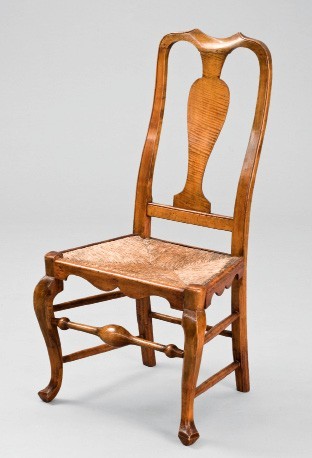

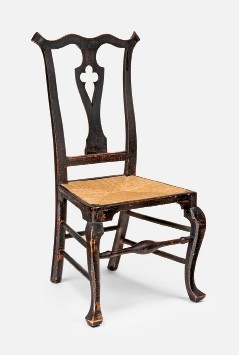

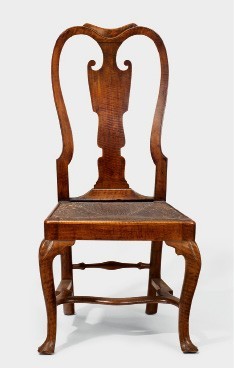

Side chair by William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1760. Maple. H. 41", W. 21 3/8", D. 20 3/4". (Courtesy, Dallas Auction Gallery.) This chair has Savery’s first label on the outside of the stay rail.

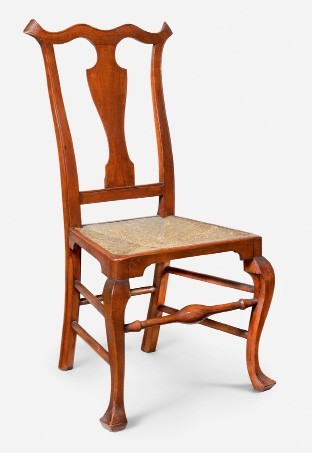

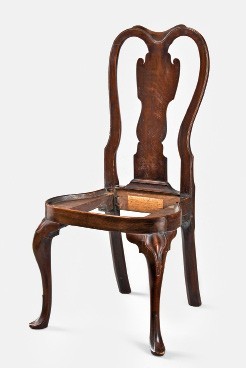

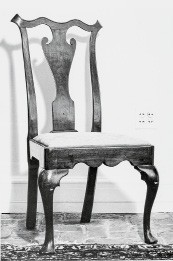

Side chair by William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1765. Maple. H. 41", W. 19 1/2", D. 15". (Courtesy, State Museum of Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.) This chair has Savery’s -second label on the outside of the stay rail.

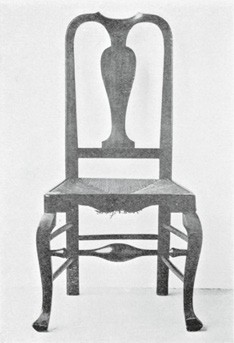

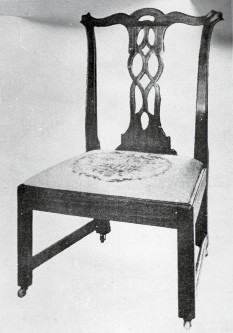

Side chair by William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1760–1770. Woods and dimensions not recorded. (From “A Chair by William Savery,” Bulletin of the Pennsylvania Museum 18, no. 74 [February 1923]: 3.) This chair has an unspecified label of William Savery on the outside of the stay rail.

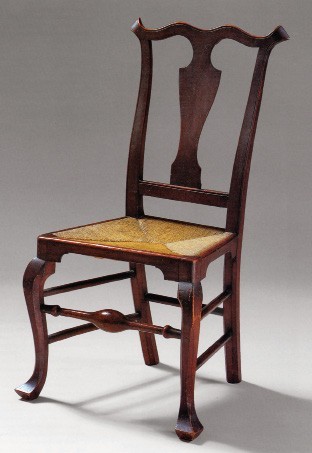

Side chair by William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1765. Maple. H. 36", W. 21", D. 18". (Courtesy, Bernard and S. Dean Levy, Inc.) This chair has Savery’s second label on the outside of the stay rail.

Side chair by William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1775. Maple with Atlantic white cedar. H. 40 1/8", W. 21 7/8", D. 19 3/4". (Courtesy, Dietrich American Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chair has Savery’s fifth label on the outside bottom of the rush seat.

Side chair by William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1770. Maple. H. 40 1/4". (Important Americana [New York: Sotheby’s, January 16–17, 1999], lot 765.) This chair has Savery’s third label on the outside of the stay rail.

Side chair attributed to William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1755–1770. Maple. H. 40", W. 22 1/4", D. 20". (Private collection; photo, Gavin -Ashworth.)

Side chair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1745–1765. Maple. H. 41", W. 21 1/4", D. 19". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Leg comparison of the chairs illustrated in figs. 7 and 8.

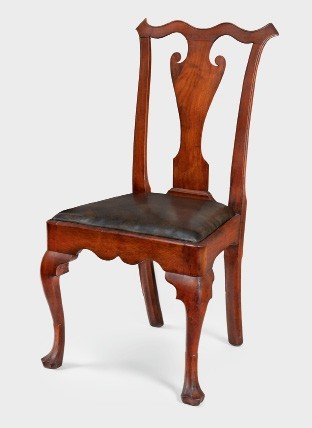

Armchair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1740–1750. Maple. H. 41 3/4", W. 25 1/2", D. 23 1/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) This chair has a splint seat.

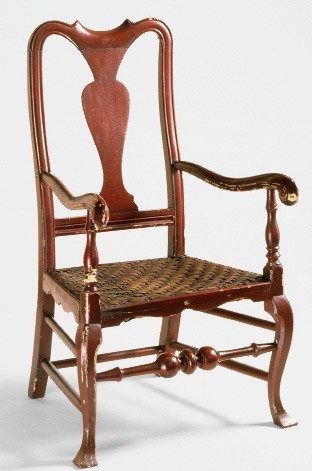

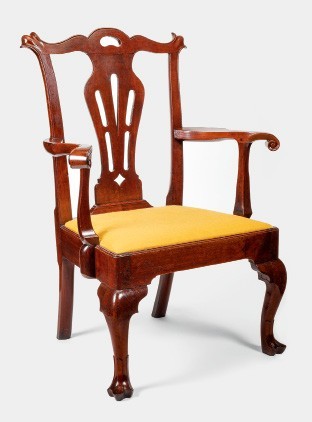

Armchair by William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1765. Maple. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Winterthur Decorative Arts Photographic Collection, 64.1766.) This chair has Savery’s second label on the outside of the second lowest slat (at arm level).

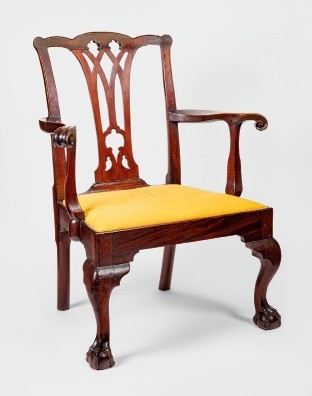

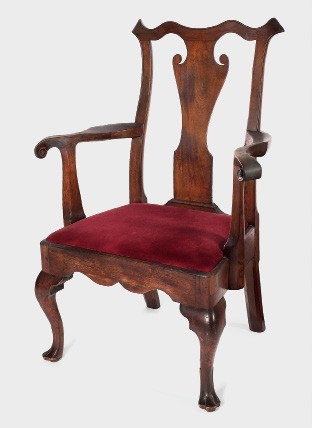

Armchair by William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1765. Maple. H. 39 1/4", W. 28 1/4", D. 22". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chair has Savery’s second label on the outside of the rear seat rail.

Side chair by William -Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1765. Walnut. H. 39", W. 21", D. 20 1/4". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg.) This chair has Savery’s second label on the outside of the rear seat rail.

Couch or daybed, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1745–1765. Walnut. H. 40 1/2", L. 77", W. 26". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art.)

Side chair attributed to Edward Wright, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1749. Walnut. H. 40", W. 19 3/4", D. 20 1/2". (Courtesy, Philip H. Bradley Co.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1745–1760. Maple. H. 42". (Courtesy, Christie’s.) This chair has a history of ownership in the Scattergood family.

Armchair by William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1765. Walnut. H. 42 1/2", W. 31", D. 21". (Courtesy, Brooklyn Museum.) This chair has Savery’s second label on the outside of the rear seat rail.

Side chair by William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1770. Woods and dimensions not recorded. (The James Curran Collection of Rare Eighteenth Century American Furniture [Philadelphia: March 11–12, 1940], lot 297.) This chair bears Savery’s third label, but its location is not specified.

Armchair by William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. 1770–1775. Walnut. H. 40", W. 29 1/4", D. 22 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) This chair has Savery’s fourth label on the inside of the rear seat rail.

Armchair by William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1780. Mahogany. H. 37 3/4", W. 30 1/2", D. 24 1/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) This chair has Savery’s seventh label on the inside of the rear seat rail.

Side chair by Thomas Tufft, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1773–1785. Mahogany. H. 38 3/4", W. 20 7/8", D. 23 3/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) This chair has Tufft’s label on the inside of the rear seat rail.

Side chair by William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1770. Woods and dimensions not recorded. (William M. Hornor Jr., “William Savery, Chairmaker and Joiner,” Antiquarian [July 1930]: 31.) This chair has Savery’s third label, but its location is not specified.

Side chair by William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1775. Walnut. H. 39". (Courtesy, Sack Family Archive, Yale University Art Gallery.) This chair has Savery’s fifth label on the inside of the rear rail.

Side chairs by William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1775. Walnut. H. 40", W. 21 3/8", D. 20". (Courtesy, Dallas Auction Gallery.) The left chair has Savery’s fifth label on the inside of the rear seat rail.

Side chair by William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1765–1780. Walnut. H. 39 1/2". (Courtesy, Sack Family Archive, Yale University Art Gallery.) This chair has the chalk inscription “Savery” on the slip seat. The seat has its original leather upholstery.

Detail showing the chalk inscription on the slip seat of the chair (left) illustrated in fig. 24.

Side chair attributed to William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1765–1780. Woods and dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Winterthur Decorative Arts Photographic Collection, 1976.815.) This chair has unidentified label fragments.

Side chair attributed to William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1765–1775. Walnut. H. 38 1/2", W. 20 1/2", D. 191/2". (Courtesy, Harriton House, Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania: photo, Gavin Ashworth).

Detail showing the shadow of a label on the rear rail of the chair illustrated in fig. 28. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Armchair attributed to William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1765–1775. Walnut. H. 411/8", W. 30", D. 211/2". (Courtesy, Pook and Pook.)

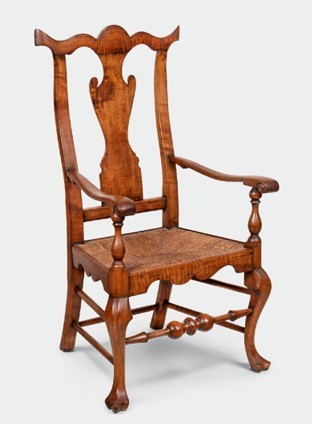

Rush-seat armchair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1750–1760. Maple. H. 44 5/8", W. 24", D. 171/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair by William Savery Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1780–1787. Walnut. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Winterthur Decorative Arts Photographic Collection, 76.1036.) This chair has Savery’s eighth label on the inside of the rear seat rail.

FEW EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY furniture makers rival the attention paid to William Savery over the past one hundred years. Such is the benefit of having been the user of the first furniture maker’s printed label, discovered and published in 1913. The level of enthusiasm for Savery and his work have been exceeded only by the unrestrained liberties taken with attributions and profiles of his artisanal life. In time, cooler heads and more reasonable arguments have tempered the claims to Savery’s ubiquitous authorship and hold on Philadelphia eighteenth-century furniture. Given this history, it is constructive to revisit his work.[1]

Because Savery labeled his work, a very large body of documented chairs and other furniture survives. Aggregated publications and easier access to images of objects create a rich landscape of new and old information. Of some thirty-one pieces of furniture bearing eight different Savery labels that may be assigned date ranges, eighteen are chairs. Another chair has the name “Savery” written in chalk on the underside of the slip seat, and others, one of which appears to have lost a label, can be added to the corpus with confidence. All of these chairs form an unparalleled body of historical evidence that allows furniture historians to explore furniture-making practices within a particular form, recognizing that comparisons between chairs and tables and case furniture offer few commonalities. Savery’s chairs embody design and construction relationships, including issues of innovation and persistence, as well as products representing different price ranges. On another level, these chairs allow the historian to explore and evaluate the long-term impact of attributions made decades and generations ago largely on the basis of presumed paths of descent in families for which verifiable evidence and other support is almost always missing. Asserted repeatedly over many years, some of these Savery associations exist today as “commonly accepted” truths of furniture history. Those assumptions need to be re-evaluated.[2]

Details of Savery’s life are sketchy at best. No record of his birth has come to light. At Savery’s death on May 27, 1787, a death record set his age at sixty-five, indicating that he was born between May 1721 and May 1722. The most important piece of evidence about his artisanal life is a 1741 note for £3.18 from John Wister that Savery signed “for the use of My Master Salomon Fussel & me,” thereby establishing his apprenticeship with the Philadelphia turner and slat-back chair maker Solomon Fussell (1704–1762).[3]

Rush-seat Chairs

Although Savery certainly made chairs throughout the 1740s and early 1750s, the earliest seating that can be firmly documented to him is a rush-seat side chair bearing the first of eight labels that he used over the course of his forty-five-year career (fig. 1). The history of furniture labels in America argues persuasively that this chair was not made before the late 1750s, the earliest datable label use anywhere in the thirteen colonies. To suggest that Savery’s first label dates earlier requires that he be profiled as an innovator and trend setter. The prudent and reasonable historian cannot assume the young maker of turned chairs initiated this marketing technique some fifteen years before any other American furniture makers, because his life and documented furniture reveal that he was not particularly inventive. Despite the date of his earliest label, the chair illustrated in figure 1 looks earlier; its yoked crest with rounded shoulders, vasiform splat, and sawn cabriole legs with unarticulated feet are details that emerged in the colonies during the 1730s. Only the swelled front stretcher expresses an updating from ring-and-ball or tripartite turnings that occur on some chairs of this general type. Balancing evidence of style with the label, furniture historians have commonly dated these Savery chairs between 1742 and 1750 or soon thereafter, a range that marks the time when Savery entered the furniture trade following his apprenticeship and established himself. However, no written evidence exists to describe the circumstances of his early employment, whether he worked initially as a journeyman or pieceworker employed by someone else, or worked on his own, which would assume his financial ability to acquire and operate a shop. By 1750, when he described himself in a newspaper advertisement for a lost fowling piece as “Chair-maker in Second Street,” he was established in the trade. He maintained that address throughout his career. In 1754 Philadelphia magistrates appointed him a tax collector for his ward, suggesting a level of prominence and responsibility within the community. [4]

Two other chairs essentially identical to that illustrated in figure 1 survive with Savery labels. One (fig. 2) is from a set of six and bears Savery’s second, mid-1760s label, glued onto the outside back of the stay rail (the horizontal bar below the splat). The other chair (fig. 3), also labeled on the back of the stay rail, was featured in a 1923 Pennsylvania Museum Bulletin article that identified Addison H. Savery, a descendent of the chair maker, as the owner. Consequential for furniture historians, that provenance had no meaningful tie to the maker; instead, it distorted an obvious route to identifying the maker. Fortunately, Addison Savery detailed the history of the chair in the next issue of the Bulletin. His father acquired the chair and its mate in 1889 from a descendant of the original Philadelphia owner. That descendant, unrelated to Savery, wanted the chairs to go into the maker’s family. Thus, the fact that William Savery made the pair of Addison chairs was completely independent of its richly suggestive early twentieth-century provenance. Information such as this—so easily lost or forgotten, or muddled—materially affects furniture history that relies substantially on provenance. Although the Bulletin article carefully recorded the label text, the specific label cannot be identified positively without a photograph because the wording of Savery’s second through sixth labels was the same. The only distinctions among them lay in the typeface and decorative devices, called dingbats, that frame the text. The label may have been his second, given the close similarity of the chair to the example illustrated in figure 2.[5]

Three other rush-bottom chairs, two with subsequent labels, have slightly later features (figs. 4–6). Each chair has a wavy crest ending in projecting ears. Scratch-beads, made with a small hand-held scraping tool called a scratch stock, outline the crest and rear stiles. This decorative technique was used commonly throughout the furniture-making community in Philadelphia and its environs from the 1730s through the 1780s. The thin strips of wood, tacked through the rush-wrapped seat lists (or rungs) to suggest more substantial framing of the seat, have straight undercutting on the chairs shown in figures 5 and 6 rather than the opposed ogees seen on the earlier chairs (figs. 1–3). The two chairs with urn-shaped splats have ears that curve backward on the front face in an abbreviated version of more fully developed rolled ears on more substantial framed chairs. The chair illustrated in figure 4, with rounded projecting ears and retaining a rounded splat and double-ogee seat casings, stylistically falls in between. Its label, Savery’s second, groups it with the three earlier chairs in contrast to the urn-splat chairs that bear his third and fifth labels, dating from circa 1770 and circa 1775 respectively.[6]

The remarkable feature of all of these rush-seated chairs is how similar they look and how consistently they were made despite the passage of time. Their shared characteristics form a solid foundation for identifying Savery’s work. The resulting profile becomes more compelling when it is compared to other seemingly similar chairs that regularly carry Savery attributions but exhibit small but telling differences. Features shared among all Savery-labeled rush-seat chairs and different from work of his competitors include:

• The bead along the top of the stay rail is cut into the front face only. In some non-Savery chairs it is also cut into the top face of the stay rail forming a three-quarter round bead. Other non-Savery chairs have beads cut along the top and bottom edges of the front face of the stay rail.

• The sawn cabriole legs have lightly chamfered edges on the outward front arris or right-angled edge of the leg. The chamfer begins below the knee and ends above the foot. Some other leg chamfers begin at the seat rail and continue down the entire leg, ending just above the ankle.

• The chamfering of the rear legs reduces the squared corners, but the cut is not deep, resulting in a chamfer that is thinner than the flanking faces of the leg. Also, the leg stock is rectangular in cross-section before chamfering, not square.

• In chairs with vasiform (rather than urn) splats, the neck of the vase is high (near the crest rail) in Savery work. Also, the points of the yoke crest are higher than in many comparable non-Savery crests.

• Splat templates match among Savery chairs, establishing a precise and dependable means of identifying Savery work and distinguishing it from the work of other shops.[7]

Comparison of these traits to anonymous chairs of similar appearance produces instructive results. The side chair illustrated in figure 7 has a quatrefoil piercing in the splat that is delightful on the one hand but without any known counterparts on the other. Examination of the chair, however, readily identifies it as a Savery product: all of the small details conform, and the splat is identical to those on labeled examples.

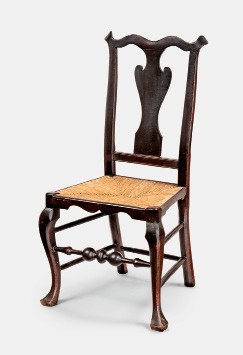

The side chair shown in figure 8 looks similar at first glance, but its differences are legion. The stay rail bead is cut into the front and top surfaces, and the front leg chamfer runs down from the seat rail rather than from just below the knee. The neck of the splat vase is long (indicating use of a different splat template), and the points of the crest yoke are lower and farther apart. Although not apparent in the image, the rear leg cross-section is a square rather than a rectangular octagon. With the comparative inventory in hand, other differences become more readily apparent. The rear legs are shaved in front at the bottom, producing a backward rake or “kick” in the manner of many New England chairs, and comparison of the front legs to Savery legs reveals that those have less curvature and are of more uniform thickness (fig. 9).

Features on the chair illustrated in figure 7 call to mind another example that Benno Forman linked to Savery in his influential essay “The Fussell-Savery Connection,” the first to study Fussell in any detail. Forman raised an armchair (fig. 10) from obscurity in the Winterthur collection, perceptively noting its many Philadelphia features. He identified several departures from the labeled Savery chair shown in figure 1, namely the splat shape, the treatment of the stay rail, rear legs without chamfers, and raked rear feet, yet still declared that “all of the details of its design indicate that it originated in the shop of William Savery.” Following that logic, the chair illustrated in figure 8 could also have come from Savery’s shop, and by extension, many—perhaps most—other variant chairs made in Philadelphia. Forman’s acceptance of relatively broad degrees of difference seems tied to his small sample of chairs. In contrast to the rich details he found in the Fussell ledger, he acknowledged the absence of documented Fussell chairs. Using price information, he argued persuasively that a side chair identified by William Macpherson Hornor as that listed by Fussell in his 1748 account with Benjamin Franklin was erroneous: the price of 11s. 6d. for each of “3 best Crookt feet Chairs” was too low by comparison for such walnut chairs. Without any documented Fussell chairs, Forman theorized that one could start with Savery chairs and, using the Fussell-Savery master-apprentice relationship, work backward to discover Fussell’s products. Accordingly, he selected chairs for consideration, determined his own criteria, and then looked for differences to identify Fussell’s work. Perhaps he should have looked for similarities across a much broader sample of Philadelphia rush-bottom chairs.[8]

Although the historical record highlights only Savery chairs because of surviving labeled examples and Fussell’s work by his ledger spanning 1738 to 1751, they were not the only makers of inexpensive seating in mid-eighteenth-century Philadelphia. Forman used Fussell’s ledger to probe the larger community of makers of inexpensive chairs by naming several individuals who supplied him with chair parts at various times, but he named only William Davis and Hugh O’Neal as “competitors.” Names unearthed by Hornor in his discussion of rush-seat chairs creates a formidable list. All told, the numbers of anonymous chairs that survive and the many possible makers cause the task of linking one to the other to be complex and fraught with uncertainty. Accordingly, the furniture historian must proceed carefully, use the surest evidence, and minimize speculation and assumptions.[9]

That rush-seat chair makers made splat-back chairs with cabriole legs in addition to cheaper slat-back turned chairs is an assumption, but one based on affirming evidence. Different chair descriptions and values in Fussell’s ledger indicate that he made a variety of products. More directly, a Savery label on a turned slat-back armchair, known only by photographs, confirms his fabrication of this less-expensive form (fig. 11). It is the only known turned chair bearing his label. Even though the feet were cut and rockers added at a later date, this chair is an important document. The label, his second, is the same as on two of the splat-back rush-seat chairs, establishing that Savery made both seating forms at the same time. When he died in 1787, his estate inventory of July 20 recorded dozens of three- and four-slat back chairs, indicating he made them throughout his entire career. More than any other surviving chair, this labeled slat-back example embodies Savery’s apprenticeship training under Fussell and may be an effective link. In evaluating undocumented chairs that scholars have associated with Fussell or Savery, it is surprising that none has arm-support turnings like this chair, nor is this chair referenced anywhere except in Hornor’s original publication of it. Also of note, the arched slats are not undercut, representing an aesthetically less desirable design.[10]

Framed Chairs

Framed chairs represented a chair-making venture that was appreciably different from making rush-seat chairs; the added work and finer materials required for the former resulted in a cost per chair that was typically triple or more that of the latter. Everywhere on the framed chair, mortise-and-tenon joints held parts together instead of quicker shaved or turned rounds secured in drilled sockets. Carving in the round replaced two-dimensional sawn profiles, and slip seats consumed better and costlier materials than rush seats. Less obvious, the maker of framed chairs used different skills and tools, notably ignoring the lathe for the most part. In Savery’s case, he first acknowledged these differences many years after entering the trade as a turned chair maker in about 1742. In 1750, his first public notice, he was “William Savery, Chair-maker in Second Street.” Similarly, in his first label, he described himself as a maker of “All Sorts of Rush Bottom CHAIRS.” Only in his second label did he advertise “All Sorts of Chairs and Joiners Work,” still located at “the Sign of the Chair” on Second Street near the Market.

A maple armchair and walnut side chair stand out as being Savery’s earlier framed products (figs. 12 and 13). Each may be dated in the mid-1760s by use of his second label, which identifies the largest group of his documented furniture. Seven of the eight objects in the group are chairs, the eighth being a walnut slant-lid desk, which is the earliest documented example of Savery’s cabinetry. These two chairs offer evidence of their early place in Savery’s evolving career. Whereas the joinery and other aspects of working the wood are the same as that of other craftsmen, placement of the labels on the outside of the rear rail is revealing. Anyone familiar with eighteenth-century chair-maker labels knows they are almost always found inside the rear rail. However, those examples—which include the Philadelphia labels of Benjamin Randolph, James Gillingham, and Thomas Tufft—are chronologically later. Savery faced a label-placement question for which there were no local practices to follow. Consequently, he simply continued to do what he had done with his earliest chair-labeling; he glued the label onto the outside back of the seat rail, the nearest counterpart to the stay rail. A compass-seat armchair, discussed below, also bears a Savery label on the outside, but he shifted placement to the inside of the rear rail in his subsequent chairs.[11]

The armchair and side chair display many similarities. They have wavy crest rails ending in rounded ears, like the similarly labeled chair illustrated in figure 4. The stiles curve gently front to back, the front rails have double-ogee undercutting, and the rear legs are chamfered as in the rush-seat chairs. These two framed chairs have horizontally shaped H-stretchers, no rear stretchers, side-rail tenons that do not extend through the rear stiles, and front legs that end in similar paneled feet. The urn splat in the armchair resembles that used in the rush-seat side chairs except for its larger scale, in keeping with the larger overall dimensions of the chair. The eared splat of the side chair is Savery’s earliest surviving venture into more expressive and stylish splat designs.

Another notable decoration on the side chair is the lambrequin (also called an intaglio) carved into the knees—a feature associated with Savery’s work from the earliest publications to the present, with first mention appearing in a 1925 article in the Philadelphia Museum Bulletin. Samuel Woodhouse updated readers about ongoing Savery research and featured photographs of a dressing table and the knee lambrequin. On one of two such tables “believed in the family to have been made by William Savery for use in his own household,” Woodhouse identified the unusual knee ornamentation as “the creation of one craftsman, and hence . . . [indicative of] the production of William Savery.” In 1935 Hornor gently reinforced this particular association in the Blue Book when discussing a daybed being “altogether possible” by him based on family ownership and patronage as well as “that craftsman’s characteristic workmanship,” namely the lambrequin (fig. 14). Albert Sack attributed an easy chair to Savery because it showed “the lamb’s tongue or intaglio knee carving favored by [him].” More recently, Alexandra Kirtley informed readers that Savery “incorporated the same carved design in low relief on the knees of his furniture.” When Morrison Heckscher described similarly decorated chairs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, he described lambrequins as “a motif found on several pieces of furniture labeled by or otherwise documented to William Savery.” Yet he cautioned that attribution was not warranted because the particular shapes of the lambrequin and feet on the chairs in question did not conform to other Savery furniture. Another chair of the same set subsequently came to light with an early owner’s label pasted onto the inside of the rear rail stating that it was made by Edward Wright of Philadelphia in 1749 (fig. 15).[12]

Despite broad repetition and reinforcement throughout early American furniture publications and the marketplace regarding lambrequins, historical evidence does not support their use to determine Savery’s authorship. First, the side chair illustrated in figure 13 is the only example among his thirty-odd pieces of labeled furniture to incorporate a lambrequin, calling into question how representative that detail is. Other lambrequin examples “documented” to Savery by histories of ownership are mired in attribution uncertainties and represent circular reasoning. Second, the many lambrequins used on furniture attributed to Savery range widely in their shapes and execution, as Heckscher observed. That on the labeled side chair exhibits ogee-curved sides. The lambrequin on the daybed (fig. 14) has sides that essentially form a triangle with the seat rails. The feet and knee brackets also differ from those on labeled Savery furniture. The lambrequin sides of the so-called Scattergood chairs have a curve that does not reverse, forming an ovoid motif (fig. 16). The several other lambrequin variations merely introduce more confusion. Third and finally, written evidence, combined with the dating of Savery’s labels, argues that he did not make case furniture of any kind before the mid-1760s, when he made a desk. He especially did not make any complex or refined cabinetry, as are the early-styled dressing tables that originated the lambrequin narrative, until the 1770s, when he began labeling dressing tables, a high chest of drawers, chests of drawers, and other case furniture.[13]

Savery displayed his nascent skills as a maker of joined or framed chairs in another 1760s chair, also labeled on the outside of the rear seat rail (fig. 17). The compass-seat, three-shell, walnut armchair exhibits all the features of fine Philadelphia mid-eighteenth-century chairs—a far departure from Savery’s contemporaneous rush-seat products. Its fabrication conforms to standard practices evident in these ambitious chairs, demonstrating that Savery was fully conversant with these other practices. The curvaceous rear stiles have laminated pieces on the insides below the arms to save wood. That said, he departed from usual practices in also laminating the tops of the stiles in the back where they join the crest and at the base of the splat in the rear where it curves before entering the shoe. Both of these uncommon lamination sites add wood to boards that were originally not thick enough to accommodate curves in the chair. Each instance may represent an error in laying out how the parts were cut, something Savery doubtless corrected in time if he attempted such a chair form again. The front legs are round-tenoned into the seat rails. The applied moldings holding the slip seat are cut from the same walnut boards as the slip seat itself, the rear rail of which is hard pine. In contrast to the chairs illustrated in figures 12 and 13, this example has through-tenons in the back, including the small rear brackets below the seat rails. The handsome carved shells, volutes, and deep beaded edges of the crest are the equal of those found on other Philadelphia seating. Given the specialized skills required and the absence of carving tools in Savery’s estate inventory, he likely hired someone else to do the work. The toes of the trifid feet are replacements that continue the three panels around the ankle. They project far enough forward to form a real, if somewhat rudimentary, trifid foot, in contrast to the nearly round paneled feet of the chairs shown in figures 12 and 13. Any uncertainty resulting from the undocumented foot restoration, completed in 1923, is reduced by similarly projecting toes on subsequent Savery chairs (see figs. 18 and 19). Another significant improvement in the compass armchair lies in the arm support. It has an organic, lamb’s-tongue shape with a modulated edge—an outlining concept that recurs in the arm itself and the side seat rails. At the bottom, the arm support ends in a rounded element attached to the seat rail. It looks elegant compared to the simple columnar support of the chair illustrated in figure 12, which terminates in an angular and discordant rectangular block.[14]

Having established his credentials making formal seating with the compass-seat armchair, Savery made a range of seating over the next twenty years before his death. Among his offerings addressed below, he continued to produce rush-seat chairs that were identical to those of the 1760s, including the chair shown in figure 5 and bearing a label dated in the mid-1770s, as well as the dozens of slat-back chairs listed in his shop inventory at his death. Notable too, the variety in the chairs he made was amplified by diverse case pieces and at least one tea table. Unlike Solomon Fussell, who spent a career working within relatively narrow product boundaries, Savery continued to expand his offerings, although always calling himself a chair maker and joiner.

A side chair and an armchair that appear to be from the same set have Savery’s third and fourth labels respectively (figs. 18 and 19), a circumstance in contrast to the American practice of labeling only a single chair within a set. Salient characteristics that suggest this side and armchair are from the same set include the splat design and bowed opening in the crest rail. Smaller details such as the stepped molding cut into the tops of the seat rails, the visible joint pins, use of a scratch-bead on the outer edge of the stiles and crest, and paired notches cut into the ears are also the same. The side chair, known only by a photograph, follows every discernable feature, although some construction details, such as visible plane marks on the insides of the seat rails and pinning patterns at each joint, cannot be compared.

Comparison of this set of chairs, represented by the armchair, to earlier Savery seating reveals commonalities and evolutions. Of the former, the feet look the same as those on the compass-seat armchair (figure 17), and both chairs have through-tenons. The compass-seat armchair also conforms in the use of a scratch-bead to outline the chair back (except where the bead lies above the surface in the crest rail). However, this practice was widespread among chair makers throughout the Philadelphia region and, accordingly, does not isolate Savery’s chairs from those of other makers. Notable changes in the armchair illustrated in figure 19 occur in the rear legs, in which the octagonal chamfers are fully rounded, leaving a flat face only on the sides of the legs. The shapes of the arm and arm support recall those of the compass-seat armchair shown in figure 17, but each has been simplified. Like the armchair in figure 12, volutes on the handholds of the example shown in figure 19 are recessed and visible from the front of the chair only. The seat rails on the latter chair are substantial pieces of wood—the walnut rear rail is one and one-quarter inches thick, and side rails are almost a full inch thick. These large rails likely gave the joiner confidence that a large armchair without stretchers would not fail in use. Savery’s confidence was such that he refrained from using corner blocks to reinforce the frame.[15]

Some ten or more years later, Savery applied his seventh label to a mahogany armchair with a pierced gothic-style splat and cabriole legs with claw-and-ball feet (fig. 20). This chair is slightly shorter and broader than the other armchair (fig. 19), an acknowledgment of changes in proportion in stylish seating. The seat rails of each are four inches tall. Those on the later, mahogany armchair are undercut in the sides as well as the front, which reduces the more massive appearance of the earlier Winterthur armchair that has uncut side rails. Moreover, the undercutting of the later armchair removed one-quarter inch more wood, further reducing the weighty appearance of the deep rails. Structurally, Savery made the later seat rails thinner and installed corner blocks.

The similarly shaped arms stand on identical supports. The later arms lack an outer scratch-bead, and the handholds are carved into three lobes. Little should be deduced from this latter feature because it also appears on the earlier compass-seat armchair. Thus, it may be considered a bit of carved detail that was added or not, depending upon circumstances, and not a sign of evolving practices. Similarly, small details like the absence of any molded decoration on the top edge of the seat rails represents another option. The splat and crest rail design recalls many other chairs from Philadelphia and the broader region. The rounded ears of the crest rail may, at first glance, suggest influence of Philadelphia furniture maker Thomas Tufft (ca. 1738–1788), who acquired his own shop in 1773 and whom Savery doubtless knew; but the visual relationship to Tufft’s labeled and richly carved side chair is not exclusive (fig. 21). Several other contemporary chairs exist with very similar designs.[16]

The labeled side chair illustrated in figure 22, published by Hornor in 1930 but not seen since, exhibits obvious condition issues but still reveals much about Savery’s chair-making capabilities midway in his career. The narrow, interlaced splat is a fragment of its original form. Wide straps at each side of the middle section are missing. Breaks and losses were sometimes repaired by removing symmetrical elements and then shaving uneven ends, a solution that was likely used here. Mental restoration of those outer straps produces a splat design that was common in England, known in New York and Boston, and represented by a small group of chairs in Charleston, but otherwise unknown (or very rare) in Philadelphia. In comparison to the other renderings, Savery’s splat displays some distortions and omits piercings near the bottom, creating what was probably a distinctive and early version in American seating based on dating of the label. The unusual bowed piercing in the crest rail replicates that of the chairs shown in figures 18 and 19, although the ears appear not to have notches. A scratch-bead outlines the back. The legs have lost some height, probably about equal to the height of the later casters, and a medial stretcher connecting the side stretchers is missing. The image does not reveal a rear stretcher; those were standard, although the Savery chairs illustrated in figures 12 and 13, made a few years earlier, do not have one. The earliest piece of Philadelphia furniture with Marlborough legs that can be documented to a year is an armchair by Benjamin Randolph dated 1762 or 1765, depending upon how the chalk inscription is read. Based on the probable label date, the Savery chair follows by just a few years. It is the only known Savery-labeled piece of furniture with Marlborough legs.[17]

A cabriole-leg side chair with fluted stiles and four carved shells has Savery’s mid-1770s fifth label glued onto the inside of the rear rail—the customary location (fig. 23). Like the armchair illustrated in figure 19, it has through-tenons and rounded rear legs with flat sides (rather than octagonal cross-sections). When compared to Savery’s other seating, it looks fully decorated, even ambitious, but not so in the larger context of fine contemporaneous Philadelphia seating. The several shells, and probably the feet, likely surpassed Savery’s carving abilities, requiring him to hire a carver’s services. As advertised by Israel Sack, Inc., in the 1990s, this chair was dated 1755–1770, a range that conforms to general stylistic dating, yet the label attests to its later time of origin, about 1775. That same label appears on the walnut chair shown on the left in figure 24, one of a pair. It seems far closer in spirit, and therefore date of manufacture, to the chair illustrated in figure 13 than it does to the strapwork-splat chair or to other more recent chairs. These solid-splat chairs (figs. 24, 13) have scratch-beads outlining the chair backs, decorative undercutting on the front rail only, the same knee bracket outlines, and similar front feet. The crest-rail ears on the chairs shown in figure 24 appear to be a modest updating, as is the elimination of stretchers, the use of through-tenons, and the appearance of a more prominent middle toe forming a rudimentary trifid foot.

A key difference from the stretchered, solid-splat chair (fig. 13) lies in the splat, which was made with a different template. The later chair splats (fig. 24) measure roughly one-half inch wider across four different locations, although each measurement varies from another, showing that the old pattern was not merely widened but was recut. Vertical measurements within the splat shape are nearly the same, but the overall measurement differs because of changes in the height of the rectangular block at the bottom. Given Savery’s use of a template in the rush-seat chairs, why this disparity in two chairs that otherwise look so similar? Although very few eighteenth-century templates survive, manuscripts refer to “patterns,” sometimes giving them monetary values in estate inventories, and thus document their use independent from direct observations of the chairs. Surviving templates, notably among tools of the Dominy craftsmen of Long Island, are thin pieces of wood that guided the furniture maker’s simple metal scriber as he pressed it into the wood he wished to cut. Alternatively, cabinetmaker John Janvier owned and cabinetmaker John Janvier had “1 ps [piece] parchment & Chair patterns” valued at three shillings in 1801, suggesting that some patterns were made of parchment. If a template split or was damaged for some reason, it was readily replaced. Savery, being very familiar with the shape he desired, replicated his splat template from memory, causing minor and inevitable variations from the original. The result was so like the earlier ones that perhaps even he could not distinguish between the two even though the patterns were not exact matches. Of interest, he subconsciously responded to the same evolutionary changes in chair design expressed in the two Winterthur armchairs in figures 19 and 20 by making the template slightly wider.[18]

Given the lengthy time span of the simple, solid-splat chair design, a similar chair inscribed “Savery” in chalk on the slip seat covered in original leather offers an engaging challenge regarding its chronological placement in Savery’s career (figs. 24 and 25). The chalk name was likely written by an upholsterer to identify the owner (and maker in this instance) of a set of slip seats delivered to him to be covered (in leather in this instance). The chair, known only by the image, follows the Savery model very precisely, although checking it for use of the same splat template would reinforce evidence of the name. Using evidence of Savery’s labeled chairs, this chair probably belongs at the earlier end of the chronological spectrum because of the double-ogee front rail decoration, the chamfered rear legs (not rounded on the front and back faces), and the shape of the front feet, which do not exhibit the stronger middle toes. This chair appears not to have a scratch-bead outlining the back. Savery’s early framed chairs did not have through-tenons, but that feature is unknown in this example.

Another nearly identical chair, different from the chalk-inscribed example only in having the usual scratch-bead, is again known only by a photograph (fig. 27). An accompanying written note states, “There is a trace of a label on the splat, but it is not identifiable.” A lack of label fragment photographs seriously undermines further evaluation. However, the chair appears identical to other labeled Savery chairs and can be included in the corpus of his work pending examination of label fragments. A fifth chair, made with the same splat template as the early labeled chair illustrated in figure 13 and sharing almost all other details, retains the ghost of a label on the inside of the rear seat rail (figs. 28 and 29). Although all label vestiges are now gone, the shape measures the same 1 1/2" x 1 3/4" dimensions of most Savery labels. It joins the four similar walnut solid-splat side chairs to create a recognizable Savery chair-type. This large grouping brings to mind his many maple rush-seat chairs comprised of both labeled and identical unlabeled examples. Each highly specific chair grouping argues persuasively that Savery practiced observable and measurable consistency in his work, even though he was very capable of producing new and different furniture designs.[19]

An unlabeled armchair (fig. 30) has no known history, but its physical features tie it to Savery with reasonable certainty. The crest rail, splat, and front legs look like other Savery chairs, but such imprecise similarities are not sufficient for reliable attribution. The furniture historian, delving deeper, sees the double-ogee shaped front rail combined with side rails that are not undercut—the same pattern used for the side chair illustrated in figure 1. The seat rails are four inches deep, as on two armchairs (figs. 19 and 20). The rear legs are octagonal and have through-tenons, as do the compass-seat and Harriton chairs (figs. 17, 28). Other details, such as the feet, which have three projecting narrow vertical panels and rudimentary middle toes, also fit into the range of documented Savery features. At first glance, the splat looks larger (as is appropriate for the larger dimensions of an armchair), and therefore unlike documented examples, but in fact it yields the strongest physical evidence of Savery’s manufacture. The curved outline of the sides exactly matches the template used for the chairs shown in figures 13 and 28, although the splat width is a half inch greater. Thus, to create a larger armchair splat, Savery outlined one side with his side chair template, slid the pattern the requisite half inch toward the opposite side, then scribed that remaining side. He extended the rectangular base about one and one-half inches to fit into the taller dimensions of the back. Because Savery widened the splat about one-half inch, approximately the same as his second version of this splat design (see fig. 24), the armchair probably was made earlier. One more physical feature of note is not as successful but again shows Savery’s thinking. The arm supports are shaped from a rectangular piece of wood that leaves two faces of unequal size on the inside-front of the supports. The two faces are equal, and more successful visually, on the later armchairs (figs. 19 and 20). As with his other armchairs, the arm support inserts into the upper molding of the side rails, rather than being contoured to fit around it, but the shape of the lower arm support merely extends the rounded outer side of the supports, reminiscent of the ungainly rectangular block on the armchair illustrated in figure 12. Savery also improved its shape on other armchairs (figs. 19 and 20).

As with the rush-seat chairs, Savery’s framed seating can be separated from other solid-splat versions that bear resemblances but differ in key ways and indicate fabrication by another craftsman. The so-called Scattergood family side chairs (fig. 16), a set of six made of vibrantly striped maple, have acquired strong Savery associations over the years. When first published in 1924, a Scattergood chair from that set carried no Savery associations, although the armchair pictured next to it in the article did (and has since been identified as of Baltimore origin), indicating active interest in Savery at that time. When other members of the set were published in 1936, William Savery was again not mentioned, although a detailed provenance listed Mary Savery (1800–1869) as the wife of the earliest recorded owner, namely Thomas F. Scattergood (1795–1876). The text did not reveal that she was William’s granddaughter. However, in 1959 antiques dealer David Stockwell sold a chair from the set as having been owned by William, and other dealers subsequently advertised other chairs from the set as made by Savery. Beliefs were strong when another chair from this set came to auction in 2002. The published catalogue description omitted “mistakenly” from a cited research report, thereby reversing its original intention: “some [dealers] have [mistakenly] identified this set of chairs as a Savery product.”[20]

Forman’s Fussell-Savery essay added more fuel to the Savery fire. Specifically, he attributed certain chairs, such as the armchair illustrated in figure 31, to Fussell, trusting his ability to “feel” the design despite some visible differences from the labeled Savery example shown in figure 1. In 1999 attribution of the mate to the armchair expanded to include Savery directly. Savery attributions in general have continued to cite knee lambrequins where present as a reason. In others, attraction to him seems to lie in figured maple and playful exaggerations in crest-rail ears, splats, or other features. Despite repeated assertions of Savery manufacture from several different sources, the body of his labeled chairs simply does not support these attributions. Savery did select attractively figured maple for some of his furniture, as can be seen in the splat of his earliest labeled chair and for an armchair (figs. 1, 12), but no other pieces of his labeled furniture exhibit notable grain patterns. He owned maple furniture at his death, but that did not translate into his preference for the wood in what he made. Putting aside the seven rush-seat maple chairs, only one of the other twenty-four pieces of labeled furniture (the armchair in figure 12) was made of maple. All of the rest were of walnut except for three of mahogany and one of an unknown wood. Even if Savery had favored maple, it is not a limiting factor in the complex Philadelphia furniture-making community. Similarly, visual surveys of his documented furniture do not yield design flights of fancy. Instead, his work looks unpretentious and conventional. The route to supportable Savery attributions lies in attention to the many details of his workmanship and the reasonable expectation of consistency in what he did.[21]

The last labeled chair to consider (fig. 32) balances new and recurring themes. The latter includes comment about the label. This single chair, again known only by photographs, bears the last of his eight labels. A notation accompanying photographs of the chair states that the partial Savery label is spurious, a conclusion almost certainly based on a mistaken 1934 article. In it, the author judged this printed label by comparing it to one of Savery’s several earlier and wholly different ones. Although the label is completely different—having only his name without a place of business or products—it is genuine and survives on at least two other pieces of furniture. It identifies this chair as one of Savery’s later creations.[22]

Besides obvious changes to the splat design, which displays a more complex outline than earlier designs, the entire chair embodies several updated features. Proportions, readily visible in the splat, are broader and stockier overall, in keeping with prevailing styles and reminiscent of the armchair illustrated in figure 20. The front feet end in the true trifid fashion of his later seating. (This foot-form never went out of style in eighteenth-century Philadelphia regional furniture.) Although the chair back retains an outlining scratch-bead, the crest rail embodies subtle changes. The former double serpentine line across the top now thickens in the top portion and thins toward the ears beyond a subtle point or node—an outline repeated on the outer sides of the central vase of the splat. The ears no longer simply roll backward but are scooped out in the center so that the top and bottom edges seem to unfold and open out. Again, like the armchair (fig. 20), the front and side rails have straight undercutting that removes much of the bulk of the frame, and double-ogee undercutting of the front rail is outmoded. The rounded rear legs appear to have lost all chamfered ridges or other vestiges of Savery’s earlier octagonal shaping.

Savery’s life as a craftsman was not exceptional, although the number of chairs labeled and otherwise firmly documented to him is. This generates an enlightening opportunity for furniture historians to dig deep into his career, chair-making practices, and products. Along the way, historians can gauge the accuracy of attribution strategies, especially those that rely upon only a few physical features. Historians can also evaluate the promises and pitfalls of provenance. Provenance may guide the historian when little other historical evidence survives, but the Savery chair story calls many of those findings into question, thereby reminding readers of the complexities and inherent uncertainties of ownership pathways through multiple generations. For much of Savery’s furniture, that strategy has produced weak or incorrect results. Savery chairs also remind the reader that no matter how often a particular historical finding may be repeated, better historical evidence may show it to be incorrect. Furniture historians may dispute the qualities of Savery’s aesthetic achievements, but his legacy is especially rich.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For their assistance with this article, the author thanks Carley Altenburger and Sarah Lewis, Tara Gleason Chicirda, Philip G. Correll and Ronald E. Magill, Bruce Cooper Gill, Joan Johnson, Alexandra A. Kirtley, Frank Levy, Eric Litke, Lisa Minardi, Jay Robert Stiefel, and also the late Joe Kindig, whose insights and reactions always improved my writing over the past decades.

Luke Vincent Lockwood, Colonial Furniture in America, 2 vols. (2nd ed.; New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1913), 1: 110.

Dating follows Philip D. Zimmerman, “Dating William Savery’s Furniture Labels and Implications for Furniture History,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite, (Haverton, Pa.: Casemate Publishers for the Chipstone Foundation, 2018), pp. 193–214.

A.W. Savary, Savary Family (Boston: Collins Press, 1893), p. 136. Benno M. Forman, “Delaware Valley ‘Crookt Foot’ and Slat-Back Chairs: The Fussell-Savery Connection,” Winterthur Portfolio 15, no. 1 (Spring 1980): 46; ibid., pp. 41–64.

Philip D. Zimmerman, “Early American Furniture Makers’ Marks,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Easthampton, Mass: Antique Collectors’ Club for the Chipstone Foundation, 2007), pp. 136–138. Pennsylvania Journal, November 1, 1750, as quoted in Alfred Coxe Prime, Arts & Crafts in Philadelphia, Maryland and South Carolina, 2 vols. (1933; reprint ed., New York: Da Capo, 1969), 1: 181. Savery sustained severe fire damage in 1772. See Zimmerman, “Dating Savery’s Labels,” pp. 201, 204. William Savery, “List of the Taxables of Chestnut, Middle, and South Wards, Philadelphia, 1754,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 14, no. 4 (January 1891): 414–415.

This chair and another from the set were lent to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. See “Tables and Chairs from the Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Mitchell Taradash,” Antiques 49, no. 6 (June 1946): 359. “A Chair by William Savery,” Bulletin of the Pennsylvania Museum 18, no. 74 (February 1923): 2–4. Addison H. Savery, “A Correction,” Bulletin of the Pennsylvania Museum 18, no. 75 (March 1923): 16.

For a scratch stock in use, see Philip D. Zimmerman, “Dating Dunlap-Style Side Chairs,” Antiques 157, no. 5 (May 2000): 798, 800, fig. 2. Zimmerman, “Dating Savery’s Labels,” p. 211. The chair appears to be part of the same set as Thomas Smith Hopkins and Walter Scott Cox, Colonial Furniture of West New Jersey (Haddonfield, N.J.: Historical Society of Haddonfield, 1936), pp. 76–77, pl. 36A.

For use of templates in eighteenth-century chair-making, see Philip D. Zimmerman, “Workmanship as Evidence: A Model for Object Study,” Winterthur Portfolio 16, no. 4 (Winter 1981): 290.

Forman, “Fussell-Savery Connection,” p. 62, fig. 20. William Macpherson Hornor Jr., Blue Book, Philadelphia Furniture: William Penn to George Washington (Philadelphia: By the author, 1935), pp. 194–95, pl. 316; Forman, “Fussell-Savery Connection,” p. 46. Hornor’s discredited attribution is repeated in Jack L. Lindsey, Worldly Goods: The Arts of Early Pennsylvania, 1680–1758 (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1999), p. 102, fig. 161.

Forman, “Fussell-Savery Connection, p. 46. Hornor, Blue Book, pp. 292–296.

William Macpherson Hornor Jr., “William Savery, Chairmaker and Joiner,” Bulletin of the Pennsylvania Museum 23, no. 118 (February 1928): 15, 17. Hornor excerpted the inventory without identifying it in William M. Hornor Jr., “William Savery, Chairmaker and Joiner,” Antiquarian (July 1930): 74, 86; and Blue Book, p. 295.

Owned by the Chester County Historical Society. See Zimmerman, “Dating Savery’s Labels,” pp. 207–208, fig. 22.

Samuel W. Woodhouse Jr., “Philadelphia Cabinet Makers,” Bulletin of the Pennsylvania Museum 20, no. 91 (January 1925): 62–63. Hornor, Blue Book, pl. 53. Albert Sack, The New Fine Points of Furniture: Early American–Good, Better, Best, Superior, Masterpiece (New York: Crown, 1993), p. 72. Alexandra Alevizatos Kirtley, American Furniture, 1650–1840: Highlights from the Philadelphia Museum of Art (New Haven, Conn.: Philadelphia Museum of Art in association with Yale University Press, 2020), p. 55. Morrison H. Heckscher, American Furniture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. II. Late Colonial Period: The Queen Anne and Chippendale Styles (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art/Random House, 1985), pp. 79–80; Alan Miller, “Flux in Design and Method in Early Eighteenth-Century Philadelphia Furniture,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Milwaukee, Wis.: Chipstone Foundation, 2014), fig. 48, n. 34.

Zimmerman, “Dating Savery’s Labels.”

Horace H. F. Jayne, “An American Gate-Leg Table,” Bulletin of the Pennsylvania Museum 18, no. 77 (May 1923): 14. The rear legs are also ended out.

It is listed as an identifying feature of Savery’s work in Philadelphia: Three Centuries of American Art (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1976), p. 51.

Carl M. Williams, “Thomas Tufft and his Furniture for Richard Edwards,” Antiques 54, no. 4 (October 1948): 246–47.

Compare splat designs in John T. Kirk, American Furniture and the British Tradition to 1830 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1982), figs. 898–906; Bradford L. Rauschenberg and John Bivins Jr., The Furniture of Charleston, 1680–1820, 3 vols. (Old Salem, N.C.: Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, 2003), 1: 377–380. Important American Furniture: The Contents of Langdon (New York: Sotheby’s, January 26–February 1, 1985), lot 1156.

Joiner Robert Walker of Philadelphia owned “a Number of Patterns” valued at 1s. 6p. in 1774: Nancy Ann Goyne, “Furniture Craftsmen in Philadelphia, 1760–1780: Their Role in a Mercantile Society” (master’s thesis, University of Delaware, 1963), p. 212. Charles F. Hummel, With Hammer in Hand: The Dominy Craftsmen of East Hampton, New York (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia for the Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, 1968), pp. 96–98. Harold B. Hancock, “Furniture Craftsmen in Delaware Records,” in Winterthur Portfolio 9, edited by Ian M. G. Quimby (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1974), p. 205.

Winterthur Decorative Arts Photographic Collection, 1976.0815. Another photograph of an applied plaque identifies the chair as once owned by Juliana Randolph Wood (1810–1885). Charles L. Venable reported similar label evidence on a maple armchair that displays several Savery features, although the residue dimensions of 1 1/2" by 2 1/4" do not conform to the nearly square Savery labels. See American Furniture in the Bybee Collection (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1989), pp. 42–43.

Homer Eaton Keyes, “Some Pennsylvania Furniture,” Antiques 5, no. 5 (May 1924): 224; Joseph Downs, American Furniture: Queen Anne and Chippendale Periods (1952; reprint, New York: Viking Press, 1967), no. 53. Hopkins and Cox, Colonial Furniture, pp. 70–71, pl. 33. Philip D. Zimmerman, research report to Mrs. Lammot du Pont Copeland, February 1, 1996. Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Lammot du Pont Copeland (New York: Sotheby’s, January 19, 2002), lot 259. The catalogue identifies the Scattergood chair as “probably southern New Jersey,” which undermines a Savery attribution. H and R Sandor advertisement, Antiques 88, no. 6 (December 1965): 743; Joseph Sprain advertisement, Antiques 110, no. 4 (October 1976): 611.

Forman, “Fussell-Savery Connection,” pp. 48, 55, figs. 2, 10. Lindsey, Worldly Goods, p. 98, fig. 150. The author states that Fussell and Savery “expanded the market for inexpensive versions of these chairs, leading to their marketing as venture cargo . . . ,” for which there is no evidence cited or known.

Winterthur Decorative Arts Photographic Collection, 1976.1036. The chair was once owned by Neva Goodley Hoopes (1875–1947). “Spurious Labels Now in Circulation,” American Collector 1, no. 3 (January 23, 1934): 1, 6. See Zimmerman, “Dating Savery’s Labels,” pp. 204–205.