Thomas Burling, revolving chair, New York, 1790. Mahogany with white oak and chestnut; iron, brass, and leather (replaced). H. 48", W. 25 7/8", D. 31". (Courtesy, Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello.) This image shows the chair as it appeared before conservation in 2021.

Thomas Burling, “uncommon chair,” New York, 1790. Mahogany with white oak; iron, brass, bone, and leather. H. 39 3/8", W. 27", D. 32". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association.)

David Roentgen, fauteuil de bureau, Neuwied, Germany, 1783–1784. Mahogany and walnut; brass, iron, horn, and leather (replaced). H. 36", W. 31 1/4", D. 26 3/4". (Courtesy, Chatsworth House Trust.)

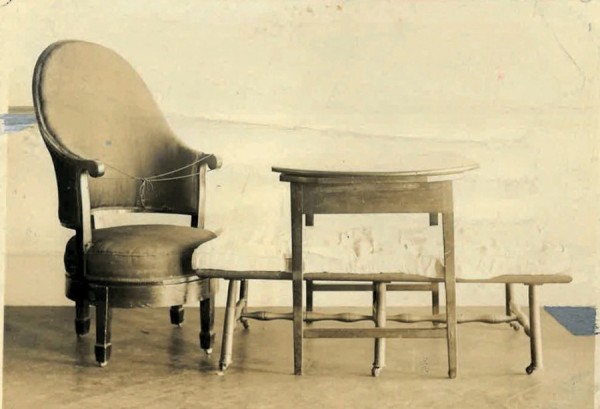

Thomas Jefferson’s writing group. (Courtesy, Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello.) This pre-1924 photograph contains the earliest known image of Jefferson’s revolving chair.

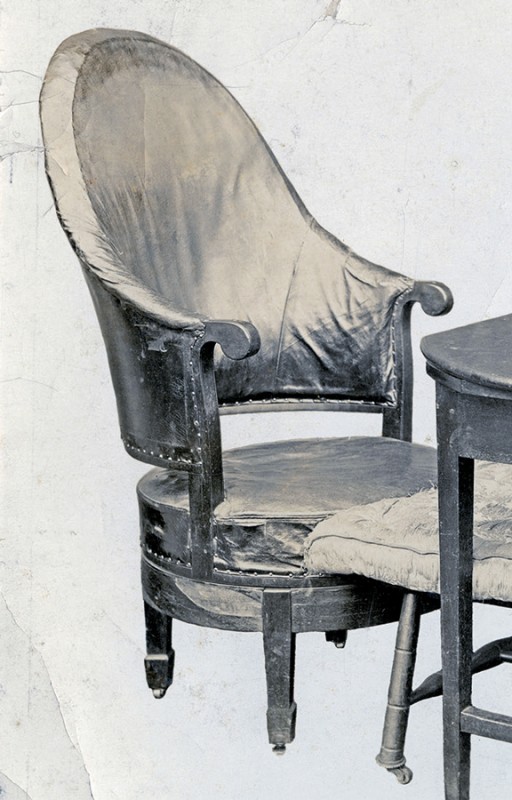

Revolving chair illustrated in fig. 1 after removal of modern upholstery materials. (This and all 2020–2021 photos of the Jefferson and Washington chairs, as well as conservation photos of the Jefferson chair, by Talitha Daddona or F. Carey Howlett of F. Carey Howlett and Associates unless otherwise specified.)

Underside of the base of Jefferson’s revolving chair showing cross-stretchers with central shaft of the swivel mechanism joined to the laminated circular seat rail. Later pine blocks reinforce the leg joints.

Upper surface of the base of Jefferson’s revolving chair showing the four inset brass rollers and the central plate forge-welded to the collet for the rotating shaft.

Detail of the frame of Jefferson’s revolving chair.

Detail showing the sheet steel plate secured with fifty-five screws to the bottom of the seat of Jefferson’s revolving chair.

Detail showing the square faceted nut used to secure the upper section of Jefferson’s revolving chair to its base.

Detail showing the bottom of the chair seat with metal plate removed, revealing the dovetails joining the cross-stretchers to the circular seat frame.

Thomas Jefferson’s writing group, in a photo taken after 1925, showing the chair with plain textile upholstery. (Courtesy, Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello.)

Detail showing glue-bound fibers of probable original leather above the veneer cross banding on the seat rail of Jefferson’s revolving chair.

Detail showing the original brass nail pattern of Jefferson’s revolving chair, with square cast brass shanks remaining in some locations.

Detail of Jefferson’s revolving chair showing the oak nailing blocks that document the original seat height as well as the slope of the crown. The rear seat block is a half-inch lower than the side blocks, indicating a slight backward tilt to the original seat.

Detail showing the differences in rasp marks and wood coloration which indicate reshaping of the crest rail of Jefferson’s revolving chair. This alteration was probably associated with the later slimming of the back loft profile.

Close-up of the revolving chair from Jefferson’s writing group illustrated in fig. 4.

Armchair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1790. Ash; paint, gesso, bole, gold leaf. H. 36", W. 20 1/2", D. 19". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.) The chair has its original foundation upholstery.

Detail showing the beveled boxed edge of Washington’s “uncommon chair.”

Detail showing the current seamed construction of the inner back of Washington’s “uncommon chair.”

Detail showing the current profile of the one-piece leather seat of Washington’s “uncommon chair.”

Photograph, ca. 1950s, of Washington’s “uncommon chair” showing leather and apparent twentieth-century cotton batting partially removed from the back. The crisp beveled boxed edge of the original foundation upholstery is visible.

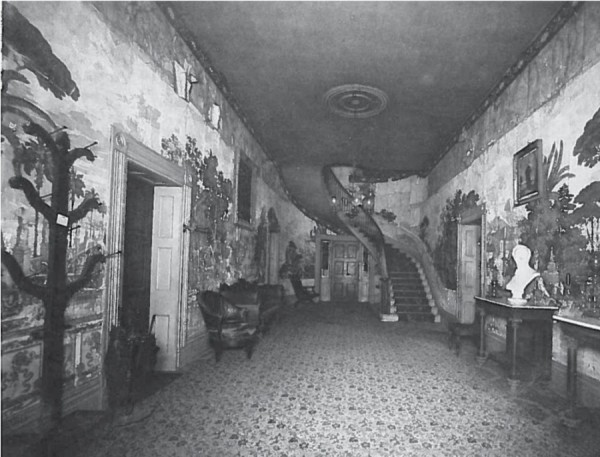

Central hall, The Hermitage, Nashville, Tennessee, 1892. (Courtesy, Archives of the Andrew Jackson Foundation.)

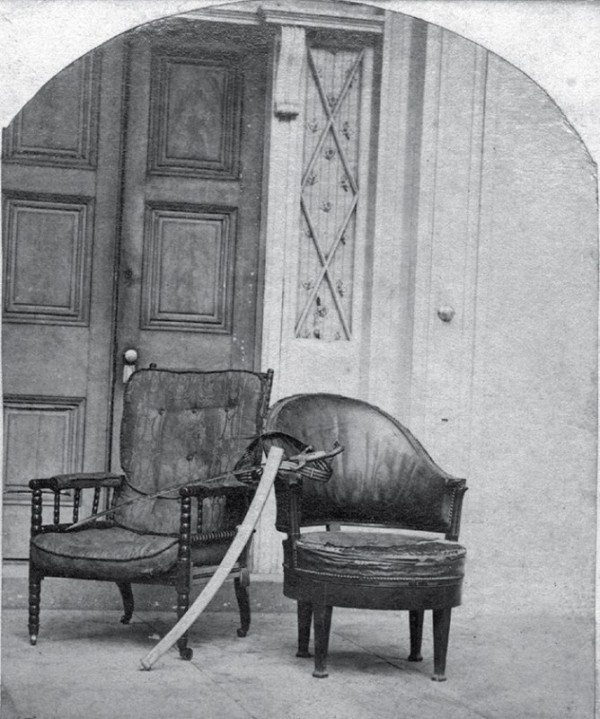

C. C. Giers, stereoscope image of Washington’s “uncommon chair,” The Hermitage, Nashville, Tennessee, 1867–1880. (Courtesy, Archives of the Andrew Jackson Foundation, po404a.)

C. C. Giers, stereoscope image of Washington’s “uncommon chair,” The Hermitage, Nashville, Tennessee, probably 1884. (Courtesy, Archives of the Andrew Jackson Foundation, 247-6.) The slipcover is visible in this image.

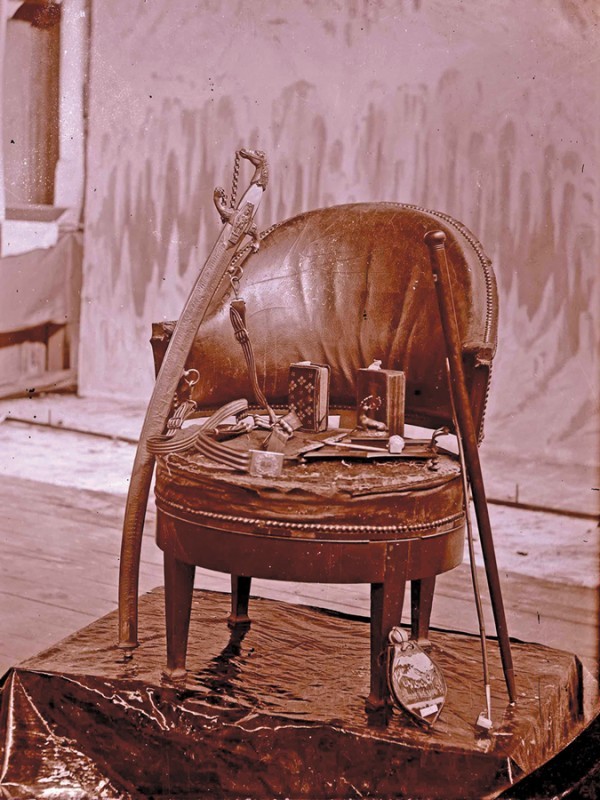

Stereoscope image of Washington’s “uncommon chair” with other artifacts, The Hermitage, Nashville, Tennessee, 1880–1885. (Courtesy, Tennessee State Library and Archives, #2081.)

Detail of the stereoscopic image illustrated in fig. 26 showing the self-welted seam on the seat of Washington’s “uncommon chair.”

Detail of an original self-welted seam on a backstool, probably England, ca. 1765. (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, acc. no. 1980-186.)

Detail of the stereoscopic image illustrated in fig. 26 showing a likely leather strip beneath a row of decorative brass nails on the inner chair back of Washington’s “uncommon chair.”

Mock-up of brass nails above the leather strip on Jefferson’s revolving chair.

Detail of the seat of Jefferson’s revolving chair.

Detail of the seat of Washington’s “uncommon chair.”

Detail of the inner back profile of Jefferson’s revolving chair.

Detail of the beveled boxed edge on the inner back of Washington’s “uncommon chair.”

Stacked and friction-fit polyethylene foam simulating the likely original loft of the back of Jefferson’s revolving chair.

Sculpted foam foundation for the conservation upholstery of Jefferson’s revolving chair.

Temporary steam-bent oak nailers for pre-stretching leather on the inner back of Jefferson’s revolving chair.

Dampened and pre-stretched leather drying in place on Jefferson’s revolving chair.

Hook-and-loop fasteners placed on the beveled boxed edge of Jefferson’s revolving chair.

Mock-up of the self-welted seam for Jefferson’s revolving chair.

Brass upholstery nails were cut, riveted, and glued to leather strips before adhering them to Jefferson’s revolving chair.

Jefferson’s revolving chair after treatment, with conservation upholstery based on the physical, photographic, and documentary evidence discovered during research.

Side view of Jefferson’s revolving chair after treatment. Note that the brass candle arms visible in figure 1 are not longer present. These were probably placed in old holes in the chair in the 1960s. There is reason to believe the holes originally served another purpose perhaps to support a tray late in Jefferson’s life.

Rear view of Jefferson’s revolving chair after treatment.

The chair is . . . untouched by the hand of the restorer, and it . . . , with the exception of the leather covering, is well preserved. It was taken out of doors to be photographed, in order to secure a better light, so that every detail might stand out clearly.

—Letitia H. Alexander, Louisville, Kentucky, 1905, in reference to George Washington’s “uncommon chair,” then at Andrew Jackson’s home, The Hermitage.

THOMAS JEFFERSON’S upholstered revolving chair is probably the best known of his furnishings at Monticello. A nearly unique example of American furniture with a circular swiveling seat and a high arched back, family tradition holds that Jefferson regularly used it in his study at Monticello from the time he purchased it from New York City cabinetmaker Thomas Burling in 1790 until the end of his life. At some point following his post-presidential return to Monticello, Jefferson began using the chair in tandem with a bamboo-turned upholstered bench and a simply constructed revolving-top table, much as it is currently displayed in the study at Monticello. This incongruous juxtaposition provided him with a comfortable if not fashionable arrangement to conduct his daily reading, writing, and record-keeping, enabling him, in spite of chronic back problems, to work in a partially recumbent position until very late in his life.

In 2020 the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation contracted with F. Carey Howlett and Associates to conserve the chair (fig. 1). Research into the form, details, and materials of the long-lost original upholstery became a major component of the project, culminating in the application of new conservation upholstery based upon the findings.

Conservators charged with reupholstering period furniture rarely find sufficient evidence for an indisputably accurate reproduction of the original appearance of a chair or sofa. Physical examination may provide useful information for interpreting loft heights, indicate the original presence of nail trim, and even reveal tiny remnants of early textiles or leather. Such evidence is generally fragmentary, and additional research rarely turns up sufficient documents, drawings, or archival photographs to provide a complete picture. Consequently, reupholstery treatments are often somewhat speculative, relying on examples found in period paintings and drawing books and on the conservator’s or curator’s knowledge of period styles, materials, and practices to fill in missing information.

The need for conjecture often decreases with furniture associated with historic figures, where documents and early images are more likely to exist. Old photos and a few documents in the files at Monticello certainly aided the study of Jefferson’s revolving chair, but research was greatly enhanced by the fact that this object has an important analogue that belonged to an equally significant American: George Washington’s “uncommon chair” at Mount Vernon (fig. 2). A synthesis of physical and documentary evidence from both chairs, including early photographs of Washington’s chair previously unrecorded at neither Mount Vernon nor Monticello, revealed subtle details of the original trim and the loft profiles common to both chairs, resulting in a high level of confidence that the new upholstery treatment on Jefferson’s revolving chair presents an accurate interpretation of its original appearance.

The Jefferson and Washington chairs are of very similar form and nearly identical structure. Both men commissioned their chairs from Burling during the brief tenure of the newly formed United States government in New York City. Burling ran a successful cabinetmaking business in the city, and he was already known to officials in the new government by 1785, when he provided thirty-six upholstered chairs for the Congress of the Confederation when it first met in the old City Hall, later to become Federal Hall. When Washington came to New York in April 1789 to be inaugurated as the first president of the United States, the government authorized funds to purchase more than 120 items of furniture from Burling to furnish the president’s home at 1 Cherry Street. Washington was apparently impressed with Burling’s work, since he later commissioned Burling to make several pieces of furniture for use at Mount Vernon, paying the cabinetmaker seven pounds on April 7, 1790, for his “uncommon chair.” Jefferson had arrived in New York only few weeks earlier, on March 21, to be sworn in as secretary of state. Records show Jefferson paid Burling for several unidentified items in July and August of the same year. A portion of one of these payments apparently was for his revolving chair.[1]

The timeline of payments indicates that Washington’s chair predated Jefferson’s by several months, with its construction probably occurring before Jefferson arrived in New York. This refutes earlier scholars’ attribution of the French-inspired design of both chairs to Jefferson, a conclusion based on both Jefferson’s service as minister plenipotentiary to France from 1784 to 1789 and his predilection for drawing, mechanical devices, and invention. Although made by an American cabinetmaker with no obvious Continental connections, there is a distinct Continental design prototype for the Jefferson and Washington chairs: both are clearly based on a known French Louis XVI neoclassical chair of identical form and mechanical function, the fauteuil de bureau (upholstered gondola chair with a revolving seat). While never common, such chairs with arched concave backs and circular revolving seats were generally upholstered in leather and served as office chairs for well-to-do French businessmen and aristocrats. Examples are known to have been made by such noted Parisian artisans as Georges Jacob (1739–1814) and German-born David Roentgen (1743–1807) (fig. 3).[2]

It is very likely that Jefferson became familiar with the form while living in France, but the notion that he designed the chairs ignores Washington’s own interest in items of French style and manufacture, which dates nearly ten years earlier to the final years of the Revolutionary War. Like other Americans, Washington hoped to break away from economic as well as political reliance on Great Britain after the Revolution. He saw France, the colonists’ chief ally in the war, as a model for the new republic in social, intellectual, and aesthetic domains. While he never traveled to France, Washington’s post-war correspondence with French officers he had met during the war and with Americans serving in France throughout the 1780s demonstrate his keen interest in French culture—and his desire to obtain furnishings in the prevailing French neoclassical style. This interest continued even after his presidential inauguration in New York. On November 21, 1789, Washington purchased from Burling a desk based on a French bureau à cylindre, and a few months later he bought several pieces of French furniture from the Count de Moustier, who departed New York in 1790 after serving for a year as the French minister to the United States. Whoever was primarily responsible for the designs of Washington’s and Jefferson’s chairs, Burling’s work closely followed the form and function of their prototype, the fauteuil de bureau.[3]

Scholars often discuss the influence of French neoclassical design in relation to domestic spaces intended for sociability and entertainment, with an emphasis on furnishings suitable for dining rooms and parlors. The revolving chairs made by Burling for Jefferson and Washington served a different function: as office chairs for use in a private setting. As such, both chairs are relatively plain in appearance and upholstered in leather, their curves embellished only by rows of decorative brass nails. Exposed wood of both solid mahogany and plain-sawn mahogany veneer is unadorned by carving or inlay with the exception of a single thin light wood band (probably maple) delineating the lower edge of the Jefferson seat. Both chairs were designed with comfort, utility, and durability as the guiding factors, and evidence indicates the chairs were regularly used in the studies of both men. In bequeathing his chair and the secretary desk apparently used with it to his “companion in arms and old and intimate friend, Dr. Craik,” Washington wrote, “I give my beaureau [sic] (or as cabinet makers call it tambour secretary) and the circular chair, an appendage of my study.” Washington obviously viewed his chair as an indispensable component of his personal office. There is no written reference by Jefferson regarding his revolving chair, but recollections of his consistent use of that object along with his bamboo-turned bench and plain writing table demonstrate that comfort and function were more important than style or ostentation in the furniture he used for daily correspondence and record-keeping at Monticello (fig. 4).[4]

This article details the process used to determine as much as possible about the long-missing original upholstery on Jefferson’s chair, concurrently examining the frame of the chair for physical evidence of the earliest treatment while also studying the photographic and documentary record for clues to the history of upholstery campaigns. The supplemental examination of Washington’s “uncommon chair” did not include the removal of upholstery to examine its frame, but a careful study was made of its existing upholstery in conjunction with archival evidence. Correlating the information from both chairs served as a means both to confirm the findings from Jefferson’s chair and to obtain information necessary to provide a full and nuanced understanding of its likely original appearance. The results of the study appear below, and the article concludes with a brief discussion of the minimally intrusive techniques used to apply new upholstery and re-create the earliest appearance of Jefferson’s revolving chair.

Jefferson’s Revolving Chair

The chair Thomas Burling made for Jefferson is tall, with a circular seat and curved gondola back, both being outlined with veneer banding. The chair proper swivels above a circular base, veneered in plain-sawn mahogany, that stands on four tapered mahogany legs with spade feet and small original brass casters. The sweep of the chair back, detailed with the bands of cross-grain mahogany veneer, is continuous with the arm rests. The latter end in simple mahogany volutes, with the terminals projecting above vertical mahogany arm supports that are simply beaded on both edges of their faces. Additional mahogany veneer bands outline the front and rear edges of the stay rail, divide the outer chair back vertically into three sections, and run along the bottom edge of the circular seat.

Before conservation, the chair was upholstered in smooth red leather trimmed with closely spaced three-eighths-inch-diameter brass upholstery nails. This upholstery probably dated from the 1960s or 1970s, and decisions regarding the details of this treatment are not on record. The leather of the concave inner back was applied in a single piece and its loft was relatively shallow, tapering smoothly and thinly to the veneered edge banding. The seat leather was also applied in a single piece, with the sides slightly bulging and with somewhat rounded edges curving into the slightly crowned profile of the seat top, somewhat reminiscent of a 1960s pillbox hat. Although not overstuffed—the typical state of eighteenth-century period furniture reupholstered in the mid-twentieth century—the upholstery had a simple, minimalist appearance that suggested only nominal attention had been paid to historic evidence.

The modern upholstery was removed to reveal the frame (fig. 5), with care taken to identify and preserve any evidence surviving from the earliest treatment. Removing the upholstery enabled not only the search for earlier upholstery evidence but also the study of the chair’s mechanism for rotation. Because this feature of the Jefferson and Washington chairs is apparently unique in American furniture of the late eighteenth century, the mechanism is described below along with notes on the frame, followed by a discussion of surviving evidence of the earliest upholstery.

Construction of the Jefferson Chair

The fixed base of the chair (legs, circular rails, X-stretcher, and rollers) consists of solid mahogany legs supporting a circular frame of mahoganyveneered white oak. The circular frame consists of three one-and-seveneights-inches-thick laminated stacked rings, the upper and lower ones an inch thick and the central one a bit thinner. Each sawn oak ring is composed of four butt-joined quadrants, and rings are stacked with joints offset like brickwork. The laminates are both glued and screwed from the bottom with four large wood screws per quadrant. There is a thin lightcolored hardwood cap on the seat rail that serves both as a decorative edge banding and as protection to the upper edge of the horizontally oriented veneer below (fig. 6).

The four slightly tapered mahogany legs have applied molded spadeform cuffs. These legs are bridle-joined to the frame. At the leg joints, the frame is dadoed on its front and rear faces to accept the projections of the legs. There are four yellow pine triangular reinforcing blocks, each screwed and glued into the inner face of each leg and to the end of the X-stretcher. These blocks are later additions to reinforce fractures at the original joints.

Two lengths of quarter-sawn oak just over three and three-quarter inches wide compose the X-stretcher, and both lengths are dadoed at the center to join them in plane. The stretchers are lapped and dovetailed (each with two dovetails) onto the uppermost ring of the circular base frame at the location of each of the four bridle joints. This joinery is mostly obscured at the top by the light wood cap and four inset brass rollers directly above each leg. Removal of the inset rollers reveals portions of the dovetails, showing the construction to be identical to that of the chair seat frame described and illustrated below. The brass rollers appear to be original, as no earlier screw holes are present below them, and they project approximately an eighth of an inch above the surface of the base (fig. 7). According to the files at Mount Vernon, Washington’s “uncommon chair” swivels on bone rollers, which is the only significant difference in the revolving mechanisms between both chairs.

A three-quarter-inch hole in the center of the X-stretcher receives a central pin projecting from the bottom plate of the revolving chair frame. A collet forge-welded to the center of a recessed square plate fits down into the hole, with the plate held in place with four original screws. The slightly tapered collet is approximately two and one-eighth inches long. Its interior diameter, designed to fit the slight taper of the pin, is approximately sevensixteenths of an inch at top and three-eighths of an inch at bottom.

The chair frame consists of a round seat frame intended for over-the-rail upholstery. Three vertical stiles support the curved back of the chair: two at the mid-points of the circular seat perimeter serve as arm supports, while the third at the rear center point supports the tall curved seat back (this stile is hidden by the upholstery above the stay rail). A horizontal U-shaped stay rail at the base of the upholstered back is mortised at its ends into the rear surface of the arm supports and is joined to the central rear stile. Two additional vertical support stiles flank the central stile and run between the stay rail and the curved and arched crest rail. Their rear surfaces are faced with three-quarter-inch strips of mahogany, which divide the convex outer chair back into three sections. The upper edge of the crest rail is outlined with bands of nine-sixteenths-inch-thick cross-grain mahogany veneer facing both front and back. The lower ends of the crest rail sweep forward horizontally to form the arm rests, which terminate in simple solid mahogany volutes (fig. 8).

The secondary wood making up the chair base and chair proper is almost entirely white oak. The only exceptions to this are the curved chestnut members making up the sweep of the arm rests and curved back. These were constructed in several lap-jointed sections to create the curved back and to minimize weakness associated with short grain. Chestnut is a wood often found in American upholstered seat frames because of its relative strength, light weight, and ability to accommodate nailing.

The bottom of the revolving chair has a painted ferrous sheet metal plate secured to its understructure using fifty-five late eighteenth-century screws (fig. 9). Thirty-four are evenly spaced around the perimeter approximately three-sixteenths of an inch from the edge. Seventeen more form a ring approximately one and five-eighth inches in from the outer ring, with the space between the inner and outer rings serving as the circular track for the chair base rollers. Four additional screws are placed evenly around a central projecting pin used to secure the chair to its four-legged base. The central pin (forge-welded to a small square plate set into the center members joined to form the sweeping curve of the back of the X-stretchers) is two and a half inches long with a slightly tapered shaft (seven-sixteenths of an inch at its greatest diameter), with a narrower threaded projection at its end to receive an unusual square nut filed with decorative triangular facets (fig. 10).

Removal of the painted sheet steel plate on the bottom of the chair seat revealed the understructure of the seat and confirmed that the metal plate had always been part of the chair (fig. 11). The chair’s round seat frame is constructed much like the separate round four-legged base. The rails are constructed of two stacked oak rings, each ring consisting of four buttjoined quadrants, with the quadrants of one ring offset from those of the other to maintain the strength of the assembly. The rings are glued and secured from the bottom with large wood screws. Oak X-stretchers identical to those in the chair base are each let into the bottom ring of the circular seat frame with two dovetails at each end. Large wood screws are placed through holes drilled in each dovetail into the seat rail above. The bottom ends of double tenons securing the mahogany arm supports and back stile are also visible with the ferrous plate removed.[5]

Upholstery Evidence on Jefferson’s Revolving Chair

Removal of the existing upholstery revealed no evidence of any original foundation or loft materials. All the under-upholstery of Jefferson’s chair had been replaced with twentieth-century materials: burlap, horsehair, jute webbing, muslin, ferrous tacks, and decorative brass nails with ferrous wire nail shanks. Notes in the object files at Monticello indicate the chair was reupholstered in 1924 or 1925, when it is likely that the original materials were removed. A photo believed to date circa 1930 shows the chair with a simple textile covering (fig. 12). The chair was reupholstered again in 1948 by Ernest LoNano, the New York upholsterer and interior designer who provided services to many museums and historic sites, before it became the property of Monticello. It is not clear when the most recent leather upholstery was applied, although the form and materials suggest the 1960s or early 1970s.[6]

Although early materials were long gone, study of the bare chair frame revealed evidence of the original show cover and trim. Leather fibers were found embedded in old hide glue near the bottom edge of the rear seat rail. These traces appear to have survived from the original application of upholstery, as the glue-bound fibers were perforated by the earliest nail holes—no locations were found indicating application above early nail evidence. The fibers consist solely of fragments of corium; unfortunately, no evidence of the tanned or dyed leather grain is present (fig. 13).

Small, evenly spaced square holes, some still retaining broken brass shanks, are present along all of the upholstery edges. Spacing indicates these nails were slightly larger than the most recent nails (seven-sixteenthversus three-eighths-inch diameter). There are no visible circular impressions from the brass nail heads, which supports the hypothesis that they were nailed above leather rather than a textile, since weave imprints are often visible in the wooden surface when nails are applied above relatively thin textile show covers rather than thicker leather. As will be discussed below, the likely original presence of leather in association with the brass nails became more credible in light of the survival of a comparable treatment on Washington’s chair (fig. 14).

Examining the bare frame of the chair provided limited information regarding original loft profiles, no information on any possible piecing of the leather, and no inkling of the presence of any trim details other than the brass nails already discussed. Regarding the loft, there was clear evidence of the original height for the seat. Original nailing blocks secured at the base of the stiles on the upper face of the circular seat rails provided the proper height of the seat upholstery and also gave insight into an apparent shallow crown for the original seat upholstery, since the upper surfaces of these blocks sloped slightly downward toward the outer edges of the seat (fig. 15). Determining the original loft of the curved and arched inner back upholstery was more problematic, with evidence that alterations had occurred. The inner corners of the curved chestnut members of the chair back appeared to have been rounded over with a rasp somewhat finer than that used for most of the shaping, and differences in the oxidative coloration of the finely rasped wood suggested that this work occurred much later than the coarser shaping. The only purpose for rounding over these inner edges would be to provide a smoother, shallower nailing surface for upholstery, suggesting that the slim profile of the most recent back upholstery was inaccurate (fig. 16).

Physical examination of Jefferson’s revolving chair supported the conclusion that the earliest upholstery was leather trimmed with decorative brass nails and provided good information about the height of the seat and its shallow crown, but any further details on the original upholstery had to rely on archival evidence and, as we will see, information derived from the study of Washington’s “uncommon chair”.

Archival Evidence for Jefferson’s Revolving Chair

The records at Monticello include a number of old photographs of the chair both before and after it entered the collection. The photos taken before its accession in 1951 are all undated and, with one exception, were apparently taken after 1924 or 1925 since they show the chair with a textile show cloth, a slim back profile, and a somewhat rounded and relatively plain seat. The photos showing the textile-covered chair correspond to a note in the Monticello files dated September 27, 1947, by Helen Duke, the final Jefferson descendant to own the chair. Duke recalled it “was done over in 1924 or 1925 & the chair was then covered with material to harmonize with the brocaded golden satin on the cushion which was on it when the chair was given to my father. When the old cover was taken off the chair there were bits of dark red leather underneath. I think this was much nearer a dark maroon than the magenta tone of the present hangings [?] & wonder if chair and cushion could be in a darker tone.” Duke’s recollection of “red leather” on the old chair is intriguing, particularly in light of a 1787 reference to “red morocco” leather on the chairs Burling made for the Congress of Confederation at City Hall in New York. Is it possible Jefferson was continuing with an existing fashion for red leather with his revolving chair?[7]

Duke’s description of “bits of dark red leather” beneath an “old cover” makes the earliest known photograph of Jefferson’s revolving chair an item of extreme interest (fig. 17). This photo, taken along with the Windsor bench and the rotating writing table, may date as early as the late nineteenth century. The image was undocumented until 1980, when it was acquired by Monticello from Helen Duke’s son. The photo shows the chair with a relatively loose-fitting cover, essentially a hybrid of a nailed-on show cloth and a slipcover. The cover is crudely nailed along the lower edges of the chair back but encapsulates the entire upper portion like a slipcover, obscuring all the veneer trim outlining the curve of the back. The cover has a leather-like sheen but shows folds and wrinkles typical of a much thinner material, suggesting it was a thin oilcloth or similar material. This photograph obviously predates the “1924 or 1925” reupholstery and may well show the “old cover” mentioned in Helen Duke’s recollection. Assuming the cover in this photo lay above “bits of dark red leather,” her comment may not only provide valuable information about the possible original show material for the chair, but one might infer from this that the original foundation upholstery was also partially or entirely in place at the time this photo was taken. Historically, the application of a cover above worn earlier upholstery would have been a common and cost-effective practice.

In spite of the loosely applied cover in this image of the chair, it is clear that the inner back upholstery projects somewhat from the chair frame, with a crisply defined beveled box edge running parallel to the curve of the back. This is a likely indication that the chestnut frame members had not yet been rounded over. The defined edge of the upholstery break in the chair back is echoed by the sharp-edged break of its seat upholstery. Here, the unpadded sides, square edge, and low loft are telling details. Such profiles are not typical of the commodious fashions of midto late nineteenth-century American designers, who favored rounded, overstuffed, deeply tufted seating furniture. They are far more characteristic of the formal neoclassical taste in upholstery of the late eighteenth century. Indeed, the beveled box edge profile of the curved back and the nearly square-edged seat profile of Jefferson’s chair in this probable late nineteenth-century photograph closely parallel the original upholstery foundation on a circa 1790 Philadelphia chair in the French Louis XVI style in the collection of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation (fig. 18). The forms alone lend credence to the notion that the loosely applied cover shown in this late nineteenth-century photograph conceals the surviving original upholstery foundation.[8]

Washington’s “Uncommon Chair”

Because of incomplete information regarding the original appearance of Jefferson’s revolving chair, a study of its closest analogue, Washington’s “uncommon chair” at Mount Vernon, was of paramount importance (see fig. 2). The chairs have the same form, both swivel using nearly identical mechanisms, and both were acquired from Thomas Burling in 1790. The proportions of the two chairs are different—Washington’s chair is lower and has a somewhat wider seat—but their construction is very similar; it is fair to assume they were originally upholstered in a similar manner. A oneday visit to Mount Vernon provided the opportunity for a close examination of the upholstery, which proved helpful even though inspection was necessarily limited to the surfaces and trim, with no removal of upholstery. Even more useful was the examination of documents and photographs in the files at Mount Vernon, which ultimately led to the most important discovery informing the project to reupholster Jefferson’s chair.[9]

Physical Evidence for the Upholstery of Washington’s “Uncommon Chair”

The leather cover of Washington’s chair, very dark and in some areas apparently embrittled, remains edged by early cast decorative brass nails. Much of this leather appears to be old and probably original, but evidence exists of some alterations. Time did not permit fully discerning original material from replacement elements during visual examination, but the study of archival information described in the subsequent section provided a fuller picture of changes to the upholstery. Visual examination produced the following useful information:

Archival Evidence for Washington’s “Uncommon Chair”

The object files at Mount Vernon contain a wealth of information regarding Washington’s chair, but only a few documents speak to the physical condition of that piece and to changes that have occurred to it over the years. Fortunately, these documents answered a number of questions raised during the visual examination, ultimately resulting in the discovery of subtle details about the chair’s original loft and trim that could be incorporated into the reupholstery of Jefferson’s chair.

First, a remarkably comprehensive report of repairs to Washington’s chair prepared in 1954 by Frank E. Morse, an architectural and collections specialist at Mount Vernon, makes the following reference to the original leather of the chair back: “The back of the chair, where the paint had worn off, in poor light looked as if it had been red. Under a strong light however it proved to have been a natural brown from vegetable tanning, either sumac or oak. The color matches perfectly a piece of old vegetable tanned leather used for comparison.” Elsewhere the report states, “the original color was tan or brown. The leather surface originally was the natural grain (i.e. not grained).” Morse reported that the leather appeared to be cowhide. While his conclusion differs somewhat from Helen Duke’s recollection of red leather scraps on Jefferson’s chair and the 1787 reference to “red morocco” (goatskin) on Burling’s Congress of Confederation chairs, it is interesting that his first impression of the Washington leather was that it had been red.[11]

A single page in the Mount Vernon files shows small copies of old photos of the partially disassembled Washington chair that are probably associated with Morse’s repairs. Two of the images show the revolving mechanism, confirming it is nearly identical to that of the Jefferson chair. Another image shows the leather pulled away from the top of the inner back. It is clear in this photo that the leather of the inner back was in three sections much as it is today, but the image also shows what appears to be a partially pulled-down layer of cotton batting between the leather and the original foundation upholstery (fig. 22). The beveled boxed edge of the exposed and apparently original foundation upholstery appears to be as crisp as the edge visible in the earliest photo of Jefferson’s chair. Consequently, this 1950s photo shows that the slightly rounder edge currently seen on the Washington chair may have been softened by the incorporation of batting at some point in the twentieth century. It also indicates that the leather of the inner back had to have been completely removed to accomplish this.

Before its return to Mount Vernon in the early twentieth century, Washington’s “uncommon chair” was among the furnishings at The Hermitage, Andrew Jackson’s home near Nashville, Tennessee. In 1833 Jackson was given the piece by a descendant of Dr. James Craik, to whom Washington had bequeathed the chair. The files at Mount Vernon include a single photograph dating from 1892 of Washington’s chair in the central hall at The Hermitage (fig. 23). In this photo, the chair is a small and somewhat out-of-focus object, but the image seems to show the chair with its original leather upholstery, including a very tattered seat unlike the one currently on that object. A request for photographs from the files at The Hermitage yielded three clear stereoscope photos of the chair believed to date between 1867 and 1905 (figs. 24–26). All show the chair in the condition best described by Letitia Alexander of Louisville, Kentucky, a writer who in 1905 chronicled the impending return of the chair to Mount Vernon: “The chair is . . . untouched by the hand of the restorer, and it . . . , with the exception of the leather covering, is well preserved. It was taken out of doors to be photographed, in order to secure a better light, so that every detail might stand out clearly.”[12]

Nearly all the questions arising from the visual examination of the chair were answered by the Hermitage photos. The extreme clarity of early, professional black and white photography is a boon to researchers, particularly if it survives as glass negatives or high-quality prints. Such was the case with one of the images, a photo taken of the chair at The Hermitage between 1880 and 1885, probably by noted Nashville photographer O. C. Giers (see fig. 26). The glass negative is in the collection of the Tennessee State Library and Archives, and a high resolution digital scan, when enlarged, shows far more detail than is noticeable when the image is examined at its actual 5" x 7" size.

Most noticeable is the form and detail of the leather seat. It is obviously composed of a circular top panel stitched to flat vertical side panels rather than being a single large piece of leather. The side profiles are flat, and the top, though in poor condition, is sufficiently intact to discern that it also had a relatively shallow loft. The juncture of the top and side panels breaks sharply, forming a tight boxed edge, and the top and sides are stitched together in a self-welted seam, with a thinly skived strip of the same leather folded and stitched between the panels to give the appearance of a thin cord (figs. 27, 28). This seamed seat is a characteristic of formal eighteenthcentury upholstery, so there is every reason to believe it is original. From a practical standpoint, the stitched assembly prevents the puckering noticeable on the lower edge of the current replacement seat of the Washington chair (see fig. 21). Looking at the inner back, it is apparent that the beveled boxed edge outlining the perimeter has a tighter break than is currently visible on the chair. It is also noteworthy that no diagonal stitched seams are apparent; a single piece of leather is stretched to fit the entire expanse of the compound curves making up the chair back.

The brass nail trim seen in the photograph appears much like it does today, with the number and spacing suggesting that the heads were sevensixteenths of an inch in diameter. An enlarged view of the nails shows an unexpected feature: they are applied above a thin strip of material, likely a skived length of the same leather approximately the same width as the nail diameter (figs. 29, 30). This is another detail occasionally found in surviving examples of eighteenth-century upholstery, probably included to provide a clean, sharp appearance to the edge of the overall expanse of significantly stretched and nailed leather.

The information from the scanned 1880s photograph clarified some of the changes that have occurred to Washington’s “uncommon chair” over time and greatly informed the reupholstery of Jefferson’s revolving chair. There is an uncanny similarity between the upholstery loft and visible details of the seats and inner backs of the chairs in the earliest photos of them, making it nearly certain that original upholstery lay below the loosely applied cover in Helen Duke’s photograph of Jefferson’s chair. A side-by-side comparison of the information from and pertaining to those objects presented a thoroughly convincing case that they were originally upholstered in a nearly identical manner (figs 31–34). A synthesis of this information, and other findings regarding the materials, form, and trim details of both chairs, guided the development of the upholstery scheme for the Jefferson chair. The conclusions of the study are presented below, followed by a brief discussion of some of the minimally intrusive techniques used to apply the upholstery.

A Synthesis of Findings

Correlating the findings from the studies of the upholstery of the Thomas Jefferson and George Washington chairs reinforces and enhances the understanding of both of these important historic objects. Viewed comprehensively, much of the evidence can be considered conclusive and essentially irrefutable, particularly in light of the identified similarity of the historic appearance of the two chairs’ upholstery despite the separate and distinctly different paths each took over the past 230 years. To be sure, some of the conclusions below are inferences based on information solely from the old photograph of Washington’s chair and, as such, are more interpretive, but the evidence is sufficiently comprehensive that re-creation of the chair’s upholstery was far from a speculative undertaking. Following are the essential findings, listed in order of certainty, that guided the reinterpretation of Jefferson’s revolving chair upholstery.

1. From the comprehensive evidence, it is clear that the Jefferson revolving chair’s initial upholstery reflected the prevailing neoclassical fashion of the late eighteenth century, with relatively square edges and slender profiles.

2. The Jefferson revolving chair, much like Washington’s “uncommon chair,” was originally upholstered in leather.

3. The leather cover was trimmed with closely spaced brass nails sevensixteenths of an inch in diameter.

4. Based on the evidence from early photographs of the Washington chair, it is likely that Jefferson’s inner chair back was constructed from a single piece of leather.

5. Judging from Helen Duke’s historic recollection regarding remnants of Jefferson chair leather, the written record regarding the Washington chair, and the 1787 description of Thomas Burling’s chairs being covered in red morocco leather, it is likely that the Jefferson chair had red leather, probably with a natural grain surface.

6. Assuming the foundation upholstery was still in place at the time of the earliest photo of the Jefferson chair, the inner chair back originally displayed a crisp but pronounced loft with a tight beveled boxed-edge upholstery running approximately one and three-quarters inches in from the outer edge of the sweeping chair back.

7. Based on the 1880s Hermitage photo of the Washington chair, and assuming the foundation upholstery was still in place at the time of the earliest photo of the Jefferson chair, the Jefferson chair seat originally displayed a crisp, relatively square seamed edge with relatively flat sides and shallow loft.

8. Based on the 1880s Hermitage photo of the Washington chair, it is likely that the decorative brass nails of the Jefferson chair were applied above a narrow strip of thinned leather.

Conservation Upholstery for Jefferson’s Revolving Chair

The research presented above engendered a vivid mental concept of the original appearance of Jefferson’s revolving chair. The chief intent of conservation was to make that concept a reality. This was a task complicated by the need to stabilize the frame, address dozens of veneer losses and a range of coatings issues, and apply new upholstery materials in a non-traditional manner to avoid the otherwise unavoidable intrusion and damage associated with standard nailed-on upholstery. The following account discusses only a few aspects of the overall project, focusing on techniques essential to achieving the desired historically accurate appearance of the chair.

The minimally intrusive system designed for the Jefferson chair provides the appearance of historic nailed-on materials while using a tiny fraction of the metal fasteners necessary for standard nailed-on upholstery. Because the complex curves of Jefferson’s chair back are outlined by very thin veneer cross-banding, the use of non-intrusive upholstery—the complete avoidance of metal fasteners—was rejected. Installing a non-intrusive system on such a chair would be prohibitively labor-intensive and could have resulted in both somewhat bulky edges and the potential for gapping. As it is, the system developed for the chair used only a modest number of quarterinch staples, the least intrusive functional metal fastener available, both to maintain the structural and surface integrity of the chair and to preserve important physical evidence of the chair’s history of upholstery treatments.

Many of the materials and techniques used to install the system have become standard practice over the approximately forty-year evolution of the field of upholstery conservation, a small subset of the art conservation profession, and detailed information on these and other approaches are now documented in a growing body of literature. Such is the case with the use of semi-rigid polyethylene foam, a material safe to use with historic objects and one that can be readily shaped to simulate upholstery foundation and loft. This material is used only on objects intended for museum exhibition; it is unsuitable for functional seating furniture. Shaped blocks of two-inch polyethylene foam, stacked in a horizontal brick-like fashion, comprise the curved back of the Jefferson chair upholstery (fig. 35). By carefully friction-fitting the blocks in the voids between frame members and then adhering them to one another as the stack progressed, the foam provided a very stable and secure foundation to the leather and decorative brass nails.

Polyethylene foam also served as the foundation for the seat, although it was laid above a supplemental deck of formaldehyde-free plywood to make a rigid base spanning the void within the seat frame. The seat foundation was shaped to fit both the height and the slope of the original nailing blocks at the stile/seat rail joints, which, along with the earliest photos of both the Jefferson and Washington chairs, were excellent indicators of the original height and contours of the seat. To provide a foundation surface with a smooth and slightly springy touch, much like old upholstery, thin polyester batting was laid above the foam on both seat and back before the leather was attached (fig. 36).[13]

Fitting and securing the leather to the inner back presented one of the greater challenges to the project. There was concern that a minimally intrusive fastening system might not withstand the tension required for a single piece of leather to conform to the concave gondola form. To address this concern, the leather was fully pre-stretched well before securing it to the frame. In standard upholstery, stretching leather to fit tight curves is a process that requires repeated steps of nailing and re-tensioning to achieve a smooth, even surface. This process can be very damaging to a frame already upholstered numerous times. Consequently, temporary sacrificial nailers were installed on the rear perimeter of the chair (fig. 37). These consisted of eleven lengths of five-sixteenths-inch-thick white oak, all steam-bent as needed to conform to the convex shape of the chair’s outer back. Each strip was temporarily secured to the outer back with a single half-inch staple at each end. The leather was then cut oversized, dampened, stretched over the inner back (with a plastic sheet barrier protecting the veneer banding) and secured to the oak strips using quarterinch staples. The steam-bent oak strips absorbed the repeated stapling necessary to achieve proper form and tension (fig. 38). The leather was allowed to dry thoroughly under tension for more than forty-eight hours, then trimmed to fit just within the veneer edges of the inner back, and the temporary nailers were removed. The leather was then secured to the surface using thin-profile hook-and-loop fasteners running the perimeter of the chair back approximately a half inch from the veneer banding, with one side adhered to the back of the leather and the other to the beveled edge of the foam foundation (fig. 39). While this served as the chief means to attach the leather evenly and securely, it was reinforced by light use of quarter-inch staples—one every two to two and a half inches on the sweep of the chair back. The leather was applied the same way to the edges of the outer back and seat, although far fewer staples were used in these areas since the leather was adhered under considerably less tension to these straight or convex surfaces.

Patterns for the circular top and its straight side panels were made, then the leather cut slightly oversize to allow for the seam. A strip of the same leather was thinned somewhat using a skiving knife, folded over, and stitched into the seam to create the appearance of a leather cord an eighth of an inch wide (fig. 40), that being the estimated width of the welt in the old image of the Washington chair (see fig. 27). Once stitched, the seat leather was installed as described above.

Application of the decorative brass nails became the final step in the upholstery process. Taking a minimally intrusive approach was especially important for reproducing these closely spaced rows of nails, since traditional nailed-on trim, if applied over the course of two or more upholstery campaigns, will destroy both the integrity of most nailing surfaces and important evidence of the earliest upholstery treatments. In the case of the Jefferson chair project, the fortuitous discovery of an apparently original leather strip below the brass nails of the Washington chair simplified the development of an effective design. The tips of the brass nails were cut off, leaving only a small amount protruding from the circular brass head. These were then riveted and glued to long strips of leather the width of the nail diameter (fig. 41). The completed strips were then glued directly to leather show cover adjacent to the veneer banding. Only a single full-shank brass nail was needed to secure the trim in the traditional manner, in an old hole in a particularly vulnerable location directly behind each of the arm terminals—a significant reduction of the potentially damaging 1,030 new nail holes that would have resulted from the use of traditional techniques.

The completed conservation upholstery for Thomas Jefferson’s revolving chair constitutes a somewhat subtle visual change from its appearance before treatment (figs. 42–44; see fig. 1). The earlier upholstery certainly drew upon the most obvious physical and documentary evidence: the patterns left on the frame by early brass nails, and the Helen Duke note recalling the former presence of red leather. Nonetheless, the foregoing study into the earliest upholstery treatments of both Washington’s “uncommon chair” and Jefferson’s revolving chair provides a new and compelling understanding of the original appearance of both. Imbued with the subtle changes to its form and detail as revealed by the research, Jefferson’s chair now stands as a much more accurate manifestation of the growing taste for French-inspired neoclassical furnishings among Jefferson and his contemporaries in the early days of the republic.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For assistance with this article, the author thanks David Bayne, Travis Bowman, Tabitha Corradi, Diane Ehrenpreis, Adam Erby, Linda Landry, Iris Heissenbuttel, Elisabeth Mallin, and Marsha Mullin. I am particularly grateful to Talitha Dadonna for her skillful contributions to the conservation and reupholstery of the Jefferson revolving chair and to Leroy Graves, Wallace Gusler, and Albert Skutans for introducing the author to the study, treatment, and reproduction of historic upholstery.

Travis M. Bowman, “Federal Hall Chairs at John Jay State Historic Site” (report prepared for the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation, Waterford, N.Y., 2018), p. 16; Helen Maggs Fede, Washington Furniture at Mount Vernon (Mount Vernon, Va.: Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association of the Union, 1966), p.40. “From Thomas Jefferson to Thomas Mann Randolph, Jr., 28 March 1790,” Founders Online, National Archives, https:// founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-16-02-0148. [Original source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 16, 30 November 1789–4 July 1790, ed. Julian P. Boyd. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1961, pp. 277–279.] Merrill D. Peterson, Thomas Jefferson & the New Nation (New York: Oxford University Press, 1970), p. 394.; Susan Stein, The Worlds of Thomas Jefferson at Monticello (New York: Harry Abrams in association with the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation, 1993), p. 267.

Charles L. Granquist, “Thomas Jefferson’s ‘Whirligig’ Chairs,” Antiques 109, no. 5 (May 1976): 56–60; Margaret Van Cott, “Thomas Burling of New York City: Exponent of the New Republic Style,” Furniture History 37 (2001): 32–50, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23 409213. Granquist and Van Cott also mention Jefferson’s ownership of a revolving Windsor chair dating 1760–1770 as possible evidence that he designed both his and Washington’s chairs. Recent paint analysis of the Windsor chair and its alterations indicate that it was converted to a revolving chair after 1790 (see the articles by Jim Gergat and Susan Buck in this volume). Peterson, Thomas Jefferson & the New Nation, pp. 390–93. Washington and Jefferson corresponded regarding Jefferson’s appointment as secretary of state in the months leading up to the latter’s arrival in New York. There was no mention of Jefferson’s providing a design for a revolving chair; Diane Ehrenpreis, “On the Hunt for French Material Culture in the Land of Midnight Sun,” Decorative Arts Trust Bulletin (blog), July 25, 2018, https://decorativeartstrust.org/on-the-huntfor-french-material-culture-in-the-land-of-midnight-sun-post/. The author thanks Ehrenpreis for providing images of European neoclassical revolving chairs, including the 1783–4 Daniel Roentgen chair pictured in this article.

Amy Hudson Henderson, “French & Fashionable: The Search for George and Martha Washington’s Presidential Furniture,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Havertown, Pa.: Casemate/Oxbow for the Chipstone Foundation, 2019), pp. 78–155.

Letitia H. Alexander, “Two Pieces of Historic Furniture,” House Beautiful 18, no. 6 (November 1905): 32. The secretary desk willed to Dr. James Craik along with the “circular” chair was purchased by Washington in 1797 from Philadelphia cabinetmaker John Aitken. In Craik’s will, probated February 21, 1814, he gave grandson James Craik West “the circular chair devised me by George Washington, Esquire.” He gave the secretary to James Craik, another grandson. Both pieces eventually made their way to Kentucky along with the respective families. The chair passed to James Craik West’s sister, Ann Margaret West Moore, who had married Alexander Moore of Alexandria. She died young, leaving three children. The eldest son died at the age of sixteen; the youngest went to sea and never returned. The daughter, Jane Jackson Moore, was sickly and not expected to survive, so Alexander Moore gave the chair to Andrew Jackson. She lived, married Randolph Coyle, and had two sons. According to Letitia Alexander, this history appears in a letter from Randolph Coyle to Andrew Jackson marked “Washington City, August 26, 1843,” in which Coyle asked for the return of the chair. Jackson turned the letter over to his executors but did not return the chair. It was inherited by his adopted son, Andrew Jackson Jr. (nephew of Jackson’s wife and son of Severn Donelson, her brother). He passed it on to his son Col. Andrew Jackson III, who was negotiating the return of the chair to Mount Vernon at the time of the 1905 article. The secretary desk had already been returned to Mount Vernon from Kentucky by descendants of the other branch of the Craik family. Granquist, “Thomas Jefferson’s ‘Whirligig’ Chairs,” pp. 1056–60; Granquist discusses Jefferson’s possible reasons for using his revolving chair with the concave-ended Windsor bench and rotating writing table even though Jefferson originally bought a mating concave-ended sofa from Burling for use with the chair.

Granquist, “Thomas Jefferson’s ‘Whirligig’ Chairs,” pp. 1058–9. Granquist assumed the metal plate was added at a later date to address wear from the rollers on the bottom of the chair proper. No wear is present, and all evidence indicates that the plate and its fasteners are original.

Helen Duke, in a note in Object Files at Monticello dated September 27, 1947, recalled that the chair “was done over in 1924 or 1925.“ Notes in the Monticello files also mention that Ernest LoNano undertook the 1948 reupholstery of the chair. LoNano ran a prominent upholstery and interior design firm in New York, working for clients such as Colonial Williamsburg, Winterthur, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and others. No records survive documenting his work on the Jefferson chair.

According to the Object File for the chair (acc. no. 1951-2, Curatorial Department, Thomas Jefferson Foundation, Charlottesville, Va.), “Several pieces of furniture escaped the Dispersal Sale at Monticello in 1827. Some articles having a close association with the beloved patriarch were retained by his family; among them were the revolving chair, revolving Windsor chair, and Windsor bench, which were taken to Edgehill, home of Jefferson’s grandson, Thomas Jefferson Randolph, and descended to his daughter, Carolina Ramsey Randolph. Miss Randolph bequeathed them to R. T. W. Duke Jr., and it is from his descendant that the TJMF acquired them in 1951.” R. T. W. Duke Jr.’s descendants were Mary and Helen Duke; Bowman, “Federal Hall Chairs,” p. 3, quotes a July 9, 1787, journal entry by the Rev. Manasseh Cutler (1742–1823) describing the interior of the Congress of Confederation’s meeting room at City Hall in New York, which contained thirty-six chairs made by Thomas Burling.

It is ironic that, in the past, these tightly stitched profiles were called “French edges” by American upholsterers, as it is now clear that this technique originated in England during the neoclassical period and was adopted by French upholsters approximately ten years later. See Peter Thornton, “Upholstered Seat Furniture in Europe, 17th and 18th Centuries,” in Upholstery in America and Europe from the Seventeenth Century to World War I, edited by Edward S. Cooke Jr. (New York: W. W. Norton,1987), p. 34.

The author and Talitha Daddona examined Washington’s “uncommon chair” at Mount Vernon on March 13, 2020, with the generous assistance of their curator, Adam Erby, assistant curator Elisabeth Mallin, and conservator Linda Landry.

Leroy Graves, conversation with the author, December 19, 2022.

Frank D. Morse, “Report on repairs to Washington’s uncommon chair,” July 8, 1954 (Object Files, Mount Vernon, Va.). The Morse report exists in both handwritten draft and edited typed forms, with some variation.

The author thanks Elizabeth Mallin, former assistant curator at Mount Vernon, for requesting the images of the chair on behalf of Mount Vernon, and to Marsha Mullen, vice president and chief curator at The Hermitage, for her efforts to locate the photographs for this project; Alexander, “Two Pieces of Historic Furniture,” p. 32.