Artist unknown, The Old Abbey, Saarland, Germany, nineteenth century. Oil on canvas. (Courtesy, Keramikmuseum Mettlach.) This nineteenth-century oil painting illustrates the Old Abbey, which today houses the head administrative offices of Villeroy and Boch Company, its exhibition and salesrooms, and the historical displays of its Keramikmuseum.

Unknown artist, Eugen von Boch (1809–1898), undated. Oil on linen. (Collection of Wendelin von Boch-Galhau.) Boch was responsible for the creation of the Keramikmuseum in Mettlach around 1844.

Isaac Jacob (“Jake”) Gold, ca. 1870. (Photo courtesy of Ken Horner.) Born in New York, Gold moved with his family to Santa Fe when he was about nine years old.

Jake Gold’s Old Curiosity Shop and Free Museum, Santa Fe, New Mexico, ca. 1895. (Courtesy, Palace of the Governors Photo Archives [NMHM/ DCA], 011338; photo, William E. Hook.) The shop was located at the corner of West San Francisco Street and Burro Alley, where Gold’s brother Aaron had run a business with food, drygoods, and other merchandise to sell or trade for Native American wares.

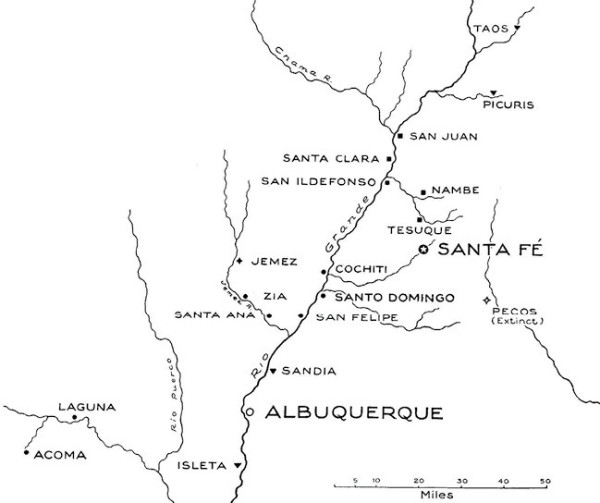

Map of a portion of northern New Mexico showing the locations of the sixteen pottery-producing Eastern Pueblos in the Rio Grande Valley, as well as two of the four Western Pueblos: Acoma and Laguna. Farther to the west are the Zuni Pueblo and, in Arizona, the Hopis. (Map by Charlotte Jacob-Hanson.)

Jug, Tularosa black-on-white, Ancestral Pueblo: Southern Colorado Plateau (Anasazi), ca. 1175–1300. Earthenware. H. 10". (Courtesy, Keramikmuseum Mettlach 146/555.) This jug is decorated with a spiral-and-stepped design with solid and hatched fill.

Aerial view over the village of Acoma Pueblo, in rocky landscape at dusk, New Mexico, United States, 2007. (Alamy Limited; photo, Adam Woolfitt.)

Water jar (olla), Acoma Pueblo, New Mexico, 1880–1890. Earthenware. H. 10". (Courtesy, Keramikmuseum Mettlach 117/526.) A polychrome-decorated olla with rounded shoulder and raised tapering neck, black on the rim and body with split leaves, diamonds, and flowers on a cream slip; black “fire cloud” on the lower portion.

Canteen, Acoma Pueblo, New Mexico, 1880–1890. Earthenware. H. 9 3/8". (Courtesy, Keramikmuseum Mettlach 118/527.) An Acoma pueblo polychrome canteen, with white clay and slip, painted with typical Acoma design elements in red and black: open ellipses, split parallelograms, and double dots (rain symbols).

Canteen, Acoma Pueblo, New Mexico, 1880–1890. Earthenware. H. 6 1/8". (Courtesy, Keramikmuseum Mettlach 119/528.) An Acoma pueblo polychrome canteen, white clay and slip, featuring a typical Acoma macaw parrot and black split leaves with an arc-like rainbow above the bird.

Canteen, Laguna or Acoma Pueblo, New Mexico, 1880–1890. Earthenware. H. 5 5/8". (Courtesy, Keramikmuseum Mettlach 120/529.) This unusually shaped canteen, possibly imitating the shape of a gourd, has decoration consisting of abstract leaves and parallelograms on two sections divided by a band in deep orange; the base is also colored in deep orange.

Canteen, Laguna Pueblo, New Mexico, 1880–1890. Earthenware. L. 12 1/2". (Courtesy, Keramikmuseum Mettlach 136/545.) This polychrome triple-chamber canteen, made of white clay, is decorated with large split-leaf petals outlined in brown on the outer sections and an ornament of split leaves in black painted in the center.

Bird effigy vessel, Acoma Pueblo, New Mexico, 1880–1890. Earthenware. H. 4 3/4". (Courtesy, Keramikmuseum Mettlach 123/532.) Archaeologists refer to this type of vessel as a “zoomorphic canteen.”

Double-headed bird effigy vessel, Laguna or Acoma Pueblo, New Mexico, 1875–1890. Earthenware. H. 4 1/4". (Courtesy, Keramikmuseum Mettlach 124/533.)

Bird-shaped pitcher, Santa Clara Pueblo, New Mexico, 1880–1890. Earthenware. H. 7 3/8” (Courtesy, Keramikmuseum Mettlach 150/559.) The shape of this blackware pitcher, with handle attached to the head and tail, possibly imitates a duck.

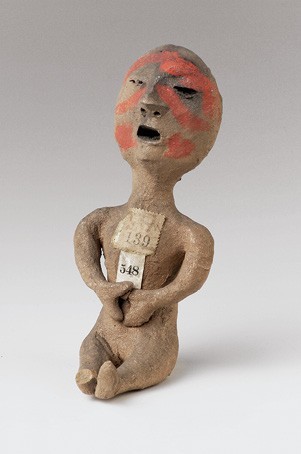

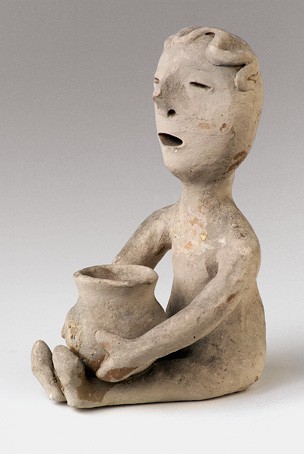

Three “idols” (rain gods), Tesuque Pueblo, New Mexico, ca. 1890. Earthenware. H. 6". (Courtesy, Keramikmuseum Mettlach 138/547, 139/548, and 140/549.) The center example is covered with a micaceous clay slip.

Three “idols” (rain gods), Tesuque Pueblo, New Mexico, ca. 1890. Earthenware. H. 6". (Courtesy, Keramikmuseum Mettlach 138/547, 139/548, and 140/549.) The center example is covered with a micaceous clay slip.

Three “idols” (rain gods), Tesuque Pueblo, New Mexico, ca. 1890. Earthenware. H. 6". (Courtesy, Keramikmuseum Mettlach 138/547, 139/548, and 140/549.) The center example is covered with a micaceous clay slip.

Three “idols” (rain gods), Tesuque Pueblo, New Mexico, ca. 1890. Earthenware. H. 6". (Courtesy, Keramikmuseum Mettlach 138/547, 139/548, and 140/549.) The center example is covered with a micaceous clay slip.

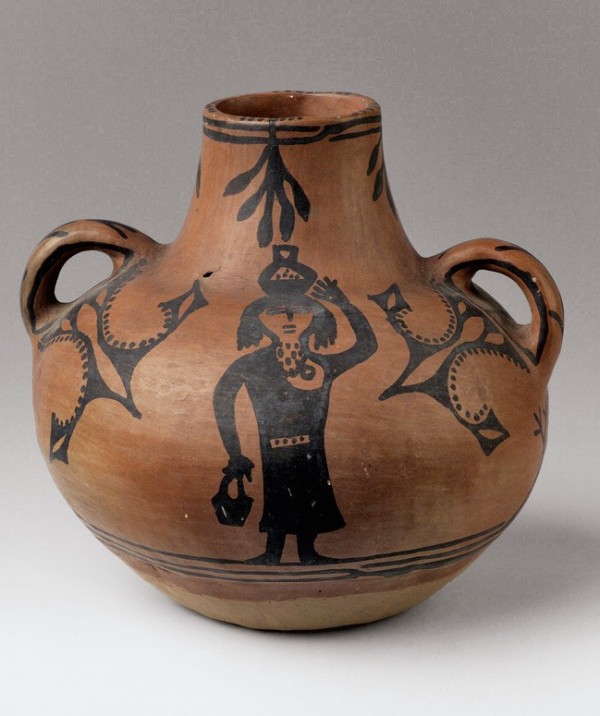

Standing figure, Cochiti Pueblo, New Mexico, 1875–1885. Earthenware. H. 12 1/4". (Courtesy, Keramikmuseum Mettlach 143/552.) A male figure with head tilted back and mouth open, arms akimbo, wearing painted vest and cowboy attire.

Effigy vessel, Cochiti Pueblo, New Mexico, 1880–1890. Earthenware. H. 7 1/8". (Courtesy, Keramikmuseum Mettlach 141/550.) This vessel, with painted decoration in black and red, was made for the tourist market.

Figure of a goat, Cochiti Pueblo, New Mexico, 1880–1890. Earthenware. H. 4 3/4". (Courtesy, Keramikmuseum Mettlach 142/551.) This object was made specifically for the tourist market.

Water jar (olla), San Ildefonso Pueblo, New Mexico, 1880–1890. Earthenware. H. 7 1/4". (Courtesy, Keramikmuseum Mettlach 145/554.) This polychrome olla is decorated with swirling sun symbols, somewhat resembling pinwheels, beneath a scalloped band. This piece was listed as a “San Ildefonso Olla—Speisetopf.”

Water jar (olla), San Ildefonso Pueblo, New Mexico, 1880–1890. Earthenware. H. 8 1/4". (Courtesy, Keramikmuseum Mettlach 135/554.) This jar has polished red slip and black decoration (black-on-red), depicting a female figure in a non-Native dress balancing a vessel on her head with a stylized bird symbol on either side.

IN 1894 A SHIPMENT of Southwestern Indian pottery arrived at the Keramikmuseum in Mettlach, Germany. According to an inventory notation, it was sent from a certain “Herr Gold” of Santa Fe, but little other evidence has survived to reveal the possible reasons for this unusual acquisition. Studying the story of the company’s special ceramics museum gave me a general understanding of the underlying purposes of its broad international collection. But since the story connects the Old World with the Old West, it was also important to explore that historic period in American history, when Santa Fe and the Rio Grande pueblos were being visited by scores of scholars, archaeologists, and ethnologists—both domestic and foreign—all eager to study Native peoples’ cultures firsthand and to collect or purchase ethnographic material. Important actors in this chapter of the story were two members of an immigrant Jewish family, the Golds, who founded a curio business in Santa Fe that catered to ethnologists and tourists alike. Their pottery curiosities were seen in European museums and at world exhibitions. It is likely that the Golds’ business connection with Villeroy & Boch came about through the company’s participation in 1893 at the Chicago world’s fair, which featured pottery from a “Mr. Gold” in Santa Fe.

The Founding of Villeroy & Boch in Mettlach,

and the Beginnings of Its Keramikmuseum

Jean-François Boch (1782–1858) was a third-generation member of the famous family that came from eastern France and founded an important ceramic business in Septfontaines, Luxembourg. In 1809 Boch acquired the abandoned Benedictine abbey in Mettlach (fig. 1), where he set about building an earthenware factory that would use the most modern mechanized production methods.[1] His father had sent him to study in Paris at the École des Sciences where he formed a friendship with Alexandre Brongniart (1770–1847), the future director of the Sèvres manufactory and the first curator of its famous ceramics museum. Their friendship of many years was to prove beneficial to both men. Jean-François soon began to recognize the value of keeping a collection of manufactured ceramic examples to serve as a creative visual stimulus for the company’s designers and decorators. By 1821 his collection consisted of European (mainly French) faience examples, as well as English earthenware, including a number of products from Wedgwood’s factory.

Boch was not the only ceramic manufacturer to pursue such a collecting project. Brongniart had been appointed director of the Sèvres porcelain manufactory in 1800, and energetically set about creating a study collection of ceramics that would satisfy both artistic needs and educational objectives, and thus would be beneficial both for Sèvres craftsmen and students in the field of applied sciences.[2] Jean-François Boch communicated with Brongniart about the study collection at Sèvres, and sent pieces of his company’s production to the Sèvres museum between 1804 and 1835.

Jean-François’s eldest son, Eugen (fig. 2), greatly increased the study collection begun by his father. A keen collector from his youth, Eugen made acquisitions during his travels and through donations, exchanges, or purchases using the services of art agents. In this way, many ceramic products of the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, and the Baroque and Historicism periods were added to specimens from non-European cultures. By 1844 Boch had installed the private collections in a special museum room in the Old Abbey, and by 1851 he was beginning to refer to it as his ceramic museum.[3] In addition to serving scientific purposes, the collection attracted visitors and became a growing visual reference source for designers who were working in the production of tableware and ornamental ware. Much of the production at this time reflected the artistic styles associated with Historicism.[4]

Eugen Boch had a particular penchant for Italy and the civilizations of the ancient world, and he became more than just a hobby archaeologist. Through his circle of friends, which included antiquarians and archaeologists, he informed himself about the most important Celtic and Roman finds in the immediate region. One certainly did not have to travel to Italy to find traces of the Romans: they founded nearby Trier around 16 b.c., and over the subsequent three centuries had transformed it into an imperial city. In 1852 the ruins of a large Roman villa were discovered in the village of Nennig, about twenty kilometers (approx. 12.5 miles) west of Mettlach. Archaeologists uncovered a magnificent mosaic floor, which Eugen Boch eagerly inspected.[5] His interest led to Villeroy & Boch being commissioned to restore the missing parts of the mosaic with ceramic tiles.

That task was completed by 1874, and it inspired the Bochs to take up the production of floor tiles as a new product division. Their mosaic factory in Mettlach, the first in Europe, opened in 1869 and was placed under the direction of Eugen’s elder son, René Boch (1843–1908), another gifted engineer. A second factory in Merzig was soon producing floor tiles as well as architectural and artistic terracotta on a grand scale.[6]

World’s Fairs

By the end of the 1870s, Villeroy & Boch was the most successful ceramics company in the world and employed nearly 7,000 workers. An important element of its international marketing strategy was participation at the major prestigious world’s fairs held in the second half of the nineteenth century—the Great Exhibition, London, 1851; Exposition Universelle, Paris, 1878; Weltausstellung, Vienna, 1873; Centennial Exposition, Philadelphia, 1876; Melbourne International Exhibition, Melbourne, Australia, 1881; Exposition Universelle d’Anvers, Antwerp, Belgium, 1885; and the Chicago Columbian Exposition, 1893, to name a few—and the company’s ceramic innovations and products won scores of medals and awards. World’s fairs highlighted the latest advancements in science and technology while giving recognition to the finest arts and craftsmanship. After 1870 Villeroy & Boch promoted the quality and advantages of its tile production for building projects, and in 1878 its architectural terracotta was used in the construction of the Palais du Trocadéro for the Exposition Universelle in Paris.

Across the ocean, the Chicago Columbian Exposition of 1893, marking the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s first voyage to North America, was a landmark event in many respects and has a special connection to this story. Built on 686 acres on the edge of Lake Michigan, the exposition hosted forty-six nations and was the largest world’s fair since London’s Great Exhibition. In addition to displays featuring the newest innovations in industry, agriculture, mining, and the liberal arts, it presented new perspectives on Native Americans, who had greater representation than any other cultural group: “A visitor could learn about American Indian life through displays of American Indian arts and crafts, and exhibitions of traditional and contemporary Indian life that could be seen in more than a dozen locations, including the Anthropology Building, the U.S. Government Building, the Canadian and Mexican pavilions, various South American exhibitions, and the Smithsonian Institution’s display.”[7]

This fair was the second of a series, starting with the Philadelphia Centennial of 1876, that brought the indigenous peoples of the Southwest to national attention, and it was the first to feature the scientific discipline of anthropology with its own building. Frederic W. Putnam (1839–1914), curator and director of Harvard University’s Peabody Museum of Ethnology, had been appointed to head the anthropology division of the Chicago fair and had spent much of the two years prior to it collecting photographs and natural history, ethnographic, and archaeological items for the exhibition.[8] Working under him was his chief assistant, Franz Boas (1858–1942), a noted German-born American anthropologist who was to greatly influence this growing scientific field.

Most of the Native American exhibits organized by Putnam and Boas were shown in four sections of the Anthropology Building, while the better-funded Smithsonian Institution could choose from its own abundant collections for the displays in the U.S. Government Building. A few published pictures of the glass cases displaying collections of Native American pottery from the National Museum (now the National Museum of Natural History) give some impression of the pottery treasures amassed during several Southwestern expeditions sponsored by the Bureau of Ethnology between 1879 and 1885 (those expeditions are described in more detail below).[9] Elsewhere on the fairgrounds were families of various tribal groups who had been invited to make their temporary homes at the exposition and demonstrate (in traditional costume) how their forefathers had lived. Putnam told reporters that the Chicago Columbian Exposition was an opportunity to create “a perfect ethnographic exhibition of the past and present peoples of America . . . with representatives of the peoples who were living on the continent when it was discovered by Columbus.”[10]

Archaeological finds, especially those in the west, especially caught the public imagination: one of the most popular privately operated exhibits, located near the Anthropology Building, was an artificial mountain seventy feet high that housed recently excavated pottery and utensils of the “Cliff Dwellers” from the Mesa Verde ruins in southwestern Colorado, plus other models of ancient Pueblo architecture in Arizona and New Mexico.[11]

Many Native American objects exhibited at international fairs in both Europe and the United States were afterward donated to public ethnographic museums. Even before the Columbian Exposition opened in May 1893, there were plans to create the Field Museum (to use its current name) in Chicago as a permanent home for the anthropology and natural history objects exhibited.[12] Among the objects that Putnam acquired for the anthropology exhibits were earthenware vessels made by the potters of the Acoma, Cochiti, and Tesuque Pueblos of the New Mexico Territory. Field Museum records indicate the vessels were sent by Jake Gold (1853–1905), the leading curio dealer in Santa Fe and the same man who sent a selection of Pueblo pottery to Mettlach for its Keramikmuseum in 1894.[13]

The Gold Family of Santa Fe

Isaac Jacob (“Jake”) Gold (1853–1905) (fig. 3) was the youngest son of Polish-Jewish parents who in 1851 had immigrated to New York City with three older children.[14] His mother’s paternal uncle, Joseph Hersch (1822–1901), was one of the earliest Jewish merchants in Santa Fe, having arrived in 1846.[15] Jake’s father, Louis Gold (1820–1880), traveled out west in 1852 to spend the winter in Santa Fe with Hersch, then returned to New York, repeating the journeys along the Santa Fe Trail several times in order to sell Indian goods (especially Navajo blankets) in New York and bring fancy goods back to Santa Fe for trade. By 1859 Louis had established a successful general merchandise business, and in 1867 formed a partnership with his sons Aaron and Abe, who had joined him from New York.[16] Even after Louis’s death in 1880, the business was in a phase of expansion, with growing demand for Pueblo cultural objects in a commercial market that soon extended well beyond New Mexico.

Aaron Gold (1845–1884), Jake’s elder brother, had worked in Santa Fe since 1875 as the owner of several stores and a saloon. In Gold’s Provision House near the corner of San Francisco Street and Burro Alley he sold not only groceries and supplies but also Pueblo pottery and other “curios.” He was the first trader to advertise the sale of Indian curios in local newspapers, and his first ad appeared in February 1880, just weeks after the final link of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe transcontinental railroad to Santa Fe had been completed, a development that soon brought increased tourism to the west and profoundly affected life and trade in the region.[17] Aaron advertised his store as “‘the only place in town where Rare Specimens of Indian Pottery, ancient and modern,’ could be had.”[18] He also had a local photographer make photos and stereoscopic views of his store and its pottery inventory, which he “probably mailed . . . to prospective buyers such as museums and curio dealers in larger cities.”[19]

A few documents and photographs from the period contribute important details to the story. Jake had joined his father and brothers in 1862, and in 1876 obtained his first business license, working for a few years as a viandante (itinerant merchant) among the Pueblos. According to the 1880 U.S. census, he was still living with Aaron and his wife, at least until he married later that year.[20] By May 1881 he had the financial means to lease six commercial rooms across the street from Aaron’s store on West San Francisco Street, which suggests he was convinced there would be enough business for two brothers to handle.[21]

In 1881 one of the earliest photographs of the corner entrance to the “Old Curiosity Shop” was made by the gifted and prolific photographer William Henry Jackson (1843–1942), who at that time had a photo studio in Denver and visited the Santa Fe area several times in the course of his expeditions.[22] His photo of the curio business showed the rickety wooden carreta (cart) on the roof over the doorway and the prominent sign facing the street—“J. Gold’s Free Museum” (also visible in fig. 4)—which indicates that Jake was already fully engaged in the curio business.[23] It was not uncommon for a curio dealer in the west to advertise his store as a “free museum,” as that encouraged railroad tourists as well as mail-order customers to visit.[24] Just whose idea it was to also dub it the “Old Curiosity Shop” is not clear, but it became one of the best known and most photographed sights in Santa Fe. For many years it was regularly written up in local papers, in national publications such as Harper’s Weekly, and in George Dorsey’s Indians of the Southwest, a handbook published in 1903 by the Fred Harvey Company for railway tourists.

Aaron’s publicity campaign and the photographs he presumably sent to museums and other curio dealers certainly paid off, judging from the list of prominent visitors and customers (some European), who came calling between 1880 and 1882. Swiss-born Adolphe Bandelier (1840–1914), one of the most important and influential historians and anthropologists in New Mexico during the nineteenth century, visited Aaron Gold in August 1880 (and in March 1882 had dealings with Jake, praising his collection of Indian goods in his journal).[25] President Rutherford B. Hayes and his wife visited Aaron’s store in late October 1880, at the end of their lengthy “Great Western Tour” of seventeen states, and bought some forty contemporary pottery objects from the Acoma, Cochiti, Zuni, Zia, and Tesuque pueblos (fig. 5).[26] In 1881 the French scholar and aspiring ethnologist Alphonse Pinart (1852–1911) came through Santa Fe and purchased a ninety-six-specimen collection of mostly Rio Grande Pueblo pottery from Aaron Gold, which he later donated to the Musée d’Ethnographie in Paris and is now in the Musée du quai Branly, Paris. Among the pieces he purchased from Gold were five “clay idols,” seated figures like those illustrated in his promotional photos.[27]

It is possible that Aaron Gold’s shop was also the source of a group of twenty-two “pottery figurines” bought in Santa Fe in June 1880 by members of the Smithsonian’s Bureau of Ethnology collecting expedition, who had been sent to the Southwest in August 1879. This was the first of three expeditions carried out between 1879 and 1885, and authorized by Major John Wesley Powell (1834–1902), bureau head in Washington, D.C.[28] Leading a party of four to gather examples of material culture from the pueblos (mainly pottery, both prehistoric and contemporary) was Col. James Stevenson (1840–1888). His report on the 1879 expedition was published in 1881, and on the last page, under “statuettes,” he mentioned “figurines of micaceous clay in various attitudes, representing both male and female . . . obtained in Santa Fe from traders.”[29] Back at the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., those figurines were entered into the accession book as “Earthenware Images, micaceous finish, obscene. Pueblo—Cochiti.”[30] They were described as “obscene” due to the exposed genitalia on some pieces, and probably for that reason no line drawings of them were made in the book.

Later comments on a file card noted that this type of clay (with the micaceous-slipped finish) was used by Tesuque Pueblo potters for similar figurines. The collected specimens were, in fact, antecedents of the rain gods that generations of Tesuque potters would soon be making by the thousands for tourists and mail-order businesses.

It was practical for the Gold brothers and local potters to use a barter system to trade Indian items for food and provisions instead of using cash. For the dealers it guaranteed a steady source of pottery, and it spared the Indians having to peddle door-to-door or sell on town plazas. As the Cochiti and Tesuque pueblos were closest to Santa Fe, developing trading relationships with them was the easiest. Their wares are abundantly represented in photographs and documented purchases before 1900.

With Aaron’s health declining (he died in 1884), Jake began managing the Old Curiosity Shop and Free Museum in 1881, and took over full ownership in 1883. His ads in the local newspaper often included his picture along with a description of his goods: “Dealer in Indian and Mexican Pottery (from Old Mexico), Ancient Montezuma Relics, Curiosities, Etc. All kinds of Indian made goods, Indian tanned skins, curious specimens from the CLIFF DWELLERS and thousands of articles found with no other dealer in America.”[31] He is also said to have used a few agents to find him pots of the “prehistoric” period, the time predating the arrival of the Spanish to the region in 1540. Of special interest to archaeologists and museums were vessels made by the Cliff Dwellers that were being discovered in the late nineteenth century from various ancient ruins scattered around the northern New Mexico territory and privately collected (fig. 6). For the next fifteen years Jake did business with curio dealers in Denver as well as El Paso, from whom he ordered pottery and textiles from Old Mexico, so that both his selection and market expanded, facilitated by the new railroad connections. Jake was also one of the first dealers to send out folding mail-order catalogs, of which just a few, from circa 1887, 1889, and 1892, have survived.[32]

All curio dealers advertised ancient relics supposedly dating to the age of Montezuma or that had been crafted by the Aztecs, and Jake Gold was no exception. But this now-debunked theory actually persisted for many years in government reports and other literature, was perpetuated by the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe and other travel advertisements, and even reinforced by the Pueblo Indians themselves from the 1840s to the 1880s, as Jonathan Batkin and others have pointed out.[33] Importantly, Bandelier’s writings served to discredit the Montezuma and Aztec theories while he laid out the evidence supporting the connections between the modern Pueblo peoples and their true ancestors, whom we now call the Ancestral Puebloans.

There are few remaining records or references about Jake Gold’s customers between the years 1883 and 1898. As mentioned, Gold sent Pueblo pottery to Chicago before 1893 for the Columbian Exposition, and the Field Museum has some documentation and most of those pieces. Because Villeroy & Boch also exhibited at this important event, it seems plausible that someone involved with that commercial project, or attending the fair, saw the various displays of Southwestern pottery and reported back to Eugen or René Boch about the anthropological and archaeological exhibits (with Indian pottery) that attracted large crowds. Villeroy & Boch had a sizeable space for their displays in the Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building, the largest structure of the exposition.[34] It was situated next to the U.S. Government Building, where the Department of the Interior had several displays of Indian objects. Jake Gold would certainly have sent a good supply of his catalogs along with his Indian pottery. Did one of them fall into the hands of a representative of Villeroy & Boch?

By 1878 Eugen Boch had retired and his son René (1843–1908) had taken over as director. This was just five years after the decision to formally transfer the entire family stock of collected ceramics (including archaeological artifacts collected by his father) to the company, and to establish a proper Keramikmuseum with an assigned annual budget for future systematic purchases. It is therefore not unreasonable to assume that René was the one who gave the approval to order the Indian pottery from Santa Fe, perhaps after receiving details about Gold’s business and/or a catalog. Had he possibly already come into contact with other Native American collections in Europe? And could those encounters have influenced his decision?

Pueblo Pottery in European Collections

During the final two decades of the nineteenth century, the Smithsonian had begun to help other museums across the country by “seeding” their collections with gifted objects, primarily duplicate pieces from its enormous holdings of Native American pottery and artifacts. In addition, it carried on a “specimen exchange” with foreign museums on nearly every continent, often exchanging Pueblo pottery and other ethnological objects for specimens desired from those museums.[35] The British Museum was sent such a gift in 1885, as was the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, the Musée du Trocadéro in Paris, and the Museum für Völkerkunde in Dresden (where Villeroy & Boch had its largest factory). The national ceramics museum in Sèvres, a suburb of Paris, held the largest European collection of world ceramics, and although it was not an ethnological museum, it nonetheless received several Pueblo pots in exchange for Sèvres porcelain.[36]

In the late nineteenth century several European scholars distinguished themselves by personally conducting fieldwork in the American Southwest in order to acquire Native artifacts, many of which they later donated to ethnographic collections in their home countries. Ethnographic salvage was the term given to their work. It was based on the commonly held perception that there was an “urgent need for investigating what remained of the traditional native cultures because the traditional ways . . . were on the brink of disappearing.”[37]

Like the aforementioned Alphonse Pinart from France, who visited Aaron Gold in 1881, most of the foreign scholars visiting America financed their journeys privately. The studious and widely traveled Dutchman Herman F. C. ten Kate (1858–1931) had the financial backing of his family, Dutch and foreign societies, as well as government funding with which he purchased Indian artifacts that he later donated to the National Museum of Ethnology in Leiden. After completing his studies in Paris, Leiden, and three German universities, Ten Kate undertook fieldwork in the American west, meeting nearly all the important personalities present in the “field” during his two visits between 1882 and 1888. His travel narrative (published in Dutch in 1885) and other papers have only recently become available in English, thanks to a former curator for North America at the Museum of Ethnology in Leiden.[38]

An important contribution to the studies of the Mesa Verde (Cliff Dweller) ruins was made by Gustaf Nordenskiöld (1868–1895), a Finnish-Swedish explorer, who traveled to southern Colorado in 1891.[39] He photographed and mapped the region belonging to the Wetherills, a ranching family with whom he stayed, and they permitted him to survey and carry out excavations at various ancient sites.[40] His excavation reports were published in 1893, in both Swedish and English, in his book The Cliff Dwellers of Mesa Verde, Southwestern Colorado: Their Pottery and Implements, a work still highly regarded today.[41]

Professor Gustaf Retzius (1842–1919), a Swedish physician, anatomist, ethnographer, and anthropologist, wrote a description of the skeletal remains from Mesa Verde excavated by Nordenskiöld and it was included in an appendix to The Cliff Dwellers of Mesa Verde.

Retzius was very involved in obtaining collections and specimens for the future ethnographic museum in Stockholm. He and his wife traveled to America in 1893 for six months to visit various scholars at eastern universities, followed by a visit to the Chicago Columbian Exposition. At the exposition they met Franz Boas, who had prepared many of the anthropological exhibits, and he recommended field contacts for the northwest coast of Canada as well as Jake Gold in Santa Fe as a good source for Pueblo pottery and Indian artifacts.

Retzius promptly traveled to Jake Gold’s Free Museum in Santa Fe, and purchased about thirty pieces of mostly contemporary Pueblo pottery, including Cochiti figures (seated rain gods and one standing figure), effigy vessels, large and small storage or water pots (Acoma), San Ildefonso black on redware, and Santa Clara blackware vessels. Except for some pieces that were later donated to the Swedish Royal Science Academy in 1919, most of the objects are still on view at the National Museum of Ethnography (Etnografiskamuseet) in Stockholm.[42] The Swedish collection resembles that in Mettlach in many respects, and the order for Villeroy & Boch’s Keramikmuseum cannot have been placed long after the visit of Retzius and his wife to Gold’s store. Gold’s inventory was evidently ample enough to supply his customers with prehistoric pieces as well as a representative selection of contemporary pottery from various pueblos. With no surviving documentation in Sweden, little more can be said about that collection.

Luckily, the Villeroy & Boch archives still have a late-nineteenth-century handwritten inventory, with one section listing the objects that Jake Gold had sent from Santa Fe, although no other invoices or correspondence survive. Whoever compiled the inventory was bilingual, translating the packing list information into German, with occasional French words interjected. The compiler wrote, “With the help of Pastor Schmitt our museum received in the year 1894 from the museum of Mr. Gold in Santa Fe in New Mexico the following American ceramic objects at the price of 430 marks” (my translation). The reference to “Pastor Schmitt” must be discounted if it referred to Pastor Philipp Schmitt, because he had died in 1856. Eugen Boch had admired the antiquarian Schmitt’s writings about his Celtic and Roman discoveries in the region, but that Schmitt cannot have been instrumental in helping with the order from Santa Fe, and no others by that name have been identified. The total cost, which included freight, insurance, and shipping charges, corresponds to 2,752 euros in today’s currency.[43]

Highlights from the Keramikmuseum: Prehistoric Pottery

The Pueblo Indians have lived in the American Southwest for millennia and their pottery-making traditions date back at least 1,300 years. Pueblo pottery can be separated into two general periods: “prehistoric”—that is, pre‑1540—before Spanish settlers came to the region; and “historic,” or post‑1540.[44]

It is now accepted that all Pueblo peoples are descended from the ancient people once called the Anasazi. But that name was used by the Navajo, who are not their descendants, and the actual meaning of the word is “ancient enemies.” Although still in use as a generic term for the early Pueblo sites and peoples, “Ancestral Puebloans” is preferred by the Pueblo Indians and has found wider acceptance.[45]

The designs on the jug illustrated in figure 6 are named after Tularosa, the site in New Mexico where the jug style was first identified and excavated.[46] But such vessels were widely traded in this early period and have been found all over the greater Four Corners region—the area defined by the modern-day southwestern corner of Colorado, southeastern corner of Utah, northeastern corner of Arizona, and northwestern corner of New Mexico—together with utilitarian grayware vessels that were used for cooking and food storage. Jake Gold sent a selection of both types to Mettlach.[47]

Pottery-building techniques have changed little throughout the centuries, and the vessels shown here, both old and newer, were all produced by the coiling and scraping method. Long, snakelike pieces of clay were rolled and coiled in a circular fashion onto a bowl-shaped base until the desired vessel height was reached. The vessel was then scraped and smoothed to form the desired shape using pieces of gourd or wood, erasing all signs of individual coils. After the clay was thoroughly dry, the vessel was rubbed smooth, sometimes slipped with liquid clay, and decorated. The black paint used for the designs was made from boiled plants (the Native potters still use beeweed or tansy mustard), and fibers of the yucca plant served as paint brushes, as they do today. The pots were fired in an open pit with wood as fuel (dried cow dung is often used nowadays).

A Selection of Nineteenth-Century Pueblo Pottery

Acoma Pueblo is located sixty-five miles west of Albuquerque. Its oldest section, called Sky City, is situated on top of a spectacular rocky mesa, 367 feet above the valley (fig. 7).[48] It is said to be the oldest continuously inhabited community in the United States, having been documented by the Spaniards of the Coronado Expedition that explored the area in 1540. All the settlements found in the region were called pueblos (“villages”) by the Spanish, and the term later came to refer to the inhabitants as well.

The residents of nearby Laguna Pueblo share much historically and linguistically with their Acoma neighbors.[49] Laguna pottery, especially of the circa 1870–1900 period, is difficult to distinguish from that of Acoma. Period photographs show Acoma and Laguna women standing at the railroad station in Laguna Pueblo, selling their ollas and other pots to tourists.[50]

The greatest number of Acoma and Laguna pottery specimens was collected by the Smithsonian field expeditions led by James Stevenson in 1883 and 1884–1885. The hundreds of line drawings made of the various water jars and vessels accessioned in those years are available online, and one can easily recognize the similarity of the decorations to those on Acoma and Laguna examples (figs. 8–14) in the Villeroy & Boch collection.[51]

For centuries the Acoma Indians grew corn in the plains surrounding their mesa and stored food in pottery vessels. On top of their mesa they collected fresh water in other vessels from natural cisterns formed between the rocks that captured rainwater and melting snow. Today those cisterns still exist and serve that purpose.[52]

Jars had to be easy to lift and had to balance firmly on the head of the bearer. Acoma and Laguna potters therefore made vessels of a size that would not be too heavy when full—roughly 10 inches tall by 12 to 13 inches in diameter. They formed necks with slight incurving depressions that fit the hand perfectly to allow easy handling when empty, and narrow mouths that inhibited both evaporation and spillage. . . . In the early eighteenth century, potters at Acoma and Laguna began to create vessels with concave bases, low centers of gravity, and outflaring shoulders to increase their stability.[53]

Two types of water canteens were made: larger ones for storing water in the home, and smaller ones that were used by men working in the fields or when traveling. The general shape was that of a bulbous body with a rounded base and a flattened back, a small cylindrical spout, and a pair of thick lug handles. The smaller canteens were suspended using leather, or a cord of either cotton or yucca fiber attached to the handles. Pueblo potters made pottery for their own use, but also as an item to trade to members of other pueblos or tribes. The canteen shapes shown in figures 9–12 also reflect the variety encountered by the Smithsonian collecting expeditions of 1879–1884. Pueblo potters began to increase their production of canteens when they noticed that collectors and local curio dealers were interested in buying or trading for them. The very fine triple-chamber canteen in figure 12 could have been made at Laguna Pueblo, where the orange-yellow coloring outlined in brown and the pinwheel motifs at either end were common.[54] The three-lobed form has a short spout in the center and bands in the depressions between the lobes where rope or leather straps would have been fastened.[55]

The Villeroy & Boch handwritten inventory identifies figures 9, 11, and 13 as Zuni objects, although today we know they are Acoma. Zuni clay is generally brown, whereas Acoma and Laguna clays are white and did not usually need the application of a white slip before the decoration was added. Moreover, the decoration on these pieces is typical for Acoma or Laguna. The faulty Zuni attribution might have been told to Jake Gold, or perhaps he made an error when he recorded them in the original paperwork.

The typical Acoma parrot or macaw seen on the Acoma canteen in figure 10 also appears on many Acoma ollas of the historic and modern periods. The feathers of macaws and parrots have been used for centuries in Pueblo rituals, but because these birds are not indigenous to the Southwest, their feathers had to be imported from Mexico. With their bright colors, macaws and parrots are associated with rainbows and hence with rain. This symbolism might relate to the use of these bird motifs on water jars and canteens.[56]

The Villeroy & Boch collection also has two double-headed bird effigy vessels (figs. 13, 14), called “Medicine Jugs” in the inventory list. The first was designated as Zuni, although the clay and design elements favor an Acoma attribution; the second could be either Acoma or Laguna. Birds that have two heads—“one open at the top or between the beaks, the other closed, were also collected at Acoma and Laguna in the 1870s and early 1880s. We do not know what these double-headed figures represent or were intended to convey or represent,” nor do we know whether these small vessels had a ceremonial use.[57] The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston has an Acoma duck effigy (acc. no. 1989.230) with a dried corncob for a stopper in the opening on the head (the same is found in the openings of some historic canteens).[58]

Jake Gold also included an unusual selection of seven Santa Clara blackware objects in his shipment to Mettlach. Their shapes differ noticeably from those in the Smithsonian collection, reflecting the Native potters’ response to the growing tourist market, which sought to purchase small, inexpensive objects they could easily transport on their train journeys.

The Villeroy & Boch collection includes five jugs or pitchers with handles, a plain flat dish, and an unusual pedestal dish that appears to imitate a Victorian glass shape (inv. nos. 127/536, 131/540, 144/553, 148/557, and 149/558).[59] Two of the jugs are clearly bird-shaped (fig. 15) and one other is a tapered jug with a bird head.[60] To date I have seen only one comparable example, in the Retzius collection (acc. no. 1904.19.0512) in Stockholm.[61]

Tesuque Pueblo is situated closest to Santa Fe, and for that reason it was selected by Santa Fe merchants as a source for tourist pottery items in the late 1800s. The most famous ones, first made in the late 1870s, were the Tesuque rain gods.

The prototypes, a number of which were purchased by the aforementioned Stevenson expedition in 1880 in Santa Fe, were seated males, some with exposed genitalia. The Santa Fe curio dealers probably encouraged the potters to start adding a clay vessel to the laps of these clay “idols” to make them more acceptable (and therefore salable) to tourists. Jake Gold is often given credit for this idea, and although documentary proof is lacking, Jonathan Batkin maintains that the Gold brothers must have played a role in the development of such figures, for “the only way [they could] have a constant supply of local goods for their shops was to invent some types of artifact, or to support the invention and production of them by their Pueblo suppliers.”[62] This happened in a period when adverse climatic conditions (drought interspersed with heavy rains and flooding) had made farming difficult at the Tesuque Pueblo, so the Native potters were willing to comply with requests from traders for “tourist art forms,” as author and rain-god expert Duane Anderson explains in his 2002 book When Rain Gods Reigned.[63]

During a visit to the Wheelwright Museum in Santa Fe in 1997, I showed Jonathan Batkin a picture of the three Mettlach figurines illustrated in figure 16. The following year he mentioned them in a publication and declared their importance for belonging to a very small number of pre-1900 examples that have survived with documentation.[64] He added that Jake Gold commonly assigned specific attributes and names to his Tesuque figurines. In the Villeroy & Boch inventory they are listed as “Pueblo God of Reason, Tesuque God [of] Pain, and Tesuque God of Water”—in each case a “mod(ern) Idol.”[65] Because they had arms with mitten-like hands that could be arranged to rest on various parts of the body, the figurines came to represent various ailments or have other symbolic meanings. Such names appeared in the 1882 catalog of a Denver curio dealer who did business with the Golds. He also saw the marketing potential of these curio items, and claimed that such figurines “were looked upon by the Indians as gods.”[66] Dealers played upon the curiosity (and ignorance) of their customers as much as they fed their preconceived notions about the Native American world.[67] For several decades these Tesuque figurines remained a commercial success, having been aggressively marketed by the Santa Fe Railway and curio dealers across the nation. The seated figure with a pot in its lap and its hands on the pot (as in the example at far right in fig. 16) became the most popular model, with the term rain god being in regular use from about 1905.

The potters of the Cochiti Pueblo, located about thirty-five miles southwest of Santa Fe, also contributed to the category of figural ceramics in the last quarter of the nineteenth century with their remarkable figurines between twelve and thirty inches in height. They were built from the feet upward by the ancient coil-and-scrape method and had to have open mouths so that gases could escape the hollow bodies during the firing, thus preventing breakage. (The Tesuque rain gods also had open mouths, but not for a technical reason.) The standing figurine (fig. 17) was listed in the Villeroy & Boch inventory as a “Cochiti God of Rain—Regengott, mod(ernes) Idol,” indicating that Jake Gold sold these figures as rain gods, too.

But the female Cochiti potters who created these figurines between ca. 1875 and 1905 were actually engaging in a clever form of parody and social criticism aimed at the wide range of newcomers to that part of the country—from the Spanish dons, priests, and Anglo-American men dressed as cowboys and merchants to the visiting opera singers and vaudeville or circus performers who came by train to Santa Fe.[68] Aaron Gold had dealt in and promoted these popular Cochiti figures too, as several photographs from the 1880s attest, but they were not mentioned or illustrated in curio catalogs of the period.[69]

At the end of the nineteenth century numerous American anthropol-ogists and art historians began to criticize the earthenware items that Pueblo Indians were being encouraged to make for the tourist trade. In particular, the idols and clay figures (rain gods) were called cheap and vulgar—“a debasement of the refined and artistic wares of the ancient Pueblos”—and argued that they could not be considered Native American art and did not belong in a museum, market, or exhibition.[70] Now that the rain gods have been given more scholarly attention, however, they are acknowledged as representing an uninterrupted 120-year tradition of figurative ceramic art in the Southwest.

Among the Tesuque and Cochiti pots sent by Jake Gold to Mettlach are several pieces quite similar to the types that had been collected at those pueblos in 1879, during the first Stevenson expedition to the New Mexico Territory.[71] One might have expected such objects (animals, miniatures, cups, pitchers, and covered or open pots with handles) to have been created in greater numbers only after the completion of the railway to Santa Fe, but as several authors have pointed out, the Rio Grande pueblos were already involved in a nascent curio trade during the 1870s.[72]

No pueblo made more effigy vessels in human, animal, and bird forms than Cochiti. The decoration on these novel pots includes clouds, rain and lightning, seedpods, corn plants, birds, and hunting scenes. One might assume that such vessels had some ceremonial significance, or were perhaps derived from older prototypes, but the fact that so many were produced, collected, and sold rather points to the influence of the Santa Fe dealers (like the Gold brothers) whose inventories offered dozens of them. Good examples can be seen in the Smithsonian and President Hayes collections as well as in the previously mentioned museums in Paris and Stockholm, the latter institutions having made their selections from the Gold brothers directly.

The gentleman in Mettlach who drew up the inventory for these objects can be forgiven for describing the handled pot illustrated in figure 18 as a “Cochiti Teekanne” (teapot); he more successfully identified the animal illustrated in figure 19 as a “Cochiti Pueblo Animal—Ziege” (goat).

The olla shown in figure 20, smaller than the Acoma example seen in figure 8, came from the San Ildefonso Pueblo, located twenty miles northwest of Santa Fe, and was probably used for storing dry food. In addition to the jug shown in figure 21, two other interesting San Ildefonso examples are in the collection, all with black-on-red decoration: one is a pear-shaped water vessel with an animal head at the apex (132/541); the other is a globular vessel with a handle, depicting two hummingbirds drinking nectar from flowers (137/546). Contemporaneous with the more usual black-on-cream design styles, this black-on-red type of decoration adopted by the potters became increasingly popular with tourists in the early 1880s.[73] The female figure illustrated in figure 21, trying to balance a jug on her head, is an amusing choice of motif on this well-shaped piece made for the tourist market.

By 1899, after years of celebrity in Santa Fe, Jake Gold was beset with legal troubles, lost his store, and was imprisoned for a little more than a year on charges of adultery. After his release in 1901 he went to work for the curio dealer J. S. Candelario (1864–1938), with whom he had corresponded while in jail. They set up a new business just a few doors east of Gold’s old location on San Francisco Street by joining two adjacent commercial buildings and putting a rickety old cart on the roof to give it a familiar landmark, and it was advertised in newspapers as “The Original Jake Gold Curio Store.”[74] The working relationship with Candelario did not last long and was severed in 1903. Now suffering from poor health (infirmities), Gold was committed to the Territorial Insane Asylum at Las Vegas, New Mexico, where he died in 1905.

During 1905 and 1906 in Mettlach, an impressive new museum was being built in the Old Abbey with a reorganization of the collections, supervised by René von Boch. But in a few years two world wars would change the political landscape and the fortunes of the company, as hostilities had done countless times in the past.[75] The Old Abbey suffered damage from an attic fire in 1921 and by bombs that fell during World War II, but the most harrowing story related to the collections involved their movement during 1939 and 1940. Due to the proximity of wartime activities in September 1939, the entire museum had to be packed up in 120 wooden transport crates, each weighing three to four tons, and evacuated from Mettlach to the company’s branch in Dresden. Somewhat miraculously, they were brought back to Saarland in June 1940 before the bombing of Dresden in 1945.

After being housed in nearby Schloss Ziegelberg since 1979, the Keramikmuseum was moved back to the Old Abbey in 2000, and part of it was installed in the Erlebniszentrum that opened in 2002. Today the company's collection representing 250 years of Villeroy & Boch production totals more than 17,000 pieces, and together with the international objects the holdings number about 30,000 pieces.[76]

Charlotte Jacob-Hanson lives in Germany and is an independent researcher of ceramics, as well as an author and lecturer.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For their advice and generous support of this project, I wish to thank the following: Duane Anderson,

former director of the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture, Santa Fe; Alexander Anthony Jr., Adobe Gallery, Santa Fe; Jonathan Batkin,

Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian, Santa Fe; Gloria J. Fenner, formerly of the Western Archaeological and Conservation

Center, National Park Service, Tucson, Arizona; Eta Erlhofer Helten; Christa Grund, Villeroy & Boch; Ken Horner; Pieter Hovens, former curator of the North American collection at the National Museum of World Cultures, Leiden, Netherlands; Ira Jacknis, Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley; Catherine A. Nichols, Loyola University, Chicago; Diana Pardue, Heard Museum, Phoenix; Nancy Parezo, University of Arizona, Tucson; Helen Robbins, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago; Ester Schneider, Managing Director, Keramikmuseum Mettlach of Villeroy & Boch; Martin Schultz, Intendent Nordamerika, Statens museer för världskultur, Stockholm; and Frank Usbeck, Kustos der Amerikasammlungen, Museum für Völker-kunde, Dresden.

For a more detailed history of the Villeroy & Boch company, see Charlotte Jacob-

Hanson, “A Brief History of Villeroy & Boch and England’s Influence on Its Success in the Years 1766–1900,” Northern Ceramic Society Newsletter, no. 198 (August 2020), pp. 40–47.

Brongniart developed a considerable network of contacts (collectors, museum and manufactory directors, diplomats, and organizers of international exhibitions) from whom he acquired pieces or whole collections. For an excellent summary of the collections of the Musée national de la Céramique formed before 1847, see Silvie Millasseau, “Brongniart as Taxonomist and Museologist: The Significance of the Musée Céramique at Sèvres,” in The Sèvres Porcelain Manufactory: Alexandre Brongniart and the Triumph of Art and Industry, 1800–1847, ed. Derek E. Ostergard (New Haven: Yale University Press for the Bard Graduate Center for Studies in the Decorative Arts, 1997), pp. 123–47.

Roland Mönig, Inspiration Antike: Eugen von Boch und die Archäologie im 19. Jahrhundert (Darmstadt: Philipp von Zabern Verlag, 2016), pp. 83, 84. Although the original paperwork regarding those acquisitions has not survived, at least three inventories (compiled in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries) offer some descriptive commentary on the objects in cupboards or showcases of the museum.

Eugen Boch’s collected vessels and archaeological purchases from his travels through Italy provided impulses and models for the production of neoclassical ceramics in Mettlach. For vase examples, see Carola Reinsberg, ed., Antike à la Carte: Meisterwerke des Klassizismus aus Neapel (Saarbrücken: Archäologisches Institut der Universität des Saarlandes, 2006), pp. 38–41, 88–91.

The villa had been built by a wealthy Roman on the road between Trier and Metz in the third century a.d. For more information, see http://etc.ancient.eu/photos/roman-villa-

nennig/.

The demand for floor tiles grew steadily: in 1870 Mettlach tiles accounted for a full 60 percent of the company’s sales, and by 1904 the company had carried out prestigious flooring projects in Cologne Cathedral and Moscow’s Bolshoi Theater, as well as in dozens of structures elsewhere in Europe and in the Americas. See Rainer Desens, Villeroy & Boch: 250 Years of European Industrial History, 1748–1998 (Mettlach: Villeroy und Boch, 1998), pp. 71–81, 115–19, 140–43.

Evan M. Maurer, “Presenting the American Indian: From Europe to America,” in The Changing Presentation of the American Indian: Museums and Native Cultures, ed. W. Richard West (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2000), pp. 21–23.

For an excellent reference covering the history of American anthropology, the expeditions, and the main actors in the field as well as in the museums and institutions of the nineteenth century, see Don D. Fowler, A Laboratory for Anthropology: Science and Romanticism in the American Southwest, 1846–1930 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2000). Fowler also describes the major fairs and exhibitions that displayed Native American artifacts and material culture.

See Hubert Howe Bancroft, The Book of the Fair: An Historical and Descriptive Presentation of the World’s Science, Art, and Industry, as Viewed through the Columbian Exposition at Chicago in 1893 . . . , 2 vols. (Chicago: Bancroft, 1893), chap. 7, 1:111, 114, available online at http://columbus.iit.edu/bookfair/00064016.html.

Quoted in Fowler, Laboratory for Anthropology, pp. 207–11. This world’s fair aimed to convey a positive picture of the nation’s progress after four centuries of expansion. The anthropological exhibits were designed to confirm the evolutionary superiority of white male society over that of the indigenous peoples; reconstructions of Native American villages contrasted starkly with the towering exposition buildings of the “White City,” as it was called. More contemporary exhibits illustrated the efforts to reeducate and assimilate the Native American populations into the white man’s society. On the edge of the fair, but not part of it, was Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show, perpetuating the myths of “savage” Indians and how the white man “won the West.”

See http://columbus.iit.edu/dreamcity/00034013.html; and Fowler, Laboratory for Anthropology, pp. 83–84, 191, 210 and n. 54.

On June 2, 1894, the Field Columbian Museum of Chicago opened to the public in the one remaining structure of the world’s fair, the Palace of Fine Arts Building in Jackson Park. The museum underwent several name changes honoring its first benefactor, Marshall Field, who donated $1 million to expand its collections. The new museum opened in 1921 in its present Grant Park location.

One of three Acoma storage pots sent to Chicago by Jake Gold is illustrated, along with a link to the original file card, at https://collections-anthropology.fieldmuseum.org

/catalogue/1387082. Six more storage or water jars (Acoma and Cochiti) in the Field Museum are illustrated in Jonathan Batkin, The Native American Curio Trade in New Mexico (Santa Fe, N.M.: Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian, 2008), pp. 48, 49.

Additional genealogical information and photos can be found at the Gold Family Genealogy website, https://hornergenealogy.com/, compiled by Ken Horner, a descendant.

Santa Fe’s early Jewish community is described in David S. Koffman, “Jews, American Indian Curios, and the Westward Expansion of Capitalism,” in Chosen Capital: The Jewish Encounter with American Capitalism, ed. Rebecca Kobrin (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2012), pp. 169–72.

Despite the growing Jewish community in Santa Fe, Louis’s wife, Mary (Miriam), did not wish to live in a place where practicing the dietary laws of her religion (and finding suitable Jewish spouses for her sons and daughters) would be difficult. All of her sons had to return to New York City to be married to suitable Jewish girls, who then moved back with them to Santa Fe. Mary and Louis were divorced in 1862, the year Jake joined his father and brothers in Santa Fe.

Kathleen L. Howard and Diana F. Pardue, Inventing the Southwest: The Fred Harvey Company and Native American Art (Flagstaff, Ariz.: Northland, 1996), give an excellent account of the partnership between the Santa Fe Railway and the Fred Harvey Company and how they provided safe, swift, civilized travel to the Southwest for more than half a century. Passengers to Santa Fe traveled the last eighteen miles on a spur line from Lamy (formerly Galisteo Junction).

Batkin, Native American Curio Trade in New Mexico, p. 23.

Jonathan Batkin, comp. and ed., Clay People: Pueblo Indian Figurative Traditions (Santa Fe, N.M.: Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian, 1999), pp. 49–51, including two photos of Aaron Gold’s inventory, ca. 1880. For another photo of Aaron posing in front of his store, see https://pogphotoarchives.tumblr.com/search/aaron+gold.

Jake returned to New York to marry Lizzie Cohen, daughter of Wolff Cohen and Bertha Hirsch, on September 12, 1880, and brought her to Santa Fe. They had no children.

Company documents dating from these years are scarce, but Jonathan Batkin of the Wheelwright Museum in Santa Fe writes, “Aaron claimed that in May 1880 alone he shipped $800 worth of Indian pottery to the East.” See Batkin, Native American Curio Trade in New Mexico, p. 29.

After extensive travels William Henry Jackson became a partner in the Detroit Photographic Company (later Detroit Publishing Co.), where his negatives became the basis for the company’s postcard and photographic view business. For the colorized postcard version of Jackson’s original 1881 photo, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jake_Gold%27s_Old_-Curiosity_Shop#/media/File:Postcard_1897- Detroit_Photographic_Company.jpg .

“Established 1862” probably refers to the year of Jake’s arrival in Santa Fe. Another 1881 Jackson photo showing Native Americans unpacking pots and objects they had brought to sell or trade to Aaron or Jake Gold can be seen at http://www.palaceofthegovernors.org/lens

/photos.php?view=detail&id=39.

As explained in Jonathan Batkin, “Tourism Is Overrated: Pueblo Pottery and the Early Curio Trade, 1880–1910,” in Unpacking Cultures: Art and Commodity in Colonial and Postcolonial Worlds, ed. Ruth B. Phillips and Christopher Steiner (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), pp. 282–88.

Bandelier “acquired much of his Harvard University collection of antiquities from Gold and another prominent Santa Fe dealer . . . and later assembled a similar collection for the Berlin Museum.” See Edwin L. Wade, “The Ethnic Art Market in the American Southwest, 1880–1980,” in Objects and Others: Essays on Museums and Material Culture, History of Anthropology, ed. George W. Stocking Jr. (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1985), p. 171.

These are currently kept in the Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Library and Museums, Spiegel Grove, Fremont, Ohio, and the collections can be viewed online, although the pueblos are not identified. One Cochiti effigy vessel is shown at https://rbhayes.pastperfectonline.com/webobject/913DE3F6-3F87-4432-AFA1-137521122819.

Discussed and pictured in Duane Anderson, When Rain Gods Reigned: From Curios to Art at Tesuque Pueblo (Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press, 2002), pp. 56, 57. For a discussion of other examples of early clay idols sold in this period, many of which are in European museums, see ibid., pp. 51–55, 58–65. A number of the objects, mainly Cochiti, donated by Pinart, were first given to the Trocadéro Museum of Ethnology, but today are in the Musée du quai Branly–Jacques Chirac, Paris, http://www.quaibranly.fr.

For detailed background regarding these expeditions, see Fowler, Laboratory for Anthropology, pp. 104–15, as well as Nancy J. Parezo, “The Formation of Ethnographic Collections: The Smithsonian Institution in the American Southwest,” Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory 10 (1987): 10–35. Parezo describes the collecting methods, how leaders bartered for objects, transported them, and later used some of them for display at international fairs or for trade with other museums and institutions.

Stevenson’s “Illustrated Catalogue of the Collections Obtained from the Indians of New Mexico in 1879,” in Second Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1880–’81, comp. John Wesley Powell (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1883), pp. 307–422, can be viewed online at https://ia800302.us.archive.org/9

/items/illustratedcatal18736gut/18736-h/18736-h.htm#item39928. In 1879 and 1880 the party visited the pueblos of Zuni, Hopi, Laguna, Acoma, Cochiti, Santo Domingo, Tesuque, Santa Clara, and San Juan, as well as prehistoric sites such as Canyon de Chelly in Arizona.

The Smithsonian Institution has made available online most of the records for these Southwestern artifacts collected between 1879 and 1885 (e.g., accession books with line drawings, card file notes, and photographs kept in the National Museum of Natural History).

Batkin, “Tourism Is Overrated,” p. 288.

Jonathan Batkin, “Mail Order Catalogs as Artifacts of the Early Native American Curio Trade,” American Indian Art Magazine, no. 2 (2004): p. 48 ill.

Batkin, Clay People, pp. 52–55. See also Richard Ellis, “The Changing Image of the Anasazi World in the American Imagination,” in Anasazi Architecture and American Design, ed. Baker H. Morrow and Vincent Barrett Price, 16–21 (Santa Fe: University of New Mexico Press, 1997).

Shown in Bancroft, Book of the Fair, p. 196, and http://columbus.iit.edu/bookfair

/1500/00064098.jpg.

Some of these are listed in Catherine A. Nichols, “Museum Networks: The Exchange of the Smithsonian Institution’s Duplicate Anthropology Collections,” Ph.D. diss., Arizona State University, 2014, pp. 2–3, 649–55.

Marie-Chantal de Tricornot, “Céramiques des Amériques à Sèvres: Les collecteurs et leurs intermédiaires,” Revue de la Société des amis du musée de Céramique 22 (2013): 26–67. The first shipment in 1885 never arrived, but another was sent in 1887. Today the museum houses a collection of more than fifty thousand ceramic objects from around the world (10 percent of which were made at Sèvres).

Pieter Hovens and Louis A. Hieb, “The Science of the Indians. Herman ten Kate, Anthropology, and Native American Studies,” in Herman ten Kate, Travels and Researches in Native North America, 1882–1883, trans. and ed. Hovens, William J. Orr, and Hieb (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2004), p. 15.

An excellent summary is in the introduction to Pieter Hovens and Bruce Bernstein, eds., North American Indian Art: Masterpieces and Collections from the Netherlands (Altenstadt, Germany: ZKF, 2015), pp. 3–14.

Fowler, Laboratory for Anthropology, pp. 189–92.

The Wetherills loaned a selection of excavated Mesa Verde pottery and artifacts to the Chicago Columbian Exposition of 1893, along with a few of Nordenskiöld’s photographs, helping to make the ruins better known.

There was resentment about the Wetherills’ commercial exploitation of archaeological sites in the general area, which only invited “archaeological tourism.” But locals also objected to Nordenskiöld, a foreigner, being allowed to mine the landscape and send crates of artifacts and human remains back to Sweden. These were later transferred to the National Museum of Finland in Helsinki, where they remained for nearly a century, until 2019, when they were returned to Native peoples in southern Colorado for reburial. Cliff dwellings such as Mesa Verde were not federally protected until 1906, when Congress enacted the Antiquities Act, which provided for the protection of historic and cultural sites, and made the removal of any artifacts illegal.

For a selection of the pottery on display, see http://collections.smvk.se/carlotta-em

/web/object/1444660/REFERENCES/334. See also Staffan Brunius, “North American In-

dian Collections at the Folkens Museum-Etnografiska, Stockholm,” European Review of Native American Studies 4, no. 1 (1900): 29–34.

One guidebook on the Villeroy & Boch collection indicates that the objects from the Americas, including those from Mexico and Peru, were sent together from Santa Fe. It is doubtful that Jake Gold had Peruvian objects for sale, but they might have been acquired through dealers in or closer to Mexico. Remarks in [Reinhold Junges], Dreitausend Jahre Töpferkunst: Ein Rundgang durch das Keramische Museum von Villeroy & Boch, Mettlach (1937), p. 5 (unnumbered).

Some sources date prehistoric pieces to before 1600; pieces of the historic period fall into two categories: “early” (ca. 1700–1880) and “late” (1880–1940). The critical events that influenced new pottery types and styles were the advent of the railroad in 1880, and the resulting new tourist market.

Linda S. Cordell, Ancient Pueblo Peoples (Montreal: St. Remy Press; Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books, 1994), pp. 18–20. See also “Ancestral Puebloan,” American Southwest

Virtual Museum, at http://swvirtualmuseum.nau.edu/wp/index.php/cult_land/archaeological-

cultures/ancestral-puebloan/. By ca. 1300 the Ancestral Puebloans had abandoned their canyon homelands in the greater Four Corners region due to social upheaval and climate change, and migrated to other areas, settling mainly in the Rio Grande river valley but also as far away as Acoma, Laguna, Zuni, and the Hopi mesas.

Three other Ancestral Pueblo jugs (156/565, 157/566, 158/567) and one bowl (159/568) are in the Villeroy & Boch collection.

In a personal communication to me in 1998, Jonathan Batkin wrote, “In his 1889 catalog Gold stated that his prehistoric pots came from ruins that were specifically 28 miles from Santa Fe. I don’t know if he was referring to ruins at Pecos, ruins in the Galisteo Basin, or ruins on the Pajarito Plateau, such as those at Bandelier or Puye. . . . Once Wetherill and his buddies found sites in the Mesa Verde area, they were mined for artifacts, and at least a few mail-order and auction catalogs of the 1880s and 1890s offered them.” As for utilitarian wares, Gold sent three Mogollon corrugated bowls used for cooking (160/569, 161/570, 162/571), one pot corrugated at the neck (163/572), and a Mogollon Fillet Rim Bowl (162/571), all dating to a.d. 700–1050. All of these were fired upside down, causing the interiors to turn black. There were about twelve other objects from “Alt-Mexiko” listed in the Villeroy & Boch inventory as well.

The historical background of the Spanish settlement of New Mexico, the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 and its consequences for the indigenous peoples, as well as a thorough discussion of pottery and designs can be found in Rick Dillingham, Acoma and Laguna Pottery (Santa Fe, N.M.: School of American Research Press, 1992).

With increased railway advertising (mainly through Fred Harvey posters, postcards, and publications), visiting tourists were keen to buy directly from the potters. See note 17 above. Since the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway line made a daily stop at Laguna Pueblo, tourists could take a break, get off the train, and purchase souvenirs from the potters (both Acoma and Laguna). For a period photograph, see https://commons.wikimedia.org

/wiki/File:New_Mexico_-_Pueblo_Indians_Selling_Pottery_(NBY_431722).jpg.

For a similar Acoma olla in the Smithsonian collection, and the corresponding page in the accession (ledger) book with a line drawing, see http://collections.si.edu/search/detail

/edanmdm:nmnhanthropology_8328616?q=acoma&fq=online_media_type%3A%22

Images%22&fq=object_type%3A%22Pots+%28containers%29%22&record=183&hlterm

=acoma&inline=true.

In 1904 the photographer Edward S. Curtis (1868–1952) visited the pueblo and took one of his most famous photos, At the Old Well of Acoma, showing a young Acoma woman dipping her olla in the cistern for water while a companion looks on. See http://curtis

.library.northwestern.edu/curtis/viewPage.cgi?showp=1&size=2&id=nai.16.port.0000029

.p&type=po rt&volume=16.

Dillingham, Acoma and Laguna Pottery, p. 67.

Betty Toulouse, “Pueblo Pottery Traditions: Ever Constant, Ever Changing,” El Palacio (Quarterly of the Museum of New Mexico) 82, no. 3 (1976): 14–22.

Also in the Mettlach collection are another Acoma canteen with a checkered geometric design (122/531) and a handled Acoma pitcher or jug (121/530, listed as Zuni).

Dillingham, Acoma and Laguna Pottery, pp. 98–99, 102. Another fine example of an 1880s Acoma olla decorated with these motifs is in the Art Institute of Chicago (2006.749), https://www

.artic.edu/artworks/189293/polychrome-jar-with-rainbow-macaw-and-floral-motifs.

Dwight P. Lanmon and Francis H. Harlow, The Pottery of Acoma Pueblo (Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press, 2013), pp. 317–18.

See https://collections.mfa.org/objects/41810/duck-effigy?ctx=4ae46666-01fb-4c01

-9927-1f36eae9a1bf&idx=4.

The shapes of these black Santa Clara wares are imitative of the brass, glass, or ceramic shapes of objects in use by the Anglos. Around 1880 “Santa Clara’s undecorated blackware became small in size and varied in shape: cream pitchers, vases, cups, candle-sticks, dishes, bird and animal figurines . . . [their] condiment jars and sugars and creamers became tableware staples in Hispanic and Anglo households during the later years of the century. Until the 1930s, well-made and well-fired Santa Clara blackware could hold water.” Allan Hayes and John Blom, Southwestern Pottery: Anasazi to Zuni (Flagstaff, Ariz.: Northland, 1996), p. 130.

Although illustrated as “Mexican” in Junges, Dreitausend Jahre Töpferkunst, p. 7 (unnumbered), in the Villeroy & Boch list it is a “Santa Clara Pitscher—Schnauzkrug” (bird-jug with an accentuated spout, 147/556).

See http://collections.smvk.se/carlotta-em/web/object/1266837.

Batkin, Native American Curio Trade, p. 33.

For several examples in European museums, see Anderson, When Rain Gods Reigned, pp. 47–48, and 51–65. A considerable variety has been found in the collections of more than seventy-five museums around the world.

Batkin, Clay People, p. 56.

There are also seated gods of bellyache, hunger, choking, love, war, peace, plenty, and advice, and so forth with arms in varied poses, as explained in Anderson, When Rain Gods Reigned, pp. 62–63. Figure 16 (far left) had the German phrase “Gott der Vernunft” next to an indecipherable word in the inventory list. I have translated it as “God of Reason” here.

An advertisement in this 1882 catalog is shown in Batkin, “Tourism Is Overrated,” p. 296.

Ibid., p. 288. Jake Gold seems to have been a master showman in this respect, and is remembered for spinning tall tales to visiting customers regarding the “ancient relics” in his inventory. In an 1894 newspaper article, one visiting reporter recalled: “[Here] you can purchase the last pair of trousers worn by Columbus, the sword De Soto wore, the hat of Cabeza de Vaca or the breastplate worn by Cortez.”

See Batkin, Clay People, pp. 13, 42–56, 59; and Anderson, When Rain Gods Reigned, pp. 23, 64–65.

See Batkin, Clay People, pp. 13, 42–56, 59; and Anderson, When Rain Gods Reigned, pp. 23, 64–65.

Anderson, When Rain Gods Reigned, pp. 21–25.

See note 29 above. Also in the Villeroy & Boch collection are a Tesuque covered pot with handles (126/535), a spouted jug or pitcher (133/542) that was said to be from San Felipe Pueblo, and a small Cochiti handled basket (134/543).

Batkin, Native American Curio Trade, p. 32; Fowler, Laboratory for Anthropology, p. 345.

Toulouse, “Pueblo Pottery Traditions,” pp. 17–18.

Candelario’s Original Curio Store still exists on San Francisco Street. Jake’s other brother, Abe Gold (1848–1903), ran a drygoods business with ladies’ and gents’ furnishing goods on San Francisco Street. His wife purchased the former site of Jake’s Free Museum in 1900, and the couple reopened Gold’s Old Curiosity Shop and Free Museum. When Abe died in 1903 his wife leased the store and later sold the inventory to another curio dealer, Thomas Dozier.

After World War I, Saarland was administered by the League of Nations, so Mettlach could not export into the German Reich. Between 1920 and 1935 the company was run from its headquarters in Dresden, but when the Saar area was reincorporated into the German Reich in 1935, Mettlach once again became the location for the Villeroy & Boch headquarters. Two years after a plebiscite held in 1955, Saarland became part of the Federal Republic of Germany. As a result of World War II the company lost its eastern facilities in Dresden, Torgau, and Breslau. See Desens, Villeroy und Boch, pp. 161–72.

The countries represented in the Keramikmuseum collection are: Belgium, China, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Egypt, England, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, India, Iran, Italy, Japan, Madagascar, Mexico, Morocco, Netherlands, Peru, Russia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the U.S.A. (New Mexico), and the South Sea Islands, as well as portions of Central America.