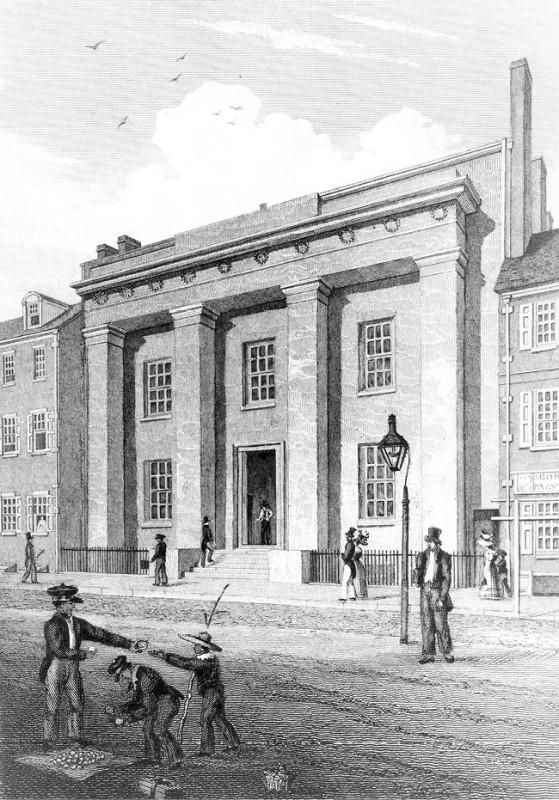

Vintage print depicting the original Franklin Institute building, possibly 1824. Reproduced from Bruce Sinclair, Philadelphia’s Philosopher Mechanics: A History of the Franklin Institute, 1824–1865 (Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1974).

Game pitcher, Abraham Miller, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1840s. Rockingham glazed earthenware. H. 9". Mark, impressed on underside: ABM MILLER. (Private collection; photo, Randl Bye.)

Detail of the pitcher illustrated in fig. 2, showing the mark on the underside.

Log cabin money bank, Thomas Haig Jr., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1850s. Earthenware with flint enamel glaze. H. 4 1/2". Mark, inscribed in script on underside: “Peter Feltey.” (Private collection; photo, Randl Bye.)

Detail of the bank illustrated in fig. 4, showing the inscription on the underside.

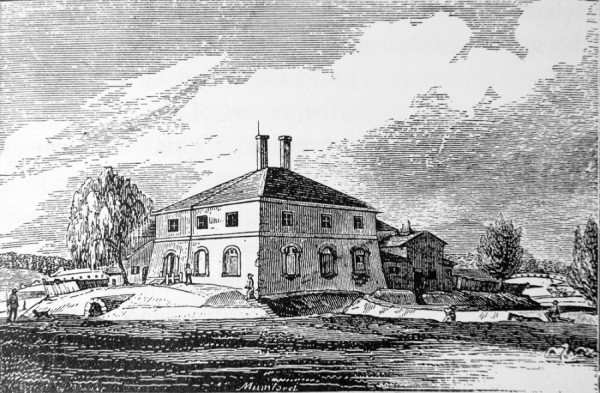

The Old Water-Works, Philadelphia, Used as a China Manufactory in 1825, vintage print depicting Tucker’s china manufactory in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1825. Reproduced from Edwin Atlee Barber, The Pottery and Porcelain of the United States: An Historical Review of American Ceramic Art from the Earliest Times to the Present Day (1893; reprint, New York: Feingold and Lewis, 1976), p. 129.

“Grecian pitcher,” Andrew Craig Walker for the William Tucker factory, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1828–1838. Gilt and enameled porcelain with floral design. H. 8". (Private collection; photo, Randl Bye.) The flaring gilt design is typical of Tucker porcelain.

Detail of the pitcher illustrated in fig. 7, showing the incised letters on the underside. According to Barber, an incised “W” either in script or straight lines was used by Andrew Craig Walker, a leading molder at the Tucker factory. Barber added, “It occurs on many of the best pieces.” Barber, Pottery and Porcelain (reprint), Marks of American Potters, p. 17.

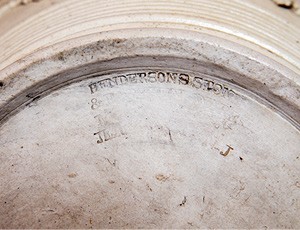

Hunt pitcher, D. & J. Henderson, Jersey City, New Jersey, ca. 1828. Flint stoneware. H. 10 1/2". Mark, impressed on underside: HENDERSON’S STONEWARE / & EARTHENWARE / MANUFACTURER, / JERSEY CITY, N.J. (Private collection; photo, Randl Bye.)

Detail of the pitcher illustrated in fig. 9, showing the impressed mark on the underside. This mark, perhaps the firm’s earliest, was rarely used.

Pitcher with acorn-and-oak-leaf decoration, D. & J. Henderson, Jersey City, New Jersey, ca. 1830. Salt-glazed flint stoneware. H. 8 1/2". Marks, impressed on underside: “D. & J. / Henderson / Jersey City” within two concentric circles; “O” (Private collection; photo, Randl Bye.) The “O” probably relates to the size of this model.

Detail of the pitcher illustrated in fig. 11, showing the impressed mark.

“Grecian pitcher in the Tucker style,” Smith, Fife & Co., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1830. Porcelain with gilt and enameled decoration. H. 7 1/2". (Philadelphia Museum of Art, gift of John Morris, 1893.)

“Vase Shaped Pitcher with Landscape Decoration,” Andrew Craig Walker for the William Tucker factory, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1831–1838. Enameled and gilt porcelain. H. 9". Mark, incised on underside: “W” (composed of two “V”s). (Private collection; photo, Randl Bye.)

Landscape on the reverse of the pitcher illustrated in fig. 14.

Detail of the pitcher illustrated in fig. 14, showing the two incised “V”s on the underside. According to Barber, this mark was also frequently used by Walker.

“Wall fountain,” American Pottery Company, Jersey City, New Jersey, ca. 1833–1838. Creamware. H. 11". Circular scalloped mark impressed, “AMERICAN POTTERY CO. / JERSEY CITY” (Private collection; photo, Randl Bye.)

“Heart shaped perfume bottle,” William Tucker factory, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1830–1835. Enameled and gilt porcelain. H. 1 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Randl Bye.)

“Spittoon,” American Pottery Company, Jersey City, New Jersey, ca. 1842. Glazed earthenware. H. 3", diam. 8". (Collection of the Franklin Institute.)

Tea set, Daniel Greatbatch for the American Pottery Company, Jersey City, New Jersey, ca. 1840. Creamware. Covered sugar dish H. 3 1/2"; teapot H. 3 1/2"; creamer H. 3". Circular marks, impressed: AMERICAN POTTERY, JERSEY CITY (Private collection; photo, Randl Bye.)

“Toby jug,” Daniel Greatbatch for the American Pottery Company, Jersey City, New Jersey, ca. 1840–1845. Rockingham glazed earthenware. H. 10 1/2". Circular mark, impressed:AMERICAN POTTERY, JERSEY CITY, NJ (Private collection; photo, Randl Bye.)

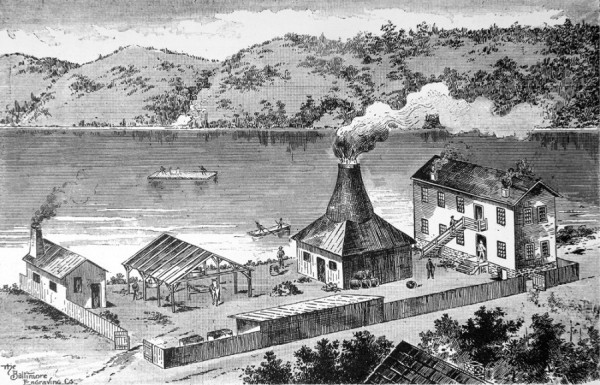

The Old Bennett Pottery, East Liverpool, O., The Baltimore Engraving Co., ca. 1900. Vintage print depicting the Bennett Pottery in East Liverpool, Ohio. Reproduced from Barber, Pottery and Porcelain of the United States, p. 193.

“Druid Spout Pitcher with Snake Handle,” E. & W. Bennett Pottery, Baltimore, Maryland, ca. 1848. Earthenware with Rockingham glaze. H. 9". Mark, impressed on underside: E & W BENNETT, / CANTON AVENUE, / BALTIMORE. (Lora Robbins Gallery of Design from Nature, University of Richmond Museums, gift of Emma and Jay Lewis; photo, Meg Eastman.)

Detail of the pitcher illustrated in fig. 23, showing the mark.

“Hunt Pitcher,” Harker Taylor, East Liverpool, Ohio, ca. 1846–1852. Earthenware with Rockingham glaze. H. 10". (Philadelphia Museum of Art, gift of Jay and Emma Lewis, 2008.)

“Doorplate with View of New York City,” Elijah Tatler for Charles Cartlidge & Company, Greenpoint Brooklyn, New York, 1848–1850. Enameled porcelain. H. 1 1/2", W. 3".

(Private collection.)

Ralph Bagnall Beech (active 1845–1857), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1851. Daguerreotype. 4 x 3 1/2 x 1". (Winterthur Museum, Museum purchase and a gift from Emma and Jay Lewis; photo, Jay Lewis.)

“Japanned Vase with Mother-of-Pearl inlay and full body portrait of Stephen Girard,” William Crombie for Ralph Bagnall Beech, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1851. Porcelain. H. 16". (Philadelphia Museum of Art, gift of John T. Morris, 1902.) Stephen Girard was a wealthy Philadelphia banker and philanthropist.

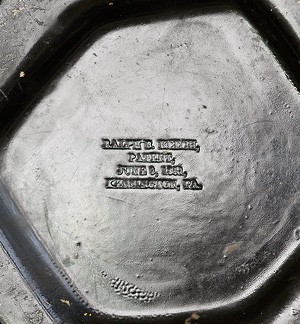

“Japanned Vase with Architectural Landscape and Mother-of-Pearl Inlay,” Ralph Bagnall Beech, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1851. Earthenware. H. 18 1/2". Mark, impressed on underside: RALPH B. BEECH, / PATENT, / JUNE 3, 1851, / KENSINGTON, PA. (Winterthur Museum, Museum purchase and a gift from Emma and Jay Lewis; photo, Jay Lewis.)

Detail of the vase illustrated in fig. 29, showing the impressed mark.

“Floral Cake Plate from a dessert service,” Karlbaum & Schwartz, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1852. Enameled and gilt porcelain. Diam. 9 1/2". Mark, impressed on underside: K + S. (Philadelphia Museum of Art, gift of Mrs. Robert John Hughes, 1939.)

“Grape Ice Pitcher,” Daniel Greatbatch for the Swan Hill Pottery, South Amboy, New Jersey, ca. 1852. Rockingham with flint enamel. H. 9 1/2". Mark, embossed swan mark that indistinctly reads: “Hanks and Fish, Swan Hill Pottery, S. Amboy, N.J.” (Private collection; photo, Randl Bye.)

“Pitcher Depicting Two Young Boys at Play,” American Porcelain Manufacturing Company, Gloucester, New Jersey, ca. 1854. Porcelain. H. 8". Mark, impressed: APMCo. (Courtesy, Brooklyn Museum, the Arthur W. Clement collection.)

“Five gallon crock,” Richard Clinton Remmey, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1860–1880. Stoneware with cobalt decoration. H. 15 1/2". Marks: incised on neck, “5”; impressed near base, R.C.R. / Phila. (Private collection; photo, Randl Bye.)

Detail of the crock illustrated in fig. 34, showing the impressed mark near the base.

Throughout the many decades since ceramics were exhibited at the Franklin Institute’s annual exhibitions of 1824–1858, those venues have been much cited by historians and connoisseurs as the highest plateau of recognition of achievement for ceramic production in the United States. But the exhibitions included a much wider variety of American-made products, including glass, machinery, furniture, various types of fabric, daguerreotypes, and flour, among other categories. During the nineteenth century, the institute was located at 15 South 7th Street, now the home of the Atwater Kent Museum. The distinctive original building, an austere version of Greek Revival style, was designed by the prominent Philadelphia architect John Haviland (fig. 1). The institute’s annual exhibitions were held at different locations in Philadelphia, the first, in 1824, at Carpenter’s Hall. The institute continues today, but with a primary focus on science and technology.

In 1980 Susan Myers published Handcraft to Industry: Philadelphia Ceramics in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century, in which she discussed the ceramics exhibited at the Franklin Institute and included, for the first time, a section devoted to the annual ceramics exhibitions. However, her study examines only examples produced in Philadelphia, ignoring those produced in other areas of the country, as was the norm of these exhibitions.[1]

This essay represents the first study to include and list the exhibitors of ceramics at the Franklin Institute from the entire country—which at that time, of course, was limited to states from the East Coast through the Midwest. There were no ceramics factories in the West in the mid-nineteenth century, and much of the ceramics industry was situated geographically around Philadelphia and New York City. The fact that many of the ceramic items exhibited had a Philadelphia origin might reflect some pro-Philadelphia bias and interest. Certainly there was much about the ceramics of Philadelphia for the judges to be proud of, but it must be admitted that the judges’ comments were also very fair in their evaluations of ceramics from Jersey City and other areas, providing awards to exhibitors outside “the city of brotherly love.”

In reviewing the annuals, we see that ceramics were exhibited in most years but not all. The exhibitions of 1847 and 1849 only included Rockingham wares by Harker Taylor of East Liverpool, Ohio; no ceramics from Philadelphia were included. The two principal sources are a series of manuscripts called “The Franklin Institute Committee on Exhibitions Judge’s Reports” and the Journal of the Franklin Institute, first published in 1826. Both are part of the Historical and Interpretive Collections of the Franklin Institute. Myers uses several abbreviations that can be confusing for readers, but I simply refer to these two major sources as “Judges” and “Journal.” The items in these exhibitions were “deposited” either by someone from the factory or, as listed in the two sources, by an individual who must have been a friend of the factory. Ceramics were part of the many items in several categories exhibited, but from 1835 “Ceramics and Glass” was a separate category. Prizes, or “Premiums,” were awarded by the judges for superior entries.

I have tried to match the illustrated ceramics items to what was (or may have been) exhibited in the year of the annual. In the case of the Miller and Haig potteries, there is a lack of early signed or reliable material from the 1820s and 1830s, so I have illustrated two later examples (figs. 2–5). Unlike annual paintings exhibitions at the nearby Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, it is not possible to determine which example was exhibited, as these were often multiple production pieces. The Franklin Institute today only retains one unsigned example that is known with certainty to have been exhibited.[2]

It is important to relate that aesthetics was nearly as important as technological advances to the Franklin Institute’s judges. Although the institute occasionally exhibited ceramic items as base as firebrick (and even the William Tucker factory made them), they presented awards or premiums only to refined tableware, and often commented on the beauty of items on display, especially those of the Tucker factory. The judges definitely saw beautiful objects as a major result of technology. The institute exhibited utilitarian stoneware only in the last three annuals—the Twenty-Fifth (1856), the Twenty-Sixth (1858), and the Twenty-Seventh (1874).

Another important consideration for the judges was expense; at times they questioned whether families could afford the objects exhibited.[3] They often referred to the low sales price of earthenware items yet did not comment on the retail prices for porcelain table ware, which sold at higher prices since manufacturing costs tended to be higher as well, at least until mid-century.

The earliest significant writer to discuss the ceramics displayed at the Franklin Institute’s annual exhibitions was Jennie J. Young in her 1878 book The Ceramic Art: A Compendium of the History and Manufacture of Pottery and Porcelain. Coming only a few years after the Philadelphia Centennial, the book provides a history of ceramic art, and the final chapter on ceramics of the United States begins by noting, “That there is a brilliant future in store for the ceramic art of America may be inferred from the rapidity with which it has been pushed forward to the stage it has already reached.”[4] Young wrote that American ceramics had progressed rapidly over a rela-tively short period of time, twice mentioning the Franklin Institute annuals. Reinforcing Young, Myers wrote that the previous goals of the institute had been accomplished, to a large extent, “for the promotion and encouragement of manufacturers and the mechanic and useful arts.”[5] In the nineteenth century, American ceramists were increasingly able to compete with their more sophisticated colleagues in Europe and Asia, although it was a difficult road for them to travel, full of financial barriers and other hardships. Finding skilled craftsmen and laborers had been a problem in the United States in the eighteenth century, made worse in the nineteenth century by significant technological advances on both sides of the Atlantic, as new types of ceramic bodies and glazes were introduced. The “rapidity” that Young referred to had been much in evidence at the annuals, but it was not until the end of the century that American ceramic manufacturers could successfully compete with Europeans in exhibitions both in the United States and in Europe. The Franklin Institute exhibitions document many of American ceramists’ early attempts at sophisticated manufacture.

Edwin Atlee Barber was the first true historian of American ceramics. In his illustrious career, he became curator of ceramics at the Pennsylvania (now Philadelphia) Museum of Art in 1893 and the director in 1904. His book The Pottery and Porcelain of the United States: An Historical Review of American Ceramic Art from the Earliest Times to the Present Day goes well beyond Young’s essay and remains in use by ceramics scholars to this day.[6]

Barber interviewed and recorded the histories of the ceramists who had exhibited at Franklin Institute annuals so that the information would not be lost to time. In 1904 he published Marks of the American Potters, which, like his previous book, is relied on to this day.[7] Barber collected significant examples of American ceramics for the museum, with a strong preference for those created in eastern Pennsylvania. He often cites the Franklin Institute and its exhibitions of American ceramics, with illustrated examples from his Pottery and Porcelain of the United States. Although current scholarship has found flaws in Barber’s assumptions, in general his opinions were highly perceptive.

Very different from Barber is the prolific author John Spargo. Born in Cornwall, England, Spargo settled in Vermont in 1909. He became known as an activist of the Progressive Movement as well as the author of several books with socialist themes, including a biography on Karl Marx that was published in 1910.[8] By the 1920s, however, Spargo had become disillusioned with socialism and began to focus on regional ceramics instead. He was the founder and curator/director of the Bennington Museum from 1828 to 1944, and in 1926 published The Potters and Potteries of Bennington, a groundbreaking study of this subject.[9] In the same year he published Early American Pottery and China, which covered much of the same material that had been covered by Barber but did not offer much original research beyond Barber’s, and several of his assumptions are not solid.[10] He wrote disparagingly, “While Barber was far from a careful writer, frequently jumping at conclusions, and was much given to making wide generalizations on a too scanty basis of verified fact, his more important works cannot be dispensed with.”[11] Indeed, the same could be said of Spargo, who admitted to being a “hobbyist.”[12] He often referred to ceramics that were exhibited at the Franklin Institute annuals in Early American Pottery and China; however, despite his great enthusiasm for Bennington pottery and porcelain—made by the leading manufacturers of American ceramics at mid-century—he failed to mention that they were never exhibited at the Franklin Institute. It is surprising that neither Spargo nor, apparently, anyone else ever noticed this.

By the 1940s Arthur W. Clement was citing both Barber and Spargo. Like Barber, he took a more professional approach to American ceramics. Trained as a lawyer, he graduated from New York Law School in 1902 and eventually became a partner at the law firm of Bingham, Jones and Houston. Much interested in art, he became a member of the governing committee of the Brooklyn Museum. He was an avid collector of early American ceramics, scouring not just the United States for examples but also Europe and even Central America. He donated much of his collection of early American ceramics to the Brooklyn Museum, and it served as the basis of their collection in this area. In 1947 Clement published Our Pioneer Potters, in which he added much to the connoisseurship of this area.[13] (Unfortunately, although more accurate than Spargo, some of his assumptions were not well founded.) In Our Pioneer Potters, he published letters by Benjamin, William, and Thomas Tucker, as well as other significant figures, and did much to encourage interest in ceramics. In his book he cited the Franklin Institute’s annual exhibitions several times, and, being a lawyer, made it clear to the reader that he carefully read and understood the judges’ comments and took them seriously.

In his 1969 publication Collectors’ Guide to Antique American Ceramics, Marvin Schwartz shortened and simplified much of the same material as Clement, since his book was meant primarily for collectors, not curators.[14] But Schwartz’s text provides updated facts about the subject and is more accurate. Schwartz was a curator at the Brooklyn Museum and was very aware of Clement’s outstanding collection there; in fact, in his book he illustrated many ceramics items that had been part of Clement’s collection.

In 1980 Susan H. Myers, working for the Department of Cultural History, National Museum of History and Technology, Smithsonian Institution, published Handcraft to Industry: Philadelphia Ceramics in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century, in which she presented the first in-depth study of the Franklin Institute’s annual exhibitions that included ceramics.[15] Her text is well researched and factually correct, relying on the judges’ comments and the annual journals of the Franklin Institute. As her goal was to cover ceramics production in Philadelphia in the first half of the nineteenth century, she ignored ceramics production in the rest of the country. It is my intention here to place ceramics production within a national context. It is important to understand the work of Philadelphia’s ceramic competitors as, by the 1840s and 1850s, Philadelphia’s key role was taken by other ceramics centers. Since the focus of this essay is only on the Franklin Institute’s annuals, I am primarily concerned with the second quarter of the nineteenth century through 1858.

I believe that the major issue with Myers’s well-researched book is that she did not properly differentiate between the two major trends in American ceramics production, which can be clearly seen from the late eighteenth century and throughout the nineteenth century.

Earlier trends in American ceramics were focused on hand-crafted utilitarian ceramics and seemed less concerned about competing with those coming from Europe and particularly England. Not having the skills necessary (presumably), these potters generally did not train in European or American factory systems. As can be witnessed in the stonewares produced by the Crolius and Remmey factories in New York City and by the Morgan (and later Warne and Letts) potteries in New Jersey, pottery-making was a family affair, passed on from generation to generation. The output was primarily for local audiences and not intended to be marketed nationally. It includes stoneware jugs and crocks, as well as redware plates and platters. Today, many would refer to this type of ceramics as “folk pottery,” which was free to evolve in its own way without being overly influenced by British or other competition. These potteries were not part of the Industrial Revolution. Indeed, one could argue that these potters had more in common with the studio potters of the twentieth century, who performed most of the work themselves.

Of greater importance here is the later trend, which began in the late eighteenth century and focused on refined tableware. This was also the focus of ceramics at the Franklin Institute, at least in the earlier, more significant exhibitions. In the factory system, many could be employed in ceramics production, including modelers/mold makers, decorators, and unskilled laborers. Prior factory experience was desirable, and there was a clear division of labor, each individual having specific duties. These ceramists played a large part in the Industrial Revolution, which originated in England and swept across America in the nineteenth century. Porcelain production, in particular, was limited to the factory, as it required more sophisticated technology. In the late eighteenth century, the first porcelain manufactories were the John Bartlam factory in Cain Hoy, South Carolina, and the Bonnin and Morris factory in Philadelphia. Although primitive by nineteenth-century standards, these factories, though small, nonetheless created sophisticated, refined tableware, in direct competition with much sought-after wares being imported from England.[16]

Of late, much attention has been given to the Bartlam enterprise.[17] In addition to porcelain, Bartlam was the first to produce a sort of cream-colored, relatively thinly potted earthenware referred to as “queensware.” It was intended to be a less expensive, easier-to-produce alternative to porcelain. Josiah Wedgwood, England’s illustrious ceramist, created a successful version of queensware, which put Bartlam’s tiny factory in rural South Carolina in direct competition with Wedgwood and other British factories. Bonnin and Morris focused on porcelain production, creating well-made and well-designed blue-and-white tableware in the manner of England’s Bow and Worcester factories.[18]

Queensware remained popular in the early years of the nineteenth century, and American-made porcelain was not readily available in the United States as there were no porcelain factories in America at the time.[19] Philadelphia would again play a key role in American ceramics production until the 1840s. Interestingly, Philadelphia’s queensware, which included pitchers, bowls, teapots, and coffeepots, among other items, was markedly yellower than queensware made at other locations. Serving vessels other than queensware were typically red, brown, or black lead-glazed red earthenware (which, after about 1810, were created with the use of lathes). The Columbian Pottery of Philadelphia may be considered the first significant American concern of the new century. Founded in 1807 by Archibald Binny and James Rowlandson, the pottery employed the Scottish-trained master potter Alexander Trotter. Its queensware, the first to be made in America and publicly displayed, was exhibited in 1808 at Charles Willson Peale’s famous museum in Philadelphia, which opened on July 18, 1786. Originally conceived as a natural history museum, it featured a wide spectrum of displays: animal specimens, both living and dead; Native American artifacts; and many painted portraits by Peale and his family. The collection’s most noteworthy object was the reconstructed skeleton of a mastodon.[20]

Despite the popularity of the Columbian Pottery, only two signed sherds of its production survive.[21] By 1810 the pottery was competing with John Mullowny’s Washington Pottery, also in Philadelphia and producing similar wares. Mullowny’s pottery was apparently the first pottery to employ press molding, which would become a significant element in factory pro- duction in the nineteenth century because successful molds could be used repeatedly over a period of time, were more cost efficient, and often guaranteed more satisfying results.[22] Unfortunately, no Washington Pottery items are known to survive, not even sherds. The Columbian Pottery closed in 1814, and the Washington Pottery ceased operation in the following year.

Marvin Schwartz has noted that “several famous names in ceramics of the Philadelphia area first came up in the beginning of the century, but no proof of what they were making is evident before the 1820s.”[23] In 1824 the Franklin Institute’s annual exhibitions began to provide documentation through the exhibited work of many American potteries. Unfortunately, the work of several of the other ceramics exhibitors has been lost to time, with no surviving signed examples, although exhibition records do much to document their existence.

As discussed by Susan Myers, the War of 1812 had a substantial positive effect on the ceramics industry in this country.[24] The War of 1812 should be seen in the larger context of the Napoleonic Wars, however. After the Revolution, the United States seems to have maintained an agreeable position with France, where Napoleon had come into power in 1799. President Thomas Jefferson engineered the Louisiana Purchase from France in 1803, more than doubling the size of the nation. In the same year, Britain declared war on France, creating major difficulties for American sea trade. Following the Revolution, Britain was more antagonistic after ceding her thirteen most significant colonies. She had begun the unfair practice of impressing American sailors as a way to maintain the manpower in her navy, although it must be admitted that many of the abducted sailors had left the British Navy when they found better opportunities working on American ships. Americans preferred to use their seafaring vessels to trade with the French, but the British were interfering with profits. President Thomas Jefferson wanted to remain neutral and, in 1807, put an embargo on all foreign trade. This was a disaster for American shipping but was a major incentive for the production of American-made products, including ceramics, as there was no longer competition from abroad, especially Britain. In 1809 Jefferson replaced the embargo with the Non-Intercourse Act, which encouraged trade with other nations but excluded Britain and France. As a result, the period from the start of the embargo to the conclusion of the War of 1812 had been one of prosperity for American manufacturers. This had encouraged Philadelphia pottery enterprises, among them the Columbian and Washington Potteries as well as that of the young potter Abraham Miller (soon to be discussed), who had financially survived this period and later exhibited at the Franklin Institute. In fact, he served as a judge and was elected to the institute’s board of managers.

By 1800 Philadelphia, with more than 60,000 citizens, was the largest city in America. It previously had led the nation in shipping, but its shipping indus-try never recovered from the War of 1812, so that position was taken instead by the City of New York. Philadelphia was becoming the country’s leading manufacturing center due to the expansion of the interconnecting canal system, but Philadelphia’s preeminence would come to a close in 1825, when New York State’s governor De Witt Clinton opened the Erie Canal, thereby connecting New York City to the Great Lakes and the Midwest. Philadelphia had been the leading financial center of the nation—it was in fact the home of both the First and Second Banks of the United States—but the effect of opening the canal was rapid and dramatic, helping New York to become the nation’s center for finance. Throughout the nineteenth century the value of New York City’s real estate continued to rise at an astonishing rate.

In terms of culture, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, founded in 1805, could be considered one of the nation’s first museums, although its major goal was to educate aspiring artists and give them a public place to display their art by supporting annual art exhibitions. The leading founder of the academy was Charles Willson Peale, a painter of notable American patriots and dignitaries who had opened his own museum in Philadelphia. Another major founder was Philadelphia’s William Rush, considered to be America’s first significant sculptor. In 1825 New York City’s National Academy of Design was opened to the public for similar purposes. Among its founders were three artists: Samuel F. B. Morse (of Morse code fame), and Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand, the two founders of the Hudson River School.

Both cities had institutes to demonstrate the advances in manufacturing, and their early exhibitions served to display leading trends in America’s decorative arts and, in particular, American-made ceramics, glass, furniture, and textiles. While the American Institute of the City of New York was chartered on May 2, 1829, five years later than the Franklin Institute, its exhibitions had similar purposes and many ceramics companies exhibited at both. In fact, despite the sense of competition, the jurors of the American Institute were so impressed by the quality of Philadelphia porcelains by William Tucker that they awarded him a silver medal in 1831.

The following section details the annual ceramics exhibitions of the Franklin Institute, beginning with the first in 1824. The exhibitors are listed and discussed, and relevant examples of their ceramics are illustrated where possible.

1. Abraham Miller, Philadelphia: articles of earthenware, porcelain, black lustered pottery, redware, earthenware furnaces.

2. James Harper Jr., probably of Philadelphia: fire bricks.

Abraham Miller served as one of three judges on the institute’s Committee on Earthenware and was a member of its board of managers. Because of his position, Miller was unable to be considered for a prize (or premium). He was, however, the best-known potter in Philadelphia in 1824, described in 1893 by Edwin Atlee Barber as

one of the most progressive potters of his day and a man of more than ordinary intelligence and ability; and [who] at one time represented his district in the State Senate, where he was the courageous advocate of numerous reform measures. He was one of the most prominent members of the Franklin Institute for many years and was frequently selected as one of the judges for the awarding of premiums at annual exhibitions.[25]

Miller came from a family of Philadelphia potters. He was the son of Andrew Miller, who had started as an apprentice in ceramics by 1765 and was operating his own shop by 1783. Toward the end of the century, Andrew had taken his son Andrew Jr. into his business at Trotter’s Alley, between Market and Chestnut Streets. It is unknown exactly when Abraham began to work in the business with his father and brother, but in 1809 both brothers formed a partnership, their father having withdrawn from managing the business. They soon moved their pottery to Zane Street, in Philadelphia. Andrew Jr. passed away in 1821, whereupon Abraham took control of the business.

Abraham Miller’s typical production included red, brown, and black lead-glazed red earthenware teapots, coffeepots, pitchers, and so forth, which were inexpensive to purchase and ubiquitous but not very compelling. They probably were similar to the black, brown, and red vessels made by the Columbian and Washington potteries earlier in the century, but the spectrum of objects Miller displayed was diverse and unusual for the time and included porcelain and luster examples, as well as his signature earthenware furnaces for which he had become quite noted. No one knows what Miller’s porcelain or luster wares actually looked like as none has been identified, but porcelain examples certainly would be very rare and considered historically important today. Barber wrote that “Mr. Miller was probably the first in this country to make the lustered or silvered ware which has become celebrated in England.”[26]

The Rockingham pitcher illustrated in figures 2 and 3 is the only known marked example by Abraham Miller that has come to light. The underside is clearly impressed “AMB MILLER.” Similar impressed marks can be found on four pieces from the Gateway Redevelopment Project in Philadelphia, which was conducted in 1991. Those items, currently in the collection of the State Museum of Pennsylvania, include a bowl, a baking dish, and two plates.[27] Although the game pitcher is obviously later than what Miller exhibited in 1824 at the Franklin Institute, he was one of the first potters in this country to try creating Rockingham glazes in the 1840s. He must truly have been an innovator, trying his hand at porcelain, luster ware, and Rockingham wares. The pitcher, which is thickly potted and sturdy, has a hound handle and embossed decoration of hanging deer and boars. Unfortunately, there is substantial wear around its center. A similar Rockingham game pitcher, ca. 1852–1855, has been attributed by Jane Perkins Claney to Taylor and Speeler of Trenton.[28]

1. Thomas Haig Jr., Philadelphia: one black teapot, one black coffeepot, one half-gallon pitcher with diamond-shaped decoration, similar pitcher, undecorated, one red teapot, one cake mold (size no. 6), similar cake mold (size no. 9), similar cake mold (size no. 11), fourteen strainers, three pans. awarded honorary mention.

2. Abraham Miller, Philadelphia: fifteen clay furnaces, or earthenware chafing vessels of different sizes.

Like the first exhibition, this exhibition focused on Philadelphia makers and included the work of one of Abraham Miller’s competitors, Thomas Haig Jr., who was awarded an Honorary Mention. Haig exhibited items similar to the ones Miller exhibited the previous year. Both Miller and Haig had remarkably similar family histories. Haig also had come from a family of potters. His father, the senior Thomas Haig, came from Scotland in 1812 to start a pottery in the Northern Liberties section of Philadelphia. After his death in 1833, his two sons, Thomas and James, took control of the business, and when James passed, Thomas continued the business.

Like Miller, Haig was producing ubiquitous red-and-black tableware. The judges noted that if “the maker sent the articles by the time specified, he might have been a competitor for the silver medal offered on this branch of manufacture” (Journal, 1825, pp. 21–22).

As with Miller’s Rockingham pitcher, the flint enamel bank illustrated in figures 4 and 5 is later than Haig’s submissions to the Franklin Institute in 1825. Haig’s most beloved items are a series of log cabin–shaped coin banks that were executed in both stoneware and earthenware in the 1850s. They relate to the political situation in 1852 between Franklin Pierce, a Democrat, and Winfield Scott, who was from the Whig Party. The log cabin was a symbol for the Whigs. A similar stoneware example, signed and dated 1852, is in the collection of the Brooklyn Museum; this earthenware example is probably a bit later.[29]

Although the bank illustrated here is unsigned, the incised script used in the name “Peter Feltey” resembles the rather distinctive script used by Haig in the Brooklyn Museum’s signed example. Peter Felty (spelled without the second “e”) is listed as a farmer in Philadelphia city directories from 1856 to 1859. This is most likely the same person; perhaps it was a gift to him from a friend at the Haig Pottery.

1. Thomas Haig Jr., Philadelphia: coffeepots, teapots, sugar bowls, cream jugs, cake molds, fire bricks, earthenware items. awarded the bronze medal.

2. Andrew George & Co., Philadelphia: luster teapots, two mugs, six pitchers, red teapots, red pitchers, red mugs, etc.

3. New Jersey Porcelain and Earthenware Company, Jersey City, New Jersey: a large collection of china. awarded the silver medal.

4. Tucker & Bird, Philadelphia: a few small specimens of white earthenware.

The Third Exhibition was the first to include the work of a ceramics company located outside of Philadelphia—the New Jersey Porcelain and Earthenware Company of Jersey City. The large number of porcelain objects they displayed must have excited visitors as well as the judges. Previously, the only porcelain items displayed had been one or two items by Abraham Miller in 1824, but this large showing by the Jersey City firm indicated that ceramics technology was improving and tastes were changing.

Prior to this exhibition taste clearly related to British rather than French ceramics, but with the Empire style, which swept New York City in the 1820s, French styles were being imitated, as could be seen in New York City furniture shops as well. On August 24, 1826, the New York Commercial Advertiser stated that “[a]bout twenty artists, of first rate skill and experience, were procured from England and France—principally the latter—who have now for several months been engaged, and have produced kilns of ware, equaling in all respects, the finest French China Ware.”[30]

The New Jersey Porcelain and Earthenware Company was founded in 1824 by George Dummer, William W. Shirley, and others, but, Shirley oversaw the ceramics production. Much impressed, the Franklin Institute’s judges wrote that “on the evidence now presented . . . America is able to supply herself with this important product, and to look forward to a day, not very far distant, when this country will no longer pay tributary to foreign manufacturers, for their supply of these articles” (Journal, 1826, p. 264). Unfortunately, the only survivor of this company’s production is a rather uncompelling four-inch white porcelain bowl with a gilt rim in the Trumbull-Prime Collection of Princeton University.[31]

Concerning Thomas Haig’s submissions, the judges stated, “indeed your judges have seen nothing equal to them—your committee are of opinion that those made by Haig are rather the best” (Judges, 1826). Andrew George submitted similar pottery to that of Haig but today is largely forgotten.

The Third Exhibition is also significant in that it marks the first time that William Tucker exhibited at the Franklin Institute. His financial backer at the time was Charles Bird, a local merchant, but the judges were not impressed. They felt that these items—some form of whiteware or queensware—showed no improvement over other works exhibited at the institute. Tucker was not yet up to the demands of producing porcelain.

1. William Tucker, Philadelphia: porcelain goods, including cups and saucers, pitchers, fruit baskets, etc. awarded silver medal.

2. Thomas Haig Jr., Philadelphia: black and brown earthenware.

Beginning with the Fourth Exhibition, the porcelains produced by William Tucker began to play a key role at the Franklin Institute’s annuals. Like Abraham Miller and Thomas Haig, Tucker’s father, Benjamin, had been involved in the ceramics industry before him, maintaining a china store in Philadelphia at 324 High Street. William worked with his father as a china painter on the imported porcelain bodies. The following year, Tucker started his own porcelain manufacturing business, eliminating the need for imported blanks. He leased the Old Water-Works Building in the city (fig. 6) and was backed by a local merchant, Charles Bird, mentioned in the Third Exhibition above. Tucker purchased kaolin, the most basic ingredient in porcelain manufacturing, from Israel Hoopes in Chester County, Pennsylvania—apparently the same source used by the New Jersey Porcelain Company. He also tried obtaining kaolin from other regional ceramics factories that had failed at porcelain production.[32] Tucker fired his first kiln in early 1827, the results of which were exhibited at the Fourth Exhibition on October 18, 1827.

The judges stated that they had “great pleasure in the progress which this valuable and important manufacture is making towards perfection—the body of the ware is strong and sufficiently vitrified—the glaze is generally very good, and the gilding is done in a neat and tradesman like manner” (Judges, 1827). The judges also noted that Haig’s black-and-brown earthenware was of high quality.

1. William Tucker, Philadelphia: 100 pieces of the finest American porcelain. awarded second silver medal.

In 1828 Thomas Hulme of Philadelphia became a new partner in William Tucker’s business. Some rare pieces of porcelain are marked “Tucker and Hulme, China Manufacturers, Philadelphia, 1828.” Although the judges noted substantial improvement over the previous year, the partnership soon dissolved.

Tucker porcelain was very much in the French Empire style, which had become as popular in Philadelphia as it was in New York City—for example, as exemplified by Philadelphia’s Quervelle furniture and the Greek Revival architecture of financier Nicholas Biddle’s home on the Delaware River, Andalusia. As is typical of this style, Tucker porcelain includes substantial gilding and pairs of flanking caryatid handles on urn-shaped vases, which playfully reference the ancient Greco-Roman world.

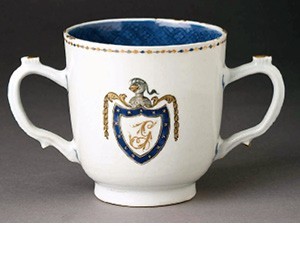

The shape of the Tucker pitcher illustrated in figures 7 and 8 was described as “Grecian” in the Tucker pattern book now in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The underside has an incised “W” and “N” in script. According to Barber, an impressed “W” (either in script or straight lines) was used by Andrew Craig Walker, a leading molder at the factory. Barber added, “It occurs on many of the best pieces.”[33]

No exhibition was held in 1829.

1. William Tucker, Philadelphia: 150 pieces of porcelain.

2. Smith & Fife, Philadelphia: two porcelain pitchers in the “Grecian” style.

3. D. & J. Henderson, Jersey City, New Jersey: flint stoneware items. awarded silver medal.

As the Sixth Exhibition made clear, there were two leading ceramics companies in the United States: D. & J. Henderson for earthenware and William Tucker for porcelain. The Jersey Porcelain and Earthenware Company, which was awarded a silver medal in the Third Exhibition, had been sold to the Scottish-born brothers David and James Henderson in 1828. David Henderson came to the United States in 1816 and managed a Jersey City print shop before becoming involved in ceramics production. D. & J. Henderson specialized in flint stoneware, which must have seemed unusual to the American public, since most of the American stoneware had been heavier, thicker, and without embossed decoration.[34] D. & J. Henderson’s stoneware, which was strengthened by the use of flint, was amazingly light and sturdy, and could be intricately detailed. Moreover, while its predecessor, Jersey Porcelain and Earthenware Company, was much influenced by French taste, D. & J. Henderson reflected more of the British Regency style emanating from English ceramics factories. On August 1, 1829, the Niles Register reported:

The manufacture of very superior ware, called “flint stoneware” is extensively carried on by Mr. Henderson at Jersey City, opposite New York. It is equal to the best English and Scottish stoneware, and will be supplied at 33 1/3 per cent less than like foreign articles will cost, if imported.[34]

Regarding this new flint stoneware, the Franklin Institute’s judges noted, “As it is comparatively cheap, and an article to be extensively used in families, the committee think this manufactory deserves special encouragement” (Journal, 1830, p. 3).

More than any American factory, D. & J. Henderson imitated the British factory system, where a single item would be the product of many workers, both skilled and unskilled. David Henderson hired British potter William Taylor and son James to introduce this system of manufacture to his company. In addition to the Taylors, Henderson brought many British potters to the United States to work at his factory in Jersey City, among them James Bennett, James Carr, Charles Coxon, Daniel Greatbatch, and Thomas Locker.

William Tucker produced “a good display of porcelain, consisting of upwards of one hundred and fifty pieces” (Judges, 1830). For the first time, Tucker had a competitor. Philadelphia’s Smith, Fife and Company exhibited a pair of “Grecian” pitchers with gilt and enameled decoration, very similar to Tucker Grecian pitches (see figs. 7, 8). The judges wrote that they “cannot omit a merited compliment to Messrs. Smith, Fife and Co.” (Judges, 1830). Tucker did not have long to worry about the competition, however, for Smith, Fife and Company was soon out of business.

The upper half of the large pitcher illustrated in figures 9 and 10 was submerged in brown slip, while the lower half displays the buff-colored unglazed clay. This might be the earliest known D. & J. Henderson vessel; it was handcrafted, as it was turned on a wheel. On each side are two embossed “sprig-decoration” scenes of two boys hunting with their dogs. Sprigs are tiny relief sculptures, made in plaster molds, which after drying are applied with slip to the sides of vessels. The Henderson factory soon abandoned handcrafting in favor of the use of molds.

A rare flint-stoneware pitcher with acorn-and-oak-leaf decoration (figs. 11, 12) is similar to a yellow ware version illustrated in Barber, but this example might be identical to, or actually one of, the flint stoneware items exhibited at the Franklin Institute in 1830.[36] It is amazingly thin and detailed. In fact, the delicately rendered leaves seem to overlap each other.

One of a pair, the unsigned pitcher illustrated in figure 13 is nearly identical to the signed pair of Grecian pitchers by this company in the Brooklyn Museum, except for minor differences in painted floral decoration. The Brooklyn pitchers, signed in red, were the same pitchers exhibited in this annual. The initials “TMcA” for the original owner, Thomas McAdam, appear on the front of the Brooklyn pitchers; the initials “PEJ” appear on this pitcher in the same area. Only five of such pitchers by this company, all from the same mold, are known today.

1. William Tucker, Philadelphia: “two invoices of china ware.”

2. Horner and Shirley, New Brunswick, New Jersey: 13 pieces of flint stoneware, 2 stoneware pitchers. awarded honorary mention.

3. D. & J. Henderson, Jersey City, New Jersey: flint stoneware.

With Judge Joseph Hemphill’s $7,000 investment into William Tucker’s business on May 31, 1831, the factory produced many of its finest wares in its following years of production. The judges proclaimed: “In like manner of the magnificent assortment of glassware, as well as the beautiful display of porcelain ware by Messrs. Tucker and Hemphill of Philadelphia . . . maintain the reputation which they have already acquired” (Journal, 1831, p. 327),

Newspaper critics agreed with the judges. The Daily National Journal wrote, “our attention was arrested by a large quantity of beautiful porcelain ware, manufactured in the city by Messrs. Tucker & Hemphill.”[37]

Although the firm of Horner and Shirley was short-lived and is largely forgotten today, it has an interesting story. The firm apparently did create a body of unsigned ware that could be attributed to it.[38] According to M. Lelyn Branin, the pottery, located on Water Street in New Brunswick, was producing flint stoneware, probably in imitation of that made by D. & J. Henderson.[39] Shirley in all likelihood was the same William Shirley of Jersey City who had overseen the ceramics production at the Jersey Porcelain and Earthenware Company, discussed above under the Third Exhibition.

J. Kerr and Co., a Philadelphia “china store,” advertised in the Philadelphia Inquirer an assortment of flint stoneware, “the same as the samples exhibited at the last exhibition of the Franklin Institute.”[40] The ad failed to mention the maker of the flint stoneware—Horner and Shirley or D. & J. Henderson—although M. Lelyn Branin has suggested that some ads in New Brunswick newspapers suggest that Kerr and Co. had some connection with Horner and Shirley, either as a distributor or as a financial backer.[41]

Tucker’s “vase shaped pitcher” (figs. 14, 15) is believed to be a solely American design of the Tucker factory. In fact, it was shape number 7 in the Tucker pattern book (Philadelphia Museum of Art), though the form was based on Neoclassical sources. The gilt flaring design on both sides of the pitcher is typical of Tucker porcelains. One side depicts a bridge over a waterfall, while the reverse depicts a rustic stone house with a porte cochere in a river landscape and with mountains in the distance. According to Barber, the mark on the underside of the pitcher (fig. 16) was frequently used by Walker as well.[42]

No exhibition was held in 1832.

1. Joseph Hemphill (Tucker factory), Philadelphia: various examples of American porcelain. awarded honorary mention

2. American Pottery Company, Jersey City, New Jersey: selection of queensware. awarded honorary mention.

William Tucker had died the year before this exhibition, at the age of thirty- two. That left Judge Hemphill in charge, but William Tucker’s brother, Thomas, had been working at the factory since 1828, and was doing much of the superior decoration himself by this time. In fact, he had become chief decorator and manager and, after William’s passing, was promoted to superintendent of the business. Even so, the judges wrote, “Honorary Mention is due to Joseph Hemphill of Philadelphia . . . in the moulding and glazing of which great improvement has been made” (Judges, 1833).

David Henderson reorganized his company in 1833 and changed its name to the American Pottery Company. Whereas D. & J. Henderson had created his signature flint stoneware, imitated by such firms as Horner and Shirley, he now focused on queensware. Although these wares were called “queensware” at the Eighth Exhibition, they in fact could have been described more accurately as “creamware.” Nevertheless, the items were very innovative for the time, as the judges noted:

Queensware from Jersey City consisting of cream colored ware and being the first we have known brought to the present state of perfection, as it is comparatively cheap, and an article to be extensively used in families, the committee thinks this manufactury deserves special encouragement [Judges, 1833].

This rare wall fountain (fig. 17) is one of the most classicizing examples made by this company. Its embossed decoration depicts flaming torches, scallop shells, and acanthus leaves. Unlike typical queensware, it is a bit more thickly potted. It bears the circular scalloped American Pottery Company mark, and could well have been intended as an exhibition piece.

No exhibition was held in 1834.

1. Joseph Hemphill, Philadelphia (Tucker factory): assortment of “beautiful ware from his factory.”

2. Abraham Miller, Philadelphia: black-and-red earthenware in various stages of its manufacture, from the crude material to its finished ware.

Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen noted that scent bottles like the heart-shaped perfume bottle in figure 18 were among the smallest items made by the Tucker factory. These charming, jewelry-like items could have been suspended from ribbons and used as necklaces.[43] Although tiny, the floral and gilt decoration is similar to decoration that the factory executed on larger pieces (see fig. 7).

The year 1835 marked the return of Abraham Miller as an exhibitor, after a ten-year absence. Still creating his ubiquitous red-and-black earthenware, the “how to” display by Miller might have been of interest to the exhibition’s visitors. This is also the first year that ceramics and glass were combined into one category.

No exhibitions were held in 1836 and 1837.

1. Joseph Hemphill, Philadelphia (Tucker factory): samples of china.

Thomas Tucker directed operations at the Tucker factory until 1837, when Judge Hemphill sold the business, ending a chapter in Philadelphia’s early creative activity and innovation.[44] By the time of this exhibition, Tucker had been out of business for several months, which may have led to the Tenth Exhibition being an unhappy one, perhaps seeming more like a memorial to the porcelain factory. In reviewing the items, the judges did not mention Judge Hemphill specifically but wrote, “The samples of China were very neat, but similar to that previously exhibited. The Committee regret to say the manufacture of this article is discontinued” (Journal, 1838, p. 18).

Susan Myers has attributed some of the economic problems of this time to the financial crisis of 1837–1838.[45] Philadelphia’s Miller and Haig potteries survived the crisis, but Tucker porcelains were truly luxury goods, and more costly for the manufacturers and the public alike. The judges’ comments seem to indicate that they were disappointed that Judge Hemphill decided not to support his factory further, since Tucker had become the nation’s leading producer of high-quality porcelains.

No Exhibition was held in 1839.

No ceramics were exhibited.

No Exhibition was held in 1841.

1. American Pottery Company, Jersey City: embossed ware jugs, teaware, spittoons (including those with white raised figures), and druggist jars. awarded silver medal.

2. C. M. Greiner, Philadelphia: specimens of painting on porcelain. awarded certificate of honorable mention.

3. Abraham Miller, Philadelphia: finer kinds of earthenware, plates, vases, and ornamental flowerpots.

Perhaps the most significant ceramic event of the Twelfth Exhibition was the return of the American Pottery Company, exhibiting new works in new styles and techniques after an absence of nearly a decade. By about 1840 the classical Empire and Greek Revival styles had given way to the Gothic Revival style, which is clearly indicated in the extraordinary ca. 1842 spittoon illustrated in figure 19. It was mentioned by Barber in 1893: “A glazed white-ware spittoon, evidently one of this series, is still preserved in the cabinet of the Institute, which is decorated with raised, conventional designs in white, on a dark-blue ground, the upper surface being fluted and in solid blue.”[46] It remains the only exhibited ceramic object still retained by the Franklin Institute.

The most significant Gothic Revival structure, situated across the Hudson River from the American Pottery Company’s factory in Jersey City, was architect Richard Upjohn’s Trinity Church in lower Manhattan, constructed from 1839 to 1846. The church’s spire made it the tallest building in New York City until 1869. The spittoon, with its white tracery, is architectonic and very much in the Gothic style. The creators of the spittoon may have been able to see the church’s spire from the factory in Jersey City at that time. Like the award-winning items that included the spittoon, the church was a triumph of American technology; its stained glass windows were among the first in the United States.

The exhibition’s inclusion of C. M. Greiner of Philadelphia’s painting on porcelains prompts the acknowledgment and display of a new type ceramic at the institute’s annuals. In describing these works, the judges wrote, “It is to be regretted that the artist has expended so much labor and time in decorating an inferior porcelain article of foreign manufacture” (Journal, 1842, p. 344). It seems odd that the institute would be interested in promoting such works, even awarding them an “Honorable Mention.” China painting involves more purely artistic talents, and does not generally reveal the technological improvements being made in the bodies of American ceramics, like those exhibited by the American Pottery Company. Greiner’s display was the first of a trend in an interest in china painting that would continue in subsequent annuals. Is this the first instance that the judges were beginning to lose their vision? No decorated examples by C. M. Greiner have been identified.

The white ceramic exterior layer of the spittoon illustrated in figure 19 was sprig-molded and laid over the blue slip before it was fired. The use of embossed white over navy blue seems to anticipate by about ten years the blue-and-white parian porcelains of the United States Pottery Company of Bennington, Vermont, although those employed a technique that did not require an applied outer layer.

Starting in about 1838, Daniel Greatbatch, the designer of the tea set illustrated in figure 20, became the leading mold maker at the American Pottery Company.

1. Abraham Miller, Philadelphia: common earthenware.

2. Bagaly & Ford, probably Philadelphia: two porcelain baskets.

3. American Pottery Company, Jersey City: cake jar with “water lute to prevent ants.”

By the 1840s the judges were more critical and harsher in their comments. In reviewing the category “China and Glass,” for example, they wrote: “the display in this department was not equal to that of the last exhibition, nor did it do justice, much less credit, to the state of manufacture in this country” (Journal, 1843, p. 16). However, it appears they were more disappointed with the glass than with the ceramics, as they did offer some praise for both Abraham Miller and the American Pottery Company.

The works of any early American porcelain company would be of interest today, but unfortunately not much is known about Bagaly & Ford and no porcelains by them have been identified.

Even though the American Pottery Company was one of the first ceramics companies in the United States to develop Rockingham glazes, from the comments of the judges and those expressed in the Journal it is difficult to ascertain whether Rockingham wares by the American Pottery Company were exhibited at the institute (fig. 21). These sources usually indicate what the item was, but nothing about its glaze. I believe it is safe to assume that, since Rockingham wares were a significant part of its production in the 1840s, examples were exhibited even if they were not described as such.

1. M. Strasser, Philadelphia: two painted porcelain cups. awarded certificate of honorable mention.

M. Strasser is largely unknown today. Like C. M. Greiner, who was an exhibitor in the Twelfth Exhibition (1842), Strasser was a china painter working on foreign blanks. When people think of china painters, they usually think of the china-painting movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when that art came into vogue, but the annuals at the Franklin Institute indicate that people were professional china painters much earlier. Since we have only initials rather than full names, it is possible to speculate that some of the china decorators at the annuals were women.[47]

1. Abraham Miller, Philadelphia: earthenware.

2. Bennett & Brothers, Pittsburgh: A variety of wares, including Rockingham jugs, mugs and spittoons. awarded second premium.

The Fifteenth Exhibition was the final year that Abraham Miller exhibited his pottery at the Franklin Institute. He had been a major figure there and the important role that ceramics had played at the annuals might, in some sense, have reflected his interests and taste.

The Fifteenth Exhibition also showed for the first time a large selection of Rockingham wares, named after the Marquis of Rockingham, who in the eighteenth century created the dark brown–glazed wares at his estate in Yorkshire, England. More particular to American Rockingham, soon to be the most popular type of ceramic ware in the country, the brown glazes could be sponged, dabbled, and dripped; some of the best efforts resembled tortoiseshell.

The Fifteenth Exhibition helped to introduce James Bennett, who would become a leading figure in American ceramics. Born in England in 1834, he came to America and worked for David Henderson in Jersey City, where he remained until 1837. Thereafter, he seemed to shift about the country for several years, working in and even helping to establish a number of ceramics centers. In fact, in 1839 he built a pottery in East Liverpool, Ohio, which would become a major center for ceramics in America (fig. 22). In 1841 he sent to England for his three brothers—Daniel, Edwin, and William—who were also potters, and the company name became Bennett & Brothers. In 1844 they moved their plant to a section of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, known as Birmingham. Concerning the Rockingham wares exhibited at the institute in 1845, the judges wrote: “A good variety of ware and all very creditable. The jugs, mugs and spittoons are decidedly better than the English Rockingham ware, which is used extensively in this country, and furnished at prices which must successfully compete with the foreign article” (Journal, 1845, p. 20).

1. Ralph B. Beech, Philadelphia: a small group of earthenware items. awarded third premium.

2. Morgan & Richards, Kensington, Philadelphia: tobacco pipes. awarded third premium.

3. Bennett & Brothers, Birmingham, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Rockingham wares, yellow wares. awarded third premium.

James Bennett’s second showing was even more successful than the one in 1845. The judges wrote: “The makers [Bennett & Brothers] received a second premium at our last exhibition; but the present samples show a great improvement over the excellent ware exhibited by them last year” (Journal, 1846, p. 19). Apparently, Bennett was the first exhibitor to receive a first prize or premium for ceramics works. Even Tucker had never received a first prize. A similar Druid Spout Pitcher by Bennett & Brothers was exhibited in 1846 (figs. 23, 24).

1. Harker Taylor, East Liverpool, Ohio: Rockingham ware. awarded second premium.

For the first time, no Philadelphia companies were included in the Seventeenth Exhibition. Harker Taylor, like Bennett & Brothers, had been an East Liverpool factory that specialized in Rockingham wares. Benjamin Harker Sr. had started a pottery there in 1840, coming into competition with James Bennett and his brothers. Rockingham wares were produced there until 1879 (fig. 25). James Taylor and his father, William Taylor, had brought the British factory system to David Henderson in Jersey City before James joined Harker as a partner by 1847.

No ceramics were exhibited.

1. Harker Taylor & Co., East Liverpool, Ohio: Rockingham wares. awarded second premium.

As in the Seventeenth Exhibition of 1847, only Harker Taylor exhibited ceramics and, again, there were no exhibitors from Philadelphia.

1. Charles Cartlidge & Company, Greenpoint, New York: porcelain doorknobs, doorplates, and escutcheons. awarded first premium.

2. Harker Taylor, East Liverpool, Ohio: “a fine quality of stoneware,” Rockingham of “high lustre.” awarded third premium.

3. Alfred A. Cooper, Philadelphia: red earthenware.

4. Gerardin, New York, New York: knobs and other porcelain goods that were imported (only the mountings were American made).

Born in 1800, Charles Cartlidge was a potter from the noted ceramics center of Staffordshire, England, who arrived in the United States in 1832. He was an agent for the British ceramics firm of William Ridgeway before he decided to enter the ceramics business himself. He opened a plant in 1848, in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, close to the East River and Manhattan. He initially produced only plain white buttons, but then expanded into doorknobs, doorplates, and a selection of gilt porcelain pitchers. By mid-century the cost of porcelain production had decreased and Cartlidge could create what would be considered luxury goods for middle-class consumers. In comparison to previous porcelains by Tucker, Cartlidge porcelains can be recognized by their milky white, glassy quality; the company did not sign its work.

The Harker Taylor Company from East Liverpool exhibited for the third time in the twentieth exhibition. Although the judges had much appreciated the company’s Rockingham, perhaps they had grown somewhat tired of it, for while they acknowledged that Harker Taylor “presents a very fine quality of stoneware with its rich brown glazing of high lustre,” they added, “There being nothing new in form or quality of ware, the committee cannot recommend an award unless it can be a certificate for encouragement” (Judges, 1850). Perhaps regretting their initial harshness, the judges awarded the Harker Taylor Company a third premium, although this was the last year that the company exhibited at the annuals.

The judges were very disappointed with the redware of Alfred A. Cooper of Philadelphia, writing that it “is the commonest kind of red earthenware of very inferior quality in the body, in the soft lead glaze and of tasteless forms” (Judges, 1850).

By the 1850s the judges appeared to be losing direction, since a major criterion of the institute’s annuals had been a serious interest in American- made items from American-made materials. It seems at odds with their mission that they would have accepted the porcelain items by Gerardin of New York City. Those porcelains were imported, as was noted by the judges, but the mountings were of American manufacture (Journal, 1850, p. 13).

Elijah Tatler was Cartlidge’s leading decorator and had worked previously at the Copeland factory in England. The scene depicted on the doorplate is a view across the East River from the Cartlidge factory in Greenpoint (fig. 26). The tallest building in the city at that time was the newly constructed Trinity Church, designed by Richard Upjohn and located at the intersection of Broad and Wall Streets. The church’s steeple can be seen in this painted image on porcelain. On the back of the doorplate is written, in pencil, “New York Harbor painted by Tatler.”

1. Ralph Bagnall Beech, Philadelphia: porcelain flower and scent bottles, some Japanned works on earthenware. awarded third premium.

2. Charles Cartlidge & Company, Greenpoint, New York: porcelain knobs and door furniture.

The japanned works of Ralph Bagnall Beech (fig. 27; active 1845–1857) were in imitation of eighteenth-century Chinese export lacquer. Painted black enamel with gilding and inlaid mother-of-pearl, they were distinctive and innovative. He used American materials for the body, a biscuit earthenware, so the judges could not claim that he was using foreign blanks. Beech probably deserved more than a Third Premium, especially considering that he was a Philadelphia ceramist. Born in Britain, Beech learned his trade at Josiah Wedgwood’s factory. He arrived in the United States in 1842 and first worked for Abraham Miller in Philadelphia, then opened his own pottery in the city’s Kensington area. On June 3, 1851, he took out patent number 8140 for the japanning process.

A japanned vase in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum depicts French-born Stephen Girard, whose portrait appears on the vase (fig. 28). Girard was a naturalized citizen, an American banker and philanthropist who helped save the U.S. government from financial ruin during the War of 1812. He went on to become one of the wealthiest men in America.

Another imaginative and unusual vase (figs. 29, 30) features a stepped tower of inlaid mother-of-pearl. It calls to mind similar stepped towers by the visionary American painter Erastus Salisbury Field, whose architectural canvases date from 1867–1888. This vase bears the impressed stamp “ralph b. beech, patent, june 3, 1851, kensington, pa.”

Regarding the Charles Cartlidge submissions, the judges commented that his porcelains were “equal to that for which a First Premium was awarded to the same makers at the last Exhibition [referring to the Cartlidge factory]” (Journal, 1851, p. 16).

In the 1851 Journal the judges wrote, “An apprehension was entertained by some of the friends of the Institute, that the imposing effect of the Great Industrial Exposition in London would, to a great extent, diminish the influence and interest in our annually recurring, and less pretending Exhibitions” (Journal, 1851, p. 1).

Designed by architect Joseph Paxton, London’s Crystal Palace was a spectacular building created from cast iron and plate glass. Opening in 1851 to much acclaim, it would house the Great Exhibition, where examples displaying advances in technology were on view, clearly a result of the Industrial Revolution. While the Franklin Institute’s judges were concerned, in the same opening essay in the Journal of 1851 they claimed that “[t]his anticipation has not, however been fulfilled; on the contrary, additional zest appears to have been given to our efforts” (Journal, 1851, p. 1). Unfortunately, that zest was probably relatively short-lived.

The problem of competition in the area of technology was brought home by New York City’s response to the London Crystal Palace. Directly inspired by the British Palace, the American Crystal Palace—designed by George Carstensen and Charles Gildemeister and located in Bryant Park, near the intersection of 42nd Street and Fifth Avenue—opened with a public address by President Franklin Pierce on July 4, 1853. The theme, similar to that of the London Palace, was “Industry of All Nations.” This was the first American World’s Fair (several others would follow), where American-made products were compared with those on display from other countries, so visitors could assess American progress for themselves.

The most significant display of American ceramics at New York’s Crystal Palace was definitely that of the two related Bennington, Vermont, potteries: Lyman, Fenton & Co., which specialized in flint enamel; and the United States Pottery Company, which specialized in parian porcelain. Flint enamel reflected an American evolution in Rockingham glazes by the late 1840s and 1850s through the use of metallic oxides that added color—often blue and green splashes—to the tortoiseshell effects of Rockingham glazes. Named after Parian marble and fired at a lower temperature, the interiors of parian pitchers were glazed to hold liquids. Bennington parian was usually white, but also often included a contrasting blue background on a stippled surface. The two companies became the leading American potteries of the 1850s, displaying their quality of work and innovations in both flint enamel earthenware and parian porcelain. Yet for some unknown reason, such significant works were never exhibited at the Franklin Institute, although both companies clearly displayed technical advances in American ceramics.

Japanned ceramics may have been the most distinctive and innovative work produced in Philadelphia during the 1850s. In the Twenty-Third Exhibition of 1853, John Thornley of Philadelphia displayed japanned earthenware in the manner of Beech’s preexisting patent. On October 21, 1953, a New York reviewer wrote of Thornley’s japanned ware: “These articles appeared to be overdone with paint. Some were decorated in the style of papier-mache, and among the ornamental productions was a splendid view of New York City’s Crystal Palace, done in bright pearl ornaments, and giving some idea of the brilliant appearance of the building when lighted up with gas.” So viewers surely were reminded of the popularity of New York’s Crystal Palace when they visited the Franklin Institute’s annual of 1853.[48]

Ironically, the institute’s last significant exhibition of ceramics was held at the annual in 1858. That same year, New York’s Crystal Palace was destroyed by a fire while the city was hosting the fair of the American Institute, the Franklin Institute’s most serious competitor.

1. Charles Boulter, Philadelphia: firebricks.

2. Kurlbaum & Schwartz, Philadelphia: porcelains. awarded first premium.

3. James Carr and Thomas Locker of the Swan Hill Pottery, South Amboy, New Jersey: Rockingham ware, yellow ware

4. C. Friese, Philadelphia: china painting. awarded third premium.

5. John Thornley, Philadelphia: porcelains, and japanned earthenware vases and articles after Beech’s patent. awarded first premium.

The Twenty-Third Exhibition offered an interesting variety of American- made wares, including Philadelphia-made porcelain vessels by Kurlbaum & Schwartz, Rockingham wares by the Swan Hill Pottery (some of which most likely included flint enamel examples), and japanned vases by John Thornley.

Charles Boulter was a figure of note in the history of Philadelphia ceramics, although this was the only annual in which he exhibited. According to Barber, Boulter had worked at the Tucker and Hemphill factory until it closed, and then worked for Abraham Miller, first as a foreman and later as superintendent.[49] Boulter is listed as an independent potter in the 1850 Philadelphia census.[50] No examples of his work have been definitively identified.

The judges rather brazenly wrote of Kurlbaum & Schwartz that theirs was “the best American porcelain we have ever seen” (Journal, 1853, p. 22), which leads one to wonder whether the judges had ever seen Tucker porcelain. Even though Kurlbaum & Schwartz did a creditable job in their Limoges-style teaware that was gilt and enameled (fig. 31), and even acknowledging that they were the leading Philadelphia porcelain company at mid-century, the firm never produced the variety and scale, nor achieved the artistic merits, of the previous Tucker company. The judges seemed to have a limited knowledge or appreciation of the ceramics they were considering. Unfortunately, the Tucker factory was never awarded first prize by the Franklin Institute. However, Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen has rightly indicated that Kurlbaum & Schwartz’s “gilding is especially notable for being thinner in application and more metallic in appearance than that found on the porcelain of earlier decades.”[51]

The judges’ shortcomings at this time can be seen in how they reacted to the Swan Hill Pottery entries. As stated above, it is likely that some of Swan Hill’s Rockingham wares were flint enamel, which was a major development in American ceramics at mid-century. Since the institute did not include flint enamel wares by Bennington’s Lyman, Fenton & Company, these Rockingham wares may have been some of the few examples of flint enamel exhibited at the annuals. The potter who managed the Swan Hill Pottery from 1852 to 1855 was James Carr, who is considered a major figure in the history of American ceramics. After arriving from England in 1844, Carr was first employed by the American Pottery Company in Jersey City, but in 1852 he rented the Swan Hill Pottery from its owner, Charles Fish, who was not a potter. Carr later described Swan Hill as a small pottery having one small kiln.[52] He was soon joined there by Thomas Locker, another originally British potter. At first they had a frustrating time finding the necessary flint for their glazes, but Carr was able to acquire some from a factory in Greenpoint, most likely that of Charles Cartlidge. The judges briefly described the Rockingham of Carr and Locker as a “fair exhibition, and worthy of notice, [and] we hope for further improvement” (Journal, 1853, p. 22), but the pottery was not awarded any premiums. This was probably the first time a significant American ceramics company was deliberately ignored by the Franklin Institute’s judges, and Swan Hill would never exhibit there again.

Although it can be argued that china painting did not truly fit the mandate for the institute’s interest in American-made wares, since the bodies were usually foreign, in 1853 the institute’s annual showed the work of C. Friese, who was awarded a Third Premium. Like C. M. Greiner, who exhibited in the 1842 annual, or M. Strasser, who showed in the 1844 annual, Friese is listed with the initial “C” rather than a full first name, which could mean that all three exhibitors were women. No works by any of these exhibitors have been identified.

It seems odd that the judges awarded the First Premium to the japanned ceramics of John Thornley, who used Ralph Bagnall Beech’s patent for japanning, since Beech himself had exhibited similar work the previous year and was only awarded a Third Premium. The judges elaborated: “the japanning is well done, and the decorating generally of superior order . . . and considerable improvement in decorations” (Journal, 1853, p. 22). To date, none of Thornley’s works has been identified.

A pitcher by the Swan Hill Pottery (fig. 32) is very much in the Rococo Revival style, with its thickly embossed naturalistic grape and grape-leaf decoration, as well as its branch handle. By the 1850s, Rococo Revival began to replace the Gothic Revival of the previous decade. This style was evident at New York’s Crystal Palace in 1853, and probably would also have been seen on view at the Franklin Institute annual. The Rococo Revival style is also typical of the contemporaneous reticulated and laminated furniture by the New York City firm of John Henry Belter.

The embossed decoration of bunches of grapes indicates that such pitchers were used for serving wine. These vessels were referred to as “grape ice pitchers” and included the use of intricate strainers on the spout to keep ice from spilling out with the wine. They came with or without covers (this one did not). Daniel Greatbatch, who like Carr had worked for the American Pottery Company in Jersey City, is believed to have designed this vessel for Carr at South Amboy.[53] There are random blue splashes in the pitcher’s Rockingham glaze, indicating that this is an example of flint enamel. The pitcher is marked with the prominent embossed swan mark of the Swan Hill Pottery.

1. Kurlbaum & Schwartz, Philadelphia: porcelain wares. awarded first premium.

2. C. Friese, Philadelphia: china painting. awarded third premium.

3. William. M. McClure, Philadelphia: painting on porcelain door furniture, both foreign and domestic.

4. William Young & Co., Trenton, New Jersey: porcelain doorknobs, plates, pitchers, etc. awarded first premium.

5. The American Porcelain Manufacturing Company, Gloucester, New Jersey: porcelain wares, including some for druggists. awarded first premium.