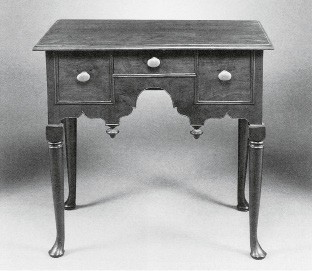

Dressing table attributed to Christopher Townsend, Newport, Rhode Island, ca. 1745. Mahogany with tulip poplar. H. 29 3/4", W. 34 1/8", D. 20 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

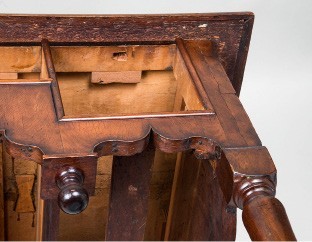

Detail of the drawer dovetailing of the dressing table illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

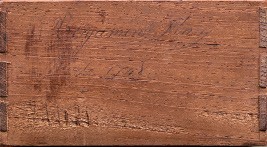

Detail of the B inscribed on a drawer of the dressing table illustrated in fig.1. (Photo, Erik Gronning.)

Detail of the B inscribed on interior of the case of the dressing table illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Erik Gronning.)

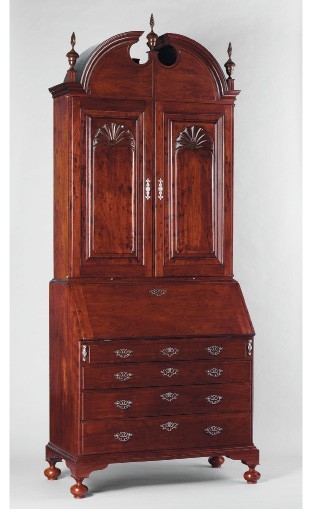

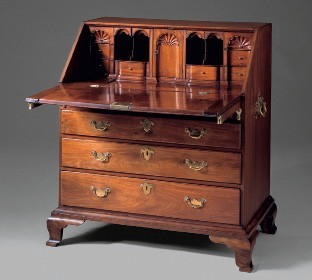

Christopher Townsend, desk-and-bookcase, Newport, Rhode Island, ca. 1750. Mahogany. (Private collection; photo © Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

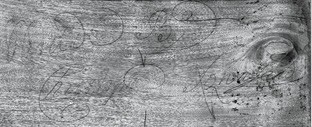

Detail of the inscription “Made by Christopher Townsend” on the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 5. (Photo, Charlotte Hale, Sherman Fairchild Paintings Conservation Center, Metropolitan Museum of Art; image © Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Detail of the B inscribed on the high chest originally owned by Governor Gideon Wanton. (Photo, Erik Gronning.)

Detail of the underside of the skirt of the dressing table illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the leg of the dressing table illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

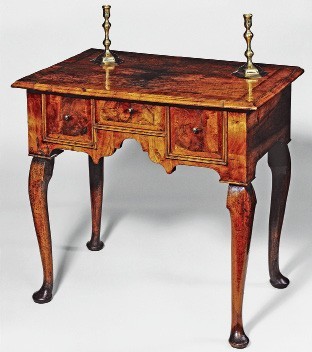

Dressing table, England, 1715–1730. Walnut, oak, and deal. (Photo, Apter-Fredericks.)

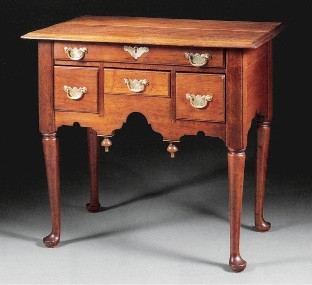

Dressing table, southeastern Virginia, 1735–1745. Walnut with yellow pine and tulip poplar. H. 28 3/16", W. 33 1/8", D. 19 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Dressing table, New Jersey, 1740–1760. Walnut. H. 30 5/8", W. 34 1/2", D. 20 1/2". (Courtesy, Christie’s.)

Tea table, Newport, Rhode Island, ca. 1750. Mahogany. H. 25 1/2", W. 25 1/4", D. 21". (Courtesy, Sotheby’s.)

Drop-leaf table, Woodbury, Connecticut, 1760–1780. Cherry. H. 26 3/4";

40 1/8" x 36 1/2" (open). (Private collection; photo, Edward S. Cooke Jr., Fiddlebacks and Crooked-backs: Elijah Booth and Other Joiners in Newtown and Woodbury, 1750–1820 [Waterbury, Conn.: Mattatuck Historical Society, 1982], fig. 21.)

Dressing table, probably Newport, Rhode Island, 1730–1740. Walnut with white pine and poplar. H. 28 7/8", W. 34 3/4", D. 21 1/8". (Lyman Allyn Art Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Dressing table, Newport or East Greenwich, Rhode Island, 1705–1735. Maple, maple veneer, and walnut with white pine. H. 28 1/2", W. 35 1/2", D. 23 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the leg of the dressing table illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the leg square and case of the dressing table illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Erik Gronning.)

Detail of the drawer dovetailing of the dressing table illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the underside of the dressing table illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the chalk marking on a drawer of the dressing table illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Erik Gronning.)

Detail of a chalk mark on the back of the dressing table illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Erik Gronning.)

Chest of drawers, Newport, Rhode Island, 1715–1735. Maple. H. 37 1/4", W. 36 3/4", D. 20". (Courtesy, Whitehorne House Museum, Newport Restoration Foundation.)

Detail of a chalk mark on the exterior back of a drawer of the chest of drawers illustrated in fig. 23. (Art & Industry in Early America: Rhode Island Furniture, 1650–1830, edited by Patricia E. Kane et al. [New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Art Gallery, 2016)], p. 448, fig. 8.)

Dressing table, Newport, Rhode Island, ca. 1740. Walnut. H. 30", W. 33 3/4", D. 20 1/2". (Courtesy, Sotheby’s.)

Dressing table, Newport, Rhode Island, ca. 1740. Walnut with maple. H. 30", W. 33", D. 21". (Photo reproduced from Wallace Nutting, Furniture Treasury, vol. 1 [New York: MacMillan Company, 1948], no. 398.)

Dressing table, attributed to Christopher Townsend, Newport, Rhode Island, ca. 1750. Mahogany with maple and yellow poplar. H. 30 1/4", W. 36", D. 22". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Christie’s.)

Detail of the drawer dovetails of the dressing table illustrated in fig. 27. Photo, Robb Quinn.)

Detail of the B inscribed on the back of a drawer of the dressing table illustrated in fig. 27. (Photo, Jonathan Prown.)

Detail of the glue blocks securing a leg of the dressing table illustrated in fig. 27. (Photo, Robb Quinn.)

Christopher Townsend and John Townsend, high chest of drawers, Newport, Rhode Island, ca. 1755. Mahogany with white pine and yellow poplar. H. 83 5/8", W. 40 1/2", D. 22 1/4". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The chest retains its original cast brass hardware and finish.

Desk, attributed to Christopher Townsend, Newport, Rhode Island, ca. 1750. Mahogany with tulip poplar, chestnut, cereal, and white pine. H. 42", W. 36 1/2", D. 22". (Private collection; photo, Sotheby’s.)

Desk, attributed to Christopher Townsend, Newport, Rhode Island, 1748. Mahogany with mahogany, poplar, birchwood, and cedar. H. 41 3/4", W. 38 1/8", D. 22 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inscription “Made 1748” on the desk illustrated in fig. 33. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inscription “Benjamin Almy | Made 1748” on the desk illustrated in fig. 33. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the interior of the desk illustrated in fig. 33. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the prospect door of the desk illustrated in fig. 33. (Photo, Erik Gronning.)

Detail of the left sliding lock of the top long drawer of the desk illustrated in fig. 33. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Christopher Townsend, desk, Newport, Rhode Island, ca. 1750. Mahogany, cedrela, and tulip poplar. H. 37 1/4", W. 35 5/8", D. 20 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

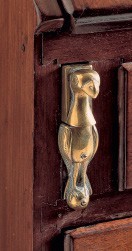

Detail of the brass mount on the left fallboard support of the desk illustrated in fig. 33. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the silver mount on the left fallboard support of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 5. (Courtesy, Sotheby’s.)

Detail of the brass mount on the left fallboard support of the desk illustrated in fig. 32. (Courtesy, Sotheby’s.)

SINCE THE PUBLICATION OF “The Early Work of John Townsend in the Christopher Townsend Shop Tradition” in the 2013 volume of American Furniture, the authors have discovered additional pieces that expand Christopher’s oeuvre. Although all of these objects have structural, procedural, and stylistic features that relate directly to his larger body of work, some pieces exhibit designs and details not previously associated with him. This essay examines that new work and shows how it relates both to Christopher’s more conventional furniture and, in some instances, to earlier forms and stylistic influences.[1]

A dressing table sold by Nathan Liverant and Son of Colchester, Connecticut, at the 2014 Winter Antiques Show displays many hallmarks of Christopher Townsend’s work and represents a design not previously associated with him (fig. 1). Aside from being advertised by Dean Wilson Antiques in the May 1974 issue of Antiques, the history of the dressing table is unknown. Like many pieces documented and attributed to Christopher’s shop, the dressing table is made of dense, figured mahogany and tulip poplar; has drawers with fine, evenly spaced dovetails (fig. 2); has drawer sides with rounded upper edges; and features large calligraphic chalk letters on the drawer backs (the flanking drawers are denoted A and B [fig. 3] and the interior back of the case is marked B [fig. 4]). The marks on the backs of the drawers were intended to differentiate them, whereas the letter on the case back is a finishing mark and was inscribed before construction. The finishing mark is identical to the B in the graphite inscription “Made By Christopher Townsend” on a desk-and-bookcase that descended in the Appleton family of Massachusetts (figs. 5, 6) and very similar to the B on the drawer of a high chest owned by Governor Gideon Wanton and attributed to Christopher and John Townsend (fig. 7). As the authors’ 2013 article demonstrated, those craftsmen had very distinctive handwriting. In sum, the structural details and inscribed marks of the dressing table illustrated in figure 1 leave no doubt that it is from Christopher’s shop.[2]

The edges of the table’s front and side skirts are embellished with cock-beading secured with closely spaced rose-headed nails (fig. 8). This feature, while commonplace on baroque high chests and dressing tables with stretchers and turned legs and feet, is rare on later forms. Although patrons occasionally commissioned out-of-date designs, the dressing table’s strong stylistic relationship to an earlier example (see fig. 15) suggests that it predates Christopher’s slipper cabriole leg forms.

The upper squares of the legs are shouldered to fit inside the frame and secured with glue blocks in typical Newport fashion (figs. 8, 9). Like the applied cock-beading on the rails, this method of leg attachment represents a holdover from baroque dressing tables and high chests. Newport cabinetmakers used this technique on high chests and dressing tables throughout the eighteenth century because it required less wood and labor than conventional mortise-and-tenon joinery. Related construction can be observed on English tables dating from the early eighteenth century (fig. 10), which may have been the original source of Christopher’s design.[3]

Although overt English design is rarely manifest in eighteenth-century Newport furniture, the dressing table illustrated in figure 1 is an exception to the rule. Similar dressing tables were made in other areas of colonial America where English stylistic influences were prevalent (figs. 11, 12). Turned elements comparable to those on the legs of Townsend’s dressing table also occur on other furniture forms, as evidenced by the Newport tea table shown in figure 13, several dining tables made in southeastern Virginia, a New Jersey dining table that descended in the Frelinghuysens family, and a dining table thought to have been made in Woodbury, Connecticut (fig. 14). As discussed in the authors’ 2013 article, Newport furniture design had a profound impact on furniture made in nearby coastal Connecticut.[4]

The object most closely related to Townsend’s dressing table is an earlier example that reputedly belonged to Connecticut governor Gourdon Saltonstall (1666–1724) before being acquired by Ezekiel Fox (1756–1844) of New London, Connecticut, around 1790 (fig. 15). The latter object’s probable date of manufacture precludes ownership by Saltonstall, but it is possible that the piece was commissioned by an earlier member of Ezekiel’s family. His grandparents Samuel (1687–1752) and Mary (Fanning) Fox (1686–1771) would have been of the right age.[5]

The design, construction, and woods of the Fox dressing table are consistent with baroque furniture made in Rhode Island while differing from contemporaneous Connecticut work. As furniture scholar Dennis Carr has noted, Rhode Island became an important center for cabinetmaking and shipbuilding in the first quarter of the eighteenth century, at a time when the mercantile elite was prospering. Local craftsmen were capable of meeting the increasing demand for high-quality workmanship and innovative design as a fall-front desk that descended in the Child family of Warren, Rhode Island, suggests. Like their counterparts in England, Boston, and other furniture-making centers, Rhode Island cabinetmakers became adept in working with thinly cut burl and root veneers (see fig. 10). This practice fell out of fashion by the 1740s in favor of solid wood.[6]

The Fox dressing table is representative of the stylistic shift that occurred in Rhode Island during the mid- to late 1730s as the baroque details were being supplanted by new styles emerging during the reigns of Queen Anne and George I. Its case construction, skirt shape, applied cock beading, and veneering have antecedents in earlier work from the Newport vicinity (fig. 16), but, as with Townsend’s early example, the maker incorporated turned legs with pad feet (fig. 17). Both craftsmen endeavored to make it appear that the cock-beading on the skirt returned across the faces of the legs. The maker of the Fox table carved a bead on the shouldered edge, whereas Townsend relied solely on a slight offset—the legs are slightly proud of the case front and sides—to achieve a similar effect. Both techniques appear to have evolved from the applied plaques directly above the legs of baroque high chests and dressing tables, although the carved method is earlier and more visually successful than the offset one (fig. 18). The legs on the Fox dressing table were designed to be more offset than Townsend’s to further enhance their carved beading.

While both dressing tables reflect the same design influence, the construction of the Fox example is significantly less refined than Townsend’s. The drawers of the Fox dressing table have thick sides and broad dovetails that extend through the front core (fig. 19). Framing the drawer openings are broad, bead moldings, an embellishment simpler than the double bead used by Christopher and many contemporaneous and earlier regional craftsmen. The maker of the Fox example shaped the vertical glue blocks so they would be hidden behind the skirt (fig. 20), although not to the degree seen on those of the Townsend dressing table.

Distinctive chalk marks that resemble Ds but could also be cursive Ss are on the back of the case and all of the drawers of the Fox dressing table (figs. 21, 22). These inscriptions are not found in the work of Christopher, Job, or John Townsend and represent finishing marks from a different shop. Similar chalk markings occur on a mahogany dressing table with a shell-carved skirt and slipper feet and on a maple and birch chest of drawers with ball feet (figs. 23, 24). The unidentified craftsman responsible for this group of case pieces has been identified as “Joiner D” by Patricia Kane. In addition to the shared markings, the Fox dressing table and the chest illustrated in figure 23 have similar dovetails, drawer sides with a chamfered edge, and side dovetails that extend through the drawer backs. A birch chest of drawers with ball feet, a mahogany slant front desk, and the maple upper section of a high chest made in Newport also have related chalk markings and may represent the work of the same maker.[7]

Two dressing tables sharing characteristics with the Fox table and the dressing table attributed to Christopher Townsend are known (figs. 25, 26). Unfortunately, the authors were unable to examine these objects to determine if they are by either maker. With their baroque style cases and tapered legs ending in pad feet, these four dressing tables are the only known Rhode Island examples of their form. Though not prevalent, this form was an option offered by several Rhode Island cabinetmakers as evidenced by this small group of related dressing tables. They collectively represent a common Rhode Island shop tradition, where multi-generational families of cabinetmakers worked closely together sharing designs and shop practice.[8]

The slipper-foot dressing table illustrated in figure 27 is another recent addition to Christopher Townsend’s oeuvre (fig. 27). Its materials, drawer dovetailing, and calligraphic markings denoting drawer placement—A, B, and C, in graphite on the backs—are consistent with other pieces documented and attributed to his shop (fig. 28). The B in particular is clearly by Townsend’s hand (fig. 29). As on other Townsend pieces, the legs are secured with glue blocks, but ones made of mahogany rather than a softwood (fig. 30).[9]

The design of the dressing table follows that of the lower case of a high chest signed and dated in graphite on the bottom board of the upper case: “Christopher Townsend made 1748.” The chest was originally owned by William Van Dearness of Middletown, Connecticut. Both case pieces have skirts with cyma curves centering a pendant, or “drop,” and cabriole legs with slipper feet. A very similar lower case occurs on a high chest originally owned by George Hussey (died 1782) of Nantucket. That object has Christopher Townsend’s signature calligraphic M and drawer designation system. Another high chest originally owned by Samuel Ward (1725–1776), governor of Rhode Island, with the signatures of Christopher and John Townsend also displays a closely related lower case (fig. 31).[10]

Brasses identical to those on the dressing table illustrated in figure 27 are found on the Hussey high chest, a mahogany desk attributed to Christopher Townsend (fig. 32), and a high chest signed by Christopher and John and originally owned by Thomas (1731–1817) and Sarah (Richardson) Robinson of Newport. This hardware was undoubtedly imported, although some of the brass facings on the fallboard supports of Christopher’s desks were cast locally.[11]

The desk illustrated in figure 33 has a history of descent in the Thaxter family of Newtownville, Massachusetts. Levi Lincoln Thaxter (1824–1884), a Harvard graduate and lawyer, and his wife Celia (Laighton) (1835–1894) were the first owners in the Thaxter family. The desk is inscribed in pen “Made 1748” on a drawer back and “Benjamin Almy | Made 1748” on a drawer behind the prospect door (figs. 34, 35). The latter inscription likely refers to Captain Benjamin Almy (1724–1819), who was born in Newport on December 16, 1724, to John Almy (1692–1735) and Anstiss Ellery (1697–1769). A Newport merchant, Benjamin owned Benjamin Almy and Company as well as at least one sloop, Adventure, which made voyages to the West Indies. He served as commander of privateer General Johnston of Newport in 1756 and 1760. During the Revolution, he served under the command of General John Sullivan. A member of Newport’s mercantile elite, Benjamin Almy was likely the original owner of this desk. He was related through marriage to Christopher Townsend, whose mother, Catherine (born 1673), was a member of the Almy family. Catherine (Almy) Townsend and Benjamin Almy’s grandfather, William Almy (1665–1747), were first cousins. Catherine’s father, Job Almy (1693–1684), and William’s father, Christopher Almy (1631–1713), were brothers. Benjamin Almy patronized other members of the Townsend family, including Job Townsend Jr., from whom he purchased a tea board for £6.10 on October 28, 1762. His family owned other pieces of Newport furniture, including a pair of sabicu side chairs made for his daughter Katharine (1770–1863) and her husband, Edmund Trowbridge Ellery (1763–1820), when they married in 1792. Inscribed “Amy” on both slip seats (likely a phonetic spelling of Almy), the chairs were made from wood grown on the Nassau, West Indies, plantation of Katharine’s brother, James Almy (born 1772).[12]

The Almy desk is made of mahogany and has mahogany, cedar, birch, and tulip poplar secondary woods. To provide color contrast, Townsend used two types of mahogany. This unusual feature is most apparent in the desk interior, where the shell-carved upper drawers are lighter than the drawers below (fig. 36). The prospect door is unique in being made of three pieces of mahogany—two used for the face and one for the core—but all other aspects of the desk’s construction are consistent with Townsend’s work. The drawer dovetails are precise and evenly spaced, the upper edges of the drawer sides are rounded, and the shells match those on other pieces documented and attributed to Christopher Townsend (fig. 37). The design of the desk interior is unusual, displaying tiers of drawers rather than a combination of drawers and compartments. Benjamin Almy, the original owner, likely specified that plan. To prevent access to the desk well, the top long drawer has sliding wooden locks, a feature common on Rhode Island case examples (fig. 38).[13]

Markings on the Almy desk provide the final confirmation that the piece is from Townsend’s shop. The bottom board of the case is inscribed “Bottom,” with a calligraphic B that is very similar to the B on the Appleton desk-and-bookcase (figs. 5, 6). This B was also used as a finishing mark on the Wanton high chest of drawers (fig. 7) and a mahogany desk signed “Made by C T” that descended in the Simon Pease family of Newport (fig. 39).[14]

The fallboard supports of the Almy desk are faced with brass birds (fig. 40) cast from a pattern likely made by Christopher Townsend. Similar birds carved in wood occur on the staircase frieze of his house on Bridge Street in Newport. Most of the cast examples are made of brass (figs. 40, 42), although the facings on the supports of the Appleton desk-and-bookcase are silver and bear the mark of Newport silversmith Samuel Casey (1723–ca. 1773) (fig. 41). The method used to attach these facings is identical; the bird head is secured to the support and the body to the case below. The eyes of the bird heads were separate components that were soldered in place. Although typically made of copper alloy, those on the Appleton desk-and-bookcase are agate.

The furniture illustrated and discussed in this article adds to the known body of Christopher Townsend’s work, but, like all new scholarship, it also serves as a foundation for further study. The relationship between the early dressing table attributed to his shop and the related veneered example illustrated in figure 15 raises questions about apprenticeship and the origin of designs and construction methods that later became standard Newport work. It is both remarkable and exciting that new pieces continue coming to light that add to our body of knowledge.

Erik Gronning and Amy Coes, “The Early Work of John Townsend in the Christopher Townsend Shop Tradition,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2013), pp. 2–49.

Dean Wilson Antiques advertisement, Antiques 105, no. 5 (May 1974): 1022; ibid. 107, no. 5 (May 1975): 840. This object is included in the Rhode Island Furniture Archive at the Yale University Art Gallery, RIF1917. This desk was thought to have been commissioned by the Reverend Nathaniel Appleton (1693–1784) and his wife, Margaret (Gibbs) (1699–1771) of Cambridge, Massachusetts, but research by Martha Willoughby suggests that it entered the Appleton family through the marriage of Sarah Fayerweather to John Appleton in 1807. The original owners were most likely Sarah’s aunt, Mary Fayerweather, and her husband, Nathan Carpenter, of Newport. See Art & Industry in Early America: Rhode Island Furniture, 1650–1830, edited by Patricia Kane et al. (New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 2016), pp. 205, 209.

The English dressing table is illustrated and discussed in Adam Bowett, Early Georgian Furniture 1714–1740 (Woodbridge, England: Antiques Collectors Club, 2009), pp. 238–9, 5.70. Similar legs occur on other examples of English furniture, including two walnut dressing tables made ca. 1740 and two mahogany drop leaf dining tables made ca. 1750 (Ibid., pp. 239, 5.71; 256, 5.73; and 257, 5.1030).

For more on the Virginia dressing table illustrated in fig. 11, see MESDA object database, https://mesda.org/item/object/table-dressing/15340/. The dressing table illustrated in fig. 12 sold at Christie’s, Important American Furniture, Silver, Prints, Folk Art and Decorative Arts, January 21–22, 1994, sale 7820, lot 346. The Newport tea table sold at Sotheby’s, Important Americana, New York, October 4, 2007, lot 133. For Virginia dining tables with related turnings, see https://mesda.org/item/object/table-dining/15325/; https://mesda.org/

item/object/table-dining/15324/; https://mesda.org/item/object/table-dining/15335/; https://mesda.org/item/object/table-dining/15336/. The Frelinghuysens table is illustrated in The Pulse of the People: New Jersey 1763–1789 (Trenton: New Jersey State Museum, 1976), no. 255. The Connecticut table is illustrated in Edward S. Cooke Jr., Fiddlebacks and Crooked-backs: Elijah Booth and Other Joiners in Newtown and Woodbury, 1750-1820 (Waterbury, Conn.: Mattatuck Historical Society, 1982), fig. 21. For a discussion of Newport influence on furniture made in coastal Connecticut, see Gronning and Coes, “The Early Work of John Townsend,” pp. 10–11.

The dressing table has a label recounting its history: “This Table was originally the property of Gov Gordon Salstonstall who died in 1725. About 1790 it came into the possession of Ezekiel Fox_ belonged afterwards to his daughter Rachel W Wilson and was by her given (May 1859) to Nathan Belcher. After the death of Nathan Belcher who was my grandfather it came to his only son my father, William Belcher and was left to me in his will. Annette Talbot Belcher Adams. October the tenth 1941. Plainfield, N.J.” Ezekiel Fox (1756–1844) was the son of Samuel (1724–1809) and Prudence (Turner) Fox (1732–1823) of New London, Connecticut. He married Susanna Childs (1770–1850), and they had three children, including Rachel Wright Wilson (1793–1859). The dressing table is illustrated in Minor Myers Jr. and Edgar Mayhew, New London Furniture, 1640–1840 (New London, Conn.: Lyman Allyn Museum, 1974), p. 18, no. 8.

See Dennis Carr, “A Lively Experiment: Early Furniture Making of the Narragansett Bay Region, 1636–1740,” in Art & Industry in Early America: Rhode Island Furniture, 1650–1830, edited by Patricia E. Kane et al., (New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 2016), pp. 16–21. The fall-front desk with a history in the Child family is illustrated on p. 17, fig. 7.

For more on “Joiner D,” see Rhode Island Furniture Archive RIF2163, RIF1537, RIF2079, RIF208, and RIF6570, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Conn.; and Kane et al., eds., Art & Industry, p. 448.

One dressing table sold at Sotheby’s, Important Americana, New York, January 26–28, 1989, lot 1392; the other is illustrated in Wallace Nutting, Furniture Treasury, 3 vols. (New York: MacMillan Company, 1948), 1: 398.

This dressing table sold at Christie’s, Important American Furniture, Folk Art and Silver, New York, January 24, 2020, lot 202. For similar sequential lettering in graphite, see Gronning and Coes, “The Early Work of John Townsend,” p. 19, fig. 38. This desk descended in the Simon Pease family of Newport and is signed “Made by C T.”

Gronning and Coes, “The Early Work of John Townsend,” p. 28, fig. 63; p. 29, fig. 65. The high chest illustrated in fig. 31 is signed “Christopher,” in graphite, on the exterior back of the right upper drawer and “John To,” in graphite, on the exterior bottom of the bottom drawer of the upper case. Faint names, including “Christopher” and “John,” in graphite, are on the exterior back of the bottom drawer of the upper case.

Ibid., p. 21, fig. 44; p. 23, fig. 48, p. 23. The high chest is in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

The desk sold at Christie’s, Important American Furniture, Folk Art and Decorative Arts, October 8, 1997, New York, lot 57. It descended from Levi and Celia Thaxter to their son, Roland Thaxter (1858–1932), and next to his daughter, Katherine (1890–1987), who left it to her great nephew, Eliott Hubbard IV, of New York, New York. Benjamin Almy married Sarah Coggeshall (1721–1756), daughter of Thomas Coggeshall (1687–1762) and Sarah Lancaster (ca. 1698–1731), in 1751; after her death he married Mary Gould (1735–1808), daughter of James Gould II (1696–1768) and Mary Rathbun (1700–1779), on October 22, 1762, at Trinity Church in Newport. This transaction is recorded in Job Townsend Jr.’s daybook. See Martha H. Willoughby, “The Accounts of Job Townsend, Jr.,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1999), p. 135. For the chairs, see Nancy Goyne Evans, “A Pair of Distinctive Chairs from Newport, Rhode Island,” Antiques 149, no. 1 (January 1994): 186–92; and Nancy E. Richards and Nancy Goyne Evans, New England Furniture at Winterthur (Winterthur, Del.: Winterthur Museum, 1997), pp. 80–1, no. 46.

The interior drawers are numbered in chalk 1–6 to the left of the prospect door, 7–9 behind prospect door, and 10–15 to the right side of the prospect door.

See Gronning and Coes, “The Early Work of John Townsend,” p. 19, fig. 38.