Desk-and-bookcase, Boston, Massachusetts, 1760–1770. Mahogany with white pine. H. 96", W. 41", D. 20 1/4". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The disguised repairs and faked components and surfaces probably date ca. 1955.

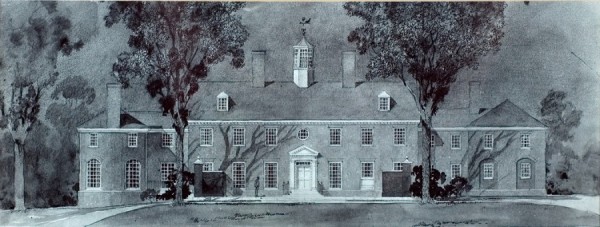

Chipstone Foundation, Fox Point, Wisconsin.

Front exhibition wall from The Truth Lies Within: Furniture Fakes from the Chipstone Collection, Milwaukee Art Museum, 2002. (Photo, Jorrin Hood.)

Image of kintsugi ceramic.

Beth Lipman, Distill #15, 2015. Cast iron with rust patina. 12" x 10" x 6". (Photo, JMKAC/Kohler Co.)

Beth Lipman, Sphenophyllum and Chains, 2019. Glass, wood, metal, paint, adhesive. 54" x 38" x 50". (Photo, Rich Maciejewski.)

Beth Lipman, Sideboard with Blue China, 2013. Glass, wood, paint, adhesive. 111" x 300" x 22". (Courtesy, John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art; photo, Margaret Fox.)

Beth Lipman, Secretary with Chipmunk, 2015. Wood, glass, ash, gold, brass, mirror, sugar, salt, adhesive. 96" x 41" x 20 1/4". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Jim Wildemann.)

Detail showing the cornice of Secretary with Chipmunk.

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Swing, Paris, 1767. 32" x 25 1/4". Oil on canvas. (© By kind permission of the Trustees of the Wallace Collection, London.)

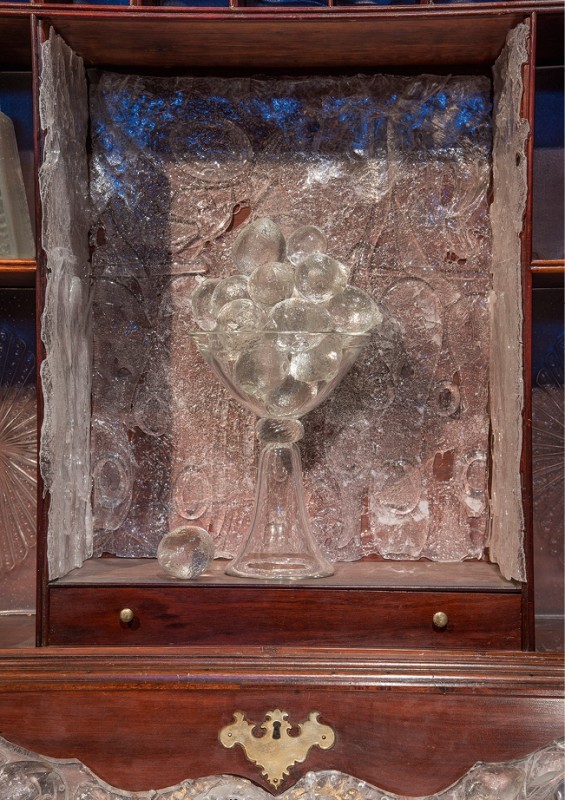

Detail showing the central compartment of the upper section of Secretary with Chipmunk.

Detail showing the fallboard of Secretary with Chipmunk.

In-process image of the fallboard shown in fig. 12.

Image showing Secretary with Chipmunk in process. (Photo, Kenneth Sager.)

In March 1956 we went to Europe, and when we returned, we dropped into John Walton’s and there we saw a truly outstanding Massachusetts bombé secretary of great quality. Coincidentally, Maxim Karolik and Ralph Carpenter came in while we were there; the former rhapsodized about the secretary until any doubts that we might have had about it, and I hasten to say they were minor, vanished, and we purchased it.

Stanley Stone, 1984

IN HIS ESSAY “On Friendship” in Laelius de Amicitia, the Roman statesman and scholar Marcus Tullius Cicero wrote the celebrated phrase “Esse quam videri,” which translates as “to be rather than to seem to be.” Unfortunately for Polly and Stanley Stone, whose decorative arts objects form the core of the Chipstone Foundation collection, the towering bombé desk-and-bookcase (fig. 1) that they bought from dealer John Walton only seemed to be real. As this piece and others attest, the history of art is filled with stories of fakery and deceit: Henry van Meergan’s infamous forged version of Vermeer’s Christ and His Disciples at Emmaus; John Myatt’s counterfeit Van Gogh paintings; or David Stein’s fraudulent Marc Chagall watercolors, which amusingly were deemed fake by the artist himself on the same day that they were first purchased by a New York art dealer. So the deception of the Stones by their primary dealer in this and several other major acquisitions stands as just another sordid chapter in the long legacy of duplicitous art objects.[1]

The Boston desk-and-bookcase was acquired in 1956 for fifteen thousand dollars, with an added $115 for “expenses incurred in delivery” to Wisconsin, and it immediately became a centerpiece of the Stones’ rapidly growing collection (fig. 1). As Stanley noted later in life, it was shortly after buying their first antique from Israel Sack in 1946 that the couple fell victim to what he jokingly called “virus antiquarium.” They initially drew inspiration from other leading collectors of American and Anglo-American decorative arts—among them, H. F. du Pont, Francis P. Garvan, Katherine Prentis Murphy, Louise du Pont Crowninshield, Ima Hogg, and others. To house their collection, the couple commissioned an impressive Georgian-style house that was finished in 1951 and located on the bluff overlooking Lake Michigan in Fox Point, Wisconsin (fig. 2). The building was designed by Andrew Hepburn, who as a partner in the Boston architectural firm Perry, Shaw, and Hepburn played a major role in the recreation of Colonial Williamsburg. In the decades that followed, the Stones continued to acquire early American furniture, as well as seventeenth- and eighteenth-century English pottery and American historical prints. As was the case with many of their collecting peers, the Stones focused on what were thought to be exemplary expressions of craftsmanship from the major furniture-making centers in colonial America: Philadelphia, New York, Boston, Salem, Portsmouth, and Newport. Contributing greatly to their growing body of knowledge about the topic, the Stones brought many of America’s and England’s leading decorative arts scholars, curators, collectors, and museum directors out to Chipstone, where rich conversations fueled the couple’s desire to acquire more stellar pieces. Soon Chipstone gained something of a national reputation not just for the quality of its holdings but also for the highly unusual circumstance in which a couple who lived far from the major East Coast shops and museums started buying notable examples of early decorative arts items.[2]

After more than forty years of collecting, Stanley Stone died in 1987. Around that time, the Chipstone Foundation was moving forward with initiatives under the guidance of Oswaldo Rodriguez Roque, its first executive director. A former student of decorative arts scholar Charles Montgomery, who himself was a close friend and advisor to the Stones, Roque made several key acquisitions for the collections and began discussions with the Art History Department at the University of Wisconsin in Madison about establishing a funded professorship named for the Stones. Roque died in 1989 shortly after publishing American Furniture in the Chipstone Collection. The following year, the foundation hired Luke Beckerdite as executive director. Only then did Mrs. Stone and the decorative arts world at large find out about the true condition of Stanley’s beloved bombé desk-and-bookcase and a number of other pieces in the collection. As later documented in a 2002 American Furniture article titled “Furniture Fakes from the Chipstone Collection,” a closer examination of the collection by Beckerdite and furniture scholar and conservator Alan Miller revealed approximately twenty aesthetically and structurally problematic pieces, many of which had been acquired from Walton, who had been close enough to the Stone family to have delivered a eulogy at Stanley’s funeral. There also was a corresponding exhibition at the Milwaukee Art Museum in 2002 titled The Truth Lies Within: Furniture Fakes from the Chipstone Collection (fig. 3).[3]

For many collections and institutions, such a discovery could have been very harmful, but Mrs. Stone sought a more proactive and productive response to the situation. In 1991 she sent a remarkably candid and, indeed, inspiring letter to the Chipstone Board of Directors that concluded with a paragraph stating her preference that the fakes be kept and used to educate others:

What of the owner of a handsome piece of furniture, who has developed a great love for it over the years and now finds it spurious? If he believes in the possibility of a piece of furniture having an integrity developed by the discovery of its age, maker, carver and condition not sullied by unauthentic change, will he want his collection composed of such pieces? If he is told of errors, inaccuracies, changes to try to show something not inherent to the piece, he may with new knowledge, be able to see the piece as it is—not as he has once been told it is. I hope some, at least, may be comforted by seeing the piece under consideration as it is and enjoy it.

At Chipstone we have learned to take the destruction of some of our loves as a necessary part of the much to be desired greater knowledge of what we have—perhaps an enhanced appreciation of a piece because of the final possible appreciation of the honesty it has. It was not easy to see some of our treasured favorites sent to the Fakes Room, but after the first shock, it became very clear that only honesty shown us by those with greater knowledge could give us back the satisfaction in our collection that we enjoyed.”

Mrs. Stone directed the trustees to rebuild the collection, and up until her death in 1997, and beyond, the foundation has continued to acquire important examples of early American furniture. Today the collection is far stronger and more diverse than ever before. As will be detailed below, the bombé desk-and-bookcase subsequently was published and exhibited as a fake before being relegated to storage, and there the piece sat for several decades before starting a most unexpected next chapter in its life.[4]

To begin with, what is meant by the term “fake” furniture? In their 2002 essay on Chipstone’s compromised pieces, Beckerdite and Miller laid a foundation for understanding, in a most general sense, what the term suggests:

Nearly every major collection of American furniture assembled during the last century has included objects that were intended to deceive. These pieces run the gamut from authentic furniture forms with carefully masked repairs, replacements, or embellishments to complete fakes. Although the subject of fraudulent objects can be a touchy one, everyone involved in collecting antique furniture has made mistakes. Reluctance among museums, dealers, and private collectors to discuss, let alone publish and exhibit fakes, contributes to their continued production and continued presence in the marketplace.

The prevalence and persistence of fakery are intimately linked to the demands and expectations in the marketplace. Few pieces of early American furniture survive in perfect condition, and even less are perceived as having the added qualities of artistic merit and/or historical significance. Although each of these considerations is important in assessing an object’s monetary value, museums, collectors, and individuals in the American furniture trade have traditionally placed an unreasonably high premium on condition. Fakers or individuals who knowingly sell fraudulent objects often attempt to make pieces with condition problems appear perfect in order to reap the benefits of this perspective.

In this light, Chipstone’s desk-and-bookcase is not a full-blown “fake” that was made from scratch by an unethical craftsman, nor is it a composite piece comprised of reused parts from other antique furniture forms—an approach commonly used by fakers most often in the creation of “antique” tables and seating forms, especially upholstered arm chairs and easy chairs that may have the legs from one old chair, arms from another, and assorted frame parts from still other old pieces. Instead, the desk-and-bookcase started life as a legitimate bombé example that two centuries later was dramatically altered. These purposefully deceptive repairs or changes may well have been in response to damage this piece had suffered over its long life, a situation that is quite common in the world of early American furniture. Over time, large case pieces like this one were moved from room to room or from home to home and in the process suffered damage and loss. Plus, there is the normal wear and tear that happens over hundreds of years of use and, at times, abuse from children, pets, and careless members of the household. Indeed, one could write a book on the harm done to antique furniture over time by mops, brooms, and vacuum cleaners. Original finishes almost invariably degrade over time, some worse than others, and then when they get stripped by glass-scraping or caustic chemicals, or when they get covered over with later finishes that are not compatible, there is the potential for even more harm to the piece. It appears that the alterations to this desk-and-bookcase were done prior to 1939, the year when Walton bought it from a collector in New Jersey named Harry Palmer. Walton’s understanding of the desk-and-bookcase’s condition remains unclear, but when he sold that object to the Stones, he produced a letter from Palmer stating that Palmer had acquired the piece from Willoughby Farr, of Edgewater, New Jersey. Farr was a well-known antiques dealer who sold many pieces of furniture to Natalie (1883–1951) and J. Insley Blair Jr. (1876–1939), whose gifts and long-term loans of furniture to the Metropolitan Museum of Art have long been highlights of the American Wing.[5]

At the time the Stones bought the piece from Walton, most collectors of early American furniture relied on the observations of antiques dealers, auction professionals, curators, and fellow collectors. The use of modern-day evaluative technologies such as infrared and black light scanning, microscopic wood identification, finish analysis, and carbon dating was unknown. In fact, rarely were pieces turned over or taken apart to look for inconsistencies in materials, tool marks, or joinery. If a trusted dealer said an object was good, buyers typically accepted that opinion. The most successful dealers were canny salespeople who knew how to convince their clients that the piece in front of them would make an especially desirable addition to their collection—a sales strategy that Harold Sack dubbed “remarkable discovery syndrome.” That these major dealers also were selling to the leading American art museums only elevated their reputation in the eyes of most potential buyers. Israel Sack used to tell potential clients that he did not need to examine an object to determine if it was genuine because it spoke to him from across the room. Sadly, when the Stones walked into Walton’s shop in 1956, there were no voices calling out to them about the many problems inherent with the bombé desk-and-bookcase. Instead, they only heard the glowing and convincing recommendations of John Walton, legendary collector Maxim Karolik, and decorative arts scholar Ralph Carpenter, who were visiting the former at the same time.[6]

So what were the later additions and alterations to the bombé desk-and-bookcase? Those that appear to have been fabricated from whole cloth for the purposes of this deception include the entire pediment, door panels of the bookcase, prospect door and fallboard of the writing compartment, and the feet and their blocking. The body, or carcass, of the desk, the drawers, and most of the fittings of the writing compartment are original; the top, sides, and bottom of the bookcase are also period, although there is not sufficient evidence to determine if that section is original to the desk or married later. Upon the discovery of these additions and alterations, the question of what to do with the desk-and-bookcase and the other fake pieces arose. Museum curators and private collectors traditionally have followed several different paths in dealing with compromised objects. In the most egregious and perhaps criminal examples, dealers and fakers have been pursued in the courts and their work relegated to storage, often never to be seen again. More often, altered pieces are returned to the marketplace with a clear description of their compromised condition. When the degree of loss or damage is not too considerable and the rarity, historic importance, or artistic merit is sufficient, museums and collectors engage scholars and conservators to restore objects to their original appearance. In the instance of the Stones’ desk-and-bookcase, the extent of the alterations and absence of clear historical prototypes made the latter approach impractical. On the other hand, those defects did open up the possibility to explore a very different kind of restoration treatment, one that stayed true to ethical standards of contemporary museum conservation but that did so in a way that was quite innovative and, indeed, unexpected.

In 2007 the Chipstone Foundation began a dialogue with Wisconsin artist Beth Lipman. At that date, artistic collaborations between members of the traditional decorative arts community and contemporary artists were minimal. The foundation was and remains keenly interested in bridging this historic divide and exploring its interpretive potential in a museum setting. Meetings between the artist and the Chipstone team revealed considerable intellectual and conceptual overlap. Central to the foundation’s mission is the investigation of material culture, a term that describes the study of inanimate objects to glean knowledge about individuals and their society. Lipman’s work reflects a similar approach in that her compositions seek to recontextualize our understanding of the human condition. As both paradigms converged, Lipman’s studio practice evolved, and the focus of her glass sculptures and installation shifted.

Chipstone’s curatorial team began to explore with Lipman the possibility of replicating a piece of eighteenth-century furniture in glass. This discussion was inspired by her majestic large-scale glass sculptures that took many of their visual and thematic clues from seventeenth-century Netherlandish still lifes, including the use of historically inspired table wares, ceramics, and furniture forms. In the midst of these conversations, an alternative concept emerged—namely, the possibility of having Lipman work with one of Chipstone’s compromised pieces to do a very different kind of “restoration.” Because of the nature of its additions and alterations, as well as its original status as a revered object in the Stones’ collection, the bombé desk-and-bookcase was a logical choice for this innovative artistic intervention, which sought to be both redemptive and expressive. The proposed “treatment” of that object centered on an artful exploration of historical meaning and metaphor as those relate to this once majestic piece of early American furniture, focusing in on revealing to contemporary viewers its rococo character as well as the distinctive eighteenth-century cultural context—both colonial and international—from which it emerged. When the inappropriate parts were removed, what remained was more than a broken carcass and a sad remainder of what was once so beautiful; the original components represented a solid and historically accurate foundation with unique interpretive and artistic potential.

Perceiving beauty in the old, the damaged, and the altered is not original by any means. The Japanese concept of kintsugi centers on finding beauty and value in that which is compromised or broken—be it an object such as a piece of furniture or an old ceramic, or a human being who has suffered some kind of loss or injury, whether physical or emotional (fig. 4). Probably the most familiar manifestations are fine ceramics that have been broken, glued back together, and gilded along the fracture lines to accentuate and acknowledge the previous damage:

[Kintsugi] has to do with the symbolism of healing and resilience. First taken care of and then honored, the broken object accepts its past and paradoxically becomes more robust, more beautiful, and more precious than before it was broken. The metaphor can provide insight into all stages of healing, whether the ailment is physical or emotional.

Inspired by the concept of kintsugi, the “restoration” of the desk-and-bookcase sought to highlight the playful style and raucous way of life that embodied the eighteenth–century rococo style and found its most potent expressions in European fine and decorative arts. Indeed, Lipman’s work is completely in the spirit of the genre pittoresque, what William Park dubbed “The Idea of Rococo.” This strategy of moving beyond conventional art historical analysis and decorative arts terminology in turn allows for a consideration of the very spirit of the style:

Such an approach necessarily suspends the Apollonian ideal that is the foundation of the traditional decorative arts view and instead emphasizes the need to think rococo and to recognize the style’s fantastic exploration of things Dionysian and mythological. It also emphasizes the power of metaphorical thought, a way of seeing and perceiving favored by classically educated rococo patrons but less familiar to modern observers, whose interest in the lessons of ancient mythology has given way to what Joseph Campbell calls the “news of the day” and “problems of the hour.” In sum, this new reading . . . entails moving our critical gaze away from the abstract ideal of spiritual order and toward the earth itself, where we must conceptually enter the primordial ooze in search of the grotto, the very soul of the rococo.

As noted previously, Lipman’s work is rooted in the still life genre, a form of expression codified in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Europe that symbolically represents the splendor and excess of the Anthropocene. Assemblages of inanimate objects and domestic interiors are inspired by private spaces and public collections—proposed portraits of individuals, institutions, and societies that consider the stratigraphic layer that humanity will leave on earth. This collision of sacred and profane artifacts with aspects of the natural world focuses attention on an evolving set of beliefs stemming from the narrative power of objects. From family heirlooms to the ubiquitous plastic water bottle, core stories can become altered or even lost over time. For example, temporality and mortality are primary concerns linked to the Still Life tradition, and these themes become heightened through a consideration of the materiality included in the imagery.[7]

In like manner, Lipman’s works in wood, metal, photography, video, and especially in clear glass emphasize evanescence at the heart of the essentially fleeting nature of “vanitas” in early still lifes. Her Distill Series (fig. 5) features miniature cultural objects, pine cones, moss, and lichen in constructed dioramas that then are literally destroyed in the process of casting in molten metal. The resulting sculptures are fossilized remnants of the originals. These questions of life, death, and transience similarly inform the large clear glass laid table installations. Here, the components—some seemingly more alive than others—optically frustrate the eye as they slip into and out of focus when the viewer moves toward and around the compositions. The qualities of the material and their temporal inconsistency are harnessed as the visitor looks at and then through the forms; one’s observation shifts to reflection or refraction depending on the light source. Many of Lipman’s large-scale installations provoke more substantive meditations on “deep time,” a chronological scale based on geologic events that puts into context the minimal role of humans throughout the ages (fig. 6). Some sculptures reimagine history, placing what she visualizes as “life cycles,” separated by both time and type, into conversation with one another. The unexpected incorporation of prehistoric flora with historical decorative arts forms alludes to the impermanence of the present and the persistence of life. In this context, the ephemera of the Anthropocene in what otherwise appears to be a historically inspired still life scene becomes a symbol of fragility as the human species is placed on a continuum where time eradicates hierarchy.

Sideboard with Blue China (2013), an extravagant sculptural composition that combines depictions of human predation with human physiology, was especially foundational in discussions with the Chipstone team and led to the foundation’s interest in the artist incorporating an object from the collection in her work (fig. 7). This represented an opportunity that was unique; rarely does an artist engage directly with an object in an institutional collection. After removal of the new and faked components, the desk-and-bookcase was delivered to her studio and, quite literally, left to Lipman to consider ways to bring it back to life. Foremost for Lipman and the Chipstone team was a deep desire to honor, not subjugate, what remained of the original desk-and-bookcase. After all, historic objects that have been intentionally altered still have integrity, and their very essence as artifacts can inform us about the time, place, and artistic mindset from which they emerged. Completed within a year, Lipman’s finished work combines elements of human anatomy with symbolic objects in much the same way that a still life can illuminate our understanding of the world (fig. 8). Central to her approach was a deep examination of the rococo, in which she explored ways that empirical knowledge could be represented by the corporeal body and cultural constructs and experienced through the senses. Secretary with Chipmunk considers the intangible: the ways that we understand our world and ourselves through psychology and philosophy, represented by aspects of the grotto.

The pediment harnesses the visual and conceptual aspects of the rococo, crowning the secretary with an asymmetrical cartouche and imagery associated with one of that style’s most important emblems, the grotto—the literal and metaphorical portal one enters to explore and challenge the mind, psyche, and spirit more fully (fig. 9). In the reimagined secretary, both the pediment and feet become a fecund transparent landscape, incorporating shells,flora, and various size rock formations. Also referred to during the period as the “genre pittoresque,” the rococo has a unique relationship to domesticity, historically the realm of women, that gave rise to the femininity that permeated eighteenth-century culture. A reaction to the masculinity of the baroque era, it created space to celebrate the professionalization of women, especially in the fields of literature and the arts, at a time when initial advancements were being made toward women’s rights and education. The sensuous curvature of the side profile of the secretary, inspired by earlier anthropomorphic bombé forms, is in keeping with the centrality of the rococo S-curve. As has been well argued by William Park and other scholars of that era, these signature motifs and themes came to signify the eighteenth-century rise of the woman and the growing recognition of the power of female sexuality, and they suggest a way forward to explore the object through a style historically in dialogue with the body (fig. 10):

Neverthless an extraordinary change, which is everywhere apparent, had taken place not only in sensibility and consciousness but in practice . . . . The adjectives used to describe the rococo are feminine, or customarily associated with femininity: tender delicate, soft intimate, erotic, playful, curvaceous, pleasant, dissolving and, pejoratively, disordered, frivolous, and superficial . . . . It celebrates fecundity as well as pleasure, for the interior spaces of the rococo, both secular and religious, can be seen as glorified wombs, every surface of which is equally alluring and desirable.

Throughout Secretary with Chipmunk, anatomy is narrated through literal bodily representations, the creation of symbolic interior spaces, and the inclusion of sculpted cultural artifacts (fig. 11). The collision of the corporeal with anthropocentric objects suggests a porosity between the boundaries that separate us from not us; objects become embodied, and the human body becomes objectified. Through this slippage, meaning and knowledge are shown as constantly evolving processes, stemming from the narrative power of objects and our relationship to the body, changing throughout different epochs and contexts. In the true spirit of the rococo, Secretary with Chipmunk deeply references the grotto, which brings with it visual and thematic references to the female body and inclusion of rocaille motifs: representations of rocks, scrolls, falling water, and shells.[8]

In this sculptural constellation—which purposefully blends old and new, wood and glass, the tangible and the intangible—the bookcase interior evokes a nasal cavity, replete with olfactory receptor cells featuring cilia extensions that trap odors. Situated in the cavity is a large-footed vessel holding lemons—a fruit that observers recognize as deeply engaging the senses of sight, smell, and taste. The fallboard is pierced in the shape of a rococo cartouche, inverting that found on the pediment. This device alludes to female sexual anatomy, mirroring one of the more vital of all rococo themes. Additionally, the new glass prospect door includes a protruding tongue that confronts the viewer and further announces the bold sexuality of the rococo style (fig. 12).

Some of the “fake” elements have been burned and their ashes imbedded into the molten glass to create new components, an act that becomes a metaphor for reincarnation (fig. 13). The destruction of a beloved object for the purpose of imagining something new is mimetic of natural cycles—for example, lightning starting a fire that helps seeds to germinate. The sculptural processes and the known history of Secretary with Chipmunk function as analogies for life cycles. The date of the desk-and-bookcase’s first deconstruction, or perhaps its gradual decay due to loss, wear, or breakage, is lost to time, but the piece is known later to have been reconstructed in the mid-twentieth century prior to being sold to the Stones. With this recent artistic reinterpretation, the piece has now experienced another deconstruction by the Chipstone team when they removed the “faked” elements, and then another reincarnation brought about by the artist’s actions. The unique cycle of growth embedded within the work—which applies to so many surviving historic decorative arts objects today—causes us to rethink the perceived authenticity of this historical artifact. In this instance, the destruction has enabled an act of reincarnation. This timeless paradox is intrinsic to human nature, namely that we must destroy in order to create.

Ultimately, Secretary with Chipmunk stands as a new kind of redemptive conservation approach, one that actively explores history and style while also inviting multiple levels of engagement: aesthetic, experiential, intellectual, and psychological. This particular Boston desk-and-bookcase has existed throughout its lifetime as an important example of early American furniture: first used and then perhaps only somewhat as the decades passed; then reformed as an object heavily modified both by restoration and fakery; and finally today as a contemporary work of art. As an object, Secretary with Chipmunk suggests many new ways for us to think about old things, including the futility of striving toward an ideal state. Lipman’s finished interpretation suggests, among other things, that notions of authenticity are porous and at times problematic, and that objects inevitably remain deeply connected to their previous incarnations. Put another way, they do not or perhaps cannot wholly move beyond what they once were and how they once were understood. Today, Secretary with Chipmunk breathes new life into an altered eighteenth-century furniture form, and as such it allows viewers—both now and in the future—to think in alternative ways about meaning, form, and style.

Stanley Stone, “Life Begins at Fifty,” in Oswaldo Rodriguez Roque, American Furniture at Chipstone (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1984), p. ix. Polly M. Stone to the Chipstone Foundation Board of Directors, June 7, 1991, Chipstone Foundation, Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

For more on these collectors and others, see Elizabeth Stillinger, The Antiquers (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1980). This house was built on Mariner family property that Polly inherited. She and Stanley demolished the existing 1900 summer cottage that had been designed by Elmer Grey. Elmer Grey, “A Summer House in Wisconsin,” House Beautiful 10, no. 1 (June 1901): 3-8.

Polly Stone to the Board of Directors of the Chipstone Foundation, June 7, 1991, Fountation files, Fox Point, WI.

“Record Prices at Christie’s Americana-Blair and Various Owners Sales,” Antiques and the Arts Weekly, January 31, 2006, https://www.antiquesandthearts.com/record-prices-at-christies-americana-blair-and-various-owners-sales/. Uneasy about fakes, Blair in 1916 switched from European to American antiques. She bought heavily from Edgewater, N.J., dealer Willoughby Farr, as well as from New York dealers Collings and Collings, Henry V. Weil, Charles Woolsey Lyon, and Charles R. Morson. “Willoughby Farr had a wonderful eye and Mrs. Blair wanted the greatest things. Her gifts to the Met are priceless,” said Albert Sack, who does not recall the collector buying from his father, Israel Sack, who was still in Boston during the 1920s. On behalf of a client, Albert Sack purchased a Philadelphia Chippendale dressing table, $120,000, that Blair got from Charles Woolsey Lyon in 1923. Harold Sack with Max Wilk, American Treasure Hunt (New York: Little Brown and Co, 1986) .

Harold Sack and Max Wilk, American Treasure Hunt, pp. 1–21.

Celine Santini, Kinsugi: Finding Strength in Imperfection (Kansas City, MO: Andrew Mcneel, 2019), p. 6. Jonathan Prown and Richard Miller, “The Rococo, the Grotto, and the Philadelphia High Chest,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1996).

William Parke, The Idea of Rococo (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1993), p. 32.