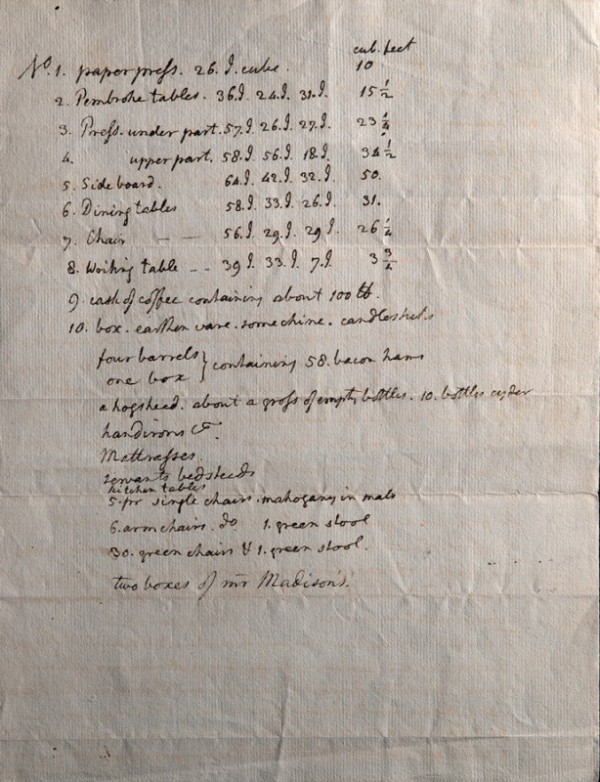

Thomas Jefferson, packing list, New York City, August 31, 1790. Pen and ink on paper. (©Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Dining room at Monticello, Albemarle County, Virginia. (©Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello; photo, Philip Beaurline.) The side chairs are attributed to Thomas Burling, New York City, 1790.

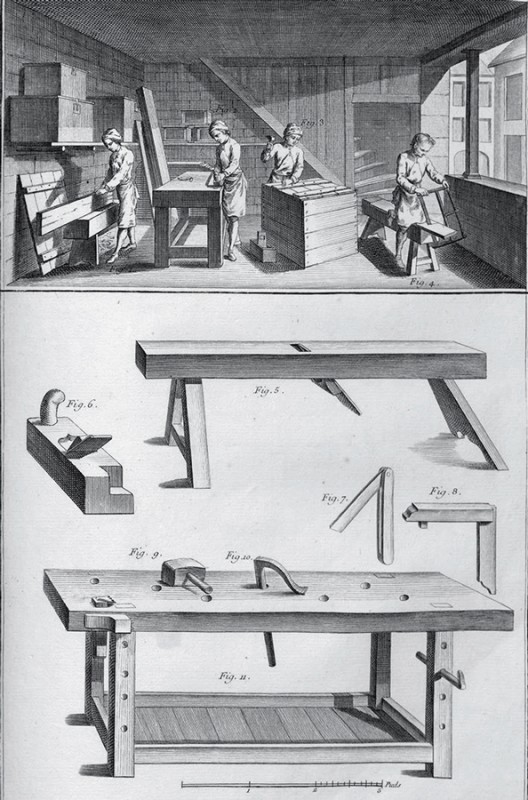

Louis-Jacques Goussier, «Layetier,» Supplément à l’Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, vol. 5 (Paris: Chez Briasson, 1762–1772). (Courtesy the ARTFL Encyclopédie Project, University of Chicago.)

Detail showing the octagonal top of a writing table attributed to New York City cabinetmaker Thomas Burling. (Collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Library at Monticello, Albemarle County, Virginia. (©Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The writing table and armchair with Thomas Jefferson’s shipping brand were likely used in this room.

Detail of Thomas Jefferson’s shipping mark branded on the arm of a chair packed and shipped from France. (©Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

John Always, side chair, New York City, ca. 1790. Tulip poplar (seat), soft maple (left rear leg), maple (medial stretcher), and hickory (center spindle and back rail). H. 35 5/8", W. 18 3/4", D. 20 1/4".(Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

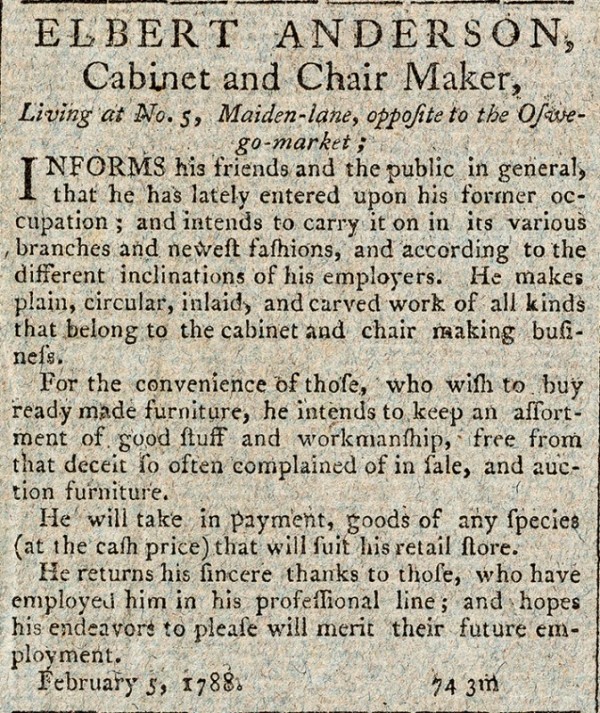

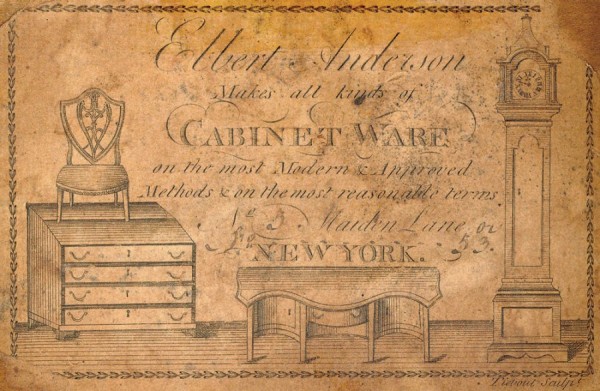

Advertisement for Elbert Anderson, New-York Packet, February 8, 1788. (Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society.)

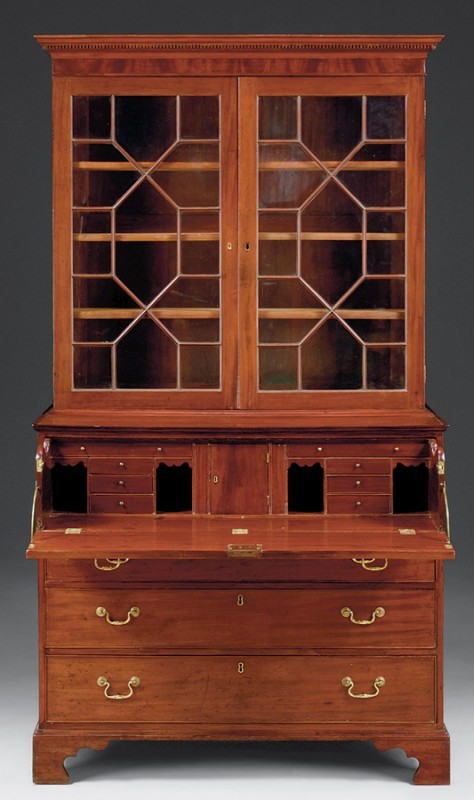

Elbert Anderson, secretary-andbookcase, New York City, 1786–1796. Mahogany with unidentified secondary woods. H. 88 7/8", W. 49 3/4", D. 24 1/4". (Courtesy, Christie’s.)

Detail of the label on the secretary-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 9 (Courtesy, Christie’s).

Elbert Anderson, armchair, New York City, 1790–1800. Mahogany with beech and maple. H. 36 3/8", W. 21", D. 19 7/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) This chair is part of a large set ordered by Alexander and Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton.

Armchair, attributed to Elbert Anderson, New York City, 1790. Mahogany with hackberry or elm. H. 37 3/4", W. 21 3/4", D. 18 1/4". (©Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

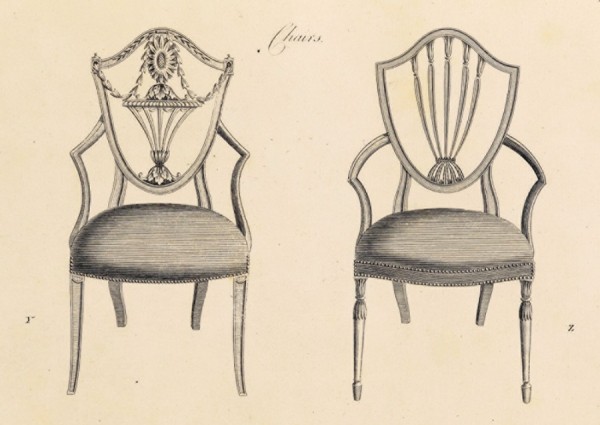

Design for “Chairs” illustrated on pl. 9 in George Hepplewhite’s Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Guide (1788). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Armchair attributed to Thomas Burling, New York City, ca. 1790. Mahogany with oak. H. 40", W. 28", D. 17". (Courtesy, Division of Cultural and Community Life, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.)

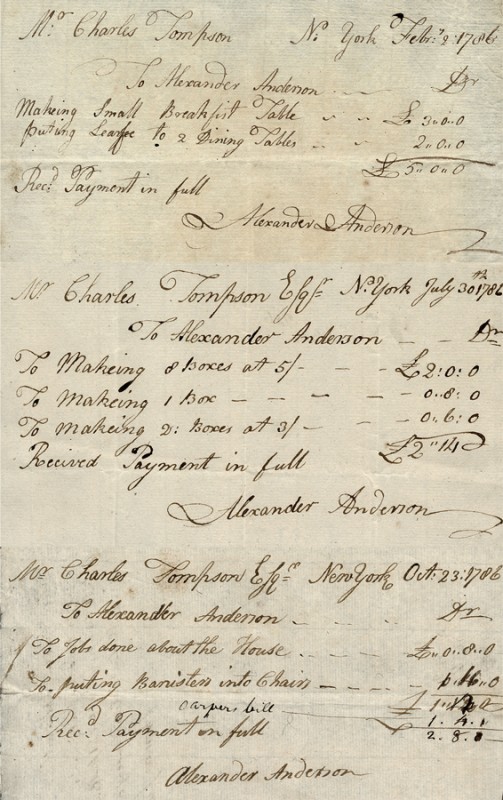

Alexander Anderson to Charles Thomson, invoice dated February 2, 1786. Ink on paper. (Courtesy, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.)

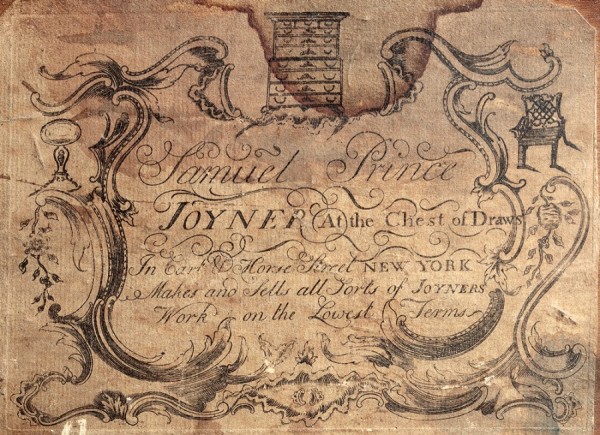

Label of Samuel Prince, New York City, ca. 1765–1775. Ink on paper. (Courtesy, Levy Galleries, New York.

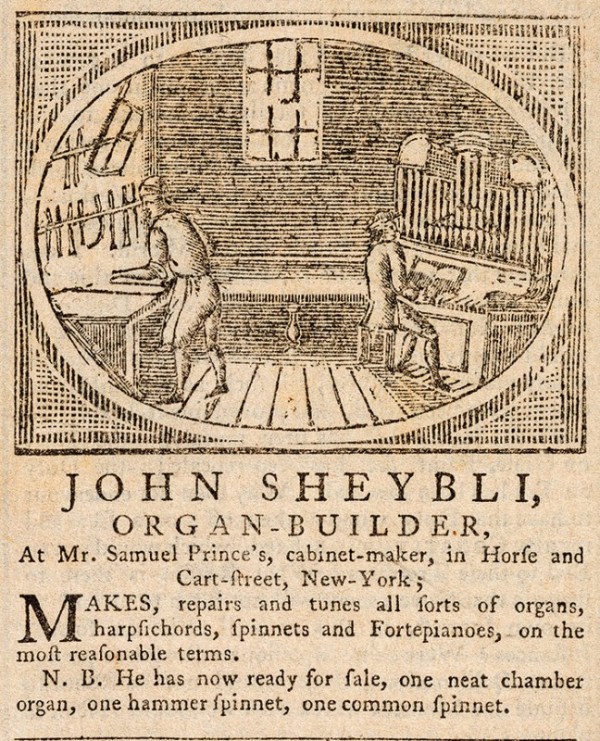

Advertisement for John Sheybli, New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury, October 10, 1774. (Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society.)

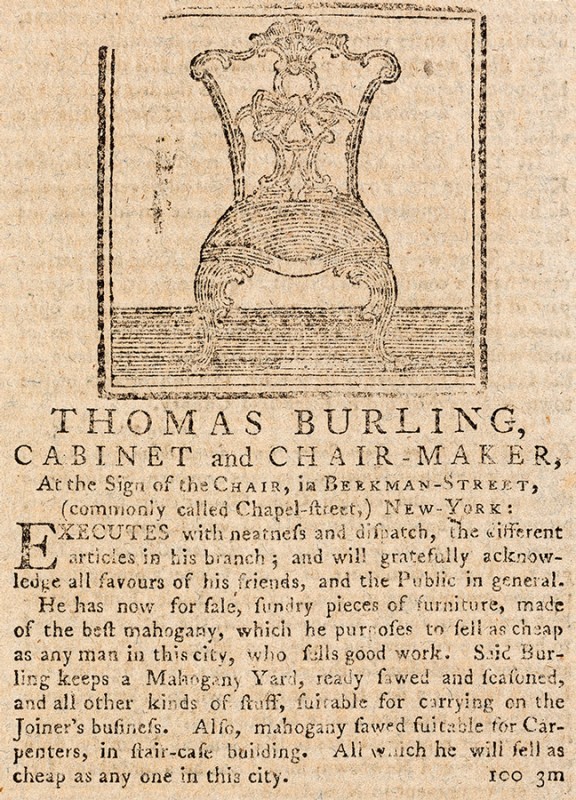

Advertisement for Thomas Burling, Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer, March 16, 1775. (Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society.)

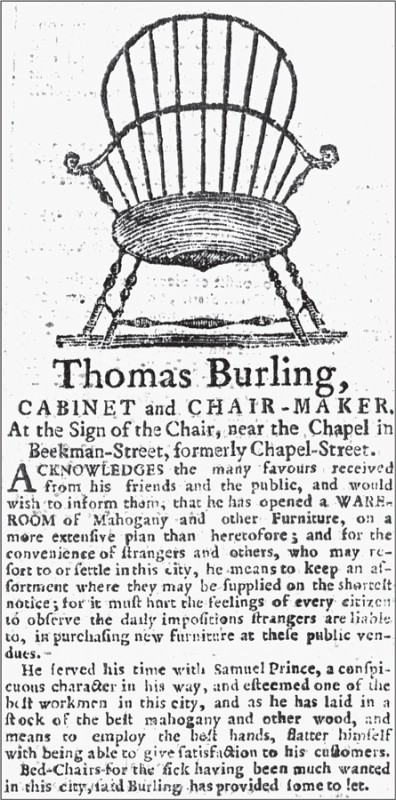

Advertisement for Thomas Burling, Daily Advertiser, Political, Historical and Commercial (New York), November 16, 1786. (Courtesy, NewsBank/Readex.)

Denis-Louis Ancellet, table à la tronchin, Paris, ca. 1780. Mahogany with oak. H. 27 1/4" (closed), W. 34", D. 23". (©Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Table, possibly by Jacques Upton, Paris, ca. 1785–1789. Mahogany, oak, marble. H. 29 1/2", W. 30 3/8", D. 29". (©Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This table is one of a pair.

Samuel Tilt, universal table, London, 1790. Mahogany, oak, brass. H. 27", W. 36", D. 29 1/2". (©Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

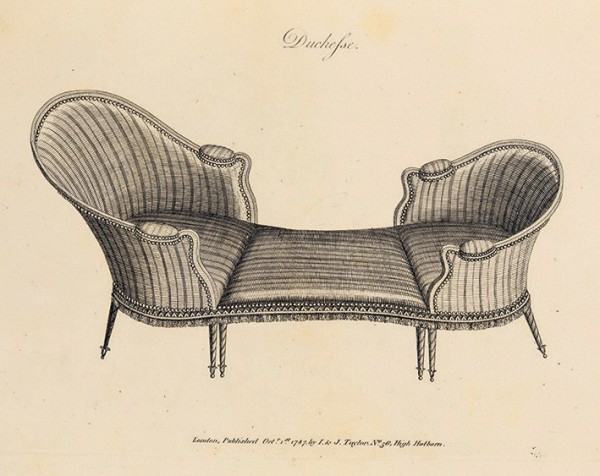

Design for “Duchesse” illustrated on pl. 28 in George Hepplewhite’s Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Guide (1788). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Harrison Higgins Jr., sideboard, Richmond, Virginia, 2009. Mahogany. H. 37",W. 60", D. 23 1/2". (©Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Thomas Burling, sideboard, New York, ca. 1790. Mahogany with unidentified secondary woods. H. 38 1/4", W. 64 1/4", D. 26 3/4". (Courtesy, Sotheby’s.)

Label of Thomas Burling, New York City, ca. 1786–1793. Engraving on paper.(Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Old Salem Museum and Gardens, WinstonSalem, North Carolina.)

Thomas Burling, side chair, New York City, 1790. Mahogany with oak. H. 36", W. 20 1/2", D. 16 1/2". (©Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello; photo; F. Carey Howlett.)

Pembroke table, attributed to James Dinsmore and John Hemmings, Monticello, Albemarle County, Virginia, 1807. Mahogany with yellow pine and cherry. H. 27 7/8", W. 26 1/8", D. 26 7/8". (©Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Writing table, attributed to the joiner’s shop, Monticello, Albemarle County, Virginia, ca. 1798. Mahogany. H. 29 1/2", W. 37 1/4", D. 29 7/8". (©Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The base of this table may have been made in Thomas Burling’s workshop.

Upper section of a reading stand, attributed to Thomas Burling, New York City, 1790. Walnut. Dimensions closed: H. 11", W. 13 3/4", D. 14 1/4". (©Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The tripod base is modern.

Reading stand illustrated in fig. 30, opened. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

David Roentgen, table à la tronchin, Neuweid or Paris, 1780–1795. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, walnut, and cherry, with oak and pine; bronze, brass, iron, and steel. H. 31 7/8", W. 44 1/8", D. 27 1/2". (Courtesy, Cooper-Hewitt Design Museum, Smithsonian Institution.)

Detail of a detachable leg on a game table, attributed to David Roentgen, Neuweid or Paris, 1780–1783. (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

David Roentgen, bureau a cylinder and fauteuil de bureau at Chatsworth House, Neuweid or Paris, 1783–1784. Unidentified wood, mahogany, gilt bronze, leather. (Reproduced by permission of Chatsworth Settlement Trustees/Bridgeman Images.)

Thomas Burling, cylinder desk, New York City, 1789. Mahogany, mahogany veneer with pine, and maple. H. 66", W. 62”, D. 35". (Courtesy, Atwater Kent Collection at Drexel University, The Historical Society of Pennsylvania Collection; photo, Robert C. Lautman.) The replacement legs are shorter than the originals.

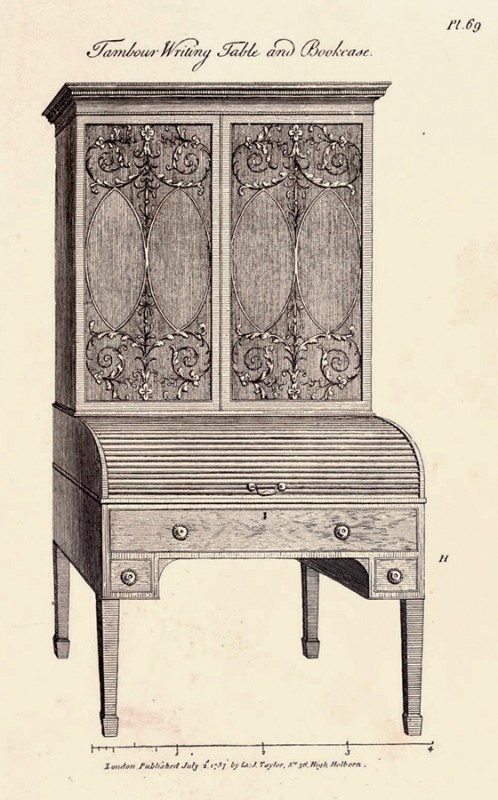

Design for a “Tambour Writing Table and Bookcase” illustrated on plate 69 of George Hepplewhite’s Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Guide (1788). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Standing desk, probably Williamsburg, Virginia, ca. 1770. Mahogany with yellow pine. H. 45 7/8", W. 36", D. 23". (©Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Harrison Higgins Jr., tambour writing table and bookcase, Richmond, Virginia, 2017. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with tulip poplar. H. 91 15/16", W. 44 1/4", D. 24". (©Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This piece is modeled on an example from Thomas Burling’s shop.

Robert R. Self, pair of dining tables from a set of seven, Albemarle County, Virginia, 1992. Mahogany with oak. Dimensions of pair closed: H. 29", W. 52", D. 4 3/8". (©Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These tables, copies of the originals which are privately owned, have elliptical leaves, indicating they are end sections. Five rectangular sections could be introduced to make a larger table.

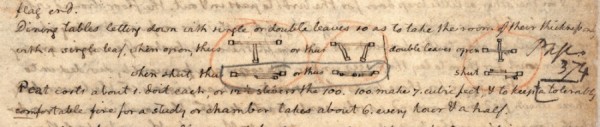

Thomas Jefferson, “Notes on a Tour through Holland and the Rhine Valley,” 1788. Ink on paper. (Courtesy, Thomas Jefferson Papers, Special Collections Research Center, William & Mary Libraries.)

Thomas Burling, revolving armchair, New York City, 1790. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with ash; iron and brass. H. 48", W. 25 7/8", D. 31". (©Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

“250th Anniversary of New York City is also the 100th Anniversary of City Hall—Historic Relics which the Old Building Contains,” New York Tribune Illustrated Supplement, May 24, 1903. (Courtesy, Library of Congress.) The speaker’s or vice president’s chair was made by Thomas Burling in 1789.

Cabinet, Monticello, Albemarle County, Virginia. (©Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Burling’s shop made the revolving armchair, revolving stand, sofa, and possibly the frame of the revolving writing table.

Thomas Burling, writing table, New York City, 1790. Mahogany with tulip poplar. H. 28 3/4", W. 33 1/4", D. 33 1/2". (Collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing the construction and drawers of the writing table illustrated in fig. 44.

Thomas Burling, sofa, New York City, 1790. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with poplar. H. 38 1/2", W. 57 1/4", D. 27 1/2". (©Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

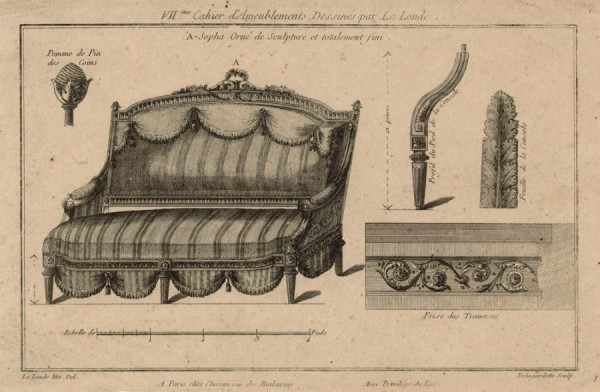

Design for a “Sopha orné de sculpture et totalment fini” illustrated in Richard de La Londe, Oeuvre diverses de LaLonde (1776–1788.), 2: ch. 7. (Courtesy, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.)

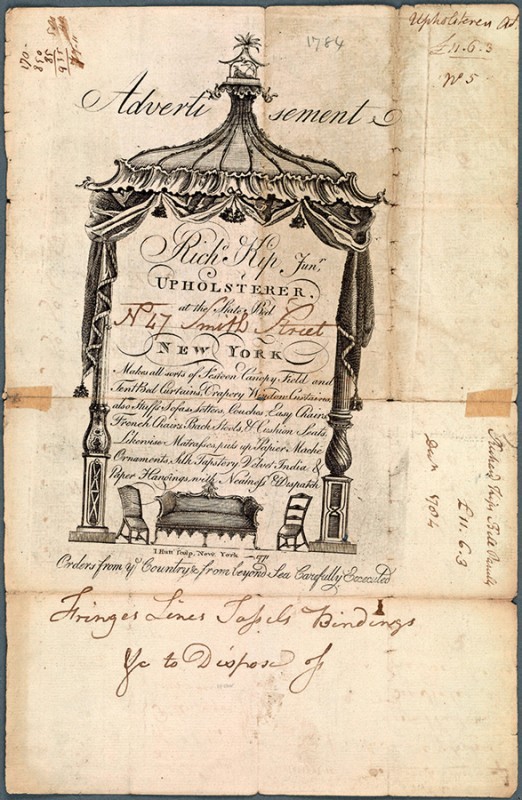

Advertisement for “Richard Kip Jr. Upholsterer,” New York City, ca. 1770. (Courtesy, New York Public Library.)

Windsor armchair, retailed by Richard Kip Jr., New York City, 1786–1790. (Private collection; photo, Winterthur Museum.) Remnants of Kip’s label appear under the seat.

Anne-Marguerite-Henriette Hyde de Neuville, Corner of Greenwich, New York City, 1810. Pen, ink, and watercolor on paper. 7 5/16" x 13". (Courtesy, New York Public Library.)

Detail of fig. 50, showing a three-bay house with a side passage like the one shown in Jefferson’s house plan in fig. 52.

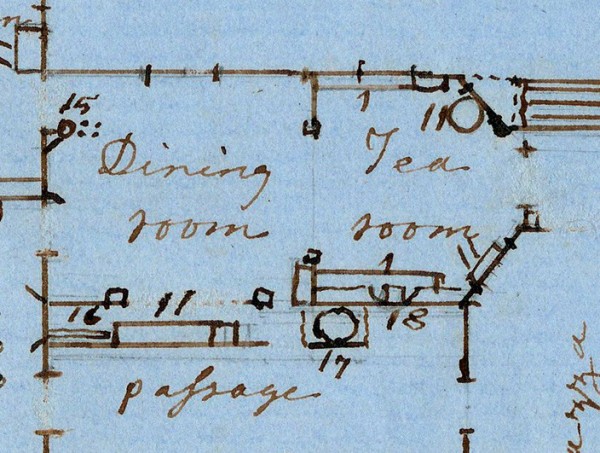

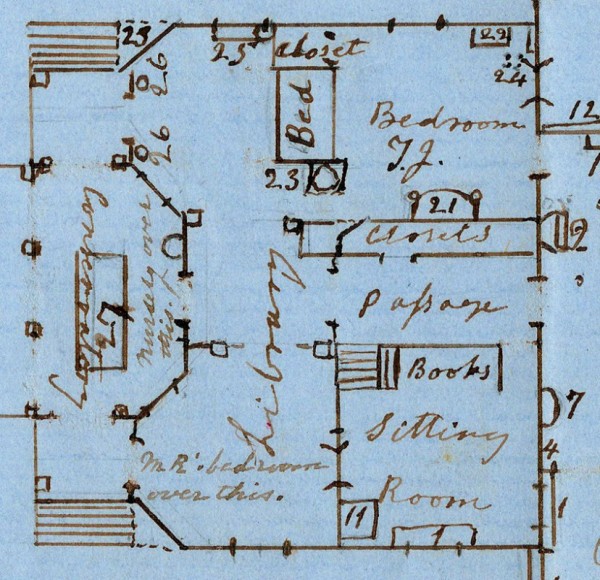

Thomas Jefferson, plan of the first and second floors of 57 Maiden Lane, New York City, 1790. Ink on paper. 9 1/8" x 11 15/16". (Collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society.)

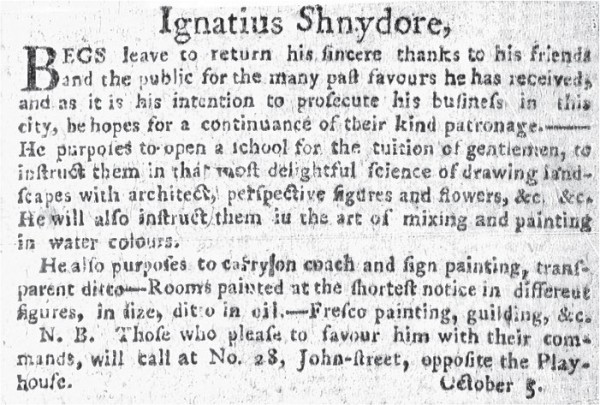

Advertisement for Ignatius Shnydore, Daily Advertiser, Political, Historical and Commercial (New York), October 5, 1789. (Courtesy, NewsBank/Readex.) Shnydore identifies fresco painting as one of his talents.

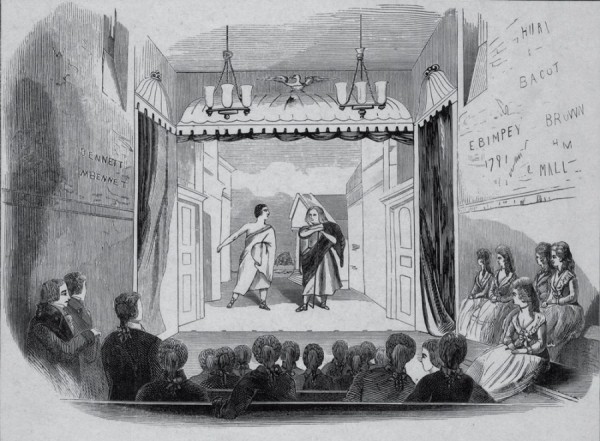

Two Figures in Roman Costume on Stage at the John Street Theater, New York City, ca. 1800–1850. Wood engraving. Ink on paper. 5 1/2" x 7 1/4". (Courtesy, New York Public Library.) This is a view of a classical play staged ca. 1791. The backdrop may be a representation of Shnydore’s perspective painting.

Library at Monticello, Albemarle County, Virginia. (©Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Jefferson installed the New York furniture in his private suite.

Mather Brown, Thomas Jefferson, London, 1786. Oil on canvas. 36" x 28". (Courtesy, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.) This painting portrays Jefferson when serving as minister to France.

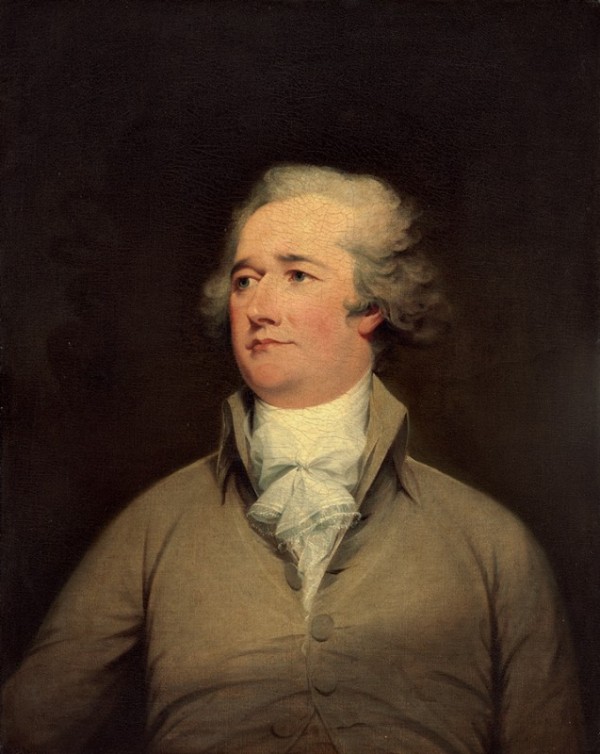

John Trumbull, Alexander Hamilton, New York, 1792. Oil on canvas. 30" x 23 13/16“. (Courtesy, National Gallery of Art.)

Jane Braddick Petticolas, View of the West Front of Monticello and Gardens, Virginia, 1825. Watercolor on paper. 13 5/8" x 18 1/8". (©Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello.) This presents an idealized view of life at Monticello during the final years of Jefferson’s life.

Parlor at Monticello, Albemarle County, Virginia. (©Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Dining room at Monticello, Albemarle County, Virginia. (©Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Alcove of the dining room illustrated in fig. 60. (©Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Cornelia Jefferson Randolph, “Plan of the First Floor of Monticello,” ca. 1826. Ink on paper. 8 1/4" x 13". (Courtesy, Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.) This detail shows how the console, sideboard (no. 11), and dining tables (no. 16) were stored in the dining room alcove.

Harrison Higgins Jr., reproduction of a French console table. Richmond, Virginia, 2009. White pine with poplar. H. 34 1/2", W. 50", D. 20". (©Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Cornelia Jefferson Randolph, “Plan of the First Floor of Monticello,” ca. 1826. Ink on paper. 8 1/4" x 13". (Courtesy, Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.) This detail shows the original location of the octagonal writing table surmounted by the square pupitre as well as the overall arrangement of Jefferson’s private suite. The sofa attributed to Burling is no. 25 on the plan, situated in the cabinet.

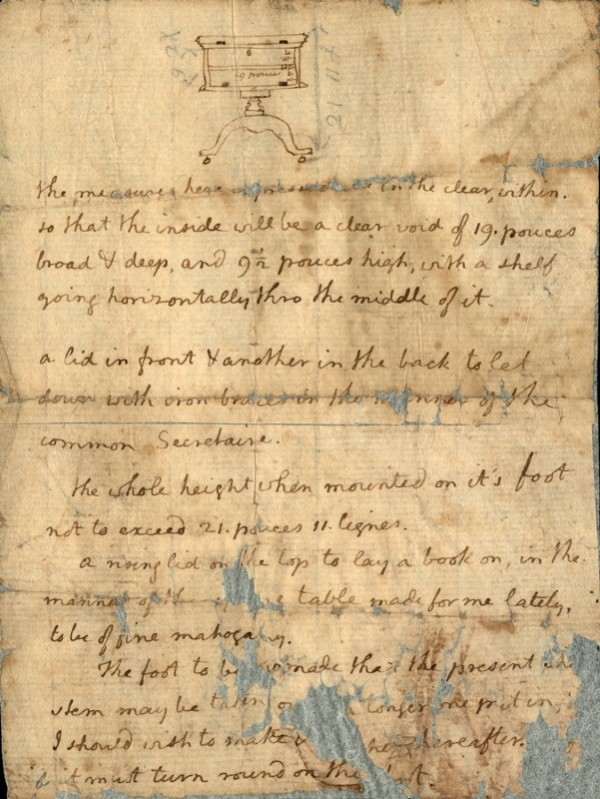

Thomas Jefferson, “Design for a Desk,” Paris, ca. 1785. Pen and ink on paper. 4 1/2" x 6". (Courtesy, Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.) This is Jefferson’s commission drawing and notes for his pupitre, used to record and store correspondence.

Harrison Higgins Jr., reproduction pupitre, Richmond, Virginia, 2017. Mahogany with tulip poplar. H. 22 3/8", W. 20", D. 20". (©Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The original object has not been located.

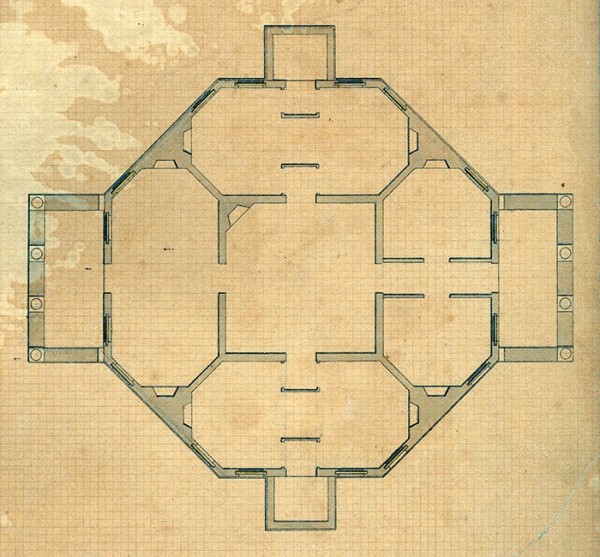

John Neilson, “Plan of Poplar Forest,” Bedford County, Virginia, 1819. India ink on hand-ruled graph paper. 11 1/2" x 9". (Courtesy, Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.)

Revolving table, attributed to John Hemmings, Monticello, Albemarle County, Virginia, ca. 1815. Cherry and walnut with yellow pine. H. 28 1/2", D. 35 3/4". The top features an inlaid square in contrasting wood. (©Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

SURROUNDED BY CRATES and barrels, chairs wrapped in mats, boxes of books, and Virginia hams, Thomas Jefferson drafted a packing list of his furnishings (fig. 1) awaiting shipment from the federal capital of New York City, where he was serving as secretary of state, to the new one of Philadelphia. It was August 31, 1790, and he was surveying the contents of his rented house. Despite both his cramped quarters and the fact that the furnishings of his house in Paris, where he had lived while serving as minister to France, were being shipped to him, Jefferson had been shopping. New evidence reveals that he acquired dining furniture and study or writing furniture from New York City workshops, furnishing what he considered the more important spaces in the house—the dining room, library, and study—and thus ensuring fully functioning rooms outfitted for entertaining and work. It might well have been reasonable for him to acquire furniture to facilitate correspondence and recordkeeping, given his role as a diplomat. However, classifying a suite of dining furniture as a necessity speaks to Jefferson’s masterful use of dining as an essential tool for diplomacy. Indeed, the move that necessitated this packing list was, at least in part, the result of a dinner Jefferson hosted for James Madison and Alexander Hamilton. Jefferson went to great lengths to decorate and furnish essential rooms in his rental home, because the domestic setting is where he preferred to stage political negotiations and to write. Therefore, when the need arose, he had a furnished room ready for him to enact dinner table diplomacy. This room recently has captured the national imagination as “The Room Where it Happens” from the musical Hamilton, outfitted with brand new furniture from New York shops, including side chairs (fig. 2) that are at Monticello today.[1]

When the packing list that Jefferson had drafted that steamy August day surfaced in 2007, it set in motion a years-long project to puzzle out the specifics of the objects and to identify the originals, some of which remained secreted in Monticello’s collection. Essentially the Rosetta Stone for a large group of furniture, this slight document provided significant new facts and clues for what Jefferson acquired during the scant five months he lived in New York. Primary furniture on the packing list includes a sideboard, dining tables, sets of side chairs and armchairs, Pembroke tables, an octagonal writing table, a pair of small sofas that could be disassembled, a revolving chair, a reading stand, and a tambour writing table and bookcase. This essay will analyze the New York packing list, in conjunction with related primary source material, to identify what furniture Jefferson purchased there and from which workshops. It will attribute an entire group of furniture to Thomas Burling, some of which is in the collection at Monticello, and share examples of modern furniture commissioned to stand in for lost New York originals. Finally, this analysis will consider Jefferson’s motivations, both personal and political, for his decisions on how to furnish both his temporary home on Maiden Lane in New York and his plantation home, Monticello, in Albemarle County, Virginia.

Part I: The New York Packing List

Officially identified as Thomas Jefferson’s List of Packages Sent to Philadelphia from New York, 31 August 1790, or simply the New York packing list, the document was unknown to scholars and editors of the Jefferson Papers. It had never been tracked, cataloged, or transcribed. It serves as a finite record of furnishings acquired in New York and readied for shipment to Philadelphia; it also provides evidence of the huge effort by the United States government to physically move all the clerks and secretaries, cabinet members, congressmen, and president, along with the records and furniture, from New York to the new capital city that Jefferson helped establish.[2]

Henry Remsen Jr., chief clerk in the Department of State under Jefferson, oversaw Jefferson’s moving arrangements. An exchange of memoranda outlines plans for the move beginning in late August 1790. Remsen’s memorandum sought guidance regarding Jefferson’s furniture: “Mr. Jefferson will please give H. R. junr. any directions he may chuse [sic] to leave with him, respecting the removal of his furniture to Philadelphia, the payment of the transportation of it there &c.” Jefferson asked him to watch out for his furniture from Paris and have it sent along with the New York lot. The packing and shipping of eighty-six crates took so long to arrive that they were safely redirected to Philadelphia. Jefferson set an arrival deadline of October 25, which he met because on the first and fourteenth of that month he paid for “cartage Mr. Jefferson’s furniture . . . to the wharf.” Within the context of these two memoranda, it is apparent that Jefferson included the New York packing list as an attachment for Remsen. The verso of the list is inscribed by Remsen “Mr. Jefferson’s Directions/August 31. 1790.” The annotation “directions” clarifies that the New York packing list was part of the written instructions Jefferson issued.[3]

The timing of the move and the documentary evidence—including the packing list, memoranda, and account of moving expenses—confirm that the objects on the list were acquired in New York. Because there is no evidence that Jefferson brought furniture from Virginia, and his French furniture had yet to arrive, the contents of the crates and packages had to have been acquired in New York (the hams excepted). This revelatory document lists what furniture types Jefferson purchased, but more importantly it provides invaluable clues as to size, color, and maker of an entire body of work.

Crated Furniture

In composing the list, Thomas Jefferson gave precedence to the crated objects, especially crate numbers one through eight, which contained the most significant examples from his newly acquired furniture collection. Each crate was numbered, supplemented by a brief title, dimensions in inches (arranged in order of width, height, and depth), and the total cubic feet of the crate. The dimensions were key for estimating the size of the original objects. Most of the furniture was crated individually, except for multiple Pembroke tables in crate number two and dining tables in crate number six.

This study began by focusing on crate number seven. Noted only as “chair,” the overall dimensions suggested Jefferson’s tall revolving chair, attributed to Thomas Burling (fig. 41). When faced with a laconic title like “chair,” the dimensions dramatically narrowed the search. It is important to note that when ordering the dimension columns, Jefferson used width x height x depth, rather than the modern practice of placing height first. All the crates had an overall dimension approximately two inches larger than the object within, providing an allowance for packing materials. We do not know who made the New York crates, but they may have looked like the ones illustrated in an eighteenth-century view of a box maker’s workshop published in Diderot and d’Alembert’s Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers (fig. 3).[4]

Flat packing

Jefferson’s care in recording dimensions sometimes offered an invaluable way-finder, as happened with crate five, where the recorded dimensions are just inches larger than the full-sized sideboard it contained. But most of the crates, five out of the eight, had perplexing dimensions that did not seem to comport with the titled contents. Progress stalled until sketches of crate number eight provided a visual cue. Jefferson labeled it “Writing table,” noting the dimensions as 39 x 33 x 7. Initially, the contents appeared to have been a rectangular portable desk, but when is such a desk so improbably wide or tall—or narrow, seven inches or less? By visualizing the shape of the crate while considering that it held a table, it became apparent that the top of Jefferson’s octagonal writing table (fig. 4) fit perfectly within. The overall dimension of the top is thirty-one inches long, and it is six inches deep, making it a secure fit in a crate that is approximately one inch larger. But what of the extra five inches in the width? Why was it thirty-nine inches? The answer proved to be flat packing. The crate contained not only the top, which easily lifts off the base, but the pedestal and three detached legs in the void next to the top (fig. 5).[5]

Knowing that the writing table was disassembled and flat-packed for shipping was a vital breakthrough, providing a methodology for identifying most of the objects on the list. In studying crate dimensions and titles, the list of objects that were shipped flat-packed or partially disassembled include: a tambour writing table with detachable legs; two sofas with detachable backs and with arms and arm supports; a cube-shaped reading stand and base with detached legs; and the writing table. Jefferson as patron would have dictated these features as part of his commission discussions with the cabinetmaker. Why did Jefferson ask for features that cost more in time and expense? Timing suggests that he was eager to create his own versions of the multi-functional and convertible furniture that he saw in Paris. Re-inventing furniture forms with enhanced efficiency and convenience appealed to Jefferson, who embraced the Enlightenment spirit, where reason and observation were the basis for positive change. Furniture that could be shipped flat was both useful and, ideally, cost effective.[6]

Uncrated and Wrapped Seating

The New York packing list includes forty-six chairs, thirty of which were painted Windsor chairs being sent to Monticello. Of those bound for Philadelphia, Jefferson notes “5. pr single chairs. mahogany in mats” as well as “6. arm chairs. do.” Most puzzling are the entries for “1. green stool” making a total of two. None of this seating was crated; instead, it was shipped padded and wrapped in mats, probably made from plaited rushes.[7]

Looking for ways to cut shipping costs, Jefferson consulted with Abigail Adams, who had overseen the packing of her and John’s furnishings when they departed London for America in February 1788. She was nearly overwhelmed by the enormity of it all, writing, “to part with our furniture would be such a loss, & to take it is such a trouble that I am almost like the Animal between the two Bundles of Hay.” And yet she persisted, learning spaceand cost-saving measures in the process. Jefferson shared her advice with his secretary, William Short, who handled closing out Jefferson’s affairs in Paris, and it is useful to quote it at length:

Mrs. Adams tells me that chairs are best packed in open frames made as you have seen crates for earthen ware; only that, for chairs, there need be no middle bars at all. Two chairs are lapped one in the other, the silk being previously covered with coarse linen, then put into these frames and covered over with mats. I have thought however that if two chairs were lapped as beforementioned, and then put into a box, there could be other things packed in the hollows under the bottoms, and thus the chairs be better preserved, and perhaps the packages not cost more on the whole, as otherwise boxes must be made express for the other things. Be so good as to weigh maturely this proposition, with Petit, and do what is best. It concerns the silk chairs and couches only. Those of leather and velours d’Utrecht may come in frames as Mrs. Adams proposes.

Jefferson writes that the set of “single chairs” on the New York packing list were wrapped in mats, and it is likely that both sets of seating were packed in this manner.[8]

Shipping Marks

All the crates, barrels, boxes, and wrapped seating required a visible and easily identifiable owner’s mark to ensure that the shipment arrived in its entirety at the appropriate destination. Thomas Jefferson’s individualized mark, “T. I.,” was painted or branded onto everything he shipped or received. This mark, with variations over time, appears on shipping manifests, invoices, and on a brief list in Jefferson’s own hand. For example, in December 1790 on his list of French furnishings to be shipped to Richmond he notes “T. I. No. 77. A marble pedestal.” There is one unusually rare example of Jefferson’s brand, and it is impressed into the inner surface of the left arm of an armchair sent from France in 1790 (fig. 6). Perhaps perplexed by the mark “T▼J” on the chair, descendants misidentified it as an homage carved by Nicholas Philip Trist upon the death of his grandfather-in-law. “After Mr Jefferson was Confined to his room, the last evening he ever sat up during his last illness this sad a.m. before the chair was moved my father cut the initials ‘T. J.’ on the chair which grandpapa had used the last he ever sat in.” Recent work on branded furniture, with brands of both owners and makers, reinforces the argument that this is a rare example of Jefferson’s shipping mark, probably branded onto this chair when it left France, uncrated but wrapped. This is the only known example of the brand, which may have been limited to the French seating—those pieces have been heavily refinished.[9]

Miscellaneous Items

Household miscellany was sent to Philadelphia along with the furniture. The packing list includes barrels and a hogshead, a box of Jefferson’s, and “two boxes of Mr. Madison’s.” In the middle of this list are stores of food supplies, including a “cash of coffee containing about 100 lb.” In crate number nine, fifty-eight pieces of Virginia bacon and ham filled four barrels and a single box. Jefferson confirmed receipt of these delicacies, noting that “I have received my bacon and venison hams here in good condition, for which I must thank Mrs. Lewis in particular.” The hogshead was packed with “about a gross of empty bottles. 10 bottles cyder.” Box number ten contained “earthen ware. some chine. Candlesticks.” The box of dishes accompanied the “kitchen tables.” The fireplace equipment, “handirons &c.,” was probably rolled inside the mattresses that are listed immediately below. Recorded between the mattresses and kitchen tables are “servants bedsteads.”[10]

Omissions: What Is Not on the List?

Having established that the list encompasses Jefferson’s purchases in New York, there are striking omissions of furniture. Most evident is the lack of bedroom furniture except that noted for the servants, nor bedding. Case furniture, such as a chest of drawers or night table, is absent too. Furniture forms associated with parlors are absent, except for Pembroke tables. Several explanations are possible, such as that the rental house came partially furnished, or more likely, Jefferson rented essentials like his bedstead and bedding from an upholsterer, who traditionally offered that service. Additionally, Jefferson was probably content to make do with a moderately sparse interior, knowing that his French furniture was forthcoming.

New York Craftsmen Patronized by Jefferson

Whom did Jefferson hire to decorate and furnish his rental house in New York? Here, as we have seen, the New York packing list is mute. Before the list came to light, scholars knew that Jefferson bought furniture in New York because craftsmen like Richard Kip Jr. and Thomas Burling appear among his financial records called the Memorandum Books. In these account books, he made brief entries with names, dates, and amounts, seldom providing specifics on what he purchased. Corollary documentation, such as invoices, rarely survives, making specific information about these transactions scarce. Conversely, while the New York packing list provides definitive information on what types of furniture Jefferson bought in the city, it lacks specifics about makers. By comparing these two resources, along with correspondence, floor plans, and recollections of family and visitors, and by studying the objects themselves, it is now possible to make both new identifications and attributions for some of the group. In researching these craftsmen, a significant amount of new information came to light about the furniture trade in New York, as well as the circumstances for Jefferson’s purchases. The Memorandum Books contain entries for five New York craftsmen whom Jefferson patronized: Windsor chair maker Andrew Anderson; cabinetmakers Elbert Anderson (or Alexander Anderson), Thomas Burling, and Samuel Prince Jr.; and upholsterer Richard Kip Jr.

Anderson: Probably Andrew Anderson

On July 16, 1790, Jefferson noted in his Memorandum Book, “Pd. Anderson 2 1/2 doz. green chairs &c. £12-10.” Jefferson was probably trading with Andrew Anderson, a Windsor chair maker active in New York circa 1786–1811. The New York packing list includes a set of green Windsor chairs. In August 1790 Jefferson wrote to James Brown, his factor in Richmond: “I send from hence 2 1/2 doz. Windsor chairs, which I have desired to be delivered to you, and will beg the favor of you to forward them as quick as you can to Mr. Lewis’s or to Monticello.” Given the large size of the set and the moderate cost, they were probably painted bow-back side chairs with baluster shaped legs. Examples of Anderson’s Windsor chairs have not been identified, but Jefferson’s may have resembled those made by the New York shop of John Always and Joseph Hampton (fig. 7).[11]

Anderson: Probably Elbert Anderson, or Possibly Alexander Anderson

Jefferson noted on August 30, 1790, one day before he compiled the New York packing list, that he had paid Thomas Burling for “cabinet work,” followed by an entry to pay “Anderson do. £10.” Jefferson was settling his accounts with two New York cabinetmakers, Burling and, probably, Elbert Anderson. Evidence suggests that this transaction was for the set of six armchairs that appear on the New York packing list. One candidate for their maker is Elbert Anderson, who on February 5, 1788, announced (fig. 8) that “he has lately entered upon his former occupation” and ensuring his “employers” that “He makes plain, circular, inlaid, and carved work of all kinds that belong to the cabinet and chair making business.” In reestablishing his furniture business, Elbert had to compete against more established cabinetmakers like Burling as well as the “auction furniture” market, which apparently relied on misleading claims to make sales. Elbert used the word “circular” as an identifier, an adjective that often appears in Thomas Shearer’s The Cabinet-makers London Book of Prices, as in a “circular pier table.” Elbert may have owned a copy of the book, which was published the same year he returned to the trade. In July of 1788, either Elbert or Alexander Anderson was one of the leaders of the contingent of cabinetmakers in the great parade held “In Honor of the Constitution of the United States.” In addition to the marchers, there was a horse-drawn stage featuring cabinetmakers building a cradle and table, which they finished by the parade’s end. A painted banner with a representation of a furniture wareroom was emblazoned with the motto “Unity with Fortitude.”[12]

The New-York City Directory for 1790 lists Elbert Anderson at 53 Maiden Lane, just steps away from Jefferson’s house. At that time Anderson had a large household, which included four free white males over sixteen, four free white males under sixteen, five white females, and notably, three enslaved workers. Historian Shane White’s study of slavery in eighteenthcentury New York has identified that one in five households in New York City owned at least one enslaved person, and that slave ownership prevailed from the highest to the lowest classes. White further states that the largest group of slaveholders in 1790 (and probably for most of the eighteenth century) was artisans rather than merchants. As a slaveholder and an artisan, Anderson embodied these data, and his holdings exceed one further statistic. White cites that among New York City’s slaveholders, half only owned one enslaved person, but Anderson surpassed that cohort by holding three people in bondage. These unnamed slaves worked for Anderson, and some or all of them were presumably engaged in his cabinetmaking business. Enslaved laborers may have been responsible for parts or entire pieces of the furniture coming out of this workshop. If this supposition is correct, Anderson was attempting to capitalize on the system of enslaved labor by keeping his costs down and his profits high.[13]

Anderson and his workshop produced fine case pieces such as the labeled mahogany secretary-and-bookcase illustrated in figures 9 and 10. The engraved scene on his label features a chest of drawers surmounted by a shield-back side chair with an ornate splat adorned with swags and Prince of Wales feathers. This design was popular in New York, and numerous chairs in this pattern were erroneously attributed to Anderson based on this evidence. Another set of chairs with an Elbert Anderson attribution (fig. 11) belonged to Alexander and Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton. Derived from plate 11 in Hepplewhite’s The Cabinetmaker and Upholsterer’s Guide, they feature a straight crest and light wood inlay instead of carving. It is probable that Anderson also owned a copy of Hepplewhite’s Guide or had ready access to one.[14]

Given Anderson’s large operation and his prominence as a chair maker, Jefferson’s unspecified purchase, presumably with him, may have been the set of six shield-back armchairs. Three chairs are extant (fig. 12), confirming a New York origin. They are patterned after plate 9 in Hepplewhite’s Guide (fig. 13). The shield back on Jefferson’s chairs is the most striking element, with a foliated-carved lunette from which four fluted and imbricated ribs or banisters extend to the crest rail. The base of the shield is rounded, but the crest is slightly elongated. Serpentine arms terminate in a rosette and rest on attenuated curved supports with molded, not reeded, treatment. The arm supports transition behind front legs that are fluted and tapered, with spade feet.[15]

This design was interpreted widely by New York chair makers but came to be closely associated with Robert Carter, a respected cabinetand chair maker who, like Anderson, was one of the leaders of the great procession in 1788. In 1790 his operation was situated on Fair Street, and his household included six free white men under sixteen and four over, as well as five females and one enslaved worker, who may have labored in his shop. Robert Carter was also Thomas Burling’s brother-in-law and sometime business partner. Because Carter and Burling had both personal and professional ties, and because Jefferson’s chairs resemble Carter’s well-documented commission for Peter Elmendorf as well as examples attributed to Burling (fig. 14), it is possible that either one of them produced Jefferson’s set. However, Jefferson’s financial records strongly suggest that of all the examples on the packing list, the sum paid correlates to the small set of armchairs. Therefore, it is probable that Anderson, probably Elbert and his shop, not Burling or Carter, was responsible for this interpretation of a New York favorite.[16]

An alternative candidate to Elbert is Alexander Anderson, a joiner and cabinetmaker active in New York City as early as 1786. Alexander is listed as a cabinetmaker in the 1790 New York City directory, and he too had a Maiden Lane address. According to the Federal Census, his household included five white males above sixteen, three under sixteen, and four white females, but no enslaved individuals. Alexander’s best documented work was for Charles Thomson, Jefferson’s friend and secretary of the Continental Congress. In 1786 Anderson billed Thomson on three separate occasions (fig. 15) for work that included: making a breakfast table and putting finish on two dining tables, building boxes, “jobs done about the House,” and “putting banisters into chairs.” While this is compelling evidence that Thomson hired him, the type of work provided does not comport with what we know is on the New York packing list. Having two Andersons on Maiden Lane in Jefferson’s daily orbit is problematic, but Elbert Anderson likely made this sale.[17]

After years of service and wear, the set of armchairs was broken up at the Monticello dispersal sale held in January 1827. The executors organized a multi-day sale of Jefferson’s personal estate in order to begin paying off the huge debt he had left his heirs. Records from this sale are scant, but that said, executors were eager to sell furnishings and art from the public rooms, as well as livestock, farm equipment, and nearly all the enslaved workers on the plantation. The furniture from Jefferson’s private suite, however, was withheld from auction. Thomas Jefferson Randolph, grandson and executor for Jefferson’s estate, apparently took some or all of these armchairs to his neighboring home, Edgehill plantation. The surviving chairs stayed there until they were sold in the early twentieth century, with two pieces later entering the Monticello collection.[18]

Burling: Thomas Burling

Thomas Burling was tapped to fulfill most of Jefferson’s furniture commission, the latter visiting the cabinetmaker at his wareroom at 36 Beekman Street “at the Sign of the Chair,” near St. George’s Chapel. George Washington and Jefferson were just two of Burling’s prominent clients, making his workshop the premiere cabinet operation in New York. Jefferson’s 1790 Memorandum Book includes an initial payment to him on July 17: “Pd. Burling cabinet work in part £100.” At the end of the summer, Jefferson noted: “Pd. Burling cabinet work in full £43–12.” These two large payments, taken in consideration with the contents of the packing list, reveal that most of the furniture, not counting the sets of Windsor chairs and mahogany armchairs, came from Burling’s shop.[19]

Burling came from a prosperous family of Quaker tradesmen and landowners in New York City. He trained under Samuel Prince, one of the best cabinetmakers working in the pre-war era. Burling would later use this connection in his advertisements, touting the excellent training he received from Prince. Prince’s rococo-style label states he can be found at “the sign of the chest of draws” on Cart and Horse Street (fig. 16). As his apprentice, Burling would have spent years working in Prince’s shop, and perhaps living with his family. At about the time Burling’s apprenticeship ended, Prince advertised on February 15, 1768, “To be sold cheap, three likely negroes, a man 22 years old, a boy 13, and a wench 14 years. They can all be recommended for their honesty and sobriety. Enquire of Samuel Prince, cabinet maker.” The “likely” enslaved men may have worked in the shop alongside Burling. Such a personal encounter with the inhumanity of forced bondage likely contributed to Burling’s antislavery activism later in life. Evidence of his slaveholding suggests that Prince was not a Quaker. In 1772 he rented workshop space to John Sheybli (fig. 17), an organ builder who also repaired and tuned keyboard instruments. This arrangement may suggest that Prince built some of the cases for his tenant.[20]

Burling confidently entered the cabinetmaking business, which he proudly announced in December 1772: “THOMAS BURLING, Cabinet and Chair-maker, in Chapple-street, New-York, Has opened a yard of all kinds of stuff, suitable for country JOINERS, which proposes to sell on the most reasonable terms.” Eventually, master and apprentice became serious business competitors, with both men vying for customers in the turbulent winter of 1775. That February Samuel Prince informed the public that he took orders for the West Indies, and that “He has now on Hand for SALE case work in the best mahogany, as well as an assortment of chairs.” On March 16 Burling stepped up and placed ads in two newspapers, one illustrated with an eye-catching image of a ribbon-back mahogany side chair (fig. 18). He informed the public that he too had furniture on hand, emphasizing that it was “made of the best mahogany, which he proposes to sell as cheap as any man in this city.” Burling also promoted his “Mahogany Yard,” where he sold lumber to the trades—a product line that Prince did not offer. The timing suggests that both men were experiencing economic uncertainty concomitant with the political unrest that descended into armed conflict in April 1775. During the war years, both shops closed operation, with Burling and Prince and their families leaving the city. Prince died in 1778, leaving the cabinetmaking field open for Burling once the war ended.[21]

After a tumultuous five years, Burling announced the reopening of his business on January 10, 1785, announcing that “He has returned to this city, and resumed his former calling, at the sign of the Chair, near the Chapel, on Beekman street.” He stated that he was hiring the best workmen, that he trained under the best cabinetmaker, Samuel Prince, and that he had a stock of mahogany and other furniture, and the wood itself, for sale. By November 1786, he announced the opening of a wareroom (fig. 19) “for the convenience of strangers, and others, who may resort to settle in this city.” Burling offered a wide selection to relieve the out-of-towners from having to purchase “new furniture at these public vendues.” Prince the elder was no longer competition, but Burling now had to contend with the auction system, where groups of new furniture could be sold quickly and cheaply. Burling may have been referencing Frederick Jay when he set about to challenge the auction business. Jay is described as a “vendue master” in the New York directory. On October 26, 1786, Jay announced his upcoming auction of “a large variety of elegant Household Furniture” including “mahogany dining chairs and breakfast tables, sideboards, and more.” The consignor or source of the furniture is not listed, but this type of auction undercut cabinetand chair makers’ business. Burling’s solution was to adopt the wareroom system, meaning more space, more risk with stock on speculation, and more craftsmen to pay, all to lure customers away from the auctions. He introduced a wider variety in his offerings, as suggested by the image of a bow-back Windsor armchair he selected for this advertisement. The “other furniture” available could have been Windsor seating. Burling’s wareroom apparently had something for everyone. The auction market remained an issue as late as 1788, when Elbert Anderson publicized his wares as a sound alternative to those sold at vendue (fig. 8).[22]

By 1790 Burling’s wareroom operation was a success, with sales surpassing one hundred pieces of furniture to the federal government for the president’s house in just one exchange. However, to fulfill the huge demand, Burling supplemented his own shop’s output by selling furniture imported from Philadelphia. He retained this success despite a near-catastrophic blaze on the night of January 1, 1789, when “a fire was discovered in a chamber occupied as a work-shop in the house of Mr. Burling, Cabinet-maker, Beekman street; the chamber with its contents was nearly destroyed.” One correspondent noted that “Five young lads who slept in the upper story with difficulty escaped from thence into the street by means of a bed cord.” It is interesting to note that there were rope beds upstairs, and that the five young men may have been apprentices. One of the lads could have been cabinetmaker William Whitehead, who recounted that when he was about twelve years old and newly arrived from St. Croix, he apprenticed himself to Burling in circa 1785. On January 16, Burling thanked his neighbors for their help, assuring them “that altho’ I met with a loss, and was a few days deprived of pursuing my Business, yet I suffered to little of my STOCK of MAHOGANY and READY MADE FURNITURE, that I am again enabled to resume my Business as usual.” Business was so good that by November 1789 Burling could advertise that he had “lately employed an additional number of workmen, that he might be the better enabled to accommodate strangers ” Some of these workers may have been among the seven white males over the age of sixteen (but no enslaved persons) who are listed as part of the Burling’s household on the 1790 Federal Census.[23]

Unlike his competitor Elbert Anderson, his teacher Samuel Prince, and his in-law Robert Carter, Burling did not rely on enslaved labor either at home or in his workshop. On the contrary, he aligned himself with the antislavery movement, becoming a member of the New-York Society for Promoting the Manumission of Slaves. Furthermore, Burling’s enterprise included at least one person of color, presumably a free man: “William Miller, a coloured man, who has been in the family of Thomas Burling & Son upwards of Sixteen years, was ordained to the work of the ministry.” This ordination took place in 1808, but prior to the ministry, Miller probably worked for or had been “in the family” of the Burling and Son cabinet shop that was formed in 1791. In addition to Burling’s sons Samuel, William, and Ebenezer, the patriarch may have also trained William Miller. One wonders what Thomas Burling, the antislavery activist and Quaker, thought of his elite customers from Virginia and New York City who were slaveholders.[24]

Burling did not just make and sell mahogany furniture; he was also active in the trade of mahogany, the highly desirable wood harvested in the Caribbean and Central America. Burling needed a large supply of imported mahogany, the wood most popular with his clientele, for his extensive furniture operation,. He stocked it for his own output and he also sold it to other cabinetmakers and carpenters. In doing so, Burling participated in a system that relied on the labor of enslaved workers to manage, harvest, process, and ship mahogany to points in the Atlantic world. Timber sent from the forested land claims in Central America was harvested by enslaved laborers working under extreme hardship and dangerous conditions. Burling and his peers certainly knew of the ties between slavery and the mahogany trade, but his market demanded this exotic import despite the human cost. This conflict of personal and professional ideology probably troubled Burling, yet mahogany remained the mainstay material of his shop.[25]

The furniture itemized on the New York packing list is overwhelmingly mahogany, except for the walnut reading stand, painted Windsor chairs, and servants’ bedsteads. There are a few reasons for Jefferson’s choice of mahogany. First, as scholar Ann Smart Martin has shown, mahogany, with its “warm rolling effects,” was a luxury wood and a status symbol, even in trend-setting France, where furniture in the English style was popular. Secondly, Jefferson had already collected a substantial group of mahogany furniture in Paris, mostly tables (fig. 20). A trestle table (fig. 21) with marble top and a mahogany base, is so Anglo-looking that it was formerly assigned a Philadelphia origin. Exemplifying Anglomania in France, this trestle table was made in Paris but in the English style. Jefferson frequently contracted with cabinetand chair maker Jacques Upton, and it is possible that Upton (an Anglo-Irish surname) was British. If this is the case, he would have been well suited to provide Jefferson with mahogany furniture in the English manner. A third reason for Jefferson’s choice is that he was surprisingly knowledgeable about mahogany, which would have been invaluable in an era when quality stock was not always so readily available. In his written commission for two desks from a London shop in 1789, he specified “the fineness of the mahogany to be more attended to than the price. The French spotted mahogany is the handsomest if to be had.” One of these desks survives (fig. 22), and it has a large single-board mahogany top, but not the Acajou moucheté or streaked plum pudding mahogany he hoped for. Jefferson’s appreciation of mahogany, which he used architecturally as well as for furniture, is borne out by how often he mentions it in his letters and reports—upwards of fifty times, far more than Washington, Adams, and Hamilton combined. Finally, the New York furniture aesthetic probably appealed to Jefferson, who was progressive when it came to improved functionality but tended toward the traditional in his aesthetic choices at this time. New York furniture, with its rather solid appearance and its celebration of clean-lined mahogany, may have been just what Jefferson wanted.[26]

Jefferson spent approximately £143 for all of the furniture from Burling, but what was he charged for individual objects and hardware? In April 1789 Burling sold a large group of mahogany furniture intended for the president’s house, and the surviving account of this sale offers helpful cost parallels. Some charges offer a one-to-one correlation: a fine sideboard cost £19; a large set of dining tables, £25; two sofas, £12; and “10 Mahogany Carved Chairs—£21.” Locks, castors, and the threaded hardware needed for detachable legs were an additional expense. Burling charged separately for “Brass Castors for the Sophay & Easy chair 3/15.” As many as thirty castors were required for Jefferson’s order.[27]

Stylistic evidence from the furniture noted on the New York packing list suggests that Thomas Burling owned a copy of George Hepplewhite’s Guide, either the 1788 or 1789 edition. When assessing surviving original furniture or comparable examples of the lost originals, Hepplewhite was and remains a major design resource. Furniture derived from this design book include side chairs and armchairs based on plates 5 and 9, a tambour writing table and bookcase based on plates 61 and 69, and a Duchesse seating arrangement from plate 28 (fig. 23). The sofa on plate 25 as well as the patterns for window stools and sideboard with innovative lead-lined drawers also relate to Jefferson’s group. Without an inventory of Burling’s shop, it cannot be confirmed, but his extant work suggests a connection between his shop’s output and Hepplewhite’s examplars.[28]

The New York packing list furniture that is attributed to Thomas Burling can be sorted into two groups: stock objects from his wareroom, and special commissions. The survey of this furniture below follows this paradigm, starting with furniture that was standard stock available in the wareroom, followed by furniture Burling produced in collaboration with his patron, Thomas Jefferson.

Wareroom Furniture Attributed to Thomas Burling’s Shop

The sideboard, the set of ten side chairs, and possibly the two Pembroke tables were wareroom stock. The type of sideboard that Jefferson owned appears to have been one of Burling’s standards, with three related examples extant. All are labeled, which also suggests they were stock in trade. The side chairs sold in pairs recorded on the packing list strongly suggest that there was a cache from which to choose. Little is known about the Pembroke tables, but this type of table was commonly available, and so those pieces are included here as wareroom selections. A succession of sleuths has searched for the sideboard, which was sold at the Monticello dispersal sale, but their efforts were hobbled by not having specifics about the piece. To make things more confusing, the quest for the lost sideboard caught the public’s imagination, so nearly fifty people have come forward claiming to have the original. The packing list evidence has finally pinpointed New York as the origin and Burling as the probable maker, and this provided enough evidence for Monticello to commission a reproduction (fig. 24).[29]

Jefferson helpfully titled crate five, “N°. 5. Side board.” The dimensions, which invert width and height, are “64. I. 42. I. 32. I.,” resulting in fifty cubic feet of crate. Knowing that the sideboard was relatively short in width eliminated grand examples of six feet of more, suggesting an object about 60 inches wide. The crate size and shape fit the normal proportions of a sideboard, eliminating flat packing. A search for Burling sideboards in this smaller size has yielded two or three comparable examples, all bearing Burling labels (figs. 25, 26). The sideboard shown in figure 25 is 38 1/2" high, 61 1/2" wide, and 27 1/2" deep, which would fit exactly into crate five with three inches of packing. Made of mahogany with tulip poplar and white pine, the case has a tripartite arrangement with deep faux drawers and real ones flanking a central cupboard. A pair of narrow drawers for linen sits directly beneath the top. The sideboard has tapered legs, spade feet, and brass hardware, but much of its aesthetic appeal comes from its figured mahogany. While not based on a specific design in Hepplewhite, this piece shares the refined simplicity of line with the functional innovations suggested for sideboards with drawers.[30]

Jefferson must have liked his new sideboard, because he used it in Philadelphia and later built an alcove in the dining room at Monticello to accommodate it. The sideboard appears on a plan of furnishings of the first floor of Monticello, and it is documented as being sold at the dispersal sale, when a young man named David Lacy promised to pay $31.50, due June 15, 1827. There is no evidence that he paid the debt, so it is possible that Thomas Jeff erson Randolph as executor took it to his home, Edgehill, later to be sold or claimed by a Jefferson descendant.[31]

Spared by the family from the dispersal sale, the entire set of New York side chairs has been returned to the dining and tea rooms at Monticello (fig. 27). They are recorded on the packing list as “5. pr single chairs. mahogany in mats.” Jefferson probably purchased this seating ready-made, in time for the momentous compromise dinner he hosted in June 1790. As previously discussed, these chairs are based on a Hepplewhite design. They feature a shield back that is slightly elongated terminating in a point, with a double-bead profile. The elongated shield sets them apart from Jefferson’s set attributed to Anderson. There is a tripartite splat with acanthus buds and tendrils centered by a quarter-round lunette with acanthus carving. The molded and tapered legs are reinforced with an H-shaped medial stretcher, plus one between the rear legs, and the chairs were covered in leather upholstery with decorative nailing. A second upholstery campaign, replicating the original nail pattern, is attributed to enslaved cabinetmaker John Hemmings. Archaeological evidence from the Monticello joiner’s shop includes twenty copper alloy upholstery tacks from the Jefferson era, with an additional twenty-one examples found in the north yard.[32]

The final examples of mahogany furniture from Burling’s wareroom may have been in crate two, marked “N°. 2. Pembroke tables. 36. I. 24. I. 31. I. 15 1/2 cub. feet.” Jefferson’s use of the plural “tables” and the crate dimensions suggest two examples, quite possibly a pair. Neither survives, at least in its entirety. The tables were probably nested with the legs facing each other. Jefferson recommended this arrangement for a pair of tables he ordered in 1789, “the small table to be put into the large one, both wrapped up in green bays, put into a tight box and that tied over with oil cloth.”[33]

The Pembroke tables remain an elusive mystery among the crated furniture. Neither table survives, and there is little evidence to suggest what they looked like or how Jefferson intended to use them. They could have been special orders, precursors to the Pembroke tables (fig. 28) made at Monticello for use at Jefferson’s retreat, Poplar Forest. This latter set of tables was designed to be used in tandem with the set of New York dining tables. Given that all traces of them are lost, it is possible they served as fodder for other projects. In 1801 Jefferson asked cabinetmaker Henry Ingle to alter a mahogany table by cutting it down. Ingle determined that his estimate was low so he wrote “I shall forbear cutting it until I hear further from you.”

One possibility is that one of the Pembrokes was reworked or cannibalized to create Jefferson’s unique writing table (fig. 29), which he later paired with the revolving chair and Windsor bench. The reworked table, or parts of it, is attributed to the joiner’s shop at Monticello. It has a circular revolving top with two clipped sides to allow it to fit close to the sitter. If this table started life as a Pembroke, then the base has been re-oriented to allow the depth to become the width. The base lacks evidence that it had a drawer, which is also like the tables for Poplar Forest (fig. 28). The side rails have a semicircular cut to make room for the bench and the sitter’s legs. The table has been fitted with casters to facilitate its movement over the bench. The base is H. 27", W. 22", D. 19", making it a good fit within crate two along with its mate. This writing table is in the cabinet at Monticello, part of Jefferson’s iconic writing group.[34]

Commissioned Furniture Attributed to Thomas Burling’s Shop

Jefferson gave his specially designed reading stand (fig. 30) pride of place on the New York packing list, noting, “N°. 1. paper press. 26. I. cube 10 cub.” Once thought to be the work of Monticello joiners, the packing list dimensions suggest that this “press,” or reading stand with lecterns, was made in New York. The form is essentially a simple walnut box with five lecterns, one at the top and four at the sides, and a base consisting of a pillar and three cabriole legs. The use of walnut is unique within the New York group, which raises the question of why not mahogany? Perhaps with this commission the emphasis was on functionality over aesthetics. After all, when in use it would be heavily obscured by papers. Could this choice be a cost-saving measure? With no documentary evidence that this stand was copied, it is probable that the top part of the reading stand, while atypical, is from New York, but the base is a replacement. When the top is closed it measures H. 11", W. 13 3/4", D. 14 1/4", nearly a cube. When the five lecterns or wings are open, the overall dimensions are H. 21", W. 29", D. 29". It is significant that Jefferson emphasized that the crate is cube-shaped, signaling its similarly shaped contents (fig. 31). This marvel of packing would only have been possible if the base was disassembled and flat-packed alongside the top. The three S-curved legs easily fit, but the telescoping shaft may have been packed into a larger crate.

Jefferson’s designation “paper press” is misleading, suggesting a cupboard or a screw press; this is because he frequently used the word “press” as shorthand for a thing to hold things. Broadly modeled after plate 51 in Hepplewhite’s Guide, which illustrates designs for reading desks with a similar telescoping feature and a support structure for a lectern, Jefferson’s redesign included five lecterns. This was a unique interpretation as well as an overlooked invention. Multiple lecterns on a revolving base offered Jefferson easy access to numerous documents without shuffling papers or leaving his seat. The telescoping feature meant that he could work both standing and seated, and when lowered, the stand could function as a writing table. Typically this object sat next to the revolving chair when Jefferson was writing. Grandson Thomas Jefferson Randolph saved the reading stand for himself. In 1887 the reporter Frank Stockton stayed with the Randolph family, where he was invited to use the stand. He was delighted with the object’s functionality, “a small table with four curious wings, which can be spread out at the sides to hold books of reference, that was used by Mr. Jefferson as a writing-stand, and on which yet remain some blots of ink which declared their independence of his pen.” The family kept the reading stand, sans its base, until the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation acquired it in 1938.[35]

Crates three and four contained a two-part tambour writing table and bookcase, a monumental and costly object that has yet to be located. Jefferson maddeningly titled the contents as “N°. 3. Press. under part. 57. I. 26. I. 27. I. 23 3/4 cub. feet” and “N°. 4. upper part. 58. I. 56. I. 18. I. 34 1/2 cub. feet.” As with the reading stand, Jefferson used “press” in an imprecise way. Without a clear title, the crate dimensions became key to identifying these objects. Starting with crate four, the “upper part” verbiage indicated a two-part object, with the top portion being somewhat less than W. 58", H. 56", D. 18". The height, and particularly the narrow depth, of the “press” suggested a bookcase intended to sit on top of a desk.

Having identified the “upper” bookcase, the “under part” in crate three was almost certainly a desk. At W. 57", H. 26", D. 27", the width and depth suggested a base wide enough to hold the bookcase. But what kind of desk is a mere two feet tall? This lack of height can only be accounted for if, like the reading stand and writing table, it was flat-packed. Flat-packing the base of a monumental piece of case furniture sounds unlikely unless it was designed and constructed in the French manner, with hardware that enabled the legs to be unscrewed and removed. Jefferson was familiar with this innovation, having seen it in Paris, where the specialized desks and tables (fig. 32) pioneered by the master cabinetmakers Abraham and David Roentgen were on show. Jefferson saw Roentgen’s work, as well as examples by other talented cabinetmakers, at Versailles, in the homes of friends, and in the luxury shops on the rue St. Honoré and at the Palais-Royale. Jefferson could not step into a wareroom in New York and buy a secretary bookcase with detachable legs; such a feature was rare, if not unheard of, in American cabinet shops. He would have had to specially request that the desk portion be constructed in this manner, and then the shop would have had to adapt their existing design and either source the necessary hardware or devise a screw-and-nut system to fit into the legs.[36]

Dimensions for the desk portion, which are wide and deep but not tall, indicate that Jefferson acquired a bureau à cylindre or a rolltop desk on legs. In the 1770s the Roentgens perfected desks like this, adding self-acting drawers, multi-functionality, and removable parts for ease of shipping (fig. 33). Parisian cabinetmakers and sales rooms marketed rolltop desks as ideal for a gentleman’s study. These desks were status objects, featuring wooden cylinder or tambour lids, equally both demanding and costly to execute. The innovative fauteuil de cabinet or revolving office chair was designed to make writing while seated comfortable, but also to serve as a handsome and exclusive accessory. The fifth Duke of Devonshire’s revolving office chair and bureau desk (fig. 34) are at Chatsworth House in England, courtly objects to delight the owner and impress the viewer. This set is akin to what Jefferson saw but could not afford to acquire when in Europe. It is this pairing that he sought to re-create as part of his Burling commission.[37]

It speaks to the cosmopolitan milieu in New York that Thomas Burling was already familiar with this power grouping, both the French aesthetics and the mechanics of it. Prior to the Jefferson commission, he made a cylinder rolltop desk (fig. 35) and office or “uncommon chair” for Washington, the exact grouping favored by European aristocrats and kings. Jefferson would have seen Burling’s freshman effort, likely taking mental or actual notes on what he would improve. The desk is modeled after the high-style version of a rolltop, which has a superstructure of drawers added to the top. Burling had the correct elements in place for his costly tour de force, but the result is poorly proportioned and overly massive. It is interesting to note that the original legs were lost, suggesting that they were made to be detached in the French manner. For design sources, Burling may have seen an imported French example, perhaps at the home of the comte de Moustier, French minister to the United States, who brought furniture with him on his mission to New York.[38]

Jefferson’s secretary and bookcase probably hewed closely to Hepplewhite’s interpretation of this form, particularly the “tambour writing table and bookcase” illustrated on plate 69 (fig. 36) in the Guide. Gentlemen in Britain and America favored this two-part design, which provided ample storage for documents, books, writing implements, and valuables. The French seldom paired a bookcase with a rolltop desk, instead reserving the top of the desk for a clock or lighting. Hepplewhite’s Guide does not provide instructions for detachable legs, but the sketch for the tambour writing table shows a bead molding at the base of the case. This treatment appears on French examples, creating a finished effect where the leg meets the case. Having previously determined the size and appearance of the original sideboard, the designs for tambour writing tables, which have a similar aesthetic, served as models for a modern reproduction. Burling charged £21 for a standard “Mahogany Desk & book case,” but Jefferson’s updated version certainly cost more, taking up the largest portion of the £143.12 total bill.[39]

Why would Jefferson order a new writing table and a secretary and bookcase from Burling when he was already better outfitted in that regard than most? In addition to his French writing furniture and the London writing tables, back at Monticello there was a monumental library bookcase and a mahogany standing desk (fig. 37). Scholar Dena Goodman has shown that the bureau form that Jefferson and Washington chose “was the mark of a man who had moved up in the world.” The design evolved from a flat-surfaced table to “a more complicated piece of furniture that included storage of business papers.” This was a classic choice for men engaged in public affairs or business, ones who valued the added storage, locking features, and impressive profile. Some examples also feature pull-out writing surfaces where a secretary could work alongside. A luxury of the highest order, Jefferson indulged himself when he purchased this object, making a statement about his importance in the world, while gaining a controlled locus to write and store his personal letters—and perhaps, the sentimental tokens of a highly private man.[40]

Fortunately, the clues on the packing list and in the will of a Jefferson descendant confirm that such an object existed, and with the evidence gleaned from other New York case pieces, there was enough information to commission a reproduction tambour writing table and bookcase (fig. 38). Conversations with furniture specialists confirmed that flat-packing was used, made possible because of detachable legs and crate dimensions that were overly wide to provide space for padding and the separated components. The reproduction is H. 91 15/16", W. 44 1/4", D. 24", which was in part determined by wall space in the library where the original was later installed. Unlike the revolving chair, the tambour writing table and bookcase have never become closely associated with Jefferson in the minds of the public, probably because the latter lacked the ingenious features that his boosters chose to emphasize. After Jefferson’s death, the piece was moved to his grandson’s home, Edgehill; the last time it is mentioned is in a family will proved in Albemarle County, Virginia, in 1902.[41]

A pair of unique tables (fig. 39) is all that remains of a group of seven commissioned by Jefferson. The packing list states dining tables, plural, “N°. 6. Dining tables 58. I. 33. I. 26. I 31. cub. Feet.” The tables have elliptical ends and are pointedly plain, with straight tapered legs and oversized leaves. When closed a single table measures H. 29", W. 52", D. 4 3/8". The set features exceedingly narrow tops measuring four inches wide, ensuring that all seven tables could fit into crate six despite its being a mere twenty-six inches deep. With this new information, the set of seven dining tables has been re-attributed to Thomas Burling and his workshop.[42]

Jefferson was enamored with useful objects and new ideas. Nicholas Trist, Jefferson’s grandson-in-law, described him as an “economist of space” who sought to utilize space and time efficiently, making that economical approach “his Method of Life.” Trist was both mythmaking and being truthful about his patriarch’s limitless interest in improved systems and objects. To that end, Jefferson collected useful information wherever he encountered it, creating sketches and details for later reference. The ensuing projects were rarely his invention, but rather thoughtful adaptations. One example of his method is found in a memorandum from his 1788 trip to Holland, where he sketched a space-saving table (fig. 40) that, when closed, barely measured four inches deep. This note later served as the inspiration for these dining tables. It is possible that Jefferson shared this sketch with Burling when discussing the order.[43]

The construction of the end sections is unique among American tables. Each section has two stationary legs and three fly legs; the stationary ones are attached at the ends of the primary structural rail, one fly leg extends ninety degrees to support the elliptical drop leaf, and two fly legs extend to support the rectangular leaf. When the leaves of each end are folded down, each section is approximately four inches deep. Mortises cut into the edge of the rectangular leaf of one section, and tenons on the other, indicate the ends were joined to other table sections, and the dimensions of the crate indicate that they were similar forms, albeit with all rectangular leaves.[44]

Jefferson eventually used the design, proportions, and scale of the dining tables as a template for a set of Pembroke tables (fig. 28) that Monticello joiners James Dinsmore and John Hemmings made for Poplar Forest. These tables have a plain, almost severe aesthetic, and unusually, they lack drawers. This feature would have interfered with their functionality as units working with the dining tables. These later Pembroke tables were added to the mix of dining table options first established in there 1790, to be used in conjunction with the original set of seven dining tables. Furniture conservator Robert Self ’s essay on these Pembroke tables notes that the New York dining tables were still at Monticello in 1815, appearing on the tax declaration as “5. Single & 2 double leaved dining tables.” The missing single leaves were “supported by bases having two stationary legs and one swing leg.” The combination of singleand double-leaved tables offered options when setting up for dining. The attention to detail that Jefferson lavished on these tables shows his interest in geometry and his delight in applying mathematics to everyday objects, turning table placement into a mathematical exercise.[45]

Once set up, it becomes apparent how severely plain the tables are—a forest of legs with only figured mahogany for aesthetic appeal. The form may have come from Holland, but the aesthetic is French. According to scholar Kathryn Norberg, “French dining rooms were traditionally rather ad hoc affairs, located (as at Versailles) in an anteroom and bare of furniture save for a folding table.” And unlike English gentlemen who lingered at the table after dinner, making it a suitable object for show, the French, both men and women, retired to the comfort of the salon. When dining at Monticello, the tablecloth was removed after the second course, revealing the varied rectangles and elliptical ends for the guests to ponder.[46]

Of such importance and expense, Jefferson’s new revolving chair (fig. 41) was crated, not shipped in mats like other seating on the New York packing list: “N°. 7. Chair 56. I. 29. I. 29. I. 26 1/4 cub. Feet.” Derived from a French fauteuil de cabinet or office chair, it was a form used exclusively by gentlemen when writing. Revolving furniture, be it seating or tables, appears mundane to modern eyes, but patrons in the eighteenth century would have delighted in this practical innovation of activating the object instead of the sitter. New forms like the office chair are what scholar Mimi Hellman has identified as examples of “a vast battery of small props.” Thus, it was not a given that consumers, including Jefferson, were sophisticated enough to know how to perform or interact with the latest revolving and gliding furniture. Hellman argues that “elite leisure was a social spectacle based on continuous engagement with complicated things.” It was easy to put a foot wrong, but Jefferson enthusiastically embraced this new form of seating, along with a host of innovative furniture, much of which he tasked Burling to create.[47]

Jefferson’s revolving chair follows the accepted formula by retaining the overall form with its circular base and rotating seat and features leather upholstery, armrests that are set back from the front rail, tapered mahogany legs, and spade feet with casters. The circular seat offers the comfortable leg support needed for prolonged sitting, and the set-back of the arm supports ensures that the chair can be pulled up close to the writing surface. Unfortunately, the handholds were later drilled to receive brass candle arms, an implausible addition that would make it difficult to get up from the chair. Conservator Carey Howlett recently reupholstered the chair in red Morocco leather, replicating the French box edge on the back and the box seat. The most noticeable and surprising change that Jefferson asked for was to have the back substantially taller than the French prototype (fig. 34). With its impressive stature and crimson upholstery, Jefferson’s office chair was akin to a personal chair of state used by royalty or the elected officeholders at Federal Hall in New York. Burling probably had made the impressive and commodious speaker’s chair (fig. 42) the year before. If asked why his chair appeared so stately, Jefferson might have demurred, noting that the added height was intended to prevent drafts.[48]

Jefferson favored this chair above all others, celebrating its convenience and, perhaps, its impressive appearance. When writing, he could turn in space and shift position by activating the casters or the rotating mechanism, offering a labor-saving way to work while seated. In the context of his group of writing furniture (fig. 43), the revolving chair was the nexus or brains of the operation, from which the auxiliary revolving tables and stands, along with the benches, took their cue. Today we take such movement in unison with furniture as a norm, but in the late eighteenth century this partnering of revolving objects working in tandem was novel. It may be fair to say that Jefferson pushed this concept of efficiency through moving objects further than his contemporaries, perfecting his writing practice to wholly and elegantly utilize the varied positions and functions available to him. Here credit must also be given to Burling and his shop for creating this whirling parade of mahogany and walnut that is now so closely associated with Jefferson and his personae as writer and inventor. Jefferson never abandoned his revolving chair for something newer. The original apparently stayed at Monticello, but he used a version of it in Philadelphia when he was vice president. The public was aware of Jefferson’s curious chair because he extolled its usefulness to others; but instead of affirmation, he was ridiculed for his frivolous “whirligig chair” by political adversary Alexander Hamilton.[49]

Continuing with his interest in revolving chairs, Jefferson had a carpenter at Monticello retrofit a revolving seat onto a tall comb-back Windsor armchair from Philadelphia. This chair was further updated with new bamboo-shaped legs and stretchers and a writing-arm extension. This work may have been completed about the time he acquired a Windsor bench, also from Philadelphia, in 1798. These two Windsors became part of Jefferson’s writing suite, with the new bench available to be pulled up against the rebuilt Windsor chair as well as the Burling revolving chair. Ultimately, Jefferson settled on the latter combination, foregoing the use of his New York metamorphic sofa as a bench and sending the revolving Windsor chair out of the private suite, perhaps to a transitional space like a porch or pavilion at Monticello. Thus, the writing arrangement most closely identified with Jefferson is the Burling revolving chair, the Windsor bench, and the retrofitted table with the revolving top and possible base from New York. The revolving armchair and its related components, and the polygraph or copying machine, are a highlight for visitors to Monticello (fig. 43), who expect to see it upon entering the cabinet, as if the retired statesman has just left the room.[50]

The writing table in the oddly shaped crate eight is now recognized as the octagonal table illustrated in figure 44. Jefferson listed it as “N°. 8. Writing table - - 39 I. 33. I. 7.I 3 3/4 cub. Feet.” A highly valued object because of its associations with the family patriarch, it was sent to Jefferson’s granddaughter in Boston, who asked to have it as a keepsake. Writing tables like this could be used by more than one writer or student at a time, which is one way it differed from the tambour writing table and bookcase. Joseph Coolidge, Jefferson’s grandson-in-law, fondly recalled “the octagon table which I used to read, and where His papers were kept.”[51]