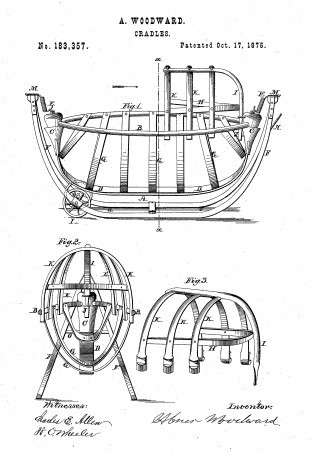

Abner Woodward, drawing for U.S. Patent 183,357, October 17, 1876. (U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.)

Woodward patent cradle. (Courtesy, Leland Little Auctions.)

Woodward patent cradle. (Courtesy, Jeffrey S. Evans and Associates Auctions; photo, William McGuffin.)

Woodward patent cradle. (Courtesy, Nebraska History.)

Woodward patent cradle. (Courtesy, Canadian Museum of History.)

Woodward patent cradle. (Courtesy, Heinz History Center.)

Woodward patent cradle. H. 30", W. 50", D. 24". (Courtesy, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.)

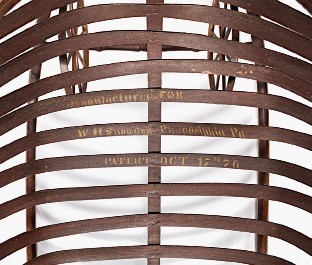

Detail of the stenciling on the cradle illustrated in fig. 6.

Detail of the stenciling on the cradle illustrated in fig. 7.

Detail of the wheel end on the cradle illustrated in fig. 7.

Cradle, southeastern Massachusetts, 1660–1700. Red oak, white pine, maple. H. 32", W. 33 3/4", D. 24 1/4". (Courtesy, Wadsworth Atheneum.)

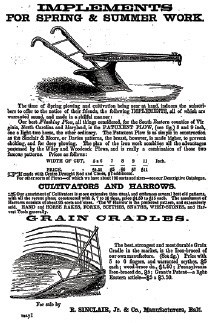

Advertisement for Sinclair and Co. Grain Cradles, American Farmer (June 1858): 415.

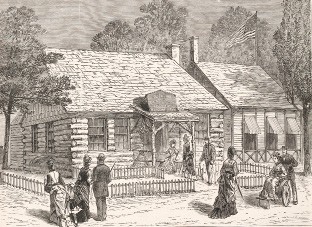

“New England Kitchen,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Historical Register of the Centennial Exposition (1876). Wood engraving. (Courtesy, Library of Congress.)

Woodward cradle model, “Old and New England, an Exhibition,” Rhode Island School of Design, January–February 1945. (Courtesy, Getty Life Magazine Archive; photo, Fritz Goro.)

Cradle, South Carolina, 1830–1860. Yellow pine. H. 15 1/2", W. 40", D. 23". (Courtesy, National Museum of African American History and Culture, Smithsonian Institution.)

Upholstered baby carriage, 1890–1899. Wicker, beech, iron, fabric. H. 39", W. 48 1/2", D. 20". (Courtesy, Minnesota Historical Society.)

Bassinet with stand, Harper’s Bazaar (June 7, 1890): 23.

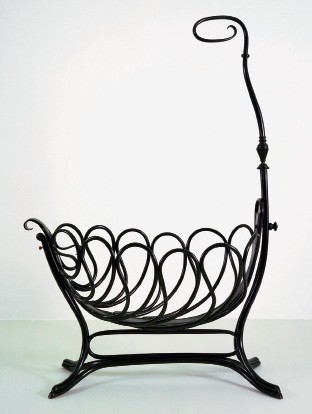

Cradle or bassinet, J. and J. Kohn, Austria, ca. 1895. Ebonized laminate. H. 80 1/4", W. 56 1/4", D. 25 7/16". (Courtesy, Museum of Modern Art.)

Berthe Morisot, Le Berceau, 1872. Oil on canvas. H. 22" x W. 18". (Courtesy, Musée d’Orsay.)

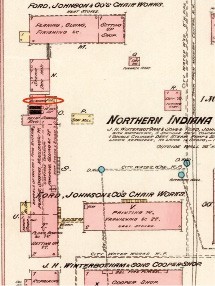

Detail of the Sanborn Fire Insurance map of Michigan City, Indiana, 1884, p. 7, showing “Ford, Johnson, & Co.” factory buildings inside “Northern Indiana State Prison,” with engine room stocked with “bending fuel” circled. (Courtesy, Library of Congress.)

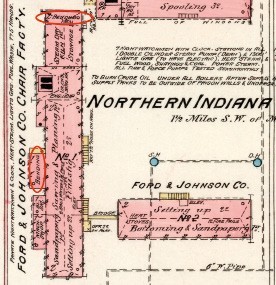

Detail of the Sanborn Fire Insurance map of Michigan City, Indiana, 1889, p. 16, showing the “Ford & Johnson Co.” factory buildings, with “bending rooms” circled. (Courtesy, Library of Congress.)

Photograph showing workers in the bending room at the Thonet Brothers factory in Boppard-am-Rhein, Germany, ca. 1900. (Courtesy, Museum Boppard.) Thonet pioneered the industrial production of bentwood furniture.

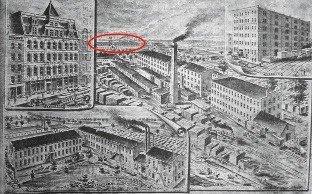

Lithograph showing the Ford, Johnson and Co. Chicago showroom and warehouse, and the new Michigan City factory complex, with the Indiana State Prison North circled in the background. In: American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer (September 1890): 13.

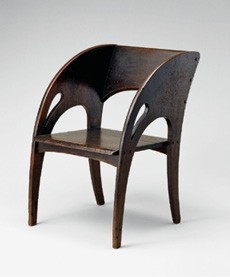

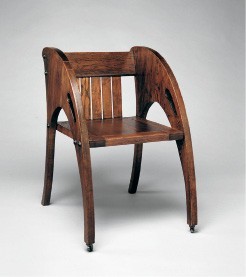

Chair, Ford-Johnson Co., Michigan City, Indiana, 1904–1905. Oak. H. 31 7/8", W. 20 1/2", D. 9 5/8". (Courtesy, Art Institute of Chicago.)

Chair, Ford-Johnson Co., Michigan City, Indiana, ca. 1904. Oak, poplar. H. 31 1/2", W. 20 3/8", D. 25 1/2". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

IN 1876 HOTELIER-CUM-TINKERER Abner Woodward of Shelburne Falls, Massachusetts, patented an innovative baby cradle (fig. 1). Deploying recent advancements in bentwood production and the steel coil spring, he claimed his new product was “light weight, strong, and at the same time, on account of its peculiar construction, it is elastic in all its parts, susceptible to the slightest motion and therefore easily swung.” Woodward also incorporated two small wheels on an axle stretching across the cradle’s supporting runners on one end, “thereby combining with it all the advantages of a baby carriage.”[1]

Woodward intended his cradle to facilitate motion, but he never could have imagined where it would get pulled. Designed to help caretakers move babies, collectors and museums have subsequently wheeled it into stories about childcare and labor that exaggerate mobility and the notions of freedom and progress it often connotes. Tracing this history explodes romantic myths that obscure important truths about agricultural, enslaved, and incarcerated labor. It also indicates the need for more scholarship on early industrially-produced furniture.

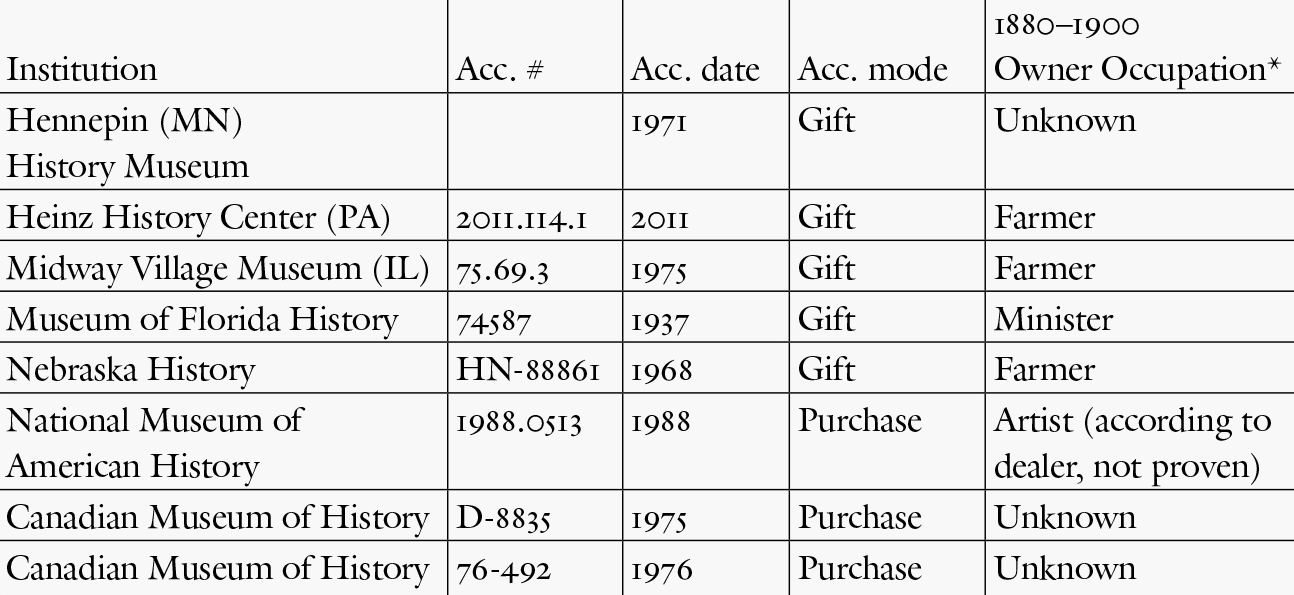

Abner Woodward lost control of the rights to his cradle when he sold his patent to J. S. Ford, Johnson, and Company, a furniture manufacturer best known for chairs, desks, and benches. No record of that sale survives, so its exact date is unknown. But by 1882 Ford-Johnson was marketing a “Patent Cradle and Carriage” in its catalogs. Today these cradles regularly appear on the antiques market (figs. 2, 3) and in private and institutional collections, including those of the Hennepin County Historical Society in Minnesota, Midway Village Museum in Rockford, Illinois, the Nebraska and Florida state history museums, the Heinz History Center in Pittsburgh, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, and the Canadian Museum of History (figs. 4–7). All these examples largely reflect Woodward’s design, with minimal variations in color and construction. Most of them also reference the Ford-Johnson name, its factory site in Michigan City, Indiana, or the date of Woodward’s patent, stenciled on the bent slats that compose the cradle bed’s ribbed body (figs. 8, 9).[2]

Yet no museum or auction catalog refers to any of these pieces as a “patent cradle” or “cradle and carriage,” as Ford-Johnson catalogs variously called them. Instead, today they are described as a “slave cradle,” “mammy cradle,” or, most commonly, a “field cradle.” Online image searches using any of these terms will turn up dozens of examples of Woodward’s model. All three newer terms stem from interpretations that claim that these cradles were “designed as a convenience for agricultural workers to enable them to carry their infants around in the fields with them as they worked.” Coverage of the 1998 opening of Detroit’s Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History described their example similarly, calling it a “‘field,’ or ‘slave’ cradle that is believed to have been used by slave women to care for their babies while working the fields.”[3]

This nomenclature is rooted in myths that are as useful to unpack as they are necessary to refute. Most obviously, a cradle model patented in 1876 and bearing the name of a factory site that did not exist before 1868 is hardly likely to have been used by people whose enslavement legally ended with the adoption of the Thirteenth Amendment at the end of 1865. But even the appellation of “field cradle” is hard to sustain after a closer analysis of the cradle and the provenance both of surviving examples and the term itself.[4]

First, the cradle’s form is not suggestive of field use. Stretching twenty-four inches at the widest point of the hanging bedframe, it would have left scant space between cotton and corn rows that typically were planted between thirty and forty-eight inches apart in the late nineteenth century. Those intervals shrank toward the lower end of the range over time as farm machinery encouraged more efficient use of planted acreage.[5]

Even if it were squeezed between rows, the cradle would have impeded workers’ movement, especially amidst full-grown crops at harvest time. It is hard to imagine farm families coordinating field labor to accommodate a cradle. Additionally, although the use of lightweight hickory for the cradle bed made it weigh just twelve pounds, the narrow one-inch width of each small ten-inch-diameter cast-iron wheel would have sunk into, rather than displaced, muck or mud (fig. 10). A residue of bronze paint on the wheels of several examples further suggests that the cradle was built for display more than utilitarian use on earthen surfaces likely to obscure and remove the paint.[6]

Calling out this evidence should not play into one myth while debunking another. There is evidence of mothers taking smaller cradles into the fields. Over the last twenty years, agricultural historians have discovered ample documentation from diaries and letters to dispel old notions of a firmly gendered division of farm labor that excluded women from fieldwork. The outdated interpretation was derived from officious prescriptive literature, but most farm families simply could not afford to follow it by absolving wives and daughters from fieldwork. Yet the newer studies note that while mothers did sometimes bring babies into the fields, most families relied on visiting relatives, neighbors, and older siblings to care for them when mothers headed into the fields. Especially in the later nineteenth century, as practices of swaddling were abandoned in favor of freer movement for infants, taking this particular cradle into the fields would have severely hampered a mother’s productivity. Moreover, its gently sloping sides and the swinging capacity its inventor trumpeted would have combined to increase the chances of a fall for an unswaddled baby. This cradle’s design required close attention to its occupant compared with that for earlier cradle forms featuring high boarded sides and notched rockers to prevent tipping (fig. 11). So while it is possible that these cradles might occasionally have been used in fields, it is unlikely; they certainly were not designed, advertised, or known for such use.[7]

Indeed, none of the provenances for the eight museum-owned examples in this study references field use. Five were gifted to the museums that hold them today. Donated between the late 1930s and early 2000s, four of the five donors traced their cradle back to late nineteenth-century family members who were either reared on farms or reared babies on farms. But they called their examples a “swinging crib cradle,” “baby cradle,” or just a “cradle.” None described it as a “field cradle,” let alone a “slave cradle” or “mammy cradle.” The fifth piece descended through the family of a minister, none of whom was connected with farm work.[8]

The other three examples in the sample were purchased by museums. Only one, bought from an antiques dealer by the Canadian Museum of History in 1976, has any record of the item being called any of the popular terms used today (fig. 5). The Smithsonian’s example was purchased from an antiques dealer in 1988 and bears the name of Philadelphia chair maker William Snowden, not Ford-Johnson (fig. 9). Snowden ventured into furniture retail between 1888 and 1896, and his advertisements never deployed the phrases common today.[9]

That makes sense, because until about 1970 references to “field cradles” described a fingered scythe used to cut and gather (or “cradle”) grain (fig. 12). Auction notices, which are the most common places to find the term, always list “field cradles” next to other agricultural implements. Only in the mid-1970s were references to field cradles grouped with domestic artifacts, indicating the term’s shifting application toward infant furniture. The term “slave cradle” first appeared in 1975, at the leading edge of a dramatic expansion in collecting “Black Americana” that was initially driven by white dealers and collectors with more nostalgic than accurate views of slavery and racism in the United States. By the 1980s references to both “field cradles” and “slave cradles” often included descriptions of “iron wheels” and sometimes the Ford-Johnson stenciling, providing specific evidence that the cradles under discussion here were the ones driving the newly invented cradle categories.[10]

If it is clear that the current terminology for these cradles is not accurate to the period of their manufacture and only arose in the 1970s, we still need to ask why these terms emerged when they did and why they have remained in usage. Answering these questions relies on circumstantial and contextual evidence, since the material and documentary evidence that explicitly exposes the terminology’s fictional and anachronistic roots does not explain why that usage surfaced when it did. But the potential conclusions also point to a much bigger problem than factual error.

The timing of the “field” and “slave” references suggests a connection to the rise of social history. Starting in the 1960s, in response to the Civil Rights Movement and as a result both of more diverse students pursuing graduate study in the wake of the G.I. Bill and higher education’s expansion to accommodate the baby boomer generation, a new generation of historians veered away from scholarship’s traditional focus on leaders and elites. Their work tended to highlight the domestic, working, and community lives of people disempowered by inequities of race, ethnicity, gender, and class.[11]

For museums and collectors, this new scholarly emphasis on the everyday lives of everyday people was less a complete shift than a new layer added on top of longstanding interests in the historical material culture of daily life. In fact, scholars have argued that both the antiques market and history museums as we know them today in the United States are products of the nation’s centennial celebrations in 1876 (fig. 13). The centennial prompted exhibitions and restorations of historic buildings, featuring re-created spaces furnished with antiques that were supposed to reflect the lives of colonists who hailed from Northern Europe. The larger movement known as the Colonial Revival sprang from the growing fascination with these artifacts among the middle-class and wealthy white Americans who laid claim to this heritage.[12]

The interpretations embedded in the Revival’s antiques craze forged lasting nostalgic notions of heroic individualism and “Yankee Ingenuity,” as Life magazine put it in a 1945 photo essay that originally included an image of another Ford-Johnson cradle (fig. 14). This framework of self-reliance, innovation, and progress served the purposes of the established white Americans who initially drove the Revival. In the decades after 1876, it “instructed” the nation’s African American and burgeoning immigrant populations in “American values” while anchoring those values in Northern and Western European heritage. The cradle’s inclusion in the exhibit illustrated by the Life photo essay, a show at the Rhode Island School of Design pulled from several New England museum collections, reveals how the Colonial Revival’s interpretive premises—not to mention its chronological boundaries—were not bound by the colonial period. Only such an ahistorical and ideological approach to the past can explain how a cradle patented in the year the Colonial Revival began, and pumped out of a Midwestern factory by the thousands over the next two decades, could be exhibited seventy years later as evidence of the handcrafted “wits” of “early Yankee settlers.” The point was not to research and illuminate the colonial period, but to justify the maintenance of racial and ethnic hierarchies in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries by celebrating the nation’s history up until then as a foundation laid by the hard work and ingenuity of simpler and purer Americans who all happened to hail from Northern and Western European ancestry.[13]

In the museum sector and antiques market, which did not diversify as extensively or deeply as it did in the academy, the social histories of the 1960s and 1970s did not create a new layer of understanding that buried the Colonial Revival. Instead, curators and dealers folded the new research into the Revival’s lasting interpretative emphasis on hard work leading to innovation and progress. The result broadened whose ancestors were celebrated, but it changed neither what was celebrated nor the central intent to romanticize and celebrate the past. The effects remain with us today, as continuing interpretations of the cradle suggest, and have led scholars to conclude that “the Colonial Revival refuses to die.” There is no way to know for certain why the cradle became associated with enslaved people or agricultural fieldwork, but the explanations accompanying and supporting recent museum interpretations of it—that it allowed “mothers to take their children with them into the fields”—essentially extend the Revival’s interpretive framework to artifacts (not always accurately) representing the broader range of people brought into the nation’s historical narrative by social historians. A Colonial Revival lens distorted the cradle’s actual presence among white farming families, overstating self-reliance and independence while eliding the networks of community and extended family that actually helped them care for their babies.[14]

Shoehorning the cradle into interpretive frameworks inherited from the Colonial Revival has graver consequences for its erroneous association with enslaved mothers. Here, the cradle’s supposed use disregards the realities of slavery. Applying social history’s emphasis on the humanity and agency of enslaved people without escaping the confines of the Revival’s themes, curators, collectors, and dealers perhaps hoped to make up for Colonial Revivalists who had either ignored enslaved people or grossly misrepresented them as “servants.” But the result fails to recognize that enslaved mothers did not possess legal rights to their children. They did not have the power to decide to bring their babies into the fields with them, even if the cradle could have been used for that purpose. Small wonder, then, that the few surviving examples of baby cradles with better provenance to enslaved parents in the antebellum era are either flat “cradle boards” or resemble older Euro-American forms more closely than they do Woodward’s bentwood model (fig. 15). Enslaved mothers did not wheel their babies into the fields in newfangled cradles because, typically, they received temporary assignments to non-field labor immediately after giving birth, and their infants were later supervised by disabled, sick, or older enslaved women who could no longer do fieldwork at the demanded pace. Neglecting this history in favor of envisioning enslaved mothers as individuals with the freedom and mobility to care for their babies while they labored in the fields as human property ultimately romanticizes slavery and thus aligns with the Revival more than corrects it.[15]

Romantic myths are hardly uncommon in interpretations of historic furniture. The notion that mirrored pier tables were designed to help ladies check their petticoats, or that shorter chairs and beds indicated shorter people, have been hard to dispel because they appeal to popular perceptions of the colonial and early national periods as quaintly backward in comparison to modern times. Into the early twentieth century, Colonial Revivalists celebrated the superiority of their era even as they also celebrated earlier Americans for initiating the ethos of invention and progress that set the stage for their own creation of a better “modern” world, with women freed from binding layers of fabric and everyone allegedly getting taller. Mobility has also been central to this narrative. Just as sailboats and wagons gave way to steamships and railroads, the Revival trumpeted Woodward’s cradle as an antiquated yet innovative early step forward in a linear progression of individual mobility that improved everyone’s lives, supposedly enhancing the independence and self-reliance of farm families and even enslaved mothers.[16]

The cradle’s interpretation since the 1970s demonstrates that these themes have remained lodged in popular understandings of all sorts of unassuming artifacts. At a moment when police brutality and the COVID-19 pandemic have combined to bring systemic racism and the tensions among individual freedom, communal action, and state power to a tipping point in the United States, this cradle indicates just how thoroughly scholars, curators, collectors, and dealers must examine the stories behind every artifact if we are to correct myths and share more accurate histories through furniture.

Abner Woodward would not be disappointed by his cradle’s association with innovation, independence, and self-reliance. However, he would be irked by its popular categorization as a quaint technological advance that might have come from the antebellum or earlier eras. He saw his “new and useful Improvement in Baby-Cradles” as path-breakingly modern in 1876, and its design and production suggest that, by contemporary standards, it was. Exploring how the cradle is modern in many ways reveals a more accurate and relevant interpretation of it.[17]

First, Woodward’s cradle reflected recent shifts in child-rearing. The centuries-old practice of placing a tightly swaddled baby in a traditional board cradle that rocked on the floor initially came under assault in the 1750s, but not until the 1830s and 1840s did opposition become widespread in the United States. The change resulted from a broader critique of older ideas about childhood, which now considered children to be naturally pure rather than born in need of coercive correction. As a result, authors on parenting began recommending freer movement and more fresh air, not constant constraint and protection. By elevating the rocking bed and deploying spaced bentwood ribs in place of traditional solid board construction, Woodward’s cradle enhanced air flow and followed the newer thinking.[18]

Second, even more current than the child-rearing recommendations that the model reflected was its combination of the cradle form and, as Woodward stated in his patent application, “all the advantages of a baby-carriage.” Baby carriages emerged in the 1860s as child-sized vehicles pulled by hand or by small mule or pony. By the 1870s they were increasingly pushed, not pulled, evincing the rise of longer daily walks in the fresh air (fig. 16). Woodward developed his model before this change materialized, as is demonstrated by the incorporation of a gently-curled tongue at one end instead of a push bar.[19]

Whatever the terminology Woodward used, by adding two wheels instead of four and by stabilizing the cradle with two thick long runners (for which Ford-Johnson used oak), his cradle actually comes much closer to resembling a bassinet than either a cradle or a carriage. Bassinets developed in the 1830s as portable beds, and by 1850 they had become baby showpieces—furniture designed to elevate and display little ones in polite parlors. They generally featured a light frame, often of wicker or bentwood (figs. 17, 18). Godey’s Ladies Book advertised a less portable version in 1880, an “infant’s bassinet made of walnut, with quilt made of French muslin, with embroidered border around it and monogram, lined through with blue silk. Curtains of French muslin, lined also with blue silk, and finished all around with insertion and edging of antique lace, looped back with bows of satin ribbon.” With a mattress inside and layers of fabric lining the frame to make it softer and warmer for unswaddled babies, the bassinet became an oft-pictured element of respectable motherhood in the late nineteenth century (fig. 19).[20]

Considered within the context of evolving child-rearing advice and children’s furniture forms, the Ford-Johnson company’s version of Woodward’s cradle is more accurately interpreted as an affordably-priced bassinet. Woodward had also designed a classic cradle hood to cover the baby’s head, but Ford-Johnson never produced that element. The company sold their version to wholesalers for $27.00 per dozen, or about $2.25 each. A “canopy stand” from which to hang curtains (as in figs. 18 and 19) cost an additional twenty-five cents each. The finished products often retailed for less than fifty cents more because, as Sears put it in its 1897 catalog, “manufacturers are long on cradles and short on cash.” In comparison, bassinets rarely sold for less than seven dollars. With brightly-colored frame options, gold-painted detailing on the legs and top rail of the bedframe, as well as bronze-painted wheels, Ford-Johnson’s product still presented as an elite furniture form clearly designed for interior, not outdoor, use—just at a more accessible price point.[21]

Ford-Johnson was able to offer that price by significantly lowering production costs in two ways. First, rather than luxuriously bending wood into intricate curves, the company followed Woodward’s model and avoided ostentatious ornament. Virtually every piece of wood in its “cradle” (hereafter described as a bassinet) was bent using industrial steam technology that did not become widespread until the 1850s, making the piece’s construction method another way in which the piece was modern. Yet neither the bending nor the assembly methods were technically advanced. There were no scarf joints or other efforts to make multiple pieces of bent wood appear as one. The bassinet’s bent bed ribs were simply and visibly nailed to the bedframe’s center spine and then through a groove cut under the bed’s top rail. The two long oaken bent runners were similarly visibly screwed to a head block. Then the pieces were painted.[22]

Second, the Ford-Johnson company saved more money on labor than on production techniques. As the stenciling on many of the surviving examples notes, the bassinets were fabricated in Michigan City, Indiana (fig. 8). The Ford-Johnson company moved there in 1868 after native Ohioans John Sherlock Ford and Henry W. Johnson forged their partnership in Columbus, Ohio, the year before. Why relocate to a small Indiana town with less than four thousand full-time residents? Because Indiana’s State Prison North had opened in Michigan City in 1860, and it offered cheap labor just sixty miles from the national railroad hubs in Chicago.[23]

Annual prison reports to the state legislature show that Indiana state officials signed contracts with Ford-Johnson to employ between fifty and three hundred incarcerated workers in Michigan City every year between 1869 and the company’s bankruptcy in 1913. From 1880 to 1892 the reports specifically reference cradles among the products prisoners produced. An 1887 federal report on prison labor nationwide, the first of several executed at the behest of free workers who claimed they were losing work to lower-priced prison labor, logged 4,632 cradles manufactured in Michigan City that year and described the cradles as “medium” grade goods, befitting their standing between simple board cradles and high-end bassinets. Between the stenciling on the surviving examples and this documentary evidence, there can be little doubt that the Woodward “patent cradle” is the product described in these reports.[24]

Indiana’s wardens and legislators pursued contracts with Ford-Johnson because they had long sought to copy the example set by New York, which pioneered penal contract labor in the 1820s. The theory behind this strategy was that the prison system would pay for itself by renting prisoners’ labor to manufacturers, while prisoners would learn discipline and employable skills through hard work. Because the state covered any losses, and its standards for housing, clothing, and food kept per-person costs lower than what most free workers charged, prison wardens sold prisoner labor well below market rates. The 1887 federal report contrasted the $0.57 average daily pay cited in Indiana’s most recent annual state prison report to the $1.75 cost per free worker for similar labor in Indiana. Combined with two or three other manufacturers on site, producing barrels, shoes, and hosiery, the state’s annual reports show that even receiving less than one-third the cost of free labor covered the prison’s bills and often generated a surplus.[25]

For Ford-Johnson, the savings amounted to at least $300,000 per year. By comparison, one of the company’s most lucrative contract opportunities, to supply furniture for the new U.S. Senate Office Building in Washington, D.C., was worth $100,000. Considering Ford-Johnson expanded its prison production over time, with critics complaining by 1911 that the company “controlled the labor of some 1500 convicts in several prisons from Connecticut to Kentucky,” its annual savings accrued through the use of incarcerated labor must be seen as a primary element of its business model. As the company constructed its network of prison labor, it spawned subsidiaries and a consortium of similar companies, derisively known as the “chair trust,” that colluded to control prison labor costs in the early 1900s. Studies of early industrially-produced furniture have not examined this national network, but the 1887 federal report lists furniture as the sixth-largest grossing prison industry in the country, employing nearly 3,500 inmates across sixteen states and producing goods worth $1.28 million that year.[26]

The bassinet in question was the second-highest grossing product, in per unit terms, across all goods made at the thirty-three prisons covered in the federal report. As the Smithsonian example evinces (fig. 7), some bassinets were stenciled with retailers’ names on them and shipped at least as far away as Philadelphia. Based on the production number for 1887, but taking into consideration that production capacity increased with a new factory building inside the prison in 1885, Indiana State Prison North inmates likely produced somewhere around forty thousand of these bassinets over the course of the twelve years they are known to have been produced. The provenances in this study’s sample show purchasers ranging from Minnesota to Pennsylvania, with families later taking their bassinets as far afield as Nebraska and Florida.[27]

State governments enabled companies like Ford-Johnson to amass their reach and profits by providing more than cheap labor. Because wardens in the North were not willing to send the vast majority of their incarcerated populations to work outside their prisons’ walls, states subsidized the construction of factories within their prison complexes. The result was a very different system from the “convict lease” practices that granted employers in the post-bellum South much more control over prisoners and have received much more scholarly and public attention.[28]

Yet if working within the “contract” system limited Ford-Johnson’s control over prisoners by keeping them within the walls, the company gained factory infrastructure at little or no cost, including a new two-story engine house and dry kiln inside the Michigan City prison that expanded production capabilities in 1885. That engine house and dry kiln were almost certainly used to produce the bassinets in question. An 1884 Sanborn Fire Insurance map (fig. 20) shows twin 120-horsepower engines in a room stocked with “bending fuel.” These assets were bolstered by the 1885 additions that appear on the subsequent Sanborn map issued in 1889 (fig. 21), indicating larger first- and second-floor bending rooms where a double-cylinder steam pump used to “heat steam & stoves” probably generated the hot steam necessary to liquefy resins inside wood, rendering it pliable. Under the watchful eyes of both prison guards and company foremen, workers had only minutes to pull the wood from steam boxes and then bend and clamp it into cast-iron forms (fig. 22). Then, the forms were moved to the “steam dry kiln,” where heat evaporated the resins and dried the pieces in their final bent shapes. Having the kiln built into the main factory structure in 1885, when it had previously been in a separate building, protected the pieces from drastic changes in temperature or humidity that could affect the strength of the bent wood.[29]

The heat and quickness required to fabricate bentwood parts created hellish work under any circumstances. Draconian policies imposed by wardens and Ford-Johnson made conditions worse. No surviving first-hand sources describe working on the bassinets, but the Fort Wayne Daily News published an exposé on the Ford-Johnson chair shop inside the prison in 1884. According to a recently released prisoner, chair construction was the work of “the weakest inmates,” being “more tedious than laborious.” But while “those beautiful chairs, models of good workmanship, are brought to a high state of perfection,” the freed man said, “let us not flatter ourselves that because of this industry that our criminals are becoming reformed.” The promise of imparting employable skills was not realized because:

They do not learn enough of this branch of labor to be able to profit by their prison experience on their release; and why? Because according to their ability and alertness they are assigned to a particular branch. For instance, some sand paper the rounds, moulding, etc., others cane the seats and so on; their only object, Shylock-like, is to obtain the price of their contract, to grind it out of their helpless victims, at any cost.

Beyond the specialization that limited a prisoner’s skill set, the former inmate described a work environment hardly conducive to learning. For instance, he noted, “in this shop, as in all the different wards of the prison, strict silence must be observed, and any breach of this rule is followed by swift and sure punishment,” including whipping and the use of a “Dark Ages” thumb screw. Perhaps such treatment explains why, one night in September 1904, the Ford-Johnson shops “burst into flames, as if it had been saturated with kerosene.”[30]

The Daily News’s source described processes of de-skilling that had been going on in furniture shops for generations, but his testimony laid bare the distance between industrial furniture production and the rhetoric justifying contract prison labor. A prison furniture factory was not, in practice, designed to teach incarcerated workers skills that would give them real opportunity upon their release. It was designed to maximize production at minimal cost, and there is little evidence that Ford-Johnson’s imprisoned workers found related jobs after leaving prison. This was true not least because Ford-Johnson’s prison labor helped it drive out of business smaller furniture factories that employed more expensive free labor.[31]

The prospect of unemployment facing men freed from prison was also central to the story of Henry Dowdell, a “colored” man from Indianapolis who spent almost four years working for Ford-Johnson. Dowdell’s experience confirmed the daunting prospect of unemployment facing men freed from prison. Upon leaving State Prison North in 1896, he told the Indianapolis Journal that his conviction and incarceration inhibited his ability to find work more than his prison labor had taught him employable skills. He worried he would have to leave his family and friends in Indianapolis in order to find work in a place where he could conceal his imprisonment for burglary.[32]

Dowdell’s story also suggests that Ford-Johnson’s Michigan City prison shop was, to some extent, racially integrated. The Journal specifically stated that Dowdell “was not confined to the colored department” of the prison’s cell blocks, hinting at segregated housing amidst formally unsegregated labor, despite official prison reports claiming “no distinction here is made as to the color of the skin.” Yet a tell-all memoir by a white prisoner named Harry Youngman, who spent almost three years at Indiana’s southern and older state prison, detailed racism that ensured “colored” prisoners were “assigned to the hardest work inside the walls.” At the Michigan City prison, this work would have been forging barrel hoops for the Wintertbotham cooperage and bending the wood for Ford-Johnson chairs and bassinets.[33]

African Americans were over-represented at Indiana State Prison North, as was true in prisons across the country in the late nineteenth century and remains true today. In 1880 Black men made up ten percent of the prisoners in Michigan City and just two percent of the state’s population. The low statewide population was due in large part to Article 13 of Indiana’s 1851 Constitution, which banned African American settlement in the state, declared that any debts owed to African Americans did not need to be paid, and established fines for employing any “Negro or Mulatto.” Although state courts invalidated Article 13 following Congressional passage of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1866, it was not formally struck from the state constitution until 1881 and had a deleterious effect on African American population growth in the state throughout the late nineteenth century.[34]

The irony that, today, these cradles are associated with romanticized notions of enslaved motherhood and self-sufficient free family farms while their actual history reflects another kind of racially-biased unfree labor should be lost on no one, as it only again indicates the work curators, scholars, collectors, and dealers still need to do to explode mythic Colonial Revival narratives that remain embedded in museum collections and the broader antiques market.

The “cradle” in question moves the field toward these goals in at least three ways. First, its relationship to bassinets, and their connection to domestic refinement, recommends formally describing the object as a “portable bassinet” or “portable bassinet-cradle” in museum and auction catalogs. The latter appellation, though conflating discrete forms, recognizes the “cradle” term used in the patent application and period advertising material despite the object’s function as a bassinet. At the same time, inserting the term “bassinet” channels interpretations of the object away from myths of enslaved and free farm motherhood and toward more accurate conclusions centered on its expression of affordable domestic refinement.

Second, the bassinet’s fabrication by incarcerated labor presents the field with a late nineteenth-century corollary to revisions already made to attribution practices for earlier pieces. Just as recognition of the increasingly industrial and specialized labor force in earlier cabinetmakers’ shops has led scholars to attribute pieces to “the shop of” a master craftsperson, rather than simply citing the master’s name as the sole “maker,” so we should recognize the prison labor and state-sponsored system behind this bassinet and other objects with similar origins. Listing the bassinet’s maker as “Incarcerated labor at Indiana State Prison North, contracted by Ford-Johnson Company” leads with the people whom we know did the work, then pinpoints the prison “shop,” or factory site, and concludes by naming the company that oversaw the production, using a verb that indicates the state’s role in the business.[35]

This bassinet is just one example of antiques shrouding the enormous role of prison labor in industrializing America. How many other items in museum and private collections were made by prison labor? The only way to find out is to check the companies listed in catalogs as “makers” against the ones listed in state and federal prison reports. The connections may not always be direct, since the profits reaped from prison labor can also help explain collection items that might not have been made by incarcerated workers. In Ford-Johnson’s case, although business records do not survive, the timing of its move into high-end furniture produced at new Michigan City factories staffed with free workers in the 1890s (fig. 23) suggests that the company could not have developed its later Prairie Style designs (now in the collections of the Art Institute of Chicago and Metropolitan Museum of Art) without having amassed the capital required to expand by reaping exorbitant profits off prison-produced products in the company’s early years (figs. 24, 25). Though these chairs were not made by prison labor, any background context about the company as their producer would be negligently incomplete if it ignored the company’s reliance on prison labor. Indeed, as the prison contract system began to become more regulated and restricted by states other than Indiana during the early 1900s, Ford-Johnson foundered. The company’s move into finer furniture could not be sustained without the massive advantages and profits accrued from prison labor on less refined products. The company declared bankruptcy in 1913, and its assets were bought by various rivals.[36]

Finally, the company’s demise brings the bassinet’s story back to the mythic interpretive centerpieces from the Colonial Revival. Ford-Johnson ran puff pieces celebrating its own growth during the 1890s, almost reveling in concealing its labor force when the company celebrated its “greatest stroke of enterprise” and declared “very few realize how extensive a business is carried on by the firm.” But as critics of the prison labor system recognized in the 1910s, the company’s innovation and expansion were not the product of heroic ingenuity. They came off the backs of unfree incarcerated labor, a strategy made possible by a marriage of industrial capitalism and state power that denied rather than facilitated the individual mobility, freedom, and progress alleged in the dominant interpretation of this bassinet.[37]

Abner Woodward, Improvement in Cradles, US Patent 183,357, dated October 17, 1876, application filed March 7, 1876. Montpelier Argus and Patriot (Vermont), April 7, 1870. For steel coil springs, the history of which is bound up in upholstery, see Merri Ferrell, “To Supplant the Body in the Most Agreeable Manner: Nineteenth-Century Carriage Trimming,” Carriage Journal 46, no. 4 (August 2008): 208; Rufus Ogbuka Chime and Samuel I. Ukwuaba, “Design Modeling, Simulation, and Analysis: Compress Spring,” International Journal of Engineering Science and Innovative Technology 5, no. 1 (January 2016): 1.

J. S. Ford, Johnson, & Co. Price List (Chicago, 1882), p. 15, Smithsonian Trade Literature Collection, National Museum of American History, Washington, D.C.

Field Cradle, acc. 74587, Selected Highlights from the Florida Furniture Collection, Museum of Florida History, https://museumoffloridahistory.com/collections/florida-historic-

furniture/furniture, accessed December 1, 2020. “Biggest Black History Museum,” Ebony 53, no. 4 (February 1998): 62. See also “With Baby in Tow,” Midway Village Museum Collections Blog, July 18, 2011, https://midwayvillagemuseumcollections.wordpress.com/2011/07/18/with-baby-in-tow/, accessed December 1, 2020. Live Auctioneers Online Auction Catalog, lot 226, March 12, 2016, https://www.liveauctioneers.com/item/44081349_antique-slave-cradle, accessed December 1, 2020. Joe Rosson, “Wooden Cradle’s Past May Rest on the Farm,” Knoxville News Sentinel, December 28, 2011, http://archive.knoxnews.com/entertainment/life/joe-rosson-wooden-cradles-past-may-rest-on-the-farm-ep-402057218-357304041.html, accessed December 1, 2020.

The company’s move to Michigan City is noted along with their first prison contract in the “Annual Report of the Officers and Directors of the Indiana State Prison North [1869],” in Documentary Journal of Indiana (Indianapolis: Alexander H. Conner, State Printer, 1869), p. 320.

U.S. Census Bureau, 1880 Agricultural Census, part 3, Cultural and Economic Details of Cotton Production, p. 166. Farmer’s Review, May 12, 1906. Wheat fields were already harvested by machine by the time the cradle was manufactured, and the reference to “field” use distinguishes the interpretation from use in gardens, which is more plausible though still unlikely given the cradle’s finish.

Ford-Johnson offered the item “in oak, imitation walnut, or finished in colors,” such as the blue version currently in the collection of Pittsburgh’s Heinz History Center (fig. 6). J. S. Ford, Johnson, & Co. Price List (Chicago 1882), p. 15.

Deborah Fink, Agrarian Women: Wives and Mothers in Rural Nebraska (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1992), pp. 52–69. Marilyn Irvin Holt, Linoleum, Better Babies, and Modern Farm Woman, 1890–1930 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2005), pp. 16–18. Nancy Grey Osterud, Bonds of Community: The Lives of Farm Women in Nineteenth-Century New York (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1991), pp. 115–119. Hilary Russell, “Training, Restraining, and Sustaining: Infant and Child Care in the Late Nineteenth Century, Material History Bulletin 22 (Fall 1985): 35–49. R. Ruthie Dibble, “The Hands that Rocked the Cradle: Interpretations in the Life of an Object,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2012), pp. 1–23.

Provenances of the examples comprising this study’s sample are in the table below. Allexamples were donated by local residents, though the Nebraska donors cited their ancestors’original purchase of the cradle while living in Illinois, and the Floridadonor’s birth in 1890(while the cradle ceased production in 1892) suggests his parents may have purchased it for hisolder brothers, who were born in Ohio prior to the family’s move to Florida in the late 1880s. References to donor descriptions of the item come from accession files carrying the accessionnumbers listed.

For Snowden, see Gopsill’s Philadelphia City Directory (Philadelphia: James Gopsill’s Sons, 1885–1898). Philadelphia Times, September 20, 1891.

For the evolution of the term “field cradle” from scythe to baby furniture, see Sacramento Daily Record-Union, October 12, 1889; Newtown Bee (Connecticut), May 1, 1901; Lebanon Daily News (Pennsylvania), April 8, 1949; Hanover Evening Sun (Pennsylvania), September 6, 1966; Cincinnati Enquirer, November 30, 1969; Greenfield Daily Reporter (Indiana), October 25, 1973; Pittsburgh Press, November 11, 1973; Hamilton Journal-News (Ohio), September 26, 1973; Atlanta Constitution, June 1, 1975; Tipton Tribune (Indiana), April 10, 1978. For the rise and persistence of the “slave cradle” appellation, see Greeley Daily Tribune (Colorado), July 12, 1975; Des Moines Register, January 21, 1979; Oklahoma City Daily Oklahoman, May 31, 1979; Marysville Journal-Tribune (Ohio), July 13, 1988; North Hills News Record (Pennsylvania), February 10, 1989; Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 20, 1995; Kenneth W. Goings, Mammy and Uncle Mose: Black Collectibles and American Stereotyping (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994), pp. 123–50.

There is copious literature on the origins of social history, but a widely accepted concise overview is Joyce Appleby, Lynn Hunt, and Margaret Jacob, Telling the Truth About History (New York: W. W. Norton, 1995), pp. 146–58.

Harvey Green, “Looking Backward to the Future: The Colonial Revival and American Culture,” in Creating a Dignified Past: Museums and the Colonial Revival, edited by Geoffrey L. Rossano (Savage, Md.: Rowman and Littlefield, 1991), pp. 1–16; William B. Rhoads, “The Long and Unsuccessful Effort to Kill Off the Colonial Revival,” in Re-creating the American Past: Essays on the Colonial Revival, edited by Richard Guy Wilson, Shaun Eyring, and Kenny Marotta (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2006), pp. 13–26.

Fritz Goro, “Speaking of Pictures: Homemade Tools Show Yankee Ingenuity,” Life 18, no. 3 (January 15, 1945): 8–10. The photo of the Woodward cradle ultimately was not published in this photo essay but is available in the Getty Life Picture Collection digital archives: https://www.gettyimages.com/collections/lifepicture. James R. Hill, “‘For the Children Out Here: Re-creating the Gardens of Mount Vernon on the Bluffs of the Missouri River in Omaha, Nebraska,” in Re-creating the American Past, pp. 290–92; Rossano, “Museums and the Colonial Revival: A Roundtable Discussion,” in Dignified Past, p. 114.

Rhoads, “Unsuccessful Effort,” p. 23. Rossano, “Roundtable,” pp. 113–14. Tipton Tribune (Indiana), April 10, 1978.

Mary Jenkins Schwartz, Born in Bondage: Growing Up Enslaved in the Antebellum South (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2009), pp. 61–73.

Mary Miley Theobald, Death by Petticoat: American History Myths Debunked (Kansas City, Mo.: Andrews McMeel, 2012), pp. 20–22, 113.

Woodward Patent 183,357. Woodward later secured a Canadian patent for a baby carriage while still residing in Shelburne Falls in 1894: Child’s Carriage, Canadian Patent 46849, issued August 13, 1894.

Karen Calvert, “Cradle to Crib: The Revolution in Nineteenth-Century Children’s Furniture,” in A Century of Childhood, 1820–1920, edited by Mary Lynn Stevens Heininger (Rochester, N.Y.: Margaret Woodbury Strong Museum, 1984), pp. 33–37, 47–53. Russell, “Training,” pp. 35–49.

Woodward Patent 183,357. Calvert, “Cradle to Crib,” pp. 56–60.

Karin Calvert, Children in the House: The Material Culture of Early Childhood, 1600–1900 (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1992), pp. 142–43. Godey’s Ladies Book (February 1880): 118.

For prices, see J. S. Ford, Johnson, & Co. Price List (Chicago, 1882), p. 15; Philadelphia Times, February 27, 1888; St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 15, 1894; Philadelphia Inquirer, December 18, 1895; Chippewa Herald-Telegram (Wisconsin), May 27, 1900. On minimal retail markup in this era, see Sears, Roebuck Catalogue, 1897 Edition (Chicago: Sears, Roebuck and Co., 1897), p. 661. See also the furniture industry trade magazine the Iron Age 24 (April 24, 1890): 675. Samuel H. Williamson, “The Annual Consumer Price Index for the United States, 1774–Present,” Measuring Worth, http://www.measuringworth.com/uscpi/, accessed December 1, 2020.

Although bentwood has had a long history in Anglo-American furniture, dating back to colonial-era Windsor chairs, industrial-scale production and bending thicker rails of solid wood only emerged from the Austrian furniture maker Michael Thonet in the 1850s and were developed in the U.S. by Henry I. Seymour around 1870 in Troy, New York, not far from Abner Woodward’s home in western Massachusetts. Derek E. Ostergard, “Before Industrialization: Bent Wood and Bent Metal in the Hands of the Craftsman,” in Bent Wood and Metal Furniture, 1850–1946, edited by D. Ostergard (New York: American Federation of Arts, 1987), pp. 1–32; Allesandro Alverà, “Michael Thonet and the Development of Bent-Wood Furniture: From Workshop to Factory Production,” in Bent Wood and Metal Furniture, pp. 33–52; Barry R. Harwood, “Two Early Thonet Imitators in the United States: The Henry I. Seymour Chair Manufactory and the American Chair-Seat Company,” Studies in the Decorative Arts 2, no. 1 (October 1994): 92–113.

Glen A. Gildemeister, “Prison Labor and Convict Competition with Free Workers in Industrializing America, 1840–1890” (PhD diss., Northern Illinois University, 1977), 52.

Second Annual Report of the Commissioner of Labor: Convict Labor (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1887), pp. 124–32, 201. For Ford-Johnson’s annual prison labor contracts, see the “Annual Report of the Officers and Directors of the Indiana State Prison North,” published in the state General Assembly’s Documentary Journal of Indiana every year from 1869–1913, Indiana State Library.

Rebecca M. McLennan, The Crisis of Imprisonment: Protest, Politics, and the Making of the American Penal State, 1776–1941 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008), pp. 56–93. Second Annual Report, p. 201. “Annual Report, State Prison North,” 1869, p. 314; 1885, p. 36; 1896, p. 16.

For the Congressional contract, see Frankfort Weekly News (Kentucky), July 11, 1908; and September 5, 1908. The Senate Office Building contract fell through in the end, though a similarly-priced contract furnished the Kentucky Capitol Building. For the annual savings, multiply the $1.18 savings in the average hourly rate by 48 hours per week (six days per week at eight hours per day—free workers in Indiana noted that prisoners achieved the eight-hour day while they still worked ten), then multiply that total by 52 weeks to reach the annual savings per worker. Then multiply by 100, which was the lowest number of inmates contracted to Ford-Johnson during the period when the bassinets were made: $1.18 x 48 x 52 x 100 = $294,528. This figure is probably low, since companies regularly worked prisoners longer than formally contracted. Additionally, in some years Ford-Johnson contracted up to 200 workers, a number that would double the total year’s savings on labor. For hours, see Perry R. Clark, “Barred Progress: Indiana Prison Reform, 1880–1920” (MA thesis, Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis, 2008), 62. For the other quotations, see Julian Leavitt, “Something for Nothing,” American Magazine (July 1911): 351–360; Indianapolis Journal, April 22, 1899. Second Annual Report, pp. 193–96.

Second Annual Report, pp. 200–15. See note 8 above for the geographic location and movement of the families known to have owned examples in this study’s sample. Forty thousand is not such a large number as to correspond with the number on the market and in museums today. It seems that an unusual percentage of these bassinets were saved by families, perhaps because of their unique form (and maybe because of associations of quaint innovation absorbed from the Colonial Revival).

McLennan, Crisis, pp. 103–4. Alex Lichtenstein, Twice the Work of Free Labor: The Political Economy of Convict Labor in the New South (New York: Verso, 1996), pp. 43–46. See also Douglas Blackmon, Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II (New York: Anchor Books, 2008), and the accompanying PBS documentary of the same name.

“Annual Report, State Prison North,” 1885, p. 6; 1896, pp. 39–40. McLennan, Crisis, p. 69.

Fort Wayne Daily News (Indiana), February 5, 1884. For a similar description of Ford-Johnson’s physical abuse of prisoners in Connecticut, see Paper Makers’ Journal 11, no. 1 (December 1911): 6. For fires suggestive of arson by prisoners, see Indianapolis News, September 17, 1904; Indiana State Sentinel, May 25, 1887.

McClennan, Crisis, pp. 63–68, 114. Muncie Evening Press (Indiana), July 7, 1911. This de-skilling and market domination came in direct contrast to stated state policy, as noted in the National Anti-Convict-Contract Association’s Proceedings of the National Convention (Chicago: National Anti-Convict-Contract Association, 1886), pp. 53–54.

Indianapolis Journal, October 13, 1896.

Ibid. “Annual Report of the Officers and Directors of the Boys Reformatory,” Documentary Journal of Indiana (Indianapolis: W. M. Burford, 1890), p. 31. J. H. Banka [i.e., Harry Youngman], State Prison Life: By One Who Has Been There (Cincinnati: C.F. Vent, 1871), p. 200.

“Constitution of 1851,” Constitution Making in Indiana, 2 vols. (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Commission, 1916), 1:295; 2:187–88. Campbell Gibson and Kay Jung, “Historical Census Statistics on Population Totals by Race, 1790 to 1990,” Working Paper 56 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Population Division, 2002), p. 47.

Donna-Belle Garvin, “Reading the Evidence: The Challenge of Furniture Documentation,” Catalog of Antiques and Fine Art (Summer 2002): 162–70.

Indianapolis Star, April 21, 1912; The Ohio Nisi Prius Reports (Cincinnati: Ohio Law Reporter Company, 1915), pp. 513–24. As the Court report notes, Ford-Johnson had become a corporation in 1900 and had been managed by Cincinnati businessman and politician John B. Cox since 1910. The actual bankruptcy filing took place in Indiana, but the State of Ohio later brought suit against Cox for lending money to Ford-Johnson from a Cincinnati bank he also managed; that suit traces the company’s downfall.

American Cabinetmaker and Upholsterer, April 25, 1890, pp. 16–17; Furniture Journal, March 11, 1907, pp. 50–52.