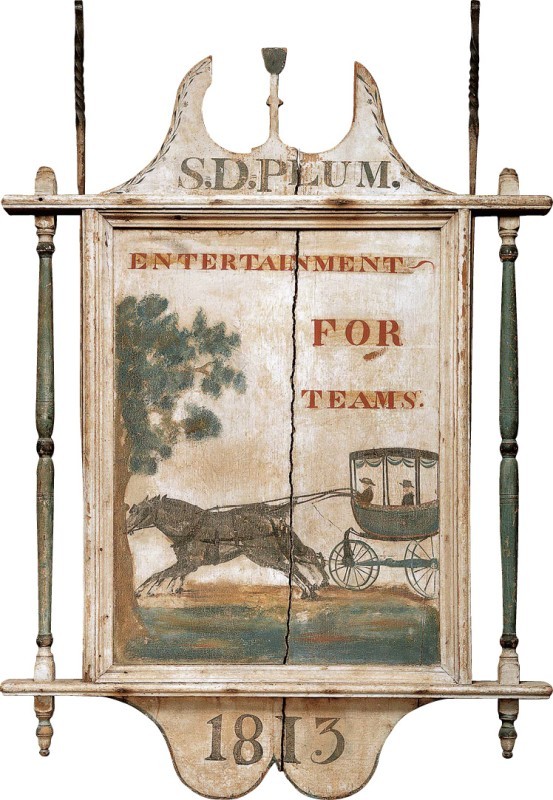

S. D. Plum tavern sign (double-sided, recto), probably Meriden, Connecticut, 1813. Paint on pine with iron. H. 51", W. 34", D. 3". (Courtesy, American Folk Art Museum, gift

of Ralph Esmerian, acc. 2013.1.55; photo, 2000 John Bigelow Taylor; Art Resource, New York.)

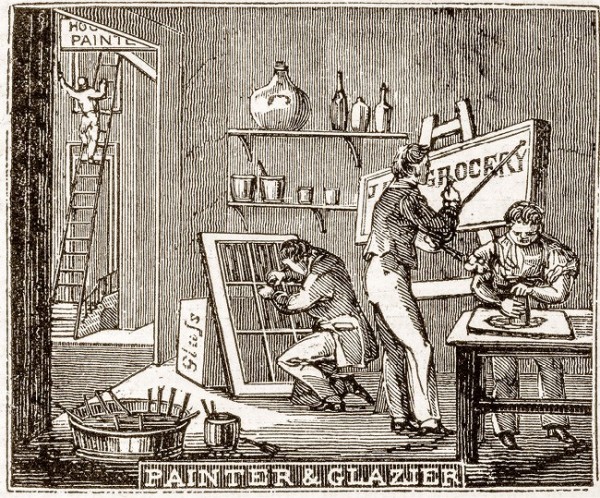

Shop of the Painter and Glazier, in Edward Hazen, The Panorama of Professions and Trades (Philadelphia: U. Hunt, 1839), p. 215. (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Printed Book

and Periodical Collection.)

Jeweler’s trade sign, Louis Fremeau, Burlington, Vermont, nineteenth century. Carved and painted wood. H. 22", Diam. 15". (Courtesy, Collection of Shelburne Museum, gift of Mrs. Louis Fremeau, acc. 1958-5.2; photo, Andy Duback.)

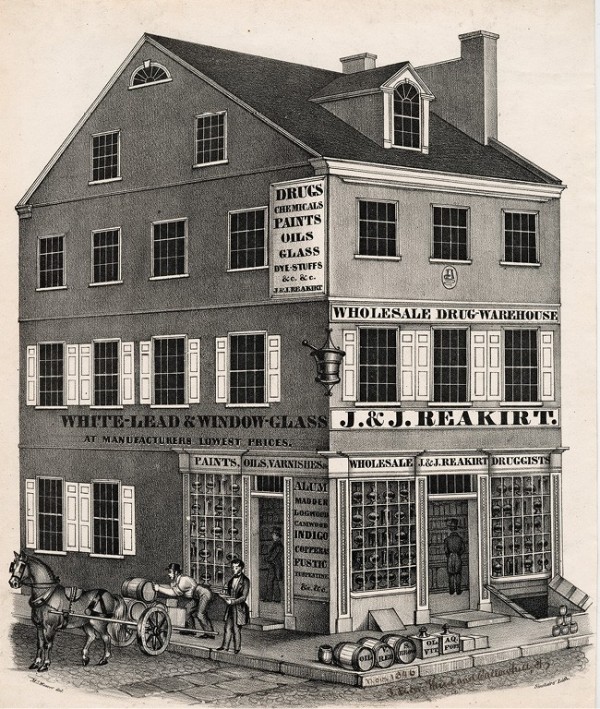

Drug and paint store, J. & J. Reakirt, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1844. Lithograph drawn by Mathias S. Weaver, printed by Thomas Sinclair. H. 16", W. 13". (Courtesy, The Library Company of Philadelphia.) The building exhibits several types of signs: informational boards fixedflat against the external structure, information painted directly on an exterior surface, and a three-dimensional mortar and pestle suspended at the second-story level at a corner of the building.

Books of gold leaf, probably England, 1800–1830. Gold leaf interfaced with laid paper. H. 3 9/16", W. 3 13/16" (closed booklet). (Courtesy, Monmouth County Historical Association, Freehold, New Jersey; photo, Winterthur Museum.)

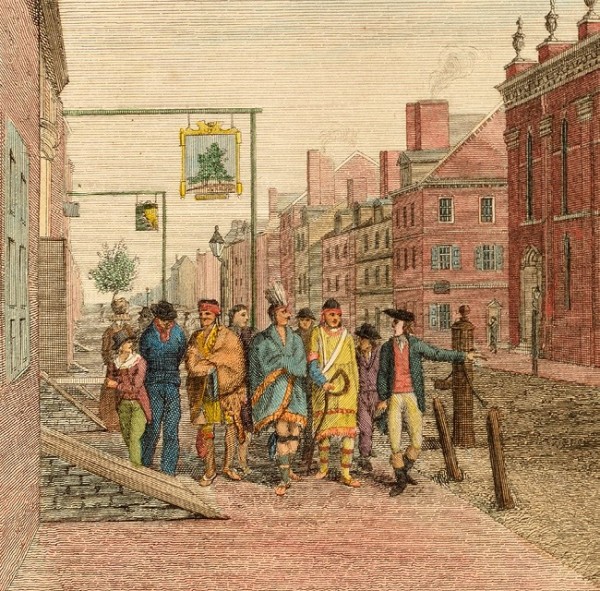

Detail of a delegation of Native Americans to Philadelphia, New Lutheran Church, in Fourth Street Philadelphia, drawn, engraved, and colored by William Russell Birch (1755–1844) and Thomas Birch (1779–1851), published in The City of Philadelphia . . . as It Appeared in the Year 1800 [hereafter Birch’s Views of Philadelphia] (Philadelphia: W. Birch and Son, 1800), plate 6. (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Printed Book and Periodical Collection.) The scene describes a method of hanging shop signs above the walkways of the city. The male figure with an outstretched arm at the right front is said to be Frederick Augustus Muhlenberg, speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives.

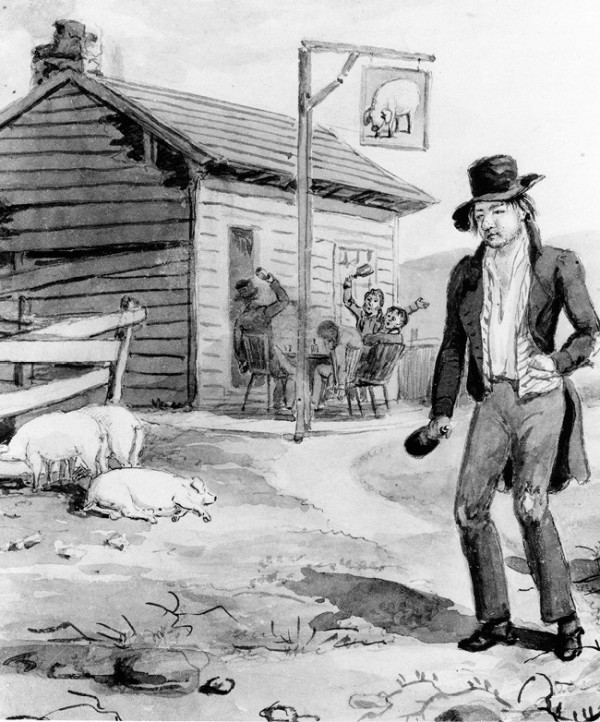

Detail of Virtue and Vice, Sobriety and Drunkenness, Thomas Birch, Philadelphia, ca. 1830. Ink and watercolor on paper. H. 10 1/16", W. 14 7/16". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum,

acc. 67.0131.)

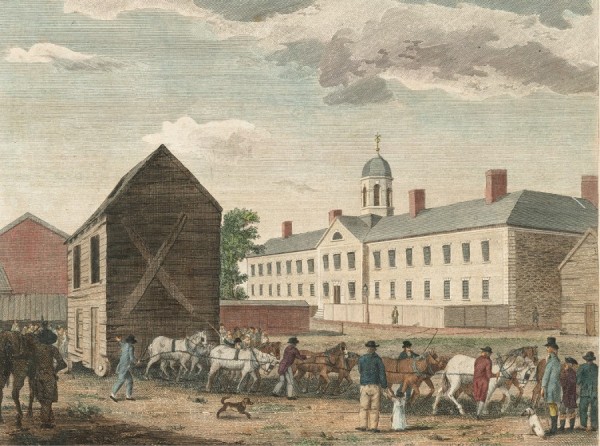

Moving a building in Philadelphia, Goal, in Walnut Street Philadelphia, drawn, engraved, and colored by William Russell Birch and Thomas Birch, published in Birch’s Views of Philadelphia, plate 24. (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Printed Book and Periodical Collection.)

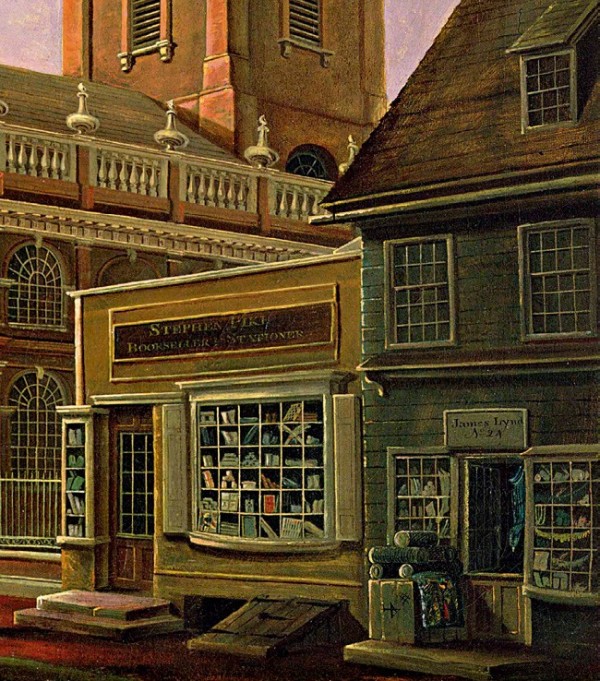

Detail of shop facades adjacent to Christ Church, Philadelphia, from Christ Church, 1811, by William Strickland (1787–1854), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1811. Oil on canvas. Overall H. 48", W. 52". (Courtesy, Historical Society of Pennsylvania Collection, Bridgeman Images.) The shop facades detail a show box next to the shop door at the left and interior display shelves at transom levels in the bow window and the windows of the adjacent building at the right.

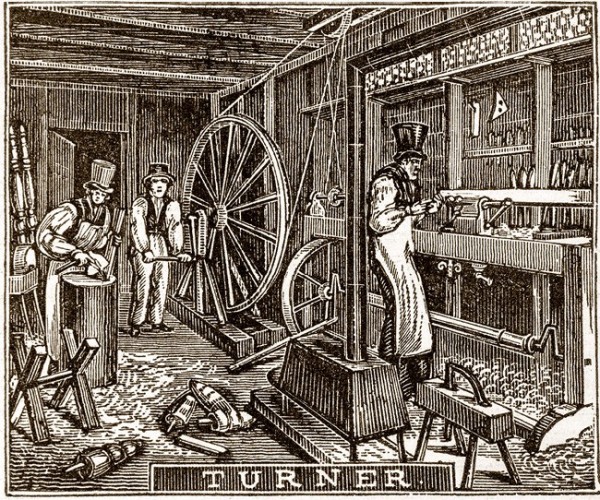

Shop of the Turner, in Edward Hazen, The Panorama of Professions and Trades (Philadelphia: U. Hunt, 1839), p. 219. (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Printed Book and Periodical Collection.)

Shop of the Hatter, in Edward Hazen, The Panorama of Professions and Trades (Philadelphia: U. Hunt, 1839), p. 52. (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Printed Book and Periodical Collection.)

Shop of the Milliner, in Edward Hazen, The Panorama of Professions and Trades (Philadelphia: U. Hunt, 1839), p. 61. (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Printed Book and Periodical Collection.)

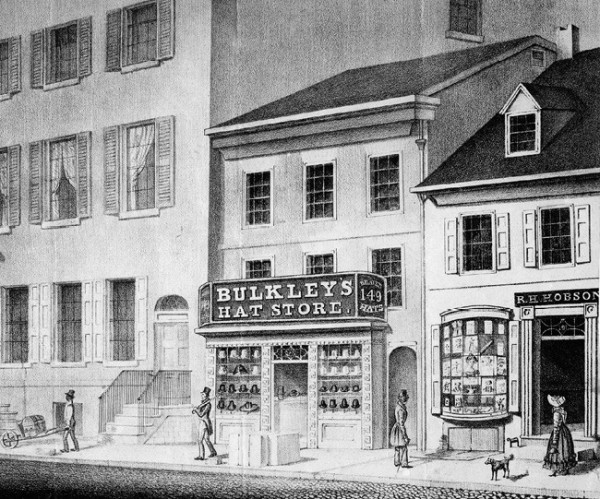

Detail of the Hat Store of C. and J. H. Bulkley, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1833. Lithograph printed by Childs and Inman. H. 7 1/2", W. 10 1/2". (Courtesy, The Library Company of Philadelphia.) The right-side return of the sign reads “BEAVER HATS.”

The Shoemakers, New York, ca. 1855. Chromolithograph printed by E. B. and E. C. Kellogg. H. 8 1/2", W. 12 1/2". (Courtesy, Connecticut Historical Society, acc. 1982.7.8.)

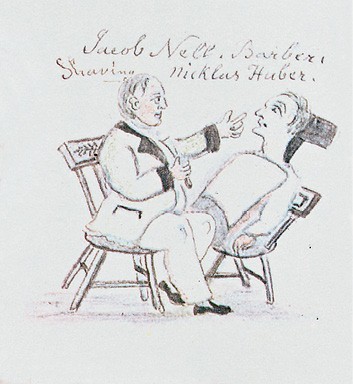

Lewis Miller (1796–1882), Jacob Nell, Barber, Shaving Nicklas Huber, York, Pennsylvania, ca. 1815–1825. Small ink and watercolor drawing and text on paper. (Courtesy, York County History Center, York, Pa.)

Dental trade sign of large tooth, date unknown. Carved and painted wood. H. 23 3/4", W. 12 1/2", D. 13 1/2". (Courtesy, Collection of Shelburne Museum, gift of Julius Jarvis, acc. 1962-181.)

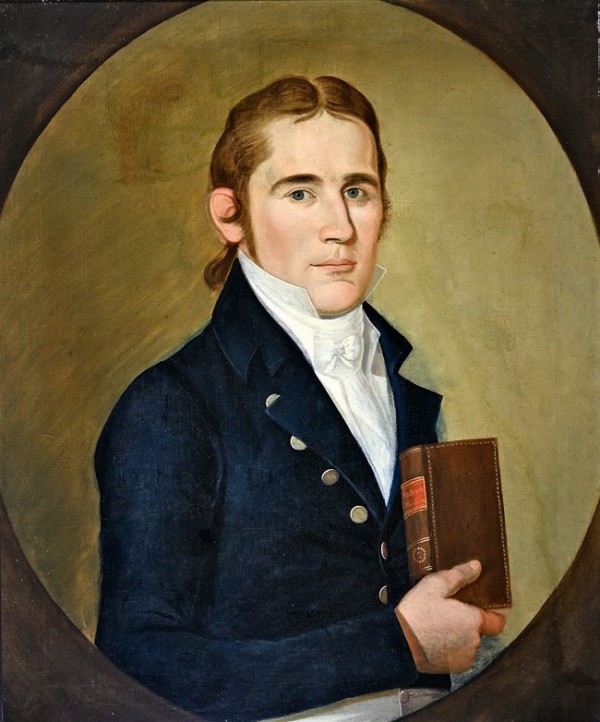

William Jennys (1774–1858), Portrait of Dr. John Brickett [1774–1848], Newburyport, Massachusetts, ca. 1805–1807. Oil on canvas. H. 29 1/2", W. 25". (Courtesy, Collections of the Museum of Old Newbury.) Dr. Brickett also was an apothecary and is portrayed holding a leather-bound volume of Materia Medica.

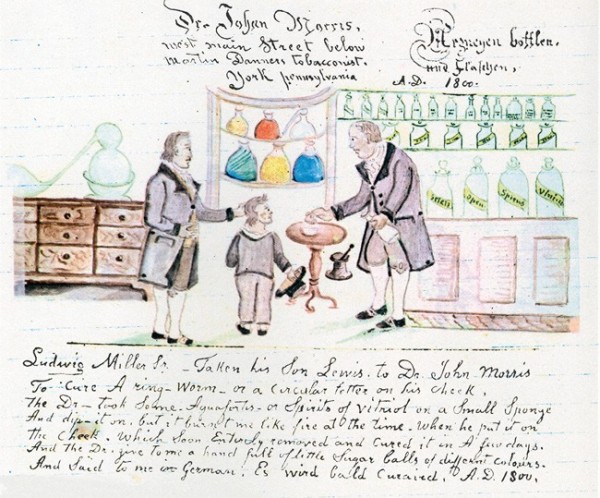

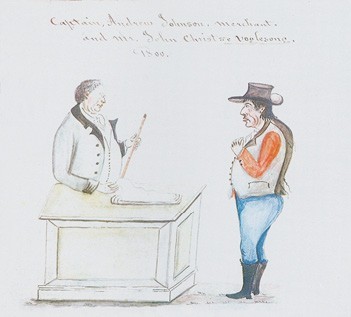

Lewis Miller, Office of Dr. Johan [John] Morris, York, Pennsylvania, 1800. Ink and watercolor drawing and text on paper. (Courtesy, York County History Center, York, Pa.) Pictured are Dr. Morris, Lewis Miller Sr., and his young son Lewis, later the chronicler of York.

Lewis Miller, Store of Captain Andrew Johnson, Merchant, York, Pennsylvania, 1800. Ink and watercolor drawing and text on paper. (Courtesy, York County History Center, York, Pa.)

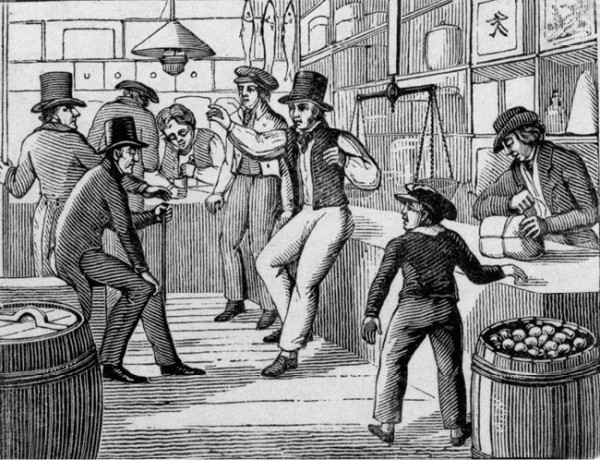

Alexander Anderson (1775–1870), [A Rural Grocery Store], northeastern United States, ca. 1825–1850. Wood engraving. (Courtesy, The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints, and Photographs: Print Collection, “Scenes of daily life in nineteenth-century America,” The New York Public Library Digital Collections, 1794–1870.)

Shop of the Tailor, in Edward Hazen, The Panorama of Professions and Trades (Philadelphia: U. Hunt, 1839), p. 59. (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Printed Book and Periodical Collection.) The owner of the shop or a clerk is using a desk at the extreme left.

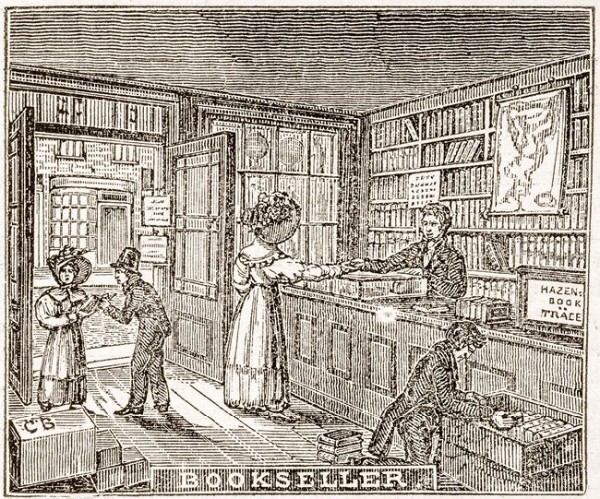

Shop of the Bookseller, in Edward Hazen, The Panorama of Professions and Trades (Philadelphia: U. Hunt, 1839), p. 195. (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Printed Book and Periodical Collection.)

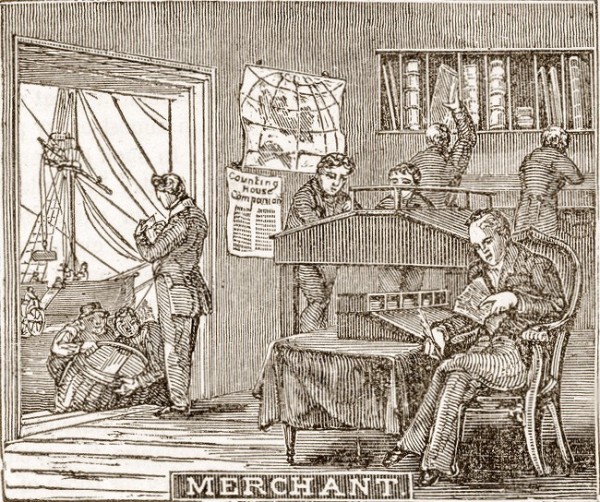

Counting House of the Merchant, in Edward Hazen, The Panorama of Professions and Trades (Philadelphia: U. Hunt, 1839), p. 109. (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Printed Book and Periodical Collection.) The double-sided slant-top desk on tall legs was of a size to accommodate up to four clerks. A small portable desk with slanted writing surface and pigeonholes on the table below was available for additional use. The large case mounted on the wall held ledgers and other account books for easy reference at a counter along the wall.

Horace Bundy (1814–1883), Vermont Lawyer, Manchester, Vermont, 1841. Oil on canvas. H. 44", W. 35 1/2". (Courtesy, National Gallery of Art, acc. 1953.5.4.) The anonymous lawyer’s law books are handy in the bookcase behind him. His writing equipment is at hand: a sharpened quill pen, an inkpot with an additional quill pen, a tall cup-shaped sander containing blotting sand to dry his writing, a small pot containing red sealing wax, and a personal seal with a bulbous handle, the seal at the opposite end containing the lawyer’s initials or a device.

Detail of A Merchant’s Counting House, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1790–1800. Engraved by Alexander Lawson (1773–1846), published by T. Dobson, PR 031. (Courtesy, Bella C. Landauer Collection of Business and Advertising Ephemera, New-York Historical Society, 98124d.) A desk with a double-sided slant top accommodates four clerks within a gated enclosure. Small writing tables are attached to the gated wall, and two large cases on the back wall hold account books. [New-York Historical Society is now known as New York Historical.]

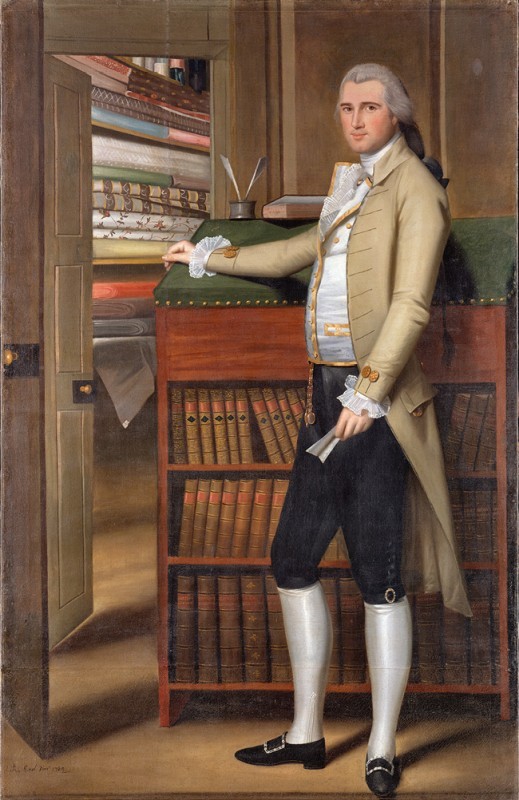

Ralph Earl (1751–1801), Portrait of Elijah Boardman (1760–1846), New Milford, Connecticut, 1789. Oil on canvas. H. 83", W. 51". (Copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, bequest of Susan W. Tyler, 1979, acc. 1979.395; Art Resource, New York.) Boardman was a dry goods merchant in Connecticut. Green baize covers the slanted writing surface of his tall bookcase-desk.

Bank of Pennsylvania, South Second Street, Philadelphia, drawn, engraved, and colored by William Russell Birch and Thomas Birch, published in Birch’s Views of Philadelphia, plate 27. (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Printed Book and Periodical Collection.) The bank was designed by Benjamin Henry Latrobe (1764–1820) in the new Greek Revival style and built between 1798 and 1801. The building to the left with the front awning is City Tavern which, like the Tontine Coffee House in New York, served as a merchant’s exchange.

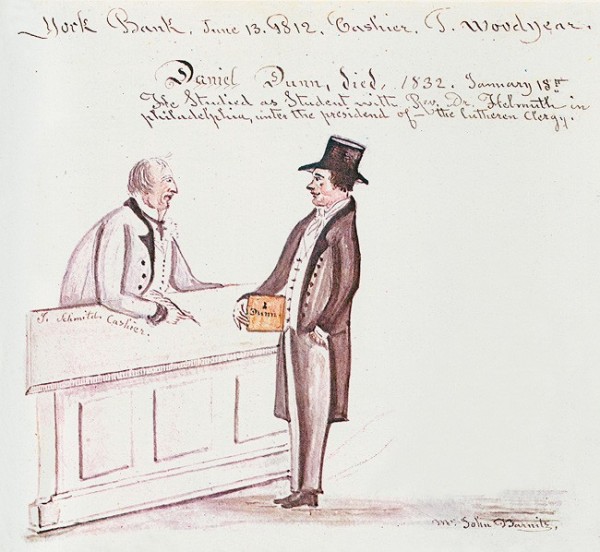

Lewis Miller, Interior of York Bank, York, Pennsylvania, 1812. Ink and watercolor drawing and text on paper. (Courtesy, York County History Center, York, Pa.) Pictured are John Schmitd [sic], cashier, and the Reverend Daniel Dunn, patron.

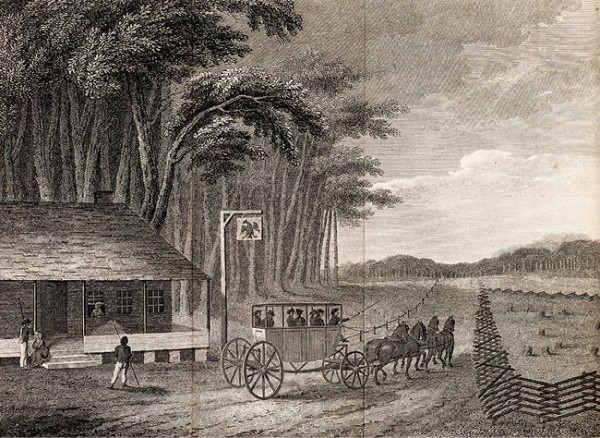

American Stage Waggon, drawn by Isaac Weld, engraved by James Storer, published by I. Stockdale, London, 1798. Illustrated in Isaac Weld, Travels through the States of North America and the Provinces of Upper Canada and Lower Canada . . . 1795, 1796, and 1797, 2 vols. (London: John Stockdale, 1800), 1: frontispiece. (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Printed Book and Periodical Collection.)

Francis Guy (1760–1820), The Tontine Coffee House, New York, New York, ca. 1797. Oil on linen. H. 43", W. 65". (Purchase, the Louis Durr Fund, New-York Historical Society, acc. 1907.32.) The Coffee House was located at the intersection of Wall and Water Streets adjacent to the East River.

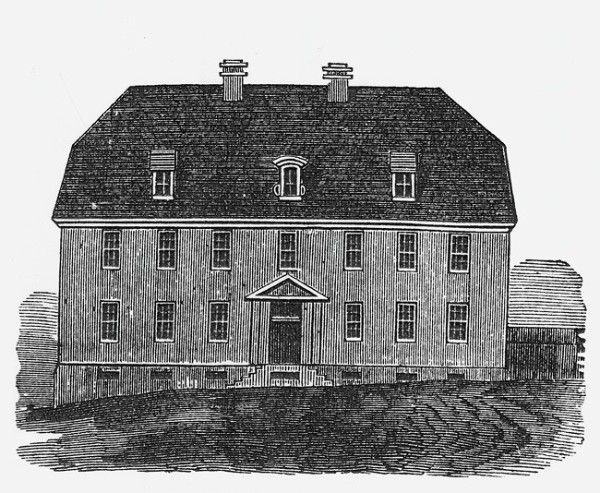

The Sun Inn, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, in William C. Reichel, The Old Sun Inn at Bethlehem, Pa., 1758 (Doylestown, Pa.: W. W. H. Davis, 1876), frontispiece. (Courtesy, Moravian Archives, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania; photo, Winterthur Museum.)

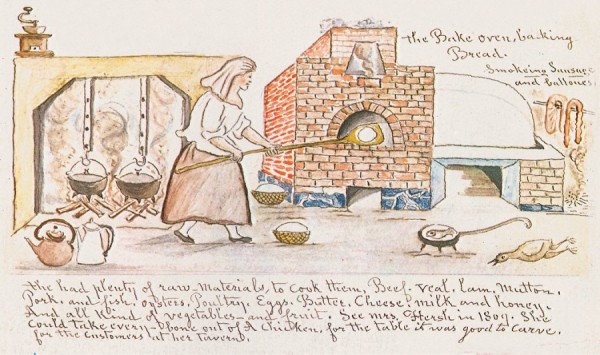

Lewis Miller, Mrs. Hersh’s Tavern, York, Pennsylvania, 1809. Ink and watercolor drawing and text on paper. (Courtesy, York County History Center, York, Pa.) Pictured is a kitchen in a hostelry of German-American background. Food is being prepared in large kettles, long-handled frying skillets, and a bake oven, where the cook-proprietor is using a long-handled wooden peel to insert a loaf of bread for baking after the dough has risen in its cloth-covered basket like those in the middle ground.

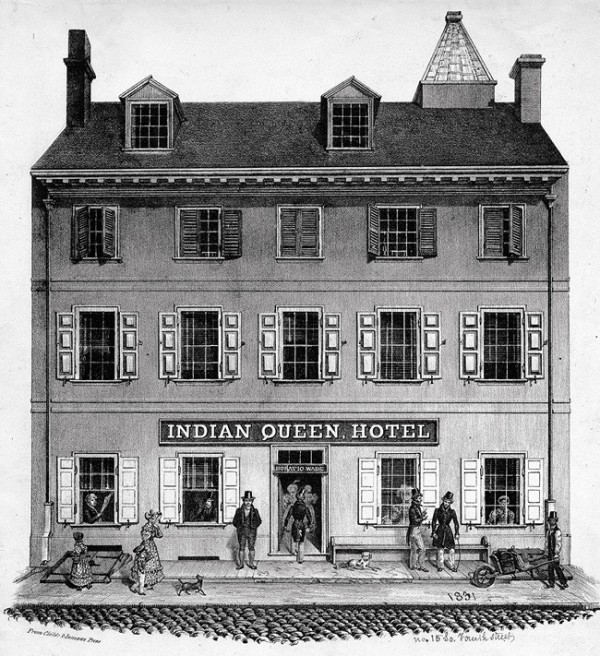

Indian Queen Hotel, Philadelphia, ca. 1831. Lithograph printed by Childs and Inman. H. 12 3/8", W. 11 1/2". (Courtesy, The Library Company of Philadelphia.) Several decades after the visit of Francisco de Miranda to Philadelphia, the Indian Queen Inn became a hotel at the same location, Fourth and Chestnut Streets.

Richard Caton Woodville (1825–1856), Politics in an Oyster House, painted in Düsseldorf for a Baltimore patron, 1848. Oil on canvas. H. 16", W. 13". (Courtesy, The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore.) The setting here closely matches the description of the three-sided booths in the Golden Tun Tavern, Philadelphia, each booth also furnished with two benches and a table and a curtain on a rod at the front that could be drawn for privacy. The lighting fixture is an intrusion of the later period of the canvas.

South View of Trenton, N.J., in John Warner Barber and Henry Howe, Historical Collections of the State of New Jersey (Newark, N.J.: Benjamin Olds, 1844), facing p. 280. (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Printed Book and Periodical Collection.) The two rafts of timber manned by helmsmen on the Delaware River probably are destined for a Philadelphia market.

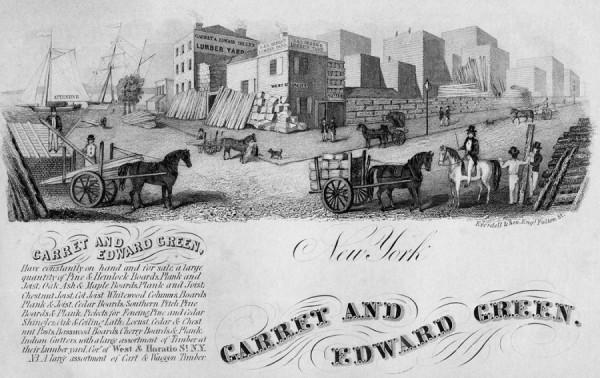

Handbill, Garrett and Edward Green, New York, New York, ca. 1845. Engraved by Everdell and Son. H. 5 1/4", W. 8 3/8". The mammoth size of this facility speaks to the rapid expansion of the city before the mid-nineteenth century.

Alexander Anderson (1775–1870), [A Rural Gristmill], northeastern United States, ca. 1825–1850. Wood engraving. (Courtesy, The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints, and Photographs: Print Collection, “Scenes of daily life in nineteenth-century America,” The New York Public Library Digital Collections, 1794–1870.) The power source for the gristmill is just visible behind the building: a large vertical overshot waterwheel placed in motion by water carried to it in an elevated millrace from the water source.

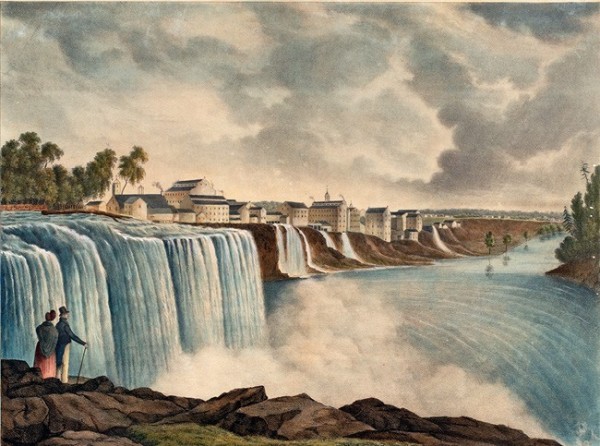

The Upper Falls of the Genesee River at Rochester, N. Y., from the East Bank Looking N.W., Rochester, New York, 1835. Drawn by J. Young, lithographed by J. H. Bufford, published by C. and M. Morse, PR 020. (Courtesy, Collection of Geographic Images, New-York Historical Society, 98180d.) From a small village established at the start of the nineteenth century, Rochester increased rapidly in area and population after 1825 following the opening of the Erie Canal. Wheat, already being grown in the Genesee Valley, quickly became a leading crop when the power of the falls of the Genesee River was harnessed. That power supported the vastflour milling complex shown here, among other businesses. [New-York Historical Society is now known as New York Historical.]

Bass Otis (1784–1861), Brandywine Mills, Wilmington, Delaware, ca. 1840. Oil on canvas. H. 31 1/4", W. 40 3/8" (framed). (Courtesy, Delaware Historical Society, gift of H. Fletcher Brown, 1941.051.)

William Moore Davis (1829–1920), Cider-Making on Long Island, ca. 1865–1875. Oil on canvas. H. 19 3/4", W. 29 3/4". (Courtesy, Fennimore Art Museum, Cooperstown, New York, gift of Stephen C. Clark, acc. 368.1955; photo, Richard Walker.)

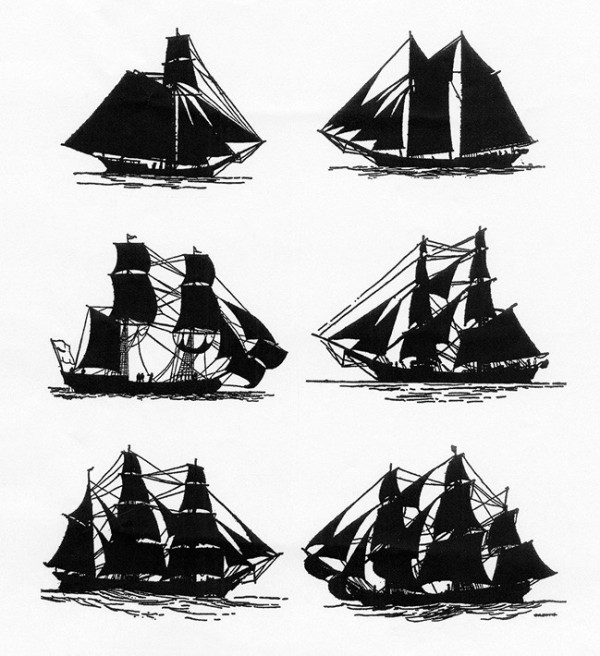

Principal types of American sailing vessels, 1760–1840. Composite from Charles G. Davis, Shipping and Craft in Silhouette (Salem, Mass.: Marine Research Society, 1929), figs. 8, 17, 23, 28, 51. (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum.) The distinctive shape, number, and arrangement of sails and masts differentiate types of vessels without reference to the hull.

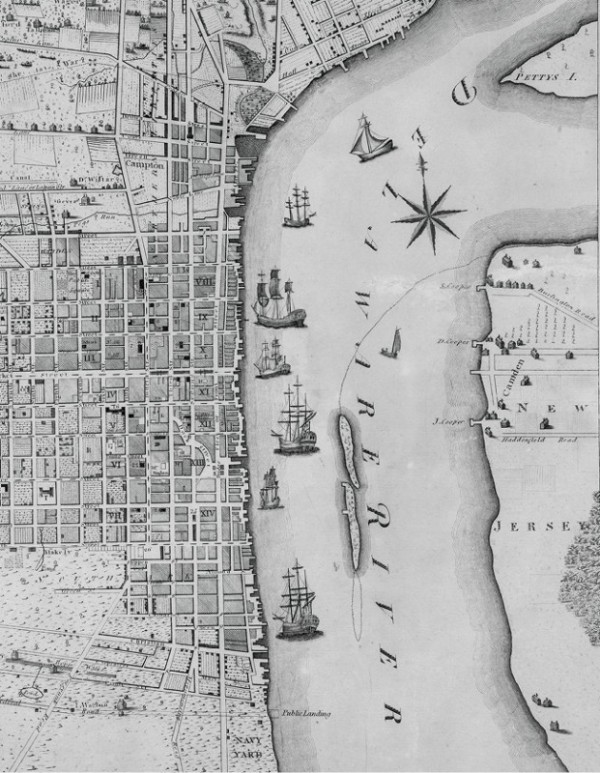

Detail of a Plan of the City of Philadelphia and Its Environs, Pierre Charles Varlé, cartographer, Robert Scot, engraver, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1802. Line etching on laid paper (state two). Overall H. 20 1/2", W. 27". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, acc. 1960.0358.001 A.) The city’s many shipping wharves along the Delaware River, including parts of the Northern Liberties and Southwark, speak to the flourishing state of Philadelphia when it served as the national capital from 1790 to 1800.

South St. from Maiden Lane, New York, New York, ca. 1834. Aquatint drawn and etched by William J. Bennett (1787–1844) after the engraver’s painting, published by Henry J. Megarey. (Courtesy, The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints, and Photographs: The I. N. Phelps Stokes Collection of American Historical Prints, The New York Public Library Digital Collections.) The site on South Street is on the East River looking south from Maiden Lane, where two blocks farther along the waterfront the observer could view the Tontine Coffee House a short distance up Wall Street and perceive the full impact of America’s leading business center.

A View of Part of the Town of Boston in New-England and Brittish [sic] Ships of War Landing Their Troops!, Boston, 1770. Line engraving by Paul Revere (1735–1818). H. 8 5/8", W. 15 3/8". (Courtesy, Boston Athenaeum, George Francis Parkman Fund purchase, 1955, acc. 1955.2.) A sizeable row of storehouses stood on Long Wharf from before the Revolution.

Sailmakers, in Jan Joris van der Vliet, [Book of Crafts and Trades] (Holland, 1635; reprinted in Harry Bober, Jan Van Vliet’s Book of Crafts and Trades [Albany, N.Y.: Early American Industries Association, 1981])), pl. 11. (Photo, Winterthur Library.) Although this is an early representation of the craft of sail making, craft procedure was not significantly changed by use of a sailmaker’s bench for seating and easy access to the tools of the trade.

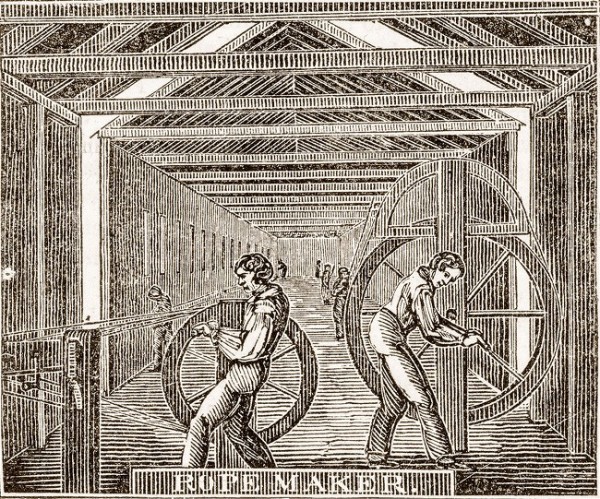

Facility of the Rope Maker, in Edward Hazen, The Panorama of Professions and Trades (Philadelphia: U. Hunt, 1839), p. 56. (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Printed Book and Periodical Collection.)

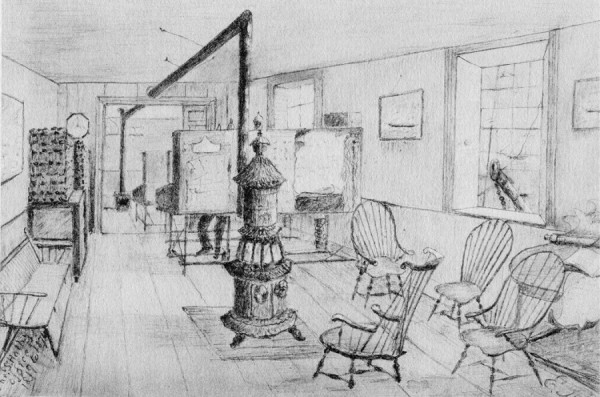

Office of Humphrey Hathaway, at the Head of Rotch’s Wharf, New Bedford, Massachusetts, ca. 1873, depicting a scene of 1819 or later. Pencil sketch on paper by Edward S. Russell. From Horatio Hathaway, A New Bedford Merchant (Boston: Merrymount Press, 1930). (Courtesy, New Bedford Whaling Museum, Estate of Thomas S. Hathaway.) This counting room adjacent to the wharves probably was typical of a moderate to large coastal facility of the early nineteenth century. The two long desks with their bookcases and slanted writing surfaces could accommodate two or three clerks each. By the late eighteenth century iron stoves had replaced the hearth as the heat source. Here, the forward area of the room with its Windsor seating, maps, and a telescope provided a convenient place for sea captains, clients, and others to meet and acquire news about markets, shipping conditions, and related subjects.

Joseph Howard (1780–1857), detail of bow of the frigate U.S.S. Essex, Salem, Massachusetts, after 1799. Gouache and watercolor on paper. Overall H. 19 3/4", W. 27 3/4". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of John P. Howard, 1888, acc. M167.) Displayed in this detail are several carved and painted features that customarily were part of the overall design of a large vessel: a figurehead, here in the unusual form of a Native American, and whose left leg is bent at the knee in a “walking attitude”; a trail board, one of a pair, mounted on the sides of a vessel below the figurehead and extending the full or partial length of the vessel; a catface, a whimsical depiction of the facial features of a wild cat on either blunt end of a cathead.

John H. Bellamy (1836–1914), carved lion’s head made as a catface for one end of a cathead, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1859. Pine. H. 13", W. 14". (Courtesy, Old Sturbridge Village.) A note pasted on the back of the image reads: “This piece was carved by John H. Bellamy, at 77 Daniel Street, January 1859.”

Samuel King (1749–1820), Little Navigator, Newport, Rhode Island, ca. 1810. Carved and polychromed wood shop sign. H. 24". The sign hung over the shop door of James Fales, nautical instrument maker of Newport and later over the shop of James Fales Jr. of New Bedford, Massachusetts, ca. 1830–1880. (Courtesy, New Bedford Whaling Museum.)

Benjamin Henry Latrobe (1764–1820), A Conversation at Sea, Virginia or Philadelphia, March 10, 1797. Watercolor on paper. (Courtesy, Maryland Center for History and Culture.) When two vessels met at sea, the use of speaking trumpets permitted the exchange of news and information.

Ship Montesquieu off the Harbor of Macao, anonymous, Philadelphia, 1812. Oil on canvas mounted on wood. H. 20 3/4", W. 27". (Courtesy, Girard College History Collections, Philadelphia, Pa., acc. 0063.) This ship was one of a variety of vessels owned by Stephen Girard (1755–1831); the figurehead of the ship was carved by William Rush (1756–1833).

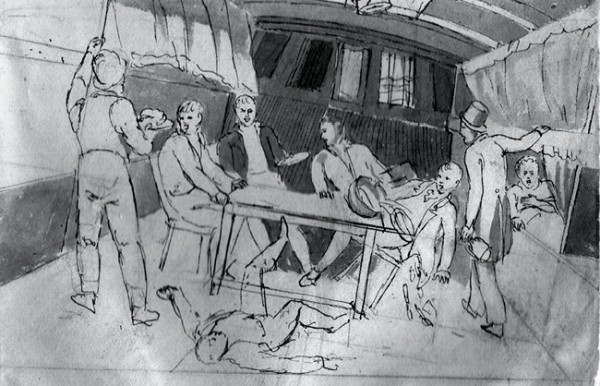

John Lewis Krimmel (1786–1821), Cabin of a Sailing Vessel, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1812–1813. Ink, ink wash, and pencil on paper. H. 4 3/8", W. 6 1/4". From Krimmel, Sketchbook 2, 1812–1813, p. 11. (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera.) The water through which the vessel is sailing has become rough, and it is playing havoc with activity in the cabin.

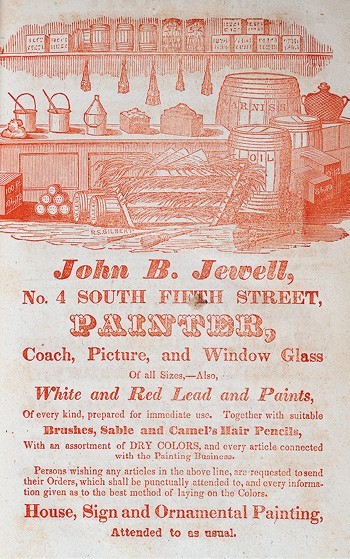

John B. Jewel, advertisement. From Desilver’s Philadelphia Directory and Stranger’s Guide for 1837 (Philadelphia: Robert Desilver, 1837), n.p. (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Printed Book and Periodical Collection.)

John Lewis Krimmel, Steamboat Travel on the Hudson River, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1812–13. Watercolor and gouache on white wove paper. H. 10", W. 14 1/2". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1942, acc. 42.95.7; Art Resource, New York.) While traveling in America from 1811 to 1813, Paul Petrovich Svinin (1787/88–1839) assembled a portfolio of 52 watercolor views of North America, some purchased from Krimmel, including this view of an early steamboat. Carried back to Russia, the portfolio eventually came into the possession of an American following the tumult of the Russian Revolution. By 1930 the portfolio was in the possession of R. T. Haines Halsey, from whom in time it was transferred to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where Halsey was founder of the American Wing. See also Anneliese Harding, John Lewis Krimmel: Genre Artist of the Early Republic (Winterthur, Del.: Winterthur Publications, 1994), pp. 238–49.

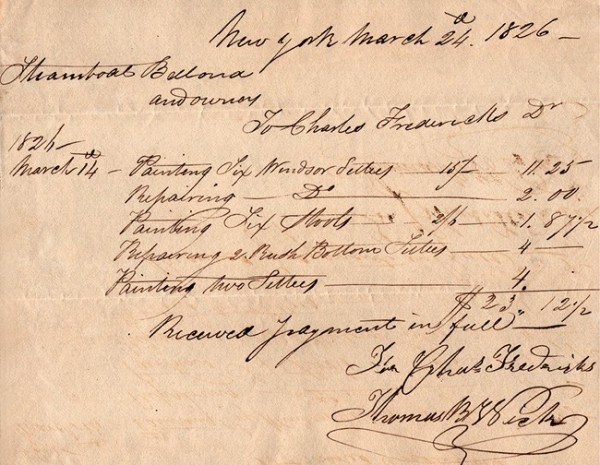

Charles Fredericks, bill to steamboat Bellona, New York, March 14, 1826. (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera.)

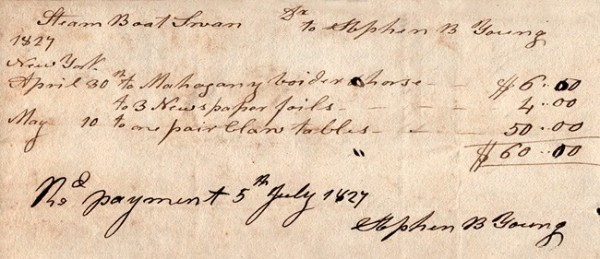

Stephen B. Young, bill to steamboat Swan, New York, April 30–May 10, 1827. (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera.)

THIS STUDY IS BASED ON a large body of written material providing insight into the myriad jobs performed by cabinetmakers, carpenters, painters, and allied artisans to meet the needs of fellow craftsmen, retail businesses, the professions, merchants, and the maritime community during a period of growth, expansion, and technological change in America. Location frequently played a part in a woodworker’s success, whether in a rural or an urban environment. The rural craftsman frequently possessed a homestead and farmed his land to help support his family. His land might supply timber used in his trade or as barter in supplement to foodstuffs and other commodities. Frequently his customer base was limited, however, and his distribution area relatively modest. Handyman skills could broaden his income. The urban craftsman had other opportunities and faced somewhat different circumstances. His customer pool often was larger, and in a coastal area it often extended to the maritime community. He frequently lived and worked in rented space without sufficient ground to make a garden, acquiring foodstuffs to feed his family by purchase, sometimes by barter. To pursue his trade, he purchased wood from a local board yard or independent supplier and other materials from specialty shops. Competition frequently was keen, and it increased markedly during the early nineteenth century.

Identifying the Business Site

Integral to establishing a new business was the need to acquaint potential customers with its location. This could be achieved by word of mouth in a small community. In a large urban area, however, even a published notice might not suffice. Jacques-Pierre Brissot de Warville described a common problem when visiting Philadelphia in 1788: “the streets are not inscribed and the doors not numbered.” A business newcomer of modest means might identify his location relative to an established business, public building, or the residence of a prominent individual. Many owners identified their place of business with a sign. Early signs frequently were suspended from the facade of the business structure; later signs usually were installedflat against the front of the building.[1]

The common material of the sign was a wooden board, frequently fitted with a plain or decorative framework. A white pine board was the common choice in New England; yellow (tulip) poplar was more prevalent in the Middle Atlantic region and parts of the South. Secondary woods in the framing might include ash, oak, chestnut, or maple. Signs of the late colonial and early federal periods often were of vertical rectangular form, many with a pediment at the top and a shaped skirt at the bottom (fig. 1). Somewhat less common was the horizontal rectangular sign; oval or shield-shape signs were rarer choices. In 1812 William Chappel of Danbury, Connecticut, made special note when he produced an “Ovil sign” for a customer. Relatively uncommon until the early nineteenth century was “painting a sign on tin,” a job recorded in 1816 by Allen Holcomb of New Lisbon, New York, for Dr. Walter Wing. By the early nineteenth century the broad distribution of large sheets of tinned iron made this option possible.[2]

Business signs of the late colonial and early federal periods frequently were pictorial. Aside from the occasional name or business of the proprietor, lettering was minimal, since literacy was not universal. The pictorial subject of the sign usually identified the nature of the business. For instance, in 1751 at Philadelphia the sign of the “Tent” identified the shop of Thomas Lawrence, an upholsterer on Second Street, who supplied both household furnishings and military equipment. Ironmonger Peter T. Curtenius of New York chose a “Golden Anvil and Hammer”; elsewhere in the city baker William Mucklevain displayed a sign depicting “Three Biskets.” An unusual request by Truman and Company, apothecaries of Providence, Rhode Island, was recorded by William Allen, a local painter and gilder. After “Painting a Sign board” in May 1785, Allen also painted “an Owl to stand on ditto.” The complete job cost the proprietors 24s. ($4.00 in later decimal currency). In the following decade Boston painters Daniel Rea Jr. and George Davidson had calls to paint signs identifying a variety of trades (fig. 2). Simon Hall visited Rea in July 1791 for a job described as “painting a Beauro . . . mehogony and Writ’g S. Hall, Cabinet maker on the Sides,” indicating the sign was a board for hanging, the printed letters and image visible from either side, a common practice. William Williams engaged Davidson several years later to paint his “Sine hat Boxes and a Wooden Hatt.” The wooden hat appears to have been three-dimensional and was either fixed to the top of the signboard or suspended from the bottom. The cost at £5.2.0 ($17.00 in decimal currency) was relatively substantial. Windsor chair maker Reuben Sanborn also engaged Davidson to prepare his sign featuring a “gold chair.” The cost at £5.8.0 ($18.00 in decimal currency) identified work executed in gold leaf, probably on two sides of a suspended board rather than as a three‑dimensional object. Sanborn’s business site at this date (1799) was Doane’s Wharf, a location where he could easily participate in the export trade in vernacular chairs.[3]

Pictorial symbols painted on hanging boards and the occasional suspended three-dimensional object continued in use for business signs into the early nineteenth century. Thomas Boynton of Windsor, Vermont, painted and gilded a sign for silversmiths Johonnot and Smith in September 1815 and then made a “label” lettered “Walk In.” The partners called on Boynton again in December, paying $6.00 for a job of “painting and gilding a watch for a Sign” (fig. 3). A popular insignia of the barber’s trade was the white-painted pole spirally ornamented with a red band, the red color describing the earlier historical role of barbers as surgeons and bloodletters. Samuel and Daniel Proud of Providence, Rhode Island, recorded “making a Barber Pole” for Phillip Lewis, and a pole valued at $1.50 was in the 1832 estate of William Taylor, a barber of Boston. Pifer Washington Case of Johnstown, New York, had occasion to paint a barber pole for a customer several years later. Whereas cylindrical barber poles were shaped on a turning lathe, George Ritter, a cabinetmaker of Philadelphia, used hewing and shaping tools to fashion a large boot in 1835 for Levick and Jenkins, shoe dealers. The boot, made of yellow poplar, is described as “2 feet 3 [inches] long, the foot 18 inches long . . . 8 in[ches] thick.” The job would have required one or two sizable pieces of timber. Given its dimensions, the boot probably functioned as an outdoor sign rather than as an indoor feature. It may have hung suspended from the second story or been fixed on a ledge above the entrance. By this dateflat, lettered signs fastened to the business facade had become common advertising pieces, and street names and numbered buildings were common in communities of reasonable size.[4]

Following the War of 1812 use of signage fixed to a building facade, and sometimes along a side, increased measurably as trade began to grow andflourish (fig. 4). Nevertheless, the hanging sign still remained a choice in some locations for several decades. As late as 1820, when William Wood Thackara visited the small community of Tisbury, Massachusetts, on Martha’s Vineyard, he remarked that the “sign boards over the shop doors hang out as ostentatiously as though the place contained many thousand inhabitants.”[5]

Most fixed signs were wider than their depth, the size determined by the message. A sign made by Timothy Gladding for Peter Gansevoort in 1831 at Albany, New York, for a charge of $1.25 was of modest length and contained the client’s name and occupation: “Examiner in Chancery.” Requiring more extensive work was a sign constructed at Philadelphia in 1828 by George Ritter for John Jordan, a grocer (see fig. 2). The job, which cost $4.00, was described as “a sign Board 8 feet 3 inches Long [wide] by 18 inches wide [tall] with Walnut Doughftails in Back side & two mouldings on the edge.” The dovetails were dovetail keys inserted across the narrow dimension of the wood in shallow slots to strengthen the board and control warping. The moldings on the edges addressed the same issues besides adding a decorative element. Ritter later made a small sign with “moulded edges” for Dr. George F. Alberti. The “4 rose blocks for sine board” turned in the shop of Thomas J. Moyers and Fleming K. Rich at Wythe Court House, Virginia, in January 1838 at a cost of fifty cents were either for the four corners of new work or to refurbish an older sign. The actual surface pattern of the “rose” is unknown, although the modest cost and production method suggest a simple design, likely of concentric circles rather than carved petals.[6]

Once a proper board for a sign was in hand, decoration began with a “priming” coat of paint to cover any irregularities in the wood, followed by one or two coats of the desired ground color. A simple painted border could serve to frame the lettering and any images on the signboard. Although most grounds were plain, there were ornamental options. Grounds could be enhanced with smalt, a pigment made principally of finely pulverized cobalt blue glass strewed “on any ground of oil-paint while wet, where it makes a bright warm blue shining surface.” George Rutter, a painter of Philadelphia, advertised in 1791 “Signs done with the best Strewing Smaltz.” Frédéric Louis Moreau de Saint-Méry, a temporary resident of Philadelphia in the mid-1790s, commented on the city’s artisans “who make a specialty of painting remarkably beautiful signboards with backgrounds of different colors, speckled with gold or silver.” While in Philadelphia, Moreau de St. Méry opened a printing, stationery, and bookshop at the corner of First and Walnut Streets and commissioned a signboard in English and French.[7]

Most signs were printed with serif letters (see figs. 1, 2, and 4); a few employed cursive lettering that resembled handwriting. Lettering was executed in plain paint contrasting in color with the ground, or in gilt. The charge for the work frequently was calculated by the number of letters. In two separate transactions, William Gray of Salem, Massachusetts, charged 2d. per painted letter and 9d. per gold letter, although prices for both types of work were variable, based on letter size. “Shading,” recorded in Vermont by Thomas Boynton, made letters bolder by creating a sense of depth achieved by bordering parts of the letters with a contrasting color (see fig. 36). On occasion a finished sign was priced by the foot, as occurred in 1837 when William Wilson of Lowell, Massachusetts, charged 3s. per foot for a twenty-four-foot sign. John Doggett of Roxbury, Massachusetts, upon completing a job of gilding a sign, appears to have priced his work by the number of gold leaves or books that were used. His bill of $5.50 to Captain Jesse Doggett in 1808 for gilding his tavern sign, the “Ball and Pin” (skittle), was based on the five and one half books of gold leaf the job required (fig. 5). Doggett’s tavern may have been accompanied by sufficient exterior grounds to accommodate the game of ninepins in fair weather.[8]

Little is written about the application of a protective varnish coat to a sign once painting and gilding (if present) were complete. Sparse evidence still remains on some preserved signs, although the practice probably was more common than indicated. The cost was minimal, and it probably was included as part of the cost of overall decorative work. Windsor and fancy seating, except perhaps for the cheapest production, was routinely finished with a coat of “chairmaker’s varnish,” whether plain painted in the eighteenth century or decorated in the early nineteenth century. Varnish protected the chair’s finished surfaces from the wear of use just as a varnish coat could protect an outdoor sign from the abuse of weather. Luke Houghton, a cabinetmaker and chair maker of Barre, Massachusetts, recorded a fifty-cent charge to Kendall and Baker in 1816 for varnishing a sign, probably one already in use and in need of minor refurbishing.[9]

Once a signboard was completed, it required installation. Craft accounts and other records suggest how this was accomplished. Jacob Mordecai, when recalling his youth in pre-revolutionary Philadelphia, described a sign for the fashionable retail shop of George Bartram: “the Golden Fleece, a gilt lamb suspended half way across the pavements in 2d Street near Carter’s Alley.” The support appears to have been a horizontal arm fixed to the building (fig. 6). A similar arrangement was recorded in 1815 by Thomas Boynton at Windsor, Vermont. After supplying Frederick Pettes, innkeeper, with a “Sign Stage House” for $3.00, Boynton added another fifty-cent charge for “painting arm and hanging d[itt]o.” Not identified but part of this work were “the Irons” necessary for hanging the sign. These metal straps with eyelets at the top to engage metal hooks on the arm were fixed to the side edges or the top of the sign (see fig. 1). An alternative method of installation involved a freestanding post with or without an arm at the top (see fig. 7). An early record is Joseph Bolton’s work in 1762 of hanging a sign from a post in front of the shop of Stephen Collins, an up-and-coming storekeeper/merchant in Philadelphia. Later, in 1789, Gershom Jones, a pewterer of Providence, Rhode Island, hired Job Danforth Sr. to make a signpost and install his sign.[10]

Two methods of preparing posts are indicated in records. Paul Jenkins of Kennebunk, Maine, recorded hewing a signpost, whereas Moses Parkhurst of Paxton, Massachusetts, described “turning sign posts.” An indication of the time required to prepare some signposts is noted in the accounts of William Fifield of Lyme, New Hampshire, when in 1821 he recorded “1 Day work on Sign post.” Installation of a long,flat sign to be mountedflush against a building was a different challenge. After William Wilson made a ten-foot sign for customer W. C. Burrows at Lowell, Massachusetts, in 1837, he used a “Crain” to help secure it in place. At this date the crane would have been a human-powered hoisting device. Not all signs were as professional as those described. John Bernard, a Briton traveling in the Carolinas about 1800, commented on the common rural ordinary (tavern): “You might always know an ordinary, on emerging from the woods, by an earthen jug suspended by the handle from a pole . . . or a score of black hogs luxuriating in the sunshine and mud before the door” (fig. 7).[11]

Maintenance at the Business Site

Miscellaneous woodworking and related work at the business site was an ongoing call; many jobs were incidental in nature, while others were more extensive. An infrequent request was for “moving” the shop. Of two recorded late eighteenth-century jobs—one in Hartford, the other in Danbury, Connecticut—one required a full day and the other a half day of the craftsman’s time. The modest costs indicate the moves involved transferring shop contents to other facilities rather than physically moving the structures. If the work had represented physical moves of the shops, the craftsmen involved probably would have provided “roolers [rollers] for mooving bildings,” such as those purchased in 1820 by Zachariah Chafee, a mason of Providence, Rhode Island, from Samuel and Daniel Proud (fig. 8). An extensive job of a diVerent type, completed by Thomas Christy at Boston, Massachusetts, in 1782 for Moses Grant, an upholsterer and shopkeeper, involved “putt’g a new front To the shop he improved belonging to his Father.” Outdoor activity by craftsmen in other locations included work on a shop roof and a job that required “three days a Shingling Store” accompanied by “pa[i]nting Coving.” Constructing new or replacement steps at a business site was a recurring request in all areas, from Gloucester, Massachusetts, to Newport, Rhode Island, to Middletown, New Jersey. Some steps were painted; others, apparently, were left in the wood. Henry Wansey, an English visitor to America during the mid-1790s, commented when visiting Philadelphia: “Almost every house of trade has an assent of steps to enter, and a sloping cellar window or door to receive goods” (see figs. 4 and 9).[12]

Two unusual references of mid-eighteenth-century date posed an initial interpretative challenge. A customer at Reading, Massachusetts, requested Peter Emerson to make “Bords for Shop winders [windows],” the cost amounting to a significant £1.5.0 ($4.17 in later decimal currency). Abraham Dennis of Newport, Rhode Island, engaged Job Townsend Jr. for a similar job: “Fixing a Board on his Shop window.” What was the purpose of the boards? Both references became clearer in the early nineteenth‑century accounts of George Ritter of Philadelphia when Abel Wyman, a shoe dealer, engaged the cabinetmaker for “Making, painting & fixing two show Brackets at front door of Store.” Made of pine, these tall, slim boxlike containers with shelves were used to display merchandise similar to that available in the store. A single show box at the front door of a shop is depicted in figure 9, where it is accompanied by a large bowed shop window, describing in its particular character the purpose of the boards for shop windows. Horizontal shelves for displaying merchandise were fixed to the interior woodwork, each shelf positioned at a transom level of the window. In 1791 when working for the local merchant Charles Shoemaker, Philadelphian David Evans described a similar job as “4 Shelves for Store Windows.” Two shelves for displaying footwear are installed at transom level in a large window viewed from inside a shoemaking shop (see fig. 14).[13]

Aside from carpentry, exterior shop and store work called for painting. A substantial job of “painting Shop twice over” for John Munroe of Barnstable, Massachusetts, at a cost of $7.50, probably engaged the painter Nathaniel Holmes the better part of one week (see fig. 2). The work was accompanied by priming a blind, or outside shutter, and “finding paint.” After “grinding green and puting it on,” Holmes continued by painting the door, shop steps, and pump, probably with the same green. Of particular note because of its rare mention is work undertaken by Thomas Boynton in painting and then “Pencilling Store front” for G. W. and C. F. Merrifield, printers at Windsor, Vermont. The principal tool used for this work was a fine-tipped camel’s-hair brush, called a pencil, with which a skilled painter could create decorative work consisting of thin straight or curved lines to emphasize structural features, such as a doorway or window, or create the illusion of paneled features.[14]

A cheap way of brightening outdoor walls or common structures was by using whitewash, a mixture of lime and water. A better quality of work employed Spanish whiting or oyster-shell white mixed with size and water. Frederick K. Coady, a craftsman of upstate Ogdensburg, New York, recorded at least two instances of whitewashing, one at a customer’s store, the other at a shop. Miscellaneous jobs performed by woodworking craftsmen included a variety of incidental tasks. Job E. Townsend installed a lock on the “Store Door” of Phillip Morss (Morse?) in 1788 at Newport, Rhode Island, and William Wilson supplied “1 Door plate” priced at twenty-five cents some years later for the shop and office of A. W. Moulton at Lowell, Massachusetts. The plate may have resembled those advertised in 1791 at Philadelphia: “Japanned Plates for Window Shutters, Doors, &c. elegantly wrote or printed in Gold Letters.”[15]

Interior work at the business site was as varied as exterior work. Grocer Richard P. Foulke of Philadelphia had substantial “Carpenters work” done at his store at the “Corner of filbert street and 8th” in 1822 by Joseph Dives. Record of an exact business address for a customer, as here, is a rarity in craftsmen’s records. Jobs involving windows and doors actually fall into a category of inside-outside work. Richard Blow, a storekeeper and merchant in Norfolk, Virginia, engaged Hatter and Miller in 1783 for a job at the store that included glazing eighty-five lights (window panes), for which the workmen cut sixty-four new panes of glass and supplied the putty (see fig. 2). Similar jobs elsewhere were more modest by comparison. Pease and Fowler of Middletown, Connecticut, engaged Elizur Barnes to set two squares of glass in the shop door. A rowdy youth led Silas E. Cheney, a cabinetmaker of Litchfield, Connecticut, to charge the father twelve cents for “your boy breaking Glass out [of] Shop.” Owners of facilities other than stores and shops also called on skilled artisans for related work. Proprietors of the Levi Shephard and Sons factory at Northampton, Massachusetts, employed Harris Beckwith in 1805 to make “two Window frames and Sashes for the factory.” Two years earlier Beckwith had worked for Job White making “A Door for your Shop” then “Caseing and hanging the same.”[16]

Structural work within the shop accounted for a variety of other jobs. A customer of Job E. Townsend at Newport, Rhode Island, hired him for “Putting up a Pertiation in the Shop.” Another customer requested that he move a partition to another location in the shop. Both jobs were priced in the general range of three dollars, aside from materials, and likely required several days of the craftsman’s time. During the same period (ca. 1800), Townsend also worked at the shop of Edward Stanhope “Cutting a hole for a Stove Pipe.” The dimensions of this type of job were stated in more detail by Job Danforth Sr. at Providence, Rhode Island, when working at the shop of Robert Adam: “cutting holes in thefloor and Roof . . . for your Stove pipe.” During the late eighteenth century, metal stoves rapidly replaced the hearth as the heat source for craft shops and stores. Metal stoves burned fuel more efficiently, were freestanding, and radiated heat in all directions (fig. 10; also see fig. 47). Another job, described by Horace Beckwith of Northampton, Massachusetts, as “two days Work in your Blacksmith Shop Layingfloor,” cost Charles Chapman twelve shillings. The six-shilling wage per day, as indicated, was a good average pay for a skilled craftsman during much of the period under discussion. When the British currency system was replaced with a decimal system in the 1790s, six shillings were equated with one dollar throughout the United States, except for New York, where the figure frequently was eight shillings New York currency.[17]

Interior painting was a recurring need in many places of business. After the extensive glazing work at Richards Blow’s commercial facility in Virginia, Hatton and Miller followed with “painting ye inside of ye Store.” Successful retailers found that their premises required periodic refurbishing, much as proprietors of well frequented inns and taverns needed to remain alert to the maintenance of their properties. During the early 1840s several facilities in the town of Windsor, Vermont, aflourishing and handsome commercial center on the Connecticut River, benefitted from the services of Thomas Boynton. Innkeeper Samuel Patrick hired him to paint the “south room and dining roomfloor in [the] Tavern.” The $4.50 charge was covered in part by an earlier credit for Patrick who had supplied Boynton with “1 Cord of wood, 1/2 Bass wood” and “a turkey for thanksgiving.” A substantial job took Boynton to the Windsor Tavern Company, where he was engaged in a process he termed “Stamp painting” in the “2d & 3d Entry Halls” and the “Dining room and setting room.” This work was followed by “varnishing [the] 2d Hall” and “Varnishing [the] Dining room and reading roomfloors with 3 gall[on]s [of] varnish.” While on the premises, Boynton also lettered and numbered doors, hung bells, and provided a “Sign Windsor House.” The complete job amounted to $68.68. At Ogdensburg, New York, in 1842 Frederick K. Coady painted thefloor twice at G. N. Seymour’s store. An uncommon call earlier the same year found him papering the shop of S. B. Strickland.[18]

Supplying the Specific Needs of Business

The accounts of foreign visitors to America and commentary by residents attest to the substantial variety of trades practiced in the American colonies prior to the Revolutionary War. Following the conflict, corresponding documents describe the rapid expansion and proliferation of craft shops and large and small businesses in concert with the expansion of mercantile activity, both domestic and foreign. This section will focus on the activities cited most frequently in the material gathered for this study—whether pertaining to trades, shops, stores, professions, merchandising, or commerce—to understand better the woodworker’s critical role in supporting and shaping the business community.

Craft Shops

Hatters

Work for hatters, and to a lesser extent for milliners, was a frequent call at the woodworking shop. George G. Channing of Newport, Rhode Island, grandson of William Ellery, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, recalled the early nineteenth-century years of his youth and noted that beaver hats were costly and worn only by a few gentlemen. Continuing, he identified the felt hat made from less costly fur “stiffened with paste and glue” (later with gum shellac) as the common head wear of men and boys. Wind, dampness, and rain took their toll, and under those conditions, owners were required to “block out” the bodies and rims of their hats or they assumed “the most grotesque and forlorn shapes imaginable.”[19]

In June 1773 Samuel Williams, a Philadelphia “joiner” with a board yard on Fourth Street between Market and Chestnut, advertised “4 inch poplar plank for hatters,” describing the material of hat blocks used locally. Purchased individually or by the dozens from woodworkers everywhere, the cylindrical hat block was an essential commodity. Hatters used them in large numbers: blocks to shape the body of the hat; separate blocks for the dyeing process; other blocks for the finishing process. The more than 200 “Colouring Blocks” purchased by hatter William Washburn of Kingston, Massachusetts, between 1824 and 1827 from Nathan Lucas were for use in the dye bath. Two Connecticut woodworkers, Jeduthern Avery and Samuel Durand, specifically identified a “hat block for finishing hats on.” Sales of hat blocks to Thomas Tilestone, a hatter of Windham, Connecticut, by Amos D. Allen identify block size and fabrication methods: “6 Hatblocks sawed 7 In across at the band, 7 ½ at top, 5 In high” and “1 Hatblock made of seasoned stuf glued and Turned 6 ½ Deep, 7 by 7 7/8.” The cost of a hat block ranged from fifteen to fifty cents depending on size, fabrication, use, and other factors. On occasion, alterations were made to hat blocks already in use, as recorded in Maine by Paul Jenkins.[20]

The hatter’s bow, a rod with an attached string, was an essential tool in creating the body of a hat. The bow string, plucked through use of a wooden pin, created vibrations aligning the foundation fibers into a pad. Covered with a damp piece of linen and compressed with a hatter’s basket—aflat piece of woven work—the pad was exposed to moisture and heat and the fibers gradually matted by hand into a felt forming the body of the hat. The hatter then applied the stiffening, which was solidified in a steam box. One or more layers of fur for the nap were prepared in the same manner, following which the nap was raised with a brush or toothed instrument. The hat was then placed in the dye bath, after which it was washed and dried and turned over to a finisher. Figure 11 provides a visual description of the hat-making process. In the right foreground a workman uses a hatter’s bow, while the background shows other workmen shaping mats in hot water baths. The large wheel is the dyeing mechanism fitted with many blocks on which the hats are hung. The wheel, turned with a crank, immerses part of the hats at a time in the dye bath until they are properly colored. Beyond hat blocks, craftsmen supplied several tools of hat making. Samuel Wing of Sandwich and Abner Taylor of Lee, Massachusetts, made hatter’s bows; Taylor also bored blocks for brushes used in raising the nap. The Proud brothers of Providence and Job Townsend Jr. of Newport, Rhode Island, recorded sales of bow pins. At Philadelphia the accounts of Daniel Trotter list sales of hatter’s baskets and bows.[21]

Although bonnet making was a trade that gave employ and even ownership of a business to many women, the craft was dominated by men. Just as wooden hat blocks were critical to fabricating male head wear, shaped wooden blocks for forming the crowns of women’s cloth hats were critical tools of the millinery trade. Buckram, made of hemp or coarse linen stiffened with sizing, was the common choice for the crown. To this was attached pasteboard or buckram edged with wire to form the front part of the hat, according to prevailing fashion. A cloth lining and a finish cover of silk, satin, muslin, or the like, completed the basic work prior to the application of ornament, such as ribbons, lace, artificialflowers, feathers, and other materials (fig. 12). Many women’s hats were made of straw; some were of domestic fabrication, although Leghorn hats imported from the vicinity of Livorno, Italy, were exceedingly popular. Straw for use in hats was cut to length, whitened (bleached), split, and pressed using a simple machine. The splits were braided into plaits, which were then sewed together to form a hat. American merchants imported both finished hats and plaits for domestic assembly.[22]

Documents identify a variety of woodworking shops that supplied tools and materials for the milliner’s trade. Elizur Barnes of Middletown, Connecticut, sold a customer “Bonnet blocks For Daughter” in 1822. The same decade Deborah Chamberlain purchased “2 bunet blocks” directly from Allen Holcomb at New Lisbon, New York. Two craftsmen, George Landon of Erie, Pennsylvania, and John Cate of Wolfeboro, New Hampshire, sold bonnet blocks produced on turning lathes. Accounts of other craftsmen address the woven hat trade. Solomon Cole of Connecticut provided several customers at Glastonbury with “splits” for bonnets. Two accounts identify a machine to process straw splits: Abner Haven of Framingham, Massachusetts, repaired a machine already in use, whereas Elisha Blossom Jr. of New York constructed a “Mill for pressing split straw” priced at $8.00 for Miss Zebiah Richards. The mill likely had rollers operated by a hand crank. Elizur Barnes went a step further in “Fixing a Box for Bleaching Bonets” for Miss Johnson, milliner. Edward Hazen notes in his discussion of the milliner’s trade that “great quantities of straw are . . . plaited in families, especially in the New-England states, and sold to neighboring merchants, who, in turn, dispose of it to those who form it into hats.” The accounts of Abner Taylor of Lee, Massachusetts, may actually reference this cottage industry in an 1812 charge of $1.75 to a customer for “womens work on bonnets.”[23]

Whereas both hatters and milliners sold many hats individually to customers—and occasionally small boxes to store them—a significant part of the hat business was in quantity sales, which required boxes or cases to transport the merchandise to retail facilities. At about thirty cents apiece, individual boxes for women’s hats were cheaper than those for men, which cost approximately fifty cents apiece, probably reflecting the differences in size of the products. Several hat boxes made of chestnut in eastern Connecticut by Perez Austin cost seventy-five cents apiece, although it is possible that each held more than one hat. Reflecting quantity sales, Austin also charged Joseph Simms $2.50 for “Carrin [carrying] Hats to Norwich,” likely for deposit at a retail facility for distribution or with a coastal trader (fig. 13). The dimensions of a large box to hold men’s hats for broad distribution was recorded by George Ritter at Philadelphia in the 1820s: “a Hatt Box 3 feet 8 long by 2 feet 2 high and 2 feet wide having eight divisions to contain 2 doz Hatts.” In the same decade Nathan Cleaveland of Franklin, Massachusetts, made a significant number of bonnet cases, large and small, for Davis Thayer and Company, charging by the box or the time spent making boxes. On one occasion Cleaveland charged fifty-six cents for “half a days work making Bonnet Cases.” A month later he posted a ninety-two-cent charge for “half a days work myself and Apprentice makeing Cases.” If similar conditions are represented, simple arithmetic indicates the apprentice’s time was charged at thirty-six cents per half day. The accounts of William Wilson, a painter at Lowell, shed light on the further accommodation of bonnets. For one customer he varnished, or stained and varnished, more than a dozen bonnet stands (see fig. 12). Another patron requested that he varnish a “Bonnet tree.” Whether the tree furnished a retail facility or a domestic setting, it served its purpose: display or temporary storage.[24]

Shoemakers

Many references to making a “shoemaker’s bench” or a “shoemaker’s seat” appear in woodworkers’ accounts, and comparison of the pricing suggests the terms identify the same equipment. Common pricing varies from 6s. to 7s. 6p. ($1.00 to $1.25), a few prices lower and several higher, including “a Shoemakers seat with a drawer” at 9s. ($1.50) made by Titus Preston of Wallingford, Connecticut, in 1807 for Phineas Pond. Three shoemaker’s seats, each with a drawer, are pictured in figure 14. Boards abutting the shop window display finished footwear, lasts (foot models) are scattered on thefloor or secured in a wall rack, and a songbird in a cage presages piped-in music of a later era. Tools and pieces of leather are scattered about the room. Edward Hazen described the shop activity in general terms: “The materials are cut out and fitted by the foreman, or by the person who carries on the business [right], whilst the pieces are stitched together and the work finished by workmen who sit upon the bench.” Insight into the preparation of the wooden lasts is recorded by David Pritchard of Wallingford, Connecticut, relative to customer James Harrison: “for the use of my Shop in part to Turn Lasts three weeks.”[25]

In making a boot or shoe of leather, the parts forming the “uppers,” precut to size, were stitched together and attached to a sole, which approximated the length and width of the customer’s foot. Inner and outer soles were attached by sewing and nailing. The workman at left is preparing a leather outer sole on a smooth stone known as a lapstone, which is balanced on his lap. Using the broad face of the shoemaker’s hammer, the leather sole is condensed and made more durable by pounding it. Either this workman or the workman facing him would have presoaked the leather they are working in the stave-formed bucket in the foreground. The workman at center left holds an awl in his right hand to punch holes in a sole to accommodate stitching. The third benchman, his back to the viewer, has shoe thread wrapped around one hand and holds a sewing “needle” fashioned from a hog’s bristle in the other hand. Common shoe thread was made from waxedflax; a stronger variety was made of hemp. The work at hand was placed between the craftsman’s knees and held fast using a shoemaker’s stirrup, a leather loop placed around the work and one knee and held taut by the foot. The benchmen at the right and center use stirrups. A quicker alternative method of fastening soles and uppers of shoes and boots employed wooden pegs, although footwear made by this system was not as durable or as easy to repair. Philip Deland, a woodworker of West Brookfield, Massachusetts, furnished “one peg bench with a drawer &c.” at $3.00 to a shoemaking customer in 1829 along with “one pegsett first rate” at thirty-four cents and a “doubble peg sett.” Deland supplied another shoemaking customer with six awl helves (handles). In Rhode Island Job E. Townsend charged 2s. 3d. (37 1/2¢) for “a Mallet for Pounding Leather.” Useful to the trade were “Boot Trees” for preserving boot shape, which Lemuel Tobey sold to a customer at Dartmouth, Massachusetts (see fig. 14, near right wall) along with a “Sho[e]makers Bench.” A “small Candle stick for shoemaker” made by Robert Whitelaw of Ryegate, Vermont, was useful in winter, when craftsmen of many trades frequently were at the bench before sunrise or after sunset.[26]

The accounts of Wait Stoddard, tanner, currier, and cordwainer (shoemaker), of Windham, Connecticut, with Amos D. Allen, cabinetmaker and chair maker, provide insight into the business of supplying a family with new footwear during a three-year period. A pair of “Calf skin Shoes” bought by Allen for himself at 10s. ($1.67) in January 1800 is described more completely in a later ten-shilling purchase: “1 pair Calf skin Shoes Lin[e]d and bound.” The binding was a thin strip of leather sewed around the top edge. A pair of “Womans Shoes” listed at 7s. ($1.17) may have been fabricated of prunella, a “twilled, worsted cloth” popular for women’s footwear, although the soles were made of leather. Slippers also are listed, one entry describing “4 pair of green slips” at 3s. 6d. (58¢). These may resemble the footwear of the workers seated on the benches in figure 14. Other entries address repairs: “new topping pair [of] boots” or “Soalling pair boots.” If an entire new sole or heel was not required, a piece of leather know as a tap might be used to renew a worn heel or sole. Stoddard supplied Allen with leather for other purposes: calf, morocco, lamb and sheep skins, and “1 Side harness leather” weighing ten pounds. Allen repaid Stoddard for services and materials with a variety of barter goods: bushels of grain, a silver watch, furniture and furniture repairs, and use of his wagon. In the early nineteenth century several communities became shoe manufacturing centers, supplying in part the export market, including Lynn, Massachusetts, where “scarcely a house . . . is not inhabited by a shoemaker,” and Newark, New Jersey, where one manufacturer employed from 300 to 400 workmen.[27]

Other Crafts

References to the interactions between woodworkers and other members of the craft community in the material at hand are scattered, although they document the nature of those contacts. Most common are references to individuals in the metal-working trades. George Ritter of Philadelphia repaired “a T-square” in 1837 for the journeyman of Nicholas Kohlencamp, a tinsmith. Several references focus on iron processing. In 1790 Job Danforth Sr. of Providence, Rhode Island, billed Amos Throop for “work Done on y[ou]r black smiths shop.” Danforth returned three years later for a job of “diging and puting a pipe to [the] water works,” identifying the power source used to operate the bellows in Throop’s forge. Water, apparently, was the power that operated the large trip hammer that William Fifield serviced two decades later at James Proctor’s iron works at Lyme, New Hampshire, a town watered by three streams that empty into the Connecticut River. At Atsion Furnace in the pine barrens of central New Jersey, work often focused on patterns for stoves and chimney backs. Two Philadelphia craftsmen, John Folwell in the 1770s and Daniel Trotter in the 1780s, supplied some of the “molds” necessary for casting. Trotter also furnished patterns for sash weights and andirons.[28]

The button, a fastener for clothing, was an item of popular request. Crafted from many materials—base or precious metal, bone, mother-of-pearl, glass, wood—the button represented a basic convenience or a fashion statement. Merchants imported quantities of buttons, and by 1798 Timothy Dwight, president of Yale College and commentator on New England society of the early republic, noted a substantial manufacture of “gilt buttons” in the town of Waterbury, Connecticut. Before the widespread availability of manufactured buttons, however, inexpensive turned wooden button molds were in the market. Ranging in price from slightly more than 1d. to 3d. (1 1/2–4¢), these disks were covered with cloth appropriate to their use. A notice for a runaway “Irish Servant Man” in the New York Weekly Journal of March 22, 1742, describes the clothes worn by the absconder: “a Felt Hat, a blue drab jacket, an outside Jacket black and white homespun drugget [a coarse common cloth] shorter than the blue one, Buttons covered with the same.” Thomas Pratt of Malden, Massachusetts, sold “fifteen buttonmolds” to a customer in the following decade for one pence apiece, but that quantity was eclipsed some years later by purchases made at Ipswich by Benjamin Ross, who likely was a tailor. From 1781 to 1783 Ross acquired 237 dozen molds at two pence per mold and thirty-four and one half dozen at three pence. He also purchased a “but[to]n hole board,” probably a gauge to size buttonholes to buttons.[29]

Craft and Profession

Barbers and Dentists

Specialized seating for barbers and dentists was uncommon until the early nineteenth century. Prior to that time chairs with tall backs to support the head were pressed into service when needed. “Elbows” to support the arms, although convenient, were not necessarily present. As dedicated chairs came onto the market, an adjustable headrest became a feature (fig. 15). Some chairs also had legs of extra length. George Landon, a cabinetmaker of Erie, Pennsylvania, sold a “Barber Chair” in August 1821 to a customer for $2.50. The cost included the 62 1/2¢ Landon credited to another individual in that month for “irons for [back of] barber chair.” Shaving customers was as important a function of the barber as was cutting and dressing hair. Smith and Lippins, black barbers at 365 Broad Street in Newark, New Jersey, near David Alling’s chair manufactory, placed an order with Alling in 1837 for a barber chair, four Windsor chairs, and two low stools to furnish or expand the seating at their place of business. A low stool could support a customer’s feet when “in the chair.” Another customer ordered a caned curled-maple barber’s chair and a “morocco” seat cushion en suite. One focus of George Ritter’s cabinetmaking business at 72 North Fourth Street, Philadelphia, a few years earlier was chairs for dentists. McElheney and Van Pelt purchased “a Dentists portable mah[ogan]y chair with fall Back hung with quadrants, & [a] circular Screw seat” at $15.00. The seat was similar to a piano stool, and the quadrants were quarter-circle metal hinges for adjusting the chair back. A related “mahagany Dentists operating chair” made for another customer for $25.00 had a “screw circular seat stuffed with curled hair & covered with black hair cloth.” Samuel C. Bunting, a merchant on Third Street, placed an unusual order for a mahogany dentist’s chair with quadrants and revolving seat that stood on a board 3 feet, 5 inches long and was equipped with a “Mah[ogan]y toe board [and] irens underneth” the seat. The chair was not unlike a seat for an invalid without the large wheels. Bunting also requested a packing box, special packing, and portage to his shipping location at 28 South Wharves, where the chair was forwarded to the customer. Shopping in urban areas in this period was accomplished principally on foot. Proximity of location and the high level of Ritter’s skill, as attested in his accounts, attracted Bunting and others to his shop. Whether in an urban setting or a town location, however, a hanging trade sign at a dentist’s door, such as that illustrated in figure 16, could be quite direct.[30]

Physicians and Apothecaries

Prior to the mid-eighteenth century gaining a medical education in America was accomplished by serving an apprenticeship with a practicing physician or surgeon. Medical ranks were strengthened in urban areas by the arrival of individuals trained in the centers of learning in Europe. Gradually the study and practice of medicine in America became systematized, with marked improvement of professional standards. Philadelphia, for example, became a center of medical activity where young men were encouraged to travel abroad to study at the important centers of Edinburgh, London, and, occasionally, Paris. Medical lectures, papers, and research began to be published regularly and disseminated. By 1756 the city’s medical profession realized a long-held goal of opening a hospital to serve the community. There followed in the 1760s the establishment of a medical school at the Pennsylvania Hospital and another at King’s College (later Columbia), New York. Members of the associated craft of apothecary specialized in preparing “different ingredients to form [medicinal] compounds,” and besides serving physicians they could prescribe treatment and distribute remedies to their own clientele. When an area was without an apothecary, local physicians supplied the medicinal needs of patients (fig. 17). Dr. John Brickett, who also was an apothecary, is seen holding a leather-bound copy of Materia Medica, describing the natural and compounded substances used in treating diseases. Colleges of pharmacy were established in Philadelphia and New York during the early nineteenth century.[31]

Nests of drawers, or cases, were common at the business site of both the physician and the apothecary. As early as 1759 Dr. John Newman ordered “a Case with 40 small Draws” for £1.12.0 ($5.33) from a member of the Lunt family at Newbury, Massachusetts. Many decades later, in 1824, Dr. Charles Dyer of Middletown, Connecticut, paid Elizur Barnes $68.00 for “a Case of apothacary in 4 parts—34 Draws in Each, Total 136 Draws at 50 ct” each. Whereas nests of drawers were popular with members of the medical community throughout New England, they also were in use in the Middle Atlantic and other regions. Wilmer Worthington of West Chester, Pennsylvania, probably an apothecary, acquired “A Medacine Case (27 Draws)” in 1826 from Amos Darlington Jr. Upon installation of a case of drawers, the proprietor of a shop arranged to have the contents labeled. Daniel Rea Jr., ornamental painter of Boston, had several calls of note. “Paint[in]g & Lableing” for Dr. William Jackson in 1792 included sixty large drawers and seventy of smaller size. A job for Samuel Miller, an apothecary, included painting, ornamenting, and labeling fifty-seven drawers. Miller also requested Rea to paint, gild, and label thirty-one bottles. Truman and Company was hired by William Allen of Providence, Rhode Island, in 1784 to paint “Specia Bottles,” large containers used for storage. The same year Samuel Blythe painted and gilded two “Canisters,” or small boxes, possibly made of metal, at Boston for Dr. William Sterns. Wooden boxes were particularly useful in the medical business for drugs, pills, salts, and the like. Robert Rantoul, an apothecary and minor merchant of Beverly Massachusetts, engaged Ebenezer Smith Jr. in 1812 to cut “14 lb Quasha wood,” a medicinal bark or wood from Surinam (formerly Dutch Guiana) used to make a tonic. A storage box would have been useful, or perhaps Rantoul had a “pair of large Drawers for Drugs,” as found on the premises of David Eaton in Chester County, Pennsylvania. By the 1840s wholesale druggists were established in commercial centers such as Philadelphia, where J. and J. Reakirt occupied a prominent corner location and displayed a hanging mortar and pestle along with theflat signage on their building (see fig. 4).[32]

When details are unavailable, the medicine chest is distinguished from the medicine case by its price, which centered in the one-dollar range. That was the cost of Dr. Dyers’ chest; his case, with its many drawers, cost $68.00, as indicated. Dr. Burley Smart ordered a “medicen chest with Lock” at Kennebunk, Maine, for $1.00 from Paul Jenkins. A more particular account of a chest describes one made for Dr. Jonathan Easton in 1798 at Newport, Rhode Island, by Job E. Townsend: “To A medeson Chest 20 Inches Long and 14 Inches Wide & 7 Deepe, In the clear [open interior] 12 Partings [partitions].” The 15s. charge ($2.50) reflects the overall size of the case and the extra work of installing the partitions. Dr. Dyer’s patronage of Elizur Barnes extended to the purchase of furniture for his establishment in the form of “a Cherry Show Case” at $6.50. Some physicians placed emphasis on other forms (fig. 18). Dr. John Morris of York, Pennsylvania, used a sturdy paneled cupboard and shelving to support his labeled bottles, large and small, and a long chest with tiers of drawers both for other medical storage and as a support for a distillation apparatus. A “large pine book case with 2 drass [drawers] & painted in Side & out” purchased by Dr. Smart from Paul Jenkins was a form found in other physicians’ offices. The 1838 estate papers of Dr. Jacob Ehrenzeller at West Chester, Pennsylvania, list a “Book case” in the “Office” valued at $10.00 and “Books in Book case” estimated at $50.00, describing a substantial medical library. A desk and portable desk also furnished Dr. Ehrenzeller’s office. Throughout the period of this study, the desk was considered essential equipment for a physician. A “Wrighting Desk & Stool” purchased from David Evans in 1790 at Philadelphia cost Dr. John H. Gibbons £2.12.6 ($8.75). With Evans’s cabinet shop being at 115 Mulberry (Arch) Street, Gibbons office at 103 Mulberry was just a short walk away.[33]

Stores and Shops

The terms store and shop frequently are defined as interchangeable words, each representing a place where goods are kept for sale. Occasionally the store is identified as a shop of large size. The following discussion will focus principally on businesses described as stores in recorded transactions with members of the woodworking community. Shops are included when the nature of their business purchases suggests, or as a directory listing or other information signifies, that substantial retail activity was pursued.

In most cases a moderate retail business is identified when either or both of two types of business furniture is indicated—the counter, such as that in the store of Captain Andrew Johnson (fig. 19), or the showcase. Peter Marselis’s work at New York in 1779 for the firm of Taylor and Bayard involved “making a Dish Counter & Shelves in their Store.” In many cases the counter may have been no more than a sturdy box open at the back, with or without a bottom. That would explain storekeeper William Barrell’s hiring John Hall, a carpenter of Philadelphia, to install a bottom in his counter, or Job E. Townsend’s work for a customer at Newport, Rhode Island, in constructing “a Draw for his Counter in Shop.” George Ritter of Philadelphia made a special drawer accommodation described as a “patent Spring thimble-drawer lock with two Keys for counter drawer,” and at Litchfield, Connecticut, Silas E. Cheney recorded another occasional job as “putting railing to Counter.” Cherry is identified in one instance as the material of the counter, although the variety of finishes described in accounts indicates that cheaper woods were more common for counter construction. Thomas Boynton recorded painting a “Counter mahogony” at Windsor, Vermont. The material of Boynton’s counter may have been white pine, a wood he is known to have used in his shop. Pifer Washington Case of Johnstown, New York, employed “Stain for Counter Tops,” although he also used “graining Color,” as did William Wilson, a painter of Lowell, Massachusetts. Both craftsmen applied a final varnish coat to protect the grained surfaces.[34]

A “Glass show Case” ordered from Philomon Robbins of Hartford, Connecticut, in 1834 by Colton and Williams cost $30.00 for the work. That was a relatively high price, although the showcase form represented a more expensive piece of equipment than the counter. Construction of Robbins’s showcase involved building sections of window sash and incorporating them into the overall design of the case. Providing some insight into the appearance of a showcase is Elizur Barnes’s description of a job undertaken the previous decade for a customer at Middletown, Connecticut: “To a Show Case with Cherry Sash front & top.” After initial construction of the showcase, there still remained the work—and sometimes the expense—of glazing the sash. Accounts suggest that some glazing was carried out by someone other than the builder. For example, Frederick Coady of Ogdensburg, New York, charged Hecock and Curry eighty cents to set “8 Lights in Show Case.” At Newport, Rhode Island, Job E. Townsend recorded “Putting Railing on his Glass Case” for Harvey Sessions. Other tasks mimic those in finishing the counter, such as “Painting a Show Case mehogony Colour” or “Staining,” with varnish as a final coat.[35]

Temporary storage was necessary in stores and shops, and installing drawers and shelves was a convenient way to accommodate some types of merchandise. Following the practice of apothecaries, William Barrell and Christopher Champlin, merchants respectively of Philadelphia and Newport, Rhode Island, installed nests of drawers. In other circumstances larger drawers were more useful. Christopher H. Talcott of Coventry, Connecticut, paid $5.00 to have drawers made for his store, and Elias Redfield of Essex acquired “six draws for shop” at a cost of $4.50. The exact purpose of the drawers is rarely identified. Edward Jenner Carpenter, apprentice cabinetmaker in the Greenfield, Massachusetts, shop of Miles and Lyons, commented in his journal in November 1844 on a job for the store of Dewey and Clark when “making 28 drawers for them to keep their groceries in.” Painting and lettering, or painting and graining, frequently followed drawer installation. For a client’s store in Albany, New York, Ezra Ames, artist and ornamental painter, completed a sizable job in 1796 described as “painting [and] lettering 70 draws” at £1.12.0, “painting & lettering 8 boxes” at 4s., and “lettering 10 barrels” at 5s., for a total cost of 41s. ($5.12 1/2, New York currency). By contrast, the cost of putting shelves in a store or shop frequently was more modest (fig. 20). Day and Pollard, storekeepers of Washington County, Vermont, paid William Ripley $1.00 for installing shelves, a typical cost for many jobs. Specific dimensions are rarely given because shelf length and number varied depending on interior space and the kinds of goods to be shelved. An 1815 account of Silas E. Cheney for Sophia Jones, proprietress of a shop at Litchfield, Connecticut, describes “makeing shelves,” supplying a “Counter,” and “fixeing Draws” all for $5.00. Apart from drawers and shelves, Job E. Townsend assisted customer Harvey Sessions in December 1821 with a “Cloth Roller” at his store in Newport, Rhode Island, by making a “New Exeltree” for the roller. The following August, Townsend was back for a job of “Putting up his Meshene for Rolling Cloth,” probably the same cloth roller assembled and used only periodically when new merchandise arrived. A third call in April 1823 found Townsend mending the “Roling Mesheene frame.”[36]

On occasion one of several case pieces stood in a store or shop to supplement the counter or showcase. Proprietors of stores doing a substantial business would have found a desk convenient (fig. 21). Three woods are mentioned for the desk in the records at hand: locust, cherry, and pine, the cherry desk the most expensive at $10.00. Minor related work included repairing a lock, replacing a desk fall (lid), or supplying a stool to use at the desk. A table could also serve as a desk or as a surface to hold merchandise. A bookcase would have been an appropriate companion to the desk. A “Book Case in ye Shop” made by carpenter Samuel Hall for David Sage at Middletown, Connecticut, in 1788 required “3 Days & half” of labor and consumed “21 feet of Pine Bords” and “80 Brads and Nailes,” with “9d worth of Glue.” Major Nathan Dillingham of Lee, Massachusetts, ordered a “deep Cupboard” for his shop in 1815 from Abner Taylor, likely as a supplement to the “large drawer & cletes” (handles) acquired two years earlier. Incidental seating in stores and shops usually consisted of a few inexpensive chairs or stools, but occasionally there was a notable exception. Amos Bradley of East Haven, Connecticut, supplied Abram and Jared Bradley, owners of a store and packet, with three chairs in 1807 priced at $1.50 each, identifying either Windsor or fancy chairs. Some thirty years later the firm of Smith and Wright, saddle and harness manufacturers at Newark, New Jersey, made an attractive choice in “6 curld [maple] counter stool[s]” purchased from David Alling.[37]