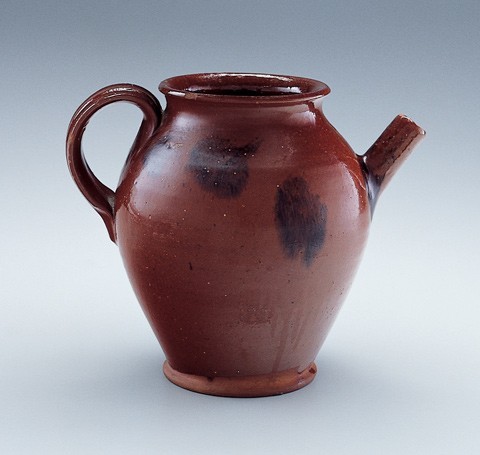

Jugs and flask, probably Huntington, New York, late eighteenth/ early nineteenth century. Manganese enriched lead-glazed earthenware. H. of tallest: 10 1/8". (All objects from the Anthony W. Butera, Jr. Collection; photos by Gavin Ashworth unless otherwise noted.) The attribution to Huntington is based on a jug that descended in a Huntington family. These objects are thought to date from the 1780s when Jonathan Titus owned the property until it sold on February 27, 1805. The lip on the flask matches the lips on the other two vessels. All three vessels were acquired locally. It should be noted that this kind of attribution is not foolproof; however, the importance of local knowledge and provenance becomes important when no other evidence is available.

Flasks, probably Huntington, New York, late eighteenth/early nineteenth century. Right: Manganese enriched lead-glazed earthenware. Left: Lead-glazed earthenware daubed with manganese oxide. H. of both: 7 1/8". The black-glazed flask fragment was discovered underneath the floor of a ca. 1810 house in Miller Place, Long Island. The lip of the flask is similar to several known Huntington vessels, including a straight-sided black manganese lead-glazed earthenware jar attributed to the Titus period in an early Huntington collection, and a rim waster found at the pottery site.

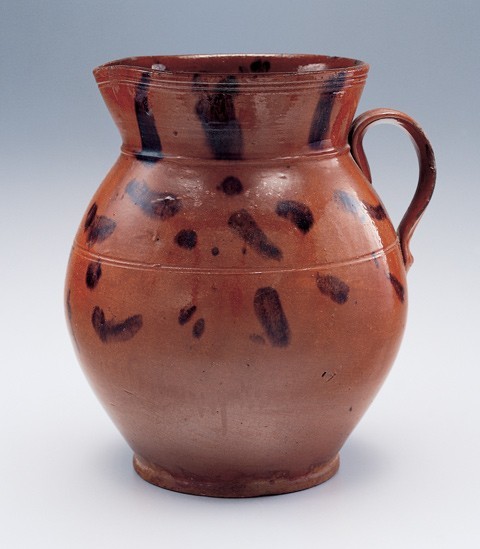

Mugs, probably Huntington, New York, 1805–1860. Lead-glazed earthenware daubed with manganese oxide. H. (left to right): 5 7/16", 6 1/2", and 3 15/16". This is a rare graduated group of tankards attributed to the Huntington pottery. The tankard on the far right came from a local source. The other two vessels did not, but both match the first almost perfectly. It is interesting to note the color difference which should not always be a guideline for attribution since the color of fired red earthenwares can be affected by conditions inside or outside the kiln, contaminants in the glaze, or different conditions of the clay source. The style of the extruded handles and their attachments has been found at the site of the Huntington pottery.

Mug fragment, probably Huntington, New York, 1805–1860. Lead-glazed earthenware daubed with manganese oxide. D. 3 1/2". This fragment of a tankard was found during the removal of a Victorian porch from a ca. 1680–1700 house in Mt. Sinai, Long Island. It is similar in all ways to the mugs illustrated in fig. 3. A similar tankard appears in the 1837 William Sydney Mount painting The Long Story.

Jugs and flask, probably Huntington, New York, 1805–1860. Lead-glazed earthenware daubed with manganese oxide. H. of tallest: 6 7/8". These three pots were purchased at auction from the Charles Embree Rockwell estate in Nissequogue, Smithtown, Long Island. This was a rare opportunity to purchase redware directly from a Long Island estate. The handle attachments are similar to the tankards illustrated in fig. 3. Also the same attachment of the handles on the jugs has been found at the pottery site. Although these examples are similar to wares produced at the Norwalk potteries, these pots have a local history and have been attributed to the Huntington pottery.

Porringers, possibly Huntington, New York, 1805–1860. Lead-glazed earthenware daubed with manganese oxide. H. 3 3/4" and 3 1/2". These two porringers are without any local provenance. However, identical handles have been found at the Huntington pottery site. Another example is in a local collection.

Syrup or oil jar, possibly Long Island, New York, ca. 1840. Lead-glazed earthenware daubed with manganese oxide. H. 8 1/2". Although this pot has a New England provenance, an identical extruded handle has been found at the Huntington pottery site. Two other pots of this form made in salt-glazed stoneware are known and are believed to be from the Hudson River Valley. The Huntington pottery shares a continuum with the Hudson River Valley potteries through the Caire and Brown families. Wet drug jars in continental tin-glazed earthenwares appear in this form.

Jar, attributed to Huntington, New York, 1805–1860. Lead-glazed earthenware daubed with manganese oxide. H. 8". This is a form traditionally attributed to Huntington.

Jar and lid, possibly Long Island, New York, 1805–1860. Lead-glazed earthenware daubed with manganese oxide. H. to top of lid. 10 5/8". Another variation on the form illustrated in fig. 8. It is possible that some of these pots were made in the Hudson River Valley, although there is no evidence yet to prove this.

Jar, possibly Long Island, New York, 1840–1860. Lead-glazed earthenware daubed with manganese oxide. H. 8 3/4". This jar descended in a Riverhead, Long Island, family and was found with a salt-glazed stoneware butter churn bearing the mark of Fredrick J. Caire Huntington who came to Huntington in the 1840s.

Jar, possibly Long Island, New York, 1805–1860. Lead-glazed earthenware daubed with manganese oxide. H. 8 1/2". This pot came from a collection formed on Long Island in the 1950s. It is slightly smaller than the jar illustrated in fig. 10, making the two pots look different at first glance. Further examination reveals similar features, and it is possible that they both were made by the same potter.

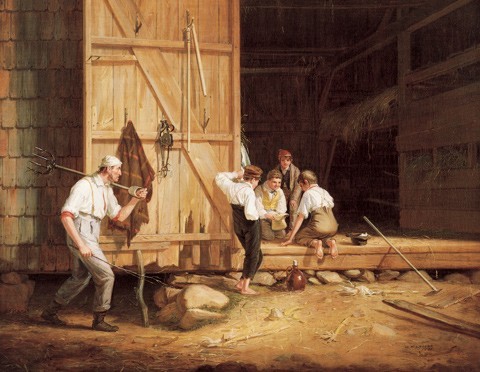

Jug, probably Long Island, New York, 1835–1860. Lead-glazed earthenware daubed with manganese oxide. H. 10". This handled jug comes from an early Setauket, Long Island, collection formed before 1950. A handled jug of this form appears in the painting illustrated in fig. 13. Traditionally, collectors of American pottery have believed that this form was produced later. This painting establishes an earlier date.

William Sydney Mount, Truant Gamblers (Undutiful Boys), 1835. Oil on canvas. 24" x 30". (Courtesy, New-York Historical Society, acc. no. 1858.)

Flask, probably Huntington, New York, 1835–1860. Lead-glazed earthenware daubed with manganese. H. 8". This flask has the same lip as the jug illustrated in fig. 12 . Although glaze should not always be used as a guideline for attribution, it sometimes helps when a group of wares are compared. This flask was found concealed in the wall of a house in the Port Jefferson area.

Jar, possibly Long Island, New York, 1805–1860. Lead-glazed earthenware daubed with manganese oxide. H. 9 1/2". This jar has a credible Long Island provenance.

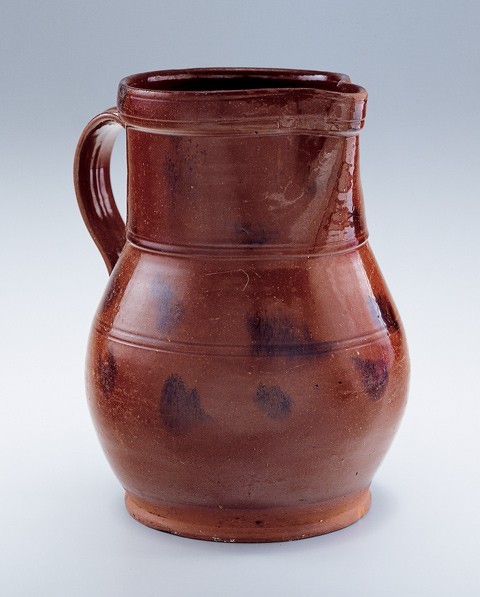

Pitcher, possibly Huntington, New York, 1805–1860. Lead-glazed earthenware daubed with manganese oxide. H. 9 1/2". The form, color, and decoration of this pitcher are similar to the jar illustrated in fig. 15. The pitcher’s extruded handle has been found at the pottery site.

Jar and lid, probably Long Island, New York, 1805–1860. Lead-glazed earthenware daubed with manganese oxide. H. to top of lid 10 1/2". This jar came from an early collection formed in Port Jefferson. It was found together with a straight-sided jar probably made by the same potter.

Pitcher, possibly Huntington, New York, 1805–1860. Lead-glazed earthenware daubed with manganese oxide. H. 10 1/8". This pitcher has been attributed to Huntington on the fact that this type of extruded handle and its attachment have been found at the pottery site. The belly of the pitcher also matches the belly of the pot in fig. 17, suggesting that the two were made by the same potter. Another pitcher of a different form, but with the same handle and attachment, appears in the painting illustrated in fig. 19.

Shepard Alonzo Mount, The Breakfast Call, 1852. Oil on canvas. 24" x 30". (Courtesy, Long Island Museum of American Art, History and Carriages; gift of Mr. and Mrs. Ward Melville, 1976.)

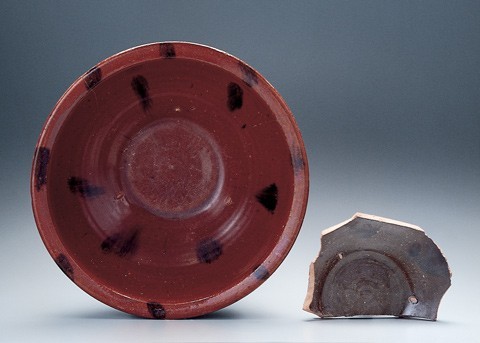

Bowl and archaeological fragment, Huntington, New York, 1805–1860. Lead-glazed earthenware daubed with manganese oxide. D. 13". Wasters of these bowls have been found at the pottery site. Matching rims have also been found along with the kiln furniture needed to stack the bowls in the kiln. Sherds of these bowls have also been found in Port Jefferson and Mt. Sinai, Long Island.

Bowl, Huntington, New York, 1805–1809. Lead-glazed earthenware daubed with manganese. D. 5 5/8". Two other examples of this form are owned by the Huntington Historical Society. This is a technically difficult form to produce. The small bowl has been thrown on a wheel, probably bisque fired, decorated, glazed on both sides then fired perhaps in a saggar. This form may be a tobacco dish, which is listed as one of the most expensive forms that Samuel J. Wetmore and Company produced ca. 1808–1809.

Dish, Huntington, New York, 1805–1860. Lead-glazed earthenware with slip decoration. D. 13 1/4". The slip decoration on this plate matches the cobalt blue decoration on a salt-glazed stoneware pot that descended in the Brown family and was probably made in Huntington before the Brown’s ownership. It is interesting to find a decorator who worked on stoneware and redware. Although the condition of this plate is poor, the large size and decoration are quite rare.

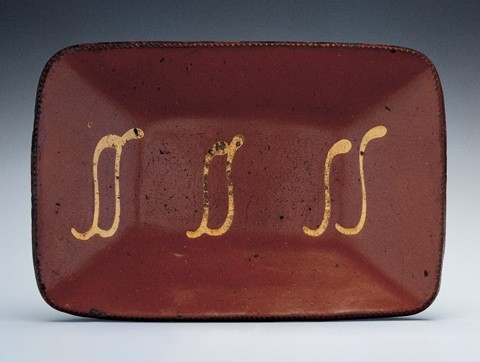

Loaf dish, Huntington, New York, 1805–1860. Lead-glazed earthenware with slip decoration. L. 14 3/8". This is another variation by the same decorator who ornamented the dish illustrated in fig. 22. The central curvilinear design occurs in cobalt on salt-glazed stoneware from the pottery site. The feather type design on the top and bottom of the loaf dish have been found at the pottery site in slipware and cobalt blue salt-glazed stoneware. A signed F. Caire Huntington stoneware jug in a private collection has a similar design. This loaf dish was recently discovered in a barn on Long Island.

Loaf dish, Huntington, New York, 1805–1860. Slip-decorated lead-glazed earthenware. L. 11 3/16". This loaf dish is decorated by the same skilled decorator who applied the slip on the dishes illustrated in figs. 22 and 23. Much practice is needed to execute these designs, as the slip tends to clog and has to be mixed frequently.

Loaf dish, Huntington, New York, ca. 1840–1860. Lead-glazed earthenware with slip decoration. L. 11 1/2". This stamped pattern was found at the pottery site.

Demonstration by Greg Shooner of the stamping techniques used to decorate Huntington redware. (Photo, Anthony W. Butera, Jr.) This tin stamp was fashioned during the annual ceramics conference at Eastfield Village. Here the stamp is being dipped into white slip.

A series of stampings applied to a red clay slab illustrating the speed and repetitive nature of this method of slip decorating. (Photo, Anthony W. Butera, Jr.)

Border tile, England, fourteenth century. Earthenware. L. 4 3/4".

Jug, Britain, ca. 1840. Whiteware. H. 6". The star-like slip decoration has been applied with a stamp in a manner analogous to the Huntington pottery examples.

Loaf dish, Huntington, New York, 1840–1885. Lead-glazed earthenware with slip decoration. L. 14 1/2". Only two loaf dishes with this stamped design survive. This pattern has been found at the Huntington pottery site.

Dish, Huntington, New York, 1840–1885. Lead-glazed earthenware with slip decoration. D. 12". The slip may be lighter from using the stamp repeatedly without redipping in the slip. This would increase decorating speed and conserve slip.

Loaf dish, Huntington, New York, 1840–1885. Lead-glazed earthenware with slip decoration. L. 12 7/8". This loaf dish and all other plates with the stamped star design have some sort of staining or muddiness in the glaze. This muddiness also appears commonly on other Huntington stamped patterns. This effect may have occurred through contamination due to experimentation with glazes or from the making of Rockingham-type glazed pots. Fragments of Rebekah-at-the-Well teapots have been found at the site including parts of saggars associated with their manufacture.

Plate, Huntington, New York, 1840–1885. Lead-glazed earthenware with slip decoration. D. 8". This is a stamped pattern found at the pottery site. The design is identical to the plate illustrated in fig. 36 with the exception of the circle in the design. This could be explained by either the addition or removal of the circle from the tin stamp. The plate is a rare small size and was bought at a local auction from a Long Island estate.

Dish, Huntington, New York, 1840–1885. Lead-glazed earthenware with slip decoration. D. 13". Example of a stamped design found at the pottery site in a very rare large size.

Plate, Huntington, New York, 1840–1885. Lead-glazed earthenware with slip decoration. D. 9 7/8". Like the loaf dish illustrated in fig. 32, this plate has staining in the glaze, which is typical of plates with the stamped star design. In addition, the clay used in this plate has an agateware look. This may have been clay left over from the manufacture of a “variegated” ware. Sherds of a scroddled-type ware have been found at the site.

Plates, Huntington, New York, 1840–1888. Lead-glazed earthenware with slip decoration. D. of all: 10 1/8". These three plates with a stamped design were probably made on the same mold.

Plates, Huntington, New York, 1840–1888. Lead-glazed earthenware with slip decoration. D. of all: 10 1/8". These three plates with a stamped design were probably made on the same mold.

Plates, Huntington, New York, 1840–1888. Lead-glazed earthenware with slip decoration. D. of all: 10 1/8". These three plates with a stamped design were probably made on the same mold.

Plates, New England, 1840– 1885. Lead-glazed earthenware with slip decoration. D. 10 3/4" and 9 1/8". Much caution must be used in attributing all stamped plates to Huntington. The designs on these two plates have not been found at the Huntington pottery site. They could have been made at one of the Norwalk potteries. In this collection there are other examples of plates with stamped designs which have not come from Huntington or Norwalk. Stamping technology surely must have been used at other American potteries from the same period.

Plates, New England, 1840– 1885. Lead-glazed earthenware with slip decoration. D. 10 3/4" and 9 1/8". Much caution must be used in attributing all stamped plates to Huntington. The designs on these two plates have not been found at the Huntington pottery site. They could have been made at one of the Norwalk potteries. In this collection there are other examples of plates with stamped designs which have not come from Huntington or Norwalk. Stamping technology surely must have been used at other American potteries from the same period.

Plate, Huntington, New York, 1851–1885. Lead-glazed earthenware with slip decoration. D. 8". This plate, along with another plate of the same size in a Long Island collection which says “Long Island,” has been attributed to the Huntington pottery. The “Nettie” plate was purchased at auction with a salt-glazed stoneware pot having the Brown Brother mark ca. 1870–1885. The stoneware jar was decorated with the word “Butter” in the same distinctive script that appears on this redware example in cobalt blue.

Dish, Huntington, New York, ca. 1851–1885. Lead-glazed earthenware with slip decoration. D. 11 1/2". Flying Cloud was a famous clipper ship launched on April 15, 1851. Another slip-decorated plate by the same decorator with the name “America” is in the Nina Fletcher Little collection. The latter plate commemorates the schooner for which the America’s Cup race was named. The sails for the America were made in Port Jefferson by Reuben H. Wilson. George Brown, the last owner of the Huntington pottery, was an original member of the local yacht club and built and sailed boats.

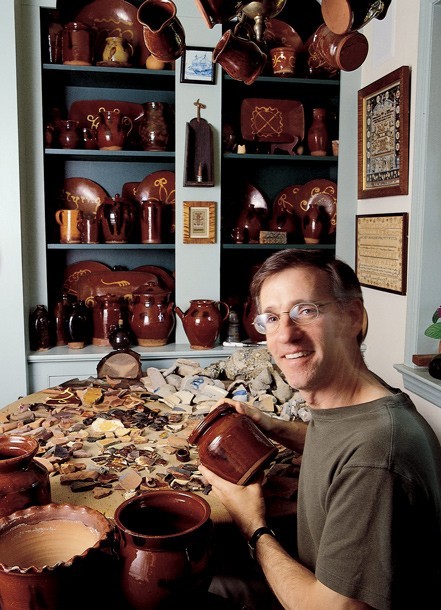

Anthony W. Butera, Jr.

Being a young pottery collector has its rewards and challenges. I began seriously collecting only about twelve years ago. In this relatively short time, I have found myself playing all sorts of roles in order to achieve my goals. Sometimes I am a student, scholar, detective, traveler, photographer, archaeologist, psychologist, banker, book collector, spy, beggar, writer, and often a pain-in-the-neck!

My process of collecting is evolving, providing the opportunity to discover what I really want and need. This, of course, leads to the question which most collectors attempt to answer: Why do I collect? For me, the answer is intertwined with the Huntington, Long Island, redwares that are the focus of my collection.

As a child growing up in an historic area on Long Island, I formed an appreciation for pottery. Although there were no collectors in the family, my parents always served formal dinners on fine china. I remember admiring and handling their wedding gifts, modern pieces of Wedgwood. Colonial Williamsburg was always mentioned in our family, especially since my parents lived near there when they were first married. I was familiar with the colonial style as our home was decorated in that manner. In the early 1970s, I was given The Flower World of Williamsburg by Joan Parry Dutton.[1] Among the illustrations are photographs of some of Colonial Williamsburg’s fine ceramics collections. When I first visited Colonial Williamsburg in 1975, these illustrations inspired me to photograph the ceramics in many of the historic buildings. These are the first pictures I took of ceramics.

As a high school student, I enjoyed all of my activities and studies, having a particular love of history, Latin (which included Roman history), and music. My major in college was music. After college I returned home to work in the family business of mason contracting. Living in a historic area occasionally meant working on historic homes, and I found I needed to know how to treat these homes properly. The magazines Colonial Homes and Early American Life provided a resource at that time. While looking through these magazines, I would come across photographs of redware, which piqued my curiosity. On our frequent trips to a summer place in upstate New York, I never saw this mysterious redware, so I began a search. When I finally found a fluted redware mold in an antique shop in Rockland, New York, I bought it. Although I have since learned that this first piece was of European origin, I still enjoy having it in my collection.

Living near Manhattan gives a budding collector a great advantage. Many great museums, auction houses, and antique shows are nearby. With my growing interest in redware, I began to attend more and more shows to educate myself. The first time I attended the International Fine Arts and Antiques Show in New York City, dealers Kinneman and Ramaeker were exhibiting. The focal point of their booth for me was a very large, slip-decorated American redware charger. Although I did not purchase it, the experience inspired me to start my hunt in earnest. While antiquing with family and friends, I came across the dealers Jack and Maryellen Whistance who have a small shop that specializes in American antiques, including a fine selection of redware. I have often returned to their beautiful shop to listen to their advice on collecting and to buy many pieces of redware, some of which are illustrated here.

The magazine Antiques is a necessary tool for any collector. After seeing Jeannette Lasansky’s article on Pennsylvania pottery in the October 1990 issue, I attended redware potter Lester Breininger’s annual porch sale, since most of the pieces illustrated in the article were from his personal collection.[2] The sale included demonstrations of throwing pots and slip-decorating. After meeting Lester Breininger and viewing his collection, which focused on locally made pottery, I was motivated to collect what was made in my area of Long Island at the Huntington pottery. This decision coincided with a newly published book by Cynthia Corbett for the Society for the Preservation of Long Island Antiquities (SPLIA), Useful Art: Long Island Pottery.[3]

What initially struck me in reading Corbett’s book were the illustrated geometric designs on plates attributed to the Huntington pottery. These designs were described as being first incised, then having slip applied over the incising. This technique fascinated me and provided another good reason to collect these plates. Here was something not only unique among the many American redwares but also something made and used in my area.

The history of the Huntington pottery, or more accurately, the potteries, extends over a century. The Huntington community was rich in clay resources with easy water access to New York City and the Connecticut market. Although the clay sources of the area were used in brick making as early as 1751, it is uncertain exactly when the first pottery arose. It has been speculated that Jonathan Titus may have operated a pottery in conjunction with his tavern operation in the late eighteenth century. The first historical mention of a pottery on the site occurs in 1805 when a firm known as Samuel J. Wetmore and Company took over the property. From that point on, documentation of the pottery varies in detail, as various owners and workmen are known to have been associated with the operation. A number of historical accounts shows the range of earthenware and stoneware produced there. The best documentation for the pottery comes with the tenure of the Brown brothers from 1863 until 1905 when operations ceased.[4]

The redware from this one hundred-year-old pottery operation, which served the everyday needs of nineteenth-century Long Island communities, has been the focus of my collecting efforts. In spite of the availability of documents and other evidence, surprisingly little information has been published about the actual redware products of Huntington, and after collecting a fair number of redware plates, I became increasingly dissatisfied with the few published descriptions of their manufacture I could find. Why would such a labor intensive process have been employed? Why did so many of these redware plates have missing areas of slip? Why did some plates have more slip applied than others? Most importantly, why did Greg Shooner, a well-versed modern redware potter, refuse to accept this labor intensive process when he decorated his own red earthenware?

In 1996 technology historian Don Carpentier held the first of his annual workshops on ceramics at Eastfield Village near Albany, New York. This was a good opportunity for me to bring this question of slip decorating to scholars and, more importantly, to potters. When I arrived at Eastfield on the morning of Greg Shooner’s lecture, I noticed tin welding equipment which had been used recently at the back of the room. As the day progressed, Greg and Don kept asking me what I thought about the Huntington plates and how did I think they were made. At the end of Greg’s lecture, he and Don surprised me by demonstrating how the plates were really decorated. A tin stamp was made, dipped in the slip, and then pressed onto the rolled-out slab of clay. The slip came off the stamp onto the clay. In addition, the stamp left a faint impression in the clay. Don had known about this technique through his study of English mochaware, and he had published a demonstration of its use on mocha ware.[5]

After discovering that this method of stamping was used at the Huntington Pottery, I became interested in exploring the sources of the designs used for the tin stamps. Some designs were similar to those found on English medieval paving tiles. They are commonly found on wrought iron from all periods, including contemporary factory-made wrought iron. They are also similar to designs on Gothic Revival encaustic tiles, which are interesting because the Gothic Revival period coincides with the same period that the Huntington stamped plates were produced. I have tried to somehow connect these trades, but so far I can only agree with this quote: “Although slip decorations probably derive from multiple and unconsciously chosen sources . . . [they] resemble gothic design elements, such as a rose window, crockets, quatrefoils, and the wheel of life . . . these designs were devised as something aesthetically familiar and easily worked.”[6]

So far, all of these stamped plates have been attributed to Huntington, Long Island. Such attributions, however, must be made with caution. To date, I have counted at least thirteen designs that were used. Some of these patterns might have been altered by changes made in the tin stamp by removing or adding pieces of tin. But another explanation for the large number of patterns is that some stamped plates might have been made elsewhere. Since there is little published archaeology to support attribution, I have had to rely upon my own guidelines based on the collection of sherds that I have found at the actual site of the Huntington pottery. In addition, I consider attributes such as plate sizes and shapes. Furthermore, the provenance of the pieces is a major factor in supporting my findings. Unscientific as this may seem, I realize that all of the questions cannot be answered until we have more archaeological data. Until then, we have to rely on our instincts and the understanding of the potters and their culture.

Slip-script red earthenware plates have always been popular with collectors. On a visit to an antique shop on Oyster Bay, Long Island, I came across a plate with the name “Nettie,” in slip-script. Knowing the dealer and his sources, I thought that the plate was possibly a Huntington piece. Without additional information, I was not able to attribute the plate, so I did not buy it. A few years later it came up for auction and was advertised together with a salt-glazed stoneware pot with the Brown Brother mark circa 1870–1885 and, in the same hand, “butter” in cobalt blue slip. This was enough information for me to attribute the “Nettie” plate to Huntington, and I was the winning bidder.

Shortly afterwards I met a Southampton dealer who owned a slip-script plate in the same distinctive script which said “Long Island.” I then remembered seeing a slip-script plate advertised in Maine Antique Digest that said “Flying Cloud.” Luckily, I had seen this plate at the Winter Antiques Show in New York, and as it was still available from the dealer, I purchased it. To accompany the traveling exhibit of the Bertram and Nina Little Collection, which was given to the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities (SPNEA), a small catalog was published.[7] Catalog illustration number fifty-eight is a slip-script plate in the same hand as the three previously mentioned plates. The plate in the Little collection is inscribed “America” for, I believe, the schooner America that won the Hundred Guinea Cup on August 22, 1851. As a collector, I was pleased to have a slip-script plate closely connected to one in the Little collection, a collection that I have admired greatly and from which I have learned a great deal.

The slip-script on these plates deserves more discussion. Both the “Flying Cloud” plate and the “America” plate are highlighted with a double dash line. Since the “America” plate is obviously decorated with a two-quilled slip cup, it is safe to assume that the two-quilled cup was also used to decorate the “Flying Cloud” plate, even though the name is a single line of slip. The decorator would have to turn the cup so that only one line of slip could be formed. To form the double dotted line of slip, which is on the bottom of the plate, the decorator would once again quickly turn the cup, and a double line would be formed. When you closely examine the dot on the letter “i” in “Flying Cloud,” you can almost see two dots.

Since a great deal of skill was needed to competently use the free-flowing slip-trailing method of decoration, we can readily see why stamping the plates with slip was developed. The stamping technique for creating decoration on ceramics can be found in early fourteenth-century English tiles, redware sherds from the James Kettle Pottery in Danvers, Massachusetts (1687–1710), and even English mochaware. Stamps permitted decoration to be applied as quickly as possible using relatively unskilled labor.

We have to wonder why slipware potters did not resort to the stamping technique more often, since it seems to have been around for centuries. Was it part of the apprenticeship to learn how to use the slip cup, and taboo not to learn this technique? Which kind of decoration did consumers prefer, or were they able to tell the difference? Were consumers only interested in getting the product as quickly and cheaply as possible? Did a potter have a bad day and break all his slip-cups on hand and have to come up with a quick way to decorate? Although it may be impossible to answer these questions, they need to be asked to increase our understanding.

American genre painter William Sydney Mount has been a great resource for me as a collector of Long Island pottery. For years I have admired his pictures at the Long Island Museum (formerly the Carriage House Museum) and his prints in the homes of friends and family. In the SPLIA book, several paintings illustrate pottery in a period setting. When Deborah J. Johnson’s William Sydney Mount was published in 1998, I studied the paintings and the pottery included in them.[8] A good sized redware jug is at the center of the painting The Truant Gamblers, 1835 (fig. 13). Intrigued that this form existed at such an early date, I hoped to find a similar form. Much to my surprise, on a visit to a dealer in Southampton, Long Island, I found a nearly identical jug. The dealer told me that the jug had come from an early collection from Setauket, Long Island, just a few miles from where William Sydney Mount had painted the picture. The jug, and other items in the collection, had been moved off the island in 1950, was later sold at an auction in North Carolina, traveled to Southampton with the dealer, was bought by me, and returned to within two miles from where it had started. That would qualify the jug as a favorite piece, since it practically found me.

At the Long Island Museum’s exhibition on William Sydney Mount’s brother, Shepard Alonzo Mount, I was delighted to see the original painting The Breakfast Call (fig. 19). The only published photograph I knew of was in Deborah Johnson’s Shepard Alonzo Mount: His Life and Art.[9] The photograph in this book is very small and in black and white. The actual painting is quite large, thirty-six by twenty-nine inches, and in the lower left hand corner is a red earthenware pitcher with the handle painted beautifully, the same type of extruded handle which I had always associated with the Huntington Pottery. It is a unique piece, and I am fortunate to have these well-known artists who painted red earthenware pottery represented in the locale where I collect. However, I have yet to find an American period painting that includes a picture of American slip-decorated earthenware.

As a collector with limited resources, I have tried to educate myself as much as possible, and books are a ready resource. When I first started buying books on American red earthenware, they were mostly older publications with poor photography and hit-or-miss research. But there were exceptions. Besides the SPLIA book on Long Island pottery, good information could be found in Lura Woodside Watkins’ Early New England Potters and Their Wares. In addition, William C. Ketchum’s Potters and Potteries of New York State, 1650–1900 had a very good chapter on the Huntington pottery.[10] However, even though Ketchum quotes Richard M. Bayles’ Sketches of Suffolk County, Historical and Descriptive (1874), he does not include the entire eyewitness account of Bayles’ visit to the Brown Brother operation at the Huntington Pottery. Finally, here it is:

Brown Brother’s Pottery, located among the settlement on the east side of the harbor, is one of the interesting features of the place. Its origin is ancient, some part of the establishment having been running since the pre-revolutionary period—so says tradition. The buildings in which the business is carried on are not in a shape to be easily described but they probably embrace some seven or eight thousand square feet of floor room, for the most part being two floors in height. The Brown Brother’s manufacture a great variety of “stone” and earthenware such as jugs, jars, butter-pots, pie platters, sauce pans, flower pots, hanging baskets &c. Six or eight men are kept at work, two wagons are all the time traveling up and down the island, and during the busy seasons of the spring and autumn sloops are chartered, loaded with goods and sent away to different ports along the Connecticut shore as well as other places. The process of making the specialties of this establishment is very simple, yet could be much better described by the hands of the potter with the clay, than with pen and ink upon paper. The first thing, however, to be done is to mix and temper the clay. For the different articles different qualities of material are used and for most of the articles clay from different mines have been mixed together. This mixing is done in a huge bin. The clay is then placed in the tempering machine, which is an upright iron cylinder with an arrangement inside which being turned by horse power grinds up the clay and squeezes it out through holes about two inches in diameter, near the bottom of the mill. Inside these holes a fine wire sieve is placed so as to keep back any sticks or small stones that may be in the clay. The doughy mass is then stowed away in a damp cellar where it will keep for weeks without losing its temper, and from which it is taken as it is needed for use. Nearly all the kinds of ware made here are turned on a sort of lathe. This is simply a disk, say a foot or more in diameter, made of two inch plank, and fastened in a horizontal position on the end of a spindle which is kept whirling around by a foot treadle. On the center of this disk a lump of clay is placed, and as it spins round the hands of the skilled workman are pressed against it from outside and inside so as to draw it up to the desired shape. In making jugs the handle is made separate and stuck on after the jug is finished. Some of the ware is cast in molds of plaster of Paris. This process is more tedious and consequently about twice as expensive. After the ware is formed and sufficiently dried to allow it to be handled with safety it is stacked up in large ovens or kilns, to be baked. These kilns, of which there are two here, are made of brick, of circular form, ten or twelve feet across them and six to eight feet high and arched over the top. When they are filled, a hot fire is started in the pit below, and the heat and flames pass up through the mass of ware until it becomes of a white heat. The glazing on the outside of stone ware is produced by throwing salt into the kiln while the heat is greatest. This baking process consumes three hundred cords of wood per annum. The Pottery is located immediately on the shore and a dock is connected with it, so sloops can float up to the premises to land wood or load with ware.[11]

This is the only eyewitness account of the Huntington pottery that I know of. Even though it is a late account, it does describe the making of earthenware. Most important here is the use of plaster of Paris molds, which probably indicates the making of Rebekah-at-the-Well tea pots, corresponding with sherds found at the site and kiln furniture associated with their manufacture. This account gives us a glimpse of the scale and the activities conducted at the pottery in the third quarter of the nineteenth century.

My study of Huntington, Long Island, red earthenware has led me to consider all kinds of ceramics. As a result, I have read books on different types of pottery and porcelain, and after attending lectures at Eastfield Village every year, I have had the opportunity to talk to authors and collectors whose collections have been published. As my understanding grows, my collecting skills improve.

The title for this article comes from one of my favorite quotes in the book Iznik, The Pottery of Ottoman Turkey.[12] “Informed conjecture” is perhaps a polite term for what many collectors employ in the process of rationalizing a collection. When empirical facts are few and far between, we have to make the best use of the smallest available evidence. Hopefully, the publication of these examples presented here will add to the information about Huntington redwares and reduce the conjecture.

One of my favorite stories about collecting is from the Bowles Collection of 18th-Century English and French Porcelain. When Henry Bowles takes delivery of a very rare Chelsea strawberry dish, the customs agent shakes his head in disbelief when he sees the price paid for the rather stained piece.[13] I have experienced this same reaction many times after showing friends and family pieces of redware that I have bought, and this is true of other collectors and scholars. Although Iznik pottery, Chelsea porcelain, and Huntington, Long Island, red earthenware are from completely different areas in the world and span different centuries, they share a continuum in the world of ceramics and the struggles of the potters who made them.

One issue common among ceramic collectors is that of condition. Condition can be a problem when dealing with the relatively fragile red earthenware, which was usually subject to heavy use. My standards have always been to keep repaired objects out of the collection. Repairing one of these humble pots is like stripping the original finish off an antique piece of furniture. No matter what has happened to a piece, whether fortunate or unfortunate, it adds to the truthfulness of the object, and it is dishonest to make it something that it is not.

Subjects for debate are plates that have an excessive amount of rim chipping. Some of these chips may have been the result of plates fused together in firing and then broken apart. This may be one reason for the use of coggling, where the interstices created by tooling the rims make it easier to separate fused plates. Without these flaws, however, we could not study how plates were placed in the kiln and fired. This roughness must have been acceptable to consumers who bought inexpensive red earthenware by the dozens and therefore should be acceptable to modern day collectors.

My collection now includes sherds I have found from a site on the shore of Huntington Harbor where wasters were dumped. On my first visit I had some bittersweet feelings. The site is a massive jumble of wasters from at least one hundred years of pottery manufacture, which have tumbled in the tides since they were discarded. As I began to pull these wasters from the sand and mud, I was amazed at the great variety. I found slip-decorated redware with stamped patterns, slip-cup decorated redware, combed redware, slip with copper oxide green, fragments of plates completely covered in slip, bisque-fired redware, a great variety of extruded redware handles, fragments of redware hollow ware vessels, salt-glazed stoneware with cobalt blue decoration, Albany-slip stoneware, Rebekah-at-the-Well teapot sherds, scroddleware or agateware, possibly black-glazed teapots, and the kiln furniture associated with their manufacture such as setting tiles, stilts, and many stoneware spacers. The diversity here represents the success of the industry for over a century, and I now realize the huge amount of history waiting here to be studied.

Another dimension of my collection, not illustrated here, are reproductions. Some of my reproductions are as pleasing to me as the originals: they can be used, they are easy to find, and, most of all, they are cheap. Reproductions can make good learning tools. Through the mistakes I have made handling them (in other words breaking them), I have learned how fragile this pottery can be. I have also found that treated correctly, it can readily survive. From speaking with the potters who make reproductions, I have also learned a great deal. I once asked one of the Shooners why they put slip cyma curved designs on a pair of redware candlesticks, hoping that the answer would be that they had seen them on English slipware. Instead, the answer was, “I was using them to fill space.” Disappointed at first with this response, I then realized that Greg and Mary Shooner have studied and worked with redware pottery from Europe as well as America—and that helped explained it. Although they did not really invent the design when they used it, they had probably seen it, and subconsciously added it to their repertoire. We see many designs cutting across cultures and centuries, like an unspoken language, communicated through pottery and its apprentices.

My collecting continues and probably will not stop, since it is now incorporated into who and what I am. Yet, I sometimes ask myself what am I really collecting? Are these just plain pots with no souls or are they objects hiding tremendous wealth in potting history? Once the potter Michelle Erickson told me she greatly admired red earthenware potters because the type of clay they used was so difficult to work. How interesting this is, since redware was the most common pottery, and yet only the most skilled potters could make it. Listening to the piano waltz D.145, No. 2 by Franz Schubert, which lasts only about forty-eight seconds, I noticed the similarities of this waltz to red earthenware pottery. They are both very simple on the surface, made quickly, made for everyday use for the common people, and yet they are a shadow of the past. They both walk the fine line between simplicity and complexity. What collectors are really looking for is not perhaps the objects but the people behind them, the source of that shadow. I have always been curious to know what has happened in the past and to connect with that community. This is what good scholarly collections should be about. I hope my collection is one of these and can be shared on these pages.

Joan Parry Dutton, The Flower World of Williamsburg (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1973).

Jeannette Lasansky, “Pennsylvania Pottery in Berks County Collections,” Antiques 138, no. 4 (October 1990): 810–19.

Cynthia Arps Corbett, Useful Art: Long Island Pottery (Setauket, N.Y.: Society for the Preservation of Long Island Antiquities, 1985).

Ibid., pp. 20–25.

Lynne Sussman, “Mocha, Banded, Cat’s Eye, and Other Factory-made Slipware,” Studies in Northeast Historical Archaeology Monograph Series, no. 1 (Boston: Council for Northeastern Archaeology, 1997).

Corbett, Useful Art: Long Island Pottery, p. 29.

Exhibition catalog, A Passion for the Past: The Collection of Bertram K. and Nina Fletcher Little at Cogswell Grant (New York: The American Federation for the Arts, 1996).

Deborah J. Johnson, William Sydney Mount: Works in the Collection of The Long Island Museum (New York: Museums at Stony Brook, 1998).

Deborah J. Johnson, Shepard Alonzo Mount: His Life and Art (New York: Museums at Stony Brook, 1988).

Lura Woodside Watkins, Early New England Potters and Their Wares (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1950); William C. Ketchum, Jr., Potters and Potteries of New York State, 1650–1900 (Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 1987), pp. 88–103.

Richard M. Bayles, Sketches of SuVolk County, Historical and Descriptive (Port JeVerson, N.Y.: privately printed, 1874).

Nurhan Atasoy and Julian Raby, Iznik, The Pottery of Ottoman Turkey (London: Alexandria Press, 1989), p. 49.

Simon Spero, The Bowles Collection of 18th-Century English and French Porcelain (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, 1995), p. xxi.