Thomas Burling, sofa, New York City, 1790. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with ash secondary. H. 38 1/2", W. 57 1/4", D. 27 1/2". (©Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Thomas Burling, revolving armchair, New York City, 1790. Mahogany and mahogany with ash; iron and brass. H. 48", W. 25 7/8", D. 31". (©Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing the sofa illustrated in fig. 1 adjacent to the armchair illustrated in fig. 2. Burling made these pieces so that their banding and seat heights aligned.

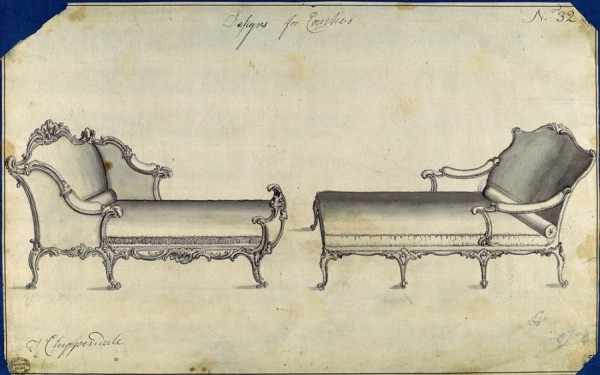

Thomas Chippendale, Designs for Couches, London, 1761. Ink and gray wash on paper. 7 3/16" x 13 1/16". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1920). This is a preparatory drawing for the third edition of The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director.

Detail showing the dowel construction used for the arms of the sofa illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Leroy Graves.) Conservator Leroy Graves repaired the previously damaged arm.

Detail showing an arm of the sofa illustrated in fig. 1, reinstalled after conservation. (Photo, Leroy Graves.)

Detail showing how the back of the sofa illustrated in fig. 1 is screwed to the rear seat rail. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing the crest of the sofa illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Joseph Wright, Frederick Augustus Conrad Muhlenberg, New York, 1790. Oil on canvas. 47 1/6" x 37". (Courtesy, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.) Wright’s careful rendering of the speaker’s chair provides important evidence for the appearance of the cock-beading and box-edge upholstery on Jefferson’s sofa.

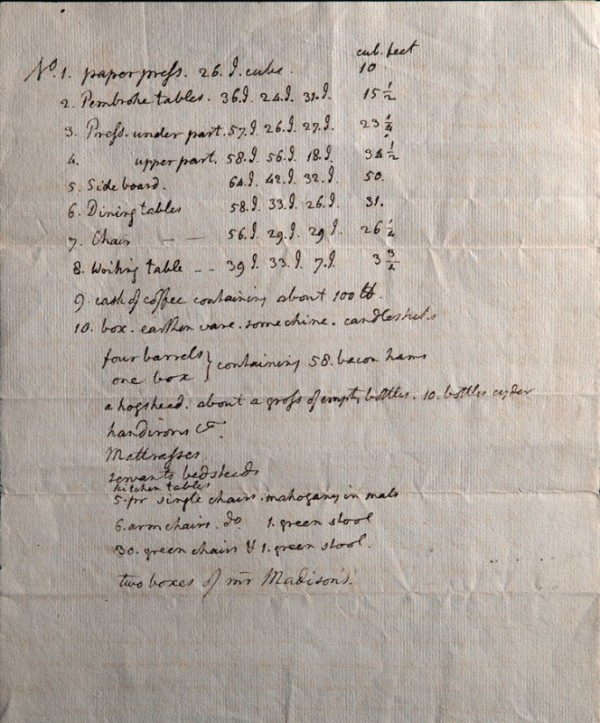

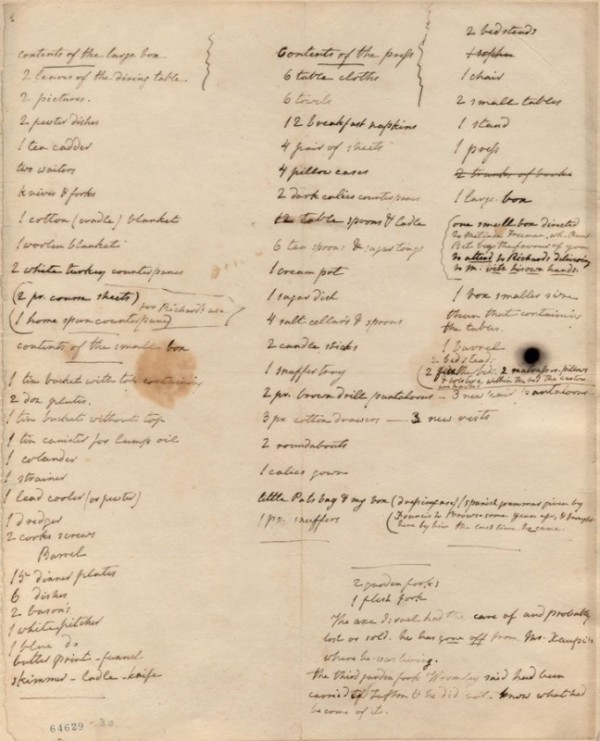

Thomas Jefferson, packing list, New York, August 31, 1790. Pen and ink on paper. (©Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello.) During the move, Jefferson itemized a list of crates and boxes that conveyed his furniture and household goods from New York to Philadelphia.

David J. Kennedy, Residence of Thomas Jefferson in 1793, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, undated. (Courtesy, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.)

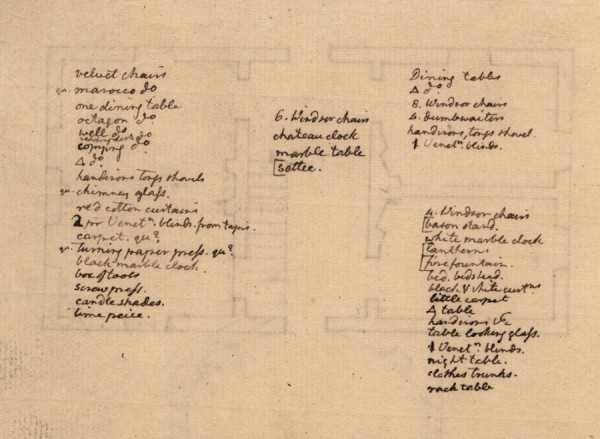

Thomas Jefferson, floor plan for the house at Gray’s Ferry, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (verso), 1793. (Courtesy, Massachusetts Historical Society, Coolidge Collection of Manuscripts.) You can see the outlines of the rooms through the paper, indicating Jefferson’s intentions for which furnishings in which spaces. The settee appears at the bottom of the middle column.

Lawrence Allwine, Windsor bench, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1798. Maple, tulip poplar, white pine, and unidentified ringporous hardwood. H. 18 1/2", W. 25 1/4", D. 55". (©Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

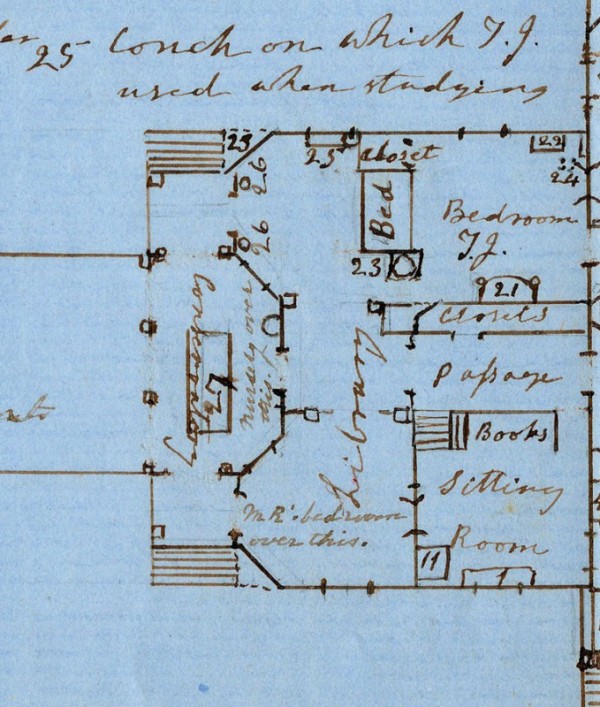

Cornelia Randolph, details of plan for the first floor of Monticello showing Jefferson’s private suite, Monticello, Albemarle County, Virginia, ca. 1826. (Courtesy, University of Virginia Library.)

Virginia Randolph Trist, inventory of items sent from Monticello to Washington, D.C., 1829. (Courtesy, Library of Congress, Nicholas Philip Trist Papers.) The “sopha” appears in the top right corner of the list.

Detail showing an arm pad of the sofa illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Leroy Graves.)

Cabinet, Monticello, Albemarle County, Virginia. (©Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

IT WAS STIFLINGLY hot and humid in central Virginia in the middle of August 1825 when Mary Jefferson Randolph wrote to her newly married sister. In the days prior, Thomas Jefferson had recorded morning temperatures in the low eighties, evenings in the mid-nineties, with little spurts of rain—not enough to cool anything off, but just enough to make the air around Monticello heavy with humidity. Mary Randolph described a meaningful change, perhaps caused by uncomfortable weather, in the way her eighty-three-year-old grandfather welcomed guests to Monticello:

[He] latterly allowed mama to relieve him from much of the fatigue of company by consenting that she should receive all the visitors who come, make his excuses to those who can be refused, and sometimes, when that is impossible, admit them to his bed room where he can recline at ease on his own sofa.

Jefferson had long been known for practicing an informal sociability; as president, he welcomed diplomats and guests in casual clothing and did not assign seats at dinner. At Monticello, at least one uninvited visitor traversed the boundaries of propriety with its structures of introduction to enjoy a glass of wine with the venerated statesman. In her letter, Mary reported a new development. As an old man, Jefferson had finally allowed family members to intercede with the stream of visitors who came to Monticello looking to satisfy their curiosity about the house and its occupants. In the compromise that emerged during the hot and sticky summer, Jefferson remained accessible to some. His bed chamber was directly off the entrance hall, and his doors likely remained open for ventilation. He could surely hear visitors, if not see them. At the same time, reclining and comfortable, he was secluded in his private rooms only to be disturbed infrequently. The focus of this article is the sofa Jefferson selected for his ease, the one he had commissioned from New York cabinetmaker Thomas Burling thirty-five years earlier in 1790 (fig. 1). Throughout his long life, Jefferson’s sofa and the various ways he used it revealed the emphasis he placed on comfort, his experimental approach to furniture design, his collaborations with craftsmen to make pieces to his exacting specifications, how he expected furniture to work together, and how he adapted use in response to changing physical needs, especially as he aged.[1]

The object under scrutiny is one of the two “green stools” that appear on a packing list of furniture and other goods that Jefferson moved from New York to Philadelphia in the fall of 1790. Not stools in the traditional sense, the pieces on the list were six-legged sofas. Designed and built with removable arms and back, the sofa transformed into a bench, with ends shaped to receive the rounded seat of the revolving armchair Jefferson commissioned from Burling at the same time (figs. 2, 3). The sofa and chair were integral fixtures of Jefferson’s suite of metamorphic office furniture. Scholars have identified French inspirations, including the demi-canapé, the duchesse brisee, and the dormeuse ou tête-à-tête. When brought together, the bench section of the sofa and armchair also resemble couches illustrated in the third edition of Thomas Chippendale’s The Gentleman and CabinetMaker’s Director (fig. 4). The sofa’s hybridized design indicates that Jefferson had significant input, reflecting his observations of French furniture during his years in Paris (1784–1789). Together, he and Burling made something new and very personal. The sofa was the most adaptable object Jefferson commissioned, meant to function both as part of his writing suite and in a conventional manner. The sofa reflects Jefferson’s flexible and adaptive approach to furniture design and use, a theme that runs through decades of interaction with cabinetmakers and the enslaved joiners at Monticello.[2]

Two features set Jefferson’s sofa apart from contemporaneous and earlier examples: the side rails curve inward, allowing them to fit snugly against the seat of his rotating armchair; and the arms are designed to be removable with ease. To accomplish the latter, Burling used dowels to attach the arms to the front legs and back (figs. 5, 6). This is the earliest documented use of dowel construction in America; however, New York cabinetmakers and chair-makers routinely used dowels for joinery in conventional seating beginning during the 1810s.

Conversion of the sofa into a bench required first lifting the arms up and moving them to the side to disengage the dowel joints, and then unscrewing and removing the back (fig. 7). Because the center stile is exposed, Burling covered it with crossbanded veneer matching that used elsewhere. Aside from the back pad and parts of the arm pads, which retain fragments of their haircloth cover, the original upholstery for the sofa does not survive. However, nail sites on the top of the front and rear seat rails indicate the former presence of five strips of linen webbing that stretched from front to back, interwoven with three strips that ran side to side.[3]

Jefferson’s sofa is restrained in both form and decoration, having curved arm supports and arms, a single band of line inlay on the rails, and applied cock-beading on the crest, a feature occurring frequently on contemporaneous French and English furniture (fig. 8). Applied cock-beading and boxedge upholstery appear in a 1790 portrait of Frederick Augustus Conrad Muhlenberg, speaker of the United States House of Representatives (fig. 9). Thought to have been made by Burling, the speaker’s chair was part of the federal government’s furniture in New York City.[4]

From New York to Philadelphia to Monticello

Jefferson ordered the sofas in New York City in the spring of 1790. One can imagine the conversations between him and Burling, with Jefferson describing the metamorphic qualities he desired and Burling recognizing structural problems that the required adaptations might create. Jefferson envisioned the sofa as part of an interconnected suite comprising his revolving armchair, a table with a rotating top, and a rotating stand. Every object in that writing suite was designed to move and be reconfigured for his productivity and comfort.

Jefferson received the furniture made by Burling during the summer of 1790, and all of those objects were sent from New York to Philadelphia later that fall (fig. 10). James Hemings, an enslaved man who belonged to Jefferson and attended to him in Paris, New York, and Philadelphia, probably oversaw the packing and transportation while Jefferson relocated. The packing list gives precise measurements for the crates but is more generalized in other regards. Appearing below the mention of five pairs of single mahogany chairs wrapped in mats and adjacent to that for the six mahogany armchairs are two separate entries, each for “1. green stool.” The chairs were shield-back examples that Jefferson used for dining. The thirty green chairs on the list were Windsors intended for use at Monticello. As later documentation confirms, the sofas were shipped with their arms and backs removed. In his brief description of the pieces, and by the position of the entries for the stools/sofas on the list near other examples of mahogany seating furniture packed in mats, Jefferson hinted at the sofas’ appearance and how they worked. The packing list is the only evidence that Jefferson may have started with two sofas, as only one sofa appears in subsequent inventories and correspondence.[5]

In Philadelphia, Jefferson rented a house at 274 High Street (now the 700 block of Market Street) from December 1790 until March 1793. Assuming the presence of two sofas, he likely used one as a bench pulled up to the revolving armchair in his highly personalized writing suite and the other in a conventional fashion. The year 1793 was one of professional transition for Jefferson as he made plans to leave public life for retirement at Monticello. During this unsettled time, inventories, plans, and lists reveal him making choices about furniture, espcially how and where pieces were used. Increasingly disillusioned with his role as secretary of state, Jefferson intended to resign his position at the end of President Washington’s first term in March 1793. Planning to leave Philadelphia, Jefferson allowed his in-town lease to lapse. Shortly after, he decided to stay in the city until the end of September and relocated to a house on the Schuylkill River at Gray’s Ferry (fig. 11). In preparation for occupying that house, Jefferson drew a floorplan and, on the back of the plan, he listed the pieces of furniture he intended for use in each room (fig. 12). For the hall, he designated six Windsor chairs, a chateau clock, a marble table, and, in a half bracket, a settee, the latter a sofa to be used as such rather than as part of a writing suite. The spring of 1793 saw Jefferson significantly reduce his household, including the temporary dissolution of his writing suite. He kept two pieces from that suite with him, the octagonal table and “turning paper press,” but he used another seat in place of the revolving armchair at Gray’s Ferry and reassigned the bench as a settee in the central hall.[6]

The disruption of his writing suite reveals the enormity of Jefferson’s household reorganization when he moved from High Street to the riverside villa. The plan for Gray’s Ferry documents the pieces retained in Philadelphia, and Jefferson further edited his furnishings throughout the rest of the year. Of the two sofas that arrived in Philadelphia in 1790, one appears on Jefferson’s floor plan, but the other is absent from related inventories, correspondence, and plans, suggesting Jefferson no longer had it. During 1793 he gave objects to friends, sold furnishings he did not plan to use in Virginia, and sent many things back to Monticello. In January, Jefferson gave a plaster bust of himself by French sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon to his friend David Rittenhouse and referred to his “useless furniture” in the note accompanying the gift. Although undocumented, Jefferson could have given the second Burling sofa to a friend, employee, or acquaintance in Philadelphia. A few weeks later he informed his daughter that he had “sold such of my furniture as would not suit Monticello.” Months later, with his plans established, Jefferson wrote out an inventory of fifty-one packages for transport to Monticello via Richmond under the oversight of his French butler, Adrien Petit. Much of Jefferson’s art collection, mirrors, and public and private furniture left Philadelphia at this time, including “42. [un] fauteuil,” thought to be his revolving armchair. Comparing Petit’s list with Jefferson’s annotated floorplan of Gray’s Ferry indicates that the revolving writing table from the suite made by Burling also went back to Monticello. The Gray’s Ferry interlude represented a curious moment in Jefferson’s carefully devised yet constantly evolving furnishing schemes. He chose particular pieces to remain with him as he simultaneously broke up established sets and, with only two exceptions, replaced formal seating furniture with Windsor chairs. Expecting his occupation of Gray’s Ferry to be of short duration, perhaps he kept only what he deemed essential for comfort and productivity.[7]

Jefferson occupied the house less than six months. At the end of September 1793 he left for Monticello, then returned to temporary lodgings in the city for the last weeks of the year. He departed Philadelphia on January 5, 1794, and, even though he resided in the city as vice president from March 1797 to May 1800, he never set up a household there again. Jefferson and his remaining furniture traveled back to Monticello for what he assumed would be his retirement. He embarked on elaborate plans to expand Monticello into the twenty-one-room house known today, filled with the furniture and art he collected in Europe, commissioned in New York, and purchased in Philadelphia. In the “cabinet” at Monticello, Jefferson reinstalled the writing suite he had imagined and commissioned in New York. A notable change occurred in 1798, when he paid Philadelphia chair maker Lawrence Allwine twenty-six dollars for a “stick sofa and matras” (fig. 13). This Windsor bench was a custom order, with incurvate ends shaped to receive the rounded seat of Jefferson’s revolving armchair.[8]

After receiving the stick sofa at Monticello, Jefferson adapted his writing suite again, using the armchair with the bench instead of the metamorphic sofa. Removing the arms and back from the sofa may have proved onerous, requiring one or more of Jefferson’s enslaved people to enter his private rooms with the tools required for the conversion. Even in bench form and on casters, the metamorphic sofa would have been heavy to move, whereas the Windsor bench was light weight and easy to manipulate without assistance. Jefferson first complained of “rheumatism,” which may have been a form of osteoarthritis, in 1794, and during the remainder his life he suffered from bouts of aching and swollen limbs, particularly in his legs. At times the symptoms were so severe that he was bedridden for weeks at a time. Jefferson never explained his reasons for commissioning the Windsor bench, but that object used in conjunction with his revolving armchair may have been more comfortable than the sofa/chair combination. Comments by visitors to Monticello and family members alike indicate that by 1798, Jefferson preferred using the Burling sofa with its arms and back attached, as he had at Gray’s Ferry.[9]

There is no indication that Jefferson took his metamorphic sofa to Philadelphia during his term as vice president or to the President’s House in 1801. Climate, comfort, and mobility dictated his ongoing use of the Burling sofa in his private rooms at Monticello. After Bostonians George Ticknor and Francis Calley Gray visited Monticello in February 1815, the latter recalled that their host took them “from his library into his bed chamber where, on a table before the fire, stood a polygraph with which he said he always wrote.” Jefferson recorded air temperatures consistently below or hovering around freezing in the days prior to the Bostonians’ arrival, and Gray made note of encountering iced-over rivers. The “cabinet” that typically housed Jefferson’s writing suite did not have a heating source and, with numerous windows, the room became unusably cold during the winter. Prior to Gray and Ticknor’s arrival, Jefferson had ordered enslaved domestic worker Burwell Colbert, who was likely assisted by Israel Gillette, to move his writing equipment to a warmer and more sheltered location in his bedchamber.[10]

Shortly after the Bostonians’ visit, Jefferson prepared a list of taxable items in his possession, which included land, enslaved people, and specialized household furniture: clocks, paintings, mahogany and gilded furniture, silver, and mirrors. On a draft list, Jefferson noted “1. Sopha,” followed by six sofas with gilding and one ornamented solely with paint. Presumably, the first sofa on the list was his metamorphic example. Jefferson purchased at least four sofas and many other pieces of furniture during his five-year posting as the minister plenipotentiary to the Court of Versailles in France. After returning to the United States, he hired a French shipper named Grevin to inventory and pack those furnishings, which required eighty-six crates. Grevin’s packing list includes a méridienne and six chairs covered in Utrecht velvet in crate twenty-three; a blue silk ottoman with cushions and four similar chairs in crate forty-four; an ottomane in red morocco leather in crate forty-five; a méridienne trimmed in copper in crate fifty-six; and two crimson sofa cushions (deux cousin de canapé cramoisie) in crate twenty-four. Adrien Petit called the blue ottoman “un Sopha” and the red morocco leather ottoman “l’Ottomane de votre bibliotheque.” Both were sent to Monticello in May 1793, but they do not appear in the documentary record afterwards. The méridienne, likely upholstered in red Utrecht, was probably sold in Phil adelphia in 1793 or 1794, and the disposition of the méridienne trimmed in copper remains unknown. Jefferson commissioned six sofas in Philadelphia in 1802 and purchased a plain painted sofa at an undetermined time. Martha Jefferson Randolph’s inventory of furnishings at Monticello, likely taken in 1826, lists a single sofa and cushion in the parlor and two sofas with cushions in the tea room, but it does not include furnishings from Jefferson’s private rooms. The pieces on Martha’s inventory were probably examples from the Philadelphia commission, which included sofas with cushions.[11]

In Mary Randolph’s August 1825 letter about Jefferson receiving visitors reclined in his bed chamber, she located the metamorphic sofa in his private rooms and documented his continued preference for that object thirty-five years after he commissioned it. He could have had any piece of furniture brought for his use, and his choice suggests that he found the sofa comfortable. The suggestion of comfort is bolstered by the appearance of the sofa on an annotated floorplan of Monticello drawn shortly after Jefferson’s death by his granddaughter Cornelia Jefferson Randolph. On the plan, she located the sofa in the “cabinet”: “25. Couch on which T. J. used when studying” (fig. 14). Cornelia’s note confirms Jefferson’s use of the sofa after replacing it with the Windsor bench in the writing suite. Jefferson famously described his “canine appetite for reading” in a letter to John Adams in 1818, a pleasure he likely took while relaxing on his metamorphic sofa. Even though Jefferson claimed to rise with the sun, he habitually enjoyed a rest during the day, referenced in an anecdote of him retiring for a nap on a couch at the President’s House accompanied by his faithful pet mockingbird. As he aged, Jefferson prized a sofa in his private rooms as a comfortable place to relax, especially one that could be moved from one room to another depending on the season or his inclination.[12]

Thomas Jefferson was in financial ruin at his death on July 4, 1826. To settle his debts his family sold Jefferson’s enslaved people, furnishings, equipment, and livestock at auctions in 1827 and 1829 and his house and more than 500 acres in 1831. In the interim, the house was in flux, with descendants sorting out remaining furniture, claiming what Jefferson had left them, and negotiating for special objects. In 1829, while setting up their household in Washington, D.C., Jefferson’s grandson-in-law Nicholas Trist sent his wife Virginia a list of objects he wanted retrieved from Monticello, including “the bed-room sofa, wh. yr. grandfather gave me.” Trist had been a frequent visitor and resident at Monticello and enjoyed a close relationship with Jefferson. His description of the sofa as a gift from his wife’s grandfather indicates Jefferson may have singled the sofa out for Trist while he was alive, as it neither appears in his will, nor was it offered for sale at the auctions. Two weeks later, with the wagon on its way, Virginia informed her husband concerning objects that were left behind because of space and issues regarding packing the sofa:

The sopha I intended to have rolled in sister Jane’s old scrap carpet, but that could not have gone without leaving some of the bedding, and it was thought would be racked to pieces in the journey. Brother Jeff thinks that if it is taken to pieces it may be packed easily in a box, and that a large one would not be required.

An inventory in Virginia’s hand confirms details from her letter about what traveled to Washington and what remained in central Virginia, and on the list the word “sopha” is crossed out. (fig. 15). Thomas Jefferson Randolph’s advice recognized the sofa’s metamorphic structure—“that it can be taken into pieces”—and acknowledged its fragility. Surviving documentation does not reveal the details of the sofa’s shipping, but it finally arrived in Washington by November 1829, along with the revolving Windsor chair that is the subject of James Gergat’s article in this volume.[13]

Nicholas Trist’s description of the “bed-room sofa” confirms two crucial details about that object and how Jefferson used it. Even though Cornelia Jefferson Randolph located the sofa in Jefferson’s “cabinet “on her plan, Trist called his object “the bed-room sofa,” supporting Mary Randolph’s 1825 account of the sofa’s whereabouts. Taken together, these references indicate the sofa moved. Trist’s description also reveals that Jefferson used the sofa in a conventional manner later in life. Members of the Trist family kept the memory of the metamorphic sofa alive. On the rear seat rail, a descendant installed a plaque, stating:

THIS LITTLE SOFA MADE AT MONTICELLO AFTER THOMAS JEFFERSON’S PLAN/ THE ARMS WERE REMOVABLE AND A REVOLVING ARM CHAIR/ROUNDED IN THE FRONT OF THE SEAT AND MADE TO FIT INTO EITHER END/WAS GIVEN AWAY AND I BELIEVE IT TO BE IN/THE PHILOSOPHICAL SOCIETY IN PHILADELPHIA, PA/ GIVEN BY THE PRESIDENT WHO HAD THIS CHAIR FROM MY FATHER N.P. TRIST/THOMAS JEFFERSON WAS THE INVENTOR FOR HIS OWN USE OF THE REVOLVING CHAIR

Although many of these details are untrue (the sofa was not made at Monticello; it was not made for use with the revolving Windsor chair with Trist provenance at the American Philosophical Society; and Jefferson did not invent revolving seating), the plaque documents the family’s regard for it. Jefferson descendants preserved knowledge of the sofa as a very personal item, made to Jefferson’s specifications, intended to work in concert with other pieces of furniture, and closely associated with their famous ancestor. They also continued using it as a sofa. The latter is further documented in family photographs from the early twentieth century.[14]

The sofa remained with descendants of Nicholas and Virginia Trist until it came to Monticello in 2011. In 2016 and 2017 furniture conservator Leroy Graves studied, stabilized, and treated the piece and designed a minimally intrusive upholstery system for it. His observations confirmed that the arms and back were intended to be removable even though this unusual feature introduced weak points into the sofa’s structure. Graves removed screws and plates added later to reinforce the arms, rebuilt the damaged mortise and tenon joints, and repositioned the arms and arm supports into their correct positions.[15]

The stitched upholstery pad for the back of the sofa and the arm pad for the proper right arm rest survived intact (fig. 16). The shape of the pad indicated upholstery with a box-edge profile, reinforcing the clues provided in Wright’s 1790 portrait of Muhlenberg. Tiny fragments of hair cloth revealed the type of fabric used for the original upholstery, but not enough remained to determine pattern. Before Graves’s study, it was assumed the sofa had been upholstered in red leather, matching the original covering of the revolving armchair. Graves noted the absence of staining (which would have resulted from the corrosive effects of tannic acid in the leather interacting with the brass nails) and fragments of haircloth on the arm pads to indi cate an alternative treatment. The reference to green stools from Jefferson’s packing list informed the choice of green haircloth for the new upholstery, and impressions of the original brass nails indicated their size and spacing.[16]

With the 2017 reinstallation of Jefferson’s “cabinet,” extensive conservation, and research into the Burling commission and packing list, the sofa has reclaimed its place as part of Jefferson’s highly personalized writing suite (fig. 17). Inspired by objects he encountered in France and commissioned for specialized use, the sofa has revealed Jefferson’s adaptive mind at work. Its well-documented history as it was moved from New York to Philadelphia to Monticello in the 1790s, within Monticello in the 1810s and 1820s, and after, tells a story of change and repurposing. Jefferson and Burling designed and built the sofa to be adaptable across use and reuse in different houses, rooms, situations, and purposes over the course of decades. Jefferson continued using it until the end of his life as comfort became more necessary and elusive for him. Built solidly enough to survive more than thirty-five years of continuous use, its close association with Jefferson—and his adaptation of it in different contexts—made the sofa a relic of Thomas Jefferson in the memories of his grandchildren and later descendants, one that revealed Jefferson’s flexible approach to furniture.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS For assistance with this article, the author thanks Diane Ehrenpreis and Leroy Graves.

Mary J. Randolph, Nicholas P. Trist, and Virginia J. Randolph Trist to Ellen W. Randolph Coolidge and Joseph Coolidge, Monticello, Va., August 18, 1825, Jefferson Quotes and Family Letters, https://tjrs.monticello.org/letter/37 (hereafter cited as JQFL). Thomas Jefferson made twice-daily observations of the weather for nearly fifty years; the data for August 1825 comes from Daily Record, 1 November 1802–1829, June 1826, Coolidge Collection of Thomas Jefferson Manuscripts, 1705–1827, Other Volumes, 1766-1824, Weather Recordings, 1782–1826, p. 86, Massachusetts Historical Society (hereafter cited as MHS: Coolidge Collection). Many scholars have written about Jefferson’s informal approach to socializing during his presidency; an overview can be found at the Thomas Jefferson Encyclopedia, https://www.monticello.org/ site/research-and-collections/dining-presidents-house. The story about the uninvited guest comes from an account by Isaac Briggs, who came to Monticello in 1820. His experience is included in Visitors to Monticello, edited by Merrill D. Peterson (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2000), pp. 80–81.

“Thomas Jefferson’s List of Packages Sent to Philadelphia from New York, 31 August 1790,” accession #2018-8, Thomas Jefferson Foundation (purchased at auction by the Thomas Jefferson Foundation [hereafter TJF] in 2018). Susan R. Stein, The Worlds of Thomas Jefferson at Monticello (New York: Harry N. Abrams in association with the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation, 1993), pp. 266–67; Diane C. Ehrenpreis, “‘Threads & clues of it’: Thomas Jefferson’s New York Furniture” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Haverton, PA.: Casemate Publications/Oxbow Books for the Chipstone Foundation, 2023), pp. 2-69.; see also her forthcoming chapter, “‘Every Convenience for a Man of Letters’: Thomas Jefferson’s Writing Suite,” in The Material Culture of Writing, edited by Cydney Alexis and Hannah Rule (Logan, Ut.: Utah State University Press, 2022), ch. 7; Diane Ehrenpreis and Endrina Tay, “Enlightened Networks: Thomas Jefferson’s System for Working from Home,” in The Spirit of Inquiry in the Age of Jefferson: Papers from the Conference Held at the American Philosophical Society, Transactions of the American Philosophical Society Held at Philadelphia for Promoting Useful Knowledge 110, part 2 (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society Press, 2021).

Philip D. Zimmerman, “A Beekman Legacy: 1819 French Tapestry Chairs by John Banks of New York,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Haverford, Pa.: Casemate/ Oxbow, 2019), pp. 156–213; Leroy Graves, Monticello Sofa Treatment Report, 2017, revised by Diane Ehrenpreis, March 3, 2021, Curatorial files, TJF.; Charles L. Granquist, “Thomas Jefferson’s ‘Whirligig’ Chairs,” Antiques 109, no. 5 (May 1976): 1058.

Thanks to Diane Ehrenpreis for alerting me to the presence of cock-beading, which emerged in conversation between her and Leroy Graves, and for the reference to both elements in the Muhlenberg portrait. For the most comprehensive study of Thomas Burling’s furniture, see Margaret Van Cott, “Thomas Burling of New York City, Exponent of the New Republic Style,” Furniture History 37 (2001): 32–50. “Reprint of the Cabinet-Makers’ London Book of Prices, 1793,” Furniture History 18 (1982): i, iii-xvi, 1–266; Ehrenpreis, “Every Convenience for a Man of Letters”; Robert L. Self, “Jefferson Sofa,” 1994, Curatorial files, TJF.

“Inventory of goods acquired in New York City”; Ehrenpreis, “Every Convenience for a Man of Letters”; Ehrenpreis and Tay, “Enlightened Networks’; Ehrenpries, “ ‘Threads & clues of it’ ”. The intended disposition of the thirty Windsor chairs can be found in “Memorandums to Henry Remsen, 31 August 1790,” The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Founders Online, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., https://founders.archives. gov/ (hereafter cited as PTJ Digital).

Steve Currall, “Jefferson’s Monticello on the Schuylkill,” Hidden City Philadelphia, https://hiddencityphila.org/2011/12/jefferson%E2%80%99s-monticello-on-the-schuylkill/, accessed October 25, 2021; Thomas Jefferson, “Philadelphia: house (plan),” 1793, N251; K120, MHS: Coolidge Collection.

Thomas Jefferson to David Rittenhouse, Philadelphia, January 7, 1793, PTJ Digital; Thomas Jefferson to Martha Jefferson Randolph, Philadelphia, January 26, 1793, PTJ Digital. Jefferson’s enclosure for Petit included a sofa with cushions in package 7; that the sofa is described with cushions and is listed in a case with other bedroom furniture indicates that this sofa is a French piece that was part of Jefferson’s bedroom suite. Enclosure: Adrien Petit’s List of Packages Sent to Richmond, Philadelphia, [ca. 12 May 1793], PTJ Digital; Thomas Jefferson, “Philadelphia: house (plan),” 1793, N251; K120, MHS: Coolidge Collection.

Jefferson was intensely transitory in Philadelphia at the end of 1793. With the yellow fever epidemic cresting, he left the city for Monticello in the middle of September 1793, returning in early November to find that the government had fled the fever and established temporary quarters in Germantown. Jefferson lodged in Germantown and, when the government returned to Philadelphia, he rented Italian merchant Joseph Mussi’s house on 7th and Market Streets in Philadelphia for five weeks between November 30, 1793, and his ultimate departure for Monticello on January 5, 1794. Jefferson’s January 1794 departure saw yet another sale of furniture: twelve chairs to a boardinghouse keeper named Mary Kean for fifty-one dollars. When Jefferson returned to Philadelphia as vice president in March 1797, he spent the first night with James Madison, then subsequently stayed at John Francis’s hotel at 12 South Fourth Street during all of his trips to Philadelphia. Thomas Jefferson, Memorandum Book 1793, September 16, 1793, n. 60; November 12, 1793, n. 69, PTJ Digital; “Philadelphia,” Thomas Jefferson Encyclopedia, https://www.monticello.org/site/research-and-collections/philadelphia, accessed October 28, 2021; Thomas Jefferson, Memorandum Book 1794, January 5, 1794, n. 91, PTJ Digital. Cabinet is the term Jefferson used to describe the room that contained his writing suite. Twenty-six dollars is a high price for Windsor furniture, although the sofa and cushion were highly customized work. Nancy Goyne Evans has documented that Windsor chairs produced for export typically sold in a range of one to three dollars per chair in the late 1790s and early 1800s. For comparison, the green silk upholstered French sofa that George Washington purchased in 1790 from the Count de Moustier was valued at thirty dollars. Nancy Goyne Evans, “Windsor Furniture Making in Boston: A Late but Innovative Center of the Craft,” in Boston Furniture, 1700–1900, edited by Brock Jobe and Gerald W. R. Ward, (Boston: Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 2016), pp. 190–92; “Articles purchased by the President of the United States from Mosr. Le Prince Agent for the Count de Moustier,” Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association Archives, Mount Vernon, Va., Founders Online, https://founders.archives. gov/?q=cushion&s=1111311111&sa=&r=38&sr=; Memorandum Book 1797, March 2, 1797, n. 84, and March 13, 1797, PTJ Digital.

For an overview of Jefferson’s experiences with rheumatism, see “Arthritis,” Thomas Jefferson Encyclopedia, https://www.monticello.org/site/research-and-collections/arthritis; for the association of Jefferson’s rheumatism with osteoarthritis, see Gordon W. Jones and James A. Bear, “Thomas Jefferson’s Medical History,” Unpublished report, 1979, TJF.

Francis Calley Gray, “Boston Comes to Monticello” in Visitors to Monticello, p. 55–60; Thomas Jefferson, Daily Record, January 1, 1815–February 28, 1815, p. 70, MHS: Coolidge Collection.

“Thomas Jefferson’s Statement of Albemarle County Property Subject to Federal Tax, 14 May 1815,” PTJ Digital; “Grevin Packing List,” July 17, 1790, William Short Papers, Manuscripts Division, Library of Congress; George Jefferson to Thomas Jefferson, Richmond, September 8, 1802, PTJ Digital; Daniel Rapine to Thomas Jefferson, September 11, 1802, PTJ Digital; John Barnes to Thomas Jefferson, September 21, 1802, PTJ Digital.

Mary Jefferson Randolph to Ellen W. Randolph Coolidge, Monticello, August 18, 1825, JQFL; Cornelia Randolph, “Floor Plan of Monticello, c. 1826,” MSS-5385-ac, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va.; Thomas Jefferson to John Adams, Monticello, May 17, 1818, PTJ Digital; Thomas Jefferson to Dr. Vine Utley, Monticello, March 21, 1819, PTJ Digital; Margaret Bayard Smith, and Gaillard Hunt, The First Forty Years of Washington Society: Portrayed by the Family Letters of Mrs. Samuel Harrison Smith (Margaret Bayard) From the Collection of Her Grandson, J. Henley Smith (New York: Scribner, 1906).

Nicholas Philip Trist to Virginia Jefferson Randolph Trist, Washington, D.C., May 8, 1829, Nicholas Philip Trist Papers, #2104, Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (hereafter NPT Papers UNC); Virginia Jefferson Randolph Trist to Nicholas Philip Trist, Edgehill, Va., May 21, 1829, ibid.; Virginia Jefferson Randolph Trist, “Contents of the large box,” [undated manuscript, likely May 1829], Nicholas Philip Trist Papers, Library of Congress; Virginia Jefferson Randolph Trist to Nicholas Philip Trist, Richmond, October 16, 1829, NPT Papers UNC; Martha Jefferson Randolph to Nicholas Philip Trist, Edgehill, Va., October 26, 1829, ibid.

The sofa has two more labels on the back, recording twentieth-century damage and repair. One of two labels reads: “In the winter of 1970, under the weight of a slim man, the left front leg (from the viewpoint of a person sitting on the sofa) split upward from the caster socket for most of its length. The broken leg was replaced by Mr. William P. Harrison, Jr., a skilled carpenter in the employ of Henry W. Farrow & Sons of Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania. Nov. 1973.” The other label corrects the narrative: “I have long intended to correct the obvious error in my note of Nov. 1973. Perfectly clearly, the leg was glued and clamped by Bill Harrison—not replaced. Feb. 1979.”

Graves, “Monticello Sofa Treatment Report”; Self, “Jefferson Sofa.”

Graves, “Monticello Sofa Treatment Report.”