Platter illustrated with Cape Coast Castle on the Gold Coast Africa by Enoch Wood & Sons, Burslem, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1830. American transfer-printed earthenware, impressed on back: Wood. L. 16 1/2". (Paul Scott Collection; photo, John Polak.)

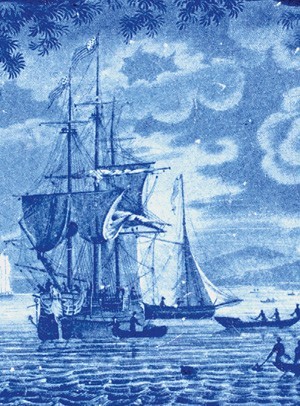

Detail of the platter illustrated in fig. 1.

George Webster (active 1797–1832), Cape Coast Castle, on the Coast of Guinea, 1799–1800. Watercolor on paper. 13 5/8 x 22 1/4". (Courtesy, Royal Museums Greenwich.)

John Hill (1770–1850) after George Webster, Cape Coast Castle, a British Settlement on the Gold Coast Africa, 1806. Colored aquatint on paper. 17 5/16 x 23 3/4". (Courtesy, British Library.) The inscription reads, “Drawn by G. Webster. / Engraved by J. Hill. / Published, Octr. 26. 1806, by J. Barrow, No. 1, Weston Place st. Pancras, & G. Webster, No. 21, White Lion Street, Pentonville.”

Detail of the platter illustrated in fig. 1.

Platter illustrated with Christianburg Danish Settlement on the Gold Coast Africa, Enoch Wood & Sons, Burslem, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1820–40. American transfer-printed earthenware. W. 18 1/2". (Courtesy, Historic Deerfield.)

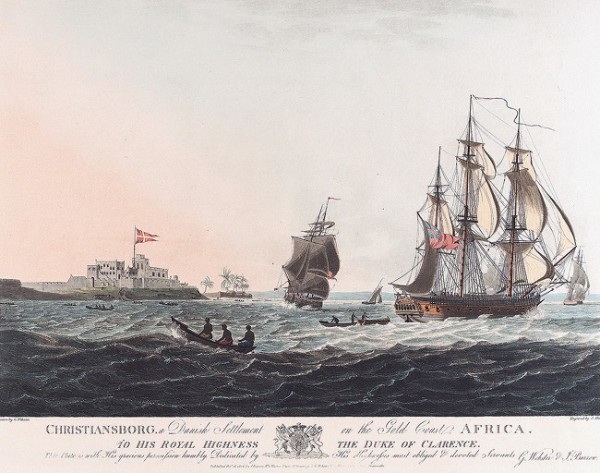

John Hill, Christiansborg a Danish Settlement on the Gold Coast of Africa. Colored aquatint after George Webster, published by J. Barrow, London, 1806. 17 5/16 x 23 3/4". (Courtesy, British Library.) Below the title is written, “Drawn by G. Webster. / Engraved by J. Hill. / Published, Octr. 26. 1806, by J. Barrow, No. 1, Weston Place st. Pancras, & G. Webster, No. 21, White Lion Street, Pentonville.”

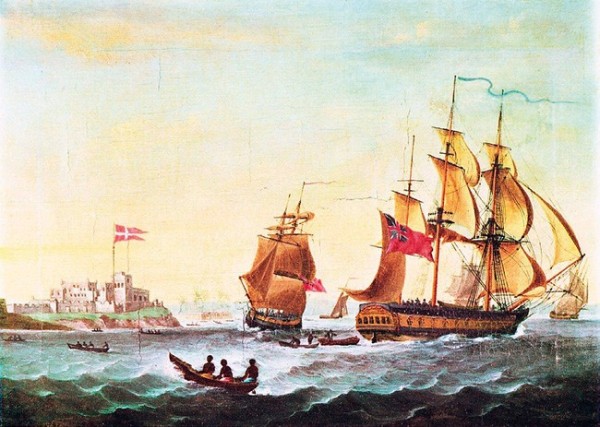

George Webster (1797–1864), Two British Slave Ships at Christiansborg, 1799–1800. Oil on canvas. 13 1/16 x 18 1/4". (Courtesy, Danish Maritime Museum.)

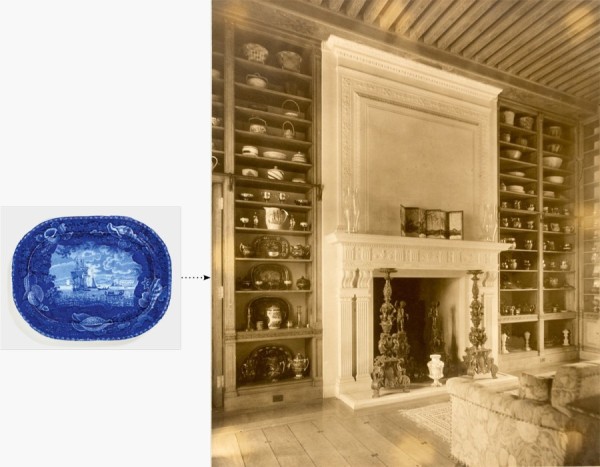

Photograph by Paul J. Weber in a ca. 1930 album, showing the Enoch Wood & Sons Cape Coast Castle platter on a shelf in the Aldrich family mansion in Warwick, Rhode Island. (Courtesy, Historic New England; photo, Paul J. Weber.) Paul Scott superimposed his own platter onto the image, confirming that the object displayed was indeed the Wood piece. See the Historic New England web site https://www.historicnewengland.org/explore/collections-access/capobject/?refd-PC009.228H.

He holds it up. “What do you think of this?” he asks. The color gets me first, a vibrant saturated blue that stirs the blood; then the wide frame of shells and foliage; and then I am looking into another world. My gaze arrives at the sinuous lettering of the title, Cape Coast Castle on the Gold Coast Africa. I take a breath. That’s when I understand what world I am looking into: Cape Coast Castle was the principal British center for the transatlantic Slave Trade for nearly 150 years.[1]

A picturesque seascape with a sailing ship flying American flags; across the water, clouds billowing above the white castle building; the Union Jack on a flagpole beside it; and there—in the foreground—a small vessel ferrying six seated figures toward the sailing ship (fig. 1). Who are they? Is this a scene from the slave trade?

The Cape Coast Castle platter was made by the firm of Enoch Wood & Sons.[2] It is a striking example of a genre of transfer-printed ceramics that were produced in Staffordshire, England, exclusively for the American market. Known as American transfer-printed earthenwares, or simply American transferwares, they were exported in large quantities between 1820 and 1840. They are illustrated with patriotic, celebratory images relating to the emergent republic, such as leading personages in the struggle for independence, and brand new municipal buildings. For all its beauty (and it is beautiful), in company with the libraries and churches, hospitals and heroes, the Cape Coast Castle platter strikes a discordant note. Yet it belongs beside them: the scene is intimately—irretrievably—associated with the new America.[3]

Imagine it enshrined on the top shelf of a dresser, one of those pieces that are reserved for best, taken down and used on special occasions, perhaps with some ceremony. Who dusts it? What is served on it? Who washes it afterward? What do they make of the imagery?

By the end of the nineteenth century American transferwares were keenly sought by collectors, and their subject matters were enthusiastically discussed in a range of publications. But the Cape Coast Castle platter was accorded comparatively little written comment. This essay is in part an attempt to address that lack and in part a way of negotiating my own bewildered, latter-day fascination with an extraordinary ceramic object.

The color is startling. For me when it comes to the printed surface, American transferwares represent the apogee of British factory production in the first half of the nineteenth century. They benefited from a number of new developments, including superior quality pigment.[4] The blue derives from cobalt, a metallic element, and a rich new vein had been dis- covered in Cornwall in or around 1807. It was processed at the British Cobalt Smelting Company, which was established in 1816 in Hanley, Staffordshire, conveniently close to Enoch Wood’s factory in Burslem.[5] This might not have been the factory’s only source; by 1835 there were at least twenty-five ceramic color manufacturers in the area, and that year the Blaafarveværket works in Norway exported some 86,000 kilograms of cobalt to English merchants.[6]

The blue of American transferware is more vibrant than the blue that was used for the home market. “Called by the Chinese ‘the light of heaven,’” gushes Alice Morse Earle in her 1892 account of China Collecting in America, “a blue like the lapis the Bishop wished for his tomb at St Praxed’s, a tint unexcelled and hardly equalled in modern wares . . . a never ceasing delight to the eye.”[7] Other period writers boost its mystique in terms of technical accomplishment, mythologizing the color as a lost art that “baffles our modern potters.” (fig. 2)[8]

The blue still exerts a charisma all its own; its power even seems amplified by today’s digital viewing practices. Setting out to research the Cape Coast Castle platter, I discover a perversity in its sumptuous visual character, capable of belying—of overriding—the subject matter. What is more, whether by accident or design, the right side of the castle building has been cropped, as one might crop a photograph. The notorious Door of No Return, through which the enslaved passed on their way to be transported, has disappeared beneath a decorative border whose lovely shell and seaweed grotto design hints at fairy tale. It is easy to forget that this is a piece of tableware, made to be handled as well as looked at. To reinforce my haptic memory, I ask ceramics practitioner Paul Scott—he who had introduced me to the platter—to weigh it; it came to 1920 grams (about 4 1/4 pounds), roughly equal to three of my biggest dinner plates.

American transferwares were intended for the dining table, and marks on many of their surfaces suggest that is exactly how they were used. Toward the end of the nineteenth century they were reimagined. As historian Anne Anderson observes, “A new pastime emerged, dubbed ‘china hunting’, with the attics of New England ransacked in search of Grandmother’s China.”[9]

China hunting had the thrill of a quest, and it was educational as well as exciting. The illustrations on these ceramics were now regarded as significant historical records: “faithful views taken from America itself, many of which . . . have been perpetuated in no other manner.”[10] Written accounts typically discuss the imagery at some length. Not so in the case of the Cape Coast Castle platter, despite its vast narrative potential. The lack of attention is telling.

Alice Morse Earle mentions a group of “very richly colored, clearly printed, and beautifully drawn pieces decorated with spirited marine views” by Enoch Wood & Sons. “These were evidently made for the American market, for on all of them appears prominently a full-rigged ship bearing the American flag.”[11] Her words are echoed in every historical publication I find. “Not only is [the flag] found on many views of ships in foreign ports” explains S. Robineau, “but on views in which the presence of an American ship seems impossible.” The flag is used simply “to make it as attractive to the American public and as saleable as possible.”[12] No attempt is made to interpret the Cape Coast Castle platter imagery. Nobody wonders whether the ship might be an American slaver. Yet it would have been feasible to identify it as such: although the American slave trade was outlawed in 1808, enslaved Africans continued to be smuggled into the United States until just before the start of the Civil War in 1861. In 1860 the New York Times declared that “nearly all the work [of the slave trade] is done under the American flag,—so much so that it is fair to presume, until the contrary is shown, that every vessel found on the coast of Africa carrying American colors is engaged in it.”[13]

Any representation with black figures, a foreign shore, and a sailing ship functions as a visual trope, an obvious reference to the slave trade.[14] The collectors probably did recognize the scene on the Cape Coast Castle platter. Their lack of written comment cannot be attributed to ignorance; more likely it was willful disregard, amounting to denial. “E. Wood & Sons produced many views of scenery characteristic of other countries,” states N. Hudson Moore in The Old China Book (1903). “They are to be found in considerable numbers, among them being such well-known places as Calcutta and ‘Cape Coast Castle on the Gold Coast, Africa.’”[15]

Nearly 120 years later, a reluctance to acknowledge the slave trade and its legacy persists. “I am a relic of an experience most preferred not to remember,” writes the contemporary African Diaspora author Saidiya Hartman, “as if the sheer will to forget could settle or decide the matter of history.”[16] During a year in Ghana, Hartman spent several weeks at Cape Coast. “No one imprisoned in the dungeon of Cape Coast Castle had ever described it,” she notes. “There was no record left behind by the captives.”[17] William St Clair, whose book The Door of No Return is a definitive text on Cape Coast Castle, confirms that he could only find one “autobiographical account” by an enslaved African that refers to it.[18]

On May 25, 2020, while I am writing this essay, an unarmed African American man named George Floyd is killed in police custody in Minneapolis. A bystander films the killing and posts the footage on social media. Black Lives Matter protests erupt across America and global repercussions follow. In Bristol, England, protestors pull down an iron statue of slave trader Edward Colston (1636–1721). They drag it across the paving stones and topple it into the river Avon, a stark reminder of how the bodies of dead and dying Africans were dumped overboard during the transatlantic voyage. Colston’s much-vaunted philanthropy depended on his business interests in the slave trade; today we would call it money laundering.

Paul Scott posts a photograph of his Cape Coast Castle platter on Instagram: “It has a direct link to toppled Bristol statue of slave trader #edwardcolston of the Royal African Company (1680–1692). . . . Its admin centre was #CapeCoastCastle (Ghana). Commenting on #UKBLM protests in the wake of #georgefloyd’s death. . . .”[19]

Now the platter is only masquerading as domestic tableware. It has become a portal into something and somewhere quite, quite other: a multifaceted site, a place where discourses collide and interweave. The more I search, the more there is to find.

The illustration on a piece of American transferware begins with a source image, from which an engraving is made on a copper plate. The plate is inked up in the traditional way and a tissue paper print is taken. This is smoothed onto the unglazed ceramic blank, transferring the ink of the design onto the ceramic surface, and the piece is glazed and fired.[20] The process is a form of remediation, whereby a motif produced in one medium is represented via another.

I discover the source image for the Cape Coast Castle platter in the British Library digital archive. It is a print after a painting by George Webster (active 1797–1832), engraved and aquatinted by John Hill (1770–1850), hand-colored by his wife, Anne Musgrove Hill (dates unknown), and published in October 1806 (figs. 3, 4). It is a faithful rendering of Webster’s original painting, which is in the collection of the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.[21] The Abolition of the Slave Trade Act was passed in March 1807, just five months after the print came out.

The sailing ship is more central to the composition on the platter than in the print. Importantly, the ship in the print is flying not the American flag, but the Red Ensign of a British merchant and there are sailors in blue uniform on deck. A large Union Jack hangs from the stern. The Door of No Return—absent from the platter—is clearly visible on the right side of the castle, and the figures in the small foreground vessel can be seen in more detail. Whereas they are dark silhouettes on the glazed ceramic surface, in the print they are wearing colored garments and something of their features can be discerned. By virtue of their dress and body language, to my eye they no longer look as if they are enslaved. Nor does the ship appear to be a slaver: there is nothing that betrays sinister purpose, everything about the scene is smoothly, peacefully ordered; on further consideration, perhaps too smoothly ordered.

Running along the bottom of the print is a fulsome dedication to Prince William, Duke of Clarence:

TO HIS ROYAL HIGHNESS THE DUKE OF CLARENCE,

This Plate is with His gracious permission humbly Dedicated by His Highnesses most obliged & devoted Servants, G. Webster & J. Barrow

Crowned King William IV in 1830, the Duke of Clarence (1765–1837) was a vociferous opponent of the Abolition movement whose maiden speech to the House of Lords was a detailed defense of the slave trade, breathtaking in its arrogance. He spoke of the “propagation” of “Negroes” as one might speak of breeding dogs or horses. The abolitionists had grossly misrepresented the situation, he claimed: British traders complied willingly with the latest regulations that governed the transport of slaves and ensured adequate breathing space; it was not in their interests to do otherwise, “to prevent diseased and infected Negroes from being imported into the British West India Plantations.”[22] As for British plantation owners, he had served in the navy, had been “resident for some years amongst those West India planters,” and could therefore “bear witness to their good conduct, to their humanity, and to the care and attention of their Slaves.”[23]

Despite appearances, the sailing ship in the source image for the Cape Coast Castle platter is a British slaver. The print is one of a series of four with views of West African slave forts from the sea, after paintings by George Webster. All are dedicated to the Duke of Clarence. They were part of a propaganda campaign for the continuation of the slave trade, and they promote what William St Clair calls “a vision of West Africa as calm and peaceful and exotic—with no slave trade shown directly.”[24] Gone is the heavy surf reported by other eyewitnesses.[25] Nor is there any sign of the many vessels that would have been spread out across the “roads,” a stretch of water extending some four miles offshore. The lyrical view disguises the density of shipping as well as its purpose. “Most of the slave ships stayed anchored in the roads at Cape Coast . . . for many months,” explains St Clair.[26] He suggests that the print may have been tailored to suit individual customers, with the sailors’ uniforms colored in either the red of the Africa Service or the blue of the Royal Navy.[27]

The dedication to the Duke of Clarence is prominent, and—the duke’s pro-slavery stance being well known—the message of the print is clear. Enoch Wood was a religious man, a pillar of Staffordshire society, a friend of Wesley, an abolitionist, so what prompted him to choose it for the platter? The disjunction is unsettling. On a pragmatic level, he was also a shrewd businessman, the image is seductive, and the print series came out of copyright in 1820 (fig. 5).

It is tempting to lean on Wood’s abolitionism in search of a more meaningful answer. Although the 1807 act outlawed the Slave Trade, slavery was not banned throughout the British Empire until the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833. In the interim, the West Africa Squadron of the British Navy was formed to police the West African coast and intercept slave ships. In 1819 the Squadron was joined by United States Navy warships known as the African Slave Trade Patrol. Flying the American flag, the sailing ship on the Cape Coast Castle platter tells the story. Was that Enoch Wood’s intention, or is it merely a side effect of enhancing the platter’s salability? Is this interpretive hindsight? History is constantly remade and what we understand of the past is subject to shifts and revisions; the significance of the imagery today surely exceeds anything he could have anticipated.

At least two more pieces by Enoch Wood & Sons are illustrated with views of slave forts from the same print series. One is a platter called Christianburg Danish Settlement on the Gold Coast Africa. Similar in size and form to the Cape Coast Castle platter, it depicts a Danish slave fort that was established in the 1660s (fig. 6). Again the British flags have been replaced by American flags. Apart from the slight misspelling of the settlement name, the title is the same as the print source (fig. 7), but the title of the original painting in the Danish Maritime Museum is more forthright: Two British Slave Ships at Christiansborg (fig. 8).[28]

Who were the first users of American transferware? According to the china hunters they were country folk. “ . . . there yet remains in country homes throughout the eastern states,” observes Ada Walker Camehl as late as 1916, “in the oft-times careless possession of descendants of original owners, a harvest sufficient to tempt the admirer of ‘old blue.’”[29]

By china hunters I mean the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth-century collectors, several of whose commentaries I mentioned earlier. They were city dwellers who sought out historical ceramics in rural locations, and their accounts often interweave ceramics-specific information with anecdotes about country life. One of the china hunters, Alice Morse Earle, is considered to have “significantly advanced the scholarship about ceramic wares made or used in America.”[30] She spent time conversing with people who were willing to part with their family china, recognizing that “it is a pleasure, a treat, to most farm-wives to receive such a visit.”[31]

“I always delight to ask a Yankee farmer, in field or road, whether he has any old crockery that he would be willing to part with,” Earle remarks, explaining that “he will skurry home ‘cross-lots,’ over the ploughed fields, or through the rows of growing corn, eager to pull out and sell his wife’s pantry treasures.”[32] Such treasures typically included American transferwares that had been acquired for domestic use by earlier generations of the family. One might speculate as to what those original owners would have made of the Cape Coast Castle platter. When they passed it down the dining table, would they have viewed the imagery in full recognition of its meaning?

What if the people at the table were slaveholders? Or enslaved Africans? Archaeological analyses of American plantation sites have established that transferware was present in significant quantities in the homes of both the planters and the enslaved. Charles H. Fairbanks, for example, reported, “ceramics, glass, and food bones that represented the daily discards of an elite household that entertained widely and richly. . . . Beef, pork, and venison were eaten in the form of roasts served from platters onto transfer-printed pearlware plates in matching sets.”[33]

Of the fragments (called sherds by the archaeologists) found at the site of another plantation house, John Solomon Otto identified 1,520 that were transfer-printed, and from those 185 tableware forms and 60 patterns were recognized. At the site of the slave quarters, 33 forms and 30 patterns were recognized from 154 transfer-printed fragments.[34] Predictably, the more elaborate and expensive ceramics belonged to the planters. The Cape Coast Castle platter would fall into that group. Large flatwares are not generally associated with slave sites, in part due to dietary factors: enslaved Africans were much less likely to eat the roast meats that would have been served on a platter of this size. It is reasonable to assume, however, that they would have handled it, perhaps held it steady while their owners served themselves. Trusted house servants (enslaved nevertheless) would have taken it from the table after the meal, washed it, and put it away. In her research on “Master-Slave Relations,” Ywone Edwards-Ingram found that obedient enslaved servants were rewarded with material goods, including ceramics.[35] Some enslaved households were provided with bought tableware, and some also received hand-me-downs. Slaveholders believed caring for ceramics was part of a “civilizing” process—a problematic paternalistic attitude that went hand in hand with fictional notions of “the contented and happy slave.”[36] The voices of the enslaved are few and far between.[37]

Irrespective of its imagery, factory-made tableware scores poorly when it comes to cultural status. Some two hundred years after they were first produced, American transferwares have not accumulated a corresponding depth of scholarly consideration; their histories are scattered. I find myself wading through auction sites and collectors’ websites as well as museum archives, gathering fragments of information in a kind of montage, or a jigsaw puzzle that I can never complete.

A photograph in an album from about 1930 shows the Cape Coast Castle platter on a shelf in the Aldrich family mansion in Warwick, Rhode Island (fig. 9).[38] It was among 250 pieces of American transferware donated to the Rhode Island School of Design Museum (RISD) in 1938 by businessman and publisher Edward B. Aldrich (1871–1957).[39] His father was U.S. Senator Nelson Aldrich (1841–1915), a man with enormous political in- fluence. Both men had connections to Africa: Edward was president of the American Congo Company and vice-president of the International Rubber Company.[40] Perhaps the platter reflected his African interests, but other photographs suggest it was one of very many pieces that were systematically collected and displayed in sets. Following the Aldrich bequest, the platter remained in the RISD museum storage for more than eighty years.

Today, as in the past, many collectors group American transferwares according to border design. The Cape Coast Castle platter belongs to “Wood’s Irregular Shell Border series,” which is thought to form a dinner service of about thirty-five different maritime scenes.[41] The table would be laid with an interesting, if eccentric, mixture: slave forts dressed as exotic foreign views rubbing shoulders with, say, the Marine Hospital in Louisville, Kentucky, or Commodore MacDonnough’s victory against the British in the war of 1812, or the Eddystone lighthouse off the coast of Devon, England. In the discourses of collecting, factors like the identification of a theme, classification, and collecting in series predominate; they encourage a particular mindset, deflecting the attention and glossing over the content of individual pieces. Familiarity sometimes breeds not exactly contempt, but a kind of flattening.

I too have collected facts, assembled evidence. By now I know something about the Cape Coast Castle platter. But I have not come to terms with it. Those dark figures in the small boat approaching the sailing ship, are they enslaved Africans? To engage with this object necessitates a process of witnessing:

we cast anchor in the roads before Cape Coast. I did not go on shore until the next day and had ample time to contemplate the lovely appearance this place presents when viewed from the sea. The castle, which is a large white stone building, and surrounded by curtains, bastions &c is partly erected on a rock called the Tarbara. The native houses, interspersed with the more tasteful dwellings of European merchants, lie to the right; and everywhere the hills rise from the water’s edge, covered with the richest and most luxuriant forest.[42]

This was Sarah Bowdich’s first sight of Cape Coast Castle. She traveled there from England in 1816 to join her husband, Thomas Edward Bowdich, who was employed by the Africa Company to lead a trade mission to the Ashantee people. A respected naturalist as well as an intrepid traveler, Sarah published a description of her voyage and a series of accounts of her two years in West Africa.[43]

She sailed from Liverpool, arriving thirty-three days later at the island of Gorée, Senegal. From Gorée they continued to the Isles de Los, off Guinea, and on to Sierra Leone. There she transferred to a Spanish brig that been captured “in the act of conveying slaves” by a British patrol.[44] The vessel bears comparison with the sailing ship depicted on the Cape Coast Castle platter, but Bowdich supplies visceral elements that undermine the harmonious image. The floor of the hold being full, enslaved Africans were forced to perch on “bits of wood, which stick out from the sides . . . all the fresh comers would be made to sit on these, like a parcel of monkeys or birds.”[45]

Is the ship depicted on the platter fitted out in this way? In some ineffable dimension beneath the glaze, does it stink? There is a ghastly poetic justice in her description of silver spoons—a symbol of wealth—tainted by the slave trade that literally is enacted on their surfaces.

the smell of bilge water infected the whole brig . . . so strong was the vapour arising from it that the silver spoons could not lie on the table for five minutes without turning perfectly black.[46]

She decries “that abominable traffic which was so long a disgrace to civilization.”[47] Past tense. But it was not in the past. Her husband complains that “One thousand slaves left Ashantee for two Spanish schooners or Americans under that flag, to our knowledge, during our residence there.” The continuing trade is an obstacle in his dealings with the Ashantee.[48] Sarah tells of a young woman kidnapped from her village and marched in a coffle with others to the coast, a journey of many days, to be sold to “slave-shippers”: “Their flesh was mangled by thorns, their feet swollen by fatigue; their unwashed skins were cracked by the sun . . . .” At night they were hidden underground or in makeshift forest shelters. “The port for which they were destined lay at the foot of the hill . . . beyond was the sea, and on it a large vessel and numerous small craft were riding at anchor.”[49]

Again I ask myself, those figures in the small boat approaching the sailing ship on the Cape Coast Castle platter. Are they enslaved Africans? I believe they are. Looking at the print source, I had taken dress and body language as a sign that they were not. But Bowdich’s informant explains that when captives arrived at the coast,

they were completely unbound and washed; their skins were impregnated with perfumed vegetable butter . . . their legs were rubbed to reduce them to their natural size; and when, after some days, they were thought to be sufficiently recovered from their journey, they were dressed for the market.[50]

Just as the treatment disguises their kidnapping and enslavement, so does the Cape Coast Castle platter offer a beautiful deception. At times it seems like something monstrous lurking in plain sight, a presence that goes unremarked by common consent. Yet when I look again, it is still a lovely thing. The dearth of interpretation, the reluctance to acknowledge the significance of the platter imagery on the part of a generation of collectors, is not surprising. In their hands it becomes one of a set, another decorative ceramic object, filed under “Miscellaneous Foreign Views, dark blue.”[51] It is easier that way.

Recent debates about public monuments expose deep rifts between what was once thought proper (or went unquestioned) and what is acceptable today. A lot of the discussion concerns statuary memorializing historical figures connected to the slave trade, such as Edward Colston.

How should we deal with the Cape Coast Castle platter? Like the statues, it is hugely over-determined in its normalization of a racist, imperialist past. Should it be broken? Hidden away? How could it be neutralized? Some may say that there is no need to deal with it: this is just a piece of ceramic tableware and tableware hardly plays a significant role in world affairs.

Ceramics history can get lost in the gaps between disciplines, and it sometimes runs afoul of cultural hierarchies, especially when its field of operation is the domestic interior. But tableware attends the most basic of human functions, and many people remember the bowls and plates they used as children. Those things that surround us in the home, things we keep and care for, wield a subtle, penetrating power. As Susan Stewart writes, “the what-everyone-knows does not need to be articulated. Yet those unarticulated assumptions are in fact the most profoundly ideological of all, for they suffuse every aspect of consciousness.”[52] No amount of gloss, no brilliance of hue, can disguise the undigested—and indigestible—histories congealed around the Cape Coast Castle platter. There are people alive today whose great-great-grandparents were imprisoned aboard this ship—or one very like it—closely packed, and shackled for weeks on end.[53]

1. I am grateful to Paul Scott for introducing me to the platter. This essay is an offshoot of my earlier essay titled “On the Threshold: Paul Scott New American Scenery” (available online at https://cumbrianblues.com/2020/08/05/on-the-threshold-a-recently-published-essay-by -dr-jo-dahn-on-new-american-scenery/). Scott’s “New American Scenery” project involves altered examples of antique American transferware alongside new work. It is currently on display at the Rhode Island School of Design Museum. Part of the installation features the Cape Coast Castle platter from the RISD collection (RISD 35.195). 2. Platter is a contemporary term; in the period this would have been referred to as a dish. 3. For further information and many examples of American transfer-printed earthenware, see “Patriotic America: Blue Printed Pottery Celebrating a New Nation,” http://www.american historicalstaffordshire.com/. Other transfer-printed ceramics exported from Britain to the United States during this period typically feature floral, landscape, and chinoiserie designs. 4. “The refining of the cobalt that was used in the printing colour and the improvements in the tissue paper produced a synergistic advance within the whole transferware industry.” Richard Halliday, The Transferware Engraver: Training, Practice and Scope at the Spode Works (Ph.D. thesis, Manchester Metropolitan University, 2018), p. 99. 5. Josiah Wedgwood II signed a testimonial to its superiority in 1817. See http://printedbritishpotteryandporcelain.com/pottery/ceramics/blue-printed-earthenware-19th-century. Enoch Wood & Sons operated one of the largest potteries in Staffordshire at Fountain Place, Burslem, from about 1818 until 1846. They are considered to have led in targeting the American market. 6. I am grateful to Paul Scott for this information. Research is ongoing. 7. Alice Morse Earle, China Collecting in America (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1892), p. 316. 8. Edwin Atlee Barber, Anglo-American Pottery: Old English China with American Views, a Manual for Collectors (Indianapolis, Ind.: Press of the Clay-Worker, 1899), p. 22; Richard Townley Haines Halsey, Pictures of Early New York, on Dark Blue Staffordshire Pottery, Together with Pictures of Boston and New England, Philadelphia, and the South and West (1899; reprint with new introduction, New York: Dover Publications, 1974), p. 276n. 9. Anne Anderson, “The Romance of Old Blue: Collecting and Displaying Old Blue Staffordshire China in the American Home c1870–1938,” Interpreting Ceramics, no. 15 (2013), http://www.interpretingceramics.com/issue015/articles/03.htm. 10. Ada Walker Camehl, The Blue-China Book: Early American Scenes and History Pictured in the Pottery of the Time . . . (New York: E. P Dutton & Co., 1916), introduction. 11. Earle, China Collecting in America, pp. 325–26. 12. S. Robineau, “A Puzzling Series of Dark Blue,” Old China 1, no. 6 (1902): 85–87. 13. “The American Flag and the African Slave-trade,” New York Times, March 19, 1860, p. 4, available online at https://www.nytimes.com/1860/03/19/archives/the-american-flag -and-the-african-slavetrade.html. 14. Sam Margolin’s selection of antislavery ceramics includes a ca. 1840 child’s mug illustrated with just such a image, and a ca. 1800 enamel patch box showing an enslaved African in chains with ship and shore behind. Margolin, “‘And Freedom to the Slave’: Antislavery Ceramics, 1787–1865,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2002), available online at http://www.chipstone.org/article.php/39/Ceramics-in-America-2002/%E2%80%9CAnd-Free dom-to-the-Slave%E2%80%9D:-Antislavery-Ceramics,-1787%E2%80%931865. 15. N. Hudson Moore, The Old China Book: Including Staffordshire, Wedgwood, Lustre, and Other English Pottery and Porcelain (New York: Frederick A. Stokes Co., 1903), p. 26 (emphasis added). 16. Saidiya Hartman, Lose Your Mother: A Journey along the Atlantic Slave Route (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007), p. 18. “Slavery had established a measure of man and a ranking of life and worth that has yet to be undone. . . . As both a Professor conducting research on slavery and a descendant of the enslaved, I was desperate to reclaim the dead, that is, to reckon with the lives undone and obliterated in the making of human commodities.” Ibid., p. 6. 17. Ibid., p. 121. 18. William St Clair, The Door of No Return: The History of Cape Coast Castle and the Atlantic Slave Trade (2007; paperback ed., New York: BlueBridge, 2009), p. 242. The account was written by Quobna Ottobah Cugoano (ca. 1757–ca. 1791), who was imprisoned in another of the slave forts on the African coast in 1770. Quobna Ottobah Cugoano, Thoughts and Sentiments on the Evil and Wicked Traffic of the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species: Humbly Submitted to the Inhabitants of Great Britain (1797; reprint, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013), p. 9, available online at https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e /eccodemo/K046227.0001.001/1:5?rgn=div1;view=fulltext. In 1810, “after the last men, women and children had left the Castle dungeons, the floor was spread with lime and sand as part of the cleansing.” St Claire, Door of No Return, p. 244. 19. https://www.instagram.com/cumbrianblue_s/?hl=en, posted on June 16, 2020. 20. The process of transfer-printing on English ceramics is discussed in numerous publications. See, e.g., Robert Copeland, Blue and White Transfer-printed Pottery, 2nd ed. (Princes Risborough: Shire Publications, 2000). 21. https://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/241131.html. The painting Webster exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1800 was listed as “Cape Coast Castle, on the Coast of Guinea” (RA 671). He specialized in marine subjects; he was in West Africa at the turn of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and made several paintings of slave forts from the sea. In 1816 the engraver John Hill emigrated to America. He went on to produce the Hudson River Portfolio, a series of prints after watercolors by William Guy Wall, which were in turn used as source imagery by Staffordshire potter James Clews for a series of American transferwares titled Picturesque Views. 22. The so-called Carrying Bill of July 1799, “An Act for better regulating the Manner of Carrying Slaves in British Vessels, from the Coast of Africa,” available online at https://www .pdavis.nl/Legis_29.htm. 23. William, Duke of Clarence, “Substance of the speech of His Royal Highness the Duke of Clarence, in the House of Lords, on the motion for the recommitment of the slave trade limitation bill, on the fifth day of July, 1799,” available online at https://en.wikisource.org /wiki/Substance_of_the_speech_of_His_Royal_Highness_the_Duke_of_Clarence,_in_the _House_of_Lords. 24. E-mail sent by William St Clair to author, June 22, 2020. It is possible that the prints were commissioned by the Duke of Clarence. I am grateful to William St Clair for discussion about them. 25. “No European boat can live in that at Cape Coast and passengers and goods are consigned to canoes, which swim at the top of the foam.” Mrs. R. Lee (formerly Sarah Bowdich), Stories of Strange Lands and Fragments from the Notes of a Traveller (London: Edward Moxon, 1835), p. 125. 26. St Clair, Door of No Return, pp. 14–19. 27. Ibid., p. 265. 28. The third piece is a lidded tureen titled Dixcove on the Gold Coast, Africa.[ ]Dixcove was a British slave fort that offered sheltered anchorage where ships could embark and disembark cargo, undergo repair, take on provisions, and so forth. Enslaved Africans were traded there and kept in a holding dungeon. See Louis P. Nelson, “Architectures of West African Enslavement,” Buildings & Landscapes: Journal of the Vernacular Architecture Forum 21, no. 1 (Spring 2014): pp. 88–125, available online at https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749 /buildland.21.1.0088. 29. Camehl, Blue-China Book, p. xvi. 30. Susan Reynolds Williams, Alice Morse Earle and the Domestic History of Early America (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2013), p. 106. Earle adopted “an increasingly ethnographic historical methodology, which supplemented traditional archival sources with material evidence.” Ibid., p. 108. 31. Earle, China Collecting in America, p. 14. 32. Ibid., p. 13. 33. Charles H. Fairbanks, “The Plantation Archaeology of the Southeastern Coast,” Historical Archaeology 18, no. 1 (1984): 1–14. 34. John Solomon Otto, Cannon’s Point Plantation, 1794–1860: Living Conditions and Status Patterns in the Old South (New York: Academic Press, 1984), pp. 66, 151–52. 35. Ywone Edwards-Ingram, “Master-Slave Relations: A Williamsburg Perspective” (master’s thesis, College of William & Mary, 1990). 36. Ibid., p. 69. Some so-called benevolent owners allowed enslaved servants to sell garden produce; they may have spent their earnings on ceramics. See also James M. Clifton, “Hopeton, Model Plantation of the Antebellum South,” Georgia Historical Quarterly 66, no. 4 (Winter 1982): 429–49. 37. Sadly, even Edwards-Ingram’s detailed analysis of the material culture relating to Polly Valentine, a favored enslaved house servant, is not able to recuperate her voice. Edwards- Ingram, “Master-Slave Relations,” chap. 3. 38. See a photograph album of the Nelson W. Aldrich Residence, Warwick Neck, Rhode Island, at Historic New England’s website, https://www.historicnewengland.org/explore /collections-access/capobject/?refd=PC009.228H. 39. For an image of the platter, see https://risdmuseum.org/art-design/collection/cape-coast -castle-gold-coast-africa-platter-printed. 40. These companies have been criticized for their toleration of appalling working conditions and the extreme cruelty of Leopold II’s regime. See, e.g., Tim Harford, “The Horrific Consequences of Rubber’s Toxic Past,” BBC News, July 23, 2019, available online at https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-48533964; and, Robert Wuliger, “America’s Early Role in the Congo Tragedy,” Nation (October 10, 2007), available online at https://www.thenation.com /authors/robert-wuliger/. 41. Opinions vary. Jeffrey B. Snyder lists only twenty-eight views under the rubric “Shell Border, Irregular or Grotto-shaped Center.” Jeffrey B. Snyder, Historical Staffordshire: American Patriots & Views (Atglen, Pa.: Schiffer, 1995), p. 139. Ellouise Baker Larsen lists some forty-six pieces with shell borders, though not all show maritime scenes. Larsen, American Historical Views on Staffordshire China, 3d ed. (New York: Dover Publications, 1975), pp. 9–31. The Transferware Collectors Club Database lists thirty-five patterns made by Enoch Wood & Sons with the “Shell Border, Irregular or Grotto-Shaped Center”; Transferware Collectors Club Database, https://www.transferwarecollectorsclub.org/tcc2/data/borders/nautical -themes/shells/shell-border-irregular-or-grotto-shaped-center-enoch-wood-sons/. 42. Lee, Stories of Strange Lands, p. 288. When she went ashore she found a damp building infested with rats, termites, and a variety of biting insects. 43. Sarah Bowdich sometimes crafted stories from her experiences, but she was careful to state that “every description of scenery, manners, and customs has been taken from the life.” Ibid., p. XIV. 44. Ibid., p. 323. The enslaved Africans who had been crammed into the hold were taken to Sierra Leone. 45. Ibid., p. 99. 46. Ibid., p. 293. 47. Ibid., p. 132. 48. T. Edward Bowdich, Mission from Cape Coast Castle to Ashantee (London: John Murray, 1819), p. 339. 49. Lee, Stories of Strange Lands, pp. 95–97. 50. Ibid., p. 97. 51. Barber, Anglo-American Pottery, p. 160. 52. Susan Stewart, On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection (1984; 1st pbk. ed., Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1993), p. 25. 53. “. . . stored so close, as to admit of no other posture than lying on their sides.” Ship’s surgeon Alexander Falconbridge’s 1788 An Account of the Slave Trade on the Coast of Africa, included in Narrative of Two Voyages to the River Sierra Leone during the Years 1791-1792-1793 (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2000), p. 207. For latter-day consideration of the Transatlantic Middle Passage and its persistence in memory, see Andrew Apter and Lauren Derby, eds., Activating the Past: History and Memory in the Black Atlantic World (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars, 2010), introduction.

I am grateful to Paul Scott for introducing me to the platter. This essay is an offshoot of my earlier essay titled “On the Threshold: Paul Scott New American Scenery” (available online at https://cumbrianblues.com/2020/08/05/on-the-threshold-a-recently-published-essay-by-dr-jo-dahn-on-new-american-scenery/). Scott’s “New American Scenery” project involves altered examples of antique American transferware alongside new work. It is currently on display at the Rhode Island School of Design Museum. Part of the installation features the Cape Coast Castle platter from the RISD collection (RISD 35.195).

Platter is a contemporary term; in the period this would have been referred to as a dish.

For further information and many examples of American transfer-printed earthenware, see “Patriotic America: Blue Printed Pottery Celebrating a New Nation,” http://www.american historicalstaffordshire.com/. Other transfer-printed ceramics exported from Britain to the United States during this period typically feature floral, landscape, and chinoiserie designs.

“The refining of the cobalt that was used in the printing colour and the improvements in the tissue paper produced a synergistic advance within the whole transferware industry.” Richard Halliday, The Transferware Engraver: Training, Practice and Scope at the Spode Works (Ph.D. thesis, Manchester Metropolitan University, 2018), p. 99.

Josiah Wedgwood II signed a testimonial to its superiority in 1817. See http://printedbritishpotteryandporcelain.com/pottery/ceramics/blue-printed-earthenware-19th-century. Enoch Wood & Sons operated one of the largest potteries in Staffordshire at Fountain Place, Burslem, from about 1818 until 1846. They are considered to have led in targeting the American market.

I am grateful to Paul Scott for this information. Research is ongoing.

Alice Morse Earle, China Collecting in America (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1892), p. 316.

Edwin Atlee Barber, Anglo-American Pottery: Old English China with American Views, a Manual for Collectors (Indianapolis, Ind.: Press of the Clay-Worker, 1899), p. 22; Richard Townley Haines Halsey, Pictures of Early New York, on Dark Blue Staffordshire Pottery, Together with Pictures of Boston and New England, Philadelphia, and the South and West (1899; reprint with new introduction, New York: Dover Publications, 1974), p. 276n.

Anne Anderson, “The Romance of Old Blue: Collecting and Displaying Old Blue Staffordshire China in the American Home c1870–1938,” Interpreting Ceramics, no. 15 (2013), http://www.interpretingceramics.com/issue015/articles/03.htm.

Ada Walker Camehl, The Blue-China Book: Early American Scenes and History Pictured in the Pottery of the Time . . . (New York: E. P Dutton & Co., 1916), introduction.

Earle, China Collecting in America, pp. 325–26.

S. Robineau, “A Puzzling Series of Dark Blue,” Old China 1, no. 6 (1902): 85–87.

“The American Flag and the African Slave-trade,” New York Times, March 19, 1860, p. 4, available online at https://www.nytimes.com/1860/03/19/archives/the-american-flag -and-the-african-slavetrade.html.

Sam Margolin’s selection of antislavery ceramics includes a ca. 1840 child’s mug illustrated with just such a image, and a ca. 1800 enamel patch box showing an enslaved African in chains with ship and shore behind. Margolin, “‘And Freedom to the Slave’: Antislavery Ceramics, 1787–1865,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2002), available online at http://www.chipstone.org/article.php/39/Ceramics-in-America-2002/%E2%80%9CAnd-Freedom-to-the-Slave%E2%80%9D:-Antislavery-Ceramics,-1787%E2%80%931865.

N. Hudson Moore, The Old China Book: Including Staffordshire, Wedgwood, Lustre, and Other English Pottery and Porcelain (New York: Frederick A. Stokes Co., 1903), p. 26 (emphasis added).

Saidiya Hartman, Lose Your Mother: A Journey along the Atlantic Slave Route (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007), p. 18. “Slavery had established a measure of man and a ranking of life and worth that has yet to be undone. . . . As both a Professor conducting research on slavery and a descendant of the enslaved, I was desperate to reclaim the dead, that is, to reckon with the lives undone and obliterated in the making of human commodities.” Ibid., p. 6.

Ibid., p. 121.

William St Clair, The Door of No Return: The History of Cape Coast Castle and the Atlantic Slave Trade (2007; paperback ed., New York: BlueBridge, 2009), p. 242.

The account was written by Quobna Ottobah Cugoano (ca. 1757–ca. 1791), who was imprisoned in another of the slave forts on the African coast in 1770. Quobna Ottobah Cugoano, Thoughts and Sentiments on the Evil and Wicked Traffic of the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species: Humbly Submitted to the Inhabitants of Great Britain (1797; reprint, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013), p. 9, available online at https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eccodemo/K046227.0001.001/1:5?rgn=div1;view=fulltext.

In 1810, “after the last men, women and children had left the Castle dungeons, the floor was spread with lime and sand as part of the cleansing.” St Claire, Door of No Return, p. 244.

https://www.instagram.com/cumbrianblue_s/?hl=en, posted on June 16, 2020.

The process of transfer-printing on English ceramics is discussed in numerous publications. See, e.g., Robert Copeland, Blue and White Transfer-printed Pottery, 2nd ed. (Princes Risborough: Shire Publications, 2000).

https://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/241131.html. The painting Webster exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1800 was listed as “Cape Coast Castle, on the Coast of Guinea” (RA 671). He specialized in marine subjects; he was in West Africa at the turn of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and made several paintings of slave forts from the sea. In 1816 the engraver John Hill emigrated to America. He went on to produce the Hudson River Portfolio, a series of prints after watercolors by William Guy Wall, which were in turn used as source imagery by Staffordshire potter James Clews for a series of American transferwares titled Picturesque Views.

The so-called Carrying Bill of July 1799, “An Act for better regulating the Manner of Carrying Slaves in British Vessels, from the Coast of Africa,” available online at https://www.pdavis.nl/Legis_29.htm.

William, Duke of Clarence, “Substance of the speech of His Royal Highness the Duke of Clarence, in the House of Lords, on the motion for the recommitment of the slave trade limitation bill, on the fifth day of July, 1799,” available online at https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Substance_of_the_speech_of_His_Royal_Highness_the_Duke_of_Clarence,_in_the _House_of_Lords.

E-mail sent by William St Clair to author, June 22, 2020. It is possible that the prints were commissioned by the Duke of Clarence. I am grateful to William St Clair for discussion about them.

“No European boat can live in that at Cape Coast and passengers and goods are consigned to canoes, which swim at the top of the foam.” Mrs. R. Lee (formerly Sarah Bowdich), Stories of Strange Lands and Fragments from the Notes of a Traveller (London: Edward Moxon, 1835), p. 125.

St Clair, Door of No Return, pp. 14–19.

Ibid., p. 265.

The third piece is a lidded tureen titled Dixcove on the Gold Coast, Africa. Dixcove was a British slave fort that offered sheltered anchorage where ships could embark and disembark cargo, undergo repair, take on provisions, and so forth. Enslaved Africans were traded there and kept in a holding dungeon. See Louis P. Nelson, “Architectures of West African Enslavement,” Buildings & Landscapes: Journal of the Vernacular Architecture Forum 21, no. 1 (Spring 2014): pp. 88–125, available online at https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/buildland.21.1.0088.

Camehl, Blue-China Book, p. xvi.

Susan Reynolds Williams, Alice Morse Earle and the Domestic History of Early America (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2013), p. 106. Earle adopted “an increasingly ethnographic historical methodology, which supplemented traditional archival sources with material evidence.” Ibid., p. 108.

Earle, China Collecting in America, p. 14.

Ibid., p. 13.

Charles H. Fairbanks, “The Plantation Archaeology of the Southeastern Coast,” Historical Archaeology 18, no. 1 (1984): 1–14.

John Solomon Otto, Cannon’s Point Plantation, 1794–1860: Living Conditions and Status Patterns in the Old South (New York: Academic Press, 1984), pp. 66, 151–52.

Ywone Edwards-Ingram, “Master-Slave Relations: A Williamsburg Perspective” (master’s thesis, College of William & Mary, 1990).

Ibid., p. 69. Some so-called benevolent owners allowed enslaved servants to sell garden produce; they may have spent their earnings on ceramics. See also James M. Clifton, “Hopeton, Model Plantation of the Antebellum South,” Georgia Historical Quarterly 66, no. 4 (Winter 1982): 429–49.

Sadly, even Edwards-Ingram’s detailed analysis of the material culture relating to Polly Valentine, a favored enslaved house servant, is not able to recuperate her voice. Edwards-Ingram, “Master-Slave Relations,” chap. 3.

See a photograph album of the Nelson W. Aldrich Residence, Warwick Neck, Rhode Island, at Historic New England’s website, https://www.historicnewengland.org/explore/collections-access/capobject/?refd=PC009.228H.

For an image of the platter, see https://risdmuseum.org/art-design/collection/cape-coast-castle-gold-coast-africa-platter-printed.

These companies have been criticized for their toleration of appalling working conditions and the extreme cruelty of Leopold II’s regime. See, e.g., Tim Harford, “The Horrific Consequences of Rubber’s Toxic Past,” BBC News, July 23, 2019, available online at https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-48533964; and, Robert Wuliger, “America’s Early Role in the Congo Tragedy,” Nation (October 10, 2007), available online at https://www.thenation.com/authors/robert-wuliger/.

Opinions vary. Jeffrey B. Snyder lists only twenty-eight views under the rubric “Shell Border, Irregular or Grotto-shaped Center.” Jeffrey B. Snyder, Historical Staffordshire: American Patriots & Views (Atglen, Pa.: Schiffer, 1995), p. 139. Ellouise Baker Larsen lists some forty-six pieces with shell borders, though not all show maritime scenes. Larsen, American Historical Views on Staffordshire China, 3d ed. (New York: Dover Publications, 1975), pp. 9–31. The Transferware Collectors Club Database lists thirty-five patterns made by Enoch Wood & Sons with the “Shell Border, Irregular or Grotto-Shaped Center”; Transferware Collectors Club Database, https://www.transferwarecollectorsclub.org/tcc2/data/borders/nautical -themes/shells/shell-border-irregular-or-grotto-shaped-center-enoch-wood-sons/.

Lee, Stories of Strange Lands, p. 288. When she went ashore she found a damp building infested with rats, termites, and a variety of biting insects.

Sarah Bowdich sometimes crafted stories from her experiences, but she was careful to state that “every description of scenery, manners, and customs has been taken from the life.” Ibid., p. XIV.

Ibid., p. 323. The enslaved Africans who had been crammed into the hold were taken to Sierra Leone.

Ibid., p. 99.

Ibid., p. 293.

Ibid., p. 132.

T. Edward Bowdich, Mission from Cape Coast Castle to Ashantee (London: John Murray, 1819), p. 339.

Lee, Stories of Strange Lands, pp. 95–97.

Ibid., p. 97.

Barber, Anglo-American Pottery, p. 160.

Susan Stewart, On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection (1984; 1st pbk. ed., Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1993), p. 25.

“. . . stored so close, as to admit of no other posture than lying on their sides.” Ship’s surgeon Alexander Falconbridge’s 1788 An Account of the Slave Trade on the Coast of Africa, included in Narrative of Two Voyages to the River Sierra Leone during the Years 1791-1792-1793 (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2000), p. 207. For latter-day consideration of the Transatlantic Middle Passage and its persistence in memory, see Andrew Apter and Lauren Derby, eds., Activating the Past: History and Memory in the Black Atlantic World (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars, 2010), introduction.