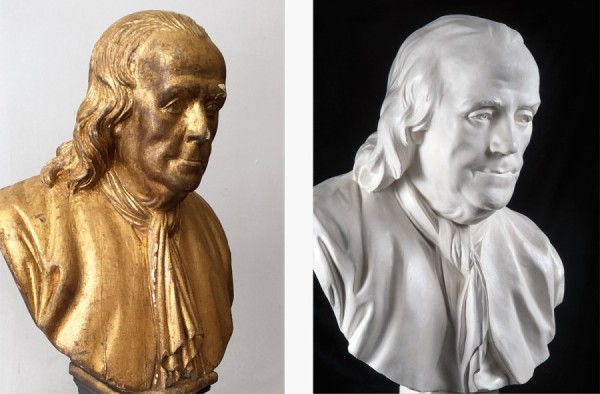

Bust of Benjamin Franklin, attributed to Martin Jugiez, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1779–1790. White pine; iron. H. 35". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

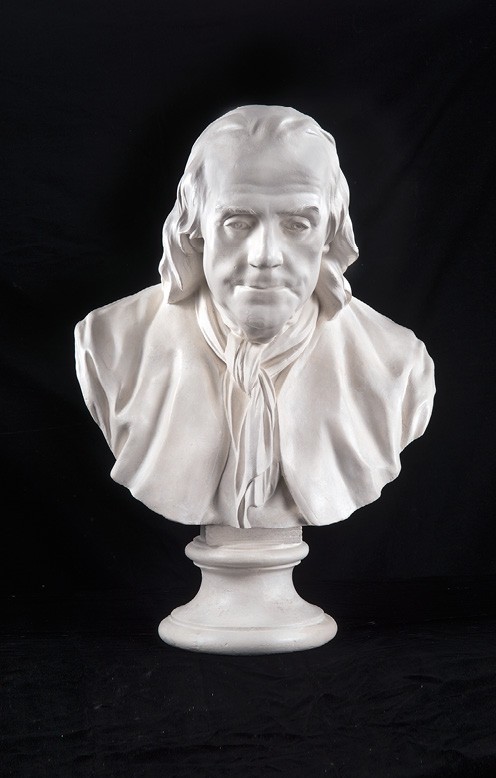

Jean Jacques Cafferi, Benjamin Franklin, Paris, France, 1779–1805. Plaster. H. 28". (Courtesy, The New York Historical.)

Pier table with carving attributed to Hercules Courtenay, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1770. H. 32", W. 54", D. 27". (Courtesy, Rhode Island School of Design, bequest of Charles Pendleton.)

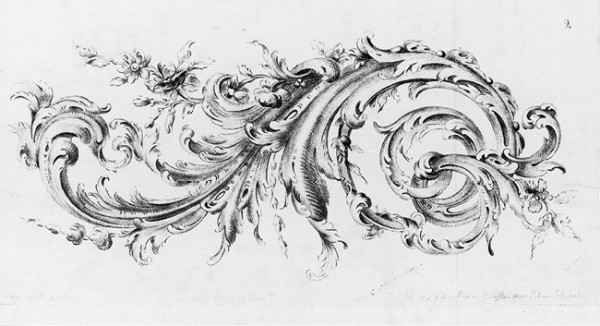

Design for a chimneypiece frieze -illustrated on plate 12 in Thomas Johnson’s A New Book of Ornaments, by Thos. Johnson Carver, Design’d for Tables & Friezes; Useful for Youth to Draw After (London, 1762). (Courtesy, © Victoria & Albert Museum.)

Detail of the knee carving on the table illustrated in fig. 3

Side chair with carving attributed to Martin Jugiez, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1765. Mahogany. H. 39", W. 25 1/2", D. 23 1/2". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chair is from a set of at least six.

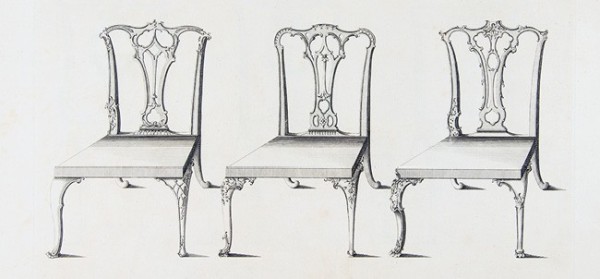

Design for a side chair shown on pl. 12 of the first and second editions of Thomas Chippendale’s The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (1754; 1755). (Courtesy, Winterthur Library.) This design appears on pl. 14 in the third edition (issued in loose sheets in 1762 and as a complete volume in 1763).

Side chair with carving attributed to John Pollard, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1769. Mahogany with white cedar and yellow pine. H. 37 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Christie’s.) This example, which has the period ink inscription “Deshler” on its slip-seat frame, is from a suite comprising at least six side chairs, two card tables, and an easy chair.

Designs for side chairs shown on pl. 13 in the first and second editions of Thomas Chippendale’s The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (1754; 1755). (Courtesy, Winterthur Library.) This design appears on pl. 10 in the third edition (issued in loose sheets in 1762 and as a complete volume in 1763).

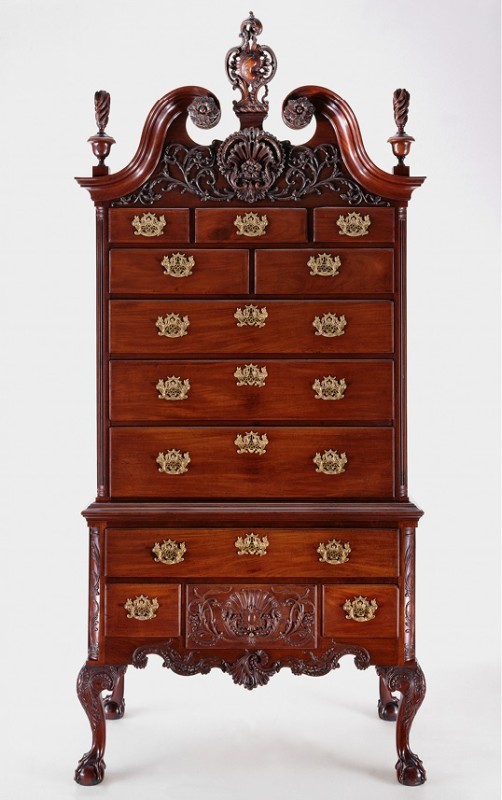

High chest of drawers, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1750–1760. Mahogany with white cedar and tulip poplar. H. 102 1/2", W. 46 1/8", D. 21 3/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Dressing table, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1765–1775. Mahogany with white cedar and tulip poplar. H. 28 3/8", W. 37", D. 18 3/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Details showing the carving on the lower center drawer in the base of the high chest illustrated in fig. 10 (left) and in the dressing table illustrated in fig. 11 (right). (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, ca. 1765. Mahogany with maple and oak. H. 38 1/4", W. 25 1/2", D. 18 1/4". (Courtesy, Wadsworth Atheneum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, England, ca. 1765. Mahogany with beech. H. 37 1/4", W. 23 1/4", D. 19 1/4". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; gift of Mrs. Joshua Crane in memory of her husband.)

Side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, ca. 1765. Mahogany with maple. H. 37 7/8", W. 25", D. 22". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Details showing the crests of chairs identical to the examples illustrated in fig. 15 (left) and fig. 14 (right).

Details showing the knee carving of the side chair illustrated in fig. 15 (left) and a chair identical to those in the Phillips set (fig. 14) (right).

Detail showing the nail holes from pattern attachment on the side chair illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Carving pattern from the shop of Gideon Saint, London, ca. 1760. (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art; photo, Art Resource.)

Side chair with carving attributed to Hercules Courtenay, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1770. Mahogany. H. 41 1/2", W. 21 1/2", D. 17". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1770. Mahogany. H. 41 1/4", W. 23", D. 21 1/4". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Details of the splats of the side chairs illustrated in figs. 20 (left) and 21 (right).(Photos, Gavin Ashworth.)

Details of the knee carving on the side chairs illustrated in figs. 20 (left) and 21 (right).(Photos, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the right truss on the chimneypiece from the parlor of the Samuel Powel House, Philadelphia, 1770. (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Armchair with carving attributed to Hercules Courtenay and an anonymous competitor, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1770. H. 40 1/4", W. 25 1/4", D. 21 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Armchair with carving attributed to Hercules Courtenay, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1770. H. 40 1/4", W. 25 1/2", D. 22". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The mate to this armchair is in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Details showing the backs of the arm-chairs illustrated in figs. 25 (left) and 26 (right). (Photos, Gavin Ashworth.)

Details showing the knees of the arm-chairs illustrated in figs. 25 (left) and 26 (right). (Photos, Gavin Ashworth.)

Details showing the arm supports of the armchairs illustrated in figs. 25 (left) and 26 (right). (Photos, Gavin Ashworth.)

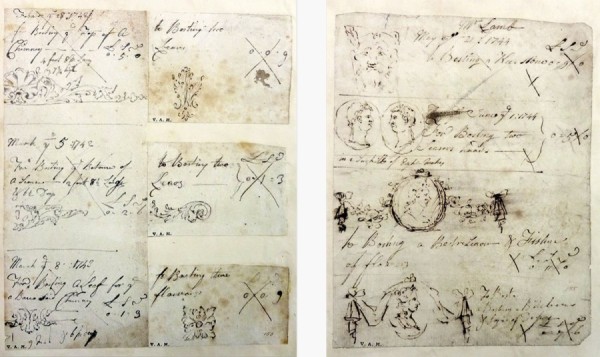

Accounts from the papers of Matthias Lock with drawings, notations, and charges for carving, London, 1742–1744. (Courtesy, © Victoria & Albert Museum.)

Charles Willson Peale, Lambert Cadwalader, 1770. Oil on canvas. 51" x 40 7/8". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art.)

Side chair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1769. Mahogany with white cedar. H. 36 3/4", W. 23", D. 21". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Easy chair attributed to the shop of Thomas Affleck with carving attributed to Bernard and Jugiez, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1771. Mahogany with yellow pine, white oak, white cedar, black walnut, and tulip poplar. H. 46", W. 36 1/2", D. 34". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 125th Anniversary Acquisition, gift of H. Richard Deitrich, Jr., 2001; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Card table attributed to the shop of Thomas Affleck with carving attributed to the shop of James Reynolds, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1771. Mahogany with yellow pine, white oak, and tulip poplar. H. 28 3/4", W. 39 3/4", D. 19 3/4". (Courtesy, Dietrich American Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Card table attributed to the shop of Thomas Affleck with carving attributed to the shop of James Reynolds, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1771. Mahogany with yellow pine, white oak, and tulip poplar. H. 28 1/2", W. 39 1/2", D. 19 3/4". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the carving on the leg of the easy chair illustrated in fig. 33.

Bernard and Jugiez, truss over a door in Cliveden, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1766. (Courtesy, Cliveden; photo, Luke Beckerdite.)

Details of the carving at the center of the front rail of the card table illustrated in fig. 34 (top) and fig. 35 (bottom). (Photos, Gavin Ashworth.)

Pier glass attributed to the shop of James Reynolds, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1771. White pine; gesso, gold leaf. 55 1/2" x 28 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Details of the carving on the pier glass illustrated in (fig. 39).

Details of the carving on the front rails of the card table illustrated in fig. 34 (top) and the card table illustrated in fig. 35 (bottom). (Photos, Gavin Ashworth.)

Details of the carving on the legs of the card table illustrated in fig. 34 (left) and the card table illustrated in fig. 35 (right). (Photos, Gavin Ashworth.)

Charles Willson Peale, Martha Cadwalader, 1771. Oil on canvas. 50 3/4" x 37 9/16". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art.)

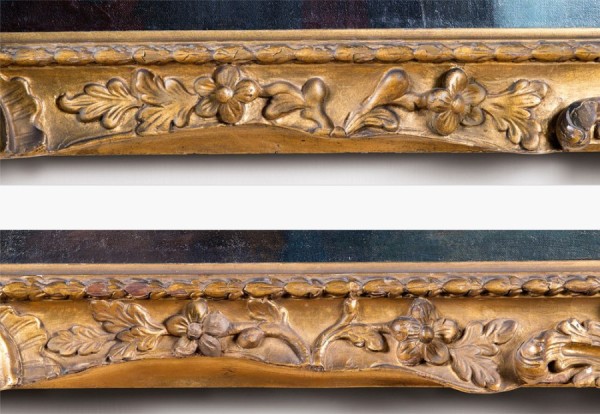

Details of the carving on the frames of Charles Willson Peale’s portraits of (right) Lambert Cadwalader and (left) Martha Cadwalader. (Photos, Gavin Ashworth.)

Details of the carving on the frames of Charles Willson Peale’s portraits of (right) Lambert Cadwalader and (left) Martha Cadwalader. (Photos, Gavin Ashworth.)

Details of the carving on the frames of Charles Willson Peale’s portraits of (top) Lambert Cadwalader and (bottom) Martha Cadwalader. (Photos, Gavin Ashworth.)

Details of the carving on the frames of Charles Willson Peale’s portraits of (left) Lambert Cadwalader and (right) Martha Cadwalader. (Photos, Gavin Ashworth.)

Details of the busts illustrated in figs. 1 and 2.

Among the engravings in the [Harvard] library, was one from a painting by . . . [Charles Antoine] Coypel, Rebecca at the well . . . . This I admired and copied in oil, the same size as the engraving; the forms, expressions, characters, and light and shadow were before me; the colors I imagined as well as I could from my own imagination. This received so much approbation from the officers and students in college, that I ventured to show it to Mr. Copley, and had the pleasure to hear it commended by him also.

John Trumbull, 1773

FOR CENTURIES, PAINTERS, engravers, and sculptors have produced copies of earlier works. This practice was typically performed to refine one’s skills or satisfy the demands of a patron who wanted an object renowned for its beauty, historical importance, or technical achievement (figs. 1, 2). In the decorative arts, copying was much less common. A chair maker might have produced seating that resembled a fashionable import, or a cabinetmaker might have made a case piece to augment an object produced by another craftsman, but few eighteenth-century artisans attempted to totally replicate the work of others. This essay will examine the concept of “copying” in the carving trade, both from a functional standpoint and as interpreted by modern scholars. It will also show why the production of exact replicas in that medium, as well as many others, was usually impractical in terms of cost and labor.[1]

Copying had a role in the carving trade, but it typically occurred on the drawing table rather than at the bench. Drawing was an essential skill that apprentices developed by copying the conceptual and working designs of their masters. During his tenure in the shop of London carver James Whittle, Thomas Johnson copied the drawings of fellow journeyman Mathias Lock, whom he, and many others, considered “the best Ornament draughts man in Europe.” Copying designs and drawings on paper also helped apprentices develop working styles that aligned with their masters’. This is clearly seen in the carving of Hercules Courtenay, who served his apprenticeship with Thomas Johnson before immigrating to Philadelphia. The outlining and modeling of Courtenay’s leaves, which often have multiple overlaps and complex twists and turns, bear a striking resemblance to Johnson’s published etchings that, along with a few watercolors, are the only documented examples of the latter’s work (figs. 3–5).[2]

Furniture scholars often refer to cabinetmakers and carvers “copying” designs like those published by Johnson and Thomas Chippendale, but that was rarely the case. Unlike full size shop drawings, which were supplemented by models, patterns, and procedures to regulate production, etchings in design books lacked sufficient detail for true copying. The latter were intended to illustrate objects or ornaments that reflected current tastes, provide craftsmen with designs that could be adapted or altered to conform to their working styles and tool kits, and promote their publisher. As the preface to Thomas Chippendale’s The Gentleman and Cabinetmaker’s Director (first distributed as loose sheets in 1753 and then as a complete volume in 1754) notes, his publication was “calculated to assist the . . . [gentleman] in the Choice, and the [cabinetmaker] in the Execution of the Designs; which are so contrived, that if no one Drawing should singly answer the Gentleman’s Taste, there will be found a Variety of Hints, sufficient to construct a new one.”

A side chair attributed to Philadelphia carver Martin Jugiez shows how artisans used published designs as guides rather than patterns to be copied literally (fig. 6). The maker of that object was clearly inspired by a chair design illustrated on plate 12 in the first and second editions of Chippendale’s The Gentleman and Cabinet Maker’s Director (fig. 7), but Jugiez’s chair differs from the etching in having gadrooning below the seat rails; simple, rounded rear legs; and front legs with a shallower curve. His carving departs even further from Chippendale’s design, incorporating a flower with a stippled reserve on the knees and different leaves both there and on the knee blocks. Those details were part of Jugiez’s design vocabulary, and they occur on many other examples of furniture and architectural carving attributed to him.

The degree to which carvers and furniture makers adhered to published designs was largely determined by their patron’s tastes and budget, at least for highly skilled craftsmen like Jugiez and his contemporary, John Pollard, both of whom were capable of performing the most technically demanding work. When Germantown, Pennsylvania, merchant David Deshler commissioned the set of side chairs represented by the example illustrated in figure 8, he could have instructed the maker and carver to follow one of the engravings in Chippendale’s Director precisely. Instead, he approved a design that incorporated just three details from the chair on the left of plate 13: the husk in the center of the crest, the trefoil at the base of the splat, and the leafage directly above (fig. 9). Philadelphia carvers like Pollard, to whom the Deshler ornament is attributed, routinely adapted London carved designs to suit local tastes for seating and other furniture forms, which in side chairs typically included stump legs at the rear and cabriole legs with claw-and-ball feet in the front.[3]

Even when consumers commissioned objects to fill out sets or suites, they did not expect “copies” in the literal sense of the word. A high chest and dressing table that descended in the family of Philadelphia merchant Michael Gratz illustrate the point (figs. 10, 11). Although these objects are visually similar and were once thought to be contemporaneous, the dressing table is probably a five to ten years later than the high chest. The chest has original plate brasses, whereas the dressing table was originally fitted with bail and rosette brasses. Comparison of the appliques and shells on the center drawer in the base of the high chest and in the dressing table reveals the work of two carvers (fig. 12). Although the designs are similar, the carvers used different tools and different techniques in performing their work. For example, when the carver of the high chest modeled and shaded his leaves, he stopped his cuts short of the leaf ends; the carver of the dressing table did not. There was no effort by the later hand to mimic precisely the carving of the earlier craftsman, nor any expectation on the part of the patron that the work on the high chest and dressing table would be identical.[4]

As the Gratz high chest and dressing table suggest, some carvers had access to objects their patrons wanted “copied.” The Boston side chair illustrated in figure 13 is part of a large group of seating, the design of which was likely derived from a set of English chairs that reputedly belonged to merchant William Phillips Sr. (fig. 14). As might be expected, the appearance and construction of the earliest chairs in the Boston group are the closest to the imported model, having hairy paw feet and veneered rear seat rails. Later examples from this Boston group typically have solid mahogany rear rails and either paw or claw-and-ball feet. (fig. 15).[5]

The carver of the Boston chairs appears to have taken rubbings of the ornament on the crest, splat, and knees of Phillips’s chairs, but he changed the designs to accommodate his tools and techniques. This is most discernable in the gouge cuts used to set in the leaves on the crests and knees (see figs. 16, 17). Small wrought nail holes in the knee acanthus of all the chairs in the Boston group indicate that their carver created patterns, which he used to transfer his designs from piece to piece (fig. 18). Two settees and more than thirty chairs from several different sets have similar knee carving, and in almost every instance the nail holes are in the same locations. The angular shape of New England cabriole legs was particularly suited to that type of design transfer. In contrast, the British chairs do not have nail holes. If the patterns for their carving were attached with nails, the holes were most likely in the adjacent ground, which would have been removed in the relieving process.[6]

Few eighteenth-century carving patterns survive, probably because most were made of paper and either wore out or were discarded when styles changed. An example from the portfolio of London carver Gideon Saint is typical in being made of paper and in delineating the outline of a design that required frequent replication, in this instance a leaf motif most likely used for the sides, top, and bottom of a picture frame (fig. 19). To produce the pattern, Saint folded a sheet of paper in two, drew half of the motif on the right side, refolded the paper, then used a pin to prick through the drawing and create a symmetrical design. By pricking through the pattern into his work-piece or dusting the pattern with pounce, Saint or one of his workmen could transfer the basic outline of the design and use a pencil to fill in missing or pertinent information. Patterns of this type could also be shared with, or duplicated for use by, subcontractors. They were used to regulate, standardize, and expedite production but did not include enough detail to permit the production of exact copies.[7]

Hercules Courtenay and an anonymous competitor appear to have used the same or duplicate patterns to lay out the carving on the crests and splats of several rococo side chairs (see figs. 20, 21) and armchairs, all produced in the same cabinetmaking or chair making shop. Although visually similar, the ornament on the two groups of chairs is divergent because Courtenay and his competitor had different tool kits and carving styles, which were ingrained during their apprenticeships and work as journeymen. The most obvious areas of divergence are in the ribbon and knee carving (figs. 22, 23). On Courtenay’s knees, the convex surfaces of the leaves are broader and more rounded, and the concave surfaces have finer shading. In addition to spotlighting differences in these carvers’ techniques, the knee carving suggests that Courtenay produced the original pattern for that design. As his documented trusses in the Samuel Powel House reveal, Courtenay’s leaves typically have small lobes that flip over and convex surfaces (occasionally articulated with chip cuts) leading up to that point (fig. 24). The carver responsible for the other group of chairs attempted to mimick the flipped lobes, but not the modeling preceding them. Numerous instances of different carvers working from the same or similar patterns as well as influencing each other’s work are known, as the appendix to this article reveals.[8]

In The London Tradesman (1747), Robert Campbell wrote that many carvers, particularly those involved in chair work, “are generally Paid by the Piece, according to the Pattern of the Work.” This system of production allowed chair makers and cabinetmakers to subcontract work as needed rather than have one or more carvers in their workforce. The carved components of the side chairs illustrated in figures 20 and 21 may represent piecework, although Courtenay and his competitor appear to have collaborated occasionally. Both hands are present in architectural carving from the Blackwell parlor (Winterthur Museum) and on contemporaneous furniture. The tassel-back armchair illustrated in figure 26 has arm carving attributed to Courtenay, but the remainder of the work is by the hand responsible for the side chair shown in figure 21. Two very similar armchairs from the same shop are attributed to Courtenay alone (see figs. 26–29). This shop most certainly used piece work components in the production of seating. Arm supports were typically cut to seat neatly into notches in the side seat rails, like those on the armchair illustrated in figure 25, yet on the examples represented by the armchair shown in figure 26, the arm supports were coped. The notches in the side rails of the latter armchair had to be patched to accommodate the shaping on the underside of the arms, which strongly suggests that those rails, and likely the arm supports and other components were piecework.[9]

In some shops, master carvers produced models to guide the work of their apprentices and journeymen and, in certain instances, record details for future use. In his autobiography, London carver and designer Thomas Johnson recalled:

I told . . . [James] Whittle he had given me nothing worth doing with my own hands, and informed him I had carved a girandole [‘in a taste never before thought on’], if he pleased to see it I believed it would convince him there was no work in his shop that I was not capable of doing. I shewed him my girandole, which he purchased immediately . . . and bespoke a fellow to it; and so great was it esteemed, that many of his men took molds from the heads of the figures.

The section on sculpture in Robert Campbell’s The London Tradesman refers to the “Master-Statuary” drawing his design on paper, then “forming a model in Clay or Wax, from whence the Workman Blocks out the Figure in Stone.” Carving masters undoubtedly followed similar procedures, although they may also have made models in wood. No colonial models are known to survive, but they were most likely used in the production of components made repetitively. Examples would be claw, paw, and scroll feet; the flame sections of finials; and pediment ornaments like the cartouche variant common on case furniture attributed to Philadelphia carver Nicholas Bernard. For a frame made for “His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales’s picture,” Thomas Johnson “made the model, and executed the principal.” In this instance the model was most likely done to work out problems and finalize the design before beginning work on the frame. It is also possible that the model was smaller in size.[10]

In large carving shops, procedures like boasting were used to turn out consistent work, increase production, and optimize each craftsman’s abilities. According to Thomas Sheraton’s 1803 The Cabinet Dictionary (London: W. Smith),

Boasting, amongst carvers and statuaries . . . . is the great ground work of the finer parts of relief, and requires the skill of a master in carving . . . . Those carvers which are the ablest in drawing, are for the most part employed in boasting, as they are the best acquainted with the necessary projecture to be given to the respective parts. Hence it becomes the province of the boaster, after making out the sketch, to shape the outline by gouges or saws, and then make out the prominences of each part, by glueing on pieces of wood for that purpose. These rude pieces are glued to a board, and paper inserted between to make the carving come off easier when finished. When the work is sufficiently dry, the boaster proceeds to place his gouges by a judicious choice of such kind as will suit the turn of the parts . . . ; for to have more would only hinder him. Lastly, he proceeds to give the principal strokes of the whole piece . . . . This being a sufficient guide, the work is put into the hands of the carver, who is in the habit of giving the finishing strokes. In small factories, it is common for one carver to begin and finish the whole of carving. But where there are a number of hands employed, and in pieces that require much skill, the other is the most preferable way.

As Sheraton’s definition suggests, boasting was typically done on large appliques and high relief or three-dimensional work. Two pages of sketches and notations by Matthias Lock record his work boasting for chimneypieces, a figural keystone, a sconce, and profile busts during the 1740s, probably while working in James Whittle’s shop (fig. 30).

There is abundant period evidence that carving shops used patterns and procedures to produce visually similar objects, particularly for large sets and suites that mandated the work of several hands. However, the efforts of craftsmen involved did not entail adopting another’s working style, which would have been required for literal copying. This is clearly seen in the celebrated suite of furniture made for the Philadelphia townhouse of John and Elizabeth (Lloyd) Cadwalader. The genesis of the suite was an elaborate set of commode-front side chairs, probably purchased in 1769 or 1770. One is depicted in Charles Willson Peale’s portrait of Cadwalader’s brother Lambert, likely completed before September 1, 1770 (fig. 31). The chair illustrated in figure 32 is marked “I” on the underside of the shoe and may be the example in Lambert’s portrait. The carving on the back and seat rails is more detailed and rendered more precisely than that on the other surviving chairs, which suggests that it may have been submitted for approval before work began on the remainder of the set. During the fall of 1769 Lambert acted as John and Elizabeth’s agent while the couple cared for her ailing father in Maryland. In September of that year John reimbursed Lambert £94.15 for “B. Randolph[s] acct for Furniture” and £30 for “2 marble Slabs etc. had of C. Coxe.” Although it is impossible to attribute the chairs to Philadelphia cabinetmaker Randolph’s shop based solely on that entry, £94.15 would have been sufficient for a large set.[11]

Several pieces of furniture made by Thomas Affleck and carved by James Reynolds and the firm Bernard and Jugiez were designed to be en suite with the aforementioned chairs. Between October 13, 1770, and January 14, 1771, Affleck’s shop made over eighteen pieces of furniture, including two mahogany commode sofas “for the Recesses” valued at £16, “one Large ditto” valued at £10, “an Easy Chair to Sute ditto” valued at £4.10, and two commode card tables valued at £10. Although all of these examples probably had corresponding rail, knee, and foot carving, only the easy chair and card tables are known to survive (figs. 33–35). The ornament on the easy chair is attributed to Bernard and Jugiez based on similarities to architectural carving documented to their firm (see figs. 36, 37), whereas the carving on the card tables relates to that on pier glasses documented and attributed to Reynolds’s shop, including a surviving example made for the Cadwaladers (see figs. 38–40). Although the carving on the card tables was almost certainly laid out with the same, or identical, patterns, the feet of the tables are different and variations in the outlining cuts and modeling of the leafage indicate the involvement of two hands (figs. 41, 42). To the eighteenth-century eye, a measure of disparity was acceptable, even in the production of pairs and sets.[12]

Consumers like the Cadwaladers did not presume that similar forms would be identical in every detail, but they did expect those objects to be uniform and, in some instances, echo details in their architectural settings. While acting as subcontractors for Affleck, Reynolds and Bernard and Jugiez worked directly for the Cadwaladers. In October 1770 Bernard and Jugiez billed John £28.10.7 1/2 for architectural carving, and in December Reynolds charged him £140.18.1 for several large carved and gilt looking glasses, three half-length picture frames “in Burnish gold,” and 539 yards of papier-mâché borders described as “Palmyra Scrowl” and “Leaf & Reed.” Although the Cadwaladers’ townhouse does not survive, it is easy to imagine how details in the furniture and architectural carving might have resonated.[13]

Reynolds’s picture frames, which cost £18 each, were for Charles Willson Peale’s portraits of Lambert (fig. 31), Thomas, and Hannah Cadwalader. Entries in John’s Waste Book note payments of £50 to “Mr. Peal in part for Paintg” in August 1770 and £60 for “2 miniatures & 3 portrait Paintings in full” the following month. In the summer of 1771 Peale painted two additional portraits: a family group depicting John, Elizabeth, and their daughter Anne; and a likeness of John’s sister Martha (fig. 43). The frames on these portraits have been attributed to Hercules Courtenay and described as “exact copies” of those furnished by Reynolds (see figs. 31, 43). Scholars advancing that attribution have cited an entry in the accounts of John Cadwalader’s secretary, William Gouge, noting payment to Courtenay in full “for 2 Picture Frames @£14” each on March 22, 1774.[14]

The inference that Courtenay copied Reynolds’s frames can be challenged on several points. The three-year gap between the completion of the second group of portraits and Gouge’s payment to Courtenay suggests that the latter’s frames were for two other paintings—possibly the British “pieces” mentioned in Peale’s letter of March 22, 1771. Cadwalader had commissioned the artist to paint landscapes the year before, but Peale failed to do so: “I hope you will pardon my neglect . . . for really too much difidence prevented my attempts after nature had lost her green mantle, the pieces you get from England I hope will be very clever.” Landscapes were often displayed in overmantle architraves, so it would have been desirable and consistent with eighteenth-century furnishing practices to have their frames resemble the adjacent architectural carving. On September 17, 1770, Courtenay charged Cadwalader £81.2.11 for “27 Books of Gold laid on Cornice” and carving that included components—moldings, trusses, a tablet, frieze appliques, and a “Lyons Head”—for chimneypieces in his patron’s townhouse.[15]

The cost of the frames mentioned in Gouge’s accounts also argues against their having been “exact copies,” as they were £4 less than those furnished by Reynolds. To replicate Reynolds’s work precisely, Courtenay would have needed to make a pattern (or, more likely, patterns) of one of the “original” frames and meticulously duplicate his competitor’s outlining, modeling, and shading cuts using similar tools. In short, it would have taken Courtenay considerably more time to mimic Reynolds’s carving than to work in his own style. If Cadwalader wanted the frames for his family portrait and that of his sister to match those furnished by Reynolds, the most expedient and cost-effective solution would have been to order them from that carver’s shop. Cadwalader’s subsequent patronage of Reynolds indicates that their business relationship was sound.[16]

Lastly, the carving on the frame of Martha Cadwalader’s portrait looks nothing like that associated with Courtenay (see figs. 3, 5), whose work and career are the subject of an article in the 2016 volume of American Furniture. The ornament is much more akin to carving documented and attributed to Reynold’s shop. as the pier glass and the card tables suggest (figs. 34. 35, 39–42). Indeed the variations in cutting, moldeling, and shading of the leafage on the frames of Martha and Lamert’s portraits are consistent with those observed on the card tables (figs. 38–42, 44–47). Like most craftsmen of his stature, Reynold’s took apprentices and almost certainly employed journeymen. He also appears to have been associated with Richard Watson, a London carver who immigrated to Philadelphia before 1774, when the latter’s name appeared on the Provincial Tax List. Reynolds witnessed Watson’s will, probated on April 27, 1775. William Macpherson Hornor alluded to a business connection between the two men in his Blue Book: Philadelphia Furniture (1935). Although he did not cite his source, Hornor noted that Watson made “1 Pair Mahoganey brackets” and “1 Pair Paint’d Do.”[17]

In the fine arts of the eighteenth century, the production of exact replicas was an act of respect and admiration, primarily by the patron but also occasionally by the copier. It was not until the nineteenth century that notions of proprietary authorship and plagiarism began to emerge, even in the field of writing. For craftsmen like Martin Jugiez, whose bust of Benjamin Franklin was based on a plaster cast by Jean-Jacques Caffieri, copying was less about paying homage to an acclaimed artist or work than producing an object that was similar enough to satisfy his patron’s expectations. Arguably America’s first sculptor, Jugiez had the ability to copy Caffieri’s likeness in every detail, but as variations in the sculpting of the eyes and modeling of the hair indicate, he chose not to do so (fig. 48). For his patron, and for many like him, close was good enough.[18]

John Trumbull, “Sketch of the Life of John Trumbull, Written by Himself, 1835,” in Autobiography, Reminiscences and Letters of John Trumbull, from 1756 to 1841 (New York & -London: Wiley and Putnam, 1841), p. 13, . Luke Beckerdite and Alan Miller, “A Philadelphia-Carved Bust of Benjamin Franklin,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England, 2016), pp. 2–22.

Jacob Simon, “Thomas Johnson’s The Life of the Author,” Furniture History 39 (2003): 3. Luke Beckerdite, “Thomas Johnson, Hercules Courtenay, and the Dissemination of London Rococo Design,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2016), p. 24.

Beckerdite, “Thomas Johnson, Hercules Courtenay, and the Dissemination of London Rococo Design,” pp. 55–59. Martha Willoughby, “The Deshler Family Chippendale Carved Mahogany Card Table,” in Christie’s, Philadelphia Splendor: The Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Max R. Zatiz, New York, January 22, 2016, lot 172, <https://www.christies.com/lotfinder/Lot/the-deshler-family-chippendale-carved-mahogany-card-5970199-details.aspx>.

Charles F. Hummel, A Winterthur Guide to American Chippendale Furniture (New York: Crown Publishers for the Winterthur Museum, 1976), p. 91.

For the Phillips chair, see Walter Meir Whitehill et. al., Paul Revere’s Boston: 1735:–1818 (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1975), p. 50. Luke Beckerdite, “Carving Practices in Eighteenth-Century Boston,” in Old-Time New England: Essays in Memory of Benno Forman, edited by Brock Jobe (Boston: Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, 1987), pp. 123–39.

Beckerdite, “Carving Practices,” pp. 132–33.

Morrison H. Heckscher, “Copley’s Picture Frames,” in Carrie Rebora Barratt, et al., John Singleton Copley in America (New York: Harry Abrams for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1995), pp. 146–47.

Between August and October 1770, Powel paid Courtenay £60 for carving in his “dwelling house” (Samuel Powel Ledger, 1760–1793, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia).

Robert Campbell, The London Tradesman (1747, reprinted; Devon, Eng.: Latimer & Trend Company for David & Charles, Ltd., 1969), p. 172.

Simon, “Thomas Johnson’s The Life of the Author,” pp. 7–8. Beckerdite, “Thomas Johnson, Hercules Courtenay, and the Dissemination of London Rococo Design,” p. 29. Campbell, London Tradesman, pp. 138–39. Simon, “Thomas Johnson’s The Life of the Author,” p. 47.

John Cadwalader Waste Book, p. 53, box 8, Series 2: General John Cadwalader Papers (hereafter cited GJCP), Cadwalader Family Papers, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Nicholas B. Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur in Philadelphia: The House and Furniture of General John Cadwalader (Philadelphia: Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1964), p. 22. For more on these chairs, see Leroy Graves and Luke Beckerdite, “New Insights on John Cadwalader’s Commode-Seat Side Chairs,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2000), pp. 132–68. See also Samuel W. Woodhouse Jr., “Benjamin Randolph of Philadelphia,” Antiques 11, no. 5, (May 1927): 366–71; Samuel W. Woodhouse Jr., “More About Benjamin Randolph,” Antiques 17, no. 1 (January 1930): 21–25; Philadelphia: Three Centuries of American Art (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1976), pp. 113–15; Philip D. Zimmerman, “A Methodological Study in the Identification of Some Important Philadelphia Chippendale Furniture,” in American Furniture and Its Makers, edited by Ian M. G. Quimby (Chicago: University of Chicago Press for the Winterthur Museum, 1978), pp. 193–208; and, Mark J. Anderson, Gregory J. Landrey, and Philip D. Zimmerman, Cadwalader Study (Winterthur, Del.: Winterthur Museum), pp. 8–13.

Thomas Affleck to John Cadwalader, April 18, 1771, box 2, folder 18, GJCP.Affleck’s bill includes eighteen pieces of furniture, two knife trays, bed and window cornices, and services from October 13, 1770, to January 14, 1771. Notations at the bottom of the bill indicate that Affleck subcontracted the carving on these pieces to James Reynolds and Bernard and Jugiez. Affleck’s bill, which totaled £119.8, is reproduced in Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur, p. 44.

Bernard and Jugiez’s receipted bill, dated February 13, 1771, is in box 2, folder 18, GJCP. Reynolds’s receipted bill, dated June 29, 1771, is in box 2, folder 20, GJCP. The bills from both carving firms are reproduced in Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur, pp. 29, 46.

Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur, p. 45. John Cadwalader Waste Book, p. 53, box 8, GJCP. The payment to Peale was for “2 minature & 3 portrait Paintings in full.” For more on the sitters, see Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur, pp. 108–11, 114–15.

For the Peale quote and Cadwalader’s ordering English landscapes, see Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur, p. 47. Incoming Correspondence, Bills, and Receipts, 1770, box 2, folder 17, GJCP; reproduced in Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur, p. 12.

On November 25, 1771, Reynolds received £14 for a looking glass “in a Carv’d white frame” (£11.15.0), “putting up [papier-mâché] Borders in the Chamber” (£1.10), and two pounds of brass nails used to install those borders (15s.) (Incoming Correspondence, Bills, and Receipts, 1771–1772, box 3, folder 14, GJCP; reproduced in Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur, p. 124.

<http://files.usgwarchives.net/pa/philadelphia/taxlist/northward1774.txt>. Will of Richard Watson, probated April 27, 1775, Philadelphia Wills, 1775, no. 115, p. 134, City Hall, Philadelphia. William Macpherson Hornor, Blue Book: Philadelphia Furniture, William Penn to George Washington (Philadelphia: by the author, 1935), p. 284.

Beckerdite and Miller, “A Philadelphia-Carved Bust of Benjamin Franklin,” pp. 9–12.