Card table, attributed to the shop of John and Hugh Finlay, Baltimore, Maryland, ca. 1815. Mahogany, tulip poplar, maple; painted and gilded decoration, baize, brass. H. 28 1/2", W. 36", D. 17 3/4". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art, gift of the Stanley Weiss Collection in recognition of the scholarship of Alexandra Kirtley, Curator of American Decorative Arts, 2018; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

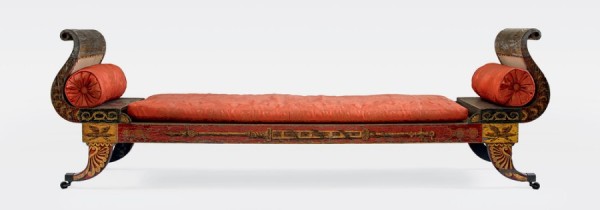

Recess seat, Hugh Finlay and Co., Baltimore, ca. 1825. Tulip poplar; gilt, metal, brass, paint. H. 16 1/4", W. 45", D. 14 1/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library, Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont.) This recess (or window) seat, one of a pair, is from the suite of furniture made for James Wilson.

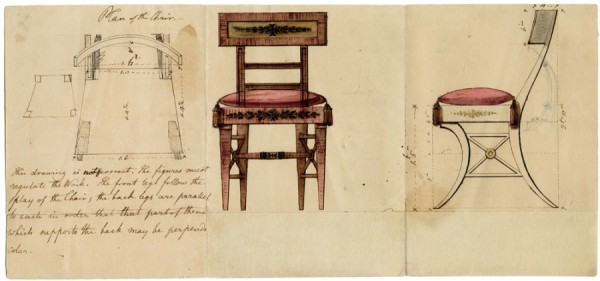

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, drawing for a chair for the President’s House, 1809. Watercolor on paper. (Courtesy, Maryland Center for History and Culture.)

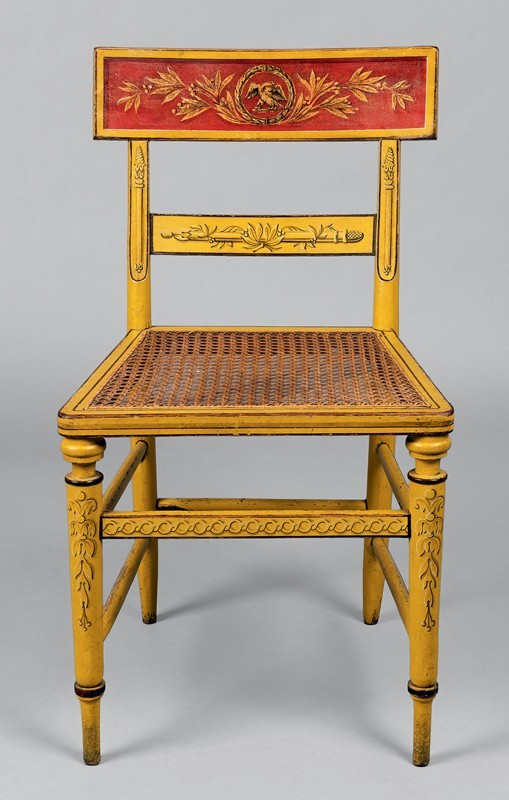

Armchair, attributed to the shop of John and Hugh Finlay, with crest rail medallion attributed to Francis Guy, Baltimore, 1803–1805. Maple and ash; painted and gilded decoration. H. 33 3/4", W. 21 5/8", D. 20 5/16". (Courtesy, Baltimore Museum of Art, gift of Lydia Howard de Roth and Nancy H. DeFord Venable in Memory of their Mother, Lydia Howard DeFord and Purchase Fund; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chair is from the “Morris” suite; its crest rail medallion depicts the St. Paul’s Charity School.

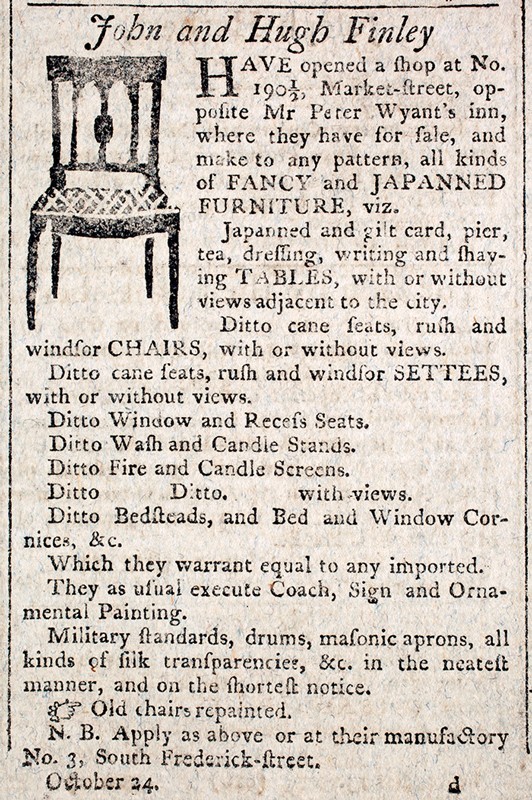

Advertisement by John and Hugh Finlay in the October 24, 1803, issue of the Federal Gazette & Baltimore Daily Advertiser. (Courtesy, Maryland Center for History and Culture.) This advertisement shows a chair of the form of those from the “Morris” suite illustrated in fig. 4. It indicates that from an early date the Finlays offered a wide variety of furniture forms and services.

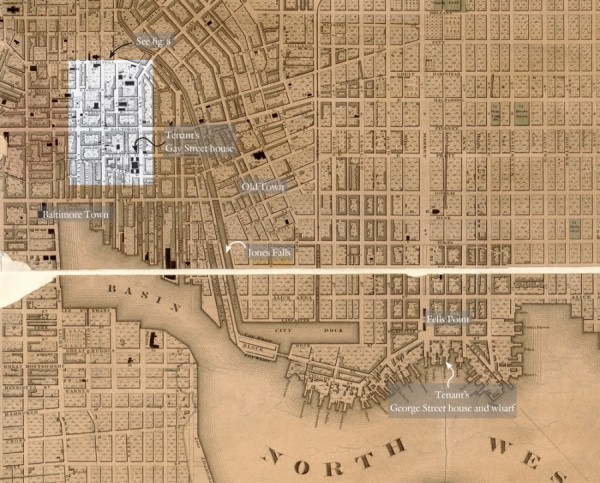

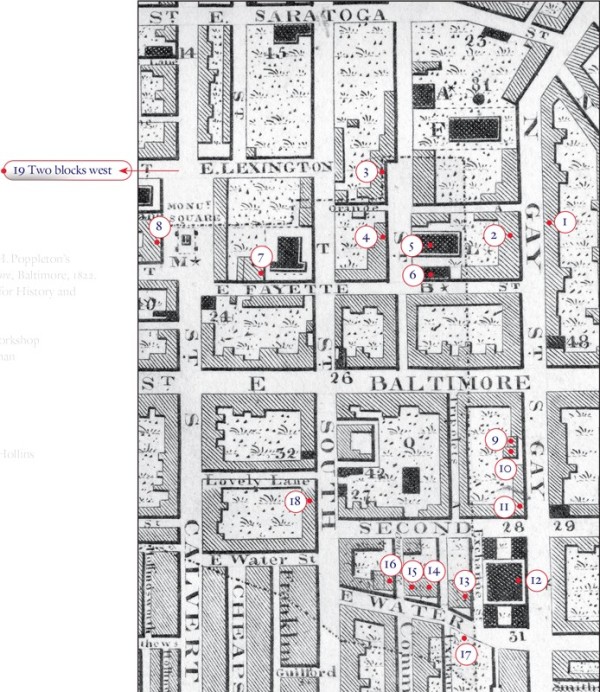

Detail of Thomas H. Poppleton’s This Plan of the City of Baltimore, Baltimore, 1822. (Courtesy, Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress.) This map shows the town’s three early areas: Baltimore Town, on the west side of the Jones Falls, and Old Town and Fells Point on the east side. See fig. 8 for detail of the Gay Street area.

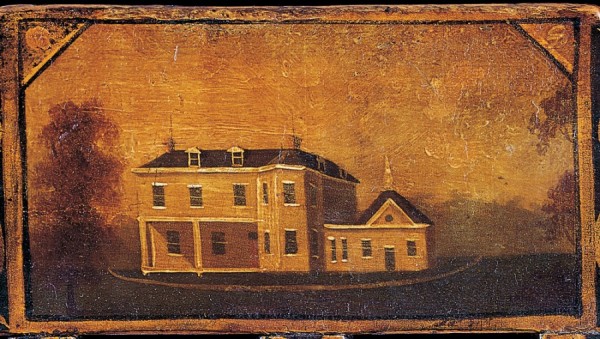

Detail of a side chair attributed to the shop of John and Hugh Finlay, with crest rail medallion attributed to Francis Guy, Baltimore, 1803–1806. Woods not recorded; painted and gilded decoration. H. 34 1/4", W. 17 1/2", D. 15 3/4". (Courtesy, Baltimore Museum of Art, Middendorf Foundation Fund; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The house is Belmont, purchased by Thomas Tenant from Archibald Campbell in 1805. For an image of the chair, see Humphries, “Patronage, Provenance, and Perception,” in American Furniture (2003), p. 173, fig. 42.

Detail of Thomas H. Poppleton’s This Plan of the City of Baltimore, Baltimore, 1822. (Courtesy, Maryland Center for History and Culture.)

1. John and Hugh Finlay Workshop

2. Sydney and Peggy Buchanan

3. James Wilson

4. Alexander Brown

5. Holliday Street Theatre

6. Assembly Rooms

7. Lemuel Taylor

8. James Buchanan & John Hollins

9. Roswell L. Colt

10. Robert Oliver

11. Thomas Tenant

12. Merchants Exchange

13. Cumberland Dugan

14. Samuel Smith

15. Robert Gilmor Sr.

16. John Donnell

17. Robert Gilmor Jr.

18. William Patterson

19. William Lorman

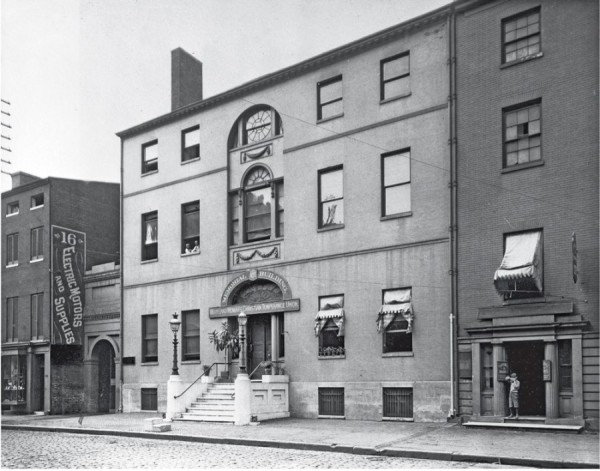

Robert Oliver’s mansion on Gay Street, Baltimore. Photograph, ca. 1900. (Courtesy, Maryland Center for History and Culture.) This photograph illustrates several features not present at the time the house was built in 1805–1807. The marble stoop probably dates from the 1830s or 1840s and likely replaced simple marble cascading steps with an iron railing. The original multi-pane windows have been replaced with large sheets of glass. To the right is a partial view of the house Oliver built next door for his daughter and her husband, Roswell Lyman Colt. Thomas Tenant’s house was several houses south of those depicted.

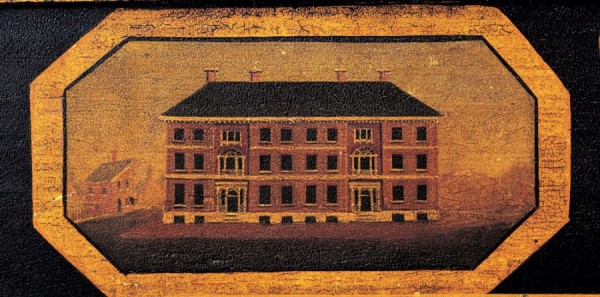

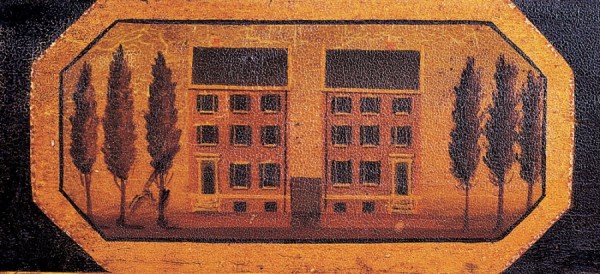

Detail of a card table attributed to the shop of John and Hugh Finlay, with skirt medallion attributed to Francis Guy, Baltimore, 1803–1806. Tulip poplar and pine with oak. H. 28 3/4", W. 38 5/8", D. 17 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, Library & Garden.) This medallion depicts the paired mansions built in 1799–1801 by James A. Buchanan (left) and John Hollins (right). The card table was part of a suite made for Buchanan’s sisters, Sydney and Peggy Buchanan, who lived on Gay Street. For an image of the table, see Humphries, “Patronage, Provenance, and Perception,” in American Furniture (2003), p. 162, fig. 32.

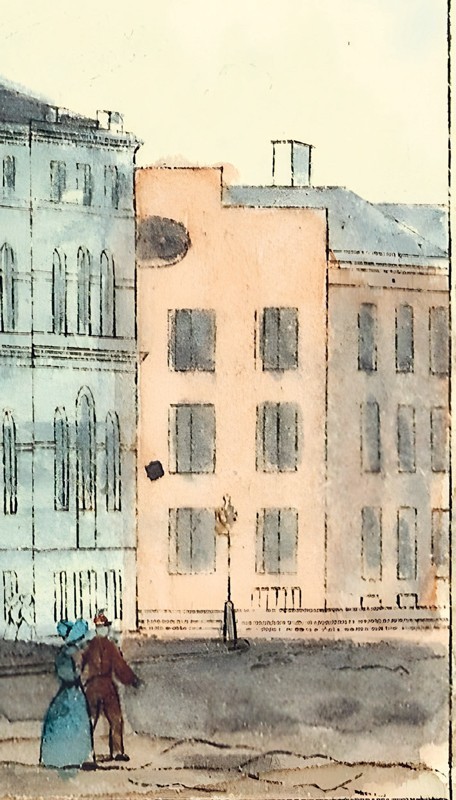

Detail of a plate illustrated opposite p. 95 in John H. B. Latrobe’s Picture of Baltimore (1832). (Courtesy, Johns Hopkins Digital Library/Wikimedia Commons.) The larger plate is a view of the Merchants Exchange looking north on Gay Street. As seen in the detail shown here, Thomas Tenant’s three-bay house on the northwest corner of Gay and Second (modern Water) Streets had windows on its south-facing facade.

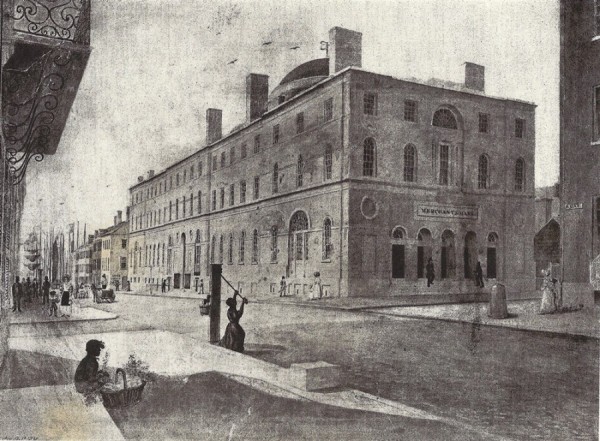

A view of the Merchants Exchange, ca. 1830s. Watercolor. Unlocated. Illustrated opposite p. 12 in The Savings Bank of Baltimore: One Hundred Years of Service 1818–1918 (1918). This view shows the Merchants Exchange as seen looking south on Gay Street towards Baltimore’s harbor. Second (modern Water) Street is in the foreground, and on the right is the corner of Thomas Tenant’s mansion. John H. B. Latrobe later described the area near this intersection as the “fashionable centre of the town.”

Pier table, attributed to the shop of John and Hugh Finlay, with skirt medallion attributed to Francis Guy, Baltimore, 1803–1806. Yellow pine, tulip poplar, maple; painted and gilded decoration. H. 35 7/8", W. 45 1/8", D. 20". (Courtesy, Baltimore Museum of Art, purchase with exchange funds from The George C. Jenkins Fund; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This pier table was the centerpiece of a suite made for sisters Sydney and Peggy Buchanan, who lived on Gay Street.

Detail of the table in fig. 13. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The table’s decoration depicts the paired houses on Gay Street built for the Buchanan sisters. Sydney and Peggy Buchanan lived in the house on the right, and this pier table was, according to an inventory, located in the first floor front parlor. It was likely displayed between the two windows to the left of the door. Their sister Mary (Buchanan) Allison lived in the house on the left.

Card table, attributed to the shop of John and Hugh Finlay, Baltimore, ca. 1815. Mahogany, poplar, and other woods. H. 28 3/8", W. 36 1/8", D. 37 7/8" (open). (Private collection; photo, Antiques.) One of a pair, this table is part of the suite of furniture made for Alexander Brown.

Side chair by John King, with miniature portrait of the marquis de Lafayette by Joseph Weisman, Baltimore, 1824. Unidentified wood; painted and gilded decoration. H. 30 1/2", W. 17 3/4", D. 15 3/8". (Courtesy, Baltimore Museum of Art, gift of Randolph Mordecai; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Pier table by Hugh Finlay and Co., with miniature portrait of the marquis de Lafayette by Joseph Weisman, Baltimore, 1824. Unidentified wood; painted decoration, and iron. H. 31 3/4", W. 49 1/8", D. 23 1/4". (Courtesy, Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, Va., gift of Dr. and Mrs. C. Frederic Fluhmann.)

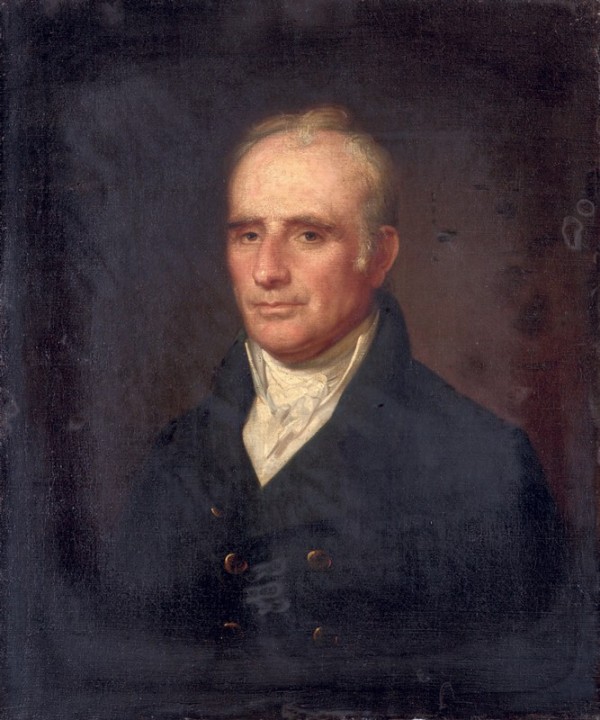

Rembrandt Peale, Robert Oliver, 1809. Oil on canvas. H. 30 1/8", W. 25 1/4". (Courtesy, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Conn., bequest of Miss Mary Wagstaff in memory of her mother, Amy Colt [Mrs. Cornelius DuBois Wagstaff]; photo, Allen Phillips/Wadsworth Atheneum.)

Sir Thomas Lawrence, Robert Gilmor Jr., 1818–1820. Oil on canvas. H. 30 5/8", W. 25 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Michael Bodycomb.)

Gilbert Stuart, Samuel Smith, ca. 1800. Oil on canvas. H. 29 1/4", W. 24 3/8". (Courtesy, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, gift of Dr. and Mrs. B. Noland Carter in memory of the Misses Mary Coles Carter and Sally Randolph Carter.)

Armchair, attributed to Charles-Honoré Lannuier, New York, New York, ca. 1810–1819. Mahogany and maple. H. 35 1/2", W. 22", D. 20 1/2". (Courtesy, Maryland Center for History and Culture, bequest of J. B. Noel Wyatt.) New research suggests this chair and its suite, long thought to have been made for James Bosley, was first owned by Lemuel Taylor, with whom Thomas Tenant was in business.

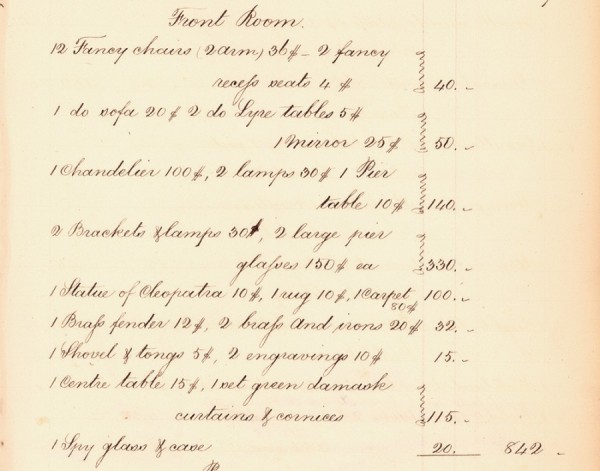

Detail of Thomas Tenant’s Inventory, February 3, 1836. (Courtesy, Maryland State Archives.) The illustrated portion records the furnishings of Thomas Tenant’s first-floor “Front Room” or parlor and begins with the painted suite. The “2 do [fancy] Lyre tables” are later described as card tables in Thomas Tenant’s Account of Sales, December 7, 1842 (see Appendix, cat. 12).

Armchair, attributed to the shop of John and Hugh Finlay, Baltimore, ca. 1815. Poplar, pine. H. 31 3/4", W. 21 3/4", D. 22 7/8". (Courtesy, Missouri Historical Society, Saint Louis, gift of Mrs. Charles Chambers Thatcher.)

Armchair, attributed to the shop of John and Hugh Finlay, Baltimore, ca. 1815. Poplar, cherry, pine. H. 31 7/8", W. 21 3/4", D. 22 3/4". (Courtesy, Missouri Historical Society, Saint Louis, gift of Mrs. Charles Chambers Thatcher.) This chair was previously fitted with the applied cornucopia ornaments on the sides of the arm supports as seen on the chair in fig. 23. These were removed during conservation in the 1990s and are now stored separately (see Appendix, cat. 2).

Side chair, attributed to the shop of John and Hugh Finlay, Baltimore, ca. 1815. Cherry, maple, tulip poplar, pine. H. 31 7/8", W. 20", D. 21 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library, Museum purchase with funds provided by the Special Fund for Collection Objects.)

Recess seat, attributed to the shop of John and Hugh Finlay, Baltimore, ca. 1815. Pine, yellow poplar; painted and gilded decoration, brass, reproduction wool damask upholstery. H. 15 5/8", W. 46 1/16", D. 15 3/4". (Courtesy, Saint Louis Art Museum, funds given by the Decorative Arts Society.)

Fragment of original silk damask upholstery found in the armrest padding from the armchair in fig. 24, and tack heads with threads from similar fabric found on the recess seat illustrated in fig. 26

Detail of the card table in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

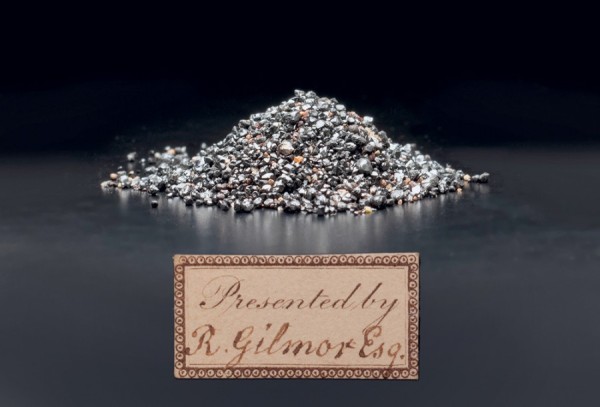

Sample of octahedral crystals and granular chromate of iron, presented by Robert Gilmor Jr. in 1818 to the British Museum. (Photo, copyright The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London.) As noted in Gilmor’s annotation on a letter dated January 10, 1818, to him from Henry Ellis (1777–1869), principal librarian of the British Museum, the crystal examples were the first “that had ever been seen in Europe.” (Henry Ellis to Robert Gilmor Jr., series I, box 1, folder 59, Robert Gilmor Collection, MS. 3198, MCHC.)

Side chair by John and Hugh Finlay, Baltimore, 1815. Tulip poplar, maple and black walnut. H. 31 5/8"; W. 18"; D. 20 1/4". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Museum Purchase.) This chair is one from a documented set of twelve made for Richard Ragan of Hagerstown, Maryland.

Side chair, attributed to the shop of John and Hugh Finlay, Baltimore, ca. 1815. Unidentified wood. H. 31 7/8", W. 20 1/8", D. 21". (Photo, copyright 2025 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.) This chair is from the suite of furniture made for Alexander Brown.

Side chair, attributed to the shop of John and Hugh Finlay, Baltimore, ca. 1815. Maple and cherry. H. 34", W. 20 1/2", D. 24 1/4". (Courtesy, Collection of Linda H. Kaufman; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chair is one of a set of eleven known chairs owned by the Abell family in the late nineteenth century.

Card table designed by Benjamin Henry Latrobe, made by John Aitken, decorated by George Bridport, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1808. Mahogany, tulip poplar, white pine; brass, gilded and painted decoration, iron, cotton velvet. H. 29 1/2", W. 36", D. 17 7/8". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art, purchased with the gift [by exchange] of Mrs. Alex Simpson Jr., and A. Carson Simpson, and with funds contributed by Mr. and Mrs. Robert L. Raley and various donors.)

Sofa, the shop of John and Hugh Finlay, Baltimore, ca. 1815. Poplar, yellow pine, other unidentified woods. H. 36", L. 105 1/2", D. 26 5/8". (Courtesy, Maryland Center for History and Culture, gift of Benjamin H. Griswold IV and Jack S. Griswold.) This sofa is part of the suite made for Alexander Brown.

Sofa, attributed to the shop of John and Hugh Finlay, Baltimore, ca. 1815. Tulip poplar, maple; painted and gilded decoration, cane, brass. H. 33 1/4", L. 103 13/16“, D. 23 5/8". (Courtesy, Cay family.)

Detail of the front rail of the recess seat in fig. 26.

Detail of the crest rail of the side chair in Appendix, cat. 6.

Detail of plate 32 from Charles Percier and Pierre Fontaine’s Recueil des décorations intérieures (Paris, 1812; reprint, 1827). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library.)

Detail of plate 25 from Charles Percier and Pierre Fontaine’s Recueil des décorations intérieures (Paris, 1812; reprint, 1827). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library.)

Detail of plate 33 from Charles Percier and Pierre Fontaine’s Recueil des décorations intérieures (Paris, 1812; reprint, 1827). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library.)

Detail of plate 9 from Charles Percier and Pierre Fontaine’s Recueil des décorations intérieures (Paris, 1812; reprint, 1827). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library.)

Detail of the stay rail of the side chair illustrated in Appendix, cat. 6.

Detail of side view of the side chair illustrated in Appendix, cat. 7, with slip seat removed. (Photo, Art Conservation Services, Baltimore.)

Detail of plate 4 from Charles Percier and Pierre Fontaine’s Recueil des décorations intérieures (Paris, 1812; reprint, 1827). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library.)

Detail of the front rail of the recess seat in fig. 26. (Photo, Martha H. Willoughby.)

Detail of the crest of the side chair in fig. 30.

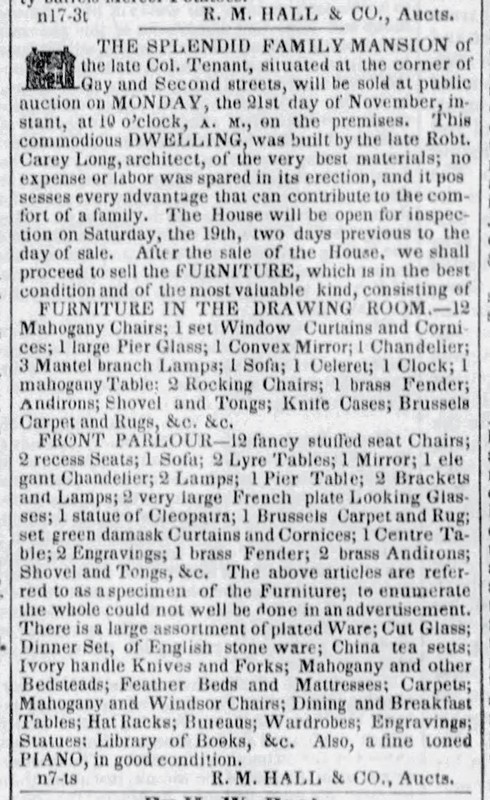

“The Splendid Family Mansion,” Sun (Baltimore), November 18, 1842. (© newspapers.com by ancestry.com.) This is the notice of the sale of Thomas Tenant’s house and furnishings after his widow died in 1842.

IN 1972, A HIGHLY UNUSUAL card table with a lyre base was featured in William Voss Elder III’s pioneering exhibition and catalogue, Baltimore Painted Furniture, 1800–1840 (fig. 1). At the time, its maker and original owner were unknown. Since then, the table along with other forms from its original suite have been attributed to the shop of John (1777–1851) and Hugh (1781–1831) Finlay.[1] This article argues that this card table was in fact part of a suite of furniture owned by Baltimore merchant Colonel Thomas Tenant (ca. 1767–1836). A reference to two “Fancy” “Lyre” tables in Tenant’s 1836 estate inventory enables this long-dispersed suite of furniture to be reassembled, dated, understood within the cultural aspirations of its original owner, and placed within the context of Baltimore’s elite who patronized the Finlays.[2]

Baltimore painted furniture has long been revered for its originality, quality, and beauty. Over the past half century these forms, particularly those associated with the Finlay brothers, have been increasingly studied by decorative arts historians. Somewhat surprisingly, as late as 1966 it was not understood that some of the Finlays’ most distinctive work—their items painted in imitation of rosewood with faux ormolu mounts—was with certainty of Baltimore origin. In his important volume from that year on Federal furniture in the Winterthur Museum collection, Charles F. Montgomery suggested that several pieces in this style, such as the recess seat in figure 2, might have originated in New York City, Philadelphia, or Baltimore. Elder’s 1972 exhibition and catalogue mentioned above was the first significant attempt to bring together a coherent group of Baltimore painted furniture, placing the various pieces within a chronological and stylistic order. Since that time, Gregory R. Weidman and Alexandra Alevizatos Kirtley have published more detailed research, bringing to light documentary evidence regarding some Finlay pieces. The present author has explored how the Finlays were the orchestrators of Baltimore’s social pageantry at locations such as the Baltimore Dancing Assembly Rooms. Furthermore, conservation and upholstery analyses on Finlay-related pieces have provided more information on the original appearance of these colorful forms.[3]

While many pieces of Baltimore painted furniture survive, very few large suites of seating and table forms, or even chair sets, remain intact; even fewer have firm documentation as coming from John and Hugh Finlay, either from their partnership or when Hugh or John ran the business separately. One of their better known documented suites, designed in 1809 by Benjamin Henry Latrobe (1764–1820) for President James Madison, was destroyed when the White House burned in 1814 (fig. 3).[4] Other notable suites made by the Finlay shop include a late, highly important and elaborate ensemble made by John Finlay in 1832 for John Carnan Ridgely (1790–1867) and his wife, Eliza E. (Ridgely) Ridgely (1803–1867), for their Hampton estate outside of Baltimore; it is still largely in situ in the house for which it was made.[5] Two undocumented suites survive in different levels of completeness. A group of seating and table forms made for Josiah Bayly (1769–1846) of Cambridge, Maryland, is in the collection of Colonial Williamsburg.[6] The so-called “Morris” suite, comprising ten armchairs, two settees, and a pier table, remains intact at the Baltimore Museum of Art (fig. 4). The forms of the suite’s chairs and painted “views adjacent to the city” are specifically referenced in an 1803 advertisement by the Finlays and can be attributed firmly to their shop around this time (fig. 5).[7] No other firm is known to have made the variety of forms seen in this 1803 advertisement, and the Finlays appear to have dominated the local market for the production of large suites.[8]

Baltimore has a somewhat unusual history for a major East Coast city. Established in 1729, long after colonial America’s other urban centers, Baltimore was a minor town prior to the Revolutionary War, with a relatively small number of residents seeking their fortunes through the emerging trade networks. However, after the close of the war, Baltimore’s economy and population boomed as young merchants arrived from various countries in Europe and from elsewhere within the United States. Many of these merchants were not “rags to riches” entrepreneurs, but rather individuals who arrived with some means that they parlayed into large fortunes. The last two decades of the eighteenth century witnessed an emergence of elegance in architecture and the decorative arts that was not present before the war—refinement that reached new heights in the first two decades of the nineteenth century. During this period the Finlays not only found willing patrons but set the aesthetic bar in furniture and interior decoration.[9]

Like many of Baltimore’s early nineteenth-century merchants, Thomas Tenant left little in the way of personal papers, and an understanding of his life and activities is largely known through the public record and from contemporary newspaper advertisements and notices. He died slightly too early for a robust obituary detailing the basic outlines of his merchant life in Baltimore, and his appearances in historical studies are largely limited to discussions of Federal period maritime shipping and trade. The place of Tenant’s birth around 1767 is uncertain, but he might have been from the Eastern Shore of Maryland.[10] By the early 1790s he was in Baltimore. During the last decade of the eighteenth century, based on newspaper notices alone, he became increasingly invested in the shipping industry. In 1792 he was noted to be a ship master; by early 1796 he had opened a ship chandlery in Fells Point under the name Thomas Tenant and Co.; and by the close of the century he owned several ships. Late 1796 seems to have been a pivotal time in his life: in November he married Mary Waters (ca. 1776–1842), and in December he dissolved his business partnership.[11] The following month, Tenant first bought land in Baltimore with the purchase of a leasehold interest in lots 72 and 73 in Fells Point, comprising approximately 120 feet of footage on the south side of George (modern Thames) Street.[12] These shallow lots backed up on the water of the northwest branch of the Patapsco River, the harbor’s edge of Fells Point. Tenant’s purchase price of £7,500, approximately twenty thousand dollars, was not insignificant, suggesting he had been thriving financially. On these lots—and others—Tenant had shipping wharfs, some of which he expanded over time (fig. 6). His first appearance in the Baltimore city directories was in 1799, where he appears at this George Street location, listed as a ship chandler.[13]

Tenant was moving upward, however, and in the city’s 1800–1801 directory he is listed as a merchant. This would subsequently remain his typical listed profession, although in 1804 he was noted to be a sea captain.[14] In 1801 he was among the directors of the Baltimore Insurance Company, and in 1803 he was elected to represent his ward in the First Branch of Baltimore’s City Council.[15] The same year, he took out an insurance policy on a likely newly built three-story brick house on his George Street property. At twenty-eight feet wide by forty-two feet deep in the main block, it was a fairly large house for Fells Point at the time, and like others it had a back building containing the kitchen.[16]

As Tenant’s career was rising, Fells Point was increasingly becoming less desirable as a place for the well-to-do to live. In 1796–1797 it had been one of the three early communities that were incorporated to form the City of Baltimore. The other two were farther west, comprising Baltimore Town on the west side of the Jones Falls and Jones Town (Old Town) on the east side of the Falls to which Fells Point was annexed in 1773 (fig. 6). Some of Baltimore’s wealthy merchants had at an early date lived in Fells Point, but during the last few decades of the eighteenth century the city’s elite began moving to the west side of the Jones Falls. A recent study notes that while in the 1770s there were some successful merchants in Fells Point, by 1796, just before Tenant purchased property, the place had become “distinctly plebian, with virtually no merchants living there despite a much larger population.[17] This perception was echoed a decade later, when New York artist and playwright William Dunlap (1766–1839) stopped in Baltimore on his way to Washington, D.C. In his description of the city he observed that Fells Point was “the place where the shipping lie and are built, and is of course the rendezvous of Sailors and those that live by their vices. Though it is regularly laid out, it is with the exception of a few houses, a mass of wretchedness and infamy.”[18]

From 1800 to 1815 Tenant was busy joining other financial boards, and he was expanding both his business enterprises and his family. After Tenant’s marriage to Mary in 1796, the couple had approximately ten children, born between the late eighteenth century and around 1820.[19] In 1805 Tenant purchased a country seat named Belmont, northeast of the city, a property first developed by a Frenchman, the chevalier d’Annemours (fig. 7).[20] In September 1814, during the Battle of North Point and the bombardment of Fort McHenry, Tenant served as a 1st major in the 6th Regiment troops, and after the battles, in March 1815, he was elevated to lieutenant colonel. The following year, Tenant was on the committee that honored those who led the successful defense of the Battle of Baltimore; his colleagues included prominent local figures John Eager Howard (1752–1827), William Lorman (1764–1841), Isaac McKim (1775–1838), Fielding Lucas Jr. (1781–1854), and Robert Gilmor Jr. (1774–1848) (fig. 19).[21] Howard represented the city’s colonial wealth: he was a Revolutionary War hero, extensive Baltimore-area landholder, and former governor of Maryland. Lorman was an extremely affluent merchant of about Tenant’s age, while McKim was also a wealthy merchant, but younger than Tenant. Also younger were Lucas Jr. and Gilmor Jr.; both were merchants and businessmen, and leaders in Baltimore’s cultural community. Tenant had arrived.

Tenant’s New Neighborhood, House, and Image

Tenant’s emergence as a member of Baltimore’s elite is manifested in his decision to move house. In 1813, while still living in Fells Point, Tenant’s budding financial and social successes encouraged him to relocate his residence to a prestigious location in the city, settling on the block on Gay Street where Robert Oliver (1757–1835) (fig. 18), one of Baltimore’s very wealthiest merchants, lived. Around the corner on Water (modern Lombard) Street resided a small group of several of Baltimore’s equally prosperous citizens from the 1780s–1810s with whom Tenant most likely wanted to rub elbows, including Samuel Smith (1752–1839) (fig. 20), John Donnell (1770–1827), Cumberland Dugan (1747–1836), Robert Gilmor Sr. (1748–1822), and Gilmor’s son and namesake mentioned above (fig. 8).[22]

All of these merchants displayed their success by building or buying large mansions in this area and furnishing them elegantly. Between 1805 and 1807 on Tenant’s future block, Oliver built an imposing five-bay fifty-six-foot-wide three-story mansion (fig. 9). Only a handful of homes this size were built in the city during the Federal period. Others included one erected for Samuel Smith in 1795–1796 on Water Street and a joined pair erected in 1799–1801 by James Buchanan (1768–1840) and John Hollins (1760–1827) on Monument Square, several blocks away (fig. 10). In addition to these five-bay dwellings were several three-bay three-story-tall mansions, somewhat cubic in form and with frontage well exceeding forty feet, which were inspired by designs espoused by architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe. These included those built by Robert Gilmor Jr. in 1809–1810 across the street from Smith’s house and by William Lorman on nearby Lexington Street (fig. 8).[23]

The location of Tenant’s new home, on the northwest corner of Second (modern Water) and Gay Streets, previously had been the site of Oliver’s business and, on the adjacent lot to the north, Oliver’s residence. After Oliver built his new mansion several doors north, he rented out the corner lot, and by around 1810 it was the office of one of the city’s newspapers, the Federal Republican. The wooden office was destroyed in 1812 by a mob protesting the paper’s position on the newly declared war against Great Britain.[24] After acquiring the corner lot from Oliver in 1813, Tenant engaged Robert Cary Long Sr. (ca. 1779–1833) to build his new house. Long, a carpenter by trade, managed many of the prestigious residential and institutional building campaigns in Baltimore during the first two decades of the nineteenth century, including the erection of Oliver’s and probably Lorman’s houses.[25] Construction began either in late 1813 or early 1814 and it was completed by June 1815, when Tenant insured the property with the Equitable Society for twenty thousand dollars, an extraordinarily high valuation for a house of this size. The three-story front building was thirty-four-and-a-half feet wide by fifty feet deep, beyond which was a back building that served as the kitchen. The main building was raised above the pavement to allow for a basement of sufficient height to accommodate offices for Tenant’s business. Significantly, Tenant’s insurance policy recorded that both the front and back buildings were “finished in a superb manner having Slate roof & fire walls capped with stone—the front house has also marble panneling [sic] underneath the first story windows.”[26] “Superb” was rarely used by representatives of the Equitable Society. After the society first began insuring houses in 1794, only a few houses had been so described, suggesting the unusually high quality of Tenant’s mansion. Notably, one of the next houses similarly described by the firm was the house Oliver built for his daughter and son-in-law Roswell Lyman Colt (1779–1857), adjoining Oliver’s mansion to the north on this same block on Gay Street (fig. 9; see map in fig. 8). When completed in 1817, it was described as “finished in a superb plain manner.”[27] Further indicating the opulence of Tenant’s home was the description of J. B. G. Fauvel Gouraud (1784–after 1860). A native of Martinique, he visited Baltimore in 1815 and recalled over twenty years later that Tenant had built a “hôtel magnifique” on Gay Street.[28]

There is no known image that shows the entire facade of Tenant’s mansion, and in 1853 it was torn down to make way for a bank building after Gay Street had lost its allure for Baltimore’s elite. With three bays and at nearly thirty-five feet wide, it was eclipsed in size only by the handful of nearby larger houses previously mentioned and a few others scattered elsewhere. The front faced east on Gay Street and the side of the building faced south on Second. A fragmentary image suggests Tenant took advantage of his corner location by placing windows on the south-facing side, a luxury a land-locked mansion could not achieve (fig. 11). His entrance hall was likely slightly over ten feet wide, and his paired parlors were probably twenty feet wide and of equal, if not greater, depth.[29]

The Finlays and Baltimore’s Elite

The site of Tenant’s new mansion put him at the very epicenter of Baltimore’s elite and fashionable society. A number of these individuals, including Tenant, were officers at the time in one of the city’s most ambitious building campaigns to date, the erection of a Merchants Exchange building. Designed by Benjamin Henry Latrobe, construction began in 1816 on the corner to the south of Tenant’s mansion, and the enormous building encompassed the entire city block south to Water Street (fig. 12; see map in fig. 8).[30] In 1880, the architect Latrobe’s son John H. B. Latrobe (1803–1891) delivered a lecture at the Maryland Historical Society regarding his recollections of Baltimore in the 1820s. His account described many areas of the city as they had appeared at that time, and in his discussion of those figures who were the “leaders” of the city then he noted that “Gay Street and its immediate neighborhood” was the “Court end of Baltimore.” He began his discussion with Oliver’s mansion, Colt’s next door, and the “noble mansion of Colonel Tenant” several doors south on the corner of Second Street. This neighborhood, according to Latrobe, included the mansions around the corner on Water Street, like Gilmor Jr.’s and Smith’s, and others not too far away, allowing Latrobe to conclude: “Gay Street near Second Street was properly regarded as the fashionable centre of the town.”[31] Earlier, a contemporary writer had observed in 1816 that “the most tasty and extensive dwelling houses” in Baltimore and “many of the largest and most wealthy families” were situated near the Exchange.[32]

Notably and importantly for understanding Tenant’s furnishings, his new neighborhood placed him in the midst of those who patronized the Finlays (fig. 8). At the time when Tenant was building his house, the Finlays’ warehouse and dwelling were just two and a half blocks north of his new home. Their address, 32–34 North Gay Street (old number), was on the east side of the street between Baltimore and Frederick Streets, where it had been since 1810 after they took over the workshop of furniture makers Coleman and Taylor.[33] Previously, the family of sisters Sydney Buchanan (1753–1843) and Margaret (Peggy) Buchanan (1758–1850) commissioned a suite attributed to the Finlays, likely around 1803–1805, when the Buchanans built a pair of adjoining houses on the west side of Gay Street, almost across the street from the Finlays’ future location. Painted renditions of their mansions ornamented the skirt of the pier table from the suite (figs. 13, 14).[34]

Of Tenant’s near neighbors, Robert Oliver left the most extensive documentation of his interactions with the Finlays. In 1806, while he was in the middle of building his nearby mansion, Oliver paid John and Hugh Finlay to make thirty-eight chairs and two settees—perhaps including three sets of twelve with matching settees for some—for his lavish new house. The following year he was charged by the firm for “repairing his carriage,” likely repainting it. At the same time he also purchased “Paints, Pencils [i.e. paintbrushes] &c.” for his son Charles. In 1809 Oliver’s brother John, who lived with him, paid the brothers for a “military stand,” which John presented to one of the city’s militia companies. Robert Oliver paid the firm for “Chairs and Settees” in 1810 and, based on the price, the order was similar in scale to his earlier one. Several years later, in 1819, while building his hunting retreat, Harewood, he paid “Finlay,” indicating Hugh at this time, “for damask for Curtains,” and in 1821 he paid him for “furniture hanging Curtains &c.”[35] While none of Oliver’s purchases from the Finlay shop has been identified to date, Oliver stands as a loyal customer who availed himself of all the services advertised by the Finlays (fig. 5).[36]

In 1809 Tenant’s neighbor Samuel Smith recommended one of the Finlays to First Lady Dolley Madison as “our Man of Taste,” encouraging her to accept his recommendation so that the firm might execute Latrobe’s furniture designs for the White House (fig. 3).[37] While at present furniture made by the Finlay shop cannot be traced to Smith’s ownership, his high praise suggests he may have patronized their firm while also clearly indicating that his circle looked to the Finlays for their home furnishings. Across the street from Smith, Robert Gilmor Jr., as quoted below, remarked in 1814 on the use of chrome yellow on carriages and furniture. He was undoubtedly referencing the work of the nearby Finlay shop, which worked in both trades, and his comment shows that he was intimately aware of their business.[38] Around the time Tenant was building his house and shortly thereafter, merchants Alexander Brown (1764–1834) and James Wilson (1775–1851), both of whom lived on Holliday Street behind the Buchanan sisters’ houses on Gay Street, were also commissioning large and elaborate suites attributed to the Finlays (figs. 2, 15, 31, 34; see map in fig. 8).[39] Another documented patron of the Finlays, Charles Carnan Ridgely (1760–1829), purchased a mansion in 1815 several doors north of the Buchanan sisters, nearly opposite the Finlay workshop.[40] In a large city of over forty-five thousand people, this somewhat small “Court end” of town was, in fact, the location of all the known suites of fancy furniture attributed to the Finlays that were made for private clients living in the city.

As has been discussed by the author previously and beginning in about 1803, the Finlays were involved with the public pageantry that Baltimoreans celebrated at the Dancing Assembly Rooms, the social center of Baltimore’s high society. On the corner of East (Fayette) and Holliday Streets, the Assembly Rooms were also centrally located among the homes of this select group (fig. 8). Almost all of Baltimore’s elite who have been discussed here, including Tenant, were members of the Assembly.[41] In October 1824 the Dancing Assembly Rooms and adjacent Holliday Street Theatre were the scene of the city’s entertainment for the marquis de Lafayette during his farewell tour of the United States, the legendary “Silver Supper.” Under the direction of Robert Gilmor Jr., the chairman of the Committee of Arrangements and a recognized “Man of Taste” as a patron, Hugh Finlay and Co. was hired to transform these spaces for a supper and a ball, contemporaneously described as the “grandest entertainment of the kind ever witnessed in this city, both as regards the style and taste of the decorations.” With his “well known taste and superintendence,” Hugh created “splendor” in the “magnificent” saloon temporarily installed in the theatre where, among other decorations, he constructed a chandelier twelve feet in diameter ornamented with stars to further light the space. In the Assembly Rooms, the various spaces were heavily laden with symbolic imagery, including a receiving room decked out in crimson fabric draped as festoons from spears, from which hung civic wreaths. Where Lafayette was seated here and in an adjoining supper room, emblematic backdrops were created to frame the important guest. Based on the detailed descriptions of the event, this was an enormous commission for Finlay.[42]

The city of Baltimore was abuzz with all of the activities involved in welcoming “The Nation’s Guest,” including a dinner hosted by the Society of the Cincinnati at James Buchanan’s mansion (fig. 10) and a dinner held by the Corporation of Baltimore at the Fountain Inn. Samuel Smith’s brother-in-law and neighbor William Patterson (1752–1835) served on the committee of arrangements that was given authority by the city to plan for and purchase the decorations for Lafayette’s welcome and dinner at the Fountain Inn.[43] While the Finlays were well known for undertaking such events, their extensive furnishings for the Assembly Rooms may have taxed their capacity. Patterson and his committee needed to turn elsewhere for some of their decorations and furniture and commissioned six dozen fancy “Cane seat chairs” from Baltimore chairmaker John King (active 1808–1829), whose shop for nearly a decade had been at 24 North Gay Street (old number), just several doors away from the Finlays.[44] For the event, Hugh Finlay only produced four pier tables, apparently fancy, which were lent with marble tops to be returned. Little-known miniaturist Joseph Weisman (dates unknown) was commissioned to paint eighty “Portraits of General LaFayette on chairs & Tables,” apparently decorating both King’s and Finlay’s pieces.[45] After the event was over, the city sold all the items they had commissioned for the dinner, with Patterson acquiring at least “1 Doz: La Fayette Chairs.” From this large commission, only three chairs and one pier table are known to survive, all with history of being owned by Patterson (figs. 16, 17).[46]

Baltimore’s Federal Elegance

While there is no known contemporary description of Tenant’s furnishings, some of the more detailed accounts of Baltimore interiors from the late Federal period refer to houses in his neighborhood. These include the mansions owned by Robert Oliver, Robert Gilmor Jr., and Samuel Smith, all of whom were painted by nationally and internationally recognized porportrait artists (figs. 18–20). Like their furnishings, these fine portraits spoke to their identity as members of Baltimore’s elite. They owned country houses that were depicted on various sets of furniture attributed to the Finlays, as was Belmont, Tenant’s country estate (fig. 7).[47] Oliver’s furnishings included three thousand dollars’ worth of mahogany furniture from Coleman and Taylor, whose Gay Street shop the Finlays later occupied.[48] In 1811 Oliver and his family were visited by Mary (Craig) Cumming (1790–1815), from Lisburn, Ireland, near the Olivers’ native town. Mary reported that the Olivers:

live in the greatest style you can imagine . . . We all dined with them the day before we left Baltimore. I cannot well describe the magnificence of their house and furniture. I think it is the finest looking house in Baltimore. You go up a flight of beautiful white marble steps to the door, the rooms are very splendid indeed. The drawing-room window curtains, sofa cover, and chairs are of blue figured satin, the mirrors and lamps are equally elegant, as for the dinner I can give you no description of it, but that the china, plate and glass on the table was the finest I ever saw.[49]

In Robert Gilmor Jr.’s impressive and elegant mansion on Water Street, he displayed his art and other collections in likely one of Baltimore’s more spectacular Federal period interiors. In 1815, several years after the house was completed, Harriott (Pinckney) Horry (1748–1830) of Charleston visited the Gilmors and dined with them. She noted in her diary:

[their] house is very well furnished and appears to have every convenience and full of elegant knicnackery, the library is a beautiful bijou, the drawing room furniture crimson Damask, the outsides of the arms of the Sofas are a sort of griffin in Bronze with brass or gilt heads, a marble slab supported in the same manner in the middle pier has a looking glass fixed under it and the chairs have loose cushions with tassels. In the dining room are four sideboard tables with a large square knife case on each and in each corner of the room is a large Image on a marble pedestal holding a lamp. The Walls of the common parlour [breakfast room] are entirely covered with pictures & there is in it a very handsome shaped mahogany sofa. The desert china was very handsome blue grounded, and amply fill’d with Ice creams, strawberries &c.”[50]

Samuel Smith’s five-bay-wide mansion on the north side of Water Street, built in the mid-1790s, was probably the first of its size and elegance.[51] During the Panic of 1819, Smith faced an embarrassing financial reversal, as did many other Baltimore merchants, but his failure encouraged his niece (by marriage) Elizabeth Patterson (1785–1879), daughter of William Patterson, to observe that he had been:

severely punished for the folly which led him to build and furnish with regal magnificence a palace.

I am sorry to express my conviction that General Smith’s fine house, and the extravagant mode of living he introduced into Baltimore caused the ruin of half the people in the place, who, without this example, would have been contented to live in habitations better suited to their fortunes; and certainly they only made themselves ridiculous by aping expenses little suited to a community of people of business.

It is to be hoped that in [the] future there will be no palaces constructed, as there appears to be a fatality attending their owners, beginning with Robert Morris [in Philadelphia] and ending with Lem. Taylor [in Baltimore]. I do not recall a single instance, except that of [William] Bingham [in Philadelphia], of any one who built one in America, not dying a bankrupt.[52]

At the time of his financial collapse, Smith owned large quantities of furniture, including for instance over one hundred chairs, with thirty-six described as mahogany, fourteen as rosewood, thirty-two as rush bottom, and twenty-two as Windsor. These various types, comprising a number of different sets, would have been appropriate for different rooms in his houses in town and country. Regardless of their makers, Smith lived extravagantly.[53]

Reflecting the close interconnections of Baltimore’s elite, Tenant, Robert Oliver, and Oliver’s son-in-law Roswell Lyman Colt were all involved in the 1819–1822 bankruptcy case of Lemuel Taylor (1769–after 1851), penned “Lem.” in Patterson’s letter quoted above.[54] Taylor, like Tenant, emerged as one of Baltimore’s wealthier merchants in the first decade of the nineteenth century, and in 1808–1809 he had a house built on East (Fayette) Street of similar size to Tenant’s slightly later mansion (fig. 8). Taylor was possibly the original owner of a suite of parlor furniture attributed to Charles-Honoré Lannuier (1779–1819), a French émigré cabinetmaker working in New York (fig. 21). Lannuier’s forms in the French taste, along with the large size of Taylor’s house (albeit not as big as Smith’s), may have led Elizabeth Patterson to include Taylor among those who built “palaces” and pursued an “extravagant mode of living.”[55]

Tenant’s Suite of Painted Furniture

Moving to Gay Street in 1815 set a very high standard for Tenant. Relocating from the “mass of wretchedness” that was Fells Point in the early nineteenth century to the “fashionable” area of town steeped in an “extravagant mode of living” was clearly an opportunity for Tenant to display his wealth and upwardly mobile status. The timing of his house construction happened to be out of sync with the City of Baltimore’s property tax assessment, so Tenant’s new house was included on an additional tax roll prepared in 1816. As of that date Tenant was assessed for his “new improvements, your dwelling,” at an assessed value of $3,000, as well as “additional Furniture” valued at $900—a high value at approximately one third of the dwelling’s assessment.[56] While Oliver was not included in this special assessment, both Tenant and Oliver were assessed several years later. On the 1818 tax rolls Tenant’s furniture was valued at $600, lower than his 1816 value, either because it was no longer new or due to changes in currency values, and he owned 640 ounces of sterling. Oliver in the same year was assessed for furniture valued at $800 and owned 861 ounces of sterling.[57] However, Oliver’s house was almost twice as large as Tenant’s, suggesting that, comparably, Tenant’s furniture was impressive. It was almost certainly recently purchased and of the latest fashions, as he appears to have sold the bulk of the furnishings of his Fells Point house. “A quantity of substantial furniture,” comprising mahogany and fancy chairs, dining and breakfast tables, carpets, looking glasses, and prints, was sold in June 1816 at an auction held at the old house.[58] The items enumerated would seem to be the furniture of his principal entertaining rooms, suggesting he had started fresh in his new public spaces—an extravagant gesture, but one consistent with his arrival in the fashionable center of town. Oliver had similarly sold some of his old furniture when he moved into his new mansion.

The only surviving contemporaneous documentation regarding Tenant’s furnishings is the paperwork generated to settle his estate when he died in 1836 (see Appendix). His household inventory is thorough, detailed, and delineates the separate rooms. Like most costly three-bay-wide houses of this period, the ground or first floor had a hall, alongside of which were a front and rear room, designated “Front Room” and “Drawing Room” in Tenant’s inventory. Also common practice, the rear room possessed a sideboard, dining chairs, and a table, but also seating forms such as a sofa, most of mahogany, so the space could be used either as a dining room or a sitting room when needed. In Tenant’s front room was a suite of “Fancy” or painted furniture, a choice that signaled Tenant’s awareness of fashionable taste (fig. 22).[59] As illustrated at the White House in 1817, President James Monroe’s supplier sent gilded furniture for the Oval Room, noting that “mahogany is not generally admitted in the furniture of a Saloon, even at private gentlemen’s houses.”[60]

At the time of his death, Tenant’s painted suite consisted of two armchairs, ten side chairs, two recess seats, two card tables, and a sofa (fig. 22). He had several other pieces of furniture in this room that apparently did not match his fancy suite: a pier table and a center table (both of unspecified finishes), as well as various lighting devices, mirrors, mantel ornaments and tools, and several prints. The room had a Brussels carpet, like Tenant’s drawing room, as well as a “set of green damask curtains & cornices.” Valued at a hundred dollars, these draperies were not only more costly than those in the drawing room (sixty dollars), but were worth more than the entire painted suite (sixty-five dollars).[61] As suggested by the image in figure 11, the draperies may have adorned at least four windows, including those on the south facade. Mary Cumming’s comment that Oliver’s curtains and seating covers were all of “blue figured satin” illustrates the prevailing fashion at this time, which dictated the use of matching fabrics for window dressings and upholstery in the entertaining rooms of a well-to-do household. This suggests that Tenant’s fancy furniture was upholstered in green damask and therefore was likely painted in a palette embracing, or complementary to, green. The Finlay shop supplied curtains, so it would have been able to oversee the coordination of fabrics for the entire room.

A particularly illuminating clue to the suite’s appearance is the word “Lyre” used in the inventory to describe the two tables, which are later identified as card tables in Tenant’s Account of Sales. The only known Baltimore painted card table from this period with a lyre base is the table in figure 1. At the time of its publication over fifty years ago, it was owned by Peter Hill, an antiques dealer based in Washington, D.C., and no earlier provenance is known.[62] This seemingly unique table, now in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, not only has a lyre base but is ornamented primarily in yellow and a vibrant green—a palette rarely found on other pieces of Baltimore furniture. Another significant clue relates to the chairs, all described as “stuffed” in the 1842 sales notice, indicating they were not caned or rushed, but had upholstered seats (fig. 47). While Baltimore fancy side chairs with upholstered seats are not uncommon, armchairs with stuffed seats are rare.[63]

Now scattered among various collections, two armchairs and eight side chairs—all with upholstered seats—as well as a single recess seat survive with painted decoration precisely matching that on the lyre-base card table (figs. 23–26; see Appendix).[64] These seating forms and the card table all correspond to the descriptions of Tenant’s suite. Numbers chiseled on the rear seat rails of the chairs suggest that there were originally twelve side chairs in addition to the two armchairs.[65] Therefore, at the time it was made, the suite probably included seven additional items—four side chairs, a recess seat, a card table, and a sofa—that are currently unlocated and may not survive. The latter may well be the case: with fragile surfaces that, when damaged, require more complicated repairs, painted furniture has a greater attrition rate than do pieces with a wood finish. Number sequences running from four to seven gauged on the casters and legs of the card table indicate it was one of pair, as were most card tables that furnished the parlors of wealthy Baltimoreans in this period.

Remnants of likely original upholstery on two of the seating forms support the argument that this suite graced Tenant’s parlor. One of the armchairs possesses a fragment of blue-green silk damask found under a later show cover, and the recess seat has large clumps of threads from seemingly identical fabric found under tack heads (fig. 27). These findings suggest that the seating forms in the suite were covered in the same fabric as the “set of green damask curtains & cornices” from Tenant’s parlor. Furthermore, the interior lining of the card table, which appears original, is a similarly hued but more utilitarian baize (fig. 28).

Thus, all of the physical evidence, as well as the social context and documentary records, indicate that this suite is the one made for Tenant. The identification of Tenant as the original owner allows the suite to be dated to a relatively precise time period, 1815 to early 1816. Since Tenant’s Gay Street house was completed by June 1815, Tenant probably commissioned the suite around this time, and it was most likely in place by June 1816, when he sold the furniture from his old house.[66] The suite, therefore, was made in the months preceding John’s departure from the shop in July 1816, a period when the Finlays embraced several innovative decorative schemes.

The Suite’s Forms and Decoration

As has been discussed by others, the Latrobe 1809 White House commission introduced the Finlays to a bold new style based on classical precedents (fig. 3).[67] Their prior work in the first decade of the century had been in the delicate style of other Federal period or neoclassical furniture (fig. 4). In their local production, this new classical style coincided with their use of chrome yellow. The “newly discovered Pigment” was advertised for sale in Baltimore in March 1812 and was certainly in use shortly thereafter.[68] In 1814 Robert Gilmor Jr. published his findings regarding minerals discovered in the vicinity of Baltimore, observing that chromate of iron was found in the Bare Hills area outside the city: “Perhaps in no part of the world has so much been discovered at one place: it furnishes the means of preparing the beautiful paint called the chromic yellow, with which carriages and furniture are now painted in Baltimore” (fig. 29).[69] According to other accounts, however, supplies elsewhere were not as plentiful and, along with a “great expense incident to its preparation,” chrome yellow was considerably more costly than other yellow pigments.[70] Its use on furniture was therefore a clear indicator of a patron’s wealth. In November 1815 Richard Ragan (1773—1846) of Hagerstown, Maryland, documented in his account book the purchase of a set of chairs with a chrome yellow ground from the Finlay shop (fig. 30).[71] With large tablet crests, the Ragan chairs illustrate the emerging classical aesthetic, but they are conservative by comparison to the more robust expressions of the new style attributed to the Finlays as seen in the chairs from the suite made for the Brown family, the chairs later owned by the Abell family, and Tenant’s chairs (figs. 23–25, 31, 32).[72]

Yet the Tenant suite may illustrate an experimental moment on the part of the Finlay shop, since several aspects of its design have no known counterparts in early nineteenth-century Baltimore. The card table from this suite is the only example known with a base composed of intersecting lyres, although related designs were beginning to be used elsewhere right at the moment when Tenant was building his house.[73] In its four columns with turned rings supporting the top, and with low saber legs, the table has some affinities with the Waln suite table shown in figure 33, designed by Latrobe and made in Philadelphia in 1808; but the interpretation on the Tenant table is lighter and more playful.[74] The saber front legs on the Tenant suite chairs are the only known instances of the design on surviving Baltimore chairs from this period, but the Finlays knew of this form, with its Greek origin, from the suite they produced for the White House (fig. 3).[75] Furthermore, the crest rails on the Tenant suite chairs are unusual in the way they scroll backwards at their extreme left and right edges, an effect that is emphasized by bosses attached above and below the scroll (fig. 37). The arms on the armchairs from this suite are also idiosyncratic and somewhat fanciful, with a curved and carved passage emanating from the crest rail followed by a padded arm rest above an upholstered arm support. Many American and British sets of klismos chairs include armchairs, but invariably the arm is attached to the rear stile and lacks the upholstered support. At the time the armchairs were donated to the Missouri Historical Society, Saint Louis, in 1972, the exteriors of the arm supports were embellished with composition ornaments in the form of cornucopias. While these appear to be old replacements, their scrolling leaves are similar in design to the carved foliage on the upper arms, suggesting the cornucopia ornament may replicate or mimic the original decorative scheme (fig. 23).

The form of the surviving Tenant suite recess seat is identical to that documented to the Finlay shop and made for James Wilson in about 1825 (figs. 2, 26). The Wilson example bears a faux rosewood finish with gilt detailing, a decorative treatment favored by the Finlay shop from the late 1810s through the mid-1830s. The appearance of the sofa from the Tenant suite is unknown. The term “sofa,” often written as “sopha,” was loosely used to describe forms with sides of equal heights and with or without a back, as well as forms with higher headrests and lower footrests, either without a back or with a half back.[76] While a number of sofas survive from the Finlay shop’s slightly later faux rosewood period with saber legs, Finlay sofas from the mid-1810s are rare. Dating to about 1815, the sofa made for Alexander Brown has turned legs like the other seating forms in his suite (figs. 31, 34); similarly, like Tenant’s chairs and table, it is likely that Tenant’s sofa stood on saber legs. One surviving sofa with saber legs attributed to the Finlay shop from the mid-1810s may provide clues to the appearance of the Tenant sofa (fig. 35). Its decoration appears to be solidly from the Finlay workshop, with its scabbard-sheathed sword flanked by thunder and lightning designs on the front rail, elements that are found on the Brown sofa; in form, it is nearly identical to the sofa from the Waln suite.[77]

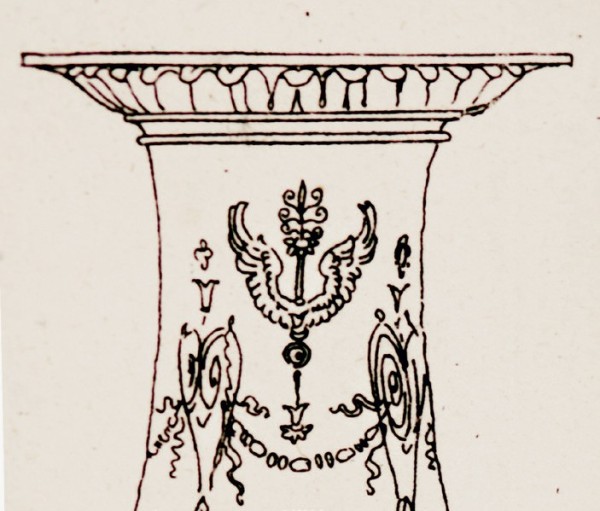

The painted decoration that unites all of the Tenant suite forms is closely related to other Finlay shop pieces, but it is not precisely replicated elsewhere. As first noted by Elder in 1972 in his discussion of the Brown suite, the Finlay shop drew directly from Charles Percier and Pierre Fontaine’s 1812 Recueil des décorations intérieures for many of its important commissions from the mid-1810s.[78] As illustrated by the Brown suite, the Abell family chairs, and the Tenant suite, Percier and Fontaine presented the Finlay shop decorators with innumerable classical motifs—largely inspired by ancient Rome—that could be mixed, matched, and modified to fill variously shaped ornamental surfaces. On occasion these motifs seem to be lifted directly from the publication, while other details appear to be fanciful adaptations. Uniting the disparate Tenant suite forms is the presence of the same decorative passage on the crests of the chairs, the front and back skirts of the card table (as well as on the top when closed), and the front and back seat rails of the recess seat (figs. 1, 36, 37). This repeated frieze depicts a circular frame headed by a palmette flanked by crouching griffins that are further flanked by rinceaux, stylized scrolls of foliage. The central grouping replicates the numerous examples of paired griffins depicted by Percier and Fontaine, particularly that seen in a design for a desk (fig. 38).[79] The rinceaux that trail from their tails is distinguished by cornucopia-like forms issuing anthemion petals. This configuration is adapted from several plates in Percier and Fontaine’s volume (fig. 39) and contrasts with the use of large multi-petaled flowers seen on the rinceaux ornament on other furniture from the Finlay shop, such as the Abell family chairs and the Brown suite (figs. 31, 32).[80]

The decorator of the Tenant suite made use of portions of Percier and Fontaine’s symbolic references to Jupiter’s might. The fully realized version, with thunder, lightning bolts, and eagle wings, is prevalent on their designs for Napoleon, who wanted to invoke this ancient symbol of supreme power (fig. 40). It is replicated on several Finlay forms made around the same time as the Tenant suite, such as the Brown suite and the Abell family chairs, as well as on later commissions from the 1820s. On occasion, Percier and Fontaine depicted the “thunder” motif (a twisting spiral) on its own, often but not always in pairs. The proportions varied, and when attenuated the motif filled narrow spaces (fig. 41).[81] The decorator of the Tenant suite used such adaptions in pairs on the stay rails of the chairs, on the side rails of the card table and recess seat, and singly on the side seat rails of the chairs; the termini were fanciful combinations of other elements, such as heart-shaped palmettes and stylized lotus leaves (figs. 42, 43). Other examples of Jupiter’s iconography are seen on the side facades of the chairs’ front legs, where a curving needle-like device is capped by the god’s eagle wings, a combination also taken from Percier and Fontaine (figs. 43, 44). Like the other principal ornaments, namely the griffins, rinceaux, lyres, and thunderbolts, these designs are sized and shaped to fill the different spaces of the structures’ component parts.

With the pair of lyres supporting the top of the card table, it is not surprising to find that lyres are used in the painted ornamentation on the Tenant furniture (fig. 45). Percier and Fontaine provided numerous examples of lyres, some flanked by laurel foliage as is also seen on the Tenant suite. In the known Tenant pieces, the lyres are found flanking the central frieze on the front and rear rails of the card table and recess seat, as well as on the corners of the side rails of the card table. The absence of the lyre motif on the Tenant chairs is due to their seat design, which lacks rectilinear rails and instead is over-upholstered with conforming side rails rounded in front. Had the chairs been caned with a trapezoidal box seat, such as the Brown or Abell family chairs, the lyre likely would have appeared on the front rail over the front legs, and similarly on the side.

A comparison of the execution of the painted ornament of the Tenant suite with other pieces made by the Finlay shop around the same time indicates the work of multiple decorators. The same individual appears to have been responsible for the Tenant and Ragan suites. Both commissions display similarly designed and executed flanking branches of laurel, with leaves and berries in clusters and a combination of white and black outlines that create a shadow effect consistent with a light source above and to the left (figs. 45, 46). This decorator had a looser hand than the craftsman of the Brown suite or the Abell family chairs, where the decoration is highly controlled and tightly executed. In the absence of shop records or other documentary evidence, the identities of these craftsmen remain unknown.[82]

The palette of the Tenant suite, predominantly brilliant green on a yellow base, is similar to the color scheme seen on the Abell family chairs but not otherwise seen on furniture attributed to the Finlay shop. Pigment analysis of the decoration on one of the Tenant side chairs and one of the Abell family examples demonstrates the presence of chrome yellow for the yellow and a mixture of chrome yellow and Prussian blue for the green. However, the amount of blue may be less in the Tenant chairs, which retain a vibrant green shade, while the color seen in the Abell family examples leans more toward a “bronze” green or verde antique in a darker bluish-green tone.[83] Visual observation indicates that on all of the Tenant pieces the griffins and central ornament are depicted in yellow with shadows of raw umber, and with small highlights in white, while the scrolling foliage in yellow has shades of both raw umber and burnt sienna in the shadows (fig. 37). A similar hierarchy regarding the central figural ornamentation and the rinceaux is found on the Abell family chairs and other Finlay furniture, where reddish tones not found on the central zoomorphic forms are introduced into the foliage. The lyres, like the foliage in the central frieze, are highlighted with raw umber and burnt sienna pigments (fig. 45). Furthermore, some gilding is evident on the principal ornaments and on stripes that accent the stiles and front legs, with touches of bronzing powders as well.

The Dispersal of the Suite

Tenant lived in his new house for approximately twenty years before he died in 1836, leaving behind his wife, about seven surviving children, and their families. His only son, Thomas W. Tenant (ca. 1805–1838), married in 1832 but died only a few years later, leaving a son and two daughters. Of Tenant’s many daughters, Mary (1802–1824) married lawyer and author John Pendleton Kennedy (1795–1870) in January 1824 at a ceremony believed to have taken place at Tenant’s house. Although Mary died in childbirth later that year and their son the following year, Kennedy remained a close friend and confidant of Tenant and was eventually named one of his executors. Kennedy recorded the demise of his former father-in-law in his journal, noting that he had been bed-ridden since 1831.[84]

Tenant died a very wealthy man. His executors, including his wife, Mary, his former son-in-law John Pendleton Kennedy, and friend and business associate Henry Thompson (1774–1837), administered his will and recorded inventories and accounts of his assets. Tenant’s furnishings of his Gay Street mansion were inventoried by room and in good detail for the period. His suite of fancy furniture was recorded in his front parlor. By his will, Tenant left his wife a life tenancy to their house and furnishings, but other properties, including his country seat, Belmont, were sold. Mary remained at the Gay Street mansion until her death in 1842, at which time Tenant’s will directed that his house and furnishings be sold.[85] The November 1842, notice of the sale of the “Splendid Family Mansion” proclaimed that the furniture was “in the best condition and of the most valuable kind” and itemized the pieces in the two principal rooms on the first floor (fig. 47).[86] The listing for the front parlor begins with “12 Fancy stuffed seat Chairs; 2 recess Seats; 1 Sofa; 2 Lyre Tables,” and later mentions “set green damask Curtains; and Cornices,” indicating that the suite—along with the rest of the room’s furnishings—had remained intact in the six years since Tenant’s death. As recorded in the account of the sale, which took place a month later, the suite was broken up into five lots: the two armchairs; ten side chairs; two recess seats; two card tables; and the sofa. Together, these pieces sold for a total of $49.50—a relatively modest sum for items of such quality—suggesting that by the early 1840s they were out of fashion. The purchasers of the five lots of Tenant’s painted suite are unknown; their names were uncharacteristically not recorded by the administrators of the estate for unknown reasons.[87]

The next known location of any of the pieces from Tenant’s suite are for six of the side chairs, which according to reliable family accounts were purchased by David Churchman Trimble (1832–1888) (fig. 25; Appendix, cats. 5–10). He was too young to have acquired them at the 1842 sale and most likely bought them at some point between his marriage in 1859 and his death in 1888, perhaps from the original 1842 buyer. By the 1920s, these six chairs were owned by Margaret Emily (Jones) Trimble (1865–1954), the widow of David’s son, Dr. Isaac Ridgeway Trimble (1860–1908), and furnished the home she had shared with her late husband in the Mount Vernon neighborhood at 8 West Madison Street. The Mount Vernon neighborhood around Baltimore’s Washington Monument had emerged as the new center of Baltimore’s elite in the 1840s. Interestingly, another two of Tenant’s side chairs were recorded around the corner in 1937 in the collection of Eugenia R. (Miller) Whyte (1857–1949). At that time, she was living at 700 North Charles Street, but for most of her adult life had lived just one block west at 700 Cathedral Street (Appendix, cats. 3, 4).[88] The surviving recess seat from the suite may also have been in the same area during the early twentieth century (fig. 26; Appendix, cat. 11). It was pictured in a 1966 photograph of Staunton Hill, the Virginia home of David K. E. Bruce (1898–1977), who had lived with his parents at 8 West Mount Vernon Place, midway between the Trimbles and Whytes, from 1898 to 1919. As these later owners did not have close familial ties, the buyer or some of the buyers at the 1842 sale probably lived in the Mount Vernon neighborhood or subsequently moved there in the later nineteenth century. The suite’s armchairs were in Saint Louis, Missouri, in the early twentieth century with no documented path of ownership from Baltimore (figs. 23, 24; Appendix, cats. 1, 2). The earliest known whereabouts of the card table dates to 1972, when it was owned by antiques dealer Peter Hill in the Washington, D.C. area; its history prior to 1972 is unknown (fig. 1; Appendix, cat. 12).

As a reassembled and identified suite of painted furniture, the Tenant suite tells us much about the role the Finlays played in the display of wealth and social status in early nineteenth-century Baltimore. Tenant was a relative newcomer to Baltimore’s mid-to-late Federal period elite, but he was clearly strategic about his choices to demonstrate his arrival, not only by situating himself at the very center and “Court end” of Baltimore’s fashionable society, but by commissioning furniture from the Finlays for his “noble mansion.” Although Tenant’s house was demolished and his furniture scattered, bringing those pieces together here, along with details about others who lived in his neighborhood and how splendidly they furnished their homes, allows us also to reconstruct the milieu of a group of Baltimore’s wealthier citizens. Their interiors and Finlay furnishings were critical in conveying the sense of identity and place of their owners. The preservation and acquisition of several examples from the Tenant suite by well-to-do Baltimoreans in the late nineteenth century suggest that the Finlays’ forms continued to evoke Baltimore’s Federal elegance well after Tenant’s lifetime.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author wishes to extend particular thanks to Gregory R. Weidman for reviewing an early draft of this article.

William Voss Elder III, Baltimore Painted Furniture, 1800–1840 (Baltimore: Baltimore Museum of Art, 1972), p. 72, cat. 46. Sumpter Priddy, American Fancy: Exuberance in the Arts, 1790–1840 (Milwaukee, Wis.: Chipstone Foundation, 2004), pp. 60–61, suggests that one of the side chairs from this set could have been made in Baltimore or Philadelphia, perhaps relying on Alexandra Alevizatos Kirtley, “New Discoveries in Baltimore Painted Furniture,” Catalogue of Antiques & Fine Art 3, no. 2 (Spring 2002): 208, where it is suggested that this same chair was from Philadelphia. For recent scholarship on the suite, see Important Americana, sale N08608 (New York: Sotheby’s, January 22, 2010), lots 561, 562; Philip D. Zimmerman, “An Important Baltimore Painted Card Table” (unpublished report, Stanley Weiss Collection, Providence, R.I., February 21, 2011) (the author thanks the Stanley Weiss Collection for providing a copy of this report) and an abbreviated version, “An Important Classical Gilt and Paint Decorated Games Table Attributed to John and Hugh Finlay, Baltimore, Maryland, circa 1815,” available at https://stanleyweiss.com/site/item/sw00781/, accessed August 31, 2024; Important Americana, sale N08950 (New York: Sotheby’s, January 25, 2013), lots 456, 457; Fine American Antiques in the Stanley Weiss Collection (Providence, R.I.: Stanley Weiss Collection, 2019), p. 240; Alexandra Alevizatos Kirtley, American Furniture, 1650–1840: Highlights from the Philadelphia Museum of Art (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2020), p. 294, cat. 297.

Thomas Tenant’s Inventory, February 3, 1836, Inventories DMP 45, f. 295, Register of Wills, Baltimore County, Maryland State Archives, Annapolis, Md. (hereafter MSA).

Charles F. Montgomery, American Furniture: The Federal Period (New York: Viking Press, 1966), p. 315, cat. 280. Elder, Baltimore Painted Furniture; Gregory R. Weidman, Furniture in Maryland 1740–1940: The Collection of the Maryland Historical Society (Baltimore: Maryland Historical Society, 1984); ———, “The Furniture of Classical Maryland, 1815–1845,” in Classical Maryland 1815–1845: Fine and Decorative Arts from the Golden Age, edited by Gregory R. Weidman and Jennifer F. Goldsborough (Baltimore: Maryland Historical Society, 1993), pp. 89–140; ———, “The Painted Furniture of John and Hugh Finlay,” Antiques 143, no. 5 (May 1993): 744–55; Kirtley, “New Discoveries in Baltimore Painted Furniture,” pp. 204–09; Alexandra Alevizatos Kirtley, “Contriving the Madisons’ Drawing Room: Benjamin Henry Latrobe and the Furniture of John and Hugh Finlay,” Antiques 176, no. 6 (December 2009): 56–63; Lance Humphries, “Patronage, Provenance, and Perception: The Morris Suite of Baltimore Painted Furniture,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Milwaukee, Wis.: Chipstone Foundation, distributed by University Press of New England, 2003), pp. 138–212; Peter L. Fodera, Kenneth N. Needleman, and John L. Vitagliano, “The Conservation of a Painted Baltimore Sidechair (ca. 1815) Attributed to John and Hugh Finlay,” Journal of the American Institute for Conservation 36, no. 3 (Autumn–Winter 1997): 183–92; Rian M. H. Deurenberg, “Examination and Treatment of a Set of Klismos Chairs, Attr. to John and Hugh Finlay,” Journal of the American Institute for Conservation 47, no. 2 (Summer 2008): 97–117; Christopher M. Swan, “The Bayly Couch, circa 1820, Baltimore,” Wooden Artifacts Group Postprints, 32nd Annual Meeting of the American Institute for Conservation in Portland, Oregon (2004), pp. 44–55, available online at https://wag-aic.org/2004/swan_04.pdf, accessed September 25, 2024.

This commission has been investigated by numerous authors, most recently in Kirtley, “Contriving the Madisons’ Drawing Room.”

Weidman, “The Painted Furniture of John and Hugh Finlay,” pp. 753–55. A sofa, pier table, center table, and six of fourteen chairs from the suite are part of the Hampton National Historic Site collection in Towson, Md.

Tara Gleason, “The Bayly Suite of Painted Furniture,” Antiques & Fine Art 4, no. 1 (Spring 2003): 206. The suite consists of a couch, two pier tables, and four extant chairs. Numbers on the chairs and their slip seats indicate that there were originally twelve chairs.

Humphries, “Patronage, Provenance, and Perception.”

In addition to this 1803 advertisement, the Finlays on several occasions advertised their breadth of production; see, for instance: “Elegant Fancy Furniture,” American, November 7, 1806. All newspapers cited here and below are Baltimore unless otherwise noted. For the Finlays’ work within the larger world of “fancy” objects, see Priddy, American Fancy, particularly chapter 3: “Early Fancy Furnishings,” pp. 37–80.

The increasing refinement in the city around the turn of the nineteenth century is the subject of a forthcoming book, “The Baltimore Town House, 1780–1865,” by the present author, that focuses not only on the houses and their furnishings, but also on the “neighborhoods” inhabited by Baltimore’s elite.

The genealogical record lacks documentation of Tenant’s origins, and his circa 1767 birthdate is derived from his 1836 obituary: “Died,” Baltimore Gazette, January 11, 1836. J. B. G. Fauvel Gouraud, a native of Martinique (discussed below, n. 28), noted that Tenant was from a “poor family” (in translation) from the Eastern Shore, but his information is not always accurate; see his L’Hercule et la favorite, ou, La capture de l’Alexandre de Bordeaux . . ., 2 vols. (Paris: Chez l’auteur, 1840), 2: 42. Tenant may well have been from the Eastern Shore’s Talbot County, as a Tenant family resided there and it was later where Tenant built some of his ships.

Tenant is mentioned as a master of ships in newspaper notices such as “District of Maryland,” Baltimore Evening Post, August 9, 1792. He then does not seem to be referenced until 1796 with notices of his new business, which he dissolved in “Notice,” Federal Gazette, December 1, 1796.

John Holmes and Charles Ghequiere, Assignment to Thomas Tenant, January 19, 1797, Deeds WG YY, f. 448, Register of Deeds, Baltimore County, MSA.

The Baltimore Directory for 1799 (Baltimore: Warner and Hanna, 1799). Tenant is not found in Baltimore’s first directory, that for 1796, perhaps because his business was new.

The New Baltimore Directory, and Annual Register, for 1800 and 1801 (Baltimore: Warner and Hanna, [1800]); The Baltimore Directory, for 1804 (Baltimore: Printed for James Robinson by Warner and Hanna, [1804]).

See the untitled notice regarding the directors, Telegraphe and Daily Advertiser, February 3, 1801; and the brief notice “Wednesday October 5,” Telegraphe and Daily Advertiser, October 5, 1803.

Policy #1,322, July 15, 1803, Book B, Baltimore Equitable Society Collection, MS. 3020, Maryland Center for History and Culture, Baltimore, Md. (hereafter MCHC)

Lawrence A. Peskin, “Fells Point: Baltimore’s Pre-Industrial Suburb,” Maryland Historical Magazine 97, no. 2 (Summer 2002): 165.

William Dunlap, Diary of William Dunlap (1766–1839), 3 vols. (New York: New-York Historical Society, 1930), 2: 375.

As with Tenant’s origins, the genealogical record lacks documentation on the exact number of Tenant’s children.

James Hindman, Deed to Thomas Tenant, July 3, 1805, Deeds WG 87, f. 590, Register of Deeds, Baltimore County, MSA. The house depicted in fig. 7 was previously unidentified in Humphries, “Patronage, Provenance, and Perception,” p. 173, figs. 42, 43. Recently, the author discovered the same structure featured and identified as Belmont in a photograph of a mid-nineteenth-century drawing; see Md: Balt: Historical, 212/2 #28, Baltimore News American Collection, Hombake Library, University of Maryland Libraries. The photograph was used in “Romance of Ready School,” unidentified newspaper, early 1922, Vertical File, MCHC.

“Appointments by the Governor and Council of Maryland,” March 16, 1815; and “Honor the Brave,” May 17, 1816; both Baltimore Patriot.

The locations of these residences are discussed in Humphries, “The Baltimore Town House” (forthcoming), chapters on Water (Lombard) and Gay Streets. Modern “Water Street” in Baltimore east of South Street was formerly Second Street.

Ibid.

“The State of the City,” Federal Gazette, June 24, 1812.

Robert Oliver & Hugh Thompson, Assignment to Thomas Tenant, March 18, 1813, Deeds WG 124, f. 223, Register of Deeds, Baltimore County, MSA. Long was identified as the builder when the house was later offered for sale; “The Splendid Family Mansion,” American and Commercial Daily Advertiser (Baltimore), November 5, 1842. This advertisement was published frequently throughout November by the same newspaper as well as the Sun (Baltimore). See fig. 47.

Policy #4,222, June 1, 1815, Book D; and Policy #7,103, June 1, 1822, Book E; Baltimore Equitable Society Collection.

Policy #5,102, Sept. 15, 1817, Book D; Baltimore Equitable Society Collection.

Fauvel Gouraud, L’Hercule et la favorite, 2: 42. Fauvel Gouraud is mentioned in Baltimore newspapers 1813–1815 as “de Fauvel” or various combinations of his compound surname. His account of his presence in Baltimore during the Battle of Baltimore (vol. 1, pp. 143–44) is consistent with several of his newspaper appearances.

Partial views of Tenant’s mansion appear in only a few images, most of which focus on the nearby Merchants Exchange building.

“An Act to Incorporate the Baltimore Exchange Company,” American, March 1, 1816; and in the same issue, “Baltimore Exchange,” which first ran on February 17. The latter requests proposals for building materials. Tenant’s possible dealings with Latrobe are unknown. While Latrobe was called on to address some residential projects in Baltimore, none of them was executed.