Plate, Jingdezhen, decorated in Guangzhou (Canton), China, 1795. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 9-1/2". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, W-5422; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

James Peale (1749–1831), Portrait of Martha Washington, 1796. Watercolor on ivory. 1-5/8 x 1-1/4". (Courtesy Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, W-624; photo, Paul Kennedy.)

Attributed to Chitqua (ca. 1728–1796), Figure of a Dutch Merchant, possibly Andreas Everardus van Braam Houckgeest, ca. 1770. Unfired clay and oil paint. H. 14 3/8". (Rijksmuseum, BK 1976-49.)

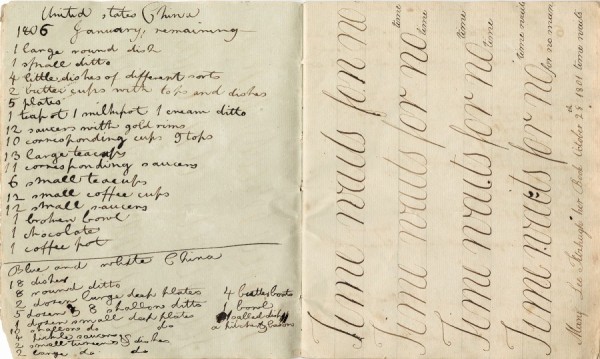

Detail of Commonplace Book, [n.d.]. 8 x 6 1/4". (Courtesy, Virginia Museum of History & Culture, in Section 8, Papers, 1694–1917, Mss. 1 L5144a 357, Virginia Historical Society, Richmond.) Mary Fitzhugh Custis’s inventory for the States service (left, dated 1806) appears next to an earlier penmanship lesson (right, dated 1801).

Junius Brutus Stearns (1810–1885), George Washington Parke Custis of Arlington, 1848. Oil on canvas. 30 x 26". (Museums at Washington and Lee University, U1959.1.3; photo, Brian Muncy.)

Cephas Thompson (1775–1856), Portrait of Mrs. George Washington Parke Custis (Mary Lee Fitzhugh Custis), 1807–1808. Oil on canvas. 32-1/4 x 27" (framed). (Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Gift of Mary A. Smith Bowman, 76.21.1.)

Cover for a teapot, Jingdezhen, decorated in Guangzhou (Canton), China, 1795. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 3-5/8". (Courtesy, The White House, 1917.2751.2; photo, Bruce White.)

Teapot, Jingdezhen, decorated in Guangzhou (Canton), China, 1785. Hard-paste porcelain. H. 4-1/2". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, W-1436 E; photo, Edward Owen.)

Sugar bowl, Jingdezhen, decorated in Guangzhou (Canton), China, 1795. Hard-paste porcelain. H. 31 3/16". (Courtesy, The White House, 1917.2751.1; photo, Bruce White.)

Covered cup and saucer, Jingdezhen, decorated in Guangzhou (Canton), China, 1795. Hard-paste porcelain. H. of cup 5". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, W-1497 A, C; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Saucer for covered cup, Jingdezhen, decorated in Guangzhou (Canton), China, 1795. Hard-paste porcelain. D. of saucer 6". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, W-5372; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

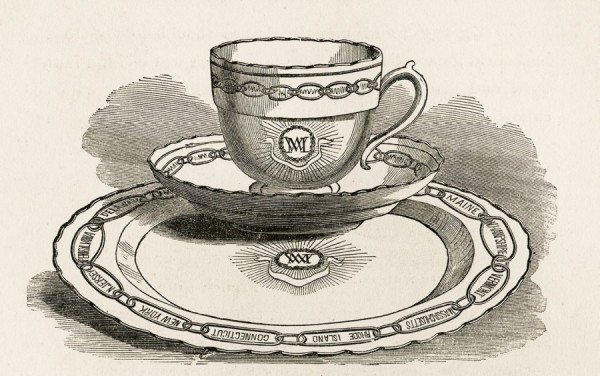

Teacup, saucer, and plate, illustrated in Benson J. Lossing, Mount Vernon and Its Associations: Descriptive, Historical, and Pictorial (New York: W. A. Townsend & Co., 1859), p. 241. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association.)

Saucer, Jingdezhen, decorated in Guangzhou (Canton), China, 1795. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 6". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, W-1497 B; photo, Mark Finkenstaedt.)

Dish, Jingdezhen, decorated in Guangzhou (Canton), China, 1795. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 13". (Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library, Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont, 1963.0705.)

Dish, Jingdezhen, decorated in Guangzhou (Canton), China, 1795. Hard-paste porcelain. L. 8 1/2". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, W-5308; photo, Mark Finkenstaedt.)

Benson J. Lossing (1813–1891), Arlington House, 1853. Watercolor on paper. 8 1/4 x 9 1/2". (Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial, National Park Service, ARHO 123.)

William Edward West, Mary Anna Randolph Custis Lee, 1838. Oil on canvas. 30 x 25". (Museums at Washington and Lee University, Bequest of Mrs. Robert E. Lee III, U1959.1.2.)

Harris & Ewing, Mary Custis Lee, 1914. Glass plate negative. H. 7". (Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-hec-05389; https://www.loc.gov/item/ 2016866128/.)

Photo of framed saucer, c. 1921. Saucer 6". The saucer from the States service was framed about 1840 in a frame made from the wood of the "Charter Oak," located in Hartford, Connecticut. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, W-509.)

“General Lee’s Slaves, Arlington, House,” believed to be Selina Gray (far right) and two of her daughters, ca. 1860s. Stereograph. 3 5/32 x 6 11/16". (Courtesy of the George Washington Memorial Parkway, Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial, National Park Service, ARHO 15585)

A RECENTLY DISCOVERED inventory made in 1806 provides new insights into the composition and history of one of the most important Chinese export porcelain services made for the American market: the service that was given to Martha Washington (1731–1802) by Andreas Everardus van Braam Houckgeest (1739–1801) in 1796 (figs. 1–3).[1]

Known since at least the early nineteenth century as the “States service,” each piece is decorated with a chain of fifteen links, each link containing the name of one of the states that made up the nation in 1796.[2] In the center, Martha Washington’s monogram is framed within a laurel wreath set within a golden sunburst. Below the sunburst flutters a ribbon inscribed “decus et tutamen ab illo,” and a serpent biting its tail encircles the rim.

Approximately two dozen pieces are known to survive, and up until the discovery of this inventory, it was not known exactly what other pieces the service contained. The inventory is in a commonplace book kept by Mary Fitzhugh Custis (1788–1853) during the early years of her marriage to George Washington Parke Custis (1781–1857), the grandson of Martha Washington who was raised at Mount Vernon and who inherited the States service (figs. 4–6). The inventory, which was probably made at Arlington, the Custis home, is titled “United states China 1806 January: remaining,” shows that it was an exceptionally large and elaborate service designed to serve tea, coffee, and hot chocolate or caudle to at least a dozen guests (see figure 4.)[3] Analyzing the inventory and its creation gives us a better understanding of the service itself, and also what the service meant to those who, over time, commissioned, gifted, used, inherited, rescued, and curated it in private and public collections.

The service was commissioned by the Dutchman Andreas Everardus van Braam Houckgeest as a gift for Martha Washington. Van Braam spent much of his career working for the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (known alternately as the Dutch East India Company or VOC), making three voyages to China between 1758 and 1777. He retired in 1777, and in 1783 emigrated with his family to Charleston, South Carolina. Following the death of four of their children and the loss of his fortune, he and his wife returned to the Netherlands in 1788, whereupon he rejoined the VOC. From 1790 to 1795 he served as director of the Dutch factory in Guangzhou, the Chinese port known to Westerners as Canton, and was part of an embassy from the VOC to the Qianlong emperor in 1794–1795. He returned to the United States in 1796, and lived there until 1798, when he returned to Europe.[4]

During his time in China, Van Braam made a second fortune, by trading in opium and facilitating trade between the United States and China.[5] He used part of his new fortune to amass a large collection of porcelain, paintings, and other objects, which he brought with him to the U.S. He arrived in Philadelphia on April 1796 aboard the Lady Louisa, and among the 116 parcels of Chinese goods he had with him was “a Box of China for Lady Washington.”[6]

It is not known when or how Van Braam presented his gift to Martha Washington. Equally unknown and perhaps even more perplexing is why he went to the trouble and expense of commissioning such a lavish gift for someone he did not personally know. The gift was probably inspired at least in part by his regard for George Washington, to whom Van Braam dedicated his book, An Authentic Account of the Embassy of the Dutch East-India Company, to the Court of the Emperor of China, writing, “Permit me then to address the homage of my veneration to the virtues which in your Excellency afford so striking a resemblance between Asia and America. I cannot shew myself more worthy of the title of Citizen of the United States, which is become my adopted Country, than by paying a just tribute to the Chief, whose principles and sentiments are calculated to procure them a duration equal to that of the Chinese Empire.”[7]

But the gift also might have been a way to gain access to the Washingtons. They were the recipients of a number of gifts from manufacturers, politicians, and others looking for a way to gain attention, favor, and influ-ence for themselves or their work. In 1782, for instance, the French army officer Adam Philippe, comte de Custine, gave the Washingtons a tea set made at his Niderviller porcelain factory. The service, which is decorated with George Washington’s monogram, was given to Martha when the comte visited Mount Vernon. The fact that each piece displays a different border pattern and has the pattern number painted on the bottom suggests that the gift was at least partly motivated by a desire to encourage American patronage of the factory.[8]

Whatever his motivations in selecting a tea set as his gift for Martha, Van Braam was choosing an imminently suitable present; while tea was drunk by both sexes, it was most associated with women. Tea (and, to a lesser extent, coffee and chocolate) was an important part of polite female sociability; it was a vehicle for entertaining and part of the culture of visiting, where women would call on female friends and neighbors for short visits. Tea parties were also one of the few social occasions that were led by women and attended by both men and women.[9]

Fine teawares were, according to one historian, “indispensable props” for polite entertaining—just the sort of thing a woman of status like Martha Washington would need and presumably want.[10] That the service was Chinese porcelain also added extra cachet; it had long been prized as the finest type of ceramic available, and owning it was a mark of wealth and good taste. In the United States, it took on added meaning as a symbol of independence from Britain’s restrictive trade policies and the new nation’s entrance into the lucrative China Trade.

The service was almost certainly designed by Van Braam. Drawing inspiration from prints, emblem books, illustrations, and his own imagination, Van Braam assembled elements that created a message of strength, unity, and permanence for the new United States.

The chain of states—an emblem developed by Benjamin Franklin in 1776 for use on congressional paper currency—represents strength through unity. It quickly became one of the most popular emblems of the new nation, and appeared on coins, medals, patriotic prints, buttons, and a range of ceramics, any of which could have found their way into Van Braam’s hands to be used as a design source.[11] The snake swallowing its tail, also known as an ouroboros, symbolizes infinity and eternity. The inspiration could have come from La Feuille’s Devises et emblèmes (1691), a popular emblem book in which “a snake that puts its tail in its mouth” was paired with the motto “the end dependeth from the beginning.”[12]

The sunburst that emanates from Martha Washington’s monogram is known as a “glory” and, according to one book on heraldry, denotes “Glory, Grandeur, Power, Etc.”[13] Another emblem book pairs a sunburst with the motto “not for oneself but for the world.”[14] All reinforce the fame and honor of Martha and, through her, George Washington. The motto, “decus et tutamen ab illo,” which can be roughly translated as “[our union is our] glory and defense from him,” suggests the strength of the United States and its victory over George III of Great Britain during the American Revolution.[15]

Van Braam would have worked with a Chinese merchant in Guangzhou to design the service, probably someone like Yam Shinqua, “China Ware Merchant at Canton,” who advertised “All sorts of Chinaware, Arms, Etc. Painted on the most reasonable Terms.”[16] Together, they would have selected the forms to include in the service from a stock of blanks made in the porcelain production center of Jingdezhen in south-central China. Chinese painters would have painted the porcelain and fired it in a low-temperature muffle kiln to fix the overglaze enamels. The process would have taken a few weeks and was probably done just prior to Van Braam’s departure in 1795.

The inventory shows that this must have been one of the largest and most elaborate beverage services made in Chinese export porcelain in the late eighteenth century. The 1806 inventory records that as of January 1806 the following pieces were in Custis family hands:

1 large round dish

1 small ditto

4 little dishes of different sorts

2 butter cups with tops and dishes

5 plates

1 teapot 1 milkpot 1 cream ditto

12 saucers with gold rims

10 corresponding cups 9 tops

13 large teacups

11 corresponding saucers

6 small teacups

12 small coffee cups

12 small saucers

1 broken bowl

1 chocolate

1 coffee pot

While other pieces had been lost over the previous decade, enough remained to allow us to reconstruct the service, match surviving pieces to the inventory, and make an educated guess as to what the now-missing pieces were.

The surviving flat cover to the teapot, which has been mistakenly paired with the sugar bowl since about 1880, suggests that the teapot had a drum-shaped body, intertwined strap handle, and a straight-sided spout (fig. 7). This was the most common teapot form produced in the 1780s and 1790s; one of them was part of George Washington’s Cincinnati service made in 1785 (fig. 8).[17] While the inventory lists only one teapot, large tea sets often had two. For example, the 65-piece tea set recorded in a list of prices current in Guangzhou by a Rhode Island merchant in 1797 included a large teapot, top, and stand, plus a smaller teapot, top, and stand.[18] The “long tea sets of 101 pieces” available in Guangzhou in 1813 also included “2 teapots of 2 sizes.”[19]

The coffeepot is not known to survive, but the most common form in the period was a “lighthouse shaped” pot with a tall, conical body, straight spout, and intertwined strap handle (fig. 9).[20]

The chocolate pot, also not known to survive, most likely was a cylindrical pot with a curved spout, domed cover, and a pistol-grip handle at a right angle to the spout. This was the most common form of chocolate pot during the period; a similar one decorated with the Cincinnati badge was commissioned by Samuel Shaw for his own use about 1790 (fig. 10).[21]

The inventory records a milk pot, cream pot, and a broken bowl.[22] Most sets would have had just one pot for milk or cream, with only the largest having both, such as the “long tea sets of 101 pieces” available in Guangzhou in 1813 that included both a milk pot and cover and a cream pot without a cover.[23] The fact that the inventory describes a milk pot and a cream pot suggests that there were two different forms. One was most likely a helmet-shaped cream jug, similar to the ones included in the tea services decorated with the badge of the Society of the Cincinnati that Samuel Shaw commissioned in 1790 as gifts for friends.[24] The other was probably a slightly smaller pear-shaped pot with a long neck, intertwined strap handle and a domed cover; this form appears in tea sets made in the last quarter of the eighteenth century (figs. 11 and 12).[25]

The “broken bowl” was most likely a slop bowl, six to eight inches in diameter, designed to collect the dregs of tea from cups and the used tea leaves from the pot (fig. 13).

Missing from the list is a sugar bowl, a mainstay of any hot beverage service. This set had at least one, which was part of the Washington heirlooms confiscated from Arlington in 1862 (fig. 14).[26] The sugar bowl presumably was at Arlington in 1806, but was either missed or miscataloged. It is possible that the “2 butter cups with tops and dishes” in the inventory were sugar bowls, as very large sets sometimes did have two—for example, the “2 large sugar cups, plates, and covers” that were part of “long tea sets” available in Guangzhou in 1813.[27]

It is likely that the service also had a tea caddy, though one does not appear in the Custis inventory. The most common form was a rectangular caddy with sloping shoulder and a cylindrical neck, like the one in Washington’s Cincinnati service (fig. 15).[28]

The inventory records at least four different types of cups and saucers: “12 saucers with gold rims [and] 10 corresponding cups 9 tops”; “13 large teacups [with] 11 corresponding saucers”; “6 small teacups”; “12 small coffee cups”; and “12 small saucers.”

The twelve gold-rimmed saucers and the “10 corresponding cups 9 tops” were large, double-bellied, two-handled covered cups and saucers (figs. 16, 17). Originally, there were probably twelve. Not usually part of a tea and coffee service, these large cups were luxury products; at least some covered cups made at European factories were as much decorative as utilitarian, meant to be displayed rather than used.[29] When they were used, they held any number of warm beverages, among them hot chocolate, which was often seen as a nourishing breakfast drink, or caudle, a warm drink made of gruel, wine, sometimes milk, spices, and sugar.[30] Caudle was often served to new mothers and their guests that visited during their lying-in (the period of recuperation following the birth of a child).[31]

None of the other cups and saucers is known to survive, but Benson J. Lossing, the historian and friend of the family, recorded a double-bodied handled cup and a corresponding saucer in Mount Vernon and Its Associations (1859) (figs. 18, 19).[32] In the 1790s only the most expensive Chinese export teacups had handles, the majority had none.[33] The double-bellied form was popular in the 1780s and 1790s and were loosely based on models produced at the Royal Manufactory at Sèvres in France from the 1750s.[34]

Without knowing the size of the saucer illustrated in the engraving (see fig. 15), the cup could be one of either the large or the small teacups recorded in the inventory. It was common for large services to have two sets, one larger than the other. English and American merchants tended to describe larger cups as breakfast cups, suggesting they were used in the morning by sleepy drinkers who wanted larger servings of the caffeinated beverage.[35]

The “13 large teacups” could have been the original number of cups; most services had cups and saucers in multiples of six or twelve, but large services did sometimes include an extra cup and saucer to account for breakage. In 1797, for instance, a Rhode Island merchant noted that 43- and 45-piece tea sets were available, the larger having “1 tea cup more than a sett of 43 pcs.”[36] Alternately, it could have been a very large service of twenty-four cups and saucers.

The “6 small teacups” might have been smaller versions of the larger cups, or perhaps they were handle-less teabowls. Most likely the original set had twelve or thirteen, but possibly twenty-four.

The “12 small coffee cups” probably had cylindrical bodies and one handle, a form derived from French porcelain and popular in Chinese porcelain from about 1790 into the mid-nineteenth century (fig. 20).[37] The original set likely would have included twelve or thirteen cups, though it is possible that there were twenty-four.

While tea- and coffee cups sometimes shared a saucer, large services usually had saucers for each cup. Saucers for cylindrical coffee cups typically had straight, slanted sides, whereas teacup saucers usually had curved sides. Presumably the “12 small saucers” recorded in the inventory were all the same (otherwise they would have been separated out), and so were intended for either the coffee cups or the teacups.

In addition to the beverage wares, the “1 large round dish, 1 small ditto, 4 little dishes of different sorts, 2 butter cups with tops and dishes, and 5 plates” show that the service allowed Martha Washington to serve food as well, which most likely was bread and butter, cookies, or cake.[38]

The “large dish” is almost certainly the surviving saucer-shaped dish that is fourteen inches in diameter (fig. 21).[39] The “small ditto” probably would have been eight to ten inches in diameter.

The “four little dishes of different sorts” were likely small shaped dishes used for serving baked goods, fruit, or other sweet or savory morsels. At least one, a quatrefoil dish, survives (fig. 22).[40] Its shape copies larger compotiers developed in the mid-eighteenth century at the Sèvres manufactory as a component of dessert services. The other three dishes could have been the same shape, or could have been oval, trefoil, or shell-shaped, based on similar forms made for the dessert service.[41]

While serving dishes for bread or cake were commonly part of large tea services, individual plates were not. The presence of 9 1/4"-diameter plates is another indication of just how large and elaborate the States service was (see fig. 1). Five plates were recorded in the inventory, suggesting that originally there were at least six, and more likely twelve.

Presumably Martha Washington received the service from Van Braam Houckgeest shortly after he arrived in Philadelphia in 1796. Philadelphia served as the nation’s capital from 1790 to 1800, and the Washingtons lived there from late 1790 until early 1797. We have no record of what Martha thought about the service, although circumstantial evidence suggests it was of use and of value to her.

The gilding on many of the surviving pieces is badly worn, which shows that they were used, and washed, with some frequency. Moreover, fragments of two saucers have been recovered from the yards around the laundry and kitchen at Mount Vernon, suggesting that they were broken in use and the fragments discarded by enslaved servants along with other household waste.[42]

We believe Martha recognized the symbolic value of the service because she gave at least one piece away, beginning the process of transforming it from a functional houseware into a relic associated with George Washington. In June 1798, Julian Niemcewicz, a Polish aide to the Revolutionary War officer Andrew Thaddeus Kosciuszko, visited Mount Vernon. Upon his departure, “Mrs. Washington made me a gift of a china cup with her monogram and the names of the states of the United States.”[43] In his thank-you letter to her husband, Niemcewicz asked him to pass on his thanks again “to Mistris Washington for her unceasing attention & goodness, & for the present of a Cup marked with her Initials, which when sipping my Coffe will daily remind me of Mount Vernon.[44]

Martha died in 1802 and to her grandson, George Washington Parke Custis, left “the set of tea China that was given me by W. Vanbram every piece having MW on it.”[45] Martha bequeathed to her one male descendant dynastic objects that reflected the Custis and Washington families’s social status, and which would give Custis the cultural capital needed to maintain a position as a person of consequence. This inheritance included the Chinese export porcelain service decorated with the insignia of the Society of Cincinnati, family portraits and silver, and the bed in which George Washington died.

Custis brought his “Mount Vernon Relics” to a four-room cottage at Arlington, one of several estates he inherited from his father, John Parke Custis. The cottage was unsuitable both as a home for someone of Custis’s status and as a repository for items preserved to foster an appreciation of the nation’s first president, and so in 1802 he began constructing Arlington House, a temple-like mansion on “the heights” overlooking the nation’s capital (fig. 23).[46]

In July 1804, Custis married Mary Fitzhugh, a family friend of his grandparents.[47] Introduced through her parents’ hospitality at their plantation, Chatham, and townhouse in Alexandria, Mary Fitzhugh Custis was part of the Virginia elite and shared many of her husband’s intellectual interests. They moved to Arlington, which at that point consisted of just the north and south wings of the house separated by an empty space that in about 1820 would be filled with the central section fronted by massive Doric columns.[48] Together, they cultivated Arlington as a public destination where visitors could see the portraits, furniture, silver, porcelain, and other Mount Vernon items in the “Washington treasury.”[49]

In January 1806, Mary Custis made an inventory of the States service.[50] It is one of several that she seems to have made about this time that included surviving pieces of the “Cincinnati China,” “blue and white china,” furniture, fireplace equipment, kitchen equipment, and textiles. The inventories were recorded in a slim commonplace book bound in gray-and-green marbled paper covers and inscribed “Mary Lee Fitzhugh her Book October 28th 1801.” It was begun as a school notebook, and was half-filled with lessons in penmanship, literature, and poetry. Following her marriage, she repurposed the remaining pages as a household account book, prioritizing the States and Cincinnati services and listing them by name. Subsequent lists appear to itemize functional housewares, including the tablecloths, towels, and sheets “left in Rachel’s care.”[51] It is not clear why Mary Custis made these inventories; perhaps the Custises moved between their various plantations and drew up lists of what was where. The Arlington house was expanded and renovated several times, which might have necessitated household goods being stored or relocated.

It is perhaps telling that Mary Custis titled the inventory “United states China January 1806, remaining,” suggesting that the service had already lost a number of pieces. Relative to the other “Mount Vernon relics” treasured by the Custises, the States china was exceptional in that the family elected to give many of the pieces away; an article in the New York Daily News in 1862 recalled that “A plate, a saucer, or a cup, were occasionally presented by Mrs. Washington or Mr. Custis as the choicest souvenir they could give of the household relics of Mount Vernon.”[52]

This activity suggests that the service had become valued more for its historical associations with George and Martha Washington than for its usefulness as a beverage service. Such associational objects appreciated in their value only to the nineteenth-century Americans who viewed them as physical reminders of the founding of the nation and as tools for crafting a shared national identity and history.[53]

Their remembrances of George and Martha Washington -surrounding the Mount Vernon collection at Arlington was a source of constant discus-sion, pride, and prestige for Mary and George Washington Parke Custis, their daughter Mary Anna Randolph Custis (1807–1873) (fig. 24), and their granddaughter Mary Custis Lee (1835–1918) (fig. 25). Historian Cassandra Good has argued that these objects provided the Washingtons’ descendants with what anthropologists and historians have called “cultural capital,” which the Custis family deployed to build and maintain their social and political position and influence.[54]

Pieces from the States service were prominently displayed at Arlington and interpreted for visitors. In 1856, a family friend wrote home about what she had learned on a guided tour of the drawing room: “On the mantel-piece stands china from Mt Vernon—a cup & saucer of porcelain, manufactured in China, & painted in E . . . & presented to Genl. and Mrs. Washington by Van Brahaam, I believe an E. India merchant. Around the rim runs a chain with the names of each state (15) inserted in the links.”[55] It is possible on that the service was even used to entertain prominent guests; it is known that the Cincinnati service was used on occasion, and at least one saucer from the States china was broken and discarded during the period in which Arlington was being built, suggesting that it could have been broken in use.[56]

The Custises capitalized on the value of the States service and other Mount Vernon items by judiciously giving pieces away to admirers of Washington, including prominent national and even international figures.[57] In 1824, nearly two decades after she made the inventory, Mary Custis gave a saucer to Eunice Trumbull, the widow of Jonathan Trumbull Jr. of

Connecticut (fig. 26). George Washington Parke Custis asked her son-in-law, Benjamin Silliman, to deliver it, writing, “My Dr Sir, Mrs. Custis entrusts to your care the accompanying little present, for the venerable Mrs. Trumbull, relict of the late Governor Trumbull, who was a member of the military family of Washington in the War of the Revolution. Mrs. Custis begs leave to add her perfect respect for the person & character of this excellent Lady, in the which, I most cordially unite, & have the honour to be My Dr Sir. P.S. The china was made at Canton especially for Genl. Washington & presented to him on his first Presidency of the United States.”[58]

Silliman had visited the Custis family’s collection in preparation for the return to the United States of the marquis de Lafayette, an occasion that inspired the family to offer meaningful gifts of relics to honor those who had known and served with Washington. Lafayette is also thought to have been given a piece during this visit, in addition to other gifts with stronger military associations.[59]

Family members were given other pieces, such as “the China at Tudor Place, with the thirteen states around it and letters MW” that belonged to Britannia Peter Kennon (1815–1911), Martha Washington’s great-granddaughter, in 1856.[60] At least one piece went to Eliza Parke Custis (1776–1831), George Washington Parke Custis’s older sister.[61]

By the 1840s most of the service seems to have been gone from Arlington. Mary Custis Lee wrote to Eliza Stiles, whose husband was ambassador to the Austrian Empire, “I have searched thro’ the house and find our stock of the States China is reduced so low that I cannot send you a whole piece and the broken ones would give a very imperfect idea of the device. I send you a small tureen of Cincinnati, which you must value very highly, as they are getting very rare and it is almost like parting with one of my family to send it so far. Present it where you think it will be most prized. . . .”[62]

Mary Fitzhugh Custis died in 1853, and George Washington Parke Custis died in 1855. He left Arlington and its contents to his daughter, writing that she “has the privilege, by this will, of dividing my family plate among my grandchildren, but the Mt. Vernon altogether, and ever article I possess relating to Washington and that came from Mt. Vernon is to remain with my daughter at Arlington House during said daughter’s life, and at her death go to my eldest grandson, George Washington Custis Lee, and to descend from him entire and unchanged to my latest posterity.”[63]

Known for her attention to the family papers and stories told by her father, Mary Custis Lee publicized the collection as “Washington Relics” with Benson J. Lossing. Her careful documentation informed her priorities to safeguard the relics at the onset of the American Civil War in May 1861, when Arlington’s position overlooking the nation’s capital and the family’s allegiance to the Confederate States of America meant that the estate faced occupation by opposing Union troops led by Union Brigadier General Irvin McDowell. Dispersing some furnishings and silver to relatives, she packed many items for safekeeping at Arlington under the supervision of Selina Gray, her enslaved housekeeper (fig. 27). She noted that “the Cincinnati and State China from Mount Vernon was carefully put away and nailed up in boxes in the cellar.”[64]

Although Mary Custis Lee and General McDowell had corresponded about respecting this treasury during wartime, it was Gray who alerted McDowell that these items were no longer safe. In January 1862 McDowell wrote: “A short time ago an aged old negro woman belonging to the estate came to tell me she had been entrusted by her mistress with the key of one of the cellar rooms, and that some time back this room had been broken into and was now open, and as it contained china which was now exposed, the boxes in which it had been packed having been broken open, she wished to be relieved of the responsibility of having the key. I had the door closed, and also that of the garret, which I found had been broken open.”[65]

In the inventory prepared by McDowell, only two pieces of “States china” remained: “1 broken plate [and] 1 sugar bowl.”[66] Recognizing that “this place is not a safe one for the preservation of any-thing that is known to have an historical interest small or great,” he encouraged the removal of the Washington relics. While some items were transported to Tudor Place, others were taken to the United States Patent Office, where they were arranged and seen on public exhibition with the title “Captured from Arlington.”[67]

The Lees argued for the return of the relics from Arlington. Like her grandmother had in 1806, Mary Custis Lee provided the key provenance information needed for the Smithsonian Institution to inventory and facilitate the return of the relics by President McKinley in 1901. She continued the Custis family tradition of gathering, cataloging, and distributing the Washington objects as gifts offered to prominent people at strategic and diplomatic moments that negotiated her Washington and Custis lineage. Her curatorial actions were also motivated to reach the public eye with concerns for safety and international viewership, giving two pieces from the States service to the White House China Collection in 1917.[68] This gift was representative of what happened to many other pieces of the States service in the twentieth century, as they moved from private hands into public museum collections.

Mary Custis’s 1806 inventory of the States service provides new evidence about one of the largest, most elaborate, and perhaps most value-laden Chinese export porcelain hot-beverage services made for the American market. Analyzing the inventory provides the best evidence we have of the full range of forms represented in the service, which was large enough to serve tea, coffee, and hot chocolate or caudle as well as food to at least a dozen guests. The inventory also reflects the transformation of the service from luxurious but functional household objects into relics, conversation pieces best serviced to the family’s diplomatic moments, redolent of George and Martha Washington and the founding of the nation.

For assistance with this article, the authors thank George Washington’s Mount Vernon and the Fred W. Smith National Library for the Study of Mount Vernon, which generously granted Ron Fuchs a research fellowship that made this project possible, and especially Dawn Bonner, Kevin Butterfield, Sean Devlin, Susan Doyle, Adam Erby, Amanda Isaac, Susan Schoelwer, and Samantha Snyder. Hannah Boettcher thanks John McClure at the Virginia Museum of History & Culture, Kimberly Robinson at Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial (U.S. National Park Service), Melissa Naulin, the White House, and Grant S. Quertermous and Wendy Kail at Tudor Place for their guidance, expertise, and access to archival collections. We are grateful to Matthew Costello, Amy Hudson Henderson, and Cassandra Good for generously sharing their own research and knowledge.

The notebook, or commonplace book, containing this inventory is in the library at the Virginia Museum of History and Culture, owned and operated by the Virginia Historical Society. It survives as part of the family papers compiled by Mary Custis Lee (1835–1918), Mary Fitzhugh Custis’ eldest granddaughter. The inventory can be found in Mary Fitzhugh Custis, “Commonplace Book,” c. 1801–1806 [n.d.], Papers, 1694–1917, Mss. 1 L5144a 353–358, Virginia Historical Society, Richmond, Virginia.

The states are arranged roughly geographically, from north to south. In addition to the original thirteen states—Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, and Virginia—joined circles include Vermont, which became a state in 1791, and Kentucky, which became a state in 1792. Four years later, in June 1796, Tennessee became the sixteenth state to join the union. For a recent discussion on the “chain of states” motif in American currency, see Erik J. Goldstein and David McCarthy, “The Myth of the Continental Dollar,” Numismatist (January 2018): 49–55. Thanks to R. Scott Stephenson at Museum of the American Revolution for this citation.

Custis, “Commonplace Book.”

“Summaries,” Bulletin Van Het Rijksmuseum 53, no. 1 (2005): 89–95, available online at www.jstor.org/stable/40383574.

Ibid.; Tristan Mostert and Jan van Campen, Silk Thread: China and the Netherlands from 1600 (Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, 2015), pp. 153–55.

Susan Detweiler, George Washington’s Chinaware (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1982), pp. 151–58; Jean Gordon Lee, Philadelphians and the China Trade, 1784–1844 (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1984), pp. 81–82.

André Everard Van Braam Houckgeest, An Authentic Account of the Embassy of the Dutch East-India Company to the Court of the Emperor of China in the Years 1794 and 1795, 2 vols. (London: Printed for R. Phillips, 1798), 1:v–vi.

Detweiler, George Washington’s Chinaware, pp. 67–73.

Amanda Vickery, Behind Closed Doors at Home in Georgian England (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2009), pp. 14, 227–28.

Ibid.

J. A. Leo Lemay, “The American Aesthetic of Franklin’s Visual Creations,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 111, no. 4 (1987): 490–91.

La Feuille’s Devises et Emblemes was a popular emblem book in the eighteenth century and was the source of a motto included in a Chinese portrait of his wife that Van Braam commissioned while in China, suggesting that Van Braam had a copy or had access to one. Heinrich Offelen and Daniel de La Feuille, Devises et emblèmes, anciennes et modernes: Tirées des plus celebres auteurs, avec plusieurs autres nouvellement, inventées et mises, en Latin, en Francois, en Espagnol, en Italien, en Anglois, en Flamand et en Allemand (Amsterdam: Daniel de la Feuille, 1691), p. 45; “Summaries,” p. 91.

Mark Porny, The Elements of Heraldry: Containing a Clear Definition, and Concise Historical Account of that Ancient, Useful, and Entertaining Science (London: Printed for J. Newbery, 1765), p. 110.

Offelen and La Feuille, Devises et emblèmes, p. 4.

Detweiler, George Washington’s Chinaware, p. 151; Jean Gordon Lee, Philadelphians and the China Trade, 1784–1844 (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1984), pp. 151–58; Eleanor Gustafson, “Collector’s Notes,” Antiques 166, no. 4 (October 2004): 38–40. Another possible interpretation is that the inscription was meant to read “decus & tutamenin armis” (Honor and defense is in my arms). That motto is paired with a porcupine in the La Feuille’s Devises et emblèmes, which seems to have been the source of a motto that appears on a portrait of Van Braam’s wife that he commissioned in China. Offelen and La Feuille, Devises et emblèmes, p. 30.

Arlene Palmer, A Winterthur Guide to Chinese Export Porcelain (New York: Crown, 1986), p. 124.

The teapot cover (White House, acc. no. 1917.2751.2) can be seen on the sugar bowl in an 1880 photograph currently in the Smithsonian Institution Archives, Acc. 11-006, Box 014, Image No. MAH-4611, https://siarchives.si.edu/collections/siris_arc_391437.

Jean McClure Mudge, Chinese Export Porcelain for the American Trade, 1785–1835, 2d ed., rev. (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1981), p. 258.

William Milburn, Oriental Commerce: Containing a Geographical Description of the Principal Places in the East Indies, China, and Japan, with Their Produce, Manufactures, and Trade . . . 2 vols. (London: Black, Parry, 1813), 2:504.

C. J. A. Jörg, Porcelain and the Dutch China Trade (The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1982), p. 167.

Chocolate pot, New-York Historical Society (1972.11 a).

Custis, “Commonplace Book.”

Milburn, Oriental Commerce, 2:504.

Amanda Lange, Chinese Export Art at Historic Deerfield (Deerfield, Mass.: Historic Deerfield, 2005), pp. 250–53.

Ibid., p. 236.

The sugar bowl was confiscated from Arlington in 1862, recorded in a photograph in the National Museum (now the Smithsonian) ca. 1880, returned to Mary Custis Lee in 1901, and given by her to the White House in 1917 (acc. no. 1917.2751.1); Mount Vernon Relics, House of Representatives, Report No. 36, March 7, 1870, p. 3; “George Washington Relics,” Smithsonian Institution Archives, Acc. 11-006, Box 014, Image No. MAH-4611, https://siarchives.si.edu /collections/siris_arc_391437; and Melissa Naulin, “Creating a Room of Its Own: The Evolution of the White House China Room,” in Turning Points at the White House: Great Expectations, White House History Quarterly 53 (2019): 33; conversation with Hannah Boettcher, 2016.

Milburn, Oriental Commerce, 2:504.

Tea caddy made in Jingdezhen and decorated in Guangzhou, China, 1785 (Mount Vernon, W-3024/A),

John Sandon, The Ewers-Tyne Collection of Worcester Porcelain at Cheekwood (Woodbridge: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2008), p. 143.

The Derby factory, which was arguably the most exclusive porcelain manufactory in England in the 1790s, produced a range of covered two-handled cups that they described as being either for chocolate or for caudle; John Twitchett, Derby Porcelain: The Illustrated Dictionary, new ed. (Woodbridge: Antique Collectors’ Club, 1988), pp. 184–85, 280. The Sèvres factory made two-handled covered cups called gobelet à lait à deux anses couvert (“milk cup with two handles and cover”), which were used for restorative milky drinks intended for people who were ill, hungover, or otherwise run down; Rosalind Savill, The Wallace Collection: Catalogue of Sèvres Porcelain, 3 vols. (London: Trustees of the Wallace Collection, 1988), 2:667–69.

Oxford University Press Online, s.v. “caudle,” accessed July 19, 2020, https://www.oed.com/.

Benson John Lossing, Mount Vernon and Its Associations: Historical, Biographical, and Pictorial (New York: W. A. Townsend, 1859), p. 241.

Handled teacups were first made in European porcelain in the 1730s and began to be made in Chinese porcelain in the 1750s. Jörg, Porcelain and the Dutch China Trade, p. 186.

Savill, Wallace Collection, 2:496 and 527.

Milburn, Oriental Commerce, 2:504.

Mudge, Chinese Export Porcelain for the American Trade, p. 259.

The form, known as a gobelet litron, gets its name from a cylindrical measure for grain, salt, and peas; it was produced at Sèvres from at least 1752. Savill, Wallace Collection, 2:501–2.

Custis, “Commonplace Book.”

Winterthur Museum, acc. no. 1963.705.

Mount Vernon, acc. no. 2013.5.

Philippa Glanville and Hilary Young, eds., Elegant Eating: Four Hundred Years of Dining in Style (London: V & A Publications, 2002), p. 91.

Personal communication with Sean Devlin, Curator of Archaeological Collections, Mount Vernon, February 6, 2020.

Julian Niemcewicz, Under Their Vine and Fig Tree: Travels through America in 1797–1799, 1805, with Some Further Account of Life in New Jersey (Elizabeth, N.J.: Grassman, 1965), p. 104.

Starting in the 1800s, artifacts associated with the life and death of George Washington gained a national reputation as desirable “relics” on a “civic pilgrimage” to Mount Vernon, described by Matthew Costello, The Property of the Nation: George Washington’s Tomb, Mount Vernon, and the Memory of the First President (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2019), pp. 145–56, 173–75. Popularized by Lossing in the 1850s, the service became grouped with other Mount Vernon items known as the “Washington Relics,” “Mount Vernon Relics,” or “The Washington Treasury.” As the Washington, Custis, Lewis, and Peter families and others dispersed these items after Martha’s death, family members struggled to identify common names for specific decorative arts items within the group, making the family’s strategic notes on the histories of these objects even more remarkable and useful in researching their provenances; Julian Niemcewicz (1758–1841) to GW, June 14, 1798, The Papers of George Washington Digital Edition (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, Rotunda, 2008), https://rotunda.upress .virginia.edu/founders/GEWN-06-02-02-0253.

The will of Martha Washington states: “I give and bequeath to my Grand-son, George Washington Parke Custis all the Silver plate of every kind of which I shall die possessed, together with the two large plates Coolers, the four small plated Coolers with the Bottle Castors, and a pipe of wine if there be one in the house at the time of my death—also the Set of Cincinnati tea and table China, the bowl that has a ship in it, the fine Old China Jars which usually stand on the Chimney piece in the New Room also—all the family pictures of every Sort, and the pictures painted By his sister, and two small skreens worked one by his sister and the other a present from Miss Kitty Brown—also his Choice of—prints—Also the two Girandoles and Lustres that stand on them—also the new bed stead which I caused to be made in Philadelphia together with the bed, mattrass, boulsters and pillows and white dimity Curtains belonging therto; also the two other beds with bolsters and pillows and the white dimity Curtains in the New Room also the Iron Chest and the desk in my Closet which belonged to my first Husband; also all my books of Every Kind except the Large Bible, and the Prayer Book, also the set of tea China that was given me by W. Vanbram every piece having MW on it.” Will of Martha Washington, September 22, 1800, with codicil dated March 4, 1802, available online at https://www.mountvernon.org/education/primary-sources-2/article/the-will-of-martha-washington-of-mount-vernon/.

Arlington House now sits in Arlington National Cemetery. For more on this historical transformation during and after the American Civil War, including its social impact on the nineteenth-century communities that lived there, see Micki McElya, The Politics of Mourning: Death and Honor in Arlington National Cemetery (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2016), pp. 1–10.

They married on July 7, 1804, in the Fitzhugh’s townhouse at 607 Oronoco Street in Alexandria. For more on the Custis and Fitzhugh family histories, see Elizabeth Brown Pryor, Reading the Man: A Portrait of Robert E. Lee through His Private Letters (New York: Penguin Books, 2007), pp. 45–47 and 228–29; Tatiana Van Riemsdijk and the Dictionary of Virginia Biography, “Mary Lee Fitzhugh Custis (1788–1853),” in Encyclopedia Virginia, Virginia Humanities, January 18, 2017, available online at https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Custis_Mary_Lee _Fitzhugh_1788-1853#start_entry.

Arlington’s north wing was built first, in 1802. The south wing was built in 1803–4 in preparation for Custis’s wedding in July 1804. At the time of the inventory, Arlington might have looked similar to what artist William Birch possibly saw in September 1805, when Custis “had built the two wings of his capital house.” The center section was built 1817–1820. Julia King, George Hadfield: Architect of the Federal City (Farnham, Surrey, Eng.: Ashgate, 2014), pp. 118–21, 133.

Seth Bruggeman, “‘More Than Ordinary Patriotism’: Living History in the Memory Work of George Washington Parke Custis,” in Remembering the Revolution: Memory, History, and Nation Making from Independence to the Civil War, edited by Michael A. McDonnell, Clare Corbould, Frances M. Clarke, and Fitzhugh Brundage (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2013), p. 136; Murray Nelligan, Old Arlington: The Story of Arlington House, the Robert E. Lee Memorial (Burke, Va.: Chatelaine Press, 2001), pp. 127–28, 143, 161.

The attribution of the inventory to Mary Fitzhugh Custis is based on comparison of the handwriting to letters written from Custis to her husband and other family members, including an undated letter as “Mary Fitzhugh” written while courting “Mr. Custis” prior to 1804, Box 11, Cat. No. 434, Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial, National Park Service, Arlington, Virginia, and a letter to Ann Meade Page on June 16, 1810, Annefield Collection, Box 1, Folder 2, 1984.00154.001, Clarke County Historical Association, Berryville, Virginia.

There are two similarly-sized commonplace books kept by Mary Custis in Papers, 1694–1917, Mss. 1 L5144a 353–358, Virginia Historical Society. It is not known who “Rachel” is, but she is likely one of the women enslaved to the Custis family, perhaps the “Rachael” referenced in “An Inventory of the Slaves at Arlington belonging to the Estate of GWP Custis, taken January 1st, 1858,” in City of Alexandria Will Book 7, Microfilm, Library of Virginia. For an overview on slavery at Arlington, including genealogical research on George Washington Parke Custis’s children with women enslaved by the Custis and Washington families, see McElya, Politics of Mourning, pp. 14–16, 18–19, 25; and Pryor, Reading the Man, pp. 138–40.

New York Daily News, July 9, 1861, quoted in William Parker Snow, Lee and His Generals (New York: Richardson, 1867), 38. The wartime transfer of the relics from Arlington to the United States Patent Office was detailed by national press, such as in “Relics of the Washington Family,” Vermont Phœnix (Brattleboro), February 6, 1862.

Teresa Barnett, Sacred Relics: Pieces of the Past in Nineteenth-Century America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013), pp. 1–2, 21–23, 66–67, 73–75.

Cassandra Good, “Washington Family Fortune: Lineage and Capital in Nineteenth- Century America,” Early American Studies 18, no. 1 (2020): 90–133.

“Arlington and Mount Vernon 1856. As Described in a Letter of Augusta Blanche Berard,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 57, no. 2 (1949): 151–52.

Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton, Alexander Hamilton’s widow, was served dinner on the Cincinnati porcelain during a visit to Arlington in 1845. “A Relic of the Olden Time,” Alexandria Gazette, January 21, 1845; “States’ Porcelain Discovered,” https://www.nps.gov/arho/learn /management/arlington-house-rehabilitation.htm.

Good, “Washington Family Fortune,” pp. 116–17.

George Washington Parke Custis’s comment that it was made “especially for Genl. Washington” is incorrect; the service was made for Martha. Over the years the exact provenance of the States service was lost, confused, and conflated. Typescript of letter from George Washington Parke Custis to Professor Silliman, May 30, 1824, Mount Vernon Object File W 509. The saucer was later framed in an oak wreath, carved from wood from Connecticut’s Charter Oak, enhancing its identity as a relic redolent of the nation’s history. When the saucer came to the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association as a gift in 1921, the frame was removed and subsequently lost.

Covered cup and saucer, Mount Vernon Object File W-1497/A-C, with reference to Lafayette having been given a cup and saucer from the States service during his visit to Arlington in January 1825; Nelligan, Old Arlington, p. 168. Silliman’s visit to Arlington is mentioned in “Communications: Lafayette,” Daily National Intelligencer, August 21, 1824; Pryor, Reading the Man, pp. 39–44, 49–50. Silliman reported Trumbull’s gratitude to George Washington Parke Custis on August 13, 1824, in the Custis-Lee Family Papers, MS-5, Tudor Place Manuscript Collection, Box 1, Folder 7; George P. Fisher, Life of Benjamin Silliman, M.D., LL.D., Late Professor of Chemistry, Mineralogy, and Geology at Yale College, 2 vols. (New York: Charles Scribner, 1866), 1:310. Thanks to Amanda Isaac at George Washington’s Mount Vernon for this citation.

Martha Custis Williams to Miss Williams, April 1856, copy in Mount Vernon Object File W-1436/A-K.

Saucer, Mount Vernon Object File W-2803.

Mary Custis Lee to Mrs. L. M. Stiles, November 1, 1847, Archives of the Robert E. Lee Memorial Foundation, Papers of the Lee Family, Box 3, M2009.207.

Will of G.W.P. Custis, March 26, 1855, available online at https://www.encyclopediavirginia .org/Will_of_George_Washington_Parke_Custis_March_26_1855.

Mary Lee, quoted in Robert E. L. deButts Jr., “Mary Custis Lee’s ‘Reminiscences of the War,’” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 109, no. 3 (2001): 316–17.

“Mount Vernon Relics” Report, House of Representatives, 41st Congress, 2d Session, Report #36, p. 2.

Ibid., p. 3.

Ibid., pp. 1–2. For two examples, see “Relics of Washington,” Cincinnati Daily Press, January 15, 1862, available online at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84028745/1862-01-15 /ed-1/seq-1/; and The National Republican (Washington, D.C.), January 25, 1862, available online at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014760/1862-01-25/ed-1/seq-2/. For more on the relics’ locations, displays, and interpretation in public collections from 1862 to 1901, see Hannah Boettcher, Mary Custis Lee Unpacks the Washington Relics: A Revolutionary Inheritance in Museums, 1901–1918 (master’s thesis, University of Delaware, 2016). Britannia Peter Kennon recalled that some items were delivered by General Winfield Scott to Tudor Place in Georgetown in an undated later quoted by Grant S. Quertermous, ed., A Georgetown Life: The Reminiscences of Britannia Wellington Peter Kennon of Tudor Place (Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 2020), pp. 39–41, 176. Robert E. Lee Jr. recalled this title in Robert E. Lee Jr., Recollections and Letters of General Robert E. Lee, by (His Son) Captain Robert E. Lee (New York: Doubleday, 1904), p. 337.

Melissa Naulin, “Creating a Room of Its Own: The Evolution of the White House China Room,” Turning Points at the White House: Great Expectations, White House History Quarterly 53 (2019): 25–39, as photographed and discussed by Abby Gunn Baker, “Historic China of the White House: Part 1,” Arts and Decoration 16, no. 3 (January 1922): 195. As part of the Custis-Lee fa 0mily’s endeavor to reclaim the relics, Mary Custis’s eldest granddaughter, Mary Custis Lee (1835–1918), visited the Smithsonian to take inventory of items based on her memory of living at Arlington. Her notes were eventually corroborated by curators and Custis-Lewis cousins, see Boettcher, Mary Custis Lee Unpacks, pp. 98–103, 153, 168–75, and Theodore T. Belote, “Descriptive Catalogue of the Washington Relics in the United States National Museum,” Proceedings of the United States National Museum 49 (2092), 1915, pp. 1–24, 27, https://doi.org/10.5479/si.00963801.49-2092.1.