Chest of drawers, labeled by William King, Salem, Massachusetts, 1788–1793. Mahogany with white pine. H. 33 3/4", W. 41", D. 22 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

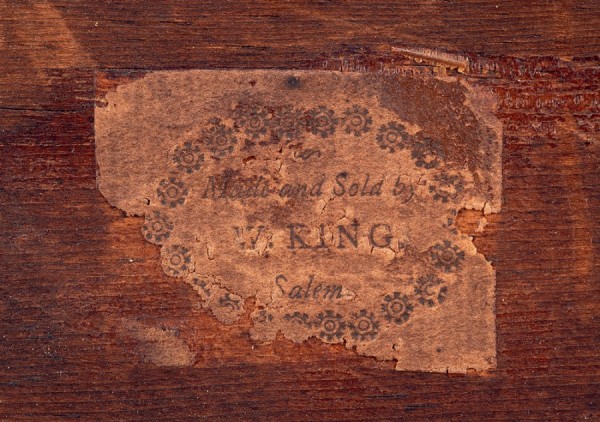

Detail of the label of William King on the back of the chest illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest of drawers, attributed to the shop of Thomas Needham Jr., Salem, Massachusetts, 1780–1787. Mahogany with white pine. H. 35 1/8", W. 41 3/4", D. 24 1/4". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Estate of Marianne M. Beach, 1962, M11444; photo, Michael E. Myers.)

Detail of the front foot of the chest of drawers illustrated in fig. 3. (Photo, Michael E. Myers.)

Advertisement by William King in the Salem Mercury (Mass.), February 5, 1793. (Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society.)

Card table, labeled by William King, Salem, Massachusetts, 1788–1793. Mahogany with white pine and maple. H. 28 1/2", W. 34 9/16", D. 17". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the swing leg showing the label of the card table illustrated in fig. 6. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, labeled by William King, Salem, Massachusetts, 1788–1793. Mahogany with white pine and unidentified hardwood. H. 38 1/4", W. 21", D. 18". (Private collection; photo, Historic New England.)

Detail of the label of William King on the underside of the seat rail of the side chair illustrated in fig. 8. (Photo, Historic New England.)

Candlestand, stamped “W. KING,” Salem, Massachusetts, 1783–1793. Mahogany. H. 28 5/16", W. 22 1/4", D. 15 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of stamped “W. KING” on the bottom of the pillar of the candlestand in fig. 10. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Advertisement by William King in the Dartmouth Gazette (Hanover, N.H.), March 28, 1806. (Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society.)

Silhouettes of Zilpah and Stephen Longfellow, William King, Portland, Maine, ca. 1805. (Courtesy, Collections of Maine Historical Society.)

Details of gadrooned carving on five pieces of case furniture traditionally attributed to William King:

A: front foot of the chest of drawers illustrated in fig. 3. (Photo, Michael E. Myers.)

B: front foot of the chest of drawers illustrated in fig. 59. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

C: front foot of the chest of drawers illustrated in fig. 44.

D: front foot of the desk and bookcase illustrated in fig. 69. (Photo, Brock Jobe.)

E: front foot of the desk illustrated in fig. 35. (Photo, Michael E. Myers.)

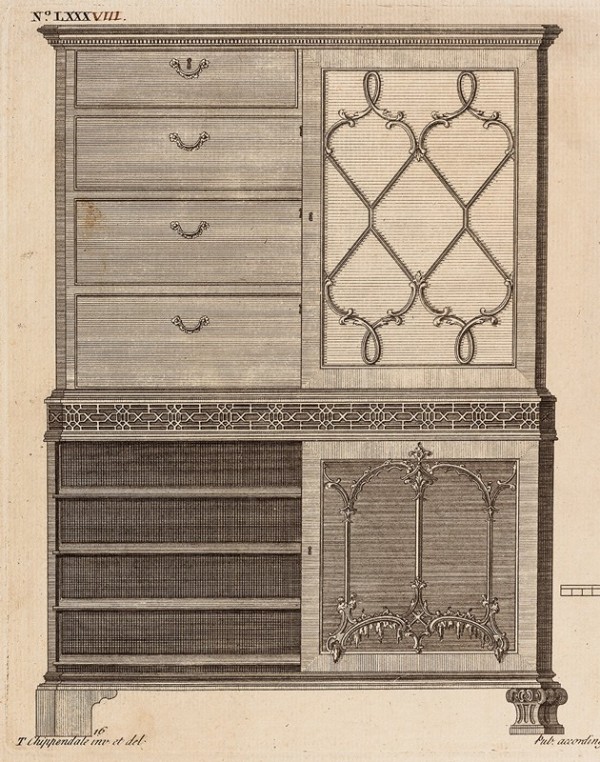

Design for a “Desk & Bookcase” and detail of foot shown on pl. 78 of the first edition of Thomas Chippendale’s The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (London, 1754). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library.)

Detail of the interior of the chest of drawers in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the bottom of the chest of drawers in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the rear foot bracket of the chest of drawers in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a veneered drawer front in the chest of drawers in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the laminated pine core of a drawer in the chest of drawers in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest of drawers, Thomas Needham Jr., Salem, Massachusetts, 1783. Mahogany with white pine. H. 36 1/2", W. 44 1/4", D. 24 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Sack Family Archive, Yale University Art Gallery.)

Detail under infrared light of the inscription “TN 1783” on the bottom of the chest of drawers in fig. 21. (Photo, Sack Family Archive, Yale University Art Gallery.)

Chest of drawers, attributed to the shop of Thomas Needham Jr., Salem, Massachusetts, 1780–1787. Mahogany with white pine. H. 33 1/2", W. 46", D. 23 5/8". (Photo, © 2024 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.)

Chest of drawers, attributed to the shop of Thomas Needham Jr., Salem, Massachusetts, 1780–1787. Mahogany with white pine. H. 33 1/4", W. 44 1/2", D. 22 7/8". (Courtesy, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, bequest of Mr. and Mrs. Joseph H. Hennage.)

Chest of drawers, attributed to the shop of Thomas Needham Jr., Salem, Massachusetts, 1780–1787. Mahogany with white pine. H. 31 3/4", W. 41 1/4", D. 23". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Desk, attributed to the shop of Thomas Needham Jr., Salem, Massachusetts, 1780–1787. Mahogany with white pine. H. 44 7/8", W. 47 1/2", D. 25 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Sotheby’s.)

Desk, attributed to the shop of Thomas Needham Jr., Salem, Massachusetts, 1780–1787. Mahogany with white pine. H. 43 1/2", W. 43 3/4", D. 24". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Estate of Sarah Ann Cheever, 1908, 101792; photo, Walter Silver.)

Chest of drawers, attributed to the shop of Thomas Needham Jr., Salem, Massachusetts, 1785–1787. Mahogany with white pine. H. 35 1/2", W. 41 1/2", D. 24". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the rear foot of the chest of drawers in fig. 3. (Photo, Michael E. Myers.)

Detail of the top of the chest of drawers in fig. 25. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the pendant drop of the chest of drawers in fig. 3. (Photo, Michael E. Myers.)

Detail of the interior of the chest of drawers in fig. 3. (Photo, Michael E. Myers.)

Detail of the bottom of the chest of drawers in fig. 3. (Photo, Michael E. Myers.)

Detail of the drawer bottom in the desk in fig. 26. (Photo, Brock Jobe.)

Desk, Salem-Beverly area, Massachusetts, 1780–1790. Mahogany with white pine. H. 42", W. 45 5/8", D. 25 1/16". (Courtesy, James W. Lowery Fine Antiques and Arts; photo, Michael E. Myers.)

Detail of the interior of the desk in fig. 35. (Photo, Michael E. Myers.)

Desk, Salem-Beverly area, Massachusetts, 1780–1790. Mahogany with white pine. H. 42 1/8", W. 45 3/4", D. 24 7/8". (Courtesy, The Stanley Weiss Collection.)

Detail of the interior of the desk in fig. 37.

Desk, Salem-Beverly area, Massachusetts, 1780–1790. Mahogany. H. 43 1/8", W. 41", D. 23". (Current location unknown; photo, Bonhams Skinner.)

Chest-on-chest, Salem-Beverly area, Massachusetts, 1770–1780. Mahogany with white pine. H. 74 3/4", W. 45 3/4", D. 24 1/4". (Courtesy, Historic New England, Museum purchase with funds provided by an anonymous gift, 1985.9; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

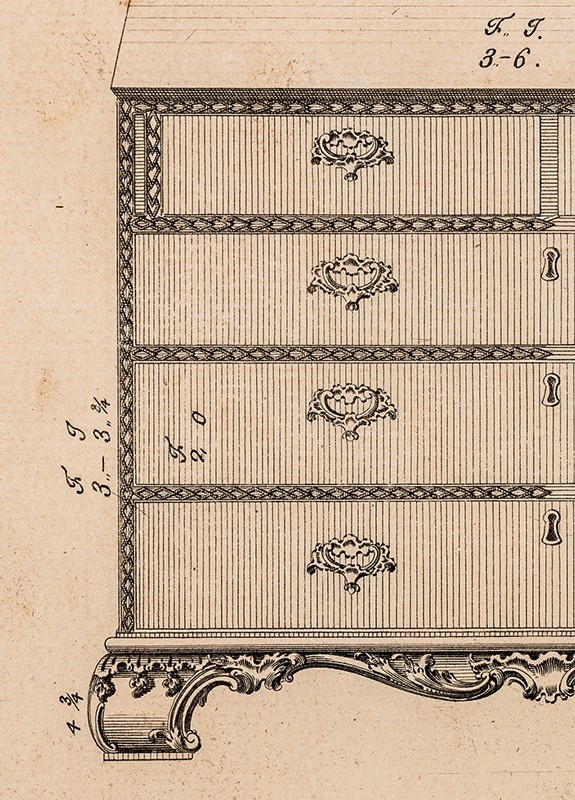

Design for a “Chest of Drawers” shown on pl. 88 of the first edition of Thomas Chippendale’s The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (London, 1754). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library.)

Comparison of the cornice of the chest-on-chest in fig. 40 and the cornice profile also shown on pl. 88 of the first edition of Thomas Chippendale’s The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (London, 1754). (Photos, Gavin Ashworth [left] and Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library [right].)

Comparison of the fretwork on the chest-on-chest in fig. 40 and a detail of the design for “Two New Frets proper for Trays or Fenders” shown on pl. 6 of John Crunden’s The Joyner and Cabinet-Maker’s Darling (London, 1765). (Photos, Gavin Ashworth [top] and Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library [bottom].)

Chest of drawers, Salem area, Massachusetts, 1770–1780. Mahogany with crabwood, basswood, and white pine. H. 34 5/8", W. 36", D. 22 3/4". (Courtesy, The Henry Ford.)

Detail of a design for a “Desk & Bookcase” shown on pl. 80 of the first edition of Thomas Chippendale’s The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (London, 1754). (Photo, Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library.)

Desk and bookcase, Salem-Beverly area, Massachusetts, 1770–1780. Mahogany with white pine. H. 90", W. 40 1/2", D. 24 1/2". (Photo, © 2016 Christie’s Images Limited.)

Desk, Salem-Beverly area, Massachusetts, 1775–1790. Mahogany with white pine. H. 42 1/2", W.46", D. 23 15/16". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the interior of the desk in fig. 47. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the bottom of the chest-on-chest in fig. 40. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the rear foot bracket of the chest-on-chest in fig. 40. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the widely spaced double bead on the drawer side of the chest-on-chest in fig. 40. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the drawer bottom of the chest-on-chest in fig. 40. (Photo, Historic New England.)

Detail of the inscription “John Allen / 1792 [W]ashington Street” on the top of the lower case of the chest-on-chest in fig. 40. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Desk, Salem area, Massachusetts, 1780–1795. Mahogany with white pine. H. 41 3/8", W. 47 1/4", D. 25 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the interior of the desk in fig. 54. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the rear foot bracket of the desk in fig. 54. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Comparison of the front feet of the desks in figs. 35 and 54. (Photos, Michael E. Myers [left] and Gavin Ashworth [right].)

Chest of drawers, Salem area, Massachusetts, 1780–1800. Mahogany with white pine. H. 32 1/16", W. 40 1/8", D. 20". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest of drawers, Salem area, Massachusetts, 1780–1800. Mahogany with white pine. H. 33 1/8", W. 40 9/16“, D. 21". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the numbering (1–4) on the drawer backs of the chest of drawers in fig. 59. (Photos, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the rear corner of a drawer in the chest of drawers in fig. 59, showing that the upper dovetail of the drawer side extends over the back. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the rear corner of the drawer in the chest of drawers in fig. 1, showing that the upper dovetail on the drawer back extends over the side. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Desk, Salem-Ipswich area, Massachusetts, 1780–1795. Mahogany. H. 42 3/4", W. 41 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Sotheby’s.)

Desk, Salem-Ipswich area, Massachusetts, 1780–1795. Mahogany with white pine. H. 43 5/16", W. 42 7/16", D. 21 1/8". (Private collection; photo, Charles White/JWPictures.com.)

Detail of the interior of the desk in fig. 64. (Photo, Charles White/JWPictures.com.)

Desk, Salem-Ipswich area, Massachusetts, ca. 1792. Mahogany with white pine. H. 43 1/2", W. approx. 43", D. 23 1/8". (Private collection; photo, Tremont Auctions.)

Desk, Salem-Ipswich area, Massachusetts, 1780–1795. Mahogany with white pine. H. 43 5/16", W. 44 9/16", D. 22 9/16". (Private collection; photo, New England Gallery advertisement in Antiques 129, no. 4 [April 1986]: 737.)

Detail of the bottom of the desk in fig. 66. (Photo, Tremont Auctions.)

Desk and bookcase, Salem area, Massachusetts, 1780–1795. Mahogany with white pine. H. 95 1/2", W. 41 5/8", D. 24 3/8". (Private collection; photo, Sotheby’s.)

IN JANUARY 1925, New York antiques dealer Charles Morson sold a serpentine chest of drawers to noted collector of early American furniture Mrs. J. Insley Blair (1883–1951) (fig. 1).[1] Pasted on the back of the chest was a tiny, printed label, measuring just one and a half inches in length, which read: “Made and Sold by W. KING, Salem” (fig. 2). The name meant little to the dealer or the purchaser; more likely, it was the unusual swell of the front feet that attracted their attention. The pattern also caught the eye of the editor of the magazine Antiques, Homer Eaton Keyes (1875–1938). In the September 1927 issue of the magazine, he pondered the difficulty of designing a serpentine chest. To Keyes, the challenge lay in the transition from a curved front to the straight sides. To relieve the awkwardness, many craftsmen inserted a canted corner post and set the case on bracket feet, but with limited success. The design usually resulted in “an ugly and seemingly disproportionate bracket foot,” noted Keyes. Cabinetmaker William King (1762–1839), however, adopted a unique solution that featured a swelled block at the top of the foot. Though some might consider King’s design peculiar and ungraceful, Keyes claimed the opposite. “It would be hard to find anywhere in furniture history,” wrote Keyes, “a better example of ingenious and artistic adjustment of transitional lines.”[2]

Keyes’ affection for King’s design led him on a genealogical journey in search of information about the unknown maker. The name William King quickly surfaced in Salem, Massachusetts, town records, and the gossipy Salem minister William Bentley (1759–1819) had sprinkled his diary with fifteen references to King.[3] A picture emerged of a complex figure, acclaimed as an ingenious mechanic but chided as a capricious wanderer, searching for new projects to the detriment of his family obligations. The death of his youngest son, Nathaniel, in 1819 offered a telling account of King’s errant ways. When the court sought to appoint William as the administrator to the estate, they learned that he no longer lived with his wife and “about ten years ago left this part of the country and went to the Southern States and has not been heard of since to our knowledge.”[4] At this juncture, according to Keyes, “the King family receded into [. . .] obscurity.”[5]

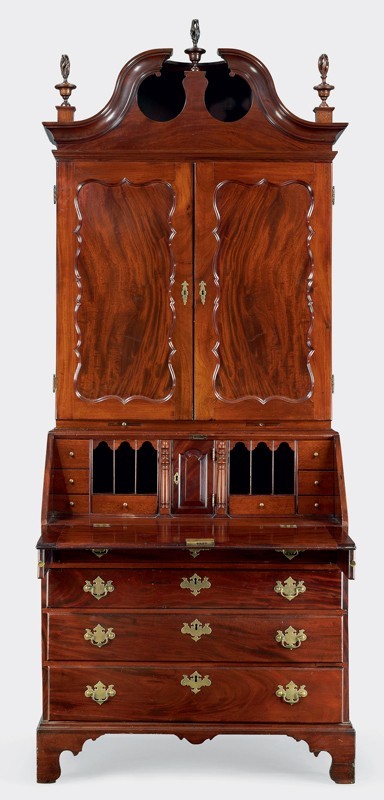

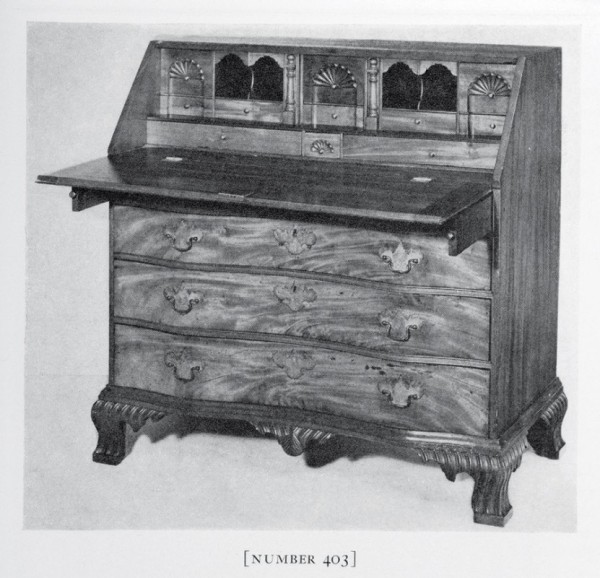

Keyes’ article sparked considerable interest in the talented but tainted artisan. Mrs. Blair received several inquiries from scholars and dealers, and in 1930, a second Antiques article credited King as the maker of a related chest of drawers with an impeccable Salem history (fig. 3). It too displayed a serpentine front with canted corners and a carved pendant drop, although the author, Willard Keyes (1861-1959), staked the attribution on the carving of the feet (fig. 4). He interpreted the band of decorative reeding, termed gadrooning, as a carved version of the bold swell on the front feet of the documented chest.[6] In retrospect, the comparison seems a stretch, considering the obvious difference between the ogee bracket base on one chest and claw-and-ball feet on the other. Yet, the connection to King took hold, and over the next ninety years every Massachusetts case piece with gadrooning along the upper half of the feet acquired an attribution to this single Salem cabinetmaker. This article takes a fresh look at William King and the objects associated with him.

In his portrayal of King, Homer Eaton Keyes relied primarily on the accounts of William Bentley. Recent research has fleshed out a much richer biography. King’s roots in Salem extend back four generations to William King (1595–1649), an English immigrant who traveled to Massachusetts in the Great Puritan Migration of the 1630s.[7] In Salem, the cabinetmaker’s father and grandfather found employment in the shipbuilding trades, working as blockmakers, constructing wooden pullies, called blocks, needed for rigging a vessel’s sails.[8] Perhaps William would have continued in the family trade, but his mother died when he was only about two, and nine years later smallpox took his father’s life.[9] In 1773, at the age of eleven, William King was adrift. He eventually entered into an apprenticeship in woodworking, perhaps with his uncle Gedney King (1740–1814), who practiced the trades of both blockmaking and cabinetmaking.[10] A later connection offers another possibility. In 1785 King married Rebecca Phippen (1759–1825), whose father, David (1715–1782), had prospered as a furniture maker in Salem for forty years. Eighteenth-century examples of a young apprentice wedding his master’s daughter abound. However, in King’s case, when he began his training, David Phippen would have been nearing sixty. He had already taught the trade to his sons, Samuel (ca. 1744–1798) and Ebenezer (1750–1792). If King was indentured to a member of the Phippen family, one of the younger generation was a more likely candidate.[11]

King’s initial apprenticeship was short-lived. The battles at Lexington and Concord sparked open rebellion that soon led to revolution. Soldiers and sailors were needed for the American cause, a call that prompted the first journey of King’s peripatetic career. In November 1787 William Bentley recalled that King, “having been long absent in the West Indies, about four years ago returned.”[12] This venture to the Caribbean began in June 1780, when a William King of Salem, “age, 17 yrs.; stature, 5 ft.; complexion, dark,” signed on as a crew member of the brigantine Addition, a privateer captained by Joseph Pratt.[13] During the Revolutionary War, more than six hundred privateers set out from Massachusetts ports to capture English merchant ships, confiscate and sell their cargoes, and disrupt enemy supply lines. Such voyages were dangerous but, if successful, extremely lucrative for both owners and crew. The Addition stayed at sea for about four months, sailing throughout the West Indies before venturing back to Massachusetts in late October.[14] During one of the stops in the Islands, King probably left the vessel and found work with an established tradesman, most likely an ivory turner. This specialized craft became a staple of his activities once back in the United States.[15]

After nearly three years away, King returned to Salem in late 1783. At twenty-one, he had already traveled widely and seen more than many his age. Beckoning him back home was news of a fortuitous windfall. On October 8 an inheritance of nearly seventy pounds was transferred from his grandmother’s estate.[16] The funds helped fuel his fledging career and young family. His marriage to Rebecca Phippen came just seventeen months later, and their first child, Elizabeth (Betsy), was born in January 1786.[17] During this period, the prominent merchant Elias Hasket Derby (1739–1799) employed the young tradesman for “turning” and other work.[18]

By the early fall of 1787, King’s wandering spirit reappeared, and again Bentley supplied the details: “This W. K. being very capricious, left his family, without any warning, wrote a letter of his intentions to abscond, without being pressed by debt, or any other visible reason.” King had stolen a horse-drawn sulky to make his escape. The owner eventually caught up with him in East Haven, Connecticut, forced the errant craftsman to pay sixteen pounds in damages, and within two weeks King had rejoined his family in Salem. Bentley offers no hint of how King’s wife, who was pregnant with their second child, reacted to the episode, but the minister came to see the artisan’s actions with increasing disdain.[19]

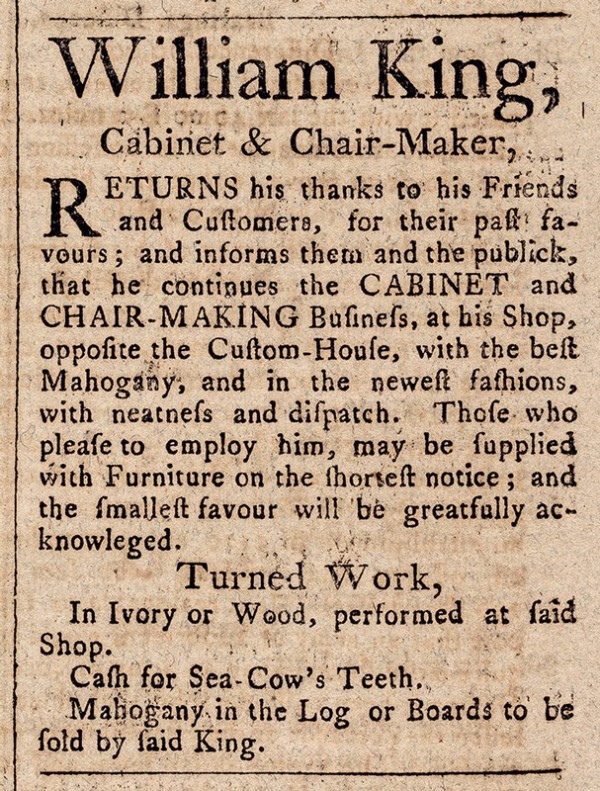

Back in Salem, King took up his trade once again, promoting himself as an ivory turner through a series of advertisements. The first offered such goods as “genteel” canes, billiard balls, dice, chess pieces, and lemon squeezers at his shop across from the dwelling house of Colonel John Fisk.[20] A notice of July 14, 1789, announced the relocation of his business to a passage leading to the Salem Common. At the new site, he carried on “Cabinet Work, in its various branches,” in addition to his usual decorative turning.[21] By 1792 he had moved again, this time to a site opposite the Custom House, where he had for sale “a parcel of Excellent Mahogany in large or small quantities.”[22] He also proposed to hire two journeymen in the cabinet and chair-making business.[23] The next year, he published the most detailed announcement of his furniture operation, noting that “he continues the CABINET and CHAIR-MAKING Business . . . with the best Mahogany, and in the newest fashions, with neatness and dispatch” (fig. 5).[24]

The six-year period from 1788 through 1793 proved to be the heyday of King’s furniture operation in Salem. During this time he ordered two types of printed labels, perhaps from Thomas Cushing (1764–1824), the local publisher of King’s advertisements.[25] His use of labels paralleled the practice of many newly established craftsmen seeking to enhance their reputation in the 1790s.[26] In King’s case, promotion was paramount—but as inexpensively as possible. Both labels are extremely small in size and feature the briefest of messages. He attached one version to the distinctive chest that attracted Homer Eaton Keyes’ attention, as well as to three half-round card tables in the early neoclassical style (figs. 1, 2, 6, 7; see Appendix). For a set of six urn-back chairs, he used a different label, which he glued conspicuously to the rear seat rail of every chair (figs. 8, 9).

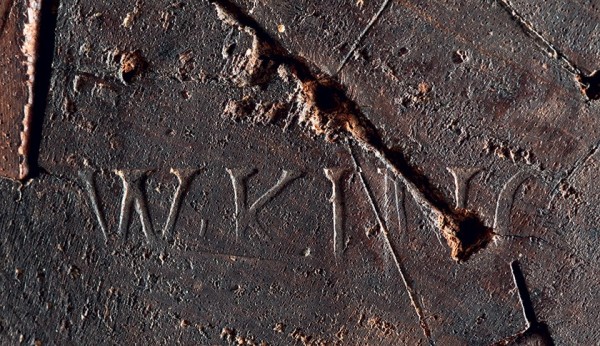

King no doubt labeled many more pieces than these ten objects, but to date no other documented examples have turned up, with one possible exception. The letters “W. KING” appear on the bottom of the turned pillar of a candlestand (figs. 10, 11). Frequently marks of this sort refer to an owner rather than to the maker. However, in this instance, the inscription is an odd one. At the time, most were created with a branding iron, leaving a scorched impression.[27] Here, the name is stamped and the size of the letters is miniscule, much like the type on King’s tiny labels. If this is indeed his handiwork, what prompted the craftsman to place his name on this particular object in this location? Did he decide that a stamp was more secure than a label for this form? The stand does resemble other examples associated with Salem, and certainly King, a talented turner, would have been capable of making pieces such as this.[28] Yet the stamp lacks the certainty of the label. For now, the artisan’s association with the stand remains an intriguing possibility.

William Bentley described another object that King surely made but has since disappeared. In his advertisements the craftsman consistently listed billiard balls among his decorative offerings. Turning a perfect sphere required considerable skill. To build a table on which to play billiards demanded further prowess, which by all accounts King had in abundance. By 1793 he had constructed a billiard table and fitted out a room for gaming. His actions alarmed local leaders. They worried that the youth of Salem had grown too fond of billiards and the gambling that accompanied it. In December officials sought to prevent young men from playing the game. At the time, the town had three billiard tables. Two were in taverns and their use could be controlled. The third belonged to King, and, as Bentley noted, “W. K. is too unprincipled to be restrained without some heavy threatnings [sic].”[29] The diarist never specified the nature or the effectiveness of the threats, but his words do reveal a fuller picture of King’s personality: on the one hand, clever, entrepreneurial, and adept at his trade, but on the other, disruptive, opinionated, and stubborn. These combined traits contributed to a restlessness that governed much of his later life.

Within months of the billiards incident, William King decided to leave Salem to pursue his career in the nation’s largest city, New York. Unlike his earlier escapade, his wife and children joined him, but one wonders how well they accepted the change. Rebecca King had longstanding roots in Salem and many relatives living in the town. Once in New York the family settled into a small residence at 273 Pearl Street, and William advertised as an ivory and wood turner.[30] This stay lasted less than a year; the Kings moved again, this time to Philadelphia, where their situation only became worse. Bentley chronicled the unfortunate circumstances in a diary entry of July 6, 1796: “News from Philadelphia, that Wm King, belonging to a good family in this Town, after having dragged his family from Town to Town, left a note that he was going to drown himself & disappeared. It is supposed that he means to ramble unincumbered. The family are to return to Salem.”[31] At the time, his wife was expecting their fifth child. Might the family obligations have overwhelmed the thirty-four-year-old King? Or was he simply a wanderer, as Bentley later described him, who had to move on, regardless of the consequences?[32]

Whatever the reason for King’s bizarre actions, his decision to “disappear” took him to a new home in Frederick, Maryland, along the Great Wagon Road from Pennsylvania to the Valley of Virginia. There on October 25, 1797, he announced to the “Citizens of Frederick and the Public in general, that he has commenced the Cabinet and Chair making business in Mahogany and other wood, in the newest and most approved fashions.” As in his Salem advertisements, he proclaimed his skill as a turner in ivory, horn, and wood, but added that he had for sale “an excellent Billiard Table, ready finished and furnished with Balls, Cues, and Maces.”[33] Over the next five years, a series of advertisements touted King’s abilities as a furniture maker. In all but one, he sought to hire journeymen or apprentices, suggesting that his irascible temper may have frequently driven workmen away.[34]

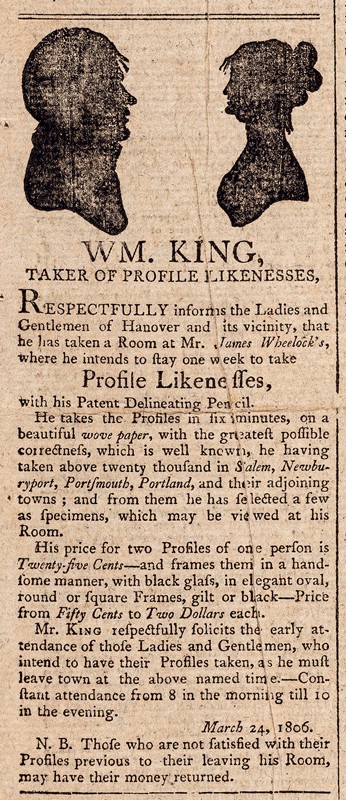

By the fall of 1802, with his business apparently declining, King determined to relocate—and to reinvent himself. He headed back to New England, eventually arriving in his hometown of Salem. In an advertisement of July 22, 1804, he trumpeted a new profession: “WILLIAM KING Respectfully informs the Ladies and Gentlemen of Salem and its vicinity, that he takes PROFILE LIKENESSES, of any size, with the Patent Delineating Pencil, which for accuracy, excels any machine before invented.”[35] The cutting of silhouettes, called profiles, had risen dramatically in popularity after 1800 due to the development of an improved version of a physiognotrace, a device that traced the outline of a person’s profile onto a sheet of paper.[36] King probably based his own model on one that he had seen in Philadelphia or Boston. For the craftsman, profiles offered a new career path, and King leapt at the opportunity.

King’s success depended on self-promotion. To heighten public interest, he flooded Salem newspapers with more than fifty ads in 1804. The following year the blitz continued, with another sixty-five notices.[37] Local demand eventually began to wane, prompting King to embark on an ambitious circuit of New England towns that included a brief stop in Newburyport, and later journeys to Portsmouth, Keene, and Hanover, New Hampshire.[38] By the time he reached Hanover in late March of 1806 he claimed to have taken more than twenty thousand likenesses (fig. 12). He charged just twenty-five cents for two profiles of a person. The process only took five minutes, and with the resulting image, “you may transmit to your posterity a correct likeness in Profile, which often conveys the likeness preferable to the most costly painting.”[39] After a week in Hanover, he returned to Massachusetts and moved his business to Boston for the second half of the year.[40] While in the city, he supplemented his income by staging an illuminated panorama depicting American ships bombarding Tripoli, the most famous incident of America’s undeclared war against the Barbary pirates. Painted by the Italian immigrant Michele Felice Cornè (1752–1845), the sprawling canvas measured ten by sixty feet. With classic marketing savvy, King opened his “real Feast for an American Patriot” on Thanksgiving Day.[41] King peppered local newspapers with dozens of announcements celebrating the grandeur of the work. The display in Boston became the first stop in a multi-city tour stretching from Portland to Providence. At every destination, King relied on a continual wave of advertisements to attract an audience.[42] The scale of his promotional campaign set him apart from his competitors and revealed his flair for showmanship, a trait that became even more evident as he remade himself once again.

In the summer of 1807 King cast an eye toward new horizons, venturing southward to Rhode Island and Connecticut. Profile likenesses remained a focus at first, but ever the entrepreneur, he briefly managed a “Bathing-House” in Providence before turning to a new passion: electricity.[43] He built an electrical machine and galvanic battery and started to lecture about the nature of electricity through “a Number of surprising, curious, and pleasing Experiments.”[44] Parts of his performances were pure theater. During one evening’s entertainment in Norwich, Connecticut, he lit a candle with an electric spark that passed through water, exhibited an “electrical orrery,” which traced the movement of planets around the sun, and illuminated the “name of the departed patriot WASHINGTON” with electric “fluid.”[45] Science served as a basis for many of his experiments, but fact gave way to quackery when King moved into the medical benefits of electricity. His advertisements promised “great” relief or complete cures through electrical therapy that “is both pleasant and efficacious, and has had the approbation of many eminent Physicians.”[46] For almost anyone in need of help, he had a remedy regardless of the malady. From burns, scalds, and bruises to deafness and madness (and so much more), King offered healing at a cost of twenty-five cents if the patient came to him or a dollar for a house call.

William King was by no means unique in his fascination with electricity. During the early nineteenth century, numerous itinerants brought electrical exhibitions to communities across the country.[47] In most cases, these rambling showmen went out on the road for a few years before moving on to other pursuits. King’s interest in the subject, however, never flagged. Nor for that matter did his wandering ways. In 1810 he relocated to the southern states, residing for a time in Charleston, South Carolina.[48] By 1825 he had settled in New Bern, North Carolina, assumed the title of “Dr. King,” and published A Manual of Electricity.[49] Two years later the Carolina Sentinel reported “with much pleasure, that Dr. King intends giving an Experimental Lecture on Electricity and Galvanism,” adding that “when we consider the unceasing and unwearied endeavors of the Doctor, for the promotion of science, and the success which has heretofore attended his labors, we feel assured that to such of our citizens as attend, the exhibition must prove, in the highest degree, interesting.”[50]

King’s sojourn through the South came to an end about 1830, when he returned to New England and rented a house in Boston.[51] Though now nearly seventy, he established an active business, making electrical machines, galvanic batteries, and lightning rods.[52] His work on electromagnets garnered widespread attention. An account in a St. Louis newspaper claimed that King was on the verge of completing “the largest electro magnet, probably, in the world,” noting that this “will be the most magnificent philosophical instrument ever constructed in America, or, perhaps, in any country.”[53] His shop became a focal point for the electrical craft, attracting assistants such as Daniel Davis (1813–1887), who later became a national leader in the manufacture of electromagnetic equipment.[54] When King died on March 13, 1839, at the age of seventy-seven, obituaries hailed him as the “distinguished” and “celebrated” electrician. He left behind a fully outfitted shop filled with apparatus of every sort, from batteries and gasometers to microscopes and galvanic magnets, as well as two items—a profile machine and a turning lathe—that harkened back to earlier moments in his career.[55]

Writing in 1809, William Bentley described William King as an “ingenious mechanic,” but “full of projects, & what he gains from one, he loses in another.”[56] Bentley’s comments highlight the contradictions in King’s life. Exceptional craft skills and intellectual curiosity were readily evident, but so were ambition, self-promotion, and a rebellious spirit. King struggled to keep apprentices or journeymen while he was a young woodworker but attracted talented associates during his later years in Boston. He understood the science of electricity and built practical pieces of equipment, but he espoused quick electrical cures for almost any ailment. He profited from his work as a profile artist and electrician but owned little property, aside from the contents of his shop, and died in debt. He trained and briefly employed one of his sons in the art of taking profile likenesses but abandoned his family for the last thirty years of his life. King left behind no written account of his colorful career; instead, evidence of his character is based upon the hyperbole of his advertisements and the comments of others. In many respects, he remains an enigma.

The most tangible testimony of his skill as an artisan comes from his profile likenesses and furniture. Dozens of profiles bearing the stamped signature KING or W. KING are scattered throughout New England museums and libraries (fig. 13). The quality of the work drew praise from collector and author Alice Van Leer Carrick (1875–1961), who wrote in 1928 that “King is one of my favorite hollow-cutters . . .he has a knack of seeing people agreeably.”[57] A year before, his furniture met with equal favor from Homer Eaton Keyes, as recounted at the outset of this article. Over time the chest that Keyes extolled served as the basis for ascribing numerous case pieces to King (see Appendix). Careful scrutiny of these objects reveals, however, that King belonged to a much larger cluster of craftsmen in Salem working in similar ways.

The feature that defined the supposed King items was a distinctive pattern of carved gadrooning on the feet (fig. 4). Though the labeled chest in figure 1 lacks such carving, earlier writers viewed the exaggerated swell of the knees as an undecorated version of the technique. Assuming for a moment that King did create furniture with gadrooning, a quick glance at the carved patterns on the pieces reveals too many variations to be the work of a single craftsman (fig. 14). Differences in case construction reinforce the attribution to multiple shops. In addition, the range in design elements and brass hardware suggests that the earliest and latest pieces in the group extend well beyond the years 1788 to 1793, the period when King made furniture in Salem. Rather than the product of one artisan, these case pieces represent the efforts of at least six cabinetmakers, beginning as early as about 1770 and probably continuing until 1800. The signature trait of the group—the carved gadrooning on the feet—owes its origin to an ornamental detail first pictured in 1754 in Thomas Chippendale’s handsome folio volume, The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (fig. 15).[58]

Object Study

For this study, the authors located forty-two pieces of furniture with possible connections to King, of which they examined thirty-eight: fifteen desks, two desk and bookcases, eleven chests of drawers, a chest-on-chest, a candlestand, two card tables, and a set of six chairs (see Appendix). As the project progressed, four discrete groups of case furniture emerged, suggesting the output of four separate shops. However, the labeled King chest did not share the combination of characteristics that placed it in any of those four groups. Five additional objects also varied sufficiently from the rest to place them outside the groups, thus suggesting an even wider population of craftsmen who adopted the carved gadrooned foot (Appendix: Group 5).[59] The assessment established King’s known surviving output of case furniture to a single object, the labeled chest in figure 1. Undoubtedly he made more, but none of the pieces traditionally tied to him matched the chest in construction. This discovery led to a greater understanding of the cabinetmaking scene in the Salem area during the last quarter of the eighteenth century. Furniture hitherto associated with William King could be linked to other shops, and in one case a specific craftsman.

The identification of these shops as distinct from the work of William King began with a thorough analysis of King’s labeled chest. Aside from its unusual front feet, its design follows a popular form of the time, with its serpentine front, canted corners, and shaped top. The London firm of Ince and Mayhew depicted a similar chest, called a “Comode Chest of Drawers,” in their 1762 publication The Universal System of Houshold [sic] Furniture.[60] American versions appeared in coastal communities from Portsmouth, New Hampshire, to Charleston, South Carolina.[61] In the Salem area, cabinetmakers sometimes added a carved shell with scrolled volutes at the center of the base molding. The version on the chest by King matches those on reverse-serpentine desks by Elijah Sanderson (1751–1825) of Salem and the Knowlton family of woodworkers in nearby Ipswich.[62]

King’s construction practices can be thoroughly documented thanks to the exceptional condition of the chest. Nearly every original element remains intact, revealing that King generally worked in a manner consistent with that of other Salem craftsmen at the time. He formed each case side of three mahogany boards, choosing a thicker front board to create the swell for the canted corner. The sides are dovetailed to two pine slats at the top and a solid two-board pine bottom (fig. 16). Screws are driven through the slats (three per slat) and sides (one per side) to secure the mahogany top. Shallow dividers are fastened to the case sides with sliding dovetails. Strips of mahogany veneer cover the front edge of the sides. Behind the dividers, drawer supports are nailed to the case sides. Long, narrow vertical blocks glued at the back corner of the case serve as drawer stops. At the base, the bottom drawer runs on a lower front rail and strips glued to the case bottom along the sides. On the underside of the case, the base molding extends below the bottom and is backed with a series of contiguous glue blocks (fig. 17). A thick, rounded piece of pine reinforces the carved pendant shell. Though the front feet differ dramatically from the norm, their supporting structure conforms to a standard pattern. Smaller, horizontal blocks flank a vertical block behind each front foot. At the rear, the shape of the back bracket follows a conventional outline (fig. 18).

For the serpentine surface of the drawers, King adopted a process common on case furniture of the Federal era, gluing mahogany veneer to a pine laminated core (figs. 19, 20). He covered the edges with a cock bead, but at the corners the bead caps only the front portion of the dovetails. Each drawer bottom consists of three boards with the grain running front to back. The bottom is set into a groove in the drawer front and sides and is fastened to the back with rose-head nails spaced about four inches apart. Neither the drawer bottom nor sides are reinforced with support blocks or strips. The top edges of the drawer sides are flat (rather than rounded or beaded) and are set below the top edges of the drawer fronts, creating a slight “step.” Overall, the construction is in keeping with most Salem furniture: neat, efficient, and competent.

Group 1

As discussed above, in 1930 Willard Keyes attributed the chest in figure 3 to William King, and for nearly a century subsequent writers have associated Massachusetts case pieces with gadrooned foot carving to King.[63] The connection proved spurious. This second chest deviates in several ways from King’s labeled example in figure 1 and, instead, is part of a significant group of Salem furniture attributed to the shop of Thomas Needham Jr. (1755–1787). The term “shop of” is used because of the size of his business. Needham’s workspace contained “4 Joyners Benches,” which would have accommodated at least two journeymen in addition to the master. No doubt these artisans relied on the stockpile of “Patterns” in Needham’s possession, but their finished products varied slightly depending on the skills of the individual, the availability of fine lumber, and the customer’s desire for excellence (and the pocketbook to pay for it).[64]

The key to the Needham connection is a chest of drawers initialed and dated “TN 1783” (figs. 21, 22). On October 11 of that year the younger Needham billed Salem’s wealthiest patron, Elias Hasket Derby, the substantial sum of £18 for a “Bruro [Bureau] Mahogne table,” which almost certainly refers to this chest.[65] By comparison, other Salem craftsmen charged £6 for a mahogany “Bureau Table” in 1782 and £7.10.0 for a “Swelld mehogany Figure bureau” in 1788.[66] The design of the Derby chest resembles that of the example in figure 3 but with earlier stylistic features. The drawers lack string inlay, and the hardware follows a popular Chippendale pattern. Vertical strips of classic oval-and-diamond fretwork cover the canted corners, and thick, swirling rococo foliage decorates the central drop.

The craftsmanship demonstrates the Needham shop’s attention to detail. Striking, figured mahogany was selected for the case, eight perfectly proportioned ovals filled the fretwork, and the feet and drop were meticulously carved. The commitment to quality continued in hidden areas. Within the case, full-depth dustboards were set between the drawers, a practice common in English furniture but rarely adopted by New England artisans.[67] The cock-beaded drawer fronts were joined to the sides with narrow, uniformly sawn dovetails.[68] Pine blocks were carefully cut and shaped to support the feet. From top to bottom, the chest is a tour-de-force of colonial cabinetmaking. No other piece of Salem furniture of its time displays such painstaking precision. Justifiably proud of the product, Thomas Needham took the rare step of documenting his work for posterity.[69]

While singular in its exacting craftsmanship, the Derby chest relates to at least ten other case pieces. The most similar is a serpentine chest that belonged to antiquarian Luke Vincent Lockwood in the early twentieth century (fig. 23). The individual details resemble those on the documented chest, but their fabrication lacks the same level of finesse.[70] On another serpentine chest, the maker chose broad ogee feet and abandoned a central drop along the base molding, giving the object a decidedly English accent (fig. 24). Three examples display gadrooned carving on the feet. Histories of ownership connect each piece to a prominent Salem personality. The serpentine chest in figure 3 belonged to the merchant George Crowninshield Jr. (1766–1817) and was among the furnishings of his yacht, Cleopatra’s Barge.[71] A reverse-serpentine chest resided in the home of ship captain George Ropes (1765–1807) and may have been the “Bureau” valued at $7.50 in his estate inventory (fig. 25).[72] The third item, a reverse-serpentine desk, is linked to the noted public figure Timothy Pickering (1745–1829) (fig. 26).[73] Rounding out the group of Needham furniture studied for this article are four desks and a bowfront chest of drawers (figs. 27, 28; see Appendix: Group 1).

Numerous features characterize the standard work of the Needham shop. Customarily, fine, richly grained mahogany was selected as the primary wood (fig. 30).[74] On examples with claw-and-ball feet, the ankle descends into the extreme rear of the ball. The claws display sharp, pronounced knuckles, and the side claws rake back at a slight angle (fig. 4). When carving the rear feet, the craftsman typically left the back surface undecorated (fig. 29). On case furniture with ogee feet, he joined the back bracket and foot with a vertical sliding dovetail and reinforced the unit with blocks glued to the bottom. At the center of the front base molding, he often glued a carved drop (the chest in figure 24 illustrates a rare exception). The patterns varied, but the most common featured a C-scroll above three pierced ovals and a rippled lower edge (fig. 31).[75]

Inside the case, Needham or a member of his shop frequently inserted a vertical batten at the center of the back that he tenoned through the case bottom (fig. 32). He attached a front rail above the base molding and glued strips to the case bottom along the sides, and on several examples he joined the front base molding to the case bottom with a large dovetail. Beneath the case bottom, a series of thin blocks of varying lengths supported the base molding and feet (fig. 33).[76] Similarly, on the underside of drawer bottoms, he customarily glued small blocks at the sides and front (fig. 34). When constructing the drawers, he usually followed a standard Salem practice of setting the bottom into grooves in the sides and front, with the grain of the wood running from side to side.[77] At the back, he preferred to fasten the bottom with widely spaced rose-headed nails (about six per drawer, compared to eight to eleven per drawer for the chest labeled by King in figure 1). Unlike many Massachusetts makers of mahogany desks, Needham rarely installed document drawers (fig. 27). The resulting interior is plainer than most. Decoration is limited to a carved fan in the prospect section, flanked by a pair of pigeonholes and an outer fan-carved drawer.

Thomas Needham Jr. died suddenly in March 1787 at the age of thirty-one.[78] His career was brief but distinguished. He likely learned his trade from his father, Thomas Sr. (1734–1804), who worked in both Salem and Boston and is associated with a small group of stylish bombé furniture.[79] In the midst of his apprenticeship, the young Needham witnessed firsthand a family tragedy when fire destroyed his father’s shop in 1774.[80] The outbreak of the Revolution brought further disruption. Thomas Sr. served three years in the Continental Army, while his son managed the family business.[81] Orders waned during the early years of the war, but improving conditions in the 1780s sparked a wave of commissions. Several of Salem’s more prominent citizens sought out the younger Needham and, judging from the chests he made for Derby and the Crowninshield family, his skills were exemplary. He had begun to embrace elements of the new neoclassical fashion, such as string inlay and the bowfront facade. The latter appears on an intriguing chest signed “Thoma[s]” in Needham’s hand (fig. 28). Like many tradesmen who died at a young age, Needham left an estate with far more debts than assets. His strong local connections and craft competence had made him a worthwhile risk. Over time he accumulated numerous obligations, which suddenly became due with his unexpected passing. The estate faced claims of nearly £400 from thirty-three individuals, forcing his widow Lydia to sell his possessions at auction. The proceeds covered only a fraction of his debts.[82] Though he died insolvent, Thomas Needham and the artisans employed in his shop achieved an enduring legacy, fashioning some of the finest furniture made in Salem on the eve of the Federal era.

Group 2

A more complicated picture emerges when considering another group of case pieces with gadrooned feet. William King has long been tied to three closely related desks (figs. 35–39). All have shaped facades, similar interiors with a sham arched panel on the prospect door, and identical ogee bracket feet.[83] Unlike the gadrooning on the feet of the Needham examples, which covers the brackets and extends onto the concave curve of the foot, the knee carving on the three desks is truncated, with the lower edge of the gadrooning sloping downward at a slight angle (fig. 14E). At the base of the foot, the ogee flows into a thick pad. The combination of these elements—gadrooning, ogee curves, and pad—closely replicates the feet on Thomas Chippendale’s design for a desk and bookcase (fig. 15).

Through construction similarities, these three desks can be attributed to a larger group that, while varying in appearance, emanated from the same shop. The chest-on-chest in figure 40 bears little resemblance to the three desks, yet it too was inspired by London design books.[84] The overall plan of the double chest conforms to the left side of plate 88 of Chippendale’s Director (fig. 41). Even the profile of the cornice follows the exact outline drawn by Chippendale (fig. 42). A band of Chinese fretwork appears below the waist molding, a decorative detail again borrowed from the Chippendale plate (fig. 41). The position of the fret probably guided the Massachusetts maker in his design, but he apparently found the pattern itself too intricate to copy. Instead, he chose a simpler version, shown in another London publication, The Joyner and Cabinet-Maker’s Darling, designed and engraved by John Crunden (ca. 1741–1835) in 1765 (fig. 43). A local bookseller advertised both Chippendale’s and Crunden’s volumes in the Boston Evening Post on October 16, 1766, and presumably soon afterwards copies had entered Salem collections.[85] The estate inventory of cabinetmaker Nathaniel Gould (1734–1781) listed “Chipendales Designs,” followed by “Sundries of Books,” which might have included Crunden’s smaller pocket-size publication.[86] Other craftsmen in Salem must also have had access to these volumes, for the construction of this unusual chest-on-chest differs significantly from Gould’s documented case furniture. Interestingly, a chest of drawers with a fret of similar design has gadrooned feet and was previously associated with William King (fig. 44). In this case, Chippendale’s influence is even more pronounced. Strips of diamond-shaped ornament around the drawers are likely based on plate 80 of the Director (fig. 45). The chest’s distinctive construction and unusual woods distinguish it from any other object within this study. It is an intriguing anomaly.[87]

Three other case pieces, comprising a desk and bookcase, bombé desk, and blockfront desk, can be placed in Group 2, since they share the same distinctive construction practices (figs. 46–48; see Appendix). Within the group, the two double forms rank as the earliest and almost certainly date from the 1770s.[88] Both examples display identical straight bracket feet and similar uncarved central drops. In addition, the support blocking for the feet conforms. Continuous strips back the lower edge of the front and side base moldings, instead of the segmented blocks on Needham’s cases (compare figs. 33 and 49). The outer surface of the horizontal blocks reinforcing the feet is rounded, rather than square. At the back, the shape of the rear bracket resembles that of the labeled King chest but with noticeable differences (compare figs. 18 and 50). On the Group 2 forms, the diagonal edge of the rear bracket descends within two inches of the floor before extending horizontally in a gradual arc to the bottom of the rear foot. A vertical block with a slight bevel along one edge is set against the foot and behind the rear bracket.

The drawer construction of the two early double case pieces is also consistent. Thumb-nail molding edges the drawer fronts. The shape and layout of the dovetails match. The top edge of the drawer sides is cut with a widely spaced double bead, while the back is flat (fig. 51). The bottom of most drawers consists of three boards with the grain running perpendicular to the front. Between twelve and fourteen nails bind the bottom and back, a much more tightly spaced arrangement than on drawers by King or Needham (compare figs. 52 and 34).

The shaped facades of the three desks with gadrooned feet suggest that the pieces were made in the 1780s or possibly later (figs. 35, 37, 39).[89] Yet the majority of their features matches those of the earlier chest-on-chest and desk and bookcase. Foot and case constructions align. The distinctive desk interiors with narrow, arch-paneled prospect doors are nearly interchangeable. In every instance, the original lopers that support the lid are made of solid mahogany rather than the customary white pine or native hardwood faced with mahogany. Even the small detail of nailing the sides of the document drawers to the front, back, and bottom is consistent. Other craftsmen often trimmed the front edge of the sides and slipped them into slots in the vertical strip behind the pilaster. These objects almost certainly represent the work of a single maker. Given the range in dates of the furniture, he probably continued at his trade for at least twenty years, from about 1770 to 1790.

Unlike the Needham pieces, the artisan who crafted this second group remains an enigma. None of the pieces is signed and only one, the chest-on-chest, retains an extended provenance. The top of the lower case is signed in florid script “John Allen,” and on the line below “1792” appears followed by the words “[W]ashington Street” in a different hand (fig. 53). The inscription most likely refers to the shopkeeper, John Baxter Allen (1751–1836), who was born in Boston but by the early 1780s had relocated to Beverly, a coastal community adjacent to Salem. In 1792 the affluent Allen and his family moved into a fashionable neoclassical house in the town.[90] The date on the chest probably documents the transfer to the new residence of an object constructed about twenty years before. The information sheds light on an early owner, but not the maker.

Adding to the mystery is the maker’s access to English design books. New England furniture inspired by Chippendale’s Director is exceedingly rare. Of the hundreds of woodworkers throughout the region during the second half of the eighteenth century, only three turned to the book for an entire design. Salem cabinetmaker Nathaniel Gould possessed a copy and based a set of chairs on a specific pattern.[91] Other plates guided the maker of the chest-on-chest and a second craftsman who built the related chest of drawers at The Henry Ford museum (fig. 44). How did the latter two artisans obtain the Director? The substantial cost of Chippendale’s handsomely illustrated folio (far more than that for thin, pocket-size volumes such as Robert Manwaring’s The Cabinet and Chair-Maker’s Real Friend and Companion) limited its distribution. Just four copies can be documented in Massachusetts: three in Boston and Gould’s copy in Salem.[92] The latter seems a possible source for the maker of the chest-on-chest, because he probably worked in or near Salem.

Group 3

Another cabinetmaker crafted a third group of case furniture once linked to William King. The best-known example, a serpentine-front desk owned by noted collectors Mr. and Mrs. George Maurice Morris, appeared as the frontispiece in the November 1944 issue of the magazine Antiques (figs. 54, 55). “It is one of those rare pieces,” noted the editor, Homer Eaton Keyes, “which are sufficiently typical to be representative of their period, yet sufficiently above the average to be fine, and sufficiently unusual to be exciting.”[93] Keyes praised the gadrooning at the base, noting its similarity to that on the Crowninshield chest in figure 3 and, by extension, the unusual swelled knees of the labeled example by William King in figure 1. The construction of the Morris desk and King’s chest, however, reveals the work of different artisans. The shape of the rear brackets is one obvious variation. Long, triangular elements support the back corner of the desk, unlike the distinctive brackets cut with a concave curve on the King chest (compare figs. 56 and 18).

The feet of the desk provide a connection to the three desks in the previous group (figs. 35, 37, 39). They feature the same distinctive ogee outline and convex pad at the bottom. Yet the carving on the Morris desk is more accomplished, with rounded tips to the gadrooning and a wavy line along the lower edge (fig. 57). Within the case, the drawers slide on support strips and a lower front rail, rather than directly on the bottom of the case. The lopers for the lid follow the standard pattern of white pine faced with mahogany, instead of a single board of solid mahogany. Behind the lid, the maker opted for a stepped arrangement, with a lower tier of drawers projecting beyond the rest of the interior (fig. 55). The prospect section never had a door; instead, two drawers filled the compartment, flanked by sham document drawers with plainly turned pilasters.

The desk’s interior drawers are numbered, and the delineation of these numbers indicates it was made in the same shop as two chests of drawers with gadrooned foot carving (figs. 58, 59). On the back of each long drawer of the chests, the maker quickly scrawled a number—1 through 4. Their outlines match those on the interior drawers of the desk. The “1” is the most distinctive, leaning at a pronounced angle and ending with a curl (fig. 60). While many craftsmen numbered drawers as part of the construction process, the consistency of these particular shapes serves, in essence, as the marker of a single artisan.[94]

From a distance, the two chests have little in common. One rests on thicker, more substantial ogee feet and has a large drop at the center of the base molding. The other displays a bolder but lighter pattern for the feet and never had a central pendant. Other features, however, tell a different story. Both chests have tops with an unusually broad overhang at the sides and back. The profile of their base moldings is identical. As in the desk, triangular rear brackets stretch almost to the center of the back, and the drawers are of equal height rather than graduated. Finally, all three pieces display the same peculiar pattern of dovetailing. At the rear corner of every drawer, the side extends over the top dovetail (fig. 61). Customarily the order is reversed, with the back capping the dovetails (fig. 62).

A common origin for the desk and two chests seems certain. Histories of ownership tie the pieces to Salem, but, like the second group of furniture formerly attributed to William King, the identity of their maker remains unknown.[95] The small sample associated with the third group may indicate that the artisan worked for only a brief time. His use of reverse-serpentine facades, combined with drawers of equal height, place him near the end of the eighteenth century.[96]

Group 4

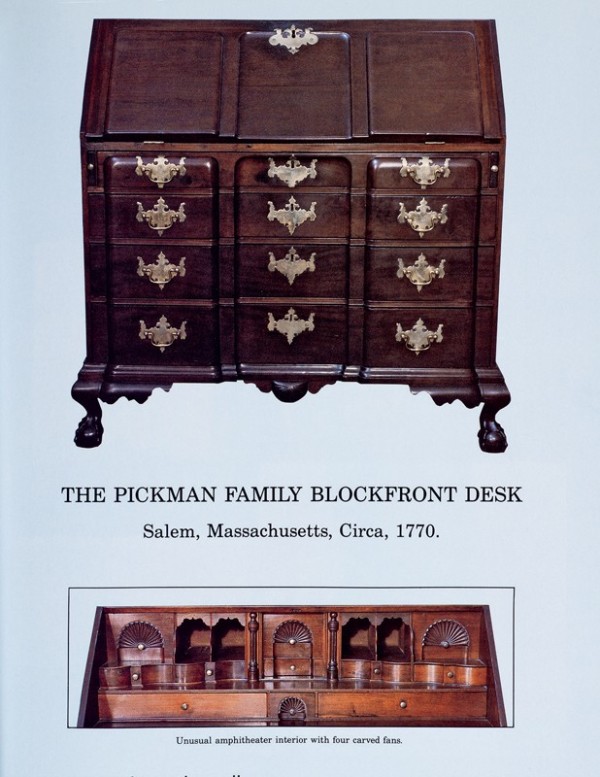

In 1950 Parke-Bernet Galleries offered a “Rare Chippendale Shell-Carved Mahogany Yoke-Front Slant Desk with Gadrooned Base” (fig. 63). The auction catalogue noted the desk’s relationship to the desk in figure 54.[97] Indeed, the reverse-serpentine facade and stepped interior do recall similar features on the previous example, but the layout is more ornate. Carved fans ornament four drawers. The most notable is the small fan at the center of the lower tier, a detail not seen on the other desks previously attributed to King. At the base, the carving on the feet adds another distinctive touch. Unlike other pieces once linked to King, the gadrooning extends the entire height of the foot.

While the current location of the desk remains unknown, the auction image alone presents a crucial clue in connecting the desk to three examples with shaped facades and claw-and-ball feet (figs. 64–67). Like the Parke-Bernet desk, the other three feature a stepped arrangement with a small carved drawer below the prospect section. At the base, two of the desks display a distinctive scallop shell, resembling that on the piece sold in 1950, though without gadrooned carving (figs. 64, 66). These two desks also share numerous structural details. When open, the lid rests on solid mahogany lopers. The tongue-and-groove joint binding the cleats and central board of the lid is exposed. At the base, the central drop is a single element that never had a reinforcing block behind it. Unlike most Salem case furniture, the underside of the base molding is flush with the bottom (fig. 68). The feet are tenoned into the bottom and held in place by the undulating knee brackets and thin blocks behind them. The layout proved insufficient, requiring later repairs to the feet.[98]

Inside the case, an array of attributes links both desks with a more ambitious blockfront example (fig. 67). A giant dovetail binds the base molding to the case bottom. The bottom drawer runs on the base molding and support strips glued to the case bottom. On every drawer, the rear dovetails extend beyond the drawer back, and the top edge of the drawer sides is rounded. In addition, a distinctive double ogee curve decorates the top edge of the sides of document drawers of the two blockfront desks. This combination of details unites the three desks into a group that likely includes the version sold at auction in figure 63. All relate to Salem case pieces of the late eighteenth century. The knee brackets and carved drop are reminiscent of Nathaniel Gould’s work; however, they lack the same refinement.[99] The same is true of the prospect door on one desk. Instead of the gracefully arched panel used by Gould, the maker crowded a square panel with an exceedingly broad bevel into the space (fig. 65). Shared decorative elements abound, but some, such as the large carved fan on a desk lid, are unusual features rarely seen on Salem furniture. In addition, the quality of the mahogany fails to match that on the town’s best examples.

While this group could represent the output of a less skilled Salem craftsman, a more likely explanation points to an artisan outside the community. The history of one piece offers a possible site (fig. 66). An early ink inscription on the side of a drawer records the name of Barnabas Dodge (1740–1814) and the date “1792.” A prosperous farmer, mill owner, and real estate speculator, Dodge resided for most of his life in a section of Ipswich that became the town of Hamilton near the end of the century. He probably purchased the desk at about the time of the inscription. When he died in 1814, his estate included a “Mahogany desk,” which may refer to this example.[100] Hamilton lies about ten miles north of Salem. Perhaps the cabinetmaker responsible for this group resided there or in nearby Ipswich. The latter community supported numerous woodworkers for much of the eighteenth century, but declining commercial activity prompted many to depart after the Revolution, leaving behind a small enclave of cabinetmakers.[101]

Conclusion

William King’s woodworking career in his hometown of Salem lasted less than a decade, beginning in 1783. Initially an ivory turner, he added furniture making to his repertoire by 1788 but quickly discovered keen competition within a community of craftsmen, whose numbers were escalating rapidly. Jacob and Elijah Sanderson from Watertown, the Appletons and Knowltons from Ipswich, along with more than a dozen other cabinetmakers, transformed Salem into a major center of furniture production. King’s advertisements and labels demonstrate his commitment to self-promotion, but ultimately promotion alone was not enough. He soon shed cabinetmaking in favor of other opportunities. It seems unlikely that he did so because of lack of skill. The diarist William Bentley described him as “an ingenious mechanic,” and his documented furniture reveals the hand of a capable craftsman. Others with similar talent persisted far longer in the trade. Debt was a frequent precursor to change, but there is no evidence that King had financial troubles during his years in Salem. Instead, King’s own temperament may explain his decision. Bentley called him a “Wanderer,” a man prone to “pilgrimages” and “full of projects.”[102] An ambitious, independent, and inquisitive spirit seemed to have propelled his actions. Pride, stubbornness, and a flair for the dramatic must have also played a part. The result was a man on the move. After a stint in the West Indies during his teen-age years, his peripatetic travels took him from Nova Scotia to South Carolina and numerous points in between. His connections to family became increasingly distant over time, as he shifted careers with chameleon-like ease, from mariner to ivory turner, then cabinetmaker, silhouette artist, impresario, “Philosophical and Medical Electrician,” and finally the renowned “Dr. King.”[103]

Regarding King’s furniture, aside from its unusual front feet, his labeled chest of drawers falls within the mainstream of Salem design. King adapted a popular English (and later Salem) pattern with a serpentine front and canted corners, but he abandoned the normal plan of continuing the canted surface down the entire foot. His solution—a broad three-sided swell above a standard ogee foot—is unique. Beginning in 1930, writers have linked this distinctive composition to feet with gadrooned carving. This supposed connection prompted the authors to study the many pieces of furniture that have been attributed to King. The process yielded an unexpected result: the presumed relationship has no foundation, and the surviving Salem-area case pieces with gadrooned carving were made in other shops.

Variations in the gadrooning point to the complexity of the cabinetmaking trade in the Salem area. This paper has highlighted four groups of furniture, each of which includes case pieces with gadrooned foot carving. At this writing, only one group can be associated with a specific craftsman: Thomas Needham Jr. The others probably represent the output of shops within Salem or the nearby towns of Ipswich, Hamilton, or Beverly. Much has been written about the furniture of this region. Publications document the work of John Chipman, William Appleton, Edmund Johnson, the Sandersons, and several others.[104] Yet the creations of so many more remain a mystery. Who, for example, might have crafted a stately desk and bookcase with gadrooned feet that stands as a singular expression, outside of any identifiable group (fig. 69)? The historical record identifies upwards of a hundred cabinetmakers in coastal Essex County during the years of the Early Republic.[105] Through deeds, estate inventories, tax lists, scattered receipts, and vital statistics, hazy pictures emerge of these little-known figures. Further archival research and object analysis offer the opportunity to associate these artisans with surviving furniture and ultimately to present a far richer picture of the history of craft in the region.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors thank Claire Kegerise for her research assistance in the preparation of this article.

Furniture Associated with William King (1762–1839)

Labeled or stamped by William King

1. Card table, circular top, straight legs with fluting, labeled “Made and Sold by / W. KING, / Salem.” No early history; sold by John Walton Antiques, New York, ca. 1974, Decorative Arts Photographic Collection (DAPC), 74.6229, Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library; current location unknown; studied through photos.

2. Card table, circular top, straight tapered legs with fluting, labeled “Made and Sold by / W. KING, / Salem.” Descended in the Partridge family of Salem, Massachusetts, and Preston, Connecticut; American Furniture and Decorative Arts, sale no. 2011 (Bolton, Mass.: Skinner, August 12, 2000), lot 141; current location unknown; fully studied.

3. Card table, circular top, straight tapered legs with fluting, labeled “Made and Sold by / W. KING, / Salem.” No early history; sold by Roberto Freitas American Antiques and Decorative Arts, 2022; private collection; fully studied, figs. 6, 7.

4–9. Side chairs, vase back, straight tapered legs, based on pl. 5, A. Hepplewhite and Co., The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Guide (London: I. and J. Taylor, 1788), labeled on the rear seat rail “WILLIAM KING / Cabinet & Chair Maker, / SALEM, / State of Massachusetts.” Every chair in the set is labeled. Two display the label in figure 9; two others feature a label with the same wording as the illustrated example but with a slightly different border. The labels on the two remaining chairs are badly abraded and illegible. Each chair is also inscribed in pencil on the inside of the front seat rail “Mr. Chas Brown,” “Mr. C Brown,” or “Chas Brown.” Possibly owned by Charles Brown (1796–1856) of Beverly, Massachusetts, son of Moses Brown (1748–1820) and Mary Bridge (1760–1842); acquired by the Thorndike family, passing from Augustus Thorndike (1863–1940) to Augustus Thorndike Jr. (1896–1986) to his daughter Sarah Emlen Thorndike Haydock (1929–2008) to the present owner, a Thorndike descendant; private collection; fully studied, figs. 8, 9.

10. Chest of drawers, serpentine facade with canted front corners, swelled upper portion of ogee bracket feet without gadrooning, labeled “Made and Sold by / W. KING, / Salem.” No early history; sold by Charles R. Morson in January 1925 to Mrs. J. Insley Blair; Property from the Collection of Mrs. J. Insley Blair, sale no. 1618 (New York: Christie’s, January 21, 2006), lot 526; Important American Furniture, Folk Art, Silver and Chinese Export Art, sale no. 2815 (New York: Christie’s, January 23, 24, 27, 2014), lot 135; private collection; fully studied, figs. 1, 2, 16–20, 62.

11. Tilt-top candlestand, oval top with coved outer edge, urn pillar, and three cabriole legs with round feet, stamped “W. KING” on underside of pillar. No early history; offered by Adams, Davidson and Company, Washington, D.C., 1965; acquired and sold by Israel Sack, Inc., before 1969; The American Heritage Society Auction of Americana, sale no. 3923 (New York: Sotheby Parke Bernet, November 18–20, 1976), lot 960; Building America: The Wolf Family Collection, sale no. N11302 (New York: Sotheby’s, April 21, 2023), lot 879; private collection; fully studied, figs. 10, 11. In the late eighteenth century, names branded on furniture often referred to the owner. However, in this instance the mark was stamped rather than branded and is much smaller than usual. The typeface resembles in size and design that on King’s silhouettes and furniture labels. Though lacking the certainty of a label, the unconventional inscription probably documents the hand of the maker.

Case furniture formerly attributed to William King and related forms

Group #1 Attributed to the shop of Thomas Needham Jr. (1755–1787) and possibly Thomas Needham Sr. (1734–1804)

1. Chest of drawers, serpentine facade with canted front corners, claw-and-ball feet with full gadrooning on the knee. Owned by George Crowninshield (1766–1817); later by Elizabeth Silsbee (Mrs. William L.) Montgomery (1857–1946) and her daughter Marianne Montgomery (Mrs. George C.) Beach (1879–1962), who bequeathed it to the Peabody Museum of Salem (now Peabody Essex Museum), M11444; fully studied, figs. 3, 4, 14A, 29, 31–33.

2. Desk, reverse-serpentine facade, claw-and-ball feet with full gadrooning on the knee. Possibly owned by Timothy Pickering (1745–1829) of Salem; American Furniture and Decorative Arts, sale no. 2297 (Boston: Skinner, Inc., November 6, 2005), lot 149; Important Americana, sale no. N10005 (New York: Sotheby’s, January 17, 2019), lot 1557; private collection; fully studied, figs. 26, 34.

3. Chest of drawers, reverse-serpentine facade, ogee bracket feet with full gadrooning on the knee. Probably owned by George Ropes (1765–1807) and descended in his family; Fine Americana, sale no. 6227 (New York: Sotheby’s, October 26, 1991), lot 397; private collection; fully studied, figs. 25, 29.

4. Desk, reverse-serpentine facade, claw-and-ball feet without gadrooning. Owned by Sarah Ann Chever (1815–1908), who bequeathed it to the Essex Institute (now Peabody Essex Museum), 101792; fully studied, fig. 27.

5. Chest of drawers, serpentine facade, canted corners, claw-and-ball feet without gadrooning, inscribed “TN 1783” on case bottom. Made for Elias Hasket Derby (1739–1799) by Thomas Needham Jr., 1783; acquired by antiques dealer Israel Sack in 1911 and subsequently sold and bought back by his firm five times; private collection; fully studied, figs. 21, 22.

6. Chest of drawers, serpentine facade, canted corners with applied fretwork, carved claw-and-ball feet without gadrooning. No early history; owned by Luke Vincent Lockwood (1872–1951); Lockwood, Colonial Furniture in America, 3rd edition (New York: Scribner’s Sons, 1926), p. 129; sold to Maxim Karolik in 1939, and given to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 41.578; fully studied, fig. 23.

7. Chest of drawers, serpentine facade, canted corners with applied fretwork, ogee bracket feet without gadrooning. No early history; acquired by the firm of Bernard and S. Dean Levy and sold to Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Hennage in 1975, who bequeathed it to the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1990-291; studied from photos and through consultation with Colonial Williamsburg staff, fig. 24.

8. Desk, flat facade, claw-and-ball feet without gadrooning. No early history; New Year’s Weekend Auction (Amesbury, Mass.: John McInnis Auctioneers, January 3, 2020), lot 103, available online at https://www.liveauctioneers.com/item/79242648_18th-c-chippendale-mahogany-fall-front-desk, accessed February 24, 2024; private collection; fully studied.

9. Desk, reverse-serpentine facade, claw-and-ball feet without gadrooning. No early history; The Fall Sale, Session II (East Dennis, Mass.: Eldred’s Auction Gallery, November 20, 2020), lot 702, available online at https://www.eldreds.com/auction-lot/chippendale-slant-lid-desk-from-the-school-of-wil_A3243F79AE, accessed February 24, 2024; private collection; studied from extensive photos.

10. Desk, serpentine facade, claw-and-ball feet without gadrooning. No early history; Americana and International, Session Two (Downingtown, Penn.: Pook & Pook, Inc., January 13, 2022), lot 472, available online at https://live.pookandpook.com/online-auctions/pook/massachusetts-chippendale-mahogany-slant-desk-2593723, accessed February 24, 2024; private collection; fully studied.

11. Chest of drawers, bowfront facade, claw-and-ball feet without gadrooning, inscribed “Thoma[s]” in Needham’s handwriting. No early history; owned in the twentieth century by Constance Bradlee Devens (1923–1993), a descendant of the Crowninshield family of Salem; Important Americana, sale no. 6589 (New York: Sotheby’s, June 23–24, 1994), lot 338; private collection; fully studied, fig. 28.

Group #2 Attributed to an unidentified shop in the Salem-Beverly area

12. Desk, reverse-serpentine facade, ogee bracket feet with half-gadrooning on the knee. No early history; advertised by antiques dealer John Walton in Maine Antique Digest (March 1986): 39-B; later by its current owner, Stanley Weiss, Fine American Antiques in the Stanley Weiss Collection (Providence, R.I., 2019), p. 52, no. 01237; fully studied, figs. 37, 38.

13. Desk, reverse-serpentine facade, ogee bracket feet with half-gadrooning on the knee. No early history; American Furniture and Decorative Arts, sale no. 1902 (Bolton, Mass.: Skinner, Inc., February 28, 1999), lot 80; current location unknown; studied from photos, fig. 39.

14. Desk, serpentine facade, ogee bracket feet with half-gadrooning on the knee. No early history; offered by antiques dealer Bruce Sikora at the Spring Hartford Antiques Show, Maine Antique Digest (June 1996): 42-B; sold at Cyr Auctions, Gray, Maine, July 6, 2005, Antiques and the Arts Weekly, June 24, 2005, p. 111; now owned by James W. Lowery Fine Antiques and Arts; fully studied, figs. 14E, 35, 36, 57. This desk is probably the same one advertised by Cinnamon Hill Antiques, Antiques 145, no. 5 (May 1994): 660. The latter example features different brass hardware but is otherwise identical.

15. Desk and bookcase, flat facade, straight bracket feet without gadrooning. Reportedly owned by William Wayne II (1855–1933), Edith Sarah Fox (Wayne) Ridgeway (1889–1973), and Anthony Wayne Ridgeway (1916–2002), all of Paoli, Pennsylvania; William MacPherson Hornor Jr., Blue Book, Philadelphia Furniture, William Penn to George Washington (Philadelphia, 1935), pl. 36; Fine Americana, sale no. 4116 (New York: Sotheby Parke Bernet, April 27–29, 1978), lot 952; Philadelphia Splendor: The Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Max R. Zaitz, sale no. 12444 (New York: Christie’s, January 22, 2016), lot 180; private collection; fully studied, fig 46.

16. Chest-on-chest, flat facade, straight bracket feet without gadrooning. Old chalk inscription “John Allen / 1792 [W]ashington St” on the top of the lower case may refer to John Baxter Allen (1751–1836), who moved into a new house near what was to become Washington Street in Beverly, Massachusetts in 1792; later owned by Charles Storrow (1841–1927) and his wife Martha Robinson Cabot Storrow (1844–1897), to their daughter, Martha (Mary) Cabot Storrow (1872–1961), who married Francis Parkman Denny (1869–1948), to their daughter Ruth Denny (1917–2011), who married Seth Morton Vose II (1909–2007); acquired by the present owner from the Vose family in 1985 through antiques dealer and auctioneer Ronald Bourgeault; Historic New England, 1985.9; fully studied, figs. 40, 42–43, 49–53.

17. Desk, bombé facade, ogee bracket feet without gadrooning. Reportedly descended through the Whitney family of Boston and Dedham, Massachusetts; Annual Spring Auction (Cambridge, Mass.: CRN Auctions, May 20, 2018), lot 76; private collection; fully studied, figs. 47, 48.

18. Desk, blockfront facade, claw-and-ball feet without gadrooning. No early history; advertised by antiques dealer John Walton, Antiques 71, no 2 (February 1957): 102; Important Americana, Including Property from the Collection of Joan Oestreich Kend, sale no. N09607 (New York: Sotheby’s, January 20–21, 2017), lot 4293; private collection; fully studied.

Group #3 Attributed to an unidentified shop in the Salem area

19. Desk, serpentine facade, ogee bracket feet with half-gadrooning on the knee. A late nineteenth-century ink inscription on a document drawer reads: “This desk was built about the year 1785 for Polly Smith wife of Captn David Smith at her death which Occured 185[0] it came into possession of her daughter Mary Glazier and kept untill her death which occurred Nov 15, 1882 at which time it came into Possession of the Present Owner George W Glazier.” Mary (Polly) Collins married Captain David Smith (d. 1808) on August 29, 1797, suggesting that she was born in the early 1770s and thus would have been too young to have acquired the desk in 1785. However, the line of descent through the Smith and Glazier families, all of whom lived in Salem, is plausible. George W. Glazier died in 1915. Acquired by antiques dealer Joe Kindig Jr. between 1938 and 1944 and sold to Mr. and Mrs. George Maurice Morris; The Contents of the Lindens, sale no. 5262 (New York: Christie’s, January 22, 1983), lot 310; Philadelphia Splendor: The Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Max R. Zaitz, sale no. 12444 (New York: Christie’s, January 22, 2016), lot 181; private collection; fully studied, figs. 54–57.

20. Chest of drawers, reverse-serpentine facade, ogee bracket feet with half-gadrooning on the knee. An early twentieth-century ink inscription on a card pinned to a drawer records that “This bureau is the property / of Anna Welcome Johnson / Signed / Harriet L Crosby.” An adjacent shipping label lists the names “Katharine Johnson” and “Mary Dow.” Descended from Harriet L. Crosby (1856–ca. 1928) of Andover, to her niece Anna W. Johnson (1883–1968) and her sister Katherine H. Johnson (1885–1965) of Essex and Andover, and to their niece Mary Marble (Johnson) Dow (1906–1989) of Reading, all in Massachusetts; private collection; fully studied, fig. 58.

21. Chest of drawers, reverse-serpentine facade, ogee bracket feet with half-gadrooning on the knee. Descended in a Salem family to Mrs. Charles F. Batchelder Jr. (1906–1994); Summer Weekend Auction (Portsmouth, N.H.: Northeast Auctions, August 20–21, 2016), lot 680; private collection; fully studied, figs. 14B, 59–61.

Group #4 Attributed to an unidentified shop in the Salem-Ipswich area