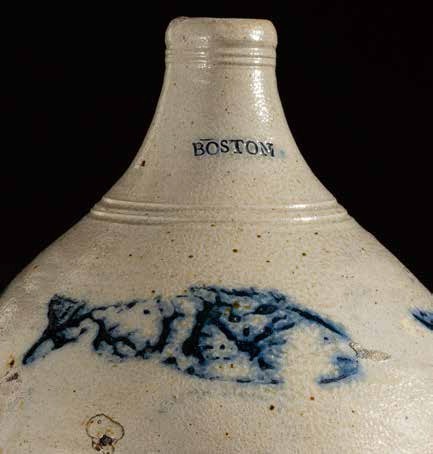

Detail of the stamp from the jar/jug illustrated in figure 11 used by William Little, Jonathan Fenton, and Frederick Carpenter, Boston, ca. 1793–1798.

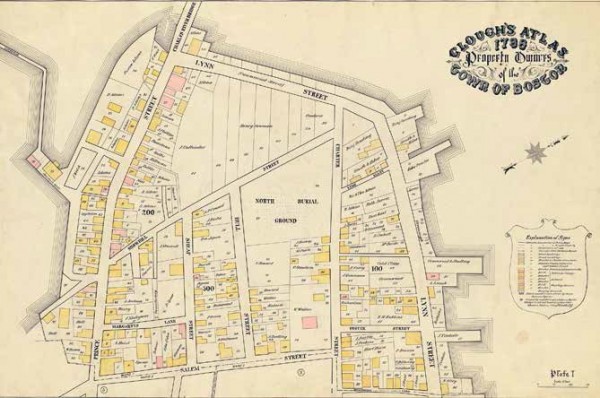

From Clough’s Atlas 1798 Property Owners of the Town of Boston, pl. 1. (Courtesy, Massachusetts Historical Society.) This is the first of twelve plates from an uncompleted atlas of maps prepared by Samuel Chester Clough, available online at https://www.masshist.org/online/massmaps/clough-plt-overviewer.php [image 1]. Jonathan Fenton’s pottery is located on Lynn Street.

Advertisement for the opening of Jonathan Fenton’s stoneware manufactory, Columbian Centinal, August 14, 1793.

Jug, Westerwald, Germany, ca. 1740–1760. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, The Reeves Collection, Washington and Lee University; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Jug, probably London, England, ca. 1740–1760. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

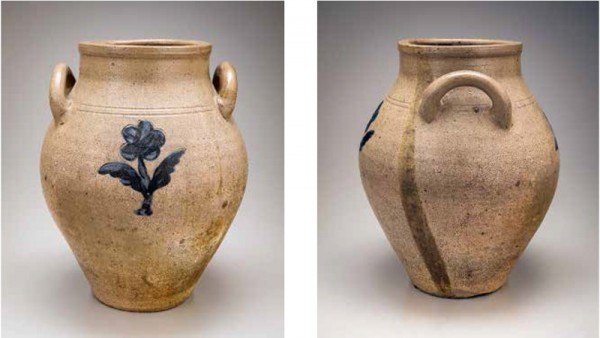

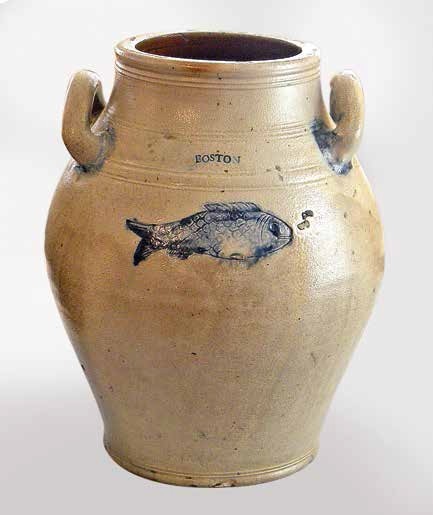

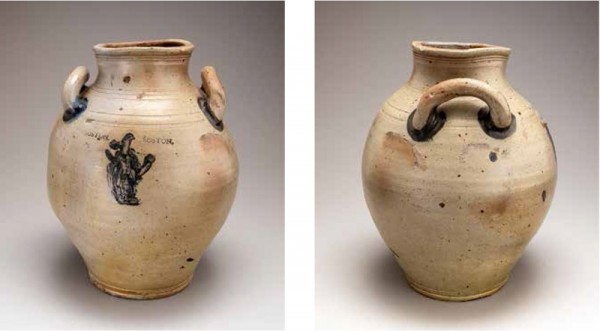

Jar, Jonathan Fenton, Boston, Massachusetts, 1793–1796. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 12 7/8". (William H. Chapman Collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Detail of the flower stamped on the jar illustrated in fig. 6.

Churn, William States Pottery, Stonington, Connecticut, ca. 1811. Salt‑glazed stoneware. H. 11". (William H. Chapman Collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Detail of the flower stamped on the churn illustrated in fig. 8.

Jar, Jonathan Fenton, Boston, Massachusetts, 1793–1796. Salt‑glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Peter Schriber.)

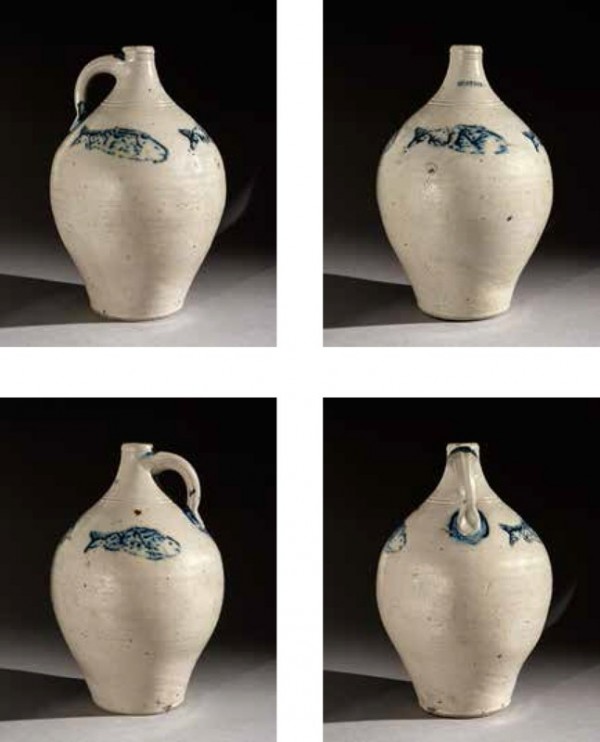

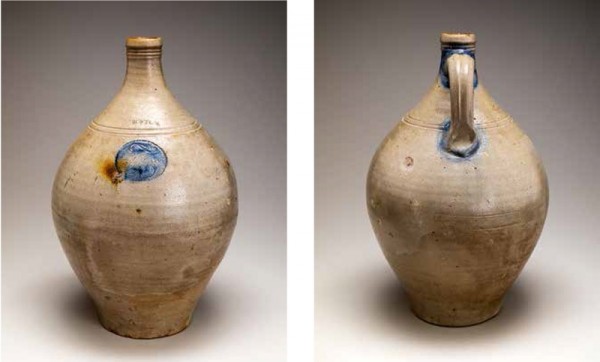

Jug, Jonathan Fenton, Boston, Massachusetts, 1793–1796. Salt‑glazed stoneware. H. 14 1/4". (Colonial Williamsburg; photo, Jason B. Copes.)

Detail of the fish stamped on the jug illustrated in fig. 11.

Jug , Jonathan Fenton, Boston, Massachusetts, 1793–1796. Salt‑glazed stoneware. H. 14". (Courtesy, Crocker Farm.)

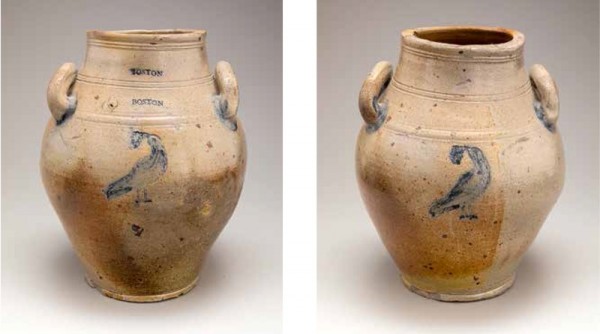

Jar, Jonathan Fenton, Boston, Massachusetts, 1793–1796. Salt‑glazed stoneware. H. 14". (William H. Chapman Collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

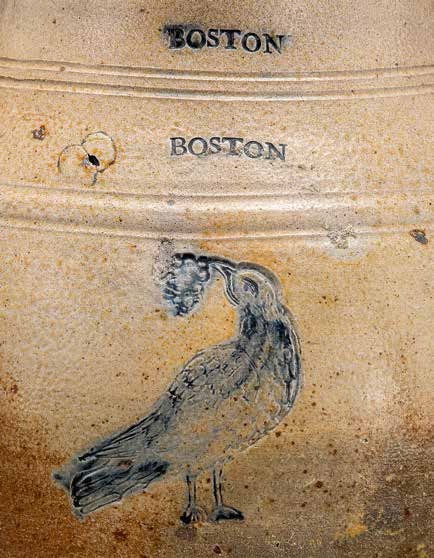

Detail of the bird stamped on the jar illustrated in fig. 14.

Jar, Jonathan Fenton, Boston, Massachusetts, 1793–1796. Salt‑glazed stoneware. H. 13 3/4". (William H. Chapman Collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Detail of the Native American figure stamped on the jar illustrated in fig. 16.

Jug, Jonathan Fenton, Boston, Massachusetts, 1793–1796. Salt‑glazed stoneware. H. 12 3/4". (William H. Chapman Collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Detail of the entwined initials “J. F.” stamped on the jug illustrated in fig. 18.

Jug, Jonathan Fenton, Boston, Massachusetts, 1793–1796. Salt‑glazed stoneware. H. 15 1/2". (William H. Chapman Collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Detail of the entwined initials “J. F.” stamped on the jug illustrated in fig. 20.

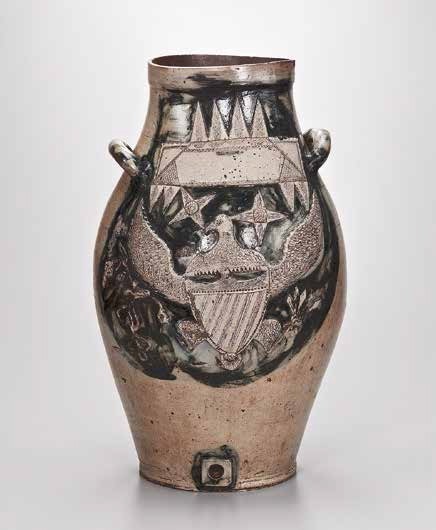

Cooler, attributed to Jonathan Fenton, Boston, Massachusetts, 1793–1796. Salt‑glazed stoneware. H. 24 3/4". (Courtesy, Collection of Robert A. Ellison Jr.; photo, Robert A. Ellison Jr. Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Detail of the cartouche with the initials “R.H.W.” impressed on the cooler illustrated in fig. 23.

The distinctive stoneware that was made in Boston, Massachusetts, during the late eighteenth century was not necessarily the product of chance (fig. 1). Instead, it may have been part of a masterful marketing campaign, the likes of which had never before been used within the American stoneware market.

Research suggests that a pivotal figure in this endeavor was William Little, a wealthy Boston merchant who saw an opportunity to sell locally manufactured stoneware to a customer base that was resentful of Britain’s efforts to undermine America’s economy. Little provided the financial backing for Jonathan Fenton’s pottery in the 1790s, and he may have made another contribution that was equally significant: conceiving the designs that are unique to stoneware made in Boston during that period. Having lived in Boston since the mid-1780s, Little was well aware of how the political winds blew in a town that had never been reticent about expressing its opinion of Great Britain. Furthermore, as a prosperous merchant and town selectman, he was a member of the town’s ruling class and had considerable influence in Boston’s business affairs.

William Little was born in 1749 in Lebanon, Connecticut, the eldest of William and Sybil (née Metcalf) Little’s eleven children. After receiving a Bachelor of Arts degree from Yale, he went on to receive a Master of Arts degree in 1780.[1] While still an undergraduate, he was appointed to the position of Issuing Commissary of Supplies and Refreshments for the Connecticut troops. His duties included purchasing wagons and horses, supplying the troops with food and clothing, and maintaining an account of all disbursements, expenses, and income.[2] Little joined the Freemasons during this time, and shared the responsibility of inspecting and maintaining the financial accounts of his lodge.[3]

Records show that Little was still living in Connecticut in October 1785, but by July 1786 he had settled in Boston, where he was awarded an honorary Master of Arts degree from Harvard upon the recommendation of Yale president Ezra Stiles.[4] By 1787 he had opened a store on State Street, where he put the skills that he had learned as Issuing Commissary and Mason to good use.

In addition to offering his customers local wares, Little sold a wide variety of English goods.[5] He also acted as a broker, paying cash for final settlements and Continental Loan Office certificates.[6] Four years after settling in Boston, his business had expanded to two stores and the value of his personal estate had grown from $600 to $2,250.[7] He joined the ranks of wealthy Boston merchants and became an influential member of the mercantile community.

In 1790 Little married Frances Boyd, the daughter of James Boyd.[8] Two years later, he and his family moved into the North End mansion that had once been owned by Thomas Hutchinson, the last royal governor of Massachusetts.[9] A year later, in 1791, Little was elected to his first term as town selectman, a position he held for most of that decade.[10] Although he imported English goods in the course of his business, he was a proponent of the nation’s fledgling manufactures and actively campaigned against Britain’s dominance. He also acted as an agent for the French Consulate, auctioning off the contents of British ships captured by French privateers.[11]

Boston’s merchant class ruled both politics and society in the eighteenth century, and, following long-standing tradition, they met each weekday to “talk shop, ships, and politics.”[12] There was an increasing awareness among this group that domestic manufactures needed to be encouraged in order to break Britain’s hold on the nation’s economy and secure national independence. After the Revolution, resentment against Britain was strong as it attempted to regain its hold on the American market by flooding it with inexpensive goods. This resentment was particularly intense in maritime-dependent Boston, because Britain refused to permit trade reciprocity between its own ports and those in the U.S., which forced Boston’s merchants to seek out new markets.[13]

Stoneware was one of Boston’s most common imports, both before and after the Revolution, because the clay for stoneware, unlike that for redware, was unavailable locally and stoneware kilns had to be larger and burn hotter than redware kilns. Since procuring the clay and building a more sophisticated kiln required a substantial capital investment, stoneware potters often looked to non-potters to provide the necessary financial backing. Consequently, in order to remain financially viable a stoneware potter in the Boston area would have to make more items and distribute them to a broader market than redware potters.

The manufacture of stoneware in the Boston area had not been attempted since the failure of the Parker-Symmes pottery in the 1740s, largely due to the expense of importing clay. The cost of bringing clay to Boston overshadowed any potential for profit. Imported stoneware, by contrast, was inexpensive, and eighteenth-century Boston newspapers are filled with advertisements for stoneware from England, Germany, and Holland. Not all of Boston’s stoneware came from overseas, though. Merchants also sold stoneware from potteries along the northeastern coast. In fact, ads for Connecticut stoneware had been appearing in Boston newspapers since the 1760s.[14]

To understand the significance of providing locally made stoneware, it is necessary to understand the conditions that shaped Boston’s politics and commerce in the late eighteenth century. Boston residents had no more embraced the notion of being dependent on British goods after the Revolution than they had before, and many remained openly hostile toward Britain. A writer in 1820 summed up the prevailing sentiment of Boston’s citizens throughout the years: “The first blood shed by British Soldiery was in our Streets; the first spot invaded of our Country, by a hostile army, was this metropolis; the first Port closed by their Mandates to distress our Merchants, was the Port of Boston; and the first resolve passed in favor of liberty, was in Faneuil Hall.”[15]

In April 1785 a local paper printed an address to the freemen and tradesmen of Boston asserting that too much of their money went to England to pay for imported goods. It also maintained that Boston’s carrying trade was suffering because its ships were not allowed to enter English ports or any other ports held by Britain.[16] That same month, Boston’s tradesmen and manufacturers published a notice expressing concern that their occupations were threatened by the importation of goods that could be manufactured locally. In an effort to promote domestic manufactures, they sought either a prohibition against those merchants or foreign agents who sold these imports or an imposition of duties on the imported goods themselves. They also proposed a boycott of all merchants or agents arriving from England to compete with local manufactures.[17] Word spread to tradesmen outside of Massachusetts as newspapers in other states picked up the notice, including William Little’s local paper, the Connecticut Journal.[18] Later in 1785, the merchants of Boston appealed directly to the merchants of New Haven.[19]

In 1789 Congress added an import duty of ten percent to stoneware and earthenware in order to encourage and protect domestic manufactures.[20] Governor John Hancock further encouraged Massachusetts manufactures in his January 1793 address to the state legislature, citing the successful establishment of a glass house and cotton manufactory in the state.[21] The growing movement in Boston against imported goods made the concept of a new stoneware manufactory extremely attractive provided the financial and logistical obstacles could be overcome.

Although he was a relative newcomer to Boston, William Little understood the complexities that surrounded its commerce very well. As a businessman, his wealth was dependent on the commercial success of Boston; as a politician, he had the ability to capitalize on it. Given his business acumen, it is plausible that he would develop an effective way to compete with the continual onslaught of imported stoneware. Moreover, Little owned several ships that were involved in the coastal trade, which gave him an advantage for transporting the clay from New Jersey.

This was not Little’s first attempt at a new manufacturing venture. In 1779 he and his partners had tried unsuccessfully to start the first glass manufactory in Connecticut. The legislature approved their project but the enterprise failed because they were unable to resolve their cost and labor issues.[22] Since stoneware, like glass, was a significant British import, it is reasonable to presume that Little considered a local stoneware manufactory to be a lucrative way to address Boston’s dependence on British goods.

In March 1793 William Little was on the selectmen’s committee that reviewed an application by Jonathan Fenton for permission to build a stoneware pottery on Lynn Street (fig. 2).[23] Fenton was a potter from New Haven, Connecticut, and it is possible that Little used his connections in his home state to recruit Fenton to move to Boston. The application was approved in April, and four months later an ad (fig. 3) appeared in the Columbian Centinel stating, “Stone Ware, of all kinds that is usually made, consisting principally of Jugs of different sizes, Butter and Pickle Pots, Mugs, Pitchers, and Gallipots, to be sold at the Manufactory, in Lynn-Street, North End; or at Store, No. 46, State Street.”[24] (It should be noted that No. 46 State Street was the address of William Little’s store.) Boston-

made stoneware was also advertised for sale in the south end of the city at James Leach’s new store on Newbury Street, but the business was short-lived.[25] By December, he had closed his doors and liquidated his stock.[26]

Tax records confirm that William Little and Jonathan Fenton were in business together. The entry for Jonathan Fenton in the 1794 Taking Book for Ward 1 identifies him as a potter in “partnership with Mr. Little.”[27] Lura Woodside Watkins believed that William Little bought the house on Greenough’s Alley in November 1792 for the purpose of housing a potter,[28] but the Taking Book contradicts that theory. Jonathan Fenton is shown to be living on Charter Street in Ward 1, some distance away from Greenough’s Alley, which was in Ward 2.

The new pottery on Lynn Street did not go unnoticed. An item published in 1794 stated: “At the stone pottery lately set up in Lynn Street, by Mr. Fenton from New Haven, all kinds of stone vessels are made after the manner of the imported Liverpool ware, and are sold at a lower rate. The clay for this manufacture is brought from Perth Amboy in New Jersey.”[29] Three years after it opened, the pottery was still regarded as a local success story and the Columbian Centinel wrote, “The Pottery at the North-end meets encouragement; and deserves it.”[30]

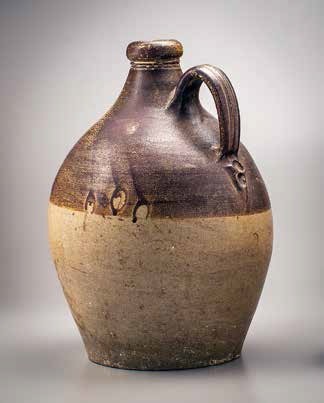

Stoneware made at the Lynn Street pottery mimicked the imports from Germany and England (figs. 4, 5). Jonathan Fenton was a master potter and his wares, although mostly styled after the German imports, had a decidedly American character. Fenton added his own mark with a distinct thumbprint placed at the base of each jug handle.

From the beginning, Boston stoneware differed from stoneware that was made elsewhere. Before 1800, it was not the custom for American-made stoneware to be marked with the potter’s name or location.[31] Among the exceptions were William Rogers of Jamestown and Anthony Duché of Philadelphia, who were known to put their initials at the base of the handles or on the necks, like the touchmarks of their English counterparts.[32] Potters who did mark their wares were usually working in an area where potteries had to compete for business.[33] Since there were no competing potteries in Boston, it would not have been unusual for the stoneware to be unmarked, but if the purpose of the pottery was to compete with imported wares, the simplest method for doing so was to mark its wares with the place of manufacture. Thus, the “BOSTON” mark was more than just a potter’s mark, it was a declaration.

The primary feature that set stoneware made at the Boston manufactory apart from stoneware made at other American potteries was that it was designed specifically to attract the local consumer. Not only were the wares marked “BOSTON,” but many were decorated with designs taken from easily identifiable local sources, making it even more desirable to Boston customers.

While imported German pieces were often beautifully decorated with incised florals colored with cobalt slip, their designs were conventional, and a jug shipped to Boston looked just like one shipped to New York or Philadelphia. American stoneware potters decorated some of their pieces with cobalt, but their designs, though attractive and sometimes elaborate, were generic and did not identify a particular locale. It is very likely that the decision to use Boston-specific designs was made by William Little, a shrewd businessman who was well acquainted with Boston and its environs, rather than Jonathan Fenton, a newcomer to the area. With his academic background, Little was probably familiar with the tenets of Scottish economist Adam Smith, who wrote in 1776 that “Consumption is the sole end and purpose of all production; and the interest of the producer ought to be attended to, only so far as it may be necessary for promoting that of the consumer.”[34] Following this maxim, Little would have offered his import-weary customers Boston-made stoneware decorated with attractive local motifs. Equally important, he would have understood that all too often principled dissent went only as far as the pocketbook would allow, so he offered his stoneware at a lower price than that of the imports.

Another feature of Boston stoneware that was unusual for American stoneware of the period was its predominance of decorated wares. While an American potter might decorate some of his stoneware with a brush of cobalt or incise an elaborate design on a handful of custom pieces, the Boston pottery was able to decorate most, if not all, of its output by employing a technique that emulated the more time-consuming incised designs. By using a stamp to impress a design into the soft clay and filling it in with cobalt, each piece could be decorated quickly and with a consistent quality, while still meeting production demands. As a result, beautifully decorated American stoneware could be sold at a price that was accessible to almost everyone, not just those who could afford the custom decorations.

To date, six impressed designs have been identified as those used at the Lynn Street pottery and incorporated into its standard jar and jug production forms: Flower, Codfish, Small Fish, Bird Eating Grapes, Native American Man, and JF Cartouche. A seventh design was used on a singular commissioned water or beer cooler with intricate applied decoration.

Flower. This is the most unremarkable design used by Fenton (figs. 6, 7). It consists of a simple five-petal flower with a cross-hatched center that is similar, but not identical, to sherds found at the circa 1811 States pottery site in Stonington, Connecticut (figs. 8, 9). As a result of the similarity between the two, many Stonington pieces have been attributed incorrectly to Boston. A Fenton-made jug with a cobalt slip-brushed flower that closely imitates the impressed examples may have been made before he had the stamp or while he was working in the Hartford, Connecticut, area between 1799 and 1801.[35]

Codfish. The cod-fishing industry was an essential part of Boston’s economy, and a replica of a codfish appeared both on the dome of the Boston State House and the top of Paul Revere’s silver shop. A 1784 resolution ordered that a codfish be suspended in the room where the House of Representatives sat “as a memorial of the importance of the Cod Fishery to the welfare of this Commonwealth.”[36] Stoneware has been found with an impressed codfish design as well as a codfish decoration that appears to have been made by applying a cobalt-dipped stamp (figs. 10-12).

Small Fish. The small fish closely resembles mackerel, which was a staple in Boston households (fig. 13). Late-eighteenth-century newspapers advertised “‘mackarel” fishhooks and lines as well as barrels of the preserved fish.

Bird Eating Grapes. This decoration is unique to Boston-made stoneware and possibly refers to Grape Island (figs. 14, 15). Located in Boston Harbor, the island was so named for the wild grapes that grew in abundance there during colonial times, attracting large flocks of birds. While birds in general were a popular motif on early American stoneware, an image as distinctive as this would have struck a familiar chord with those living in eighteenth-century Boston.

Native American Man. Another design unique to Boston stoneware is that of a standing Native American man that replicates the figure both on the Massachusetts coat-of-arms (engraved by Paul Revere) and the 1787 Massachusetts cent and half cent (figs. 16, 17). The use of a state icon certainly would bolster pride in a locally made product. This motif is the rarest of the designs, and perhaps was made for a special occasion or customer. The moccasins depicted on Boston stoneware have a distinct style, and duplicate those worn by the Native American on the coins, not on Revere’s coat-of-arms. Therefore, the stamp for this design, as well as the others used at the pottery, might have been made by Joseph Callender, the Boston engraver and die sinker who made the 1787 coin dies for the Massachusetts Mint.[37] Callender’s cousin had a ship-chandler business at the same address as William Little’s store, and if family relations were not enough to get the job, Callender also had apprenticed under Paul Revere, who belonged to the same Masonic lodge as William Little.[38]

JF Cartouche. This rare, elaborately interlocking monogram within a rope border is clearly the product of a highly skilled engraver (figs. 18-21). It is very possible that Joseph Callender was also responsible for this monogram.

Eagle Water Cooler. This monumental example of American stoneware was first described and attributed to Jonathan Fenton by the antique dealers and ceramic scholars Diana Stradling and J. Garrison Stradling in 2014 (fig. 23).[39] With an intricately modeled applied eagle, stars, and additional incised details, the cooler is a tour de force of Fenton’s artistry. The open looped handles and graceful baluster shape is in keeping with other jar forms. Traces of gold, red, and white paint in tandem with the blue cobalt suggest that the cooler was furthered embellished during its life with a patriotic color scheme. An open cartouche above the eagle bears tiny, impressed initials, “R.H.W.” (fig. 24).

The Stradlings speculated that the initials belong to the tavern owner who may have commissioned the cooler. More recent research in the Boston tax and land records from the mid-1790s has revealed two likely candidates.[40] The first is Redford Webster, a Boston druggist who was treasurer and trustee of the Boston Library Society from 1792 to 1829, and was one of the founding members of the Massachusetts Historical Society.[41] The second is Robert Wier (Wyer), a well-known Boston merchant and distiller.[42] Of those two, Wier is the most likely. According to tax and land records, he was around during the 1790s—he owned the North-End Coffee House, a three-story brick building reputed to be the highest-class coffeehouse in Boston, from 1786 until 1795, when he sold it to John May. It was a couple of blocks from William Little’s house on Garden Court Street, and, coincidentally, was built by Edward Hutchinson, the brother of Thomas Hutchinson, who was the last royal governor of Massachusetts and the original owner of Little’s house.

The name Jonathan Fenton does not appear in any of the Taking Books for 1796, indicating that he had left Boston by May, the month the tax assessors visited all of the households.[43] His time in Boston had been lucrative—in 1794–95 the value of his personal estate increased from $50 to $200.[44] After his departure, operations at the pottery were turned over to Frederick Carpenter, a potter who had worked at the New Haven pottery of Jacob Fenton, Jonathan Fenton’s uncle. Carpenter apparently arrived sometime after Fenton left, because he was still in New Haven as late as April 1796[45] and he does not appear in Boston tax records for that year.[46]

Carpenter was still considered a newcomer when he married Diana Heath in December 1796, because the newspaper identified him as Frederick Carpenter of New Haven.[47] The 1797 Taking Book for Ward 1 shows him living in Fenton’s old quarters on Charter Street, which was just a few doors away from the home of his father-in-law, Capt. Nathaniel Heath, before moving to Ward 3.[48] The entry shows that he was working with William Little, but gives no indication if they were in partnership together.

While Frederick Carpenter probably made pieces in the same Germanic style as Jonathan Fenton, his signature style was based on the two-toned, ocher-dipped English stoneware.

Frederick Carpenter’s first child was born in Boston in October 1797.[49] He returned to New Haven either later that year or early in 1798 because he does not appear in any of the May 1798 Taking Books. The Taking Book for Ward 1 suggests that Benjamin Lukis, a journeyman potter, worked at the Lynn Street pottery for part of 1798,[50] but by October there is no record of the pottery.[51] William Little continued to advertise Boston-made stoneware throughout 1799, possibly selling the remainder of his -inventory.[52]

Research has shown that the marketing strategies used by late-eighteenth-century iron merchants in New York City were more sophisticated than previously believed, focusing on promotion, distribution, and price. Goods were advertised to a targeted market and prices were adjusted as competition and demand warranted.[53] It appears that these strategies were not exclusive to the iron merchants. William Little used many of the same practices to promote locally made stoneware to his customers. By using familiar motifs and advertisements that touted the Boston origin of his stoneware, Little was able to develop both sales appeal and product branding. The end result was stoneware that is as distinctive now as it was in 1793, and its lasting appeal is something that not even William Little could have foreseen.

Quinquennial Catalogue of the Officers and Graduates of Harvard University, 1636–1915 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1915), p. 808; Franklin Bowditch Dexter, ed., The Literary Diary of Ezra Stiles, D.D., LL.D., President of Yale College, 3 vols. (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1901), 3:469.

Charles J. Hoadly, The Public Records of the State of Connecticut, from October, 1776, to February, 1778, inclusive, with the Journal of the Council of Safety from October 11, 1776, to May 6, 1778, inclusive, and an Appendix, comp. Leonard Woods Labaree (Hartford, Conn.: Case Lockwood & Brainard Co., 1894), p. 319.

Eliphalet Gilman Storer, The Records of Freemasonry in the State of Connecticut, with a Brief Account of Its Origin In New England, and the Entire Proceedings of the Grand Lodge, from Its First Organization, A. L. 5789, Compiled from Authentic Sources, by E. G. Storer (New Haven: E. G. Storer, 1859), pp. 22, 32.

Connecticut Gazette, October 28, 1785, p. 3; Dexter, Literary Diary of Ezra Stiles, p. 231.

Massachusetts Centinel, May 9, 1787, p. 59.

Herald of Freedom, and the Federal Advertiser, January 20, 1789, p. 152. Loan Office certificates were issued to pay off foreign debts incurred during the American Revolution.

Boston Public Library, Rare Books & Manuscripts, City of Boston Tax Records, 1780–1821: Tax Book Ward 8, 1787, p. 10; Taking Book Ward 8, 1789, p. 11; Tax Book Ward 3, 1789, p. 12; Tax Book Ward 3, 1790, p. 8.

The Massachusetts Centinel, March 13, 1790, p. 209.

“Massachusetts Land Records, 1620–1986,” images, FamilySearch: https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-99Z3-Q8Z3?cc=2106411&wc=MCB5-YTL%3A361613401%2C362239501 :22 May 2014), Suffolk Deeds 1791–1792, vol. 171–173, image 300 of 921; county courthouses and offices, Massachusetts.

Boston Gazette, and the Country Journal, April 18, 1791, p. 3.

Columbian Centinel, October 23, 1793, p. 3.

Samuel Eliot Morison, The Maritime History of Massachusetts, 1783–1860 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1922), p. 131.

Ultimately, Britain’s actions had the unintended consequence of creating even more wealth for Boston as its merchants discovered profitable new markets in the Far East in what would become known as the China Trade.

Boston-Gazette, and the Country Journal, February 27, 1769, p. 3.

“Celebration of Independence,” Bunker-Hill Centinel and Middlesex Republican, July 1, 1820, p. 3.

“Inflamation [sic],” Massachusetts Centinel, April 13, 1785, p. 2.

“Boston, April 28,” Continental Journal, April 28, 1785, p. 2.

Connecticut Journal, May 11, 1785, p. 2.

New-Haven Gazette, September 29, 1785, p. 3.

Independent Chronicle and the Universal Advertiser, July 16, 1789, p. 2.

Governor John Hancock’s address to the Massachusetts State Legislature, January 31, 1793.

Report of the Commissioner of Patents, for the Year 1850, Part I, Arts and Manufactures (Washington, D.C.: Office of Printer to the House of Representatives, 1851), pp. 448–50.

A Report of the Record Commissioners of the City of Boston, Containing the Selectmen’s Minutes from 1787 through 1798 (Boston: Rockwell and Churchill, 1896), p. 200.

Ibid., p. 202; Columbian Centinel, August 14, 1793, p. 3.

Columbian Centinel, October 5, 1793, p. 4.

American Apollo, December 6, 1793, p. 3.

Boston Public Library, Rare Books & Manuscripts, City of Boston Tax Records, 1780–1821: Taking Book Ward 1, 1794, p. 2. Tax assessors went house-to-house in their wards and recorded names, occupations, and property values in their taking books, which were then used to determine the amount of tax due.

Lura Woodside Watkins, “New Light on Boston Stoneware and Frederick Carpenter,” The Art of the Potter: Redware and Stoneware, ed. Diana Stradling and J. Garrison Stradling (New York: Main Street/Universe Books, 1977), p. 82.

Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society, for the Year 1794, Vol. III (1794; reprint, Boston: Munroe & Francis, 1810), p. 280.

“Municipal Miscellany,” Columbian Centinel, August 3, 1796, p. 1.

Lura Woodside Watkins, Early New England Potters and Their Wares (1950; [Hamden, Conn.]: Archon Books, 1968), p. 81.

Janine E. Skerry and Suzanne Findlen Hood, Salt-Glazed Stoneware in Early America (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 2009), pp. 187, 191.

Georgeanna H. Greer, American Stonewares: The Art and Craft of Utilitarian Potters, rev. 3rd ed. (Atglen, Pa.: Schiffer, 1999), p. 137.

Adam Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations; in Three Volumes. With Notes and an Additional Volume, by David Buchanan (Edinburgh: Oliphant, Waugh, and Innes, 1814), p. 535.

Connecticut Courant, June 22, 1801, p. 2.

Robert Shackleton, The Book of Boston (Philadelphia: Penn Publishing, 1920), pp. 70–71.

The Historical Collections of the Topsfield Historical Society, Vol. XXV, ed. George Francis Dow (Topsfield, Mass.: Topsfield Historical Society, 1920), p. 127.

John T. Heard, A Historical Account of Columbian Lodge of Free and Accepted Masons of Boston, Mass. (Boston: Printed by A. Mudge and Son, 1856), p. 350.

Diana Stradling and J. Garrison Stradling, “Dealers’ Choice,” in Ceramics in America, ed. Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2014), pp. 208–30.

Boston Public Library, Rare Books & Manuscripts, Boston Tax Records, 1780–1821: Taking Book Wards 1–12, 1790–1798; The Boston Directory: Containing the Names of the Inhabitants, Their Occupations, Places of Business, and Dwelling-Houses. Also, a List of the Town Officers; Public Offices, Where and by Whom Kept; Banks, &c. &c. To Which Is Prefixed, a General Description of Boston. Ornamented with a Plan of the Town, Taken from Actual Survey (Boston: Printed by Manning & Loring for John West, 1796), pp. 105, 109.

A Catalogue of the Books of the Boston Library Society, in Franklin Place. January 1844 (Boston: T. R. Marvin, 1844), p. iv; Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society. Vol. 1: 1791–1835 (Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 1879), pp. 490–92; Redford Webster, 1761–1833, Redford Webster daybook, 1784–1787 (inclusive), Mss 845, 1784–1787, W383, Baker Library Historical Collections, Harvard Business School, Colonial North America at Harvard Library.

“Massachusetts Land Records, 1620–1986,” images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L9Z3-98YL?cc=2106411&wc=MCB5-RTL%3A361613401%2C362221501 : 22 May 2014), Suffolk, Deeds 1786–1787, vol. 157–159, image 97 of 841; county courthouses and offices, Massachusetts; “Massachusetts Land Records, 1620–1986,” images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-99Z3-9VT4?cc=2106411&wc=MCB5-Y3F%3A361613401%2C362258101 : 22 May 2014), Suffolk Deeds 1795, vol. 180–181, image 570 of 605; county courthouses and offices, Massachusetts; Samuel Adams Drake and Walter Kendall Watkins, Old Boston Taverns and Tavern Clubs, new illustrated ed. (Boston: W. A. Butterfield, 1917), p. 116.

Boston Public Library, Rare Books & Manuscripts, City of Boston Tax Records, 1780–1821: Tax Book Wards 1–12, 1796.

Boston Public Library, Rare Books & Manuscripts, City of Boston Tax Records, 1780–1821: Tax Book Ward 1, 1794, p. 3, and 1795, p. 4.

Connecticut Journal, April 7, 1796, p. 3.

Boston Public Library, Rare Books & Manuscripts, City of Boston Tax Records, 1780–1821: Tax Book Wards 1–12, 1797.

Massachusetts Mercury, December 13, 1796, p. 3.

Boston Public Library, Rare Books & Manuscripts, City of Boston Tax Records, 1780–1821: Taking Book Ward 1, 1797, p. 3.

Massachusetts, Town and Vital Records, 1620–1988, ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com/search/collections/matownvital/), s.v. “Diana Carpenter.”

Boston Public Library, Rare Books & Manuscripts, City of Boston Tax Records, 1780–1821: Taking Book Ward 1, 1798, p. 10.

A Report of the Record Commissioners of the City of Boston Containing the Statistics of the United States’ Direct Tax of 1798, as Assessed on Boston and the Names of the Inhabitants of Boston in 1790, as Collected for the First National Census (Boston: Rockwell and Churchill, 1890).

Columbian Centinel, October 5, 1799, p. 4.

Allen S. Marber, “The Origins of Modern Marketing: The Marketing Orientation of the New York Iron Merchant,” in Marketing History—Its Many Dimensions Proceedings of the Fifth Conference on Historical Research in Marketing and Marketing Thought, held April 19–21, 1991, at the Kellogg Center of Michigan State University, eds. Charles Taylor, Steven W. Kopp, Terence Nevett, and Stanley C. Hollander, pp. 303–20.