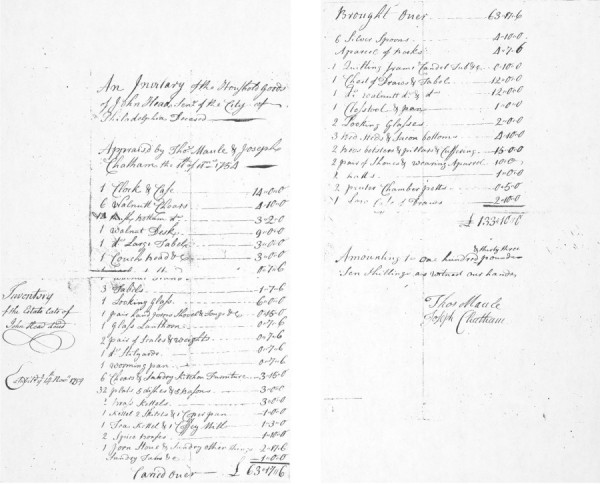

“An Inventory of the Household Goods of John Head Sen. of the City of Philadelphia Decesed Appraisd by Tho. Maule & Joseph Chatham the 11th of 11mo 1754.” (Courtesy, Philadelphia City Archives and Historical Society of Pennsylvania.)

High chest and dressing table, Philadelphia, 1726. Black walnut with hard pine and Atlantic white cedar. High chest: H. 64 1/2", W. 42", D. 23 1/4". Dressing table: H. 28 3/4", W. 33 1/2", 23 3/8". By the shop of John Head (1688–1754) and debited in his account book, p. 87 left, on June 14, 1726, to Caspar Wistar (1696–1752). (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

COMPLEMENTING THE RECENT MONOGRAPH on the account book of Philadelphia joiner John Head (1688–1754) is the discovery of his probate inventory (fig. 1). Unavailable when Head’s other original probate records were microfilmed, the long-sought document finally came to light in 2019 during the relocation of the Philadelphia City Archives.[1]

After a long and successful career as a cabinetmaker and merchant, John Head died at age sixty-six on October 6, 1754. His final will, signed on May 11 of that year, describes him as “being indisposed as to Health.” The inventory of his goods was taken on November 11, 1754. Entries in the account book become sparse after Head began winding up his furniture business in December 1744 and liquidating his stock of goods, supplies, and materials over the next four years. By the time of his death, no shop goods may have been left to value; thus, his probate inventory appraised only his household goods. As was customary, the inventory valued none of Head’s real estate holdings. (His will lists seven properties, six of them in the city and one, his country seat, along the Frankford Road.) Below is a transcription of the two-page inventory.[2]

An Inventory of the Household Goods of John Head Sen. of the City of Philadelphia Decesed Appraisd by Tho. Maule & Joseph Chatham the 11th of 11mo 1754

1 Clock & Case 14.0.0

6 Walnutt Choars 4.10.0

14 Rushe Bottum do 3.2.0

1 Walnut Desk 9.0.0

1 do Large Tabel 3.0.0

1 Couch Bead &c 3.0.0

1 Walnut Stand 0.7.6

3 Tabels 1.7.6

1 Looking Glass 6.0.0

1 pair hand irons Shovel & Tongs &c 0.15.0

1 glass Lanthorn 0.7.6

2 pair of Scales & Weights 0.7.6

1 do Stilyards 0.7.6

1 worming pan 0.7.6

6 Choars & Sundry Kitchen Furniture 3.15.0

32 plats 5 dishes & 5 Basons 3.0.0

2 Brass Kettels 3.0.0

1 Kettel 2 Skilets & 1 Coper pan 1.0.0

1 Tea Kettel & 1 Coffey Mill 1.3.0

2 Spice Boxses 1.10.0

1 Iron Stove & Sundry other things 2.17.6

Sundry Tubs &c 1.0.0

Caried over £63.17.6

Brought over 63.17.6

6 Silver Spoons 4.10.0

A parcel of Books 4.7.6

1 Quilting frame Candel Tub &c 0.10.0

1 Chest of Draws & Tabel 12.0.0

1 do walnut do & do 12.0.0

1 Closstool & pan 1.0.0

2 Looking Glasses 2.0.0

3 Bed Steds & Sacon bottoms 4.10.0

2 Beds bolsters & pillars & cuffering 15.0.0

2 pair of Shoues & wearing Aparrel 10.0

2 hatts 1.0.0

2 peuter Chamber potts 0.5.0

1 Low Case of Draws 2.10.0

£133.10.0

Amounting to one hundred & thirty three pounds Ten shillings as witnest our hands

Thos Maule

Joseph Chatham

Interpretation of Head’s probate inventory is aided by his account book. The appraisers, both joiners, did business with Head and have accounts in his book. Among other things, Head charged Joseph Chatham (fl. ca. 1740–1754) for a frame and “five ledges [legs] for a Chest of drawers.” Thomas Maule appears to have been Head’s apprentice. Upon the latter’s retirement from cabinetmaking, Maule purchased a joiner’s bench and furniture hardware from him. As furniture usually comprised the most expensive goods in an estate, having first-hand knowledge of what Head’s furniture was worth made Chatham and Maule obvious choices as appraisers.[3]

Head’s probate inventory is especially useful in identifying the property he held at his death. Apart from “a Clock & Case” bequeathed to his daughter Rebecca Jones (1713–1787), his will is unspecific as to furniture or other household goods; they were collectively dispersed to his widow and another daughter. As only one clock is listed in the inventory, valued at £14.0.0, it was that for Rebecca.[4] Observations regarding other items in the inventory follow.

The “Walnut Desk” appraised at £9.0.0, even second-hand, must have been substantial, specially embellished, or of elaborate design. For his most popular model of new desk, Head charged only £6.0.0. For a “Larg” walnut desk he got £8.10.0, the same as he charged for each of two in mahogany. Only one of Head’s desks cost more, £12.0.0, and was the last sold.[5]

The “Couch Bead &c” valued at £3.0.0 may be one of the two “Couch[es]” or daybeds he had bought for £1.4.0 from chair maker Solomon Cresson (1674–1746) on October 7, 1729, only one of which Head had sold. Head made no couches or other seating furniture himself. He did record “mending a Couch” for merchant John McComb Jr. (fl. 1720–1726) on April 25, 1721, at a cost of £0.0.6. One popular covering for seating furniture was leather. Head had provided a “Couch Hide” to cordwainer William Clare (1675–1741) on February 18, 1723, at a price of £0.3.0.

The “pair hand irons Shovel & Tongs &c” valued at £0.15.0 may have included the “payer of hand irons” that Head had purchased from George Kelley (fl. 1742–1744) for £1.0.0 on December 18, 1742.[6]

Given their low collective valuation of £1.10.0, the two “Spice Boxses” listed among other kitchen metal ware were presumably of like material and not similar to either of the two wooden spice boxes that Head made in his shop. One, at £2.10.0, sold on April 15, 1735, to his best customer, James Steel (ca. 1671–1742), the receiver general. The other, at £1.10.0, sold on July 25, 1736, to Samuel Burrows Sr. (fl. 1727–1738).[7]

“A parcel of Books,” inventoried at £4.7.6, is intriguing. Although Head built bookcases for others, there are no entries in his account book for books. Nor is there a record of Head’s being a member of a subscription library, such as the Library Company of Philadelphia, founded in 1731. A devout Quaker, one would expect religious tracts to be among his possessions or, possibly, Thomas Chalkley’s (1675–1741) travel journal, a work often listed in contemporary Philadelphia inventories. Regrettably, the appraisers listed no titles.[8]

The inventory entry for “1 Quilting frame Candel Tub &c ,” valued at £0.10.0, is a reminder of the utilitarian items that John Head’s shop supplied both for households and to his fellow tradesmen. He charged shipwright Nathaniel Pool (fl. 1709–1727) £0.7.6 on February 9, 1722, for a “Qwilting frame & Trusels [trestles],” and merchant Alexander Wooddrop (1685–1742) £0.7.0 on April 7, 1722, for a “Candle Trof [trough].”[9]

The two entries for a walnut “Chest of Draws & Tabel,” each valued at £12.0.0, were no doubt en suite pairs of high chests and dressing tables at least as fine as the pair in highly figured black walnut (fig. 2) ordered from Head by Caspar Wistar—together with an oval table—at a cost of £10.0.0 on June 14, 1726, three weeks after Wistar’s marriage to Catherine Johnson (1703–1786) of Germantown and paid for by her father on June 15. On April 30, 1730, Head also sold Wistar a clock case, for £4.0.0. It is the earliest known, fully documented Philadelphia tall-case clock, and has its original eight-day tide dial movement by William Stretch (1701–1748). [10]

The inventory entries for “3 Bed Steds [bedsteads] & Sacon [sacking] bottoms,” at £4.10.0, and for “2 Beds bolsters & pillars [pillows] & cuffering [covering],” at £15.0.0, complement the entries for fifty-two “Badstads” in Head’s account book, some of which were ordered two at a time, suggesting their use as pairs. Some of Head’s bedsteads included charges for curtains and cornices. He also sold items required for beds, such as feathers and sacking bottoms. The £15.0.0 valuation for two of the beds in Head’s household is unsurprising given that beds and their furnishings, along with clocks and their cases, were typically the most expensive items appraised in colonial inventories.

A silver cann by Philadelphia silversmith Joseph Richardson Sr. (1711–1784) and various documents have been passed down in John Head’s family. As yet no furniture of his has been identified as having similarly descended, notwithstanding that over sixty pieces can be documented or attributed to his shop. Also unaccounted for is his daybook, from which entries were transferred into his account book. Such items may one day also be discovered, complementing the fortuitous survival of John Head’s account book and probate inventory.[11]

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For assistance with this article, the author thanks Adam Bowett, Donald Fennimore, Patricia O’Donnell, Margaret Maxey, and Christopher Storb. This article is dedicated to the memory of Robert S. Cox.

Jay Robert Stiefel, The Cabinetmaker’s Account: John Head’s Record of Craft and Commerce in Colonial Philadelphia, 1718–1753, Memoir 271 (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 2019); the will of “John Head . . . Joyner,” signed May 11, 1754, with a codicil signed September 19, 1754, and proved October 18, 1754, Philadelphia Wills 1754-136. The Philadelphia City Archives opened at its new location, 548 Spring Garden Street, on December 6, 2018. Thanks to Margaret Maxey of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, a copy of the probate inventory was made and is now available in its autograph collection (#22) under “Head, John (1688–1754)”: John Head will and inventory of household goods, 1754 [copies], Collection DO476/22A, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pa. Prior to the inventory’s disappearance, one of its entries had been cited by another researcher in 1964. Stiefel, The Cabinetmaker’s Account, pp. 12, 17n4.

John Head’s last entry for furniture was on December 27, 1744, for a “walnut chest of drawers—in 3 parts” which, together with “a Little Chest of Drawers,” cost blacksmith John Rouse (d. ca. 1778) £18.0.0. Twenty days prior, Head had sold “a Joyners Bench” to Thomas Maule (b. 1720; fl. 1744–1755). Between 1744 and 1747 Head also sold off to Maule large quantities of furniture hardware. On May 24, 1748, Head’s son-in-law Benjamin Hooton (1719–1792) bought thousands of board feet of lumber from him. Stiefel, The Cabinetmaker’s Account, pp. 254–255.

Ibid., pp. 65–66, 135, 170.

Ibid., pp. 12, 91, 218–226; Philadelphia Wills 1754-136.

Stiefel, The Cabinetmaker’s Account, p. 233.

Ibid., p. 129.

Ibid., p. 243.

Ibid., p. 234; Thomas Chalkley, A Collection of the Works of Thomas Chalkley (Philadelphia: Printed by B. Franklin, and D. Hall, 1749).

Stiefel, The Cabinetmaker’s Account, p. 245.

Ibid., pp. 151–157, 179–186.

Ibid., pp. 2, 13–17, 47–49, 255.