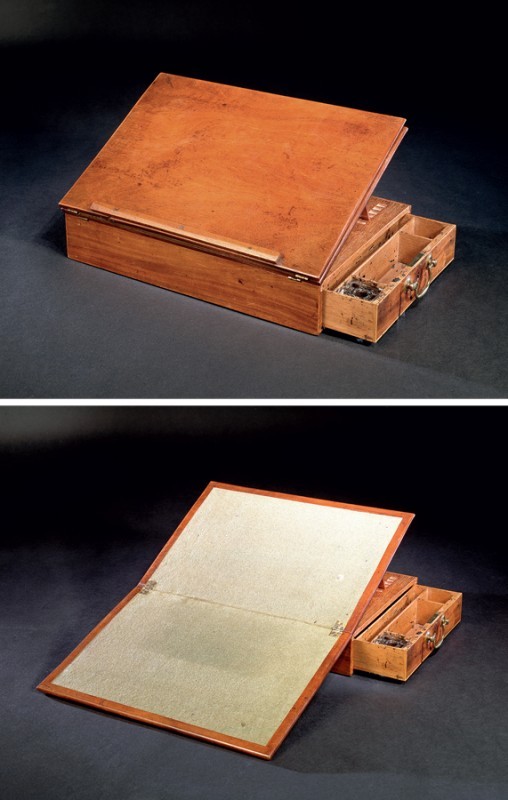

Writing box, shop of Benjamin Randolph, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1775. Mahogany. H. 3 1/2" (closed), W. 14 3/8", D. 9 3/4". (Courtesy, Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of History.) The provenance is Thomas Jefferson; by gift to Joseph Coolidge Jr.; by descent to J. Randolph Coolidge, Algernon Coolidge, Thomas Jefferson Coolidge, and Ellen Coolidge Dwight; by gift to the United States and transmitted by President Rutherford B. Hayes to Congress in 1880.

Francis Alexander, Ellen Wayles Randolph Coolidge, Boston, Massachusetts, 1836. Oil on canvas. 17" x 13 3/4". (Courtesy, Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello.)

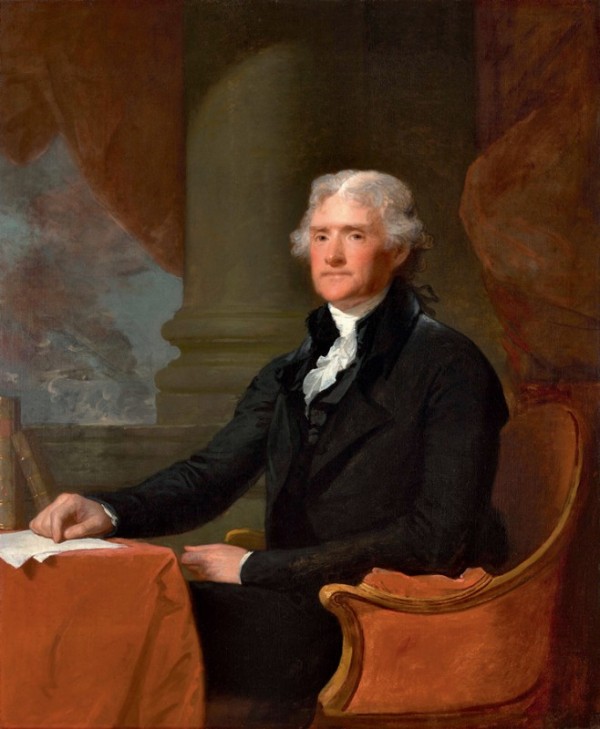

Gilbert Stuart, Thomas Jefferson, Boston, Massachusetts, ca. 1805. Oil on canvas. 48 1/2" x 39 7/8". (Courtesy, Bowdoin College Museum of Art.)

Charles Willson Peale, Benjamin Randolph, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1775–1780. Watercolor on ivory. 1 1/4" x 1". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art; gift of Mr. and Mrs. Timothy Westbrook.) This miniature descended in the family of donor Timothy Westbrook through Francesca Gualdo Ford (1767–1852), who at age five became a ward of Benjamin Randolph after both of her parents died in Philadelphia. She subsequently married the Hon. Gabriel H. Ford of Morristown, N.J., at Randolph’s house in Burlington on June 25, 1790. According to Westbrook, Randolph gave her the miniature at that time. He inherited the portrait in 1948 from his grandmother, Frances Gualdo Greeley Strong. The miniature is mounted in a locket that may have been made by Philadelphia goldsmith and silversmith William Ball (1729–1810). On August 1, 1775, Randolph charged him £12.12, and five days later Ball settled part of his debt with a gold locket valued at £.1.7. (Randolph Ledger, p. 226, New York Public Library.)

John Trumbull, The Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1776, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1786–1820. Oil on canvas. 20 7/8" x 31". (Courtesy, Yale University Art Gallery). While staying with Jefferson in Paris in 1786, Trumbull wrote, “I began the composition of the Declaration of Independence, with the assistance of [Jefferson’s] information and advice” (“The Declaration of Independence, by John Turnbull,” AmericanRevolution.org, https://www.americanrevolution.org/ decsm.php#anchor974003).

Writing stand, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1765. Mahogany. H. 63 1/2", W. 30 1/2", D. 30 1/2". (Courtesy, Library Company of Philadelphia.)

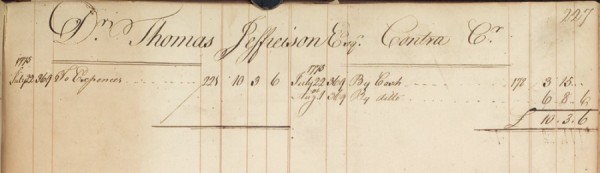

Entry for Thomas Jefferson in the ledger of Benjamin Randolph, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1775. (Courtesy, New York Public Library.)

Windsor armchair (modified), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1785–1795. Maple, tulip poplar, and unidentified ring-porous hardwood. H. 43 1/2", W. 30", D. 33 1/2". (Courtesy, American Philosophical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Revolving armchair from the shop of Thomas Burling, New York, New York, 1790. H. 48 1/2", W. 25 1/4", D. 24". (Courtesy, Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing the bottom of the upper section of the seat of the armchair illustrated in fig. 8. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing the top of the lower section of the seat of the armchair illustrated in fig. 8. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing one of the pulleys let into the top of the lower section of the seat of the armchair illustrated in fig. 8. The presence of white and brown paint suggests that these may be reused window pulleys. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing the metal pin and sleeve that register the seat sections of the armchair illustrated in fig. 8. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Photograph of Jefferson’s rotating Windsor armchair, in the American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, April 6, 1926.

IN 1825 THOMAS JEFFERSON bequeathed the writing box on which he wrote the Declaration of Independence to his granddaughter Ellen Wayles Randolph Jefferson and her new husband, Joseph Coolidge of Boston (figs. 1–3). She had met Coolidge, who was the son of an affluent Massachusetts merchant, when he visited Virginia in 1824. Ellen and Joseph were married in May of that year in the parlor at Monticello. Recognizing the importance of Jefferson’s desk, the Coolidge family gave it to the United States government in 1880. Now part of the Smithsonian collection, the desk is regarded as a national treasure. This essay will examine the desk and rotating Windsor chair that also is reputed to have been used by Jefferson in drafting the Declaration, for such objects are, as Joseph Coolidge said, “to be interrogated, and caressed.”[1]

Jefferson may have used his writing box when he conveyed his personal sentiments regarding that object to Eleanora in a letter he wrote at Monticello on November 14, 1825:

If then things acquire a superstitious value because of their connection with particular persons, surely a connection with the great Charter of our Independence may give a value to what has been associated with that; and such was the idea of the enquirers after the room in which it was written. Now I happen still to possess the writing-box on which it was written. It was made from a drawing of my own, by Ben. Randall, a cabinet maker in whose house I took my first lodgings on my arrival in Philadelphia in May 1776. And I have used it ever since. It claims no merit of particular beauty. It is plain, neat, convenient, and, taking no more room on the writing table than a moderate 4to. volume, it yet displays itself sufficiently for any writing.

Jefferson did not recall Benjamin Randolph’s name correctly, nor did he remember that he had lodged in the latter’s house almost a year earlier than recounted (fig. 4). This is not surprising given that the former president was eighty-two, in failing health, and drawing on a memory nearly fifty years old. Jefferson spent at least seventy-three days with Randolph between 1775 and 1776, when the Virginian traveled back and forth between Philadelphia and Monticello. The cabinetmaker also provided lodging to other prominent Virginians, including George Washington and Peyton Randolph, the president of Congress.[2]

Entries in Jefferson’s memorandum books and Randolph’s account ledger and receipt books confirm some of the information relayed in the letter to Eleanora and shed light on the events and activities that occurred during Jefferson’s sojourns in Philadelphia. In 1776 the Second Continental Congress met there to manage the war effort, make decisions about the formation of a new republic, and enlist help from France and Spain. Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert R. Livingston were appointed to a committee to prepare a declaration justifying independence from Britain (fig. 5). The task of writing that document fell on Jefferson, who chaired the committee, and he had only seventeen days to produce it. A good deal of that writing likely took place on the box made by Randolph.[3]

The writing box is a testament to Jefferson’s ingenuity and Randolph’s ability to give form and function to his patron’s design (fig. 1). It was, in a sense, Jefferson’s most constant companion. The box traveled with him to France during his tenure as ambassador, to Monticello when he returned to Virginia, and to the District of Columbia when he became president.

On June 20, 1775, Jefferson arrived in Philadelphia for the Second Continental Congress accompanied by two enslaved servants: Jesse, who drove the coach, and Richard, who was his master’s valet. Other Virginia delegates included George Washington, Patrick Henry, Benjamin Harrison, Richard Henry Lee, Peyton Randolph and Edmund Pendleton. It is not known where Jefferson and his slaves stayed the first night, but he began lodging at Randolph’s house the following day. On June 26 Jefferson paid £1.10 1/2 to hire a coach to visit Delaware attorney John Dickinson at the latter’s home, Fair Hill. Although not a member of the committee instructed to draft a “Declaration of the Causes and Necessity for Taking Up Arms,” Dickenson assisted Jefferson in the preparation of the final version. Such meetings, planned between the sessions of Congress, were often held at private residences like Dickinson’s, in taverns, or at lodgings, where attendees worked secretively at desks and tables or on boxes and other portable writing forms. Dickinson, for example, owned an unusual desk with a pillar, a claw base, and a four-sided writing surface that could be raised and lowered on that object’s threaded standard (fig. 6).[4]

Jefferson lodged at Randolph’s house from May 14–23, 1776, when the former relocated to the home of brickmaker Jacob Graff Jr. Although Jefferson claimed that he moved to cooler accommodations, the impetus for his relocation might have been the arrival of “Mrs. Washington” on May 22 and “his Eccelency [sic] General Washington” the following day. Presumably Graff’s house is where Jefferson wrote most of the Declaration of Independence.[5]

Making Jefferson’s Writing Box, 1775 or 1776?

Part of the per diem Jefferson received while in Philadelphia may have been used to pay for his writing box. His memoranda notations and Randolph’s financial records suggest that Jefferson was allotted five shillings per day while attending Congress. An exception occurred during his stay between July 8 and 28, 1775, when the allotment totaled £6.5s, £5.2s. more than any other twenty-day period (fig. 7). That overage would have been sufficient to pay Randolph for making the writing box and possibly other work as well.[6]

Randolph’s records reveal that six tradesmen—John Shepper, John Hockenh ull, John Maggs, Robert Easton, Peter Saunders, and James Lightfoot—were credited for work done for Jefferson’s account on July 22, 1775, and that payment was received seven days later. Little is known about Shepper other than recurrent work for Randolph between June 8, 1771, and July 9, 1776. Hockenhull was a cabinetmaker who arrived in Philadelphia on July 24, 1770, aboard the ship Et of Donegal, which sailed from Belfast, Ireland, and worked for Randolph until November 1776. The journeyman and his wife left Philadelphia after the British occupation, took refuge in New York, and subsequently settled in Nova Scotia. John Maggs’s tenure in Randolph’s shop extended from June 26, 1773, to May 4, 1776; Robert Eaton’s from August 4, 1774, to September 9, 1775; Peter Saunders’ from October 22, 1774, to September 9, 1775; and James Lightfoot’s from October 22, 1774, to September 9, 1775. Although it is conceivable that Randolph was involved in making the box, there is no such evidence in his records, and he seems to have supervised work more than actually doing it.[7]

Jefferson’s November 14, 1825, letter to Eleanora does not mention the year in which he acquired the box, although it does mention Randolph’s being the source of the box and his own lodging with the cabinetmaker in 1776. If Jefferson acquired the box in that year, Randolph’s accounts provide the identities of three journeymen as possible makers: John Hockenhull, who received £11.2.6 for four projects completed between April 27 and May 15, the day after Jefferson got to Philadelphia; John Shepper, who received £5.5 for four projects completed between April 27 and May 25, two days after Jefferson left; and Henry Anderson, who received £2.11.6 for four projects completed between May 4 and May 25. Regrettably, the nature of the projects and the names of the patrons who commissioned the work are not specified. Given the overage in Jefferson’s payment to Randolph for lodging in 1775, it seems more likely that the box, along with other furniture, was purchased then rather than in the following year.[8]

As Jefferson noted, his writing box is “plain, neat, convenient, and . . . [takes] no more room on the writing table than a moderate 4to. volume.” The writing platform comprises two hinged boards that can be unfolded to double the work surface (19 3/4" x 19 3/4") and raised and lowered on ratcheted supports. When the boards are folded together, the box can also serve as a reading stand with a book, pamphlet, or papers resting on the applied molding. The case is lined with green baize and fitted with a drawer partitioned for storing paper, pens, and a glass inkwell. Jefferson acknowledged that the box claimed “no merit of particular beauty,” but that it had served him well since the day he acquired it. Inside the box he wrote, “Politics as well as Religion has its superstitions. These, gaining strength with time, may, one day, give imaginary value to this relic, for its association with the birth of the Great Charter of our Independence.”[9]

Although Jefferson was clearly aware of the box’s historical importance when he offered it to Eleanora, the catalyst for his gift was the loss of the “beautiful writing desk” his enslaved joiner John Hemmings had made for her earlier. Born on April 24, 1776, John was the brother of Sally Hemmings, Jefferson’s enslaved mistress and mother to several of his enslaved children. On November 14, 1825, Jefferson wrote to Elenora:

We have heard of the loss of your baggage, with the vessel carrying it, and sincerely condole with you on it. it is not to be estimated by it’s pecuniary value, but by that it held in your affections. the documents of your childhood, your letters, correspondencies, notes, books Etc. Etc. all gone! and your life cut in two, as it were, and a new one to begin, without any records of the former. John Hemmings was the first who brought me the news . . . he was au desespoir! that beautiful writing desk he had taken so much pains to make for you! Every thing else seemed as nothing in his eye, and that loss was every thing. Virgil could not have been more afflicted had his Aeneid fallen a prey to the flames. I asked him if he could not replace it by making another? No. his eye sight had failed him too much, and his recollection of it was too imperfect. it has occurred to me however that I can replace it, not indeed to you, but to Mr Coolidge; by a substitute, not claiming the same value from it’s decorations, but from the part it has borne in our history and the events with which it has been associated . . . I will send it thro’ Colo Peyton, and hope with better fortune than that for which it is to be a substitute.[10]

Jefferson’s Rotating Windsor Armchair

Jefferson’s rotating Windsor armchair (fig. 8) has long been of interest to historians and furniture scholars, some of whom have considered its rotating mechanism to be original construction and others that the mechanism is a later modification. The history of the chair provides few substantive clues. When Jefferson passed away on July 4, 1826, the chair descended to his daughter Martha Jefferson Randolph, who in 1836 left the chair by inheritance or default to her daughter Virginia and the latter’s husband, Nicholas Trist. Nicholas subsequently gave the chair to Judge John Kintzing Kane, a family friend who helped with the storage of the Trists’ possessions in the District of Columbia while Trist served as consul in Cuba. A member of the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia, Kane donated the chair to that organization in 1838:

I beg leave to entrust to the care of the Society the writing chair used by Mr. Jefferson at Philadelphia, while preparing the Declaration of Independence: At the close of the congressional labours of 1776, he carried it with him to Virginia; and after his death, it was carefully preserved by his family with a few other personal memorials. His daughter, the late Mrs. Randolph, did me the honour to present it to me some eighteenth months ago, and it is through her that I became acquainted with its history. It is a plain, old-fashioned Windsor armchair, with a circular back; a writing leaf or table is fixed upon the right arm, and the body of the chair revolves around a pivot. It has been repaired since it came into in my possession, but without changing its form in any respect.

Minutes 1834-1839 APS

Stated Meeting 20th April President Mr. Du Ponceau in the Chair

Mr. Jefferson’s chair presented Mr. Kane deposited with the Society the writing chair used by Mr. Jefferson at his Lodgings during the Congressional session of 1776

Microscopy and finish analysis performed by Dr. Susan Buck, whose report is published in this volume, refute the history reported by Kane.[11]

On January 11, 1837, Nicholas Trist wrote to William Beverley Randolph: “[Mr. Jefferson’s] girls told me that Mr. John K. Kane wished to present [the Windsor chair] to the American Philosophical Society. He would gratify me by accepting it for that purpose.” Trist and other family members were acutely aware of Jefferson’s legacy and began assembling relics immediately after the latter's death. If Trist or any of Jefferson’s descendants believed that he had used the chair in drafting the Declaration of Independence, it would likely have been mentioned in correspondence and almost certainly kept in the family. Instead, Trist described the object as the “large red turning chair,” indicating that its rotating seat and color were in his mind Windsor’s most significant identifying features. It was Trist and his wife who gave Kane the armchair, not Jefferson’s daughter Martha as the judge claimed.[12] While it is possible that Marha Randolph told Kane that he could have the chair during her visit to Philadelphia in 1836, there is no documentation to that effect. All that can be said with certainty is that Trist allowed Kane to take the chair to give to the American Philosophical Society and that the judge did not receive that object directly from Martha Randolph as Kane's letter suggests.

Alterations to Jefferson’s rotating Windsor armchair make that object extremely difficult to date. Buck’s analysis, which included the upper section of the seat, determined that the seating was originally painted white/ cream. Furniture scholar Nancy Goyne Evans’ survey of paint colors used on Windsor furniture, which included over 1,200 documents, revealed only one mention of white paint on that type of seating before 1790. That solitary reference, which occurred in 1784, may have alluded to paints suitable for Windsors rather than to actual white-painted seating. Significantly, one of the earlier documented examples of white Windsor chairs is the group of twenty-four listed on the first floor of Benjamin Franklin’s residence in Philadelphia in 1790. White was a fashionable color for other types of contemporaneous Philadelphia seating and table forms, including neoclassical framed chairs in the French style. Jefferson’s voluminous correspondence and other documents pertaining to him contain only two references to his purchase of Windsor furniture in Philadelphia during the eighteenth century. On April 6, 1793, Jefferson paid Francis Trumble twenty dollars for “12. Chairs” and $1.40 for painting six of them. More specific is an April 2, 1798, entry in Jefferson’s memorandum book noting that he “gave [Windsor chairmaker] Lawrence Allwine on Barnes for 25 D. for a stick sofa and mattrass.” After 1800 Jefferson purchased additional Windsors, some of which had bamboo legs.[13]

As Buck’s report indicates, Jefferson’s armchair was grain-painted after that object was modified to rotate. Once the rotating mechanism was completed, the lower section of the seat, which was new at that time, received a white primer coat followed by a red base coat and then a thin brown coat for the faux graining, which was likely intended to resemble rosewood or mahogany. That assumption is supported by Trist’s reference to the chair being “red.”

Diane Ehrenpreis’s essay in this volume suggests that the model for the swivel mechanism on Jefferson’s Windsor was the rotating armchair he acquired from New York City cabinetmaker Thomas Burling in 1790 (fig. 9). As figures 10–13 show, this mechanism is comprised of a metal pin and sleeve that register the seat sections and pulleys that ride on metal plate. If the seat conversion was done in the Monticello joinery, as seems likely, that work the fabrication and installation of and the later bamboo legs could have involved David Watson, James Dinsmore, John Nelson, James Oldan and enslaved craftsmen John Hemmings and “Lewis.” Buck’s analysis indicates that the legs received the same faux graining as the converted seat, turned arm supports and arms, spindles, and crest. In Due Reverence: Antiques in the Possession of the American Philosophical Society, the authors state that “the legs were replaced by legs typical of a Windsor chair of the late eighteenth century” when the chair was restored in 1975; however, a photograph published in 1926 shows the chair with bamboo legs (fig. 14). It does, however, appear that the bamboo legs may have been removed and reattached, since there are breakouts around their drilled mortises and later plugs (fig. 11).[14]

The writing platform and support on Jefferson’s rotating Windsor are also later additions as indicated by their coarse construction and Buck’s analysis. The addition of those components occurred after the seat conversion based on the absence of graining and the different paint history. All that can be said is that a writing platform was clearly part of the chair when Kane presented that object to the American Philosophical Society. The evidence presented here indicates that the original chair likely dates no earlier than 1785 and was subsequently modified at least two times. Nevertheless, that object’s rotating seat speaks volumes to its owner’s creativity and ingenuity and raises new questions about how and where Jefferson or other members of his household used it.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For assistance with this article, the author thanks Susan Buck, Diane Ehrenpreis, Nancy Goyne Evans, Magdalena Hoot, Alexandra Alevizatos Kirtley, Alan Miller, Kathryn Gery Lesieur, and Mary Grace Wahl.

Joseph Coolidge to Thomas Jefferson, February 27, 1826, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/98-01-02-5939. In full, Coolidge writes: “When I think of this desk, ‘in connection with the great charter of our independance,’ I feel a sentiment almost of awe, and approach it with respect; but when I remember that it has served you fifty years—, been the faithful depository of your cherished thoughts; that upon it have been written your letters to illustrious and excellent men—your plans for the advancement of civil and religious liberty, and of Art and Science; that it has, in fact, been the companion, of your studies, and the instrument of diffusing their results;—that it has been the witness of a philosophy which calumny could not subdue, and of an enthusiasm which eighty winters have not chilled,—I would fain consider it as no longer inanimate, and mute, but as something to be interrogated and caressed.”

1775 Virginia delegates, most of whom lodged at Randolph’s boarding house, were: Richard Bland; Benjamin Harrison; Patrick Henry; Thomas Jefferson; Francis Lightfoot Lee; Richard Henry Lee; Thomas Nelson Jr.; Edmund Pendleton; Peyton Randolph; George Washington; and George Wythe.

Jefferson arrived in Philadelphia as the youngest Virginia delegate to the Second Continental Congress on June 20, 1775, and took room and board at the city home of Benjamin Randolph. On July 29 Jefferson paid for his lodging, which may also have covered the cost for the writing box. By August 1 he was on his way to Monticello for harvest time. He then returned to Philadelphia by September 30, lodging again at Randolph’s house on Chestnut Street, where he shared housekeeping expenses with Peyton and Elizabeth Harrison Randolph and Thomas and Lucy Grymes Nelson (Dumas Malone, Jefferson and His Time, 6 vols. [Boston: Little, Brown, 1948-1981], 1: 211). On December 28 Jefferson paid Randolph for “a yd. of oznabrigs 2/6” and left for Monticello. Jefferson returned to Randolph’s boarding house on May 14, 1776, four days after the Second Continental Congress had commenced. On March 15, the Virginia Convention instructed its delegation in Philadelphia to propose a resolution that called for a declaration of independence, the formation of foreign alliances, and a confederation of the states: “You’l have seen your Instructions to propose Independance and our resolutions to form a Government” (Edmd. Pendleton to Thos. Jefferson, May 24, 1776, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/jefferson/01-01-02-0157. On May 23 Jefferson took residence in a new and furnished brick house owned by bricklayer Jacob Graff Jr. located on the southwest corner of Seventh and Market Streets, a little more than four blocks from Randolph’s home. It can be assumed that the box was taken to those second-floor apartments. That day Peyton Randolph was replaced as president by John Hancock, having been called back to Virginia; Jefferson took Randolph’s place in the Virginia delegation. This suggests that Jefferson, in accordance with the Virginia Convention instructions, may have begun his work on a draft of the Declaration of Independence while residing at the home of Benjamin Randolph, even though Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert R. Livingston were yet to be appointed to a committee to formally draft the Declaration of Independence on June 11, 1776 (The Declaration House through Time, Independence National Historical Park, National Park Service, July 5, 2021, https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/independence-dechousehistory .htm). In an 1825 letter to Dr. James Mease, Jefferson recollected: “I lodged in the house of a Mr. Graaf, a new brick house 3 stories high of which I rented the 2d floor consisting of a parlour and bed room already furnished . . . in that parlour I wrote habitually and in it wrote this paper [Declaration of Independence] particularly.”

This was similar to one owned by Benjamin Franklin. The leg carving is done in the manner of the Garvan high chest carver whom the author believes was Richard Wooley.

Graff’s house was built by him in 1775. The Graffs lived downstairs while Jefferson occupied a small second-floor parlor and bedroom. The original structure was torn down in 1883.

Benjamin Randolph Ledger, 1768–1787, MssCol 3550, Manuscripts and Archives Division, New York Public Library.

Ibid., p. 166 (Shepper, £1.5, Cash [2 Ent.]); p. 192 (Hockenhull, £1.19); p. 199 (Maggs, £1.5, Cash); p. 222 (Easton 10s., Cash); p. 225 (Saunders, £1.11.3, Cash), p. 225 (Lightfoot, £1.8, Cash [2 Ent.]). “2 Ent” refers to additional work credited, which may apply to two different projects in the shop. Although other craftsmen worked for Randolph concurrently, these men are the only ones attached to Jefferson’s account. Hockenhull (b. ca. 1739–January 7, 1816) was a passenger on the ship Et of Donegal, which sailed from Belfast, Ireland, and arrived at Philadelphia on July 24, 1770. He married Margaret Walker at Christ Church on January 28, 1773 (Pennsylvania Archives, Second Series, edited by John B. Linn and William H. Egle, 19 vols. [Harrisburg, Pa.: E. K. Meyers, 1876–1890, 1896], 8: 274). The first account page for Hockenhull is missing from Randolph’s ledger, but it is evident that the latter sponsored his immigration. John Maggs (or Maag) (b. ca. 1751–1785) also appears in a May 4, 1768, entry in Randolph’s receipt book: “Thirteen Shillings & Nine pence which with one Sett of Bed Rails is in full for teaching John Mags at Night School Pr Todd & Dickinson 13/9.” Maggs married Elizabeth Goebler on June 13, 1782 (Mock Family Historian 1, no. 6 [November 1992], p. 51, http://homepages.rootsweb.com/~andert/mock/MHF/VolINo6.pdf ). For more on him, see: Barbara Eichel Dittig, MAAG-#1: Mock Family Historian Working Chart for the Maag Families of PA, July 25, 2004, http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.com/~mock/01.html.

Easton is first mentioned in Randolph’s ledger in August 1774, when he began receiving 10–15s. per day. By the following February he was receiving one pound. On September 6, 1775, Easton signed a receipt for £9.12. Three days later Randolph paid him £21.8.2 in the final settlement of his account (Benjamin Randolph Receipt Book, 1763–1777, collection 337, p. 194, Winterthur Library, Winterthur, Delaware; and Randolph Ledger, pp. 205, 222.)

For more on Saunders, see: “Joseph Saunders, 1713–1792,” rev. January 2021, http://www. saundersfamilyhistory.com/images/Chapter%202%20-%20Joseph%20Saunders.pdf. Saunders was born on November 15, 1759, and died at sea in 1780/1781. A notation in a family Bible states:

Peter Saunders left Philadelphia the 22nd December 1780 in Company with John Benezet in Order to Embarque with him on board the Ship Shelaley Capt Homesbound to Port Lercon in France with intention to stay there and in Holland about a year, they Embarqued at Chester & proceeded, but were never heard of after leaving Delaware Bay; there were on board about eighty persons passengers and Seamen, it is supposed they founded at Sea (Mark Meredith, “John Benezet, 1749-1781,” 2021, House Histree, https://househistree.com/people/john-benezet).

According to a May 29, 1760, notice:

JAMES LIGHTFOOT left his Wife about two years ago, in Bristol, in England, and sent for her over here; up on which she accordingly came, and arrived here the 19th of November last, in the Prince George, and hath, since that Time, heard that he was at work at Mr. John Inch’s, in Annapolis, to whom she has wrote several Letters, but is uncertain whether he ever received them, as she never had an Answer. This is to give notice, that if any Person can give any Information of him, and will direct a Line to me, at Mr. John McMichael’s in Philadelphia, it will be taken as a very great Favour, and acknowledged as such, by ESTHER LIGHTFOOT (“Elopements and Other Miscreant Deeds of Women,” Pennsylvania Genealogical Magazine 34, no. 3 [1986]: 219–20.)

Randolph Ledger.

Lawrence M. Small, “Mr. Jefferson’s Writing Box,” Smithsonian Magazine (February, 2001), https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/mr-jeffersons-writing-box-37204074/.

Thomas Jefferson to Ellen Wayles Randolph Coolidge, November 14, 1825, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/98-01-02-5659. This is an Early Access document from The Papers of Thomas Jefferson: Retirement Series.

For the provenance of the chair, see: “Revolving Windsor Armchair,” Thomas Jefferson Encyclopedia, https://www.monticello.org/site/research-and-collections/revolvingwindsor-armchair; and, Revolving Windsor Chair with Writing Arm, Object record, no. F24, A merican Philosophical Society Museum, https://amphilsoc.pastperfectonline.com /webobject/E13401EC-2BB2-42F4-93C5-710445455100. For more on Kane, see: “John K. Kane,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_K._Kane. Quote in Murphy D. Smith and David Borodin, Due Reverence: Antiques in the Possession of the American Philosophical Society (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1992), p. 40. Martha Jefferson Randolph died on October 10, 1836, eighteen months prior to Kane’s donation of the Windsor armchair to the American Philosophical Society. In her recollections, Martha Jefferson Trist Burke, Martha and Nicholas Trist’s daughter, wrote: “The little Old fashioned Sofa belonged to Mr. Jefferson who gave it & the chair belonging to it to my father N. P. Trist, when my father was at Monticello reading Law under Mr. Jefferson. The chair my father . . . gave to Judge Kane of Phila he gave to the Hist Society of Phila.” Her recollection regarding the furniture was mistaken, as it clearly referred to the “metamorphic” sofa and rotating armchair discussed in Emilie Johnson’s article in this volume; but Nicholas did read law with Jefferson at Monticello in 1817 and 1821. It is conceivable that some of the modifications made to the Windsor chair were for Trist’s use.

Nicholas P. Trist to Wm. Beverley Randolph, January 11, 1838, DLC/NPT reel 2, frame 331, Nicholas P. Trist Papers, Library of Congress. Directly below that reference, Trist informed Beverly that the latter was “wrong in your supposition about the Facsimile of the Declaration of Independence.” This indicates that erroneous assumptions about objects owned by Jefferson were being made by people outside his family.

Nancy Goyne Evans, Windsor-Chair Making in America: From Craft Shop to Consumer (Lebanon, N.H.: University Press of New England, 2006), pp. 144–45. Although Evans suggested that the “Eight white Rush bottom Chairs” that the furniture maker William Savery sold Philadelphia merchant John Cadwalader in 1770 were painted, there is evidence to the contrary. Contemporaneous and earlier makers of rush seated charis, “white” to designate unpainted forms. Nancy Goyne Evans “Documentary Evidence of Painted Seating Furniture: Late Colonial and Federal Periods,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Lebanon, N. H.;University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2011) p. 209 and , of the many savery-type rush seated chairs known, none survive with original white paint. Phillip D. Zimmerman, who has published on Savery seating extensively, agrees that the Cadwalader’s chairs were most likely unpainted, (Phillip Zimmerman to Luke Beckerdite, December 20, 2022). Thomas Jefferson, Memorandum Books, 1793, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/?q=Series%3AJefferson-02&s=1511311112&r=27. For the memorandum book reference to Allwine, see: “Windsor Bench,” Thomas Jefferson Encyclopedia, https://www.monticello.org/site/research-and-collections/windsor-bench. Smith and Bordin, Due Reverence, p. 40.

Murphy D. Smith, Due Reverence: Antiques in the Possession of the American Philosophical Society, (Philadelphia, PA; APS, 1993), pp. 39–40.