Detail of J. Stevens, A View of the Landing the New England Forces in ye Expedition against Cape Breton, printed by John Bowles, London. 14" x 19 1/4". Colored line engraving. This engraving shows a ship with carved ornaments of the type produced by Anthony and Brian Wilkinson. (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

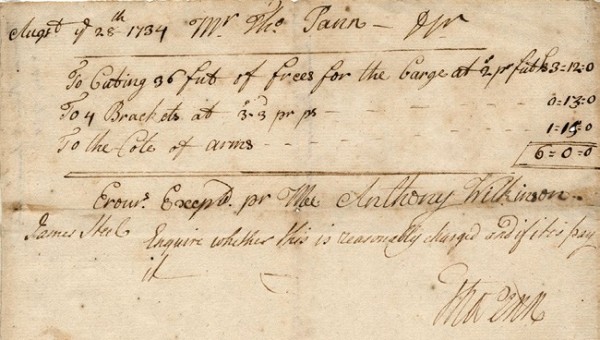

Anthony Wilkinson’s bill for ship carving for Thomas Penn’s barge, Philadelphia, August 28, 1734. (Courtesy, RAAB Collection)

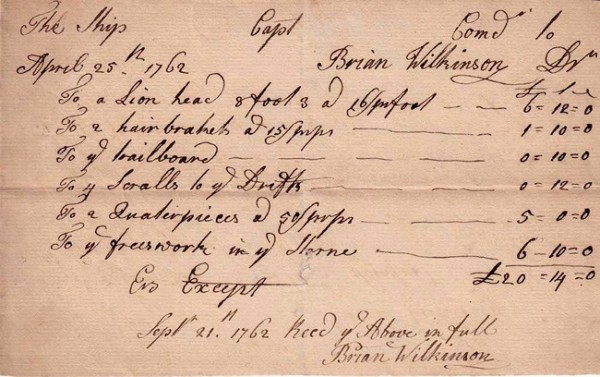

Brian Wilkinson’s bill for carving for the ship Delaware, Philadelphia, April 25, 1762. (Courtesy, Ten Pound Island Book Company).

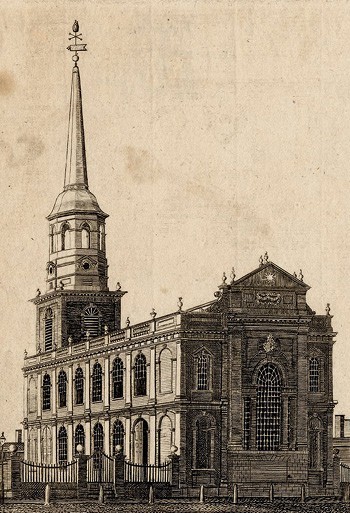

James Peller Malcolm, Christ Church, Philadelphia, 1814. 12 1/4" x 14 1/4". (Courtesy, Arader Galleries).

Truss on the steeple of Christ Church, attributed to the shop of Samuel Harding, Philadelphia, 1753.

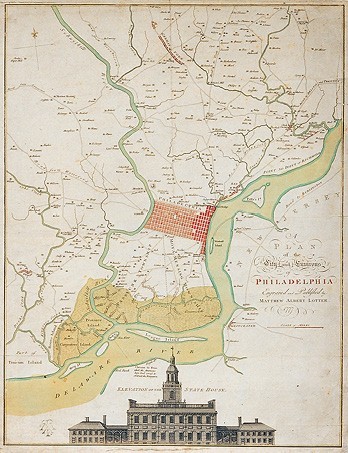

Elevation of the North façade of the Pennsylvania State House shown on Matther A. Lotter’s A PLAN of the City and Environs of PHILADELPHIA, Pennsylvania, 1777. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Samuel Harding, bill for carving for the Pennsylvania State House done between January 29, 1775 and January 7, 1757. A transcription of this bill is in the research files, Independence National Historical Park. The citation on the transcription is shown above.

First floor, central hall in the Pennsylvania State House. (Courtesy, Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress; photo, Jack E. Boucher, 1959).

Door pediment in the first floor, central hall in the Pennsylvania State House. (Courtesy, Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress; photo, Jack E. Boucher, 1959).

Pediment and upper section of an architrave on the north wall of the first floor, central hall in the Pennsylvania State House. (Courtesy, Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress; photo, Jack E. Boucher, 1959).

Keystone of a pedimented architrave in the first floor, central hall of the Pennsylvania State House. (Courtesy, Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress; photo, Jack E. Boucher, 1959).

Frontal view of a truss on the steeple of Christ Church.

Indian head, door pediment in the first floor, central hall of the Pennsylvania State House. (Courtesy, Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress; photo, Jack E. Boucher, 1959).

Brackets and balusters in the stair tower of the Pennsylvania State House. (Courtesy, Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress; photo, Jack E. Boucher, 1959).

Frieze of a landing in the stair tower of the Pennsylvania State House. (Courtesy, Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress; photo, Jack E. Boucher, 1959).

Venetian window and flanking pilasters and architraves in the stair tower of the Pennsylvania State House. (Courtesy, Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress; photo, Jack E. Boucher, 1959).

Frieze applique on one of the pedimented architraves flanking the Venetian window of the stair tower of the Pennsylvania State House. (Courtesy, Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress; photo, Jack E. Boucher, 1959).

Side view of an upper truss on one of the architraves in the stair tower of the Pennsylvania State House. (Courtesy, Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress; photo, Jack E. Boucher, 1959).

Lower truss on one of the architraves in the stair tower of the Pennsylvania State House. (Courtesy, Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress; photo, Jack E. Boucher, 1959).

Pilaster capital and drops framing one of the architraves in the stair tower of the Pennsylvania State House. (Courtesy, Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress; photo, Jack E. Boucher, 1959).

Exterior clock on the Pennsylvania State House.

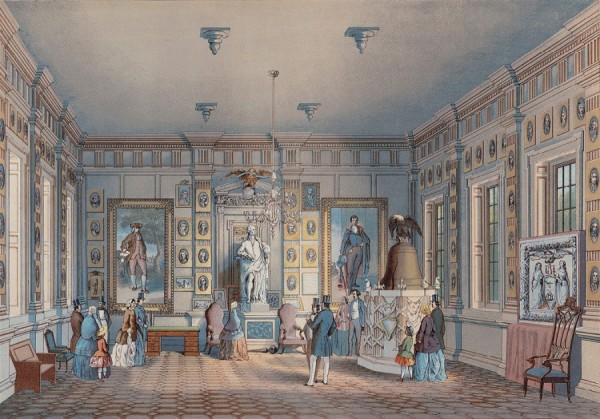

Max Rosenthall, Interior View of Independence Hall, Philadelphia, 1856. (Courtesy the Library Company of Philadelphia.)

Frieze applique in the Assembly Room of the Pennsylvania State House attributed to the shop of Brian Wilkinson, Philadelphia, 1750–1755. (Courtesy, Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress; photo, Jack E. Boucher, 1959).

Detail of the applique illustrated in fig. 23.

Detail of the applique illustrated in fig. 23.

Franklin stove attributed to Warwick or Mount Pleasant Furnace, Chester or Berks County, Pennsylvania, c. 1742–1748. Cast iron. H. 31 1/2", W. 27 1/2", D. 35 3/4". (Courtesy, Mercer Museum of the Doylestown Historical Society; photo, Philadelphia Museum of Art.)

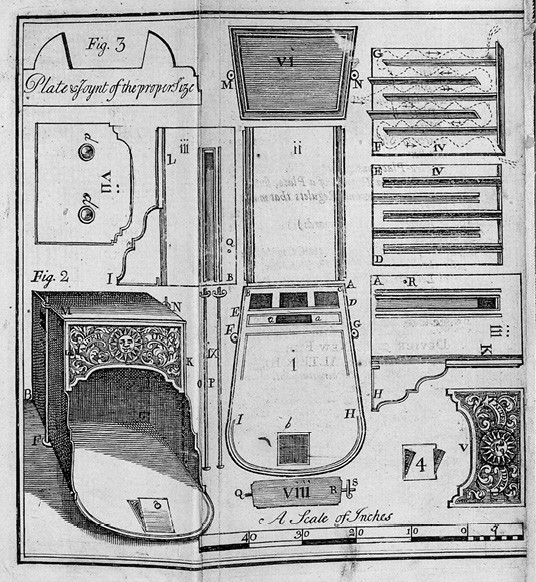

James Turner (w. 1744–1759) after Lewis Evans, design for Franklin’s Stove, illustrated in An Account of the New Invented Pennsylvanian Fire-places. (Courtesy, Library Company of Philadelphia.)

Detail of the front plate of the stove illustrated in fig. 26.

Tall case clock with movement by Peter Stretch and carving attributed to the Wilkinson shops, Philadelphia, 1735–1745. Mahogany with tulip poplar, and yellow pine. H. 110", W. 18 1/2", D. 9". Courtesy, Winterthur Museum: purchase with funds provided by the Henry Francis du Pont Collectors Circle, Winterthur Centenary Fund, Mrs. C. Lalor Burdick, Mr. and Mrs. Richard Chilton, Mrs. Robert N. Downs III, Mr. William K.

du Pont, Mr. and Mrs. Frederick C. Fiechter III, Mr. and Mrs. John A. Herdeg, the Hohmann Foundation, Family of Mr and Mrs. Walter M. Jeffords, Jr., Kaufman Americana Foundation, Mrs. George M. Kaufman, Mr. and Mrs. Barron V. Kidd, Charles Pollak, Peter A. Pollak, Suzanne W. Pollak, Mr. and Mrs. P. Coleman Townsend, and anonymous donors and friends.

Detail showing the hood of the tall case clock illustrated in fig. 29.

Detail showing the carving on the hood of the tall case clock illustrated in fig. 29.

Chimney back, Oxford Furnace, Warren County, New Jersey, 1747. Cast iron. 32 1/4" x 29 1/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Tea table with carving attributed to the shop of Brian Wilkinson, Philadelphia, 1745–1755. Mahogany with yellow pine H. 26 1/2", W. 31 1/2", D. 21 1/2". (Courtesy, Library Company of Philadelphia.)

Detail showing the carving on one of the long rails of the tea table illustrated in fig. 33.

Detail showing the carving on a leg of the tea table illustrated in fig. 33.

Tea table with carving attributed to the shop of Brian Wilkinson, Philadelphia, 1745–1755. H. 29", Diam. of top: 30" (Private collection; photo, Joseph P. Gromacki.)

Detail of the carving on a leg of the tea table illustrated in fig. 36.

Tea table, with carving attributed to the shop of Brian Wilkinson,Philadelphia, 1745–1755. Mahogany with white cedar. H. 27 1/2", W. 34 5/8", D. 21 1/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Detail showing the carving on a long rail and leg of the tea table illustrated in fig. 38.

Pier table, England, c., 1740. H. 31 13/16", W. 35 5/8", D. 24 1/2". Mahogany with mahogany veneer and larch. (Courtesy, Drayton Hall.)

Desk-and‑bookcase, London, c. 1735. H. 93 3/4", W. 51 1/8", D. 23 5/8". Oak and rosewood with unidentified conifer. (Courtesy, Mackinnon Fine Furniture.

Pier table with carving attributed to the shop of Brian Wilkinson, Philadelphia, c. 1750. Mahogany with yellow pine and white cedar; clouded limestone. H. 31", W. 42", D. 24 5/8". (Private collection; photo, Levy Gallery.)

Detail of the carving on the front rail of the pier table illustrated in fig. 42

Detail of the carving on the front rail and a leg of the pier table illustrated in fig. 42.

Top of the pier table illustrated in fig. 42.

Details showing holes for and remnants of the indexing pins of the pier table illustrated in fig. 42.

Detail showing the back edge of the top of the pier table illustrated in fig. 42

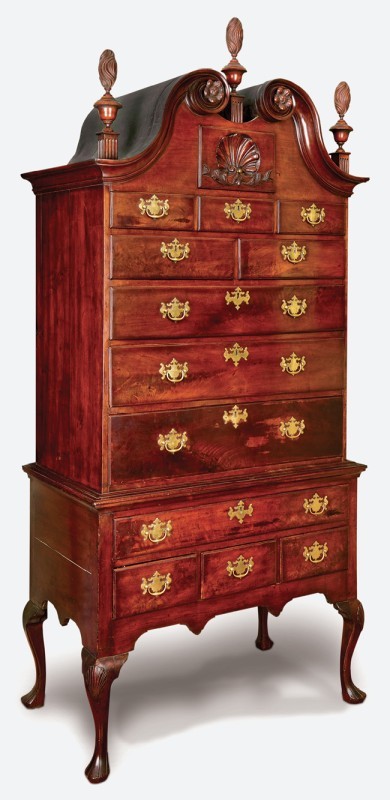

Chest-on-chest attributed to George Claypoole Sr. or Jr. with carving attributed to the shop of Brian Wilkinson, Philadelphia, c. 1750. Mahogany with tulip poplar, and white cedar. H. 85 1/2", W. 43 1/2", D. 22 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Sotheby’s.)

Detail showing the carving on the upper center drawer of the chest-on-chest illustrated in fig. 48.

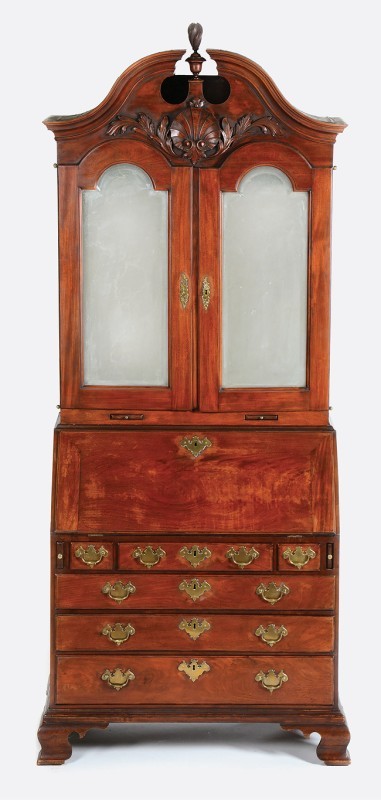

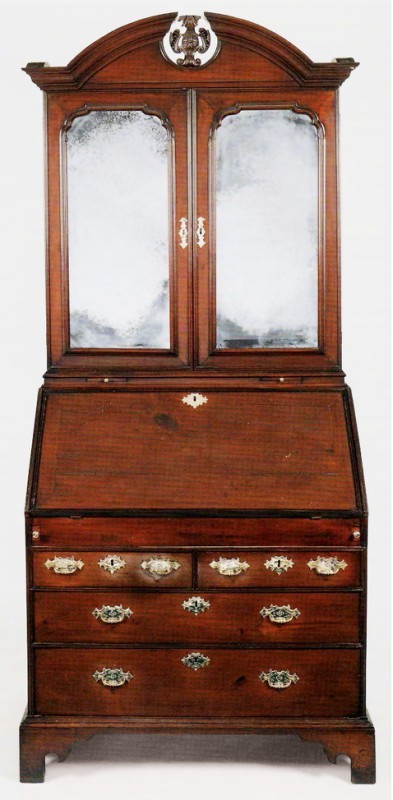

Desk-and-bookcase with carving attributed to the shop of Brian Wilkinson, Philadelphia, c. 1750. Mahogany with unrecorded secondary woods. H. 84", W. 42", D. 25". (Private collection; photo, Morphy’s.)

Detail of the applique on the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 50.

Chimney back, Oxford Furnace, Warren County, New Jersey, 1746. Cast iron. 34 1/4" x 34". (Private collection; photo, Vine Cassaro.)

Detail of the chimney back illustrated in fig. 52.

Frontal view of an upper truss on one of the architraves in the stair tower of the Pennsylvania State House. (Courtesy, Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress; photo, Jack E. Boucher, 1959).

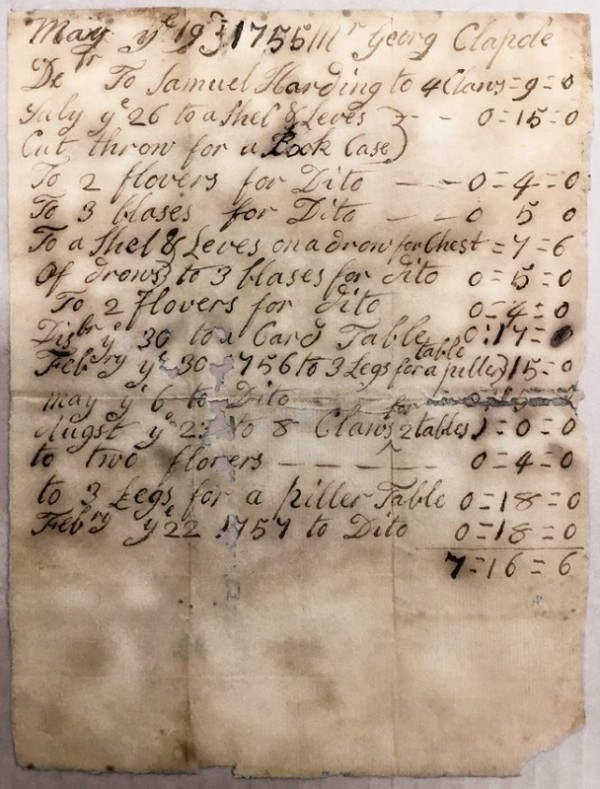

Samuel Harding bill to George Claypoole Sr. or Jr. for carving done between May 19, 1755 and February 22, 1757. (Courtesy, Marion Carson Papers, Library of Congress; photo, Don Fennimore.)

Desk-and-bookcase with carving attributed to the shop of Samuel Harding, Philadelphia, c. 1755. Walnut with tulip poplar, yellow pine, and white cedar. H. 100", W. 40 3/4", D. 23 3/4". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing the pediment of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 56. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Desk-and-bookcase with carving attributed to the shop of Samuel Harding, Philadelphia, c. 1755. Mahogany with tulip poplar, yellow pine, and white cedar. H. 104", W. 41", D. 24". (Private collection; photo, Robb Quinn.)

Detail showing the pediment of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 59.

Desk-and-bookcase with carving attributed to the shop of Samuel Harding, Philadelphia, c. 1755. Mahogany with tulip poplar, yellow pine, and white cedar. H. 105", W. 41 1/8", D. 24 3/4". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art; gift of Daniel Blain, Jr.)

Detail showing the pediment of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 60.

Tall clock case with movement by John Wood Sr. or Jr. and carving attributed to the shop of Samuel Harding, Philadelphia, c. 1755. Walnut with tulip poplar. H. 107 1/2", W. 23 1/2", D. 11 3/8". (Courtesy, © Metropolitan Museum of Art; bequest of W. Gedney Beatty, 1941.)

Detail showing the pediment of the tall case clock illustrated in fig. 62.

High chest of drawers with carving attributed to the shop of Samuel Harding, Philadelphia, c. 1755. Mahogany with white cedar, tulip poplar, and pine. H. 93", W. 40", D. 20". (Courtesy, James Kilvington Antiques.)

Detail showing the carving on the upper center drawer of the high chest illustrated in fig. 64.

Chimneypiece in Woodford Mansion, Philadelphia, c. 1755. (Courtesy, Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress; photo, Jack E. Boucher.)

Details showing carved linen-fold shells attributed to the shops of Brian Wilkinson (left), fig. 23, and Samuel Harding (right), fig. 56.

Details showing flat shells attributed

to the shops of Brian Wilkinson (left), fig. 50,

and Samuel Harding (right), fig. 60.

Details showing leafage on furniture appliques attributed to the shops of Brian Wilkinson (left), fig. 50, and Samuel Harding (right), fig. 56.

Details showing leafage on architectural appliques attributed to the shops of Brian Wilkinson (top) and Samuel Harding (bottom).

Desk-and-bookcase, Philadelphia, 1735–1745. Mahogany with tulip poplar and yellow pine. H. 89", W. 41 1/8", D. 24". (Private collection.) The shield ornament on this desk-and-bookcase is the earliest Philadelphia example known. Given the probable date of this object, Anthony Wilkinson is a likely candidate for its carver.

High chest of drawers, Philadelphia, 1745–1755. Walnut and walnut veneer with tulip poplar, white cedar, and yellow pine. H. 85 5/8", W. 43", D. 24". (Private collection; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.) The carving on this chest is stylistically related to that from the Wilkinson and Harding shops, but the leafage is crude by comparison.

Dressing table, Philadelphia, c. 1750. Mahogany with white cedar, tulip poplar, and yellow pine. H. 31", W. 33 1/2", D. 21". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This dressing table is one of the most fully developed examples of its era. As the details shown in figs. 5 and 6 reveal, the leaf carving on the knees is superior to that on the drawers and most closely resembles work associated with the Wilkinson shops.

Detail of the carving on the drawer of the dressing table illustrated in fig. 4. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the carving on a leg of the dressing table illustrated in fig. 4. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, Philadelphia, c. 1750. Walnut. H. 41 1/2". (Courtesy, Christie’s)

Side chair, Philadelphia, c. 1750. Walnut. H. 42 1/2". (Courtesy, Christie’s)

Detail showing the knee carving on the side chair illustrated in fig. 8.

BRIAN (BRYAN) WILKINSON and Samuel Harding have long been associated with Philadelphia carving from the mid-eighteenth-century. Although references to these men can be found in various publications on that city’s architecture and decorative art, their careers and work have not been thoroughly explored. This article will address that shortcoming by presenting new biographies of both craftsmen and by using their documented work to attribute other examples of architectural and furniture carving to their shops. Because Brian likely trained in the shop of his father Anthony, the elder Wilkinson will also be included in this study.

Anthony Wilkinson

Anthony Wilkinson was born in Philadelphia in 1698. Although his mother has not been identified, his father Gabriel, a baker, was present in the city by 1686. The earliest reference to Anthony working in the carving trade is in a 1724 deed, wherein his father conveyed part of a lot that extended from Front Street to Water Street to him. Many tradesmen involved in the shipbuilding industry were located nearby. On January 6, 1729, Quaker merchant John Reynell (Reynel, Reynolds) paid Wilkinson £4.6.6 for carving a “Lyon [figurehead] &c.” for the ship Torrington, a fifty-ton vessel built by Philadelphia shipwright Aaron Goforth. Anthony carved ornaments for several ships during the 1730s and 1740s (fig. 1). He charged £4.4 for a six-foot lion figurehead for the ship Tryal in July 1730; £3.12 for 36 feet of frieze, 13s. for four brackets, and £1.15 for a coat of arms for Thomas Penn’s barge in 1734 (fig. 2); and £19 for unspecified work for the ship Mary in 1742.[1]

There are few clues as to the size and composition of Wilkinson’s shop, but presumably he took apprentices and employed journeymen. Although there is no record of Brian Wilkinson’s apprenticeship, it is likely that he trained in his father’s shop. The only reference to a journeyman working there is Anthony’s June 27, 1734 advertisement in the Pennsylvania Gazette, offering a £3 reward for John Nicholson, a runaway servant carver “about 27 Years of Age.” Wilkinson noted that Nicholson “pretends to be a Chair carver, and can speak a little Indian, having lived a Twelve month among those People.” Although there is no conclusive evidence that Anthony’s shop produced furniture carving, it would not have been unusual for

the period. Moreover, the Wilkinsons were connected to at least one family of Philadelphia joiners through the marriage of Anthony’s niece Mary to Joseph Claypoole. Joseph’s father George was one of the most prolific cabinetmakers in the city, with a career that extended from the mid-1730s into the early 1780s.[2]

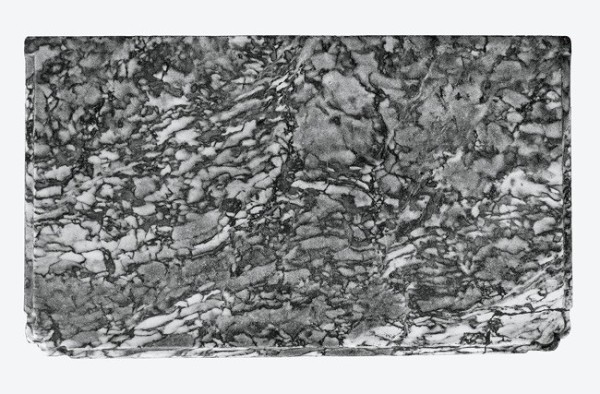

In addition to carving, Wilkinson worked as a mason and stone -cutter. On November 2, 1727, he offered four shillings reward for a runaway stonecutter named Richard Peckford, and on March 8, 1734, Philadelphia joiner John Head credited Wilkinson £1.11.16 for a “marvel harth.” Head’s hearth was probably made of Pennsylvania clouded limestone, commonly referred to today as “King of Prussia marble.” As decorative arts scholar R. Curt Chinnici noted, the earliest quarries were located near Harmanville in Whitemarsh Township and are mentioned in a deed for 150 acres of land David Henry sold Thomas Coldee in 1714. Wilkinson purchased 85 acres of that tract from Coldee in 1731 and acquired the remaining 65 acres by 1739. The former may have furnished stone for his Philadelphia neighbor, William Holland, who described himself as a mason “lately from London” and advertised “Chimney Pieces, Grave Stones, Mortars, Tables, Monuments and Steps, Pavements of all Kinds, [and] Hearths.” While in New York in 1739, Holland directed all “Gentlemen and others [requiring his services], to apply to Mr. Anthony Wilkinson, Ship Carver in Philadelphia, until he return.” Wilkinson continued to advertise masonry work and ship carving, and in 1741 he reported finding “a vein of [stone] much better than has been formerly us’d.” His son Brian later described the stone from his father’s quarry as “perhaps . . . the best yet discovered in America.”[3]

Wilkinson was referred to as a “stone cutter” more often than a “ship carver” from the mid-1750s until his death, suggesting that most of his business was in the former trade. He was held in high esteem by Benjamin Franklin, who in January 1758 wrote:

I find Marble Work in great Vogue here, and done in great Perfection at present. I think it would much improve Cousin Josey, if he was to come over and work in some of the best Shops for a Year or two. If he can be spar’d without Prejudice to Cousin Wilkinson, to whom my Love, send him to me by the first Ships, and I will get him into Employ here: As he seems an ingenious sober Lad, it must certainly be a great Advantage to him in his Business hereafter, when he returns to follow it in America.

Wilkinson died in 1765 and was buried at Christ Church in Philadelphia in February of that year. On July 17, 1766, the Pennsylvania Gazette reported:

To be SOLD or LETT . . . several Lots of Ground in the Northern Liberties, on Second and Green-streets, opposite the Barricks; a Plan of which may be seen, and Terms known, by Applying to Brian Wilkinson, the upper End of Water-street. Also to be Lett by the Year, or for a Term of Years, the Wharff and Stores where said Wilkinson Lives. A Mason or Stone-cutter, that understands working in Marble, may meet with Encouragement, by applying to said Wilkinson, he being possessed of the Marble Quarry, late his Father, Anthony Wilkinson’s.[4]

Brian Wilkinson

Brian Wilkinson was born in Philadelphia in 1718 and married Hester Leech in 1745. The following year he purchased a lot on the east side of Front Street between Sasafrass and Vine Streets that became the location of his shop. If Brian trained with his father, as seems likely, and completed his apprenticeship at the customary age of 21, he may have worked as a journeyman in Anthony’s shop from the late 1730s until the mid-1740s. That was the period when Anthony consolidated his quarrying business and turned his attention increasingly to masonry and stone cutting.[5]

In the December 1, 1748 issue of the Pennsylvania Gazette, Brian advertised twenty-one months remaining on the indenture of “a servant [man] . . . a carver by trade.” Subsequent advertisements by him were largely for runaways. On April 5, 1749, he offered fifteen shillings reward for the return of an “Irish servant man, named William Mooney, a little fellow, about twenty years of age, much mark’d with the smallpox, by trade a carver” and expressed willingness to increase the bounty to “Three Pounds, and reasonable charges” if the runaway was captured outside the Philadelphia environs. Two indentured servants who absconded from Wilkinson’s shop were described as “Dutch”: Lawrence Perkley, “by trade a Carver in wood and stone,” was “40 years of age” and reputedly spoke no English, although Wilkinson acknowledged that he was fluent in “several other languages, such as French and Turkish”; the trade of “Matthew or Matthias Luyker” was not specified, but he was only sixteen and may have been an apprentice. The same may have been true of London-born John Forder, a seventeen-year-old who ran away from Wilkinson in May 1750. Wilkinson had at least one enslaved craftsman working in his shop. In the July 9, 1752 issue of the Pennsylvania Gazette, he offered a reward for “A Negro Man, named Charles, about 21 years of age . . . used to the carving business.”[6]

Documentation regarding Wilkinson’s work is scarce. On August 20, 1756, he submitted an account for “carved Work, done for the State-House” totaling £85.8.10. Wilkinson received £35 the following January but did not collect the remainder until September 1769. Like his father, Brian carved ornaments for ships. On April 25, 1762, he charged £20.14.10 for a “Lyon head” [figurehead], two pairs of brackets, frieze work, a tailboard, four scrolls, “quarterpieces,” and frieze work for the ship Delaware (fig. 3).[7]

In February 1765, Brian and his brothers-in-law Peter Knight and John Knowles assumed management of Anthony Wilkinson’s estate, which included the latter’s masonry and stone cutting business. When the Orphan’s Court approved land distributions among Anthony’s heirs the following spring, Brian received 75 acres that included his father’s marble quarry. Brian had earlier begun to acquire land in Whitemarsh Township north of that tract. Although Brian advertised for a craftsman who “understands working in Marble” in 1766, he was described as a “stone cutter” in a deed in 1770 and a tax list in 1772. On December 19, 1774, the Pennsylvania Packet reported:

Brian Wilkinson and son . . . carry on the Marble Stone cutting business, in all its branches, at their shop in Water St. . . . where may be had chimneypieces of all kinds and grave stones neatly lettered, as cheap as any on the Continent of America; They having the best marble quarry of their own.

Brian subsequently moved from Philadelphia to Oxford Township, where he continued to be described as a stone cutter and carver. He died in 1794 and was buried at Christ Church in Philadelphia, as were his father and grandfather.[8]

Samuel Harding

Aside from surviving bills and records of payment for work, little is known about Samuel Harding’s life and career. The earliest reference to him is in the cash book of Governor James Hamilton, who, on June 11, 1751, paid Harding for unspecified carving in Bush Hill. Hamilton inherited that house from his father Andrew and began remodeling it during the 1740s. The builder responsible for that project was Robert Smith, who was born in Dalkeith Parish, Midlothian, Scotland and immigrated to Philadelphia in late 1748. James Hamilton’s accounts document substantial construction in that year. In March 1750, the Reverend Peter Richards wrote “the Governor has made a double house of Bush Hill & removes his family into it in October next.” Although work at Bush Hill was largely completed by the summer of 1751, when Hamilton made his final payment to Smith, a February 2, 1753 entry in James’ cash book records payment to Harding for “Carving a Shield.”

Hamilton and Smith must have been pleased with Harding’s work at Bush Hill, since the latter was commissioned to provide carving for the steeple of Christ Church, a construction project underwritten in part by Hamilton and supervised by Smith (fig. 4). Work on the steeple probably began in late 1751 or early 1752 and appears to have been completed in 1754. Harding received £12 for carving eight trusses with masks, or “faces” in 1753 (fig. 5).

Harding’s most important commission extended from January 29, 1753 to January 7, 1757, when his shop provided carved ornaments valued at £195.13.11 for the Pennsylvania State House (fig. 6). Construction of the State House began many years earlier. Andrew Hamilton, Speaker of the Assembly, “produced a Draught of the State-House, containing the Plan and Elevation of that Building” in 1732, but it is unlikely that substantive work started before 1735, when master builder Edmund Wooley submitted a bill for “drawing the elevation of the Frount one End of the Roof Balconey Chimneys and Torret. . . . With the fronts and Plans of the Two offices And Oiazzas Allso the Plans of the first and Second floors.” The Assembly Room, Hall, and Supreme Court Chamber appear to have been serviceable by the early 1740s, but work on the stair tower, where much of Harding’s carving was installed, and the final outfitting of the second-floor rooms did not begin before January 1749/50 when authorization “to carry up a Building on the South-side . . . to contain the Stair-case, with a suitable Place thereon for hanging a Bell” occurred. During the period of the stair tower’s construction Harding worked under the supervision of Thomas Leech, one of the superintendents of the State House and father of Hester Wilkinson, Brian’s wife.

In addition to architectural carving, Harding’s shop produced ornaments for a variety of furniture forms. He is documented working for George Claypoole between 1755 and 1757 (see fig. 55), and carving attributed to him also occurs on furniture from other, contemporaneous Philadelphia cabinet shops. As furniture scholar Andrew Brunk has shown, Claypoole was active from the late 1730s until the 1780s and enjoyed the patronage of prominent merchants including Edward Shippen, Jr. and John Reynell.[9]

Harding signed his will on June 2, 1758 and probably died before August 23, 1758, when his executor Elizabeth Downey received the final payment for his carving for the State House. His will, proven on September 28, 1758, noted that she was his executor and listed witnesses John Downey (Elizabeth’s husband), Robert Black (cabinetmaker), and Alice Drumbrell.

The Pennsylvania State House

The carving in the Pennsylvania State House is the rosetta stone for attributing work to Samuel Harding and Brian Wilkinson. Harding’s account is unusually descriptive both in terms of the ornament and its architectural context (fig. 7). His shop furnished all of the carving for the exterior of the building and interior of the stair tower. Additional work included four Composite capitals and pilasters for the “green room” (presumably the Assembly Room) and all of the carving in the “passage” or hall except for the Indian heads—possibly representing America, pediment scrolls, and egg-and-dart moldings, trailing husks, and scroll-framed shields on the pediments of the doors at the North and South ends, which are not mentioned in his bill and may have been installed earlier (figs. 8, 9).

Harding’s carving in the passage consisted of “seven leaf grass” and egg and dart moldings, “fishes,” and “flowers” for sixteen capitals in the Doric order, 53 modillions carved with “three leaf grass,” and “two pediments frames [with] . . . kestones . . . With fases (figs. 10, 11).” The pediments surmounted architraves, each with two trusses and three-leaf grass, egg-and-dart, and ribbon-and-flower moldings. The faces on Harding’s keystones are flatter and less sculptural versions of those on the trusses his shop furnished for Christ Church (fig. 12), and their modeling differs significantly from that of the Indian heads over the passage doors (fig. 13).

The most extensive work listed in Harding’s bill was for the stair tower. His shop furnished 146 bannisters, 58 brackets (fig. 14), 4 friezes (fig. 15), 53 modillions, 44 “flowers between ye Mundulyouns,” and two tabernacle frames to flank the “Venneshon Winder” (fig. 16). Each frame had a frieze with a flower and leaf applique (fig. 17), two upper trusses (fig. 18), four flower appliques (one in each ear of the architrave), two “bottom trusses” (figs. 19), and long “draps of husks” on either side (fig. 20). For the Venetian window, Harding provided capitals, charging by the “front.”

Exterior carving supplied by Harding included eight “balcony urns” with “blases” (flames), “flowers” and “fishes” for the door architraves, and a variety of ornaments for the clock on the west side (fig. 21). Harding’s bill was very specific about the location of the major components, which were the, “[k]not & S[w]ags in the pedement,” “6 trusses that Supports ye pediment,”

“12 fishes” above and “6 draps Under ye upper trusses,” the hour and

minute hands “cut thru,” two “angel pieces (leafy husks) at the bottom

of ye dial swe[e]p,” “4 flowers for ye Serfets,” and eight “Cuttuses” (buttresses) with drops between for “ye bottom.” The clock was further ornamented with a variety of moldings: 50 feet of egg-and-dart, 76 feet of “5 Leaf grass,” 66 feet of “3 Leaf grass,” 14 1/2 feet of “riben & flower,” and 18 feet of “flower.”

The account that Brian Wilkinson submitted for architectural carving for the State House has not been located, but the £85.8.10 total indicates that his shop furnished a significant amount of work. Presumably that comprised all of the original carving not listed on Harding’s bill, including the large shell-and-leaf applique on the large architrave in the Assembly Room and the ornaments over the north and south doors in the first-floor hall (figs. 8, 9, and 22–25). His shop almost certainly did other work that no longer survives, which likely including additional components, appliques, and moldings for the architrave. The ones currently installed are comprised of salvaged Philadelphia architectural carving dating circa 1770 (inner architrave and upper portion of trusses below) and twentieth-century elements (pediment trusses, flower appliques in the ears below).

For the State House carving, Wilkinson received £35 in January 1757. A notation made at the time notes that the £50.8.10 remaining due “does not appear, on the Accounts of the Trustees of the Loan Office, to have been paid by them, or any other Person.” It is unclear when or if Brian was paid in full or when his carving was completed and installed. The Assembly Room appears to have been plastered initially and paneled later, although the date when the latter was installed is unknown. Thomas Leech’s order for screens and curtains in 1748, suggests that the Superintendents expected work in the Assembly Room to be completed soon. If so, Wilkinson’s carving there and in the passage may predate the work provided by Harding’s shop.

In addition to being a virtual catalog of Harding’s stylistic vocabulary, the carving in the State House provides insights into work methods and idiosyncrasies useful in identifying his undocumented carving. Harding’s leaf carving, exemplified by that on the stair friezes and appliques over the Venetian windows, is distinctive, typically featuring long, slender lobes terminating in pointed tips, occasionally articulated with short parallel shading cuts. The larger leaflets typically have convex centers with a raised central spine, whereas the smaller leaflets, as well as larger examples that flip over, tend to have concave centers and lobes. As the applique in the Assembly Room reveals, Wilkinson’s leaves are almost invariably convex in the center and typically articulated with fine shading cuts. The tips of his larger leaflets end in points and often have a raised edge suggesting a curl, whereas smaller trailing lobes typically have rounded ends. Like Harding, Wilkinson occasionally shaded the ends of leaves with short parallel gouge cuts made more or less perpendicular to the flow of the design. Although both carvers worked in a similar Anglo-baroque style and sometimes employed like techniques, their work can be separated with adequate scrutiny (see appendix A).

Carving from the Wilkinson Shops

Iron stoves of the type cast at Mount Pleasant Furnace in Berks County, Pennsylvania, and Warwick Furnace in Chester County are potentially the earliest objects linked to the Wilkinson shops, although the precise date when production began is uncertain (fig. 26). A September 23, 1742 entry in a ledger for Coventry Forge, which served Mount Pleasant, recorded a charge of £23.3.2 for “seven small new-fashioned fireplaces.” Two years later, Benjamin Franklin published An Account of the New Invented Pennsylvania Fire-places, which included an engraving of his hearth stove and instructions for its manufacture (fig. 27). That design was clearly the inspiration for the stove illustrated in figure 26, but the carver who produced the pattern for the front plate inverted the banner and incorporated his own style of leafage (fig. 28). The leaves are remarkably similar to those on the Assembly Room applique, particularly in their shape and the manner in which they flip and reverse direction.[10]

A tall case clock with a movement by Peter Stretch and carving attributed to the Wilkinson shops dates 1745 or earlier (figs. 29–31). The movement bears the coat of arms of Philadelphia merchant Clement Plumstead, who died in that year. The leaves on the sarcophagus section were set in relief, modeled, and shaded much like those of the applique in the Assembly Room in the State House. Their exaggerated features and the termines anti quem of the clock raises the possibility that the carving was done in Anthony Wilkinson’s shop. The earliest suggestions that Brian was working independently are his marriage in 1745 and acquisition of property the following year.[11]

A chimney back marked Oxford Furnace and dated 1747 has mantling that also relates closely to the leafage of the Assembly Room applique (fig. 32). Built in 1741 by Jonathan Robeston, an ironmaster from Philadelphia, and his partner and financier merchant, Joseph Shippen, Jr., Oxford was the third furnace established in that colony and the first located near a major source of iron ore. According to an 1881 history of Sussex and Warren Counties, the first pigs were cast by March 9, 1743. Two different chimney backs—both depicting the arms of George II—were cast at Oxford Furnace.[12]

Carving attributable to Brian Wilkinson’s shop occurs on a wide range of furniture forms including tea tables, desk-and-bookcases, high chests, and dressing tables. Two rectangular tea tables have histories of descent in prominent Philadelphia families. The example shown in figure 33 descended in the Dickinson, Logan, and Norris families and, according to William MacPherson Hornor, may have originally belonged to Charles Norris. Among Philadelphia tables, this example is unique in having rails with cyma-shaped faces, mirroring the contours of the rim molding. The center of each long rail is punctuated with a scallop shell and leafage similar to those on the Assembly Room applique (fig. 34). As in other work associated with Wilkinson, the leaflets are modeled so they appear ready to curl at the tips. Each leg of the table has similar shells with graduated husks below and small claw feet with prominent webbing and a center toe with widely spaced upper and middle knuckles (fig. 35). Closely related carving occurs on contemporaneous pillar-and claw tea tables (figs. 36, 37) and dressing tables.[13]

The rectangular tea table illustrated in figure 38 reputedly belonged to Thomas Graeme, a Scottish physician who immigrated to Philadelphia with Sir William Keith and his family in 1717 and subsequently married Keith’s step-daughter Anne Diggs. When Keith returned to England in 1727, he sold part of his estate “Fountain Low” to Graeme. In 1737, Graeme purchased 835 acres that had been placed in trust for Lady Anne Keith, and renamed the estate “Graeme Park.” Although the precise date when Graeme began renovating Keith’s house is unknown, it probably occurred during the late 1740s or early 1750s. Presumably the doctor acquired this table around the same time. The leaves and shells on Graeme’s table have nearly exact counterparts on the Assembly Room applique (figs. 25, 39). Despite this relationship and the table’s white cedar secondary wood, furniture scholar Desmond Fitzgerald attributed it to Ireland. While it is possible that elements of the table’s design were introduced by an Irish craftsman like William Mooney, who worked for Wilkinson in 1749, the style and composition of the carving originated decades earlier. Antecedents can be found in London gessoed and gilded furniture from the 1720–1730 period (figs. 40, 41).[14]

A monumental pier table recently brought to light by furniture scholar Frank Levy shares numerous details with the Graeme table (fig. 38, 42). Both objects have long rails with scallop shells matching the small convex one in the center of the Assembly Room applique as well as baroque strapwork and leafage set in, modeled, and shaded in the same manner (figs. 24, 25, 39, 43, 44). The feet are also distinctive in having flanges between the side and rear toes and long, abruptly sloped center toes.

The top of the pier table is highly-figured, clouded limestone that may be a product of Anthony Wilkinson’s quarry (fig. 45). The underside of the stone is tabled where it abuts the frame and was originally indexed with two wooden pins, fragments of which remain in holes drilled into the top and each side rail (fig. 46). A contemporaneous pier table likely made in the shop of cabinetmakers Henry Clifton and Thomas Carteret has a marble top indexed in a similar manner. On the pier table with carving attributed to Brian Wilkinson, the top molding stops short of the back at each side (fig. 47). This suggests that the table may have had a companion pier glass that rested on the back edge, an arrangement occasionally shown in late seventeenth- and eighteenth-century engravings.[15]

Variations in the design and construction of case furniture with carving from Wilkinson’s shop indicates that he provided ornaments for several of the city’s cabinetmakers. The chest-on-chest illustrated in figures 48 and 49 is one of several examples attributed to George Claypoole, Sr. or Jr. based on stylistic and structural affinities with an example the younger man signed circa 1755. The carving on the upper center drawer consists of a shell and scroll volutes in deep relief and leaf appliques that emanate below and flow to either side. With their long curling tips and convex centers, the leaflets bear an unmistakable resemblance to other work associated with Wilkinson’s shop. One of the Claypooles may been responsible for the basic design, since other chest-on-chests attributed to them have similar drawers with carving from Samuel Harding’s shop. One of the largest versions of this design from Wilkinson’s shop is the applique on the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in figures 50 and 51. On that ornament, which is cut from a single board laminated for thickness, the leaves are similar in scale to those on the hood of the Plumstead clock (fig. 31).[16]

Carving from Samuel Harding’s Shop

Samuel Harding’s documented dates in Philadelphia only extend from 1751 to 1758, but evidence suggests that he may have been there earlier. The pattern used for the largest armorial chimney back cast at Oxford Furnace may have been carved by Harding (fig. 52). The elongated leaflets of the mantling relate closely to those on the front of the upper trusses Harding furnished for the architraves in the State House stair tower (figs. 53, 54), and the modeling of the mane of the lion is similar to that of the beards on the steeple trusses of Christ Church (fig. 12). It is likely that Jonathan Robeston or Joseph Shippen commissioned that pattern as well as the one represented by the smaller Oxford armorial chimneyback (fig. 32) simultaneously, in order to provide options for their customers. If Harding was working as a journeyman for Anthony or Brian then, it would help explain the close correspondence in some of their work.

Most of the surviving carving attributed to Harding is on furniture. A bill from him to “Mr. George Claypoole” lists a variety of components carved between May 19, 1755 and February 22, 1757 (fig. 55). Included were two rosettes, three flame finials and a shell and leaf applique for a desk-and-bookcase; two rosettes, three flame finials, and a relief carved shell with leaf appliques for a chest-on-chest or high chest of drawers; sets of legs for three pillar-and-claw tea tables; claw feet for three tables of unspecified form; and unspecified carving for a card table.

Several desk-and-bookcases with carving attributed to Harding’s shop survive, the most elaborate of which is illustrated in figure 56. The pediment is ornamented with a “Shel & Leaves cut throw,” two “flowers,” and three “blases” and a shield (fig. 57). The primary leaflets on the shield and applique have raised central spines, pointed tips, and turns that echo details on the architrave appliques, sides of the lower trusses, and friezes Harding carved for the stair tower in the State House. The shells at the center of the bookcase applique are stylistically similar to those on the Assembly Room applique attributed to Wilkinson, but the outlining, modeling, and articulation of the large linen-fold elements differ significantly.

No other case pieces with shield ornaments attributed to Harding are known, but several objects have pediments with urn-and-flame finials in the same location, as the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in figures 58 and 59 reveals. The applique on that piece differs from the one on the preceding desk-and-bookcase in the arrangement of the leaves and modeling and articulation of the shells, but both components are by the same hand. Considerable variation also occurs in the design of Harding’s rosettes and in the modeling of the flame sections of finials.

With its paneled doors and central “blase,” a desk-and-bookcase that may have been commissioned by William Logan (fig. 60) is a slightly more modest version of the one shown in figure 56. The composition and components of the applique are simpler, particularly the shell, which has flat lobes with minimal articulation (fig. 61). William Logan was the eldest son of merchant James Logan and worked with his father until the latter’s death in 1751. If William was the original owner of the desk-and-bookcase, as family tradition suggests, he likely acquired it after taking up residence in James’ house Stenton circa 1751.[17]

Only one clock with carving attributed to Harding is known (figs. 62, 63), and it has a shell and leaf applique very similar to that on the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in figures 58 and 59. The bottom edge of the clock movement’s chapter ring is engraved “Jno. Wood Philadelphia,” thus it could have been made by John Wood Sr. or Jr. The younger Wood, who was born in 1736, probably completed his apprenticeship by 1751, and his father died in 1760. The finials on the clock differ significantly from others attributed to Harding, and, if original, probably had plinth blocks like those on the desk-and-bookcases illustrated in figures 56–61 and contemporaneous chest-on-chests and high chests of drawers (figs. 64, 65).[18]

The shield Harding carved for James Hamilton’s “Bush Hill,” does not survive, but it probably resembled the one on the dining room overmantle of Woodford, a late-Georgian house built circa 1756 by Philadelphia merchant and Supreme Court Justice William Coleman (fig. 66). The upper leaves of the Woodford shield are larger versions of those capping the shield of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in figures 56 and 57, but the scrollwork and central ornament of the two objects differs. Again, the design sources for Philadelphia ornaments of this type were most likely the shields on imported looking glasses.[19]

Much of the surviving furniture and architectural carving executed in Philadelphia from the 1740s to late 1750s is either from the Wilkinson and Harding shops or influenced by them. Although the work illustrated and discussed here is separated into shop groups, a great deal of related, contemporaneous work is more difficult to categorize and is best described as being from the “Wilkinson/Harding School” (see appendix B). Although far more numerous than the objects that can be attributed to Brian Wilkinson and Samuel Harding, the seating, tables, and case pieces comprising this school attest to the importance of those two craftsmen and their respective shops.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS For assistance with this article, the author thanks Alan Miller, Jonathan Prown, and Martha Willoughby.

Appendix A

Figures 67 though 70.

(fig. 67), (fig. 68), (fig. 69), (fig. 70).

Appendix B

Figures 71 though 78.

(fig. 71), (fig. 72), (fig. 73), (fig. 74), (fig. 75), (fig. 76), (fig. 77), (fig. 78).

Eunice Story Eaton Ullman, “The Gabriel Wilkinson Family,” in Genealogies of Pennsylvania Families from the Pennsylvania Genealogical Magazine (Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Pulishing Co., 1982), pp. 281–313; See also Pennsylvania Genealogical Magazine, 26, no. 2 (1969): 61–93. At least two of Wilkinson’s siblings were involved in the shipbuilding trade; his brother Gabriel was a shipwright, and his half-brother Thomas was a ship carver. For the Torrington, see Harrold E. Gillingham, “Some Colonial Ships Built in Philadelphia,” https://journals.psu.edu/pmhb/article/viewFile/28246/28002, p. 160. The Tryal was owned by Samuel Powell and Clement Plumstead (Powell Family Business Papers, Joseph Downs Library, Winterthur Museum, as cited in R. Curt Chinnici, “Pennsylvania Clouded Limestone: Its Quarrying, Processing, and Use in the Stone Cutting, Furniture, and Architectural Trades,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite [University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2002], p. 122, nt. 140). For Penn’s barge, see https://www.raabcollection.com/american-history-autographs/thomas-penn-barge. For the Mary, see Louis F. Middlebrook, “The Ship Mary of Philadelphia, 1740,” https://journals.psu.edu/index.php/pmhb/article/view/28311.

Martha Willoughby, Wilkinson family tree, author’s possession. Andrew Brunk, “The Claypoole Family Joiners of Philadelphia: Their Legacy and the Context of Their Work,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England, 2002), pp. 147–73.

Jay Robert Stiefel, “Philadelphia Cabinetmaking and Commerce, 1718–1753: The Account Book of John Head, Joiner” (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 2001) as cited in Chinnici, “Pennsylvania Clouded Limestone,” p. 122, nt. 14. Pennsylvania Gazette, August 13, 1741. For Brian’s description of the stone quarried by his father, see Pennsylvania Gazette, July 17, 1766.

For Franklin’s letter, see https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-07-02-0157. Pennsylvania Gazette, February 28, 1765. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/11193024/anthony-wilkinson.

For Wilkinson’s marriage, see https://www.ancestry.com/interactive/2451/40355_267311-00121?pid=4005526&backurl=https://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?indiv%3D1%26dbid%3D2451%26h%3D4005526%26tid%3D%26pid%3D%26usePUB%3Dtrue%26_phsrc%3Dlhg2%26_phstart%3DsuccessSource&treeid=&personid=&hintid=&usePUB=true&_phsrc=lhg2&_phstart=successSource&usePUBJs=true.

Pennsylvania Gazette, December 1, 1748; April 5, 1749; May 3, 1750; July 9, 1752; March 26, 1754; December 25, 1755, September 8, 1757.

Pennsylvania Archives, Eighth Series, 7:6429. https://tenpound.com/bookmans-log/

book/receipt-for-work-performed-on-the-ship-delaware-by-figurehead-carver-brian-wilkinson-

philadelphia-1762.

Ullman, “Gabriel Wilkinson Family,” p. 306. Pennsylvania Gazette, July 17, 1766. Ullman, “Gabriel Wilkinson Family,” pp. 306–7.

Decorative arts scholar Donald Fennimore discovered the bill from Harding to Claypoole. The author is indebted to him for sharing that information.

Henry C. Mercer, The Bible in Iron: Pictured Stoves and Stoveplates of the Pennsylvania Germans (1914; revised, corrected, and enlarged by Horace M. Mann, Doylestown, Pa.: Bucks County Historical Society, 1961), pp. 110, 241–43, nos. 336–8. See also Jack L. Lindsey, Worldly Goods: The Arts of Early Pennsylvania, 1680–1758 (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1999), pp. 41–2.

http://www.afanews.com/articles/item/1974-stretch-americas-first-family-of-clockmakers #.XpBZBm57k6U. A dome-top desk-and bookcase that appears to be contemporaneous with or earlier than the Plumstead clock has a shield ornament that may also be a product of Anthony Wilkinson’s shop. The leafage on the ornament relates to that attributed to Brian but is perfunctory in comparison. Ornaments of this type were probably derived from those on early Georgian looking glasses. The early history of the desk-and-bookcase is not known, but it descended from Judge Joel Jones of Philadelphia to his son the Rev. John Sparhawk Jones. Judge Jones moved to Philadelphia from Coventry, Connecticut, in 1834 and subsequently married Eliza P. Sparhawk.

Mercer, Bible in Iron, pp. 96, 103, 130. John Bezís-Selfa, Forging America: Ironworkers, Adventurers, and the Industrial Revolution (Ithica, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2004).

William Macpherson Hornor, Jr., Blue Book: Philadelphia Furniture (Philadelphia: by the author, 1935), p. 65, pl. 74; Lindsey, et al, Worldly Goods, p. 154, no. 87.

https://horshamhistory.org/history/people/dr-thomas-graeme. An elegant but much simpler table with carving from Wilkinson’s shop has also been incorrectly attributed to Ireland. That object is illustrated and discussed in Lindsey, et al, Worldly Goods, pp. 154–55, no. 89. Lindsey attributed the table to Philadelphia, whereas Desmond Fitzgerald described it as Irish.

For the other table, see Chinnici, “Pennsylvania Clouded Limestone,” figs. 30–32. The top of that table was probably indexed with metal pins.

Brunk, “Claypoole Family Joiners,” p. 167, fig. 26; http://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/

ecatalogue/lot.284.html/2009/important-americana-n08512.

Lindsey, et al., Worldly Goods, p. 148, no. 75. Luke Beckerdite, “An Identity Crisis: Philadelphia and Baltimore Furniture Styles of the Mid-Eighteenth Century,” in Shaping a National Culture: The Philadelphia Experience, 1750–1800, edited by Catherine Hutchins (Winterthur, Del.: Winterthur Museum, 1990), pp. 274–75, figs. 35, 36.

Morrison H. Heckscher, American Furniture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, II., Late Colonial Period: The Queen Anne and Chippendale Styles (N.Y.: Random House for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1985), pp. 306–7, no. 198.