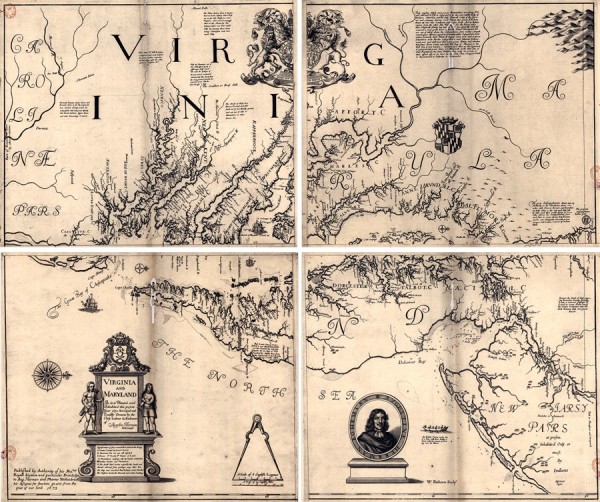

Augustine Herrman (1621 or 1622–1686), Virginia and Maryland as It Is Planted and Inhabited This Present Year (London: Augustine Herrman and Thomas Withinbrook, 1673). Engraving. 31 1/2" x 37 1/2" (1 map on 4 sheets).

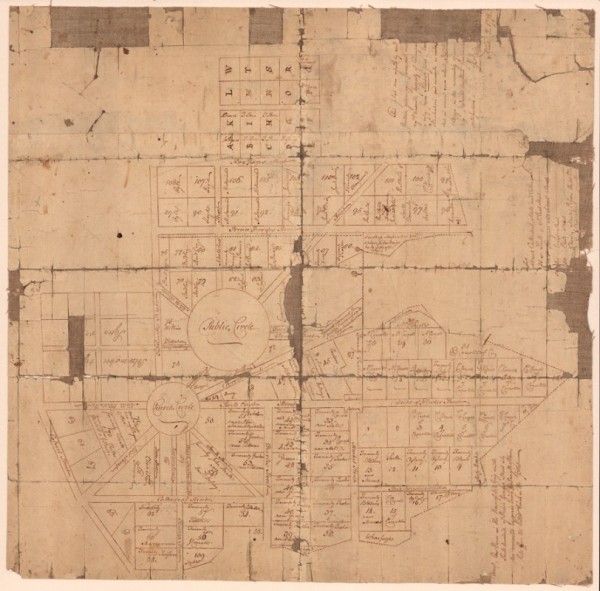

John Callahan, copy of James Stoddert’s 1718 “A ground platt of . . . Annapolis,” 1798. (Courtesy, Collection of the Maryland State Archives.) Stoddert’s map was based on a plan by Lieutenant Governor Francis Nicholson.

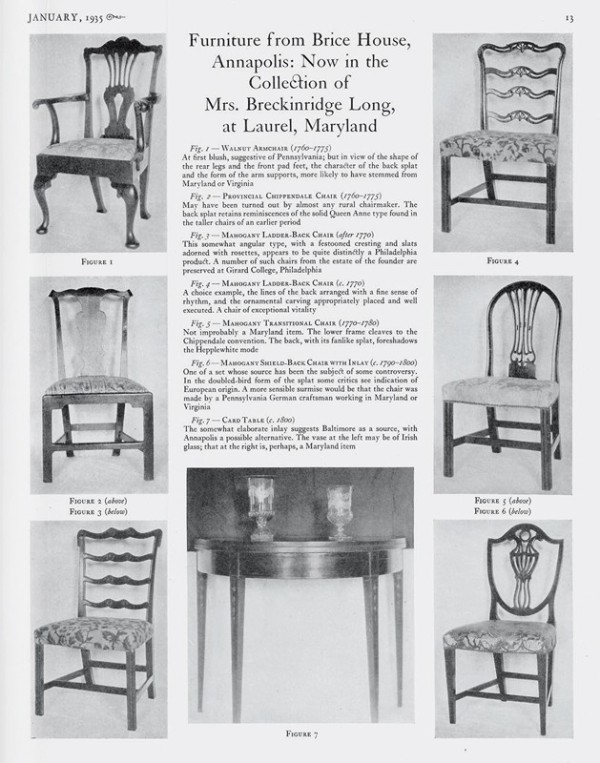

“Furniture from Brice House, Annapolis: Now in the Collecion of Mrs. Breckinridge Long, at Laurel, Maryland,” Antiques 27, no. 1 (January 1935): 13.

James Brice House, 42 East Street, Annapolis, Maryland, built 1767–1774. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

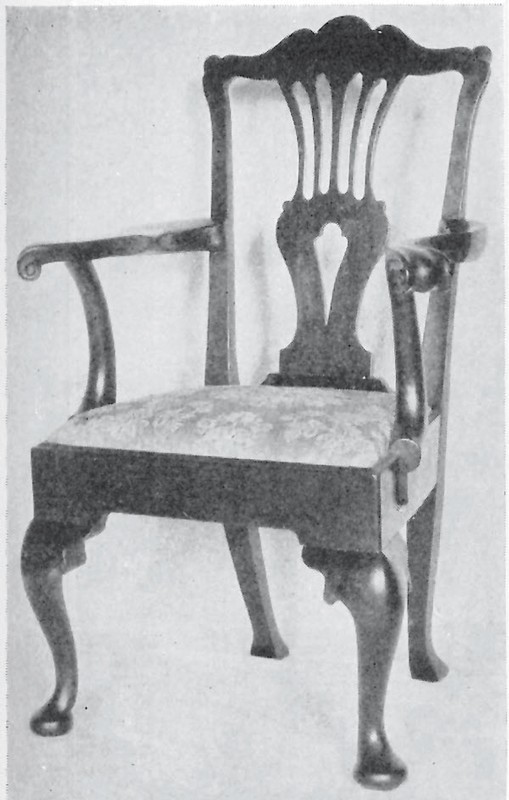

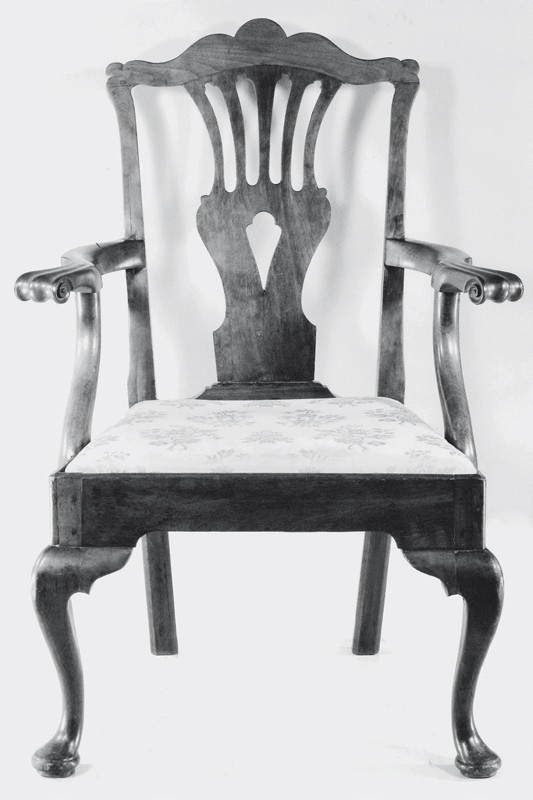

Detail of fig. 3 showing the Brice armchair, Annapolis, Maryland, 1745–1755. Walnut. Dimensions and current location unknown.

John Brice II House, 195 Prince George Street, Annapolis, Maryland, built 1739. (Photo, Historic American Buildings Survey, no. HABS MD,2-ANNA,14—1.)

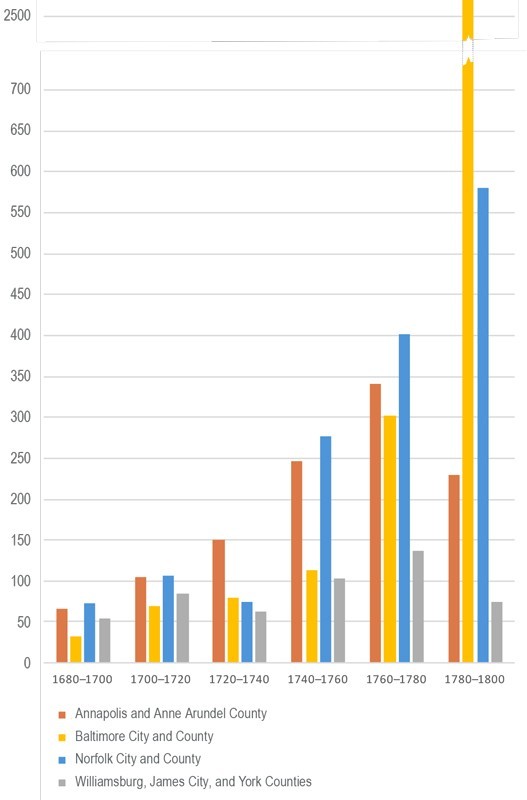

A comparison of the numbers of craftspeople documented in the MESDA Craftsman Database in Annapolis, Baltimore, Norfolk, and Williamsburg, and their environs.

Armchair, Annapolis, Maryland, 1745–1755. Woods not identified. Dimensions not recorded. (Current location unknown; photo, MESDA Research Center.) This armchair was sold by Craig and Tarlton, Raleigh, North Carolina, in 1980.

Armchair, Annapolis, Maryland, 1745–1755. Woods not identified. Dimensions not recorded. (Current location unknown; photo, MESDA Research Center.) Photographs of this chair were sent to Craig and Tarlton by Mrs. J. G. Whitman in 1982.

Side chair, Annapolis, Maryland, 1745–1755. Walnut and yellow pine. H. 37 3/4", W. 23", D. 20 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Wes Stewart.) This side chair is one of six in a private collection. Three other chairs from the same set survive in the collections of Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library, acc. nos. 69.765, .1, .2 and Colonial Williamsburg, acc. no. 2010-26 (see fig. 23).

Armchair, Annapolis, Maryland, 1745–1755. Walnut and yellow pine. H. 41", W. 22 1/2", D. 19 1/4". (Private collection; photo, the author.)

Detail of the side chair in fig. 10. (Photo, Wes Stewart.)

Detail of the numbered strip on the rear rail of a side chair from the same set as the side chair in fig. 10. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the side chair in fig. 10 showing the double-tenon joint between the seat rail and rear stile. (Photo, Wes Stewart.)

Detail of the side chair in fig. 10 showing the joint between the front and side seat rails. (Photo, Wes Stewart.)

Detail of the armchair in fig. 11. (Photo, the author.)

Side chair, Annapolis, Maryland, 1745–1755. Walnut and yellow pine. H. 39", W. 22", D. 20". (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, gift of Dr. and Mrs. Thomas H. Sears Jr.; photo, Wes Stewart.)

Detail of the side chair in fig. 17. (Photo, Wes Stewart.)

Armchair, Annapolis, Maryland, 1755–1770. Mahogany and yellow pine. H. 37 3/4", W. 27 1/4", D. 24". (Private collection [courtesy, Sumpter Priddy, Inc.]; photo, Dennis McWaters.)

Dressing table, Annapolis, Maryland, 1745–1755. Walnut, poplar, white cedar, and yellow pine (by microanalysis). H. 29", W. 34 1/8", D. 19 1/2". (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts; photo, Dan Routh.)

Details of the feet on the chairs in figs. 10 and 19, and on the dressing table in fig. 20. (Photos, Wes Stewart [left], Dennis McWaters [center], and Dan Routh [right].

Side chair, Ireland, 1745–1755. Mahogany. H. 38 1/2", W. 22", D. 21 3/4". (Collection of Marshall Field V; photo, Christie’s Images.)

Interior of Sands House, 130 Prince George Street, Annapolis, Md. Undated photograph, Maryland Historical Trust Survey. At the far right is the side chair now at Colonial Williamsburg and part of the same set as the chair in fig. 10.

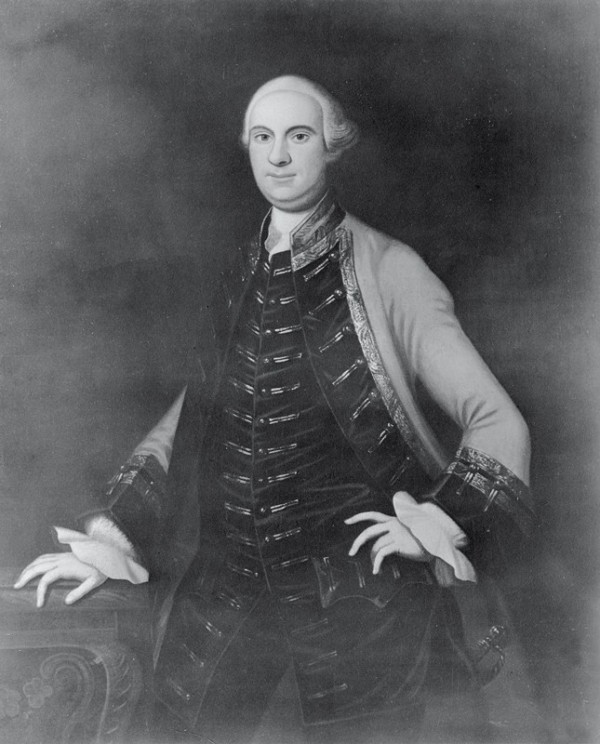

John Hesselius (1728–1778), Portrait of Horatio Sharpe, ca. 1760. Oil on canvas. 50" x 40" (approx.). (Private collection; photo, courtesy of the Frick Art Research Library.)

Governor Samuel Ogle House, 247 King George Street, Annapolis, Maryland, ca. 1739. (Photo, Historic American Buildings Survey, no. HABS MD,2-ANNA, 1—5.)

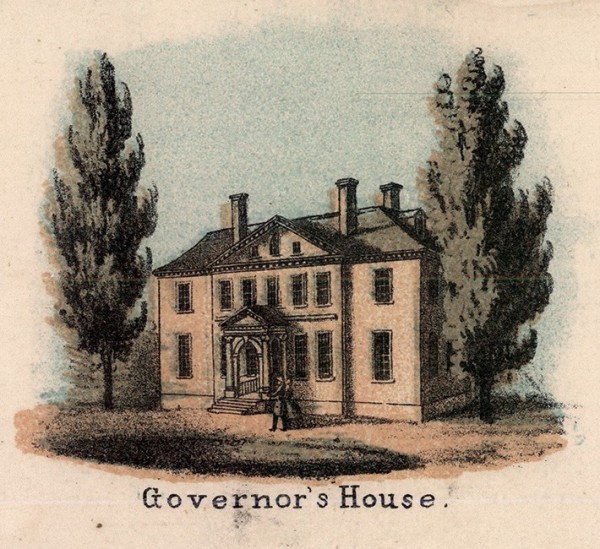

Detail (inset of Governor’s House) of Bird’s Eye View of the City of Annapolis, Capital of the State of Maryland, ca. 1858. Lithograph. (Courtesy, Collection of the Maryland State Archives.)

ANNAPOLIS, MARYLAND, situated at the mouth of the Severn River and the Chesapeake Bay, is one of just two American colonial capitals that have remained in place since the seventeenth century; the other is Boston, Massachusetts. During the early decades of the eighteenth century, Annapolis underwent a dramatic transformation. As vividly described in two satirical poems by English author Ebenezer Cooke (ca. 1667–ca. 1732), the capital went from a small cluster of poorly built structures to a prosperous city that could support the livelihood of several hundred craftspeople.

Cooke’s first poem, published in London in 1708 and entitled The Sot-Weed Factor, or, A Voyage to Maryland, describes the plight of an unfortunate Englishman who, “Condemn’d by Fate to way-ward Curse, of Friends unkind, and empty Purse,” ventures forth to the Maryland Colony as a tobacco dealer, or sot-weed factor. Cooke’s protagonist describes “The Laws, Government, Courts, and Constitutions of the Country, and also the Buildings, Feasts, Froliks, Entertainments and Drunken Humours of the Inhabitants . . . in burlesque verse” as he travels across the colony in search of something he might call civilization. At the end of the narrative the peripatetic poet finally arrives in Annapolis, “the chief (city) of Maryland”:

Up to Annapolis I went,

A City Situate on a Plain,

Where scarce a House will keep out Rain;

The Buildings framed with Cyprus rare,

Resembles much our Southwark Fair:

But Stranger here will scarcely meet

With Market-place, Exchange, or Street;

And if the Truth I may report

‘Tis not so large as Tottenham Court[1]

To Cooke’s protagonist—an Englishman familiar with major urban metropolises like London— the idea that Annapolis was a city, let alone a capital city, must have seemed laughable.

Maryland in 1708 was a rural colony. Augustine Herrman’s 1673 map of the colony delineates its scattered plantations clustered around creeks, inlets, rivers, and bays (fig. 1).[2]The few cities shown on Herrman’s map were then little more than the sites of courthouses for the transaction of business, or of wharfs for the loading and unloading of cargo. In 1694 the colony’s lieutenant governor, Francis Nicholson, moved the colony’s capital from St. Mary’s City to Arrundleton, renaming it “Annapolis” in honor of Queen Anne of England. His motives were geographic and political.[3] Nicholson, who fancied himself an architect and a designer, drew up an elaborate town plan for the new capital city (fig. 2). His proposed circles and vistas were meant to evoke the baroque town plans of cities like London. But little of this elaborate plan was visible to Cooke’s visiting sot-weed factor on his visit in 1708, some fifteen years after Nicholson’s ambitious plan was first adopted.

Maryland planters, clustered along navigable waterways, were not particularly interested in urban centers like the new city of Annapolis. These planters generally traded their tobacco and other agricultural products directly with ship captains, English merchants abroad, and traveling sot-weed factors like Cooke’s protagonist; they ordered European goods directly from urban centers like London, Liverpool, Edinburgh, and Dublin. They were, in many ways, residents of a far-flung London suburb. However, even though planters could bypass Annapolis economically, they could not avoid it politically. Recording certain legal documents, acquiring public lands, and lobbying for and manipulating government largess all required a trip to Annapolis.

Two decades after his first visit, Cooke’s wandering “Sotweed Factor” returned to Annapolis and recorded his impressions of the city in a new poem entitled Sotweed Redivivus. He was greeted by a very different city:

Bound up to Port Annapolis

The famous Beau Metropolis

Of Maryland, of small Renown,

When Anna first wore England’s Crown,

Is now grown rich and opulent;

The awful Seat of Government.[4]

A remarkable amount of the city’s eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century urban landscape remains. However, scholarship of the furniture that once filled these houses is lacking, especially when compared to the body of work that has been published on furniture production in other colonial American cities. This essay explores a small group of seating furniture made by one or more related shops in Annapolis between about 1745 and 1760 in an effort to fill that gap.

In January 1935 the magazine Antiques published a one-page photo essay of furniture from Annapolis’s Brice House (fig. 3). James Brice (1746–1801) was a wealthy lawyer, planter, and politician, the third generation of his family to live in Annapolis. His grand house, constructed between 1767 and 1774, represented the apogee of the family’s wealth and prestige in the city (fig. 4).[5] The residence was one of several architecturally related houses constructed for the city’s wealthier families in the decade before the American Revolution. The first Brice family heirloom illustrated in the Antiques photo essay is a walnut armchair with cabriole legs, pad feet, a pierced vasiform splat, and baroque crest rail that stylistically predates James’s town house by as much as twenty years (fig. 5). It seems likely that James inherited the chair from his father, Judge John Brice (1705–1766), whose 1739 house was, like the house his son built over thirty years later, among the more ambitious of its day (fig. 6).[6] The chair may well have been one of the thirteen made of an unidentified wood recorded in John’s dining room and valued at £6 12s. 6d. in his probate inventory of 1767.[7] Perhaps the same chairs—minus two—were those listed in his son’s 1802 probate inventory, by which time they were described as “11 very old walnut chairs with Stuffed bottoms” worth ten dollars.[8]

The design of the Brice family armchair left the Antiques author struggling to describe how it fit in the larger canon of American decorative arts, a canon that favored Northern cities like Philadelphia. “At first blush [the design is] suggestive of Pennsylvania,” located just 125 miles away by land, “but in view of . . . the front pad feet, the character of the back splat, and the form of the arm supports, [this armchair is] more likely to have stemmed from Maryland or Virginia.”[9] The unfortunate author had little to go on. The first significant study of Maryland furniture would not be published until a dozen years later, when in 1947 the Baltimore Museum of Art presented an exhibition of Baltimore and Annapolis furniture.

That exhibition relied on the fieldwork of Baltimoreans Eleanor Stewart and John Schwartz, and dealer Joseph Kindig Jr. of York, Pennsylvania, who “comb(ed) the entire countryside of Maryland” in search of material. Henry Francis du Pont and Joseph Downs selected the final objects for the show and the catalogue. The authors lamented that the “scarcity of documents, labels, and bills of sale” made definitive attributions a matter of “probablys, maybes, and seeminglys.” A chapter on Maryland furniture of the Chippendale period, appended to the catalogue, carried a warning to readers that, “since the defining of a local Chippendale style is in a preliminary state, the following section is presented as a supplement to this catalog.”[10] In 1968 Baltimore Museum of Art curator William Voss Elder III returned to the subject of pre-Revolutionary Maryland furniture with an exhibition and catalogue. Two decades of additional research, aided by the development of microscopic wood analysis, allowed him to expand the corpus of possible early Maryland furniture. Further advances were made in 1984 when the Maryland Historical Society (now the Maryland Center for History and Culture), home to an extensive collection of early Maryland decorative arts, published a catalogue of its furniture collection written by Gregory Weidman.[11]

These publications and exhibitions gradually expanded the body of works that could be ascribed to eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Maryland. However, with scant evidence, the pre-Revolutionary period remained little understood, and within the state itself it was even more difficult to differentiate among forms made in Annapolis, Baltimore, Georgetown, and other smaller cities. The one exception to the ambiguity of early Maryland furniture making is the work of John Shaw (1745–1829), a cabinetmaker who frequently labeled his wares and was the subject of a 1983 exhibition at the Baltimore Museum of Art curated by William Voss Elder III and Lu Bartlett.[12]

The extensive study of Shaw’s life and works belies the scarcity of information on other Annapolis artisans.[13] However, the documentary records that do survive contribute significantly to our understanding about the craftspeople who were working in the city before the end of the American Revolution. To date, the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (MESDA) Craftsman Database project has identified more than 750 craftspeople before the American Revolution present in Annapolis and surrounding Anne Arundel County; of these, 316 worked with wood as cabinetmakers, carpenters, and joiners.[14] A comparison of the number of craftspeople documented by MESDA in and around Annapolis, Baltimore, Williamsburg, and Norfolk illustrates the relative ebb and flow among these major Chesapeake cities (fig. 7). It shows how Annapolis in particular flourished during a brief period between the end of the French and Indian War and the American Revolution. Unlike Williamsburg and Norfolk in the southern Chesapeake, Annapolis was both the seat of the colonial government and a major port. After the Revolution, though Annapolis remained the center of Maryland’s government, Baltimore, with its access to the American west by river, road, canal—and later, railroad—eclipsed Annapolis and its economy exponentially. Additionally, the development of the District of Columbia and the growth of the nearby cities of Georgetown and Alexandria diminished Annapolis’s relative economic status in the period after the Revolution. And Philadelphia, always a larger and more economically powerful city—and at the center of much American furniture scholarship—loomed large to the northeast. Twentieth-century market forces also contributed to obscuring Annapolis’s material past. When the Baltimore Museum of Art mounted its first exhibit of Maryland furniture in 1947, the organizers lamented that it might already be too late given how many early furnishings had been carried away, their origins forgotten.[15] Two decades later, when the Baltimore Museum of Art mounted another Maryland furniture exhibit, William Voss Elder noted “the overemphasis by collector and dealer alike on Philadelphia, Newport, and New England” and how “in the frantic years of collecting in the first decades of this century, much furniture in the Queen Anne and Chippendale style left Maryland and assumed a new identity.”[16]

Despite the relative lack of mid-eighteenth-century material with strong An napolis ties, the Brice family armchair in figure 5 provides a starting point from which a small group of related mid-eighteenth-century Annapolis seating furniture can be identified. In 1980 the antiques firm Craig and Tarlton of Raleigh, North Carolina, referenced the Brice family armchair in an advertisement for a nearly identical armchair (fig. 8).[17] This advertisement caught the eye of Mrs. J. G. Whitman of Owings Mills, Maryland, who reached out to Craig and Tarlton. In a 1982 letter, she enclosed pictures of a related armchair that she wanted to sell (fig. 9). Then, in the mid-1980s, six side chairs with similar splats and feet were sold by Craig and Tarlton (fig. 10). In the course of conducting research, the firm corresponded with noted Maryland collector Bryden Bordley Hyde (1914–2001), who identified two other side chairs of the same design at Winterthur Museum and forwarded information about an armchair in his own collection that had descended in the Sands family of Annapolis (fig. 11).[18] In 2010 Colonial Williamsburg acquired a side chair of the same model as the chair in figure 10 that, like the armchair in figure 11, had a history in the Sands family. The nine side chairs are all from the same set, while subtle variations in the design of the splats and legs of the armchairs suggest that these represent four additional sets. Furthermore, distinctive construction techniques, for which evidence is available for all but two of the armchairs, indicate the practices of a single shop.[19]

Displaying identical design, marking system, and construction, the nine side chairs were originally part of a larger set of at least eighteen. All bear crests and splats of the same pattern, cusped knee returns, front pad feet raised on discs, and chamfered rear legs. The six sold by Craig and Tarlton are numbered 2, 6, 7, 14, 16, and 17 in Roman numerals chiseled onto a two-piece strip of wood applied to the rear rail below the shoe (figs. 12, 13). This method of construction and marking is unusual and distinctive. In addition to providing a surface for marking, the strip also supports the overhang of the two-piece shoe. However, since the glue joint can fail, this strip may not always be present. The pair at Winterthur Museum and the single example at Colonial Williamsburg are numbered 11, 18, and 12 respectively in the same manner.

All of the side chairs are constructed in the same way. Distinctive details include the use of double through-tenons to join the side rails to the rear legs (fig. 14). Single through-tenons are not uncommon in mid-Atlantic furniture, but double through-tenons, with their added complexity, are exceedingly rare. Their manufacture has been fully explored by Dr. Thomas H. Sears Jr., a period woodworker who, with his wife Sara, eventually acquired the set of six offered by Craig and Tarlton for their Greensboro, North Carolina, collection.[20] In the process of reproducing the chairs so as to preserve the originals from the wear and tear of twentieth-century sitters, Dr. Sears became intimately aware of the geometric challenges of cutting a pair of double through-tenons through two planes that are not at ninety degrees to each other; he discovered that the through-tenons were cut at about eleven degrees off perpendicular. The difficulty and expense of crafting even single through-tenons is borne out in period accounts. As cited in William Macpherson Hornor Jr.’s Blue Book, a 1795 Philadelphia cabinetmakers book of prices indicates an extra six pence for “mortising the back feet through” and does not even price a double-tenon option. Hornor further noted that through-, rather than blind, tenons provided greater structural stability and were a more costly option available to the buyer.[21] If their use was based on client demand, it is likely that this feature was not present on all examples of the shop’s output. Indeed, the structural support provided by the double through-tenon may bias the survival rates to those chairs that were made with this costly feature. Nevertheless, the shop evidently favored labor-intensive joinery, even in hidden areas unlikely to have been determined by a buyer’s preferences. X-rays taken by Dr. Sears reveal that double blind-tenons were used in the other seat rail joints, namely the joining of the front and side rails to the front legs and the rear rails to the rear legs (fig. 15). Another notable detail is the undercut shaping to the rear seat rails (fig. 12). Where they survive, the original slip-seat frames are lap-joined, secured with a wrought nail at each joint, and marked with Roman numerals corresponding to those on the chair frames.

Recently examined by the author, the armchair in figure 11 displays a slightly variant splat—with an extra pierced void in the base—and features unusual hooped arms, which are through-tenoned to the stiles (fig. 16); otherwise, its design and construction conform to the practices seen on the side chairs, with a Roman numeral VI on the strip attached to the rear rail, and can be firmly ascribed to the same shop. The current whereabouts of the Brice family armchair in figure 5 and those in figures 8 and 9 are unknown. With incomplete evidence of their construction and the originality of component parts, these three armchairs stand as possible outputs of the same shop. As discerned from photographs, all display arms of different designs, while the splats on the chairs in figures 8 and 9 vary from the others with a less elongated carrot-shaped void in the lower sections. The Brice family armchair also features scrolled knee returns and rear legs with club feet, unlike the cusped returns and chamfered legs seen on all other chairs from this group. Additional photographs of the armchair in figure 9 reveal that it has a shaped rear rail with attached strip, as seen on the side chairs and armchair in figures 10 and 11, but lacks the through-tenons joining the side rails to the rear legs.

Working outward from the core group, a slightly larger body of related work can be attributed to the same shop [or to closely allied craftsmen familiar with its practices]. A side chair with double through-tenons and identical pad feet, shaped rear rail, and chamfered back legs—but with a radically different splat and crest rail design—was discovered by Dr. Sears and is now in the collections of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (figs. 17, 18). This chair also includes the same idiosyncratic application of a small two-part strip of wood below the shoe where it overhangs the rear rail. A mahogany armchair with double through-tenons and similar front feet with pronounced ankles and scribed tops was discovered by decorative arts scholar Sumpter Priddy (fig. 19). Its arm terminals relate to the Brice family armchair in figure 5, and its feet are virtually identical to those on the other chairs but with a molded, rather than straight, underfoot pad. Such variation, especially on elements like an underfoot pad that were not particularly visible, suggests a shop with multiple workers, including apprentices, journeymen, and enslaved craftsmen. A dressing table with this same foot-pad variation is also known (figs. 20, 21).

Though made in Annapolis, the design of these chairs speaks to the close connection between Maryland and the British Isles, particularly Ireland. The pierced vasiform splat and baroque crest rail of these chairs are closely related to the splats and crest rails on mid-eighteenth-century chairs made in Dublin, Ireland. Examples survive in the collection at Glin Castle, and a large number of simpler Irish chairs with related splats and crest rails have also been identified (fig. 22).[22] The sheer number of surviving chairs with variations of the same design suggests that this was a popular mid-eighteenth-century design in Annapolis. This may be explained by Maryland’s close connections with Ireland through both kinship and commerce. Though figures for Annapolis are not available, forty percent of neighboring Baltimore’s significant wheat exports in the period before the Revolution went to Irish ports. In return came Irish goods and Irish indentured servants, some of them craftsmen.[23] Just as significant were family ties with Ireland. Originally founded as a refuge for Catholics by Cecil Calvert, Lord Baltimore (1605–1675), Maryland attracted many Irish Catholic settlers during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Among the most significant was the powerful and wealthy Carroll family. Charles Carroll (1661–1720) arrived in Maryland in about 1689 and emphasized his Gaelic roots to his son, Charles Carroll (1702–1782) of Annapolis, by insisting that the boy, who was abroad at school, “Stile your Self in your Thesis Marylando-Hibernus.”[24] With their strong Irish identity and incredible wealth, the Carrolls were in a perfect position to influence the development of an Annapolis furniture style that spoke with an Irish brogue.

In addition to the Brice family armchair, three of the chairs from this group have early histories linked to Annapolis. The armchair in figure 19 retains an ink inscription, “Randall,” on its original yellow pine slip-seat frame, likely penned by an upholsterer. Sumpter Priddy has suggested that this chair was once the property of John Randall (1750–1826), a Virginia-born cabinetmaker and joiner who accompanied British-trained architect William Buckland (1734–1774) to Annapolis in the early 1770s. Born in 1750, Randall was probably the second owner of this chair.[25] The dressing table in figure 20, with the same foot design as the Randall chair, has a provenance in the Chamberlaine family of Bonfield, in Talbot County on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. The Chamberlaines were closely connected to Annapolis through government service.[26]

As mentioned above, the armchair in figure 11 and the side chair at Colonial Williamsburg both have histories in the Sands House on Prince George Street. John Sands (1731–1791), a mariner, acquired the house in 1771.[27] It is not clear when the Sands family first arrived in Annapolis. However, even if they had been in Annapolis at the time that these chairs were made, the family’s relative socioeconomic position in the eighteenth century compared to the Brice family suggests that they could not have afforded such elaborate chairs at the time. When John Sands died in 1791 his estate was valued at $310; by comparison, James Brice’s 1802 estate was valued at nearly $1,600.[28] However, while most of the well-to-do families of eighteenth-century Annapolis died out or left the city in the 1800s, the Sands family remained, and by the nineteenth century its descendants were in an ideal position to acquire locally made “antiques.” The house that John Sands purchased on Prince George Street in 1771 remained a family home through six generations of family ownership, and when it was sold out of the family in 2015, it was a time capsule of Annapolis material culture (fig. 23).[29]

The nine side chairs from this shop are particularly notable in that they were, based on their numbering, once part of a set of at least eighteen, a remarkably large number for a single commission. One of the few places in colonial America where supersized sets of chairs appeared with some regularity was in government service, either in legislative chambers or in the households of royal governors.[30] There is no documentation of the furnishings of Maryland’s statehouse during the middle of the eighteenth century, but several decades later the new statehouse, constructed between 1772 and 1779 and greatly refurbished between 1778 and 1795, included a commission for twenty-four armchairs for the Senate chamber.[31] Maryland’s governors during the years when the chairs likely were made were Samuel Ogle (ca. 1694–1752) and Horatio Sharpe (1718–1790) (fig. 24). In 1742 Maryland’s state legislature had authorized construction on an ambitious governor’s residence, but the project was badly mismanaged and never completed.[32] Thus, the governors had to procure their own residences. During his last term, from 1747 to 1752, Ogle leased a Georgian brick mansion, later known as Ogle Hall, at 247 King George Street (fig. 25). A partial inventory of his estate, taken in 1755, survives, with several references to mahogany, or “common,” chairs but no listing that appears to describe the large set of walnut side chairs.[33]

Sharpe was appointed Ogle’s successor in 1752 and arrived in Annapolis on August 10, 1753. Upon his arrival, Sharpe rented the recently completed house of Edmund Jennings (1703–1756), who had left the colony and resettled in England in the same year (fig. 26).[34] Jennings’ step-daughter, Sarah (Frisby) Brice (1714–1782), was the wife of Judge John Brice, who may have owned the armchair in figure 5. If this armchair and the set of side chairs were made in the same shop, then Jennings stands as a possible link between the two commissions. He may have patronized the same craftsman as the Brices had—or directed Sharpe to do so. There is no inventory or other evidence for the furnishings during Sharpe’s residence. However, Sharpe’s successor, Robert Eden (1741–1784), rented and refurnished the same house. An inventory taken in 1776 reveals that Eden left behind more than forty chairs, including a set of “14 Mahogony Chairs with horsehair Bottoms” in the right-hand parlor of his house in Annapolis and a set of “16 Maho: Chairs with horsehair Bottoms” in the Long Room.[35] Sharpe’s own personal furnishings presumably left office with him, and some may have been installed at his newly built country estate, Whitehall, just outside of Annapolis.[36] It is also likely that much of Sharpe’s governor-era furnishings eventually found its way onto the market, where people like John Sands—who acquired his house on Prince George Street just as Sharpe was moving out—purchased them.

None of the known pieces from this shop has a direct connection to a particular craftsperson. The MESDA Craftsman Database has identified four men associated with the cabinetmaking or chairmaking trade in Annapolis during the period between 1745 and 1760, when the chairs in this group likely were made: John Anderson (d. 1759); Gamaliel Butler (d. 1756); Robert Harsnip (d. 1762); and John Pennington (d. 1750). For Butler, the cabinet trade appears to have been a temporary line of business undertaken by an unknown craftsperson whom he employed in 1754; his primary trade, born out by advertisements and his 1756 probate inventory, was block making.[37] Robert Harsnip could have been the maker of this group, but virtually nothing is known of his time in Annapolis aside from what was published in the Maryland Gazette: while “Robert Harsnip, a Cabinet-Maker, was standing under the Gallows, and giving Directions for the fixing of the Cross-Piece, it fell, and struck him upon the head, by which he was so much hurt that he died the next Morning.”[38] John Pennington is another possible candidate. On July 18, 1750, he advised his patrons through the Maryland Gazette that he planned “very soon to leave this province and return to his native country, England,” and that he desired to put his affairs in order. He died before he could put his plan in motion; on December 21, 1750, Jonas Green and Simon Duff produced a probate inventory of “the sundry goods . . . belonging to the Estate of Mr. John Pennington a very Ingenious Cabinet Maker late of Annapolis.” His inventory includes “Eleven half-finished tea chests . . . and a large Parcel of half-finished dove Tail drawers.”[39]

Of these four men, then, John Anderson is the most likely candidate based on his working dates and what is known from the historical record.[40] Anderson was probably born in 1723 to John (d. 1736) and Margaret Anderson of St. Elphin in Warrington, Lancashire, located on the River Mersey just nineteen miles inland from Liverpool. John’s father is identified as a cabinetmaker in 1717, when he took on an apprentice, and in the St. Elphin parish records upon both his son’s baptism in December 1723 and his own death in 1736. The younger John was thirteen years old when his father died, about the age when he would have begun an apprenticeship.[41] Ten years later, in 1746, he arrived in Annapolis, where he was quick to let prospective clients know that he was, “late from Liverpool,” and prepared to offer, “all Kinds of Furniture which is made of Wood, belonging to a House; in the neatest, cheapest, and newest Mode.”[42] Anderson’s roots may account for some of the features seen in this group of Annapolis chairs. Liverpool, just across the Irish sea from Dublin, was the primary port of entry for exports from Ireland to England. Furthermore, in his discussion of through-tenon joinery, Hornor singled out Lancashire as a place where this method was used.[43]

Anderson apparently met with success in Annapolis. Within months of his arrival he sought to purchase planks of various woods, and by 1750 he had his own house on South East Street. Four years later he advertised that he had moved to new and more prominent quarters “fronting the Parade,” where he now kept a tavern in addition to being able to “furnish any Gentlemen with all Sorts of Cabinet Work . . . for ready Money, Pine, Poplar, or Walnut Plank . . . .” He advertised an elaborate billiards table in 1755, perhaps a bespoke commission where the sale had fallen through, and two years later he moved again to “a new and commodious House” on Market Place. Soon after his death in 1759, his widow, Mary, advertised the sale of cabinetmaker’s tools and “a Quantity of choice well-seasoned MAHOGANY and WALNUT PLANK.”[44] His thirteen years in Annapolis were long enough for him to make a great deal of furniture, but he was not quite long-lived enough to participate in Annapolis’s inter-bellum boom years. His death in 1759 paved the way for a cabinetmaker like John Shaw to monopolize Annapolis furniture making in the later eighteenth century.

Between 1694, when it became the capitol of Maryland, and the beginning of the American Revolution in 1775, Annapolis was one of the principal cities of the Chesapeake Bay region. Annapolis’s wealthiest families turned to London-trained architects for the construction of their grand houses, and they turned to a combination of local and international craftspeople to furnish them. It is no coincidence that William Buckland, after completing the terms of his indenture on Virginia’s Northern Neck, made his way to Annapolis, where he was responsible for the Chase-Lloyd House, the Hammond-Harwood House, and the James Brice House (fig. 4).[45] Despite the survival of many eighteenth-century buildings—and outside of the cabinetwork of John Shaw and the silverwork of William Faris (1728–1804)—little is known about the objects that filled these houses or the craftspeople, be they free, indentured, or enslaved, who were responsible for their manufacture. As Chesapeake commerce realigned towards the western lands, especially those drained by the Susquehanna River, Baltimore grew at a faster rate than any other Chesapeake city, and its artisanal community also grew at an exponential rate (fig. 7). As the Frenchman François-Alexandre-Frédéric duc de La Rochefoucauld-Liancourt (1747–1827) observed in the late 1790s:

Annapolis was formerly the principal city of Maryland, and there was some commerce carried on there. Since the revolution it retains the name of the metropolis of the state, and continues to be the seat of government, but Baltimore has drawn all the commerce from it. The capitalists, or those who would become such, have quitted it to go and reside at Baltimore.[46]

The dominance of Philadelphia, and subsequently Baltimore, within mid-Atlantic decorative arts scholarship has obscured the contributions made by the mid-eighteenth-century furniture makers in Annapolis. It is hoped that this article will bring a better understanding of the locally made forms that once filled Annapolis’s eighteenth-century structures.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This article is in memory of Sara Sears and in honor of Dr. Thomas H. Sears Jr., who generously shared their six chairs, research, knowledge, and enthusiasm, and without whom this article would not have been possible.

Ebenezer Cooke, The Sot-Weed Factor, or, A Voyage to Maryland. A Satyr. (London, 1708), pp. 24–25.

For a detailed discussion of Herrman’s map, see Christian J. Koot, A Biography of a Map in Motion: Augustine Herrman’s Chesapeake (New York: New York University Press, 2018).

For more about the rationale for moving Maryland’s capital to Annapolis, see Jane Wilson McWilliams, Annapolis, City on the Severn: A History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011), pp. 16–23.

Ebenezer Cooke, Sotweed Redivivus, or, The Planters Looking-Glass. In Burlesque Verse. Calculated for the Meridian of Maryland (Annapolis, 1730), p. 1.

Edward C. Papenfuse et al., A Biographical Dictionary of the Maryland Legislature, 1635–1789, vol. 1, A-H (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1979), pp. 164–65.

Edward Chappell and the Maryland Historical Trust Vernacular Architecture Forum (U.S.), Architecture in Annapolis: A Field Guide (Crownsville, Md.: Vernacular Architecture Forum and the Maryland Historical Trust Press, 1998), pp. 44–46.

“An Inventory of the Goods and Chattles of John Brice Esq.,” May 1, 1767, vol. 97, pp. 180–85, Prerogative Court (Inventories), S534, Maryland State Archives. Also available online: Maryland, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1635–1777 (database), Ancestry.com, https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/9068/.

“Inventory and appraisement of the Goods Chattels and personal Estate of James Brice Esquire,” May 25, 1802, vol. JG5, pp. 367–71, Anne Arundel County Register of Wills (Inventories, 1799–1804), C88-8, Maryland State Archives. Also available online: “Maryland, Register of Wills Records, 1629–1999,” FamilySearch.com, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9TPN-9KC3?wc=SNYW-2N5%3A146534401%2C146804001%26cc%3D1803986&lang=en&i=190/.

“Furniture from Brice House, Annapolis: Now in the Collection of Mrs. Breckenridge Long, at Laurel, Maryland,” Antiques 27, no. 1 (January 1935): 13.

Baltimore Furniture: The Work of Baltimore and Annapolis Cabinetmakers from 1760 to 1810 (Baltimore: Baltimore Museum of Art, 1947), pp. 9, 15, 168.

William Voss Elder III, Maryland Queen Anne and Chippendale Furniture of the Eighteenth Century (Baltimore: Baltimore Museum of Art, 1968); Gregory R. Weidman, Furniture in Maryland 1740–1940: The Collection of the Maryland Historical Society (Baltimore: Maryland Historical Society, 1984).

John Shaw was born in Glasgow, Scotland, in 1745, and he may have been in Annapolis as early as 1763. His shop, at times in partnership with other cabinetmakers, remained active into the 1820s. To date, more than fifty labeled examples of his shop’s output are known. See William Voss Elder III and Lu Bartlett, John Shaw: Cabinetmaker of Annapolis (Baltimore: Baltimore Museum of Art, 1983), pp. 13–14, 20–24.

Only one other eighteenth-century Annapolis craftsperson, silversmith William Faris (1728–1804), has received this level of study. See William Faris, The Diary of William Faris: The Daily Life of an Annapolis Silversmith, edited by Mark B. Letzer and Jean B. Russo (Baltimore: Maryland Center for History and Culture, 2003).

MESDA Craftsman Database, MESDA Research Center, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, https://mesda.org/research/craftsman-database/. These numbers are derived from searches on the database for joiners, cabinetmakers, and carpenters working in Annapolis and Anne Arundel County, Maryland, before 1780.

Baltimore Furniture, p. 13.

Elder, Maryland Queen Anne and Chippendale Furniture, p. 7.

“Craig and Tarlton Advertisement,” Antiques 117, no. 1 (January 1980): 133.

Joe E. A. Wilkinson, letter to Bryden Bordley Hyde, February 14, 1985, MESDA Research Center. At the time of this correspondence, Hyde’s chair had been altered with later inlay, and the arms were considered suspect. Conservation by Alan Anderson in 2019 removed the later inlay and also determined that the arms were original to the chair. See MESDA Object Database, photo number D-34111 and associated materials in file S-13509, https://mesda.org/collection/object/.

The images Mrs. Whitman sent to Craig and Tarlton show the armchair in fig. 9 from multiple angles. Unfortunately, the armchair in fig. 5 published by Antiques in 1935 and the armchair in fig. 8 advertised by Craig and Tarlton in 1980 are currently unlocated.

For a survey of the Sears collection, see June Lucas, “Teamwork in Piedmont North Carolina,” Antiques 179, no. 2 (March–April 2012): 146–53.

William Macpherson Hornor Jr., Blue Book, Philadelphia Furniture: William Penn to George Washington (Philadelphia: Published by the author, 1935), p. 207. See also The Journeymen Cabinet and Chair-Makers Philadelphia Book of Prices (Philadelphia, 1795).

The pair represented by the example in fig. 23, along with another related armchair, are illustrated in Knight of Glin and James Peill, Irish Furniture: Woodwork and Carving in Ireland from the Earliest Times to the Act of Union (New Haven, Conn.: Published for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art by Yale University Press, 2007), pp. 106–7, figs. 135–36; a set with a history at Carton House, the seat of the Earls of Kildare and the Dukes of Leinster in County Kildare, Ireland, was sold at auction in 2013: The Fine Art Sale (Part 2) (Cambridge, England: Cheffins, September 19, 2013), lot 890; see also Country Collections at Slane Castle (Dublin, Ireland: James Adam and Sons Ltd., October 9, 2012), lot 149; F. Lewis Hinckley, A Directory of Queen Anne, Early Georgian, and Chippendale Furniture: Establishing the Preeminence of the Dublin Craftsmen (New York: Crown, 1971), figs. 263, 266, 267.

Thomas M. Truxes, Irish-American Trade, 1660–1783 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1988), p. 123.

Ronald Hoffman and Sally D. Mason, Princes of Ireland, Planters of Maryland: A Carroll Saga, 1500-1782 (Chapel Hill: Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture and the University of North Carolina Press, 2000), p. 97.

“Randall Family Carved Baroque Armchair FR2016042” (unpublished report, Sumpter Priddy III, Inc., Alexandria, Va., n.d.).

Bonfield was built about 1772 for the marriage of Samuel Chamberlaine Jr. (1742–1811) and Henrietta Maria Hollyday (1750–1832). The table was likely made for the previous generation, possibly his parents, Samuel Chamberlaine Sr. (1697–1773) and Henrietta Maria Lloyd (1710–1748), who married in 1729, or her parents, Henry Hollyday (1725–1789) and Anna Marie Robbins (1731–1804), who married in 1750. Henry Hollyday briefly served in several public offices but primarily concerned himself with the oversight of Ratcliffe Manor, a plantation and elaborate house built about 1750. Samuel Chamberlaine Sr., by contrast, was a factor and partner in several Liverpool-based mercantile firms, a shipowner, and a member of the Maryland Legislature at Annapolis between 1728 and 1768. He also served as the collector of customs for the Port of Oxford and Pocomoke for several decades before he was succeeded by his son, Samuel, in whose family the dressing table descended. For detailed biographical information, see Edward C. Papenfuse et al., A Biographical Dictionary of the Maryland Legislature, 1: passim.

Calder Loth, “Sands House,” National Register of Historic Places Nomination, 1973, United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, AA-652.

“An Inventory of the Goods and Chattles of John Sands,” n.d. [May 1791], vol. JG2, pp. 80–85, Anne Arundel County Register of Wills (Inventories, 1790–1792), C88-5, Maryland State Archives. Also available online: “Maryland, Register of Wills Records, 1629–1999,” FamilySearch.com, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GTR9-9Z9B?wc=SNYW-T3J%3A146534401%2C146785201%26cc%3D1803986&lang=en&i=41. See note 8.

Kathy Orton, “This Wooden House Grew Old with Annapolis,” Washington Post, June 14, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/realestate/this-wooden-house-grew-old-with-annapolis/2019/06/13/cc75f714-8a1e-11e9-a870-b9c411dc4312_story.html, accessed December 20, 2023. The photograph illustrated in fig. 23 is among the papers filed with the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, Maryland Historical Trust, Sands House, AA-652, available at https://apps.mht.maryland.gov/medusa/PDF/AnneArundel/AA-652.pdf.

An example of the latter is the 1770 inventory of the governor’s residence in Williamsburg, Virginia, after the death of Lord Botetourt. Included were “19 Leather Bottom Mahogany chairs” among the standing furniture of the Ball Room and “16 Walnut Leather bottom chairs” among the standing furniture of the Supper Room. See Graham Hood, The Governor’s Palace in Williamsburg: A Cultural Study (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, distributed by University of North Carolina Press, 1991), Appendix 1. There were undoubtedly more large sets in private households than is readily apparent today; this kind of archival assertion is biased based on the survival of records. Moreover, inventories are imperfect sources. There is little standardization in probate inventories, and a large set of chairs might well have been split among entries. For example, it is possible that the thirteen chairs in Judge John Brice’s dining room and the six chairs in his passage cited in his probate inventory represent a single set. See note 7.

Elder and Bartlett, John Shaw, pp. 126–27.

Morris L. Radoff, Buildings of the State of Maryland at Annapolis, Hall of Records Commission 9 (Annapolis: State of Maryland, 1954), pp. 77–79.

For a transcription of the partial inventory, see “Inventory of Items Owned by Gov. Samuel Ogle,” Ogle Family of Maryland and Allied Families.com, accessed September 20, 2024, https://www.oglefamilyofmarylandandalliedfamilies.com/inventory_of_items_owned_by_gov.htm.

Radoff, Buildings of the State of Maryland, pp. 71–72.

Hood, The Governor’s Palace, Appendix 1, Appendix 5.

For a history of Whitehall, see Charles Scarlett Jr., “Governor Horatio Sharpe’s Whitehall,” Maryland Historical Magazine 46 (1951): 8–26. There is no inventory for the furnishings that were left in the house when Sharpe returned to England, and because his property was never seized by the Maryland government—a testament to his close relationship with the state’s elite—there is no loyalist claim for the property.

See record for Gamaliel Butler, MESDA Craftsman Database, Craftsman ID 5010, accessed December 20, 2023, https://mesda.org/item/craftsman/butler-gamaliel/4982/.

See record for Robert Harsnip, MESDA Craftsman Database, Craftsman ID 15473, accessed December 20, 2023, https://mesda.org/item/craftsman/harsnip-robert/15403/.

See record for John Pennington, MESDA Craftsman Database, Craftsman ID 28197, accessed December 20, 2023, https://mesda.org/item/craftsman/pennington-john/28069/.

See record for John Anderson, MESDA Craftsman Database, Craftsman ID 581, accessed December 20, 2023, https://mesda.org/item/craftsman/anderson-john/579/.

See records for John Anderson in: St. Elphin, Warrington, Lancashire Online Parish Clerk Project (database), accessed December 20, 2023, https://lan-opc.org.uk/; UK Register of Duties Paid for Apprentices’ Indentures, 1710–1811 (database), Ancestry.com, accessed September 18, 2024, https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/1851/; Cheshire, England, Church of England Baptisms, Marriages and Burials, 1538–1812 (database), Ancestry.com, accessed September 18, 2024, https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/62254/. The St. Elphin parish registers also record the marriage of a John Anderson and Mary Grantham in 1717, as well as the baptism of a John Anderson, son of widow Mary, in March 1723/24. These are most likely different individuals from those in the Annapolis cabinetmaker’s family.

Maryland Gazette, October 21, 1746; January 6, 1747; August 8, 1750; July 11, 1754; June 19, 1755; January 13, 1757; May 17, 1759, all cited in MESDA Craftsman Database.

Hornor, Blue Book, p. 207.

Maryland Gazette, January 6, 1747; August 8, 1750; July 11, 1754; June 19, 1755; January 13, 1757; May 17, 1759, all cited in MESDA Craftsman Database.

For Buckland’s work, see Rosamond Randall Beirne and John H. Scarff, William Buckland, 1734–1774: Architect of Virginia and Maryland (Baltimore: Maryland Historical Society, 1958); Luke Beckerdite, “William Buckland and William Bernard Sears: The Designer and the Carver,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 8, no. 2 (November 1982): 7–42; ———, “Architect-Designed Furniture in Eighteenth-Century Virginia: The Work of William Buckland and William Bernard Sears,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Milwaukee, Wis.: Chipstone Foundation, 1994), pp. 28–48.

François-Alexandre-Frédéric duc de La Rochefoucauld-Liancourt, Travels through the United States of North America: The Country of the Iroquois, and Upper Canada, in the Years 1795, 1796, and 1797, 2nd ed. (London: R. Phillips, 1800), pp. 580–81.